Abstract

Pancreatic islet β cells secrete insulin in response to nutrient secretagogues, like glucose, dependent on calcium influx and nutrient metabolism. One of the most intriguing qualities of β cells is their ability to use metabolism to amplify the amount of secreted insulin independent of further alterations in intracellular calcium. Many years studying this amplifying process have shaped our current understanding of β cell stimulus-secretion coupling; yet, the exact mechanisms of amplification have been elusive. Recent studies utilizing metabolomics, computational modeling, and animal models have progressed our understanding of the metabolic amplifying pathway of insulin secretion from the β cell. New approaches will be discussed which offer in-roads to a more complete model of β cell function. The development of β cell therapeutics may be aided by such a model, facilitating the targeting of aspects of the metabolic amplifying pathway which are unique to the β cell.

Keywords: pancreatic islet beta cells, cell signaling, glucose sensing, amplifying pathway, biphasic insulin secretion, metabolomics

Introduction

Many recent publications in the pancreatic islet field have progressed our understanding of the glucose-mediated triggering and amplifying pathways of insulin secretion from β cells. Even so, there is still a significant need to unravel the complicated interplay of signaling events mediated by second messengers, metabolites, and post-translational modifications underlying the intriguing regulation of nutrient-induced insulin secretion. In-depth reviews of β cell function have been published recently, including updated perspectives on the genetics of diabetes and the role of the β cell (Ashcroft & Rorsman, 2012); focused analysis of the mechanisms of glucose-induced insulin secretion (Ferdaoussi & MacDonald, 2017; Komatsu, M., et al., 2013); metabolic signaling (Nicholls, 2016; Prentki, et al., 2013; Rutter, et al., 2015); and the roles of islet architecture and β cell heterogeneity (Roscioni, et al., 2016). Here we review some of the recent advances in our understanding of glucose-mediated amplification of insulin secretion from β cells with the aim to highlight established mediators and the potential for therapeutic targeting.

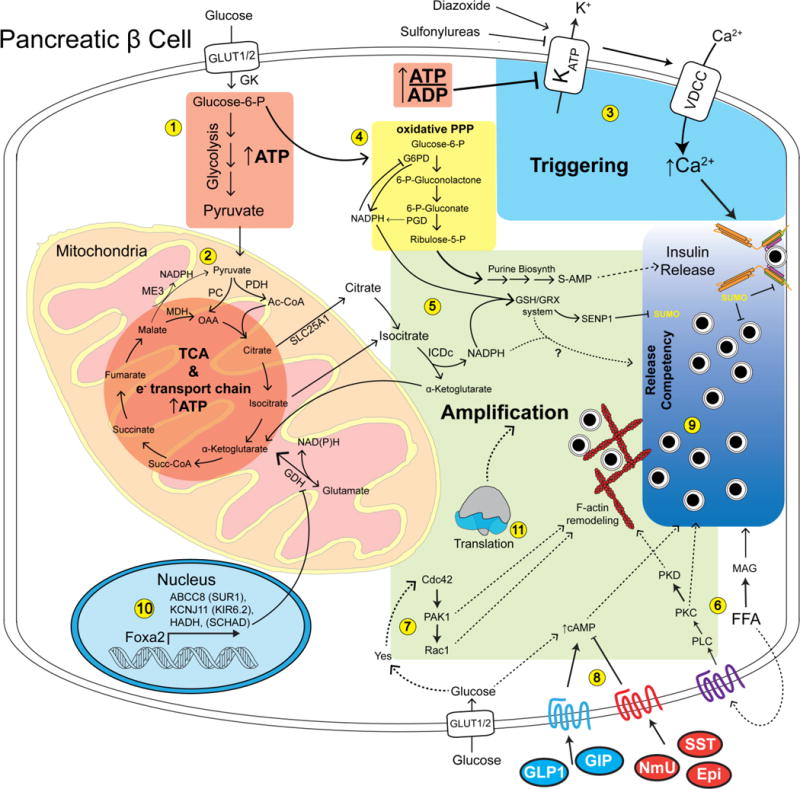

Pancreatic islet β cells secrete insulin in a biphasic manner in response to glucose stimulation. Glucose enters the β cell through GLUT1 (GLUT2 in rodents) and its rapid metabolism yields an increased ratio of ATP to ADP concentration within the first minute of stimulation (Civelek, et al., 1996) (Figure 1, #1). As a result, ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels close increasing membrane resistance, causing depolarization and opening of voltage-dependent calcium channels and sodium channels (Ashcroft & Rorsman, 2012) (Figure 1, #3). Subsequent calcium influx is sensed by multiple calcium-binding proteins and triggers insulin granule exocytosis (Cook, et al., 1984; Rorsman, et al., 1988; Satin & Cook, 1985). This stimulus-secretion coupling pathway results in a rapid and robust spike of insulin secretion called ‘first-phase’, which occurs over ~5–10 min after square-wave glucose stimulation. Insulin granules secreted during first-phase are thought to be comprised of both a ‘readily releasable pool’ (RRP) as well as ‘newcomer’ granules. The RRP is derived from insulin granules pre-docked/juxtaposed within 100–200 nm of the plasma membrane (Daniel, et al., 1999; Rorsman & Renstrom, 2003). Newcomer granules are recruited from deeper within the cell and fuse within 50 ms upon arriving at the plasma membrane (Nagamatsu, et al., 2006; Ohara-Imaizumi, et al., 2007). After the first-phase peak, the insulin release rate drops, but is sustained in the ‘second-phase’ which persists until euglycemia is restored (Rorsman & Renstrom, 2003).

Fig. 1. Overview of glucose-stimulated triggering and amplifying pathways in the β cell.

1) Glucose enters the β cell through the GLUT1 glucose transporter (GLUT2 in rodents) and is phosphorylated by glucokinase (GK) to yield glucose-6-phosphate. ~90% of glucose-6-phosphate enters glycolysis yielding ATP and pyruvate. 2) Pyruvate is transported into the mitochondria where about half is metabolized by pyruvate carboxylate (PC) to regenerate oxaloacetic acid (OAA) for the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA). The rest of the pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and condenses with OAA yielding citrate. The TCA cycle generates reducing equivalents, driving the electron transport chain and ATP synthesis. 3) The relative increase in the ratio of ATP to ADP driven by glycolysis and the TCA cycle lead to closure of the KATP channel. In turn, this activates voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCC) to allow the influx of calcium that constitutes the triggering pathway required for insulin secretion. Additional glucose-dependent metabolites derived from the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (4) and export of mitochondrial intermediates such as isocitrate (5) lead to increases in NADPH and reduced glutathione. Glucose stimulates generation of free fatty acids, which can serve as precursors to monoacylglycerol (MAG) which can enhance granule priming (6). Glucose entry also results in the activation of the kinase Yes and the small GTPase Cdc42 pathway (7), allowing proper metering of secretion via actin dynamics. The β cell response is further modulated by positive and negative signaling via cell-surface receptors (8), influencing the amount of insulin exocytosis in response to the triggering and amplifying pathways. These pathways cooperate with deSUMOylation- and SNARE-dependent processes which through amplification increases the sensitivity of insulin granules to the triggering calcium influx (i.e. release competency (9)). Proper gene transcription (10) and translation (11) are also required for normal operation of the amplifying pathway, although not much is known about the mechanisms.

Second-phase insulin secretion requires the recruitment of granules from intracellular storage pools to the plasma membrane. These are comprised mostly of ‘newcomer’ granules (Ohara-Imaizumi, et al., 2007) and this process involves reorganization of the cortical filamentous actin (F-actin) cytoskeleton (Kalwat & Thurmond, 2013; Mourad, et al., 2010; Wang, Z. & Thurmond, 2009). In type 2 diabetes there is a loss of both first and second-phase insulin secretion (Nesher & Cerasi, 2002). As insulin secretion can occur over the course of hours, the second-phase accounts for the majority of insulin released when compared to the first-phase. More specifically, first-phase represents ~15% of the total insulin secretion within a 1 hour stimulation (Henquin, et al., 2015), with second-phase accounting for the remainder.

