Abstract

Sustained Ca2+ burst signaling is crucial for endothelial vasodilator production and is disrupted by growth factors and cytokines. Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a Src inhibitor in certain preparations, is generally regarded as safe during pregnancy by the FDA. Multiple CLA preparations; t10,c12 or c9,t11 CLA, or a 1:1 mixture of the two were administered before growth factor or cytokine treatment. Growth factors and cytokines caused a significant decrease in Ca2+ burst numbers in response to ATP stimulation. Both t10,c12 CLA and the 1:1 mixture rescued VEGF165 or TNFα inhibited Ca2+ bursts and correlated with Src-specific phosphorylation of connexin 43. VEGF165, TNFα, and IL-6 in combination at physiologic concentrations revealed IL-6 amplified the inhibitory effects of lower dose of VEGF165 and TNFα. Again, the 1:1 CLA mixture was most effective at rescue of function. Therefore, CLA formulations may be a promising treatment for endothelial dysfunction in diseases such as preeclampsia.

Keywords: Ca2+, conjugated linoleic acid, cytokine, growth factor, preeclampsia

1. INTRODUCTION

The vascular endothelium is responsible for sensing blood borne signals and maintenance of homeostasis in the cardiovascular system. Endothelial dysfunction is characterized in part by a reduction in vasodilator production and a shift towards a proinflammatory profile, and can be caused by local and systemic changes in the growth factor and cytokine environment (Visser, van Rijn, Rijkers et al., 2007,Saito, Shiozaki, Nakashima et al., 2007). There are a variety of diseases in which endothelial dysfunction plays a role, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, chronic kidney failure, and preeclampsia (PE) (Rajendran, Rengarajan, Thangavel et al., 2013,Boeldt and Bird, 2017). Despite the widespread acknowledgment of the important role endothelial dysfunction plays in such disorders, therapeutic targeting of the endothelium remains underutilized.

Endothelial intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+ ]i) is an important determinant of vasodilator production (Tran, Leonard, Black et al., 2009). Such elevations in [Ca2+]i often take the form of periodic Ca2+ bursts, which correlate directly with vasodilator production (Yi, Boeldt, Gifford et al., 2010,Yi, Magness and Bird, 2005, Krupp, Boeldt, Yi et al., 2013). Ca2+ bursting is dependent on functionally coupled Cx43 gap junctions (Yi et al., 2010,Boeldt, Grummer, Yi et al., 2015,Boeldt, Krupp, Yi et al., 2017). Cx43 gap junctions facilitate communication between adjacent cells through the passage of small molecules and ions, such as IP3 and likely Ca2+ (Bird, Boeldt, Krupp et al., 2013,Solan and Lampe, 2009). The function of Cx43 gap junctions is highly influenced by growth factor and cytokine mediated kinase activation. Src activation results in direct phosphorylation of Cx43 at the inhibitory Y265 residue (Solan and Lampe, 2014). Phosphorylation of Y265 promotes downregulation of Cx43-mediated communication, most likely by destabilizing the Cx43 plaques and increasing the rate of protein turnover (Solan and Lampe, 2014). Because sustained endothelial Ca2+ signaling depends on functionally coupled Cx43 gap junctions, the net result of increased Y265 phosphorylation is reduced Ca2+ signaling capacity (Boeldt et al., 2015,Ampey, Boeldt, Clemente et al., 2019).

Previous studies have shown that exposure of intact endothelium to 10ng/ml VEGF165 reduces ATP-stimulated Ca2+/nitric oxide (NO) production to a level that is not compensated for by the Ca2+/NO production attributable to VEGF165 itself (Boeldt et al., 2017,Yi, Boeldt, Magness et al., 2011). Many of the growth factors and cytokines that may mediate endothelial dysfunction can be sorted into groups/classes based on how their receptors couple directly (VEGF165, bFGF, EGF, TNFα) (D’Angelo, Struman, Martial et al., 1995,Deo, Axelrad, Robert et al., 2002,Eliceiri, Paul, Schwartzberg et al., 1999,Huang, Dudez, Scerri et al., 2003,Nwariaku, Liu, Zhu et al., 2002,Parenti, Morbidelli, Cui et al., 1998,Tang, Yang, Chen et al., 2007,Waltenberger, Claesson-Welsh, Siegbahn et al., 1994) or indirectly (IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β) (Huang, Yang, Hsu et al., 2013,Liu, Kuo, Wang et al., 2016) to the same common post receptor kinase pathways. However, the literature has widely failed to address the effects of these growth factors and cytokines when used in combination, as they exist in pathophysiologic context, instead of individually. Therefore, there is a need to construct “cocktails” utilizing multiple growth factors and cytokines to bridge the gap from single agonist experiments to experimental conditions that are more representative of the in-vivo environment of endothelial dysfunction. Co-stimulation with multiple growth factors and cytokines may be dependent on an unappreciated signaling hierarchy, and because these kinases may present a common pathway for endocrine-mediated endothelial dysfunction, they may be a prime target for therapeutic intervention (Bird et al., 2013).

In this study, we use human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) to model the combined actions of these growth factors and cytokines on endothelial cell function. We use PE as a model system to construct our cocktails as it has been described as a condition of cytokine-mediated endothelial dysfunction (Redman, Sacks and Sargent, 1999). As appropriate levels of growth factors and cytokines are necessary to support normal pregnancy, we also use a cocktail representative of normal pregnancy as a control. For this study we include TNFα, IL-6 and VEGF in our cocktails, using doses attributed to ‘normal’ and PE pregnancies for TNFα and IL-6 (Lau, Guild, Barrett et al., 2013,Tosun, Celik, Avci et al., 2010,Xie, Yao, Liu et al., 2011), and varied doses of VEGF165 to mimic systemic and local concentrations. While PE is used as the model for which we construct our dysfunctional phenotype, the resulting findings will likely apply to a broad range of diseases that have an endothelial dysfunction component.

The pharmacological Src inhibitor PP2 has already proven successful in rescuing VEGF165 and TNFα pretreated endothelium from a dysfunctional Ca2+ signaling phenotype to one more congruent with normal function (Boeldt et al., 2015,Ampey et al., 2019). A pharmacological tool like PP2 is not used in humans due to significant toxicity and concerns of teratogenicity in pregnancy, and therefore offers no therapeutic value. A pair of isomers of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) used at FDA recommended doses for treatment of inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and hypertension may hold promise as a safe method for Src inhibition, even in pregnancy. The t10,c12 CLA isomer has been shown to be a Src inhibitor in cancer cells (Shahzad, Felder, Ludwig et al., 2018). When used in ovine endothelial cells, VEGF165-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ responses were rescued with as little as 5um t10,c12 CLA, and 50uM t10,c12 CLA rescued TNFα-mediated Ca2+ response inhibition (Boeldt et al., 2015,Ampey et al., 2019). Herein, we examine the efficacy of individual c9,t11 and t10,c12 isomers, as well as a 1:1 mix to rescue Cx43-dependent Ca2+ signaling in HUVEC pretreated with individual growth factors or cytokines. We also examine the effect of combinations of a selection of growth factors and cytokines on Ca2+ signaling and the ability of CLA isomers alone or as a 1:1 mix, to restore function to the normal phenotype.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

ATP (disodium salt), Heparin sodium salt and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma- Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated. Growth factors and cytokines (bFGF, EGF, VEGF165, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) were purchased from R & D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Glass bottom microwell dishes for Ca2+ imaging studies were from MatTek Corporation (Ashland, MA, USA). Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) was purchased from Invitrogen (Life Technologies Inc., Grand Island, NY). Serum used in culture medium was fetal bovine serum (FBS) from Invitrogen and Endothelial Cell Growth Supplement ECGS was from Millipore (Temecula, CA). Experimental buffer was Krebs buffer (125mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 Mm KH2PO4, 6 mM glucose, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). The growth medium is referred in this article as HEH medium (Human, ECGS, Heparin) and is as described in (Krupp et al., 2013). PP2 is from Sigma- Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and t10,c12 CLA and c9,t11 CLA are from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA, USA).

2.2. Primary Cell Culture

Institutional review board (IRB) was approved from University of Wisconsin School of medicine and public health. HUVEC were isolated from fresh umbilical cords after informed consent from patients that delivered via elective Cesarean section with intact membranes and no evidence of labor or infection. Cords obtained were put into cold (4 C) PBS solution and were ready for cell harvest within 30 minutes from the delivery of the placenta. Complete methods of harvesting and storing of HUVECs has been described elsewhere in detail (Krupp et al., 2013). HUVECs were pooled from 5 subjects at passage 3 and then used for experimentation and data analysis. Patient information can be found in Krupp et al (Krupp et al., 2013).

2.3. Cell growth and Ca2+ imaging

HUVECs (passage 4) were grown to confluence in 35 mm, glass-bottom microwell dishes, and handled as described in (Krupp et al., 2013,Boeldt et al., 2015,Boeldt et al., 2017). HUVECs were incubated with 10uM Fura2-AM (Molecular Probes) with 0.05% Pluronic acid F127 (Life Technologies) in HEH for 1 hour at 37°C. HUVECs were washed with Krebs buffer following incubation and HUVECs were left in Krebs buffer for 30 minutes at room temperature, allowing for complete ester hydrolysis. The dish was then placed on a Nikon inverted microscope (Diaphot 150; Nikon, Melville, NY) for imaging. Up to 99 cells per field of view were identified and manually circled for analysis (Krupp et al., 2013). After 5 minutes baseline recording, HUVECs were stimulated by 100 uM ATP (ATP exposure 1) and recorded for a total of 30 minutes using alternate excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm at 1 second intervals. Number of cells that had ≥3 bursts were noted and calculated. Cells were then washed three times with Kreb’s buffer for 20 minutes to bring cells to baseline for further imaging steps (A and B below). A standard curve was used to calculate concentration of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i).

