Abstract

Climate warming is anticipated to make high latitude ecosystems stronger C sinks through increasing plant production. This effect might, however, be dampened by insect herbivores whose damage to plants at their background, non-outbreak densities may more than double under climate warming. Here, using an open-air warming experiment among Subarctic birch forest field layer vegetation, supplemented with birch plantlets, we show that a 2.3 °C air and 1.2 °C soil temperature increase can advance the growing season by 1–4 days, enhance soil N availability, leaf chlorophyll concentrations and plant growth up to 400%, 160% and 50% respectively, and lead up to 122% greater ecosystem CO2 uptake potential. However, comparable positive effects are also found when insect herbivory is reduced, and the effect of warming on C sink potential is intensified under reduced herbivory. Our results confirm the expected warming-induced increase in high latitude plant growth and CO2 uptake, but also reveal that herbivorous insects may significantly dampen the strengthening of the CO2 sink under climate warming.

Subject terms: Climate-change ecology, Ecosystem ecology, Carbon cycle

Warming is expected to increase C sink capacity in high-latitude ecosystems, but plant-herbivore interactions could moderate or offset this effect. Here, Silfver and colleagues test individual and interactive effects of warming and insect herbivory in a field experiment in Subarctic forest, showing that even low intensity insect herbivory strongly reduces C sink potential.

Introduction

Temperature is one of the key factors that control CO2 exchange between the ecosystem and the atmosphere. In high latitude ecosystems, climate warming directly stimulates plant production by providing a warmer environment and longer growing season for CO2 fixation1,2, but also indirectly by accelerating decomposition and nutrient release for plant uptake3,4. If plant growth is enhanced more than decomposition, ecosystems become stronger C sinks5. Avian6–9 and mammalian10,11 grazers are known to significantly suppress gross primary production (GPP) in Arctic ecosystems by consuming plant photosynthetic tissues and changing plant community structure. Grazing can limit the positive response of plant production and CO2 uptake to climate warming in grazed areas7,10, although the ecosystems in general may be greening12,13 and their growing season C uptake increasing13,14. Recent evidence further suggests that when occurring at outbreak densities, herbivorous insects can dramatically suppress GPP in the Arctic15. Herbivorous insects are ubiquitous however, and even at their background, non-outbreak densities, can annually consume 1–15% of plant foliage16–18 and contribute to nutrient cycling in ecosystems19. Minor chronic herbivory can reduce plant growth20,21 and in the long-term, background herbivory may have a stronger effect on woody plant growth than the devastating, short-term outbreaks22,23. However, while there are studies of the effects of insect herbivory on leaf chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis rates at high latitudes22,24, no study has yet examined how background insect herbivory influences ecosystem–atmosphere CO2 exchange in these areas.

Both paleontological data from past intervals of significant climate change25 and observations along latitudinal16,26–29 and elevational30 gradients indicate increasing insect herbivory with warming. The positive association between the warmest summer month temperature and the level of herbivore damage seems to be particularly strong in cold-limited, high latitude ecosystems16,26–29. Here, we provide evidence that background insect herbivory can significantly weaken the CO2 uptake potential of a Subarctic mountain birch forest ecosystem and off-set the strengthening of C sink under climate warming (Fig. 1). Our results are from an open-air warming experiment, established at the Kevo Subarctic Research Institute, North Finland (69°45.4′N, 27°00.5′E) in 2016 when 20 plots (1 × 0.75 m2), each containing intact field layer vegetation but no adult trees, were created. Twelve Betula plantlets (including local Betula nana and Betula pubescens subsp. czerepanovii and currently slightly more southern Betula pendula and B. pubescens) were planted within field layer vegetation in each plot to include Subarctic woody species in the experiment and to have controlled and well replicated plant material to accurately follow treatment responses. During the periods of warming (May–November), green metal plates (mimicking plant leaves) were heated to approximately 3.3 °C above ambient temperature in half of the plots, using infrared ceramic heaters. Heating was controlled by real-time, replicated temperature measurements in the control and heated plots, and led to approximately 2.3 °C warmer moving air and 1.2 °C warmer soil in the heated plots. Following a fully factorial 2 × 2 set-up (two levels of warming and two levels of herbivory yielding four warming × herbivory combinations with n = 5 for each), half of the plots were also sprayed weekly using an insecticide to reduce insect herbivory. We measured the ecosystem–atmosphere CO2 fluxes in each plot with static chambers through two remarkably different growing seasons, and to explain the observed patterns in fluxes, we surveyed: the phenology, shoot growth, leaf chlorophyll content, and damage of Betula plantlets; soil microbial biomass and mineral N availability; and abiotic attributes such as air and soil temperature and moisture. Our results reveal that warming increases the CO2 uptake potential in Subarctic ecosystems, but also that the generally minor background insect herbivory can strikingly control the CO2 exchange, in both present and future climates. Thus, the CO2 uptake of high-latitude ecosystems in the future likely depends not only on the magnitude of temperature rise, but also on the levels of insect herbivory.

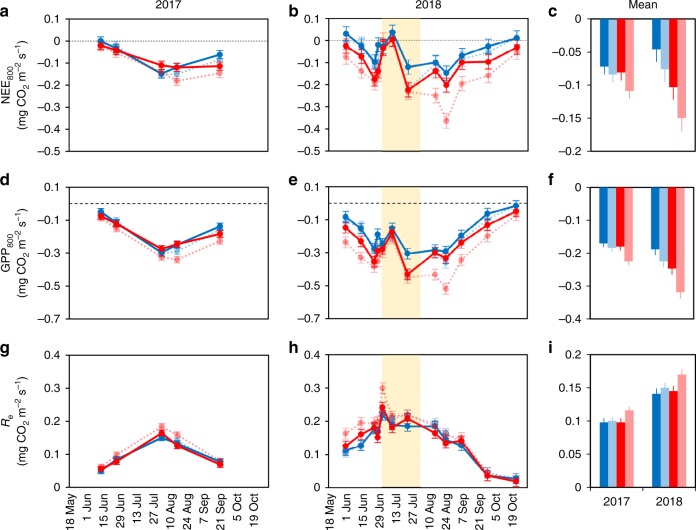

Fig. 1. Warming and reduction in herbivory increase GPP and ecosystem CO2 uptake potential.

