Abstract

Introduction

Shuanghuanglian (SHL) oral liquid is a well-known traditional Chinese medicine preparation administered for respiratory tract infections in China. However, the underlying pharmacological mechanisms remain unclear. The present study aims to determine the potential pharmacological mechanisms of SHL oral liquid based on network pharmacology.

Methods

A network pharmacology-based strategy including collection and analysis of putative compounds and target genes, network construction, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway, and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment, identification of key compounds and target genes, and molecule docking was performed in this study.

Results

A total of 82 bioactive compounds and 226 putative target genes of SHL oral liquid were collected. Of note, 28 hub target genes including 4 major hub target genes: estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1), nuclear receptor coactivator 2 (NCOA2), nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (NCOA1), androgen receptor (AR) and 5 key compounds (quercetin, luteolin, baicalein, kaempferol and wogonin) were identified based on network analysis. The hub target genes mainly enriched in pathways including PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, human cytomegalovirus infection, and human papillomavirus infection, which could be the underlying pharmacological mechanisms of SHL oral liquid for treating diseases. Moreover, the key compounds had great molecule docking binding affinity with the major hub target genes.

Conclusion

Using network pharmacology analysis, SHL oral liquid was found to contain anti-virus, anti-inflammatory, and “multi-compounds and multi-targets” with therapeutic actions. These findings may provide a valuable direction for further clinical application and research.

Abbreviations: SHL oral liquid, Shuanghuanglian oral liquid; JYH, Jinyinhua, Flos Lonicerae; HQ, Huangqin, Radix Scutellariae; LQ, Lianqiao, Fructus Forsythiae; CFDA, The China Food and Drug Administration; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; TCMSP, Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology database; CAS, Chemical abstracts service number; SMILES, Simplified molecular input line entry specification; OB, oral bioavailability; DL, drug-likeness; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; HCV, human cytomegalovirus; NO, nitric oxide; COX, cyclooxygenases; ESR1, estrogen receptor 1; NCOA2, nuclear receptor coactivator 2; NCOA1, nuclear receptor coactivator 1; AR, androgen receptor; AM, alveolar macrophages; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; HCMV, Human cytomegalovirus; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; HPV, Human papillomavirus; COX-2, cyclooxygenase; PG, prostaglandin; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology

Keywords: Shuanghuanglian oral liquid, Network pharmacology, Pharmacological mechanism, Respiratory tract infection, Flos Lonicerae, Radix Scutellariae, Fructus Forsythiae

1. Background

SHL oral liquid is a well-known traditional Chinese medicine preparation frequently applied to treat acute upper respiratory tract infection, acute bronchitis, and pneumonia [1]. SHL oral liquid is derived from three Chinese medicinal herbs, namely, Flos Lonicerae (Jinyinhua, JYH), Radix Scutellariae (Huangqin, HQ), and Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao, LQ), which were officially recorded in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2015 Edition) [2], the legal standard for drug use and development in China. SHL oral liquid (approval number Z41020565) was authorized by the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) and has been used clinically for over twenty years. SHL oral liquid displays a wide range of biological activities such as antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory [3]. Furthermore, it shows higher cure rates compared with conventional antivirus drugs [4,5]. As a famous Chinese patent medicine based on Traditional Chinese medicine theory, the pharmacological mechanism study of SHL oral liquid is still limited.

TCM, has been extensively used in clinical practice for thousands of years in Asia, and gradually gained popularity in western countries due to the reliable efficacy [6]. As an important part of complementary and alternative medical systems, TCM treats various diseases via potential multiple interactions of herbs [7]. Because of the multichemical components, multi-pharmacological effects, and multi-action targets of TCM in the treatment [8], the pharmacological mechanism of TCM is still difficult to entirely clarify through conventional research [9]. With the rapid progress of systems biology, bioinformatics, and poly-pharmacology [10], network pharmacology is considered to be a novel way to elucidate complex and holistic mechanisms of TCM [11]. Network pharmacology illustrates the complex interactions among the biological systems, drugs, and complex diseases from a network perspective, sharing a similar holistic philosophy as TCM [12]. The combination of TCM and network pharmacology is shifting the conventional "one target, one drug" paradigm to a multilevel network strategy [13]. In many previous studies, network pharmacology has been shown to be effective for exploring mechanisms [14], and has particularly contributed to investigations into the underlying mechanisms of TCM formula [15,16].

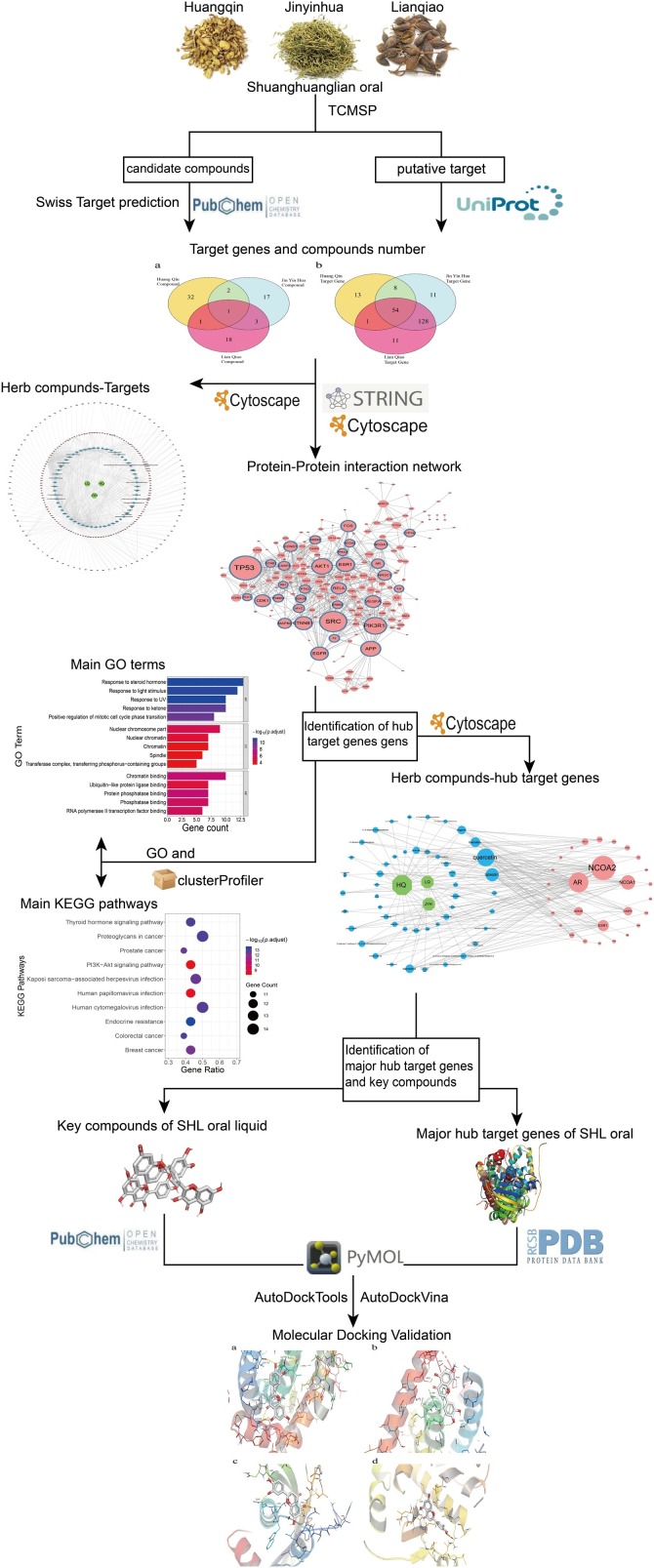

In the present study, the approach of network pharmacology was applied to analyze the relationship between drugs, targets, and metabolic pathways of SHL oral liquid (Fig. 1 ). By unveiling the molecular mechanisms, we expect to provide a relevant theoretical basis for clinical application and research of SHL oral liquid.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of the present study.

2. Methods

2.1. Acquisition of drug-related compounds and target genes

All ingredients in SHL oral liquid including JYH, HQ, and LQ were searched by herb names in Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology database (TCMSP, http://tcmspw.com/tcmsp.php). With the composition of a large number of herbal entries and relevant data, TCMSP is commonly used to identify drug-target networks and drug-disease networks, which contributes to revealing the mechanisms of action of Chinese herbs, uncovering the nature of TCM theory and developing new herb-oriented drugs [17]. All compounds with oral bioavailability (OB)≥ 30 % and drug-likeness (DL)≥ 0.18 were retrieved for subsequent research. As one of the most important pharmacokinetic parameters, OB represents the speed of a drug of becoming available to the human body, and the oral dose eventually absorbed, which plays a particularly significant role in drug discovery of TCM for majority of oral Chinese herb formulas. DL is a qualitative characteristic used in drug design to evaluate whether a compound is chemically suitable for drug. The target genes obtained above were verified by the UniProt [18] protein database (https://www.uniprot.org/) and converted into corresponding gene names.

