Abstract

Current cancer therapies target a limited set of tumor features, rather than considering the tumor as a whole. Systems biology aims to reveal therapeutic targets associated with a variety of facets in an individual’s tumor, such as genetic heterogeneity and its evolution, cancer cell-autonomous phenotypes, and microenvironmental signaling. These disparate characteristics can be reconciled using mathematical modeling that incorporates concepts from ecology and evolution. This provides an opportunity to predict tumor growth and response to therapy, to tailor patient-specific approaches in real time or even prospectively. Importantly, as data regarding patient tumors is often available from only limited time points during treatment, systems-based approaches can address this limitation by interpolating longitudinal events within a principled framework. This review outlines areas in medicine that could benefit from systems biology approaches to deconvolve the complexity of cancer.

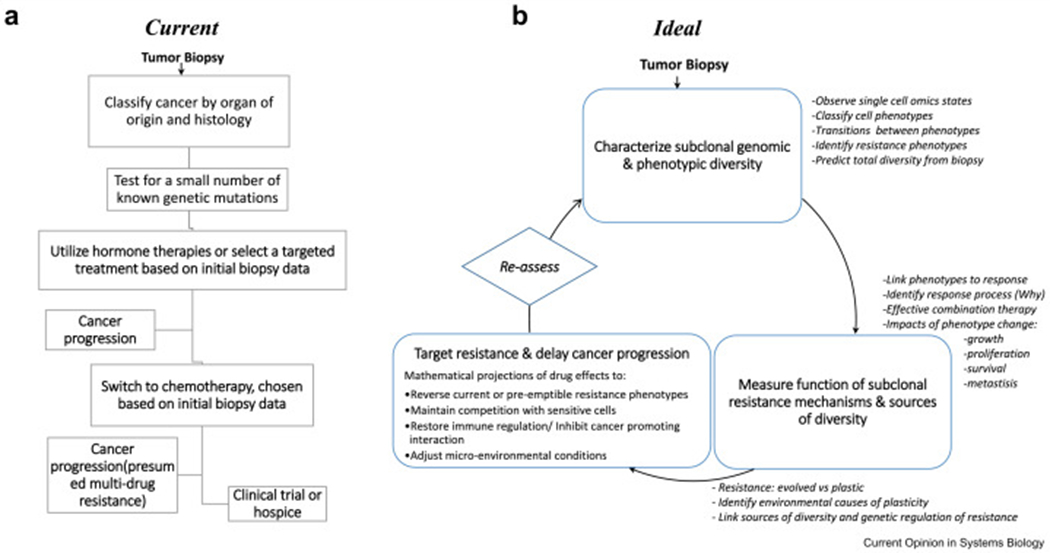

In this review, we seek to highlight two areas in clinical research that appear to be ripe for advancement using systems biology. The first relates to the improved use of data from cancer tissue to inform sequencing, dosing, and combinations of systemic cancer treatments. The second considers the interactions between tumor cells with unique sets of mutations and/or phenotypes, termed “subclones”, and interactions with their tumor-environment. Akin to the study of interacting species in a geographic location, tumor micro-environmental ecology can help to understand the effects on cancer growth and invasion so that cellular dependencies and/or critical means of progression can be therapeutically leveraged. Ultimately, a true systems biology therapeutic approach should include periodic sampling to measure changes in tumor clonal structure and the microenvironment, so that before a patient’s treatment ceases to be effective, a subsequent viable therapy may be identified (Fig. 1). As George Bernard Shaw put it, “The only person who behaves sensibly is my tailor. He takes new measurements every time he sees me. All the rest go on with their old measurements”

Figure 1:

* Legend for figure: (A) flow chart of current process for decision making in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer; (B) Flow chart demonstrating an idealized process for decision making in progressive cancer using systems biology to optimize treatment regiments to directly combat resistant states and heterogeneity. Key tasks to accomplish the understand and treat cancer using a systems biology approach are highlighted (italic text).

Question 1: How to effectively treat heterogeneous tumors whilst preventing or managing the evolution of resistance?

Current opportunities for translational systems biology:

Cancer treatment is currently determined based on organ of origin, histology and relatively few markers. For some cancers, such as prostate adenocarcinoma, papillary serous ovarian cancer, or pancreatic adenocarcinoma, histology is the predominant information used to determine treatment based on population average responses, except if certain hereditary syndromes are present (Fig.1A). For other cancers, treatment is based on a relatively small number of markers, such as ER, PR, and HER2 expression in breast cancer or EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. If genomics is used for treatment decisions, it commonly identifies therapy targeting a single gene mutation. Further, heterogeneity is not considered. Someone with 20% of breast cancer cells expressing estrogen receptors is likely to be treated similarly to a person with 100% of cells expressing estrogen receptor, despite the fact that the composition and thus response of the tumor is likely to be different. Therefore, there is opportunity to improve treatments through assays that can better detail the biology and heterogeneity of the tumor.

