The VapBC22 toxin-antitoxin system regulates adaptation to oxidative stress and virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Abstract

Virulence-associated protein B and C toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are widespread in prokaryotes, but their precise role in physiology is poorly understood. We have functionally characterized the VapBC22 TA system from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Transcriptome analysis revealed that overexpression of VapC22 toxin in M. tuberculosis results in reduced levels of metabolic enzymes and increased levels of ribosomal proteins. Proteomics studies showed reduced expression of virulence-associated proteins and increased levels of cognate antitoxin, VapB22 in the ΔvapC22 mutant strain. Furthermore, both the ΔvapC22 mutant and VapB22 overexpression strains of M. tuberculosis were susceptible to killing upon exposure to oxidative stress and showed attenuated growth in guinea pigs and mice. Host transcriptome analysis suggests upregulation of the transcripts involved in innate immune responses and tissue remodeling in mice infected with the ΔvapC22 mutant strain. Together, we demonstrate that the VapBC22 TA system belongs to a key regulatory network and is essential for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems are small genetic elements that compose of a stable toxin and an antitoxin that neutralizes the toxin activity (1, 2). TA systems are widely distributed in prokaryotes in multiple copies and have been shown to contribute to stress adaptation, persisters, biofilm formation, or pathogenesis (3–7). The toxins are invariably translated into a protein, whereas the antitoxin can either be a protein or RNA (1, 8). TA modules have been classified into six different types based on the nature of antitoxin and the mechanism by which antitoxin negates toxin activity (8). In type II TA systems, the most well-characterized family, the antitoxin negates the activity of the cognate toxin by forming a tight complex through direct interactions. The antitoxins belonging to type II TA systems have inherently disordered regions, which makes them susceptible to cleavage by cellular proteases (9, 10). This proteolytic degradation results in the release of toxin that subsequently interferes with various cellular processes such as transcription, translation, DNA replication, cell wall synthesis, and cell division (11).

Various bioinformatics and phylogenetic analyses have revealed that the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome encodes a notably large repertoire of TA systems (12, 13). The conservation of these TA systems in species belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex suggests that they regulate metabolic pathways that are essential for bacterial pathogenesis. Mostly, the M. tuberculosis systems belong to type II TA systems such as VapBC, MazEF, ParDE, RelBE, and HigBA (12, 13). VapC toxins belonging to VapBC TA systems contain a PilT N terminus (PIN) domain that has a ribonuclease H–like fold, and their activity is neutralized by cognate VapB antitoxins (14). Using ultraviolet-induced cross-linking and deep sequencing, Winther et al. (15) showed that these ribonucleases cleave either transfer RNA (tRNA) or the sarcin-ricin loop of 23S ribosomal RNA. The structures of various VapC toxins, either alone or in complex with their cognate antitoxins, have been solved, but the basis for their substrate specificity is poorly understood. Several studies have shown that TA systems are differentially expressed under stress conditions and ectopic expression of toxins inhibits growth in a bacteriostatic manner (12, 16, 17). It has also been reported that overexpression of toxins results in morphological changes that might lead to drug tolerance (17). Growth of M. tuberculosis strains with deletions in either toxins or TA systems is attenuated in guinea pigs and mice, but the exact mechanism by which these TA modules contribute to pathogenesis is poorly understood (16–18).

Here, we have functionally characterized the VapBC22 TA system from M. tuberculosis. We show that overexpression of VapC22 results in bacteriostasis and transcriptional reprogramming that is similar to that observed in M. tuberculosis exposed to nutrient-limiting and low-oxygen conditions. Proteome analysis revealed increased expression of VapB22 and reduced levels of various virulence-associated proteins in mid-log phase cultures of ΔvapC22 strain. We also demonstrate that changes in the relative levels of antitoxin and toxin are essential for M. tuberculosis to adapt to oxidative stress and establish infection in host tissues. Host transcriptomic analysis revealed that in comparison to the parental strain, infection with ΔvapC22 mutant strain resulted in enhanced innate immune response as evident by higher infiltration of neutrophils, eosinophils, dendritic cells, and suppressed T helper 1 cell (TH1) response in lung tissues. Together, this study provides newer insights into the contribution of TA systems to bacterial pathogenesis.

RESULTS

VapC22 encodes for a ribonuclease and inhibits Mycobacterium smegmatis growth in a bacteriostatic manner

To functionally characterize the VapBC22 TA pair, VapC22 was cloned and expressed using an anhydrotetracycline (Atc)–inducible expression vector, pTetR (17). As shown in fig. S1A, overexpression of VapC22 exerted a bacteriostatic effect on M. smegmatis growth. In concordance with absorbance-based assays, in our cell viability experiments, we observed no difference in bacterial counts after 24 hours after Atc induction in comparison to time zero samples. To determine morphological changes upon overexpression of VapC22, we performed fluorescence microscopy experiments using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, which preferably stains the nucleoid DNA. We observed that the nucleoid was uniformly distributed in the parental strain; however, in the M. smegmatis strain overexpressing VapC22, they were compact and condensed either in the middle or at the poles (fig. S1B). However, the length of the bacilli overexpressing VapC22 was comparable to parental strain harboring pTetR vector only (fig. S1C).

VapC toxins have ribonuclease activity and are characterized by the presence of a PIN domain (14, 19). To test whether the observed growth inhibition upon VapC22 overexpression is a result of its ribonuclease activity, we performed in vitro ribonuclease activity (IVRA) assay using MS2 RNA. As previously reported, we observed that VapC22 is a functionally active ribonuclease and was able to cleave MS2 RNA (fig. S1D) (12). Previously, we have shown that Mn2+ plays an important role in VapC11 ribonuclease activity (18). In concordance, we also observed that the inclusion of Mn2+ ions in the assay buffer enhanced the ribonuclease activity associated with VapC22 (fig. S1D). Hence, the observed growth inhibition effects can be attributed to VapC22 ribonuclease activity. Winther et al. (15) have used a phylogenetic analysis-based approach to predict potential targets for VapC toxins. Phylogenetic analysis suggests that VapC22 is closely related to VapC11 (15). Since M. tuberculosis VapC11 cleaves tRNA-LeuCAG, we performed IVRA assays using tRNA-LeuCAG. However, VapC22 was unable to cleave tRNA-LeuCAG as revealed by IVRA assays (fig. S1D).

VapB22 and VapC22 form homodimeric VapBC22 complex in solution

Oligomeric states play an important role in functional and regulatory mechanisms in biomolecular systems. Previously, it has been shown that VapB and VapC proteins form homodimers in solution and in x-ray crystal structures (18, 20, 21). To determine the oligomeric state(s) of VapB22, VapC22, and VapBC22 complex in solution, we performed analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) studies. At 15 μM concentration, we observed that both VapB22 and VapC22 form predominantly homodimeric species with observed Sw (S) 1.95 (frictional ratio of 1.52) and Sw (S) 2.46 (frictional ratio of 1.40), respectively (fig. S1E). AUC analysis of purified VapBC22 showed that both toxin and antitoxin interact with each other and form a heterotetrameric species with observed Sw (S) 2.82 with a frictional ratio of 1.47 (fig. S1E). However, we were only able to perform these experiments until 15 μM concentration as VapBC22 tends to form aggregates at higher concentration. Nonetheless, the oligomeric states and mode of TA interactions in the case of VapBC22 are similar to the model proposed in the previous studies (20, 21).

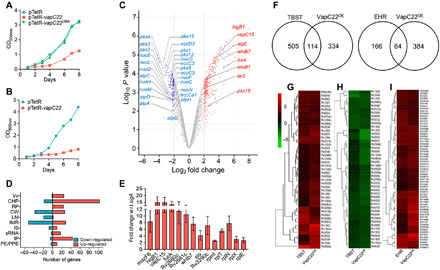

The global transcriptional response upon ectopic overexpression of VapC22 overlaps with the mycobacterial responses to multiple stresses