To collect more reliable target genes of SHL oral liquid, all medicinal chemical components of SHL oral liquid in TCMSP were searched in the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) one by one to obtain their molecular information including: molecular formula, Chemical abstracts service number (CAS), and Canonical Simplified molecular-input line entry specification (SMILES). PubChem is the world's largest collection of freely accessible chemical information database. PubChem database is constantly adding new data including chemical and physical properties, biological activities, safety and toxicity information, patents, literature citations, and so on [19]. SMILES of the compounds were pasted in the box of Swiss Target Prediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/). This website allows researchers to estimate the most probable macromolecular target genes of a small molecule. The Swiss Target Prediction is founded on a combination of 2D and 3D similarity with a library of 370,000 known actives on more than 3000 proteins from three different species [20]. The Swiss Target Prediction applied a probability index to evaluate the robustness of the prediction results, ranging from 0 to 1. In the present study, we merely included the prediction target with probability equal to 1. Then, the data from TCMSP and Swiss Target Prediction were combined for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Herbs-compounds-target genes network construction

To have a further understanding of the molecular mechanisms, the herb compounds-targets network was constructed by Cytoscape (version 3.7.2), that is, the compounds and target genes retrieved from TCMSP and Swiss Target Prediction were inputted into Cytoscape for constructing the network. Cytoscape is an open-source software platform for visualizing complex biomolecular networks and integrating these with annotations, gene expression profiles, and other state data [21]. During the network construction, users can visually get lots of topology information by different colors, graphics, symbols of every node, making the relationships between each node more understandable and recognizable. Through this network, the pharmacological characteristics of SHL oral liquid which were characterized by multi-component and multi-target would be preliminarily demonstrated. Furthermore, the common compounds and target genes of SHL oral liquid would be analyzed and displayed by Venn diagram.

2.3. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction and identification of hub target genes

To construct a PPI network among target genes of SHL oral liquid, target genes of SHL oral liquid collected from TCMSP and Swiss Target Prediction were inputted into STRING 11.0 (https://string-db.org/, updated on January 19, 2019) for obtaining interactions among proteins expressed by target genes. STRING is one of the major existing regularly updated public PPI databases, which covers the majority of known human protein-protein interactions information [22]. The organism parameter of STRING was set as “has” (Human). In addition, the interaction confidence score was set as greater than or equal to 0.9 to ensure the high confidence and reliability of the outcomes and the disconnected nodes in the network were excluded. Next, the graphical interactions in this network were visualized and analyzed using Cytoscape (version 3.7.2). Besides, ‘Degree’, one of the most important parameters of the topology structure, was used for essentiality assessing each node in the PPI network. ‘Degree’ is regarded as the number of links to a node, which is usually used to describe the topological importance in the PPI network of a protein. Furthermore, only nodes whose ‘Degree’ more than twofold median of the degree of the network were defined as hub target genes according to previous reports [[23], [24], [25]]. Subsequently, the hub target genes were screened out by this way.

2.4. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway enrichment analysis

The GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were performed by clusterProfiler. clusterProfiler is a functional and regularly updated R package which is widely used for high-throughput data analysis such as bioinformatics analysis based on multiple bioconductor annotation resources and R packages. It could compare gene clusters of any kind of gene–ontology associations including GO and KEGG [26]. GO terms including molecular function (MF), biological process (BP), and cellular components (CC) were identified.

In addition, parameter settings of clusterProfiler were as follows: (1) the organism parameter was set as “has” (Human); (2) the analysis cutoff of P-value was set as 0.05. Furthermore, the false discovery rate (FDR) served as P-value adjustment.

2.5. Herbs-compounds-hub targets network construction

The herb compounds-hub target genes network was generated by Cytoscape (version 3.7.2). In this network, nodes with the more than twofold median of degree value would be defined as major hub target genes, while the compounds with the top five degree value would be regarded as the key compounds of SHL oral liquid that play the most important pharmacological role. By constructing this network, the potential relationship between the compounds and hub targets of SHL oral liquid would be explored to uncover the potential pharmacological mechanisms of SHL oral liquid.

2.6. Molecular docking between compounds and targets

Molecular docking was performed to further validate the relationship between the key compound and major hub target gene. The 3D structures of key compounds of SHL oral liquid were downloaded from the Pubchem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) as SDF format and were changed to PDB format by a software called PyMol (version 2.2). PyMol is an open-source molecular visualization system that can render high-quality 3D images of small molecules and biological macromolecules [27]. Meanwhile, proteins of major hub genes complex with crystallographic structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (https://www.rcsb.org/). PDB is one of the most important databases to collect the 2.5D structure of biomacromolecule, including protein, nucleic acid, and sugar. PyMol was also applied to removing the additional hydrone and ligand of the hub target gene protein. Next, AutoDockTools (version 4.2.6) [28] was used for addition of hydrogen atoms, combination of nonpolar hydrogen atoms, calculation of protein charge number, and detection of the docking site before molecular docking. Subsquently, the key compounds were set as ligand and had their structure torsions and roots detected by AutoDockTools as well. At last, all the major hub target proteins and key compounds were changed to pdbqt format, and then inputted into AutoDock Vina (version 1.1.2) [29] for performing molecular docking. The docking affinity score below -5.0 kcal/mol means a strong binding interaction between the compounds and their target genes [30].

3. Results

3.1. Identification of the active compounds and target genes in SHL oral liquid

A total of 82 compounds of the three herbs in SHL oral liquid were retrieved from TCMSP with the criteria of OB ≥ 30 % and DL ≥ 0.18, including 36 of Huangqin, 23 of Jinyinhua, and 23 of Lianqiao (Table 1 ). According to the target prediction system in TCMSP and Swiss Target Prediction, totally 471 target genes of SHL oral liquid were retrieved including 76 of Huangqin, 201 of Jinyinhua, and 194 of Lianqiao. After combing all the target genes and removed the duplicated genes, 226 unique target genes were identified in total. (Appendix File 1)

Table 1.

Information for 82 chemical compounds of SHL oral liquid.

| Mol ID | Molecule Name | OB (%) | DL | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOL001689 | acacetin | 34.97 | 0.24 | Huang Qin |

| MOL000173 | wogonin | 30.68 | 0.23 | |

| MOL000228 | (2R)-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-2-phenylchroman-4-one | 55.23 | 0.2 | |

| MOL002714 | baicalein | 33.52 | 0.21 | |

| MOL002908 | 5,8,2'-trihydroxy-7-methoxyflavone | 37.01 | 0.27 | |

| MOL002909 | 5,7,2,5-tetrahydroxy-8,6-dimethoxyflavone | 33.82 | 0.45 | |

| MOL002910 | carthamidin | 41.15 | 0.24 | |

| MOL002911 | 2,6,2',4'-tetrahydroxy-6'-methoxychaleone | 69.04 | 0.22 | |

| MOL002913 | dihydrobaicalin_qt | 40.04 | 0.21 | |

| MOL002914 | eriodyctiol | 41.35 | 0.24 | |

| MOL002915 | Salvigenin | 49.07 | 0.33 | |

| MOL002917 | 5,2',6'-trihydroxy-7,8-dimethoxyflavone | 45.05 | 0.33 | |

| MOL002925 | 5,7,2',6'-Tetrahydroxyflavone | 37.01 | 0.24 | |

| MOL002926 | dihydrooroxylin A | 38.72 | 0.23 | |

| MOL002927 | skullcapflavone II | 69.51 | 0.44 | |

| MOL002928 | oroxylin a | 41.37 | 0.23 | |

| MOL002932 | panicolin | 76.26 | 0.29 | |

| MOL002933 | 5,7,4'-trihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone | 36.56 | 0.27 | |

| MOL002934 | neobaicalein | 104.34 | 0.44 | |

| MOL002937 | dihydrooroxylin | 66.06 | 0.23 | |

| MOL000358 | beta-sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | |

| MOL000359 | sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | |

| MOL000525 | norwogonin | 39.4 | 0.21 | |

| MOL000552 | 5,2'-dihydroxy-6,7,8-trimethoxyflavone | 31.71 | 0.35 | |

| MOL000073 | ent-epicatechin | 48.96 | 0.24 | |

| MOL000449 | stigmasterol | 43.83 | 0.76 | |

| MOL001458 | coptisine | 30.67 | 0.86 | |

| MOL001490 | bis[(2S)-2-ethylhexyl] benzene-1,2-dicarboxylate | 43.59 | 0.35 | |

