Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review published in Issue 10, 2010, on droperidol for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients. Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms in patients with terminal illness and can be very unpleasant and distressing. There are several different types of antiemetic treatments that can be used to control these symptoms. Droperidol is an antipsychotic drug and has been used and studied as an antiemetic in the management of postoperative and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and adverse events (both minor and serious) associated with the use of droperidol for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients.

Search methods

We searched electronic databases including CENTRAL, MEDLINE (1950‐), EMBASE (1980‐), CINAHL (1981‐) and AMED (1985‐), using relevant search terms and synonyms. The basic search strategy was ("droperidol" OR "butyrophenone") AND ("nausea" OR "vomiting"), modified for each database. We updated the search on 2 December 2009. We performed updated searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL and AMED 2009 to 2013 on 19 November 2013 and of CINAHL on 20 November 2013. We also searched trial registers (metaRegister of controlled trials (www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct), clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/)) on 22 November 2013, using the keyword "droperidol".

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of droperidol for the treatment of nausea or vomiting, or both, in adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition.

Data collection and analysis

We judged the potential relevance of studies based on their titles and abstracts, and obtained studies that we anticipated might meet the inclusion criteria. Two review authors independently reviewed the abstracts for the initial review and four review authors reviewed the abstracts for the update to assess suitability for inclusion. We discussed discrepancies to achieve consensus.

Main results

The 2010 search strategy identified 1664 abstracts (and 827 duplicates) of which we obtained 23 studies in full as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria. On review of the full papers, we identified no studies that met the inclusion criteria.

The updated searches carried out in November 2013 identified 304 abstracts (261 excluding duplicates) of which we obtained 18 references in full as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria. On review of the full papers, we identified no studies that met the inclusion criteria, therefore there were no included studies in this review.

We found no registered trials of droperidol for the management of nausea or vomiting in palliative care.

Authors' conclusions

Since first publication of this review, no new studies were found. There is insufficient evidence to advise on the use of droperidol for the management of nausea and vomiting in palliative care. Studies of antiemetics in palliative care settings are needed to identify which agents are most effective, with minimum side effects.

Plain language summary

Droperidol for the treatment of nausea and vomiting (sickness) in people with advanced disease

Nausea (a feeling of sickness) and vomiting are common and distressing symptoms for people with advanced cancer and other life‐threatening illnesses. Several medications to control these symptoms are available. Droperidol is one example, which has been used to try to prevent or treat nausea and vomiting for people having surgery or chemotherapy. In our search updated in November 2013 we found no randomised studies of droperidol for the treatment of nausea or vomiting for people receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Several studies reported on the use of droperidol for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy. Further studies are needed to find out which medications are most suitable to treat nausea and vomiting in palliative care.

Background

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review published in Issue 10, 2010, on droperidol for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients.

Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms in patients with terminal illness and can be very distressing.

Between 40% and 70% of patients with advanced cancer are thought to suffer from nausea or vomiting (Twycross 1998), and these symptoms are also common in other terminal conditions (Edmonds 2001; Klinkenberg 2004). Antiemetic drugs can help control symptoms while the medical team undertakes an assessment of the patient and tries to treat the underlying cause. There are many such causes in patients with terminal illness, including the underlying illness (for example, bowel obstruction or metastases in the liver), biochemical disturbance (for example, renal failure or hypercalcaemia) or drugs (for example, when starting morphine). Several causes of nausea and vomiting may coexist in an individual patient. Doctors try to choose the best first choice antiemetic based on what is thought to be the underlying cause (Bentley 2001), using a second line antiemetic if the first is not effective. An antiemetic such as levomepromazine, which has effect at several receptors relevant to nausea and vomiting, is often used as a second line antiemetic.

Whilst the choice of first line antiemetic based on the likely cause of symptoms is a widespread approach, there is little evidence from randomised controlled trials for many of the drugs used for these symptoms in this patient group (for example, cyclizine, haloperidol or levomepromazine) (Davis 2010; Glare 2004).

Droperidol is one example of an antiemetic that may be used to try to reduce nausea and vomiting (Rhodes 2001). It is in the butyrophenone class of drugs and acts as a dopamine antagonist at the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the brain (Mannix 2004). Theoretically, therefore, it should be effective for biochemical causes of nausea or to reduce the emetic effect of drugs such as morphine, which is mediated through the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Haloperidol is another example of a butyrophenone and its use in this context has been systematically reviewed separately (Perkins 2009). Droperidol is used alone or together with other antiemetics orally, intravenously or intramuscularly.

