Abstract

Hypervigilance, a state of heightened awareness and watchfulness, is a consequence of violence that has been linked to adverse psychosocial outcomes. Although well documented in veteran populations, it remains poorly quantified in community populations that are exposed to high levels of neighborhood violence. In 2018, in-person surveys of 504 adults were conducted in Chicago to assess the relationships between hypervigilance and exposure to neighborhood violence, including community and police altercations. Exposure to police violence was associated with a 9.8-percentage-point increase in the hypervigilance score (on a 100-point scale), nearly twice that associated with exposure to community violence (a 5.5-percentage-point increase). Among participants who reported having had a police stop, experiencing the stop as a traumatic event (defined as an exposure to actual or threatened death or serious injury) was associated with a 20.0-percentage-point increase in the hypervigilance score. Scoring in the highest quartile of hypervigilance was associated with higher systolic blood pressure (an increase of 8.6 mmHg). Understanding hypervigilance and, importantly, its linkages with violence and health may help inform policing practices and health care responses to violence in urban communities.

Introduction

Hypervigilance is a state of heightened awareness and watchfulness that has been characterized in survivors of trauma and violence.1 Hypervigilance is defined as the feeling of being constantly on guard for the purpose of detecting potential danger, even when the risk of danger is low.2 For people exposed to threat of danger, hypervigilance can fulfill a survival function and increase preparedness.1 However, excessive hypervigilance, especially for a wide range of danger cues, can be maladaptive. For example, hypervigilance has been associated with a number of negative cognitive and behavioral consequences, including attentional bias, memory impairment, and difficulty with emotional regulation.3 It also serves to maintain anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with anxiety increasing hypervigilance for threat, which leads to greater threat detection and thus more future anxiety and hypervigilance.1 Physiologically, excessive hypervigilance can lead to autonomic arousal4 as well as overreactivity in brain regions related to threat detection.5

While hypervigilance has been documented in veteran populations with PTSD,6 it has not been well characterized in community populations with exposure to neighborhood violence. Neighborhood violence is defined as acts of interpersonal violence that take place in public spaces, such as gun violence, gang-related incidents, robberies, and sexual assaults.7 In one study in Chicago, nearly half of black adolescents reported having witnessed a violent death,8 which is similar to documented rates of witnessing in some war-torn countries.9 Recent high-profile police shootings and controversies surrounding actual and alleged race-based law enforcement incidents have also increased awareness of police violence in many high-poverty black neighborhoods. While neighborhood violence is typically thought of as violence between community members, police violence is increasingly considered another manifestation of neighborhood violence. In one qualitative study, black youth identified excessive policing and surveillance in their neighborhoods as a form of race-based violence.10

In previous qualitative work, hypervigilance emerged as a pervasive response to living in these types of adverse environments.11,12 In one study, participants noted that “you have to have your guard up” and “be aware for survival”12(p[1915]) to avoid violent victimization. Few studies have quantified hypervigilance in these types of neighborhood settings or distinguished between the types of neighborhood violence (community versus police violence) experienced by residents. The literature has also focused significant attention on stress response pathways, which trigger adrenergic responses and neurophysiological changes in response to hypervigilance or trauma.5,13 In a meta-analysis of twenty-six studies of people with PTSD, hypervigilance symptoms were associated with elevated heart rate reactivity to threatening stimuli.13 However, to our knowledge, few studies have examined relationships between hypervigilance and physical health conditions such as obesity and hypertension, which epidemiological studies often link to violence exposure.14,15

The purpose of this study was to examine exposure to various types of neighborhood violence, including both community and police altercations, and their associations with hypervigilance in a sample of predominantly black urban-dwelling adults. We hypothesized that there was a positive association between hypervigilance and exposure to both community and police violence in this high-risk sample. As a secondary aim, we examined relationships between hypervigilance and objective health measurements, including body mass index (BMI, measured as kg/m2) and systolic blood pressure (BP, measured as mmHg), abstracted from the electronic health record. Allostatic load theory suggests that psychosocial stress elicits hormonal and cardiovascular responses that may lead to metabolic and autonomic dysregulation over time.16 Based on these theories, we also hypothesized that there was a positive association between higher hypervigilance scores and elevated BMI and BP.

