Abstract

Background

Findings on the association between Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) infection and suicide are contradictory. This paper aimed to resolve this uncertainty by conducting a meta-analysis.

Methods

We found the relevant studies using keywords include “Toxoplasmosis” and “Suicide” and the related synonyms in international databases such as ISI, Medline, and Scopus. The eligible studies were included in the meta-analysis phase. The random effect approach was applied to combine the results.

Results

Out Of 150 initial studies, 15 were included in the meta-analysis. Odds of suicide in people with T. gondii infection was 43% (OR: 1.43, 95%CI; 1.15 to 1.78) higher than those without this infection. The test for publication bias was not statistically significant, which indicates the absence of likely publication bias.

Conclusion

This study confirms that T. gondii infection is a potential risk factor for suicide. To reduce cases of suicide attributable to T. gondii infection, it is recommended to implement some measures to prevent and control the transmission of the disease.

Keywords: T. Gondii, Suicide, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

Suicide, as one of the major health threats for humans, leads to more than 800,000 deaths globally each year, such that one person per second dies from suicide. Therefore, suicide accounts for 1.5% of all deaths [1].

Many risk factors increase the risk of suicide. The mental disorders, misuse of drugs, mental states, cultural factors, family, and social and genetic conditions elevate the risk of suicide [2].

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) is one of the most common parasites in humans. This parasite exists in approximately one-third of the world’s population and also more than 40 million people in the United States [3, 4]. The life cycle of this parasite occurs in intermediate hosts such as humans (by asexual reproduction) and felines being the definitive hosts for sexual reproduction. Consumption of T. gondii -contaminated food, vegetable, water, and muscle cysts present in undercooked meat and also congenital infection is the most common route of disease transmission [5–7]. Infection by this parasite in pregnancy can lead to mental disorders and deafness, abortion, and vision disturbances after birth [8, 9]. This parasite leads to severe complications such as encephalitis and pneumonitis in immunocompromised persons (such as organ recipients and cancer or HIV/AIDS patients). However, in immunocompetent individuals, clinical signs are mild and self-limited such as fever and cervical lymphadenopathy [10–12]. Moreover, latent infections are frequently associated with tissue cyst of T. gondii in the skeletal muscle and brain tissue, leading to psychiatric complications [12, 13]. The tachyzoite form of the disease is responsible for the acute stage of the infection [13]. It has been well documented that T. gondii infection may lead to changes in the behavior of its hosts [3, 4]. It has been reported that the T. gondii infection may cause reduced Intelligence Quotient (IQ) [14], personality changes [15], and psychomotor performance [16]. T. gondii infection affects the behavior of humans, such that recent clinical data demonstrate that T. gondii infection antibody may play a role in the pathophysiology of suicide. The studies documented that these elevated levels of cytokines are associated with depression and suicide [17].

However, the results of the studies on the association of T. gondii infection and suicide are not consistent. While some studies claim that there is no association between suicide and T. gondii infection [18, 19], some others suggest that these two factors are correlated [20]. One of the resolutions to overcome this conflict is to perform a meta-analysis, which is a method to extract one single effect size from several multiple studies. If studies can extract a causal association between T. gondii infection and suicide, we may identify persons with an increased probability of suicide and thus find ways to prevent it.

The present study aimed to provide a summary estimate for the association of T. gondii infection with suicide and to evaluate whether T. gondii is associated with the risk of suicide or not.

Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) tool was applied to conduct this study.

Protocol and registration

The protocol was registered in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (No. 9710256386).

Eligibility criteria

Based on Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study type (PICOS) principles, we selected the analytical studies (including case-control, cohort, cross-sectional) that reported an association between T. gondii infection (as a predictor) and suicide (as outcome) in all age and sex groups of the population. In this process, we did not set any time limitation on the selection of the studies.

Information sources

Medline, ISI, and Scopus databases were searched to retrieve the related studies up to 25 March 2019. Moreover, we searched the reference list of the screened studies to find the missed studies.