Left hand and middle panels show the variation in daytime CO2 fluxes: a, b net ecosystem exchange NEE800, d, e gross primary production GPP800, and g, h ecosystem respiration Re in warmed (red) and ambient (blue) field plots of Subarctic mountain birch forest field layer vegetation (supplemented with cloned birch plantlets) during growing seasons 2017 and 2018 (dots are estimated marginal means ± s.e.m. produced by the fitted statistical model in Table 2; n = 5 field plots). Right hand panels show seasonal means ± s.e.m. of c NEE800, f GPP800, and i Re (means are estimated marginal means produced by the fitted statistical model in Table 2, n = 5 field plots examined over 5 [year 2017] or 12 [year 2018] repeated measures). Light tone dashed lines, symbols, and bars denote plots, where herbivory was reduced using an insecticide. The pale yellow background stripe stands for the period of severe hydrological stress (2nd July–1st August, 2018; see Fig. 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Results and discussion

Warming, insect herbivory, and CO2 fluxes

At high latitudes, the level of background insect herbivory is typically low26,29. In accordance with this, the herbivore damage of our experimental Betula plantlets was only 2–20% of the damage earlier observed ca. 1000 km south of our site20,21. On average, 26% of all Betula leaves in our control plots with natural herbivory were wounded by insects in 2017 (Supplementary Table 1). The observed damage index was low (Fig. 2d) as most of the damaged leaves had only 1–4% of their leaf area damaged (Supplementary Table 1). This finding corresponds well with earlier estimates of 1–2% of Betula leaf area damaged due to background herbivory at high latitudes26,29. However, despite such a low level of damage, the 67% reduction in mean leaf damage index (Fig. 2d and Table 1), achieved by the insecticide treatment in our study, had a remarkably strong effect on the ecosystem C uptake potential. The estimates of daytime CO2 fluxes showed that reducing leaf damage by two-thirds increased the ecosystem C sink potential by, on average, 26% and 52% in 2017 and 2018, respectively (i.e., the potential net ecosystem exchange [NEE800] of CO2 was more negative with reduced herbivory; Fig. 1a–c and Table 2). These values are similar to the 22 and 107% increase in C sink potential due to the experimental warming (Fig. 1a–c and Table 2) and provide, to our knowledge, the first evidence that the seemingly low background herbivory can significantly affect CO2 uptake in Subarctic ecosystems.

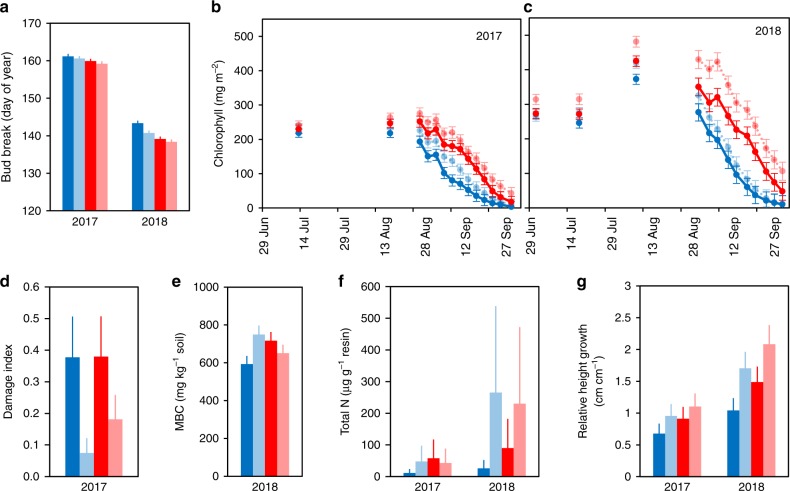

Fig. 2. Longer growing seasons and enhanced soil mineral N explain better plant growth under warming and reduced herbivory.

Birch plantlets had a earlier spring bud break (Supplementary Table 3; for each mean n = 57–60 plantlets growing in 5 replicate field plots) and b, c higher leaf chlorophyll content in summer and autumn (Supplementary Table 4; for each dot in 2017 n = 57–60 and for each dot in 2018 n = 39–60 plantlets growing in 5 replicate field plots) in plots with warming (red symbols) and reduced herbivory (light tone symbols), compared to plots with ambient temperature (blue symbols) and natural herbivory (dark tone symbols), which responses together resulted in longer growing seasons. As warming did not increase d leaf herbivore damage (Table 1; for each mean n = 57–60 plantlets growing in 5 replicate field plots), these effects together with greater e soil microbial biomass carbon, MBC (Supplementary Table 5; n = 5 field plots, each examined at 3 depths of soil) and f resin bag mineral N (NH4+ and NO3−) capture (Supplementary Table 5; n = 5 field plots) under warming and reduced herbivory, apparently explain the increased g relative growth of birch plantlets (Supplementary Table 3; for each mean n = 57–60 plantlets growing in 5 replicate field plots) under these treatments, which in turn likely explains the patterns observed in the CO2 exchange of the entire field layer vegetation (Table 2 and Fig. 1). All means are estimated marginal means (±s.e.m.) produced by the fitted statistical models in Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 3–5. Means and errors for MBC were back-transformed from square root-transformed data and those for leaf damage index, plant growth, and total soil mineral N from log-transformed data. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Table 1.

Statistics of warming and herbivory effects on leaf damage index.

| F | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Soil OM content | 0.3 | 0.563 |

| Vascular plant cover | 0.0 | 0.970 |

| Lichen cover | 2.8 | 0.096 |

| Moss cover | 0.8 | 0.362 |

| Warming (W) | 3.1 | 0.079 |

| Herbivory reduction (H) | 42.7 | <0.001 |

| Betula species (S) | 5.6 | 0.023 |

| W × H | 3.5 | 0.062 |

| W × S | 0.8 | 0.471 |

| H × S | 0.5 | 0.662 |

| W × H × S | 3.5 | 0.016 |

The data collected in 2017 was log-transformed and analyzed using linear mixed models and Type I ANOVA (with two-sided significance tests). OM content and the areal cover of vascular plants, mosses, and lichens were treated as covariates and added to models to remove plot-to-plot variation that might otherwise confound the treatment effects. Field replicate block and birch genotype (nested within species) were included in the models as random effects, but are not reported. N = 234 experimental birch plantlet. F and P indicate F-statistics and P-values respectively; P < 0.05 are in bold.

Table 2.

Statistics of warming and herbivory effects on NEE800, GPP800, and Re in 2017–2018.

| NEE800 F | NEE800 P | GPP800 F | GPP800 P | Re F | Re P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | ||||||