Study Data And Methods

We recruited a sample of adult patients, as part of the Chicago Violence, Neighborhoods, and Health Study, from two medical clinics in Chicago in the period June–December 2018. Medical clinics were purposefully selected because they were located in geographic epicenters of violent crime on Chicago’s South and West Sides. Based on formal community area designations used by the City of Chicago to approximate organic neighborhood boundaries,17 the South Side epicenter had 473,207 residents (71 percent of whom were black) in twenty-one community areas.18 The West Side epicenter had 481,491 residents (44 percent of whom were black and 35 percent of whom were Hispanic or Latino) in nine community areas.18

Participants were recruited consecutively to complete an hour-long, in-person survey. Eligibility criteria included being at least age eighteen, having a Chicago-based residential address, and being registered as a patient at the clinical site. Surveys were administered verbally by a research assistant or using computer-assisted personal interviewing software. All participants received a $20 gift card for completing the survey.

This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline19 and was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board with written documentation of informed consent.

Measures

Lifetime violence exposure, including community and police violence exposure, was the primary independent variable, measured using items from the Brief Trauma Questionnaire.20 The questionnaire was designed and is used by the Department of Veterans Affairs to assess traumatic exposure based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V), criterion A definition of a traumatic event. Criterion A is defined as any exposure to actual or threatened death or serious injury. An event is considered “traumatic” when a person perceives or experiences it as threatening, independent of the presence of an objective threat. Participants were asked about direct exposure to community violence (“Have you ever been [mugged or robbed or physically attacked or beaten] by anyone, including friends, family members, or strangers?”), indirect exposure via witnessing (“Have you ever witnessed a situation in which someone was seriously injured or killed, or have you feared someone would be seriously injured or killed?”), and indirect exposure via the death of a close friend or family member (“Has a close friend or family member died violently, for example, in an altercation, mugging, or attack?”).

We also asked about lifetime exposure to police violence, using the following questions: “Have you ever had a violent interaction with the police, for example, been attacked, beaten, or accosted?” “Have you ever witnessed a situation in which someone was seriously injured or killed or you feared someone would be seriously injured or killed by police?” “Has a close friend or family member been seriously injured or killed in an altercation with the police?” As a secondary independent variable of interest, we queried participants about police stops (“Have you ever been stopped by the police?”).21 For all participants who responded yes, we used the criterion A follow-up item from the Brief Trauma Questionnaire (“Did you think your life was in danger or you might be seriously injured?”). Participants who answered yes to the follow-up question were classified as having had exposure to a traumatic police stop. All measures were analyzed as binary variables (exposure or nonexposure).

Hypervigilance was the primary dependent variable, measured using the Brief Hypervigilance Scale.22 This is the only known scale of hypervigilance that has been validated in a community-dwelling sample. In the validation study, scoring 20 points higher (on a 100-point scale), on average, was clinically associated with PTSD compared to no PTSD. However, studies of more proximal outcomes, which may have lower point thresholds, are very limited. The scale contains five items (each on a five-point Likert scale): “As soon as I wake up and for the rest of the day, I am watching for signs of trouble,” “When I am outside, I think ahead about what I would do if someone would try to surprise or harm me,” “I notice that when I am in public or new places, I need to scan the crowd or surroundings,” “When I am in public, I feel overwhelmed because I cannot keep track of everything going on around me,” and “I feel that if I don’t stay alert and watchful, something bad will happen.” For comparative inference, we normalized the Brief Hypervigilance Scale to a 100-point scale and classified scores into four hypervigilance quartiles: low, medium, high, and very high.

BMI and BP were secondary dependent variables of interest. Objective measurements were abstracted from the participants’ electronic health records and analyzed as continuous variables.