Searching literature

Two major keywords including suicide (such as Suicide OR Suicides OR ‘Suicide, Attempted’ OR ‘Attempted Suicide’ OR Parasuicide OR Parasuicides OR ‘Suicide, Completed’ OR ‘Completed Suicides’ OR ‘Suicides, Completed’ OR ‘Completed Suicide’) AND T. gondii (Toxoplasma OR Toxoplasmas OR ‘Toxoplasma gondii’ OR ‘Toxoplasma gondius’ OR ‘gondius, Toxoplasma’ OR Toxoplasmosis OR ‘Toxoplasma gondii Infection’ OR ‘Infection, Toxoplasma gondii’) were used to construct a search strategy for each database. In Pubmed, we searched for studies using Mesh terms. In Scopus, the search was done on title, abstract, and keyword. In Web of Sciences, the studies were searched based on the topic.

Study selection

We selected those studies that assess the association of T. gondii with a suicide. Two independent reviewers searched the databases and then screened the title, abstract, and full text of the studies to choose the relevant studies. The disagreement between the two reviewers was resolved by a third person.

Data collection process

An EXCEL sheet was designed to extract the required data of the selected studies. The sheet included the name of the first author, year of publication, country of the study, age, sex, sample size, and effect size of the association.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Newcastle and Ottawa statement (NOS) checklist was applied to assess the quality of the studies.

Summary measures

Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) was determined as the effect size for this study.

Synthesis of results

The final selected studies were included in the meta-analysis. A random-effect approach was used to combine the studies and produce one single estimate. I2 statistics and chi-square tests were used to assess the existence of heterogeneity among the studies.

Risk of bias across studies

We used Egger and Begg test to investigate publication bias in reporting the results.

Results

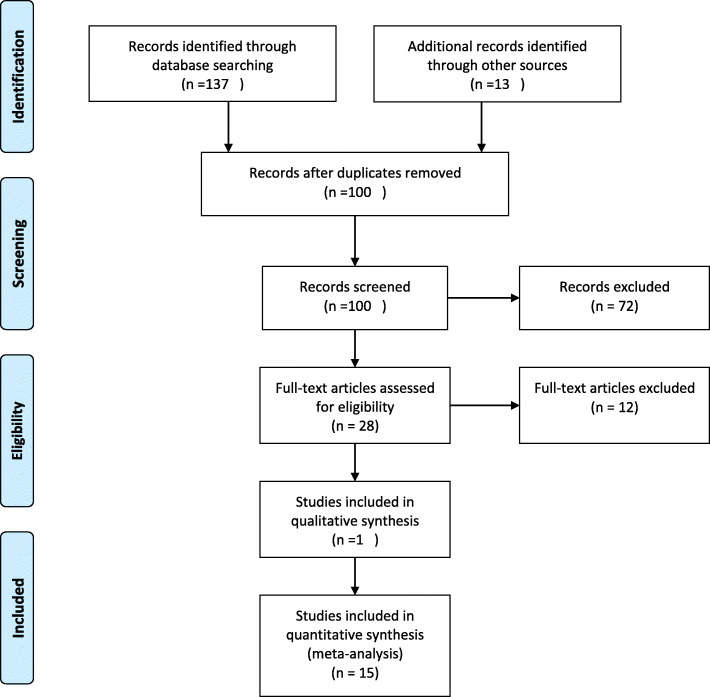

Figure 1 demonstrates the process of performing the study. The initial search in the databases yielded 150 studies. After discarding duplicates and irrelevant studies, 15 studies were qualified to be included in the quantitative analysis phase (Meta-analysis), and one study included in the qualitative phase [4, 17–31].

Fig. 1.

