Abstract

Erythropoiesis in the bone marrow and spleen depends upon intricate interactions between the resident macrophages and erythroblasts. Our study focuses on identifying the role of the Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) during recovery from stress erythropoiesis. To that end, we induced stress erythropoiesis in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2 null mice and evaluated macrophage subsets known to support erythropoiesis and erythroid cell populations. Our results confirm macrophage and erythroid hypercellularity after acute blood loss. Importantly, Nrf2 depletion results in a marked numerical reduction of F4/80+/CD169+/CD11b+ macrophages, which is more prominent under the induction of stress erythropoiesis. The observed macrophage deficiency is concomitant to a significantly impaired erythroid response to acute stress erythropoiesis in both the murine bone marrow and spleen. Additionally, peripheral blood reticulocyte counts as a response to acute blood loss is delayed in Nrf2 deficient mice compared to age-matched controls (11.0 ± 0.6% vs. 14.8 ± 0.6%, p≤0.001). Interestingly, we observe macrophage hypercellularity in conjunction with erythroid hyperplasia in the bone marrow during stress erythropoiesis in Nrf2+/+ controls, with both impaired in Nrf2−/− mice. We further confirm the finding of macrophage hypercellularity in another model of erythroid hyperplasia, the transgenic sickle cell mouse, characterized by hemolytic anemia and chronic stress erythropoiesis. Our results demonstrate the role of Nrf2 in stress erythropoiesis in the bone marrow and that macrophage hypercellularity occurs concurrently with erythroid expansion during stress erythropoiesis. Macrophage hypercellularity is a previously underappreciated feature of stress erythropoiesis in sickle cell disease and recovery from blood loss.

Introduction

Erythropoiesis occurs in specialized niches in the bone marrow consisting of a central macrophage, surrounded by differentiating erythroblasts. This central macrophage has been identified by several markers including, CD169 (Sialoadhesin or Siglec-1), F4/80, CD11b, VCAM-1, ER-HR3 and Ly-6G (1–3). Macrophages expressing CD169 play important roles in physiological and pathological erythropoiesis. They support erythropoiesis, both at steady state and during stress (4), and they prevent mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from the bone marrow (BM) into the blood stream (5). In line to their hematopoietic role, the depletion of CD169+ macrophages improves erythroid hypercellularity in polycythemia vera and thalassemia mice (6).

Nuclear factor (erythroid derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2), the master regulator of the cellular oxidative defense system, plays significant roles in hematopoiesis. These include globin gene regulation (7, 8), enhanced hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function, and maintenance of HSCs quiescence in steady-state hematopoiesis (9, 10). Besides, Nrf2 regulates myeloid differentiation of HSCs (11, 12), megakaryocyte maturation (13) and protection against oxidation-mediated hemolytic anemia (14, 15). Interestingly, at steady state, Nrf2 is reported as dispensable for murine erythropoiesis, development or growth. Homozygous Nrf2 knockout (Nrf2−/−) mice exhibited no visible phenotypes in hematological parameters when compared to wild-type mice (16, 17), although that changes as the animal age (15). Despite the significant progress in the field, the role of Nrf2 during recovery from stress erythropoiesis concomitantly with CD169+ macrophage population has not been adequately explored.

The present study explores the role of Nrf2 in maintaining specific subsets of macrophage populations that support erythropoiesis as well as the role of Nrf2 in recovery from acute blood loss in vivo. Our results show that Nrf2−/− mice is deficient in CD169+ macrophages together with impaired BM response during stress erythropoiesis. Interestingly, we observed a macrophage hypercellularity accompanies erythroid hypercellularity during recovery from stress erythropoiesis induced by acute blood loss. We confirmed this observation in sickle cell disease mice, a genetic model of chronic stress erythropoiesis (18) induced by hemolytic anemia.

Methods

Mice

Male and female C57BL/6J (Nrf2+/+) and Nrf2−/− mice were used. Nrf2+/+ mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (stock #000664) while Nrf2−/− mice and Townes’ knock-in transgenic sickle mouse (SS) and strain controls expressing normal human Hb (AA mice) were obtained from a colony maintained by Dr Solomon Ofori-Acquah’s laboratory in our institution. All mice strains were 14 weeks old. Mouse genotypes were confirmed by PCR.

Stress erythropoiesis

We induced stress erythropoiesis by performing acute phlebotomy (200μl/25g body weight) and hemin [Fe(III)PPIX, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO] injection performed under anesthesia. Hemin was first dissolved in 0.25M NaOH and then adjusted to pH 7.5 with HCl before filter sterilization. The hemin solution was protected from light and injected into 14 week-old mice. The mice were injected in the tail vein with a hemin dose of 120μmoles/kg body weight for Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice. Some of the mice received sterile vehicle (0.25M NaOH adjusted to pH 7.5 with HCl used in preparation of hemin) as a control. For acute blood loss, mice were phlebotomized by retro-orbital bleeding using a capillary tube internally coated with EDTA anticoagulant 5–7 days before injection to induce anemia. Complete blood count (CBC) was performed using HemaTrue hematology analyzer (Heska). Multiple phlebotomies were carried out using previously published methods (4, 6). Briefly, 400μl of blood were withdrawn followed by administration of 500μl of normal saline on 3 consecutive days. Recovery from anemia was monitored by withdrawing 50–100μl of blood every 2–4 days for CBCs and reticulocyte counts. For reticulocyte counts, unwashed aliquots of blood were stained with Thialzole Orange (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS at room temperature for 30min in the dark. Cell suspensions were acquired on Becton-Dickinson LSRFortessa and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Bone marrow and spleen analysis

