Abstract

Background

Approximately 30% of patients with epilepsy remain refractory to drug treatment and continue to experience seizures whilst taking one or more antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Several non‐pharmacological interventions that may be used in conjunction with or as an alternative to AEDs are available for refractory patients. In view of the fact that seizures in people with intellectual disabilities are often complex and refractory to pharmacological interventions, it is evident that good quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to assess the efficacy of alternatives or adjuncts to pharmacological interventions.

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review (Beavis 2007) published in The Cochrane Library (2007, Issue 4).

Objectives

To assess data derived from randomised controlled trials of non‐pharmacological interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

Non‐pharmacological interventions include, but are not limited to, the following.

• Surgical procedures.

• Specialised diets, for example, the ketogenic diet, or vitamin and folic acid supplementation.

• Psychological interventions for patients or for patients and carers/parents, for example, cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), electroencephalographic (EEG) biofeedback and educational intervention.

• Yoga.

• Acupuncture.

• Relaxation therapy (e.g. music therapy).

Search methods

For the latest update of this review, we searched the Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialised Register (19 August 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via CRSO (19 August 2014), MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 19 August 2014) and PsycINFO (EBSCOhost, 1887 to 19 August 2014).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of non‐pharmacological interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently applied the inclusion criteria and extracted study data.

Main results

One study is included in this review. When two surgical procedures were compared, results indicated that corpus callosotomy with anterior temporal lobectomy was more effective than anterior temporal lobectomy alone in improving quality of life and performance on IQ tests among people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. No evidence was found to support superior benefit in seizure control for either intervention. This is the only study of its kind and was rated as having an overall unclear risk of bias. The previous update (December 2010) identified one RCT in progress. The study authors have confirmed that they are aiming to publish by the end of 2015; therefore this study (Bjurulf 2008) has not been included in the current review.

Authors' conclusions

This review highlights the need for well‐designed randomised controlled trials conducted to assess the effects of non‐pharmacological interventions on seizure and behavioural outcomes in people with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy.

Plain language summary

Non‐pharmacological interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities

Epilepsy is a neurological condition characterised by involuntary activity of the brain, which manifests in seizures. The rate of epilepsy in people with intellectual diabilities is significantly higher than in the general population. Epilepsy in this population is often less responsive to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality. One relevant study comparing two surgical procedures has been included in this review. This study found that anterior corpus callosotomy (a procedure in which a section of the corpus callosum is severed) with anterior temporal lobectomy (a procedure in which part of the temporal lobe is removed) is more effective than anterior temporal lobectomy alone in improving quality of life and performance on IQ tests among people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. No support was found for a relative benefit of either procedure for improved seizure control. This review accentuates the lack of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating non‐pharmacological interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. Given the prevalence and nature of epilepsy in this population, well‐designed RCTs are needed to ascertain the effects of non‐pharmacological interventions on seizure and behavioural outcomes in people with intellectual disabilities. However, good quality evidence derived from RCTs including the non‐intellectually disabled should be assessed for side effects and efficacy before such studies are undertaken.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Anterior temporal lobectomy with anterior corpus callosotomy vs anterior temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy and intellectual disabilities | |||

|

Patient or population: people with temporal lobe epilepsy and intellectual disabilities Settings: China Intervention: anterior temporal lobectomy and anterior corpus callosotomy (aCCT) Comparison: anterior temporal lobe epilepsy (ATL) | |||

| Outcomes | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Although a higher percentage of people in the ATL and aCCT groups fell within Class I (seizure free) and Class II (> 50% reduction in seizures), no significant differences in seizure frequency were noted between the groups at 2 years after surgery People in the ATL and aCCT groups showed significant improvement on IQ tests compared with those in the ATL group 2 years following surgery People in the ATL and aCCT groups reported significantly improved quality of life 2 years after surgery. Those in the ATL group did not show significantly improved quality of life |

60 (1) |

Very low | We rated this study as of low quality because an insufficient randomisation method was reported and limited information was provided on study methodology in general. This study used different neuropsychological tests to assess IQ (WAIS in adults and WISC in children). Comparing scores across these tests is often problematic because of the potential disparity between the 2 scales, particularly for lower‐scoring individuals. Ethical approval was not mentioned. The quality of life questionnaire used in this study did not include a validated scale |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

Background

This review is an update of a review previously published in The Cochrane Library (2007, Issue 4).

Description of the condition

Epilepsy is the most common serious neurological disorder, with an overall incidence rate in developed countries of between 40 and 70 cases per 100,000 (Zarrelli 1999). Recent population data indicate that 1% of the general adult population in the United States is reported to have active epilepsy. The prevalence of epilepsy among people with intellectual disabilities is significantly higher than in the general population (Kobau 2013), with estimates ranging from 14% to 44%, increasing with severity of intellectual disability (Bowley 2000). In the general population, the prognosis for full seizure control is good, with approximately 70% of patients achieving long‐term remission, most within five years of diagnosis (Cockerell 1997). This means that approximately 30% of patients remain refractory to drug treatment and continue to experience seizures whilst taking one or more antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Management of epilepsy in people with intellectual disabilities poses additional challenges for clinicians, as the condition has been associated with significantly higher rates of morbidity and mortality (Morgan 2003). Several non‐pharmacological interventions available to refractory patients may be used in conjunction with or as an alternative to AEDs.

Description of the intervention

Surgical interventions

Surgical interventions have been an option for certain types of medically refractory epilepsy for more than 100 years; however, recent advances in neuroimaging and in surgical techniques have improved the surgical treatment of epilepsy to such an extent that some experts now suggest that physicians should offer surgery early to patients with surgically remediable epileptic syndromes (Engel 2003). Surgical treatment to abolish seizures has been particularly recommended for patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy and neocortical epilepsy. Three randomised controlled trials assessing the impact of epilepsy surgery have been identified. One compared partial versus complete hippocampectomy in temporal lobe epilepsy (Wyler 1995), another assessed the impact on language of resecting the superior temporal gyrus compared with performing standard left anterior temporal lobectomy (Hermann 1999) and still another compared surgical versus medical therapy for the treatment of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (Wiebe 2001). Studies carried out by Wiebe et al (Wiebe 2001) and by Wyler et al (Wyler 1995) excluded patients with an IQ lower than 70. Gleissner 1999 has reported favourable seizure outcomes following epilepsy surgery in people with an intellectual disability following careful patient selection.

Several surgical options are available for the treatment of individuals with epilepsy.

Resection: When surgeons are clear as to the origin of seizure activity, they can remove the portion of the damaged brain that appears to be causing epileptic seizures.

Corpus callosotomy: In the most severe cases of generalised seizures, the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres and allows for interhemispheric communication, may be severed to stop epileptic seizures.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS): This involves implanting a medical device sometimes referred to as a brain pacemaker, which sends electrical impulses to stimulate specific portions of the brain.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): This method uses a medical device that includes two coils to stimulate the vagus nerve, which causes the vagus nerve to send electrical impulses to the brain.

Dietary interventions

Another non‐pharmacological therapeutic option for patients with epilepsy consists of specialised diets or dietary supplementation. One example is the ketogenic diet ‐ a restrictive high‐fat, low‐protein and very low‐carbohydrate diet that has been used mainly in children, although recent research has demonstrated its effectiveness in an adult population (Schoeler 2014). One study indicates that ketogenic diets are effective, independent of age, seizure type and electroencephalogram (EEG) pattern (Freeman 1998). A recent Cochrane review (Levy 2012) identified four randomised controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of dietary interventions in children and six prospective studies that assessed various dietary interventions. Findings from this review suggest that the ketogenic diet may provide benefit for people with medically intractable epilepsy and for those for whom surgery is unsuitable, but it is poorly tolerated. This review also highlights the low‐carbohydrate Atkins diet as beneficial, but additional evidence of high quality is required to confirm this finding. Potential beneficial effects of the ketogenic diet have been highlighted by the Freeman 2009a study, in which investigators describe a reduction in parent‐reported seizures but no significant difference in EEG‐confirmed seizures. This cross‐over study included children younger than 12 years, making generalisation of results to adult populations problematic. Advantages of less restrictive Atkins‐like diets and low glycaemic diets have been suggested (Freeman 2009b). Dietary supplementation includes vitamins and folic acid, although currently no reliable high‐quality evidence can be found for these interventions (Ranganathan 2005).

