Abstract

Male breast cancer is a rare malignancy. Due to low prevalence and limited data to support male breast cancer screening, there are currently no recommendations for image-based screening in asymptomatic men and few recommendations for men at high risk for breast cancer. However, symptomatically diagnosed cancers in men are typically advanced, suggesting that earlier detection may improve outcomes. In this article we briefly review the risk factors for male breast cancer and discuss the potential benefits and possible drawbacks of routine image-based screening for men at high risk for breast cancer.

Keywords: male breast cancer; screening; risk factors; BRCA 1, 2; mammography

1. Background

Male breast cancer is a rare malignancy representing approximately 1% of all breast cancer cases [1], with an estimated 2670 new cases and 500 deaths attributable to the disease in 2019 in the United States [2,3]. The incidence of male breast cancer has risen over the past few decades [4–6]. The lifetime risk for female breast cancer is 1 in 8 (12%) while the lifetime risk for male breast cancer is 1 in 833 (0.12%) [7]. Men are overwhelmingly diagnosed with ductal carcinomas because lobules, the origination site of invasive lobular carcinomas, are not typically well developed in the male breast. The receptor status of male breast cancers is most commonly estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) positive and HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) negative [1,6]. Men with breast cancer are older (median age of 63 years), present with a larger tumor size (> 2 cm), more frequently have nodal involvement, exhibit more advanced stage, and have poorer stage for stage overall survival compared to women [6,8,9]. Approximately 40% of men present with stage III or IV disease [10]. Since the 1980s, mortality rates from breast cancer have decreased for women. This observation has been attributed to improvements in treatments as well as widespread adoption of screening mammography [11,12]. On the other hand, male breast cancer mortality rates have remained unchanged over the same period despite similar treatment algorithms [13].

Breast cancer in males is usually detected when symptomatic, typically presenting as a palpable lump, or less commonly as skin changes, nipple retraction, or nipple discharge [10,14,15] (Figure 1a-c). Due to anatomical differences in the male breast compared to females, breast masses may be more appreciable as they are closer to the skin, which may also explain the more frequent skin involvement and regional lymphatic involvement in male breast cancers [16]. Gynecomastia, a benign proliferation of breast tissue in men, is the most common differential diagnostic consideration, and is present in approximately half of male breast cancer cases [17]. Distinguishing gynecomastia from male breast cancer, however, is not usually a diagnostic challenge as male breast cancers usually present as an irregular mass with indistinct or spiculated margins sometimes with associated microcalcifications [18–20], while gynecomastia most often presents as a retroareolar flame-shaped focal asymmetry [16] (Figure 2a-b).

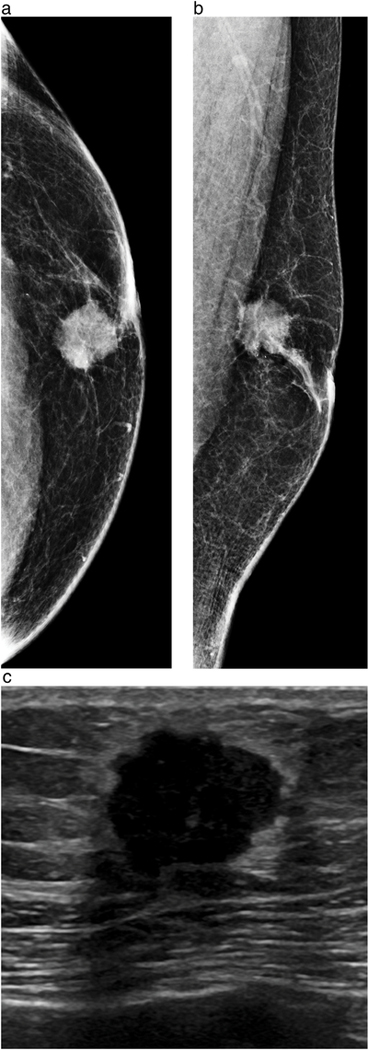

Figure 1a-c.

60-year-old male presents with a palpable mass. Craniocaudal (a) and mediolateral oblique (b) views from diagnostic mammography demonstrates a 1.7 cm irregular, high-density mass with a few calcifications in the subareolar location. Ultrasound (c) demonstrates a corresponding hypoechoic irregular mass with angular and microlobulated margins. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy revealed grade 2 ER positive, PR positive, HER2 negative invasive ductal carcinoma. At surgery, 1 of 6 axillary lymph nodes were positive for malignancy.