Mouse BM cells were isolated from the femur and tibia with PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 2mM EDTA from mice untreated and treated with vehicle or hemin for 3 hours. The bone marrow suspension was filtered through a 70-μm-pore-size cell strainer (Fisherbrand, #22363548) centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min. Splenocytes were separated from stromal elements by passing spleen tissue through 70μm filters. The isolated splenocytes were incubated in 5ml of red blood cell lysis buffer (155mM NH4Cl, 14mM NaHCO3 and 127mM EDTA) for 5min at 8°C and washed twice with PBS.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained in PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 2mM EDTA. Ghost Dye Red 780 (Tonbo biosciences, #13–0865) was used to discriminate viable from non-viable cells, then staining with Anti-Mouse CD16/CD32 (Clone 2.4G2, BD Pharmingen #553142) to inhibit non-specific staining, following manufacturer’s instructions. Fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs specific to mouse CD169-BV605 and Alexa 647 (clone 3D6.112), F4/80-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone BM8), Ter119-APC (clone TER-119), CD71-FITC (clone RI7217) and CD11b- BV650 (clone M1/70), all purchased from BioLegend. Cell suspensions were fixed and acquired on Becton-Dickinson LSRFortessa and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the tissue lysates using the miRNeasy Mini Kit ((#217004, QIAGEN, Germantown, MD) and quantified using the Nanodrop 8000 microvolume spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Real-time PCR reactions were set-up with 50ng of RNA in duplicates. Genes of interest were evaluated using the TaqMan® Gene expression assay (ThermoFisher) and the TaqMan® RNA-to-Ct™ 1-Step Kit (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative quantification was calculated with the standard ΔΔCt method; amplification signals from target gene transcripts were normalized to those from beta-glucuronidase (GUSB) transcripts. Relative fold induction was calculated by further normalization to gene transcripts from untreated/vehicle treated animals. GUSB gene expressions were similar across all mouse strains used.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cryostat sections (5μm) of spleen were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), followed by 3x washes with solution of 0.5% BSA in PBS. The slides were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with primary antibody for CD169 Alexa 647 conjugate (#142408, Biolegend) at 1:200 combined with Flash phalloidin 488 (#424201, Biolegend) in 0.5% BSA solution. Slides were washed three times with BSA solution, 3x PBS, and nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye (bisbenzamide 1mg/100ml water) for 30 seconds. After three rinses with PBS, sections were cover-slipped with Gelvatol mounting media. Large area scan images were captured with a Nikon A1confocal microscope (NIS Elements 4.4).

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 7 software was used for all statistical analyses. Results are reported as mean ± SEM. Group means were compared using parametric tests, such as t-test (for 2 groups) and One-way ANOVA for more than two conditions. Pearson R2 was used to determine linear regression. Statistical significance was set at P values of <0.05.

Study approval

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh approved all experimental procedures performed on mice (Protocol #16099101).

Results

Nrf2−/− mice are deficient in CD169+ macrophages

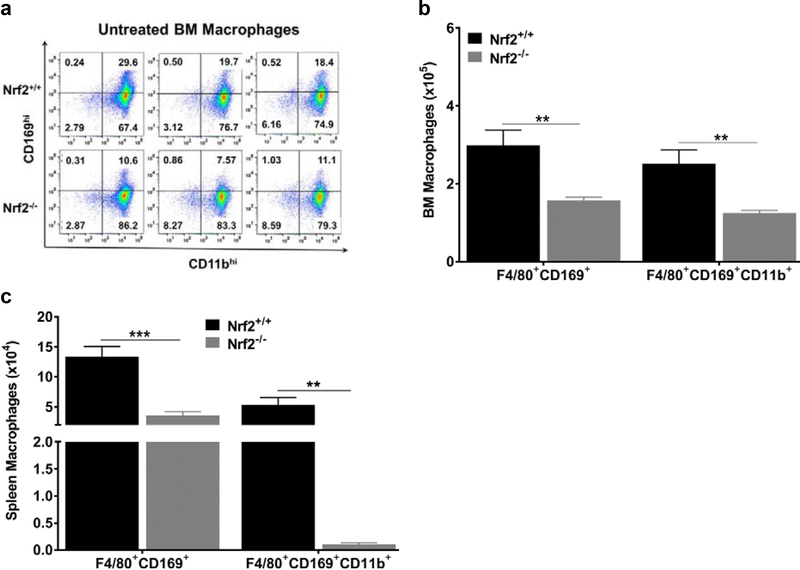

To investigate the contribution of Nrf2 in erythropoiesis, we first examined the erythropoiesis-supporting macrophage population in Nrf2+/+ and homozygous Nrf2−/− mice under steady state conditions. We used flow cytometry to quantify the expression of CD169, F4/80 and CD11b, which are commonly used as markers to identify these macrophages in the murine BM and spleen (4, 19). We found these markers to be broadly expressed in both strains. As shown in Fig. 1a and S1, Nrf2−/− mice showed a phenotype characterized by lower percentages of cells expressing known macrophage markers. Following mature red blood cells lysis, we gated for live cells using Ghost red, followed by CD45+ staining of nucleated cells. Macrophages were selected with F4/80+, then double positives for CD169 and CD11b. Overall, we observed a significant decrease of 47% (p≤0.01), and 50% (p≤0.01) in BM macrophage subpopulations expressing F4/80+CD169+, and F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ respectively, in age-matched Nrf2−/− mice compared to Nrf2+/+ control mice (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1: CD169+ macrophages are depleted in Nrf2−/− under homeostasis.

