Abstract

Preventive visit rates are low among older adults in the United States. We evaluated changes in preventive visit utilization with Medicare’s introduction of Annual Wellness Visits (AWVs) in 2011. We further assessed how coverage expansion differentially affected older adults who were previously underutilizing the service. The study included Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 to 85 from a mixed-payer multispecialty outpatient healthcare organization in northern California between 2007 and 2016. Data from the electronic health records were used, and the unit of analysis was patient-year (N = 456,281). Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess determinants of “any preventive visit” use. Prior to the AWV coverage (2007–2010), Medicare beneficiaries who were older, with serious chronic conditions, and with a fee-for-services (FFS) plan underutilized preventive visits such that odds ratio (OR) for age groups (vs. age 65–69) ranges from 0.826 (age 70–74) to 0.522 (age 80–85); for Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) (vs. 0 CCI) ranges from 0.77 (1 CCI) to 0.65 (≥2 CCI); and for FFS (vs. HMO) is 0.236. With the Medicare coverage (2011–2016), the age-based gap reduced substantially, but the difference persisted, e.g., OR for age 80–85 (vs. 65–69) is 0.628, and FFS (vs. HMO) beneficiaries still have far lower odds of using a preventive visit (OR = 0.278). The gap based on comorbidity was not reduced. Medicare’s coverage expansion facilitated the use of preventive visit particularly for older adults with more advanced age or with FFS, thereby reducing disparities in preventive visit use.

Keywords: Preventive visit, Insurance coverage, Older adults

1. Introduction

Older Americans use preventive care services at half the recommended rate (McGlynn et al., 2003; National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2010). Accordingly, Healthy People 2020 sets a goal of a 10% increase in the proportion of older adults who receive a core set of preventive services (e.g., influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations, colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy or fecal occult blood test, and mammography for women) (Anon, 2014). These preventive care services can help delay disease onset or progression and, in some cases, prevent diseases from occurring (e.g., immunizations) (National Prevention Strategy, 2011).

Lack of coverage under traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare on preventive visits had been cited as one barrier to delivering preventive care for older adults (Anon, n.d.-a). Routine primary care office visits are typically scheduled for 20 min or less, and face-to-face time with a provider is even shorter (Tai-Seale et al., 2007). Given this limited time, conversation surrounding acute or existing chronic health problems tends to take priority leaving typically little time for in-depth discussions regarding preventive care, such as health education, counseling, and screening (Abbo et al., 2008; Baron, 2010; Lesser and Bazemore, 2009).

Recognizing the need for better preventive care, Medicare introduced the Annual Wellness Visit (AWV) in 2011 under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The AWV requires a comprehensive range of preventive services targeted to older adults (e.g., screening for cognitive and functional impairment), which is beyond the scope of complete physical exam which has been covered and widely used by Medicare HMO beneficiaries (Petroski and Regan, 2009; Anon, n.d.-b). With an AWV, all Medicare beneficiaries would have similar access at no cost to annual preventive visits. Subsequently, there was a marked increase in the use of preventive visits among Medicare FFS beneficiaries in the first few years after introduction of the AWV (Chung et al., 2015; Ganguli et al., 2017).

In this study of Medicare beneficiaries, we investigate who utilized preventive visits during four years before and six years after the introduction of AWV, and how the expanded ACA coverage affected preventive visit utilization. Despite the potential benefits of AWVs, older adults of more advanced age and/or with multiple chronic conditions may be less likely to make a separate preventive visit, as they are already overwhelmed by frequent visits and may prefer receiving preventive care during their problem-oriented visits. On the other hand, for those older adults who rarely see a primary care provider, a no-cost dedicated preventive visit may be perceived as necessary to receive recommended preventive care. Preventive visit utilization may also differ by sociodemographic characteristics given existing disparities in preventive care (Nelson et al., 2002; AHRQ, 2010). A recent study conducted in a Midwest healthcare system (Hu et al., 2015) reported that patients who were older, sicker, or African American were less likely to use preventive visit as compared to younger, healthier and non-Hispanic white patients. Our study setting serves patients from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds including substantial proportions of Asians, Hispanics, and African American, and those with Medicare HMO and FFS insurances.

We hypothesize that (1) older adults are less likely to make a preventive visit as they age; (2) older adults who have multiple serious comorbidities are less likely to make a separate preventive visit; and (3) the impact of coverage expansion is greater among groups of older adults who have been previously underutilizing preventive visits, thereby reducing utilization gaps.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting and study cohorts

The study population consisted of Medicare beneficiaries, aged 65 to 85 years, who were primary-care patients in a large, mixed payer outpatient healthcare organization in northern California. The organization serves more than a million patients annually and is representative of the underlying geographic area in terms of racial and ethnic composition (United States Census Bureau, n.d.). Using data from the electronic health records (EHR), primary care patients were defined each year as those who saw a primary care provider practicing in 30 clinics/departments in the current or previous year. Thus, there are up to ten observations per patient in the study sample that covers four years before (2007–2010) and six years after (2011–2016) the expansion of Medicare’s preventive visit coverage.

All data elements were de-identified according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act requirement; the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the health care organization.

2.2. Measures

Preventive visits were identified based on Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and Medicare’s Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes in billing records. HCPCS codes used for Medicare-covered preventive visits were G0344 (“Welcome to Medicare visit” (WMV) in 2007–2010), G0402 (WMV in 2011–2016), G0438 (initial AWV), and G0439 (subsequent AWVs). Additionally, “complete physical exam” (CPT codes of 99387 and 99397) was included as it has been used widely by Medicare HMO beneficiaries who are covered with or without co-payment; Medicare FFS beneficiaries have to pay the full cost for this type of visit out-of-pocket. Non-preventive, problem-oriented visits to a primary care provider were identified using CPT codes of 99201–99215.