In addition to opportunities for personalized care at time of diagnosis, a critical need is to develop treatment strategies that can prevent the emergence of drug resistance. Currently, treatment strategies are reactive and directed at treating the resistant state after it occurs. However, a recent example has demonstrated the power of anticipating the emergence of resistance, and proactively taking steps to inhibit it. Osimertinib is now first-line therapy for EGFR-mutated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). It targets a specific mutation (T790M) which is rarely detected on initial tumor testing, but surfaces after anti-EGFR treatment, conferring resistance. But, treating early with osimertinib either suppresses small resistant subclones or prevents their development of resistance and leads to improved patient survival [1, 2]. Similar strategies may be effective in other cancer types, for example in BRCA1/2 mutation positive ovarian tumors, which often revert back to wild type BRCA1/2 during treatment with PARP inhibitors or platinum based chemotherapy [3].

How could systems biology help achieve the ideal scenario?

Systems biology is aimed at understanding the complexity of cancer in order to better design treatment strategies without requiring direct measurement of every cell and environmental feature at each time point in disease progression. Clearly it is not feasible to frequently re-biopsy patients over time or across different metastatic sites. The clinical needs outlined above could be addressed by studies focused on the following questions: 1) what intra-tumor genetic and phenotypic variability coexists during therapy and how diverse are the phenotypic responses to therapy, 2) what are the recurrent functions of phenotypic changes that confer resistance and what is the prevalence of multidrug resistance versus drug specific resistance mechanisms, and 3) is resistance usually gained and lost rapidly through cellular plasticity or does it gradually evolve, being gained and lost relatively slowly through selective sweeps of a tumor population. In the context of therapy, these questions address the source and diversity of responses that would be expected during a line of treatment, the transferability of resistance between successive lines of therapy, and the speed at which resistance emerges and recedes in the presence or absence of treatment (Fig. 1B).

Characterizing a tumor’s diverse ecosystem and its clonal coexistence in an organism

The majority of clinical tests detect genetic mutations but fail to measure subclonal diversity. However, the extent of subclonal diversity across a tumor and its metastases may be important in determination of drug resistance and phenotypic characteristics, as some clones may respond to therapy while others do not [4]. Further, while drugs commonly target genetic mutations in cancer, opportunity exists to also target phenotypes, independent of genotype. Tumor cell phenotypes are their functional characteristics (e.g. proliferation, motility/migratory capacity, stemness, and others) that result from the interaction of their genotype with the signals received from the environment. Relatively new single cell sequencing techniques are providing the data to characterize the spectrum of cancer phenotypes of individual cells in a tumor, by applying machine learning algorithms or various statistical approaches to single cell imaging and omics datasets [5–7]. Similarly, the developmental continuum of cell states that comprise the phenotypic landscape can be explored using pseudotime reconstruction approaches. The power of this technique comes from assuming that the variation in cell states is representative of cells at time points in their gradual transition from one state to another. As one example, this approach has been applied to reveal the gradual emergence of drug induced resistance through the transition from an epithelial like state to a more mesenchymal phenotype (epithelial-mesenchymal transition; EMT) [8, 9]. The development of phenotypic diversity within a tumor may also be described using state transition models (either Markov chains or PDEs). These methods project the estimated transition rates of cells between phenotypic states through time. As an example, these analyses can predict the emergence of novel intermediate differentiation phenotypes during cancer progression.

In addition to estimation of cell transitions, researchers can use tumor cell sequencing data taken serially to detect characteristics associated with clinical response during a patient’s treatment. One approach uses hierarchical generalized additive regression pathway analysis to identify key predictors of response, whilst accounting for the non-independence of cell phenotypes within a sample [10, 11]. This method acknowledges that patients have random differences in expression, and assumes that the variation is drawn from a common distribution. As an example, this approach can be used to study subclonal evolution within a tumor by assessing how the genotype interacts with the environment to influence subclonal fitness [11]. Further, mathematical approaches based on the Law-Watkinson competition model from ecology have described evolutionary changes in the frequency of competitors over time and quantified rapid genotypic and phenotypic changes the composition of a community [12]. These approaches could be used to model the evolution of intra-tumor genetic variation during treatment, given knowledge of the initial tumor diversity and subclonal fitness and competitiveness.

