This meta-analysis assesses the psychopathological outcomes in healthy volunteers and patients with schizophrenia treated with ketamine and the experimental factors associated with these findings.

Key Points

Question

What psychopathological outcomes are associated with ketamine hydrochloride in healthy volunteers and patients with schizophrenia, and what factors are associated with these outcomes?

Findings

This meta-analysis of 36 studies, including 725 unique healthy participants, found that the acute administration of ketamine relative to placebo was associated with a meaningful increase in positive and negative symptoms of psychosis in healthy volunteers and patients with schizophrenia. This association was greater for positive compared with negative symptoms and when a bolus was given with the infusion relative to an infusion alone.

Meaning

These findings suggest that ketamine is associated with psychosis-like symptoms in healthy volunteers and that the bolus administration of ketamine should be avoided when it is used in therapeutic contexts.

Abstract

Importance

Ketamine hydrochloride is increasingly used to treat depression and other psychiatric disorders but can induce schizophrenia-like or psychotomimetic symptoms. Despite this risk, the consistency and magnitude of symptoms induced by ketamine or what factors are associated with these symptoms remain unknown.

Objective

To conduct a meta-analysis of the psychopathological outcomes associated with ketamine in healthy volunteers and patients with schizophrenia and the experimental factors associated with these outcomes.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, Embase, and PsychINFO databases were searched for within-participant, placebo-controlled studies reporting symptoms using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) in response to an acute ketamine challenge in healthy participants or patients with schizophrenia.

Study Selection

Of 8464 citations retrieved, 36 studies involving healthy participants were included. Inclusion criteria were studies (1) including healthy participants; (2) reporting symptoms occurring in response to acute administration of subanesthetic doses of ketamine (racemic ketamine, s-ketamine, r-ketamine) intravenously; (3) containing a placebo condition with a within-subject, crossover design; (4) measuring total positive or negative symptoms using BPRS or PANSS; and (5) providing data allowing the estimation of the mean difference and deviation between the ketamine and placebo condition.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two independent investigators extracted study-level data for a random-effects meta-analysis. Total, positive, and negative BPRS and PANSS scores were extracted. Subgroup analyses were conducted examining the effects of blinding status, ketamine preparation, infusion method, and time between ketamine and placebo conditions. The Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were used as effect sizes for individual studies. Standardized mean differences between ketamine and placebo conditions were calculated for total, positive, and negative BPRS and PANSS scores.

Results

The overall sample included 725 healthy volunteers (mean [SD] age, 28.3 [3.6] years; 533 [73.6%] male) exposed to the ketamine and placebo conditions. Racemic ketamine or S-ketamine was associated with a statistically significant increase in transient psychopathology in healthy participants for total (SMD = 1.50 [95% CI, 1.23-1.77]; P < .001), positive (SMD = 1.55 [95% CI, 1.29-1.81]; P < .001), and negative (SMD = 1.16 [95% CI, 0.96-1.35]; P < .001) symptom ratings relative to the placebo condition. The effect size for this association was significantly greater for positive than negative symptoms of psychosis (estimate, 0.36 [95% CI, 0.12-0.61]; P = .004). There was significant inconsistency in outcomes between studies (I2 range, 77%-83%). Bolus followed by constant infusion increased ketamine’s association with positive symptoms relative to infusion alone (effect size, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.36-1.90] vs 0.84 [95% CI, 0.35-1.33]; P = .006). Single-day study design increased ketamine’s ability to generate total symptoms (effect size, 2.29 [95% CI, 1.69-2.89] vs 1.39 [95% CI, 1.12-1.66]; P = .007), but age and sex did not moderate outcomes. Insufficient studies were available for meta-analysis of studies in schizophrenia. Of these studies, 2 found a statistically significant increase in symptoms with ketamine administration in total and positive symptoms. Only 1 study found an increase in negative symptom severity with ketamine.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that acute ketamine administration was associated with schizophrenia-like or psychotomimetic symptoms with large effect sizes, but there was a greater increase in positive than negative symptoms and when a bolus was used. These findings suggest that bolus doses should be avoided in the therapeutic use of ketamine to minimize the risk of inducing transient positive (psychotic) symptoms.

Introduction

Ketamine hydrochloride was first synthesized in 1962.1 It is a phencyclidine derivative that acts on the glutamate system by antagonizing N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors.1 Ketamine has been used to model the symptoms of schizophrenia and is used in the treatment of severe depression and pain management2 as well as being used recreationally. Misuse can be hazardous, leading to drug addiction.

In the 1960s, NMDA antagonists, such as ketamine, were identified as inducing clinical symptoms similar to those seen in schizophrenia, more so than other psychotomimetics used in past drug models of psychosis.3,4 In particular, in addition to inducing positive symptoms, such as perceptual changes and delusions, ketamine induces negative symptoms, such as blunted affect and emotional withdrawal.5 Many studies have been conducted to investigate its effect on healthy people, but the methods vary greatly, and the observed behavioral responses differ.

Despite the recognition that ketamine can induce transient schizophrenia-like symptoms,5 the consistency and magnitude of its effect on positive and negative symptoms remains unclear. Moreover, it is unclear how blinding status, ketamine preparation, infusion method, and time between the ketamine and placebo conditions are associated with the generation of symptoms.

The development of ketamine and its derivatives as antidepressants6,7 means that determining the extent to which ketamine induces schizophrenia-like or psychotomimetic symptoms and what factors are associated with this outcome is particularly timely in order to understand and minimize the risks of adverse events associated with the therapeutic use of ketamine. We also aimed to evaluate outcomes in patients with schizophrenia to determine whether they are more sensitive to ketamine.

We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association of ketamine with positive, negative, and total psychopathological outcomes in healthy volunteers and patients with schizophrenia. Many studies use ketamine to inform understanding of the mechanisms underlying schizophrenia. This specific use of ketamine is the main focus of our review, but we also use the findings to inform understanding of other uses of ketamine.

Methods

Selection Procedures

A meta-analysis was performed according to the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE)8 and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)9 frameworks. Three authors (K.B., G.H., and F.B.) independently searched MEDLINE (from 1946 to February 3, 2020), Embase (from 1974 to February 3, 2020), and PsychINFO (from 1806 to January 27, 2020). The following keywords were used: (Ketamine) and (psycho* NOT psychotherapy or schiz* or BPRS or brief psychiatric rating scale or PANSS or positive and negative syndrome scale or positive symp* or negative symp*). Meta-analyses and systematic and narrative review articles were hand-searched for additional reports. Abstracts were screened, and the full texts of suitable studies were obtained. If full texts were not available, authors were contacted and full content was requested. Authors were also contacted when Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) or Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) subscales (total, negative, or positive) were missing or if the individual items included in the positive or negative scales were not reported. Three authors (K.B., G.H., and F.B.) selected the final studies included in the meta-analysis based on the following criteria.

Selection Criteria for the Meta-analysis of Ketamine’s Effects in Healthy Volunteers

Inclusion criteria were studies (1) including healthy participants, (2) reporting symptoms occurring in response to acute administration of subanesthetic doses of ketamine (racemic ketamine, s-ketamine, or r-ketamine) intravenously, (3) containing a placebo condition with a within-participant, crossover design, (4) measuring total positive or negative symptoms using the BPRS or PANSS, and (5) providing data allowing the estimation of the mean difference and deviation between the ketamine and placebo condition. We used the PANSS and BPRS scales as the measures of symptom severity because they are well validated, standardized assessments of psychopathology used in both healthy participants and patients with schizophrenia.10,11 They assess the same symptom dimensions and are commonly combined in meta-analyses.12 We included all versions of the total BPRS because often the version was not specified. All versions measure the same rating items, but some include more items than others. However, all included studies are within-person studies, and so this should not affect the analysis. Exclusion criteria consisted of 1 or more of the following factors: (1) no placebo condition, (2) no report of any total, negative, or positive scores (see the following sections for more details), (3) absence of measures in either the ketamine or the placebo condition, (4) no report of original data, (5) no data provided that enabled the standardized mean differences (SMDs) to be calculated (such as the SD or the standard error of the mean), (6) no more than 2 participants in each group, and/or (7) concurrent administration of other pharmacological compounds in addition to ketamine.