In the UK, droperidol is available as an injection (2.5 mg in 1 mL), licensed for intravenous use for the prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) or the prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by morphine derivatives during postoperative patient‐controlled analgesia (PCA). For PONV the dose is 0.625 mg to 1.25 mg in adults (0.625 mg for the elderly or those with renal or hepatic impairment). For use with PCA in adults, the dose is 15 to 50 micrograms of droperidol per mg of morphine, up to a maximum daily dose of 5 mg of droperidol. There are no data on PCA for patients with renal or hepatic impairment in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC).

The United States Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning in 2001 following concerns about QT interval prolongation and deaths due to cardiac arrhythmia with the use of droperidol (Food and Drug Administration 2001). This decision has been the focus of debate (Habib 2008; Kao 2003; Ludwin 2008; Nuttall 2007). The UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Authority (MHRA) raised concerns about the potential effect of droperidol on the QT interval and requested a risk‐benefit analysis, which led to the voluntary withdrawal of some formulations of droperidol by Jansen‐Cilag (MHRA 2001). The MHRA subsequently granted marketing authorisation for droperidol to the pharmaceutical company ProStrakan, in January 2008 (MHRA 2008).

Droperidol is also known by its trade names Droleptan (Australia, New Zealand), Inapsine (US, Canada), Xomolix (UK), Droperdal (Brazil), Dehydrobenzperidol (Belgium, Luxembourg), Droperol (India), Sintodian (Italy), Dridol (Norway, Sweden), Inapsin (South Africa), Paxical (South Africa) and Dehidrobenzperidol (Spain, Portugal) (Martindale 2009).

The medical literature regarding droperidol as an antiemetic relates primarily to its use intravenously in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting or chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting. We wanted to establish whether there was any evidence to support its use in the palliative care setting.

All patients with terminal illness should have access to palliative care, independent of their diagnosis, and we wish to reflect this in our review. Defining this population has been identified as a problem in previous reviews. We used the definition 'adult patients in any setting, receiving palliative care or suffering an incurable progressive medical condition', which has previously been used in a Cochrane review (Hirst 2001).

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and adverse events (both minor and serious) associated with the use of droperidol for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of droperidol for the treatment of nausea or vomiting, or both, in any setting.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Adults suffering from nausea or vomiting, or both.

Exclusion criteria

Nausea or vomiting, or both, thought to be secondary to pregnancy or surgery; antiemetic(s) used for the prophylaxis of nausea or vomiting associated with chemotherapy.

Types of interventions

We included studies where droperidol was used to treat nausea or vomiting (alone or in addition to other agents) including any dose of droperidol, via any route, over any duration of follow‐up.

Acceptable comparators

Placebo

Other drug

Non‐pharmacological intervention

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Nausea rating: intensity, duration (the patient's report of his or her symptoms)

Vomiting severity rating (the patient's report of his or her symptoms)

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life measurement

Acceptability of treatment

Need for rescue antiemetic medication

Adverse events (including sedation, rigidity, tremor and cardiovascular side effects)

Withdrawal from study because of side effects

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched electronic databases including CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and AMED, using relevant search terms and synonyms. The basic search strategy was ("droperidol" OR "butyrophenone") AND ("nausea" OR "vomiting"), modified for each database. Handsearching complemented the electronic searches (using reference lists of included studies, relevant chapters and review articles). We did not impose a language restriction on studies. The MEDLINE search strategy is shown in Appendix 1. The search was undertaken on 23 November 2007 and updated 16 June 2009 and again on 2 December 2009.

We performed updated searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL and AMED 2009 to 2013 on 19 November 2013 and of CINAHL on 20 November 2013.

We also searched trial registers (metaRegister of controlled trials (www.controlled-trials.com/mrct), clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/)) on 22 November 2013, using the keyword "droperidol".

Data collection and analysis

We judged the potential relevance of studies based on their titles and abstracts, and obtained studies that we anticipated might meet the inclusion criteria. Two review authors independently reviewed the abstracts for the initial review and four review authors reviewed the abstracts for the update to assess suitability for inclusion. We discussed discrepancies to achieve consensus. For the initial review, a translator enabled us to assess whether two Japanese papers identified by the search met the inclusion criteria for the review (Fujii 1987; Niijima 1986). We planned to assess the quality of included papers using the Jadad criteria (Jadad 1996).

Results

Description of studies

The search strategy run on 23 November 2007 identified 1851 abstracts (1021 excluding duplicates), of which we obtained 23 references in full as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria. On review of the full papers, we identified no studies that met the inclusion criteria. We identified a further 140 abstracts when the search was updated on 16 June 2009 and we identified 48 abstracts when the search was further updated on 2 December 2009.