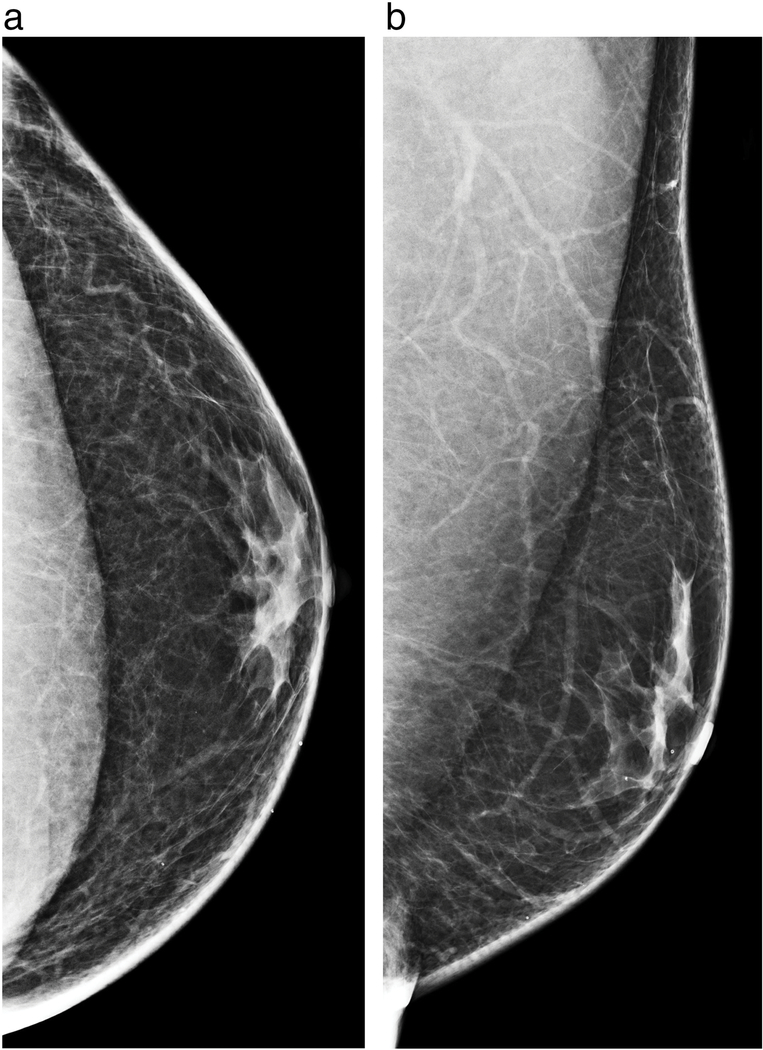

Figure 2a-b.

Left breast craniocaudal (a) and mediolateral oblique diagnostic mammograms demonstrate the typical flame-shaped appearance of retroareoloar breast tissue in a male patient consistent with gynecomastia.

For men 25 years of age or older presenting with a palpable abnormality, bilateral diagnostic mammography [18,21] is the recommended initial imaging test. For men younger than 25 years, diagnostic ultrasound is recommended. Diagnostic mammography is highly sensitive (92–100%), and specific (90–96%) for male breast cancer, with a negative predictive value approaching 100% [17,18,20,22,23]. Diagnostic ultrasound can also be performed as an adjunct tool in the setting of indeterminate mammographic findings and for biopsy planning [18].

Due to the low prevalence of male breast cancer and limited data to support breast cancer screening in men [1,6,24], there are currently no recommendations for image-based screening in asymptomatic men [25]. The American Cancer Society states that “Screening men for breast cancer has not been studied to know if it is helpful, …” [26]. Other organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the American College of Radiology (ACR) do not directly address the question of breast cancer screening for asymptomatic men. Although the definition of women at “high risk” for breast cancer has been well established [27], a corollary definition for men has not yet been established, although one review paper considered men “high risk” if they had a lifetime risk greater than the male average risk [16]. This contrast is likely due to the large difference in “average” lifetime risk for breast cancer for each gender: approximately 1 in 833 for men, and 1 in 8 for women [28].

Little research has investigated screening for men at high risk for breast cancer resulting in few established guidelines for this population (Table 1). Men testing positive for a BRCA (Breast Cancer) 1 or 2 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants have an increased lifetime risk for the development of breast cancer [29]. Thus, the NCCN recommends annual clinical breast examination as well as training in monthly breast self-examination starting at age 35. The NCCN does not recommend routine screening mammography secondary to limited data [30]. For men with a personal history of breast malignancy, the NCCN recommends consideration of genetic testing. As a result of recent research [31], guidelines from the American Society of Breast Surgeons recommend that all patients diagnosed with breast cancer receive genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer [32].