The overexpression of VapC22 inhibited the growth of both Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and M. tuberculosis in a bacteriostatic manner similar to that seen in the case of M. smegmatis (Fig. 1, A and B). As expected, substitution of a highly conserved PIN domain residue (aspartic acid at position 8 with alanine) rendered VapC22 inactive in M. bovis BCG leading to abrogation of the growth inhibitory effect (Fig. 1A). Using LIVE-DEAD cell viability kit, we observed that bacteria overexpressing various VapC toxins including VapC22 were viable after 48 hours after induction (fig. S2). Our earlier observation that ectopic expression of VapC11 (Rv1561) leads to reprogramming of mycobacterial transcription machinery prompted us to investigate differential gene expression profiles induced by VapC22 overexpression in the M. tuberculosis transcriptome (18). To identify differentially expressed genes, total RNA was isolated from early-log phase cultures of M. tuberculosis parental and overexpression strains at 24 hours after Atc induction and subjected to transcriptome analysis. We considered transcripts with an adjusted P value (Padj) of <0.05 and a log2 fold change of ≤2.0 or ≥2.0 as significantly differentially expressed upon VapC22 overexpression. We found that in the presence of free VapC22, the transcript levels of 447 genes were significantly changed, among these 293 were induced, and 154 were repressed (Fig. 1C). These numbers indicate that VapC22 overexpression resulted in significant alteration of gene expression that corresponds to approximately 10% of genes encoded by the genome. We next annotated these differentially expressed genes according to their functional category as provided by Mycobrowser (https://mycobrowser.epfl.ch/). We observed that among the repressed transcripts, approximately 35% of the transcripts were involved in intermediary metabolism and respiration (Fig. 1D). These included various subunits of reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase such as nuoN, nuoC, nuoH, nuoD, nuoF, nuoG, nuoE, nuoM, nuoL, and adenosine 5′-triphosphate synthase subunits such as atpH, atpG, atpA, atpD, and atpC, which were also repressed in M. tuberculosis exposed to nutritional stress (22) (Fig. 1C). In addition to these, transcripts belonging to cell wall processes (25.4%) and lipid metabolism (13.1%) were also significantly decreased (Fig. 1D). These included various enzymes involved in complex lipid biosynthesis such as pks8, pks12, pks1, pks15, pks2, pks4, pks3, eccCa1, eccC3, eccE3, and eccD3 (Fig. 1C). By contrast, among the increased transcripts, approximately 36.6% were annotated as conserved hypothetical proteins and 16% were belonged to information pathways (Fig. 1D). The observed increase in transcription of several ribosomal and ribosome-associated proteins upon inhibition of protein synthesis by VapC22 is similar to the transcriptional profiles obtained upon exposure of M. tuberculosis to translation inhibitors (23). The expression profiles of a subset of transcripts in VapC22 overexpression strain was also confirmed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using gene-specific primers (Fig. 1E). A more detailed analysis revealed that among the differentially expressed genes, approximately 114 and 64 genes were also differentially regulated in M. tuberculosis during starved and enduring hypoxia response, respectively (Fig. 1, F to I) (22, 24). The list and fold change of differentially expressed genes in VapC22 overexpression strain are provided in table S2. Together, these findings implicate that the observed transcriptional reprogramming is probably due to pleiotropic effects of VapC22 overexpression in M. tuberculosis. These changes may be attributed to either (i) ribonuclease activity associated with VapC22 and other induced noncognate toxins or (ii) increased transcript levels of various regulatory proteins in the overexpression strain.

Fig. 1. Effect of overexpression of VapC22 on growth and transcriptomics of M. tuberculosis.

(A and B) The expression of VapC22 and VapC22D8A in M. bovis BCG (A) and M. tuberculosis (B) was induced by the addition of Atc. The growth of various strains was determined by measuring absorbance at 600 nm at regular intervals. The data shown in these panels are representative of three independent experiments. (C to I) Differential gene expression in M. tuberculosis upon VapC22 overexpression. Four hundred forty-seven genes were significantly differentially expressed upon overexpression of VapC22 in M. tuberculosis. (C) The volcano plot displaying gene expression profiles observed 24 hours after VapC22 expression in M. tuberculosis. The y and x axes depict P value and fold change for each gene, respectively. The statistically significant differentially expressed induced and repressed transcripts are highlighted as red and blue dots, respectively. (D) The number of induced and repressed transcripts categorized by functional category is shown. (E) The transcript levels of various differentially expressed genes between the parental and VapC22 overexpression strain at 24 hours after Atc induction were quantified. The data shown in this panel are means ± SE of fold change in the overexpression strain relative to the parental strain obtained from three independent experiments. wrt with respect to (F) Venn diagram showing correlation of differentially expressed genes in VapC22 overexpression strain with nutritionally starved proteome and enduring hypoxia response transcriptome studies. (G to I) Heat maps showing fold change in expression of common genes up-regulated (G) and down-regulated (H) in VapC22 overexpression strain and nutritionally starved bacteria. The common genes up-regulated in our and EHR (enduring hypoxia response) transcriptome are shown in (I). w.r.t., with respect to.

Deletion of ΔvapC22 results in enhanced growth of M. tuberculosis in liquid cultures

To understand the role of VapC22 in mycobacterial physiology, we constructed ΔvapC22 mutant strains of M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis using temperature-sensitive mycobacteriophages (fig. S3A). Southern blot confirmed the replacement of vapC22 coding region with the hygromycin resistance gene (fig. S3B). We were unable to detect vapC22 transcript levels in both M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis ΔvapC22 strains (fig. S3C). The complemented strain was generated by introducing VapBC22 under the transcriptional control of its native promoter in the mutant strain using pMV306K, an integrative vector. The complementation of mutant strains with VapC22 was confirmed by qPCR (fig. S3C). Next, we compared the growth patterns of parental, ΔvapC22 mutant, and ΔvapC22-complemented strain in Middlebrook 7H9 medium in vitro. We observed that ΔvapC22 mutant strain showed an altered growth rate and attained late-log and stationary phase faster as compared to the parental strain (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, to confirm whether the altered growth phenotype was solely associated with the deletion of vapC22, we performed growth kinetic experiments using the ΔvapC22-complemented strain. As shown in Fig. 2B, the bacterial counts after days 4 and 7 of growth in the case of complemented strain was comparable to those observed for the parental strain (*P < 0.05). These observations confirmed that the altered growth pattern of the mutant strain was attributed to the deletion of vapC22 in M. tuberculosis. Further, we observed that the deletion of VapC22 does not affect the colony morphology and biofilm formation of M. tuberculosis. These findings suggest that disruption of VapC22 does not affect cell to cell interaction of M. tuberculosis.

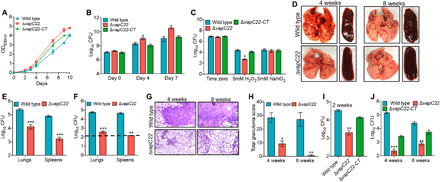

Fig. 2. Susceptibility of M. tuberculosis strains under various stress conditions and host tissues.

(A and B) In vitro growth curves of wild-type, ΔvapC22, and ΔvapC22-complemented strains in liquid cultures. The growth kinetics of parental, ΔvapC22, and ΔvapC22-complemented strains was performed in Middlebrook 7H9 medium by measuring either optical density at 600 nm (OD600nm) (A) or colony-forming unit (CFU) analysis (B) at regular intervals. (C) The effect of deletion of vapC22 on M. tuberculosis susceptibility upon exposure to oxidative and nitrosative stress. Early-log phase cultures of various strains were exposed to either oxidative or nitrosative stress. For bacterial enumeration, 10.0-fold serial dilutions were prepared, and 100 μl was plated on Middlebrook 7H11 medium at 37°C for 3 to 4 weeks. The results shown in these panels are means ± SE of data obtained from three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were obtained for the indicated groups (paired two-tailed t test, *P < 0.05). (D to J) The effect of deletion of vapC22 on growth of M. tuberculosis in guinea pigs and immunocompetent mice. (D) The representative images of lung and spleen tissue from guinea pigs infected with either wild-type or ΔvapC22 strain via aerosol route are shown. Photo credit: Sakshi Agarwal, Translational Health Science and Technology Institute. (E and F) The bacterial loads were determined by plating lung and spleen homogenates at 4 weeks (E) and 8 weeks (F) after infection. The homogenates were serially diluted and plated on Middlebrook 7H11 medium at 37°C for 3 to 4 weeks. The data shown in these panels are means ± SE of log10 CFU obtained from either six or seven guinea pigs per group per time point. (G) Lung sections of guinea pigs infected with wild-type and ΔvapC22 strain were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and viewed at a magnification of ×40. Scale bars, 200 μm. Photo credit: Ashok Mukherjee, National Institute of Pathologist. (H) The total granuloma score in H&E-stained sections from wild-type and ΔvapC22-infected guinea pigs was determined as previously described. The data shown in means ± SE of total granuloma score obtained from six or seven animals per group. (I to J) Female Balb/c mice were infected with parental, ΔvapC22 mutant, and ΔvapC22-complemented strains via a low-dose aerosol infection. At 2 weeks (I), 4 weeks, and 8 weeks (J) after infection, lungs were homogenized, serially diluted, and plated to obtain bacterial loads. The data shown in panels B, C, E, F, H, I, and J are means ± SE of log10 CFU obtained from five animals per group per time point. Statistically significant differences were obtained for the indicated groups (paired two-tailed t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

ΔvapC22 strain is more susceptible to oxidative stress in comparison to parental strain but not to other stresses in vitro