From assessment of these additional abstracts, none met the inclusion criteria.

The updated searches carried out in November 2013 identified 304 abstracts (261 excluding duplicates), of which we obtained 18 references in full as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria. On review of the full papers, we identified no studies that met the inclusion criteria, therefore there were no studies included in the review.

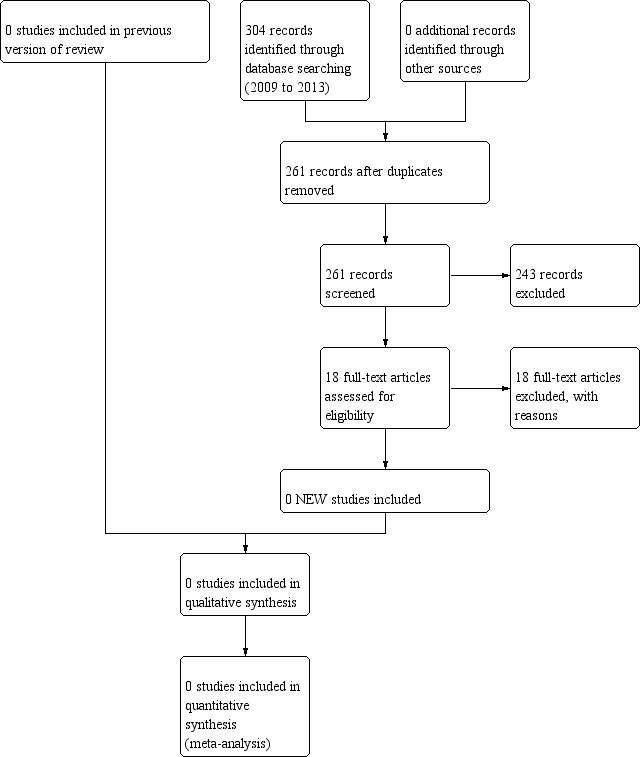

We found no registered trials of droperidol for the management of nausea or vomiting in palliative care. The study flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

We excluded 41 studies (23 from the 2010 review and 18 from the updated 2013 search) and these are detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

We included no studies.

Effects of interventions

It was not possible to draw conclusions about the effects of droperidol in the palliative care setting as we could find no included studies for this review.

Discussion

Evidence for the effectiveness of droperidol

Droperidol has been widely used as an antiemetic, particularly for the prophylaxis and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and it has been studied for the prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy (e.g. cisplatin).

Droperidol for postoperative nausea and vomiting has been systematically reviewed (Carlisle 2006), and there is some evidence for its effectiveness in this context. Carlisle's systematic review identified 222 studies examining the effectiveness of droperidol for PONV. The relative risk (compared to placebo) was 0.65 for nausea and 0.65 for vomiting. A systematic review of antiemetics for the control of PONV for patients receiving patient‐controlled analgesia found that droperidol was significantly more effective than placebo (Tramer 1999), with numbers needed to treat of 2.7 for nausea (confidence interval 1.8 to 5.2) and 3.1 for vomiting (confidence interval 2.3 to 4.8), compared to placebo.

Of the studies reporting the effectiveness of droperidol for the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with chemotherapy (Aapro 1991; Fujii 1987; Herrstedt 1991; Jacobs 1980; Kim 1994; Lehoczky 2001; Lennox 1985; Lewis 1984; Melsom 1982; Minegishi 2003; Muller 1989; Niijima 1986; Owens 1984; Poka 1993; Roberts 1985; Sagae 2003; Saller 1986; Stuart‐Harris 1983), one included only participants in the palliative stage of their illness. This was a cross‐over study of 32 in‐patients with advanced lung cancer receiving cisplatin chemotherapy (Fujii 1987). The addition of droperidol to dexamethasone and metoclopramide was reported to be associated with a shorter median duration of nausea (two days versus four days, P value < 0.05), but no significant difference in median vomiting duration or volume. However, randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding methods were not clear.

The use of droperidol as an antiemetic has also been studied in patients with severe non‐malignant low back pain who were treated with an epidural catheter (Aldrete 1995), and in patients attending the emergency department who received treatment of nausea or vomiting due to any cause (Braude 2006; Patanwala 2010).

It is not clear to what extent these studies can be extrapolated to the palliative care setting and other causes of nausea and vomiting.

Side effects

In 2001, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning against the use of droperidol, in view of case reports of prolongation of the QT interval, and cardiac arrhythmia and sudden death (Food and Drug Administration 2001).