The ability of glucose to elicit an increase in cytosolic [Ca2+] causing insulin secretion is referred to as the triggering pathway (Henquin, 2000). The triggering pathway (previously referred to as the KATP-dependent pathway) can be studied using non-nutrient secretagogues such as KCl, which depolarize the β cell independently of changes in metabolism, opening voltage-dependent calcium channels, allowing calcium influx, and leading to the fusion of insulin granules with the plasma membrane and exocytosis of insulin (Henquin, 2011) (Figure 1, #3). In contrast to membrane depolarization by KCl, metabolism of glucose generates additional signals which augment the amount of insulin secreted in response to the triggering calcium influx. This second pathway, initially described 25 years ago and referred to as the KATP-independent pathway (Gembal, et al., 1992; Sato, Y., et al., 1992) is now known as the metabolic amplifying pathway (Henquin, 2011). The amplifying pathway depends on the initial triggering signal in order to affect insulin secretion. Essentially, the amplifying pathway results in an increased sensitivity of insulin secretory granules to the given triggering calcium influx; in other words, the granules have increased ‘release competency’ (Figure 1, #9). The triggering and amplifying pathways have been associated with first- and second-phase insulin secretion, respectively, although there is sufficient evidence which demonstrates that amplification is involved in both phases of insulin secretion (Mourad, et al., 2010, 2011). Triggering and amplification can be deconvolved in vitro using different drugs aimed at modulating the status of the KATP channel (Aguilar-Bryan & Bryan, 1999). The KATP channel is a heterooctamer comprised of four core pore-forming Kir6.2 subunits and four outer SUR1 regulatory subunits (Li, et al., 2017; Martin, et al., 2017). Diazoxide binds to the SUR1 subunit of the KATP channel, opening the channel even in the presence of elevated ATP concentration (Shyng, et al., 1997). In the this paradigm, KATP channels are held open by diazoxide, depolarizing levels of KCl are added to cause the triggering calcium influx, and further addition of glucose elicits the amplifying pathway (Figure 1) (Gembal, et al., 1992). Another method uses a high concentration of sulfonylurea, closing all the KATP channels (causing triggering), followed by glucose stimulation to reveal the amplifying pathway. Diazoxide or sulfonylureas clamp the β cell KATP channels (open or closed, respectively) such that they are not affected by glucose-induced changes in the ATP/ADP ratio; therefore, further changes in insulin secretion in response to glucose are independent of changes in [Ca2+]c (Henquin, 2000). The amplifying pathway can be observed in both SUR1 (ABCC8) knockout (Nenquin, et al., 2004) and Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) knockout islets (Miki, et al., 1998; Ravier, et al., 2009). Both of these models are essentially knockouts of the KATP channel, causing constant depolarization of the β cell and the results agree with observations made using pharmacological modulation of the KATP channel. These strategies are important for elucidating the factors and signaling events underlying the amplification of insulin secretion. While it is well-accepted that triggering is the result of calcium influx, the exact mechanisms behind the amplifying pathway are not as clear-cut. Recent studies reviewed herein have begun to elucidate the involvement of specific proteins, metabolites and associated pathways.

Physiological amplification of insulin secretion requires β cell nutrient metabolism (Gembal, et al., 1992; Sato, Y., et al., 1992). The first proposed mediators were changes in the cytosolic ATP/ADP (Anello, et al., 2001; Gembal, et al., 1993; Urban & Panten, 2005) and GTP/GDP (Detimary, et al., 1996; Komatsu, Mitsuhisa, et al., 1998) ratios (Table 1). A role of cytosolic glutamate has also been proposed (Maechler & Wollheim, 1999) and refuted (Bertrand, et al., 2002; MacDonald, M. J. & Fahien, 2000). However, increased β cell glutamate is now known not to elicit the amplifying pathway on its own and was recently shown to mediate amplification of GSIS in an incretin/cAMP-specific setting (Gheni, et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Modulators of the Amplifying Pathway. A summary of the molecules discussed in this review is listed and their impacts on the b cell amplifying pathway are categorized as positive, neutral, negative, or other. The listed positive modulators enhance insulin secretion or are required amplificationwhile the negativemodulators tend to suppress secretion. Neutral factors have either been shown to not be required for secretion or unable to elicit a response independently. ‘Other’ modulators could have both positive and negative impacts in different contexts.

| Amplifying Pathway Function | Molecule | Category | Mechanisms/Actions | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | ATP | Metabolite | KATP channel inhibition | (Anello, et al., 2001; Detimary, et al., 1996; Gembal, et al., 1993; Pizarro-Delgado, et al., 2015; Urban & Panten, 2005) |

| Positive | GTP | Metabolite | Small GTPase activation Mitochondrial glutamate dehydrogenase inhibition | (Detimary, et al., 1996; Komatsu, M., et al., 1993; Komatsu, Mitsuhisa, et al., 1998) |

| Positive | NADH | Metabolite | Required in general, but insufficient to elicit exocytosis on its own | (Eto, 1999; Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015) |

| Positive | NADPH | Metabolite | Reducing power for glutaredoxin system, Sufficient to elicit exocytosis in patch clamp infusions | (Goehring, et al., 2011; Gooding, et al., 2015; Hasan, et al., 2015; Ivarsson, et al., 2005; Spegel, et al., 2013) |

| Positive | Glutamate | Metabolite | Glutamate dehydrogenase substrate, GLP-1-induced import into insulin granules | (Gheni, et al., 2014) |

| Positive | Malonyl-CoA | Metabolite | Inhibition of fatty acid β oxidation | (El-Azzouny, et al., 2014; Guay, et al., 2013; Lorenz, et al., 2013) |

| Positive | Isocitrate | Metabolite | Sufficient to elicit exocytosis in patch clamp infusions | (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015; Gooding, et al., 2015) |

| Positive | Adenylosuccinate (S-AMP) | Metabolite | Sufficient to elicit exocytosis in patch clamp infusions | (Gooding, et al., 2015) |

| Positive | Pyruvate cycles (citrate, malate, PEP) | Metabolite | Production of intermediates for distal effector metabolites (e.g. NADPH) | (Huang & Joseph, 2014; Jensen, et al., 2008; Prentki, et al., 2013) |

| Positive | Fatty acids/acyl-CoAs | Metabolite, Lipid | (Deeney, 2000; Huang & Joseph, 2014; Prentki, et al., 1992) | |

| Positive | Monoacylglycerol | Metabolite, Lipid | Binds Munc13 to enhance insulin granule priming | (Zhao, et al., 2014) |

| Positive | Glutathione (reduced) | Metabolite, Peptide | Sufficient to elicit exocytosis in patch clamp infusions | (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015; Ivarsson, et al., 2005; Liu, et al., 2015; Takahashi, et al., 2014) |

| Positive/Neutral | Extracellular amino acids | Metabolite | T1R1/T1R3 Taste receptor signaling | (Wauson, et al., 2012; Wauson, et al., 2015) |

| Positive | Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) | Protein, Mitochondrial | Inhibition with epigallocatechin gallate blunts amplification by glucose. Mice with Beta cell-specific deletion of GLDH lack amplifying pathway. |

(Carobbio, et al., 2009; Leite, et al., 2016; Vetterli, et al., 2016; Vetterli, et al., 2012) |

| Positive | SENP1 | Protein | Removes SUMOylation | (Dai, et al., 2011; Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015) |

| Other | SUMO | Protein | Small ubiquitin-like protein that is covalently conjugated to target proteins like synaptotagmin VII, tomosyn 2, and RhoGDI. | (Cao, et al., 2014; Dai, et al., 2011; Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015; Ferdaoussi, et al., 2017) |

| Positive | Cytochrome c (reduced) | Protein, Mitochondrial | Serves as an electron carrier in the electron transport chain | (Jung, et al., 2011) |

| Positive | Mitochondrial malic enzyme (ME3) | Protein, Mitochondrial | Generation of pyruvate and NADPH from malate in mitochondria. Possible catalytic-independent role. | (Hasan, et al., 2015) |

| Other | ZMP | Metabolite | Purine synthesis intermediate, an S-AMP precursor | (Lorenz, et al., 2013) |

| Positive | GLP-1 | Peptide Hormone | ↑cAMP, other Amplifies secretion in response to stimuli Has cAMP-independent effects on TRMP4/5 via PKC | (Campbell & Drucker, 2013; Shigeto, et al., 2015) |

| Positive | Protein Synthesis | Perturbation with CHX, 2h Suggests requirement for maintenance of proteins with short half-lives | (Garcia-Barrado, et al., 2001) | |

| Positive | Forskolin | Pharmacological, Natural Product | Adenylylcyclase activation Some KCl-dependence, but more glucose | (Gembal, et al., 1993) |

| Positive | cAMP (cell-permeable analogs) | Pharmacological | PKA and Epac2 activation Some KCl-dependence, but mostly glucose-dependent | (Gembal, et al., 1993) |

| Positive | ARA290 | Pharmacological, Natural Product | non-hematopoietic erythropoietin analog, IRR activation Selective augmentation of amplifying pathway, H89-sensitive | (Muller, C., et al., 2015) |

| Positive | Imeglimin | Pharmacological | Activates oxidative phosphorylation | (Perry, et al., 2016) |

| Neutral | Cytosolic malic enzyme (ME1) | Protein, Cytosolic | (Brown, et al., 2009; Heart, et al., 2009; MacDonald & Marshall, 2001; Ronnebaum, et al., 2008) | |

| Neutral | Mitochondrial malic enzyme (ME2) | Protein, Mitochondrial | (Brown, et al., 2009; Ronnebaum, et al., 2008) | |

| Neutral | Phosphoenolpyruvate | Metabolic | Insufficient to elicit exocytosis in patch clamp infusions | (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015) |

| Other | Cytosolic isocitrate dehydrogenase (cIDH) | Protein, Cytosolic | Converts isocitrate and NADHP to α-ketoglutarate and NADPH | (Ferdaoussi et al., 2015; Guay, et al., 2013) |

| Other | Foxa2 (Hnf3b) | Protein, Transcription Factor | Activates expression of SUR1, KIR6.2, and HADH | (Lantz, et al., 2004) |