For the effect of growth factors and cytokines on ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts, cells were exposed to 10ng/ml VEGF165, bFGF, EGF, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, or combinations thereof for 30 minutes (except TNFα − 60 minutes) and 100uM ATP was subsequently added for an additional 30 minutes (ATP exposure 2). The number of Ca2+ bursts during the second ATP exposure were noted and compared to the number of Ca2+ bursts from the initial exposure.

For recovery of ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts with CLA, 10 or 50 uM t10,c12 CLA or c9,t11 CLA (30 minutes) were added to the dish during the wash step. This was followed by treatment with growth factor or cytokine for the required time, and then ATP as in step A.

2.4. Western Blot Analysis

HUVEC were grown to 100% confluence on 60mm dishes before 4-hour serum withdrawal. Cells were then pretreated with t12,c12 CLA (50uM), c9,t11 CLA (50uM), or a 1:1 Mix of both isomers (10uM) before 10ng/ml TNFα (1 hour) or 10ng/ml VEGF165 (30minutes) application. Media was quickly aspirated and cells were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, harvested, lysed, and loaded on 7.5% gels for SDS-PAGE at 20ug protein/well exactly as previously published (Boeldt et al., 2015,Grummer, Sullivan, Magness et al., 2009,Sullivan, Grummer, Yi et al., 2006). Phosphorylation of Cx43 was detected using an antibody to Tyr-265 Cx43 (#sc-17220-R; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:667. Secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated (#7074, Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:3000. Loading control was Hsp90 (#4874, Cell Signaling Technology) at 1:2500.

2.5. Statistical analysis

For imaging, each agonist was administered in 4–6 dishes with each dish marking 90–95 cells. Burst numbers in each cell were counted, the difference from internal control was taken, and this difference is what was used for data analysis and creation of figures. Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used for statistical analysis. For Western Blot Analysis, a minimum of 6 independent experiments were run for each agonist, and statistical analysis was performed by post-hoc Tukey HSD one-way ANOVA with Holm interference. Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. and P ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Linear regression analyses were presented with 95% confidence intervals.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effect of Individual Growth Factors and Cytokines on Ca2+ Bursts and CLA Rescue

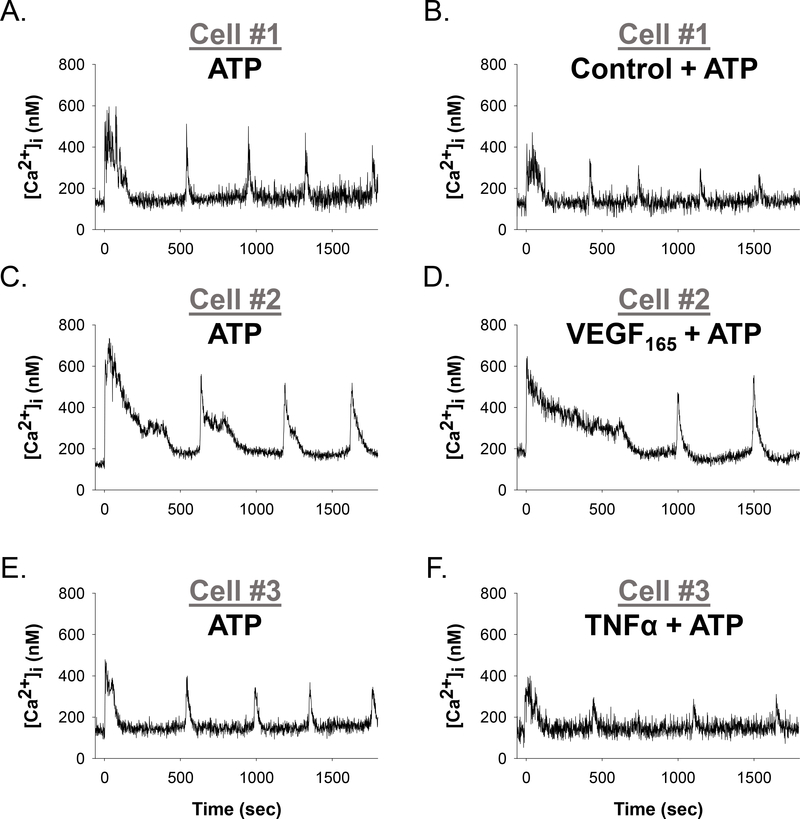

Representative single cell tracings from Fura-2 loaded HUVECs are shown in Figure 1. A short baseline precedes 100uM ATP stimulation at 0 seconds. Upon stimulation, an immediate initial Ca2+ peak is seen followed by multiple transient Ca2+ bursts over the duration of the 30-minute experiment. Figures 1A–F shows individual ATP-stimulated cells before and after a pretreatment with Krebs buffer control (top panels A, B), 10ng/ml VEGF165 (middle panels C, D), or 10ng/ml TNFα (bottom panels E, F). Cells were selected as representative of the mean number of Ca2+ bursts observed for each condition. A reduction in Ca2+ burst numbers was observed for the cells treated with VEGF165 and TNFα, but not for control cells.

Figure 1: Representative individual HUVEC Ca2+ tracings before and after Control,VEGF165, or TNFα treatment.

Panels A, C, and E show representative HUVEC ([Ca2+ ]i) tracings with a short baseline followed by 100uM ATP stimulation (at time 0 sec), resulting in initial ([Ca2+ ]i) peak followed by repetitive Ca2+ bursts. Panel B shows the same cell as panel A, with addition of a vehicle control for 30 minutes and subsequently stimulated with ATP (at time 0 sec). Panel D shows the same cell as Panel C, with the addition of 10ng/ml VEGF165 for 30 minutes before subsequent stimulation with ATP (at time 0 sec). Likewise, Panel F shows the same cell as in Panel E, with the addition of 10ng/ml TNFα for 60 minutes before subsequent stimulation with ATP (at time 0 sec). Ca2+ The resulting Ca2+ burst loss provides an in vitro functional assay for growth factor and cytokine-mediated endothelial dysfunction as seen in PE. For Panel A to Panel B, zero burst loss; for Panel C to Panel D, 1 burst loss − 25% reduction; for Panel E to Panel F, 1 burst loss − 20% reduction.

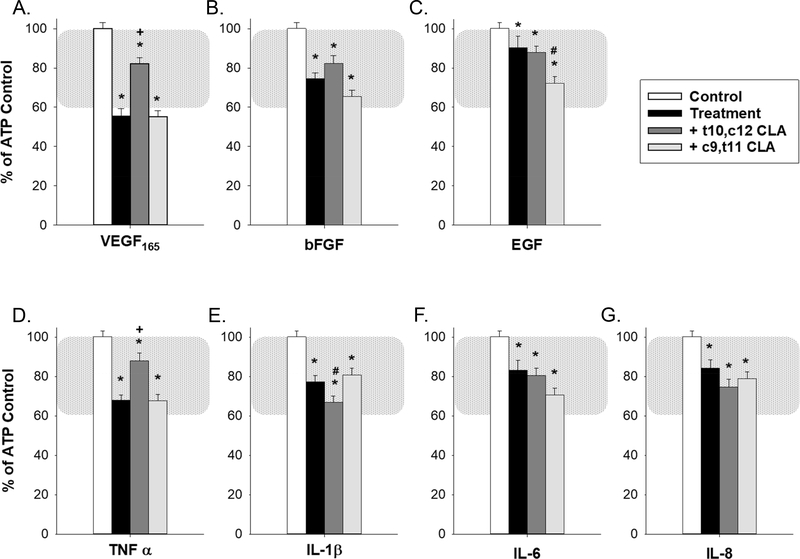

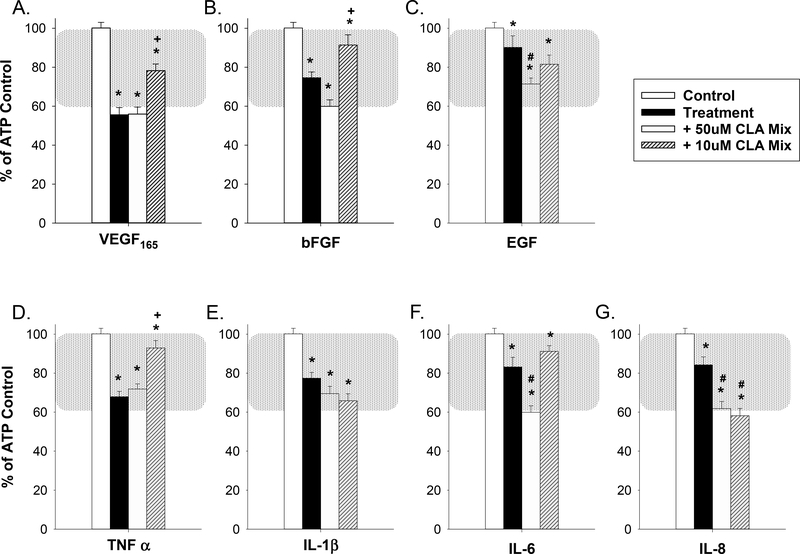

Figure 2 shows the quantification of the loss of ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts in HUVECs with growth factor or cytokine treatments (ATP control - white bars; growth factor or cytokine treatment - black bars). These treatments were compared with control (defined as HUVEC cells stimulated with 100uM ATP followed by Krebs wash and ATP stimulation again to rule out intrinsic Ca2+ burst loss). The physiologic functional range, as defined previously in uterine artery endothelium and calibrated to the HUVEC model here by TPA treatment (Boeldt et al., 2017,Bird et al., 2013) is highlighted by the shaded region. In the absence of a non-pregnant control for HUVEC studies, we have previously established that the use of 1nM TPA produces a 60% reduction in Ca2+ bursting that parallels results from the non-pregnant ovine model, serving as a value that can represent pregnancy adapted function (Boeldt et al., 2017,Bird et al., 2013). This emphasizes that a relatively small difference in Ca2+ burst numbers of ~40% can span the entire range of pregnancy-adapted function, and can likely be applied equally to other vascular beds. While cells show significant (p≤ 0.05) loss of Ca2+ bursts with all growth factors or cytokines that were used, VEGF165 (panel A) and TNFα (panel D) were the most potent Ca2+ burst inhibitors (55% and 70% of control bursting respectively, p≤ 0.001). Other treatments also showed a loss of Ca2+ bursts, with the smallest loss observed (e.g. EGF (panel C), IL-6 (panel F), IL-8 (panel G)) at 80–90% of control Ca2+ bursts, still achieving statistical significance.