Table 1.

Current national organization recommendations for screening men at high risk of breast cancer.

| Organization | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| American Cancer Society | • Careful breast exams might be useful for screening men with a strong family history of breast cancer, or with BRCA mutations • Screening men for breast cancer has not been studied to know if it is helpful |

| American College of Radiology | • None |

| American Society of Breast Surgeons | • None |

| American Society of Clinical Oncology | • None |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network | For BRCA positive men: • Education regarding signs and symptoms of cancer • Breast self-exam training and education starting at age 35 years • Clinical breast exam, every 12 months, starting at age 35 years • Limited data support imaging in men |

Men commonly have advanced disease at the time of initial presentation suggesting that earlier detection may improve outcomes and introduces the potential value of image-based screening in high risk populations. Recent American Society of Clinical Oncology Multidisciplinary Meeting recommendations suggest consideration of baseline and annual mammography for BRCA 1 or 2 positive men with gynecomastia or glandular breast density on the baseline study [24]. Male patients proposed for annual image-based screening may include men with a personal history of breast cancer or BRCA mutation carriers [33]. In this article, we briefly review the risk factors for male breast cancer, and discuss the potential benefits and possible drawbacks of routine image-based screening for men at high risk for breast cancer.

2. Risk Factors for Male Breast Cancer

There are multiple factors that increase the risk of breast cancer in men beyond increased age, including genetic, demographic, hormonal, and environmental influences (Table 2). As with women, deleterious genetic mutations increase the risk for male breast cancer and are found in approximately 10% of men diagnosed with breast cancer [31]. Studies demonstrate that up to 4% of men with breast cancer have BRCA1 mutations, while 4 to 16% have BRCA2 mutations [1,34–36]. The absolute lifetime risk for male BRCA 1 carriers is 1.2–2%, while the risk for BRCA 2 carriers is 6.8–8% [16,29]. Although the absolute risk is low given the low incidence of the disease, the relative increase in risk from baseline is higher for men than women: BRCA1 carriers have a 20-fold increase in risk, while BRCA 2 carriers have an 80-fold increase in risk (there is an approximately 7-fold increase in risk for BRCA1 or 2 female carriers) [16,37]. In addition, as more women with breast cancer are identified as carriers of a genetic mutation through the increased adoption of multigene testing and recommendations such as those from the American Society of Breast Surgeons, male relatives will be increasingly identified as carriers thus expanding the pool of men known to have an increased risk of malignancy. In addition, mutations in CHEK2 (checkpoint kinase 2), PALB2 (partner and localizer of BRCA2), CYP17A1 (cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A member 1), and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) genes are established risk factors for male breast cancer, albeit with much lower penetrance than BRCA 1 or 2 mutations.

Table 2.

Risk factors for male breast cancer

| Risk Factor | Relative Risk of Malignancy | |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic | BRCA1 mutation | 20x [16,29] |

| BRCA2 mutation | 80x [16,29,78] | |

| CHEK2*1100delC mutation | 4–10x [79,80] | |

| PALB2 mutation | Minimal [36] | |

| Demographic | Age | Average age = 67 years [6] |

| Family history of breast cancer | First degree relative: 1.9x Mother and sister: 10x [41] |

|

| Personal history of male breast cancer | 30–112x [42–44] | |

| Black race | 1.3x [45] | |

| Ashkenazi Jewish | 1.8x [47] | |

| Hormonal | Klinefelter syndrome, XXY | 16–19x [49–51] |

| Gynecomastia | 5–10x [49,51] | |

| Obesity | 1.4–2x [41,49] | |

| Increased serum estradiol | 2.5x [81] | |

| Environmental | Radiation exposure | 1–2x (diagnostic/therapeutic radiation) [55] 15x (atomic bomb survivors) [54] |

Family history is one of the strongest risk factors for female breast cancer [38–40] and a family history of breast cancer increases the risk for male breast cancer depending on the number and family member(s) affected. Men with a first-degree relative have a relative risk of 1.9, and those men with both an affected mother and sister have nearly 10 times the risk of men without a family history [41]. There is a 30- to 112-fold risk for recurrence or a second primary breast malignancy in men previously treated for breast cancer [42–44]. This level of risk is far greater than for women with a personal history of breast cancer (2- to 4-fold) [43]. There is also evidence for a racial predilection for male breast cancer with black men disproportionately affected, and diagnosed at an earlier age with poorer outcomes as compared to non-Hispanic white men [45,46]. Like their female counterparts, men of Ashkenazi Jewish descent also have an increased risk for breast cancer [47,48].