| MOL001506 | supraene | 33.55 | 0.42 | |

| MOL002879 | diop | 43.59 | 0.39 | |

| MOL002897 | epiberberine | 43.09 | 0.78 | |

| MOL008206 | moslosooflavone | 44.09 | 0.25 | |

| MOL010415 | 11,13-eicosadienoic acid, methyl ester | 39.28 | 0.23 | |

| MOL012245 | 5,7,4'-trihydroxy-6-methoxyflavanone | 36.63 | 0.27 | |

| MOL012246 | 5,7,4'-trihydroxy-8-methoxyflavanone | 74.24 | 0.26 | |

| MOL012266 | rivularin | 37.94 | 0.37 | |

| MOL001494 | mandenol | 42 | 0.19 | Jin Yin Hua |

| MOL001495 | ethyl linolenate | 46.1 | 0.2 | |

| MOL002707 | phytofluene | 43.18 | 0.5 | |

| MOL002914 | eriodyctiol (flavanone) | 41.35 | 0.24 | |

| MOL003006 | (-)-(3R,8S,9R,9aS,10aS)-9-ethenyl-8-(beta-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-2,3,9,9a,10,10a-hexahydro-5-oxo-5H,8H-pyrano[4,3-d]oxazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxylic acid_qt | 87.47 | 0.23 | |

| MOL003014 | secologanic dibutylacetal_qt | 53.65 | 0.29 | |

| MOL002773 | beta-carotene | 37.18 | 0.58 | |

| MOL003036 | zinc03978781 | 43.83 | 0.76 | |

| MOL003044 | chryseriol | 35.85 | 0.27 | |

| MOL003059 | kryptoxanthin | 47.25 | 0.57 | |

| MOL003062 | 4,5'-Retro-.beta,beta.-carotene-3,3'-dione, 4',5'-didehydro | 31.22 | 0.55 | |

| MOL003095 | 5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)chromone | 51.96 | 0.41 | |

| MOL003101 | 7-epi-Vogeloside | 46.13 | 0.58 | |

| MOL003108 | caeruloside C | 55.64 | 0.73 | |

| MOL003111 | centauroside_qt | 55.79 | 0.5 | |

| MOL003117 | Ioniceracetalides B_qt | 61.19 | 0.19 | |

| MOL003124 | xylostosidine | 43.17 | 0.64 | |

| MOL003128 | dinethylsecologanoside | 48.46 | 0.48 | |

| MOL000358 | beta-sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | |

| MOL000422 | kaempferol | 41.88 | 0.24 | |

| MOL000449 | Stigmasterol | 43.83 | 0.76 | |

| MOL000006 | luteolin | 36.16 | 0.25 | |

| MOL000098 | quercetin | 46.43 | 0.28 | |

| MOL000173 | wogonin | 30.68 | 0.23 | Lian Qiao |

| MOL003281 | 20(S)-dammar-24-ene-3β,20-diol-3-acetate | 40.23 | 0.82 | |

| MOL003283 | (2R,3R,4S)-4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-7-methoxy-2,3-dimethylol-tetralin-6-ol | 66.51 | 0.39 | |

| MOL003290 | (3R,4R)-3,4-bis[(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methyl]oxolan-2-one | 52.3 | 0.48 | |

| MOL003295 | (+)-pinoresinol monomethyl ether | 53.08 | 0.57 | |

| MOL003305 | phillyrin | 36.4 | 0.86 | |

| MOL003306 | acon1_001697 | 85.12 | 0.57 | |

| MOL003308 | (+)-pinoresinol monomethyl ether-4-D-beta-glucoside_qt | 61.2 | 0.57 | |

| MOL003315 | 3beta-Acetyl-20,25-epoxydammarane-24alpha-ol | 33.07 | 0.79 | |

| MOL000211 | mairin | 55.38 | 0.78 | |

| MOL003322 | forsythinol | 81.25 | 0.57 | |

| MOL003330 | (-)-Phillygenin | 95.04 | 0.57 | |

| MOL003344 | β-amyrin acetate | 42.06 | 0.74 | |

| MOL003347 | hyperforin | 44.03 | 0.6 | |

| MOL003348 | adhyperforin | 44.03 | 0.61 | |

| MOL003365 | lactucasterol | 40.99 | 0.85 | |

| MOL003370 | onjixanthone I | 79.16 | 0.3 | |

| MOL000358 | beta-sitosterol | 36.91 | 0.75 | |

| MOL000422 | kaempferol | 41.88 | 0.24 | |

| MOL000522 | arctiin | 34.45 | 0.84 | |

| MOL000006 | luteolin | 36.16 | 0.25 | |

| MOL000791 | bicuculline | 69.67 | 0.88 | |

| MOL000098 | quercetin | 46.43 | 0.28 |

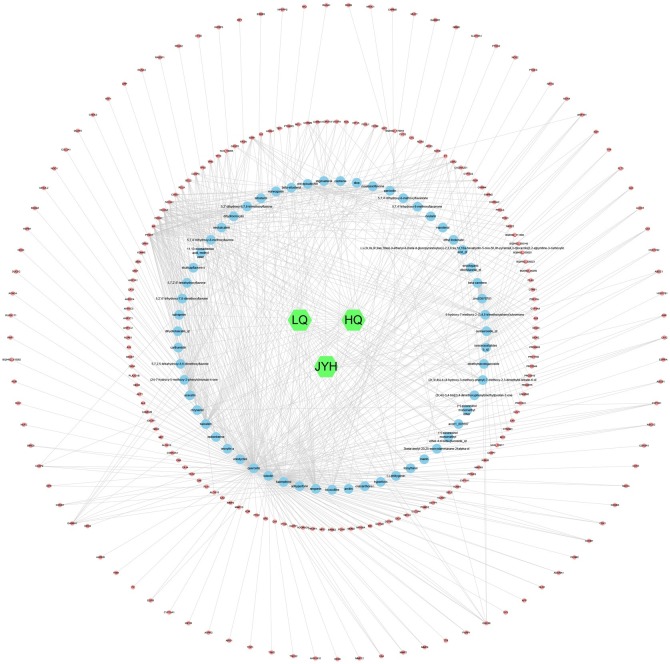

3.2. Herbs-compounds-target genes network analysis

Herbs-compounds-target genes network was constructed via Cytoscape 3.7.2 to show the relationship between the herbs, compounds, and target genes (Fig. 2 ). In this network, there were 288 nodes and 654 edges in total, showing that SHL oral liquid might exert its therapeutic effect by multiple compounds and various target genes.

Fig. 2.

Herbs-compounds-target genes network of SHL oral liquid.

Note: The green node represents herbs in SHL oral liquid; the blue represents the active compound of SHL oral liquid and the red node represents the target gene.

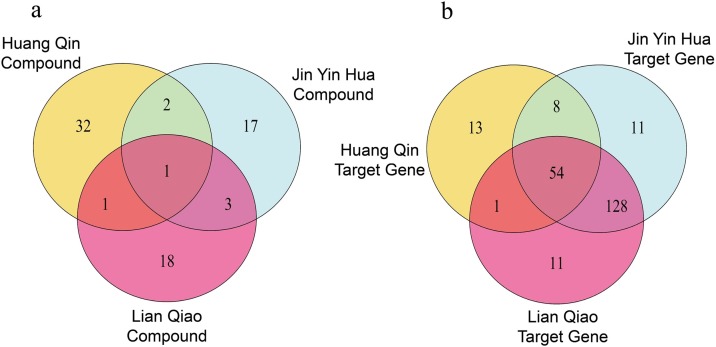

In the Venn diagram of compounds (Fig. 3 a), Huangqin and Jinyinhua shared 3 compounds in common; Lianqiao and Huangqin shared 2; Jinyinhua and Lianqiao shared 4. In the Venn diagram of target genes (Fig. 3b), Huangqin and Jinyinhua shared 62 target genes in common; Lianqiao and Huangqin shared 55; Jinyinhua and Lianqiao shared 182. These findings showed that the herbs of SHL oral liquid might produce the efficacy by the synergic action of the common compounds and target genes shared by each other.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram of compound and target gene relationship in SHL oral liquid.

a: Venn diagram of compound relationship in SHL oral liquid.

b: Venn diagram of target gene relationship in SHL oral liquid.