Process of performing the systematic review

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies included in final phase. In terms of study setting, the selected studies were conducted in the United States, Turkey, Germany, Mexico, Poland, Denmark, France, Russia, South Korea, and Iran. Out Of 16 studies, seven reported the positive association of T. gondii infection with a suicide, and eight studies did not find any significant relationships between T. gondii infection and suicide. By contrary, one study found a protective association between T. gondii and suicide.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in final phase

| Author | Country | age | Male | Female | Design | Sample size | Number of Suicide Case | Positive Cases | Number of Control group | Positive controls | Conclusion | Quality score (out of 8) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arling (2009) | United states | 40±10 | 90 | 149 | Case-control | 234 | 81 | 11 | 153 | 17 | Positive association | 8 | [18] |

| Yagmur F (2010) | Turkey | 24.3±7.6 | 82 | 318 | Case-control | 400 | 200 | 82 | 200 | 56 | Positive association | 7 | [31] |

| Okusaga (2014) | Germany | 38.6±11.1 | 600 | 350 | Case-control | 950 | 351 | 146 | 599 | 226 | No association | 8 | [19] |

| Pedersen, M. G (2012) | Denmark | Pregnancy ages | – | 45,788 | prospective cohort study | 45,788 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Positive association | 6 | [29] |

| Alvarado-Esquivel, C (2013) | Mexico | All ages | 88 | 195 | Case-control | 283 | 156 | 7 | 127 | 10 | Negative association | 7 | [22] |

| Samojlowicz, D (2013) | Poland | 19 to 86 years | 115 | 12 | Case-control | 127 | 41 | 26 | 86 | 42 | No association | 6 | [30] |

| Coryell W (2016) | United states | 17.5 ± 1.7 | 30 | 78 | Case-control | 108 | 17 | 2 | 91 | 2 | No association | 7 | [19] |

| Gale, S. D (2016) | United states | 20 to 80 years | 2469 | 3018 | Cross-Sectional | 5487 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No association | 7 | [27] |

| Okusaga, O (2016) | United states | 40±11.5 | 518 | 307 | Case-control | 825 | 308 | 127 | 517 | 200 | No association | 8 | [18] |

| Sugden, K (2016) | United states | 3 to 38 years | 423 | 414 | prospective cohort study | 837 | 16 | 8 | 821 | 228 | No association | 8 | [20] |

| Ansari-Lari, M (2017) | Iran | 40±10 | 72 | 27 | Case-control | 99 | 29 | 8 | 70 | 34 | No association | 7 | [5] |

| Dickerson, F (2017) | United states | 38.6±13 | 88 | 74 | Case-control | 162 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Positive association | 8 | [25] |

| Bak, J (2018) | South Korea | 43.75 ± 16.75 | 141 | 149 | Case-control | 290 | 155 | 21 | 135 | 8 | Positive association | 7 | [23] |

| Dickerson, F (2018) | United states | 36±12 | 647 | 645 | prospective cohort study | 1292 | N/A | NA | N/A | NA | Positive association | 8 | [24] |

| Fond, G (2018) | France | 32±8.6 | 184 | 66 | prospective cohort study | 250 | 9 | 7 | 241 | 177 | No association | 8 | [26] |

| Ling, Vinita | Eurepe | 0–75+ | – | – | Ecologcal study | – | – | – | – | – | Positive association | 7 | [32] |

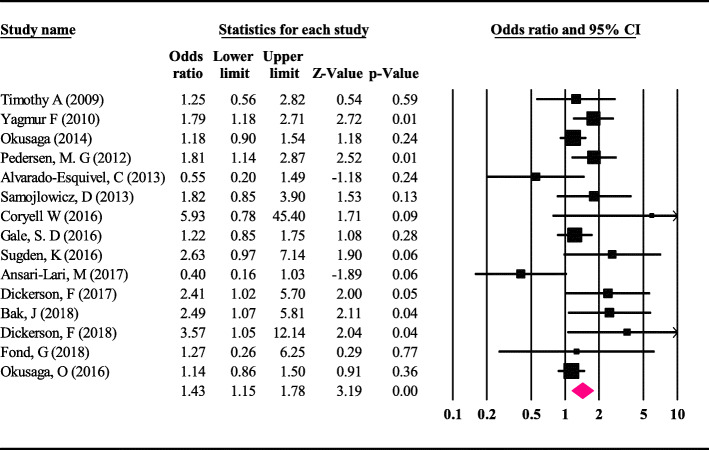

The strongest and the weakest associations were reported by Dickerson (2.41) and Okusaga (1.14), respectively.