A relative excess of estrogen in relation to androgens secondary to a variety of causes has also been shown to increase the risk for male breast cancer. Exogenous estrogen exposure, Klinefelter syndrome, liver disease, testicular abnormalities, and obesity have all been implicated in the development of male breast cancer [1,49]. In particular, Klinefelter syndrome (excess X chromosomes, usually 47-XXY karyotype) confers a 16- to 19-fold increased risk for breast carcinoma [49–51]. Gynecomastia, an important imaging finding to distinguish from male breast cancer and related to a relative estrogen excess in males, increases the risk of male breast cancer approximately 5- to 10-fold in some studies [49,51]. Interestingly, in a recent study by Coopey and colleagues, atypical ductal hyperplasia identified on excision or mastectomy specimens for gynecomastia did not appear to elevate the risk for male breast cancer as it does in women [52]; the authors note that the reasoning behind this result was uncertain.

A few environmental exposures have been linked to the incidence of male breast cancer. Radiation exposure, a known risk factor for many types of cancers, has been shown to increase the risk for male breast cancer. This finding was demonstrated in studies of atomic bomb survivors [53,54], but also for diagnostic and therapeutic ionizing radiation [55]. Much smaller effects have been demonstrated for exposure to high temperature environments and exhaust fumes (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), and electromagnetic fields [10].

3. Potential Benefits of Image-Based Screening of High Risk Men

There are several potential benefits for screening men at an elevated risk for male breast cancer (Table 3). First, the sensitivity of mammographic screening for men is expected to be high secondary to the predominantly fatty male breast tissue. The detection of malignancy in females is hampered by denser and more diffuse fibroglandular tissue [56,57]. In males, however, the diagnostic performance in the setting of clinical symptoms demonstrates mammography to be highly sensitive and specific, with a high negative predictive value [17,18,20,22,23].

Table 3.

Benefits and drawbacks of image-based screening for men at high-risk for breast cancer

| Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|

| • Mammography in males confers a high sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value • Lifetime risk for specific populations of males may approach the average risk for women • Earlier detection of a disease that frequently presents as locally advanced |

• No established screening regimen • No current data to support the practice of routine screening • Increased costs associated with screening for a low prevalence disease • Radiation exposure |

Second, there may be subpopulations of men with particularly high risk who may benefit more from routine mammographic screening. For example, men with known BRCA genetic mutations, particularly BRCA2 mutations, have a lifetime risk as high as 8% [16]. This level of risk approaches the lifetime risk for average women of 12%, and some authors have proposed that these men undergo mammographic screening [33,58]. The subpopulation of men with the next highest risk for breast cancer are those with a personal history of male breast cancer. The estimated risk for a subsequent male breast cancer is just under 2% [42–44,59]. It is likely that this particular group of men, given the heightened awareness surrounding their diagnosis are already being screened with mammography. There is increasing evidence [60,61] to show that screening is increasingly being utilized and that it confers a high cancer detection rate (CDR) for men with a known BRCA genetic mutation, Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, a strong family history, or a personal history of breast cancer. For example, Marino, et al. found a CDR of 4.9/1000 while Gao, et al. found a CDR of 18/1000. The reason for the variability in CDR is unknown, however, the studies differed in the proportion of men in each high-risk category.

Finally, screening asymptomatic high-risk men introduces the potential for earlier detection of a disease that is often locally advanced when detected clinically. Recent research based on data from 2004 to 2014 [9] demonstrates that there is a persistent disparity in survival rate for men with breast cancer even after accounting for age, race, clinical and treatment factors, and access to care. Earlier detection could result in down staging at diagnosis and subsequently decrease mortality, both of which are known to be elevated in male breast cancer. In addition, earlier detection may allow patients to decrease rates of locoregional disease, providing patients with the option of breast conserving therapy as opposed to mastectomy for the standard of surgical care [62,63]. Although mastectomy has been the mainstay for surgical treatment of male breast cancer, breast conservation is increasingly being considered as a therapeutic option [64–66]. In addition, males do not typically have lobules, and present with masses (sometimes with associated calcifications [19,67]; Figure 3a-c) on mammography. One review has suggested that mammographic screening earlier in the development of male breast cancer may more frequently demonstrate calcifications [16] as ductal carcinoma in situ is the predominant precursor lesion present in almost half of male patients with invasive carcinoma [68].