Biochemical characterization of TA systems from Escherichia coli and M. tuberculosis has been performed extensively, but studies on their physiological roles are very limited. We next investigated and compared the susceptibility of parental, ΔvapC22 mutant, and ΔvapC22-complemented strains upon exposure to different in vitro stress conditions. As observed in the case of MazF triple mutant strains (ΔmazF369), we noticed that ΔvapC22 was more susceptible to killing by hydrogen peroxide in comparison to the parental strain (16). As shown in Fig. 2C, the killing of ΔvapC22 strain was approximately 50-fold more in comparison to the parental strain after exposure to oxidative stress for 24 hours (*P < 0.05). In addition, complementation of the mutant strain with the wild-type copy restored the original phenotype (Fig. 2C). Our earlier studies showed that the transcript levels of vapC22 were increased under different stress conditions such as nitrosative, nutrient limiting, and low oxygen conditions (17). However, we observed that the susceptibility of ΔvapC22 mutant and ΔvapC22- compelented strains was comparable to wild type upon exposure to these conditions in vitro (Fig. 2C and fig. S3, D to E). We also determined the sensitivity of these strains upon exposure to different cell wall–disrupting agents such as SDS and lysozyme. All strains showed similar killing rates upon exposure to either lysozyme (2.5 mg/ml) or 0.1% SDS (fig. S3, F and G). The biological role of TA systems in bacterial persistence is highly debatable (25–27). We demonstrate that the deletion of VapC22 in M. tuberculosis genome does not affect the formation of persisters in vitro after exposure to either isoniazid or rifampicin (fig. S3H). We also measured the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC99) of parental, mutant, and complemented strain against drugs with different mechanisms of action. Both parental and mutant strain displayed similar MIC99 values for isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and levofloxacin. These observations suggested that VapC22 is essential for M. tuberculosis to adapt to oxidative stress in vitro.

ΔvapC22 strain is attenuated for growth in guinea pigs and mice

To assess the contribution of VapC22 in bacterial pathogenesis, guinea pigs or mice were infected via aerosol route and euthanized at different time points after infection. Gross pathology analysis revealed large-size tubercles in the lungs and spleens of parental strain infected guinea pigs at both 4 and 8 weeks after infection (Fig. 2D). In contrast, corresponding tissues of guinea pigs infected with ΔvapC22 strain exhibited fewer tubercles with significantly reduced gross pathology (Fig. 2D). We observed that the lung bacillary loads were comparable in parental strain–infected guinea pigs at both time points (Fig. 2, E and F). However, the bacterial burdens of ΔvapC22 were decreased at 8 weeks in comparison to 4 weeks after infection. The lung bacillary loads of ΔvapC22 strain–infected guinea pigs were reduced by 18-fold and 140-fold in comparison to parental strain–infected guinea pigs at 4 and 8 weeks after infection, respectively (***P < 0.001; Fig. 2, E and F). In agreement, the splenic bacillary load was reduced by 45-fold in ΔvapC22 mutant-infected guinea pigs at 4 weeks after infection, and these were below the limit of detection at 8 weeks after infection (**P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001; Fig. 2, E and F). Histopathology analysis revealed chronic inflammation in lungs of parental strain infected guinea pigs at both time points (Fig. 2G). In contrast, lung sections of ΔvapC22-infected animals showed fewer granulomas with little evidence of inflammation and larger alveolar space (Fig. 2G). The analysis of the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained sections showed that the total granuloma score of lung section of mutant strain–infected guinea pigs was reduced by 3-fold and 38-fold at 4 and 8 weeks after infection, respectively, in comparison to parental strain–infected guinea pigs (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01; Fig. 2H). A more detailed quantitative analysis revealed reduced numbers of necrotic and non-necrotic granulomas in comparison to parental strain–infected guinea pigs.

In line with guinea pig data, ΔvapC22 was severely attenuated for growth in mouse lung tissues. At 2 weeks after infection, we noticed ~16-fold reduced lung bacillary loads in ΔvapC22-infected mice in comparison to parental strain–infected mice (**P < 0.01; Fig. 2I). At 4 weeks after infection, the bacterial burdens in lungs of animals infected with the parental and ΔvapC22 strain was log10 5.1 and log10 2.3, respectively (***P < 0.001; Fig. 2J). Notably, at 8 weeks after infection, the lung bacillary loads in ΔvapC22-infected mice was reduced by 42-fold in comparison to parental strain–infected animals (**P < 0.01; Fig. 2J). We also observed that the growth phenotype of mutant strain was partially restored in the complemented strain. In summary, M. tuberculosis strain lacking VapC22 is attenuated for growth and virulence in aerosol-infected guinea pigs and mice.

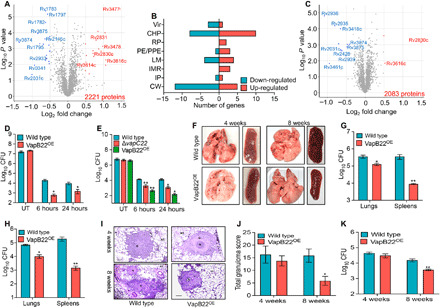

Proteomic changes upon deletion of vapC22 in M. tuberculosis genome

To gain mechanistic insights into the physiological role of VapC22, we performed global proteomic profiling of ΔvapC22 strain and compared it with the parental strain of M. tuberculosis. For proteome analysis, various strains were grown till mid-log phase and subjected to mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. The proteins with a P value (P < 0.05) and a fold change of ≤1.4 or ≥1.4 were considered as differentially expressed proteins. Among the 2221 proteins detected, the relative levels of 58 proteins were altered between the two strains (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, among these, the relative levels of 29 proteins were either increased or decreased, respectively (table S3). We observed that most of the proteins with reduced expression levels have been predicted to be involved in cell wall processes or lipid metabolism (Fig. 3B). These included components of ESAT-6 secretion system-1 [Rv3874 (EsxA) and Rv3875 (EsxB)] and ESX-V (Rv1782, Rv1783, Rv1795, and Rv1797) secretion system (Fig. 3A and table S3) (28). In addition to these, the expression of proteins involved in biosynthesis of mycolic acids [Rv2245 (KasA), Rv2246 (KasB), and Rv2244 (AcpM)] and cell surface lipid, phthiocerol dimycocerosate (PDIM) [Rv2933 (PpsC)], was also reduced (table S3) (29, 30). We also noticed that the levels of Rv2830c (VapB22) and Rv2831 (EchA16) proteins were significantly increased in the mutant strain (Fig. 3A and table S3). Among proteins with elevated expression levels, Rv3477 (PE31), Rv3804c (FbpA), Rv3615c (EspC), Rv3616c (EspA), Rv3478 (PPE60), Rv1638a, Rv2376 (Cfp2), Rv3614c (EspD), and Rv3479 have been reported to be repressed in the ΔphoP mutant strain (31). These observations suggested that VapC22 might regulate these genes in a posttranscriptional manner. We next investigated whether VapC22 cleaves transcripts of VapB22 and EchA16 in vitro. However, our in vitro ribonuclease assays suggest that VapC22 is unable to cleave either vapB22 or echA16 transcripts.

Fig. 3. Effect of VapB22 overexpression on survival of M. tuberculosis under oxidative stress condition and host tissues.

(A and B) Proteome comparison of parental and ΔvapC22 strains of M. tuberculosis. (A) Volcano plots represent proteome comparisons of the mid-log phase cultures of ΔvapC22 to the parental strain. The number of proteins compared is mentioned in the bottom-right side of the plot. The statistically significant differentially expressed proteins are highlighted as red (increased) and blue (decreased) dots, respectively. The y and x axes depict P value and fold change for each protein, respectively. (B) The number of differentially expressed proteins in ΔvapC22 strain is categorized by their functional category. (C) Proteome comparison of M. tuberculosis strains harboring either vector or VapB22 overexpression construct. Volcano plot representing proteome comparison of mid-log phase cultures from the parental and VapB22 overexpression strains. The number of proteins identified is mentioned in the bottom right side of the panel. The statistically significant differentially expressed proteins are highlighted as red (increased) and blue dots (decreased), respectively. The y and x axes depict P value and fold change for each protein, respectively. (D and E) Overexpression of VapB22 increases susceptibility of both M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG upon exposure to oxidative stress. Various M. tuberculosis (D) and M. bovis BCG (E) strains were exposed to oxidative stress, and CFU enumeration was performed. The results shown in these panels are means ± SE of log10 CFU obtained from three independent experiments. Statistically significant differences were observed for the indicated groups (paired-two tailed t test, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). (F to K) The M. tuberculosis VapB22 overexpression strain is attenuated for growth in guinea pigs and immunocompetent mice. (F) Representative image of the lungs and spleens of guinea pigs infected with parental and overexpression strains at 4 and 8 weeks after infection via aerosol route. Photo credit: Sakshi Agarwal, Translational Health Science and Technology Institute. (G and H) The growth of parental and overexpression strains in guinea pigs was assessed by determining lung and splenic bacillary loads at 4 weeks (G) and 8 weeks (H) after infection. The data shown in these panels are means ± SE of log10 CFU obtained from six or seven animals per group per time point. (I) For histopathology analysis, H&E-stained sections of lungs infected with parental and overexpression strain were viewed at a magnification of ×40. Scale bars, 200 μm. Photo credit: Ashok Mukherjee, National Institute of Pathologist. (J) The total granuloma score in H&E-stained sections from guinea pigs infected with various strains was determined. The data shown in this panel are means ± SE of data obtained from six or seven animals per group. (K) Female Balb/c mice were infected with wild-type and VapB22 overexpression strain, and CFU counts were determined in the lungs at 4 and 8 weeks after infection. The data shown in this panel in means ± SE of log10 CFU obtained from five mice per group per time point. Statistically significant differences were obtained for the indicated groups (paired-two tailed t test, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01).