Psychological interventions

Psychological interventions represent another non‐pharmacological treatment option for people with epilepsy. However, a recent Cochrane review (Ramaratnam 2008) evaluating the effects of psychological treatments for people with epilepsy revealed that the literature provides no reliable evidence to support these interventions, which include relaxation therapy, cognitive‐behavioural therapy, EEG biofeedback and educational interventions.

Yoga interventions

Yoga, an ancient Hindu practice, involves exercise that focuses on strength, flexibility and breathing to improve physical and mental well‐being. A Cochrane review (Panebianco 2015) found only two unblinded, controlled trials (Lundgren 2008; Panjwani 1996) and was unable to draw reliable conclusions about the efficacy of such treatment.

Acupuncture interventions

Acupuncture is based on complex theories involving regulation of blood and body fluid, yin and yang and the five elements (earth, fire, metal, water, wood). Two small randomised controlled trials have shown no beneficial effects of acupuncture for patients with intractable epilepsy with respect to seizure frequency (Kloster 1999) or quality of life (Stavem 2000). One study on the effects of acupuncture on spasticity in children with cerebral palsy reported no effects on frequency of seizures (Wu 2008). This study included children between one and six years of age.

How the intervention might work

Surgical interventions

Resection: This approach aims to reduce seizure frequency by removing the damaged portion of the brain responsible for epileptic seizures.

Corpus callosotomy: Cutting the corpus collosum prevents impulses causing the seizure from spreading across both hemispheres and is performed to stop severe generalised seizures.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS): Electrodes in the brain stimulate the portions of the brain involved in epileptic seizures to prevent irregular brain activity, thus preventing seizures.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): Regular impulses are sent to the brain when the vagus nerve is stimulated; however, the precise mechanism is unknown.

Dietary interventions

How the ketogenic diet may work remains unclear. Since the time of Hippocrates, fasting has been known to have a potentially beneficial effect on seizures (Hartman 2007). The ketogenic diet was designed to mimic the biochemical response to starvation when ketone bodies replace glucose as the primary fuel for the brain's energy demands (Hartman 2007).

Psychological interventions

Seizure occurrence may be influenced by behavioural, psychological and physiological states (Fenwick 1992). Therefore, reducing the psychological co‐morbidities often associated with epilepsy such as anxiety and depression has been shown to reduce seizure frequency (Miller 1994).

Yoga interventions

Stress is considered an important precipitating factor for seizures, stimulating interest in the use of yoga as treatment for stress. Yoga is believed to alleviate stress (Anand 1991) and therefore has been used in attempts to reduce seizure frequency.

Acupuncture interventions

Stimulation of specific body points can lead to correction of dysregulation of organ systems, relieving symptoms and restoring the body to its natural homeostasis (Maciocia 1989).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite the high prevalence of epilepsy among people with intellectual disabilities, interventional studies undertaken to explore epilepsy treatment are relatively rare. As seizures in people with intellectual disabilities are often complex and refractory to AEDs, good quality randomised controlled trials should be conducted to assess the efficacy of alternatives or adjuncts to AEDs for this population.

Objectives

To assess data derived from randomised controlled trials of non‐pharmacological interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

Non‐pharmacological interventions include, but are not limited to, the following.

Surgical procedures.

Specialised diets, for example, the ketogenic diet, or vitamin and folic acid supplementation.

Psychological interventions for patients or for patients and carers/parents, for example, cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), electroencephalographic (EEG) biofeedback and educational intervention.

Yoga.

Acupuncture.

Relaxation therapy (e.g. music therapy).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or cluster‐randomised trials using random allocation sequences (e.g. computer‐generated sequences) and reporting an adequate method of allocation concealment (e.g. sealed opaque envelopes, central randomisation by telephone, interactive voice response systems).

Quasi‐RCTs in which an inadequate method of allocation concealment is used (e.g. allocation by day of the week).

Trials of cross‐over or parallel design.

Blinded and unblinded trials.

Types of participants

Individuals (12 years of age and older) with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. We excluded studies that specifically recruited children younger than 12 years, as this review is focused on adolescent and adult populations, as well as studies exploring interventions for children with infantile spasms or West syndrome.

-

We considered participants to have an intellectual disability if they met any of the following criteria.

IQ indicating intellectual disability, clinical description suggesting intellectual disability or derivation from an environment likely to include an intellectually disabled population, for example, a special needs school or a day service for the learning disabled.

Individuals with a high percentage of intellectual disability, such as those with fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome or Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome. For maximal adherence to inclusion criteria, studies describing populations in which less than 50% of participants had an intellectual disability were excluded. Studies that included these populations but did not report the percentage of participants with intellectual disabilities were included, but conclusions drawn from these studies were treated more conservatively.

Participants could have any type of epilepsy, as classified by the investigator or by the International League Against Epilepsy (Commission on Classification, Commission 1981; Commission 1989), or as identified by other recognised classifications or clinical descriptions.

Types of interventions

Non‐pharmacological interventions included but were not limited to the following.

Surgical procedures.

Specific diets, for example, the ketogenic diet, or vitamin and folic acid supplementation.

Psychological interventions for patients or for patients and carers/parents, for example, cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), electroencephalographic (EEG) biofeedback and educational intervention.

Yoga.

Acupuncture.

Relaxation therapy (e.g. music therapy).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Retention on treatment (days, weeks or months).

Freedom from seizures.

-

Reduction in seizure frequency from pre‐randomisation baseline period to treatment period.

Overall reduction (median/mean).

Responder rate reduction (≥ 50% reduction in seizure frequency).

Score on seizure severity scales.

Secondary outcomes

Behavioural outcomes

Changes from baseline in validated behavioural measures.

Cognitive outcomes

Changes from baseline in validated cognitive measures.

Adverse effects

Any reported adverse effects.

Adverse effects requiring treatment withdrawal.

Quality of life

Changes from baseline on validated quality of life scale.

Global rating scale

Often a non‐validated clinician‐generated view of overall outcome without focus on a specific change. These outcomes are usually reported as 'better', 'the same' or 'worse'.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The search was run for the original review in 2007, and subsequent searches were run in November 2009, December 2010, September 2012 and August 2014. For the latest update, we searched the following electronic databases while applying no language restrictions.

Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialised Register (19 August 2014), using the strategy outlined in Appendix 1.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO; 19 August 2014), using the strategy outlined in Appendix 2 (CENTRAL includes the specialised registers of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group and the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group).

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 19 August 2014), using the strategy outlined in Appendix 3.

PsycINFO (EBSCOhost, 1887 to 19 August 2014), using the strategy outlined in Appendix 4.

The National Research Register Archive was searched previously (1 December 2009) with 'epilepsy' used as a keyword and 'trial' in the methodology field, but this source no longer needs to be searched because it is a closed archive to which no new items will be added.

Search terms used for the first version of this review (The Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 4) are provided in Appendix 5.

Searching other resources

We handsearched journals for which we found hits in our electronic searches (if these journals had not already been handsearched by members of The Cochrane Collaboration). We also contacted other researchers in the field in an attempt to locate unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this update, two review authors (CFJ, SMM) independently assessed all studies identified by the search strategies for inclusion in the review. After performing an initial screen of identified studies, we excluded articles whose titles, abstracts or both were clearly irrelevant. We then retrieved the full text of the remaining articles (and translated these into English when required). The same two independent review authors assessed all full‐text studies and identified eligible studies in keeping with the inclusion criteria of this review. We resolved disagreements through discussion.

