Abstract

Trifluoroethanol and difluoroethanol units are important motifs in bioactive molecules, but the methods to direct incorporate these units are limited. Herein, we report two organosilicon reagents for the transfer of trifluoroethanol and difluoroethanol units into molecules. Through intramolecular C-Si bond activation by alkoxyl radicals, these reagents were applied in allylation, alkylation and alkenylation reactions, enabling efficient synthesis of various tri(di)fluoromethyl group substituted alcohols. The broad applicability and general utility of the approach are highlighted by late-stage introduction of these fluoroalkyl groups to complex molecules, and the synthesis of antitumor agent Z and its difluoromethyl analog Z′.

Subject terms: Homogeneous catalysis, Reaction mechanisms, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Methods for direct incorporation of tri- and di-fluoroethanol units in molecules are relatively limited. Here, the authors report two organosilicon reagents which are applied to allylation, alkylation and alkenylation reactions as tri- and di-fluoroethanol transfer reagents.

Introduction

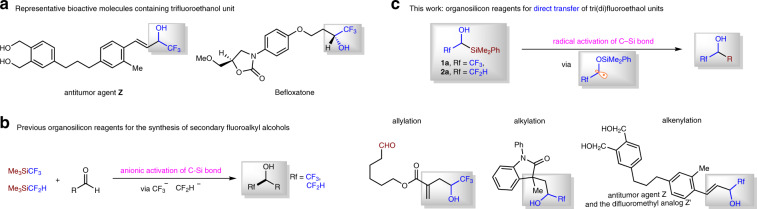

Fluorine incorporation has been a routine strategy for the design of new drugs and materials, because it can often improve the chemical, physical, and/or biological properties of organic molecules1,2. Fluoroalkylsilicon reagents, such as TMSCF3 (Rupert–Prakash reagent), TMSCF2H, and others are widely used reagents in the synthesis of organofluorine compounds3. Among various fluorine-containing molecules, the secondary fluoroalkyl alcohols are of particular importance; monoamine oxidase A inhibitor Befloxatone4 and antitumor agent Z5 are examples of bioactive molecules containing trifluoroethanol motif (Fig. 1a). Anionic activation of C–Si bond of fluoroalkylsilicon reagents by Lewis bases is a powerful method to transfer α-fluoro carbanions into aldehydes, affording fluoroalkyl alcohol products (Fig. 1b)6–8. However, we enviosioned that the development of organosilicon reagents such as 1a and 2a which allows direct transfer of trifluoroethanol and difluoroethanol into organic molecules would represent a conceptually different means to construct fluoroalkyl alcohols (Fig. 1c). Actually, the synthetic chemistry based on carbonyl group (Fig. 1b) possesses some limitations: (1) many aldehydes are not stable and/or need multistep synthesis9,10; (2) it is hard to control the regioselectivity when there are more than one aldehyde sites in the same molecule. Moreover, the design and synthesis of pharmacuticals call for strategies to incorporate important structural motifs at late-stage, because this will aviod de novo synthesis11,12.

Fig. 1. Secondary fluoroalkyl alcohol synthesis with fluorinated organosilicon reagents.

a Representative bioactive molecules containing trifluoroethanol unit. b Organosilicon reagents has been used in the synthesis for secondary fluoroalkyl alcohols via α-fluoro carbanions transfer. c Organosilicon reagents for direct transfer of tri(di)fluoroethanol units via radical activation strategy is developed (this work).

Herein, we report two fluoroalkylsilicon reagents 1a and 2a. Through intramolecular C–Si bond activation by alkoxyl radicals13–19, these developed β-fluorinated organosilicon reagents were successfully applied in radical allylation, alkylation, and alkenylation reactions, enabling efficient synthesis of a variety of fluoroalkyl group substituted alcohols (Fig. 1c). The broad applicability and general utility of the approach are highlighted by late-stage introduction of fluoroalkyl groups to complex molecules, such as the derivatives from biologically active naturally occuring epiandrosterone, cholesterol, testosterone, diosgenin, vitamin E, estrone, and (8α)-estradiol, and the synthesis of antitumor agent Z and its difluoromethyl analog Z′. Moreover, our radical reactions show conjunctive group tolerance to that of the traditional nucleophilic fluoroalkylation reactions with α-fluoro carbanions3,20,21 (Radical reactions often show different reactivity to the anionic reactions, see refs. 20,21).

Results

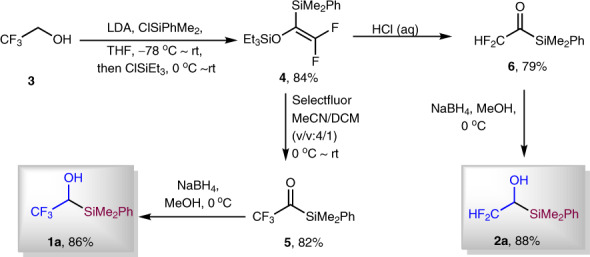

Preparation of reagents 1a and 2a

The fluoroalkyl group transfer reagents 1a and 2a were easily synthesized in three steps (Fig. 2). Following the reported procedure22, with commercially available inexpensive trifluoroethanol 3 as starting material, we prepared difluorinated enol silyl ether 4 in 84% yield. Electrophilic fluorination of compound 4 with Selectfluor afforded trifluoroacetylsilane 5 in 82% yield. Reagent 1a was then synthesized in 86% yield through reduction of acylsilane 5 with NaBH4. We also prepared different silyl group-substituted compounds 1b–1d through similar procedures as 1a in good yield (for details, see Supplementary Figs. 2–4). It is worthy to note that trifluoroacetyltriphenylsilane (precursor to 1d) can be synthesized directly from the reaction of Ph3SiLi and (CF3CO)2O in one step23. The difluoroacetylsilane 6 was easily prepared in 79% yield through the hydrolysis of enol silyl ether 4 under acidic conditions. Reduction of compound 6 delivered difluoromethyl containing reagent 2a in 88% yield.