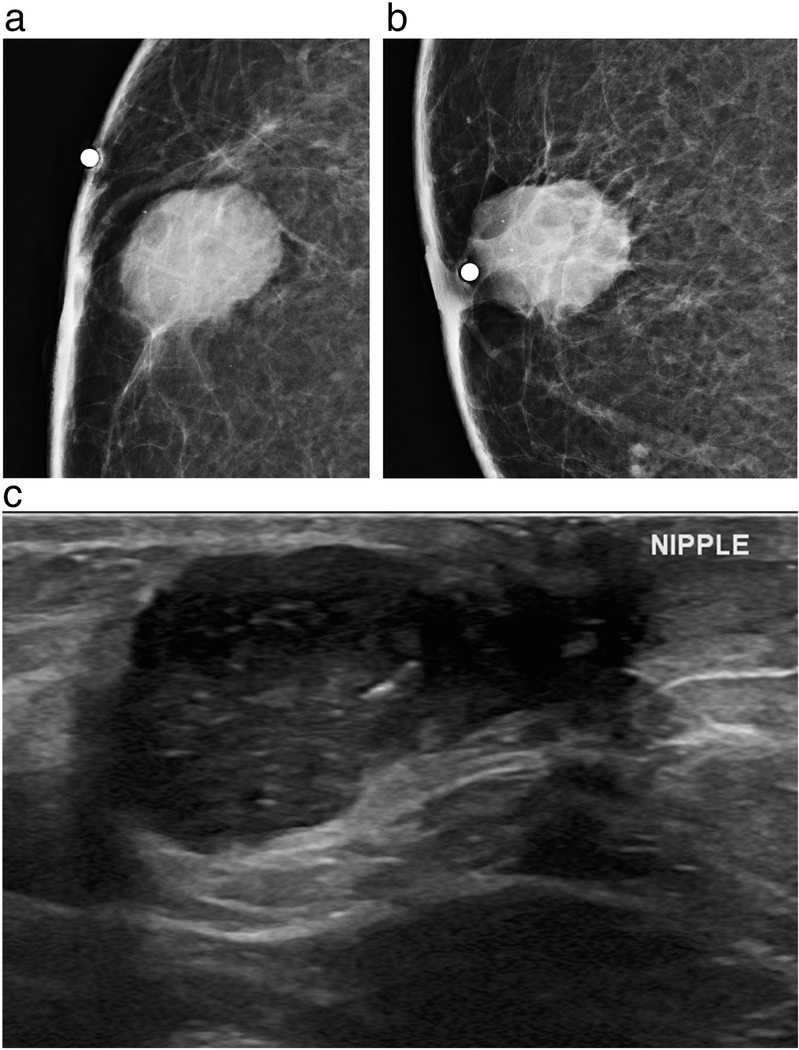

Figure 3a-c.

63-year-old male presents with a non-tender palpable right breast mass that was noticed for several months. Right cropped magnified craniocaudal (a) and mediolateral oblique (b) mammograms demonstrate Mammographically, there is a 24 mm oval subareolar mass with indistinct margins containing fine pleomorphic calcifications underlying a radioopaque BB marker. Ultrasound (c) demonstrates a corresponding hypoechoic mass with circumscribed and indistinct margins with extension into the subareolar region. Ultrasound guided core needle biopsy revealed grade 3, ER positive, PR positive, HER2 positive invasive ductal carcinoma.

There is currently no published evidence for screening with ultrasound or MRI in men, although as adjunct to mammographic screening these modalities have demonstrated a benefit for women [69–72]. However, the benefit of supplemental screening may be dependent on the level of risk [73], which would be particularly low for asymptomatic, average-risk men. Breast density may also impact the value of supplemental screening as men have breast tissue that is primarily fatty.

4. Possible Drawbacks of Screening High Risk Men

There is no established screening regimen for males, and no research has been conducted to determine the optimal screening strategy in this population as men are not typically screened. Although there is interest in improving research to inform prevention, early detection and management of male breast cancer [24], there have been no studies evaluating the impact of image-based screening on survival or disease-specific mortality. In regards to mammography, one potential confounder of mammographic screening in men is the presence of gynecomastia, seen in approximately 50% of asymptomatic males, and in up to 60% of men presenting with a symptom [16,74–76]; however, this is not typically a diagnostic challenge. The presence of gynecomastia may, however, increase rate of false positives, a known limitation of screening in women. In addition, when considering any screening program, which utilizes ionizing radiation, the potential risks associated with increased radiation exposure must be considered.

Finally, there are costs associated with establishing and maintaining a screening program for this population. This is especially pertinent when considering non-mammographic imaging tools for screening. For example, screening with MRI would be very costly as has been demonstrated in women [77]. Diagnostic performance in relation to the pathology of male breast cancer should also be considered. For example, screening with ultrasound would likely fail to diagnose the nearly 2% of male breast cancers that present solely as calcifications [19].