| Soil OM content | 0.2 | 0.687 | 6.8 | 0.026 | 41.0 | <0.001 |

| Vascular plant cover | 9.3 | 0.014 | 29.2 | <0.001 | 42.6 | <0.001 |

| Lichen cover | 20.5 | 0.001 | 8.4 | 0.015 | 27.4 | 0.001 |

| Moss cover | 1.8 | 0.211 | 0.1 | 0.712 | 7.6 | 0.024 |

| Date (D) | 46.5 | <0.001 | 121 | <0.001 | 136 | <0.001 |

| Warming (W) | 2.0 | 0.190 | 4.6 | 0.062 | 3.1 | 0.119 |

| Herbivory reduction (H) | 5.7 | 0.043 | 13.2 | 0.006 | 11.6 | 0.010 |

| W × H | 1.0 | 0.352 | 3.5 | 0.094 | 7.0 | 0.030 |

| W × D | 2.9 | 0.029 | 1.3 | 0.282 | 1.3 | 0.286 |

| H × D | 1.1 | 0.355 | 1.6 | 0.188 | 0.8 | 0.541 |

| W × H × D | 0.2 | 0.916 | 0.5 | 0.766 | 0.3 | 0.891 |

| 2018 | ||||||

| Soil OM content | 0.02 | 0.895 | 2.4 | 0.153 | 10.2 | 0.011 |

| Vascular plant cover | 0.7 | 0.411 | 8.8 | 0.014 | 26.6 | 0.001 |

| Lichen cover | 8.2 | 0.016 | 3.5 | 0.085 | 2.0 | 0.185 |

| Moss cover | 5.2 | 0.046 | 7.6 | 0.018 | 2.8 | 0.125 |

| Date (D) | 31.5 | <0.001 | 60.8 | <0.001 | 87.4 | <0.001 |

| Warming (W) | 13.2 | 0.006 | 13.9 | 0.004 | 1.6 | 0.239 |

| Herbivory reduction (H) | 8.3 | 0.020 | 13.1 | 0.006 | 7.3 | 0.033 |

| W × H | 0.4 | 0.534 | 1.3 | 0.280 | 1.7 | 0.238 |

| W × D | 1.5 | 0.129 | 1.2 | 0.264 | 2.4 | 0.008 |

| H × D | 1.3 | 0.215 | 1.3 | 0.223 | 0.4 | 0.944 |

| W × H × D | 1.5 | 0.154 | 1.4 | 0.158 | 0.7 | 0.775 |

Treatment effects on net ecosystem exchange (NEE800), gross primary production (GPP800), and ecosystem respiration (Re) were tested using repeated measures linear mixed models and Type I ANOVA (with two-sided significance tests), where the variance is allocated to explanatory variables in the order of their appearance. Soil organic matter (OM) content and cover of vascular plants, lichens, and mosses are continuous variables that describe the variation among the experimental plots prior to the establishment of the experiment. They were used in the models as covariates to remove plot-to-plot variation that might otherwise confound the treatment effects. Years were analyzed separately (N = 100 for 2017, N = 240 for 2018). Date was treated as a repeated measure, warming and herbivory reduction as fixed effects, and treatment block (not reported) as a random effect. F and P indicate F-statistics and P-values respectively; P < 0.05 are in bold.

Warming and herbivory effects on NEE800 increased with time: the warming effect was more pronounced in the late rather than the early growing season in 2017 (significant date × warming interaction; Table 2 and Fig. 1a), and in 2018, warming increased ecosystem C sink throughout the season, except during the heat wave (Figs. 1b and 3b). Increased treatment effects likely originate from the cumulative size differences between the plants in control and treatment plots (Fig. 2g). Supporting earlier studies with avian7,8 and mammalian10,11 herbivores, we found that shifts in NEE800 were mainly driven by shifts in GPP800 (Fig. 1a–f), although ecosystem respiration (Re) was also affected by the treatments (Table 2 and Fig. 1g–i).

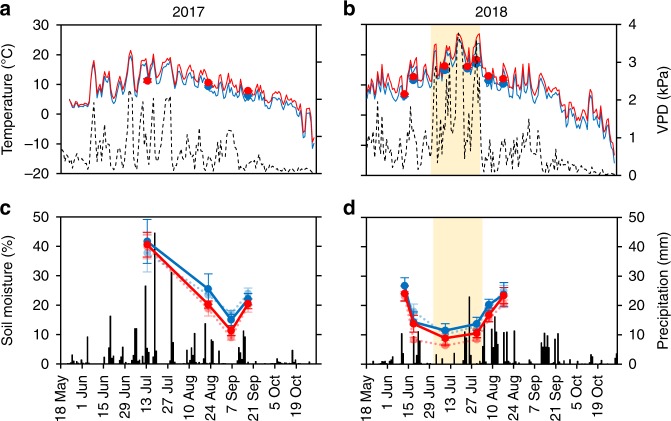

Fig. 3. Abiotic attributes during periods of warming in 2017 and 2018.

a, b Air temperature (solid lines are mean daily temperatures of warmed [red] and ambient [blue] plots, n = 3 field plots), soil temperature (dots are mean ± s.e.m. of warmed [red] and ambient [blue] plots, n = 10 field plots, each examined through 3–5 within-plot measurements) and daily maximum of atmospheric water vapor pressure deficit (VPD; dashed black line); c, d soil moisture (dots are means ± s.e.m. of warmed [red] and ambient [blue] plots, light tone dashed lines and symbols denote plots, where herbivory was reduced using insecticide; n = 5 field plots, each examined through 3–5 within-plot measurements) and daily precipitation (thin black bars). Precipitation and VPD data are from the Kevo weather station (Finnish Meteorological Institute), located 200 m from the experimental site. The pale yellow background stripe stands for the period of severe hydrological stress (2nd July–1st August, 2018). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Earlier observations in Fennoscandia show that B. pubescens foliar damage increases from 1–2 to 5–7% of leaf area eaten along a latitudinal gradient from 70°N to 60°N26. This gradient climatically roughly equals the predicted warming in the next 100 years31. A similar gradient of increasing leaf damage has also been found for B. pendula26, and together these observations suggest that leaf damage may more than double in northern birch forests during the expected warming. Mathematical simulations produce similar trends, but with a wide range of magnitude: for a Betula glandulosa–nana complex a 20% increase in leaf damage is predicted along a 3 °C increase in temperature in the Arctic29 and for B. pubescens a 30–450% increase along a 1.7 °C increase in Scandes and a 50–200% increase along a 3.5 °C increase in Northern Russia32. Based on these observations and predictions, we expected higher leaf damage in our warmed plots, but warming did not increase leaf damage (Fig. 2d), except for B. pubescens under reduced herbivory (a significant warming × herbivore reduction × Betula species interaction effect in Table 1). Even this interaction effect is likely coincidental, since we found no main or interaction effects of warming on leaf damage when we repeated the damage survey in 2019 (Supplementary Table 2).

Although our results seem to suggest that earlier predictions of increasing herbivory with warmer climate16,25–30,32 would not hold when tested experimentally, this interpretation needs to be treated cautiously as treatment plots in field experiments are vulnerable to both congregation and avoidance of freely moving animals and may therefore tell little about the responses of herbivore abundances under large-scale climatic changes33. While this bias precludes reliable predictions of warming effects on future herbivory in our and other plot-level experiments33, experimental herbivory treatments, as the one in our study, can be used to predict and disentangle the effects of future changes in herbivore pressure on CO2 fluxes from those deriving directly from increasing temperatures.

Mechanisms behind the changes in CO2 fluxes

Our results reveal how warming and reduction in herbivory affected many of those plant traits and ecosystem properties that can control ecosystem C sink capacity through their effects on plant photosynthesis and growth. We found 1–4 days earlier bud break (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 3) and significantly later autumnal decline in leaf chlorophyll content in the warmed compared to control Betula plantlets (a significant date × warming interaction effect for both years; Supplementary Table 4 and Fig. 2b, c). This was expected, and accords with the satellite observations of prolonged growing seasons in high latitude ecosystems during the recent decades of warming2. More surprisingly, we also found a bilateral extension of the growing season in plantlets that had reduced herbivore load (Fig. 2a–c and Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). These results show that both warming and insect herbivory can have an impact on the length of the period when plants are able to grow and fix CO2 from the atmosphere. Considering the key role of N deficiency in limiting primary production at high latitudes4, another major finding from our study is that warming and herbivore reduction, alone and in combination, increased the availability of mineral N (sum of NH4+ and NO3−) in the soil by nearly 8-fold by the end of the second, full, growing season (Fig. 2f). Unexpectedly, reduced herbivory had a stronger effect on N mineralization than warming, and warming increased N availability under natural herbivory only (a significant warming × herbivore reduction interaction effect; Supplementary Table 5).