Patients were classified into Medicare FFS and Medicare HMO beneficiaries based on their primary insurance for that year. Most (78.8%) used one insurance throughout the year, and the remainder used two or more: Medicare FFS and Medicare HMO (5.5%), Medicare and Medicaid (0.3%), Medicare and commercial insurance (6.1%), or self-pay and Medicare (9.6%). When multiple insurances were used during a year, the insurance most frequently used (or covering most charges if two were used with equal frequencies) was assigned as the primary insurance. Patient age, sex, and race/ethnicity were based on self-reporting as contained in the EHR.

2.3. Analytical approach

Multilevel logistic regression models were used to estimate predictors of any preventive visit (yes/no) as the dependent variable. Models included patient-level and provider-level random effects to account for multiple observations per patient, nested within provider. Random effects model uses variation within and between patients and within and between providers, and thus all the patients from the sample, regardless whether they made any preventive visit during the study period or not, are included in the estimation.

The main predictor variables were indicators of (1) age category: 65–69 (referent group), 70–74, 75–79, and 80–85, (2) burden of comorbid conditions based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) without age: 0 (referent group), 1, and 2 or more, (3) primary care (non-preventive) visit frequency: 0 (referent group), 1, 2, 3, and 4 or more, and (4) primary insurance: Medicare HMO (referent group) and Medicare FFS. Patient sex and race/ethnicity, and indicators of year were included as covariates.

To estimate differential impact of the new coverage by patient demographic and clinical characteristics, we ran stratified sample analyses with pre-AWV and post-AWV periods separately. For most covariates in the model, the effect size during pre-AWV vs. post-AWV periods differed practically and statistically (Clogg et al., 1995; Paternoster et al., 1998), as indicated by significance of interaction terms of “post-AWV” and each covariate (Likelihood Ratio test: Chi sq = 1548, p < 0.001) (see Appendix Table C). We present results from the stratified analysis which is consistent with the interaction terms model but is easier to interpret. For all the analysis, results with p < 0.001 were considered statistically significant, given sizable sample sizes. Stata 11.1 (College Park, TX) was used to conduct the data analysis.

2.4. Role of the funding source

This work was funded by grants: AHRQ (K01-HS019815) and HCSRN-OAICs AGING Initiative (R24AG045050). The funder had no role in writing the manuscript nor approving its submission for publication.

3. Results

Of 456,281 patient-years (of 108,734 unique patients), a majority was female (59.8%), non-Hispanic white (64.4%), and Medicare FFS beneficiaries (80.7%) (Table 1). In this study setting, Medicare FFS beneficiaries were likely to be younger and healthier than Medicare HMO beneficiaries (Appendix Table A). Overall, 32% made a preventive visit, with an increase from 19% in 2007–2010 to 38% in 2011–2016 (Table 1). The unadjusted rate of preventive visits declined with age and with increasing CCI. Patients who made frequent primary care visits were less likely to make a separate preventive visit than those who did not. Non-Hispanic white patients were more likely than African-American or Hispanic patients to make a preventive visit. Medicare FFS beneficiaries were less likely to make a preventive visit than HMO beneficiaries.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population and rates of preventive visits.

| % of total person-years | Preventive visit rates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All years* (2007–2016) | Pre-AWV (2007–2010) | Post AWV (2011–2016) | Pre-post difference** | ||

| N = 456,281 | 456,281 | 147,835 | 308,446 | ||

| Overall | 32% | 19% | 38% | 19% | |

| Age | |||||

| 65–69 | 26.6% | 38% | 26% | 42% | 15% |

| 70–74 | 25.4% | 35% | 21% | 41% | 20% |

| 75–79 | 20.1% | 32% | 21% | 38% | 17% |

| 80–85 | 27.9% | 23% | 13% | 31% | 18% |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 40.2% | 33% | 20% | 39% | 19% |

| Female | 59.8% | 31% | 19% | 37% | 19% |

| CCI, no age | |||||

| 0 | 53.2% | 36% | 23% | 43% | 20% |

| 1 | 24.3% | 29% | 15% | 35% | 20% |

| 2 + | 22.5% | 27% | 14% | 31% | 17% |

| Visit frequency | |||||

| 0 | 19.0% | 54.3% | 38.6% | 59.7% | 21.1% |

| 1 | 25.7% | 32.3% | 20.8% | 36.9% | 16.1% |

| 2 | 18.2% | 28.9% | 17.5% | 34.2% | 16.7% |

| 3 | 12.6% | 25.8% | 15.7% | 31.3% | 15.6% |

| 4+ | 24.6% | 19.7% | 11.4% | 25.4% | 14.0% |

| Insurance type | |||||

| Medicare FFS | 80.7% | 29% | 13% | 35% | 22% |

| Medicare HMO | 19.3% | 46% | 36% | 54% | 17% |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 64.4% | 34% | 22% | 39% | 17% |

| African-American/Black | 13.6% | 30% | 21% | 34% | 13% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.6% | 28% | 17% | 32% | 15% |

| Asian | 13.8% | 35% | 21% | 41% | 20% |

| Other/refused/unknown | 14.9% | 24% | 12% | 34% | 22% |

Abbreviations: AWV: CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index, Annual Wellness Visit, FFS: Fee-for-Services, HMO: Health Maintenance Organization.