We next hypothesized that increased expression of VapB22 might be associated with the in vitro and in vivo growth defects associated with the mutant strain. Thus, to investigate the contribution of increased expression of VapB22 in ΔvapC22 deletion–associated phenotype, we constructed VapB22 overexpression strain and compared its survival to the parental strain upon exposure to oxidative stress and in host tissues. The construction of VapB22 overexpression strain was confirmed by MS analysis. As shown in Fig. 3C, the expression of VapB22 was increased by ~2.5-fold in the overexpression strain. The increased expression of VapB22 in ΔvapC22 and VapB22 overexpression strain was also confirmed by qPCR using gene-specific primers. In correlation with the proteome data for the ΔvapC22 mutant strain, the expression of both EsxA and EsxB was also reduced in the VapB22 overexpression strain in comparison to the empty vector (Fig. 3C). In addition to these, the levels of enzymes involved in PDIM biosynthesis [Rv2935 (PpsE), Rv2936 (DrrA), and Rv2939 (PapA5)] and oxidative stress response [Rv2428 (AhpC)] were also decreased in the VapB22 overexpression strain (Fig. 3C) (30). We observed that growth patterns of M. tuberculosis strain harboring either pVV16 or pVV16-vapB22 were comparable in Middlebrook 7H9 medium in vitro. However, in concordance with the phenotype observed for ΔvapC22 strain, we show that overexpression of VapB22 enhanced the M. tuberculosis susceptibility by ~32-fold and 7-fold upon exposure to oxidative stress for 6 and 24 hours, respectively, in comparison to the parental strain (*P < 0.05; Fig. 3D). Further, we also show that overexpression of VapB22 increased the killing of M. bovis BCG by ~200-fold and 50-fold upon exposure to oxidative stress for 6 and 24 hours, respectively (**P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05; Fig. 3E). As expected, the M. bovis BCG ΔvapC22 mutant strain also displayed a growth defect of approximately 11-fold at both 6 and 24 hours of exposure to oxidative stress (**P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05; Fig. 3E). These observations show that levels of VapB22 regulate resistance to oxidative stress in both M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG.

VapB22 overexpression reduces virulence of M. tuberculosis

We next hypothesized that whether overexpression of VapB22 affects the survival of M. tuberculosis upon exposure to oxidative stress, likewise, the virulence of overexpression strain might also be compromised in vivo. To evaluate our hypothesis, we compared the growth kinetics of parental and VapB22 overexpression strain in aerosol-infected guinea pigs at both 4 and 8 weeks after infection. The aerosol infection resulted in implantation of approximately 50 bacilli in the lungs of both groups at day 1 after infection. Tissue gross pathological analysis revealed that the lungs and spleens of guinea pigs infected with VapB22 overexpression strain displayed reduced tubercles as compared to wild-type strain–infected guinea pigs (Fig. 3F). We observed that at 4 weeks after infection, the lung bacillary loads in guinea pigs infected with VapB22 overexpression strain was reduced by ~3-fold in comparison to parental strain–infected guinea pigs (*P < 0.05; Fig. 3G). This growth defect was more prominent in spleens as the bacillary load was reduced by 40-fold in VapB22 overexpression strain–infected guinea pigs in comparison to animals infected with the parental strain (**P < 0.01; Fig. 3G). However, at 8 weeks after infection, the lung and splenic bacillary loads in VapB22 overexpression strain were reduced by 7-fold and 130-fold, respectively, in comparison to parental strain–infected guinea pigs (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01; Fig. 3H). Histopathology analysis revealed that the lung sections from guinea pigs infected with VapB22 overexpression strain displayed fewer granulomas and more alveolar space in comparison to parental strain infected guinea pigs at 8 weeks after infection (Fig. 3I). The corresponding sections from parental strain–infected guinea pigs displayed heavy tissue damage and large necrotic granulomas surrounded by epithelial cells and lymphocytes (Fig. 3I). The total granuloma score in lung sections of animals infected with overexpression strain at 8 weeks after infection was ~3-fold less in comparison to parental strain–infected guinea pigs (*P < 0.05; Fig. 3J). However, the granuloma score was comparable in both groups at 4 weeks after infection (Fig. 3J).

Further, we compared the growth kinetics of M. tuberculosis parental and overexpression strains in the lungs of aerosol-infected mice. We observed that the lung bacillary load was comparable between parental and VapB22 overexpression strain–infected mice at 4 weeks after infection. However, at 8 weeks after infection, the bacterial loads in overexpression strain–infected mice were reduced by fourfold in comparison to animals infected with parental strain (**P < 0.01; Fig. 3K). These results suggest that relative levels of VapB22 and VapC22 regulate the ability of M. tuberculosis to adapt to oxidative stress and establish infection in host tissues.

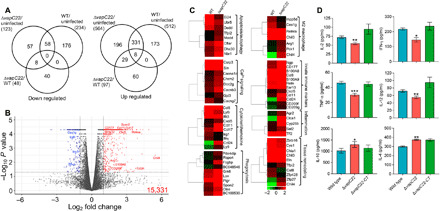

Differential gene expression in the lungs of mice infected with parental and ΔvapC22 strain

To further delineate the mechanisms associated with the attenuated phenotype of the mutant strain, total RNA was isolated from lung tissues of uninfected, wild type–infected, and ΔvapC22-infected mice and subjected to transcriptome analysis. The transcripts with an adjusted Padj < 0.05 and a fold change of ≤2.0 or ≥2.0 were considered as differentially expressed genes. Using this cutoff, we observed that approximately 746 and 687 genes were differentially regulated between the groups of uninfected versus wild type–infected and uninfected versus ΔvapC22-infected mice, respectively (Fig. 4A; fig. S4, A to D; and tables S4 and S5). In comparison to uninfected mice, infection with ΔvapC22 strain resulted in 564 increased and 123 reduced transcript levels (Fig. 4A; fig. S4, A and C; and table S4). Further, approximately 512 and 234 transcripts were increased and decreased, respectively, in lung tissues in wild type–infected mice as compared to uninfected mice (Fig. 4A; fig. S4, B and D; and table S5). Among these differentially expressed genes, 58 repressed and 339 increased transcripts were common in both groups (Fig. 4A). We also observed that approximately 145 genes were differentially expressed in lung tissues of mice infected with parental and ΔvapC22 strain at 4 weeks after infection (Fig. 4, A and B). Among these, in comparison to wild type–infected animals, the transcript levels of 48 and 97 genes were significantly reduced and increased, respectively, in ΔvapC22 mutant–infected mice (Fig. 4, A and B, and table S6).

Fig. 4. Global transcriptome profile and immune response of lung tissues from uninfected mice and from mice infected with either wild-type or ΔvapC22 strain of M. tuberculosis.