Data extraction and management

The same two review authors independently extracted data from included studies using pre‐standardised data extraction forms. Data extracted were cross‐checked, and discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

We extracted the following information from included studies.

Methods

Duration of study.

Type of intervention used.

Confounding variables for which controls were applied.

Sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Method of blinding.

Other risk of bias concerns.

Participants

Total sample size.

Total number of participants allocated to each group.

Setting.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Age.

Race.

Gender.

Country.

Other medical or psychological/psychiatric diagnoses.

Co‐medication.

Outcomes

Name and definition of outcome.

Units of measurement.

Results

Study attrition.

Sample size for each outcome.

Missing data.

Summary data for intervention and control groups (e.g. means and standard deviations for all outcomes); see Types of outcome measures.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CFJ, SMM) intended to independently assess risk of bias within each included study by using the 'Risk of bias' tool as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), by which risk of bias is rated as high, low or unclear. From this rating, an overall summary judgement of risk of bias was made for each study per outcome and per outcome across studies. We created 'Summary of findings' tables using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (Guyatt 2008). We cross‐checked risk of bias assessments and discussed and resolved inconsistencies.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes such as seizure freedom, seizure reduction (responder rates) and adverse effects, we planned to present risk ratios using 95% confidence intervals.

For continuous outcomes such as seizure reduction (overall reduction), seizure severity and scores on behavioural scales, cognitive scales and quality of life scales, we planned to present effect estimates as mean differences or standardised mean differences (SMDs) in the event of variation across outcome measures.

Unit of analysis issues

In the event that unit of analysis issues were present across included studies (e.g. cross‐over studies, cluster‐randomised studies, repeated measures), we planned to do the following.

Determine whether methods in such studies were conducted appropriately.

Combine extracted effect sizes from such studies through a generic inverse variance meta‐analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors in the event of missing data to learn the reasons for this and to conclude whether data were missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

As this review was undertaken to evaluate various AEDs, we expected to see differences in control groups, measures, interventions and time scales, which may not necessarily relate to one another. In this instance, we would not combine data in a meta‐analysis.

Two review authors (CFJ, SMM) planned to assess visually the clinical and methodological heterogeneity of included studies, and planned to carry out I2 statistic and Chi2 tests when applicable to assess statistical heterogeneity. We judged a Chi2 P value less than 0.1 and I2 greater than 50% to indicate statistical heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to request protocols from study authors and to investigate outcome reporting bias using the Outcome Reporting Bias in Trials (ORBIT) matrix system (Kirkham 2010).

To examine publication bias, we searched for unpublished data by carrying out a comprehensive search of multiple sources and requesting unpublished data from study authors. We planned to look for small study effects to establish the likelihood of publication bias.

Data synthesis

We expected to carry out a random‐effects meta‐analysis to synthesise study data. This approach was planned because of the various interventions being evaluated and the differing outcomes they might yield. We planned to analyse different interventions and different control groups separately.

However, a meta‐analysis was inappropriate, as only one relevant study was identified and included in the present review. Therefore, we used a narrative approach in discussing results and overall outcomes of this study.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to stratify subgroup analyses by type and duration of intervention. If statistical heterogeneity across studies was observed, we planned to investigate study and participant characteristics to identify areas of heterogeneity and to carry out a random‐effects meta‐analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

In the event that any peculiarities were identified, we planned to carry out a sensitivity analysis. This analysis would have included only studies that were rated as having low risk of bias. Results of the sensitivity analysis would then have been compared with findings of the overall meta‐analysis to identify inconsistencies.

Results

Description of studies

The updated search in December 2010 revealed three studies of potential relevance. One is an ongoing RCT closed to recruitment with results pending (Bjurulf 2008). The remaining two studies did not satisfy the inclusion criteria, as they included only children between one and ten years of age and between one and six years of age, respectively (Freeman 2009a; Wu 2008).

An updated search in September 2012 found no reports of studies that were relevant to this review. This update identified one study awaiting classification (Liang 2010).

Results of the search

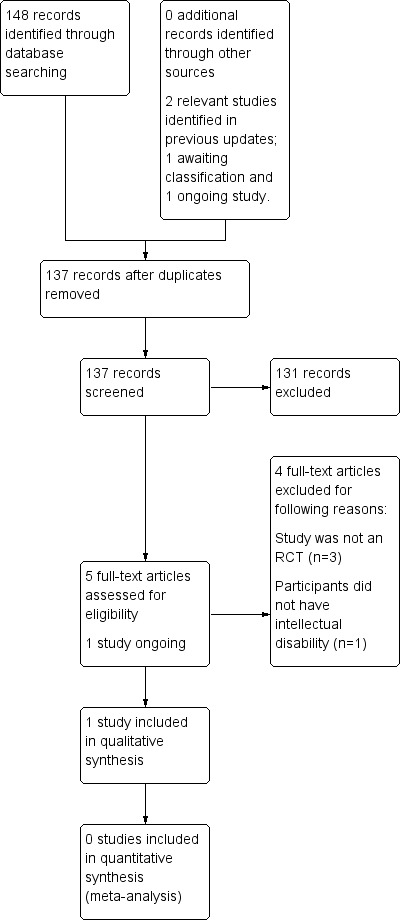

We carried out updated searches from the date of the previous search (September 2012) to 19 August 2014. The search strategies are outlined in Electronic searches. This search revealed 148 studies. After 13 duplicates were removed, 135 studies remained. These studies were screened, and a further 130 studies were excluded because of irrelevance. Five papers remained for full‐text review but were excluded at this stage. A previously identified study (Liang 2010) that was awaiting classification in the last review was included in this update. Therefore, one study was included in this review. Bjurulf 2008 was identified as a relevant ongoing study. We contacted the study authors (27/07/15) and were informed that there has been no published data at that time. Further details of this study can be found in Characteristics of ongoing studies. See Figure 1 for results of the updated search; see also Characteristics of excluded studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Liang 2010

In an RCT conducted by Liang in 2010, 60 people with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and intellectual disability (ID) were recruited and were randomly assigned to one of two surgery intervention groups. To screen participants, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroencephalogram (EEG) and positron emission tomography (PET) assessments were performed. In the control group, participants underwent anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL group), and in the experimental group, participants underwent anterior temporal lobe lobectomy and anterior corpus callosotomy (ATL and aCCT group). Resective regions in the anterior temporal lobectomy procedure included 4 to 5 cm on the left side and 5 to 6 cm on the right side of both the superior temporal gyrus and the interior temporal gyrus. At least 2 to 3.5 cm of the hippocampus was removed. When anterior temporal lobectomy was combined with anterior corpus callosotomy, a unique incision was needed on both the fronto‐temporal flap and the bone flap. Anterior corpus callosotomy was performed after anterior temporal lobectomy had been completed. Following full exposure of the posterior part of the corpus callosum, the anterior extent of resection was defined by the dorsal surface of the anterior cerebral arteries. The corpus callosum was disconnected until the ependyma was visible. The callosotomy was performed under microscope. The length of the corpus callosotomy was 6 to 7 cm, thus representing approximately two‐thirds of the corpus callosum. Preoperative assessments included performance IQ, verbal IQ and full‐scale IQ measures from the Wechsler Child Intelligence Scale (WCIS; Chinese version) or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS; Chinese version), ; responses on an eight‐item quality of life (QOL) questionnaire that had been developed by the study authors and seizure frequency were recorded for the three months before surgery was performed. Two years after surgery, participants again completed the WAIS and the QOL questionnaire During this time, participants monitored their seizure frequency.