| Other | HADH | Protein | short-chain L-3-hydroxyacylcoenzyme A dehydrogenase, Foxa2-target | (Lantz, et al., 2004) |

| Other | Liraglutide | Pharmacological, Engineered | GLP-1R agonist Possible long-term detrimental effects on beta cells | (Abdulreda, et al., 2016) |

| Neutral | Arginine vasopressin | Peptide Hormone | IP3 generation | (Gembal, et al., 1993) |

| Other | Phorbol Esters (PMA, TPA) | Pharmacological | PKC activation potentiates GSIS, PKC is not required specifically for GSIS. Possible role in vivo through parasympathetic Ach signaling in islets. | (Carpenter, et al., 2003; Gembal, et al., 1993; Gilon & Henquin, 2001) |

| Negative | Sympathetic nervous system | Neural control | (Straub & Sharp, 2012; Thorens, 2014) | |

| Negative | Ghrelin | Peptide Hormone | Activates δ cell somatostatin secretion and α cell glucagon secretion, suppresses insulin secretion | (Adriaenssens, et al., 2016; Chuang, et al., 2011; DiGruccio, et al., 2016; Muller, T. D., et al., 2015) |

| Negative | Somatostatin | Peptide Hormone | Gαi-dependent suppression of insulin/glucagon secretion | (Kailey, et al., 2012) |

| Negative | Neuromedin U | Peptide Hormone | (Alfa, et al., 2015) | |

| Negative | LKB1 | Protein | Nutrient-sensing, phosphorylation of AMPK, SADK, SIK2 | (Swisa, et al., 2015) |

| Negative | Tomosyn-2 | Protein, Plasma membrane | Inhibits amplifying pathway exocytosis | (Bhatnagar, et al., 2011; Zhang, et al., 2006) |

Candidate signaling molecules/pathways with evidence supporting a role in metabolic amplification include, but are not limited to, acyl-CoAs (e.g., protein acylation) (Liang & Matschinsky, 1991), mitochondrial citrate/isocitrate production (Panten & Rustenbeck, 2008) (Figure 1, #5), the redox state of mitochondrial cytochrome C (Jung, et al., 2011; Rountree, et al., 2014), pyruvate cycling and TCA cycle intermediates (anaplerosis) (Alves, et al., 2015; Jensen, et al., 2008; Lu, et al., 2002; MacDonald, M. J., et al., 2005; Ronnebaum, et al., 2006) (Figure 1, #2), upstream and downstream signaling in the glucose-activated Cdc42 pathway (Wang, Z. & Thurmond, 2010; Yoder, et al., 2014), sentrin/SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs) (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015), the SNARE-protein regulator tomosyn-2 (Bhatnagar, et al., 2011), and generation of NADPH and reduced glutathione (GSH) (Ivarsson, et al., 2005).

1. Linking β cell signaling and metabolomics to the amplifying pathway

The disruption of metabolic amplification in vivo may play an integral role in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. For example, β cells from individuals with type 2 diabetes have impaired glucose-induced mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization (Gerencser, 2015). This defect was rescued by supplying mitochondrial metabolic intermediates (e.g. methyl-succinate/α-ketoisocaproate), indicating the defect(s) lie upstream of glucose entry into the TCA cycle. The mitochondrial transcriptome has also been shown to be altered by treating human islets from normal donors with diabetes-like conditions (Brun, et al., 2015). Because nutrients are required for amplification of insulin secretion, the involvement of specific metabolites in the process is expected. Since the first studies investigating this idea nearly 20 years ago (Sato, Yoshihiko, et al., 1998), there have been multiple metabolomics studies treating β cells with glucose and other stimuli at different time points to ascertain which metabolites are altered during GSIS (see Table 1). Additionally, the use of patch clamp methods to ‘inject’ candidate metabolic mediators into β cells has offered insight into which metabolic steps may be sufficient to elicit amplification of insulin exocytosis.

1.1 Positive regulators

1.1.1 NADPH

The well-studied sources of NADPH in cells are the pentose phosphate pathway and isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDc) in the cytosol, as well as several mitochondrial-dependent enzymes: NADP-linked isocitrate dehydrogenase, NADP-linked glutamate dehydrogenase, NADP-linked malic enzyme, nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase, and NADH kinase (Gray, et al., 2012; Pollak, et al., 2007). An estimated 90% of glucose in the β cell enters glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism, leaving ≤10% to enter the pentose phosphate pathway (Schuit, et al., 1997). Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is the first enzyme in the pentose phosphate pathway and converts glucose-6-phosphate and NADP to 6-phosphogluconolactone and NADPH (Figure 1, #4). 6-phosphogluconolactone is converted to 6-phosphogluconate by gluconolactonase. The third enzyme in the pathway, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, then generates a second NADPH by converting 6-phosphogluconate to ribulose-5-phosphate. The rest of the pentose phosphate pathway is non-oxidative and generates no additional NADPH, but it serves as an important source of metabolic intermediates for purine nucleotide synthesis such as ribose-5-phosphate. Increased extracellular glucose raises the NADPH/NADP ratio and ribose-5-phosphate concentration, indicating that β cells have an active and responsive pentose phosphate pathway (Gooding, et al., 2015; Spegel, et al., 2013). Inhibition of G6PD by acute treatment with dehydroepiandosterone blocked GSIS and production of ribose-5-phosphate and GSH (Spegel, et al., 2013). G6PD deficiencies have been linked to impaired fasting glucose (Santana, et al., 2014) and human islets depleted of 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase by RNA interference had blunted GSIS (Goehring, et al., 2011). It has also been argued that the pentose phosphate pathway does not contribute to β cell NADPH production (Prentki, et al., 2013; Schuit, et al., 1997). Perhaps the reasons for different findings depend on differences between species and cell lines, glucose stimulation durations, metabolomic analysis methods, and the heterogeneous nature of islet cell type composition.

There is also controversy regarding the effects of elevated or suppressed G6PD protein levels in response to chronic high/low glucose. In one study, G6PD was found to be up-regulated in islets from diabetic rats (Lee, et al., 2011); subsequent experiments forcing over-expression of G6PD in islets inhibited GSIS. Alternatively, other work showed that hyperglycemic conditions suppressed G6PD protein levels in mouse and human islets and GSIS was suppressed in islets from G6PD-deficient mice or by G6PD knockdown in MIN6 cells (Zhang, Z., et al., 2010). Therefore, it seems that optimal amounts of G6PD are required for efficient GSIS, but highly elevated or suppressed expression of G6PD negatively impacts insulin secretion. Whether the effects on insulin secretion are attributable to NADPH and/or GSH production in these conditions requires further investigation.

Additional investigation of the pentose phosphate pathway in β cells may also uncover previously unknown regulators of the amplifying pathway. To that end, novel techniques to measure the flux of NAPDH in compartment-specific (Lewis, et al., 2014) and pathway-specific (Fan, et al., 2014) manners are enticing to adapt and integrate into analyses of β cells to ascertain sites of NADPH production and its actions in the amplifying pathway. Recent approaches using genetically-encoded Apollo-NADP+ live-cell imaging sensors will also be useful (Cameron, et al., 2016), for example to track changes in NADPH/NADP+ ratios in the heterogeneous cell population of the islet. NADPH is a metabolic coupler thought to require the presence of cAMP and ATP to affect insulin secretion (Ivarsson, et al., 2005), but NADPH can also activate exocytosis in the absence of cAMP and under low ATP concentrations (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015). Clearly, the β cell coordinates the production of and response to multiple mitochondria- and cytosol-derived metabolic signals that likely work in concert to elicit the glucose-mediated amplifying pathway.

Recent work from the MacDonald and Newgard labs has demonstrated linkage between the metabolism of glucose in the pentose phosphate pathway and the regulation of insulin secretion (Gooding, et al., 2015). Glucose metabolism leads to the generation of a purine nucleotide intermediate, adenylosuccinate (S-AMP) which, through unknown mechanisms, requires the deSUMOylating enzyme SENP1 to activate the amplifying pathway. Provision of S-AMP intracellularly via patch-clamp was powerful enough to induce exocytosis in β cells from type 2 diabetic donors. If it becomes possible to modify S-AMP with specific radiolabeling or with click chemistry in a cell-permeable form, perhaps its metabolic fate or cellular target can be elucidated. The same groups also showed that SENP1 is critical for regulated exocytosis of insulin granules (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015). The authors’ previous work supports a model where synaptotagmin VII is SUMOylated, which reduces its activity in Ca2+ sensing and exocytosis initiation (Dai, et al., 2011). After acute glucose stimulation, SENP1 deSUMOylates synaptotagmin VII (Dai, et al., 2011), tomosyn-1 (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2017), and likely other important β cell substrates to permit efficient insulin granule exocytosis. How S-AMP fits into this model has yet to be determined.