Fig. 2. Preparation of fluoroalkyl group transfer reagents 1a and 2a.

With commercially available 3, reagents 1a and 2a are easily prepared in three steps.

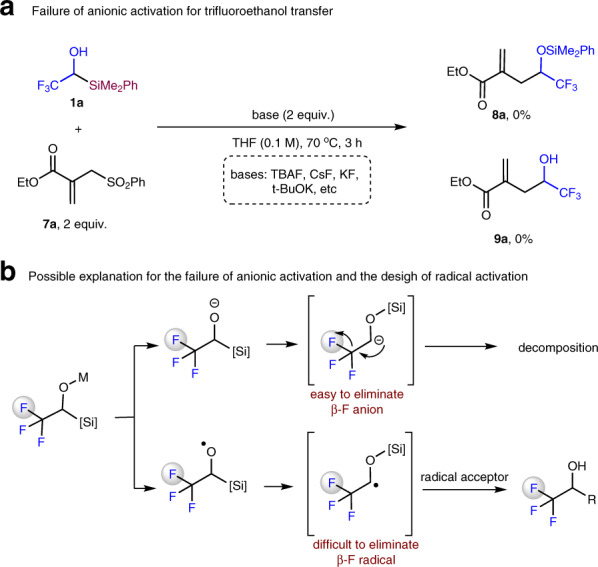

Attempts for anionic activation and design of radical activation

With reagent 1a in hand, we investigated the substitution reaction with allylic sulfone 7a as model substrate. Firstly, we tried anionic activation strategy which has been widely used in the C–Si bond cleavage for the fluoroalkyl transfer reactions6–8. Common activators such as TBAF, CsF, KF, t-BuOK were tried, but no substitution product 8a or 9a was observed, albeit full conversion of compound 1a was observed (Fig. 3a). The decomposition of compound 1a could be explained by the facile fluoride elimination of β-fluoro carbanions (Fig. 3b)23–25. For example, Xu and coworkers reported the reaction of trifluoroacetyltriphenylsilane with Grignard reagents, but no desired trifluoromethylated alcohols were obtained. Instead, 2,2-difluoro enol silyl ethers were formed through nucleophilic addition, anion Brook rearrangment, and fluoride elimination processes23. It is known that fluorine radical possesses much higher energy than fluorine anion does (Fluorine possesses high electron affinity (3.448 eV), extreme ionization energy (17.418 eV), see ref 1a, pp 5–8). Therefore, we envisioned that in-situ generated carbon radical from alkoxyl radicals should not prefer β-F elimination. Consequently, they could be trapped by radical acceptors to generate trifluoroethanol transfer products (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Attempts for anionic activation and design of radical activation.

a Attempts of anionic activation for trifluoroethanol transfer failed. b Facile β-F anion elimination might be the reason of the failure of anionic activation strategy; we designed a radical activation strategy based on the proposal that it is difficult to eliminate high-energy fluorine radical.

Identification of conditions for radical C–Si activation

With this idea in mind, we investigated a variety of conditions which could generate alkoxyl radicals (for details, see Supplementary Tables 1–3). After extensive screening, we found that employing 2 equivalent of Mn(OAc)3·2H2O as oxidant, DCM as solvent led to allylation product in 68% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Further investigation revealed that with 20 mol% of Mn(OAc)3·2H2O as catalyst and 2.5 equivalent of TBPB as oxidant, product 8 was given in 61% yield (Table 1, entry 2). Changing the silyl group from SiMe2Ph to SiMePh2 or SiEt3 resulted in only slightly decreased yield, but the SiPh3-substituted reagent 1d afforded much lower yield (Table 1, entries 3–5). It was found that Mn(OAc)2·4H2O can also be used as catalyst (Table 1, entry 6). When 20 mol% of Mn(OAc)2·4H2O was used, 1a/7a/TBPB is 1/2/2.5, a yield of 81% can be detected by 19F NMR with PhCF3 as an internal standard (Table 1, entry 7). Control experiments verified that both Mn(II) catalyst and oxidant are necessary for the success of the reaction (Table 1, entries 8 and 9). When 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol was used instead of compound 1a in our reaction, no conversion of trifluoroethanol was observed (Table 1, entry 10). The high BDE of C–H bond (409 kJ/mol) in trifluoroethanol might be one of the reasons for the difficulty in the generation of desired radical directly from trifluoroethanol under mild conditions26–29 (There are limited reports on the generation of carbon radicals from trifluoroethanol under harsh conditions, see refs. 27–29). The attempt to use Smith’s condition19 to achieve the reaction between 1a and 7a failed to afford any amount of product 8a or 9a, highlighting the influence of CF3 group on the reactivity of reagent 1a.

Table 1.