Selection Criteria for the Meta-analysis of Ketamine’s Effects in Schizophrenia

The selection criteria for studies investigating the effect of ketamine in patients with schizophrenia were the same as the criteria for healthy volunteers. The only additional criterion was for participants to have a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Additional Symptom Subdomain Inclusion Criteria for Both Meta-analyses

Studies used different combinations of symptom items in their positive and negative BPRS scores. We included studies in the negative analysis if their BPRS scale included all 3 negative symptom items: blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and motor retardation. We included studies in the positive analysis if they included more than 3 positive symptom items: conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness. These symptom items correlate most strongly and reliably with validated scales of positive and negative symptoms13: the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms14 and Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms,15 respectively. If the symptom items included in the scale were not documented, we requested the information from authors (eMethods 1 in the Supplement).

Recorded Variables

The primary outcome measures were the effect sizes for total, positive, and negative BPRS and PANSS scores in healthy participants or in patients with schizophrenia for ketamine compared with placebo conditions. Data were extracted from every study for author, year of publication, number of participants, participant age, sex, diagnosis, study design, details of the placebo condition, past or present psychiatric diagnoses among healthy volunteers, recent substance misuse or dependence history, family history of psychosis, major medical or neurological disorder, prior exposure to ketamine, concurrent psychotropic medication use, ketamine preparation, dose and timing of ketamine administration relative to the symptom measures, and mean (SD) measure of symptoms in the ketamine and placebo conditions. Plot digitizer software was used to examine reliability for the data from studies in which data were only available in a plot format.

The highest available ketamine dose was selected if multiple doses were reported. All data sets included in the meta-analysis were independent, and there was no overlap in the participants included in the meta-analyses. The raw data are provided in eTables 1 to 4 in the Supplement.

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa tool for assessing risk in nonrandomized studies and the Cochrane assessment of risk of bias tool.16,17 Scores were calculated by 2 investigators (K.B., G.H.). Studies with scores of at least 7 were considered to have a low risk of bias (eMethods 2-4 in the Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the metafor package, version 1.9-9, with R software, version 3.3.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Random-effects models based on restricted maximum likelihood estimation were used in all analyses. Random-effects models were deemed preferable for this analysis owing to substantial between-study differences in study design. Effect sizes or SMDs for individual studies were estimated by calculating the standardized mean change scores. Mean differences in symptom measurements between the ketamine and placebo conditions were used to calculate the standardized mean change score. The 95% CI of the effect size was also calculated.

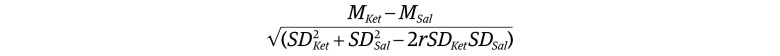

The SMD was defined for each study as follows18:

|

where MKet and MSal are the mean scores and SDKet and SDSal are the SDs for the ketamine and saline (placebo) conditions, respectively, with r denoting the between-condition correlation for symptom scores under saline and ketamine conditions. The correlation coefficient was set to 0.5 for all studies in our main analysis based on evidence from studies in schizophrenia.19,20 However, a sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the influence of this assumption on our main results by refitting our model using r values ranging from 0.1 and 0.7 (eMethods 5 and 6 in the Supplement).

To determine whether ketamine had a greater association with positive or negative symptoms, a multivariate meta-analytic approach was adopted using an unstructured variance-covariance matrix. Because within-study correlations between positive and negative symptom scores are not reported, we estimated the correlation coefficient to be 0.5 based on prior studies.20 To investigate the influence of this value on the findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses using correlation coefficients of 0.1 and 0.7 (eMethods 7 and 8 in the Supplement).21

Inconsistency or heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the Cochran Q statistic22 and I2 statistic.23 An I2 statistic of less than 25% was taken to indicate low inconsistency; 25% to 75%, medium inconsistency; and greater than 75%, high inconsistency. The I2 statistics were calculated for each subgroup analysis. Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses were also conducted.

Publication bias and selective reporting were assessed using the Egger regression test of the intercept24 and were represented diagrammatically with funnel plots as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (eFigures 1-3 in the Supplement). Trim-and-fill analyses were also conducted.

Secondary subgroup and meta-regression analyses were performed to examine the effects of study design. Specifically, we compared effect size in double-blind vs single-blind or unblinded studies; s-ketamine vs racemic ketamine; bolus followed by constant infusion administration vs infusion alone; and single-day (ketamine and placebo were given on the same day) vs multiple-day (ketamine and placebo given on different days) studies. In addition, we compared the effect size from studies using the BPRS with those using the PANSS to determine whether the method of measuring symptoms was associated with the magnitude of the effect. The statistical significance of subgroup differences was determined by fitting separate random-effects models for each subgroup and then comparing subgroup summary estimates in a fixed-effects model with a Wald-type test. A significance level of P < .05 (2 tailed) was adopted (see eMethods 9 and 10 in the Supplement for further details).

Results

Retrieved Studies for the Meta-analysis of Healthy Volunteers

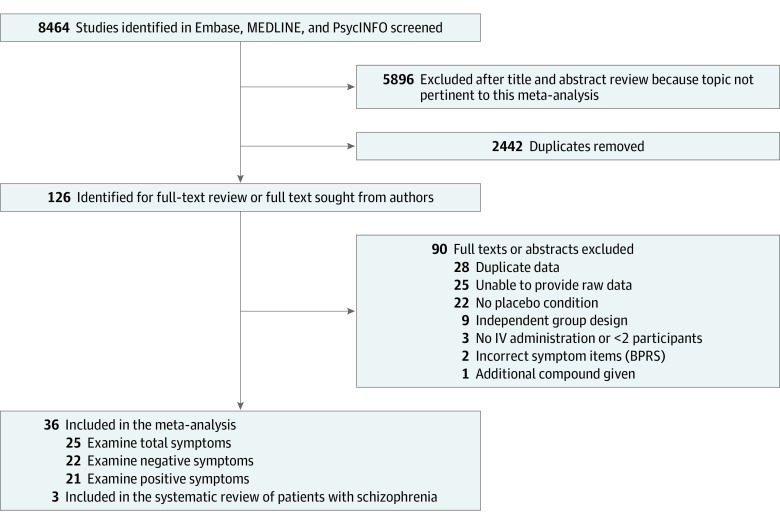

A total of 36 studies involving 725 unique participants (mean [SD] age, 28.3 [3.6] years; 533 male [73.6%] and 192 female [26.5%]) were included in the meta-analysis.3,25,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61 Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart. The included studies are summarized in the Table, with further details in eTable 5 in the Supplement. Ketamine was administered intravenously in all studies. The search identified 2 additional studies using inhaled administration, but these did not have data available.62,63

Figure 1. Search Process Summarizing the Review and Exclusion of Studies.

BPRS indicates Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; IV, intravenous.