Statistical Analyses

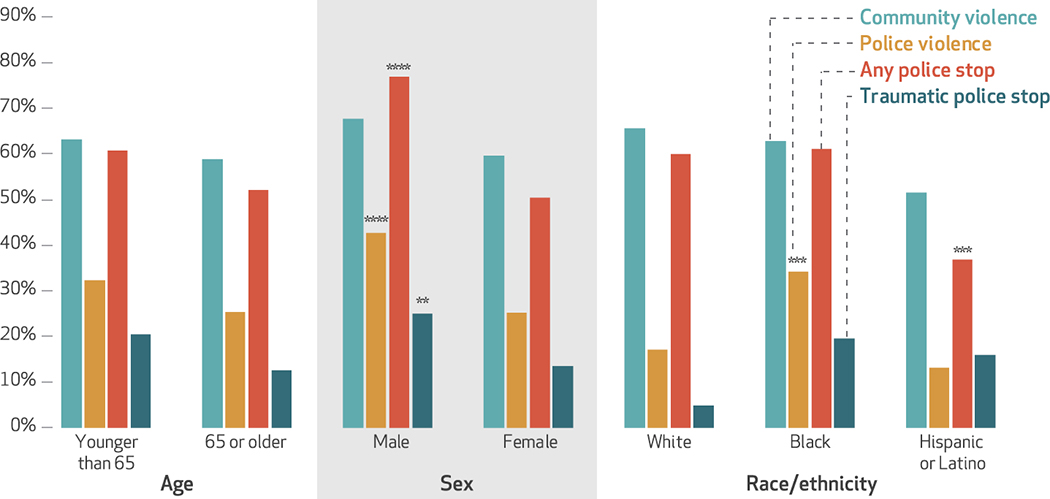

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the sample. Bar graphs were used to explore differences in types of violence exposure (community violence, police violence, police stops, and traumatic police stops) by age group (elderly or nonelderly), sex (male or female), and race/ethnicity (white, black, or Hispanic or Latino). Chi-square independence tests were calculated to examine bivariate associations between each violence exposure type and differences by age group, sex, and race/ethnicity.

In primary analyses, unadjusted and adjusted generalized linear models were used to assess hypervigilance scores (continuous scores on a 100-point scale) as an independent function of each violence exposure type (community violence, police violence, or police stops), controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, insurance type, and clinic location. Primary analyses were additionally stratified by age and sex. Including additional covariates such as annual household income, BMI, and spousal relationship status resulted in high levels of missing data. However, these covariates were included in the sensitivity analyses described below. In secondary analyses, we used identical model specifications to analyze BMI (continuous kg/m2) and BP (continuous mmHg) measurements as independent functions of hypervigilance score quartiles.

Of the 504 participants, 7.9 percent had missing data for hypervigilance, and an additional 4.2 percent had missing data for educational attainment (3.2 percent) or insurance type (1.0 percent) (see online appendix exhibit 1 for participant characteristics).23 Thus, in addition to complete case analyses with adjustment for the abovementioned participant characteristics, we also conducted sensitivity analyses that used multiple imputation for hypervigilance and educational attainment (model 1 in appendix exhibit 2) and for hypervigilance, educational attainment, annual household income, spousal relationship status, and BMI (model 2 in appendix exhibit 2).23

Data were analyzed using Stata/SE, version 13.1.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, it was a cross-sectional study. This limited our inferences about the direction of associations between study variables, as associations might have been bidirectional. For instance, people with preexisting hypervigilance may be more likely to report or become involved in violent encounters with community members or police, or vice versa. Future longitudinal studies are needed to establish temporal ordering among study variables.

Second, unmeasured confounders not assessed in this study might have contributed to the observed findings. However, based on our calculations of the E-value proposed by Tyler VanderWeele and Peng Ding,24 a very strong confounder would be necessary to explain away the observed associations in this study. Specifically, an unmeasured confounder would need to be associated with both the independent and dependent variables by a risk ratio of 11.3-fold each, above and beyond the measured confounders.