(A) Venn diagram showing correlation of expression profiles obtained from lung tissues of uninfected, wild type (WT)–infected, and ΔvapC22-infected mice. (B) The volcano plot showing comparison of gene expression profiles from mice infected with parental and ΔvapC22 strain of M. tuberculosis. The genes that are significantly up-regulated or down-regulated by more than 2.0-fold have been highlighted as blue and red dots, respectively. The y and x axes depict P value and fold change for each gene, respectively. (C) Heat map showing transcripts differentially expressed by 4.0-fold in lung tissues of mice infected with wild-type and ΔvapC22 strain after 4 weeks of infection. The gene names and pathways are indicated to the right of heat map, and growth conditions are mentioned at the top. The data shown are obtained from three biological replicates. (D) The levels of intracellular cytokines in lung homogenates from 4-week infected mice were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Significant differences were obtained for the indicated groups (paired-two tailed t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

We observed that in comparison to parental strain–infected lung tissues, the transcripts of proteins implicated in either apoptosis (Madd, Cflar, Dhx30, and Tfpi2) or autophagy (Nbr1) were induced in lung tissues of animals infected with the mutant strain (Fig. 4C). Moreover, we observed that the transcripts related to calcium signaling pathways such as (Cacna1d, Cacnb3, Chrm2, Csrp3, Gjd3, Doc2g, and Sln) were also enriched in mRNA isolated from mutant strain–infected mice (Fig. 4C). These observations are in agreement with previous studies, which report that Ca2+ signaling is a major regulator of autophagy and intracellular calcium levels increase at later stages of apoptosis (Fig. 4C) (32). The transcripts involved in the influx of neutrophils (CD177 and CXCL5), their activation (S100A8/A9), and genes involved in antimicrobial defense and phagocytosis (Retn and Ngp) were increased in mutant strain–infected mice (Fig. 4C) (33–35). In addition, the expression of chemokines required for chemotaxis and the activation of eosinophils such as CCL24 and CCL8 were enhanced in lungs of mutant strain–infected animals (Fig. 4C) (36) (37). The expression of transcripts encoding DC-SIGN (Dendritic Cell-Specific Intercellular adhesion molecule-3-Grabbing Non-Integrin) (CD209f and CD209g), a receptor involved in M. tuberculosis binding and its internalization by human dendritic cells, was also increased in the mutant strain–infected mice (Fig. 4C) (38). Together, our data indicate that the host immune response in mice infected with ΔvapC22 strain is dominated by increased infiltration of neutrophils, dendritic cells, and eosinophils in comparison to the animals infected with the parental strain.

Several reports have shown that engulfment of apoptotic bodies by neutrophils and dendritic cells is an essential component of the innate immune response against intracellular bacteria (39). In agreement, we observed that the expression of receptors implicated in phagocytosis of apoptotic infected cells (efferocytosis) such as respondin receptor (Rspo4), immunoglobulin receptors (Pigr), Spondin 2 (Spon2), Grk6, Lox, and α2-microglobulins (BC048546 and BC100530) was increased in lung tissues of ΔvapC22-infected mice (Fig. 4C) (40–43). In our RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) detailed analysis, we notably noticed that transcripts specific for M2 macrophages such as Ym2/Chil4, Ym1/Chil3, Arg1, and Fizz1/Retnla were significantly induced in lung tissues of mice infected with the mutant strain (Fig. 4C). M2 macrophages are efferocytic-high macrophages that play an essential role in the clearance of apoptotic cells to maintain homeostasis (44). In concordance, we noticed that the transcripts encoding for matrix metalloproteases such as MMP12, MMP9, and MMP8 were induced in lung tissues of mice infected with ΔvapC22 strain (Fig. 4C). Matrix metalloproteases are essential for granuloma formation and involved in tissue remodeling and inflammation during acute stage of infection (38). Moreover, the transcript levels of genes involved in tissue repair such as elastins (eln) and chitinase-like proteins (chil3, chil4, and chia1) were increased in ΔvapC22 strain (Fig. 4C) (45–48). Since inflammation is a hallmark of M. tuberculosis infection in host tissues, as expected, various transcripts for host immunomodulatory proteins and tissue repair were induced in lung tissues of ΔvapC22-infected mice. These observations suggest a strong correlation between the regulation of inflammation and outcome of infection.

Next, we assessed the expression of TH1 response markers in the transcriptomics data obtained from lung tissues of mice infected with either parental or ΔvapC22 mutant strain. We noticed that the interferon-γ (IFN-γ) transcript levels were reduced in lung tissues of ΔvapC22-infected mice in comparison to mice infected with the parental strain (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, in comparison to the parental strain, the expression of the lymphocyte antigen 6 (LY6i) gene, a maturation marker for T and B lymphocytes, was also reduced in the mutant strain (38). In agreement, chemokines involved in eosinophils recruitment and tissue repair such as CCL8, CCL11, CCL17, and CCL24 were significantly induced in lungs of ΔvapC22-infected mice (49). However, the expression of lymphocyte antigen 9 (Ly9), a protein involved in peripheral tolerance that negatively regulates immune response was higher in lung tissues of ΔvapC22-infected mice (Fig. 4C) (50). Together, these observations suggest that innate immune mechanisms are able to clear ΔvapC22 in vivo, whereas wild-type M. tuberculosis resists innate immune response and proliferates inside the host tissues.

Reduced levels of proinflammatory cytokines in lungs of ΔvapC22-infected mice

On the basis of our RNA-seq data, we hypothesized that attenuation of ΔvapC22 strain in vivo might be associated with dampened levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Further, to delineate the mechanism associated with faster clearance of ΔvapC22 strain in host tissues, we quantified cytokine levels in lung homogenates of mice infected with various strains at 4 weeks after infection (Fig. 4D). We observed that infection with ΔvapC22 strain induced a significantly lesser magnitude of proinflammatory cytokines in comparison to mice infected with the parental strain. These proinflammatory cytokines included interleukin-2 (IL-2), IFN-γ, IL-12, and tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001; Fig. 4D). Our findings suggest that proinflammatory immune response is reduced in mice infected with the mutant strain in comparison to parental strain infected animals. Previous studies have shown that the increased expression of TH2-related cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 protects the host from excessive tissue damage (51). In concordance with our RNA-seq data, we observed that the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4 and IL-10, were increased in homogenates from ΔvapC22-infected mice as compared to wild type–infected mice (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01; Fig. 4D). Together, we speculate that reduced expression of virulence-associated proteins in ΔvapC22 strain might be responsible for the observed reduced TH1 immune response and in vivo attenuation.

DISCUSSION

TA systems have been postulated to be involved in (i) protection against bacteriophages, (ii) drug tolerance, (iii) stress adaptation, (iv) biofilm formation, and (v) pathogenesis (3, 52, 53). Despite their vast expansion, very few studies have been performed to decipher the contribution of TA systems in M. tuberculosis physiology and pathogenesis. Previously, we have shown that MazF toxins function cumulatively and are essential for M. tuberculosis to establish disease in guinea pigs (16). We have also shown that VapBC3, VapBC4, and VapBC11 TA systems are indispensable for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis in guinea pigs (17, 18). Here, we have functionally characterized the VapBC22 TA system from M. tuberculosis.

In agreement with previous studies, we show that induction of a functional VapC22 resulted in growth arrest and nucleoid condensation in M. smegmatis (17). The growth inhibition associated with VapC22 in M. bovis BCG was abrogated upon mutation of the aspartic acid residue of the PIN domain with alanine. RNA-seq analysis revealed that overexpression of VapC22 results in transcriptional reprogramming and the expression profiles were similar to those obtained in bacilli upon exposure to either nutrient limiting or low oxygen growth conditions (22, 24). This reprogramming might be associated with increased expression of various transcription factors (whib7, furA, sigE, whib1, and lsr2), ribosomal proteins, and noncognate toxins. Among noncognate toxins, in agreement with our previous studies, we observed that vapC15, higB1, and mazF6 transcripts were significantly induced in vapC22 overexpression strain of M. tuberculosis (17). We observed that the deletion of VapC22 did not alter the colony morphology and ability of M. tuberculosis to form biofilms in vitro. However, the growth rates of the mutant strain were significantly higher in comparison to the parental strain in vitro.

The induction in the transcript levels of toxins belonging to TA systems under numerous stress conditions such as oxidative, nitrosative, nutrient limitation, and low oxygen suggest the plausible role for TA systems to enable stress adaptation (12, 17). Despite being induced upon exposure to nutrient limiting and low oxygen growth conditions, the survival pattern of wild-type and ΔvapC22 strain was comparable under these conditions and other in vitro stress conditions such as nitrosative, detergent, and drugs. Unlike other in vitro stress condition, we observed that the deletion of vapC22 enhances the susceptibility of M. tuberculosis toward oxidative stress. The increased killing of ΔvapC22 upon exposure to oxidative stress could be attributed to the accumulation of branched chain amino acids as reported in the case of TA deficient triple mutant strain of M. smegmatis or reduced expression of genes involved in adaptation to oxidative stress (54). TA systems have been demonstrated to be essential to establish infection in the host for various microbial pathogens (3, 16–18). Notably, the ΔvapC22 strain was also markedly defective in establishing lung infection in mice and guinea pigs. In concordance, H&E-stained sections from parental strain–infected guinea pigs showed severe chronic inflammation with higher cellular infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages. In addition, reduced cellular inflammation with normal parenchyma was observed in mutant strain–infected tissues sections. These results are in concordance with previous studies that have reported attenuated phenotype of M. tuberculosis mutants that are susceptible to oxidative stress (55, 56). These experiments implicate that VapC22 plays an important role in the virulence of M. tuberculosis.