This has been an area of controversy, with several authors subsequently defending the use of droperidol (McKeage 2006; Nuttall 2007). A full review of the relevant literature is beyond the scope of this systematic review.

Other side effects reported in the literature (in the context of postoperative nausea and vomiting and chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting) include drowsiness or sedation, akathisia, dystonia, anxiety or restlessness, euphoria, hypotension, flush, dry mouth or rigor (Aapro 1991; Braude 2006; Jacobs 1980; Roberts 1985; Sagae 2003; Saller 1986). Since droperidol is often given with other medication in these settings it can be difficult to establish causality. Sedation appears to be the most commonly reported side effect.

Droperidol in palliative care

Despite previous widespread use and research in anaesthesia and oncology, we did not find any published evidence from randomised controlled trials of the use of droperidol in palliative care settings. A letter by Thangathurai asserts the usefulness of droperidol for the palliation of nausea and vomiting (Thangathurai 2010). Haloperidol (like droperidol, a butyrophenone) is more commonly used in palliative care within the UK and its use for the management of nausea and vomiting in palliative care has been systematically reviewed separately (Perkins 2009).

Studies of antiemetics in palliative care settings are needed to identify which agents are most effective, with minimum side effects (Davis 2010).

Systematic reviews and the evidence base in palliative care

Previous systematic reviews in palliative care have been beset by the problem of the lack of evidence from original studies, particularly randomised controlled trials. Cochrane systematic reviews in palliative care published up to December 2007 were reviewed by Wee 2008, who concluded that "Cochrane reviews in palliative care ... fail to provide good evidence for clinical practice because the primary studies are few in number, small, clinically heterogeneous, and of poor quality and external validity". It can be difficult to carry out randomised controlled trials in palliative care (Grande 2000), and other methodological approaches may be useful in this context. However, Hadley et al note that good quality observational studies are also sparse (Hadley 2009).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Since first publication of this review, no new studies were found. There is insufficient evidence from randomised controlled trials at present to advise on the use of droperidol for the management of nausea and vomiting in palliative care.

Implications for research.

Studies of antiemetics in palliative care settings are needed to identify which agents are most effective, with minimum side effects.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 May 2020 | Review declared as stable | See Published notes. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2008 Review first published: Issue 10, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 November 2014 | Review declared as stable | This review will be assessed for further updating in 2020 as it is unlikely that new evidence will be published. |

| 19 November 2013 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No additional studies were identified for inclusion in this update, and the conclusions remain unchanged. |

| 19 November 2013 | New search has been performed | This review has been updated to include the results of a new search. Change of authorship. |

| 12 November 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 5 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

In May 2020, we performed a restricted updated search on MEDLINE, and also searched trial registries for relevant ongoing studies. We did not identify any potentially relevant studies for inclusion. The authors acknowledge that the number of publications on this topic has been steadily decreasing since 2002, and that most new publications relate to a postoperative setting rather than palliative care. Therefore, this review has now been stabilised following discussion between the authors and editors. If appropriate, we will update the review if new evidence likely to change the conclusions is published, or if standards change substantially which necessitate major revisions.

Acknowledgements

For the 2010 review we would like to thank the staff of the Cochrane Pain, Palliative & Supportive Care Review Group, including Jessica Thomas, Yvonne Roy, Anna Hobson, Sylvia Bickley for help with refining the search strategy, Caroline Struthers for updating the search, Mari Imamura for translation of two Japanese papers, and our peer referees, Giovambattista Zeppetella and Janet Wale, who commented on the draft of the protocol for this systematic review, and Karl Gallegos, Gerhild Becker and Andrew Moore who commented on the review. Thanks also to Linda Porter and Lyn Jackson (pharmacists) and Susan Merner (librarian) at Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