Excluded studies

Previously, review authors excluded 35 studies; 31 studies did not appear to include people with intellectual disabilities (Amar 1998; Ben‐Menachem 1994; Clarke 1997A; Dahl 1985; Dahl 1987; Deepak 1994; DeGiorgio 1997; DeGiorgio 2005; Dodrill 2001; Elger 2000; Engelberts 2002; Gates 2005; Handforth 1998; Helgeson 1990; Helmstaedter 2011; Hermann 1993; Holder 1992; Inuzuka 2005; Kockelmann 2005; Landy 1993; Lutz 2004; Panjwani 1987; Puskarich 1992; Ramsay 1994; Scherrmann 2001; Sidorenko 2000; Tan 1986; VNS Study Group 1995; Warner 1997; Wyler 1995; Yuen 2005), three studies included only children younger than age 12 (Bergqvist 2005; Freeman 2009a; Wu 2008) and one study was not an RCT (Dave 1993).

In the present update, we excluded one study as participants did not have intellectual disabilities (Koubeisse 2013) and three studies because they were not RCTs (Cross 2012; Lemmon 2012; Liu 2012).

Risk of bias in included studies

Liang 2010 randomly assigned 60 participants by allocating them numbers according to when they were recruited to the study, then dividing them into two groups according to odd/even numbers. However, information was insufficient to show whether these numbers were random or consecutive; it is unclear whether this would introduce bias. Limited information is available about whether allocation was concealed, and no information indicates whether participants, study personnel and outcome assessors were blinded. However, it is unlikely that adequate allocation concealment or participant and study personnel blinding was possible. No drop‐outs were reported, and information regarding funding of this trial was unavailable. We contacted the study author but received no response. Therefore this study has been rated as having unclear overall risk of bias.

Additional information regarding the risk of bias assessment is shown in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The included study reported significant improvement in perceptual IQ outcomes in ATL and aCCT groups but no change in the ATL only group two years after surgery. Additionally, participants in the ATL and aCCT groups reported significantly better quality of life two years after surgery than was reported by those in the ATL only group. Investigators explained that no permanent complications were experienced by any participants. However, temporary complications were reported by nine participants. In the ATL and aCCT groups, two participants reported urinary incontinence, one reported aphasia and two reported apraxia following surgery. In the ATL group, two participants reported aphasia and two reported apraxia, but the duration of temporary complications was unclear. Study authors concluded that ATL and aCCT can improve QOL and the performance intelligence quotient (PIQ) of individuals with TLE and ID with no permanent adverse effects; therefore ATL combined with aCCT can be considered a viable option for patients with TLE and ID. No significant differences in seizure frequency before and after surgery were reported between groups. Further details of this study can be found in Table 1.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Updated searches revealed no new eligible studies for inclusion in this review. However, one study, which was awaiting classification in the last review, has now been included. Therefore, the present review update includes only one study. In this study, researchers found that anterior temporal lobectomy with anterior corpus callosotomy is more effective than anterior temporal lobectomy alone in terms of improving quality of life, although this outcome was measured by a non‐validated scale with only one endpoint.

The previously identified ongoing study (Bjurulf 2008) has produced no published articles to date. We contacted study authors (27/07/15) and learned that one paper has been submitted and should be published by the end of 2015. Therefore, this study remains in the 'Ongoing studies' section.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

In terms of evaluating non‐pharmacological interventions for epilepsy in people with intellectual disabilities, the present review included only one study that assessed surgical interventions. We included in this review no studies assessing dietary, psychological, yoga or acupuncture interventions. Therefore, the overall completeness and applicability of evidence provided are poor. The key finding of the present review is the shortage of high‐quality RCTs undertaken to assess non‐pharmacological interventions that can be used as alternatives or adjuncts to AEDs for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

Quality of the evidence

As only one study analysed results from 60 participants, it is difficult for the review authors to draw robust conclusions. Additionally, the identified study had several limitations, and the overall risk of bias was assessed as unclear. Given the lack of high‐quality evidence, we can make no conclusions regarding use of ATL, aCCT or non‐pharmacological inventions in general.

Potential biases in the review process

None known.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The present review includes only one RCT, which found that anterior temporal lobectomy with anterior corpus callosotomy may be more effective than anterior temporal lobectomy alone for improving quality of life and performance on IQ tests among people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. Liang 2014 was a prospective study, which found anterior corpus callosotomy to be more effective than AEDs in terms of seizure control, improved quality of life and enhanced performance on IQ tests. In a retrospective study (Jalilian 2010) comparing anterior versus complete corpus callosotomy among children and adolescents, study authors concluded that a complete corpus callosotomy should be considered for lower‐functioning children, and that higher‐functioning children without clinically significant disconnection syndrome may benefit from a complete corpus callosotomy. Despite supporting evidence, few RCTs have assessed the efficacy and potential risks involved with such surgical procedures because of ethical issues surrounding this type of research (Wiebe 2001).

The present review included no RCTs assessing the effectiveness of dietary interventions. However, a Cochrane review (Levy 2012) reported that dietary interventions, particularly the ketogenic diet, can have a beneficial effect for seizure control among people with epilepsy. Adverse effects including gastrointestinal (short‐term) and cardiovascular (long‐term) complications were reported. Additionally, such dietary interventions are poorly tolerated and therefore are poorly maintained by patients (Hemingway 2001). This suggests that dietary interventions may offer a feasible alternative to AEDs for the treatment of individuals with drug‐refractory epilepsy.

A paucity of literature has been found on studies assessing the efficacy of yoga as an intervention within the wider field of epilepsy, with one Cochrane review (Panebianco 2015) identifying just two studies. Despite suggestions that yoga may have a beneficial effect for people with epilepsy, we have drawn no firm conclusions , given the quantity and the quality of this evidence. Limited evidence is available on the use of psychological interventions for seizure control and psychological well‐being among people with epilepsy (Ramaratnam 2008), as well as on non‐pharmacological interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

In the light of the limited number of RCTs performed to assess non‐pharmacological interventions, authors of future updates of this review may wish to consider inclusion of non‐RCTs, with the goal of identifying a potentially wider evidence base.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

As only one study is included in the present review, implications for practice are limited. Despite the findings of Liang 2010 suggesting that anterior temporal lobectomy with anterior corpus callosotomy may be more effective than anterior temporal lobectomy alone in improving quality of life and enhancing performance on IQ tests among people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities, this is the only study of its kind. Therefore the reliability of these findings is questionable. Furthermore, we found no studies undertaken to assess psychological, dietary, yoga or acupuncture interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. Therefore, we obtained no robust evidence from randomised controlled trials designed to assess non‐pharmacological interventions available to clinicians treating people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

Implications for research.

The prevalence of epilepsy among people with intellectual disabilities is significantly higher than in the general population (Kobau 2013). Furthermore, people with intellectual disabilities often have drug‐resistant epilepsy, for which AEDs are insufficient. Despite this, very little quality evidence is available from studies assessing the efficacy and side effects of various alternatives to drug therapy for people with intellectual disabilities. Absence of good quality evidence for non‐pharmacological interventions appears to involve not only people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities but also those with epilepsy within the wider population. Given that the rate of refractory epilepsy is thought to be around 30% among people with epilepsy, and even higher among those with intellectual disabilities, good quality research is needed to explore alternatives to drug therapy for people with epilepsy, particularly for those with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 August 2014 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated on 19 August 2014 |

| 19 August 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Before the present update was prepared, this review included no studies. Authors of the present review found one study, which has been included in this review update. Despite this fact, given the paucity of evidence in this area, no robust conclusions can be drawn within this review |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2005 Review first published: Issue 4, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 October 2012 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated in September 2012: No new studies were identified |

| 16 December 2010 | New search has been performed | We updated the searches in December 2010 and identified one new study for possible inclusion; however the trial is ongoing. We will decide whether to include this study in a subsequent update of this review |

| 20 August 2008 | Amended | We converted this review to the new review format |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Janine Beavis and Ivana Dojcinov for contributions to previous versions of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Epilepsy Group Specialised Register search strategy

#1 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Learning Disorders Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RH SU TH US UR VI