To further unravel the mechanisms associated with the severe attenuation of ΔvapC22 strain in host tissues, we compared the total proteome of mid-log phase cultures of wild-type and ΔvapC22 strain grown in vitro. We observed that expression of proteins belonging to ESX-1 or ESX-V type VII secretion system of M. tuberculosis was significantly reduced in the mutant strain (28). In addition to these, we also observed that proteins required for mycolic acid biosynthesis were also repressed in the mutant strain (29). The expression of PrpC, the protein involved in PDIM biosynthesis, was reduced in the mutant strain (57). We also noticed that the expression of proteins adjacent to VapC22 such as VapB22 and EchA16 were increased in the mutant strain. Since vapB22 transcripts were not degraded by purified VapC22 toxin, we hypothesize that VapC22 in complex with VapB22 represses the transcription from their own promoter. Previously, it has been shown that in addition to autoregulation, antitoxins are able to regulate the expression of stress response and virulence-associated genes (4, 58, 59). Therefore, we hypothesized that the increased expression of VapB22 in the mutant strain might be responsible for the enhanced oxidative stress–mediated killing and in vivo–attenuated phenotype of the mutant strain. As observed in the case of MqsA antitoxin, we also demonstrate that ectopic expression of VapB22 increased the susceptibility of M. tuberculosis upon exposure to oxidative stress (59). In addition, the increased expression of antitoxin attenuated M. tuberculosis growth in both mice and guinea pigs. We observed that the expression of AhpC (involved in oxidative stress response) and proteins belonging to the ESX-1 secretion pathway or involved in PDIM biosynthesis was reduced in the VapB22 overexpression strain. Previously, it has been shown that M. tuberculosis strains with deletions in either EsxA/EsxB or PDIM biosynthesis are attenuated for growth in vivo and both these pathways work in a coordinated manner to subvert host antimicrobial pathways (60–62). These results suggest that the observed in vivo growth defect in ΔvapC22 and VapB22 overexpression strain might be associated with a network of signaling events that involves various virulence-associated factors of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 5). Further, ESX-1 has been demonstrated to enhance bacterial replication by promoting necrosis of host cells (63).

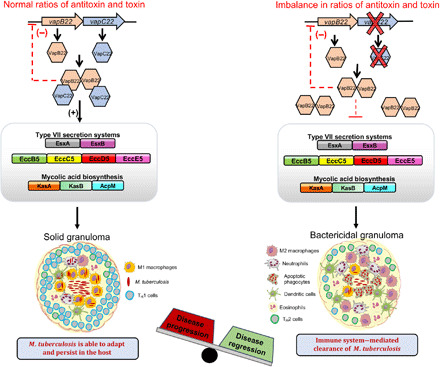

Fig. 5. Proposed model for regulation of virulence by VapBC22.

The imbalance in the relative levels of both VapC22 and VapB22 results in reduced expression of various virulence proteins. The virulence-associated proteins such as ESX-I, ESX-V, KasA, KasB, and AcpM modulate host immune response to enhance replication of intracellular M. tuberculosis. In agreement, the transcripts involved in innate immune responses as evident by induction of apoptosis, recruitment of M2 macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells were enhanced in mice infected with ΔvapC22 strain. We propose that the repression of virulence-associated proteins in ΔvapC22 and VapB22 overexpression strain is associated with their faster clearance by the innate immune response resulting in reduced immunopathology.

To gain further mechanistic insights into the faster clearance of the mutant strain in host tissues, we compared global responses of lung tissues upon infection with either wild type or ΔvapC22 after 4 weeks. RNA-seq analysis revealed that in comparison to parental strain–infected animals, infection with ΔvapC22 mutant strain resulted in increased transcript levels of genes involved in autophagy, apoptosis, phagocytosis, and efferocytosis. This clearance of apoptotic cells by noninfected phagocytes has been shown to be beneficial for host defense and subsequent killing of mycobacteria (63). In addition, the transcripts belonging to calcium signaling pathways that are reported to induce apoptosis or autophagy were also increased in lungs of ΔvapC22-infected mice. Transcriptomic results revealed that various markers involved in recruitment and activation of M2 macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and eosinophils were expressed higher in the lungs of mutant-infected animals. These results implicate that influx of innate immune cells to the site of infection might be responsible for faster clearance of mutant strain in host tissues. Further, increased levels of transcripts implicated in tissue remodeling such as matrix metalloproteases, chitinase-like proteins, and inflammation control are also in line with reduced bacterial loads from ΔvapC22-infected mice at 4 weeks after infection. Our data are in agreement with previous reports, showing that inflammation of tissues correlates with severe disease and higher bacterial burdens in host tissues (64). Previously, it has been shown that infection with virulent strain induces a strong TH1 immune response and this leads to lymphocyte recruitment to the site of infection resulting in granuloma formation (65). In addition, the strains with deletion in either mycolic acid biosynthesis or ESX-1 have been reported to induce weaker TH1 immune response in macrophages as compared to the parental strain (66, 67). In support of reduced immunopathology, we also observed suppressed levels of proinflammatory cytokines in lung homogenates from mutant-infected mice. Further, the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines were increased in homogenates from ΔvapC22-infected mice. The production of IL-10 and IL-4 by macrophages has been shown to be essential for apoptotic cells recognition and efferocytosis (68, 69). Our observations are also in accordance with previous reports that phagocytosis of apoptotic cells is associated with the induction of an anti-inflammatory tissue repair gene signature (70).

Together, this is the first study investigating the role of VapBC22 TA systems in the stress adaptation and virulence of M. tuberculosis. RNA-seq analysis revealed that overexpression of VapC22 results in transcriptional reprogramming that mimics the bacterial response to nutritional stress or hypoxia. We show that the relative levels of VapB22 and VapC22 are essential for M. tuberculosis to adapt to oxidative stress and establish infection in the host. The data presented in this study indicate that in mice infected with ΔvapC22 strain, the enhanced microbicidal activities of innate immune cells are responsible for faster clearance of intracellular bacteria. We speculate that the decreased expression of various virulence-associated proteins might be responsible for reduced bacterial loads and lung pathology in guinea pigs infected with the ΔvapC22 mutant and VapB22 overexpression strain. We conclude that regulation of the VapBC22 TA system is essential for M. tuberculosis to establish infection in the host and compounds that could target VapC22 might be good candidates for therapy against both drug-susceptible and drug-resistant M. tuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions and plasmids

M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. bovis BCG, M. smegmatis mc2155, E. coli HB-101, Rosetta DE3, and XL-1 Blue strains were used in the present study. The bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in the study are listed in table S1. Culturing of mycobacterial strains was performed in Middlebrook 7H9 medium containing 0.2% glycerol, 0.05% Tween 80, and supplemented with 1× albumin dextrose saline at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cultures of E. coli were grown in LB medium at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. When required, the antibiotics were added at the following concentration: kanamycin (25 μg/ml) for both E. coli and mycobacteria, ampicillin (50 μg/ml) for E. coli, tetracycline (10 μg/ml) for E. coli, and hygromycin (150 and 50 μg/ml, respectively) for E. coli and mycobacteria. All chemicals used in the study unless mentioned were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, Merck.

Growth inhibition and fluorescence microscopy experiments

The construction of Atc-inducible VapC overexpression strains has been described previously (17). For growth inhibition assays, early-log phase cultures of various recombinant strains were induced by the addition of Atc (50 ng/ml). Nucleoid condensation and LIVE/DEAD staining experiments in M. smegmatis and M. bovis BCG, respectively, were performed as previously described (17, 18). The images of stained bacilli were captured using FV3000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan) equipped with a 100× objective.

Cloning and purification of VapB22, VapC22, and VapBC22

The amplified vapB22 fragment was cloned in pET28b to yield recombinant protein with thrombin cleavable N terminus hexahistidine-tag. For the expression of VapC22, the vapC22 gene fragment was cloned in a modified pBAD/Myc-His vector. For the purification of VapBC22 complex, vapC22 and vapB22 were cloned in MCS (multiple cloning site)–1 and MCS-2 of pETDuet-N, respectively (21). All these constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. For protein purification, various constructs were transformed into E. coli Rosetta DE3, and transformants were selected on plates containing appropriate antibiotics. For VapB22 protein expression, the secondary culture was grown at 37°C till the optical density at 600 nm (OD600nm) reached ~0.6 and induced by the addition of 0.3 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 14 hours at 16°C with constant shaking. For VapBC22 complex purification, the culture at an OD600nm of ~0.6 was induced using 0.3 mM IPTG for 4 hours at 37°C. For the purification of VapC22 toxin, the culture was induced at an OD600nm of ~0.5 by the addition of 0.2% l-arabinose at 37°C for 2 hours. The recombinant proteins were purified using HIS-Select Nickel Affinity chromatography as described previously (18, 21). The purified fractions were concentrated, dialyzed, and stored at −80°C for further biochemical assays.

