Abstract

Whole body exercise tolerance is the consummate example of integrative physiological function among the metabolic, neuromuscular, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems. Depending on the animal selected, the energetic demands and flux through the oxygen transport system can increase two orders of magnitude from rest to maximal exercise. Thus, animal models in health and disease present the scientist with flexible, powerful, and, in some instances, purpose-built tools to explore the mechanistic bases for physiological function and help unveil the causes for pathological or age-related exercise intolerance. Elegant experimental designs and analyses of kinetic parameters and steady-state responses permit acute and chronic exercise paradigms to identify therapeutic targets for drug development in disease and also present the opportunity to test the efficacy of pharmacological and behavioral countermeasures during aging, for example. However, for this promise to be fully realized, the correct or optimal animal model must be selected in conjunction with reproducible tests of physiological function (e.g., exercise capacity and maximal oxygen uptake) that can be compared equitably across laboratories, clinics, and other proving grounds. Rigorously controlled animal exercise and training studies constitute the foundation of translational research. This review presents the most commonly selected animal models with guidelines for their use and obtaining reproducible results and, crucially, translates state-of-the-art techniques and procedures developed on humans to those animal models.

Listen to this article’s corresponding podcast at: https://ajpheart.podbean.com/e/guidelines-for-animal-exercise-and-training-protocols/.

Keywords: critical speed, exercise tolerance, exhaustion, maximal oxygen uptake, oxygen transport system

WHY ARE EXERCISE STUDIES RELEVANT?

Muscular exercise presents the greatest physiological challenge to the organism’s oxygen transport pathway and the coordinated function of the respiratory, cardiovascular, and neuromuscular systems. Just as an automobile needs a test drive, exercise tests represent often the best, or sometimes the only, strategy for determining the presence and severity of organic dysfunction (457). For instance, as determined initially by Karl Weber and colleagues (459, 460), the assessment of heart failure (HF) and recommendations for therapeutic options (287) are based on the maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2max) as measured most conveniently during a ramp or incremental exercise test. This test is generally performed on a cycle ergometer or treadmill and employs a large muscle mass with the implicit understanding that the patients push themselves to exhaustion and do not quit for some other reason unrelated to the capacity of their O2 transport system and muscle contractile limitation (346).

Not only is exercise invaluable for diagnosis, but also, as recognized as early as 1777 by the English physician William Heberden (471), muscular exertion presents a powerful therapeutic option that reduces the predations of, for example, HF, helping to reverse disease-induced exercise intolerance and improving the patient’s quality of life (173, 364, 365, 371). In addition, scientists and clinicians use exercise tests routinely as a sensitive tool to determine treatment efficacy and increasingly as a mechanism for identifying therapeutic targets to develop novel pharmacological approaches to combat pathological dysfunction. An excellent example of this latter approach is the work of Scott Powers and colleagues, who have identified superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in the myocardium as a key defense mechanism that is upregulated by exercise training and can constrain the myocardial damage consequent to transient ischemia as produced by infarction (381–383).

Although the value of therapeutic approaches often ultimately rests on their ability to reduce the burden of suffering in humans, there are many compelling reasons for the investigator to select an animal over a human model for concept development, unravelling of control mechanisms, and proof of efficacy and also for direct application to the treatment of organic dysfunction in animals.

Paramount among these are the following:

-

1.

Existence of a range of animal models for human diseases in which the disease duration and severity can be controlled.

-

2.

Absence of, or control over, confounding drug treatments.

-

3.

Greater control over subject numbers, diet, and exercise history.

-

4.

Uniformity in genetic background and time course of disease/treatment application.

-

5.

More freedom in invasive procedures such as muscle(s) sampling for structural analyses, oxidative enzymes, respirometry, and in vitro vessel function.

-

6.

Amenability to both acute and chronic exercise interventions.

Kent et al. (223) have presented multiple lines of cardiovascular discovery using exercise models that were initiated in animals as the fundamental step for designing and testing explicit hypotheses in humans. It is no exaggeration to state that the present field of physiology, especially as this relates to exercise, muscle energetics, and metabolism, the O2 transport pathway, and the mechanistic bases for exhaustion, has been founded on animal research. As foreseen by the pioneering comparative physiologists Claude Bernard (33) and, later, August Steenberg Krogh, “for many problems there is an animal model on which it can be most conveniently studied” (245). Well-crafted experimental designs using animals allow an unparalleled vertical integration of methodologies at each level of size and complexity from the subcellular level, to individual muscles/organs, up to the intact functioning organism through a range of oxygen transport, from resting, ~2 mL O2·kg−1·min−1, up to over 200 mL O2·kg−1·min−1 in the exercising horse, for example. Exemplars of key issues addressed in health and disease include defining the following: the upper limits to skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise, the heterogeneity of blood flow among/within muscles at rest and during exercise, and the role of nitric oxide in exercise hyperemia, as well as unravelling the complexities of vascular control and the impact of aging and disease on these processes. Selective gene knockouts and other genetic manipulations, predominantly in mice, have also advanced our understanding of the molecular control of structure and function as it relates to physiological performance.

EXERCISE TESTING AND TRAINING IN HUMANS AND ANIMALS

Exercise testing and training procedures in humans have undergone radical revision in the past three to four decades, in part, due to a greater understanding of physiological function/dysfunction in health and disease, the importance of the kinetics following exercise onset and in recovery, and the availability of more powerful research tools. These tools include rapidly responding gas analyzers, near-infrared spectroscopy, and real-time magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). There has also been a greater appreciation of exercise intensity domains, as defined in the critical power (CP) or critical speed (CS) concept, and the physiological behaviors and fatigue mechanisms operant within each (73, 74, 76, 207, 367). Knowing a subject’s CP or CS [and energy stores component (W′) or the expression of such when running as distance (D′)] allows structuring of exercise tests that are more reproducible and, importantly, can be equated across subjects and studies to better evaluate therapeutic efficacy and outcomes. It has become evident that the percentage V̇o2max reference or peak power achieved on a given test are poor surrogates for the CP or CS-based standard (465). Another crucial issue that has been emphasized by the popularity of the incremental/ramp test is the ability to discriminate that V̇o2max has been measured rather than some motivational or symptom-limited exercise end point that does not reflect the capacity of the O2 transport system (sometimes termed V̇o2peak; 372). Validation of V̇o2max in both human and animal studies is extremely important where this is a criterion outcome.

Given the rediscovery that for many conditions including HF, exercise for patients in recovery produces better outcomes than bed rest, a pertinent question is: What intensity of exercise produces the best outcomes? Despite the longstanding dogma that patients eschew severe or even heavy exercise intensity for more moderate exercise intensities, animal (1, 200, 244) and human (475, 476) exercise investigations have unequivocally demonstrated that high-intensity (i.e., severe) interval exercise training (so-called HIIT) increases V̇o2max and beneficial cardiovascular adaptations far more than moderate-intensity protocols. Moreover, and contrary to enduring medical misconceptions, epidemiological studies to date support that the risk for exercise-related cardiac incidents during rehabilitation is extremely low for both exercise training paradigms (395). This finding has a direct bearing on the selection of animal models based on their ability, willingness, and robustness to undergo HIIT and also facilitate important cardiovascular measurements during exercise.

The subsequent sections will initially review state-of-the-art developments in human exercise testing, present how these may translate to animals, and finally consider a range of animal models by species and protocols broadly suitable for exercise studies. Where possible, common best practices, pros and cons of each species considered, and additional important practical and theoretical considerations will be presented. For further information associated with exercise testing in different species, the reader is referred to the American Physiological Society’s Resource Book for the Design of Animal Exercise Protocols (5).

STATE-OF-THE-ART DEVELOPMENTS IN HUMAN EXERCISE TESTING

In 1986 the accomplished exercise physiologist Charles M. Tipton predicted that within a decade, animal exercise physiologists would have “…progressed to the degree of sophistication exhibited by human exercise physiologists” (442). However, from the perspective of at least two sentinel parameters of O2 transport/utilization and exercise performance, this optimistic aim does not appear to have been unequivocally achieved.

Maximal Oxygen Uptake

The classical measurement of maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2max) assesses, during large-muscle mass exercises such as running, cycling, cross-country skiing, or swimming, the coordinated capacity of the cardiorespiratory and muscular systems to uptake, transport, and utilize O2. Traditionally measured using a discontinuous series of step increments in work rate or speed, V̇o2max was defined as the highest V̇o2 achieved on a maximal exercise test and was evidenced by the failure of V̇o2 to increase commensurately with the energetic requirements; that is, V̇o2 plateaued when plotted against increasing work rate or speed. However, given the advent of rapidly responding gas analyzers in the 1970s and 1980s and the development of breath-by-breath gas analysis, the rapidly incremented or ramp exercise protocol permitted a compendium of ventilatory, gas exchange, cardiovascular, blood gas, and acid-base and metabolic measurements to be gathered simultaneously across the achievable range of exercise work rates from rest to maximal (exhaustion). Because identification of the gas exchange threshold (GET) is based on the rate of blood [H+] increase (principally from lactic acid), its buffering by bicarbonate, and consequent production of “extra” CO2, a duration of ~10 min or so is optimal, and so the slope of the imposed ramp is set on the basis of the exercise capacity of the subject to achieve the required duration (55). Whereas these protocols yielded a spectrum of submaximal indexes such as the GET and lactate threshold, work efficiency, and, arguably, V̇o2 kinetics, in many instances, subjects stopped exercising before manifesting a V̇o2 plateau, definitive for validation of V̇o2max. Indeed, for most subjects the V̇o2 profile increased linearly as a function of work rate throughout the test or, occasionally, projected upward at a faster rate toward the end of the test. For these subjects, in whom no definitive V̇o2 plateau was evinced, investigators either 1) accepted that it may not be a true V̇o2max and termed it V̇o2peak or 2) developed secondary criteria based on some arbitrary values for respiratory exchange ratio (RER), percentage of age-predicted maximal heart rate, and/or [lactate]. As neither of these procedures was commensurate with rigorous determination of V̇o2max a secondary exhausting validation test performed at a higher work rate or speed than achieved on the preceding ramp has been developed that facilitates a graphical solution to defining an individual’s V̇o2max (Fig. 1; 372).