Reaction optimizationa.

| Entry | 1a/7a/oxidant | Catalyst | Oxidant | t (h) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1/1.2/0 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (2 equiv.) | Without oxidant | 18 | 68 |

| 2 | 1/1.5/2.5 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (20 mol%) | TBPB | 12 | 61 |

| 3b | 1/1.5/2.5 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (20 mol%) | TBPB | 12 | 59 |

| 4c | 1/1.5/2.5 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (20 mol%) | TBPB | 12 | 58 |

| 5d | 1/1.5/2.5 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (20 mol%) | TBPB | 12 | 45 |

| 6 | 1/1.5/2.5 | Mn(OAc)3·2H2O (20 mol%) | TBPB | 18 | 62 |

| 7 | 1/2/2.5 | Mn(OAc)2·4H2O (20 mol%) | TBPB | 18 | 81 |

| 8 | 1/2/0 | Mn(OAc)2·4H2O (20 mol%) | Without oxidant | 18 | 0 |

| 9 | 1/2/2.5 | Without catalyst | TBPB | 18 | 0 |

| 10e | 1/2/2.5 | Mn(OAc)2·4H2O (20 mol%) | TBPB | 18 | 0 |

a1a was used as the reagent, otherwise noted; the yield of the product 8 was determined by 19F NMR with PhCF3 as an internal standard.

b1b was used instead of 1a.

c1c was used instead of 1a.

d1d was used instead of 1a.

eTrifluoroethanol was used instead of 1a.

Synthesis of α-trifluoromethylated homoallylic alcohols

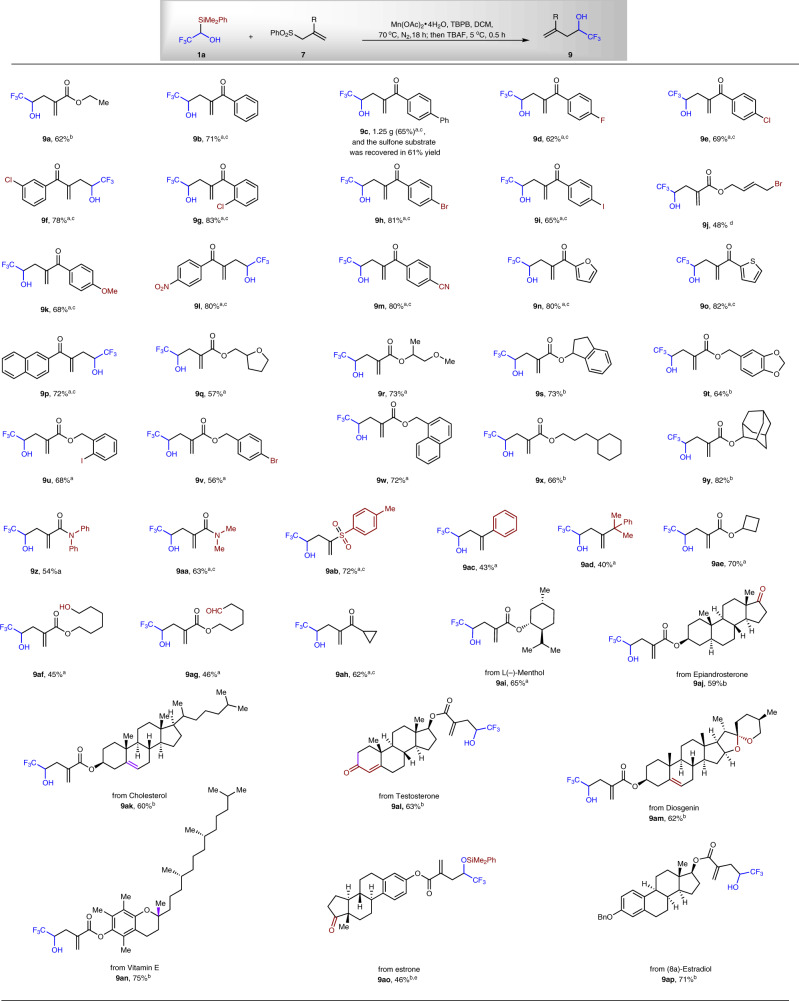

We next explored the scope of the allylic substitution reaction (Fig. 4). Both Mn(OAc)3·2H2O and Mn(OAc)2·4H2O are efficient catalysts for the transformation. When TBAF was used to quench the reaction, the silyl ether was converted to alcohol in one pot, and compound 9a was isolated in 62% yield. It was found that a variety of allylic sulfones30–34 bearing different groups could be used as the radical acceptors, affording the α-CF3-substituted homoallylic alcohols 9a–9ap in 40–83% yields. This reaction can be scaled up, and a yield of 65% was obtained for compound 9c (1.25 g isolated), and the sulfone 7c was recovered in 61% yield after silica gel chromatography. It is worth noting that the current allylation protocol can tolerate many functional groups. The Csp2–F, Csp2–Cl, Csp2–Br, Csp2–I bond can be kept after the reaction, affording compounds 9d–9i, 9u, and 9v in 56–83% yields. Moreover, allylic bromide can also be tolerated (9j, 48% yield). These functional groups are well-known convertible motifs under transition metal-mediated/catalyzed reactions. Electron donating OMe group, electron withdrawing groups, such as NO2, CN can also be tolerated, affording compounds 9k–9m in 68–80% yields. Electron-rich heterocyclic groups, such as furyl and thienyl are also be tolerated (9n, 80% yield; 9o, 82% yield). Naphthyl-substituted product was also successfully made via the Mn-catalyzed substitution reaction, affording alcohol 9p in 72% yield. A variety of alkyl ethers and benzylic alcohol-derived esters are tolerated under the current oxidation conditions, and alcohols 9q–9w were obtained in 56–73% yields. Not only ester-substituted and ketone-substituted allylic sulfones, but also amide, sulfone, phenyl, and alkyl groups-substituted allylic sulfones can be applied in the current substitution process, affording corresponding α-CF3-substituted homoallylic alcohols (9z–9ad, 40–72% yields). Moreover, this substitution process is compatible with many base-sensitive functionality, such as primary alcohol (9af, 45% yield), alkyl aldehyde (9ag, 46% yield), alkyl ketone (9ah, 62% yield; 9aj, 59% yield; 9al, 63% yield; 9ao, 46% yield). It is worthy to note that the above-mentioned aldehyde and ketone-containing products are challenging to be synthesized by methods based on these functional groups3. In addition, the current radical allylic substitution can be applied in the functionalization of complex molecules, such as the derivatives from biologically active naturally occuring epiandrosterone, cholesterol, testosterone, diosgenin, vitamin E, estrone, and (8α)-estradiol, affording corresponding alcohols 9ai–9ap in 46–75% yields.