For the updated 2013 review we would like to thank Jo Abbott (Trials Search Co‐ordinator), Jane Hayes, Yvonne Roy, Mike Bennett and Phil Wiffen at The Cochrane Collaboration. We would also like to thank the librarians at the Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust and Barbara Peirce at Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Cochrane Review Group funding acknowledgement: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is the largest single funder of the Cochrane PaPaS Group. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR, National Health Service (NHS) or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL.pt. 2. CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 3. RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS.sh. 4. RANDOM ALLOCATION.sh. 5. DOUBLE BLIND METHOD.sh. 6. SINGLE BLIND METHOD.sh. 7. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 8. (ANIMALS not HUMAN).sh. 9. 7 not 8 10. CLINICAL TRIAL.pt. 11. exp CLINICAL TRIALS/ 12. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 13. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 14. PLACEBOS.sh. 15. placebo$.ti,ab. 16. random$.ti,ab. 17. RESEARCH DESIGN.sh. 18. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 19. 18 not 8 20. 19 not 9 21. COMPARATIVE STUDY.sh. 22. exp EVALUATION STUDIES/ 23. FOLLOW UP STUDIES.sh. 24. PROSPECTIVE STUDIES.sh. 25. (control$ or prospectiv$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. 26. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 27. 26 not 8 28. 27 not (9 or 20) 29. 9 or 20 or 28 30. nause$.mp. 31. vomit$.mp. 32. emesis.mp. 33. emet$.mp. 34. anti‐eme$.mp. 35. antieme$.mp. 36. antiemetics.sh. 37. nausea.sh. 38. vomiting.sh. 39. 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 40. droperidol.mp. 41. droleptan$.mp. 42. dehydrobenzperidol$.mp. 43. droperdal$.mp. 44. inapsine$.mp. 45. droperol$.mp. 46. sintodian$.mp. 47. dridol$.mp. 48. inapsin$.mp. 49. paxical$.mp. 50. dehidrobenzperidol$.mp. 51. 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 52. butyrophenone$.mp. 53. exp butyrophenones/ 54. 52 or 53 55. 51 or 54 56. 29 and 39 and 55

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aapro 1991 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Underlying diagnoses not clear. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Aldrete 1995 | Population not restricted to adults suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition |

| Braude 2006 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Any diagnosis causing nausea or vomiting |

| Casey 2011 | Not a RCT; not specific to droperidol |

| Cheung 2011 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Dale 2011 | Not a RCT; not specific to droperidol |

| Etievant 2010 | Not specific to droperidol, nausea or vomiting |

| Feyer 2011 | Prophylaxis and treatment of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting |

| Fujii 1987 | Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Getto 2011 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition |

| Glare 2011 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Gonzales 2011 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Hardy 2010 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Herrstedt 1991 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Jacobs 1980 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition (stage of cancers not documented). Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Kim 1994 | Prophylaxis of interleukin‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Lehoczky 2001 | Not randomised. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Lennox 1985 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting. Abstract only |

| Lewis 1984 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| McHugh 2011 | Not specific to droperidol |

| McNicol 2003 | Systematic review rather than randomised controlled trial. Not specific to droperidol, nausea or vomiting |

| Melsom 1982 | Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Minegishi 2003 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition (stage of cancers not documented). Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Muller 1989 | Inadequate detail to assess population (abstract only), but not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Niijima 1986 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| O'Connor 2011 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Owens 1984 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Patanwala 2010 | Not randomised. Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition |

| Poka 1993 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Richards 2011 | Not specific to droperidol, nausea or vomiting |

| Roberts 1985 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Sagae 2003 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Saller 1986 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Smith 2010 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Smith 2011 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Smith 2012 | Not specific to droperidol |

| Stuart‐Harris 1983 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Thangathurai 2010 | Not a RCT |

| Tramer 1999 | Population not restricted to adults receiving palliative care or suffering from an incurable progressive medical condition. Prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting |

| White 1992 | Not a RCT ‐ groups treated sequentially. Prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐associated nausea and vomiting |

| Yang 2011 | Not specific to droperidol, nausea or vomiting |

RCT: randomised controlled trial

Differences between protocol and review

We excluded studies of antiemetics used for the prophylaxis of nausea or vomiting associated with chemotherapy.

Contributions of authors

SD and Paul Perkins designed the original systematic review. SD and Sylvia Bickley developed the search strategy with comments from PP. SD and PP independently reviewed all titles and abstracts yielded by the search strategy (2010) and discussed any discrepancies to achieve a consensus. JS, MH and TP independently reviewed all abstracts yielded by the updated searches (2013); full papers were reviewed independently by JS, MH, TP and SD. JS, MH and TP updated the text of the review which SD wrote in 2010 with input from PP. SD is the corresponding author and contact for future updates.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Library services

-

Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Library Services

-

Southampton University Hospital Trust, UK

Library Services

External sources

-

The Cochrane Collaboration, UK

Searches and editorial review

Declarations of interest

JS: None known.

MH: None known.

TP: None known.