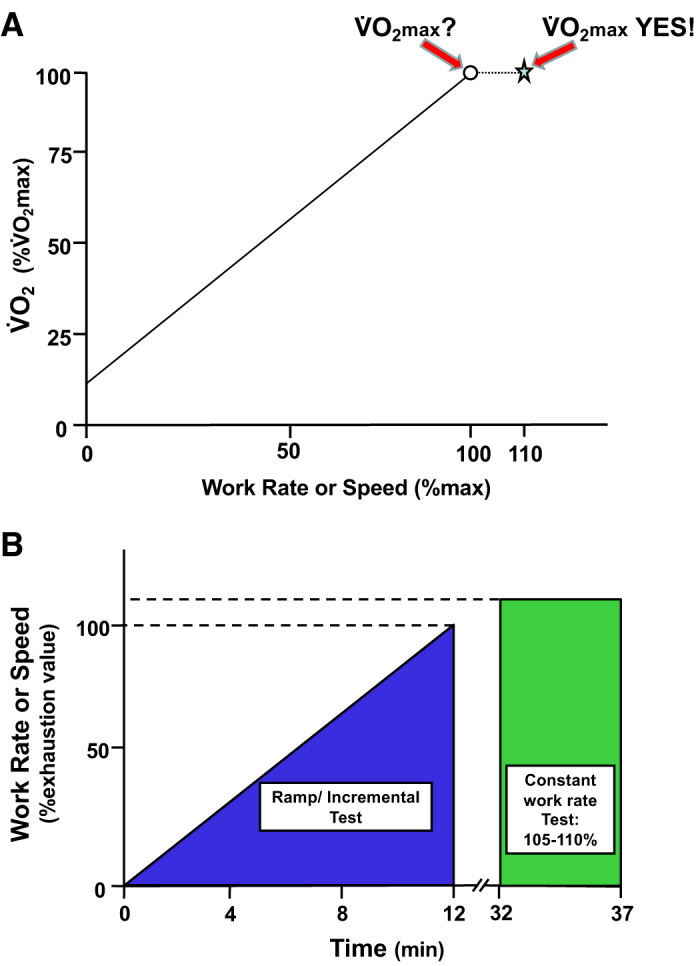

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the combination of the ramp test with the subsequent constant-load or constant-speed test (here at 110% maximum ramp value, star, A) validates that the ramp oxygen uptake (V̇o2; ○, A) was indeed maximal V̇o2 (V̇o2max) as evidenced by the presence of the V̇o2-work rate plateau. Had the V̇o2 increased at 110%, this would mandate that further testing at a still higher work rate or speed would be necessary to validate V̇o2max. Note that the ramp rate and also the constant work rate/speed bout must be scaled to the individual subject/population under investigation. The intervening rest period between tests is shown at 20 min (B), and this may be varied as species/model or protocol demands (372).

Critical Power and Critical Speed

Across populations, V̇o2max does not always correlate well with exercise tolerance, and invariably, exercise training or other perturbations that may increase V̇o2max modestly may translate into substantial increases in exercise performance that are highly variable (197, 377, 465). Thus, notwithstanding the concerns addressed above regarding V̇o2max measurement, a better functional parameter of exercise performance was needed that 1) has a greater translational value to the subject’s exercise tolerance and 2) facilitates setting an exercise intensity domain-specific work rate (i.e., above or below CP) so that changes in performance consequent to therapeutic intervention or the predations of disease are relatable across populations, across individual studies, and within discrete patient cohorts (465). It has been formally recognized, at least since 1925 (170), and probably much earlier [review by Jones et al. (207)], that the maximal duration for which a given power, speed, or, more correctly, metabolic rate (V̇o2; 27) can be sustained decreases hyperbolically as power (P) or speed (S) increases above some critical value (i.e., CP or CS) as described by (Fig. 2).

| (1) |

or, with respect to running speed, for example,

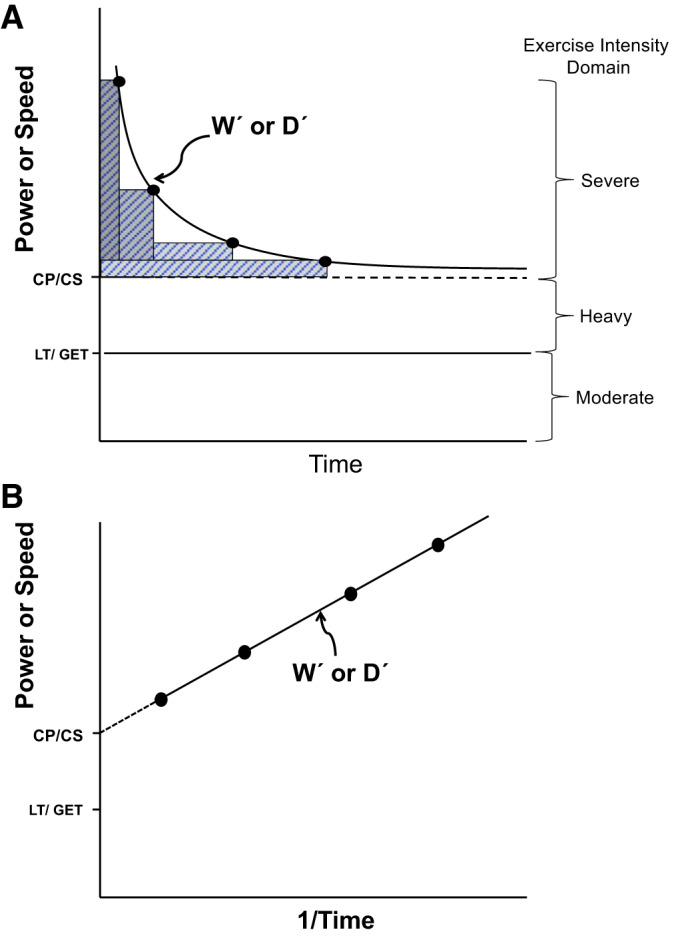

Fig. 2.

A: the hyperbolic power or speed-time relationship defines the limit of tolerance for whole body exercise such as cycling or running as well as individual muscle, joint, or muscle group exercise (isotonic or isometric). The curve is composed by having the subject (e.g., human, rat, mouse, or horse) exercise at constant power or speed to the point of exhaustion (●; 4 different workloads). Ideally, these bouts are performed on different days and exhaust the subject in 2–15 min. This hyperbolic relationship, which is highly conserved across the realm of human physical activities and exercise modes and also across the animal kingdom, is defined by two parameters: the asymptote for power [critical power (CP), speed (CS), or tension (CT) and their metabolic equivalent, oxygen uptake (V̇o2)] and the curvature constant Wʹ or Dʹ (W′, energy stores component; D′, expression of W′ when running as distance; denoted by the rectangular boxes above CP/CS and expressed in kJ or distance, respectively). Note that CP/CS defines the upper boundary of the heavy-intensity domain and represents the highest power sustainable without drawing continuously upon W′ or Dʹ. Above CP/CS (severe-intensity exercise), exhaustion occurs when Wʹ or Dʹ has been expended. Severe-intensity exercise is characterized by a V̇o2 profile that rises continuously to V̇o2max and blood lactate that increases to exhaustion. GET, gas exchange threshold; LT, lactate threshold. B: the hyperbolic relationship from above is linearized by plotting power or speed against 1/time, where the CP/CS parameter is given by the y-intercept and Wʹ or Dʹ by the slope. Correlative analyses with r > 0.98 provide confidence that maximal performances to exhaustion have been successfully measured.

| (2) |

where P and S are sustained power and speed (above CP or CS), respectively, and W′ (or D′ as distance run) denotes a discrete energy storage component that when depleted, signals exhaustion in time t. CP (or CS) constitutes the highest rate of oxidative energy provision possible without drawing continuously on W′ (or D′). The importance of CP/CS as a physiological parameter is underscored by its high reproducibility (127) and location at the boundary between the heavy- and severe-exercise intensity domains (357, 376) and in close proximity (−4% with respect to the marathon) to the speed (or V̇o2) at or above which most athletic track/running events are contested (206, 372, 418). Physiologically, CP/CS discriminates between exercise intensities that are sustainable for a very long duration versus those that incur exhaustion within a relatively brief duration that is highly predictable from the parameters CP or CS and W′ or D′ (127, 206, 357, 376, 418, 464).

Whereas the precise determinants of muscle exhaustion are likely to be context dependent, it is notable that work rates below versus above CP/CS display profoundly different behavior in that a steady state is attainable below but not above CP/CS [review by Jones et al. (206)]. This is true for pulmonary and leg V̇o2 as well as blood [lactate] [373, 376, 377; review given by Craig et al. (76) and Jones and colleagues (205, 207)], blood flow (73), intramuscular pH, [Pi], and [phosphocreatine] (205), and muscle torque production/neuromuscular fatigue (56). Setting work rate or speed relative to CP/CS helps ensure that changes in exercise capacity consequent to the predations of disease or imposed experimental interventions (e.g., exercise training, hyperthermia, hypoxia, 0-g environments, dietary modifications, etc.) or therapeutic treatments can be compared equitably within and across cohorts and study populations (465).

CONSIDERATIONS FOR ANIMAL MODEL SELECTION

Selection of an appropriate animal model for exercise testing and intervention will often necessitate solving a complex matrix of considerations that includes the following: 1) suitability, availability, and cost for a given experimental paradigm (if a genetic knockout is required, the investigator may be limited to the mouse; although more genetic rat models are becoming available); 2) willingness to exercise (mice, dogs, pigs, horses, and fish, yes; rabbits and cats, not so much) and the availability of required equipment and housing; 3) size of organism for sampling requirements on the continuum from Drosophila to elephant and beyond; 4) response of animal to essential surgical and experimental procedures; 5) presence (or absence) of discrete structures [e.g., contractile spleen in horses (370) and dogs (279, 453) or absence of discrete interpleural space in elephants (194)] or physiology/pathophysiology [e.g., malignant hyperthermia in pigs (78) or exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage in horses (108, 370)]; 6) understanding of exercise protocols by local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and compliance with reduce, refine, and replace mandates; 7) animal model that is de rigueur in a given field and with which an investigator wishes to compare their results; and 8) cost, availability, and number of animals required, based on appropriate statistical design.