Lastly, the extent and spatial distribution of intra-tumor heterogeneity remains an open question and its impact on cancer diagnosis and treatment could potentially benefit from more detailed analysis. It is unknown how diverse and spatially organized subclonal populations are within a tumor, and if a single biopsy captures the heterogeneity sufficiently to make treatment decisions. By modeling the spatial relationships between the subclonal/phenotypic diversity and the biopsy volume sampled, one could determine how much of a cancer needs to be sampled to observe all of the clones or phenotypes in the tumor [14]. As a greater fraction of a biopsied tumor is examined, the detected diversity will increase. At first the number detected increases rapidly when the dominant subclones are being encountered. However, the rate of detection decays in a predictable was, as fewer subclones remain undetected. Approaches to estimate total diversity from knowledge of this decaying detection rate with increased effort are reviewed in [15, 16] and applicable methods to estimate diversity are utilized in the fields of genetics, immunology and linguistics [17–19].

Identifying functions of resistance mechanisms and predicting response to therapy.

Clinical decisions can often be tied to patient or clinician preference versus adequate ability to predict the best course of treatment. For example, it is not always clear what order of local therapy (surgery) and systemic therapy will promote the best response in a patient. In stage III ovarian cancer, chemotherapy given before and after surgery leads to an equivalent average survival. Decisions about which patients should get chemotherapy before surgery are often made based on surgeon preference or which provider is seen first, rather than on the patient specific biology of the cancer [20]. In addition, it is not always clear which cancer treatment will work best for individual patients. Ideally, we would be able to associate the information about tumor phenotypes, taken at time of biopsy, to predict a patient’s responses to therapy [21]. One approach to achieve this is to utilize statistical tools to directly correlate phenotypes to response, perhaps using support vector machines [22], convolutional neural networks [23] or regularized Lasso/ridge regression [24]. Currently, only a limited number of the predictive approaches that are being developed have been translated into the clinic (but examples include [25–27]). Ultimately, pre-treatment information alone may not be sufficient. Dynamical models projecting tumor growth and phenotype change over time, incorporate biological knowledge, describe biological processes that occur during therapy (e.g. proliferation, apoptosis and signaling) and can unite phenotypic data from biopsy and follow-up samples. Temporal questions can then be addressed, such as optimal drug timing or dosing, instead of only categorizing patient responsiveness [28, 29].

Heterogeneous subclonal populations within a tumor may respond differently to treatment. For example, our studies and others have shown that tumor subclones with upregulation of multi-drug resistance genes efflux drugs more effectively and survive therapy whereas clones without this upregulation do not [30, 31]. Analysis of acquired resistance phenotypes could be used to guide the choice of future lines of therapy by indicating a) the duration of drug sensitivity before therapy should be switched and b) which second line therapies the induced cells will become most sensitive to [32]. Combination therapies could also be devised that simultaneously target multiple sub-clonal populations with different characteristics. Increasingly, such collateral sensitivity is being identified by using high throughput in vitro screening to train machine learning algorithms to predict the effectiveness of novel drug dose combinations [33]. Alternatively, the drug response and mechanisms of resistance of heterogeneous patient derived samples can be examined in vitro, by studying the growth dynamics of cancer organoids. The growth trajectories can be described using processed based dynamical models, which estimate: i) the rates of key biological processes (e.g. cell proliferation vs death under therapy) and ii) the relative contribution of different biological mechanisms influencing drug response (cell-cell interactions vs direct drug effects) [4]. Both approaches can guide the choice of effective drug combinations that target different subclonal populations (e.g. [34]).

Determining sources of phenotypic variation

Many tumors lack targetable mutations, but emergent phenotypes (for example, signaling driven by transcriptional changes in a cell) provide additional opportunities for therapeutic strategies (see Question 2). Phenotypic plasticity, defined as the ability of individual genotypes to produce different phenotypes, is a common mechanism of resistance both in ecological systems and cancer. Preventing phenotypic plasticity during treatment may prevent or delay emergence of resistance. Interestingly, approaches to blocking adaptation have been used in plants to delay herbicide resistance, including the use of varying herbicide dose or using multiple herbicides together [35].

Mathematical models can identify the relative importance of evolution and plasticity in the emergence of resistance. As one example, variance decomposition approaches [36] such as the Price equation, which partitions the changing frequency of different phenotypes in a population over time into changes: a) linked to the correlation of genotypes and their fitness (evolution) and b) changes correlated with ecological and environmental variables (plasticity). By partitioning the phenotypic plasticity occurring in a range of animal species, Ellner et al. revealed that rapid evolution often opposes the effects of environmental change on traits [36]. Experimentally, the role of evolution versus plasticity is frequently assessed ecologically using the reaction norm approach [37]. The amount of phenotypic variation between subclones (independent of the environment) shows a genetic basis, whilst the environmental effect on phenotypes across clones measures the plasticity effect. By understanding what causes the emergence of resistance, the effectiveness of targeted genetic or environmental therapies can be understood, especially by integrating these selection and signaling mechanisms into gene regulatory networks of resistance [38–43].