Third, measures for violence exposure and hypervigilance were self-reported. Some response bias might exist, particularly if participants did not wish to disclose any previous incidents with law enforcement officials. Attempts were made to mitigate this bias by administering surveys on tablets to increase anonymity.25 Alternatively, it is possible that participants who had higher exposure to neighborhood violence were more motivated to participate.

Fourth, the sample consisted of patients living in epicenters of violent crime, the majority of whom were female and older than age fifty and who identified themselves as African American. Study findings may have limited generalizability beyond this and similar populations living in urban, racially segregated, high-poverty neighborhood settings. However, this is a vulnerable population of special interest, as its members bear a disproportionate burden of cumulative exposure to violence—in particular, of caregiving for those affected by violence (for example, as black mothers of affected youth).

Finally, the Brief Trauma Questionnaire was selected for its alignment with DSM-V criteria and widespread clinical application. However, while it measures lifetime exposure to a large quantity of violent encounter types, it does not capture the chronicity or frequency of exposure.

Study Results

The survey cooperation rate, defined by the American Association for Public Opinion Research as the proportion of those who were interviewed out of all who were eligible and approached,26 was 61 percent. Of the 504 participants who completed the survey, 82.7 percent were recruited from an academic medical center on Chicago’s South Side, and the remaining 17.3 percent were recruited from a federally qualified health center on the West Side (exhibit 1). Most participants were female (71.0 percent); ages fifty and older (76.9 percent); and insured by Medicare, Medicaid, or both (57.5 percent). The majority identified themselves as non-Hispanic black (74.6 percent) or Hispanic or Latino (13.9 percent). More than half (58.9 percent) reported having been exposed to community violence, and over one-quarter (28.6 percent) had been exposed to police violence. Of those reporting exposure to a police stop (54.8 percent), nearly one in five (17.8 percent) met the criterion A definition for having been exposed to a traumatic event. In all, 63.5 percent of participants reported exposure to any type of neighborhood violence (data not shown).

Exhibit 1:

Characteristics of 504 study participants in Chicago, 2018

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Clinic | ||

| Academic medical center (South Side) | 417 | 82.7 |

| Federally qualified health center (West Side) | 87 | 17.3 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 18–34 | 5 | 1.0 |

| 35–49 | 112 | 22.2 |

| 50–64 | 200 | 39.7 |

| 65–79 | 160 | 31.8 |

| 80 and older | 27 | 5.4 |

| Female | 358 | 71.0 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 37 | 7.3 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 376 | 74.6 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 70 | 13.9 |

| Other | 21 | 4.2 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Less than high school graduate | 77 | 15.3 |

| High school graduate or GED equivalent | 101 | 20.0 |

| Some college or a 2-year degree | 156 | 31.0 |

| 4-year college degree or more | 129 | 25.6 |

| Don’t know or refused to answer | 41 | 8.1 |

| Insurance type | ||

| Private | 165 | 32.7 |

| Medicaid, with or without Medicare | 182 | 36.1 |

| Medicare | 108 | 21.4 |

| Other | 12 | 2.4 |

| None | 32 | 6.4 |

| Don’t know or refused to answer | 5 | 1.0 |

| Health measurements | ||

| Systolic blood pressure ≥140 or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg | 152 | 30.2 |

| Body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 | 227 | 45.0 |

| Exposure to neighborhood violence | ||

| Exposure to community violence (direct or indirect) | 297 | 58.9 |

| Exposure to police violence (direct or indirect) | 144 | 28.6 |

| Ever stopped by the police | 276 | 54.8 |

| Had traumatic police stopa | 49 | 17.8 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2018 from the Chicago Violence, Neighborhoods, and Health Study. NOTES GED is General Educational Development certification. Exposures to the various types of violence are explained in the text. Percentages may not sum to 100 percent due to rounding.

The item is adapted from Schnurr P, et al., Brief Trauma Questionnaire (note 20 in text), which assesses traumatic exposure according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, criterion A for a traumatic event: that it involved actual or threatened death or serious injury) (see note 20 in text).