AUC of VapB22, VapC22, and VapBC22

AUC experiments were performed using Beckman-Coulter XL-A centrifugation machine equipped with TiAn50 eight-hole rotor at 25°C at 40,000 rpm. The AUC experiments were performed in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl using 15 μM protein samples, and scans were taken at 280-nm wavelength at 3-min interval. The collected data were fitted using continuous distribution c(s) model in SEDFIT (71). The solvent viscosity and density at 25°C were calculated using SEDNTERP stand-alone software.

In vitro transcription and ribonuclease assays

For in vitro transcription assays, PCR amplification was performed using gene-specific primer pairs. Approximately 200 ng of eluted PCR product was used in setting up a 40-μl in vitro transcription reaction as per the manufacturer’s protocol (New England Biolabs). The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 4 hours, followed by addition of ribonuclease-free deoxyribonuclease (DNase) (Promega) for 1 hour. The protein was removed by phenol-chloroform extraction. RNA was precipitated, washed, air-dried, and resuspended in nuclease-free water. In vitro ribonuclease reactions were performed using either 1 μg of MS2 RNA or 100 ng of transcribed RNA and 10 μM VapC22 protein in 1× cleavage buffer [10 mM Hepes (pH 8.0), 15 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM MnCl2]. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for specified time points, inactivated with the addition of formamide RNA loading dye, and heated at 70°C for 5 min. The reactions were resolved on urea-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (UREA–PAGE) in 1× tris-boric acid–EDTA buffer and visualized by EtBr staining.

RNA-seq experiments

Total RNA was isolated from M. tuberculosis harboring pTetR or pTetR-vapC22 grown in the presence of Atc for 24 hours. The induced cultures were harvested, washed, and resuspended in 1 ml of TRIzol. Total RNA was extracted using QIAGEN RNeasy kit as previously described (72). RNA was eluted in nuclease-free water, subjected to TURBO DNase treatment for removing DNA, and sequenced at AgriGenome Labs Pvt. Ltd. (India) on an Illumina HiSeq platform as previously described (18). For data analysis, limma package installed in R programming language was used to identify differential expressed genes in M. tuberculosis upon VapC22 overexpression. Sequenced and quality-controlled raw reads were mapped to M. tuberculosis assembly H37Rv.ASM19595v2.42 reference genome downloaded from Ensembl (http://bacteria.ensembl.org/) using TopHat2 pipeline. Gene-level summarization of mapped reads was performed using Rsubread package. The counted reads for each gene were then normalized using a TMM (trimmed mean of M-values) algorithm implemented in the edgeR package and subsequently converted to gene expression using limma software. The differential expression analysis between M. tuberculosis strains harboring the vector or pTetR-vapC22 was performed using limma providing two matrices: design matrix, which described experimental layout, and a contrast matrix, which performed the desired statistical test.

Generation of various mutant, complemented, and overexpression strains

For construction of mutant strain, approximately 800-bp upstream and downstream region of vapC22 was amplified and cloned into pYUB854 flanking hygromycin resistance gene resulting into pYUB854ΔvapC22 (73). The recombinant cosmid was Pac I–digested and packaged in phagemid DNA, phAE87, and the recombinant phAE87ΔvapC22 was electroporated in M. smegmatis to generate temperature-sensitive mycobacteriophages (73). The construction of ΔvapC22 strain of M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis was verified by Southern blot and qPCR. The complemented strain was constructed by amplifying vapBC22 along with 500 bp of upstream region and cloned into pMV306K, an integrative mycobacterial expression vector. The recombinant plasmid pMV306K:vapBC22 was electroporated into ΔvapC22 strain. The VapB22 overexpression strain was constructed by amplifying open reading frame for vapB22 and cloning the PCR product in mycobacterial expression vector, pVV16, under the control of hsp65 promoter. The final construct, pVV16:vapB22, was introduced into M. bovis BCG or M. tuberculosis.

Stress experiments

For stress experiments, early-log phase cultures (OD600nm, ~0.2 to 0.3) were subsequently exposed to either 5 mM H2O2 in Middlebrook 7H9 medium for 6 hours or 1 day or 5 mM NaNO2 in 7H9 medium (pH 5.2), 0.1% SDS, or lysozyme (2.5 mg/ml) for 3 days. For starvation experiments, early-log phase cultures were harvested, washed, and cultured in 1× tris-buffered saline–Tween 80 for 14 days. For biofilm experiments, mid-log phase cultures (OD600nm, ~0.8 to 1.0) were diluted in detergent free Sauton’s medium in six-well plates, parafilm sealed and incubated at 37°C for 4 to 5 weeks without shaking. The MIC of different drugs was also determined using the microdilution method as previously described (74). The drug tolerance experiments were performed by exposing mid-log phase cultures of various strains to 10× MIC99 concentration of either isoniazid or rifampicin for 14 days. The bacterial enumeration after exposure to these conditions was determined by plating 100 μl of 10-fold serial dilutions on Middlebrook 7H11 medium.

Proteomics experiments

For proteome analysis, various strains were grown till mid-log phase (OD600nm, ~0.8) at 37°C. The bacterial cultures were harvested, washed with 1× phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM triethyl ammonium bicarbonate buffer, 2% SDS, and 1× protease inhibitor). The bacterial samples were lysed using a bead beater, and clarified lysates were prepared as per standard protocol. Two hundred micrograms of protein from each sample was reduced using 5 mM dithiothreitol and alkylated using 15 mM iodoacetamide. The protein samples were acetone precipitated, washed with ice-cold acetone, and subjected to trypsin digestion. Equal amount of peptides from each sample were labeled with 10-plex TMT (tandem mass tags) reagents as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The labeled peptides from all samples were pooled, cleaned using C18 stage tips, concentrated, and subjected to liquid chromatography-MS/MS analysis on Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer interfaced with an EASY-Spray nanoLC (nLC1000) platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Briefly, peptides were trapped on a precolumn setup (Thermo Scientific Acclaim Pepmap 100, 75 μm × 2 cm, 3-μm C18, 100 Å) using solvent A (5% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid), followed by a high-resolution separation using an analytical column (Thermo Scientific Acclaim PepMap RSLC, 75 μm × 50 cm, 2-μm C18) and a gradient of solvent B (95% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) from 8 to 35% and analyzed in Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer using a cycle time of 3 s and a total run time of 180 min. In MS scans, precursor ions in the mass range of 350 to 1600 mass/charge ratio were recorded with an Orbitrap mass analyzer at 120K resolution, 4 × 105 AGC (Automatic gain control) target and 30-ms injection time. MS/MS fragmentation was performed using high-energy collision-induced dissociation [34% stepped NCE (normalized control energy)]. Fragment ions were analyzed in Orbitrap mass analyzer with 100-ms injection time and 1 × 105 AGC target. A total of 50K resolution was used for fragment ion scan to enable high-resolution separation of TMT reporter ions. Samples were analyzed in technical quadruplicates. Raw files were imported into Proteome Discoverer 2.1 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), and MS/MS search was performed using SEQUEST search algorithm with M. tuberculosis protein database. Database search parameters included trypsin as the protease, two missed cleavages allowed, and 10 parts per million and 0.02 Da as precursor and fragment ion tolerance, respectively. The oxidation of methionine was selected as dynamic modification and carbamidomethylation on cysteine and TMT modification at N terminus, and lysine was used as a fixed modification. False discovery rate was set to 1% at peptide level.

In vivo experiments

The experiments involving use of mice or guinea pigs were approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Translational Health Science and Technology Institute (THSTI), Faridabad and International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), New Delhi, India. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of committee for the purpose of supervision of experiments on animal guidelines. For aerosol infection, single-cell suspension of mid-log phase cultures was prepared containing 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml, and animals were infected with 50 to 100 CFU using a Madison aerosol machine at Tuberculosis aerosol challenge facility, ICGEB. For bacterial enumeration, the lungs and spleens were homogenized in 2 ml of normal saline, and 10.0-fold serial dilutions were plated. For histopathology analysis, 10% formalin-fixed lung tissues were stained with H&E, and extent of tissue damage was determined by a pathologist as previously described (72, 75).

Cytokine measurements

The levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, and TNF-α were measured in filtered supernatants of lung homogenates using Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine TH1/TH2 assay kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Host RNA-seq analysis

For transcriptome analysis, lung tissues of uninfected (naive) and 4-week infected wild-type and ΔvapC22 mice were homogenized by bead beating, and total RNA was isolated using QIAGEN RNeasy kit. RNA was eluted in nuclease-free water, subjected to DNA removal using TURBO DNase, and shipped to Bionivid for sequencing. The stringent quality control of paired-end sequence reads of all the samples was performed using NGS QC Toolkit. The paired-end sequence reads with a Phred score of >Q30 were selected for further analysis. Quality score passed reads were then mapped to mouse reference genome sequence (MM10) using TopHat2, while Cufflink software was used for transcript assembly. The transcripts from infected mice were compared with those obtained from uninfected mice using Cuffdiff. The transcripts with a log2 fold change cutoff of 1 and P ≤ 0.05 were considered as significantly differentially expressed. Subsequently, unsupervised hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes was performed using Cluster 3.0 and visualized using Java Tree View v1.1.6. The volcano plots were plotted for the identified genes using enhanced Volcano, an R package version 1.2.0 (https://github.com/kevinblighe/EnhancedVolcano).