The differences among subgroups (each based on age, sex, CCI, insurance, and race/ethnicity) were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

All pre-post differences were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

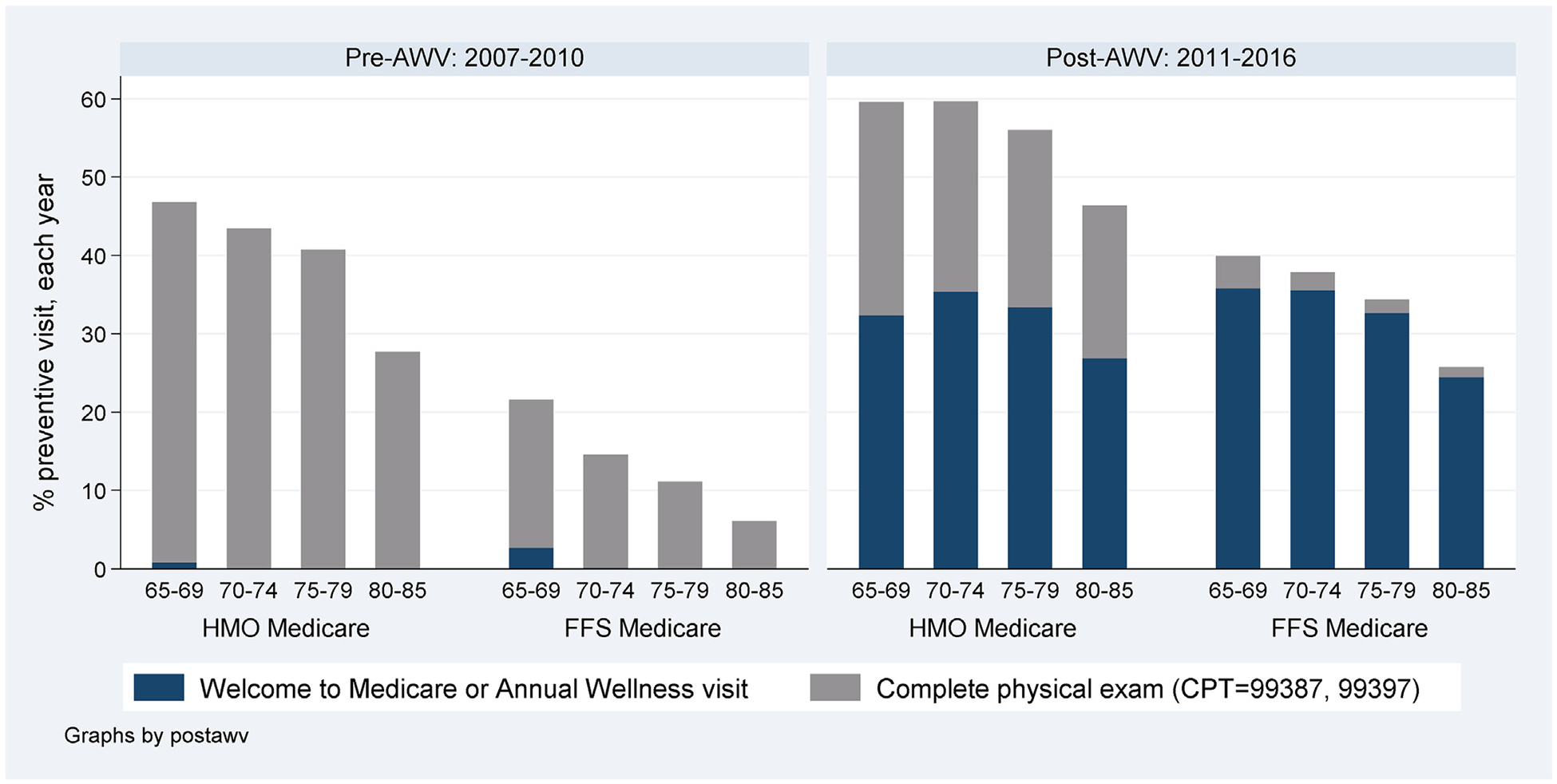

As expected, preventive visit rates increased from 2011 to 2016. Generally, there was a greater increase among the patient groups with initially lower preventive visit use (Table 1). By age, there were 20 percentage-point increase among people aged 70–74 versus a 15 percentage-point increase for those aged 65–69. The increase in rates was smaller for patients with higher comorbidity burden, but, in relative terms, the increase was larger for patients with higher comorbidity burden (121% increase for CCI ≥ 2) than for those with lower burden (87% increase for CCI = 0). The gap based on race/ethnicity slightly widened, however. For example, the difference between non-Hispanic white and African Americans increased from 1 percentage-point pre-AWV to 5 percentage-point post-AWV. For Medicare FFS and Medicare HMO beneficiaries of all age groups, the rate increased, driven by the AWV utilization (Fig. 1). For Medicare HMO beneficiaries, preventive visits coded as “complete physical exams” were still frequent but some were replaced by AWV.

Fig. 1.

Pre- and post-AWV changes in the preventive visit use, by insurance type.