In bivariate analyses, being male or black was associated with reporting higher exposure to police violence. For example, men reported significantly higher exposure to police violence or having had either a police stop for any reason or a traumatic police stop, compared to women (exhibit 2). However, men and women did not report significantly different exposure to community violence.

Exhibit 2. Percent of study participants in Chicago, Illinois, who reported having had voilence exposure, by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and type of voilence exposure, 2018.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2018 from the Chicago Violence, Neighborhoods, and Health Study. NOTES Exposures to the various types of violence are explained in the text. A traumatic police stop is explained in the notes to exhibit 1. For the race/ethnicity category, we conducted chi-square tests two ways: first with all three racial/ethnic groups in a single test, and then separately to confirm differences between particular groups. HL is Hispanic or Latino **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01 ****p < 0.001

Black participants reported significantly higher exposure to police violence than white or Hispanic or Latino participants did, while Hispanic or Latino participants reported less exposure to a police stop for any reason, compared to white or black participants. Overall, there were no significant differences in exposure to community or police violence by age group.

The mean hypervigilance score in our sample was 54.7 (standard deviation: 28.1; data not shown), which was 15.7 percentage points higher than the score correlated with a PTSD diagnosis in the Brief Hypervigilance Scale validation sample.22 While exposure to community violence was marginally but significantly associated with a 5.5-percentage-point increase in the adjusted hypervigilance score, compared to nonexposure (95% confidence interval: 0.2, 10.7), exposure to police violence was associated with a 9.8-percentage-point increase (95% CI: 4.1, 15.4) (exhibit 3). Indirect exposure to community violence was significantly associated with a higher hypervigilance score (an increase of 8.9 percentage points; 95% CI: 3.8, 14.0), while direct exposure only trended toward higher hypervigilance. Exposure to a previous police stop was not associated with a higher hypervigilance score. However, experiencing the police stop as a traumatic event (defined as meeting criterion A) was associated with a 20.0-percentage-point increase in the score (95% CI: 10.0, 27.2). In sensitivity analyses that used multiple imputation for missing values and additional covariates, the results did not differ substantively (see appendix exhibits 1 and 2).23 However, in the most stringent sensitivity model, only the findings pertaining to police violence remained significant.

Exhibit 3:

Association between type of neighborhood violence exposure and hypervigilance level of participants, 2018

| Hypervigilance level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood violence exposure | Mean score | Difference | Adjusted differencea |

| Community violence | |||

| All | |||

| Unexposed | 50.7 | Ref | Ref |

| Exposed | 57.0 | 6.3** | 5.5** |

| Direct exposure | |||

| Unexposed | 53.2 | Ref | Ref |

| Exposed | 56.9 | 3.7 | 4.1 |

| Indirect exposure | |||

| Unexposed | 49.4 | Ref | Ref |

| Exposed | 60.1 | 10.7**** | 8.9*** |

| Police violence | |||

| Unexposed | 51.2 | Ref | Ref |

| Exposed | 62.6 | 11.4**** | 9.8*** |

| Police stop | |||

| Any | |||

| Unexposed | 51.9 | Ref | Ref |

| Exposed | 56.5 | 4.6 | 4.2 |

| Traumaticb | |||

| Unexposed | 52.8 | Ref | Ref |

| Exposed | 73.1 | 20.4**** | 20.0**** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2018 from the Chicago Violence, Neighborhoods, and Health Study. NOTES Hypervigilance is measured on a 100-point scale. The exhibit shows data for the 446 participants with data for all of the variables in this analysis. Direct and indirect exposure are defined in the text.

Generalized linear models were used to estimate differences between exposed and unexposed groups, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, insurance type, and clinic location.

Includes the 261 participants who reported a prior police stop and whose stop was traumatic (defined in the notes to exhibit 1).