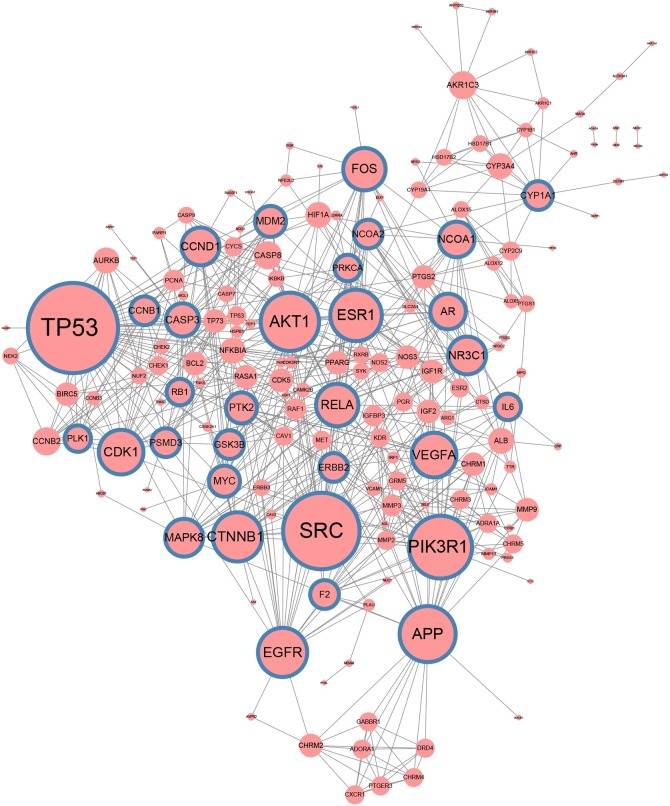

3.3. Exploration of the target genes in the PPI network

PPI network was constructed after 226 unique target genes being put into STRING software (Fig. 4 ). The results of the network topology analysis were as follows: mean betweenness: 013; mean degree: 7.317; mean closeness: 0.349; median degree: 6. In this network, there were 167 nodes and 611 edges in total. 59 target genes were excluded from the network construction due to not meeting the screening criteria. Finally, 28 hub target genes were screened based on the topological properties of the degree of network nodes (degree >12). The information of these hub target genes was shown in Table 2 .

Fig. 4.

The PPI network of target genes in SHL oral liquid.

Note: The nodes with blue border represent hub target genes. The node size is positively related to the degree of the node.

Table 2.

Information of hub target genes of SHL oral liquid.

| Hub Gene | Protein names | Degree | UniPort Entry |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A1 | Cytochrome P450 | 13 | Q0VHD5 |

| CCNB1 | G2/mitotic-specific cyclin-B1 | 13 | H0Y9U8 |

| NCOA2 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 2 | 13 | A0A1D5RMT0 |

| ERBB2 | Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2 | 13 | J3KTI5 |

| PSMD3 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 3 | 13 | F5H8K4 |

| GSK3B | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta | 13 | A0A3B3ITW1 |

| F2 | F2 Protein | 13 | E9PIT3 |

| MDM2 | MDM2 protein | 14 | A0A0A8KA17 |

| PTK2 | Focal adhesion kinase 1 | 14 | E7ESA6 |

| MYC | V-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog | 14 | B3CJ87 |

| CASP3 | Caspase-3 | 15 | A8MVM1 |

| AR | Androgen receptor splice variant 5 | 16 | C0JKD6 |

| NCOA1 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 1 | 16 | B5MCN7 |

| CCND1 | G1/S-specific cyclin-D1 | 17 | F5H437 |

| NR3C1 | Glucocorticoid nuclear receptor variant 1 | 17 | F1D8N4 |

| MAPK8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | 17 | A0A3B3IRW7 |

| RELA | Transcription factor p65 | 19 | A0A087WVP0 |

| FOS | Proto-oncogene c-Fos | 19 | H0YJM3 |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A | 20 | H0YBI8 |

| CDK1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 | 20 | A0A087WZZ9 |

| CTNNB1 | Catenin beta-1 | 22 | A0A2R8Y804 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | 22 | A7VN06 |

| ESR1 | Estrogen receptor protein | 23 | K7R989 |

| APP | Amyloid beta A4 protein | 25 | L7XE61 |

| AKT1 | RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase | 26 | A0A087WY56 |

| PIK3R1 | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulatory subunit alpha | 28 | E5RK66 |

| SRC | Tyrosine kinase pp60c-src | 34 | Q71UK5 |

| TP53 | Cellular tumor antigen p53 | 40 | J3KP33 |

3.4. Analysis of GO and KEGG pathway analysis result

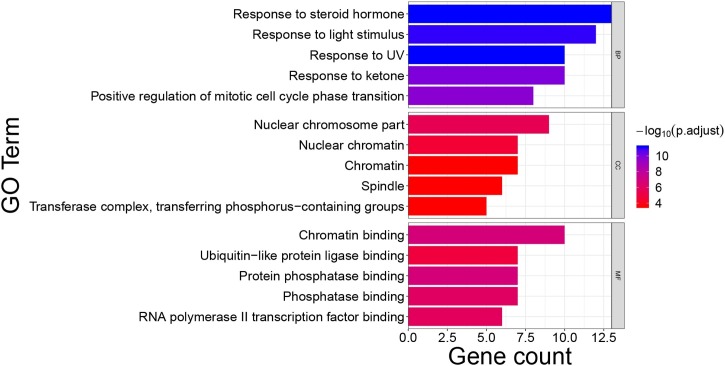

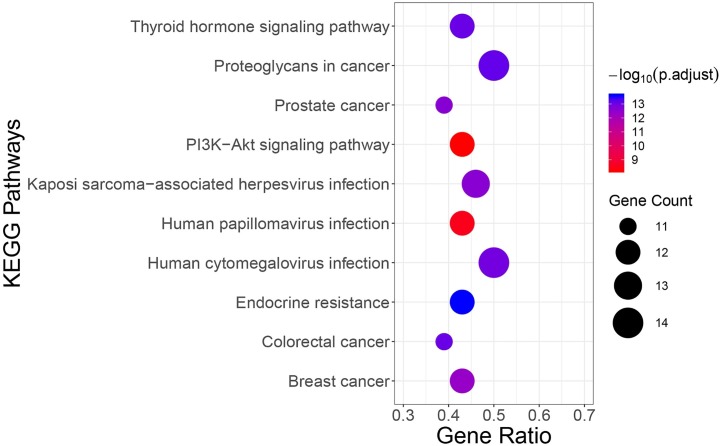

GO annotation and KEGG pathway enrichment of SHL oral liquid target genes were carried out through clusterProfier. GO annotation was performed in three aspects including biological process (BP), cell composition (CC), and molecular function (MF). The enrichment results included 1390 BP terms, 30 CC terms, 109 MF terms. The first five terms with a significant adjusted P-value were shown in Fig. 5 . Main BP included the response to steroid hormone and response to light stimulus; Main CC involved nuclear chromosome part, nuclear chromatin, and other cell components; Main MF covered chromatin binding, ubiquitin-like protein ligase binding, etc. 168 relevant pathways of SHL oral liquid were obtained by KEGG pathway enrichment. The main KEGG pathways included the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, human papillomavirus infection, and human cytomegalovirus infection (Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 5.

Main Gene Ontology terms enriched by hub target genes.

Note: The color of terms turned from blue to red. The redder the bar was, the smaller the adjusted P value was.

Abbreviations: BP: biological processes; CC: Cellular Component; MF, molecular function.

Fig. 6.

Main KEGG pathway enriched by hub target genes.

Note: The color of terms turned from blue to red. The redder the bubble was, the smaller the adjusted p value was.

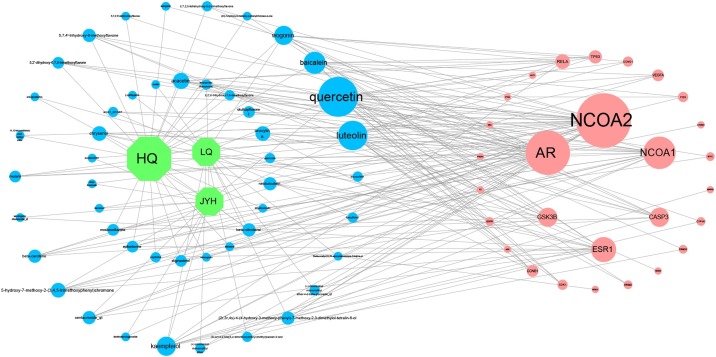

3.5. Herbs-compounds-hub target genes network analysis

Herbs-compounds-hub target genes network was constructed to investigate the relationship between herbs and compounds of SHL oral liquid and the major hub target genes (Fig. 7 ). The analysis results of the network topology were as follows: mean betweenness (0.021); mean degree (5.367) and mean closeness (0.388). In addition, the information of important nodes in the network was shown in Table 3 . In this network, there were 79 nodes and 212 edges in total. The nodes of hub target genes with more than twofold median of degree (degree > 6) including NCOA2, AR, NCOA1, and ESR1, and these hub target genes were regarded as the major hub target genes. In addition, 5 key compounds were screened out as key compounds of SHL oral liquid including quercetin, luteolin, wogonin, baicalein, and kaempferol (Table 4 ).

Fig. 7.

Herbs-compounds-hub target genes network of SHL oral liquid.

Note: The green node represents herbs in SHL oral liquid; the blue represents the compound of SHL oral liquid and the red node represents the hub target gene. The node size is positively related to the degree of the node.

Table 3.