Study Design Considerations: Protocol Development

Testing the impact of exercise on physiology and health outcomes in animals entails addressing multiple complex issues when choosing the best exercise protocol. The Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (342a) covers many issues across different types of research, including exercise research. The team approach to developing performance-based design and implementation standards is key to success for exercise-based studies. The research team, veterinary staff, and IACUC must work in synchrony to develop the animal care and use protocol with effective communication allowing the IACUC to comprehend the scientific issues, key methodologies, and often interpretational limitations that characterize exercise research. For their part, principal investigators (PIs) should recognize the importance of compliance with all policies and regulations governing animal care and use and especially the IACUC’s function in maintaining institutional compliance with regulatory mandates. This is best facilitated by open dialogue and professionalism throughout protocol development and review, which are crucial for establishing that working balance between rigorous science and excellent animal care.

Exercise protocol development faces two paramount challenges. 1) Reliable experimental and performance criteria must be established that match the study’s scientific goals with IACUC guidelines. 2) Humane procedures must be implemented for acute or chronic animal exercise protocols. Protocols and objective criteria must be established for terminating an exercise session and, if necessary, removing or euthanizing an animal. Criteria for such may differ during the training or conditioning period compared with the acute or chronic exercise phases of the study. Within the protocol development phase, it is the responsibility of the PI, IACUC, and laboratory animal veterinarians to develop an intervention plan, with a defined line of authority, that preempts or minimizes animal distress.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR EXERCISE STUDY DESIGN

IACUC Review

The National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (the Guide) and other relevant policies and regulations establish the basis for the PI and the IACUC to work together to develop protocols, outcome assessments, and required documentation. Key issues are discussed in the remainder of this section.

Animal Numbers

Good scientific practice and regulatory agencies require that animal numbers be minimized using rigorous statistical design techniques. The importance of rigorous statistical design and power calculations based on accurate effect sizes is essential. Using too few animals and being unable to make any conclusion is also a significant problem. The appendix of the Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (ILAR) document, Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (342a), details procedures for determining animal numbers. Statistical power calculations are de rigueur for determining sample sizes a priori. Effective experimental design, especially for exercise studies where some animals may not perform on a given day, or, indeed, at all, demands inclusion of additional replacement animals.

Animal Use

Specific to exercise studies, the IACUC protocol must detail the need for forced, in contrast to voluntary, exercise: whether that exercise is exhausting and, if so, defined end points/identifiers, workloads imposed including the duration, intensity, and number of individual exercise bouts required; the time interval between repeated bouts; overall study duration; the use/intensity/frequency of aversive stimuli to maintain performance; and the need for any special caging or restraint. Specific justification is necessary for housing or exercising animals under environmental conditions outside the ranges provided in the ILAR, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Procedures for animal familiarization with the specific environment and exercise equipment must be described along with pertinent animal monitoring procedures during exercise bouts and recovery. Criteria triggering premature termination of an exercise bout must be specified along with assurances that the responsible individual (PI, postdoctoral fellow, student, or technician) has the required training to recognize the relevant criteria. Research staff must be familiar with the normal appearance and behavior of the pertinent animal species to recognize problems promptly. If questions arise regarding animal health, the veterinary staff should be consulted regarding treatment of the animal or removal of the animal from the study. Timely intervention and treatment by the veterinarian may prevent the need to remove the animal from the study permanently.

Whereas exercise protocols have the potential to inadvertently injure experimental animals, implementation of the following will minimize such: For automated exercise equipment, most commonly treadmills, animals should be conditioned initially at low speeds, inclines, and durations with each being increased gradually as animals increase experience and capability. In this regard, selection of species that run willingly such as rats, mice, dogs, horses, pigs, and goats is a significant consideration in subject selection. Safety equipment that may reduce or prevent injury during exercise should be described such as presence of rapid cutoff switches and surcingle for horses that help prevent or minimize injury during a missed step at high speed. Realistic adverse consequences, for instance, drowning, physical injury, or increasing aversive stimuli tolerance, must be identified in the protocol along with applicable mitigation procedures. When historical data are not available, continuous monitoring is always preferable when using automated equipment.

Food and Water

Food and water may be used as exercise motivators. Requiring growing animals to exercise for their food often results in some minimum exercise level that provides low caloric yields and less rapid growth or weight loss compared with their nonexercised peers. Experimentally, these consequences are important when relating experimental data to body mass (e.g., muscle/body mass; 280). For additional information about restriction/reward protocols, refer to Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research (342a).

An expanding paradigm in exercise science is strength training with applications to rehabilitation therapy and in particular retention of muscle mass with advanced aging. Muscle hypertrophy is usually achieved through progressive resistance training often using weights (280) and has been induced in multiple animal species by resistance training (weight lifting in conscious animals), muscle(s) electrical stimulation (in anesthetized animals), compensatory overload induced by tenotomy or by surgical ablation of synergistic muscles, imposition of chronic stretch via weight application or casting, and wheel running with high resistance (196, 280, 441).

Surgery Performed Under Anesthesia

As with all protocols, surgery must be justified and performed under anesthesia and needs to include regimens for postsurgical analgesia and monitoring. Omitting analgesia for procedures that would normally be deemed painful for humans requires scientific justification that includes literature citations, if available. Personnel who will provide nursing care should be identified, and a schedule of observation and/or treatment should be explicitly developed.

The standard regulatory benchmark for the use of anesthesia and postsurgical analgesics is the analogous human condition. Thus, if a human patient would request or receive analgesia after a similar procedure, the animal should receive such. For animal survival surgery, the PI must provide appropriate postoperative analgesia as determined by the facility veterinarian unless omission is justified for scientific reasons and approved by the IACUC. Analgesic regimens must be fully detailed in the methods section of resulting publications. Where analgesics cannot be used for scientific reasons, the rationale or justification must be compelling and clearly described with pertinent literature citations. Importantly, the PI must specify the duration between surgery and initiation of the exercise protocol based on demonstrating adequate recovery (see immediately below).

Impact of Surgery/Anesthesia and Euthanasia on Exercise-Related Measurements

Excision of tissue via biopsy or surgical instrumentation is often essential to collect physiological and biochemical data from exercising animals. Such procedures mandate careful selection of anesthesia and instrumentation and especially allowing for adequate recovery before initiating/resuming exercise studies. For instance, liver and muscle glycogen are key metabolic substrates for exercise; yet aortic catheterization under halothane anesthesia reduces liver glycogen by over 50%, and it takes from 2 to 8 days to recover (320). This substantial interanimal variability in recovery times often mandates assessment of recovery in individual animals, which may be predicated on reestablishing a normal food intake relative to body mass (263, 320) and/or the return of the animal’s weight to presurgical levels (57, 123). In addition, it may take as long as 3 days in rats and as long as 7 days in mice to reestablish their normal circadian patterns of activity and/or their diurnal variability in blood pressure (57, 320). It should be noted that Flaim et al. (119) have demonstrated in rats that cardiac or circulatory dynamics, regional blood flow, arterial blood gases, and acid-base status remained unchanged during a 1–6-h recovery period following halothane anesthesia. Furthermore, the values measured at rest over this period of recovery by Flaim et al. (119) were similar to those measured in chronically instrumented counterparts (14, 119, 123, 140, 326, 334, 336, 337). In contrast to that demonstrated by Flaim et al. (119), methoxyflurane anesthesia of mice destabilizes heart rate and other cardiovascular and metabolic variables for between 6 and 12 h and 2,2,2-tribromoethanol for over 24 h (90). Moreover, acute instrumentation can produce a significant reduction in body mass and V̇o2max (123, 140, 141, 171) such that, insofar as possible, the recovery period should not be terminated until an animal has returned to within 10% of its presurgical body mass.

In rats, pentobarbital anesthesia confounds the effects of exercise on acid-base status, whereas euthanasia via decapitation negates exercise-induced changes in muscle metabolites (124). Pentobarbital administered before heart excision, compared with isoflurane and sevoflurane, in an ex vivo working heart model, increases lactate levels and impacts function and stabilization during reperfusion (347). By contrast, enflurane increases the lactate-to-pyruvate ratio in rat hearts and livers during hemorrhage compared with pentobarbital or isoflurane anesthesia (217).

Records

Effective record keeping helps ensure animal care and regulatory compliance and is intrinsic to good science. Whereas some exercise regimens such as high-intensity treadmill training bouts require that an animal’s performance be documented each training session, voluntary wheel running, for example, may not. However, documenting the duration, distance, and intensity on a daily schedule allows the investigator to detect problems with the equipment, the animal, or the environment that can be rapidly addressed. For automated animal exercise equipment that utilizes aversive stimuli, such as mild electric shocks to maintain performance, recording the frequency/number of shocks applied during exercise is an important component of animal monitoring: acute or chronic alterations in administered shock frequency can indicate impending exhaustion, sickness, injury, or equipment problems. The need for aversive stimuli as well as their intensity and frequency will depend on the study design in concert with specific experimental goals. Scientific requirements such as high-intensity exercise, exercise to a predetermined targeted physiological change such as exhaustion, or exercise in obese/sedentary animals may require more frequent stimulation. IACUCs, PIs, and veterinarians must collaboratively review specific protocols to set an acceptable limit for application of aversive stimuli.

Because of the importance of developing effective therapeutic strategies for exercise intolerance in human patient populations, exhaustion is a very valuable end point in animal research. However, end points must be well defined and clearly established. These may entail observation of specific behaviors, circumstances, and/or physiological markers that indicate exercise termination by the investigator. Accurate records of test conditions and of performance are crucial and permit day-to-day adjustment of test parameters dependent on each animal’s performance.

Health Problems

PIs must provide criteria for temporary or permanent removal of animals from a study because of health problems. These include changes in demeanor or willingness to exercise. Common signs of pain, illness, or distress include irritability, decreased appetite, weight loss, reduced spontaneous activity, guarding specific body regions, abnormal posture or gait, porphyrin rings around eyes, and changes in bowel or bladder habits. Decreased body temperature, weak pulse, or reduced or very rapid ventilation are signs of more serious health problems and mandate seeking veterinary evaluation. These criteria can mitigate temporary or permanent removal from the study, which is an essential aspect of quality control and fundamental to scientific rigor and reproducibility. PIs, IACUCs, and veterinarians should be creative, flexible, and compassionate in developing these criteria. Devices that are used for exercising multiple animals, some of which may be immunocompromised by the experimental protocol or disease being investigated, should be appropriately sanitized between animals to negate their providing a locus for infectious disease transmission.