The results of the meta-analysis indicates that the odds ratio of T. gondii infection and suicide was 1.43 (95%CI; 1.15 to 1.78), which is statistically significant (Fig. 2). Therefore, it can be stated that a person is seropositive in terms of T. gondii if has a 43% risk of suicide compared with the non-infected person.

Fig. 2.

Odds ratio with 95% confidence interval for the studies and meta-analysis

The Begg test was not statistically significant (P-value = 0.28) in assessing the existence of publication bias, indicating the absence of publication bias in the study.

Examining the degree of heterogeneity among studies using the I2 test demonstrated a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 0.71). Therefore, we used a random-effect model to perform the meta-analysis. In addition, Beg’s test was not significant, which indicate absence of publication bias (P = 0.26).

In the qualitative phase, one study assessed the association of T. gondii infection with suicide using ecological studies. This study showed that after adjusting potential confounders, there is a significant association between seroprevalence of T. gondii infection and suicide rate among European countries [31].

Discussion

In this paper, we presented the result of meta-analysis for the association of T. gondii infection and suicide. Combining the results of 15 eligible studies, we confirmed that developing T. gondii infection may increase the risk of suicide by 43%. Therefore, individuals with T. gondii infection had higher probability to suicide than without T. gondii infection. Although, strength of the obtained risk in our study is not very substantial, it is a remarkable risk should be considered.

The literature has been provided the evidence for existence of association of T. gondii infection with mood disorders such as schizophrenia [32], bipolar disorder [33, 34] and suicide [35]. In a review paper published by Pao-Chu Hsu, it was concluded that T. gondii is associated with mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, suicide attempt, depression, and other neuropsychiatric diseases [36]. Moreover, in an ecological study investigated association of T. gondii with Suicide rates in women, it revealed that there is a positive association between rates of infection with T. gondii and suicide in 20 European countries and suicide is more common in women of postmenopausal age [31] .

The studies explained the mechanism of association of T. gondii infection with behavioral changes well. After proliferation of this protozoan parasite in different organs during the acute phase, the parasite preferentially forms cysts in the brain and establishes a chronic infection that is a balance among parasite’s evasion of the immune response and host immunity. Different cells of brain, such as neurons and astrocytes, can be infected. In laboratory surveys using non-brain cells have showed deep effects of the infection on gene expression of host cells, containing molecules that increase the immune response and those involved in signal transduction pathways, suggesting that similar effects could happen in infected cells of brain. T. gondii infection also appears to affect signaling pathways in the brain. Consequently, chronic infection reactivation with the parasite (rupture of cyst and proliferation of tachyzoites) in the brain may play a role in the onset of the disease [37]. In fact, T. gondii act on suicide behavioral through two pathways: disturbance in dopamine synthesis and activation of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) that reduce amount of serotonin in brain [36]. The studies show that individuals who suicide had a significantly higher IgG antibody to T. gondii compared with those without a suicide [17]. Moreover, a study showed the association of T. gondii antibodies and suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia, which is consistent with reports on associations between T. gondii and suicidal behavior in patients with mood disorders [17], overall psychiatric patients [20, 31]. T. gondii infection plays a role in the higher later occurrence of suicide in lifespan [31]. Experimental studies have shown that the relationship between T. gondii infection and suicide is reinforced by the relative tropism of T. gondii cysts in greater density in the amygdala nucleus or the frontal cortex, which are normally involved in regulating behavior [38]. The following explanations can illuminate the probable mechanisms of a relationship between T. gondii and suicidal behavior. First, T. gondii induces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN- γ, IL-6, and IL-12) by activating lymphocytes and macrophages [39]. Interferon-gamma, by triggering lymphocytes and macrophages, blocks the development of T. gondii [40]. In response to the T. gondii, cytokines are produced, leading to an increase in the activity of enzymes kynurenine monooxygenase (KMO) and indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO). In the metabolism of the amino acid tryptophan, KMO and IDO are restricted. Tryptophan evacuation via the kynurenine pathway (3-hydroxyl kynurenine, 3-OH-kynurenine, and quinolinic acid, QUIN) limits the growth and spread of infection [39]. Moreover, it can decrease neurotransmitter serotonin synthesis in the brain and may raise the susceptibility to triggering suicide risk factors such as depression, impulsivity, and aggression [41]. Changes in glutamate and dopamine neurotransmission have shown a key role in suicide and suicidal behavior [42, 43]. Finally, changes in neurotransmitters can play a role in behavioral development that increases the risk of suicide [35, 44].