Important node of herbs-compounds-hub target genes network.

| Node Name | Node Type | Degree |

|---|---|---|

| NCOA2 | Target Gene | 33 |

| AR | Target Gene | 26 |

| quercetin | Compound | 23 |

| NCOA1 | Target Gene | 18 |

| luteolin | Compound | 16 |

| ESR1 | Target Gene | 13 |

| baicalein | Compound | 11 |

| kaempferol | Compound | 9 |

| wogonin | Compound | 9 |

| CASP3 | Target Gene | 9 |

| GSK3B | Target Gene | 9 |

| acacetin | Compound | 7 |

| 5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)chromone | Compound | 6 |

| chryseriol | Compound | 6 |

| oroxylin a | Compound | 6 |

| RELA | Target Gene | 6 |

| (2 r,3 r,4 s)-4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-7-methoxy-2,3-dimethylol-tetralin-6-ol | Compound | 5 |

| centauroside_qt | Compound | 5 |

| beta-carotene | Compound | 5 |

| beta-sitosterol | Compound | 5 |

| neobaicalein | Compound | 5 |

| 5,7,4'-trihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone | Compound | 5 |

| TP53 | Target Gene | 5 |

| rivularin | Compound | 4 |

| moslosooflavone | Compound | 4 |

| epiberberine | Compound | 4 |

| stigmasterol | Compound | 4 |

| 5,2'-dihydroxy-6,7,8-trimethoxyflavone | Compound | 4 |

| skullcapflavone ii | Compound | 4 |

| VEGFA | Target Gene | 4 |

| CCNB1 | Target Gene | 4 |

| bicuculline | Compound | 3 |

| forsythinol | Compound | 3 |

| (+)-pinoresinol monomethyl ether-4-d-beta-glucoside_qt | Compound | 3 |

| acon1_001697 | Compound | 3 |

| (+)-pinoresinol monomethyl ether | Compound | 3 |

| (3 r,4r)-3,4-bis[(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)methyl]oxolan-2-one | Compound | 3 |

| coptisine | Compound | 3 |

| panicolin | Compound | 3 |

| 5,2',6'-trihydroxy-7,8-dimethoxyflavone | Compound | 3 |

| eriodyctiol (flavanone) | Compound | 3 |

| 5,7,2,5-tetrahydroxy-8,6-dimethoxyflavone | Compound | 3 |

| FOS | Target Gene | 3 |

| CCND1 | Target Gene | 3 |

| CDK1 | Target Gene | 3 |

| arctiin | Compound | 2 |

| (-)-phillygenin | Compound | 2 |

| 3beta-acetyl-20,25-epoxydammarane-24alpha-ol | Compound | 2 |

| dinethylsecologanoside | Compound | 2 |

| zinc03978781 | Compound | 2 |

| secologanic dibutylacetal_qt | Compound | 2 |

| ethyl linolenate | Compound | 2 |

| mandenol | Compound | 2 |

| 11,13-eicosadienoic acid, methyl ester | Compound | 2 |

| ent-epicatechin | Compound | 2 |

| norwogonin | Compound | 2 |

| sitosterol | Compound | 2 |

| dihydrooroxylin | Compound | 2 |

| 5,7,2',6'-tetrahydroxyflavone | Compound | 2 |

| salvigenin | Compound | 2 |

| (2 r)-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-2-phenylchroman-4-one | Compound | 2 |

| ERBB2 | Target Gene | 2 |

| PSMD3 | Target Gene | 2 |

| CYP1A1 | Target Gene | 2 |

| MYC | Target Gene | 2 |

| EGFR | Target Gene | 2 |

| NR3C1 | Target Gene | 1 |

| MDM2 | Target Gene | 1 |

| MAPK8 | Target Gene | 1 |

| CTNNB1 | Target Gene | 1 |

| AKT1 | Target Gene | 1 |

| PTK2 | Target Gene | 1 |

| SRC | Target Gene | 1 |

| PIK3R1 | Target Gene | 1 |

| F2 | Target Gene | 1 |

| APP | Target Gene | 1 |

Table 4.

Key compounds of Shuanghuanglian oral liquid.

| Drug | Molecule Name | Molecular Structural Formula | OB(%) | DL | CAS Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LQ JYH | Quercetin |  |

46.43 | 0.28 | 117-39-5 |

| C15H10O7 | |||||

| JYH | Luteolin |  |

36.16 | 0.25 | 491-70-3 |

| C15H10O6 | |||||

| LQ HQ | Wogonin |  |

30.68 | 0.23 | 632-85-9 |

| C16H12O5 | |||||

| HQ | Baicalein |  |

33.52 | 0.21 | 491-67-8 |

| C15H10O5 | |||||

| LQ JYH | Kaempferol |  |

41.88 | 0.24 | 520-18-3 |

| C15H10O6 |

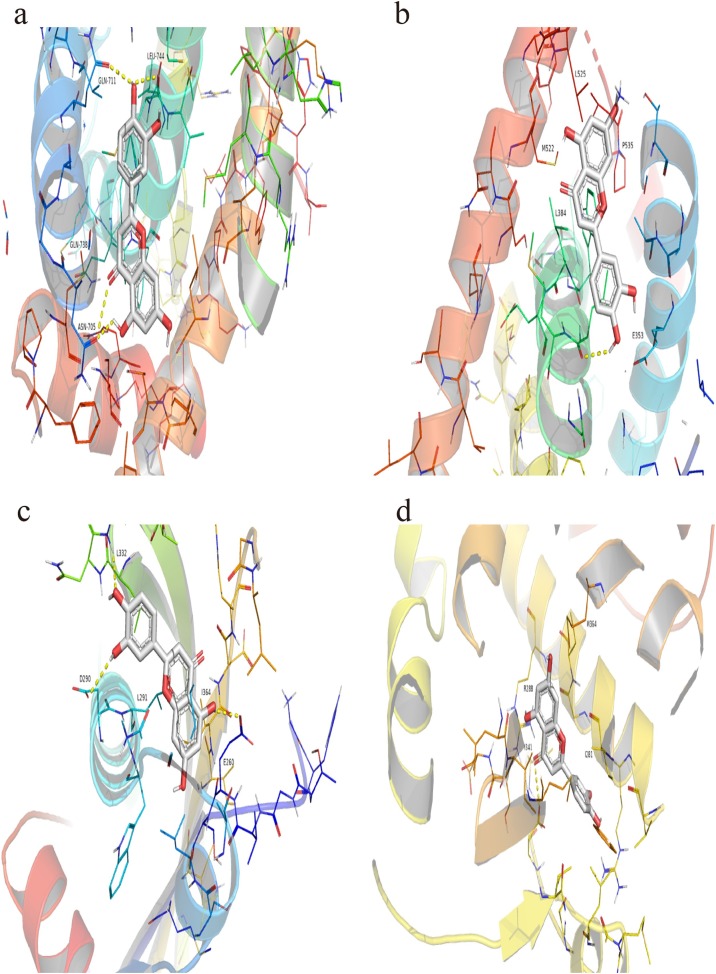

3.6. Molecular docking result analysis

With the key compounds and major hub target genes identified, the molecular docking between the key compounds and proteins expressed by major hub target genes was performed. The docking affinity score was calculated by Autodock Vina, as shown in Table 5 . Moreover, the docking conformations of luteolin and hub target proteins were shown in Fig. 8 . Additional docking conformations of compounds and hub target genes were provided in supplementary materials including Fig S1, Fig S2, Fig S3, and Fig S4. As shown in Table 5, baicalein, kaempferol, luteolin, quercetin, and wogonin all had well binding interaction with the hub target protein expressed by major hub target genes. The average docking scores AR, ESR1, NCOA1, and NCOA2 and the key compounds were -8.88, -8.36, -7.54 and -8.74 kcal/mol, respectively, which means great binding interactions between compounds and hub target genes.

Table 5.

Molecular docking result between key compounds and hub target proteins.

| Hub target proteins | Docking Affinity with hub target proteins(kcal/mol) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key compounds | AR | ESR1 | NCOA1 | NCOA2 |

| Baicalein | −8.9 | −8.8 | −7.5 | −9 |

| Kaempferol | −8.8 | −8.4 | −7.7 | −8.5 |

| Luteolin | −9.2 | −9 | −7.6 | −8.9 |

| Quercetin | −8.8 | −9.1 | −7.4 | −8.5 |

| Wogonin | −8.7 | −6.5 | −7.5 | −8.8 |

Fig. 8.

The docking conformation between luteolin and major hub genes.

a: luteolin-AR; b: luteolin-ESR1; c: luteolin-NCOA1; d: luteolin-NCOA2.