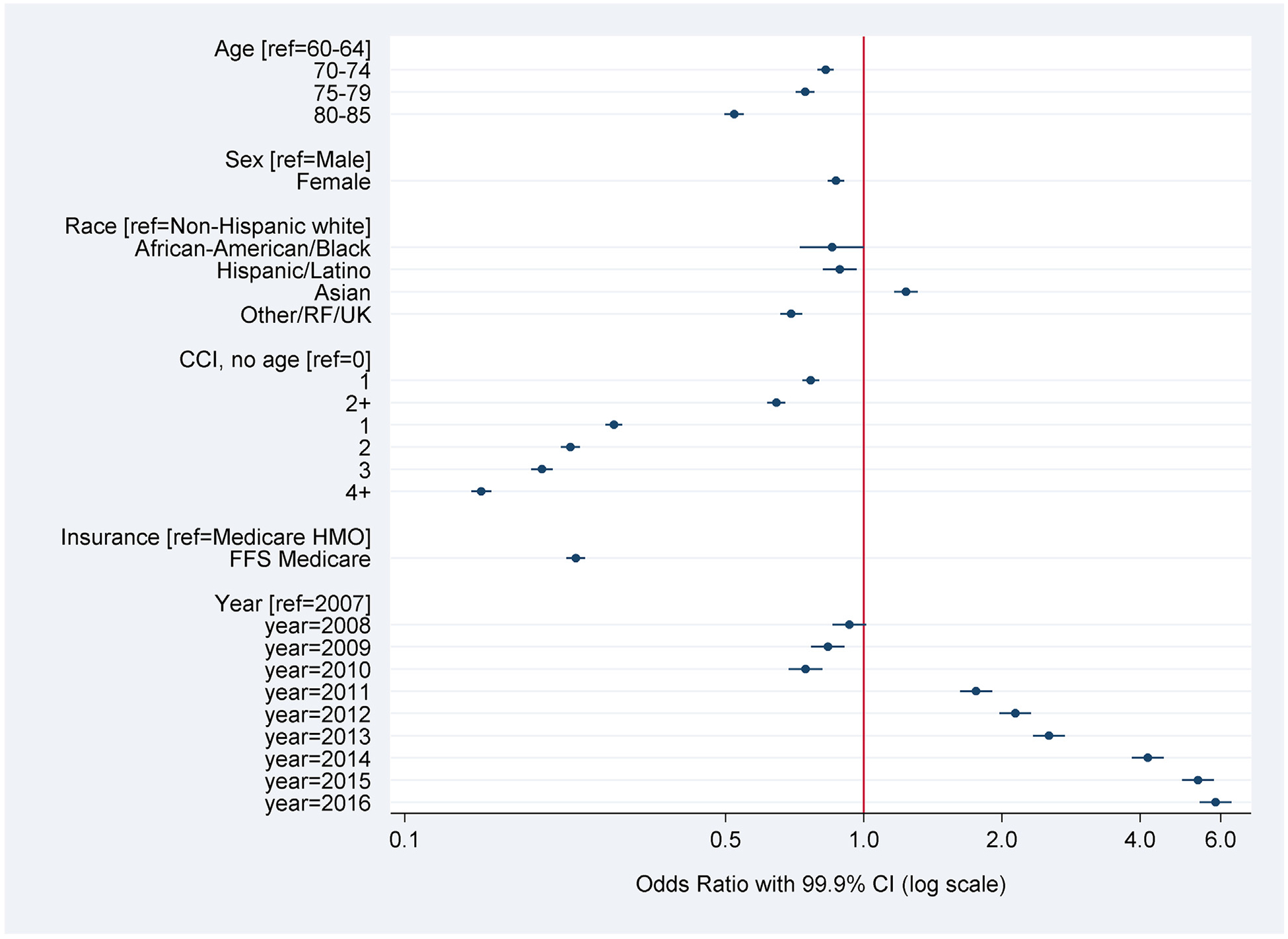

Results from multi-level logistic regression models, after controlling for confounders, are consistent with the unadjusted results (Fig. 2). Compared to those 65–69 years old, all older groups had much lower odds of a preventive visit, with odds ratios (ORs) ranging from 0.522 (age 80–85) to 0.826 (age 70–74). Increased comorbidity burden was strongly associated with lower odds of a preventive visit (OR (vs. 0 CCI): 0.645 (≥2 CCI) and 0.766 (1 CCI)). Similarly, increased frequency of non-preventive primary care visits was associated with lower odds of a preventive visit (OR (vs. 0 visit) ranging from 0.147 (≥4 visits) to 0.285 (1 visit)). Compared to non-Hispanic whites, African-Americans and Hispanics had lower while Asians had higher odds of a preventive visit (OR: 0.853 (African-American), 0.886 (Hispanic), and 1.236 (Asian)). The odds for Medicare HMO beneficiaries (OR: 0.236) were much higher than Medicare FFS beneficiaries. There was a slight decline in preventive visit use between 2007 and 2010, and then the rate increased dramatically, with OR (vs. 2007) ranging from 1.758 (2011) to 5.841 (2016). See Appendix Table B for odds ratios and confidence intervals.

Fig. 2.

Demographic and clinical factors associated with preventive visit use: Results from a multi-level logistic regression with patient and provider random effects model.