In this study, we had several limitations. One major limitation of the present study is that we just included English language studies and overlooked non-English ones. Therefore, we cannot assess the effect of non-English studies on our results. Second, we included only studies had full text, and therefore, we excluded the studies without full text. However, it seems that more investigations on the association of T. gondii infection with suicide, especially on mechanisms of pathogenesis of T. gondii infection in suicidal behavior in required. Furthermore, updating the review articles about T. gondii infection and suicidal behavior without time and language limitations is suggested.

Despite the mentioned limitation, this study provides important clues to inform policy-makers about the serious role of T. gondii infection in a suicide. Therefore, considering the consequences and complications of T. gondii infection such as suicide, control, prevention, and its treatment, this parasitic infection must be highly considered.

Conclusion

Our study is the first meta-analysis and systematic review to assess the association of T. gondii infection and a suicide. T. gondii significantly increases the risk of a suicide. Therefore, to reduce the risk of the suicide associated with T. gondii, it is recommended to take some measures to prevent and control of transmission of T. gondii.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Abbreviations

- IQ

Intelligence Quotient

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- OR

Odds Ratio

- CI

Confidence Interval

- NOS

Newcastle and Ottawa statement

Authors’ contributions

E.S: Search, reviewing, data extraction, writing the primary draft, and final approval. F.F: Search, reviewing, writing the primary draft, and final approval of the manuscript. R.H: Design, reviewing, and final approval of the manuscript. L.D: Design, data extraction, reviewing, and final approval of the manuscript. Y.M: Design, statistical analysis, and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (No. 9710256386). The funder has no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The corresponding author is responsible for data. Access to all relevant raw data will be free to any scientist.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of the study was proved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (No. IR.UMSHA.REC.1397.73).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Eissa Soleymani, Email: Soleymanieissa@gmail.com.

Fariba Faizi, Email: faizeif@yahoo.com.

Rashid Heidarimoghadam, Email: r.heidari@umsha.ac.ir.

Lotfollah Davoodi, Email: Lotfdavoodi@yahoo.com.

Younes Mohammadi, Email: u.mohammadi@umsha.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY. Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:307–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawton K, Saunders KE, O'Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanić Ž, Fureš R. Toxoplasmosis: a global zoonosis. Veterinaria. 2020;69(1):31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansari-Lari M, Farashbandi H, Mohammadi F. Association of Toxoplasma gondii infection with schizophrenia and its relationship with suicide attempts in these patients. Tropical Med Int Health. 2017;22(10):1322–1327. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert-Gangneux F, Dardé M-L. Epidemiology of and diagnostic strategies for toxoplasmosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(2):264–296. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guimarães EV, Carvalho L, Barbosa HS. Interaction and cystogenesis of toxoplasma gondii within skeletal muscle cells in vitro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(2):170–174. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster JP, Kaushik M, Bristow GC, McConkey GA. Toxoplasma gondii infection, from predation to schizophrenia: can animal behaviour help us understand human behaviour? J Exp Biol. 2013;216(1):99–112. doi: 10.1242/jeb.074716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carellos E, Caiaffa W, Andrade G, Abreu M, Januário J. Congenital toxoplasmosis in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil: a neglected infectious disease? Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(3):644–655. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fatollahzadeh M, Jafari R, Mohammadi F, Ghayemmaghammi N, Rezvan S, Parsaii M, Sarafraz S, Sadeghpour S, Alizadeh S, Safari M. Study of anti-Toxoplasma IgG and IgM seropositivity among subjects referred to the central laboratory in Tabriz, Iran, 2013-2014. Avicennaj Clin Microb Infec. 2016;3(3). 10.17795/ajcmi-35975.