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were determined by paired (two-tailed) t test and were considered significant at P < 0.05. GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis and the generation of graphs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the technical staff of Tuberculosis Aerosol Challenge Facility, ICGEB, Infectious Disease Research Facility, THSTI, and Small Animal Facility, THSTI for help during animals and BSL-3 experiments. S.A., A.S., A.D., and H.S. are thankful to Department of Biotechnology for research fellowship. R.B. acknowledges Department of Science and Technology India and FICCI for providing C.V. Raman International fellowship. We thank B. Dhaka for help with sample preparation for proteomics and S. M Pinto for help with acquisition of MS data. We are thankful to R. Dhiman, D. Saini, and P. Kumar for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank A. Mukherjee for histopathology analysis. R. Singh and S. Singh are highly acknowledged for technical help. Funding: R.S., H.G., and R.V. acknowledge the financial support received from Department of Biotechnology (BT/COE/34/15219/2015). R.S. is a recipient of Ramalingaswami fellowship (BT/HRD/35/02/18/2009) and National Bioscience Award (BT/HRD/NBA/37/01/2014). R.S. and K.G.T. acknowledge the funding received from Department of Science and Technology, India (EMR/2016/003728). R.D.S. acknowledges the funding received from Department of Biotechnology (BT/PR27108/BID/7/820/2017). The funders had no role in study design, results analysis, and preparation of manuscript. Author contributions: R.S. conceived the idea and supervised the M. tuberculosis experiments. S.A., A.S., and S.K. performed the M. tuberculosis microbiology experiments. S.A., A.S., and R.B. conducted the guinea pig and mice experiments. R.B. performed the cytokine measurement assays. A.D. performed the biochemical and biophysical experiments. K.K.M. and K.K.D. performed the proteomics experiments. H.S. helped with the analysis of RNA-seq data. Former director, National Institute of Pathologist. R.S., K.G.T., R.D.S., H.G., and R.V. supervised the experiments. R.S., S.A., and R.B. wrote manuscript with inputs from other authors. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The RNA-seq data related that are present in this manuscript is deposited in NCBI-SRA repositories under the project accession code PRJNA595058. The accession IDs are SUB6671571 and SUB6677399 for transcriptomics data from Mus musculus and M. tuberculosis, respectively. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/23/eaba6944/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Schuster C. F., Bertram R., Toxin-antitoxin systems are ubiquitous and versatile modulators of prokaryotic cell fate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 340, 73–85 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandey D. P., Gerdes K., Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 966–976 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobato-Márquez D., Díaz-Orejas R., García-Del Portillo F., Toxin-antitoxins and bacterial virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 592–609 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wen Y., Behiels E., Devreese B., Toxin-antitoxin systems: Their role in persistence, biofilm formation, and pathogenicity. Pathog. Dis. 70, 240–249 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keren I., Shah D., Spoering A., Kaldalu N., Lewis K., Specialized persister cells and the mechanism of multidrug tolerance in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186, 8172–8180 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keren I., Kaldalu N., Spoering A., Wang Y., Lewis K., Persister cells and tolerance to antimicrobials. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230, 13–18 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi Y., Inouye M., Regulation of growth and death in Escherichia coli by toxin-antitoxin systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 779–790 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page R., Peti W., Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacterial growth arrest and persistence. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 208–214 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes F., Kędzierska B., Regulating toxin-antitoxin expression: Controlled detonation of intracellular molecular timebombs. Toxins 6, 337–358 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthuramalingam M., White J. C., Bourne C. R., Toxin-antitoxin modules are pliable switches activated by multiple protease pathways. Toxins 8, E214 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harms A., Brodersen D. E., Mitarai N., Gerdes K., Toxins, targets, and triggers: An overview of toxin-antitoxin biology. Mol. Cell 70, 768–784 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramage H. R., Connolly L. E., Cox J. S., Comprehensive functional analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis toxin-antitoxin systems: Implications for pathogenesis, stress responses, and evolution. PLOS Genet. 5, e1000767 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tandon H., Sharma A., Wadhwa S., Varadarajan R., Singh R., Srinivasan N., Sandhya S., Bioinformatic and mutational studies of related toxin-antitoxin pairs in Mycobacterium tuberculosis predict and identify key functional residues. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 9048–9063 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arcus V. L., McKenzie J. L., Robson J., Cook G. M., The PIN-domain ribonucleases and the prokaryotic VapBC toxin-antitoxin array. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 24, 33–40 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winther K., Tree J. J., Tollervey D., Gerdes K., VapCs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cleave RNAs essential for translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 9860–9871 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiwari P., Arora G., Singh M., Kidwai S., Narayan O. P., Singh R., MazF ribonucleases promote Mycobacterium tuberculosis drug tolerance and virulence in guinea pigs. Nat. Commun. 6, 6059 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal S., Tiwari P., Deep A., Kidwai S., Gupta S., Thakur K. G., Singh R., System-wide analysis unravels the differential regulation and in vivo essentiality of virulence-associated proteins B and C toxin-antitoxin systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 217, 1809–1820 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deep A., Tiwari P., Agarwal S., Kaundal S., Kidwai S., Singh R., Thakur K. G., Structural, functional and biological insights into the role of Mycobacterium tuberculosis VapBC11 toxin–Antitoxin system: Targeting a tRNase to tackle mycobacterial adaptation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 11639–11655 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matelska D., Steczkiewicz K., Ginalski K., Comprehensive classification of the PIN domain-like superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 6995–7020 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendtsen K. L., Xu K., Luckmann M., Winther K. S., Shah S. A., Pedersen C. N. S., Brodersen D. E., Toxin inhibition in C. crescentus VapBC1 is mediated by a flexible pseudo-palindromic protein motif and modulated by DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 2875–2886 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deep A., Kaundal S., Agarwal S., Singh R., Thakur K. G., Crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis VapC20 toxin and its interactions with cognate antitoxin, VapB20, suggest a model for toxin-antitoxin assembly. FEBS J. 284, 4066–4082 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Betts J. C., Lukey P. T., Robb L. C., McAdam R. A., Duncan K., Evaluation of a nutrient starvation model of Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence by gene and protein expression profiling. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 717–731 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boshoff H. I., Myers T. G., Copp B. R., McNeil M. R., Wilson M. A., Barry C. E. III, The transcriptional responses of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to inhibitors of metabolism: Novel insights into drug mechanisms of action. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40174–40184 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rustad T. R., Harrell M. I., Liao R., Sherman D. R., The enduring hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS One 3, e1502 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holden D. W., Errington J., Type II toxin-antitoxin systems and persister cells. mBio 9, e01574 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronneau S., Helaine S., Clarifying the link between toxin-antitoxin modules and bacterial persistence. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3462–3471 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harms A., Fino C., Sørensen M. A., Semsey S., Gerdes K., Prophages and growth dynamics confound experimental results with antibiotic-tolerant persister cells. mBio 8, e01964-17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gröschel M. I., Sayes F., Simeone R., Majlessi L., Brosch R., ESX secretion systems: Mycobacterial evolution to counter host immunity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 677–691 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatt A., Molle V., Besra G. S., Jacobs W. R. Jr., Kremer L., The Mycobacterium tuberculosis FAS-II condensing enzymes: Their role in mycolic acid biosynthesis, acid-fastness, pathogenesis and in future drug development. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 1442–1454 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox J. S., Chen B., McNeil M., Jacobs W. R. Jr., Complex lipid determines tissue-specific replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Nature 402, 79–83 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walters S. B., Dubnau E., Kolesnikova I., Laval F., Daffe M., Smith I., The Mycobacterium tuberculosis PhoPR two-component system regulates genes essential for virulence and complex lipid biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 60, 312–330 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harr M. W., Distelhorst C. W., Apoptosis and autophagy: Decoding calcium signals that mediate life or death. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a005579 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pechkovsky D. V., Zalutskaya O. M., Ivanov G. I., Misuno N. I., Calprotectin (MRP8/14 protein complex) release during mycobacterial infection in vitro and in vivo. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 29, 27–33 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mei J., Liu Y., Dai N., Favara M., Greene T., Jeyaseelan S., Poncz M., Lee J. S., Worthen G. S., CXCL5 regulates chemokine scavenging and pulmonary host defense to bacterial infection. Immunity 33, 106–117 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]