As the coronavirus pandemic stresses medical infrastructures, innovative health care recruitment efforts are being challenged. From reinstating licenses of retired physicians and nurses to the early medical school graduation and residency start dates—policies are being enacted to meet demand shortages. Undoubtedly, health care providers at virus hot spots are short staffed, but is the demand equal among all specialties? Moreover, Is this pandemic an unprecedented learning opportunity for trainees, or can it actually be a detriment?

Every night at 8:00 PM the City of Chicago unites in support of medical professionals by flickering lights across the city skyline. Although I find this inspiring, I am a health care professional who feels undeserving of this tribute, having taken care of no coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients since early March. As a cardiothoracic surgical trainee, I represent one of many subspecialty residents whose daily work lives have drastically changed. Unlike the harrowing images from New York, Spain, and Italy, where providers are exhausted and risking their lives, my typical 80-hour work week has been slashed in half.

As part of an ever-evolving attempt to adjust our daily operations to the COVID-19 pandemic, the American College of Surgeons has recommended “…to minimize, postpone, or cancel electively scheduled operations… until we have passed the predicted inflection point in the exposure graph.”1 Similarly, on March 14, 2020, the US Surgeon General urged the following via Twitter: “Hospitals & healthcare systems, PLEASE CONSIDER STOPPING ELECTIVE PROCEDURES until we can #FlattenTheCurve!”2 As with many subspecialties, cardiothoracic surgery has followed suit.

Simultaneously, hospital administrators and board members are keenly watching the balance sheets, as elective surgeries and procedures are the lifeline of the hospital business. The longer elective cases wait, the longer each hospital bleeds funds.

Faced with a myriad COVID-19 patients, stressed administrators, frenzied accountants, and furloughed employees have suffered unintended consequences. Is there even room to consider others affected by this pandemic? Yes, the next generation of subspecialists whose future potentially depends on it! Resident subspecialty education and especially surgical education are coming to an unprecedented halt. From general surgery to cardiac surgery and all subspecialties—with no elective cases and procedures—there are fewer opportunities for medical education. When faced with strict case requirements for residency graduation and medical board eligibility, the question arises of how long we can weather this storm.

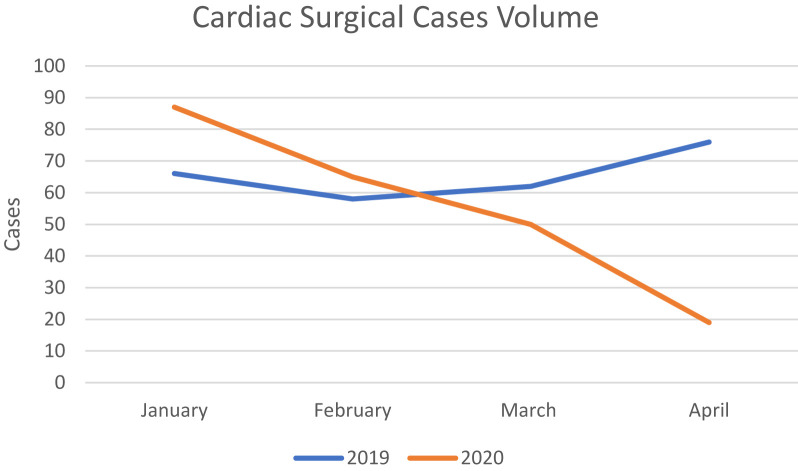

The number of elective cardiac cases at my institution decreased by 16% during the first quarter of 2020 compared with 2019. The true degree of decline is further illustrated with this staggering drop off: 31% more volume in January 2020, 12% more volume in February, but 20% fewer cases in March and 75% fewer cases in April. With municipal and state lockdown orders remaining in place through May in large sections of the country, hospital planning boards are still grappling with when to begin reintroducing elective surgeries. (Fig )

Fig.

Cardiac surgical cases volume.

But truly, how affected are subspecialty residents and trainees? In my fellowship, graduates vastly exceed the required structural valvular cases (aortic and mitral valve surgery), but only surpass the myocardial revascularization (coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) requirements by approximately 20%. Looking at my own record, with 1 more year of training to go, I have nearly double the valvular cases needed, but have just met the required CABG volume, with 84 of 80 required cases. Given the finite availability of operations, our program has typically prioritized first-year fellows performing bypass operations, second-year fellows performing valvular cases, and third-year fellows involved with the most complex cases. As such, I would typically pass off CABG cases to my junior counterparts and hence have limited access to them in the future–that 84 may not increase much more. Moreover, for trainees in the year below me, their number may not even cross the 80-case cutoff. If the hiatus in elective cases continues beyond this month, the buffer in required revascularization cases may well disappear, with future fellows at risk of missing their educational targets.

Surely, once operating rooms are reopened, there will be a spike in volume from postponed cases. But, for a surgical trainee with a limited time to meet the “numbers,” will this spike be enough? What percentage of postponed patients will have died from their disease, natural causes, or COVID-19? Will residents share cases altruistically based on each other’s needs? In line with the extreme uncertainty around COVID-19 today, we just do not know.

Subspecialty resident education is particularly susceptible to this training disruption. As peers, mentors, and educators, we need to diligently follow what the long-term effects that COVID-19 has on our education. We must be prepared to redefine resident and fellow training to overcome this challenge.

It would be prudent for specialty medical boards to ponder whether they would adjust certain graduation requirements in the upcoming year. Similarly, residency program directors must reckon with the possibility of multiple graduates being unable to meet benchmarks. Fortunately, the American Board of Medical Specialties and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education released a joint statement regarding physician training during the coronavirus pandemic.3 The principles invoked reaffirm the organizations’ commitment to supporting physician training, and allowing for creative and flexible ways to “to ensure that physicians practice medicine safely and efficaciously.” Furthermore, they assert that clinical competency committees and program directors are uniquely qualified to determine “readiness for unsupervised practice… especially important during times of crises when traditional time- and volume-based educational standards may be challenged.” As such, the potential curtailing of subspecialty education is already being recognized nationally. It is up to the discretion of individual programs to decide how to address this challenge and still guarantee subspecialists’ proficiency.

Subspecialty trainees remain eager to return to full clinical productivity and to caring for their patients. However, the true duration of this pandemic and its detriment on their education will only be understood with time. Despite this upheaval and its many unforeseen consequences, I remain confident that with forethought and adaptability all obstacles can be overcome to guarantee future generations of well-trained, skillful, and thoughtful subspecialists.

Funding/Support

The author has no funding source to report in regard to this editorial.

Conflict of interest/Disclosure

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose in regard to this editorial.

References

- 1.American College of Surgeons Web site COVID-19: Recommendations for Management of Elective Surgical Procedures. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-surgery Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 2.US Surgeon General Hospital & healthcare systems, PLEASE CONSIDER STOPPING ELECTIVE PROCEDURES until we can #FlattenTheCurve! Twitter. https://twitter.com/Surgeon_General/status/1238798972501852160 Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 3.ABMS and ACGME Joint Principles: Physician Training During the COVID-2019 Pandemic. https://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-and-acgme-joint-principles-physician-training-during-the-covid-2019-pandemic/. Accessed April 30, 2020.