#2 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Intellectual Disability Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#3 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Mentally Disabled Persons Explode All WITH CL HI LJ PX RH SN

#4 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Mental Disorders Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO CN DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#5 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Developmental Disabilities Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RH SU TH US UR VI

#6 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Fragile X Syndrome Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#7 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Rett Syndrome Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#8 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Down Syndrome Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#9 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Autistic Disorder Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RH SU TH US UR VI

#10 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Angelman Syndrome Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#11 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Cerebral Palsy Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO CN DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#12 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Tuberous Sclerosis Explode All WITH BL CF CI CL CO CN DI DH DT EC EM EN EP EH ET GE HI IM ME MI MO NU PS PA PP PC PX RA RI RT RH SU TH US UR VE VI

#13 learning NEXT (disab* or difficult* or problem* or disorder* or handicap*)

#14 mental* NEXT (retard* or disab* or deficien* or handicap* or incapacity or disorder*)

#15 intellect* NEXT (disab* or impair* or handicap*)

#16 cognitive NEXT impairment

#17 development* NEXT disab*

#18 multipl* NEXT handicap*

#19 Down* NEAR2 syndrome

#20 "Fragile X" NEXT syndrome

#21 Rett* NEAR2 syndrome

#22 Lennox NEXT Gastaut NEXT syndrome

#23 tuberous NEXT sclerosis

#24 autism OR autistic

#25 Angelman* NEAR2 syndrome

#26 West* NEAR2 syndrome

#27 cerebral NEXT palsy

#28 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27

#29 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Anticonvulsants Explode All WITH AD AE AG AN AI BL CF CS CH CL CT DU EC HI IM IP ME PK PD PO RE ST SD TU TO UR

#30 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Epilepsy Explode All WITH DT

#31 #29 OR #30

#32 #28 NOT #31

#33 >2010:YR

#34 #32 AND #33

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Learning Disorders EXPLODE ALL TREES

#2 MESH DESCRIPTOR Intellectual Disability EXPLODE ALL TREES

#3 MESH DESCRIPTOR Mentally Disabled Persons EXPLODE ALL TREES

#4 MESH DESCRIPTOR Mental Disorders EXPLODE ALL TREES

#5 MESH DESCRIPTOR Developmental Disabilities EXPLODE ALL TREES

#6 MESH DESCRIPTOR Fragile X Syndrome EXPLODE ALL TREES

#7 MESH DESCRIPTOR Rett Syndrome EXPLODE ALL TREES

#8 MESH DESCRIPTOR Down Syndrome EXPLODE ALL TREES

#9 MESH DESCRIPTOR Autistic Disorder EXPLODE ALL TREES

#10 MESH DESCRIPTOR Angelman Syndrome EXPLODE ALL TREES

#11 MESH DESCRIPTOR Cerebral Palsy EXPLODE ALL TREES

#12 MESH DESCRIPTOR Tuberous Sclerosis EXPLODE ALL TREES

#13 learning NEXT (disab* or difficult* or problem* or disorder* or handicap*)

#14 mental* NEXT (retard* or disab* or deficien* or handicap* or incapacity or disorder*)

#15 intellect* NEXT (disab* or impair* or handicap*)

#16 cognitive NEXT impairment

#17 development* NEXT disab*

#18 multipl* NEXT handicap*

#19 Down* NEAR2 syndrome

#20 "Fragile X" NEXT syndrome

#21 Rett* NEAR2 syndrome

#22 Lennox NEXT Gastaut NEXT syndrome

#23 tuberous NEXT sclerosis

#24 autism OR autistic

#25 Angelman* NEAR2 syndrome

#26 West* NEAR2 syndrome

#27 cerebral NEXT palsy

#28 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27

#29 (epilep* OR seizure* OR convuls*):TI,AB,KY

#30 MESH DESCRIPTOR Epilepsy EXPLODE ALL TREES

#31 MESH DESCRIPTOR Seizures EXPLODE ALL TREES

#32 #29 OR #30 OR #31

#33 #28 AND #32

#34 MESH DESCRIPTOR Anticonvulsants EXPLODE ALL TREES

#35 MESH DESCRIPTOR Epilepsy EXPLODE ALL TREES WITH QUALIFIERS DT

#36 #34 OR #35

#37 #33 NOT #36

#38 * NOT INMEDLINE AND 12/09/2012 TO 21/07/2014:DL

#39 #37 AND #38

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

This strategy is based on the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials published in Lefebvre 2009.

1. exp Learning Disorders/

2. exp Intellectual Disability/

3. exp Mentally Disabled Persons/

4. exp Mental Disorders/

5. exp Developmental Disabilities/

6. exp Fragile X Syndrome/

7. exp Rett Syndrome/

8. exp Down Syndrome/

9. exp Autistic Disorder/

10. exp Angelman Syndrome/

11. exp Cerebral Palsy/

12. exp Tuberous Sclerosis/

13. (learning adj1 (disab$ or difficult$ or problem$ or disorder$ or handicap$)).tw.

14. (mental$ adj1 (retard$ or disab$ or deficien$ or handicap$ or incapacity or disorder$)).tw.

15. (intellect$ adj1 (disab$ or impair$ or handicap$)).tw.

16. cognitive impairment.tw.

17. (development$ adj1 disab$).tw.

18. (multipl$ adj1 handicap$).tw.

19. fragile x syndrome.tw.

20. Rett$ syndrome.tw.

21. Lennox Gastaut syndrome.tw.

22. Down$ syndrome.tw.

23. tuberous sclerosis.tw.

24. (autism or autistic).tw.

25. Angelman$ syndrome.tw.

26. West$ syndrome.tw.

27. cerebral palsy.tw.

28. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27

29. exp Epilepsy/

30. exp Seizures/

31. (epilep$ or seizure$ or convuls$).tw.

32. 29 or 30 or 31

33. exp *Pre‐Eclampsia/ or exp *Eclampsia/

34. 32 not 33

35. (randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or (randomized or placebo or randomly).ab.

36. clinical trials as topic.sh.

37. trial.ti.

38. 35 or 36 or 37

39. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

40. 38 not 39

41. 28 and 34 and 40

42. exp *Anticonvulsants/

43. exp *Epilepsy/dt [Drug Therapy]