Using systems biology to minimize, reverse or bypass resistance

As it is impossible to initiate clinical trials to test all drug combinations, doses, and sequence in patients, the inferences about the tumor cell diversity, interactions and sources of resistance need to be incorporated into dynamical systems models which can forecast the efficacy of many treatment strategies. This allows examination of those regimens with the highest expected chance of success. A successful example is the identification of optimum lapatinib dosing schedules for the treatment of glioblastoma patients [44]. To implement treatment forecasting models that more accurately model tumor diversity, successive detailed insights into the compositional change of many patient’s tumors are needed to calibrate and validate model assumptions. When high levels of intra-tumor genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity are driving the emergence of multiple resistance mechanisms, the order and combination of treatment becomes increasingly important. When a dynamical systems model is available, optimal control theory provides techniques to search through the possible treatment strategies in an attempt to maximize performance, as defined by a set of costs, benefits and limitations [45, 46]

Likewise, systems biology treatment strategies are being developed to prevent disease progression whilst on treatment to minimize exposure to factors that promote emergence. These approaches revolve around modulating the timing of therapy using drug treatment holidays (periodically halting treatment) or adaptive therapy (varying dosage according to tumor status) (e.g. [47]). The success of dose-dense chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer can be seen as an example of applying models to prevent the development of resistance [48]. Decreasing the dosing interval for chemotherapy was based on the Gompertzian model of tumor growth, suggesting greater sensitivity in smaller tumor masses as they rebounded from cytotoxic treatment. By treating with the next round of chemotherapy earlier, cure rates are increased because the cells do not have time to develop resistance. Similarly, the progression of prostate cancer patients treated with Abiraterone could be greatly reduced by employing an adaptive therapy regime identified using an evolutionary game theory model [49]. This model characterized the competitive interactions between resistant and sensitive subclones, in order to quantify fitness with and without treatment. By analyzing tumor burden biomarker time courses of patients experiencing intermittent androgen suppression, similar evolutionary models could be parameterized, used to identify treatment regime that aim to minimize disease progression [50].

Another approach is to reverse and/or bypass emergent resistance mechanisms, exploiting alternate modes of drug effect and the cost of evolving resistance. Indeed, the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK4/6) inhibitors were originally investigated in ER-positive breast cancer, following observations that the cyclin D1/CDK system was involved in resistance to anti-estrogen agents [51, 52]. The combination of CDK4/6 inhibitors and anti-estrogen agents in metastatic breast cancer delays the onset of estrogen resistance, leading to prolonged survival for patients. A CDK4/6 inhibitor combined with an anti-estrogen can restore sensitivity to anti-estrogen treatment [53]. Adaptive treatment strategies are also being developed to treat metastatic cancer with an oscillating combination of two drugs targeting both sensitive and resistant cells concurrently [54]. Thus, prediction of optimal drug combinations, as well as their sequence and timing, is an active area of systems biology research.

Lastly, a truly systems biology treatment approach would be tailored therapy in which the condition of tumor heterogeneity is repeatedly reviewed and its changing characteristics are used to adaptively identify therapeutic targets. Patient specific responses of sub-clonal populations would then be used to inform clinical decisions about the patient’s future treatment (Fig. 1). The twofold benefit of this approach is that systems biology insights directly feed into clinical decisions, whilst clinical information feedback to inform experimental and computational systems biology approaches, to produce more accurate and informed insights to prevent or manage cancer progression.

Question 2: Consideration of cell interactions and the tumor environment when treating cancer.

Current opportunities for translational systems biology:

With the efficacy of immunotherapy, there is renewed focus on the tumor associated normal cells and their interaction with cancer cells. In particular, we need to understand the role of immune cells, fibroblasts, adipocytes, mesothelial, endothelial and other normal cells found in the tumor microenvironment [55]. However, in the clinic, it is not always clear why a particular therapy regimen is effective (or ineffective), or what the optimal timing and drug combinations are. For example, in metastatic NSCLC without targetable genetic mutations (e.g. EGFR or ALK), immunotherapy, by checkpoint inhibition, is a potential treatment to increase immune recognition and targeting of tumor cells. However, the efforts to boost immune activity leads to an objective response in only around half of these patients. Decision making in this cohort is often based on tumor cells expression of an immune inhibitory ligand (PDL-1) however, other biomarkers related to tumor and immune cell signaling states may be predictive of response [56].

In addition to immunotherapy, targeting endothelial cells and angiogenesis, a process in which blood vessels are formed and can nourish a growing tumor, has had mixed results in cancer [57, 58]. VEGF inhibitors have generally provided small increases in survival in non-small cell lung cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer but not in breast cancer or glioblastoma (with renal cell carcinoma being an exception) [59] [60] It is not clear what the basis for these differences are or why larger gains in survival were not experienced by more patients. Other studies that target components of the tumor environment, such as excessive hyaluronan (HA) accumulation in the tumor microenvironment, have shown some efficacy in patients [61], although additional research is needed to identify those patients who benefit most and find the most effective combination of treatment.