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

The mean hypervigilance score in the highest quartile was 88.2 (standard deviation: 7.2) compared with 16.5 (standard deviation: 11.4) in the lowest quartile (data not shown). Relative to the lowest quartile, a hypervigilance score in the highest quartile was associated with an 8.6 mmHg increase in adjusted BP (95% CI: 3.3, 13.9) (exhibit 4). In continuous models, a 20-percentage-point increase in the hypervigilance score was associated with a 2.0 mmHg increase in BP (95% CI: 0.8, 3.4) (data not shown). A higher hypervigilance score was not associated with higher BMI in adjusted models. In stratified analyses, the interaction effects were not significant by age or sex (appendix exhibit 3).23

Exhibit 4:

Associations between hypervigilance level and body mass index or systolic blood pressure of participants, 2018

| Hypervigilance level quartile | Body mass index (kg/m2, n = 364) | Systolic blood pressure (mmHg; n = 395) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Difference | Adjusted differencea | Mean | Difference | Adjusted differencea | |

| Low | 30.8 | Ref | Ref | 129.9 | Ref | Ref |

| Medium | 31.7 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 131.1 | 1.2 | 2.8 |

| High | 32.6 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 127.4 | −2.5 | 0.6 |

| Very high | 32.7 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 134.6 | 4.7 | 8.6*** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2018 from the Chicago Violence, Neighborhoods, and Health Study, for participants with complete data.

Generalized linear models were used to estimate differences between exposed and unexposed groups, adjusting for the variables listed in the notes to exhibit 3.

p < 0.01

Discussion

In this study of residents of Chicago who were predominantly members of racial/ethnic minority groups, we found that exposure to neighborhood violence (including police violence) was associated with higher hypervigilance. Exposure to community violence was associated with a 5.5-percentage-point increase in the hypervigilance score, while exposure to police violence was associated with a 9.8-percentage-point increase. In the most stringent sensitivity model, only associations with police violence remained consistently significant (appendix exhibit 2).23 Notably, hypervigilance scores were relatively high in this community sample, compared to the original Brief Hypervigilance Scale validation sample.22

In the context of increasing dialogue about police violence in inner-city neighborhoods,27 the study findings add to the extant literature and conversation in several ways. First, some policy makers have focused on efforts to curtail violent crimes between residents, but this study expands previous work by highlighting complex associations between police violence and the mental and physical health of community members—at least in this limited study sample.

Second, we identified a highly significant association between hypervigilance and a specific type of police violence: traumatic police stops. It is plausible to speculate that hypervigilance, among both residents and police officers, may be associated with harmful escalation during these highly charged, emotional encounters. For instance, the emotional Stroop task examines how emotional stimuli (for example, seeing threatening words such as attack) can affect attention and inhibition (for example, subsequently seeing the word blue displayed in green ink and correctly responding “blue”).3 In a meta-analysis of the emotional Stroop task in PTSD patients, hypervigilance suppressed cognitive functions that regulate attentional and emotional control.3 Hypervigilance, if present during and following traumatic police encounters, could thus contribute to the suppression of these cognitive tasks.

Equally plausible is the notion of cognitive priming—the process of associating police encounters with harmful or adverse situations—resulting from decades of historical tension between police and racialized populations. For instance, it is common for black parents to have “The Talk” (on how to behave and survive police interactions) with their children, especially their sons.28 This type of preventive priming, a component of racial socialization,29 is an unfortunate reality for many marginalized black communities. Although not assessed in this study, our overall findings might suggest an opportunity for supporting programs and activities (for example, police-youth baseball leagues) to improve the capacity of law enforcement officials and residents to interact in less stressful and more adaptive situations.

Our results also indicate that higher levels of hypervigilance were associated with higher BP, a finding that is consistent with the growing literature on social determinants of health. For instance, a prior study documented that patients living in areas in the highest quartile for violent crime had 25 percent higher odds of hypertension, even after individual- and neighborhood-level covariates were adjusted for.15 One possible explanation for this relationship is that hypervigilance plays a role in physiologic stress-response pathways that are responsible for the overstimulation of adrenal hormones and accumulation of allostatic load.13,16 Hypervigilance may also affect a person’s perceived or actual access to health care, a possibility that warrants further study.