A recent review by Gooding, et al. gives a detailed account of over 60 metabolites and their statuses in both first- and second-phase insulin secretion (Gooding, et al., 2016). The authors discuss an isocitrate-NADPH-GSH pathway as a metabolic link to GSIS (Figure 1, #5). This idea fits well with the need for reducing equivalents, such as reduced cytochrome c (Jung, et al., 2011) and GSH (Ivarsson, et al., 2005), and links nicely with GSH-mediated activation of SENP1 (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015). Although these findings are very promising, a separate group suggested that cytosolic ICD negatively regulates the amplifying pathway of insulin secretion (Guay, et al., 2013). The reason for the discrepant results is unclear, but generation of β cell-specific knockout animals or CRISPR/Cas9-based β cell lines combined with rescue strategies might provide an answer. Additionally, other researchers have proposed alternatively that cytosolic acetyl-CoA accumulates causing protein acetylation to drive the pathway as opposed to isocitrate-NADPH (Panten, et al., 2016). However, while such a mechanism would require ATP citrate lyase activity, multiple findings suggest ATP citrate lyase is not required for insulin secretion (El Azzouny, et al., 2016; Joseph, et al., 2007; MacDonald, M. J., et al., 2007). Using the diazoxide paradigm, islets from SENP1 knockout mice have impaired GSIS due to defects specifically in the amplifying pathway, but they appear to retain approximately half of their response suggesting the existence of either genetic compensation or other intact parallel pathways (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2015). It is also possible that GSH promotes the amplifying pathway through other mechanisms in addition to SENP1, although this remains an open question. Glucose induces production of reduced glutathione in the mitochondria and use of the diazoxide paradigm showed this is likely independent of the triggering pathway (e.g. calcium influx) (Liu, et al., 2015; Takahashi, H. K., et al., 2014). Together these data support the notion that multiple pathways cooperate to amplify insulin secretion in response to glucose; NADPH-GSH and SENP1/deSUMOylation are each contributors.

It is also worth noting inhibition of protein synthesis with cycloheximide for as short at 2 h disrupted GSIS mainly via the amplifying pathway, even though glucose oxidation and NAD(P)H production were relatively intact (Garcia-Barrado, et al., 2001) (Figure 1, #11). While specific measurements of NADPH under these conditions are needed for confirmation, the results of Garcia-Barrado, et al. support the existence of translation monitors or short-lived protein mediators of the amplifying pathway which lie downstream of the NADPH signal. This idea would be bolstered if provision of NADPH by patch-clamp is unable to bypass cycloheximide inhibition of amplification, although this has not been tested. Some of these unidentified short-lived proteins may turn out to be regulators of or members of the ‘late effector’ group proposed by Prentki and colleagues (Prentki, et al., 2013).

1.1.2 Additional glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolites

Glucose flux through glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and the electron transport chain are all critical for generation of ATP and many metabolic intermediates which participate in mitochondrial-cytosolic shuttles. Generation of pyruvate and its transport into the mitochondria are required for the glucose-induced amplifying pathway (Patterson, et al., 2014), likely because pyruvate transport is required for glucose-induced increases in ATP, GTP, and NADPH concentrations in the β cell. The malate-aspartate and glycerol phosphate shuttles are responsible for transferring reducing equivalents (NADH) to the mitochondria for ATP generation. It has been demonstrated utilizing the diazoxide paradigm that β cells require at least the malate-aspartate or the glycerol phosphate shuttles, otherwise both triggering and amplifying pathways are impaired (Eto, 1999). The malate-aspartate shuttle is at least one pathway which underlies differences in glucose responses between β cells and their α cell counterparts. Treatment of mouse islets with phenylsuccinate, which blocks the mitochondrial α-ketoglutarate carrier, dramatically enhanced glucose-induced suppression of glucagon secretion, while leaving insulin secretion relatively intact (Stamenkovic, et al., 2015). The lack of effect of phenylsuccinate on GSIS suggests that all else being equal, the malate-aspartate shuttle on its own may not be critical for amplification. Therefore, β cells likely make use of the glycerol phosphate shuttle in conjunction with the malate-aspartate shuttle, while α cells do not utilize the glycerol phosphate shuttle. The malic enzymes (ME1; cytosolic, ME2 and ME3; mitochondrial), which convert malate and NAD(P)+ to pyruvate and NAD(P)H, have been investigated for functions in GSIS. There is evidence to suggest that neither ME1 nor ME2 are required for GSIS. Mice deficient in both ME1 and cytosolic glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase have normal islet GSIS (MacDonald, Michael J. & Marshall, 2001) and adenoviral knockdown of either ME1 or ME2 in rat islets had no effect on GSIS (Ronnebaum, et al., 2008). More recently, ME3, in contrast to ME1 and ME2, was found to be important in the β cell for generation of pyruvate and NADPH from malate in the mitochondria (Hasan, et al., 2015). Because ME3 enzymatic activity was found to be low in β cells, ME3 has been proposed to exert some of its actions though a non-catalytic mechanism, but this remains to be tested.

An interesting metabolite highly induced by acute glucose stimulation is 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (ZMP or AICA-ribonucleotide; not to be confused with AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside) which is converted to ZMP in cells) (Lorenz, et al., 2013). ZMP is synthesized as part of the nucleotide biosynthesis pathway using molecules generated in the pentose phosphate pathway. Treatment of INS1 β cells with 250 μM AICAR, which activates AMP kinase, blunts GSIS through multiple mechanisms (ElAzzouny, et al., 2015). Because the concentration of ZMP in cells treated with such high concentrations of AICAR is 100-fold over the endogenously produced concentrations in response to glucose stimulation, it is likely that AICAR-activated AMP kinase is responsible for the effects. Lower doses of AICAR (25 μM) were shown to only increase endogenous ZMP concentrations ~4-fold and had no impact on insulin secretion from INS1 cells except a slight inhibition after 40–60 min of glucose stimulation (Lorenz, et al., 2013). However, it is possible that glucose-induced physiological concentrations of ZMP serve as a precursor for S-AMP to facilitate insulin secretion (Gooding, et al., 2015).

The nucleotide ATP itself is known to signal extracellularly in addition to its intracellular roles and can contribute either as a mediator or a requisite molecule to in both triggering and amplification. ATP clearly regulates the triggering pathway through both [Ca2+]i-dependent and [Ca2+]i-independent mechanisms (Eliasson, et al., 1997; Takahashi, N., et al., 1999). Additionally, recent work utilizing an ‘islet permeabilized model’ points to a role for ATP in the amplifying pathway during biphasic GSIS (Pizarro-Delgado, et al., 2015). However, Prentki and colleagues (Prentki, et al., 2013) do point out a handful of studies where GSIS and ATP levels are dissociated (Doliba, et al., 2007) or where ATP is unchanged in the face of robust GSIS (Ghosh, et al., 1991).

1.1.3 Lipid signaling

The roles for lipids in β cell metabolism and insulin secretion have been reviewed extensively (Keane & Newsholme, 2014; Newsholme, et al., 2014; Prentki, et al., 2013). In vivo the islet responds to a variety of nutrients in the blood including sugars, amino acids, and lipids, but ex vivo the islet β cell still exhibits the metabolic amplifying pathway in response to glucose as the sole nutrient. A brief overview of the intersections of β cell lipid signaling specifically relating to glucose-stimulated amplification will be discussed in this section. Using INS1 832/13 rat β cells to monitor the cellular metabolome, Huang & Joseph found, in agreement with other studies, that glucose induces increased concentrations of many metabolites including lipid intermediates like long chain-CoAs (Huang & Joseph, 2014). Glucose metabolism in the β cell fuels production of malonyl-CoA (Lorenz, et al., 2013), which inhibits β-oxidation of fatty acids, compounding the impact of glucose on lipid signaling. Acetoacetate generated in the mitochondria and exported to the cytosol also promotes insulin secretion through the production of acetyl-CoA and other short chain acyl-CoAs (El Azzouny, et al., 2016; Macdonald, M. J., et al., 2008). The results of (El Azzouny, et al., 2016) also show that ATP citrate lyase is not required for insulin secretion, in agreement with several other studies (Joseph, et al., 2007; MacDonald, M. J., et al., 2007). Lipids generated or mobilized downstream of glucose stimulation can influence the metabolic amplifying pathway through intracellular targets (e.g. Munc13) or possibly by exiting the cell and activating receptor-mediated mechanisms of amplification (Figure 1, #6) (Mugabo, et al., 2017).

Stimulation of β cells with glucose alone induces changes in the concentrations of a variety of free fatty acids, including monoacylgycerol (MAG). MAG levels are regulated by lipases which are responsible for the final step in triacylglycerol catabolism (MAG → glycerol + fatty acid). Blocking the plasma membrane localized MAG lipase α/β-hydrolase domain-6 enhanced insulin secretion, suggesting MAG is a pro-secretory molecule (Zhao, et al., 2014). It is likely that MAG increases secretion through the amplifying pathway by binding directly to Munc13 (Zhao, et al., 2014), a protein required for proper insulin granule docking and priming during both phases of insulin secretion (Xie, et al., 2012). However, irreversible pharmacological inhibition of the cytosolic MAG lipase MGL, inhibited biphasic insulin secretion and both the triggering and amplifying pathways in rat islets, even though calcium influx was intact (Berdan, et al., 2016). Inhibition of MGL also reduced long chain acyl-CoAs, presumably because of reduced fatty acid availability. Because long chain acyl-CoAs signal to the β cell to enhance insulin secretion and glucose was the only nutrient secretagogue in these studies, the data support a model where glucose induces mobilization of intracellular fatty acids which likely participate in a combination of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) signaling, protein acylation, and direct effects on exocytosis. Maintaining proper concentrations of MAG in specific compartments is important since a build-up of MAG during MGL inhibition may contribute to the blunting of GSIS (Berdan, et al., 2016).