Fig. 4. Scope for the allylation of reagent 1a.

a1a/7 = 1/3, b1a/7 = 1/2, and cMn(OAc)3·2H2O was used instead of Mn(OAc)2·4H2O. d2 equivalent of Mn(OAc)3·2H2O was used without TBPB. eInstead of TBAF, water was used to quench the reaction.

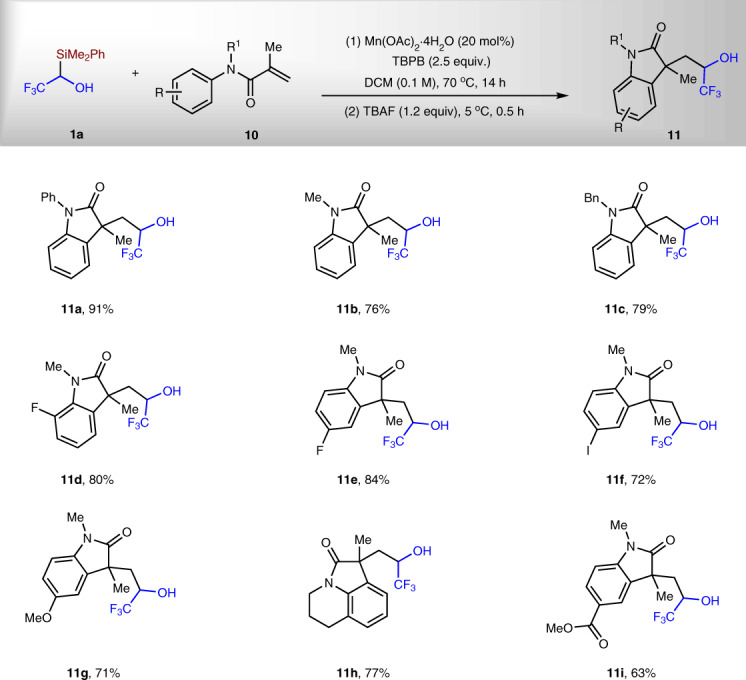

Synthesis of α-trifluoromethylated alkyl alcohols

After achieving the radical C–Si bond activation to access α-trifluoromethylated homoallylic alcohols, we wondered whether the same strategy can be applied in double functionalization of alkenes to prepare α-trifluoromethylated alkyl alcohols. Acryl amides 10 were chosen to test the possibility35–38. To our delight, under Mn(II)/TBPB conditions, various acryl amides can be converted to corresponding trifluoromethylated alcohols 11 in 63–91% yield (Fig. 5). Me, Ph, and Bn groups on the N of amides do not affect the reaction. The reaction tolerates halides, such as F and Cl. Both electron-donating OMe and electron-withdrawing CO2Me on the arenes were maintained after the reaction. It is worthy to note that compounds 11 are difficult to be synthesized through the nucleophilic trifluoromethylation reaction of aldehydes with TMSCF3, because the aldehydes themselves need multistep synthesis10.

Fig. 5. Synthesis of α-trifluoromethylated alkyl alcohols.

All reactions were run under the standard conditions with 1a/10 = 1/2.