(a) Representative flow cytometry results based on CD169 and CD11b expression from 3 Nrf2+/+ and 3 Nrf2−/− mice. All cells are CD45+/F4/80+ (gating strategy is shown in supplemental data]). (b) Quantification of nucleated cells expressing F4/80+CD169+ and F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ of nucleated cells/femur in the BM (n=5 mice per group). (c) Quantification of spleen nucleated cells expressing F4/80+CD169+ and F4/80+CD169+CD11b (n=4–5 mice per group). Values are presented as the means±SEM. P values: * ≤0.05 and ***≤0.001, unpaired Student’s t test. This result was reproduced in two independent experiments using 2–3 mice (14 weeks old) per group in each experiment. Note differing scales (105 vs 104) between bone marrow and spleen in panels b and c.

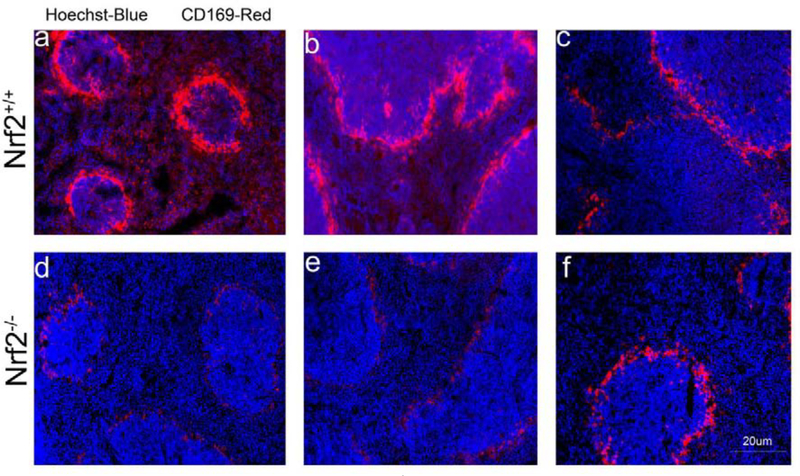

A similar pattern of decreased F4/80+CD169+ and F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ macrophage populations (p≤0.01) was also observed in the spleen of Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 1c). To further validate this Nrf2-related phenotype, immunofluorescence staining of isolated spleen tissue was carried out in Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice. As shown in Figure 2, the detection of CD169+ macrophages was overall markedly lower in different spleen sections of Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 2d–f) compared to Nrf2+/+ mice (Fig. 2a–c).

Figure 2: Immunofluorescence detection of CD169+ cells in the spleen.

Confocal microscopy images of spleen sections stained with an antibody against CD169+. (a-c) Nrf2+/+ mice, (d-f) Nrf2−/− mice. Staining was carried out in different spleen sections of six untreated 14 weeks old mice (n=3 per group).

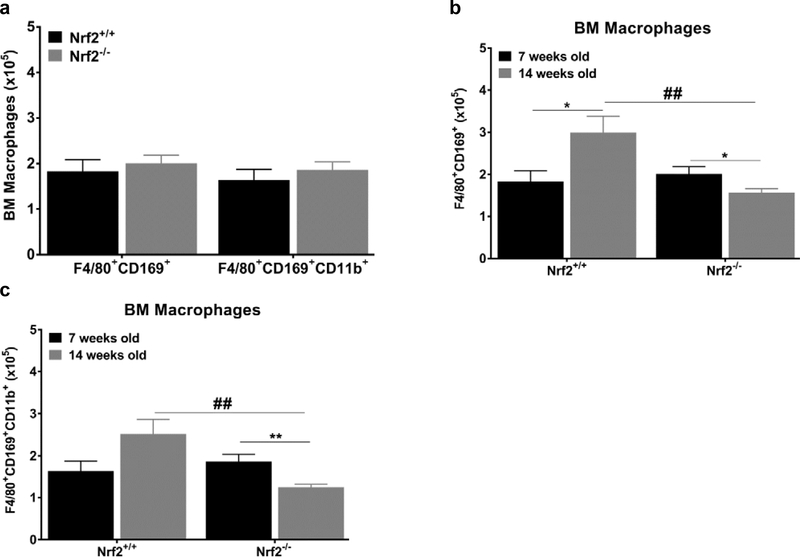

Interestingly, we didn’t observe a significant difference in different BM macrophage subpopulations between juvenile (7 weeks old) Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice (Fig 3a). In the control group, all BM macrophages subpopulations were significantly more abundant in the young adult mice (14 weeks old) than in the juvenile (7 weeks old, Fig. 3b). However, in Nrf2−/− group, F4/80+CD169+ and F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ BM macrophage populations declined by approximately 33% in the 14-week old mice (Fig. 3b and c, p≤0.05). This suggests that the reduction in the F4/80+CD169+ macrophage population subsets developed sometime between 7 and 14 weeks of age in Nrf2−/− animals. Macrophages in the spleen of Nrf2−/− mice also showed a parallel trend (Fig. S2). There were significant decreases between 7 and 14 weeks of subpopulations F4/80+CD169+ (p≤0.01) and F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ (p≤0.01).

Figure 3: Reduction in macrophage population is Nrf2 and age-dependent.