Fatty acids generated within the islet from long chain-CoAs (as described above) may also signal through GPCRs on the β cell surface (Figure 1, #6). The major receptors known thus far are GPR40, GPR41, GPR43, and GPR119. GPR40 is a long-chain fatty acid receptor which may enhance glucose-induced amplification of insulin secretion via IP3-Ca2+ and DAG-PKC pathways (Sakuma, et al., 2016), while GPR41 and GPR43 prefer short-chain fatty acids. GPR40−/− islets lost responses to external oleate stimulation, but their response to glucose alone was relatively unimpaired (Ferdaoussi, et al., 2012). This result argues that perhaps glucose-induced fatty acid mobilization does not lead to insulin secretion through β cell GPR40. Islets from GPR41 transgenic or knockout mice each have irregularly increased fasting basal insulin secretion which resulted in complete blunting of the insulin secretory stimulation index (Veprik, et al., 2016). GPR119 acts through a cAMP signaling pathway to amplify insulin secretion, similar to the incretin system. The targeting of some of these receptors to modulate the amplifying pathway for type 2 diabetes therapy will be discussed in section 4.2.

1.1.4 Intersection of small GTPases and cytoskeletal signaling with triggering and amplifying pathways

The microtubule and actin cytoskeletons have been investigated as regulators of the triggering and amplifying pathways, as well as biphasic secretion. Natural product drugs which either promote formation of or disrupt the F-actin cytoskeleton were found to potentiate biphasic secretion (Mourad, et al., 2010; Nevins & Thurmond, 2003; Thurmond, et al., 2003). Similar results were observed when disrupting or stabilizing microtubules (Mourad, et al., 2011). While pharmacological modulation of the cytoskeleton suggested that cytoskeletal dynamics may not underlie glucose-mediated amplification of insulin secretion, the cytoskeleton is critical for proper metering of insulin secretion. This is in agreement with the previously cited study of mitochondrial pyruvate transport (Patterson, et al., 2014); blockade of that pathway did not impair glucose-induced F-actin remodeling. This suggests that divergent glucose-dependent signals regulate metabolic amplifiers separately from cytoskeletal-regulated insulin release. A signaling cascade activated by glucose, leading to F-actin remodeling (Figure 1, #7), has been characterized involving: 1) the activation of the Src-family kinase Yes (Yoder, et al., 2014) as well as ARNO/Arf6 (Jayaram, et al., 2011), 2) signals leading to the activation of the small GTPase Cdc42 (Kepner, et al., 2011; Nevins & Thurmond, 2003, 2006), 3) subsequent activation of the kinase Pak1 (Wang, Z. & Thurmond, 2010), and 4) activation of Rac1 (Asahara, et al., 2013), as well as the Raf-MEK-ERK MAP kinase pathway (Kalwat, et al., 2013). Multiple nodes along this entire pathway have been shown to have positive roles in biphasic GSIS and the amplifying pathway. If their roles in cytoskeletal remodeling are not required for amplification, it is plausible that there is additional non-canonical signaling stemming from this pathway that intersects with amplifying factors. It is still unclear exactly what signals cause the proximal events of Yes and ARNO/Arf6 activation at ~1 minute after glucose stimulation. It is known that glucose stimulation and subsequent metabolism leads to rapid changes in the ATP/ADP ratio, beginning at ~30 seconds (Civelek, et al., 1996), so generation of glucose-derived effectors for these proteins is possible during the given time-frame. It is tempting to speculate that some of these signaling nodes may be acted upon by pathways already shown to be critical in the amplifying pathway, such as SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation or alternate GSH-dependent mechanism. In line with this idea, small GTPase regulators such as RhoGDI have been shown to be SUMOylated (Cao, et al., 2014). β cell NADPH-oxidase (which uses NADPH as a substrate), can be activated by small GTPases like Rac1 to influence reactive oxygen species production in response to stress (Kowluru, 2010). Additionally, exocytosis regulatory proteins synaptotagmin VII and tomosyn-1 have been shown to be SUMOylated, while the target-SNARE proteins syntaxin 1A and 4 are regulated by F-actin binding. Continued investigation of amplifying pathway effector metabolites/proteins on pathways that regulate cytoskeletal remodeling may lead to a more complete understanding of how the β cell tightly governs both triggering and amplifying pathways of insulin secretion.

1.2 Controversial regulatory pathways in glucose-induced amplification

Of the possible mediators of glucose-induced amplification of insulin secretion, many have been investigated and eliminated (Sato, Yoshihiko, et al., 1998). Certain molecules such as NADPH are clearly important, while the functions of other factors, such as cAMP, have been difficult to ascertain or assign within the amplifying pathway. Given that the major product of mitochondrial metabolism is ATP, ATP itself could possibly influence amplification aside from its role in triggering. Regarding mechanisms of ATP outside its action on the KATP channel, insulin granule pH lowering has been suggested as a potential function of the glucose-induced rise in ATP concentrations (Barg, et al., 2001). This decrease in pH was shown to help prime the granules for secretion, although other work suggests this pH change does not influence metabolic amplification of insulin secretion (Stiernet, et al., 2006).

While cAMP amplifies secretion, it has not been fully recognized in the past as a second-messenger specifically downstream of glucose in the amplifying pathway. Typically, cAMP is generated by adenylyl cyclases in response to Gαs-coupled GPCRs, such as GLP-1 receptor. However, recent studies of the adenylyl cyclase isoform ADCY5 show it is activated by glucose and not the Gαs-coupled GLP-1 receptor, leading to the idea that ADCY5-mediated cAMP generation is required for normal GSIS in human islets (Hodson, et al., 2014). Mechanisms proposed by Rutter, et al. for how this glucose-stimulated cAMP impacts secretion include activation of glucokinase, pyruvate carboxylase, and phosphofructokinase (Rutter, et al., 2015). Furthermore, findings from the Tengholm have lab have shown that glucose can induce cAMP oscillations beneath the plasma membrane (Tian, et al., 2012; Tian, et al., 2011) and this cAMP generation may be independent of glucose-induced increases in cytosolic calcium (Dyachok, et al., 2008). The phospholipase C and protein kinase C pathways are also coupled to GPCR activation, but likely do not account for a significant component of the amplifying pathway when β cells are stimulated with glucose as the sole nutrient (Gembal, et al., 1993). It should be noted however that these pathways do enhance GSIS, likely cooperating with the amplifying pathway, if activated for example by fatty acid (Mancini & Poitout, 2013), hormonal, or pharmacological means.

Recently glycogen was shown to be formed in β cell lines and human islets incubated for 48 h in elevated concentrations of glucose (Andersson, et al., 2016), and even as quickly as 1 h in rat islets (Mugabo, et al., 2017). This effect is apparently independent of autocrine insulin signaling because diazoxide does not impair glycogen accumulation. In Andersson, et al. insulin secretion did not depend on glycogen content, so it is unlikely that glycogen metabolism is a major participant in the amplifying pathway. Although, glycogen accumulation under diabetic conditions may contribute to β cell failure (Brereton, et al., 2016).

Glucose and amino acids themselves, signaling through receptors at the plasma membrane, may contribute to the amplification of GSIS. The taste receptor proteins T1R1, T1R2 and T1R3 have been the subject of recent investigation in the β cell and have been shown to impact pathways including mTOR activation and autophagy (Wauson, et al., 2015), cAMP and ATP concentrations (Kojima, et al., 2015; Nakagawa, et al., 2014), and calcium influx (Guerra, et al., 2017). While sweeteners like sucralose have been used to investigate taste receptor signaling, ingestion of sucralose does not result in effective concentrations in plasma (Roberts, et al., 2000). Therefore these sweeteners are most appropriately used as tools to explore specific sweet taste receptor signaling mechanisms that may be engaged by their natural glucose (or fructose) ligands in vivo.