SD: None known.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Aapro 1991 {published data only}

- Aapro MS, Froidevaux P, Roth A, Alberto P. Antiemetic efficacy of droperidol or metoclopramide combined with dexamethasone and diphenhydramine. Oncology 1991;48:116-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aldrete 1995 {published data only}

- Aldrete J. Reduction of nausea and vomiting from epidural opioids by adding droperidol to the infusate in home-bound patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 1995;10(7):544-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Braude 2006 {published data only}

- Braude D, Soliz T, Crandall C, Hendey G, Andrews J, Weichental L. Antiemetics in the ED: a randomized controlled trial comparing 3 common agents. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2006;24:177-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Casey 2011 {published data only}

- Casey C, Chen LM, Rabow MW. Symptom management in gynaecologic malignancies. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 2011;11(7):1077-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cheung 2011 {published data only}

- Cheung WY, Zimmermann C. Pharmacologic management of cancer-related pain, dyspnea and nausea. Seminars in Oncology 2011;38(3):450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dale 2011 {published data only}

- Dale O, Moksnes K, Kaasa S. European Palliative Care Research Collaborative Pain Guidelines: Opioid switching to improve analgesia or reduce side effects. A systematic review. Palliative Medicine 2011;25(5):494-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Etievant 2010 {published data only}

- Etievant A, Betry C, Haddjeri N. Partial dopamine D2 / serotonin 5HT-1a receptor agonists as new therapeutic agents. Open Neuropsychopharmacology 2010;3:1-12. [Google Scholar]

Feyer 2011 {published data only}

- Feyer P, Jordan K. Update and new trends in antiemetic therapy: the continuing need for novel therapies. Annals of Oncology 2011;22(1):30-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fujii 1987 {published data only}

- Fujii M, Kiura K, Kamei H, Okabe K, Toki H. Antiemetic effects of combinations of metoclopramide, dexamethasone and dexamethasone for the prevention of cisplatin-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: a randomized crossover trial [Japanese]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1987;14(7):2257-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Getto 2011 {published data only}

- Getto L, Zeserson E, Breyer M. Vomiting, diarrhea, constipation and gastroenteritis. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 2011;29(2):211-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glare 2011 {published data only}

- Glare P, Miller J, Nikolova T, Tickoo R. Treating nausea and vomiting in palliative care: a review. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2011;6(1):243-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gonzales 2011 {published data only}

- Gonzales MJ, Widera E. Nausea and other non-pain symptoms in long-term care. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 2011;27(2):213-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hardy 2010 {published data only}

- Hardy JR, O'Shea A, White C, Gilshenan K, Welch L, Douglas C. The efficacy of haloperidol in the management of nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 2010;40(1):111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Herrstedt 1991 {published data only}

- Herrstedt J, Hannibal J, Hallas J, Andersen E, Laursen LC, Hansen M. High-dose metoclopramide + lorazepam versus low-dose metoclopramide + lorazepam + dehydrobenzperidol in the treatment of cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. Annals of Oncology 1991;2:223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jacobs 1980 {published data only}

- Jacobs AJ, Deppe G, Cohen CJ. A comparison of the antiemetic effects of droperidol and prochlorperazine in chemotherapy with cis-platinum. Gynecologic Oncology 1980;10:55-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kim 1994 {published data only}

- Kim H, Rosenberg SA, Steinberg SM, Cole DJ, Weber JS. A randomized double-blinded comparison of the antiemetic efficacy of ondansetron and droperidol in patients receiving high-dose interleukin-2. Journals of Immunotherapy 1994;16:60-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lehoczky 2001 {published data only}

- Lehoczky O, Bagameri A, Sarosi Z, Kulcsar T, Pulay T. Does the addition of an anxiolytic drug improve the antiemetic effectiveness of the steroid and granisetron combination in the prophylaxis of cisplatin-induced vomiting? [Fokozhato-e a szteroid es granisetron antiemeticus kombinacio hatekonysaga anxiolyticus szer hozzaadasaval a cisplatin okozta hanyas profilaxisaban?]. Orvosi Hetilap 2001;142:1681-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lennox 1985 {published data only}

- Lennox B, Reid M, McCaffrey D, Miaskowski C, Kaplan BH, Vogl SE. Randomized double-blind crossover trial of prochlorperazine (P) alone versus prochlorperazine plus droperidol (D) for emesis prophylaxis in patients (PTS) receiving intravenous bolus cis-platinum (DDP). Proceedings of American Association of Cancer Research 1985;26:189. [Google Scholar]

Lewis 1984 {published data only}

- Lewis GO, Bernath AM, Ellison NM, Gallagher JG, Porter PA, Rine KT. Double-blind crossover trial of droperidol, metoclopramide, and prochlorperazine as antiemetics in cisplatin therapy. Clinical Pharmacy 1984;3:618-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McHugh 2011 {published data only}