(a) Number of F4/80+CD169+; F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ cells/femur in juvenile Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice (b-c) Nrf2 and age-dependent decrease in the BM of untreated juvenile and young adult Nrf2−/− mice (n=4–5 mice per group). All cells are CD45+/F4/80+ (gating strategy is shown in supplemental data). Values are presented as the means±SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with unpaired Student’s t test. [*] denotes *p≤0.05 and **p≤0.01. [#] denotes Nrf2+/+ vs Nrf2−/− ##≤0.01.

Impaired erythroid stress response in Nrf2-deficient mice

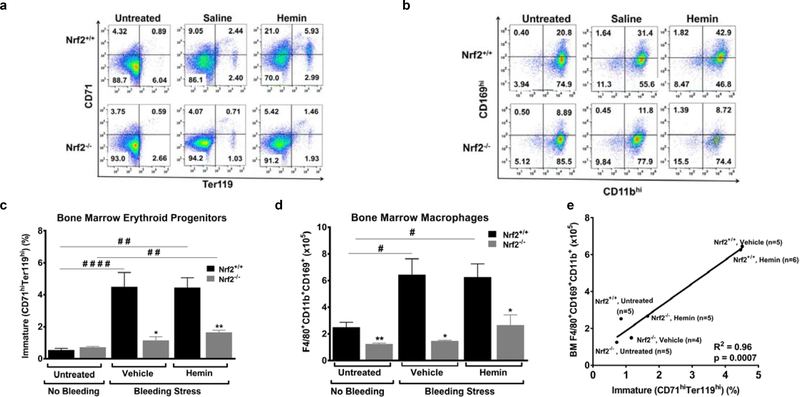

Due to the important role that the macrophages play in erythropoiesis, we hypothesized that Nrf2−/− macrophage-deficient mice would display a defect in their recovery from blood loss. Indeed, five to seven days after acute blood loss the Nrf2−/− mice had significantly lower hemoglobin compared to their baseline levels (p≤0.05, Table S1), while the Nrf2+/+ mice seemed to have fully recovered to their baseline hemoglobin levels. To further investigate this Nrf2−/−-related phenotype, we checked erythroid cells in the bone marrow and spleen of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice, using flow cytometry detection of CD71/Ter119 surface markers (Fig. 4a). In untreated animals, the percentage of immature (CD71hiTer119hi) and mature (CD71loTer119hi) erythroblasts (6) was similar in the bone marrows of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− animals (Fig. 4c and Fig. S3). However, in the bone marrow of Nrf2+/+ mice subjected to acute blood loss, immature erythroid progenitors increased by approximately 5-fold (p≤0.001, Fig. 4c) and mature erythroid progenitors increased by 12-fold (p≤0.05, Fig. S3). Consistent with our hypothesis, we observed an attenuated erythroid response in the bone marrow of the macrophage deficient, Nrf2−/− mice after acute blood loss. The attenuation is evident in both immature and mature erythroid subsets (Fig. 4c and Fig. S3). Interestingly, we didn’t observe any significant change in erythroid populations in the spleens of either mouse strain. Injection of hemin, a known inducer of the Nrf2 pathway, did not significantly modify the erythroid response to acute blood loss.

Figure 4: Nrf2 deficiency affects stress erythropoiesis and macrophage hypercellularity in mice.

(A) Representative flow cytometry results based on CD71 and Ter119 expression of Nrf2+/+ (n = 3) and Nrf2−/− mice (BM) (n = 3). (B) Representative flow cytometry results based on CD169 and CD11b expression of Nrf2+/+ (n = 3) and Nrf2−/− (n = 3) mice. All cells are CD45+/F4/80+ (gating strategy is provided in Supplemental Data). (C) Nrf2 deficiency leads to a decrease in immature BM erythroid progenitors during recovery from bleeding stress with or without hemin injection (n = 4 or 5 mice per group). (D)Nrf2 deficiency leads to a decrease in F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ BM macrophages during recovery from bleeding stress with or without hemin injection (n = 4 or 5 mice per group). (E) Bone marrow F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ macrophage counts positively correlate with CD71hiTer119hi erythroid progenitor counts in untreated, vehicle-treated, and hemin-treated Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice (n = 4–6 mice per group). Values are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was evaluated with one-way ANOVA. Untreated/vehicle-treated/hemin-treated Nrf2+/+ compared with Nrf2−/−: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01. Untreated compared with vehicle-treated/hemin-treated: #p ≤ 0.05, ##p ≤ 0.01, ####p ≤ 0.0001. This result was reproduced in two independent experiments using two or three mice per group in each experiment. R2 was determined with linear regression.

Erythroid stress induces Nrf2-dependent macrophage hypercellularity

Blood loss induced an unexpected and pronounced macrophage hypercellularity in the wild type mice concurrent with the expected erythroid response (Fig. 4d). Nrf2+/+ mice showed about 3-fold increase in F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ BM (Fig. 4d; Fig. S4a) and spleen (Fig. S4bc) macrophages. Nrf2 deficiency significantly blunted this stress-induced macrophage hypercellularity by 76–93% both in the bone marrow (Fig. 4d and Fig. S4a) and spleen (Fig. S4bc) of Nrf2−/− mice. This outcome was not significantly affected by hemin injections (Fig. 4d; Fig S4). To further corroborate the effect of blood loss in both Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice, we analyzed the transcriptional activation of heme-oxygenase 1 (HO-1), a well-known Nrf2-regulated gene that is essential for erythropoiesis (20, 21). HO-1 mRNA expression increased 3-fold and 23-fold in phlebotomized Nrf2+/+ mice animals subjected to vehicle or hemin treatment respectively. However, the transcriptional activation of HO-1 in Nrf2-deficient mice, treated under the same conditions, was significantly blunted to 2-fold and 12-fold (Fig. S5, p≤0.05). Our findings indicate that macrophage hypercellularity together with HO-1 induction accompanies erythroid hypercellularity as a response to blood loss. Our results also suggest that blood loss triggers an Nrf2-dependent mechanism which is essential not only for macrophage counts but also for their ability to express HO-1 and metabolize heme.