Figure 2: Growth factor and cytokine pretreatment inhibits ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts and is partially reversed by t10,c12 CLA for VEGF165 and TNFα.

Pretreatment with each of seven growth factors and cytokines used at 10ng/ml for 30 minutes (VEGF165 (panel A), bFGF (panel B), EGF (panel C), TNFα (panel D, 60 minutes), IL-1β (panel E), IL-6 (panel F), and IL-8 (panel G)) inhibit ATP stimulated Ca2+ bursts in confluent HUVEC. Treatment with 50uM c9,t11 CLA for 30 minutes prior to growth factor or cytokine addition failed to reverse Ca2+ burst inhibition for any treatment and significantly exacerbated ATP-stimulated Ca2+ burst inhibition for EGF. Similar treatment with 50uM t10,c12 CLA partially reversed VEGF165 and TNFα-mediated inhibition of ATP-stimulated Ca2+ responses and exacerbated ATP-stimulated Ca2+ burst inhibition for IL-1β. Data is presented as mean Ca2+ burst numbers for those cells that showed 3+ bursts on initial ATP treatment ± SEM on a minimum of 75 cells from at least 4 separate dishes. Significance by Rank-sum test is indicated as p<0.05 for * Control vs Treatment (w/ or w/o CLA); + Significant improvement after CLA pretreatment vs Treatment; # Significant exacerbation of Ca2+ burst inhibition by CLA pretreatment vs Treatment. Typical physiological range is shown with shaded region as defined in (Boeldt et al., 2017,Bird et al., 2013), adjusted to HUVEC.

HUVEC were also pretreated with two common CLA isomers prior to growth factor or cytokine treatment and subsequent 30-minute 100uM ATP stimulation (Figure 2). In initial studies, cells were exposed to 50uM of either c9,t11 CLA (non-Src inhibiting isomer (Shahzad et al., 2018)) or t10,c12 CLA (Src inhibiting isomer (Shahzad et al., 2018)) in order to assess the effect each may have individually on growth factor or cytokine-mediated inhibition of ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts. Pretreatment with c9,t11 CLA showed no capability in improving ATP-stimulated Ca2+ burst responses during treatment with any of the seven growth factors or cytokines used in this study. In the case of EGF (panel C), treatment with c9,t11 CLA exacerbated the growth factor or cytokine-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ bursts. However, when treated with the Src inhibiting t10,c12 CLA isomer, improvement in ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts was observed for VEGF165 (panel A) and TNFα (panel D). Only in the case of IL-1β (panel E) was any further reduction in ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts observed. Cells exposed to 50uM c9,t11 CLA with no growth factor or cytokine produced 80.5% (± 4.4%) as many Ca2+ bursts compared to internal ATP control. Likewise, treatment with 50uM t10,c12 CLA alone produced 88.9% (± 4.6%) of internal control Ca2+ bursts (also see Figure 7).

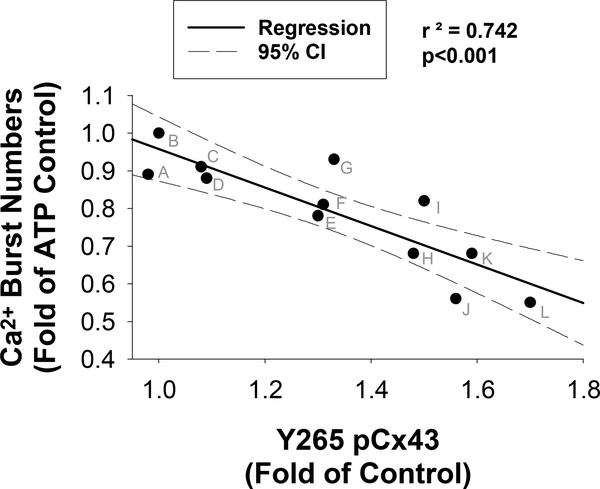

Figure 7: Regression Analysis of Ca2+ Burst and phospho-Cx43 for VEGF165, TNFα, and CLA isomers.

Mean Ca2+ Burst numbers as fold of ATP control (from figures 2 and 4) on the X-axis and mean Y265 phosphor-Cx43 western blot data as fold of control (from figure 6) are plotted. A linear regression with 95% confidence intervals reveal a significant negative correlation between ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts and Y265 phosphorylation (p<0.001). Treatments consisted of the following (indicated by letters above according to mean Y265 phosphorylation); A: 50uM t10,c12 CLA; B: Control; C: 10uM CLA mix; D: TNFα + 50uM t10,c12 CLA; E: VEGF165 + 10uM CLA Mix; F: 50uM c9,t11 CLA; G: TNFα + 10uM CLA Mix; H: TNFα; I: VEGF165 + 50uM t10,c12 CLA; J: VEGF165; K: TNFα + 50uM c9,t11 CLA; L: VEGF165 + 50uM c9,t11 CLA.

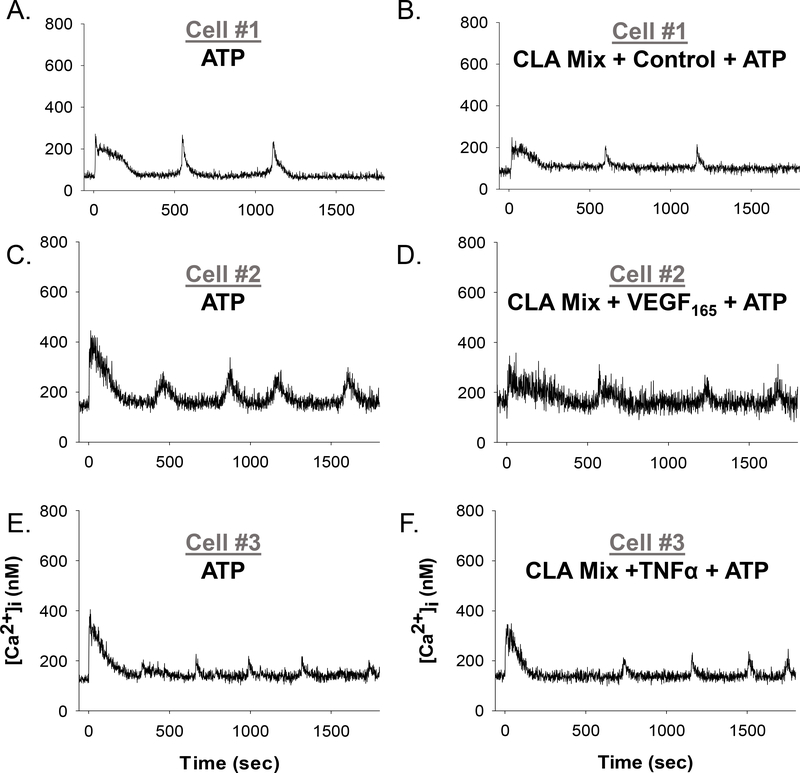

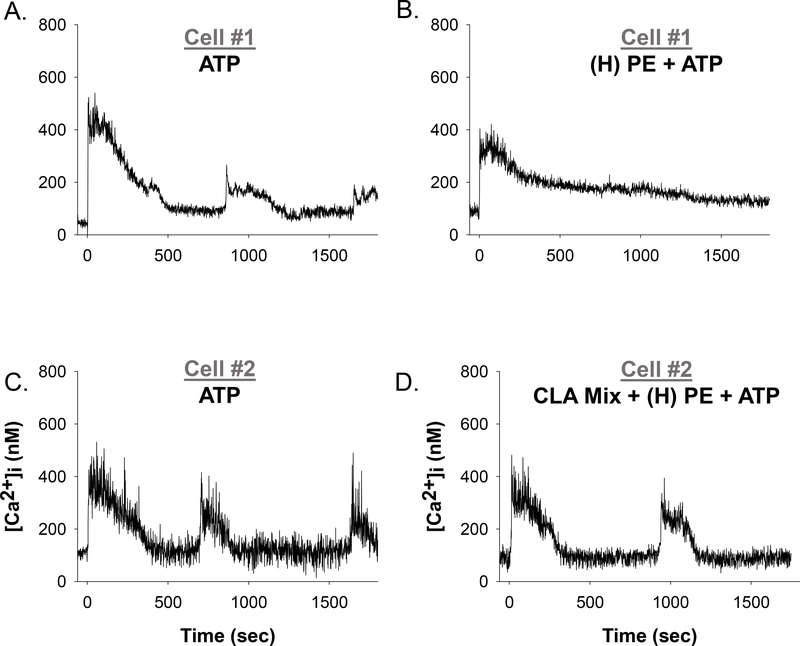

Because commercially available and FDA-approved formulations of CLA specify mixtures of CLA isomers, we included in our studies a 1:1 mix of c9,t11 and t10,c12 CLA as a Ca2+ burst recovery agent. Representative single-cell tracings for rescued Ca2+ bursting function for 10uM CLA Mix pretreatment with VEGF165 and TNFα are shown in Figure 3, and quantification is shown in Figure 4. After a 30 minute pretreatment with a mixture of 50uM c9,t11 CLA and 50uM t10,c12 CLA, no positive effect on growth factor or cytokine inhibited Ca2+ bursts was observed. Significantly impaired Ca2+ burst responses were observed in response to EGF (panel 4C), IL-6 (panel 4F), and IL-8 (panel 4G). When the doses of c9,t11 and t10,c12 CLA were dropped to 10uM each, the 30-minute pretreatment was more effective in yielding a significant improvement for VEGF165 (panel 4A), bFGF (panel 4B), and TNFα (panel 4C). The only exception was that further impairment was observed in the presence of IL-8 (panel 4G). Cells exposed to 50uM CLA mix with no growth factor or cytokine produced 68.9% (± 5.2%) as many Ca2+ bursts compared to internal ATP control. Ca2+ Treatment with 10uM CLA mix alone produced 91.0% (± 6.5%) of internal control Ca2+ bursts (also see Figure 7).