Warmer soil (Fig. 3a, b) can, as such, enhance microbial activity and nutrient mineralization34, but why would plant release from herbivory also lead to higher soil N availability? We propose here that the observed positive effects of both warming and herbivory reduction were, for the most part, linked to the 30% and 50% increase in plant growth, respectively, under these treatments (Fig. 2g). Recent evidence from a subalpine forest suggests that in N-limited environments, trees can sustain greater growth under warming by increasing fine root production and release of root exudates, which stimulate microbial activity and N mineralization in the soil35. As greater shoot growth is likely associated with higher belowground C allocation, such a feedback loop through priming of organic matter decomposition could logically explain our findings of improved mineral N availability in the plots with reduced herbivory and enhanced plant growth. Supporting this interpretation, we found greater microbial biomass in the soil in response to both warming and reduced herbivory (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Table 5). While these effects were not fully additive as microbial biomass and N availability were not highest in the combined warming-herbivory reduction treatment with the greatest plant growth (Fig. 2g), it is likely that the improved N availability in the soil led to higher chlorophyll content in summer leaves (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Table 4), which in turn enhanced the ecosystem C sink through greater GPP800 under warming and reduced herbivory (Fig. 1a–f).

Our results add to earlier findings, which suggest that plant growth in the Arctic is heavily controlled by low air and soil temperatures. For instance, in a study with comparable shrub dominated field layer vegetation, B. glandulosa had a 2.5-fold growth increase with 2.5 °C warmer air and 2.3 °C warmer soil36. Our study provides evidence that plant growth and C sink potential also seem to be heavily controlled by background insect herbivory. The availability of mineral N was negligible in our control plots (Fig. 2f), suggesting that plants at our site should be unable to compensate for losses in leaf mass. This was exactly the case; despite the low level of herbivory, the growth of Betula plantlets was remarkably slower under natural than reduced herbivory (Fig. 2g). One potential explanation for the extensive growth and GPP responses to herbivory reduction is that the leaf area where photosynthesis is deleteriously affected by folivory can be 6-fold in comparison to the actual consumed area37,38, possibly due to suppression of the efficiency of photosystem II in the remaining leaf tissue39. In northern deciduous trees, herbivory also commonly induces production of defence compounds such as phenolics40 and when herbivory is reduced, resources allocated to induced defence are likely to be used for growth. Reducing herbivory may also simultaneously reduce leaf pathogens41,42, leading to a more positive effect on GPP than could be predicted by purely measuring the reduction in herbivory damaged leaf area.

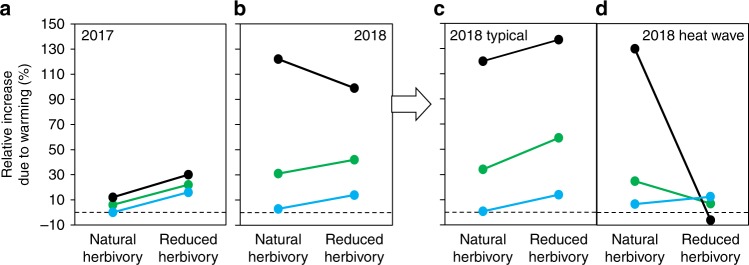

Insect herbivory impact under typical weather and heat wave

In line with the 50% increase in plant growth with herbivory reduction (Fig. 2g), we found that the relative increase in GPP800, NEE800, and Re due to warming was higher when herbivore pressure was reduced (Fig. 4a), although statistically significant warming × herbivory interaction effects were observed for Re only (Table 2 and Fig. 1g). In 2017, warming elevated GPP800 and NEE800 by, on average, 22% and 30%, respectively, when herbivory was reduced, but only by 6% and 12% under natural herbivory (Fig. 4a). These results suggest that plants were relatively better able to utilize the benefits of warming when insect herbivory was reduced, and as a result, the ecosystem acted as a stronger C sink. A similar pattern was not, however, observed for NEE800 in 2018, but instead, the mean relative increase in NEE800 was higher under natural herbivory (Fig. 4b). This change in the pattern seems to be related to differences in weather conditions between 2017 and 2018.

Fig. 4. Schematic illustrations of how herbivory modified the effects of warming on ecosystem CO2 exchange.

Year 2017 responses are shown as a overall means only while year 2018 responses are shown as both b overall means and split into two periods: c typical weather conditions and d a period of an extreme heat wave (pale yellow stripe in Figs. 1 and 3). The relative increase in gross primary production GPP800 (green dots), net ecosystem exchange NEE800 (black dots), and ecosystem respiration Re (blue dots) due to warming was higher when herbivore pressure was reduced in 2017 and in 2018 under typical weather conditions, but not during the 2018 heat wave. These responses suggest that plants with reduced herbivory benefited more from warming (in terms of CO2 fixing) than plants with natural herbivory under typical humid conditions, but not under the heat wave, apparently because of being more susceptible to hydrological stress due to greater size (Fig. 2g) and higher water consumption (Fig. 3d).

There was a month-long period of intense heat wave during the peak growing season in 2018. In July, the mean temperature was 5 °C higher and the total precipitation 10% lower than the long-term averages (Supplementary Table 6), soil moisture was low (Fig. 3d), and the daily maximum atmospheric water vapor pressure deficit (VPD) was frequently above 2.5 kPa (Fig. 3b), indicating severe moisture stress43. Of all our Betula plantlets, 19% died during the warmest days (July 18–20) despite irrigation (the amount of water given to plots each of the 3 nights corresponded to precipitation during a heavy thunderstorm). Notably, the drought was more extreme in plots with warming and reduced herbivory as shown by the lower soil moisture under these treatments (Fig. 3d; a marginally significant [P = 0.054] date × warming × herbivory reduction interaction effect in Supplementary Table 7), which likely resulted from the larger size and higher transpiration of plants in these plots.