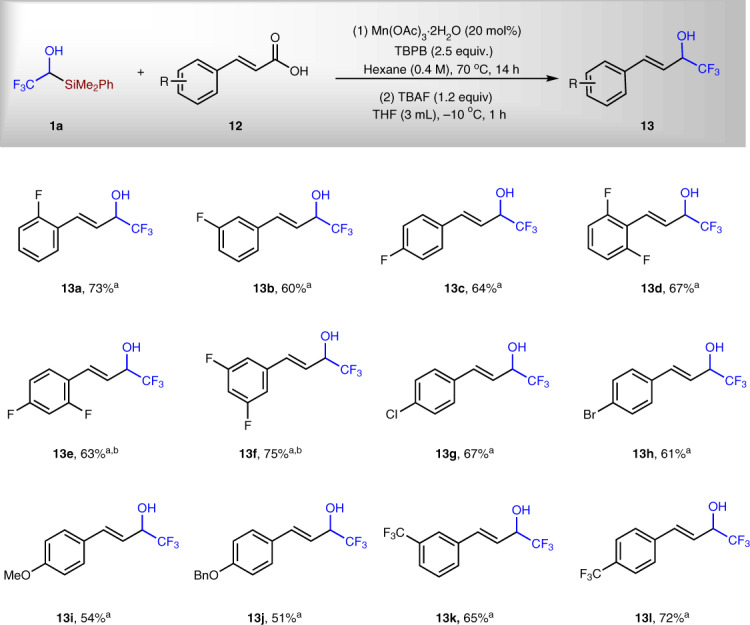

Synthesis of α-trifluoromethylated allylic alcohols

Allylic alcohols are important synthetic intermediates for a variety of transformations. Moreover, fluorinated compounds possess unique chemical, physical, and biological properties. Therefore, the development of one step synthesis of α-trifluoromethylated allylic alcohols from readily available starting materials are highly desired. Previous methods to prepare α-trifluoromethylated allylic alcohols mainly rely on nucleophilic trifluoromethylation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes39–43. α,β-Unsaturated carboxylic acids are easy to be synthesized and many of them are commercially available. Moreover, they are more stable under atmosphere than corresponding α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. They have been used in the decarboxylative trifluoromethylation reactions for the synthesis of CF3-substituted alkenes44,45. Encouraged by the success of synthesizing homoallylic and alkyl alcohols with 1a as reagent under the radical C–Si bond activation conditions, we studied the reaction between 1a and acids 12 to prepare α-trifluoromethylated allylic alcohols (Fig. 6). The reaction conditions are slightly different from the above allylation and alkylation reactions: (1) both hexane and DCM could be used as solvent; (2) the desilylation step was performed under lower temperature (−10 vs. 5 °C) to avoid side reactions. It can be found from Fig. 7 that various α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids containing F, Cl, Br, MeO, BnO, and CF3 substituents were successfully converted to corresponding α-trifluoromethylated allylic alcohols in 51–75% yield. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report on the synthesis of α-trifluoromethylated allylic alcohols with unsaturated carboxylic acids before this work.

Fig. 6. Synthesis of α-trifluoromethylated allylic alcohols.

aReactions were run under standard conditions with 1a/12 = 1/2. bDCM was used as solvent instead of hexanes.

Fig. 7. Synthesis of α-difluoromethylated alcohols.

aMn(OAc)3·2H2O (20 mol%) was used as catalyst. bMn(OAc)2·4H2O (20 mol%) was used as catalyst. cDCM (0.1 M) was used as solvent. dHexane (0.4 M) was used as solvent. et = 18 h and ft = 14 h.

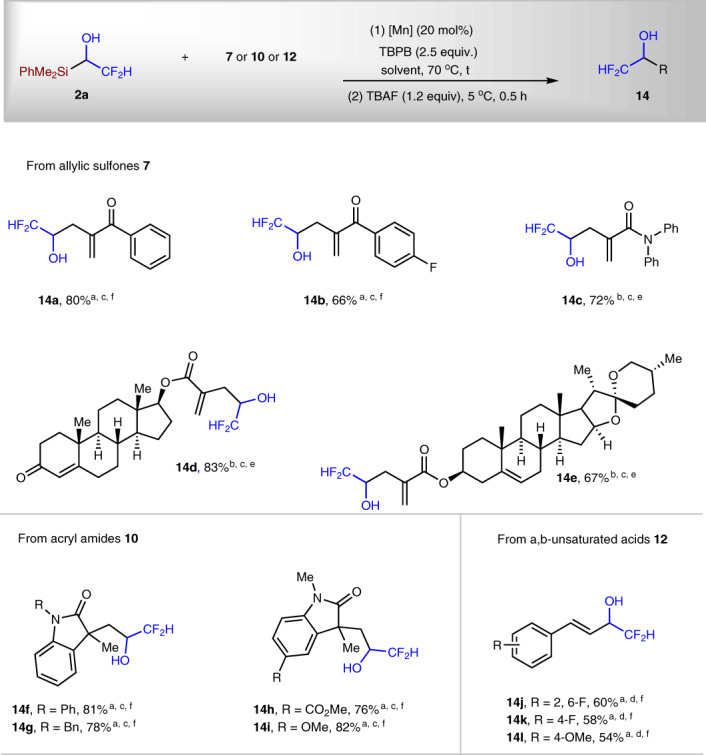

Radical C–Si activation for difluoroethanol unit transfer

Difluoromethyl group (CF2H) is isopolar and isosteric to an SH or OH group, and can also behave as a hydrogen donor through hydrogen bonding46,47. Therefore, difluoromethylated compounds are strong candidate for drugs. There are examples showing that the CF2H-containing compounds exhibit higher bioactivity than their CF3-containing counterparts48,49. Encouraged by the above success of radical C–Si bond activation to access trifluoromethylated allylic, alkyl, and alkenyl alcohols, we extended the strategy to directly transfer 2,2-difluoroethanol to organic molecules with reagent 2a (Fig. 7). To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report of the synthetic application of carbon radical from 2,2-difuoroethanol. Under the similar reaction conditions as that of 1a, with allylic sulfones as substrates, difluoromethylated homoallylic alcohols 14a–14c were prepared in 66–80% yield. Late-stage functionalization of two complex molecules are also successful; 14d and 14e were isolated in 83% and 67% yield, respectively. The reactions of acryl amides performed well, affording 14f–14i in 76–82% yield. Ph, Bn, and Me groups on the N atom were tolerated; both electron-withdrawing CO2Me and electron-donating OMe groups on the aromatic ring were maintained after the reactions. Three examples of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids demonstrated the utility of synthesis of difluoromethyl group-substituted allylic alcohols 14j–14l in synthetically useful yield.