Table. Summary of Sample and Study Characteristics of Included Studies Involving Healthy Volunteers and Patients With Schizophreniaa.

| Source | Sample size, No. | Age, mean (SD), y | Sex, No. male:female | Blinded | Randomized | Placebo condition | Symptom subscales reported | Length of ketamine infusion before symptom assessment, min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPRS Studies | ||||||||

| Kraguljac et al,30 2017 | 15 | 24.8 (3.49) | 10:5 | No | No | Saline | Total, positive (2), and negative | NR |

| Kort et al,43 2017 | 31 | 27.0 (4.3) | 19:12 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | NR |

| Duncan et al,36 2001 | 16 | 33.3 (3.1) | 16:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total and negative | 50 |

| Parwani et al,37 2005 | 13 | 31.9 (9.6) | 5:8 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | 15 |

| Rowland et al,38 2005 | 10 | 24.7 (3.4) | 10:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | 45 |

| Abel et al,42 2003 | 8 | 28.75 | 8:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | 15 |

| Anand et al,44 2000 | 16 | 34.0 (12.0) | 8:8 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive (1) and negative | 5 |

| Krystal et al,35 1998 | 23 | 30.0 | 19:11 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive (1) and negative | 60 for both subscales |

| Breier et al,39 1997 | 17 | 30.4 (6.8) | 15:2 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive (1) | NR |

| van Berckel et al,40 1998 | 18 | 23.7 (2.4) | 18:0 | Double | Yes | NR | Total | 40 |

| Malhotra et al,25 1997 | 16 | 27.8 (1.9) | 12:4 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total and negative | 55 |

| Krystal et al,45 1999 | 20 | 28 | 10:10 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive (1) and negative | 60 for both subscales |

| Krystal et al,46 2003 | 26 | 29.1 (9) | 19:7 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive (1) and negative | 80 |

| Micallef et al,47 2002 | 8 | 27.0 | 4:4 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive (1) and negative | NR |

| Rowland et al,52 2010 | 9 | 30.8 | 4:5 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | NR |

| Newcomer et al,31 1999 | 15 | 21.7 (3.2) | 15:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total and positive (1) | 30 |

| Stone et al,53 2011 | 8 | 28 (5.9) | 8:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | NR |

| Boeijinga et al,48 2007 | 12 | 39.6 (4.8) | 12:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | 30 |

| Abdallah et al,54 2018 | 14 | NR | NR | Single | No | Saline | Total and negative | 120 |

| Passie et al,55 2003 | 12 | 26.8 (3.31) | 12:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | NR |

| Horacek et al,56 2010 | 20 | 29.9 (5.69) | 13:7 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | NR |

| Morgan et al,57 2011 | 16 | 22.4 | 10:8 | Double | No | Saline | Total | NR |

| PANSS Studies | ||||||||

| Thiebes et al,29 2017 | 24 | 25 (2.64) | 24:0 | Single | Yes | Saline | Total, positive, negative, and factor scores | NR |

| Powers et al,58 2015 | 19 | 27.5 | 10:10 | No | No | Saline | Positive and negative | NR |

| Höflich et al,49 2015 | 30 | 25 (4.58) | NR | Double | Yes | Saline | Total, positive, and negative | NR |

| Nagels et al,59 2011 | 15 | 27 (3.6) | 15:0 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total, positive, and negative | NR |

| Driesen et al,60 2013 | 22 | 29.14 (7.07) | 14:8 | No | No | Saline | Positive and negative | 45 |

| Vernaleken et al,50 2013 | 10 | 24.4 (3.9) | 10:0 | Single | Yes | Saline | Total, positive, and negative | NR |

| Krystal et al,3 2005 | 27 | 30.96 | 16:11 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive, negative, and factor score | 60 for both subscales |

| Krystal et al,32 2006 | 31 | 28.1 (7.6) | NR | Double | Yes | Saline | Total, positive, negative, and factor score | NR |

| Kleinloog et al,28 2015 | 30 | NR | 15:15 | Double | Yes | Saline | Positive and negative | NR |

| D’Souza et al,51 2012 | 32 | 27 (8.42) | NR | Double | Yes | Saline | Total, positive, and negative | NR |

| Grent-‘t-Jong et al,33 2018 | 14 | 29 (0.9) | 12:2 | Single | Yes | Saline | Total, negative, and positive | NR |

| D’Souza et al,34 2018 | 26 | 29.8 (9.56) | 21:5 | NR | No | Saline | Negative and positive | NR |

| Mathalon et al,61 2014 | 9 | 29.8 (7.9) | 5:4 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | 1 |

| Dickerson et al,41 2010 | 93 | 24.29 (2.62) | 47:46 | Single | Yes | Saline | Total, positive, negative, and factor score | 45 |

| Schizophrenia (BPRS) | ||||||||

| Lahti et al,26 2001 | 17 | 31.6 (7.8) | 11:6 | Double | Yes | NR | Total, positive (2), and negative | 20 |

| Malhotra et al,25 1997 | 13 | 31.3 (2.8) | 10:3 | Double | Yes | Saline | Total | 55 |

| Malhotra et al,27 1998 | 18 | 34.7 (2.3) | 13:5 | Double | Yes | NR | Positive (1) and negative | 35 |

Abbreviations: BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; NR, not reported; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

The BPRS measure includes the following positive symptoms (1): conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior, and unusual thought content; positive symptoms (2): conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, and unusual thought content; and negative symptoms: blunted affect, emotional withdrawal, and motor retardation. Further details including doses administered are reported in eTables 5 and 6 in the Supplement.

Total Psychopathological Symptoms

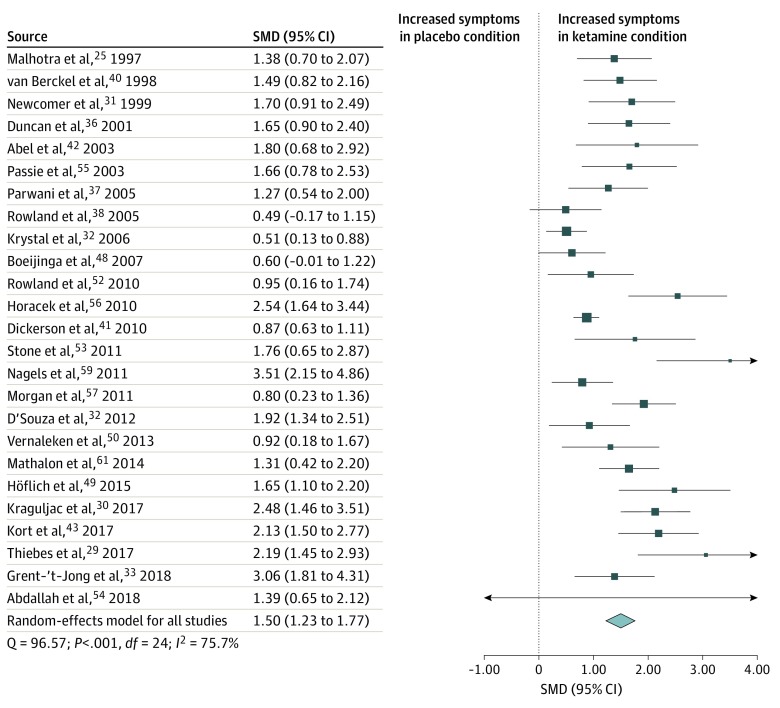

Total symptom scores were analyzed using data from 25 studies25,29,30,31,32,33,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,59,61 including 491 healthy participants exposed to the ketamine and placebo conditions. Total symptom scores were increased in the ketamine condition compared with the placebo condition (SMD = 1.50 [95% CI, 1.23-1.77]; P < .001) (Figure 2). The finding remained statistically significant in all iterations of the leave-one-out analysis (SMD range, 1.44-1.55; P < .001).

Figure 2. Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) in Total Symptoms Scores for Healthy Volunteers After Ketamine vs Placebo Administration.

Scores include Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. A statistically significant increase in total symptoms occurred in healthy volunteers in the ketamine condition compared with the placebo condition (SMD = 1.50 [95% CI, 1.23-1.77]; P < .001). Each square shows the effect size for a single study, with the horizontal error bars representing the width of the 95% CI. The size of the squares reflects the weight attributed to each study. The diamond illustrates the summary effect size, and the width of the diamond depicts the width of the overall 95% CI.