Overall, many questions exist in terms of targeting the tumor microenvironment and tumor and normal cell interactions for effective control of tumor growth. For example, how does drug timing and combination strategies impact the ability of inhibitors to promote immune recognition of tumor cells, and does the inflammatory environment of surgery impacts tumor and immune cell interactions and subsequent response to therapy? Also, why does the combination of immunotherapy plus chemotherapy work well in specific cancers even though chemotherapy decreases lymphocyte counts and most likely impacts tumor and immune cell interactions? Lastly, how can we optimize the efficacy of treatments that target the microenvironment such as matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors, which inhibit cell migration and limit angiogenic processes [62]? We will highlight some systems biology approaches below that may provide avenues for research efforts directed at addressing these questions.

How could systems biology help achieve the ideal?

Systems biology can be utilized to model the key interactions between and among tumor and normal cells, as well as the microenvironment, in order to take advantage of these cell interactions and optimize treatment regimens that enable tumor recognition, targeting and destruction. Interactions and dependencies of tumor cells with tumor associated normal cells in relation to drug response and tumor progression will be leveraged in treatment decisions, and signaling between cancer and normal cells could inform how the specific milieu of cells is together promoting tumor growth. In particular, targetable interactions between cancer and normal cells in the tumor microenvironment could include: 1) mutualistic signaling and/or growth conditions, 2) manipulation or repression of normal cell populations to achieve improved competitiveness or survival, and 3) modification of the environment to enable invasion and growth properties. Below we discuss examples from each of these areas of research and highlight how established ecological approaches may provide a foundation for understanding these interactions.

Cancer subclone interactions.

Recent research supports the view that tumor sub-clonal populations coexist by providing complementary benefits to the overall population to balance out costs of competition. Such mutualistic tumor cell interactions, require both subclones to benefit from each other’s modification of their shared environment. For example, tumor cell contribute to each other’s survival by means of diffusible products such as growth factors and can protect each other when neither could survive alone [63]. Although the study of sub-clonal interactions is relatively new, there is a large body of evolutionary theory which identifies the conditions for such mutualism to evolve and to be evolutionarily stable over time [63–66]. Opportunities also exist to leverage the deep knowledge of mutualism, in which interaction between two or more species has a net benefit to each populations, to drive this area of research in cancer forward [67]. Indeed, examples relevant to cancer subclonal populations exist in both animal and plant communities, where species can coexist by taking distinct roles that improve the fitness of individuals despite the costs of competition. As one example, in flocks of birds, some species flush out prey, which is then visible for all for feeding, while others act as sentinel species to defend mixed populations in the community from predation [68]. These complementary activities benefit the flock as a whole and likely reflect an evolutionarily strategy among interdependent species that provide stable coexistent communities [68]. Similarly, sensitive crop species can be protected from herbivores through “associational resistance”, when grown alongside herbivore resistant species [69]. Interestingly, these interdependent relationships may exist between cancer sub-clonal populations during metastatic progression, with some cells enabling invasion and others providing growth favorable characteristics [70]. There are over 50 models describing mutualistic interactions [71]. As relatively little is known about how tumor cells signal and/or promote mutualistic or commensal growth conditions, these modeling approaches can help reveal the nature of cellular interactions in the tumor environment. Experimental approaches may be used to identify cancer cell signaling mechanisms that promote oncogenic properties, perhaps through transfer of molecules or even complex mixtures of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [72, 73]. Given the emerging complexity of the interactions between cancer subclones, integrating these fields may shed light on some of the rules regulating tumor diversity and sub-clonal survival properties. Interestingly from a clinical perspective, if populations are truly mutualistic, targeting key cellular interactions could improve treatment of multiple clones simultaneously.

In addition to interactions between cancer cells, a second key interaction determining subclonal coexistence is their competition for shared resources. The theoretical basis for the success of adaptive therapy, using treatment holidays, relies on the dominance of sensitive sub-clones over resistant populations [74]. Analogously, in agricultural systems, without herbicides weed species out-compete crops, but with the outcome of competitive interactions switching depending on the herbicide dose [75]. Concepts from integrated pest management, which seeks to avoid competitive dominance and pesticides resistance, may reveal approaches that can be used to control subclonal diversity and combat resistance. For example an established protocol to control pest population sizes, whilst minimizing the change that resistance emerges is to rotate through several pesticides with differing modes of action [76]. This approach to cancer treatment has not been tested as generally patients are treated with a single drug regimen until progression.