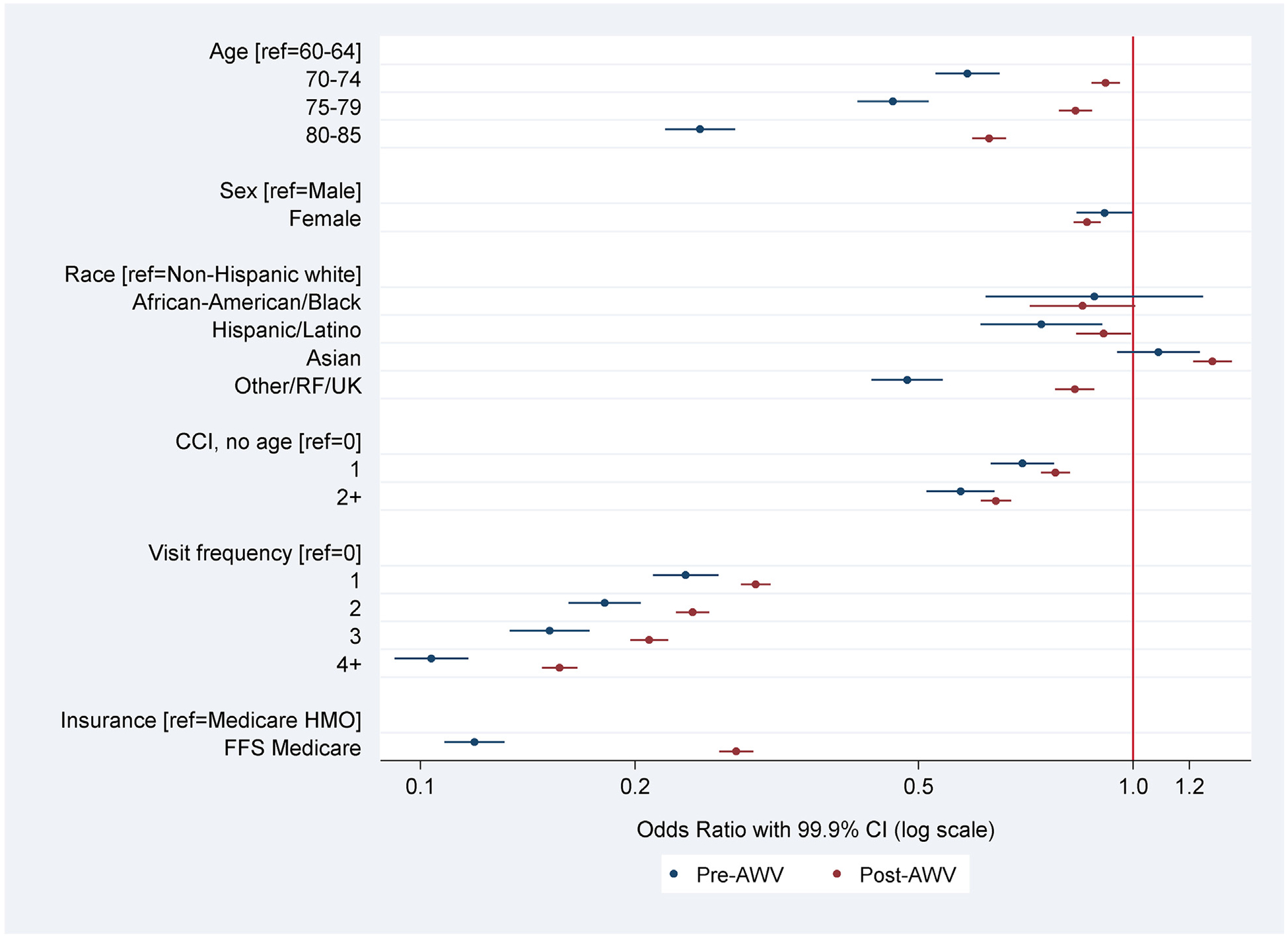

Results from separate regression analysis for pre-AWV and post-AWV periods (Fig. 3) indicate that the age difference in preventive visit use was attenuated with AWV (e.g., OR for the age 80–85 group were0.247 pre-AWV and 0.628 post-AWV). By insurance type, OR for Medicare FFS (vs. Medicare HMO) rose from 0.119 pre-AWV to 0.278 post-AWV. The gap narrowed for Hispanics, from 0.744 pre-AWV to0.909 post-AWV, but the gap slightly widened for African-Americans, 0.883 pre-AWV to 0.849 post-AWV, and reversely widened for Asians, 1.086 pre-AWV to 1.214 post-AWV, as compared to non-Hispanic whites. Difference based on comorbid burden persisted at a similar level after the policy change. The gap based on visit frequency reduced after the introduction of AWV, e.g., ORs from 0.104 pre-AWV to 0.157 post-AWV for those who made ≥4 visits. See Appendix Table C for odds ratios and confidence intervals.

Fig. 3.

Demographic and clinical differences in preventive visit use: Changes between Pre-AWV and Post-AWV periods.

4. Discussion

These results show substantial disparities in the use of preventive visits among older Americans within an outpatient healthcare organization in northern California. Preventive visits are underutilized among the older-old, those with high comorbidity burden or frequent primary care visits, African-American or Hispanic patients, and Medicare FFS beneficiaries. It is promising, however, that the older-old, those with Medicare FFS, or frequent users of healthcare system are generally the groups most positively affected by the ACA’s preventive visit coverage expansion. The pre-post AWV differences in preventive visit rates are substantial, and the rate continues to rise each year throughout the six years of post-AWV period, which is beyond what would have been due to regression to the mean.

The coverage expansion brought many adults of advanced age to preventive visits, reducing the age-based gap. While some preventive services are recommended by US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) only up to a certain age (e.g., screening mammography until age 74 for women with average risk) (USPSTF, 2014), many other AWV services are beneficial to people beyond their 70s. Required elements of AWV include screening for depression, cognitive impairment, and high risk of fall; these conditions are highly prevalent in the older-old group, and fall risk increases dramatically with age (Gillespie et al., 2012; Peel et al., 2002; Cummings and Melton, 2002). Medicare’s AWV thus could provide important counseling and other preventive services particularly important for the well-being of older-old adults.

We do not expect the age-based gap to be completely closed, however. Many older-old adults often have limited life expectancy. For patients with terminal illness, commonly recommended preventive measures (e.g., breast cancer screening) are not recommended as potential harm may exceed potential benefit. Further, many older adults are already making frequent medical visits to manage existing conditions, and may prefer receiving needed preventive care during their problem-oriented visits rather than making a separate preventive visit. Consistently, we found that frequent users of healthcare system are less likely to make a preventive visit. Given the shorter visit length of problem-oriented visits, acute or chronic conditions may dominate the conversation leaving little time to thoroughly address preventive needs. Additional research should explore what is accomplished during dedicated preventive visits and the extent to which preventive care is delivered during problem-oriented visits (CPT = 99201–99215) in the absence of a preventive visit.