As plant photosynthesis can be severely constrained by low soil moisture44 and high VPD43, we suggest that the hot and dry period in 2018 explains why the mean relative increase of NEE800 due to warming was not higher under reduced rather than natural herbivory in 2018 (Fig. 4b) as was the case in 2017 (Fig. 4a). In fact, this phenomenon becomes very clear when the effects of warming and reduced herbivory on CO2 fluxes in 2018 are portrayed separately for the period of typical humid conditions (i.e., when VPD was clearly lower than 2.5 kPa) and the period of hydrological stress (Fig. 4c, d). Under typical conditions (Fig. 4c), warming increased NEE800 more under reduced rather than normal herbivory, as in 2017, whereas during hydrological stress (Fig. 4d), warming barely elevated GPP800 and reduced NEE800 under reduced herbivory. Meanwhile, under natural herbivory, the effects of warming on GPP800 and NEE800 remained positive also during the heat wave (Fig. 4d). These results show that although insect herbivores seem to generally dampen the positive effect of warming on ecosystem CO2 uptake in our Subarctic ecosystem, they can simultaneously preserve CO2 uptake during heat waves due to their cumulative negative effects on plant biomass accumulation. Since plants at high latitudes are poorly adapted to dry conditions45,46, such unforeseen regulatory factors may be important during the extreme heat waves that are becoming more abundant under climate warming47.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that the generally minor background insect herbivore pressure in high latitude ecosystems can have a strikingly important role in plant resource acquisition and ecosystem–atmosphere CO2 exchange, both in the present and future warmer climates. It also appears that while warming has a clear positive influence on ecosystem CO2 uptake potential, through many simultaneous aboveground and belowground mechanisms, with less herbivory this effect would be greater. As the background insect herbivory is predicted to increase under climate warming16,25–30,32, these results imply that insects may significantly dampen the strengthening of CO2 sink at high latitudes. A final testimony to the significance of insect herbivores is their ability to influence the way plants and ecosystem CO2 exchange respond to extreme weather patterns, such as the intense heat wave we observed in our study. Altogether, these observations suggest that background insect herbivory should be raised among the key factors in the modeling and empirical research of the responses of high latitude ecosystems to climate warming.

Methods

Field site and treatment plots

The experiment was established in the mountain birch forest-tundra ecotone at the Turku University Kevo Subarctic Research Institute (69°45.4′N, 27°00.5′E; altitude 104 m a.s.l., mean annual temperature −1.3 °C, mean annual precipitation 354 mm in reference years 1981–2010; data from Finnish Meteorological Institute) in 2016. Adult mountain birches were trimmed in the experimental area, but field layer vegetation was left intact and twenty experimental plots (each 0.75 m × 1 m) with no mountain birch stumps were established. To include Subarctic woody species in the experiment and to have controlled and properly replicated plant material to accurately follow treatment responses in plants, plantlets of four birch species (local B. nana and B. pubescens subsp. czerepanovii and currently slightly more southern B. pendula and B. pubescens) were planted, 20 cm apart, amongst the field layer vegetation in each plot (12 plantlets in each plot, three genotypes per species).

Plant material and plot properties

Birch material was collected from natural Subarctic populations growing between 67°43′N and 69°01′N with mean annual temperatures varying from −1.2 to −1.9 °C (reference years 1981–2010; data from Finnish Meteorological Institute). The plantlets were cloned from the collected twig material using the micropropagation technique at the Haapastensyrjä Unit of the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) at the end of 2015, potted into nursery peat (Kekkilä OPM 420 W) in May 2016 and planted to the field site in mid-July 2016. Mean plantlet height was 6.2 cm (SD 4.5, range 1–29 cm) at the time of planting and 15.6 cm (SD 11.0, range 1.5–66 cm) at the end of the growing season 2018. Birches can produce thousands of seeds m−2 in Subarctic areas48 and our planting density of 16 plantlets m−2 is well within the natural variation of density in young birch seedling patches49. Birches were chosen as test species due to their high abundance in Subarctic Fennoscandia.

Variation in soil and vegetation properties among the experimental plots was recorded after planting birches. Two to three soil cores (diameter 3 cm, depth 10 cm, or to the nearest rock) were taken from each plot, the samples were pooled, dried (70 °C, 48 h), and the organic matter (OM) content was measured as a loss on ignition (550 °C, 4 h). Lichens and plants were identified to species or genus level and their areal cover was visually estimated for the area inside the flux chamber collar (55 cm × 55 cm). Estimates of soil OM (range 9–38% of soil dry mass among the plots) and the cover of vascular plants (29–83% of area covered; Empetrum nigrum, Vaccinium uliginosum, and Vaccinium vitis-idaea as common species; cover of planted birches was on average 7% of the cover of all vascular plants), mosses (3–85%, Pleurozium schreberi and Hylocomium splendens) and lichens (0–23%, Nephroma arcticum and Cladonia arbuscula) were later used as covariates in the statistical models to control the effects of soil and plant plot-to-plot variation on response variables.

Experimental design and treatments

Treatments included two levels of warming (ambient, +3 °C) and two levels of insect herbivory (natural, reduced) in a fully factorial 2 × 2 design. In the field, the 20 treatment plots were first divided into five replicate blocks and then in each block, the four treatment combinations were randomly allocated to the plots. The distance between adjacent plots was >1.2 m, which was sufficient to avoid thermal effects between warmed and control plots (ensured using a thermal camera Flir E8; Flir Systems AB, USA).

Warming was realized using two 240 mm × 60 mm ceramic heaters (Elstein-Werk M. Steinmetz GmbH & Co., Germany; dummy heaters in ambient plots), installed 80 cm above the ground and controlled using a microprocessor-based feedback system. The feedback system maintained a fixed temperature differential between the ambient and heated plots using real-time temperature data from Pt100 sensors (Gräff GmbH, Germany) attached to a RMD680 multichannel transmitter (Nokeval Oy, Finland). The sensors were installed 30 cm above the ground (i.e., on the top of the vegetation layer) within green metal plates, mimicking plant leaf surfaces, in five ambient and five heated plots. The ceramic heaters warm surfaces more than the air, so using the temperature of the green metal plates for controlling heating we ensured that vegetation was not overheated. Warming was turned on in spring when the snow-cover melted below 20 cm, and turned off in late autumn when mean daily air temperatures in ambient plots remained permanently below −3 °C. While warming was on, air temperatures were continuously recorded using Pt100 sensors installed under white plastic plates 30 cm above the ground in three control and three warmed plots. Soil temperature and moisture were regularly, but not continuously, measured in 3–5 spots in each plot at the depth of 5 cm using SM150T soil moisture kit (Delta-T Devices Ltd., UK) and Testo 735 thermometer (Testo SE & Co., Germany) attached to a Pt100 sensor. On average, the plates mimicking plant leaves were 3.3 °C, the air 2.3 °C and the soil 1.2 °C warmer in heated than ambient plots across the warming periods in 2016–2018 (in 2016, warming did not cover the entire growing season but was turned on in early July).

The herbivore treatment was started in the beginning of the 2017 growing season and was accomplished by spraying the herbivore reduction plots with 0.1% solution of synthetic pyrethrin (Decis EC25, Bayer Crop-Science, Germany) and the control plots with tap water weekly, using two portable garden sprayers and a protective tent to eliminate wind drift. Decis EC25 has not found to have side-effects on plant growth or chemistry50 and although deltamethrin, the active ingredient, contains N, the quantities of N that could enter soil during sprayings are negligible. In our experimental plots, the instantaneous top soil (0–10 cm) mineral N (sum of NH4+–N and NO3−–N) availability is, on average, 1.5 µg N per g dry soil (soil sampled in summer 2017). If all N in one spraying of a plot (69 µg N) entered the soil, the instantaneous mineral N availability in the soil would be increased by 0.1%. Similarly, the yearly maximum rate of N addition through sprayings is only 0.1% of the rate (1 g N m−2 yr−1) that was not found to affect B. glandulosa growth in a tundra experiment with comparable shrub vegetation36.