4. Discussion

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), which has been assiduously developed for more than two millennia, plays a significant role in clinical practice. SHL oral liquid, is a commonly used Chinese patent medicine, and has been reported to have a good therapeutic effect regarding the clearing of heat and detoxifying [31]. In TCM, heat evil is an important pathogen in infectious diseases. Treatment focuses on the use of compounds with heat-clearing properties, SHL oral liquid has this heat-clearing property and in clinical practice, SHL oral liquid is commonly used for the treatment of infectious diseases such as pneumonia and pharyngitis, etc. [32,33]. In terms of composition, SHL oral liquid is derived from three Chinese medicinal herbs, including Flos Lonicerae (Jinyinhua, JYH), Radix Scutellariae (Huangqin, HQ), and Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao, LQ), whose therapeutic effect associated with anti-inflammatory and antiviral [[34], [35], [36], [37]]. Moreover, it was recommended for the treatment of influenza in Influenza Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines (2011 edition) based on its favorable curative effect [38]. Though SHL oral liquid was reported to have pharmacologic action of anti-virus and anti-inflammatory, the exact mechanism remains unknown. As such, network pharmacology is in a position to analyze the underlying pharmacological mechanisms of SHL oral liquid. In the present study, network pharmacological analysis of SHL oral liquid identified 5 compounds, 28 hub target genes, and 3 main signaling pathways accounting for the therapeutic effect of SHL oral liquid.

According to the herbs-compounds-hub target genes network, five compounds with high degree values including quercetin, luteolin, baicalein, kaempferol, and wogonin were identified as key compounds of SHL oral liquid. Notably, quercetin, luteolin, baicalein, and kaempferol are all attributed to flavonoids whose biological activities involve anti-inflammatory and anti-virus [39].

Quercetin was reported to have virucidal activity against enveloped viruses including herpes simplex, parainfluenza type, and respiratory syncytium [40]. Quercetin is reported to modulate the transport activities of the multidrug-resistance-associated proteins. Moreover, quercetin could not only influence the bioavailability of anticancer and antiviral drugs in vivo but also alleviate endotoxin-stimulated apoptosis and inflammation by up-regulation of relevant micro-RNA [41,42]. Additionally, quercetin could mitigate the intracellular formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to reduce the pro-inflammatory response [43]. Luteolin is proved to have significant protective effects of anti-virus and anti-inflammatory in vivo. As a kind of neuraminidase inhibitors, luteolin could effectively inhibit the replication of the influenza virus and spread in the virus particle surface [44]. Also, luteolin possesses the ability to hinder acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) to enter the host cells by binding avidly to the SARS-CoV inhibited protein [45]. By regulating the inflammatory cytokines and anti-oxidant factors, luteolin is associated with higher clearance of virus and inflammatory lung injury [46].

Baicalein has been found to inhibit the virus in vivo. Baicalein significantly reduces the levels of early and late proteins and DNA synthesis of human cytomegalovirus (HCV) [47]. In a mouse model, baicalein has been found to reduce the titre of influenza A virus leading to inhibition of lung consolidation, and the increase of mean survival time [48]. It’s reported that kaempferol could decrease nitric oxide (NO) production to regulate the blood flow and maintain the coordination between vascular endothelial cells, as well as inflammatory cells by suppressing the NO synthetase mRNA expression [49]. Additionally, kaempferol regulates the transcription factor and protein kinase to suppress on virus-induced inflammation [50]. One previous study suggests that kaempferol may be regarded as an effective drug for the potential treatment of influenza virus-induced acute lung injury [51]. Wogonin was attested to suppress the replication of multiple viruses, such as varicella-zoster virus and influenza virus. Wogonin not only inhibits replication of influenza A virus strains but also attenuates the plaque formation of influenza B strains, thus suggesting its broad anti-viral effect on diverse influenza strains [51]. In addition, wogonin effectively reduces virus titer by down-regulating the expressions of viral oncogenes and promoting intrinsic apoptosis in cervical cancer cells [52]. Besides, wogonin can inhibit shingles virus replication through modulation of interferon signal and adenosine monophophate-activated protein kinase activity [53]. Furthermore, wogonin was verified to down-regulate the expression of inflammation-associated enzymes, such as cyclooxygenases (COX) and lipoxygenases [54].

Taken together, previous studies showed that these key compounds of SHL oral liquid were effective for anti-virus or anti-inflammatory, which might be the scientific interpretations for therapeutic effect of SHL oral liquid for anti-virus and anti-inflammatory activities. In the PPI network, four hub genes including ESR1, NCOA2, NCOA1, and AR with a greater degree (degree>10) were identified as major hub genes at which SHL oral liquid target to exert therapeutic effect. ESR1 is a transcription activator with growth-suppressive functions [55]. A study shows that the expression of ESR1 could inhibit influenza A virus replication and lower viral titer in primary human nasal epithelial cells by binding to estrogens to regulate the cellular function of respiratory tract cells [56]. Both NCOA1 and NCOA2 are nuclear receptor coactivators that directly bind nuclear receptors and stimulate the transcriptional activities in a hormone-dependent fashion [57,58]. NCOA1 is capable of enhancing the level of retinoic acid receptors, the key regulators of interleukin-17, which play an important role in autoimmunity, chronic inflammation and host protection against extracellular bacteria and fungi [59]. NCOA2 is a transcriptional coactivator for steroid receptors and nuclear receptors. Wei et.al found that NCOA2 promotes the reactivation of herpesvirus by enhancing the expression of the transcription activator [60]. AR, as a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, regulates a wide range of target gene expression [61]. AR has been shown to modulate immune systems by indirect hormonal modulation of B-cell maturation in stromal cells [62]. By regulating cellar proliferation or survival, AR negatively regulates the number of alveolar macrophages (AM) to reduce the recruitment of inflammatory factors in the lung [63]. Given the AR receptor knocked out, the human body would be more susceptible to microbial, thus the risk of hospitalization for pneumonia would increase [64]. In addition, these major hub genes all had great binding capacity to the key compounds by molecular docking verification. We hypothesized that the efficacy of SHL oral liquid, improving human immunity, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects, stems from these main hub genes.

GO analysis found that hub target genes were mainly associated with the biological processes of response to steroid hormones, response to ketone, and positive regulation of mitotic cell cycle phase transition. As revealed from the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, SHL oral liquid might produce therapeutic effects primarily by regulating PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, thyroid hormone signaling pathway, human cytomegalovirus infection, and human papillomavirus infection. PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is known to associate with viral replication and inflammatory response [65,66]. Cellular PI3K/Akt signaling pathway may inhibit the lytic infections of both RNA and DNA viruses, thus some inhibitors of PI3K or its downstream signal Akt could significantly block virus entry and replication [66]. The activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway was responsible for the increased levels of adenosine diphosphate and promoted platelet activation, leading to anabatic vascular permeability and pulmonary inflammatory responses [67,68]. Moreover, with the PI3K/Akt pathway inhibited, the activation of negative regulators in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) would be blocked, resulting the inhibition of RSV [68].

In the present study, the hub targets of SHL oral liquid also enriched in the pathways related to cancer, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and thyroid hormone signaling pathway. Thyroid hormone signaling pathway was reported to involve several mechanisms to activate either the tumor cells or cells of the micro-environment, but the mechanisms were unclear [69,70]. These findings showed that the ingredients of SHL oral liquid might have potency for anti-tumor activity.

Besides, the pathway term of human papillomavirus infection and human cytomegalovirus infection might be clues for explaining the mechanisms of SHL oral liquid for treating diseases related to virus infection. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), ubiquitous herpes virus, activates the immune system, which produces a specific reaction to combat the virus. HCMV is capable of evading immune detection and various hematopoietic cell monocytes [71]. Besides, HCMV could express homologues of host protein-coupled receptors to promote viral replication and maintain viral persistence. As such, at the initial period of infection, targeting viral proteins may be limited to exacerbation of HCMV infection [72]. Following HCMV infection, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP) is over-expressing to accelerate inflammation and tissue injury in vascular tissues [73]. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is characterized by the specific host cells of DNA viruses which are epitheliotropic and mucosotropic [74]. HPV is also believed to stimulate the immune system, induce inflammation, and the body's anti-viral processes. With the pulmonary epithelial cell infected, HPV leads to the abnormal expression of cell cycle regulators in undifferentiated cells creating a replication-competent environment for virus. Hence, the HPV viral genome amplifies and packages into infectious particles [75,76]. Besides, HPV could also upregulate the expression of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and prostaglandin (PG) followed by the activation of the COX-PG pathway to cause inflammation [77]. In addition, HPV was also reported to increase the level of epidermal growth factor receptor and activate PI3K-AKT pathway, leading to inflammation [78].

Consequently, SHL oral liquid might act on these signaling pathways to improve immune function and reduce the inflammatory responses, which could explain the apparent effects of SHL oral liquid. These KEGG pathways, associated with related components and hub genes, might interact to exert their combined effects. In summary, the findings of the present work provided a holistic view of the potential pharmacological mechanisms for SHL oral liquid, which may contribute to its further research and clinical application. However, there are some limitations in the present work. Firstly, the anti-virus and anti-inflammatory effect of key compounds and major hub target genes identified were mainly found in recent cell or animal experiments. Secondly, though the hub target proteins expressed by the hub target genes have good affinity with the key compounds of SHL oral liquid, the interaction between them still needs experimental validation. In summary, the present study provided a new view of pharmacological mechanisms for SHL oral liquid, but further experimental or clinical verification of the findings of the present study is still needed.