BM macrophage cell counts correlate with erythroid cell counts

Erythroid cells develop in close proximity to macrophages in the bone marrow, where the macrophage is thought to act as the ‘nurse’ cell that provides nutrients and cytokines to support erythroid cell survival, maintenance and maturation (1, 4, 6, 22–24). In concurrence to that model, our results from untreated and stressed Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice show a significant correlation between erythroid cell and macrophage cell counts (Fig. 4e). More specifically, F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ macrophage cell counts positively correlated with CD71hiTer119hi erythroid cell counts (R2=0.96, p=0.0007), macrophages which are considered to be erythroblastic island macrophages.

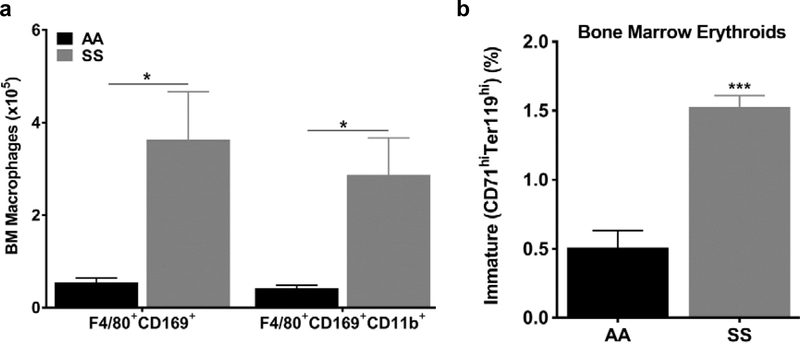

Macrophage hypercellularity accompanies erythroid hyperplasia in hemolytic anemia

In line with our previous findings, we would expect to find macrophage hypercellularity in hematological disorders showing erythroid hyperplasia, like sickle cell disease (SCD). Therefore, we assessed macrophage hypercellularity in the Townes sickle cell mice (SS), a well-characterized genetic model of mouse sickle cell disease, and the appropriate strain controls (AA mice). Similar to Figure 1, we used flow cytometry to identify BM macrophages positive for CD45, CD169, F4/80 and CD11b surface markers. Our analysis shows that all BM macrophage phenotypic subsets are 6.5-fold higher (p≤0.05, Fig 5a) in SS mice than AA controls at steady state (untreated animals). F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ macrophage subsets were 6.8-fold higher in SS mice than age-matched AA controls (2.87±0.8% versus 0.42±0.1%, p≤0.05, Fig 5a). This macrophage hypercellularity was accompanied by erythroid hyperplasia, typical for sickle cell disease. We observed a 3 to 12-fold increase of immature (CD71hiTer119hi) BM and spleen erythroid progenitor cells in SS mice compared to AA controls (p≤0.001, Fig 5b and S6). A similar trend was also observed in mature BM erythroid cells, although it was not statistically significant (data not shown). Morphological review of peripheral blood and bone marrow erythroid cells support the flow cytometry findings of erythroid hyperplasia in SS mice compared to AA control mice (Fig. S7). Our flow cytometry analysis of the spleen macrophages provided qualitatively similar findings to the bone marrow analysis (Fig. S6). These results in Nrf2+/+ mice after blood loss, and in SS mice during steady state hemolysis, demonstrate that bone marrow macrophage hypercellularity is associated with erythroid hyperplasia in two very different models of stress erythropoiesis.

Figure 5: macrophage hypercellularity accompanies erythroid hyperplasia in sickle cell mice.

(a) Increased numbers of F4/80+CD169+CD11b+ macrophages in the BM of SS compared to AA mice (n=4–5 mice per group). All cells are CD45+/F4/80+ (gating strategy is shown in supplemental data). (b) Increased numbers of immature BM erythroid progenitors in SS compared to AA mice (n=4–5 mice per group). Values are presented as the means±SEM. P values: * ≤0.05 and ***≤0.001, unpaired Student’s t test.

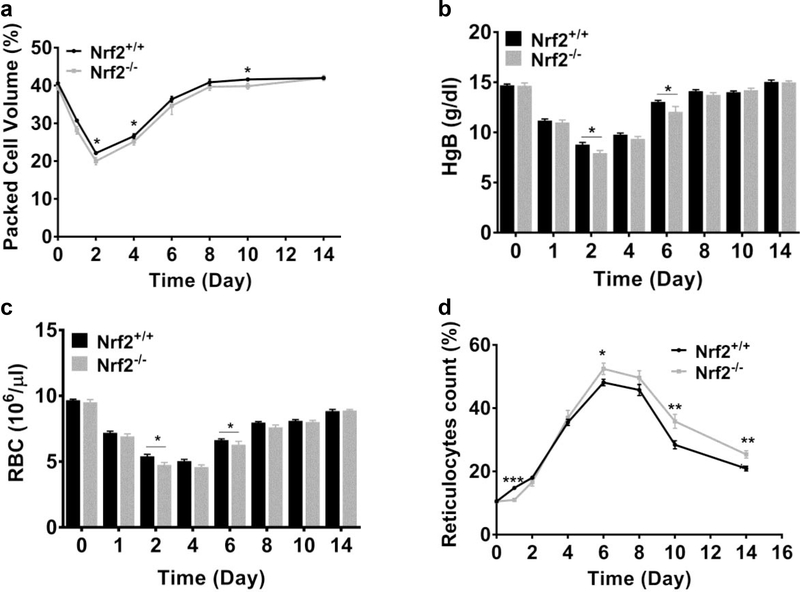

Macrophage deficiency is associated with delayed recovery from anemia in Nrf2-deficient mice