Warming and herbivore treatments were also carried out through the 2019 growing season, which allowed us to provide supplementary leaf damage data for 2019 (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Measuring and calculating CO2 fluxes and VPD

Aluminum collars (outside dimensions 60 cm × 60 cm) were assembled in each plot to enable CO2 exchange measurements using the closed chamber technique with transparent polycarbonate chambers (59 cm × 59 cm × 50 cm and 59 cm × 59 cm × 40 cm)51. As the collars were squares and the birch plantlets were planted 20 cm apart in three rows and four columns (following the shape of the plot), nine plantlets (3 × 3) were always included in the collars and three excluded (with the exception of one plot, where only six plantlets were included due to difficulties in the placement of the collar into the rocky soil surface). Each collar had grooves that were filled with moist quartz sand to provide an airtight seal between the collar and the chamber. The CO2 concentration and air temperature inside the chamber were recorded continuously during measurements. A Vaisala CARBOCAP GMP343 (Vaisala Oyj, Finland) and a Picarro G2401 (Picarro Inc., CA, USA) online gas analyzer were used for taking CO2 concentration measurements. The chamber closure time was 6 min for the GMP343 (used during 4 and 7 days in 2017 and 2018, respectively) and 2 min for the G2401 (1 day in 2017, 5 days in 2018). In all cases, the net CO2 exchange was measured under the prevailing light conditions and with a dark hood. To determine the radiation response of photosynthesis, one or two additional shading levels were generated using meshes with 30 and 70% transparency when possible (160 of the 340 cases). The air inside the chamber was mixed with a battery-driven fan.

The solar radiation levels were measured with a photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) sensor (PQS1, Kipp & Zonen) on top of the chamber. In the GMP343-based system, there was a lid, made of the chamber material, above the PAR sensor to emulate the conditions inside the chamber, while the sensor was uncovered in the G2401-based system. The influence of the chamber wall on the measured PAR was tested afterwards with a similar transparent chamber, which indicated that the difference between the measurements taken inside and outside the chamber was <2%. In addition, it is important to note that the measurements used in the present study were each day conducted with the same system for all the chamber collars, so no systematic error was introduced into the comparison of treatments.

The CO2 flux, i.e., the net ecosystem exchange (NEE), was calculated as

| 1 |

where p is atmospheric pressure, M is the molecular mass of CO2 (44.01 g mol−1), R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), T is the mean air temperature during chamber closure, V is the chamber volume, A is the chamber base area, and is the mean CO2 mixing ratio change in time calculated with linear regression (see Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). To allow for the stabilization of the CO2 flux after the chamber closure, the last 5 and 1.5 min of the data series recorded with the GMP343 and G2401, respectively, were included. A micrometeorological sign convention was used: a positive flux indicates a flux from the ecosystem to the atmosphere (emission), and a negative flux indicates a flux from the atmosphere into the ecosystem (uptake).

The measured NEE was partitioned into gross primary productivity (GPP) and ecosystem respiration (Re):

| 2 |

Re was obtained from the measurements with a darkened chamber. GPP was modeled by a rectangular hyperbola52:

| 3 |

where a is the initial slope between GPP and PAR, and GPmax is the theoretical maximum gross photosynthetic rate. The parameters α and GPmax were first estimated for those light response measurements that had at least three light levels available and at least one data point with PAR > 800 μmol m−2 s−1 (n = 68 with 20, 15, 16, and 17 measurements from control, warming, herbivory reduction, and warming × herbivory reduction treatment plots, respectively). Using these parameter values, GPmax/α ratios were calculated and the median value of 203 μmol m−2 s−1 was chosen to be used as a common GPmax/α ratio. This fixed value was employed in all GPP calculations, while α (or, equally, GPmax) was available as a free parameter. The reason for introducing a common GPmax/α was to obtain consistent data also for those days when irradiance was limited and the saturation level of photosynthesis was not attained. Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences in GPmax/α among the treatment combinations (P = 0.094 for the Mood’s median test). Using the common GPmax/α, the α parameter was fitted separately for each light response measurement (i.e., for each chamber collar in each day, n = 340), and NEE800 and GPP800, i.e., NEE and GPP at PAR = 800 μmol m−2 s−1, were calculated. NEE800 and GPP800 represent the CO2 exchange in conditions typical of the daily maximum PAR and serve as standardized metrics that allow comparison of the ecosystem carbon sink potential among different days and treatments. The different steps of the fitting procedure described above are validated in Supplementary Figs. 3–6. We also standardized NEE at a lower (300 μmol m−2 s−1) and higher (1200 μmol m−2 s−1) PAR level, but there were no marked differences in the outcome of the statistical analysis (Supplementary Table 8).

The water vapor pressure deficit, VPD (kPa), was calculated as

| 4 |

where T is air temperature in °C and RH is relative humidity in %.

Soil N and microbial biomass C

Plant availability of mineral N (NH4+ and NO3−) was estimated in the soil organic layer (at 3 cm depth) using ion-exchange resin bags (UNIBEST Ag Manager™). Three resin bags were placed in each plot in July 2016 and in the following autumns one (2017) or two (2018) bags were transferred from each plot to the laboratory for N extraction in 50 ml of 2 M KCl. The KCl solution was filtered through a glass microfiber filter (Whatman, Germany) and NH4+ and NO3− concentrations were analyzed using a Lachat QuikChem 8000 analyser (Zellweger Analytics, Lachat Instruments Division, USA).

Microbial biomass samples were collected with an auger (diameter 2.5 cm) from three (or more if the soil was shallow) spots within each plot in August 2018. Three layers (organic layer, 0–5 cm layer of mineral soil, >5 cm layer of mineral soil) were separated from each soil core. Within each plot, the samples collected from the same layer were pooled and sieved through a 2-mm (mineral soil) or 6-mm mesh (organic soil) before analyzing microbial biomass carbon (MBC) using the chloroform-fumigation extraction method53. In 2018, we further tested whether the insecticide sprayings could have direct effects on soil microbes. Soil from 10 random spots outside the experimental area was collected in early spring, homogenized (largest roots and rocks removed), and placed into ten 1.5-L pots. The pots were buried in the ground and covered with a 1–2 cm layer of dead, oven-dried (70 °C for 20 h, 100 °C for 4 h) Sphagnum moss to mimick the insulating moss layer in the experimental plots (where the mean moss depth was 1.2 cm). Along with the sprayings in the experimental plots, five of the pots were then sprayed with water and five with the insecticide. Soil was collected from the pots along with the microbial biomass C sampling and analyzed accordingly. No difference (t8 = 0.389 and P = 0.708) between the mean MBC in soils sprayed with water (546.3 ± 85.0 mg MBC kg−1 soil; mean ± SE) and insecticide (494.3 ± 103.4) was found (source data are provided as a Source Data file).