Our finding of lower preventive visit rates among Hispanic and African-American older adults is consistent with the reported racial/ethnic disparity in recommended preventive care (Nelson et al., 2002; AHRQ, 2010; Hu et al., 2015). On the other hand, we found that Asians were more likely than non-Hispanic whites in the same setting to use preventive visits and that the coverage expansion did not help reducing the disparities. Our findings warrant further investigation into the reasons for these utilization rate differences among different racial/ethnic groups so that there can be more targeted outreach efforts to improve uptake of preventive visits and reduce the gap in racial/ethnic preventive care disparities.

Despite a steep increase, the rate of preventive visit utilization among Medicare FFS beneficiaries is still far below the level of Medicare HMO beneficiaries (Fig. 1), even after controlling for observed differences in demographic and clinical differences based on insurance type. Further, it is notable that post-AWV increase in preventive visit rate was substantial among HMO beneficiaries who were not financially affected by the new coverage. This may be in part due to the promotion of AWV by Medicare, regardless of plan type, and outreach by the healthcare system. Thus, even with full coverage, the preventive visit utilization gap based on insurance type might continue to persist. Another potential explanation might be that HMO beneficiaries are inherently more prevention-oriented as they chose HMO policies which generally promote preventive care. However, this may not be the case as among this study sample, Medicare FFS beneficiaries were likely to be healthier than HMO beneficiaries.

The AWV is designed to better meet the specific needs of older adults while the complete physical exam has been criticized as not being age-specific (Mehrotra and Prochazka, 2015; Aronson, 2017). While the increase in preventive visits among HMO beneficiaries was largely attributable to the additional AWV use, HMO beneficiaries (even those who are oldest-old) still utilize complete physical exams, less targeted preventive visit than AWV, at a similar rate as before. As HMO contracts are based on per capita rather than per service, how each visit is coded does not matter financially for the healthcare system. On the other hand, individual providers are compensated on work RVU basis and use the same coding rule regardless of patient insurance type. Thus, it may be possible that providers are reluctant to offer HMO patients an AWV due to its complicated coding requirements. Future research should understand how the two types of preventive visits are implemented differently, and how they are tailored to meet differential age-specific needs of patients, in clinical practices.

The study has several limitations. First, we used data from a single organization serving a relatively healthy population as compared to the national average. Patterns from other organizations with different patient demographic characteristics and clinical needs may differ from ours. It is reassuring that the rate of preventive visits at our organization prior to and immediately following AWV introduction is similar to the national rate (Petroski and Regan, 2009). Additionally, the critical advantage of the study setting is that it allows informative internal comparisons, particularly with its incentive structure – patients representing both HMO and FFS coverage and providers being paid based on work relative value units (wRVUs). As such, the study is of relevance to other study settings since it reflects the incentives faced by most patients and providers in the U.S. With observational data, it is extremely challenging to isolate the effects of a broad policy change from other simultaneous changes that may also influence outcomes of interest. By having older adults at the same study setting with other types of insurance coverage as a comparison group, we were able to identify the impact of this policy change, controlling for contemporaneous confounding factors.

Second, we only assessed the rate of preventive visit use, and did not look into the content of the visits. As noted above, preventive care could instead be being offered during problem-oriented visits. An increase in preventive visit use does not tell us whether it led to changes in the uptake of preventive interventions (e.g., immunizations, recommended screening, receipt of medical care for depression, removal of fall hazards in the home), in improved health behaviors (e.g., better diet, quit smoking) or in more through, in-depth discussions about prevention.

Third, the ultimate goal of expanding preventive visit coverage is improved health and quality of life of seniors. While there is general agreement on benefits of recommended preventive services, it is unknown whether preventive visits lead to inappropriate or unnecessary procedures which can cause more harm than good. Further, longer term outcomes (e.g., avoidance of preventable illnesses, lower mortality, and better quality of life) of preventive visit need to be examined to fully assess the impact of the policy change.

In conclusion, as before the expansion in coverage, Medicare FFS beneficiaries and older-old adults are less likely to make a preventive visit, but their preventive visit use increased disproportionately with the AWV coverage, reducing disparity in preventive visit utilization. Seniors with a high comorbidity burden may instead be continuing to use problem-oriented visits to get preventive services.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (K01HS019815) and National Institutes of Health (R24AG045050).

Appendix. Table A.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of Medicare FFS and HMO beneficiaries in the study sample

| All | Medicare FFS N = 368,213 | Medicare HMO N = 8 8,068 | Standardized mean difference* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 65–69 | 26.6% | 28.8% | 17.6% | 0.37924 |

| 70–74 | 25.4% | 26.5% | 20.9% | |

| 75–79 | 20.1% | 19.8% | 21.4% | |

| 80–85 | 27.9% | 25.0% | 40.1% | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 40.2% | 40.2% | 40.3% | 0.00033 |

| Female | 59.8% | 59.8% | 59.8% | |

| CCI (no age) | ||||

| 0 | 53.2% | 53.6% | 51.7% | 0.06701 |

| 1 | 24.3% | 24.5% | 23.5% | |

| 2+ | 22.5% | 22.0% | 24.8% | |

| Visit frequency | ||||

| 0 | 19.0% | 19.1% | 18.6% | 0.10733 |

| 1 | 25.7% | 26.3% | 22.9% | |

| 2 | 18.2% | 18.4% | 17.7% | |

| 3 | 12.6% | 12.4% | 13.0% | |

| 4+ | 24.6% | 23.8% | 27.8% | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| NHW | 64.4% | 64.3% | 64.9% | 0.09631 |

| Black | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.5% | |

| Latino | 5.6% | 5.2% | 7.1% | |

| Asian | 13.8% | 14.2% | 12.2% | |

| Other/RF/UK | 14.9% | 15.0% | 14.3% | |

P < 0.01

Appendix. Table B.