2. In vivo implications of glucose-mediated amplification of insulin secretion

Nutrient-mediated amplification is estimated to account for at least half of second phase insulin secretion in rodent (Henquin, 2009) and human islets (Henquin, et al., 2017), as well as contributing to diet-induced obesity (Vetterli, et al., 2016). Studies of first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetic individuals have suggested that defects in the amplifying pathway underlie β cell dysfunction prior to development of diabetes (Mari, et al., 2005). One of the major metabolic enzymes implicated in the amplifying pathway is glutamate dehydrogenase (Fahien & Macdonald, 2011). Glutamate dehydrogenase converts glutamate into α-ketoglutarate, generating NAD(P)H in the process. Humans with glutamate dehydrogenase gain-of-function mutations develop hyperinsulinism and hypoglycemia (Stanley, 2011). β cell-specific glutamate dehydrogenase inducible knockout mice have reduced insulin secretion, which protects them from high-fat diet induced weight gain (Vetterli, et al., 2016). Nevertheless, these mice manage to maintain near normal glucose homeostasis (Carobbio, et al., 2009). Altered diet with respect to protein and fat content has been shown to alter islet secretory responses. Leite, et al subjected mice to either chow or high-fat (35%) diets in combination with a normal (14%) or low-protein (6%) diet (Leite, et al., 2016). Islets isolated from mice eating the high-fat, low-protein diet had increased glutamate dehydrogenase activity and protein amount and an increased amplifying pathway response. In a different study of the effects of diet on amplifying pathway function, albino mice were transplanted with transgenic islets to allow long-term (4–5 months) measurements of calcium influx during high-fat diet feeding (Chen, C., et al., 2016). Transplanted β cells in the high-fat diet fed mice responded with increased GSIS in the face of reduced calcium dynamics, essentially resulting in enhanced calcium efficacy. Together these studies suggest that the amplifying pathway participates in compensatory increases in islet β cell function in vivo in response to diet, although the specific underlying signaling or transcriptional mechanisms are not clear.

At least one transcriptional regulator, Foxa2 (previously Hnf3β), has been linked to control of triggering and amplification. Islets from β cell-specific Foxa2 knockout mice had no response to glucose or sulfonylurea in the presence of stimulatory concentrations of amino acids (Lantz, et al., 2004), suggesting a defect in the amplifying pathway. Foxa2 regulates the expression of triggering pathway genes (SUR1 and KIR6.2), as well as HADH, which encodes short-chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (SCHAD) (Figure 1, #10). SCHAD is essential for mitochondrial β-oxidation of short-chain fatty acids, generating NADH and acetoacetyl-CoA. Interestingly, SCHAD directly binds and inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase, which as discussed earlier, is required for amplification. Deficiency of SCHAD in humans leads to persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy (Clayton, et al., 2001), which fits with its role in glutamate dehydrogenase inhibition.

Targeted and well-controlled pharmacological activation of glutamate dehydrogenase may be a way to enhance GSIS from unresponsive β cells in type 2 diabetes. One such promising example is a novel small molecule allosteric activator of glutamate dehydrogenase (N1-[4-(2-aminopyrimidin-4-yl)phenyl]-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzene-1-sulfonamide) which was found to be 1000-fold more potent than the leucine analog BCH (Smith & Smith, 2016). Another key node in nutrient sensing is the kinase LKB1. β cell-specific LKB1 knockout mice had improved glucose tolerance and increased plasma insulin concentrations (Swisa, et al., 2015). Using diazoxide and sulfonylurea in perifusion studies from the islets of these mice showed an enhanced amplifying pathway. Interestingly, these β cells have disrupted mitochondrial integrity and have lost their secretory response to a combination of methyl succinate and α-ketoisocaproate. Indeed, certain LKB1 substrates are already implicated in the control of GSIS, such as AMPK (Scott, et al., 2015), SADK (Nie, et al., 2013), and SIK2 (Sakamaki, et al., 2014).

3. Complementary models to understand metabolic amplification of hormone secretion

3.1 Computational modeling of β cell insulin secretion

Through the computational modeling of β cell glucose uptake (Luni, et al., 2012), metabolic processes, ionic fluxes and insulin secretion (Chen, Y. D., et al., 2008; Fridlyand & Philipson, 2011, 2016; Ha, et al., 2016), we have moved closer to predicting in silico which perturbations influence the amplifying pathway. Work from the Sherman lab has shown that kinetic modeling can account for both the triggering and amplifying components of insulin secretion (Chen, Y. D., et al., 2008). The amplifying signal was suggested to act through resupplying granules to the docked and primed pools, essentially speeding up the flux of insulin granules from reserve to releasable pools. Another possibility suggested by modeling is that the amplifying signal may increase the fusion rate of restless newcomer granules (Fridlyand & Philipson, 2011). Oscillations in calcium influx and metabolic rates also occur in β cells and modeling suggests that when these oscillations are in phase, the amplifying pathway can enhance insulin secretion, but if they are out of phase the effect is lost. Some testable predictions have been made using the dual oscillator model which combines models of rapid electrical oscillations (i.e. intracellular calcium concentrations) and relatively slower metabolic oscillations (i.e. glycolysis) (Watts, et al., 2014). In this model, metabolic oscillations do not always rely upon calcium influx, although calcium influx does enhance metabolic oscillations (McKenna, et al., 2016; Merrins, et al., 2010). The authors went on to experimentally confirm predictions made by the dual oscillator model using both diazoxide treatment and SUR1 knockout islets and monitoring multiple glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolic readouts (Merrins, et al., 2010; Merrins, et al., 2016).

Further modeling from the Satin lab supports the idea that failure of β cell compensation leads to diabetes (Ha, et al., 2016). Modest reductions in insulin sensitivity are compensated for by β cells via temporarily left-shifting their glucose dose-response curve and increasing β cell mass until blood glucose is stabilized. In type 2 diabetes however, a larger drop in insulin sensitivity means β cell insulin secretion is insufficient to restore normoglycemia resulting in a positive feedback loop that leads to reduced β cell mass and sustained hyperglycemia. The model was then corroborated by the authors with experimental evidence from rodent islets (Glynn, et al., 2016). In that study, the hyperglycemia-induced left-shift in the glucose dose-response curve was explained by a reduction in KATP channel conductance due to reduced SUR1 membrane trafficking.

Taken together, these predictions make it possible to design in vitro and ex vivo experiments to pick apart how the amplifying pathway works (and how it may fail in disease) as exemplified in the studies above. Advances in modeling of β cell function will likely be complemented by findings in closely related fields, such as L cell biology, where predictions suggest the importance of apical-basal polarity in the regulation of GLP-1 secretion (Tagliavini & Pedersen, 2017). Luminal glucose influx through sodium-glucose cotransporters stimulates the triggering pathway and vascular glucose influx through GLUT2 activates the amplifying pathway in the L cell. Whether similar mechanisms are at work in the pancreatic islet β cell is an interesting topic given that β cells exhibit distinct cell polarity features (Gan, et al., 2017).

3.2 Metabolic amplification of hormone secretion from non-β cells

Work in β cell-related neuroendocrine cell types, such as other islet cell types and enteroendocrine cells helps progress our understanding of β cell function. Studies of these different cell types indicate that versions of metabolic amplification of hormone secretion may be utilized in other systems and contexts. The islet δ cell has been suggested to secrete somatostatin in a KATP-independent manner (Braun, et al., 2009; Zhang, Q., et al., 2007). The GLP-1-secreting L cells of the small intestine exhibit properties very similar to β cells when treated with glucose in the presence of diazoxide and depolarizing KCl (Parker, et al., 2012; Tagliavini & Pedersen, 2017). Gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP)-producing K cells in the gut may also contain a similar KATP-independent pathway, because they express the KATP channel components at low levels, but their hormone secretion is still nutrient-regulated (Wang, S. Y., et al., 2003). Another metabolic regulatory hormone, ghrelin, is secreted pre-prandially from cells in the gut and is thought to help prepare the body for nutrient uptake (Muller, T. D., et al., 2015). Recently, a ghrelin-expressing cell line was shown to secrete in a manner dependent upon KATP channels (Oya, et al., 2015). In contrast, using the diazoxide paradigm in primary ghrelin cells, no function was found for KATP channels in ghrelin secretion (Sakata, et al., 2012). These disparate findings likely have to do with primary versus cell line cultures, as well as the media and stimulation contexts; in vivo studies of tissue-specific genetically modified ghrelin-cells will likely aid in determining the existence of metabolic amplification of ghrelin secretion. The possibility that GLP-1-, GIP-, and ghrelin-secreting cells utilize a nutrient-regulated amplifying pathway similar to β cells is intriguing. Determining what aspects of amplification are β cell-specific as opposed to common across neuroendocrine cells may be of value for defining mechanisms in the amplifying pathway and for driving β cell-targeted therapies.

4. β cell therapeutics

Careful manipulation of the amplifying pathway as a therapeutic target may be a useful strategy to treat diabetes. Because multiple mechanisms are involved, there are multiple targetable nodes. Such treatments that enhance the amplifying pathway may increase insulin secretion in response to any stimuli (not just glucose) that trigger β cell calcium influx. Therefore, to avoid dangerous hypoglycemia, any therapy must have little to no effect in the absence of nutrient secretagogues. Signaling cascades that feed into or complement the amplifying pathway have been targeted for years (e.g. GLP-1). Future high-throughput screens under conditions where the amplifying pathway is specifically manipulated will lead to a greater diversity of targetable pathways (Kalwat, et al., 2016). A few developing pharmacological avenues that may either act directly on or significantly influence glucose-mediated amplification are highlighted in this section. For in-depth information pertaining to novel treatments for type 2 diabetes targeted across multiple tissues, please see (Bailey, 2017; Scheen, 2016).