Stopping an Exercise Session

Definition of a humane end point for exhausting exercise is a major responsibility of the PI and IACUC and must be specified and approved in the animal use protocol. Moreover, there are multiple reasons for stopping an exercise session prematurely, which include accidental injury (often damaged toenails in murines; judicious use of an inclined treadmill, which produces higher metabolic rates at slower speeds, is useful for reducing toenail damage), premature exhaustion, innappropriately elevated rectal/core temperature, adverse effects, behavioral issues, and poor performance resulting from the animal’s unwillingness to exercise.

Removal of an Animal from an Exercise Study

Animals that are trained and conditioned for exercise studies are extremely valuable. However, infectious disease and trauma can necessitate temporary or permanent removal from an exercise study. The protocol must specify the circumstances for removal and what criteria must be met for their return to the study. The requirement for excessive motivation to exercise via aversive stimuli mitigates removal from a study.

Animal Reuse

In some circumstances, euthanasia of instrumented and trained animals, especially large animals such as dogs, horses, or cattle, may not be necessary at the end of a study. Depending on the condition and prior use of these animals, use in subsequent studies is permissible and indicated. Reuse that requires additional (i.e., multiple) major survival surgeries requires specific justification and IACUC approval.

SELECTION OF ANIMAL MODEL

Over and above the advantages of animal models presented in the why are exercise studies relevant? vide supra, the investigator must ask themselves a battery of questions when selecting the best animal exercise model for themselves. First and foremost, if their preparation requires conscious “voluntary” running, which species can and will perform the criterion exercise bouts required for testing and/or training? Can the required measurements be made during and following exercise? Are the data transferable to humans? Is the required disease model available in this species? Sometimes, and especially in the case of genetic knockout models, the investigator is limited to a single species (i.e., mouse) and has to adapt or redesign exercise challenges from other species. One example of this would be assessing the performance impact of removing myoglobin from the heart and skeletal muscles. Garry et al. developed an exercise test where the performance criterion was how many times the animals lagged back on the treadmill belt and broke an arbitrary line positioned at the rear of the treadmill in close proximity to the electric grid (134). The strength of their conclusions, that lack of myoglobin did not negatively affect exercise performance, is only as rigorous as the criterion exercise test itself. Notably in this instance, Billat and colleagues (20, 37) have subsequently demonstrated that determination of CS-D′ and also V̇o2max are feasible on the motorized treadmill in multiple strains of mice.

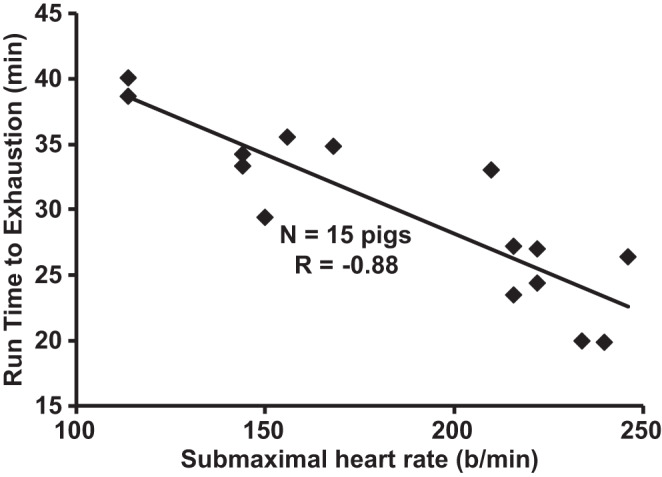

Tipton usefully categorized different species with respect to what aspects of cardiovascular function they may best help investigate, noting that there was a marked paucity of studies, at that time, that had measured V̇o2max, cardiac output (Q̇), and arterial-venous difference (a-vO2diff) simultaneously (442). Specifically, mongrel dogs and rats display proportional changes in Q̇, stroke volume, and a-vO2diff closely akin to those seen in humans despite dog and rat body mass-specific V̇o2max values being far higher than those of their typical human counterparts. Interestingly, the effect of exercise training on the balance between perfusive and diffusive O2 conductances is such that foxhounds increase V̇o2max solely via enhanced Q̇ without elevating a-vO2diff (327). The typical human response is to increase muscle diffusional more than perfusional O2 conductance such that both elevated Q̇ and a-vO2diff contribute to the increased V̇o2max (389). Thus, the foxhound may be valuable for understanding O2 transport limitations in humans who are O2 extraction limited [e.g., healthy aged (303, 304) and patients with mitochondrial myopathy (380)]. The exercising horse and, to a certain extent, the dog (especially the greyhound) have muscular spleens that increase blood O2 carrying capacity during exercise and Q̇ values so high that pulmonary capillary transit times for red blood cells become limiting and exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia and hypercapnia become manifest. Moreover, in both horses and dogs the combination of high intrapulmonary capillary pressure (positive) and very low (negative) alveolar pressures summates across the extremely thin blood-gas barrier causing pulmonary capillary stress failure, leading to exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage (EIPH), occasional overt epistaxis, and inevitably long-term lung remodeling (369). The most common species for investigations identified with “physical exercise,” in order of usage (PubMed, June 2019), are as follows: rat (no. 1: 18,875 articles), mouse (no. 2: 10,869 articles), horse (no. 3: 4,096 articles), fish (no. 4: 3,929 articles), dog (no. 5: 3,679 articles), birds (no. 6: 974 articles), pig (no. 7: 867 articles), rabbit (no. 8: 672 articles), cow/cattle (no. 9: 647 articles), cetacean (no. 10: 242 articles), goat (no. 11: 159 articles), camel (no. 12: 37 articles), and pinniped (no. 13: 12 articles).

Exercise Modalities in Rats

Motorized treadmill.

advantages and disadvantages of treadmill exercise.

To investigate physiological, biochemical, behavioral, and, increasingly, molecular responses to acute and chronic (i.e., training) exercise, the treadmill has been the modality of choice. A variety of species have been successfully studied using treadmill running including horses (369, 370, 373, 375, 455), dogs (38, 154, 327, 330, 349), pigs (13, 46, 256, 260, 429, 438), rabbits (92, 274, 275), cattle (218, 410), ducks (226, 227), geese (113), and camels (238). However, the overwhelming choice for such studies has been the rat (Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research; 342a, 187). Notably, selective breeding in the laboratory has been utilized to select spectacularly for high V̇o2max and treadmill running endurance by Britton and colleagues (e.g., 415). In contrast with other exercise modalities, for instance, swimming or spontaneous wheel running, treadmill running in rats facilitates/permits calculation and setting of external work and work rate as well as intensity and duration (51). In addition, although breath-by-breath ventilation and gas exchange measurements are presently intractable in the rat, use of a specially designed metabolic chamber that fits into one lane on the treadmill (51) permits minute-by-minute V̇o2 measurement, and thus work rates can be set according to the rat’s V̇o2max or CS. Using these chambers, V̇o2, V̇co2, and other key exercise variables such as exercise efficiency can be measured (28, 50, 51). Running on the motorized treadmill increases the rat’s metabolic rate in a systematic and quantifiable fashion with respect to V̇o2max or CS and to the external workload (28, 50, 51, 334, 414, 423). Treadmill running imposes potent metabolic stress on the animal, requiring significant increases in O2 delivery to the contracting skeletal muscles in an intensity- and time-dependent manner (10, 12, 71, 211, 252, 253, 375). Akin to that seen in humans, treadmill exercise training elevates the rat’s V̇o2max promoting an array of structural and functional adaptations centrally within the cardiovascular system (increased blood volume, ventricular dimensions, and stroke volume) and peripherally (increased vascular bed, more sensitive vascular control, higher blood flow and microvascular oxygen pressures during exercise, increased oxidative enzyme capacities, faster V̇o2 kinetics, and greater capacity for fat vs. carbohydrate as energetic substrate; 11, 24, 28, 60, 99, 117, 141, 149, 172, 174, 178, 179, 322, 337, 338, 415, 472), all of which are associated with large increases in endurance capacity (80, 247).

Another major advantage of using the rat to study exercise responses and capacity is the degree of instrumentation that is possible. Arterial catheterization studies have permitted determination of cardiovascular function, and using radioactive, colored, or fluorescent microspheres, regional, organ, and muscle(s) blood flow responses to exercise have been resolved to a level not possible in humans (10, 89, 175, 241, 252, 255, 337, 419, 420). This technique has also been used successfully in dogs (150, 327, 330–332), equids (ponies and horses; 15, 288, 358), and pigs (13, 297) running on the motor-driven treadmill. An additional major advantage of the rat is the development of disease models with substantial applicability to humans. These include heart failure (173, 174, 328, 333, 339, 371, 374), diabetes [Type I (29, 232) and Type II (72, 354, 355)], hypertension (48, 294), and pulmonary hypertension (52, 53). In these, and many additional human disease analogs (240), the rat is helping unravel physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms underlying the mechanistic bases for exercise intolerance and increased morbidity/mortality.

Notwithstanding the above, the treadmill exercise mode in the rat is not without its challenges. These include the following: 1) The forced nature of the activity and common requirement for noxious stimuli, most commonly bursts of high-pressure air or electric shock, delivered via prod or grid, for motivation constitute one challenge. The electric shock must be intense enough to provide an incentive to run (10–30 V, 0.5 A) but must not harm the animal. Excessive electric shocks have been defined as >4 per minute and indicate that the exercise intensity should be decreased or that the animal should be removed from the study. As well as high-pressure air, which cannot be used in conjunction with metabolic measurements (V̇o2 and V̇co2), other effective nonnoxious stimuli include the sweeping use of a bottle brush on the tail and also the rattling of keys on the plastic manifold of the treadmill lanes. 2) Running pattern, especially at slow speeds, may be more “stop-and-go” than the continuous movement at close to constant speed desired. This behavior tends to decrease with conditioning. 3) Expense of commercial treadmills and sometimes lack of flexibility for speeds (ideally up to 120 m/min to facilitate high-intensity sprint training, as desired) and a range of inclines/declines are another challenge. Rats can run up inclines of 30° (35% grade; 28, 472, 473) and down declines of 16° (9, 211, 212). 4) Treadmill surface can be problematic. The belt must facilitate good traction (396) while being nonporous (easy to disinfect) and sufficiently soft to minimize toenail and foot problems incurred by daily training. Treadmill lanes typically range from 39 cm (28) up to 70 cm with the longer lanes minimizing contact with the electric grid especially during high-intensity training (472).

conditioning rats to run on the treadmill.