5. Conclusion

Male breast cancer is a rare malignancy comprising a small proportion of the total number of new breast malignancies diagnosed annually. There are currently no guidelines or data supporting screening men of average risk for male breast cancer. Although clinical breast exam is promoted as a screening tool for men with BRCA mutations, there are no recommendations from any organization for routine image-based screening for high-risk men.

Based on this review of the current literature we believe that the potential benefits of screening mammography (high sensitivity, elevated risk in certain subpopulations, and earlier detection) outweigh the potential drawbacks of false positives, cost, and radiation exposure. Screening mammography is increasingly being utilized and it confers a high cancer detection rate (CDR) for men with a known BRCA genetic mutation, Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, a strong family history, or a personal history of breast cancer. At a minimum, the CDR for screening in high risk men is on par with the CDR for screening in average risk women, or potentially higher.

We believe that a screening program for these subpopulations of high-risk men offers the best chances for early detection of a disease that disproportionately presents with advanced or metastatic disease. Further research, potentially including data from large national or international registries or meta-analyses of large single institutional studies, may further support and establish a mortality benefit from image-based screening in high risk men and would most powerfully support the widespread adoption of high-risk screening.

References

- [1].Giordano SH. Breast Cancer in Men. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2311–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:7–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Liu N, Johnson KJ, Ma CX. Male Breast Cancer: An Updated Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Data Analysis. Clin Breast Cancer 2018;18:e997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Speirs V, Shaaban AM. The rising incidence of male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;115:429–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Stang A, Thomssen C. Decline in breast cancer incidence in the United States: what about male breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2008;112:595–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Giordano SH, Cohen DS, Buzdar AU, Perkins G, Hortobagyi GN. Breast carcinoma in men: a population-based study. Cancer 2004;101:51–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Greif JM, Pezzi CM, Klimberg VS, Bailey L, Zuraek M. Gender differences in breast cancer: analysis of 13,000 breast cancers in men from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:3199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang F, Shu X, Meszoely I, Pal T, Mayer IA, Yu Z, et al. Overall Mortality After Diagnosis of Breast Cancer in Men vs Women. JAMA Oncol 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN. Male breast cancer. Lancet 2006;367:595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tabár L, Vitak B, Chen TH-H, Yen AM-F, Cohen A, Tot T, et al. Swedish two-county trial: impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality during 3 decades. Radiology 2011;260:658–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hellquist BN, Duffy SW, Abdsaleh S, Björneld L, Bordás P, Tabár L, et al. Effectiveness of population-based service screening with mammography for women ages 40 to 49 years: evaluation of the Swedish Mammography Screening in Young Women (SCRY) cohort. Cancer 2011;117:714–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015. SEER; 2018. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2015/ (accessed May 27, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Morrogh M, King TA. The significance of nipple discharge of the male breast. Breast J 2009;15:632–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Muñoz Carrasco R, Álvarez Benito M, Rivin del Campo E. Value of mammography and breast ultrasound in male patients with nipple discharge. Eur J Radiol 2013;82:478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gao Y, Heller SL, Moy L. Male Breast Cancer in the Age of Genetic Testing: An Opportunity for Early Detection, Tailored Therapy, and Surveillance. Radiographics 2018;38:1289–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Evans GF, Anthony T, Turnage RH, Schumpert TD, Levy KR, Amirkhan RH, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of mammography in the evaluation of male breast disease. Am J Surg 2001;181:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Expert Panel on Breast Imaging:, Niell BL, Lourenco AP, Moy L, Baron P, Didwania AD, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Evaluation of the Symptomatic Male Breast. J Am Coll Radiol 2018;15:S313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mathew J, Perkins GH, Stephens T, Middleton LP, Yang W-T. Primary breast cancer in men: clinical, imaging, and pathologic findings in 57 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;191:1631–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Muñoz Carrasco R, Alvarez Benito M, Muñoz Gomariz E, Raya Povedano JL, Martínez Paredes M. Mammography and ultrasound in the evaluation of male breast disease. Eur Radiol 2010;20:2797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen L, Chantra PK, Larsen LH, Barton P, Rohitopakarn M, Zhu EQ, et al. Imaging characteristics of malignant lesions of the male breast. Radiographics 2006;26:993–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Foo ET, Lee AY, Ray KM, Woodard GA, Freimanis RI, Joe BN. Value of diagnostic imaging for the symptomatic male breast: Can we avoid unnecessary biopsies? Clin Imaging 2017;45:86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Patterson SK, Helvie MA, Aziz K, Nees AV. Outcome of men presenting with clinical breast problems: the role of mammography and ultrasound. Breast J 2006;12:418–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Korde LA, Zujewski JA, Kamin L, Giordano S, Domchek S, Anderson WF, et al. Multidisciplinary meeting on male breast cancer: summary and research recommendations. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2114–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jain S, Gradishar WJ. Male Breast Cancer. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne CK, editor. Diseases of the Breast, Wolters Kluwer Health; 2014, p. 974–80.e2. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Can Breast Cancer in Men Be Found Early? n.d. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer-in-men/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html (accessed May 15, 2019).