Statistically significant between-sample inconsistency was found, with an I2 value of 75.7% (Cochran Q = 96.57; P < .001). The Egger test (z = 4.27; P < .001) suggested that publication bias was statistically significant. Trim-and-fill analysis estimated 3 missing studies on the left side of eFigure 1 in the Supplement, indicating that negative studies may have not been reported. However, our results remained statistically significant when the putative missing studies were included (SMD = 1.37 [95% CI, 1.07-1.67]; P < .001). Meta-regressions of effect sizes against age (n = 24)5,29,30,31,32,33,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,59,61 and sex (n = 22)25,29,30,31,33,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,48,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,59,61 showed that neither factor was a statistically significant moderator of effect sizes.

Ketamine Preparation

Both racemic ketamine and s-ketamine preparations resulted in a statistically significant increase in total symptom scores compared with placebo. Large effect sizes were found for racemic ketamine (SMD = 1.40 [95% CI, 1.12-1.68]; P < .001) and s-ketamine (SMD, 2.03 [95% CI, 1.15-2.92]; P < .001). There was no significant difference between the methods on the magnitude of the effect size.

Blinding Method

Unblinded or single-blind methods (SMD = 1.71 [95% CI, 1.02-2.39]; P < .001) and double-blind methods (SMD = 1.45 [95% CI, 1.15-1.75]; P < .001) both resulted in a statistically significant association of the ketamine condition with total symptoms. There was no significant difference between the methods on the magnitude of the effect size.

Infusion Method

Bolus and a continuous infusion (SMD = 1.55 [95% CI, 1.23-1.88]; P < .001) and a continuous infusion only (SMD = 1.27 [95% CI, 0.73-1.81]; P < .001) were both associated with a statistically significant increase in total symptoms. There was no significant difference between the methods on the magnitude of the effect size.

Single-Day vs Multiple-Day Studies

Two single-day studies29,30 (SMD = 2.29 [95% CI, 1.69-2.89]; P < .001) and 17 multiple-day studies25,31,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,48,50,51,52,53,55,56,61 (SMD = 1.39 [95% CI, 1.12-1.66]; P < .001) were associated with a statistically significant increase in total symptoms. Studies in which ketamine and placebo conditions were conducted on the same day found a significantly greater magnitude of effect (effect size, 2.29 [95% CI, 1.69-2.89] vs 1.39 [95% CI, 1.12-1.66]; P = .007) (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

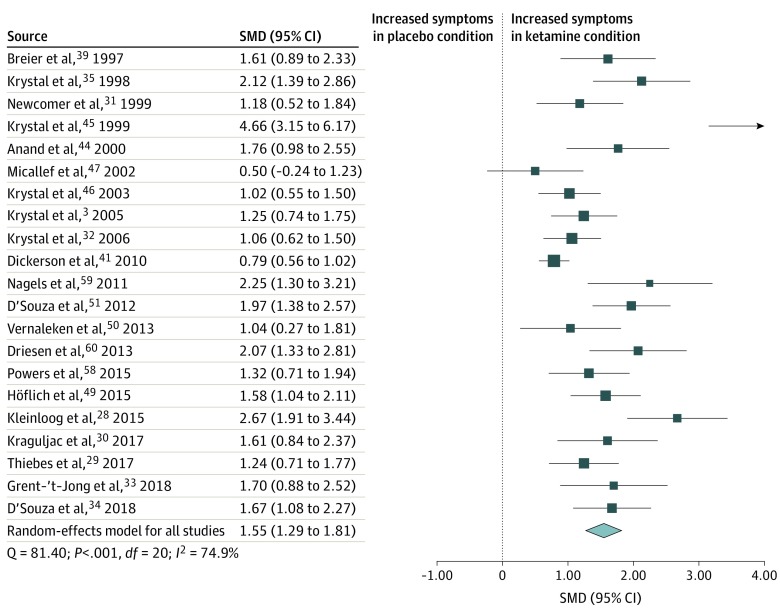

Positive Psychotic Symptoms

Positive symptom scores were analyzed using data from 21 studies3,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,39,41,44,45,46,47,49,50,51,58,59,60 consisting of 513 healthy participants exposed to the ketamine and placebo conditions. Positive symptom scores were transiently increased in the ketamine condition compared with the placebo condition (SMD = 1.55 [95% CI, 1.29-1.81]; P < .001) (Figure 3). The result remained statistically significant in all iterations of the leave-one-out analysis (SMD range, 1.47-1.60; P < .001).

Figure 3. Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) in Positive Symptom Scores for Healthy Volunteers After Ketamine vs Placebo Administration.

Scores include Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. A statistically significant increase in positive symptoms occurred in healthy volunteers in the ketamine condition compared with the placebo condition (SMD = 1.55 [95% CI, 1.29-1.81]; P < .001). Each square shows the effect size for a single study, with the horizontal error bars representing the width of the 95% CI. The size of the squares reflects the weight attributed to each study. The diamond illustrates the summary effect size, and the width of the diamond depicts the width of the overall 95% CI.

Statistically significant between-sample inconsistency was found, with an I2 value of 74.9% (Cochran Q = 81.40; P < .001). Findings of the Egger test (z = 5.06; P < .001) suggested that publication bias was significant. Trim-and-fill analysis estimated 1 missing study on the left side (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Results remained statistically significant with putative missing studies included (SMD = 1.49 [95% CI, 1.18-1.80]; P < .001). Meta-regressions of effect sizes against age (n = 20)3,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,39,41,44,45,46,47,49,50,51,58,59,60 or sex (n = 19)3,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,39,41,44,45,46,47,50,51,58,59,60 showed that neither was a statistically significant moderator of effect sizes.

Ketamine Preparation

Both racemic ketamine (SMD = 1.50 [95% CI, 1.17-1.82]; P < .001) and s-ketamine (SMD = 1.70 [95% CI, 1.23-2.18]; P < .001) preparations resulted in a statistically significant increase in positive symptom scores compared with placebo, both with large effect sizes. There was no significant difference between the methods on the magnitude of the effect size.

Blinding Method

Unblinded or single-blind (SMD = 1.32 [95% CI, 0.96-1.67]; P < .001) and double-blind (SMD = 1.68 [95% CI, 1.30-2.07]; P < .001) methods resulted in a statistically significant effect of ketamine condition on the positive symptoms. However, there was no significant difference in the magnitude of the effect between the 2 methods.

Infusion Method

Both a bolus followed by continuous infusion method (n = 19)28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,39,41,44,45,49,50,51,58,59,60,64 (SMD = 1.63 [95% CI, 1.36-1.90]; P < .001) and a continuous infusion alone (n = 2)46,47 (SMD = 0.84 [95% CI, 0.35-1.33]; P < .008) induced a statistically significant increase in positive symptoms. However, studies using a bolus and continuous infusion method induced a statistically significantly greater magnitude of effect (effect size, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.36-1.90) compared to continuous infusion alone (effect size, 0.84 [95% CI, 0.35-1.33]; P = .006) (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

Single-Day vs Multiple-Day Studies

Single-day (SMD = 1.54 [95% CI, 1.19-1.89]; P < .001) and multiple-day (SMD = 1.53 [95% CI, 1.15-1.90]; P < .001) studies both resulted in a statistically significant increase in positive symptoms. There was no significant difference in the magnitude of the effect between the 2 methods.