Up to 10% of rats from commercial vendors may refuse to walk or run and must be eliminated from exercise studies (28, 99, 199, 239). To minimize this loss and help rats become proficient runners and reduce foot injuries, they should be familiarized to treadmill exercise gradually. Adequate conditioning, often in bouts as short as 5 min at varying speeds, helps ensure that rats become proficient runners and generally takes between 5 and 14 days (60, 164). The frequency and duration of these sessions must be gauged carefully to avoid training effects such as heat shock protein responses or increased muscle oxidative enzymes or V̇o2max (24, 99, 314). Some investigators have found that positive reinforcement using chocolate (0.5 g) as a reward after the exercise session resulted in rats jumping eagerly out of their cages onto the treadmill, avoiding compliance problems entirely and decreasing the necessity for electric shock encouragement (472). Given institutional restrictions regarding food in laboratories, this important exercise incentive should be mentioned in the application. Foot injuries incurred, usually during running, may require veterinary treatment and temporary removal from training to allow recovery.

Measurements of exercise performance on the treadmill in the rat.

Although tests of “fitness” in rats and other animals have often considered V̇o2max and endurance capacity to be synonymous, as justified under exercise testing and training in humans and animals they clearly are not, with each displaying different weighting of central (cardiovascular O2 transport) and peripheral (i.e., muscle; muscle O2 transport, O2 utilization, mitochondrial oxidative capacity, and substrate selection/availability) capacities.

measurement of V̇o2max in the rat.

For rats running on a motorized treadmill, V̇o2max is normally defined as the point at which V̇o2 does not increase additionally, even though further increases in external workload are imposed on the animal (414). As with humans, a progressive ramp or incremental exercise test can be used to meet this criterion allowing for sufficient exercising time that the expired gas concentrations (O2 and CO2) measured in the metabolic chamber have stabilized at their appropriate levels (51, 140, 334, 472). Again, akin to exercise-conditioned young healthy humans (87, 372), even when a distinct V̇o2 plateau is not evident, the rat’s peak V̇o2 response may not be different from the V̇o2max measured using more strictly defined criteria (28, 117). A validation bout at a faster speed than achieved on the incremental test has been implemented for rats using an abbreviated maximal exercise test 48 h after the initial exercise test (163), which ensures that a true V̇o2max is measured for each animal and serves to minimize the opportunity for exhaustion to prevent V̇o2max being achieved (Fig. 3). The latter test also reduces the possibility for other environmental factors such as high ambient temperatures to negatively impact the rat’s running ability. The importance of a validation bout, in the absence of a defined V̇o2 versus speed/work rate plateau, is likely to be of greater importance in aged and/or disease models where a complex array of factors not related directly to the O2 transport-utilization system may cause the animal to stop running (372).

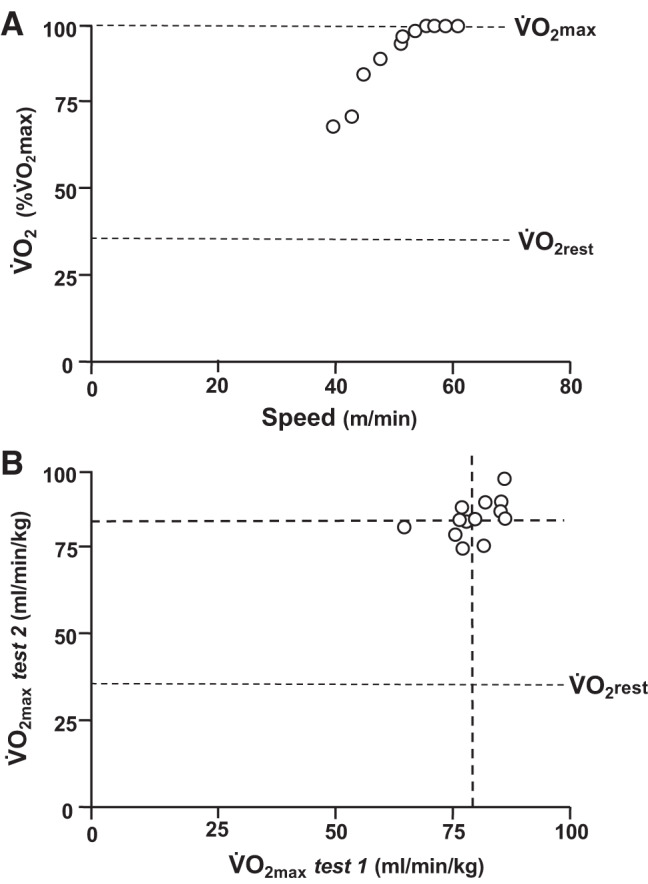

Fig. 3.

A: maximal exercise test in a male Sprague–Dawley rat demonstrating a distinctive plateau for oxygen uptake (V̇o2) vs. speed definitive for maximal V̇o2 (V̇o2max). V̇o2rest, resting V̇o2. B: individual male Sprague–Dawley rat V̇o2max values from 2 independent tests. Note very similar mean values (dashed lines) from tests 1 and 2, small range of V̇o2max values, and average within-rat coefficient of variation (CV) between tests 1 and 2 of 4 ± 1% (SE) supporting that these two measurements were highly reproducible with this CV falling within the expected measurement error for V̇o2max (71).

Acute instrumentation such as surgical insertion of cannulas into the carotid artery or jugular vein of the animal invariably compromises V̇o2max. Flaim et al. (119) demonstrated that performing the surgery with a short-acting inhalant anesthetic, such as halothane, results in resting cardiac or circulatory dynamics, regional blood flow, arterial blood gases, and acid-base status that remain unchanged during a 1–6-h recovery period with the values measured being similar to those measured in chronically instrumented counterparts (14, 119, 123, 140, 326, 334, 336, 337). Despite this stability in resting cardiac or circulatory dynamics, regional blood flow, arterial blood gases, and acid-base status, acute instrumentation does reduce V̇o2max (123, 140, 141, 171).

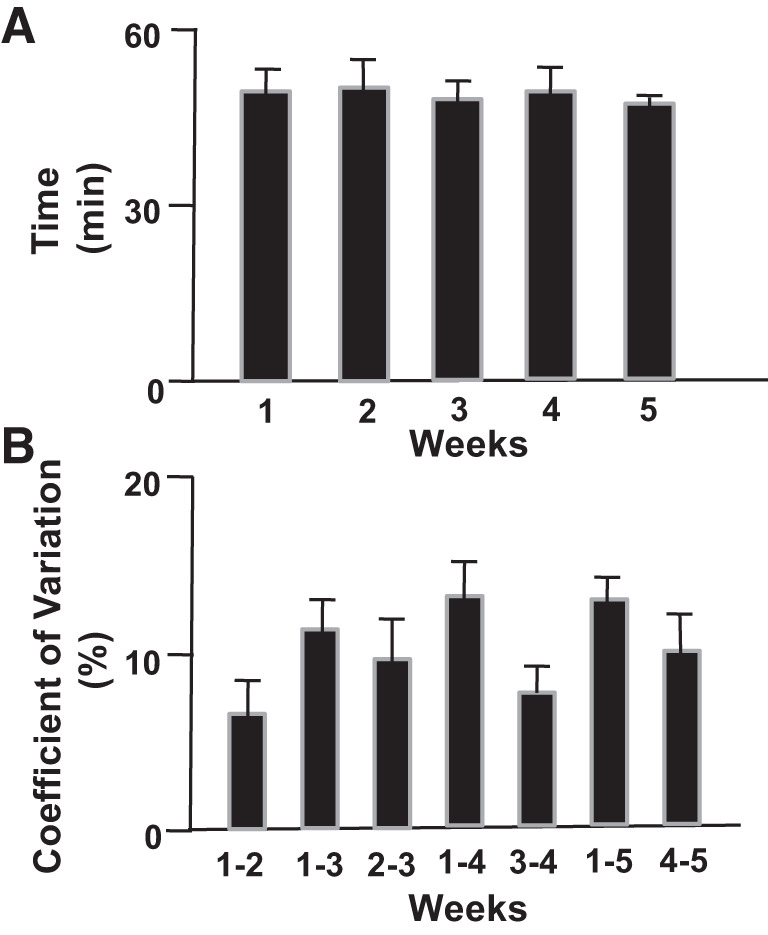

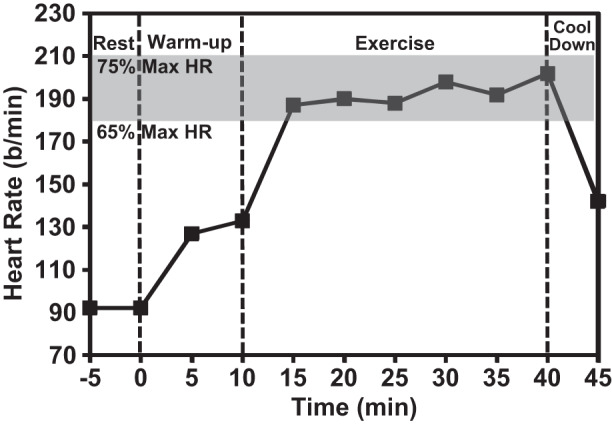

A typical progressive exercise test to measure V̇o2max/V̇o2peak utilizes the principles developed in the rat by Brooks and White (51) and Musch et al. (334). Specifically, each rat begins running at 25 m/min up a 10% grade for 2–3 min, which serves as warm-up and familiarization. Subsequently, the treadmill speed is increased to 40 m/min and then by 5–10 m/min each minute until exhaustion. For a cohort of 2–4-mo-old healthy male Sprague–Dawley rats the range of peak treadmill speeds was 46.4–78.9 m/min measured weekly for 5 consecutive weeks (71, 73). Primary criteria defining a successful test were observation of a change in gait immediately preceding termination and/or no further increase of V̇o2. Given the inability of an arbitrary respiratory exchange ratio (RER) value to confirm V̇o2max in humans (378), an RER >1.0 was taken as an ancillary measure of V̇o2max only in the presence of a gait change or V̇o2 plateau (28). These tests typically are of <8-min duration with the majority demonstrating a distinct V̇o2 plateau at 75.7–80.1 mL O2·min−1·kg−1 (71). Using this procedure over 5 consecutive weeks, absolute V̇o2max increased at weeks 2 and 5 in concert with greater body mass, whereas relative V̇o2max was unchanged for weeks 1–3 but decreased slightly thereafter (Fig. 4). Remarkably, there were no differences in the mean within-rat coefficient of variation among consecutive tests (range 3–4%). It is pertinent that Høydal et al. (187) found a more consistent V̇O2 plateau at 25° incline for rats and mice.