Results from multi-level logistic regression with patient and provider random effects – overall sample

| Dependent variable: made a preventive visit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variables | OR | 99.9% CI low | 99.9% CI high |

| Age (ref = 65–69) | |||

| 70–74 | 0.826 | 0.793 | 0.860 |

| 75–79 | 0.745 | 0.711 | 0.781 |

| 80–85 | 0.522 | 0.497 | 0.548 |

| Female (ref = male) | 0.870 | 0.835 | 0.906 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = NHW) | |||

| African-American/Black | 0.853 | 0.726 | 1.002 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.886 | 0.814 | 0.965 |

| Asian | 1.236 | 1.165 | 1.312 |

| Other/RF/UK | 0.695 | 0.657 | 0.735 |

| CCI with no age (ref = 0) | |||

| 1 | 0.766 | 0.734 | 0.800 |

| 2+ | 0.645 | 0.616 | 0.675 |

| Visit frequency (ref = 0) | |||

| 1 | 0.285 | 0.273 | 0.298 |

| 2 | 0.229 | 0.219 | 0.241 |

| 3 | 0.199 | 0.188 | 0.210 |

| 4+ | 0.147 | 0.139 | 0.154 |

| Medicare FFS (ref = HMO) | 0.236 | 0.225 | 0.247 |

| Year (ref = 2007) | |||

| 2008 | 0.930 | 0.855 | 1.012 |

| 2009 | 0.835 | 0.767 | 0.909 |

| 2010 | 0.747 | 0.686 | 0.813 |

| 2011 | 1.758 | 1.622 | 1.906 |

| 2012 | 2.139 | 1.975 | 2.316 |

| 2013 | 2.533 | 2.337 | 2.746 |

| 2014 | 4.159 | 3.838 | 4.506 |

| 2015 | 5.348 | 4.936 | 5.794 |

| 2016 | 5.841 | 5.390 | 6.329 |

| Intercept | 0.735 | 0.589 | 0.916 |

| Random effects | |||

| Provider-level variance (σu prov2) | 2.488 | 1.983 | 3.121 |

| Patient-level variance (σu patient2) | 1.268 | 1.210 | 1.328 |

| Number of observations | 439,800 | ||

| Number of providers | 1703 | ||

| Number of patients | 130,052 | ||

Appendix. Table C.

Results from multi-level logistic regression with patient and provider random effects: separately for pre and post AWV periods

| Dependent variable: made a preventive visit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-AWV period (2007–2010) | Post-AWV period (2011–2016) | |||||

| Explanatory variables | OR | 95% CI low | 95% CI high | OR | 95% CI low | 95% CI high |

| Age (ref = 65–69) | ||||||

| 70–74 | 0.586 | 0.528 | 0.650 | 0.915 | 0.874 | 0.958 |

| 75–79 | 0.460 | 0.410 | 0.517 | 0.830 | 0.787 | 0.876 |

| 80–85 | 0.247 | 0.220 | 0.277 | 0.628 | 0.595 | 0.663 |

| Female (ref = male) | 0.912 | 0.833 | 0.998 | 0.862 | 0.825 | 0.901 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = NHW) | ||||||

| African-American/Black | 0.883 | 0.621 | 1.255 | 0.849 | 0.716 | 1.007 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.744 | 0.611 | 0.906 | 0.909 | 0.832 | 0.994 |

| Asian | 1.086 | 0.950 | 1.241 | 1.293 | 1.214 | 1.376 |

| Other/RF/UK | 0.482 | 0.430 | 0.541 | 0.828 | 0.777 | 0.883 |

| CCI with no age (ref = 0) | ||||||

| 1 | 0.700 | 0.632 | 0.775 | 0.778 | 0.743 | 0.816 |

| 2+ | 0.573 | 0.513 | 0.640 | 0.642 | 0.611 | 0.675 |

| Visit frequency (ref = 0) | ||||||

| 1 | 0.236 | 0.212 | 0.262 | 0.295 | 0.282 | 0.310 |

| 2 | 0.181 | 0.161 | 0.204 | 0.241 | 0.228 | 0.254 |

| 3 | 0.152 | 0.133 | 0.173 | 0.209 | 0.197 | 0.223 |

| 4+ | 0.104 | 0.092 | 0.117 | 0.157 | 0.148 | 0.166 |

| Medicare FFS (ref = HMO) | 0.119 | 0.108 | 0.131 | 0.278 | 0.263 | 0.293 |

| Year (ref = 2007) | ||||||

| 2008 | 0.895 | 0.814 | 0.985 | |||

| 2009 | 0.771 | 0.700 | 0.849 | |||

| 2010 | 0.665 | 0.603 | 0.734 | |||

| 2011 | ||||||

| 2012 | 1.202 | 1.133 | 1.275 | |||

| 2013 | 1.418 | 1.334 | 1.506 | |||

| 2014 | 2.284 | 2.151 | 2.425 | |||

| 2015 | 2.897 | 2.728 | 3.075 | |||

| 2016 | 3.140 | 2.957 | 3.335 | |||

| Intercept | 6.048 | 4.652 | 7.862 | 0.927 | 0.735 | 1.168 |

| Random effects | ||||||

| Provider-level variance (σu prov2) | 1.371 | 1.032 | 1.821 | 2.648 | 2.093 | 3.350 |

| Patient-level variance (σu patient2) | 2.226 | 2.030 | 2.441 | 1.135 | 1.072 | 1.202 |

| Number of observations | 136,702 | 303,098 | ||||

| Number of providers | 574 | 1594 | ||||

| Number of patients | 56,781 | 109,075 | ||||

Appendix. Table D.