- [27].NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2018. n.d.

- [28].American Cancer Society | Cancer Facts & Statistics. American Cancer Society | Cancer Facts & Statistics n.d. https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/#!/cancer-site/Breast?module=91Q4dqjU (accessed May 17, 2019).

- [29].Tai YC, Domchek S, Parmigiani G, Chen S. Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:1811–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Beitsch PD, Whitworth PW, Hughes K, Patel R, Rosen B, Compagnoni G, et al. Underdiagnosis of Hereditary Breast Cancer: Are Genetic Testing Guidelines a Tool or an Obstacle? J Clin Oncol 2019;37:453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Consensus Guideline on Genetic Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer. American Society of Breast Surgeons; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Freedman BC, Keto J, Rosenbaum Smith SM. Screening mammography in men with BRCA mutations: is there a role? Breast J 2012;18:73–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Basham VM, Lipscombe JM, Ward JM, Gayther SA, Ponder BAJ, Easton DF, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based study of male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2002;4:R2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ottini L, Masala G, D’Amico C, Mancini B, Saieva C, Aceto G, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation status and tumor characteristics in male breast cancer: a population-based study in Italy. Cancer Res 2003;63:342–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ding YC, Steele L, Kuan C-J, Greilac S, Neuhausen SL. Mutations in BRCA2 and PALB2 in male breast cancer cases from the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;126:771–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, et al. , editors. GeneReviews®, Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Brewer HR, Jones ME, Schoemaker MJ, Ashworth A, Swerdlow AJ. Family history and risk of breast cancer: an analysis accounting for family structure. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017;165:193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Barnard ME, Boeke CE, Tamimi RM. Established breast cancer risk factors and risk of intrinsic tumor subtypes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015;1856:73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hemminki K, Granström C, Czene K. Attributable risks for familial breast cancer by proband status and morphology: a nationwide epidemiologic study from Sweden. Int J Cancer 2002;100:214–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Brinton LA, Richesson DA, Gierach GL, Lacey JV Jr, Park Y, Hollenbeck AR, et al. Prospective evaluation of risk factors for male breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1477–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Dong C, Hemminki K. Second primary breast cancer in men. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;66:171–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Auvinen A, Curtis RE, Ron E. Risk of subsequent cancer following breast cancer in men. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:1330–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Satram-Hoang S, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Risk of second primary cancer in men with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2007;9:R10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].O’Malley C, Shema S, White E, Glaser S. Incidence of male breast cancer in california, 1988–2000: racial/ethnic variation in 1759 men. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005;93:145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sineshaw HM, Freedman RA, Ward EM, Flanders WD, Jemal A. Black/White Disparities in Receipt of Treatment and Survival Among Men With Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Brenner B, Fried G, Levitzki P, Rakowsky E, Lurie H, Idelevich E, et al. Male breast carcinoma in Israel: higher incident but possibly prognosis in Ashkenazi Jews. Cancer 2002;94:2128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rubinstein WS. Hereditary breast cancer in Jews. Fam Cancer 2004;3:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Brinton LA, Carreon JD, Gierach GL, McGlynn KA, Gridley G. Etiologic factors for male breast cancer in the U.S. Veterans Affairs medical care system database. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010;119:185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Swerdlow AJ, Schoemaker MJ, Higgins CD, Wright AF, Jacobs PA, UK Clinical Cytogenetics Group. Cancer incidence and mortality in men with Klinefelter syndrome: a cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:1204–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Brinton LA, Cook MB, McCormack V, Johnson KC, Olsson H, Casagrande JT, et al. Anthropometric and hormonal risk factors for male breast cancer: male breast cancer pooling project results. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:djt465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Coopey SB, Kartal K, Li C, Yala A, Barzilay R, Faulkner HR, et al. Atypical ductal hyperplasia in men with gynecomastia: what is their breast cancer risk? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;175:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ron E, Ikeda T, Preston DL, Tokuoka S. Male breast cancer incidence among atomic bomb survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:603–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Little MP, McElvenny DM. Male Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality Risk in the Japanese Atomic Bomb Survivors - Differences in Excess Relative and Absolute Risk from Female Breast Cancer. Environ Health Perspect 2017;125:223–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Thomas DB, Rosenblatt K, Jimenez LM, McTiernan A, Stalsberg H, Stemhagen A, et al. Ionizing radiation and breast cancer in men (United States). Cancer Causes Control 1994;5:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Phi X-A, Tagliafico A, Houssami N, Greuter MJW, de Bock GH. Digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer screening and diagnosis in women with dense breasts - a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2018;18:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].D’Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA. ACR BI-RADS atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. American College of Radiology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Brenner RJ, Weitzel JN, Hansen N, Boasberg P. Screening-detected breast cancer in a man with BRCA2 mutation: case report. Radiology 2004;230:553–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hemminki K, Granström C. Re: Risk of subsequent cancer following breast cancer in men. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gao Y, Goldberg JE, Young TK, Babb JS, Moy L, Heller SL. Breast Cancer Screening in High-Risk Men: A 12-Year Longitudinal Observational Study of Male Breast Imaging Utilization and Outcomes. Radiology 2019:190971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Marino MA, Gucalp A, Leithner D, Keating D, Avendano D, Bernard-Davila B, et al. Mammographic screening in male patients at high risk for breast cancer: is it worth it? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019;177:705–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Golshan M, Rusby J, Dominguez F, Smith BL. Breast conservation for male breast carcinoma. Breast 2007;16:653–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Fentiman IS. Surgical options for male breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2018;172:539–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Giordano SH. Lumpectomy in male patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:2460–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Cloyd JM, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wapnir IL. Outcomes of partial mastectomy in male breast cancer patients: analysis of SEER, 1983–2009. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:1545–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Bratman SV, Kapp DS, Horst KC. Evolving trends in the initial locoregional management of male breast cancer. Breast 2012;21:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Quimet-Oliva D, Hebert G, Ladouceur J. Radiographic characteristics of male breast cancer. Radiology 1978;129:37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Doebar SC, Slaets L, Cardoso F, Giordano SH, Bartlett JM, Tryfonidis K, et al. Male breast cancer precursor lesions: analysis of the EORTC 10085/TBCRC/BIG/NABCG International Male Breast Cancer Program. Mod Pathol 2017;30:509–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB, Mendelson EB, Lehrer D, Böhm-Vélez M, et al. Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer. JAMA 2008;299:2151–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Berg WA, Bandos AI, Mendelson EB, Lehrer D, Jong RA, Pisano ED. Ultrasound as the Primary Screening Test for Breast Cancer: Analysis From ACRIN 6666. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Bae MS, Sung JS, Han W, Bernard-Davila B, Bara FR, Sutton EJ, et al. Survival outcomes of screening with breast MRI in high-risk women. J Clin Orthod 2017;35:1508–1508. [Google Scholar]