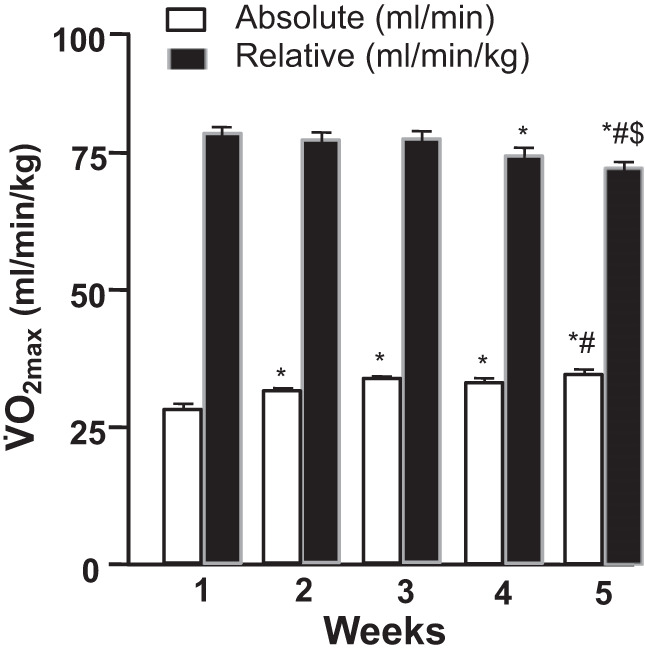

Fig. 4.

Mean maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2max; n = 13 male Sprague–Dawley rats) across 5 maximal exercise tests plotted as absolute and relative values (means ± SE; *P < 0.05 vs. test 1, #P < 0.05 vs. test 2, $P < 0.05 vs. test 3; 71).

measurement of endurance capacity in the rat.

The endurance capacity of the rat is measured typically by requiring the animal to run at some submaximal speed/work rate until fatigue or, more correctly, exhaustion ensues. Exhaustion is defined operationally as the inability to keep pace with the treadmill (126, 163, 394, 456, 472). With time at a given speed the animal’s running style changes, and a gradual lowering of the hind haunches becomes apparent as fatigue develops. When the rat is unable to keep pace with the treadmill, even after repeated application of aversive stimuli, the investigator should discontinue the test. Exhaustion is confirmed by placing the rat on its back and observing evidence for a diminished or absent righting reflex (64, 125, 163, 296).

As with humans, rat endurance capacity relates to liver and skeletal muscle glycogen content (64, 70), and because these fluctuate diurnally (64, 70), controlling for the time of day at which endurance exercise tests are conducted is essential. Investigators should be aware that food deprivation significantly compromises liver and skeletal muscle glycogen concentrations with 24 h of fasting decreasing muscle glycogen concentrations by 30–40% and almost completely depleting liver glycogen (70, 461). Therefore, testing in the fed or fasted state will impact the rat’s exercise performance as will chronic instrumentation insofar as they decrease liver and muscle glycogen. Specifically, Moore et al. (320) demonstrated that instrumentation with an aortic cannula decreased both liver and diaphragm glycogen concentrations, which remained depressed until the food intake was reestablished at presurgical levels. Because of the great importance of food intake in glycogen storage the rat’s food intake should be measured before and after surgery with endurance exercise tests delayed pending reattainment of presurgical levels.

Unlike humans and horses, rats do not sweat to regulate body temperature. Exercise performance of the rat is compromised by hot environments, where the total thermal load precludes the rat achieving thermal balance, compared with either thermoneutral (ideally 20–22°C) or cold environments (125, 126, 394, 413). Thus, rats running in hot environments increase both body core and hypothalamic temperatures to the point of exercise intolerance (126, 456). It is therefore incumbent on the investigator to ensure that exercise tests are performed in a thermoneutral environment (379). In this regard, an electric fan placed in front of the rat helps dissipate body heat.

Rigorous adherence to these sources of experimental variability can ensure that tests of exercise capacity and also V̇o2max are highly reproducible across time for up to at least 5 wk despite the increased mass of the rat (71). Thus, Copp et al. (71) utilized a graded exercise tolerance test in male Sprague–Dawley rats (age 2–4 mo) that exhausted the animals in 45.9–52.1 min with consecutive weekly coefficients of variability in endurance capacity in the 6–10% range (Fig. 5). This protocol consists of starting the rat at 25 m/min up a 10% grade for 15 min and subsequently increasing the speed by 5 m/min every 15 min until exhaustion. This protocol has been demonstrated to effectively deplete muscle glycogen stores and elicit an objective index of exhaustion (335, 336).

Fig. 5.

A: average run time to exhaustion (means ± SE) among a cohort of 13 healthy male Sprague–Dawley rats during 5 separate exercise tolerance tests for determination of endurance capacity over successive weeks. B: within-rat coefficient of variation (n = 13 rats) among an increasing number of exercise tolerance (endurance capacity) tests over successive weeks (71).

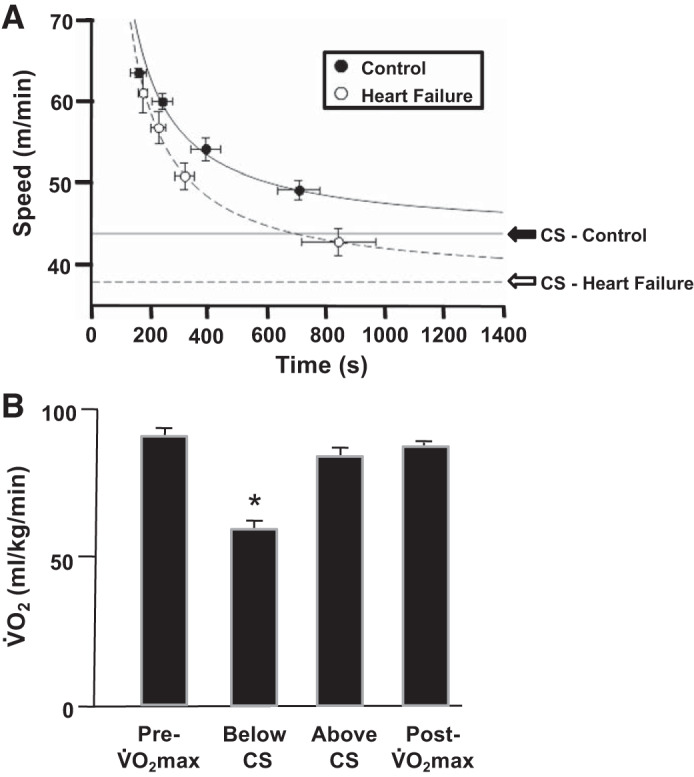

Copp et al. (73) demonstrated that the CS relationship could be determined in the rat during treadmill exercise. CS was measured via up to five constant-speed runs, performed on separate days, that resulted in exhaustion within 150–500 s (Fig. 6). In rats, as for humans, CS constitutes a crucial performance and metabolic demarcator, below which V̇o2 stabilizes at submaximal values and exercise of a sustained duration is possible. In marked contrast, above CS, V̇o2 rises systematically to V̇o2max, and exhaustion occurs rapidly at a time closely predicted by the CS-D′ parameters of the speed-duration relationship (Fig. 6). These investigators subsequently utilized the CS concept to demonstrate that neuronal nitric oxide synthase plays a major role in regulating muscle(s) blood flow and vascular conductance during severe-intensity (i.e., above CS) but not heavy-intensity (below CS) exercise (74). Moreover, as mentioned previously, a singular advantage of the CS concept is that relating a running bout to CS allows direct comparisons to be made across investigations, which is a huge advantage for judging relative therapeutic efficacy (465). To this end, Craig et al. have demonstrated that CS can be established in rats with HF (76).

Fig. 6.

A: hyperbolic models for control (●) and heart failure (HF, ○) female Sprague–Dawley rats (means ± SE). Critical speed (CS) was substantially reduced [indicated by the downward shift of the asymptote, CS, from healthy (solid line) to HF (dashed line)]. Parameter D′ (expression of energy stores component when running as distance, as defined previously in Figure 2) was not impacted by heart failure (76). B: demonstration that CS in the male Sprague–Dawley rat, as for humans (367, 376), does indeed represent the demarcator between the heavy-intensity [oxygen uptake (V̇o2) steady state below maximal V̇o2 (V̇o2max) achieved] and severe-intensity (V̇o2 rises to V̇o2max) domains of exercise (73). Notice that below CS, end-exercise V̇o2 falls significantly below V̇o2max (*P < 0.05), whereas above CS it does not. V̇o2 values are means ± SE.

Wheel running.

advantages and disadvantages of wheel running.

Spontaneous or voluntary running wheels for rats are typically ~1 m in circumference (32–34 cm in diameter) and most commonly made of stainless steel (195). A great advantage of this modality is that the exercise training requires only minimal investigator intervention, does not require aversive stimuli (e.g., electric shocks or air jets) to motivate the animals to run in the wheels, and allows rats to run during the night congruent with their normal active phase. Another compelling reason for selecting this exercise modality is that it offers a low-time investment intervention facilitating long-term investigation of increased physical activity in rodents, which is especially valuable for aging studies (180, 182, 183). Also, in contrast to swimming, in the rat, wheel running does not induce chronic stress as gauged by hypertrophy of the adrenal gland or increased catecholamine content in the left ventricle of the heart (397). However, there is the potential for substantial hypertrophy of hind limb muscles and myocardium, especially in young rats (165–167, 324, 390–392, 397). This is a response not typically observed in most endurance-based treadmill-running investigations and may be either advantageous if the adaptive mechanisms are being investigated or a potential confound contraindicating selection of this training method.