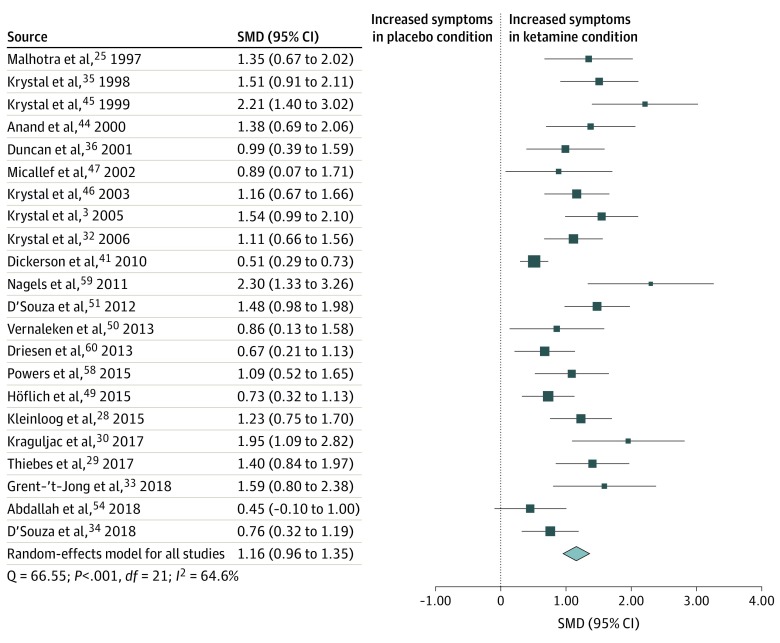

Negative Symptoms

Negative symptom scores were analyzed using data from 22 studies3,25,28,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,41,44,45,46,47,49,50,51,54,58,59,60 consisting of 527 healthy participants exposed to the ketamine and placebo conditions. Negative symptom scores were transiently increased in the ketamine condition compared with the placebo condition (SMD = 1.16 [95% CI, 0.96-1.35]; P < .001) (Figure 4). The result remained statistically significant in all iterations of the leave-one-out analysis (SMD range, 1.11-1.19; P < .001).

Figure 4. Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) in Negative Symptom Scores in Healthy Volunteers After Ketamine vs Placebo Administration.

Scores include Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. A statistically significant increase in negative symptoms occurred in healthy volunteers in the ketamine condition compared with the placebo condition (SMD = 1.16 [95% CI, 0.96-1.35]; P < .001). Each square shows the effect size for a single study, with the horizontal error bars representing the width of the 95% CI. The size of the squares reflects the weight attributed to each study. The diamond illustrates the summary effect size, and the width of the diamond depicts the width of the overall 95% CI.

Statistically significant between-sample inconsistency was found, with an I2 value of 64.6% (Cochran Q = 66.55; P < .001). Findings of the Egger test (z = 5.12; P < .001) suggested that publication bias was significant. Trim-fill analysis estimated 2 missing studies on the left side of eFigure 3 in the Supplement. Results remained statistically significant with putative missing studies included (SMD = 1.09 [95% CI, 0.89-1.30]; P < .001). Meta-regressions of effect sizes against age (n = 20)3,25,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,41,44,45,46,47,49,50,51,58,59,60 or sex (n = 19)3,25,28,29,30,33,34,35,36,41,44,45,46,47,50,51,58,59,60 showed that neither was a statistically significant moderator of effect sizes.

Ketamine Preparation

Both racemic ketamine (SMD = 1.13 [95% CI, 0.90-1.36]; P < .001) and s-ketamine (SMD = 1.25 [95% CI, 0.86-1.64]; P < .001) preparations resulted in a statistically significant transient increase in negative symptom scores compared with placebo, with large effect sizes. There was no significant difference between the methods on the magnitude of the effect size.

Blinding Method

Unblinded or single-blind (SMD = 0.98 [95% CI, 0.63-1.34]; P < .001) and double-blind (SMD = 1.29 [95% CI, 1.09-1.50]; P < .001) methods resulted in a statistically significant association of the ketamine condition with negative symptoms. There was no significant difference between the methods on the magnitude of the effect size.

Infusion Method

Both bolus and a continuous infusion (SMD = 1.19 [95% CI, 0.96-1.41]; P < .001) and a continuous infusion only (SMD = 1.06 [95% CI, 0.71-1.40]; P < .001) were associated with a statistically significant increase in negative symptoms. There was no significant difference between the methods on the magnitude of the effect size.

Single-Day vs Multiple-Day Studies

Single-day (SMD = 1.01 [95% CI, 0.56-1.47]; P < .001) and multiple-day (SMD = 1.16 [95% CI, 0.94-1.39]; P < .001) studies both resulted in a statistically significant increase in negative symptoms. However, there was no significant difference in the magnitude of the effect between the 2 methods.

Comparison of Positive and Negative Effect Sizes

A comparison of effect sizes demonstrated that the ketamine condition had a greater association with positive symptoms compared with negative symptoms (estimate, 0.36 [95% CI, 0.12-0.61]; z = 2.90; P = .004).

Subanalyses of BPRS and PANSS scales are presented in eMethods 10 in the Supplement. In summary, there was no significant difference between the 2 measures for any of the symptom domains (total, positive, and negative). Inconsistency analyses for the subanalyses are presented in eMethods 9 in the Supplement.

Effects of Ketamine in Patients With Schizophrenia

After 7 studies with overlapping data sets were excluded,64,65,66,67,68,69,70 3 studies were included in the analysis of patients with schizophrenia.25,26,27 No meta-analysis was possible because there were an insufficient number of papers. Studies with change scores were included in this section of the review.

Two studies25,26 examined the association of acute ketamine administration on total BPRS scores in patients with schizophrenia, and both found that ketamine was associated with a statistically significant increase in total BPRS scores. Two studies26,27 investigated the association of ketamine administration with positive and negative BPRS scores in patients with schizophrenia. Both found ketamine was associated with a statistically significant transient increase in positive symptoms. One study27 found ketamine was associated with a statistically significant increase in negative symptoms, but the other study26 to assess this factor did not find a significant association of ketamine with negative symptoms. The findings of these studies are summarized in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Risk of Bias Across Studies

Eight studies29,41,50,51,54,55,57,58 had a high risk of bias when the Newcastle-Ottawa tool was used to assess bias, mainly owing to not documenting certain aspects of the design protocol and therefore losing a point for being unclear. The Cochrane tool for assessment of bias across studies highlighted an unclear risk of bias across the selection bias domain but low risk across all other domains (performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias) (eMethods 2-4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Our main findings were that acute ketamine administration was associated with a large effect size for increases in positive, negative, and total symptom scores in healthy volunteers. Moreover, ketamine was associated with greater increases in positive symptoms than in negative symptoms.

Insufficient studies were available to conduct a meta-analysis of the association of ketamine with psychopathology in schizophrenia. Although transient increases in positive, negative, and total symptoms in patients with schizophrenia were reported, given the limited data, firm conclusions on effects in schizophrenia cannot be drawn, and further studies are needed. These findings extend the understanding of the symptoms associated with ketamine by showing that either racemic ketamine or s-ketamine are associated with positive, negative, and total symptoms in healthy volunteers with very large effect sizes across study settings and designs. To give some clinical context to the increased effect sizes seen with ketamine administration, the average mean difference in the total PANSS scores between the placebo and ketamine conditions was 18.40. Were this increase in symptom rating to occur in a patient with schizophrenia, it would approximately equate to a change from mild illness severity to markedly ill on the Clinical Global Impression Scale and represent a clinically meaningful increase in symptoms.71

This study identifies high levels of between-study inconsistency. Our subgroup analyses indicate that this inconsistency could be owing to study design factors. Specifically, studies that used a bolus plus infusion protocol showed larger increases (approximately double) in positive symptoms than those using only a continuous infusion. Moreover, studies that administered ketamine and placebo on the same day found a greater increase in total symptoms. The first finding could be owing to a faster time to and/or higher peak concentration of ketamine, consistent with a study showing a positive association between ketamine concentration and symptom induction.28 It is less clear why giving ketamine and placebo on the same day was associated with greater induction of symptoms, but this factor could reflect unblinding because one study was unblinded29 and the other was single blinded with the condition order randomized.30 Another explanation might be that both conditions on the same day controls better for the day-to-day variance that may occur in mood and biology. When heterogeneity was assessed for each individual subgroup, it was moderate to high for most analyses, suggesting that these subgroups did not account for all of the inconsistency seen within the meta-analysis.