Results from multi-level logistic regression: post-AWV interacted with all covariates

| Dependent variable: made a preventive visit | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory variables | OR | 95% CI low | 95% CI high |

| Age (ref = 65–69) | |||

| 70–74 | 0.639 | 0.586 | 0.696 |

| 75–79 | 0.537 | 0.489 | 0.590 |

| 80–85 | 0.345 | 0.315 | 0.377 |

| Female (ref = male) | 0.882 | 0.823 | 0.946 |

| Race/ethnicity (ref = NHW) | |||

| African-American/Black | 1.029 | 0.777 | 1.362 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.851 | 0.727 | 0.997 |

| Asian | 1.121 | 1.011 | 1.242 |

| Other/RF/UK | 0.558 | 0.508 | 0.612 |

| CCI with no age (ref = 0) | |||

| 1 | 0.718 | 0.660 | 0.780 |

| 2+ | 0.617 | 0.564 | 0.675 |

| Visit frequency (ref = 0) | |||

| 1 | 0.243 | 0.222 | 0.266 |

| 2 | 0.187 | 0.170 | 0.207 |

| 3 | 0.161 | 0.144 | 0.179 |

| 4+ | 0.118 | 0.107 | 0.130 |

| Medicare FFS (ref = HMO) | 0.158 | 0.147 | 0.170 |

| Post-AWV | 1.101 | 0.971 | 1.249 |

| Post-AWV interacted with: | |||

| Age 70–74 | 1.556 | 1.411 | 1.717 |

| Age 75–79 | 1.687 | 1.517 | 1.875 |

| Age 80–85 | 1.793 | 1.622 | 1.982 |

| Female | 0.975 | 0.907 | 1.048 |

| African-American/Black | 0.799 | 0.595 | 1.072 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.054 | 0.894 | 1.242 |

| Asian | 1.143 | 1.028 | 1.270 |

| Other/RF/UK | 1.448 | 1.304 | 1.608 |

| CCI = 1 | 1.156 | 1.055 | 1.265 |

| CCI = 2 + | 1.126 | 1.022 | 1.240 |

| Visit frequency (ref = 0) | |||

| Visit frequency = 1 | 1.181 | 1.068 | 1.306 |

| Visit frequency = 2 | 1.241 | 1.111 | 1.385 |

| Visit frequency = 3 | 1.250 | 1.106 | 1.413 |

| Visit frequency = 4+ | 1.253 | 1.124 | 1.396 |

| Medicare FFS | 2.107 | 1.947 | 2.280 |

| Intercept | 1.680 | 1.345 | 2.099 |

| Random effects | |||

| Provider-level variance (σu prov2) | 2.167 | 1.724 | 2.724 |

| Patient-level variance (σu patient2) | 1.227 | 1.171 | 1.286 |

| Number of observations | 439,800 | ||

| Number of providers | 1703 | ||

| Number of patients | 130,052 | ||

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Abbo ED, Zhang Q, Zelder M, Huang ES, 2008. The increasing number of clinical items addressed during the time of adult primary care visits. J. Gen. Intern. Med 23, 2058–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ, 2010. National healthcare quality and disparities reports. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqrdr10/qrdr10.html.

- Anon, 2014. 2020 topics & objectives: older adults data details. In: Healthy People 2020,Available at. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/DataDetails.aspx?topicId=31.

- Anon Benefits for seniors of new affordable care act rules on expanding prevention coverage. Available at. http://cpehn.org/sites/default/files/resource_files/hhsprevseniors.pdf, Accessed date: 27 August 2015.

- Anon Your guide to Medicare preventive services. Available at. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/MPSGuideErrata.pdf, Accessed date: 1 March 2018.

- Aronson L, 2017. Opinion | stop treating 70- and 90-year-olds the same. In: The NewYork Times. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RJ, 2010. What’s keeping us so busy in primary care? A snapshot from one practice. N. Engl. J. Med 362, 1632–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, et al. , 2015. Medicare annual preventive care visits: use increased among feefor-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Aff. 34, 11–20 (Proj. Hope). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A, 1995. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. Am. J. Sociol 100, 1261–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SR, Melton LJ, 2002. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359, 1761–1767 (Lond. Engl.). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli I, Souza J, McWilliams JM, Mehrotra A, 2017. Trends in use of the USMedicare annual wellness visit, 2011–2014 JAMA 317, 2233–2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie LD, et al. , 2012. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. (CD007146). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Jensen GA, Nerenz D, Tarraf W, 2015. Medicare’s annual wellness visit in a large health care organization: who is using it? Ann. Intern. Med 163, 567–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser LI, Bazemore AW, 2009. Improving the delivery of preventive services toMedicare beneficiaries. JAMA 302, 2699–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn EA, et al. , 2003. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med 348, 2635–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra A, Prochazka A, 2015. Improving value in health care—against the annual physical. N. Engl. J. Med 373, 1485–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2010. Summary Tables. Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- National Prevention Strategy, 2011. America’s Plan for Better Health and Wellness. National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AR, Smedley BD, Stith AY, et al. , 2002. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (Full Printed Version). National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A, 1998. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36, 859–866. [Google Scholar]

- Peel NM, Kassulke DJ, McClure RJ, 2002. Population based study of hospitalised fall related injuries in older people. Inj. Prev. J. Int. Soc. Child Adolesc. Inj. Prev 8, 280–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroski CA, Regan JF, 2009. Use and knowledge of the new enrollee ‘welcome to Medicare’ physical examination benefit. Health Care Financ. Rev 30, 71–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W, 2007. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv. Res 42, 1871–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau Modified race data 2010. Available at. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2010/demo/popest/modified-race-data-2010.html (Accessed: 11th June 2018).

- USPSTF, 2014. USPSTF A and B Recommendations. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. [Google Scholar]