4.1 Incretins and Decretins

GLP-1 analogs and inhibitors of GLP-1 degradation (dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) inhibitors) have been widely used as therapies for diabetes. Last year, Berggren’s group reported that extended treatment with liraglutide eventually led to impaired function of human islet transplants in mice (Abdulreda, et al., 2016). While the specifics may vary, many currently used diabetes therapeutics, in addition to GLP-1 analogs, turn out to have negative effects. The most well-known treatment for diabetes, injection of insulin, also has negative consequences (Lebovitz, 2011). Not only does injection of insulin not mimic the impact of endogenous insulin on islets and the liver (Unger & Roth, 2015), long-term intensive insulin treatment can lead to weight gain, risk of hypoglycemic episodes, and potentially increased cancer risk (Lebovitz, 2011). The general requirement of injections for both GLP-1 analogs and insulin is generally less favorable than oral medication. That issue is addressed by subcutaneous pumps for insulin or GLP-1 analogs, as well as orally bioavailable formulations [reviewed in (Meier & Nauck, 2015)]. DPP-IV inhibitors (or ‘gliptins’) are orally administered and have a relatively low risk of hypoglycemia. While there are still some safety parameters to monitor in certain patient populations (e.g. renal function, pancreatitis) (George & Joseph, 2014), these drugs overall have safety comparable to placebo (Mahmoud, et al., 2017). Therefore, even with the currently available, generally well-tolerated diabetes therapies, there is room for advancement and development of new strategies with fewer drawbacks.

Insulin secretion from β cells is also subject to multiple endogenous suppressive regulatory pathways. These include sympathetic neural inputs (Thorens, 2014), norepinephrine/epinephrine (Straub & Sharp, 2012), ghrelin (Muller, T. D., et al., 2015), somatostatin (Kailey, et al., 2012), and ‘decretin’ hormones (e.g. neuromedin U (Alfa, et al., 2015)) (Figure 1, #8). The existence of ‘decretin’ receptors in islets suggests it may be possible to antagonize their inhibitory actions on the islet. Such a strategy may allow for controlled enhancement of GSIS during hyperglycemia, possibly through interactions with the amplifying pathway. Bioengineered decretin hormones might also allow better fine-tuning of islet responses, for example, as a component of a multi-hormonal artificial pancreas system.

4.2 GPR40/GPR119

The GPR40 and GPR119 G-protein coupled receptors are expressed in β cells, are activated by free fatty acids, and signal by distinct mechanisms (Yamada, et al., 2016), as discussed earlier. While GPR40 activates protein kinase C/[Ca2+]i and protein kinase D pathways (Mancini & Poitout, 2013), GPR119 acts through a cAMP signaling pathway. GPR40 was targeted pharmacologically with success using a small molecule TAK-875, but complications with liver toxicity ended development of this specific therapy. GPR119 agonists have also been developed and shown to potentiate insulin secretion selectively under elevated glucose concentrations (Ohishi & Yoshida, 2012), although studies in type 2 diabetic patients suggests targeting GPR119 may not alter β cell function in humans in vivo and could be complicated by effects on non-islet tissues (Nunez, et al., 2014). Utilizing these receptors as therapeutic targets is still a potentially viable strategy as alternate and more specific molecules are in development. Because these receptors are also active on enteroendocrine cells (e.g. GLP-1-secreting L cells) (Edfalk, et al., 2008), targeting these pathways is expected to have synergistic effects by acting on amplification in multiple cell types to aid blood glucose homeostasis.

4.3 ARA290

Erythropoietin has been studied for its antidiabetic effects in β cells (Choi, et al., 2010), but stimulation of erythropoiesis has been a roadblock for its use as a diabetes therapy. ARA290 is an erythropoietin analogue of 11 amino acids which does not increase hematopoiesis (Brines, et al., 2008). ARA290 exerts its protective effects via the innate repair receptor, a heterodimer of erythropoietin receptor and CD131 (Brines & Cerami, 2006). ARA290 enhances GSIS specifically in islets isolated from diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats but not from wild-type rats (Muller, C., et al., 2015). The authors used the diazoxide paradigm to demonstrate a specific effect on the amplifying pathway, which was dependent on PKA activation and calcium influx. ARA290 was recently studied in a clinical trial by the same researchers and found to have positive effects on HbA1c and nerve pain, among other parameters, in patients with type 2 diabetes (Brines, et al., 2015). Further development of small molecules that target this signaling pathway may yield valuable treatments for dysfunctional β cells.

4.4 Imeglimin

Recently a new drug, imeglimin, has been pursued as a type 2 diabetes therapy. This first-in-class small molecule was effective in patients with type 2 diabetes, causing reduced fasting plasma glucose and improved β cell function (Pacini, et al., 2015; Pirags, et al., 2012). Imeglimin was determined to amplify biphasic insulin secretion in response to glucose, in rat islet perifusion studies (Perry, et al., 2016). The authors also tested leucine and a methyl ester of succinate, which induced biphasic secretion, although imeglimin did not amplify these responses in perifusion. Proposed mechanisms for the effects of imeglimin are via modulation of oxidative phosphorylation (in liver) (Vial, et al., 2015), and through increased NAD synthesis via the salvage pathway in rat islets (Hallakou-Bozec, et al., 2016). Given its effectiveness both in vitro and in vivo in rats and successful use thus far in limited human trials, imeglimin holds promise as a new class of type 2 diabetes therapy.

5. Concluding Remarks

We propose that mature β cells exist in a phenotypic state that supports a well-regulated metabolic amplifying pathway of hormone secretion which is the summation of 1) generation of reducing equivalents in the form of NADPH and glutathione, which support the requisite deSUMOylation of exocytotic proteins, 2) pentose phosphate pathway-derived products like adenylosuccinate, 3) Rho GTPase signaling, 4) synthesis of lipid effectors (e.g. MAG) from glucose-induced release of free fatty acids, and 5) oscillatory metabolic and calcium influx behavior. The amplifying pathway component of either the first- and/or second-phase of insulin secretion that is impacted by these factors is defined in some cases. β cells are only able to maintain such a phenotypic state due to the expression of specific transcription factors (Figure 1, #10) as well as certain proteins with short half-lives (Figure 1, #11). While the amplifying pathway occurs independent of further increases in intracellular calcium concentration, the fact that calcium enhances and oscillates in sync with mitochondrial metabolism suggests that calcium influx augments the production of the very signals that require calcium in order to mediate amplification of insulin secretion.

With the advent of powerful techniques to analyze nutrient metabolism and signaling, a more complete model of β cell glucose-stimulated triggering and amplifying pathways may emerge. Recently published higher-resolution structures of the KATP channel (Li, et al., 2017; Martin, et al., 2017) pave the way for improved or novel drug targeting efforts to modulate the triggering pathway. Theoretically, if the triggering and amplifying pathways are controlled or tweaked through pharmacological means, it may be possible to override β cell dysfunction and control insulin secretion more exquisitely in disease. Even given such control, it would still be necessary to protect β cells from continued dysfunction, dedifferentiation or death in the face of pathophysiology and the possible negative effects of such pharmacological therapies. Even generally safe therapeutics, such as GLP-1 mimetics, may have unintended obstacles (Abdulreda, et al., 2016). This example highlights the need for further characterization and mechanistic understanding of β cell function, as well as novel targeted therapeutics. The possibility of utilizing current and as-yet-undiscovered islet-specific drug targeting methods (e.g. GLP-1-small molecule conjugates; (Finan, et al., 2016; Finan, et al., 2012)) to target β cell amplifying pathway regulation is exciting, and innovative strategies like this may lead to substantial therapeutic advances. It is worth noting that while many translatable findings have come from studies of rodent pancreatic islets and immortalized cell lines, studying the metabolic amplifying pathway in islets from healthy and diabetic human donors is of significant importance to understanding both normal and pathophysiological states. Additionally, the similarities between β cells and other neuroendocrine cells, such as intestinal L cells, lends credence to the idea that a similar nutrient-mediated regulation of hormone secretion may be conserved across certain neuroendocrine and related cell types, even though such pathways are likely utilized in context-specific manners. The combinatorial application of metabolomics, transcriptomics, computational modeling, and high-throughput screening of islet β cell function should be encouraged because these efforts will drive novel breakthroughs in therapy and enrich our comprehension of molecular mechanisms of islet nutrient response.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the Cobb lab for helpful discussions, as well as Dr. Latha Ramalingam for critical review of this manuscript. We would like to acknowledge our funding sources: F32 DK100113 (to MAK) and R01 DK55310 and R37 DK34128 (to MHC) and the Welch Foundation I1243.