- 10.Elhence P, Agarwal P, Prasad KN, Chaudhary RK. Seroprevalence of toxoplasma gondii antibodies in north Indian blood donors: implications for transfusion transmissible toxoplasmosis. Transfus Apher Sci. 2010;43(1):37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arefkhah N, Pourabbas B, Asgari Q, Moshfe A, Mikaeili F, Nikbakht G, Sarkari B. Molecular genotyping and serological evaluation of toxoplasma gondii in mothers and their spontaneous aborted fetuses in southwest of Iran. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;66:101342. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2019.101342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soleymani E, Babamahmoodi F, Davoodi L, Marofi A, Nooshirvanpour P. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in an AIDS patient with Normal CD4 count: a case report. Iran J Parasitol. 2018;13(2):317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363(9425):1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flegr J, Preiss M, Klose J, Havlícek J, Vitáková M, Kodym P. Decreased level of psychobiological factor novelty seeking and lower intelligence in men latently infected with the protozoan parasite toxoplasma gondii dopamine, a missing link between schizophrenia and toxoplasmosis? Biol Psychol. 2003;63(3):253–268. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(03)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flegr J, Zitková Š, Kodym P, Frynta D. Induction of changes in human behaviour by the parasitic protozoan toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology. 1996;113(1):49–54. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000066269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Havlíček J, Gašová Z, Smith AP, Zvára K, Flegr J. Decrease of psychomotor performance in subjects with latent ‘asymptomatic’toxoplasmosis. Parasitology. 2001;122(5):515–520. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001007624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arling TA, Yolken RH, Lapidus M, Langenberg P, Dickerson FB, Zimmerman SA, Balis T, Cabassa JA, Scrandis DA, Tonelli LH, et al. Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers and history of suicide attempts in patients with recurrent mood disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(12):905–908. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181c29a23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okusaga O, Langenberg P, Sleemi A, Vaswani D, Giegling I, Hartmann AM, Konte B, Friedl M, Groer MW, Yolken RH. Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers and history of suicide attempts in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;133(1–3):150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickerson F, Origoni A, Schweinfurth LA, Stallings C, Savage CL, Sweeney K, Katsafanas E, Wilcox HC, Khushalani S, Yolken R. Clinical and serological predictors of suicide in schizophrenia and major mood disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2018;206(3):173–178. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yagmur F, Yazar S, Temel HO, Cavusoglu M. May toxoplasma gondii increase suicide attempt-preliminary results in Turkish subjects? Forensic Sci Int. 2010;199(1–3):15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarado-Esquivel C, Sanchez-Anguiano LF, Arnaud-Gil CA, Lopez-Longoria JC, Molina-Espinoza LF, Estrada-Martinez S, Liesenfeld O, Hernandez-Tinoco J, Sifuentes-Alvarez A, Salas-Martinez C. Toxoplasma gondii infection and suicide attempts: a case-control study in psychiatric outpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(11):948–952. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bak J, Shim SH, Kwon YJ, Lee HY, Kim JS, Yoon H, Lee YJ. The association between suicide attempts and toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16(1):95–102. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coryell W, Yolken R, Butcher B, Burns T, Dindo L, Schlechte J, Calarge C. Toxoplasmosis titers and past suicide attempts among older adolescents initiating SSRI treatment. Arch Suicide Res. 2016;20(4):605–613. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1158677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickerson F, Wilcox HC, Adamos M, Katsafanas E, Khushalani S, Origoni A, Savage C, Schweinfurth L, Stallings C, Sweeney K, et al. Suicide attempts and markers of immune response in individuals with serious mental illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;87:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fond G, Boyer L, Schurhoff F, Berna F, Godin O, Bulzacka E, Andrianarisoa M, Brunel L, Aouizerate B, Capdevielle D, et al. Latent toxoplasma infection in real-world schizophrenia: results from the national FACE-SZ cohort. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale SD, Berrett AN, Brown B, Erickson LD, Hedges DW. No association between current depression and latent toxoplasmosis in adults. Folia Parasitol (Praha). 