44. 42 or 43

45. 41 not 44

46. limit 45 to ed=20120901‐20140819

Appendix 4. PsycINFO search strategy

| S20 | S15 NOT S18 Published 20110901‐ |

| S19 | S15 NOT S18 |

| S18 | S16 OR S17 |

| S17 | TI antiepilep* or anti‐epilep* or anticonvuls* or anti‐convuls* or AED or AEDs or Acetazolamide or Alodorm or Antilepsin or Arem or Ativan or Barbexaclone or Beclamide or Brivaracetam or Carbagen or Carbamazepine or Celontin or Cerebyx or Chlonazepam or Chloracon or Cloazepam or Clobazam or Clonazepamum or Clonex or Clonopin or Clorazepate or Convulex or Depacon or Depak* or Depamide or Desitin or Diacomit or Diamox or Diastat or Diazepam or Dilantin or Diphenin* or Diphenylhydantoin or Divalpr* or Dormicum or Ecovia or Emeside or Epanutin or Epiject or Epilim or Episenta or Epival or Eptoin or Ergenyl or Erimin or Eslicarbazepine or Ethadione or Ethosuximide or Ethotoin or Ethylphenacemide or Exalief or Excegran or Ezogabine or Fanatrex or Felbamate or Felbatol or Fosphenytoin or Frisium or Fycompa or Gabapentin or Gabarone or Gabitril or Gabrene or Ganaxolone or Garene or Gralise or Halogabide or Halogenide or Hibicon or Hypnovel or Iktorivil or Inovelon or Insoma or Intensl or Keppra or Klonopin or Kriadex or Lacosamide or Lamict* or Lamitor or Lamitrin or Lamogine or Lamotrigine or Lamotrine or Landsen or Levetiracetam or Liskantin or Loraz or Lorazepam or Losigamone or Luminal or Lyrica or Mebaral or Mephenytoin or Mephobarbit* or Mephyltaletten or Mesantoin or Mesuximide or Methazolamide or Methsuximide or Methylphenobarbit* or Midazolam or Mogadon or Mylepsinum or Mysoline or Neogab or Neptazane or Neurontin or Nimetazepam or Nitrados or Nitrazadon or Nitrazepam or Normison or Novo‐Clopate or Nupentin or Nydrane or Onfi or Orfiril or Orlept or Ormodon or Ospolot or Oxcarbazepine or Pacisyn or Paraldehyde or Paramethadione or Paxadorm or Paxam or Peganone or Perampanel or Petinutin or Petril or Phemiton or Phenacemide or Pheneturide or Phenobarbit* or Phensuximide or Phenytek or Phenytoin or Posedrine or Potiga or Pregabalin or Primidone or Prodilantin or Progabide or Prominal or Prysoline or Ravotril or Remacemide or Remnos or Resimatil or Restoril or Retigabine or Riv?tril or Rufinamide or Sabril or Seclar or Selenica or Seletracetam or Sertan or Somnite or Stavzor or Stedesa or Stiripentol or Sulthiam* or Sultiam* or Talampanel or Tegretol or Temazepam or Temesta or Teril or Tiagabine or Timonil or Topamax or Topiramate or Tranxene or Tridione or Trileptal or Trimethadione or Trobalt or Urbanol or Valance or Valcote or Valium or Valnoctamide or Valparin or Valpro* or Versed or Vigabatrin or Vimpat or Zalkote or Zarontin or Zebinix or Zonegran or Zonisamide |

| S16 | MM "Anticonvulsive Drugs" OR MM "Carbamazepine" OR MM "Chloral Hydrate" OR MM "Clonazepam" OR MM "Diphenylhydantoin" OR MM "Nitrazepam" OR MM "Oxazepam" OR MM "Pentobarbital" OR MM "Phenobarbital" OR MM "Pregabalin" OR MM "Primidone" OR MM "Valproic Acid" |

| S15 | S10 AND S13 AND S14 |

| S14 | TI ( (randomiz* OR randomis* OR controlled OR placebo OR blind* OR unblind* OR "parallel group" OR crossover OR "cross over" OR cluster OR "head to head") N2 (trial OR method OR procedure OR study) ) OR AB ( (randomiz* OR randomis* OR controlled OR placebo OR blind* OR unblind* OR "parallel group" OR crossover OR "cross over" OR cluster OR "head to head") N2 (trial OR method OR procedure OR study) ) |

| S13 | S11 OR S12 |

| S12 | epilep* OR seizure* OR convuls* |

| S11 | MM "Epilepsy" OR MM "Epileptic Seizures" OR MM "Experimental Epilepsy" OR MM "Grand Mal Seizures" OR MM "Petit Mal Seizures" OR MM "Status Epilepticus" |

| S10 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 |

| S9 | Rett* syndrome or Lennox Gastaut syndrome or Down* syndrome or Angelman* syndrome or West* syndrome |

| S8 | autistic or autism or cerebral palsy or fragile X syndrome |

| S7 | development* disab* or multipl* handicap* or cognitive impairment or tuberous sclerosis |

| S6 | intellect* disab* or intellect* impair* or intellect* handicap* |

| S5 | mental* disab* or mental* retard* or mental* deficien* or mental* handicap* or mental* incapacity or mental* disorder* |

| S4 | learning disab* or learning difficult* or learning problem* or learning disorder* or learning handicap* |

| S3 | DE "autism" or "cerebral palsy" or "downs syndrome" |

| S2 | DE "learning disabilities" or "learning disorders" or "mental disorders" or "rett syndrome" |

| S1 | DE "cognitive impairment" or "mental retardation" or "developmental disabilities" or "fragile x syndrome" |

Appendix 5. Original search terms

The following search terms were used (as free text and as index terms, as appropriate for each database) during searches for the first version of this review (The Cochrane Library 2007, Issue 4). The same search terms were used for the update.

‐ learning difficulties ‐ learning disabilities ‐ learning problems ‐ mental retardation ‐ mentally disabled ‐ mental handicap ‐ mental deficiency ‐ mental incapacity ‐ mental illness ‐ mental disorders ‐ intellectual disability ‐ intellectual impairment ‐ intellectual handicap ‐ cognitive impairment ‐ developmental disabilities ‐ subnormal ‐ fragile X syndrome ‐ Rett syndrome ‐ Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome ‐ Down's syndrome ‐ tuberous sclerosis ‐ autism ‐ West syndrome ‐ Angelman's syndrome ‐ cerebral palsy ‐ multiple handicap ‐ epilepsy ‐ seizures ‐ convulsion ‐ anticonvulsant ‐ antiepileptic ‐ vagal ‐ vagus nerve ‐ vagus stimulation ‐ ketogen ‐ diet ‐ diet supplements ‐ dietary supplements ‐ mega‐vitamins ‐ ginkgo ‐ St John's wort ‐ ketones ‐ diet restriction ‐ fasting ‐ surgery ‐ surgical interventions ‐ surgical procedure ‐ surgical techniques ‐ surgical treatment ‐ hippocampectomy ‐ superior temporal gyrus ‐ psychological ‐ psychotherapy ‐ biofeedback ‐ hypnotherapy ‐ relaxation ‐ behavioural therapy ‐ cognitive therapy ‐ aromatherapy ‐ massage ‐ music ‐ yoga ‐ meditation

To identify randomised controlled trials, we combined these search terms with phases 1 and 2 of the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for MEDLINE, as set out in Appendix 5b of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Again, we modified this strategy as appropriate for different databases.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Liang 2010.

| Methods | Quasi‐randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 60 people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities | |

| Interventions | Anterior temporal lobectomy vs anterior temporal lobectomy with anterior corpus callosotomy | |

| Outcomes | Assessment of seizure frequency, full‐scale IQ test (WAIS/WISC; Chinese version) and QOL questionnaire | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | All participants were given a number from 1 to 60 and were separated into 2 groups according to odd/even numbers. It is unclear whether numbers were allocated randomly or consecutively |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether numbers were randomly or sequentially allocated and whether allocation concealment was possible. No information in the published article indicates whether allocation concealment was attempted or was adequate |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details were given about whether participants and personnel were blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details were given about whether outcome assessors were blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No details were given about whether participants withdrew from the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Protocol is unavailable |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Different tests were used for participants of different ages. No information about funding of the study was provided |

WAIS: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

WISC: Wechler Intelligence Scale for Children.

QOL: Quality of life.

IQ: Intelligence quotient.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Amar 1998 | This same study was described in DeGiorgio 2000 |

| Ben‐Menachem 1994 | This article does not mention whether intellectually disabled participants were included |

| Bergqvist 2005 | 71% of the population had an intellectual disability; however all children were younger than age 12 |

| Clarke 1997A | 2 participants had incomplete data sets ‐ 1 had a severe intellectual disability. No other data show whether intellectually disabled individuals were included ‐ only 8 participants entered the trial |

| Clarke 1997B | This article does not mention whether intellectually disabled individuals were included |

| Cross 2012 | This study was not an RCT |

| Dahl 1985 | Exclusion criteria: no severe learning disabilities or mental disturbance. Only 1 of 18 participants included in the study had a mild intellectual disability |

| Dahl 1987 | Only 3 of 18 participants had a moderate intellectual disability ‐ inclusion criteria stated that participants had to have the ability to understand and follow instructions |

| Dave 1993 | This article states that data on children with an intellectual disability and with epilepsy were provided by an open, non‐controlled study |

| Deepak 1994 | This article states: "clinically, patients had no other abnormalities except complaints of seizures" |

| DeGiorgio 1997 | This article states that patients unable to give proper consent were excluded |