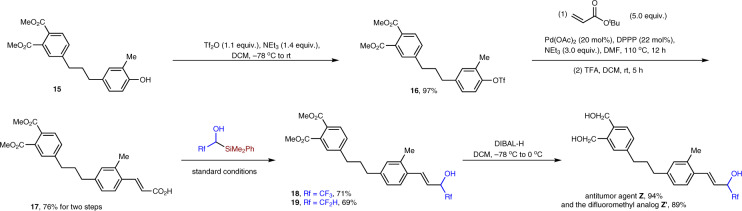

Synthesis of antitumor agent Z and its difluoromethyl analog Z′

After achieving the direct transfer of 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol and 2,2-difluoroethanol to simple α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids, we tested whether our methodology can be applied in the synthesis of antitumor agent Z (Fig. 8)5. Starting from known compound 15 5, the protection of phenol afforded compound 16 in 97% yield. α,β-Unsaturated carboxylic acid 17 was then synthesized in 76% yield after Heck reaction and selective hydrolysis of the ester. The radical reactions performed well under our standard conditions, affording compounds 18 and 19 in 71% yield and 69% yield, respectively. Hydrolysis of the esters afforded the final product Z and Z′ in 94% and 89% yield, respectively.

Fig. 8. Synthesis of antitumor agent Z and its difluoromethyl analog Z′.

Tf2O trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride, DPPP bis(diphenylphosphino)propane, TFA trifluoroacetic acid, DIBAL-H diisobutylaluminum hydride.

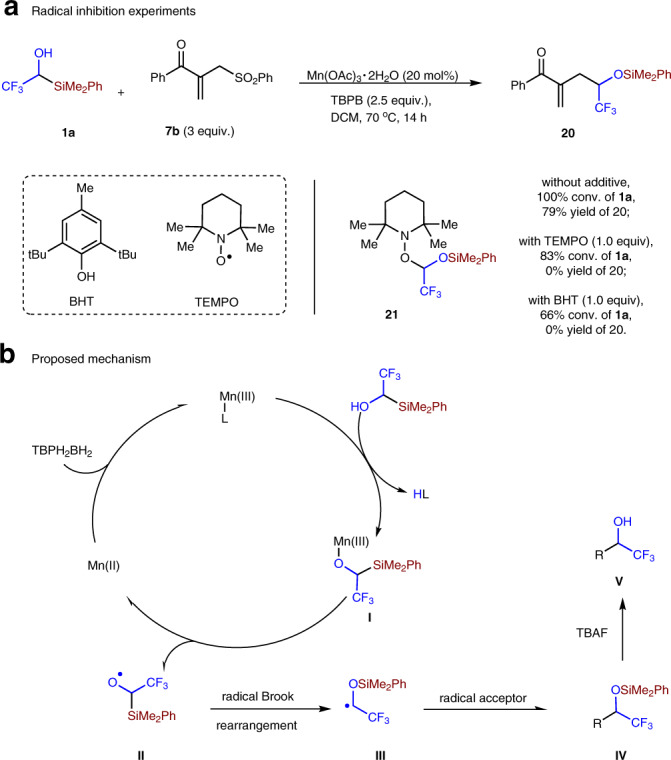

Mechanism of the study

The radical inhibition experiments revealed that addition of 1 equiv. of TEMPO or BHT can completely inhibit the allylation reaction, albeit more than 60% of compound 3a were consumed in both cases (Fig. 9a). In addition, compound 21 was detected by HRMS when TEMPO was added into the reaction (for details, see Supporting Information). Therefore, radical process might be involved in current substitution reaction. Our investigation revealed that Mn(OAc)3·2H2O is able to mediate the reaction without external oxidant, but Mn(OAc)2·4H2O cannot mediate the reaction without TBPB (Table 1, entries 1 and 8). Based on these results, we propose a possible mechanism as shown in Fig. 9b. Ligand exchange between Mn(III) species and alcohol 1a might generate intermediate I, which undergoes homolysis to produce alkoxyl radical II and Mn(II) intermediate50–53. Carbon radical III would be generated through Brook rearrangement, and then undergo further reaction to generate product IV. Mn(III) catalyst is likely to be regenerated by the oxidation of Mn(II) by TBPB. The alcohol product V would be generated after the desilylation step. It is worthy to note that the reaction pathways in the allylation, alkylation, and alkenylation reactions are probably different (for the proposed possibilities, see Supplementary Figs. 13–15). As for the nature of radical III, we propose that they are nucleophilic radicals. The following facts support this proposal: (1) the reaction partners in the above three kinds of reactions are electron-deficient olefins; (2) more electron-deficient substrate afforded higher yield (for example, Fig. 5, 9ac, 43% yield; 9ae, 70% yield); (3) the carbon radical generated from trifluoroethanol under γ-ray irradiation could add to highly electrophilic hexafluoro-2-butyne27.

Fig. 9. Radical inhibition experiments and proposed mechanism.

a TEMPO and BHT efficiently inhibited the allylation reaction, supporting radical process might be involved. b A plausible mechanism is proposed.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed two fluorinated organosilicon reagents, which were used in direct transfer of trifluoroethanol and difluoroethanol units into organic molecules. A radical C–Si bond activation strategy was developed to solve the problem of β-fluorine elimination in anionic activation methods. Upon intramolecular activation of C–Si bond by alkoxyl radicals, the β-fluoro carbon radicals were generated and participated in efficient allylation, alkylation, and alkenylation reactions, enabling efficient synthesis of numerous fluoroalkyl alcohols. The broad applicability and general utility of the approach are highlighted by late-stage introduction of fluoroalkyl groups to complex molecules and the synthesis of antitumor agent Z and its difluoromethyl analog Z′. Further application of the radical C–Si bond activation of organosilicon reagents are underway in our lab.