Figure 3: Representative individual HUVEC Ca2+ tracings before and after CLA Mix pretreatment and Control, VEGF165, or TNFα treatment.

Panels A, C, and E show representative HUVEC ([Ca2+ ]i) tracings with a short baseline followed by 100uM ATP stimulation (at time 0 sec), resulting in initial ([Ca2+ ]i) peak followed by repetitive Ca2+ bursts. Panel B shows the same cell as panel A, with addition of a 10um CLA mix pretreatment for 30 minutes before vehicle control treatment for 30 minutes and subsequently stimulated with ATP (at time 0 sec). Panel D shows the same cell as Panel C, with the addition of 10um CLA mix pretreatment for 30 minutes before 10ng/ml VEGF165 for 30 minutes and subsequent stimulation with ATP (at time 0 sec). Likewise, Panel F shows the same cell as in Panel E, with the addition of 10um CLA mix pretreatment for 30 minutes before 10ng/ml TNFα for 60 minutes and subsequent stimulation with ATP (at time 0 sec). An improvement in the degree of lost bursting as seen in Figure 1 established CLA-mediated rescue of Ca2+ bursting function.

Figure 4: Inhibition of ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts is partially rescued by a 10uM 1:1 mix of c9,t11 and t10,c12 CLA isomers for VEGF165, TNFα, and bFGF.

Confluent HUVEC were pre-exposed to a 1:1 mix of either 50uM c9,t11 CLA and 50uM t10,c12 CLA or 10uM c9,t11 CLA and 10uM t10,c12 CLA for 30 minutes before growth factor or cytokine treatment and subsequent 100uM ATP treatment. ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts remained significantly reduced compared to control for all CLA-exposed treatments. The 50uM CLA mix failed to improve ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts for any growth factor or cytokine and exacerbated the Ca2+ burst inhibition for EGF (panel C), IL-6 (panel F), and IL-8 (panel G). The 10uM CLA mix significantly improved ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts for VEGF165 (panel A), bFGF (panel B), and TNFα (panel D). The 10uM CLA mix exacerbated Ca2+ burst loss for IL-1β (panel E) and IL-8 (panel G). Data is presented as mean Ca2+ burst numbers for those cells that showed 3+ bursts on initial ATP treatment ± SEM on a minimum of 75 cells from at least 4 separate dishes. Significance by Rank- sum test is indicated as p<0.05 for * Control vs Treatment (w/ or w/o CLA); + Significant improvement after CLA pretreatment vs Treatment; # Significant exacerbation of Ca2+ burst inhibition by CLA pretreatment vs Treatment. Typical physiological range is shown with shaded region as defined in (Boeldt et al., 2017,Bird et al., 2013), adjusted to HUVEC.

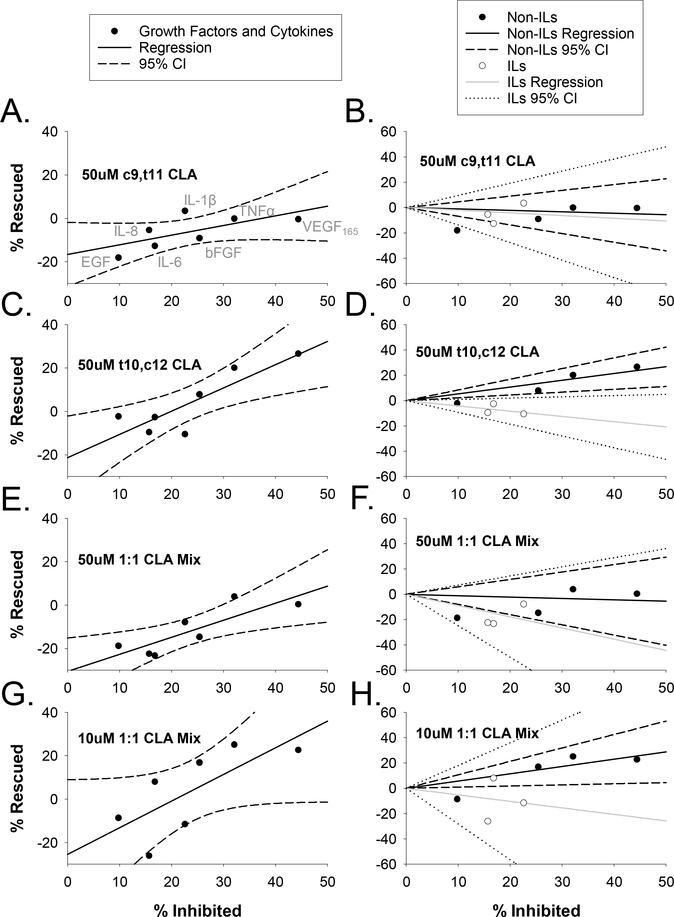

To better understand the relationship between degree of inhibition and degree of CLA effect or “rescue”, we applied two regression analyses (Figure 5) to each treatment group from Figures 2 and 4. When all growth factors and cytokines are pooled together (left panels A, C, E, G), there is a positive relationship between degree of inhibition and degree of rescue (i.e. those growth factors and cytokines which are the most inhibitory are the most rescued by CLA treatments) for each CLA treatment group. However, when we separated the interleukins that are not coupled directly to Src from the non-interleukin growth factors and cytokines that do couple directly to Src, another trend was apparent (panels B, D, F, H). For those CLA treatments which were mostly ineffective (50uM c9,t11 CLA (panel B) and 50uM 1:1 CLA mix (panel F), there was no clear trend in how inhibition correlated with rescue. But for the more effective treatments (50uM t10,c12 CLA (panel D) and 10uM 1:1 CLA Mix (panel H) the growth factors VEGF165, bFGF as well as TNFα showed a positive relationship between inhibition and rescue, while interleukins showed a weaker negative relationship between inhibition and rescue.

Figure 5: Regression analysis for the effect of CLA treatments on individual growth factors and cytokines.

Linear regressions were executed with percentage of bursts inhibited plotted on the x-axis and percentage “rescued” indicating change in burst numbers for all CLA and growth factor treatments from Figures 2 and 4 plotted on the y-axis. Experimental conditions are matched left (all data together; panels A,C,E,G) and right (separated into non-interleukins (Non-ILs) and Interleukins (ILs); panels B,D,F,H). All data points correspond to the same growth factors and cytokines from L to R: EGF, IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β, bFGF, TNFα, and VEGF165; as indicated in the upper left panel. For the left panels (A,C,E,G), regression lines are indicated by a solid black line and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are indicated by dashed black lines. For panels to the right (B,D,F,H), Non-ILs are indicated by black circles, black regression line, and black dashed CIs; for left panels, ILs are indicated by open circles, gray regression line, and dotted CIs.

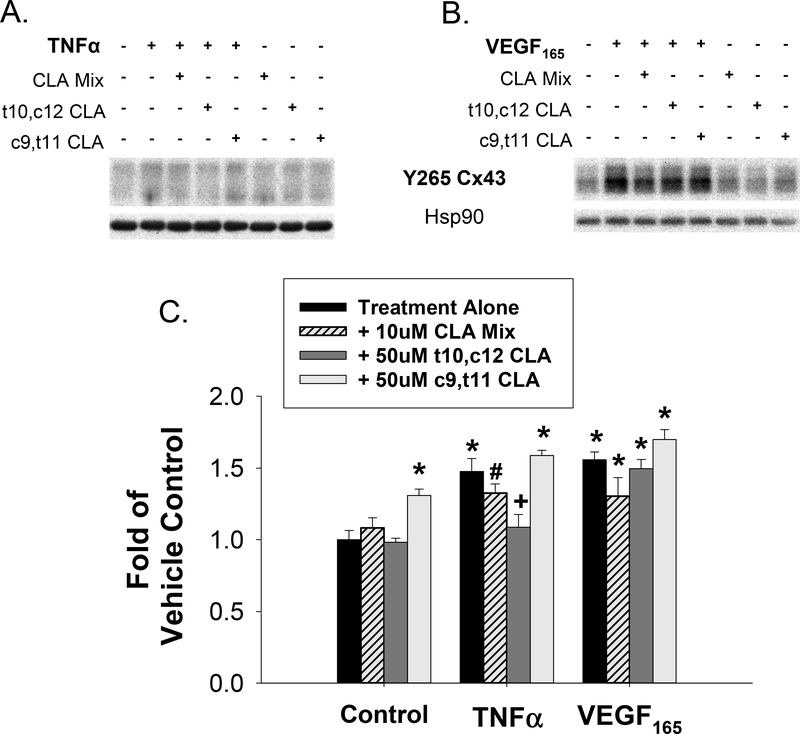

In order to assess the effect of t10,c12 CLA on Src-mediated phosphorylation of Cx43, we performed phospho-specific western blots for HUVEC stimulated with VEGF165 or TNFα. In Figure 6A and 6B, representative blots at the 43kD band are shown along with Hsp90 loading control. It should be noted that Y265 antibody binds rather weakly and as a result often gives blots that look quite variable before normalization and background correction. In Figure 6C, quantification of phosphorylation of the Src-sensitive Y265 site on Cx43 was increased by VEGF165, TNFα, or 50uM c9,t11 CLA treatment. Phosphorylation of Y265 by TNFα was significantly reversed by 50uM t10,c12 CLA. Further validation of Src specificity of the Y265 site on Cx43 is shown by PP2 inhibition of phospho-Y265 under control and TNFα-stimulated conditions (Supplementary Figure 1). In Figure 7, we further analyzed the Y265 phosphorylation data by regression analysis of Ca2+ burst numbers versus Y265 phosphorylation. This plot showed a significant correlation between Y265 phosphorylation and ATP-stimulated Ca2+ burst responses when both VEGF165 and TNFα data were pooled, indicating that Src-mediated Cx43 phosphorylation at Y265 is related to decreased Ca2+ burst ‘ numbers and is sensitive to CLA treatment.