| DeGiorgio 2005 | This article does not mention inclusion of intellectually disabled individuals |

| Dodrill 2001 | Analysis was done only on data from individuals without an intellectual disability (those with an intellectual disability were initially recruited) |

| Elger 2000 | Individuals with an intellectual disability were not mentioned in the article, and all participants gave informed consent |

| Engelberts 2002 | This study excluded intellectually disabled individuals |

| Freeman 2009a | This study included only children between 1 and 10 years of age |

| Gates 2005 | This abstract does not mention intellectually disabled individuals; no follow‐up article is available |

| Handforth 1998 | This article does not mention inclusion of intellectually disabled individuals |

| Helgeson 1990 | This study excluded individuals with an intellectual disability |

| Helmstaedter 2011 | Participants did not have an intellectual disability |

| Hermann 1993 | This study excluded intellectually disabled individuals |

| Holder 1992 | This article states that inclusion criteria include the "ability to understand consent and required study procedure" |

| Inuzuka 2005 | This abstract does not mention intellectually disabled individuals, and no follow‐up article is available |

| Kockelmann 2005 | This abstract does not mention intellectually disabled individuals, and no follow‐up article is available |

| Koubeisse 2013 | Participants did not have an intellectual disability |

| Landy 1993 | This article states "no concurrent significant medical problems" and makes no mention of an intellectually disabled population |

| Lemmon 2012 | This was not an RCT |

| Liu 2012 | This was not an RCT |

| Lutz 2004 | This study excluded individuals with an intellectual disability |

| Olley 2001 | This study excluded individuals with an intellectual disability |

| Panjwani 1987 | This article does not mention intellectual disabilities in describing the clinical characteristics of participants |

| Puskarich 1992 | This study excluded individuals with an intellectual disability |

| Ramsay 1994 | The article does not mention inclusion of intellectually disabled individuals |

| Scherrmann 2001 | This article does not mention inclusion of intellectually disabled individuals and does not indicate whether the entire population was included in an RCT |

| Sidorenko 2000 | This article does not mention inclusion of intellectually disabled individuals |

| Tan 1986 | This study excluded individuals with an intellectual disability |

| VNS Study Group 1995 | This article does not mention inclusion of intellectually disabled individuals |

| Warner 1997 | This study excluded individuals with an intellectual disability |

| Wu 2008 | This study included only children between 1 and 6 years of age |

| Wyler 1995 | This study excluded individuals with an intellectual disability |

| Yuen 2005 | This article does not mention inclusion of intellectually disabled individuals |

RCT: Randomised controlled trial.

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Bjurulf 2008.

| Trial name or title | Ketogenic Diet versus Antiepileptic Drug Treatment in Drug Resistant Epilepsy |

| Methods | Randomised, open‐label, parallel efficacy study |

| Participants | Estimated 60 people with drug‐resistant epilepsy will be recruited. It is unclear whether a sufficient number of participants will have intellectual disabilities and therefore whether the study will be relevant for this review |

| Interventions | Ketogenic diet vs antiepileptic medication |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measures:

Secondary outcome measures:

|

| Starting date | November 2007 |

| Contact information | BJORNB@ous‐hf.no |

| Notes | Study author informed us that a paper has been submitted and should be published later by the end of 2015. |

EEG: Electroencephalogram. RCT: Randomised controlled trial.

Contributions of authors

Cerian F Jackson was responsible for assessing studies for eligibility, extracting data, assessing risk of bias and writing the updated review.

Selina M Makin assessed studies for eligibility, extracted data, assessed risk of bias and assisted in writing the updated review.

Michael Kerr supervised completion of the updated review and provided expert opinion and feedback.

Anthony G Marson supervised completion of the updated review and provided expert opinions and feedback.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Baily Thomas Foundation Charitable Fund, UK.

-

National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), UK.

This review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Epilepsy Group. The views and opinons expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect thos of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Liang 2010 {published data only}

- Liang S, Li A, Zhao M, Jiang H, Meng X, Sun Y. Anterior temporal lobectomy combined with anterior corpus callosotomy in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and mental retardation. Seizure 2010;19(6):330‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Amar 1998 {published data only}

- Amar AP, Heck CN, Levy ML, Smith T, DeGiorgio CM, Oviedo S. An institutional experience with cervical vagus nerve trunk stimulation for medically refractory epilepsy: rationale, technique, and outcome. Neurosurgery 1998;43(6):1265‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgio CM, Schachter SC, Hadfort A, Salinsky M, Thompson J, Uthman B, et al. Prospective long‐term study of vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of refractory seizures. Epilepsia 2000;41:1195‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ben‐Menachem 1994 {published data only}

- Ben‐Menachem E, Mañon‐Espaillat R, Ristanovic R, Wilder BJ, Stefan H, Mirza W. Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment of partial seizures: 1. A controlled study of effect on seizures. First International Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. Epilepsia 1994;35(3):616‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bergqvist 2005 {published data only}

- Bergqvist AG, Schall JI, Gallagher PR, Cnaan A, Stallings VA. Fasting versus gradual initiation of the ketogenic diet: a prospective, randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Epilepsia 2005;46(11):1810‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 1997A {published data only}

- Clarke BM, Upton AR, Griffin H, Fitzpatrick D, DeNardis M. Chronic stimulation of the left vagus nerve: cognitive motor effects. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 1997;24(3):226‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 1997B {published data only}

- Clarke BM, Upton AR, Griffin H, Fitzpatrick D, DeNardis M. Seizure control after stimulation of the vagus nerve: clinical outcome measures. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 1997;24(3):222‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cross 2012 {published data only}

- Cross JH. The ketogenic diet in the treatment of Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2012;54(5):394‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dahl 1985 {published data only}

- Dahl J, Melin L, Brorson LO, Schollin J. Effects of a broad‐spectrum behavior modification treatment program on children with refractory epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1985;26(4):303‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dahl 1987 {published data only}

- Dahl J, Melin L, Lund L. Effects of a contingent relaxation treatment program on adults with refractory epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1987;28(2):125‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dave 1993 {published data only}

- Dave UP, Chauvan V, Dalvi J. Evaluation of BR‐16 A (Mentat) in cognitive and behavioural dysfunction of mentally retarded children ‐ a placebo‐controlled study. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 1993;60(3):423‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deepak 1994 {published data only}

- Deepak KK, Manchanda SK, Maheshwari MC. Meditation improves clinicoelectroencephalographic measures in drug‐resistant epileptics. Biofeedback & Self Regulation 1994;19(1):25‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DeGiorgio 1997 {published data only}

- Degiorgio C, Heck C, Smith T, Duffell W. Randomised double‐blind study of vagus nerve stimulation in intractable partial seizures. The USC experience and the EUS Study Group. Epilepsia 1997;38(S3):245. [Google Scholar]

DeGiorgio 2005 {published data only}

- DeGiorgio C, Heck C, Bunch S, Britton J, Green P, Lancman M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for epilepsy: randomized comparison of three stimulation paradigms. Neurology 2005;65(2):317‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dodrill 2001 {published data only}

- Dodrill CB, Morris GL. Effects of vagal nerve stimulation on cognition and quality of life in epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior 2001;2(1):46‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Elger 2000 {published data only}

- Elger G, Hoppe C, Falkai P, Rush AJ, Elger CE. Vagus nerve stimulation is associated with mood improvements in epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Research 2000;42(2‐3):203‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Engelberts 2002 {published data only}

- Engelberts NH, Klein M, Adèr HJ, Heimans JJ, Trenité DG, Ploeg HM. The effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation for attention deficits in focal seizures: a randomized controlled study. Epilepsia 2002;43(6):587‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freeman 2009a {published data only}

- Freeman JM, Vining EPG, Kossoff EH, Pyzik PL, Ye X, Goodman SN. A blinded, crossover study of the efficacy of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 2009;50(2):322‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gates 2005 {published data only}