Abbreviations

- ABCC8

ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 8

- ADCY5

adenylyl cyclase type 5

- AICAR

5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside

- DPP-IV

dipeptidyl peptidase 4

- G6PD

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GDH

glutamate dehydrogenase

- GIP

gastric inhibitory peptide

- GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

- GLUT1

glucose transporter 1

- GLUT2

glucose transporter 2

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GSIS

glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- HMG-CoA

hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA

- KATP

ATP-sensitive potassium channel

- KCNJ11

Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily J member 11

- Kir6.2

inward-rectifying potassium channel 6.2

- MAG

monoacylglycerol

- ME1

malic enzyme 1

- ME2

malic enzyme 2

- ME3

malic enzyme 3

- NAD(P)H

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate)

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKD

protein kinase D

- PLC

phospholipase C

- RhoGDI

Rho guanine dissociation inhibitor

- S-AMP

adenylosuccinate

- SCHAD

L-3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase

- SENP

sentrin/SUMO-specific protease

- SENP1

sentrin-specific protease 1

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-like modifier

- SUR1

sulfonylurea receptor 1

- ZMP

5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdulreda MH, Rodriguez-Diaz R, Caicedo A, Berggren PO. Liraglutide Compromises Pancreatic beta Cell Function in a Humanized Mouse Model. Cell Metab. 2016;23:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriaenssens AE, Svendsen B, Lam BY, Yeo GS, Holst JJ, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Transcriptomic profiling of pancreatic alpha, beta and delta cell populations identifies delta cells as a principal target for ghrelin in mouse islets. Diabetologia. 2016;59:2156–2165. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4033-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. Molecular biology of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:101–135. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.2.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfa RW, Park S, Skelly KR, Poffenberger G, Jain N, Gu X, Kockel L, Wang J, Liu Y, Powers AC, Kim SK. Suppression of insulin production and secretion by a decretin hormone. Cell Metab. 2015;21:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves TC, Pongratz RL, Zhao X, Yarborough O, Sereda S, Shirihai O, Cline GW, Mason G, Kibbey RG. Integrated, Step-Wise, Mass-Isotopomeric Flux Analysis of the TCA Cycle. Cell Metab. 2015;22:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson LE, Nicholas LM, Filipsson K, Sun J, Medina A, Al-Majdoub M, Fex M, Mulder H, Spegel P. Glycogen metabolism in the glucose-sensing and supply-driven beta-cell. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:4242–4251. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anello M, Ucciardello V, Piro S, Patané G, Frittitta L, Calabrese V, Giuffrida Stella AM, Vigneri R, Purrello F, Rabuazzo AM. Chronic exposure to high leucine impairs glucose-induced insulin release by lowering the ATP-to-ADP ratio. AJP: Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2001;281:E1082–E1087. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.5.E1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara S, Shibutani Y, Teruyama K, Inoue HY, Kawada Y, Etoh H, Matsuda T, Kimura-Koyanagi M, Hashimoto N, Sakahara M, Fujimoto W, Takahashi H, Ueda S, Hosooka T, Satoh T, Inoue H, Matsumoto M, Aiba A, Kasuga M, Kido Y. Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (RAC1) regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion via modulation of F-actin. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1088–1097. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2849-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Diabetes mellitus and the beta cell: the last ten years. Cell. 2012;148:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CJ. Future Drug Treatments for Type 2 Diabetes. In: Holt R, Cockram C, Flyvbjerg A, Goldstein B, editors. Textbook of Diabetes. 5th. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2017. pp. 1000–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Barg S, Huang P, Eliasson L, Nelson DJ, Obermüller S, Rorsman P, Thévenod F, Renström E. Priming of insulin granules for exocytosis by granular Cl−uptake and acidification. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2145–2154. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.11.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdan CA, Erion KA, Burritt NE, Corkey BE, Deeney JT. Inhibition of Monoacylglycerol Lipase Activity Decreases Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in INS-1 (832/13) Cells and Rat Islets. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand G, Ishiyama N, Nenquin M, Ravier MA, Henquin JC. The elevation of glutamate content and the amplification of insulin secretion in glucose-stimulated pancreatic islets are not causally related. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32883–32891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S, Oler AT, Rabaglia ME, Stapleton DS, Schueler KL, Truchan NA, Worzella SL, Stoehr JP, Clee SM, Yandell BS, Keller MP, Thurmond DC, Attie AD. Positional cloning of a type 2 diabetes quantitative trait locus; tomosyn-2, a negative regulator of insulin secretion. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Ramracheya R, Amisten S, Bengtsson M, Moritoh Y, Zhang Q, Johnson PR, Rorsman P. Somatostatin release, electrical activity, membrane currents and exocytosis in human pancreatic delta cells. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1566–1578. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1382-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brereton MF, Rohm M, Shimomura K, Holland C, Tornovsky-Babeay S, Dadon D, Iberl M, Chibalina MV, Lee S, Glaser B, Dor Y, Rorsman P, Clark A, Ashcroft FM. Hyperglycaemia induces metabolic dysfunction and glycogen accumulation in pancreatic beta-cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13496. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Cerami A. Discovering erythropoietin’s extra-hematopoietic functions: biology and clinical promise. Kidney Int. 2006;70:246–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Dunne AN, van Velzen M, Proto PL, Ostenson CG, Kirk RI, Petropoulos IN, Javed S, Malik RA, Cerami A, Dahan A. ARA 290, a nonerythropoietic peptide engineered from erythropoietin, improves metabolic control and neuropathic symptoms in patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Med. 2015;20:658–666. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brines M, Patel NS, Villa P, Brines C, Mennini T, De Paola M, Erbayraktar Z, Erbayraktar S, Sepodes B, Thiemermann C, Ghezzi P, Yamin M, Hand CC, Xie QW, Coleman T, Cerami A. Nonerythropoietic, tissue-protective peptides derived from the tertiary structure of erythropoietin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10925–10930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LJ, Longacre MJ, Hasan NM, Kendrick MA, Stoker SW, Macdonald MJ. Chronic reduction of the cytosolic or mitochondrial NAD(P)-malic enzyme does not affect insulin secretion in a rat insulinoma cell line. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35359–35367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun T, Li N, Jourdain AA, Gaudet P, Duhamel D, Meyer J, Bosco D, Maechler P. Diabetogenic milieus induce specific changes in mitochondrial transcriptome and differentiation of human pancreatic islets. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:5270–5284. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron WD, Bui CV, Hutchinson A, Loppnau P, Graslund S, Rocheleau JV. Apollo-NADP(+): a spectrally tunable family of genetically encoded sensors for NADP(+) Nat Methods. 2016;13:352–358. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JE, Drucker DJ. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab. 2013;17:819–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Li X, Li J, Kang B, Chen J, Luo W, Huang C. SUMOylation of RhoGDIalpha is required for its repression of cyclin D1 expression and anchorage-independent growth of cancer cells. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carobbio S, Frigerio F, Rubi B, Vetterli L, Bloksgaard M, Gjinovci A, Pournourmohammadi S, Herrera PL, Reith W, Mandrup S, Maechler P. Deletion of glutamate dehydrogenase in beta-cells abolishes part of the insulin secretory response not required for glucose homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:921–929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter L, Mitchell CJ, Xu ZZ, Poronnik P, Both GW, Biden TJ. PKC Is Activated But Not Required During Glucose-Induced Insulin Secretion From Rat Pancreatic Islets. Diabetes. 2003;53:53–60. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chmelova H, Cohrs CM, Chouinard JA, Jahn SR, Stertmann J, Uphues I, Speier S. Alterations in beta-Cell Calcium Dynamics and Efficacy Outweigh Islet Mass Adaptation in Compensation of Insulin Resistance and Prediabetes Onset. Diabetes. 2016;65:2676–2685. doi: 10.2337/db15-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YD, Wang S, Sherman A. Identifying the targets of the amplifying pathway for insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells by kinetic modeling of granule exocytosis. Biophys J. 2008;95:2226–2241. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.124990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D, Schroer SA, Lu SY, Wang L, Wu X, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Gaisano HY, Wagner KU, Wu H, Retnakaran R, Woo M. Erythropoietin protects against diabetes through direct effects on pancreatic beta cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2831–2842. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang JC, Sakata I, Kohno D, Perello M, Osborne-Lawrence S, Repa JJ, Zigman JM. Ghrelin directly stimulates glucagon secretion from pancreatic alpha-cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1600–1611. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civelek VN, Deeney JT, Kubik K, Schultz V, Tornheim K, Corkey BE. Temporal sequence of metabolic and ionic events in glucose-stimulated clonal pancreaticβ-cells (HIT) Biochemical Journal. 1996;315:1015–1019. doi: 10.1042/bj3151015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton PT, Eaton S, Aynsley-Green A, Edginton M, Hussain K, Krywawych S, Datta V, Malingre HE, Berger R, van den Berg IE. Hyperinsulinism in short-chain L-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency reveals the importance of beta-oxidation in insulin secretion. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:457–465. doi: 10.1172/JCI11294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DL, Ikeuchi M, Fujimoto WY. Lowering of pHi inhibits Ca2+-activated K+ channels in pancreatic B-cells. Nature. 1984;311:269–271. doi: 10.1038/311269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai XQ, Plummer G, Casimir M, Kang Y, Hajmrle C, Gaisano HY, Manning Fox JE, MacDonald PE. SUMOylation regulates insulin exocytosis downstream of secretory granule docking in rodents and humans. Diabetes. 2011;60:838–847. doi: 10.2337/db10-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S, Noda M, Straub SG, Sharp GW. Identification of the docked granule pool responsible for the first phase of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 1999;48:1686–1690. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]