2016;63:032. 10.14411/fp.2016.032. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Okusaga O, Duncan E, Langenberg P, Brundin L, Fuchs D, Groer MW, Giegling I, Stearns-Yoder KA, Hartmann AM, Konte B, et al. Combined toxoplasma gondii seropositivity and high blood kynurenine--linked with nonfatal suicidal self-directed violence in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;72:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen MG, Mortensen PB, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Postolache TT. Toxoplasma gondii infection and self-directed violence in mothers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1123–1130. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samojlowicz D, Borowska-Solonynko A, Golab E. Prevalence of toxoplasma gondii parasite infection among people who died due to sudden death in the capital city of Warsaw and its vicinity. Przegl Epidemiol. 2013;67(1):29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Pinto L, Poulton R, Williams BS, Caspi A. Is toxoplasma Gondii infection related to brain and behavior impairments in humans? Evidence from a population-representative birth cohort. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ling VJ, Lester D, Mortensen PB, Langenberg PW, Postolache TT. Toxoplasma gondii seropositivity and suicide rates in women. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(7):440. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318221416e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prandovszky Emese, Gaskell Elizabeth, Martin Heather, Dubey J. P., Webster Joanne P., McConkey Glenn A. The Neurotropic Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii Increases Dopamine Metabolism. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e23866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Barros JLVM, Barbosa IG, Salem H, Rocha NP, Kummer A, Okusaga OO, Soares JC, Teixeira AL. Is there any association between toxoplasma gondii infection and bipolar disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;209:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Djalalinia S, Moghaddam SS, Peykari N, Kasaeian A, Sheidaei A, Mansouri A, Mohammadi Y, Parsaeian M, Mehdipour P, Larijani B, et al. Mortality Attributable to Excess Body Mass Index in Iran: Implementation of the Comparative Risk Assessment Methodology. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:107. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.169075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amouei A, Moosazadeh M, Sarvi S, Mizani A, Pourasghar M, Teshnizi SH, Hosseininejad Z, Dodangeh S, Pagheh A, Pourmand AH. Evolutionary puzzle of toxoplasma gondii with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020. 10.1111/tbed.13550. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Hsu PC, Groer M, Beckie T. New findings: depression, suicide, and toxoplasma gondii infection. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014;26(11):629–637. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carruthers VB, Suzuki Y. Effects of toxoplasma gondii infection on the brain. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):745–751. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flegr J. Effects of toxoplasma on human behavior. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(3):757–760. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller CM, Boulter NR, Ikin RJ, Smith NC. The immunobiology of the innate response to toxoplasma gondii. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39(1):23–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denkers EY, Gazzinelli RT. Regulation and function of T-cell-mediated immunity during toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(4):569–588. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(10):819–828. doi: 10.1038/nrn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sequeira A, Mamdani F, Ernst C, Vawter MP, Bunney WE, Lebel V, Rehal S, Klempan T, Gratton A, Benkelfat C. Global brain gene expression analysis links glutamatergic and GABAergic alterations to suicide and major depression. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suda A, Kawanishi C, Kishida I, Sato R, Yamada T, Nakagawa M, Hasegawa H, Kato D, Furuno T, Hirayasu Y. Dopamine D2 receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with suicide attempt in the Japanese population. Neuropsychobiology. 2009;59(2):130–134. doi: 10.1159/000213566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khabazghazvini B, Groer M, Fuchs D, Strassle P, Lapidus M, Sleemi A, Cabassa JB, Postolache TT. Psychiatric manifestations of latent toxoplasmosis. Potential mediation by indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2010;9(1):3–10. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author is responsible for data. Access to all relevant raw data will be free to any scientist.