Tumor and normal cell interactions: cancer promoting and repressing interactions

There is a key distinction between the interactions of coexisting cancer subclone and those between cancer and normal cells. Cancer subclones each have the potential to rapidly evolve mechanisms to take advantage of one another. In contrast, the normal cell types are still phenotypically constrained to follow normal signaling and response behaviors and cancer cells are free to evolve and abuse them. An early example of cancer cell co-opting interactions with stromal cells was the finding that tumor cells secrete vasculature growth signals, recruiting vasculature and increased nutrient supply necessary to support cancer proliferation [77–79]. More recently, the cancer promoting role of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have become apparent [80]. Current research is revealing the complex biological roles of these cell types [81, 82] and how to change the nature of these interactions from cancer promoting to cancer repressing by altering their signaling states [83].

Experimental immunological insights are also showing the intricate cell interactions involved in the cancer-immune response cycle, and providing insights into the interpatient variability in responsiveness to immunotherapy [84, 85]. To predict the impacts of immunotherapies on cancer-immune interactions, it is likely necessary to consider the phenotypic state of the cells across the entire cancer-immune cycle, immune migration and the intra-tumor diversity in immune resistance [86–89]. In an ecological setting, similarly complex mechanistic population dynamic models of the temporal changes in the abundance of whale species and their ecosystem has provide forecasts of population outcomes amidst changing environmental conditions [90]. Specifically, the authors use a multispecies Model of Intermediate Complexity for Ecosystem assessment approach, which are efficient at developing predictions of species interactions and environmental conditions. This model incorporates known interactions between plankton, nutrients and detritus with ocean and atmosphere dynamics, and is extended to include sea temperature and chlorophyll in order to understand how climate changes impact whale species. These models have yielded clear predictions of how climate change has and will continue to influence whale population recovery and how changes in migratory patterns will alter this outcome [90]. The success of these models, which include ecosystem interactions and dynamics, indicates that mechanistic models describing the roles of diverse immune and cancer cell populations and their signaling microenvironment may help link pre-treatment immune cell profiles to patients’ immunotherapy responses and inform how the microenvironment can be manipulated with combination therapy to improve outcomes.

Tumor microenvironment: cancer growth and invasion properties

Understanding how the environment inside a tumor influences its growth and chance of metastasis will reveal new targeted therapeutic options and will identify why previous microenvironment modulating therapies have largely failed. Cancer cells are known to influence the normal signaling environment, to promote tumor growth and progression. For example, cancer associated fibroblasts have been shown to activate signaling, such as NF-kB, to promote cancer cell resistance and stem cell like phenotypes that contribute to resistance [91]. As another example, it has been proposed that epithelial cancer cells instruct the normal stroma to transform into a wound-healing stroma and provide energy for tumor growth [92]. Other signaling mechanisms include TGFβ secretion by both tumor and immune cells which promote an pro-tumorigenic phenotype for macrophages [93]. Cancer cells can also subvert normal immunological signaling such as antigen presentation by dendritic cells and cytokine signaling by T cells can also be modified [84]. Lastly, when cancers metastasize to different sites, they can release angiogenic factors that promote seeding and drive the biochemical and/or physical remodeling of the environmental, contributing to tumor colonization of the region and cell survival and growth [94].

Many invasion biology studies have focused on environmental factors influencing the colonization success of invasion of species and their clonal expansion. This field may offer a range concepts relevant to the prevention of metastasis. As an example, spotted knapweed is a plant that recently invaded into North America. It produces toxins ((-)-catechin) that destroy the roots of native plants, killing them and enabling rapid invasion. A multiscale spatial model of this system revealed that the speed and success of invasion depends on the presence of resistant native plant populations and their spatial clustering at the invaded sites [95]. In a similar manner, cancer metastasis to different organ sites is likely dependent on regional tissue characteristics and the positive or negative interactions with stromal and other normal cells (e.g. [96]). Indeed, cancers often exhibit preferential metastasis to specific organs during dissemination [97]. Understand the factors (cellular and signaling activities) that are required for metastatic colonization will provide targets for novel methods of metastasis prevention [98]. Furthermore, identifying key tumor cells properties, such as EMT state, that promote dissemination and survival at secondary sites will provide alternative targets in treatment strategies. As it is challenging to study metastatic spread within patients, due to the limited capabilities to biopsy multiple sites, the wealth of models in invasion biology may efficiently direct our efforts. For example, fish migration paths can be retraced, by combining data on the locations they were caught and the isotope signatures of their bones with models approximating their movement behavior [99]. In addition, by leveraging systems approaches across experiments, data from patients, and model organisms, we are beginning to gain a more comprehensive view of key mechanisms driving tumor progression [100].