The major disadvantage of wheel running is that regulation of the duration or intensity of the running behavior is challenging although it can be influenced by creative strategies such as dietary interventions (e.g., food restriction; 181, 325) or using variable-resistance wheels. Generally, the animal is in control of the quantity, intensity, and timing of its running behavior, which may be extremely erratic and vary enormously among animals. For instance, spontaneous running varied from 4 to 74 km/wk in a cohort of young healthy male Sprague–Dawley rats (412). Despite these limitations, many physiological and pathophysiological adaptive responses to exercise of cardiovascular, endocrine and metabolic, neuromuscular, neurological, and immunologic variables have been investigated using wheel running. However, this modality is not effective for studies requiring the animals to exercise until fatigue or exhaustion ensues because running rarely lasts longer than 2 min at a time and concludes well before those desired end points. Thus, assessments of “exercise capacity” based on daily wheel-running distances are extremely problematic. With regard to training adaptations, voluntary wheel running does induce elevations in V̇o2max in normal (152, 165, 247, 480) and hypertensive (234, 352) rodent models. Also, within a healthy cohort the most active animals evince the highest locomotory muscle(s) oxidative enzyme activities and vascular transport capacities (412).

Measurements of exercise amount during wheel running in the rat.

Investigators choosing wheel running for an exercise model should measure the total daily distance run by each animal by recording the revolutions completed in each 24-h period, with an attached revolution counter, to calculate the distance run based on the wheel’s circumference. The majority of running generally occurs during the early part of the 12-12-h dark-light cycle in 100–200 bouts of 40–90 s each (319, 390). Wheel odometer records should be documented ideally at the same time each day close to the end of that day’s dark cycle. With implementation of external monitoring devices, the investigator can measure the speed and duration of each individual running bout and thereby estimate exercise intensity (319, 352, 390).

Upon availability of a running wheel an adaptation period of 2–4 wk is evident before the rat’s maximal running activity plateaus (152, 165–167, 177, 318, 390, 393) for several weeks and then steadily declines with advancing age (152, 181, 319, 352). Animals typically stratify themselves into groups attaining high (18–20 km/day), intermediate (6–9 km/day), and low (2–5 km/day) running distances (165, 166, 177, 319, 390). Minimally acceptable running distances have been arbitrarily set with a cutoff value of 2 km/day (165, 318, 390).

If rats are provided adjustable resistance wheels, the amount and rate of work can be measured by calibrating the resistance to rotation of the wheel and measuring revolutions. Running distance decreases above some critical resistance, and as mentioned above, these wheels can induce leg muscle hypertrophy, to a degree that may not occur with freely rotating wheels (195).

As for treadmill exercise, the environmental conditions in which the animals run must be carefully regulated. The distance run is impacted by many variables including 1) the amount of light exposure such that animals housed on the top or bottom shelf of the animal rack are impacted differently, 2) activity of neighboring animals, 3) estrus cycle of female rats, and 4) age. As above, running distances decrease by over 75% through maturation and old age (180, 319).

As with treadmill running, wheel running in rats may break toenails and/or develop hind paw abrasions especially during the first few weeks. Investigators should ensure that toenails are either clipped or protected with a strong adhesive. Paw injuries lasting more than a few days, irrespective of running activity, indicate veterinary evaluation and a brief hiatus (4–7 days) from running for recovery.

Voluntary wheel running may not be appropriate for animals with massive central obesity (e.g., obese Zucker rat) as anecdotal evidence suggests that their spontaneous running activity is very low. However, it is effective for other disease models including hypertension (352, 397) and insulin resistance (155, 342, 366, 482) and induces substantial increases in V̇o2max, as assessed during an incremental treadmill test, in normal (152, 165, 247, 480) and hypertensive (234, 352) rats.

Swimming.

advantages and disadvantages of swimming.

Most terrestrial animals have the innate ability to swim, and thus, although this section focuses primarily on rats, many of the issues presented can be applied to other animal species. Swimming has been the exercise modality of choice across a spectrum of behavioral and exercise studies as reviewed by Dawson and Horvath (84). Rats can swim in nonturbulent isothermal water for as long as 60 h (388). Swimming exercise studies have identified key physiological, biochemical, and molecular responses to acute and chronic exercise (21, 190, 204) and require less expensive and more rudimentary equipment than either treadmill or wheel running. However, the investigator must select carefully the container, water depth, and temperature in which the rats will swim. When applied appropriately, swimming has the potential to provide a more continuous and uniform exercise profile than the stop-and-go pattern that characterizes wheel and, sometimes, treadmill running and avoids foot injuries.

Continuous swimming involves repetitive cycling of the rat’s forelimbs and hind limbs at a rate similar to treadmill running (145, 198, 254), while maintaining its snout above the water. However, ankle and leg extensor muscles are less heavily involved than during running, whereas the ankle and leg flexors are preferentially recruited during swimming (254). Moreover, swimming induces a greater range of motion for both knee and ankle joints compared with running (145). As a result, different muscle recruitment patterns likely affect the effort and intensity of exercise performance. For swimming both the forepaws and hind paws remain submerged, and on occasion, the rat’s head may momentarily submerge. Whereas continuous swimming constitutes only moderate-intensity exercise, adding weight to the rat’s tail increases this to heavy- and even severe-intensity exercise. Rats should not become hypoxemic during continuous swimming (118, 136).

Distinct disadvantages of swimming include the following: 1) Some animals do not swim continuously but resort to diving or bobbing (22, 23, 91) behavior as escape or survival strategies invoked to avoid potential drowning. This behavior introduces intermittent hypoxia as an experimental confound and can be minimized by ensuring adequate water depth. Rats that swim continuously achieve a metabolic rate ~3 times that of resting [i.e., 3 metabolic equivalents (METs)], whereas rats that bob, spending as much as 60% of their time submerged and hypoxic (428), are at ~2 METs (23). It is clear that this type of activity should not be considered exercise. If, in a given rat, diving and bobbing behaviors cannot be eliminated, animals should be removed from the study. 2) Rats will seize any opportunity to avoid swimming such as floating, supporting themselves in corners, climbing out onto the side, or wedging their nails in any available crack. 3) Nonuniform swimming patterns include floating and climbing on one another. 4) Incorrect water temperature will impact swimming ability and metabolic responses.

To minimize these problems, the tank should be round with water deep enough to eliminate bobbing (≥50 cm; 22, 23, 118, 428) and have a vertical distance from waterline to the top of the tank sufficiently great to prevent the rats from extricating themselves from the water. In addition, the tank must provide a sufficient water surface area (~1,000–1,500 cm2 per rat) for the animals to swim (8, 75, 118, 254, 336, 428). Whether rats swim in tanks with clear or opaque sides does not appear to influence performance except that when the rats are swum to exhaustion, opaque sides reduce variability within and between animals (298). Rat swimming movements create water turbulence, which traps air bubbles in their fur increasing buoyancy (283). This process may be so effective that they fall asleep as they float in the water, and rats learn to do this so as to float with very little movement. V̇o2 measured in floating rats is close to that measured during resting conditions on a motorized treadmill and therefore represents a negligible exercise stressor. Consequently, to produce the required exercise pattern and metabolic stress, floating must be prevented. Effective counterstrategies include shaving them, adding a small amount of detergent to the animal’s fur or the water and agitating the water continuously (118, 298), and/or adding weight to the rat’s tail (see selection of animal model, Exercise Modalities in Rats, Measurements of exercise performance during swimming in the rat, below; 298).

Water temperature substantially impacts swimming performance in the rat (22, 23, 26, 54, 85, 86, 450): water warmer than the rat’s core temperature (i.e., 42°C or greater) induces hyperthermia and compromises performance greatly, even causing death (26). On the other hand, water significantly cooler than the rat’s core temperature (i.e., 20°C or lower) promotes hypothermia and also compromises performance (84) and, again, can kill the rat (26). Ideally, setting the water temperature slightly below the animal’s core temperature (specifically, between 33 and 36°C), allows the rat to maintain its core temperature for the duration of exercise (22, 23, 84). Crucially, this thermal range prevents temperature-related decrements in cardiovascular function (i.e., cardiac output, heart rate, and mean arterial pressure) that would influence exercise performance and metabolic regulation (84).