5. Conclusion

As an important part of alternative and complementary medicine, TCM has made greater contributions to the treatment of diseases. Using a network pharmacology-based strategy, SHL oral liquid was found to have anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects based on its key compounds, hub target genes, and other relevant pathways. To enhance the reliability of the findings, further experimental and clinical research is needed.

Authors’ contributions

Data cleaning and analysis: Zhenjie Zhuang, Junmao Wen, Chuanjin Luo

Figures drawing and table design: Zhenjie Zhuang, Huiqi Chen

Writing - review & editing: Lu Zhang, Mingjia Zhang, Xiaoying Zhong, Chuanjin Luo

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research was funded by Key scientific research projects of colleges and universities in Guangdong province, China: grant 2018KQNCX043 and Innovative strong school project for young talent, Guangdong Province Office of Education, China: grant BKQNCX038.

This funding bodies paid the processing cost for this article but it played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and data interpretation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dr. Fanrong Yu from The Central Hospital of Fengxian District, Shanghai, China, for her advice advice on writing the paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2020.101139.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhang T.-B., Yue R.-Q., Xu J., Ho H.-M., Ma D.-L., Leung C.-H., Chau S.-L., Zhao Z.-Z., Chen H.-B., Han Q.-B. Comprehensive quantitative analysis of Shuang-Huang-Lian oral liquid using UHPLC–Q-TOF-MS and HPLC-ELSD. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015;102:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.N.P. Committee . Chemical Industry Press; Beijing, China: 2015. Pharmacopoeia of People’s Republic of China. Part 1., Pharmacopoeia of People’s Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang J., Sun H.-M., Wang T.-L. Simultaneous determination of multiple classes of hydrophilic and lipophilic components in shuang-huang-Lian oral liquid formulations by UPLC-Triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometry. Molecules. 2017;22(12):2057. doi: 10.3390/molecules22122057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen W., Liu B., Wang L.-q., Ren J., Liu J.-p. Chinese patent medicines for the treatment of the common cold: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014;14(1):273. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zu M., Zhou D., Gao L., Liu A., Du G. Evaluation of Chinese traditional patent medicines against influenza virus in vitro. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2010;45(3):408–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung F. TCM: made in China. Nature. 2011;480(7378):S82–S83. doi: 10.1038/480S82a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Y., Zhang X., Wang Z., Zheng C., Li P., Huang C., Tao W., Xiao W., Wang Y., Huang L. Deciphering the combination principles of Traditional Chinese Medicine from a systems pharmacology perspective based on Ma-huang Decoction. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;150(2):619–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu G., Wang W., Wang X., Xu M., Zhang L., Ding L., Guo R., Shi Y. Network pharmacology-based strategy to investigate pharmacological mechanisms of Zuojinwan for treatment of gastritis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar A., Sharma D., Aggarwal M., Chacko K., Bhatt T.K. Cancer/testis antigens as molecular drug targets using network pharmacology. Tumor Biol. 2016;37(12):15697–15705. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang R., Zhu X., Bai H., Ning K. Network pharmacology databases for traditional Chinese medicine: review and assessment. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:123. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopkins A.L. Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4(11):682. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang M.-W., Yang H.-J., Zhou X.-C., Ge F.-X., Jiao S.-G., Tu P.-F., Xie Y.-Y., Chai X.-Y. Advances on network pharmacology in ethnomedicine research. China J. Chinese Matera Med. 2019;44(15):3187–3194. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20190711.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li S. Exploring traditional chinese medicine by a novel therapeutic concept of network target. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2016;22(9):647–652. doi: 10.1007/s11655-016-2499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao F., Guochun L., Yang Y., Shi L., Xu L., Yin L. A network pharmacology approach to determine active ingredients and rationality of herb combinations of Modified-Simiaowan for treatment of gout. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;168:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan Y., Xu L., Liu Z., Yang M., Jiang X., Zhang Q., Huang J. Utilising network pharmacology to explore the underlying mechanism of Wumei Pill in treating pancreatic neoplasms. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019;19(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2580-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu G., Zhang Y., Ren W., Dong L., Li J., Geng Y., Zhang Y., Li D., Xu H., Yang H. Network pharmacology-based identification of key pharmacological pathways of Yin-Huang-Qing-Fei capsule acting on chronic bronchitis. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2016;12:85. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S121079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ru J., Li P., Wang J., Zhou W., Li B., Huang C., Li P., Guo Z., Tao W., Yang Y. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J. Cheminform. 2014;6(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consortium U. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(5):2699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hao M., Cheng T., Wang Y., Bryant H.S. Web search and data mining of natural products and their bioactivities in PubChem. Sci. China Chem. 2013;56(10):1424–1435. doi: 10.1007/s11426-013-4910-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W357–W364. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Doncheva N.T., Morris J.H., Bork P., Jensen L.J., Mering C.V. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47(D1):1362–4962. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. (Electronic)) D607-D613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo Q., Zhong M., Xu H., Mao X., Zhang Y., Lin N. A systems biology perspective on the molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of Buyang Huanwu decoction on ischemic stroke. Rejuvenation Res. 2015;18(4):313–325. doi: 10.1089/rej.2014.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y., Wang D., Tan S., Xu H., Liu C., Lin N. A systems biology-based investigation into the pharmacological mechanisms of wu tou tang acting on rheumatoid arthritis by integrating network analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/548498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y., Xiaodong G., Danhua W., Ruisheng L., Xiaojuan L., Ying X., Zhenli L., Zhiqian S., Ya L., Zhiyan L. A systems biology-based investigation into the therapeutic effects of Gansui Banxia Tang on reversing the imbalanced network of hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4154. doi: 10.1038/srep04154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu G., Wang L.-G., Han Y., YHe Q.-Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics A J. Integr. Biol. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrodinger L. Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2017. The PyMol Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li X., Xu X., Wang J., Yu H., Wang X., Yang H., Xu H., Tang S., Li Y., Yang L. A system-level investigation into the mechanisms of Chinese Traditional Medicine: compound Danshen Formula for cardiovascular disease treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou X.-J., Chen J., Li Y.-D., Jin L., Shi Y.-P. Holistic analysis of seven active ingredients by micellar electrokinetic chromatography from three medicinal herbs composing Shuanghuanglian. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015;53(10):1786–1793. doi: 10.1093/chromsci/bmv067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L., Jiang W., Zhang L., Li F., Zhang Q. Chemical correlation between Shuanghuanglian injection and its three raw herbs by LC fingerprint. J. Sep. Sci. 2011;34(15):1834–1844. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201000851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ni L.-J., Zhang L.-G., Hou J., Shi W.-Z., Guo M.-L. A strategy for evaluating antipyretic efficacy of Chinese herbal medicines based on UV spectra fingerprints. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Z., Li X., Liu J., Dong L., Chen Q., Liu J., Kong H., Zhang Q., Qi X., Hou D. Honeysuckle-encoded atypical microRNA2911 directly targets influenza A viruses. Cell Res. 2015;25(1):39–49. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gołba M., Sokół-Łętowska A., Kucharska A.Z. Health properties and composition of honeysuckle berry Lonicera caerulea l. An update on recent studies. Molecules. 2020;25(3):749. doi: 10.3390/molecules25030749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao T., Tang H., Xie L., Zheng Y., Ma Z., Sun Q., Li X. Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi.(Lamiaceae): a review of its traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019;71(9):1353–1369. doi: 10.1111/jphp.13129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Z., Xia Q., Liu X., Liu W., Huang W., Mei X., Luo J., Shan M., Lin R., Zou D. Phytochemistry, pharmacology, quality control and future research of Forsythia suspensa (Thunb.) Vahl: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;210:318–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong N.-s., Li Y.-m., Yang Z.-f., Wang C., Liu Y.-n., Li X.-w., Shu Y.-l., Wang G.-f., Gao Z.-c., Deng G.-h. Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of influenza (2011) J. Thorac. Dis. 2011;3(4):274. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2011.10.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang R., Ai X., Duan Y., Xue M., He W., Wang C., Xu T., Xu M., Liu B., Li C. Kaempferol ameliorates H9N2 swine influenza virus-induced acute lung injury by inactivation of TLR4/MyD88-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;89:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiow K., Phoon M., Putti T., Tan B.K., Chow V.T. Evaluation of antiviral activities of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. extract, quercetin, quercetrin and cinanserin on murine coronavirus and dengue virus infection. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo S., Sun J., Zhuang Y. Quercetin alleviates lipopolysaccharide‐induced inflammatory responses by up‐regulation miR‐124 in human renal tubular epithelial cell line HK‐2. BioFactors. 2019:1–9. doi: 10.1002/biof.