Conclusion

Evidence is accumulating that cancer progression and resistance is driven, in part, by interactions among a community of diverse cancer cell subclones and normal cells in the microenvironment. While the classical tools of experimental biology are ill equipped to dissect this complexity, significant opportunities exist in systems biology. Systems biology approaches are well-positioned to provide clinical care strategies to match this complexity. Indeed, math models have the ability to shed light on critical needs such as tumor diagnosis, cancer progression, drug timing and drug combinations. By using the wealth of models from fields such as ecology and biology, it is possible to gain an understanding of cell populations, their interactions and dependencies, as well as the role of the microenvironment in response to treatment and progression. These data will provide a path to blocking these key linchpins of cancer that have not yet been successfully targeted.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been supported by an NIH grant U54CA209978.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Soria JC, et al. , Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med, 2018. 378(2): p. 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajappa S, Krishna MV, and Narayanan P, Integrating Osimertinib in Clinical Practice for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment. Adv Ther, 2019. 36(6): p. 1279–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganesan S, Tumor Suppressor Tolerance: Reversion Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and Resistance to PARP Inhibitors and Platinum. JCO Precision Oncology, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seth S, et al. , Pre-existing Functional Heterogeneity of Tumorigenic Compartment as the Origin of Chemoresistance in Pancreatic Tumors. Cell reports, 2019. 26(6): p. 1518–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho H, Berger B, and Peng J, Generalizable and Scalable Visualization of Single-Cell Data Using Neural Networks. Cell Syst, 2018. 7(2): p. 185–191 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu M, et al. , Automatic classification of cervical cancer from cytological images by using convolutional neural network. Biosci Rep, 2018. 38(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang B, et al. , Visualization and analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data by kernel-based similarity learning. Nat Methods, 2017. 14(4): p. 414–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, et al. , Single-cell trajectories reconstruction, exploration and mapping of omics data with STREAM. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.* Saelens W, et al. , A comparison of single-cell trajectory inference methods. Nat Biotechnol, 2019. 37(5): p. 547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; To help understand cell phenotypes and their transition, the authors compared the performance of numerous recently developed computational methods for analysing single cell omics datasets. They evaluate performance on synthetic datasets and provide guidelines for which methods are best for given situations.

- 10.Chadeau-Hyam M, et al. , Deciphering the complex: methodological overview of statistical models to derive OMCS-based biomarkers. Environ Mol Mutagen, 2013. 54(7): p. 542–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolker BM, et al. , Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol, 2009. 24(3): p. 127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.* Hart SP, Turcotte MM, and Levine JM, Effects of rapid evolution on species coexistence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2019. 116(6): p. 2112–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identify genotypic evolution and the resulting phenotypic changes that altered competitive hierarchy of plant species and integrate this with dynamical models to explain population dynamics and species domince.

- 13.* Cho H, et al. , Modelling acute myeloid leukaemia in a continuum of differentiation states. Lett Biomath, 2018. 5(Suppl 1): p. S69–S98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors mathematically model the continual variation in cellular phenotypes occuring during differentation and provide an approach to project how cell states transition during normal and abnormal differentiation. In doing so they predict and then validate the emergence of a novel cellular states during the onset of AML.

- 14.Deng C, Daley T, and Smith AD, Applications of species accumulation curves in large-scale biological data analysis. Quant Biol, 2015. 3(3): p. 135–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iknayan KJ, et al. , Detecting diversity: emerging methods to estimate species diversity. Trends Ecol Evol, 2014. 29(2): p. 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colwell RK and Coddington JA, Estimating terrestrial biodiversity through extrapolation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 1994. 345(1311): p. 101–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ionita-Laza I, Lange C, and M.L. N, Estimating the number of unseen variants in the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(13): p. 5008–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes JB, et al. , Counting the uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2001. 67(10): p. 4399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orlitsky A, Suresh AT, and Wu Y, Optimal prediction of the number of unseen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(47): p. 13283–13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goetz MP, et al. , NCCN Guidelines Insights: Breast Cancer, Version 3.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2019. 17(2): p. 118–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azuaje F, Computational models for predicting drug responses in cancer research. Brief Bioinform, 2017. 18(5): p. 820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang C, et al. , Machine learning predicts individual cancer patient responses to therapeutic drugs with high accuracy. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 16444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y, et al. , Deep Learning Predicts Lung Cancer Treatment Response from Serial Medical Imaging. Clin Cancer Res, 2019. 25(11): p. 3266–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ammad-Ud-Din M, et al. , Systematic identification of feature combinations for predicting drug response with Bayesian multi-view multi-task linear regression. Bioinformatics, 2017. 33(14): p. i359–i368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McVeigh TP, et al. , The impact of Oncotype DX testing on breast cancer management and chemotherapy prescribing patterns in a tertiary referral centre. Eur J Cancer, 2014. 50(16): p. 2763–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandao M, Ponde N, and Piccart-Gebhart M, Mammaprint: a comprehensive review. Future Oncol, 2019. 15(2): p. 207–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Z, et al. , Analytical performance of a bronchial genomic classifier. BMC Cancer, 2016. 16: p. 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.**Risom T, et al. , Differentiation-state plasticity is a targetable resistance mechanism in basal-like breast cancer. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors identify a drug tolerant persister cell state that is induce by therapy. They show that this plasticity involves dynamic remodeling of open chromatin architecture and identify therpeutic options to block this cell state transition.This promoted cancer cell death in vitro and xenograft regression in vivo.