- McHugh ME, Miller-Saultz D. Assessment and management of gastrointestinal symptoms in advanced illness. Primary Care - Clinics in Office Practice 2011;38(2):225-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McNicol 2003 {published data only}

- McNicol A, Horowicz-Mehler N, Fisk RA, Bennett K, Gialeli-Goudas M, Chew PW, et al. Management of opioid side effects in cancer-related and chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review. Journal of Pain 2003;4(5):231-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Melsom 1982 {published data only}

- Melsom H, Nandrup E, Monge OR. Metoclopramide (Primperan) versus droperidol (Dridol) as an antiemetic in intravenous cancer chemotherapy [Metoklopramid (Primperan) versus droperidol (Dridol) som antiemetikum ved intravenos cancerkjemoterapi]. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Laegeforening 1982;102(16):914-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Minegishi 2003 {published data only}

- Minegishi Y, Ohmatsu H, Miyamoto T, Niho S, Goto K, Kubota K, et al. Efficacy of droperidol in the prevention of cisplatin-induced delayed emesis: a double-blind, randomised parallel study. European Journal of Cancer 2004;40:1188-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Muller 1989 {published data only}

- Muller G, Konig H. Antiemetic efficacy of high-dose metoclopramide and high-dose droperidol in preventing cisplatin-induced nausea and emesis: a single-blind comparison. Blut 1989;59(3):280. [Google Scholar]

Niijima 1986 {published data only}

- Niijima T, Isurugi K, Akaza H, Kondon Y, Kawabe K, Fujita K, et al. Randomised cross-over study on the effects of methylprednisolone, metoclopramide and droperidol on the control of nausea and vomiting associated with cis-platinum chemotherapy [Japanese]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 1986;13(7):2376-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Connor 2011 {published data only}

- O'Connor B, Creedon B. Pharmacological treatment of bowel obstruction in cancer patients. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 2011;12(14):2205-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Owens 1984 {published data only}

- Owens NJ, Schauer AR, Nightingale CH, Golub GR, Martin RS, Williams HM, et al. Antiemetic efficacy of prochlorperazine, haloperidol, and droperidol in cisplatin-induced emesis. Clinical Pharmacy 1984;3:167-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Patanwala 2010 {published data only}

- Patanwala AE, Amini R, Hays DP, Rosen P. Antiemetic therapy for nausea and vomiting in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Medicine 2010;39(3):330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Poka 1993 {published data only}

- Poka R, Hernadi Z, Juhasz B, Lampe L. Comparison of four antiemetic regimens for the treatment of cisplatin-induced vomiting. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 1993;42:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Richards 2011 {published data only}

- Richards JR, Richards IN, Ozery G, Derlet RW. Droperidol analgesia for opioid-tolerant patients. Journal of Emergency Medicine 2011;41(4):389-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roberts 1985 {published data only}

- Roberts WS, Wisniewski BJ, Cavanagh D, Marsden DE. Droperidol as an antiemetic in cis-platinum-induced nausea and vomiting. Oncology 1985;42:42-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sagae 2003 {published data only}

- Sagae S, Ishioka S, Fukunaka N, Terasawa K, Kobayashi K, Sugmara M, et al. Combination therapy with granisetron, methylprednisolone and droperidol as an antiemetic prophylaxis in CDDP-induced delayed emesis for gynaecologic cancer. Oncology 2003;64:46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Saller 1986 {published data only}

- Saller R, Hellenbrcht D. High doses of metoclopramide or droperidol in the prevention of cisplatin-induced emesis. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology 1986;22(10):1199-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 2010 {published data only}

- Smith T, Paice J, Ritter J, Bobb B. An evidence-based approach to cutaneous treatment of nausea, pain and neuropathy in palliative care. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 2010;39(2):372-3. [Google Scholar]

Smith 2011 {published data only}

- Smith T, Ritter JK, Coyne PJ, Parker GL, Dodson P, Fletcher DS. Testing the cutaneous absorption of lorazepam, diphenhydramine and haloperidol gel (ABH gel) used for cancer-related nausea. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011;29(15 Suppl):1. [Google Scholar]

Smith 2012 {published data only}

- Smith T, Fletcher D, Coyne P, Ritter J, Dodson P, Parker G. ABH gel (Ativan, Benadryl, Diphenhydramine, Haloperidol, Haldol) is not absorbed from the skin of normal volunteers so cannot be effective against nausea. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 2012;43:375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stuart‐Harris 1983 {published data only}

- Stuart-Harris R, Buckman R, Starke I, Wiltshaw E. Chlorpromazine, placebo and droperidol in the treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with cisplatin therapy. Postgraduate Medical Journal 1983;59:500-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thangathurai 2010 {published data only}