Phenology and growth of Betula plantlets

For estimating treatment effects on plant spring phenology, all birch plantlets were surveyed daily in spring 2017 and 2018. The date of the first bud of a plantlet opening was considered as the start of the growing season for that plantlet. A bud was considered open once the protective bud scales were completely separated and the emerging leaf was visible54. During the peak growing season, plant performance was estimated two (2017) to three (2018) times by measuring the chlorophyll content of five full-grown topmost leaves in several branches in each plantlet, using the CCM300 non-destructive optical chlorophyll content meter (Opti-Sciences, USA). The autumn phenology was in turn estimated through chlorophyll breakdown: the chlorophyll content of the five topmost leaves of each plantlet was measured approximately every 3 days using the CCM300 until most of the plantlets had shed their leaves.

To assess plantlet shoot growth, their height was measured at planting and thereafter each autumn following growth cessation. The relative growth was then calculated as a height increment relative to the initial height.

Leaf herbivore damage of Betula plantlets

To estimate treatment effects on herbivore load, all leaves in each birch plantlet were surveyed for herbivore damage in the middle of August 2017. Leaf damage was illustrated using a Schreiner-type method20,21,55 in which a damage index, ranging from 0 to 100, is produced for each plant individual by multiplying two scores, A and B. The score A is the plantlet mean of values (ranging from 0 to 25) that illustrate the size of the damaged area in a single leave: 0 = no damage, 1 = small damaged area (1–4% of leaf area damaged), 5 = medium damaged area (5–20%) and 25 = large damaged area (>20%). The score B (ranging from 0 to 4) tells the percentage of leaves of a plantlet that are damaged: 0 = 0%, 1 = 1–25%, 2 = 26–50%, 3 = 51–75%, and 4 = 76–100%. As no data was obtained for 2018, we repeated the leaf damage survey in August 2019 to ensure that results from 2017 can be generalized across years.

Statistical analysis

Treatment effects on response variables were tested using mixed models and Type I ANOVA (IBM SPSS Statistics 21), where the variance is allocated to explanatory variables in order of their appearance (in tables of statistics, order of explanatory variables follows their order in respective models). Soil OM content and the areal cover of vascular plants, lichens, and mosses were treated as covariates and included in the models first to remove plot-to-plot variation that might otherwise contribute to treatment effects. Warming and herbivory treatments were treated as fixed effects and field block as a random effect. For birch variables, species was included as a fixed effect and genotype, nested within species, as a random effect. Date, year, and soil layer (MBC was measured for three adjacent soil layers) were treated as repeated measurements and compound symmetry was used as a repeated covariance structure. Those response variables that were measured multiple times during a growing season were tested separately for 2 years. ANOVA assumptions were checked from the residuals and transformations were used where necessary (reported in table and figure legends).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Academy of Finland (Grants 285030 and 296888) and Kone Foundation (a personal grant to T.S.). The authors thank T. Ryynänen for designing and assembling the heating apparatus, J. Unga and K. Ranta for collecting birch material, T. Lehtosalo, N. Fontaine, T. Dubo, and M. Fontaneu for assisting in data collection, M. Lehtonen for analyzing N, S. Robinson for commenting and editing language, L. Mehtätalo (University of Eastern Finland statistical consulting services) for advising in statistics, and the Kevo staff, especially O. Suominen, I. Syvänperä, and E. Vainio, for providing excellent facilities and assistance throughout the years.

Source data

Author contributions

T.S. and J.M. designed and established the field experiment and coordinated the day-to-day measurements. M.R. helped with site selection and production of birch plantlets together with E.O. CO2 flux measurements were designed by T.S., M.A., and J.M. L.H. and K.M. carried out the measurements and L.H., M.A., and J.-P.T. analyzed the flux data. K.M. carried out phenology surveys, vegetation analysis, and soil moisture and temperature measurements. K.K. and N.M. analyzed microbial biomass. T.S. merged the data, produced tables and figures, and wrote the paper with contribution from all co-authors.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data for Figs. 1–3, Supplementary Figs. 1–6, and Supplementary Tables 2 and 8 are provided as a Source Data file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Isabel C. Barrio, Richard Lindroth, and Daniel Metcalfe for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-16404-4.

References

- 1.Piao S, Friedlingstein P, Ciais P, Viovy N, Demarty J. Growing season extension and its impact on terrestrial carbon cycle in the Northern Hemisphere over the past 2 decades. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2007;21:GB3018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buitenwerf R, Rose L, Higgins SI. Three decades of multi-dimensional change in global leaf phenology. Nat. Clim. Change. 2015;5:364–368. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rustad LE, et al. A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia. 2001;126:543–562. doi: 10.1007/s004420000544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hobbie SE, Nadelhoffer KJ, Hogberg P. A synthesis: the role of nutrients as constraints on carbon balances in boreal and Arctic regions. Plant Soil. 2002;242:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson EA, Janssens IA. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature. 2006;440:165–173. doi: 10.1038/nature04514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leffler AJ, et al. Cloud cover and delayed herbivory relative to timing of spring onset interact to dampen climate change impacts on net ecosystem exchange in a coastal Alaskan wetland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019;14:084030. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leffler AJ, et al. Delayed herbivory by migratory geese increases summer-long CO2 uptake in coastal western Alaska. Glob. Change Biol. 2019;25:277–289. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sjögersten S, van der Wal R, Woodin SJ. Habitat type determines herbivory controls over CO2 fluxes in a warmer Arctic. Ecology. 2008;89:2103–2116. doi: 10.1890/07-1601.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjögersten S, van der Wal R, Loonen MJJE, Woodin SJ. Recovery of ecosystem carbon fluxes and storage from herbivory. Biogeochemistry. 2011;106:357–370. doi: 10.1007/s10533-010-9516-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cahoon SMP, Sullivan PF, Post E, Welker JM. Large herbivores limit CO2 uptake and suppress carbon cycle responses to warming in West Greenland. Glob. Change Biol. 2012;18:469–479. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metcalfe DB, Olofsson J. Distinct impacts of different mammalian herbivore assemblages on Arctic tundra CO2 exchange during the peak of the growing season. Oikos. 2015;124:1632–1638. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keenan TF, Riley WJ. Greening of the land surface in the world’s cold regions consistent with recent warming. Nat. Clim. Change. 2018;8:825–828. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0258-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Box JE, et al. Key indicators of Arctic climate change: 1971–2017. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019;14:045010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belshe EF, Schuur EAG, Bolker BM. Tundra ecosystems observed to be CO2 sources due to differential amplification of the carbon cycle. Ecol. Lett. 2013;16:1307–1315. doi: 10.1111/ele.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopez-Blanco E, et al. Exchange of CO2 in Arctic tundra: impacts of meteorological variations and biological disturbance. Biogeosciences. 2017;14:4467–4483. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozlov MV, Lanta V, Zverev V, Zvereva EL. Global patterns in background losses of woody plant foliage to insects. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2015;24:1126–1135. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turcotte MM, et al. Percentage leaf herbivory across vascular plant species. Ecology. 2014;95:788–788. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cyr H, Pace ML. Magnitude and patterns of herbivory in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Nature. 1993;362:148–150. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metcalfe DB, Crutsinger GM, Kumordzi BB, Wardle DA. Nutrient fluxes from insect herbivory increase during ecosystem retrogression in boreal forest. Ecology. 2016;97:124–132. doi: 10.1890/15-0302.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silfver T, Paaso U, Rasehorn M, Rousi M, Mikola J. Genotype × herbivore effect on leaf litter decomposition in Betula pendula saplings: ecological and evolutionary consequences and the role of secondary metabolites. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0116806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prittinen K, Pusenius J, Koivunoro K, Roininen H. Genotypic variation in growth and resistance to insect herbivory in silver birch (Betula pendula) seedlings. Oecologia. 2003;137:572–577. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zvereva EL, Zverev V, Kozlov MV. Little strokes fell great oaks: minor but chronic herbivory substantially reduces birch growth. Oikos. 2012;121:2036–2043. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozlov, M. V. & Zvereva, E. L. in Progress in Botany Vol. 79 (eds Cánovas, F. M. et al.) 313–355 (Springer, Cham, 2017).