Association of Age and Sex With Ketamine-Induced Psychopathology

Neither age nor sex were associated with the severity of psychotic symptoms induced by ketamine in healthy volunteers. However, the studies included in our meta-analysis only include adults (range of mean ages, 22-40 years). In children, fewer ketamine-induced symptoms might occur because children are less likely to experience psychotic symptoms than adults when given ketamine for anesthesia.1 However, animal studies find that ketamine has a greater neurotoxic effect in the period from puberty to early adulthood.72 Sex did not moderate the magnitude of effect for any of the symptom measures in our study, consistent with findings by Morgan and colleagues73 but in contrast with preclinical evidence that female rats are more susceptible than male rats to the neurotoxic74 and behavioral75 effects of ketamine. This difference between clinical and preclinical evidence may reflect the higher doses used in the animal studies (5-180 mg/kg) compared with humans (approximately 0.65 mg/kg).

Implications for Future Study Design and Reporting

Our findings are of particular relevance for the therapeutic use of ketamine and for future study design. First, we provide evidence that the use of bolus plus continuous infusion is associated with larger transient psychotomimetic effects. Second, inadequate reporting of methods precluded our ability to test the effects of other key methodological factors. One recommendation from our findings is therefore for future studies to report methods with greater detail to enable these factors to be investigated and aid replication.76 Details of specific relevance to studies such as these include the dose of ketamine and fasting status before receiving ketamine.

Ketamine Model of Schizophrenia

We found that ketamine was associated with the induction of both transient positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia in healthy people and with worsened symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. To the extent that any drug can model a complex disorder such as schizophrenia, the results of this meta-analysis support the use of ketamine to model schizophrenia-like or psychotomimetic symptoms and suggest that it provides a more comprehensive model of schizophrenia than drugs such as amphetamine, which does not reliably induce negative symptoms.3 However, we found that the induction of negative symptoms is statistically significantly less marked than that of positive psychotic symptoms in healthy people, and it was only seen in 1 of the 2 studies in schizophrenia.27 The negative symptom analysis had an extra study with a continuous infusion method. This difference may have reduced the effect because the continuous infusion method appears less likely than the bolus and continuous method to induce psychotic symptoms. However, the psychotic symptom analysis had more unblinded studies and fewer studies that completed both conditions on the same day. Notwithstanding these methodological considerations, this finding suggests that acute ketamine administration is associated with more positive than negative symptoms, although the magnitude of negative symptoms associated with ketamine is still large.

Implications for Therapeutic Use of Ketamine

Ketamine is being evaluated as a treatment for depression and some other disorders.2,6,7 Our findings highlight the potential risk that ketamine may induce transient positive (psychotic), negative, and other symptoms,77 particularly because the dose and route used to treat depression (approximately 0.5 mg/kg intravenously)6 is similar to those used in studies in this meta-analysis. Evidence suggests that ketamine can induce perceptual disturbances78 and psychotic symptoms in patients with depression (mean BPRS score, 12.6) with slightly higher positive BPRS scores than those seen in the studies included in this meta-analysis (average mean score across all BPRS studies, 7.5). People with a history of psychosis may be more vulnerable to the effects of ketamine. Our finding that using a bolus and continuous infusion method increases the effect of ketamine on psychotic symptoms highlights the importance of using slower infusions (40-60 minutes) of ketamine, an approach now adopted by some therapeutic trials.79

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include the relatively large sample size and inclusion of additional data provided by authors. However, there was significant inconsistency in the summary effect sizes, suggesting variability in effects between studies. This factor can be explained in part by differences in study design, as indicated by our sensitivity findings described above. We cannot explore the effect of other methodological differences that may contribute to inconsistency, such as differences in ketamine doses or fasting status, because few studies reported sufficient detail to allow this subanalysis. The inconsistency in total symptom score may also be explained by the inclusion of different BPRS versions. A mixture of 16, 18, 20, and 24 total item scales were used, and very few studies made it clear which items they included. Consequently, individual subgroup analyses of different versions could not be conducted.

There were several important differences in exclusion criteria between the studies. In particular, most of the studies did not exclude concurrent use of psychotropic drugs,25,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,80,81 and only a few studies excluded participants with prior ketamine exposure.30,31,42,52,53 Although some evidence suggests that repeated ketamine exposure does not cause behavioral sensitization in humans,82 it would have been useful to have examined these data in more depth to determine whether these factors may alter results owing to drug tolerance or differences in subjective experience due to familiarity with prior exposure. Nevertheless, we used a random-effects model, which is a robust method of calculating the effect size when there is statistically significant inconsistency between studies.83

Interestingly, the blinding status did not alter the magnitude of the effect size for total, positive, or negative symptoms. Blinding participants in these experiments may be very difficult because the dissociative anesthetic effects of ketamine can be very obvious to both participant and study personnel. This possibility may further explain the heterogeneity of results because the participants’ expectations may have contributed to their drug response. Future studies could include a low dose of ketamine or active comparator, such as midazolam hydrochloride, to address this important question.

We aimed to determine ketamine’s maximal ability to induce psychotomimetic symptoms. Where symptom scales were reported at different time points, we selected the point with the highest ketamine-induced symptom score. Where this occurred, the symptom measure for the placebo group was taken at the corresponding point. Where studies included different concentrations of ketamine, we used the highest dose, again using the symptom score for the corresponding placebo condition. Therefore, the effect sizes in this study are likely to be the largest effect size seen with ketamine. Further work is thus required to better characterize the dose-response relationship and time course of ketamine’s psychotomimetic affects.

Conclusions

We provide meta-analytic evidence that ketamine is associated with the induction of transient positive, negative, and total symptoms, with a greater increase in positive than negative symptoms in healthy volunteers. These findings support the use of ketamine as a pharmacological model of schizophrenia and, given that using a bolus plus continuous infusion method leads to greater positive psychotic symptoms, indicate that the bolus plus infusion is the best approach for this model. Ketamine is used to treat pain and for major depression. Our findings indicate a potential risk of ketamine inducing schizophreniform symptoms when it is used for these indications and that a slow infusion without bolus is preferable to minimize these risks. Further research is needed to determine the risk of these effects when ketamine is used therapeutically.

eMethods 1. Studies and Data Not Included in Meta-analysis

eMethods 2. Newcastle-Ottawa Assessment Scale for Cohort Studies

eMethods 3. Cochrane Tool for Assessment of Bias Within Individual Studies

eMethods 4. Cochrane Tool for Assessment of Bias Across Studies

eMethods 5. Refitting the Model Using ri’s Taking Values 0.1

eMethods 6. Refitting the Model Using ri’s Taking Values 0.7

eMethods 7. Comparison of the Effect of Ketamine on Positive and Negative Symptoms Using Correlation Coefficient of 0.1

eMethods 8. Comparison of the Effect of Ketamine on Positive and Negative Symptoms Using Correlation Coefficient of 0.7

eMethods 9. Heterogeneity Statistics for Subgroup Analyses

eMethods 10. Subanalyses of Type of Symptom Scale Used

eFigure 1. Funnel Plot for Total Symptoms

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot for Positive Symptoms

eFigure 3. Funnel Plot for Negative Symptoms

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analysis of Single-Day vs Multiple-Day Studies for Total Symptoms

eFigure 5. Subgroup Analysis of Method of Infusion (Bolus and a Continuous Infusion vs Only a Continuous Infusion) Positive Symptoms

eTable 1. Raw Data Used in Total BPRS and PANSS Analysis for Healthy Participants

eTable 2. Raw Data Used in Positive BPRS and PANSS Analysis for Healthy Participants

eTable 3. Raw Data Used in Negative BPRS and PANSS Analysis for Healthy Participants

eTable 4. Raw Data used in Total, Negative and Positive BPRS and PANSS Analysis for People With Schizophrenia

eTable 5. Study Description, Ketamine Method, Placebo Condition, Symptoms (BPRS and PANSS), and Exclusion Criteria in Studies Examining Acute Ketamine Administration in Healthy Controls

eTable 6. Study Description, Ketamine Administration Method, Placebo Condition, Symptoms (BPRS), and Exclusion Criteria in Studies Examining Acute Ketamine Administration to Patients With Schizophrenia

eReferences.