Figure 6: TNFα and VEGF165 promote phosphorylation of Cx43 at residue Y265 and TNFα stimulated phosphorylation is reversed by t10,c12 CLA.

Phospho- specific western blot analysis for Y265 on Cx43 were done and representative blots are shown. HUVEC were pretreated with CLA isomers or a 1:1 mix for 30 minutes prior to TNFα (1 hr, panel A) or VEGF165 (30 min, panel B) stimulation. Each band was normalized to Hsp90 loading control and expressed as fold of unstimulated control. In panel C, values are depicted as mean ± S.E.M. with a minimum of 6 independent experiments. Statistical significance is indicated by * p<0.01 vs unstimulated control, # p<0.05 vs unstimulated control, and + p<0.01 vs treatment alone by post-hoc Turkey HSD one-way ANOVA with Holm interference.

3.2. Effect of Growth Factor and Cytokine Cocktails on Ca2+ Bursts and CLA Rescue

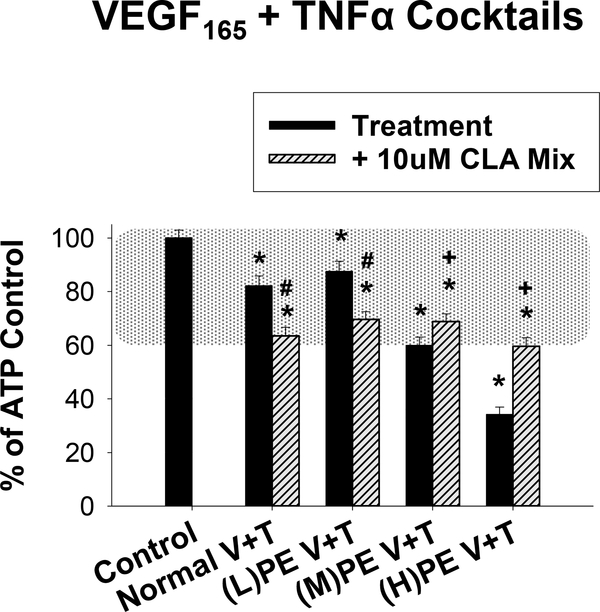

In order to model more physiologically relevant combinations of growth factors and cytokines in normal pregnancy and PE, we exposed HUVEC to cocktails (Normal or PE) of VEGF165 and TNFα, with or without IL-6 for 30 minutes. Figure 8 illustrates representative single-cell tracings of the reduction in Ca2+ bursting due to VEGF165, TNFα, and IL-6 cocktail exposure and the improvements achieved with 10uM CLA Mix. In Figure 9, we quantify the change in Ca2+ burst responses for the VEGF165 and TNFα only cocktails. Doses corresponding to normal pregnancy were 0.5ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.03ng/ml TNFα. For modeling PE pregnancies, we created three cocktails with varying concentrations of VEGF165. Concentrations for (L)PE V+T were 0.1ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.5ng/ml TNFα, for (M)PE V+T were 1 ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.5ng/ml TNFα, and for (H)PE V+T were 10ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.5ng/ml TNFα. The Normal V+T cocktail was moderately inhibitory and the 10uM CLA mix further inhibited the ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts. The PE V+T cocktails all inhibited ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts, in a VEGF165 dose dependent manner. Pretreatment with the 10uM CLA mix for 30 minutes exacerbated the (L)PE V+T mediated Ca2+ burst inhibition, but significantly improved ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts after (M)PE V+T and (H)PE V+T treatment.

Figure 8: Representative individual HUVEC Ca2+ tracings before and after (H) PE cocktail treatment and in combinations with CLA Mix pretreatment.

Panels A and C show representative HUVEC ([Ca2+ ]i) tracings with a short baseline followed by 100uM ATP stimulation (at time 0 sec), resulting in initial ([Ca2+]i) peak followed by repetitive Ca2+ bursts. Panel B shows the same cell as panel A, with addition of (H)PE cocktail treatment for 30 minutes and subsequently stimulated with ATP (at time 0 sec). Panel D shows the same cell as Panel C, with the addition of 10um CLA mix pretreatment for 30 minutes before (H)PE cocktail treatment for 30 minutes and subsequent stimulation with ATP (at time 0 sec).

Figure 9: The 10uM CLA mix rescues ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts only under Medium and High levels of VEGF165 and TNFα.

Normal pregnancy (30 minutes 0.5ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.03ng/ml TNFα) and PE-mimicking combination pretreatments (30 minutes) of varying doses of VEGF165 and a single dose of TNFα ((L)PE V+T: 0.1ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.5ng/ml TNFα; (M)PE V+T: 1ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.5ng/ml TNFα; (H)PE V+T: 10ng/ml VEGF165 and 0.5ng/ml TNFα) inhibited ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts in a dose-dependent manner. A 30 minute pretreatment with the 10uM 1:1 mix of CLA isomers exacerbated the inhibition due to the Normal V+T, (L)PE V+T combination, but rescued ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts for the (M)PE V+T and (H)PE V+T combinations. Data is presented as mean Ca2+ burst numbers for those cells that showed 3+ bursts on initial ATP treatment ± SEM on a minimum of 75 cells from at least 4 separate dishes. Significance by Rank-sum test is indicated as p<0.05 for * Control vs Treatment (w/ or w/o CLA); + Significant improvement after CLA pretreatment vs Treatment; # Significant exacerbation of Ca2+ burst inhibition by CLA pretreatment vs Treatment. Typical physiological range is shown with shaded region as defined in (Boeldt et al., 2017,Bird et al., 2013), adjusted to HUVEC.

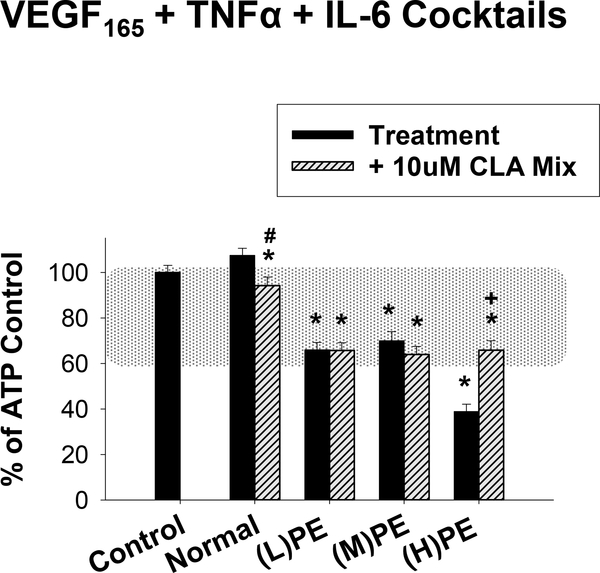

In Figure 10, we added IL-6 to the V+T cocktails from Figure 9 and again pretreated for 30 minutes. The Normal cocktail thus contained 0.5ng/ml VEGF165, 0.03ng/ml TNFα, and 0.1ng/ml IL-6. The (L)PE cocktail contained 0.1ng/ml VEGF165, 0.5ng/ml TNFα, and 3ng/ml IL-6. The (M)PE cocktail contained 1ng/ml VEGF165, 0.5ng/ml TNFα, and 3ng/ml IL-6. Finally, the (H)PE cocktail contained 10ng/ml VEGF165, 0.5ng/ml TNFα, and 3ng/ml IL-6. The Normal cocktail had no significant effect on ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts, but the addition of the 10uM CLA Mix had a small inhibitory effect. All three PE cocktails were quite inhibitory to ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts, and only in the presence of the (H)PE cocktail was the 10uM CLA Mix more effective in improving Ca2+ bursts.

Figure 10: Preeclamptic-like cytokine cocktails strongly inhibit ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts and are partially rescued by CLA in the high VEGF165 condition.

Cocktails corresponding to Normal (0.5ng/ml VEGF165, 0.03ng/ml TNFα, 0.1ng/ml IL-6) or PE ((L)PE: 0.1ng/ml VEGF165, 0.5ng/ml TNFα, 3ng/ml IL-6; (M)PE: 1ng/ml VEGF165, 0.5ng/ml TNFα, 3ng/ml IL-6; (H)PE: 10ng/ml VEGF165, 0.5ng/ml TNFα, 3ng/ml IL-6) circulating concentrations were applied to HUVEC. Cells exposed to the Normal cocktail were unchanged in number of ATP-stimulated Ca2+ bursts, and 30 minutes pretreatment with the 10uM CLA mix showed a slight reduction in Ca2+ bursts. Cells exposed to (L)PE and (M)PE cocktails showed modest levels of ATP-stimulated Ca2+ burst inhibition which were unchanged by CLA pretreatment. Exposure to the (H)PE cocktail gave severe Ca2+ burst inhibition, which was partially rescued using the 10uM 1:1 CLA mix. Data are presented as mean Ca2+ burst numbers for those cells that showed 3+ bursts on initial ATP treatment ± SEM on a minimum of 75 cells from at least 4 separate dishes. Significance by Rank-sum test is indicated as p<0.05 for * Control vs Treatment (w/ or w/o CLA); + Significant improvement after CLA pretreatment vs Treatment; # Significant exacerbation of Ca2+ burst inhibition by CLA pretreatment vs Treatment. Typical physiological range is shown with shaded region as defined in (Boeldt et al., 2017,Bird et al., 2013), adjusted to HUVEC.