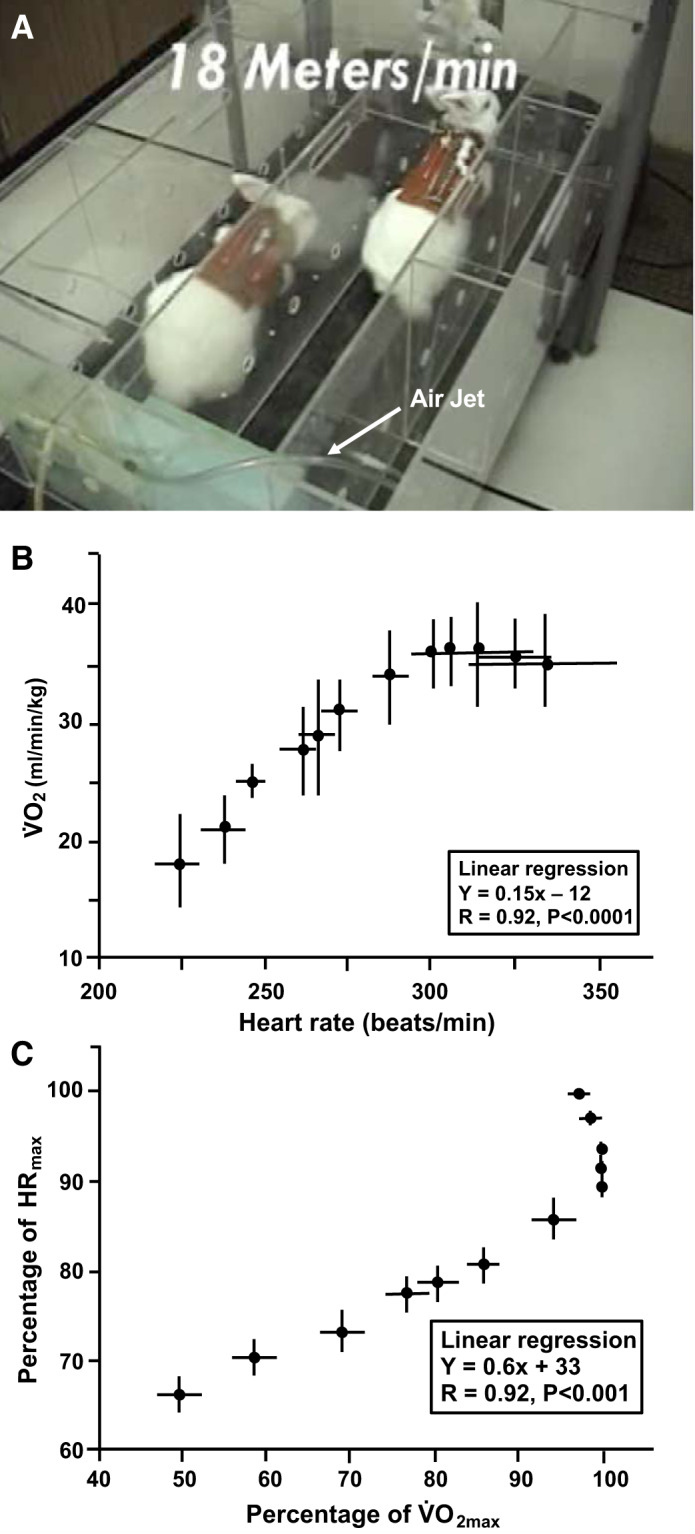

Although more challenging in the aquatic environment, as with treadmill running, and dependent on available technology, the metabolic stress of swimming rats can be defined relative to the maximal heart rate (HRmax) or V̇o2max. V̇o2 must be measured when rats are swimming continuously to provide an accurate measurement of metabolic rate.

A designated observer must be tasked to focus their complete attention on the swimming rats during the exercise testing or training period. Because of their high resting and exercising metabolic rate, rats can drown very quickly. Each observer must define rigorous and humane criteria for exercise session termination such as ~3 s submerged as distinct from bobbing. After swimming, animals must be dried and temporarily placed in a warm environment, such as under a heat lamp.

Measurements of exercise performance during swimming in the rat.

The unweighted continually swimming rat typically achieves a V̇o2 ranging from 46 to 63 mL·min−1·kg body mass−1 (i.e., ~3 METS; 8, 22, 23, 84, 298). For a young healthy rat with V̇o2max of 85–100 mL·min−1·kg−1, nonweighted swimming therefore constitutes a moderate intensity (~45–65% V̇o2; 8, 298, 336). To increase the exercise intensity, weight, relative to body mass, is placed most commonly on the tail (75, 118, 264). Importantly, the positioning of this weight is crucial, and it must not be sufficient to either submerge the animal or prohibit continuous swimming. For instance, a weight equal to 2% of the rat’s body weight attached ~5 cm from the end of its tail increases V̇o2 to ~81 mL·min−1·kg−1 (298) or 80–95% V̇o2max, corresponding to heavy- or severe-intensity exercise. By contrast, 4% of body weight attached at the base of the tail only increases V̇o2 up to 65–70% V̇o2max (336). Thus, placing the weight closer to the end of the tail appears to change swimming biomechanics reducing mechanical efficiency and elevating the V̇o2 cost.

Exercise training in the rat.

The three primary exercise modalities described above, treadmill running, wheel running, and swimming, have each been used for training rats (30, 84, 179, 405). The presence and extent of a training effect have been assessed primarily using one or more of the following criteria: 1) increases in V̇o2max, 2) increases in endurance capacity, 3) training-induced reductions in heart rate measured at rest and during submaximal exercise, 4) reductions in the blood lactate response during submaximal exercise, and 5) increases in skeletal muscle oxidative enzyme activities. Geenen and colleagues compared swim training to treadmill training and found that multiple training-induced cardiovascular and hormonal adaptations produced in the rat differed significantly (136). Notably, ventricular performance increased to a greater degree with swimming even though they attempted to match training workloads as a percentage of V̇o2max (404). Recently, Beleza et al. (30) compared the training-induced adaptations produced by high-intensity aerobic interval treadmill training (HIIT; 4 × 4-min bouts of exercise at 85–90% of V̇o2max interspersed by 2 min of recovery at 60% of V̇o2max) and free-wheel running. Whereas they identified both similarities and differences in the training-induced responses of peripheral skeletal muscles, it was evident that treadmill HIIT increased maximal exercise performance and reduced the blood lactate responses more compared with free-wheel running. These differential cardiovascular, skeletal muscle, and metabolic training responses across the three exercise modalities should be considered carefully as the experimental design is tailored to the scientific question(s) posed.

The impact of exercise training on the motorized treadmill has been assessed most rigorously with respect to relative exercise intensity (relative to V̇o2max) and duration (51, 99, 140, 141, 333). Training regimens have consisted of a variety of intensities and durations varying from moderate running of long duration (62–80% of V̇o2max, 60–120 min/day, 5–6 days/wk) up to high intensity and very short durations (105–116% of V̇o2max or greater, 5–6 repeated 1–2.5-min exercise bouts/day, 5–6 days/wk) termed high-intensity or sprint training (HIST; 80, 81, 99, 147, 148, 171, 257, 261, 411).

Over the last four to five decades these contrasting training paradigms (moderate prolonged continuous or high-intensity sprint training) have unveiled a broad spectrum of training-induced cardiovascular and metabolic adaptations and systems plasticity. One of the earliest studies examining the differences of endurance training versus high-intensity sprint training was performed by Davies et al. (80, 81). Ten weeks of endurance training (27 m/min, 15% grade, 120 min/day, 5 days/wk) increased V̇o2max 14% and endurance capacity 400%, with endurance, but not V̇o2max, being highly correlated with elevated skeletal muscle oxidative capacity. In comparison, a HIST regimen of 4 wk (5 × 1-min bouts of exercise at 97 m/min interspersed with 10 s of rest, 15% grade, 7 days/wk) increased V̇o2max 15% but did not improve either endurance capacity or skeletal muscle oxidative enzyme capacity (81). Using a nearly identical HIST regimen, Hilty et al. demonstrated that the increases in V̇o2max (↑19%) were produced by a higher maximal cardiac output (Q̇max) and maximal stroke volume (SVmax) in the absence of increased maximal arteriovenous O2 difference (i.e., fractional O2 extraction; 171) or muscle (soleus, plantaris, and white gastrocnemius) citrate synthase activities. Collectively, these studies support that high-intensity anaerobic sprint training regimens induce substantial central cardiac adaptations in the absence of the elevated peripheral skeletal muscle oxidative capacity evinced by endurance training regimens at least in the rat (80, 81, 99, 171, 179).

In the late 1980s, Laughlin and colleagues (257, 411) examined the effects of high-intensity interval training (HIIT; 6 × 2.5-min bouts of exercise at 60 m/min interspersed with 4.5 min of rest, 15% grade, 5 days/wk) on the vascular transport capacity of the rat’s hindquarter skeletal muscles along with the blood flow response of these muscles to a given level of treadmill exercise (15% grade, 60 m/min, ~116% of V̇o2max). Unlike the previous HIST, HIIT elevated succinate dehydrogenase activity in the white vastus intermedius and white vastus lateralis muscles and increased total hindquarter skeletal muscle blood flow capacity during supramaximal exercise via fast-twitch glycolytic muscle vascular adaptations of the white gastrocnemius and white vastus lateralis that included a greater capillarity (147). Collectively, the available literature [see review by Laughlin and Roseguini (261)] supports that HIIT increases the blood flow capacity in skeletal muscles with adaptations occurring primarily in fast-twitch glycolytic muscle.

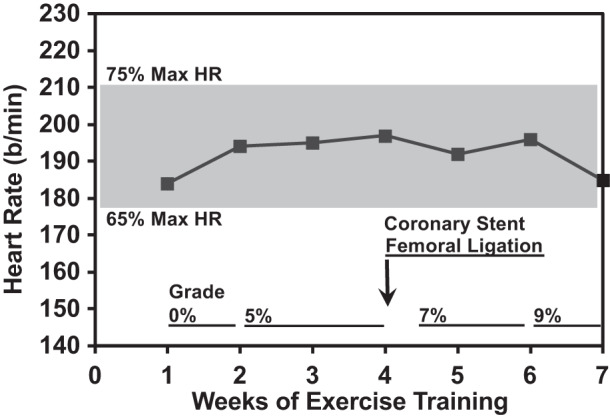

In 2001, Wisløff et al. (472) developed a HIIT regimen where the rats ran 4 × 8-min bouts, instead of the 4 × 4-min bouts used by Beleza et al. (30), at 85–90% of V̇o2max separated by 2 min of recovery at 50–60% of V̇o2max. The unique and important aspect of Wisløff and colleagues’ design was institution of weekly V̇o2max measurement and adjusting running speed accordingly such that all rats trained at 85–90% of V̇o2max throughout the entire training program. This new training regimen has produced the largest increases of V̇o2max (60–70% in both male and female rats) found to date as well as adaptations in the heart and peripheral circulation of both healthy rats and rats suffering from heart failure (HF; 220, 221, 322, 407, 472, 473). In HF rats with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) produced by myocardial infarction, Wisløff and colleagues used their new HIIT program to increase V̇o2max ~50% concomitant with multiple cardiac adaptations including increases in contractile function and positive changes in myocyte morphology and excitation-contraction coupling (222, 474, 476). Whereas previous studies demonstrated that HIST produces similar cardiac adaptations in HFrEF rats (340, 472, 473, 484–486), Wisløff et al.’s HIIT regimen also incurs beneficial adaptations in skeletal muscle metabolism and the peripheral vasculature (322, 407), whereas HIST does not (81, 340, 484–486). Accordingly, HIIT has distinct and compelling advantages over previous HIST and also moderate-intensity endurance-type training regimens. Crucially, these HIIT advantages have translated effectively to training humans with HF (6, 475, 476). Because V̇o2max is, perhaps, the best prognostic marker for mortality and morbidity in HF (224, 287, 459, 460), HIIT may be one of the best and most important therapeutic interventions for candidate patients with HF.

Exercise Modalities in Mice