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu C.P., Calcagno A.M., Hladky S.B., Ambudkar S.V., Barrand M.A. Modulatory effects of plant phenols on human multidrug‐resistance proteins 1, 4 and 5 (ABCC1, 4 and 5) FEBS J. 2005;272(18):4725–4740. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04888.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Lugt T., Weseler A.R., Vrolijk M.F., Opperhuizen A., Bast A. Dietary advanced glycation endproducts decrease glucocorticoid sensitivity in vitro. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):441. doi: 10.3390/nu12020441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee I.-K., Hwang B.S., Kim D.-W., Kim J.-Y., Woo E.-E., Lee Y.-J., Choi H.J., Yun B.-S. Characterization of neuraminidase inhibitors in Korean Papaver rhoeas bee pollen contributing to anti-influenza activities in vitro. Planta Med. 2016;82(6):524–529. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-111631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yi L., Li Z., Yuan K., Qu X., Chen J., Wang G., Zhang H., Luo H., Zhu L., Jiang P. Small molecules blocking the entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into host cells. J. Virol. 2004;78(20):11334–11339. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11334-11339.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X.-x., Wu Q.-f., Yan Y.-l., Zhang F.-l. Inhibitory effects and related molecular mechanisms of total flavonoids in Mosla chinensis maxim against H1N1 influenza virus. Inflamm. Res. 2018;67(2):179–189. doi: 10.1007/s00011-017-1109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evers D.L., Chao C.-F., Wang X., Zhang Z., Huong S.-M., Huang E.-S. Human cytomegalovirus-inhibitory flavonoids: studies on antiviral activity and mechanism of action. Antiviral Res. 2005;68(3):124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu G., Dou J., Zhang L., Guo Q., Zhou C. Inhibitory effects of baicalein on the influenza virus in vivo is determined by baicalin in the serum. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010;33(2):238–243. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rho H.S., Ghimeray A.K., Yoo D.S., Ahn S.M., Kwon S.S., Lee K.H., Cho D.H., Cho J.Y. Kaempferol and kaempferol rhamnosides with depigmenting and anti-inflammatory properties. Molecules. 2011;16(4):3338–3344. doi: 10.3390/molecules16043338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim J.M., Lee E.K., Kim D.H., Yu B.P., Chung H.Y. Kaempferol modulates pro-inflammatory NF-κB activation by suppressing advanced glycation endproducts-induced NADPH oxidase. Age. 2010;32(2):197–208. doi: 10.1007/s11357-009-9124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seong R., Kim J., Shin O. Wogonin, a flavonoid isolated from Scutellaria baicalensis, has anti-viral activities against influenza infection via modulation of AMPK pathways. Acta Virol. 2018;62(1):78–85. doi: 10.4149/av_2018_109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim M.S., Bak Y., Park Y.S., Lee D.H., Kim J.H., Kang J.W., Song H.-H., Oh S.-R. Wogonin induces apoptosis by suppressing E6 and E7 expressions and activating intrinsic signaling pathways in HPV-16 cervical cancer cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2013;29(4):259–272. doi: 10.1007/s10565-013-9251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi E.-J., Lee C.-H., Kim Y.-C., Shin O.S. Wogonin inhibits Varicella-Zoster (shingles) virus replication via modulation of type I interferon signaling and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activity. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;17:399–409. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chi Y.S., Lim H., Park H., Kim H.P. Effects of wogonin, a plant flavone from Scutellaria radix, on skin inflammation: in vivo regulation of inflammation-associated gene expression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;66(7):1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suga Y., Miyajima K., Oikawa T., Maeda J., Usuda J., Kajiwara N., Ohira T., Uchida O., Tsuboi M., Hirano T. Quantitative p16 and ESR1 methylation in the peripheral blood of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2008;20(5):1137–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peretz J., Pekosz A., Lane A.P., Klein S.L. Estrogenic compounds reduce influenza A virus replication in primary human nasal epithelial cells derived from female, but not male, donors. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular Molecular Physiology. 2016;310(5):L415–L425. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00398.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Litterst C.M., Kliem S., Marilley D., Pfitzner E. NCoA-1/SRC-1 is an essential coactivator of STAT5 that binds to the FDL motif in the α-helical region of the STAT5 transactivation domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(46):45340–45351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalkhoven E., Valentine J.E., Heery D.M., Parker M.G. Isoforms of steroid receptor co‐activator 1 differ in their ability to potentiate transcription by the oestrogen receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17(1):232–243. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi M., Muromoto R., Kojima H., Takeuchi S., Kitai Y., Kashiwakura J.-i., Matsuda T. Biochanin A enhances RORγ activity through STAT3-mediated recruitment of NCOA1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;489(4):503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei X., Bai L., Dong L., Liu H., Xing P., Zhou Z., Wu S., Lan K. NCOA2 promotes lytic reactivation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus by enhancing the expression of the master switch protein RTA. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hofman K., Swinnen J., Claessens F., Verhoeven G., Heyns W. The retinoblastoma protein-associated transcription repressor RBaK interacts with the androgen receptor and enhances its transcriptional activity. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;31(3):583–596. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0310583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mantalaris A., Panoskaltsis N., Sakai Y., Bourne P., Chang C., Messing E.M., David Wu J. Localization of androgen receptor expression in human bone marrow. J. Pathol. 2001;193(3):361–366. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(0000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH803>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Becerra-Díaz M., Strickland A.B., Keselman A., Heller N.M. Androgen and androgen receptor as enhancers of M2 macrophage polarization in allergic lung inflammation. J. Immunol. 2018;201(10):2923–2933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hicks B.M., Yin H., Bladou F., Ernst P., Azoulay L. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer and the risk of hospitalisation for community-acquired pneumonia. Thorax. 2017;72(7):596–597. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zou W., Ding F., Niu C., Fu Z., Liu S. Brg1 aggravates airway inflammation in asthma via inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;503(4):3212–3218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu Y., Zhang Y., Wang S., Liu W., Hao C., Wang W. Inhibition effects of patchouli alcohol against influenza a virus through targeting cellular PI3K/Akt and ERK/MAPK signaling pathways. Virol. J. 2019;16(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1266-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang H.-H., Yu W.-Y., Li L., Wu F., Chen Q., Yang Y., Yu C.-H. Protective effects of diketopiperazines from Moslae Herba against influenza A virus-induced pulmonary inflammation via inhibition of viral replication and platelets aggregation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;215:156–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Groskreutz D.J., Monick M.M., Yarovinsky T.O., Powers L.S., Quelle D.E., Varga S.M., Look D.C., Hunninghake G.W. Respiratory syncytial virus decreases p53 protein to prolong survival of airway epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2007;179(5):2741–2747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Manka P., Coombes J., Boosman R., Gauthier K., Papa S., Syn W. Thyroid hormone in the regulation of hepatocellular carcinoma and its microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2018;419:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dentice M., Luongo C., Ambrosio R., Sibilio A., Casillo A., Iaccarino A., Troncone G., Fenzi G., Larsen P.R., Salvatore D. β-Catenin regulates deiodinase levels and thyroid hormone signaling in colon cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(4):1037–1047. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simpson R.J., Bigley A.B., Spielmann G., LaVoy E.C., Kunz H., Bollard C.M. Human cytomegalovirus infection and the immune response to exercise. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2016;22:8–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boomker J.M., Verschuuren E.A., Brinker M.G., de Leij L.F., The T.H., Harmsen M.C. Kinetics of US28 gene expression during active human cytomegalovirus infection in lung-transplant recipients. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;193(11):1552–1556. doi: 10.1086/503779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Froberg M.K., Adams A., Seacotte N., Parker-Thornburg J., Kolattukudy P. Cytomegalovirus infection accelerates inflammation in vascular tissue overexpressing monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. Circ. Res. 2001;89(12):1224–1230. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Freitas A.C., Gurgel A.P., de Lima E.G., São Marcos Bd.F., do Amaral C.M.M. Human papillomavirus and lung cancinogenesis: an overview. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2016;142(12):2415–2427. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Halimi M., Asl S.M., Hejazi M.S., Aghbali A., Hejazi M.E. Human papillomavirus infection in lung vs. Oral squamous cell carcinomas: a polymerase chain reaction study. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2011;14(11):641. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2011.641.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xiong W.-M., Xu Q.-P., Li X., Xiao R.-D., Cai L., He F. The association between human papillomavirus infection and lung cancer: a system review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(56):96419. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hemmat N., Bannazadeh Baghi H. Association of human papillomavirus infection and inflammation in cervical cancer. Pathog. Dis. 2019;77(5) doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftz048. ftz048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ueno S., Sudo T., Oka N., Wakahashi S., Yamaguchi S., Fujiwara K., Mikami Y., Nishimura R. Absence of human papillomavirus infection and activation of PI3K-AKT pathway in cervical clear cell carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2013;23(6):1084–1091. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182981bdc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.