In general, greater awareness and understanding of hypervigilance may help improve the effectiveness of clinical strategies. One such strategy is trauma-informed care, defined as health services “based on the knowledge and understanding of trauma and its far-reaching implications.”30 This model has been widely implemented in pediatric and mental health care spaces, with increasing efforts to implement the training more broadly.31 For instance, Kaiser-Permanente has launched a nationwide initiative to transform all primary care practices into trauma-informed practices.32 A growing understanding of trauma and its multidimensional aspects, including hypervigilance and race-related trauma,33 is critical for advancing not only health equity but also racial equity among populations exposed to violence.

In addition, our findings may prompt further research and inquiry into strategies to improve policing in communities with a high burden of trauma. Trauma-informed policing extends the principles of trauma-informed care to facilitate police interactions with residents that are consistent with the trauma recovery process and reduce the risk of retraumatization during police encounters. Efforts in trauma-informed juvenile justice have been extensive,34 and several police departments in the US have made recent advances toward trauma-informed policing.35 These trainings have not yet been studied in a longitudinal manner. However, the goal of trauma-informed training in law enforcement is to curtail the number of police stops that progress to traumatic encounters, allowing de-escalation to interrupt cycles of violence for both officers and residents.

Our study raises several important questions for future research. While research exists on the immediate cognitive and behavioral consequences of hypervigilance,4 there is little research on more long-term consequences (for example, cardiovascular disease), particularly among those with chronic exposure to adverse stimuli. Similarly, the bulk of the research on hypervigilance has been conducted among veterans. Very little research has been done in community-based samples, and there is a dearth of research among law enforcement samples. Enhancing our understanding of hypervigilance will be critical for elucidating the impacts of violence on the mental, social,36 and physical health of vulnerable populations.

Conclusion

Hypervigilance, which was highly prevalent in our sample, is an understudied response to neighborhood violence that may be associated with adverse health effects. Notably, exposure to police violence had consistent associations with hypervigilance in this predominantly racial/ethnic minority sample. Growing awareness and understanding of hypervigilance may help inform policing practices and health care responses to violence in high-risk urban communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

A earlier version of this article was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, Washington, D.C., May 8, 2019. The research was supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality K12 grant in patient-centered outcomes research (Grant No. 5K12HS023007; principal investigator, Elizabeth Tung) and by a pilot grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases’ Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (Grant No. NIDDK P30DK092949; principal investigator, Tung). Nichole Smith and Tung had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US government or the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Nichole A. Smith, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Dexter R. Voisin, Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Joyce P. Yang, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; and the National Center for PTSD, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Healthcare System, Palo Alto, CA

Elizabeth L. Tung, Section of General Internal Medicine and Center for Health and the Social Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Notes