4. Discussion

The first goal of this study was to determine if individual growth factors or cytokines might induce endothelial dysfunction through inhibition of Ca2+ signaling mechanisms. Initially, we used a standard dose of 10ng/ml for all growth factors and cytokines, which was based on previous published and unpublished studies from ovine and HUVEC models in which effects were related to Cx43 inhibitory phosphorylations via Src kinase activity (Boeldt et al., 2015,Khurshid, 2015). In this study, we clearly observed a significant loss of Ca2+ bursts in response to growth factors and cytokines. Therefore, all agents investigated are capable of negatively influencing Ca2+ burst responses. The mechanism of signaling action for the most inhibitory factors alone (VEGF165, TNFα, and bFGF) are all capable of promoting phosphorylation of Cx43 gap junction proteins because they all couple directly to Src (Boeldt et al., 2015,Bird et al., 2013,Vitale and Barry, 2015). This was demonstrated in detail with VEGF165 and TNFα in the ovine uterine artery and human umbilical vein models (Boeldt et al., 2015,Boeldt et al., 2017,Ampey et al., 2019). Such a proposal is consistent with the findings of others who have suggested VEGF165, EGF, bFGF, TNFα (directly) or IL-6, and IL-8 (indirectly) activate Src kinase to varying degrees (Deo et al., 2002,Eliceiri et al., 1999,Nwariaku et al., 2002,Tang et al., 2007,Huang et al., 2013,Liu et al., 2016), and is supported by Y265 phospho-Cx43 data herein. We were then able to assess the ability of potential nutraceutical therapeutic agent (t10,c12 CLA alone or mixed 1:1 with c9,t11 CLA) to inhibit Src kinase and rescue endothelial function. Because c9,t11 CLA is not known to block Src activation, it was included as a negative control. Indeed, c9,t11 CLA was unable to improve Ca2+ signaling after treatment with any of the growth factors or cytokines used. Since t10,c12 CLA has been shown to inhibit c-Src in cancer cells (Shahzad et al., 2018), we hypothesized that treatment with any CLA mixture that includes this isomer would rescue Ca2+ signaling from insult mediated by Src activation, whether directly or indirectly. Significant improvements were observed for VEGF165, TNFα, and bFGF. Western blot data for Y265 phsopho-Cx43 suggested that the t10,c12 CLA isomer does mediate Cx43 function through Src signaling, and as a pretreatment for TNFα, restores Y265 phosphorylation to control levels. The growth factors and cytokines which are known to couple directly to Src (i.e. the non-interleukins VEGF165, EGF, bFGF, and TNFα) had a positive correlation between degree of inhibition and degree of rescue. Of note, EGF is a particularly weak inhibitor and it is noteworthy that previous studies in HUVEC have shown EGF receptor numbers are very low in HUVEC (Al-Nedawi, Meehan, Kerbel et al., 2009). Those interleukin receptors that couple signaling to Src indirectly (i.e. receptors to IL-8, IL-6, and IL-1β) all displayed a negative correlation between degree of inhibition and degree of rescue.

While the phospho-Cx43 blockade by t10,c12 CLA is clearer for TNFα than VEGF165, it should be noted that only a portion of all Cx43 resides in functional gap junctional plaques, so it is a considerable challenge to detect significant changes in Y265 phosphorylation that mimic functional outcomes, such as Ca2+ burst responses. Indeed VEGF165 failed to achieve the statistically significant Y265 Cx43 phosphorylation by western blot clearly observed for TNFα. However, when the VEGF165 data for c9,t11 CLA, t10,c12 CLA, and the 1:1 mix of isomers are added to the equivalent data for TNFα and plotted against Ca2+ burst data, it is very clear that a significant negative correlation between Cx43 phosphorylation at Y265 and loss of Ca2+ bursts exists. This supports previous work in which we have shown that GAP peptide-mediated inhibition of Cx43 function results in a loss of Ca2+ bursting function as well (Yi et al., 2010). That the c9,t11 isomer results in significant phosphorylation of Y265 on its own, is an interesting result that warrants further study.

The Src specificity of Y265 on Cx43 has been demonstrated clearly in numerous studies, and has been clearly described in the context of cell function in seminal reviews by Lampe and Lau (Lampe and Lau, 2000,Lampe and Lau, 2004). Initial studies linked Src only to tyrosine phosphorylation on Cx43 (Loo, Berestecky, Kanemitsu et al., 1995,Loo, Kanemitsu and Lau, 1999), but other studies demonstrated that Y247 and Y265 were Src substrates (Kanemitsu, Loo, Simon et al., 1997,Giepmans, Hengeveld, Postma et al., 2001,Lin, Warn-Cramer, Kurata et al., 2001,Lin, Warn-Cramer, Kurata et al., 2001). However, Y247 phosphorylation appears to be dependent on Y265 phosphorylation (Lin et al., 2001) and therefore Y265 likely presents a better in vitro assay target for Src activity at Cx43. In the ovine uterine artery endothelial cell (UAEC) model, PP2 specifically inhibits Y265 pCx43 and not the MEK/ERK specific Ser279/282 pCx43 after VEGF165 or TNFα stimulation, with TPA as a positive control (Boeldt et al., 2015,Ampey et al., 2019). Those studies also linked Cx43 phosphorylation with decreased sustained Ca2+ bursting in the context of pregnancy adapted endothelial function.

While such previous work in the ovine UAEC model demonstrated strongly the connection between Cx43 gap junction function and Ca2+ bursting capacity (Yi et al., 2010,Boeldt et al., 2015), the HUVEC model does not mirror those results exactly. The previous studies in UAEC and HUVEC also stopped short of directly implicating reversal of Cx43 phosphorylation as a mechanism by which CLA may be rescuing Ca2+ burst function after growth factor or cytokine pretreatment. In HUVEC, inhibition of gap junction function with GAP peptides revealed that while Cx43 was important for Ca2+ bursting function, there is likely also a role for Cx37 and Cx40 potentially via heteromeric or heterotypic gap junctions. Cx37 expression has been found to be increased in pregnancy in ovine uterine arteries (Morschauser, Ramadoss, Koch et al., 2014) though it does not appear to have a direct role in Ca2+ signaling. Thus, a potential role for Cx37 is more likely than Cx40, but still remains unclear at this time. These observed differences may be species specific or could be due to the vasculature bed from which the endothelial cells are derived, and may contribute to the difficulty of clean Cx43 Y265 phosphorylation western blots, as the gap junctions may be comprised of a heterogeneous mixture of Cx isoforms (Boeldt et al., 2017).

In general, CLA may be most effective as a therapeutic rescue agent in those conditions that are most inhibitory to Ca2+ signaling, and particularly via Src and ERK. But in those conditions that are only modestly inhibitory, CLA may be a poor candidate for therapy. This fits with clinical studies where CLA has little effect on blood pressure in healthy subjects (Yang, Wang, Zhou et al., 2015) but can improve blood pressure in hypertensive subjects (Sato, Shinohara, Honma et al., 2011). Estimates of the dose of CLA the patients from these studies received would be around 10uM, also suggesting that our 10uM 1:1 mix dose could be therapeutically relevant. In a cohort at risk for complicated pregnancies (women age 18 and younger) treatment with calcium (addressing a nutritional deficit) and CLA resulted in a decreased incidence of PE. The decreased PE incidence was not observed in the group receiving only calcium supplementation, implicating a role for CLA in prevention of PE in human pregnancies (Alzate, Herrera-Medina and Pineda, 2015). In this study, the coupling of Cx43 phosphorylation with the Ca2+ data implicates a mechanistic role for CLA in protecting pregnancy-adapted Ca2+ signaling via blocking Src-mediated gap junction functional inhibition that may have been unappreciated in the Colombian trial. In further support of the potential role for CLA to support gap junction communication, Rakib et al have reported that CLA has been found to prevent TPA-mediated phosphorylation of Cx43 gap junctions (Rakib, Kim, Jang et al., 2010). Taken together, this work indicates that CLA treatment could potentially be beneficial for hypertensive diseases but warrants further mechanistic work.

Another goal of this study was to measure the effect of a cocktail of growth factors and cytokines on endothelial Ca2+ signaling. This was designed as the first step to more closely mimic the in vivo signaling environment of endothelial dysfunction, specifically that of PE. These combinations in turn may trigger combinations of signaling responses that may be additive or even synergistic on Cx43 inhibition. This is all the more relevant when one considers that interleukins such as IL-6 can possibly amplify Src activation by agents such as TNFα through GP130 signaling (Schaper and Rose-John, 2015). We used published data on levels of growth factors and cytokines in preeclampsia to guide our cocktail creation (Lau et al., 2013,Tosun et al., 2010,Xie et al., 2011). We used a dose response of VEGF165 in our cocktails as there is debate in the field of preeclampsia research on VEGF165 levels in the disease state. We rounded out our ‘cocktails’ by first adding in TNFα (0.5ng/ml) initially (Figure 9) and then further adding IL-6 (3ng/ml) in Figure 10. As a negative control, we also created cocktails which reflect the levels of VEGF165, TNFα, and IL-6 in a non-pathologic state.