References

- 1.Stevenson C. Ketamine: a review. Updat Anaesth. 2005;20(20):25-29. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartzman RJ, Alexander GM, Grothusen JR, Paylor T, Reichenberger E, Perreault M. Outpatient intravenous ketamine for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Pain. 2009;147(1-3):107-115. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krystal JH, Perry EB Jr, Gueorguieva R, et al. Comparative and interactive human psychopharmacologic effects of ketamine and amphetamine: implications for glutamatergic and dopaminergic model psychoses and cognitive function. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):985-994. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vollenweider FX, Geyer MA. A systems model of altered consciousness: integrating natural and drug-induced psychoses. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56(5):495-507. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00646-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans: psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(3):199-214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGirr A, Berlim MT, Bond DJ, Fleck MP, Yatham LN, Lam RW. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive episodes. Psychol Med. 2015;45(4):693-704. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daly EJ, Singh JB, Fedgchin M, et al. Efficacy and safety of intranasal esketamine adjunctive to oral antidepressant therapy in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(2):139-148. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting: Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1-e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Souza DC, Fridberg DJ, Skosnik PD, et al. Dose-related modulation of event-related potentials to novel and target stimuli by intravenous Δ9-THC in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(7):1632-1646. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgan CJA, Freeman TP, Hindocha C, Schafer G, Gardner C, Curran HV. Individual and combined effects of acute delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on psychotomimetic symptoms and memory function. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):181. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0191-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):951-962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholson IR, Chapman JE, Neufeld RWJ. Variability in BPRS definitions of positive and negative symptoms. Schizophr Res. 1995;17(2):177-185. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00088-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreasen N. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms. University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreasen N. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. University of Iowa; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343(7829):d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Figure 8.6.a. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. Accessed August 24, 2019. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/figure_8_6_a_example_of_a_risk_of_bias_table_for_a_single.htm