Methods

Typical synthesis of compound 9

Under N2 atmosphere, to a dried 10 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar containing Mn(OAc)2·4H2O (14.7 mg, 0.06 mmol, 20 mol%) was added DCM (3 mL, 0.1 M), 1a (70.2 mg, 0.3 mmol), 7a (152.4 mg, 0.6 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), and TBPB (145.7 mg, 0.75 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) sequentially. The tube was sealed, and the resulting mixture was kept stirring at 70 °C in a heating block for 18 h. The mixture was then cooled to 5 °C with ice bath, TBAF (1.0 M in THF, 0.36 mL, 0.36 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) was added and the resulting mixture was stirred at 5 °C for 0.5 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (2 mL), extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL) and organic phase was combined and washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified with column chromatography on silica gel (200–300 mesh) and PE/EA (20/1–10/1, v/v) as eluent to afford 40.0 mg of compound 9a as a colorless oil (62% yield).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to NSFC (21901191), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042018kf0023, 2042019kf0006), State Key Laboratory of Bioorganic & Natural Products Chemistry (BNPC18237) and Wuhan University for financial support. We thank Prof. Tobias Ritter (Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung, Germany), Prof. Jinbo Hu (Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, China), and Prof. Amir H. Hoveyda (Boston College, USA) for helpful discussion. We are thankful to Prof. Aiwen Lei and Prof. Xumu Zhang at Wuhan University for the generous provision of laboratory and facilities.

Author contributions

X.S. designed and directed the investigations and composed the manuscript with revisions provided by the other authors. X.C., X.G., and X.S. were involved in the invention of the reagents 1a and 2a. X.C. and X.G. developed the catalytic method. X.C., X.G., Z.L., G.Z., and Z.Z. studied the substrate scope. X.C., X.G., Z.L., G.Z., Z.Z., W.Z., S.L., and X.S. were involved in the analyses of results and discussions of the project.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: X.S., X.C., and X.G. have applied a patent based on the work of this manuscript. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiang Chen, Xingxing Gong.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-16380-9.

References

- 1.Kirsch P. Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry: Synthesis, Reactivity, Applications. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Purser S, Moore PR, Swallow S, Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:320–330. doi: 10.1039/b610213c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang T, Neumann CN, Ritter T. Introduction of fluorine and fluorine-containing functional groups. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8214–8264. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wouters J, et al. A reversible monoamine oxidase an inhibitor, befloxatone: structural approach of its mechanism of action. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:1683–1693. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biadatti, T., Thoreau, E., Voegel, J. & Jomard, A. Analogues of vitamin D. PCT Int. Appl. WO 2004020379 A1 20040311 (2004).

- 6.Prakash GKS, Krishnamurti R, Olah GA. Synthetic methods and reactions. 141. Fluoride-induced trifluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds with trifluoromethyltrimethylsilane (TMS-CF3). A trifluoromethide equivalent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:393–395. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash GKS, et al. Long-lived trifluoromethanide anion: a key intermediate in nucleophilic trifluoromethylations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:11575–11578. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Huang W, Zheng J, Hu J. Efficient and direct nucleophilic difluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds and imines with me3sicf2h at ambient or low temperature. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5342–5345. doi: 10.1021/ol202208b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y, Tian M-M, Zhang X-Y, Fan X-S. Synthesis of 4-Oxo-but-2-enals through tBuONO and TEMPO-promoted cascade reactions of homoallylic alcohols. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2016;5:1318–1322. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ou W, Zhang G, Wu J, Su C. Photocatalytic cascade radical cyclization approach to bioactive indoline-alkaloids over donor–acceptor type conjugated microporous polymer. ACS Catal. 2019;9:5178–5183. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P, Krska SW. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox for late stage functionalization of drug-like molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:546–576. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00628g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumann CN, Ritter T. Late-stage fluorination: fancy novelty or useful tool? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:3216–3221. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renaud, P. & Sibi, M. P. (eds) Radicals in Organic Synthesis (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2001).