To extend our understanding of how macrophage cell number affects erythroid response, we induced anemia to Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice by repeated phlebotomies over 3 consecutive days. Both strains had similar packed cell volume (PCV) at baseline and as expected, their PCV dropped rapidly during the 3 days of blood withdrawal. However, PCV of Nrf2−/− mice during the recovery period was overall significantly lower than Nrf2+/+ PCV (p≤0.05, two-way ANOVA), suggesting a delay in erythroid recovery (Fig. 6a). Analysis of individual time points shows significantly lower PCV values on Days 2, 4 and 10 (p≤0.05, Fig. 6a). Consistent with the PCV differences, we observed significantly lower hemoglobin levels and decreased red blood cell counts (RBCs) in Nrf2−/− mice on Days 2 and 6 (p≤0.05, Fig. 6b and c). Reticulocyte count, a marker of erythroid hypercellularity (4, 6), showed small but significant differences between the Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice. On day 1 (2nd phlebotomy), we observed a significantly lower reticulocyte count in Nrf2−/− mice than Nrf2+/+ control mice (11.0 ± 0.6% vs. 14.8 ± 0.6%, p≤0.001, Fig. 6d), consistent with a delayed erythroid response to blood loss. In later stages of recovery (Day 6 to 14), the reticulocyte counts of Nrf2−/− mice remained significantly higher compared to Nrf2+/+ control mice (p≤0.05, Fig. 6d) suggesting a delay in recovering their steady state status. Collectively, our data demonstrate that the Nrf2−/− mice, having less BM macrophages, show a small but statistically significant delay in functional erythroid response and recovery from experimentally-induced anemia.

Figure 6: Macrophage deficiency is associated with delayed recovery from anemia in Nrf2-deficient.

Peripheral blood analysis of Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice subjected to multiple phlebotomies (a) Packed cell volume (b) Hemoglobin levels (HgB) (c) RBC counts and (d) reticulocytes count. Values are presented as the means±SEM. Data are pooled from three independent experiments. P values: * ≤0.05, ** ≤0.01 and ***≤0.001, unpaired Student’s t test. (n=8–16 mice per group at each time point).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates for the first time that acute blood loss or chronic hemolysis results in BM macrophage hypercellularity in association with erythroid hyperplasia. We show for the first time that Nrf2-deficient mice have a deficiency of macrophages, including the CD169+ subsets characterized as erythroblastic island (EI) macrophages (1, 2, 4, 25, 26). Our Nrf2 null model of congenital macrophage deficiency confirms and extends the findings of other groups showing that experimental macrophage depletion impairs erythroblast response in anemia (4, 6). In those previous publications, approximately 90% depletion of macrophages produces a pronounced impairment of erythroid response to blood loss. In our results, about 50% depletion of macrophages yielded a significant but milder impairment of erythroid response to blood loss, as might be expected.

Nrf2 is a master transcription factor that regulates several cytoprotective genes. Although, Nrf2 expression is dispensable for murine erythropoiesis at steady state (16), Murakami et al. have shown that the Nrf2 pathway regulates hematopoietic stem cell fate (11). To date, Nrf2’s role during recovery from stress erythropoiesis has not been addressed. Our results show for the first time that Nrf2 expression is essential in stress induced macrophage hypercellularity. More importantly, the decrease in macrophage counts in Nrf2 null mice encompasses specific macrophage subsets that are implicated in supporting erythropoiesis (1, 2, 4). This macrophage deficiency develops after 7 weeks of age, suggesting that the reduction observed in young adult mice might be due to cumulative loss of this macrophage population over time. We also found that Nrf2 null mice express less HO-1 during stress erythropoiesis, which is more likely due to Nrf2 transcriptional regulation of the HO-1 promoter (27). The depletion of macrophages between juvenile and young adults that we have observed in this study might be due to secondary loss of HO-1 activity or other Nrf2-regulated antioxidant function, or spontaneous apoptosis (12, 28). Our results do not address the potential role of macrophage deficiency in age-related anemia in the Nrf2-deficient mouse (15). Our findings suggest that Nrf2 deficiency partially phenocopies the HO-1 deficiency, which affects RBC and macrophage lifespan, erythroblastic island formation and erythropoiesis (20, 28).