- Thangathurai D, Roffey P. Usefulness of droperidol as an anti-emetic in terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine 2010;13(8):939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tramer 1999 {published data only}

- Tramer MR, Walder B. Efficacy and adverse effects of prophylactic antiemetics during patient-controlled analgesia therapy: a quantitative systematic review. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1999;88:1354-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

White 1992 {published data only}

- White RM, Myers EM, Ashayeri E, Gumbs RV, Pressoir R. Induction chemotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer: modification of response to chemotherapy by antiemetics. American Journal of Clinical Oncology 1992;15(1):45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yang 2011 {published data only}

- Yang LPH. Abiraterone acetate: in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Drugs 2011;71(15):2067-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bentley 2001

- Bentley A, Boyd K. Use of clinical pictures in the management of nausea and vomiting. Palliative Medicine 2001;15:247-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Carlisle 2006

- Carlisle J, Stevenson CA. Drugs for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004125.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davis 2010

- Davis MP, Hallerberg G. A systematic review of the treatment of nausea and/or vomiting in cancer unrelated to chemotherapy or radiation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2010;39(4):756-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Edmonds 2001

- Edmonds P, Karlsen S, Khan S, Addington-Hall J. A comparison of the palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer. Palliative Medicine 2001;15:287-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Food and Drug Administration 2001

- Important drug warning. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm173778.htm 4 Dec 2001.

Glare 2004

- Glare P, Pereira G, Kristjanson L, Stockler M, Tattersall M. Systematic review of the efficacy of antiemetics in the treatment of nausea in patients with far-advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer 2004;12:432-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grande 2000

- Grande GE, Todd CJ. Why are trials in palliative care so difficult? Palliative Medicine 2000;14(1):69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Habib 2008

- Habib AS, Gan TJ. Pro: the Food and Drug Administration black box warning on droperidol is not justified. Anesthesia and Analgesia 2008;106:1414-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hadley 2009

- Hadley G, Derry S, Moore RA, Wee B. Can observational studies provide a realistic alternative to randomised controlled trials in palliative care? Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy 2009;23(2):106-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hirst 2001

- Hirst A, Sloan R. Benzodiazepines and related drugs for insomnia in palliative care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003346] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996

- Jadad AR, Moore A, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials 1996;17(1):1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kao 2003

- Kao LW, Kirk MA, Evers SJ, Rosenfeld SH. Droperidol, QT prolongation, and sudden death: what is the evidence? Annals of Emergency Medicine 2003;41(4):546-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klinkenberg 2004

- Klinkenberg M, Willems DL, Wal G, Deeg DJH. Symptom burden in the last week of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2004;27:5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ludwin 2008

- Ludwin DB, Shafer SL. Con: the black box warning on droperidol should not be removed (but should be clarified!). Anesthesia and Analgesia 2008;106:1418-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mannix 2004

- Mannix KA. Palliation of nausea and vomiting. In: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Martindale 2009

- Martindale. The complete drug reference. www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/martindale/current 2009 (accessed 3 February 2010).

McKeage 2006

- McKeage K, Simpson D, Wagstaff AJ. Intravenous droperidol: a review of its use in the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Drugs 2006;66(16):2123-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MHRA 2001

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Discontinuation of Droleptan tablets, suspension and injection (droperidol). http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/Safetywarningsalertsandrecalls/Safetywarningsandmessagesformedicines/CON019548 11 January 2001.

MHRA 2008

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Marketing authorisations granted in January 2008. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/l-reg/documents/licensing/con014139.pdf.

Nuttall 2007

- Nuttall GA, Eckerman KM, Jacob KA, Pawlaski EM, Wigersma SK, Shirk Marienau ME, et al. Does low-dose droperidol administration increase the risk of drug-induced QT prolongation and Torsade de Pointes in the general surgical population? Anesthesiology 2007;107:531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Perkins 2009

- Perkins P, Dorman S. Haloperidol for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006271.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rhodes 2001

- Rhodes VA, McDaniel RW. Nausea, vomiting and retching: complex problems in palliative care. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2001;51:232-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Twycross 1998

- Twycross R, Back I. Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. European Journal of Palliative Care 1998;5:39-45. [Google Scholar]

Wee 2008

- Wee B, Hadley G, Derry S. How useful are systematic reviews for informing palliative care practice? Survey of 25 Cochrane systematic reviews. BMC Palliative Care 2008;7:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Dorman 2010

- Dorman S, Perkins P. Droperidol for treatment of nausea and vomiting in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006938.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]