- 24.Lempa K, et al. Rapid herbivore-induced changes in mountain birch phenolics and nutritive compounds and their effects on performance of the major defoliator, Epirrita autumnata. J. Chem. Ecol. 2004;30:303–321. doi: 10.1023/b:joec.0000017979.94420.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Currano ED, Labandeira CC, Wilf P. Fossil insect folivory tracks paleotemperature for six million years. Ecol. Monogr. 2010;80:547–567. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozlov M. Losses of birch foliage due to insect herbivory along geographical gradients in Europe: a climate-driven pattern? Clim. Change. 2008;87:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozlov MV, et al. Sap-feeding insects on forest trees along latitudinal gradients in northern Europe: a climate-driven patterns. Glob. Change Biol. 2015;21:106–116. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozlov MV, van Nieukerken EJ, Zverev V, Zvereva EL. Abundance and diversity of birch-feeding leafminers along latitudinal gradients in northern. Eur. Ecogr. 2013;36:1138–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrio IC, et al. Background invertebrate herbivory on dwarf birch (Betula glandulosa–nana complex) increases with temperature and precipitation across the tundra biome. Polar Biol. 2017;40:2265–2278. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garibaldi LA, Kitzberger T, Chaneton EJ. Environmental and genetic control of insect abundance and herbivory along a forest elevational gradient. Oecologia. 2011;167:117–129. doi: 10.1007/s00442-011-1978-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruosteenoja K, Jylhä K, Kämäräinen M. Climate projections for Finland under the RCP forcing scenarios. Geophysica. 2016;51:17–50. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf A, Kozlov M, Callaghan T. Impact of non-outbreak insect damage on vegetation in northern Europe will be greater than expected during a changing climate. Clim. Change. 2008;87:91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moise ERD, Henry HAL. Like moths to a street lamp: exaggerated animal densities in plot-level global change field experiments. Oikos. 2010;119:791–795. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koch O, Tscherko D, Kandeler E. Temperature sensitivity of microbial respiration, nitrogen mineralization, and potential soil enzyme activities in organic alpine soils. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2007;21:GB4017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin H, et al. Enhanced root exudation stimulates soil nitrogen transformations in a subalpine coniferous forest under experimental warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2013;19:2158–2167. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zamin TJ, Grogan P. Birch shrub growth in the low Arctic: the relative importance of experimental warming, enhanced nutrient availability, snow depth and caribou exclusion. Environ. Res. Lett. 2012;7:034027. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zangerl AR, et al. Impact of folivory on photosynthesis is greater than the sum of its holes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:1088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022647099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nabity PD, Zavala JA, DeLucia EH. Indirect suppression of photosynthesis on individual leaves by arthropod herbivory. Ann. Bot. 2009;103:655–663. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nabity PD, Hillstrom ML, Lindroth RL, DeLucia EH. Elevated CO2 interacts with herbivory to alter chlorophyll fluorescence and leaf temperature in Betula papyrifera and Populus tremuloides. Oecologia. 2012;169:905–913. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nykänen H, Koricheva J. Damage-induced changes in woody plants and their effects on insect herbivore performance: a meta-analysis. Oikos. 2004;104:247–268. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatcher PE. Three-way interactions between plant pathogenic fungi, herbivorous insects and their host plants. Biol. Rev. 1995;70:639–694. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biere A, Bennett AE. Three-way interactions between plants, microbes and insects. Funct. Ecol. 2013;27:567–573. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Novick KA, et al. The increasing importance of atmospheric demand for ecosystem water and carbon fluxes. Nat. Clim. Change. 2016;6:1023–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reich PB, et al. Effects of climate warming on photosynthesis in boreal tree species depend on soil moisture. Nature. 2018;562:263–267. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0582-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gamm CM, et al. Declining growth of deciduous shrubs in the warming climate of continental western Greenland. J. Ecol. 2018;106:640–654. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tenkanen A, et al. Differences in growth and gas exchange between southern and northern provenances of silver birch (Betula pendula) in northern Europe. Tree Physiol. 2019;40:198–214. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpz124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tingley MP, Huybers P. Recent temperature extremes at high northern latitudes unprecedented in the past 600 years. Nature. 2013;496:201–205. doi: 10.1038/nature11969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rousi M, Possen BJMH, Pulkkinen P, Mikola J. Using long-term data to reveal the geographical variation in timing and quantity of pollen and seed production in silver and pubescent birch in Finland: implications for gene flow, hybridization and responses to climate warming. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019;438:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kinnaird JW. Effect of site conditions on the regeneration of birch (Betula pendula Roth and B. pubescens Ehrh.) J. Ecol. 1974;62:467–472. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silfver T, Autelo M, Paaso U, Koikkalainen K, Mikola J. Use of an insecticide in field-scale plant–herbivore studies: no side effects of synthetic pyrethrin on Betula pendula growth or chemistry. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 2013;50:337–346. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alm J, et al. Carbon balance of a boreal bog during a year with an exceptionally dry summer. Ecology. 1999;80:161–174. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whiting GJ. CO2 exchange in the Hudson Bay lowlands: community characteristics and multispectral reflectance properties. J. Geophys. Res. 1994;99:1519–1528. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vance ED, Jenkinson DS, Brookes PC. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987;19:703–707. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rousi M, Pusenius J. Variations in phenology and growth of European white birch (Betula pendula) clones. Tree Physiol. 2005;25:201–210. doi: 10.1093/treephys/25.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fritz RS, Roche BM, Brunsfeld SJ. Genetic variation in resistance of hybrid willows to herbivores. Oikos. 1998;83:117–128. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data for Figs. 1–3, Supplementary Figs. 1–6, and Supplementary Tables 2 and 8 are provided as a Source Data file.