Several factors may be responsible for the Nrf2 null phenotype. The lower macrophage count could be a direct result of the toxic oxidative microenvironment in Nrf2−/− mice (15) leading to increased cell damage or due to an Nrf2-centered regulatory switch leading to cell death (12). Alternatively or jointly, the reduction in HO-1 expression would also result in macrophage dysfunction due to impaired heme detoxification (28). Kovtunovych et al. have shown that macrophages in HO-1−/− mice become depleted in the spleen and liver as they lyse after ingesting senescent RBCs (28). In addition to macrophage changes, we observed changes in erythroid cells and our analysis revealed a positive correlation between BM macrophage and immature erythroid progenitor counts in untreated and stressed Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/−mice. This strengthens our conclusion that macrophage hypercellularity is a feature of stress erythropoiesis. HO-1 deficiency is known to interfere with erythroid biology by disrupting the macrophage-erythroblast interaction in the bone marrow (20) and by impairing heme recycling and iron trafficking (28). It is not likely that restricted iron trafficking to erythroid progenitors occurs in Nrf2−/− mice, since we didn’t detect any changes of MCV and MCH in peripheral blood. This is an area worthy of additional investigation.

In addition to acute blood loss, our study shows for the first time that sickle cell anemia also exhibits macrophage hypercellularity in addition to erythroid hyperplasia at steady state. Sickle cell disease is characterized by chronic stress erythropoiesis and a highly inflammatory state (29). Our finding of macrophage hypercellularity is particularly interesting in light of the rising interest in macrophage pathways in sickle cell disease (30–35). Recently, macrophage hypercellularity was reported in correlation with erythroid hypercellularity in genetic models of erythrocytosis (36) and induced anemic stress (37, 38). This macrophage-erythroid regulatory axis may have an implication for all human diseases characterized by increase in erythroid population. It would be very interesting to examine how macrophage hypercellularity would affect innate immune system regulation under such disease conditions.

Our bone marrow macrophage result is different from that reported by Ulyanova et al., phenylhydrazine was used to induce hemolysis and also had an erythropoietin model that stimulated increase in splenic, but not bone marrow macrophages (38), which differs from our bone marrow result in our acute blood loss model for unclear reasons. We used the acute blood loss model to induce stress erythropoiesis, a commonly employed model. The phenylhydrazine model induces oxidative damage to the red cell membrane that promotes erythrophagocytosis by splenic, marrow and hepatic macrophages that may stimulate them. It also induces anemia and consequent erythropoietin secretion, so at least two macrophage pathways may be activated, especially in the spleen. Our blood loss model is likely to activate only the erythropoietin pathways. Future research in these partially overlapping models may have potential to clarify possible shared and distinct mechanisms underlying the results published by Ulyanova and those presented here, including possible effects on erythropoietin concentrations.

Due to limitations in our experimental approach, we cannot exclude a direct role for Nrf2 deficiency in erythroid or hematopoietic stem cells. Nrf2 regulates both migration and retention of hematopoietic stem cells in their niches (10), with Nrf2 deficient mice having increased circulating HSCs. On the other hand, CD169+ macrophages promote retention of HSCs via secretion of an unknown protein used by Nestin+ cells (5). HO-1 deficiency has also been described to affect stem cell and progenitor cell function in stress erythropoiesis (21, 39), and presumably Nrf2 deficient stem cells have a secondary deficiency in HO-1, which we did not evaluate.

In conclusion, our study supports a role for Nrf2 in erythroid biology. Such a role was previously unappreciated and appears to be mediated through macrophage function. Macrophage-erythroid interaction is an important area for additional research with potential applications to diseases involving anemic stress and erythroid hyperplasia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Diane Lenhart, Bethany Flage, Danielle Crosby and Flow Core Staff, Department of Immunology, University of Pittsburgh for technical assistance.