- [72].Chiarelli AM, Prummel MV, Muradali D, Majpruz V, Horgan M, Carroll JC, et al. Effectiveness of screening with annual magnetic resonance imaging and mammography: results of the initial screen from the ontario high risk breast screening program. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2224–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Sippo DA, Burk KS, Mercaldo SF, Rutledge GM, Edmonds C, Guan Z, et al. Performance of Screening Breast MRI across Women with Different Elevated Breast Cancer Risk Indications. Radiology 2019:181136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Andersen JA, Gram JB. Male breast at autopsy. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand A 1982;90:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Fentiman IS. Managing Male Mammary Maladies. Eur J Breast Health 2018;14:5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hines SL, Tan WW, Yasrebi M, DePeri ER, Perez EA. The role of mammography in male patients with breast symptoms. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Saadatmand S, Tilanus-Linthorst MMA, Rutgers EJT, Hoogerbrugge N, Oosterwijk JC, Tollenaar RAEM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening women with familial risk for breast cancer with magnetic resonance imaging. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1314–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DEC, Rosen B, Bradley L, Fan I, et al. Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: a kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:1694–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Wasielewski M, den Bakker MA, van den Ouweland A, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Portengen H, Klijn JGM, et al. CHEK2 1100delC and male breast cancer in the Netherlands. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;116:397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Meijers-Heijboer H, van den Ouweland A, Klijn J, Wasielewski M, de Snoo A, Oldenburg R, et al. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2(*)1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Nat Genet 2002;31:55–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Brinton LA, Key TJ, Kolonel LN, Michels KB, Sesso HD, Ursin G, et al. Prediagnostic Sex Steroid Hormones in Relation to Male Breast Cancer Risk. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2041–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]