- 1.Dalgleish T, Moradi AR, Taghavi MR, Neshat-Doost HT, Yule W. An experimental investigation of hypervigilance for threat in children and adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2001;31(3):541–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th ed. Arlington (VA): APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cisler JM, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Adams TG Jr, Babson KA, Badour CL, Willems JL. The emotional Stroop task and posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(5):817–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimble M, Boxwala M, Bean W, Maletsky K, Halper J, Spollen K, et al. The impact of hypervigilance: evidence for a forward feedback loop. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(2):241–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalev A, Liberzon I, Marmar C. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2459–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roszell DK, McFall ME, Malas KL. Frequency of symptoms and concurrent psychiatric disorder in Vietnam veterans with chronic PTSD. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1991;42(3):293–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voisin DR. The public health implications of violence exposures: violence and immunological factors among perinatally HIV-infected youth. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(1):3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macksoud MS, Aber JL. The war experiences and psychosocial development of children in Lebanon. Child Dev. 1996;67(1):70–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordberg A, Crawford MR, Praetorius RT, Hatcher SS. Exploring minority youths’ police encounters: a qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2016;33(2):137–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JR, Patton DU. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in context: examining trauma responses to violent exposures and homicide death among black males in urban neighborhoods. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2016;86(2):212–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tung EL, Johnson TA, O’Neal Y, Steenes AM, Caraballo G, Peek ME. Experiences of community violence among adults with chronic conditions: qualitative findings from Chicago. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(11):1913–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris MC, Hellman N, Abelson JL, Rao U. Cortisol, heart rate, and blood pressure as early markers of PTSD risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;49:79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu E, Lippert AM. Neighborhood crime rate, weight-related behaviors, and obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Sociol Compass. 2016;10(3):187–207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tung EL, Wroblewski KE, Boyd K, Makelarski JA, Peek ME, Lindau ST. Police-recorded crime and disparities in obesity and blood pressure status in Chicago. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(7):e008030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McEwen B, Lasley EN. Allostatic load: when protection gives way to damage. Adv Mind Body Med. 2003;19(1):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chicago Data Portal. Boundaries—community areas (current) [Internet]. Chicago (IL): City of Chicago; 2019. [cited 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://data.cityofchicago.org/Facilities-Geographic-Boundaries/Boundaries-Community-Areas-current-/cauq-8yn6 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. 2010 census data summarized to Chicago community areas [Internet]. Chicago (IL): CMAP; [last updated 2015 Jun 26; cited 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://datahub.cmap.illinois.gov/dataset/2010-census-data-summarized-to-chicago-community-areas [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12(12):1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnurr P, Vielhauer M, Weathers F, Finder M. Brief Trauma Questionnaire (BTQ) [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; 1999. [cited 2019 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/documents/BTQ.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson S Cognitive interview evaluation of survey questions on respondent involvement with the criminal justice system [Internet]. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; [cited 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/qbank/report/Willson_2018_NCHS_ASPE.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein RE, Delker BC, Knight JA, Freyd JJ. Hypervigilance in college students: associations with betrayal and dissociation and psychometric properties in a brief hypervigilance scale. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7(5):448–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 24.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowling A Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27(3):281–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys [Internet]. Oakbrook Terrace (IL): AAPOR; [last revised 2016; cited 2019 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crowell C, Mosley D, Falconer J, Faloughi R, Singh A, Stevens-Watkins D, et al. Black lives matter: a call to action for counseling psychology leaders. Couns Psychol. 2017;45(6):873–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gandbhir G, Foster B. A conversation with my black son. New York Times. 2015. March [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith-Bynum MA, Anderson RE, Davis BL, Franco MG, English D. Observed racial socialization and maternal positive emotions in African American mother-adolescent discussions about racial discrimination. Child Dev 2016;87(6):1926–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2014. [cited 2019 Aug 14]. Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green BL, Saunders PA, Power E, Dass-Brailsford P, Schelbert KB, Giller E, et al. Trauma-informed medical care: CME communication training for primary care providers. Fam Med. 2015;47(1):7–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Council for Behavioral Health [Internet]. Washington (DC): The Council; 2017. Press release, National Council for Behavioral Health launches new Trauma-Informed Primary Care Initiative; 2017 Oct 18 [cited 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/press-releases/national-council-behavioral-health-launches-new-trauma-informed-primary-care-initiative/ [Google Scholar]

- 33.Comas-Díaz L, Hall GN, Neville HA. Racial trauma: theory, research, and healing: introduction to the special issue. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Branson CE, Baetz CL, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood KE. Trauma-informed juvenile justice systems: a systematic review of definitions and core components. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(6):635–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vera Institute of Justice. Trauma-informed policing: interview with Captain Altovise Love-Craighead [Internet]. New York (NY): The Institute; [cited 2019 Aug 15]. Available from: https://www.vera.org/research/trauma-informed-policing [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tung EL, Hawkley LC, Cagney KA, Peek ME. Social isolation, loneliness, and violence exposure in urban adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(10):1670–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.