Funding

Dr. Kato received support from NIH grants HL133864, MD009162 and from the Institute for Transfusion Medicine Hemostasis and Vascular Biology Research Institute at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Dr. Ofori-Acquah is supported by NIH grants R01HL106192, U01HL117721 and U54HL141011. Dr. Bullock is supported by the University of Pittsburgh Department of Pathology.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest in relation to the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jacobsen R, Perkins A, Levesque J. Macrophages and regulation of erythropoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22(2):212–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chasis J Erythroblastic islands: specialized microenvironmental niches for erythropoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2006;13(3):137–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seu KG, Papoin J, Fessler R, Hom J, Huang G, Mohandas N, et al. Unraveling Macrophage Heterogeneity in Erythroblastic Islands. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow A, Huggins M, Ahmed J, Hashimoto D, Lucas D, Kunisaki Y, et al. CD169⁺ macrophages provide a niche promoting erythropoiesis under homeostasis and stress. Nat Med. 2013;19(4):429–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow A, Lucas D, Hidalgo A, Méndez-Ferrer S, Hashimoto D, Scheiermann C, et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J Exp Med. 2011;208(2):261–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos P, Casu C, Gardenghi S, Breda L, Crielaard B, Guy E, et al. Macrophages support pathological erythropoiesis in polycythemia vera and β-thalassemia. Nat Med. 2013;19(4):437–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talbot D, Grosveld F. The 5’HS2 of the globin locus control region enhances transcription through the interaction of a multimeric complex binding at two functionally distinct NF-E2 binding sites. EMBO J. 1991;10(6):1391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerins M, Ooi A. The Roles of NRF2 in Modulating Cellular Iron Homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;00(00):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J, Thimmulappa R, Kumar V, Cui W, Kumar S, Kombairaju P, et al. NRF2-mediated Notch pathway activation enhances hematopoietic reconstitution following myelosuppressive radiation. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):730–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsai J, Dudakov J, Takahashi K, Shieh J, Velardi E, Holland A, et al. Nrf2 regulates haematopoietic stem cell function. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(3):309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murakami S, Shimizu R, Romeo PH, Yamamoto M, Motohashi H. Keap1-Nrf2 system regulates cell fate determination of hematopoietic stem cells. Genes Cells. 2014;19(3):239–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merchant AA, Singh A, Matsui W, Biswal S. The redox-sensitive transcription factor Nrf2 regulates murine hematopoietic stem cell survival independently of ROS levels. Blood. 2011;118(25):6572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motohashi H, Kimura M, Fujita R, Inoue A, Pan X, Takayama M, et al. NF-E2 domination over Nrf2 promotes ROS accumulation and megakaryocytic maturation. Blood. 2010;115(3):677–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawatani Y, Suzuki T, Shimizu R, Kelly VP, Yamamoto M. Nrf2 and selenoproteins are essential for maintaining oxidative homeostasis in erythrocytes and protecting against hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2011;117(3):986–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JM, Chan K, Kan YW, Johnson JA. Targeted disruption of Nrf2 causes regenerative immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(26):9751–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan K, Lu R, Chang JC, Kan YW. NRF2, a member of the NFE2 family of transcription factors, is not essential for murine erythropoiesis, growth, and development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(24):13943–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroha T, Takahashi S, Komeno T, Itoh K, Nagasawa T, Yamamoto M. Ablation of Nrf2 function does not increase the erythroid or megakaryocytic cell lineage dysfunction caused by p45 NF-E2 gene disruption. Journal of biochemistry. 1998;123(3):376–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blouin MJ, De Paepe ME, Trudel M. Altered hematopoiesis in murine sickle cell disease. Blood. 1999;94(4):1451–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao C, Hardison RC, Kennett MJ, Carlson BA, Paulson RF, Prabhu KS. Selenoproteins regulate stress erythroid progenitors and spleen microenvironment during stress erythropoiesis. Blood. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser ST, Midwinter RG, Coupland LA, Kong S, Berger BS, Yeo JH, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency alters erythroblastic island formation, steady-state erythropoiesis and red blood cell lifespan in mice. Haematologica. 2015;100(5):601–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao YA, Wagers AJ, Karsunky H, Zhao H, Reeves R, Wong RJ, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency leads to disrupted response to acute stress in stem cells and progenitors. Blood. 2008;112(12):4494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manwani D, Bieker J. The Erythroblastic Island. 2008;82:23–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korolnek T, Hamza I. Macrophages and iron trafficking at the birth and death of red cells. Blood. 2015;125(19)):2893–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leimberg M, Prus E, Konijn A, Fibach E. Macrophages function as a ferritin iron source for cultured human erythroid precursors. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2008;103(4):1211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chasis JA, Mohandas N. Erythroblastic islands: niches for erythropoiesis. Blood. 2008;112(3):470–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Back DZ, Kostova EB, van Kraaij M, van den Berg TK, van Bruggen R. Of macrophages and red blood cells; a complex love story. Frontiers in physiology. 2014;5:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2016;73(17):3221–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovtunovych G, Eckhaus MA, Ghosh MC, Ollivierre-Wilson H, Rouault TA. Dysfunction of the heme recycling system in heme oxygenase 1-deficient mice: effects on macrophage viability and tissue iron distribution. Blood. 2010;116(26):6054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoppe CC. Inflammatory mediators of endothelial injury in sickle cell disease. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America. 2014;28(2):265–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vinchi F, Costa da Silva M, Ingoglia G, Petrillo S, Brinkman N, Zuercher A, et al. Hemopexin therapy reverts hemeinduced proinflammatory phenotypic switching of macrophages in a mouse model of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2016;127(4):473–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theurl I, Hilgendorf I, Nairz M, Tymoszuk P, Haschka D, Asshoff M, et al. On-demand erythrocyte disposal and iron recycling requires transient macrophages in the liver. Nature medicine. 2016;22(8):945–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nouraie M, Cheng K, Niu X, Moore-King E, Fadojutimi-Akinsi MF, Minniti CP, et al. Predictors of osteoclast activity in patients with sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2011;96(8):1092–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dasgupta SK, Thiagarajan P. The role of lactadherin in the phagocytosis of phosphatidylserine-expressing sickle red blood cells by macrophages. Haematologica. 2005;90(9):1267–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belcher JD, Marker PH, Weber JP, Hebbel RP, Vercellotti GM. Activated monocytes in sickle cell disease: potential role in the activation of vascular endothelium and vaso-occlusion. Blood. 2000;96(7):2451–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hebbel RP, Schwartz RS, Mohandas N. The adhesive sickle erythrocyte: cause and consequence of abnormal interactions with endothelium, monocytes/macrophages and model membranes. Clin Haematol. 1985;14(1):141–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Hayashi Y, Yokota A, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Huang R, et al. Expansion of EPOR-negative macrophages besides erythroblasts by elevated EPOR signaling in erythrocytosis mouse models. Haematologica. 2018;103(1):40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao C, Prabhu KS, Paulson RF. Monocyte-derived macrophages expand the murine stress erythropoietic niche during the recovery from anemia. Blood. 2018;132(24):2580–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ulyanova T, Phelps SR, Papayannopoulou T. The macrophage contribution to stress erythropoiesis: when less is enough. Blood. 2016;128(13):1756–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao YA, Kusy S, Luong R, Wong RJ, Stevenson DK, Contag CH. Heme oxygenase-1 deletion affects stress erythropoiesis. PloS one. 2011;6(5):e20634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.