When taken together, the V+T and V+T+IL-6 cocktails revealed some important points. For one, combination treatments seemed to magnify the degree of inhibition compared to any individual growth factor or cytokine, especially given that the doses for all but the high VEGF165 were well below the 10ng/ml doses from the individual factor experiments. Both high VEGF165 combinations dropped Ca2+ signaling well out of the normal physiological range. The 1:1 Mix CLA treatment was able to restore function to the physiological range, however, considerable improvement capacity remains. In the absence of any IL-6, VEGF165 mediated Ca2+ signaling in a dose dependent manner, with TNFα taking a secondary role in modulating the response amplitude. However, when IL-6 was also present, it had a profound impact. In the Normal cocktail, the small amount of IL-6 added improved the inhibitory Normal V+T response to one indistinguishable from control. When IL-6 was increased, it made the Low V+T cocktail profoundly more inhibitory than in the absence of IL-6. As VEGF165 concentrations increased into the medium and high levels, it again reclaimed the dominant role. As with the individual growth factors and cytokines, it appears that the degree of rescue is related to the degree of Ca2+ burst inhibition.

It is also worth noting that in some cases cytokines and growth factors can stimulate Ca2+ and NO responses in their own right. Numerous studies report on the vasodilator properties of VEGF165, and our own studies in UAEC and HUVEC confirm this (Boeldt et al., 2017,Yi et al., 2011). However, VEGF165 and other growth factors and cytokines are relatively weak vasodilators and when compared to the concomitant inhibitory effects of better vasodilators such as ATP or Bradykinin, which result in a net deficit of vasodilator production (Reviewed in (Bird et al., 2013,Boeldt, Yi and Bird, 2011,Boeldt, Hankes, Alvarez et al., 2014)). It is therefore important to consider the role of such peptides on overall vasodilator production, and in inflammatory conditions such as PE where TNFα, IL-6, and in certain cases VEGF165 are elevated, overall endothelial vasodilator production capacity is diminished. It is for this reason that selectively targeting the signaling pathways downstream of VEGF165, TNFα, and IL-6 that negatively impact upon endothelial Ca2+ signaling may present a novel therapeutic approach. That CLA formulations may provide some benefit to endothelial Ca2+ signaling by blocking Y265 phosphorylation in Cx43 is an important consideration.

This study did not address the potential role of Ca2+ permeable channels contributing to sustained phase Ca2+ signaling. It is plausible that such channels may play a role in the remaining Ca2+ signaling function untouched by CLA treatment. TRP and ORAI channels are key regulators of extracellular Ca2+ influx (Silva and Ballejo, 2019) in endothelial cells. Traditionally, canonical transient receptor potential (TRP) channels have been thought to have an integral role in endothelial Ca2+ signaling. Specifically TRPC4 has been found to be expressed in endothelial cells and to contribute to Ca2+ homeostasis (Graziani, Poteser, Heupel et al., 2010), and TRPC1, TRPC3, and TRPC6 have been implicated in specific endothelial cell types (Gifford, Yi and Bird, 2006,Ge, Tai, Sun et al., 2009,Groschner, Hingel, Lintschinger et al., 1998,Cheng, James, Foster et al., 2006). ORAI channels are multimeric channels comprised of ORAI family member proteins, of which ORAI1 is best characterized, and are activated by Stim 1 and 2 (Bergmeier, Weidinger, Zee et al., 2013). Abdullaev et al have reported that in HUVECs downregulation of Stim1 or Orai1 suppressed store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) and ectopic expression eYFP-Stim1 or CFP-Orai1 was able to rescue SOCE. They also reported that knockdown of TRPC1 or TRPC4 did not inhibit SOCE (Abdullaev, Bisaillon, Potier et al., 2008). There are additional reports that TRPC channels may be involved in maintenance of ORAI channel components long term (Abdullaev et al., 2008), that there is cross-talk between ORAI and TRP channels (Graziani et al., 2010) and that both ORAI and TRP channels are involved in Ca2+ influx within the first five minutes after stimulant-mediated ER store release (Silva and Ballejo, 2019). Elucidating the role of these channels further in HUVECs may provide insight into the strategy to achieve full rescue of growth factor and cytokine mediated inhibition of Ca2+ signaling.

In conclusion, our data suggest that several growth factors and cytokines alone or in combination may act additively or synergistically to cause Src-mediated loss of Ca2+ bursting via inhibition of Cx43 gap junctions. Prolonged exposure of such hormone combinations via Src signaling would certainly promote sustained phosphorylation of Cx43 gap junction protein at inhibitory sites, possibly resulting in disassembly of the membrane structural protein arrays in which Cx43 resides. The result of such Cx43 disassembly could be chronic loss of vasodilation and even edema, once cell-cell communication between cells is disrupted (Bird et al., 2013). Treatment with CLA, either as t10,c12 CLA or a 1:1 mix of c9,t11 and t10,c12 CLA at a suitable dose may be useful as a treatment for endothelial dysfunction based on their ability to protect against Src- mediated disruptions of Cx43 gap junction function.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

GF/Cyt, alone or in combination, promote endothelial dysfunction and are rescued by the nutraceutical CLA.

GF/Cyt coupled directly to Src mediate this damage, and rescue is achieved by t10,c12 CLA or a 1:1 mix of c9,t11 and t10,c12 CLA.

Interleukins are less damaging than GFs, and are more resistant to CLA rescue.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was undertaken by NK and DMB as part of their MS, and AKM as part of her PhD in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Endocrinology and Reproductive Physiology Training program. Current institution of NK is Promedica Toledo Hospital, Toledo, OH. Current institution for DMB is Gundersen Health, LaCrosse, WI. AKM was also supported by NIH T32 predoctoral training award HD041921.

Financial Support: NIH R21 HD069181, P01 HD038843, and R03 HD079865. Funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: DSB and IMB have patent pending for the therapeutic use of t10,c12 CLA in preeclampsia. No other authors have conflicts to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Visser N, van Rijn BB, Rijkers GT, Franx A and Bruinse HW, 2007. Inflammatory changes in preeclampsia: current understanding of the maternal innate and adaptive immune response, Obstet Gynecol Surv. 62, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Saito S, Shiozaki A, Nakashima A, Sakai M and Sasaki Y, 2007. The role of the immune system in preeclampsia, Mol Aspects Med. 28, 192–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rajendran P, Rengarajan T, Thangavel J, Nishigaki Y, Sakthisekaran D, Sethi G and Nishigaki I, 2013. The vascular endothelium and human diseases, Int J Biol Sci. 9, 1057–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Boeldt DS and Bird IM, 2017. Vascular adaptation in pregnancy and endothelial dysfunction in preeclampsia, J Endocrinol. 232, R27–R44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tran QK, Leonard J, Black DJ, Nadeau OW, Boulatnikov IG and Persechini A, 2009. Effects of combined phosphorylation at Ser-617 and Ser-1179 in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase on EC50(Ca2+) values for calmodulin binding and enzyme activation, The Journal of biological chemistry. 284, 11892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yi FX, Boeldt DS, Gifford SM, Sullivan JA, Grummer MA, Magness RR and Bird IM, 2010. Pregnancy enhances sustained Ca2+ bursts and endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation in ovine uterine artery endothelial cells through increased connexin 43 function, Biology of reproduction. 82, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yi FX, Magness RR and Bird IM, 2005. Simultaneous imaging of Ca2+ i and intracellular NO production in freshly isolated uterine artery endothelial cells: effects of ovarian cycle and pregnancy, American journal of physiology.Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 288, R140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Krupp J, Boeldt DS, Yi FX, Grummer MA, Bankowski Anaya HA, Shah DM and Bird IM, 2013. The loss of sustained Ca(2+) signaling underlies suppressed endothelial nitric oxide production in preeclamptic pregnancies: implications for new therapy, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 305, H969–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Boeldt DS, Grummer MA, Yi F, Magness RR and Bird IM, 2015. Phosphorylation of Ser-279/282 and Tyr-265 positions on Cx43 as possible mediators of VEGF-165 inhibition of pregnancy-adapted Ca2+ burst function in ovine uterine artery endothelial cells, Mol Cell Endocrinol. 412, 73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Boeldt DS, Krupp J, Yi FX, Khurshid N, Shah DM and Bird IM, 2017. Positive versus negative effects of VEGF165 on Ca2+ signaling and NO production in human endothelial cells, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 312, H173–H181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bird IM, Boeldt DS, Krupp J, Grummer MA, Yi FX and Magness RR, 2013. Pregnancy, programming and preeclampsia: gap junctions at the nexus of pregnancy-induced adaptation of endothelial function and endothelial adaptive failure in PE, Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 11, 712–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Solan JL and Lampe PD, 2009. Connexin43 phosphorylation: structural changes and biological effects, The Biochemical journal. 419, 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Solan JL and Lampe PD, 2014. Specific Cx43 phosphorylation events regulate gap junction turnover in vivo, FEBS Lett. 588, 1423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ampey AC, Boeldt DS, Clemente L, Grummer MA, Yi F, Magness RR and Bird IM, 2019. TNF-alpha inhibits pregnancy-adapted Ca(2+) signaling in uterine artery endothelial cells, Mol Cell Endocrinol. 488, 14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yi FX, Boeldt DS, Magness RR and Bird IM, 2011. Ca2+ i signaling vs. eNOS expression as determinants of NO output in uterine artery endothelium: relative roles in pregnancy adaptation and reversal by VEGF165, American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 300, H1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].D’Angelo G, Struman I, Martial J and Weiner RI, 1995. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in capillary endothelial cells is inhibited by the antiangiogenic factor 16-kDa N-terminal fragment of prolactin, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 92, 6374–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Deo DD, Axelrad TW, Robert EG, Marcheselli V, Bazan NG and Hunt JD, 2002. Phosphorylation of STAT-3 in response to basic fibroblast growth factor occurs through a mechanism involving platelet-activating factor, JAK-2, and Src in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Evidence for a dual kinase mechanism, J Biol Chem. 277, 21237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Eliceiri BP, Paul R, Schwartzberg PL, Hood JD, Leng J and Cheresh DA, 1999. Selective requirement for Src kinases during VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability, Mol Cell. 4, 915–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Huang S, Dudez T, Scerri I, Thomas MA, Giepmans BN, Suter S and Chanson M, 2003. Defective activation of c-Src in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells results in loss of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced gap junction regulation, The Journal of biological chemistry. 278, 8326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nwariaku FE, Liu Z, Zhu X, Turnage RH, Sarosi GA and Terada LS, 2002. Tyrosine phosphorylation of vascular endothelial cadherin and the regulation of microvascular permeability, Surgery. 132, 180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Parenti A, Morbidelli L, Cui XL, Douglas JG, Hood JD, Granger HJ, Ledda F and Ziche M, 1998. Nitric oxide is an upstream signal of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation in postcapillary endothelium, J Biol Chem. 273, 4220–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tang CH, Yang RS, Chen YF and Fu WM, 2007. Basic fibroblast growth factor stimulates fibronectin expression through phospholipase C gamma, protein kinase C alpha, c-Src, NF-kappaB, and p300 pathway in osteoblasts, J Cell Physiol. 211, 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Waltenberger J, Claesson-Welsh L, Siegbahn A, Shibuya M and Heldin CH, 1994. Different signal transduction properties of KDR and Flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor, J Biol Chem. 269, 26988–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Huang YH, Yang HY, Hsu YF, Chiu PT, Ou G and Hsu MJ, 2013. Src contributes to IL6-induced vascular endothelial growth factor-C expression in lymphatic endothelial cells, Angiogenesis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liu CJ, Kuo FC, Wang CL, Kuo CH, Wang SS, Chen CY, Huang YB, Cheng KH, Yokoyama KK, Chen CL, Lu CY and Wu DC, 2016. Suppression of IL-8-Src signalling axis by 17beta-estradiol inhibits human mesenchymal stem cells-mediated gastric cancer invasion, J Cell Mol Med. 20, 962–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Redman CW, Sacks GP and Sargent IL, 1999. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 180, 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lau SY, Guild SJ, Barrett CJ, Chen Q, McCowan L, Jordan V and Chamley LW, 2013. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10 levels are altered in preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Am J Reprod Immunol. 70, 412–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tosun M, Celik H, Avci B, Yavuz E, Alper T and Malatyalioglu E, 2010. Maternal and umbilical serum levels of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in normal pregnancies and in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia, J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 23, 880–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Xie C, Yao MZ, Liu JB and Xiong LK, 2011. A meta-analysis of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10 in preeclampsia, Cytokine. 56, 550–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shahzad MMK, Felder M, Ludwig K, Van Galder HR, Anderson ML, Kim J, Cook ME, Kapur AK and Patankar MS, 2018. Trans10,cis12 conjugated linoleic acid inhibits proliferation and migration of ovarian cancer cells by inducing ER stress, autophagy, and modulation of Src, PLoS One 13, e0189524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Grummer MA, Sullivan JA, Magness RR and Bird IM, 2009. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts through novel, pregnancy-enhanced receptor signalling pathways to stimulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in uterine artery endothelial cells, The Biochemical journal. 417, 501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Sullivan JA, Grummer MA, Yi FX and Bird IM, 2006. Pregnancy-enhanced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activation in uterine artery endothelial cells shows altered sensitivity to Ca2+, U0126, and wortmannin but not LY294002--evidence that pregnancy adaptation of eNOS activation occurs at multiple levels of cell signaling, Endocrinology. 147, 2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Khurshid N, 2015. Wounding as a Central Mechanism for Preeclampsia.