- 18.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1-48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCutcheon RA, Pillinger T, Mizuno Y, et al. The efficacy and heterogeneity of antipsychotic response in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;(August):1-11. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0502-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brugger SP, Howes OD. Heterogeneity and homogeneity of regional brain structure in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(11):1104-1111. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkham JJ, Riley RD, Williamson PR. A multivariate meta-analysis approach for reducing the impact of outcome reporting bias in systematic reviews. Stat Med. 2012;31(20):2179-2195. doi: 10.1002/sim.5356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowden J, Tierney JF, Copas AJ, Burdett S. Quantifying, displaying and accounting for heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of RCTs using standard and generalised Q statistics. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malhotra AK, Pinals DA, Adler CM, et al. Ketamine-induced exacerbation of psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairment in neuroleptic-free schizophrenics. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17(3):141-150. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00036-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00243-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malhotra AK, Breier A, Goldman D, Picken L, Pickar D. The apolipoprotein E ε 4 allele is associated with blunting of ketamine-induced psychosis in schizophrenia: a preliminary report. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19(5):445-448. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00031-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinloog D, Uit den Boogaard A, Dahan A, et al. Optimizing the glutamatergic challenge model for psychosis, using S+-ketamine to induce psychomimetic symptoms in healthy volunteers. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(4):401-413. doi: 10.1177/0269881115570082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thiebes S, Leicht G, Curic S, et al. Glutamatergic deficit and schizophrenia-like negative symptoms: new evidence from ketamine-induced mismatch negativity alterations in healthy male humans. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2017;42(4):273-283. doi: 10.1503/jpn.160187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraguljac NV, Frölich MA, Tran S, et al. Ketamine modulates hippocampal neurochemistry and functional connectivity: a combined magnetic resonance spectroscopy and resting-state fMRI study in healthy volunteers. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(4):562-569. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newcomer JW, Farber NB, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, et al. Ketamine-induced NMDA receptor hypofunction as a model of memory impairment and psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20(2):106-118. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00067-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krystal JH, Madonick S, Perry E, et al. Potentiation of low dose ketamine effects by naltrexone: potential implications for the pharmacotherapy of alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(8):1793-1800. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grent-’t-Jong T, Rivolta D, Gross J, et al. Acute ketamine dysregulates task-related gamma-band oscillations in thalamo-cortical circuits in schizophrenia. Brain. 2018;141(8):2511-2526. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Souza DC, Carson RE, Driesen N, Johannesen J, Ranganathan M, Krystal JH; Yale GlyT1 Study Group . Dose-related target occupancy and effects on circuitry, behavior, and neuroplasticity of the glycine transporter-1 inhibitor pf-03463275 in healthy and schizophrenia subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(6):413-421. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krystal JH, Karper LP, Bennett A, et al. Interactive effects of subanesthetic ketamine and subhypnotic lorazepam in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1998;135(3):213-229. doi: 10.1007/s002130050503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duncan EJ, Madonick SH, Parwani A, et al. Clinical and sensorimotor gating effects of ketamine in normals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(1):72-83. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parwani A, Weiler MA, Blaxton TA, et al. The effects of a subanesthetic dose of ketamine on verbal memory in normal volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;183(3):265-274. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0177-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rowland LM, Astur RS, Jung RE, Bustillo JR, Lauriello J, Yeo RA. Selective cognitive impairments associated with NMDA receptor blockade in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(3):633-639. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breier A, Malhotra AK, Pinals DA, Weisenfeld NI, Pickar D. Association of ketamine-induced psychosis with focal activation of the prefrontal cortex in healthy volunteers. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6):805-811. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Berckel BN, Oranje B, van Ree JM, Verbaten MN, Kahn RS. The effects of low dose ketamine on sensory gating, neuroendocrine secretion and behavior in healthy human subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1998;137(3):271-281. doi: 10.1007/s002130050620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickerson D, Pittman B, Ralevski E, et al. Ethanol-like effects of thiopental and ketamine in healthy humans. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(2):203-211. doi: 10.1177/0269881108098612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abel KM, Allin MPG, Kucharska-Pietura K, et al. Ketamine and fMRI BOLD signal: distinguishing between effects mediated by change in blood flow versus change in cognitive state. Hum Brain Mapp. 2003;18(2):135-145. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kort NS, Ford JM, Roach BJ, et al. Role of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in action-based predictive coding deficits in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(6):514-524. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anand A, Charney DS, Oren DA, et al. Attenuation of the neuropsychiatric effects of ketamine with lamotrigine: support for hyperglutamatergic effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(3):270-276. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.3.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krystal JH, D’Souza DC, Karper LP, et al. Interactive effects of subanesthetic ketamine and haloperidol in healthy humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1999;145(2):193-204. doi: 10.1007/s002130051049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Limoncelli D, et al. Altered NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist response in recovering ethanol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(11):2020-2028. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Micallef J, Guillermain Y, Tardieu S, et al. Effects of subanesthetic doses of ketamine on sensorimotor information processing in healthy subjects. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2002;25(2):101-106. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200203000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boeijinga PH, Soufflet L, Santoro F, Luthringer R. Ketamine effects on CNS responses assessed with MEG/EEG in a passive auditory sensory-gating paradigm: an attempt for modelling some symptoms of psychosis in man. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(3):321-337. doi: 10.1177/0269881107077768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Höflich A, Hahn A, Küblböck M, et al. Ketamine-induced modulation of the thalamo-cortical network in healthy volunteers as a model for schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(9):1-11. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vernaleken I, Klomp M, Moeller O, et al. Vulnerability to psychotogenic effects of ketamine is associated with elevated D2/3-receptor availability. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(4):745-754. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D’Souza DC, Ahn K, Bhakta S, et al. Nicotine fails to attenuate ketamine-induced cognitive deficits and negative and positive symptoms in humans: implications for schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(9):785-794. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rowland LM, Beason-Held L, Tamminga CA, Holcomb HH. The interactive effects of ketamine and nicotine on human cerebral blood flow. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010;208(4):575-584. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1758-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stone JM, Abel KM, Allin MPG, et al. Ketamine-induced disruption of verbal self-monitoring linked to superior temporal activation. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(1):33-48. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abdallah CG, De Feyter HM, Averill LA, et al. The effects of ketamine on prefrontal glutamate neurotransmission in healthy and depressed subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(10):2154-2160. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0136-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Passie T, Karst M, Borsutzky M, Wiese B, Emrich HM, Schneider U. Effects of different subanaesthetic doses of (S)-ketamine on psychopathology and binocular depth inversion in man. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17(1):51-56. doi: 10.1177/0269881103017001698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Horacek J, Brunovsky M, Novak T, et al. Subanesthetic dose of ketamine decreases prefrontal theta cordance in healthy volunteers: implications for antidepressant effect. Psychol Med. 2010;40(9):1443-1451. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan HL, Turner DC, Corlett PR, et al. Exploring the impact of ketamine on the experience of illusory body ownership. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(1):35-41. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Powers AR III, Gancsos MG, Finn ES, Morgan PT, Corlett PR. Ketamine-induced hallucinations. Psychopathology. 2015;48(6):376-385. doi: 10.1159/000438675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nagels A, Kirner-Veselinovic A, Krach S, Kircher T. Neural correlates of S-ketamine induced psychosis during overt continuous verbal fluency. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):1307-1314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Driesen NR, McCarthy G, Bhagwagar Z, et al. Relationship of resting brain hyperconnectivity and schizophrenia-like symptoms produced by the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine in humans. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(11):1199-1204. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathalon DH, Ahn K-H, Perry EBJ Jr, et al. Effects of nicotine on the neurophysiological and behavioral effects of ketamine in humans. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morrison RL, Fedgchin M, Singh J, et al. Effect of intranasal esketamine on cognitive functioning in healthy participants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(4):1107-1119. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-4828-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van de Loo AJAE, Bervoets AC, Mooren L, et al. The effects of intranasal esketamine (84 mg) and oral mirtazapine (30 mg) on on-road driving performance: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2017;234(21):3175-3183. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4706-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lahti AC, Holcomb HH, Medoff DR, Tamminga CA. Ketamine activates psychosis and alters limbic blood flow in schizophrenia. Neuroreport. 1995;6(6):869-872. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199504190-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lahti AC, Koffel B, LaPorte D, Tamminga CA. Subanesthetic doses of ketamine stimulate psychosis in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13(1):9-19. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00131-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Holcomb HH, Lahti AC, Medoff DR, Cullen T, Tamminga CA. Effects of noncompetitive NMDA receptor blockade on anterior cingulate cerebral blood flow in volunteers with schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30(12):2275-2282. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Medoff DR, Holcomb HH, Lahti AC, Tamminga CA. Probing the human hippocampus using rCBF: contrasts in schizophrenia. Hippocampus. 2001;11(5):543-550. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.LaPorte DJ, Lahti AC, Koffel B, Tamminga CA. Absence of ketamine effects on memory and other cognitive functions in schizophrenia patients. J Psychiatr Res. 1996;30(5):321-330. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(96)00018-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lahti AC, Warfel D, Michaelidis T, Weiler MA, Frey K, Tamminga CA. Long-term outcome of patients who receive ketamine during research. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(10):869-875. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01037-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malhotra AK, Adler CM, Kennison SD, Elman I, Pickar D, Breier A. Clozapine blunts N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist-induced psychosis: a study with ketamine. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(8):664-668. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00546-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel RR. What does the PANSS mean? Schizophr Res. 2005;79(2-3):231-238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Farber NB, Wozniak DF, Price MT, et al. Age-specific neurotoxicity in the rat associated with NMDA receptor blockade: potential relevance to schizophrenia? Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(12):788-796. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00046-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morgan CJA, Perry EB, Cho H-S, Krystal JH, D’Souza DC. Greater vulnerability to the amnestic effects of ketamine in males. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;187(4):405-414. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0409-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Wozniak DF, Benshoff ND, Olney JW. A comparative evaluation of the neurotoxic properties of ketamine and nitrous oxide. Brain Res. 2001;895(1-2):264-267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02079-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Winters WD, Hance AJ, Cadd GC, Lakin ML. Seasonal and sex influences on ketamine-induced analgesia and catalepsy in the rat: a possible role for melatonin. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25(10):1095-1101. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90156-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perry EB Jr, Cramer JA, Cho H-S, et al. ; Yale Ketamine Study Group . Psychiatric safety of ketamine in psychopharmacology research. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;192(2):253-260. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0706-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):856-864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fond G, Loundou A, Rabu C, et al. Ketamine administration in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(18):3663-3676. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3664-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Musso F, Brinkmeyer J, Ecker D, et al. Ketamine effects on brain function—simultaneous fMRI/EEG during a visual oddball task. Neuroimage. 2011;58(2):508-525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Umbricht D, Schmid L, Koller R, Vollenweider FX, Hell D, Javitt DC. Ketamine-induced deficits in auditory and visual context-dependent processing in healthy volunteers: implications for models of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(12):1139-1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cho H-S, D’Souza DC, Gueorguieva R, et al. Absence of behavioral sensitization in healthy human subjects following repeated exposure to ketamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;179(1):136-143. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2066-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cheung MW-L, Cheung SF. Random-effects models for meta-analytic structural equation modeling: review, issues, and illustrations. Res Synth Methods. 2016;7(2):140-155. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Studies and Data Not Included in Meta-analysis

eMethods 2. Newcastle-Ottawa Assessment Scale for Cohort Studies

eMethods 3. Cochrane Tool for Assessment of Bias Within Individual Studies

eMethods 4. Cochrane Tool for Assessment of Bias Across Studies

eMethods 5. Refitting the Model Using ri’s Taking Values 0.1

eMethods 6. Refitting the Model Using ri’s Taking Values 0.7

eMethods 7. Comparison of the Effect of Ketamine on Positive and Negative Symptoms Using Correlation Coefficient of 0.1

eMethods 8. Comparison of the Effect of Ketamine on Positive and Negative Symptoms Using Correlation Coefficient of 0.7

eMethods 9. Heterogeneity Statistics for Subgroup Analyses

eMethods 10. Subanalyses of Type of Symptom Scale Used

eFigure 1. Funnel Plot for Total Symptoms

eFigure 2. Funnel Plot for Positive Symptoms

eFigure 3. Funnel Plot for Negative Symptoms

eFigure 4. Subgroup Analysis of Single-Day vs Multiple-Day Studies for Total Symptoms

eFigure 5. Subgroup Analysis of Method of Infusion (Bolus and a Continuous Infusion vs Only a Continuous Infusion) Positive Symptoms

eTable 1. Raw Data Used in Total BPRS and PANSS Analysis for Healthy Participants

eTable 2. Raw Data Used in Positive BPRS and PANSS Analysis for Healthy Participants

eTable 3. Raw Data Used in Negative BPRS and PANSS Analysis for Healthy Participants

eTable 4. Raw Data used in Total, Negative and Positive BPRS and PANSS Analysis for People With Schizophrenia

eTable 5. Study Description, Ketamine Method, Placebo Condition, Symptoms (BPRS and PANSS), and Exclusion Criteria in Studies Examining Acute Ketamine Administration in Healthy Controls

eTable 6. Study Description, Ketamine Administration Method, Placebo Condition, Symptoms (BPRS), and Exclusion Criteria in Studies Examining Acute Ketamine Administration to Patients With Schizophrenia

eReferences.