- 14.Hu A, Guo J-J, Pan H, Zuo Z. Selective functionalization of methane, ethane, and higher alkanes by cerium photocatalysis. Science. 2018;361:668–672. doi: 10.1126/science.aat9750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia K, Zhang F, Huang H, Chen Y. Visible-light-induced alkoxyl radical generation enables selective C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond cleavage and functionalizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1514–1517. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren R, Zhao H, Huan L, Zhu C. Manganese-catalyzed oxidative azidation of cyclobutanols: regiospecific synthesis of alkyl azides by C–C bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:12692–12696. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y, et al. Silver-catalyzed remote Csp3-H functionalization of aliphatic alcohols. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2625. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05014-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paredes MD, Alonso R. On the radical Brook rearrangement. Reactivity of α-silyl alcohols, α-silyl alcohol nitrite esters, and β-haloacylsilanes under radical-forming conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:2292–2304. doi: 10.1021/jo9912855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng Y, Liu Q, Smith AB. Oxidative [1,2]-Brook rearrangements exploiting single-electron transfer: photoredox-catalyzed alkylations and arylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9487–9490. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Lear JM, Rafferty SM, Fosu SC, Nagib DA. Ketyl radical reactivity via atom transfer catalysis. Science. 2018;362:225–229. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu GC. Transition-metal catalysis of nucleophilic substitution reactions: a radical alternative to SN1 and SN2 processes. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017;3:692–700. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higashiya S, et al. Synthesis of mono- and difluoroacetyltrialkylsilanes and the corresponding enol silyl ethers. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:6323–6328. doi: 10.1021/jo049551o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin F, Jiang B, Xu Y. Trifluoroacetyltriphenylsilane as a potentially useful fluorine-containing building block. Preparation and its transformation into 2,2-difluoro enol silyl ethers. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:1221–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uneyama K, Katagiri T, Amii H. α-Trifluoromethylated carbanion synthons. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:817–829. doi: 10.1021/ar7002573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decostanzi M, et al. Brook/elimination/aldol reaction sequence for the direct one-pot preparation of difluorinated aldols from (trifluoromethyl)trimethylsilane and acylsilanes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016;358:526–531. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morozov I, et al. Hydroxyl radical reactions with halogenated ethanols in aqueous solution: Kinetics and thermochemistry. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2008;40:174–188. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambers RD, Jones CGP, Silverster MJ. Free-radical chemistry. Part 7[1]. Additions to hexafluoro-2-butyne. J. Fluor. Chem. 1986;32:309–317. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown SH, Crabtree RH. Making mercury-photosensitized dehydrodimerization into an organic synthetic method: vapor pressure selectivity and the behavior of functionalized substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:2935–2946. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamitanaka T, et al. H-Bonding-promoted radical addition of simple alcohols to unactivated alkenes. Green Chem. 2017;19:5230–5235. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knight DJ, Lin P, Whitham GH. 1,3-Rearrangements of some allylic sulphones. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1987;1:2707–2713. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S, Lim CJ. Tin-free radical-mediated C–C bond formations with alkyl allyl sulfones as radical precursors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3265–3267. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3265::AID-ANIE3265>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qi L, Chen Y. Polarity-reversed allylations of aldehydes, ketones, and imines enabled by Hantzsch ester in photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:13312–13315. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao Q-Q, Chen J, Yan D-M, Chen J-R, Xiao W-J. Photocatalytic hydrazonyl radical-mediated radical cyclization/allylation cascade: synthesis of dihydropyrazoles and tetrahydropyridazines. Org. Lett. 2017;19:3620–3623. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu K, Wang L, Colón-Rodríguez S, Flechsig G-U, Wang T. Amidyl radical directed remote allylation of unactivated sp3 C−H bonds by organic photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:1774–1778. doi: 10.1002/anie.201811004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei W-T, et al. Synthesis of oxindoles by iron-catalyzed oxidative 1,2-alkylarylation of activated alkenes with an aryl C(sp2)–H bond and a C(sp3)–H bond adjacent to a heteroatom. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:3638–3641. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y-M, et al. Direct annulations toward phosphorylated oxindoles: silver-catalyzed carbo-phosphorus functionalization of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:3972–3976. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mu X, Wu T, Wang H-Y, Guo Y-L, Liu G. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative aryltrifluoromethylation of activated alkenes at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:878–881. doi: 10.1021/ja210614y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu L, Wang F, Chen P, Liu G. Enantioselective construction of quaternary all-carbon centers via copper-catalyzed arylation of tertiary carbon-centered radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:1887–1892. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trost BM, Debien L. Palladium-catalyzed trimethylenemethane cycloaddition of olefins activated by the σ-electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl group. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11606–11609. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song JJ, et al. N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed trifluoromethylation of carbonyl compounds. Org. Lett. 2015;7:2193–2196. doi: 10.1021/ol050568i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levin VV, Dilman AD, Belyakov PA, Struchkova MI, Tartakovsky VA. Nucleophilic trifluoromethylation with organoboron reagents. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aikawa K, Toya W, Nakamura Y, Mikami K. Development of (trifluoromethyl)zinc reagent as trifluoromethyl anion and difluorocarbene sources. Org. Lett. 2015;17:4996–4999. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czerwinski P, Molga E, Cavallo L, Poater A, Michalak M. NHC–copper(I) halide-catalyzed direct alkynylation of trifluoromethyl ketones on water. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016;22:8089–8094. doi: 10.1002/chem.201601581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He Z, Luo T, Hu M, Cao Y, Hu J. Copper-catalyzed di-and trifluoromethylation of α, β-unsaturated carboxylic acids: a protocol for vinylic fluoroalkylations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3944–3947. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li G, et al. Nickel-catalyzed decarboxylative difluoroalkylation of α, β-unsaturated carboxylic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:3491–3495. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meanwell NA. Synopsis of some recent tactical application of bioisosteres in drug design. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2529–2591. doi: 10.1021/jm1013693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erickson JA, McLoughlin JI. Hydrogen bond donor properties of the difluoromethyl group. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:1626–1631. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gauthier JY, et al. The identification of 4,7-disubstituted naphthoic acid derivatives as UDP-competitive antagonists of P2Y14. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2836. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graneto, M. J. & Philips, W. J. 3-difluoromethylpyrazolecarbox-amide fungicides, compositions and use. U.S. Patent 5,093,347 (1992).

- 50.Demir AS, Emrullahoglu M. Manganese(III) acetate: a versatile reagent in organic chemistry. Curr. Org. Synth. 2007;4:321–351. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiba S. Mn(III)-catalyzed radical reactions of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds and cyclopropanols with vinyl azides for divergent synthesis of azaheterocycles. Chimia. 2012;66:377–381. doi: 10.2533/chimia.2012.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crossley SWM, Obradors C, Martinez RM, Shenvi RA. Mn-, Fe-, and Co-catalyzed radical hydrofunctionalizations of olefins. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:8912–9000. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Snider BB. Mechanisms of Mn(OAc)3-based oxidative free-radical additions and cyclizations. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:10738–10744. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.