- [34].Vitale ML and Barry A, 2015. Biphasic Effect of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor on Anterior Pituitary Folliculostellate TtT/GF Cell Coupling, and Connexin 43 Expression and Phosphorylation, J Neuroendocrinol. 27, 787–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Kerbel RS, Allison AC and Rak J, 2009. Endothelial expression of autocrine VEGF upon the uptake of tumor-derived microvesicles containing oncogenic EGFR, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106, 3794–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lampe PD and Lau AF, 2000. Regulation of gap junctions by phosphorylation of connexins, Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 384, 205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lampe PD and Lau AF, 2004. The effects of connexin phosphorylation on gap junctional communication, The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 36, 1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Loo LW, Berestecky JM, Kanemitsu MY and Lau AF, 1995. Pp60src-mediated phosphorylation of connexin 43, a gap junction protein, The Journal of biological chemistry. 270, 12751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Loo LW, Kanemitsu MY and Lau AF, 1999. In vivo association of pp60v-src and the gap-junction protein connexin 43 in v-src-transformed fibroblasts, Molecular carcinogenesis. 25, 187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kanemitsu MY, Loo LW, Simon S, Lau AF and Eckhart W, 1997. Tyrosine phosphorylation of connexin 43 by v-Src is mediated by SH2 and SH3 domain interactions, The Journal of biological chemistry. 272, 22824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Giepmans BN, Hengeveld T, Postma FR and Moolenaar WH, 2001. Interaction of c-Src with gap junction protein connexin-43. Role in the regulation of cell-cell communication, J Biol Chem. 276, 8544–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lin R, Warn-Cramer BJ, Kurata WE and Lau AF, 2001. v-Src phosphorylation of connexin 43 on Tyr247 and Tyr265 disrupts gap junctional communication, The Journal of cell biology. 154, 815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lin R, Warn-Cramer BJ, Kurata WE and Lau AF, 2001. v-Src-mediated phosphorylation of connexin43 on tyrosine disrupts gap junctional communication in mammalian cells, Cell Commun Adhes. 8, 265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Morschauser TJ, Ramadoss J, Koch JM, Yi FX, Lopez GE, Bird IM and Magness RR, 2014. Local effects of pregnancy on connexin proteins that mediate Ca2+-associated uterine endothelial NO synthesis, Hypertension. 63, 589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yang J, Wang HP, Zhou LM, Zhou L, Chen T and Qin LQ, 2015. Effect of conjugated linoleic acid on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trials, Lipids Health Dis. 14, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sato K, Shinohara N, Honma T, Ito J, Arai T, Nosaka N, Aoyama T, Tsuduki T and Ikeda I, 2011. The change in conjugated linoleic acid concentration in blood of Japanese fed a conjugated linoleic acid diet, J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 57, 364–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Alzate A, Herrera-Medina R and Pineda LM, 2015. Preeclampsia prevention: a case-control study nested in a cohort, Colomb Med (Cali). 46, 156–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Rakib MA, Kim YS, Jang WJ, Choi BD, Kim JO, Kong IK and Ha YL, 2010. Attenuation of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) inhibition in MCF-10A cells by c9,t11-conjugated linoleic acid, J Agric Food Chem. 58, 12022–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schaper F and Rose-John S, 2015. Interleukin-6: Biology, signaling and strategies of blockade, Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 26, 475–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Boeldt DS, Yi FX and Bird IM, 2011. eNOS activation and NO function: pregnancy adaptive programming of capacitative entry responses alters nitric oxide (NO) output in vascular endothelium--new insights into eNOS regulation through adaptive cell signaling, The Journal of endocrinology. 210, 243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Boeldt DS, Hankes AC, Alvarez RE, Khurshid N, Balistreri M, Grummer MA, Yi F and Bird IM, 2014. Pregnancy programming and preeclampsia: identifying a human endothelial model to study pregnancy-adapted endothelial function and endothelial adaptive failure in preeclamptic subjects, Adv Exp Med Biol. 814, 27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Silva J and Ballejo G, 2019. Pharmacological characterization of the calcium influx pathways involved in nitric oxide production by endothelial cells, Einstein; (Sao Paulo: ). 17, eAO4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Graziani A, Poteser M, Heupel WM, Schleifer H, Krenn M, Drenckhahn D, Romanin C, Baumgartner W and Groschner K, 2010. Cell-cell contact formation governs Ca2+ signaling by TRPC4 in the vascular endothelium: evidence for a regulatory TRPC4-beta-catenin interaction, J Biol Chem. 285, 4213–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gifford SM, Yi FX and Bird IM, 2006. Pregnancy-enhanced store-operated Ca2+ channel function in uterine artery endothelial cells is associated with enhanced agonist-specific transient receptor potential channel 3-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor 2 interaction, The Journal of endocrinology. 190, 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ge R, Tai Y, Sun Y, Zhou K, Yang S, Cheng T, Zou Q, Shen F and Wang Y, 2009. Critical role of TRPC6 channels in VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, Cancer letters. 283, 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Groschner K, Hingel S, Lintschinger B, Balzer M, Romanin C, Zhu X and Schreibmayer W, 1998. Trp proteins form store-operated cation channels in human vascular endothelial cells, FEBS letters. 437, 101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Cheng HW, James AF, Foster RR, Hancox JC and Bates DO, 2006. VEGF activates receptor-operated cation channels in human microvascular endothelial cells, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 26, 1768–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Bergmeier W, Weidinger C, Zee I and Feske S, 2013. Emerging roles of store-operated Ca(2)(+) entry through STIM and ORAI proteins in immunity, hemostasis and cancer, Channels (Austin). 7, 379–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Abdullaev IF, Bisaillon JM, Potier M, Gonzalez JC, Motiani RK and Trebak M, 2008. Stim1 and Orai1 mediate CRAC currents and store-operated calcium entry important for endothelial cell proliferation, Circ Res. 103, 1289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.