- Gates JR, Liow K, Granner M, Louis E, Leroy R, Albers L, et al. Vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) parameter settings: high stimulation vs low stimulation. Epilepsia 2005;46(S8):223. [Google Scholar]

Handforth 1998 {published data only}

- Handforth A, DeGiorgio CM, Schachter SC, Uthman BM, Naritoku DK, Tecoma ES, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation therapy for partial‐onset seizures: a randomized active‐control trial. Neurology 1998;51(1):48‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Helgeson 1990 {published data only}

- Helgeson DC, Mittan R, Tan SY, Chayasirisobhon S. Sepulveda Epilepsy Education: the efficacy of a psychoeducational treatment program in treating medical and psychosocial aspects of epilepsy. Epilepsia 1990;31(1):75‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Helmstaedter 2011 {published data only}

- Helmstaedter C, Roeske S, Kaaden S, Elger CE, Schramm J. Hippocampal resection length and memory outcome in selective epilepsy surgery. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry 2011;82(12):1375‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hermann 1993 {published data only}

- Hermann BP, Wyler AR, Somes G, Peterson J, Clement L. Randomized clinical trial of partial versus total hippocampectomy for treatment of intractable temporal lobe epilepsy: memory outcome. Epilepsia 1993;34(S6):109. [Google Scholar]

Holder 1992 {published data only}

- Holder LK, Wernicke JF, Tarver WB. Treatment of refractory partial seizures: preliminary results of a controlled study. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology 1992;15(10 pt 2):1557‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Inuzuka 2005 {published data only}

- Inuzuka L, Bustamante VCT, Funayama SS, Bianchin MM, Rosset SRE, Machado HR, et al. Ketogenic diet: clinical and neurophysiological findings in refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia 2005;46(S8):28. [Google Scholar]

Kockelmann 2005 {published data only}

- Kockelmann E, Richter S, Thulke S, Schramm J, Helmstaedter C. Effect of mesial pathology and extent of resection on seizure and memory outcome after selective amygdala‐hippocampectomy (SAH). Epilepsia 2005;46(S6):328. [Google Scholar]

Koubeisse 2013 {published data only}

- Koubeissi MZ, Kahriman E, Syed TU, Miller J, Durand DM. Low‐frequency electrical stimulation of fiber tract in temporal lobe epilepsy. Annals of Neurology 2013;74(2):223‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Landy 1993 {published data only}

- Landy HJ, Ramsay RE, Slater J, Casiano RR, Morgan R. Vagus nerve stimulation for complex partial seizures: surgical technique, safety, and efficacy. Journal of Neurosurgery 1993;78(1):26‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lemmon 2012 {published data only}

- Lemmon ME, Terao NN, NG Y‐T, Reisig W, Rubenstein JE, Kossoff EH. Efficacy of the ketogenic diet in Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome: a retrospective review of one institution's experience and summary of the literature. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2012;54(5):464‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liu 2012 {published data only}

- Liu S‐Y, An N, Fang X, Singh P, Oommen J, Yin Q, et al. Surgical treatment of patients with Lennox‐Gastaut syndrome phenotype. Neurology 2011;77(15):1473‐81. [Google Scholar]

Lutz 2004 {published data only}

- Lutz MT, Clusmann H, Elger CE, Schramm J, Helmstaedter C. Neuropsychological outcome after selective amygdalohippocampectomy with transsylvian versus transcortical approach: a randomized prospective clinical trial of surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 2004;45(7):809‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Olley 2001 {published data only}

- Olley BO, Osinowo HO, Brieger WR. Psycho‐educational therapy among Nigerian adult patients with epilepsy: a controlled outcome study. Patient Education and Counseling 2001;42(1):25‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Panjwani 1987 {published data only}

- Panjwani U, Selvamurthy W, Singh SH, Gupta HL, Thakur L, Rai UC. Effect of Sahaja yoga practice on seizure control & EEG changes in patients of epilepsy. Indian Journal of Medical Research 1987;103:165‐72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Puskarich 1992 {published data only}

- Puskarich CA, Whitman S, Dell J, Hughes JR, Rosen AJ, Hermann BP. Controlled examination of effects of progressive relaxation training on seizure reduction. Epilepsia 1992;33(4):675‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ramsay 1994 {published data only}

- Ramsay RE, Uthman BM, Augustinsson LE, Upton AR, Naritoku D, Willis J. Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment of partial seizures: 2. Safety, side effects, and tolerability. First International Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. Epilepsia 1994;35(3):627‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scherrmann 2001 {published data only}

- Scherrmann J, Hoppe C, Kral T, Schramm J, Elger CE. Vagus nerve stimulation: clinical experience in a large patient series. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 2001;18(5):408‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sidorenko 2000 {published data only}

- Sidorenko VN. Effects of the Medical Resonance Therapy Music in the complex treatment of epileptic patients. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science 2000;35(3):212‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tan 1986 {published data only}

- Tan SY, Bruni J. Cognitive‐behavior therapy with adult patients with epilepsy: a controlled outcome study. Epilepsia 1986;27(3):225‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

VNS Study Group 1995 {published data only}

- The Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. A randomized controlled trial of chronic vagus nerve stimulation for treatment of medically intractable seizures. The Vagus Nerve Stimulation Study Group. Neurology 1995;45(2):224‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Warner 1997 {published data only}

- Warner MH, Anderson GD, McCarty JP, Farwell JR. Effect of carnitine on measures of energy levels, mood, cognition, and sleep in adolescents with epilepsy treated with valproate. Journal of Epilepsy 1997;10(3):126‐30. [Google Scholar]

Wu 2008 {published data only}

- Wu Y, Zou LP, Han TL, Zheng H, Caspi O, Wong V, et al. Randomized controlled trial of traditional Chinese medicine (acupuncture and tuina) in cerebral palsy: Part 1 ‐ Any increase in seizure in integrated acupuncture and rehabilitation group versus rehabilitation group?. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2008;14(8):1005‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wyler 1995 {published data only}

- Wyler AR, Hermann BP, Somes G. Extent of medial temporal resection on outcome from anterior temporal lobectomy: a randomized prospective study. Neurosurgery 1995;37(5):982‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yuen 2005 {published data only}

- Yuen AW, Sander JW, Fluegel D, Patsalos PN, Bell GS, Johnson T. Omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation in patients with chronic epilepsy: a randomized trial. Epilepsy & Behavior 2005;7(2):253‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Bjurulf 2008 {published data only}

- Bjurulf B. Comparing ketogenic diet with the most appropriate antiepileptic drug ‐ a randomised study of children with mental retardation and drug resistant epilepsy. www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00552526 (03/10/14).

Additional references

Anand 1991

- Anand BK. Yoga and medical science. Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 1991;35(2):84‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bowley 2000

- Bowley C, Kerr M. Epilepsy and intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2000;44(5):529‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cockerell 1997

- Cockerell OC, Johnson AL, Sander J, Shorvon SD. Prognosis of epilepsy: a review and further analysis of the first nine years of the British National General Practice Study of Epilepsy, a prospective population‐based study. Epilepsia 1997;38(1):31‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Commission 1981

- Commission on Classification and Terminology of the ILAE: proposal for revised clinical and EEG classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia 1981;22:489‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Commission 1989

- Commission on Classification and Terminology of the ILAE: proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 1989;30:389‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Engel 2003

- Engel J, Wiebe S, French J, Sperling MR, Williamson P, Spencer D, et al. Practice parameter: temporal lobe and localised neocortical resections for epilepsy. Neurology 2003;60:538‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fenwick 1992

- Fenwick P. The relationship between mind, brain and seizures. Epilepsia 1992;33(6):1‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freeman 1998

- Freeman JM, Vining EPG, Pillas DJ, Pyzik PL, Casey JC, Kelly LM. The efficacy of the ketogenic diet‐‐1998: a prospective evaluation of intervention in 150 children. Pediatrics 1998;102(6):1358‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]