- 29.Hooker G, et al. , Parameterizing state-space models for infectious disease dynamics by generalized profiling: measles in Ontario. J R Soc Interface, 2011. 8(60): p. 961–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, et al. , Targeting protein kinases to reverse multidrug resistance in sarcoma. Cancer Treat Rev, 2016. 43: p. 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brady SW, et al. , Combating subclonal evolution of resistant cancer phenotypes. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horinouchi T, et al. , Prediction of Cross-resistance and Collateral Sensitivity by Gene Expression profiles and Genomic Mutations. Sci Rep, 2017. 7(1): p. 14009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arango-Argoty G, et al. , DeepARG: a deep learning approach for predicting antibiotic resistance genes from metagenomic data. Microbiome, 2018. 6(1): p. 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anchang B, et al. , DRUG-NEM: Optimizing drug combinations using single-cell perturbation response to account for intratumoral heterogeneity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2018. 115(18): p. E4294–E4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baucom RS, Evolutionary and ecological insights from herbicide-resistant weeds: what have we learned about plant adaptation, and what is left to uncover? New Phytologist, 2019. 223(1): p. 68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellner SP, Geber MA, and Hairston NG Jr., Does rapid evolution matter? Measuring the rate of contemporary evolution and its impacts on ecological dynamics. Ecol Lett, 2011. 14(6): p. 603–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forsman A, Rethinking phenotypic plasticity and its consequences for individuals, populations and species. Heredity (Edinb), 2015. 115(4): p. 276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang B, et al. , RACIPE: a computational tool for modeling gene regulatory circuits using randomization. BMC Syst Biol, 2018. 12(1): p. 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Demetri GD, et al. , Expression of colony-stimulating factor genes by normal human mesothelial cells and human malignant mesothelioma cells lines in vitro. Blood, 1989. 74(3): p. 940–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian XJ, Zhang H, and Xing J, Coupled reversible and irreversible bistable switches underlying TGFbeta-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Biophys J, 2013. 105(4): p. 1079–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorenzi T, Chisholm RH, and Clairambault J, Tracking the evolution of cancer cell populations through the mathematical lens of phenotype-structured equations. Biol Direct, 2016. 11: p. 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho H and Levy D, Modeling the Dynamics of Heterogeneity of Solid Tumors in Response to Chemotherapy. Bull Math Biol, 2017. 79(12): p. 2986–3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Celia-Terrassa T, et al. , Hysteresis control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition dynamics conveys a distinct program with enhanced metastatic ability. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 5005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stein S, et al. , Mathematical modeling identifies optimum lapatinib dosing schedules for the treatment of glioblastoma patients. PLoS Comput Biol, 2018. 14(1): p. e1005924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engelhart M, Lebiedz D, and Sager S, Optimal control for selected cancer chemotherapy ODE models: a view on the potential of optimal schedules and choice of objective function. Math Biosci, 2011229(1): p. 123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirin A, et al. , Prediction of Optimal Drug Schedules for Controlling Autophagy. Sci Rep, 2019. 9(1): p. 1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallaher JA, et al. , Spatial Heterogeneity and Evolutionary Dynamics Modulate Time to Recurrence in Continuous and Adaptive Cancer Therapies. Cancer Res, 2018. 78(8): p. 2127–2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simon R and Norton L, The Norton-Simon hypothesis: designing more effective and less toxic chemotherapeutic regimens. Nat Clin Pract Oncol, 2006. 3(8): p. 406–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, et al. , Integrating evolutionary dynamics into treatment of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.**Hirata Y, et al. , Personalizing Androgen Suppression for Prostate Cancer Using Mathematical Modeling. Sci Rep, 2018. 8(1): p. 2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors develp a personalised mathematical model to guide the dosing schedule for prostate cancer patients reieving androgen suppression therapy.

- 51.Arteaga CL, Cdk inhibitor p27Kip1 and hormone dependence in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2004. 10(1 Pt 2): p. 368S–71S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finn RS, et al. , PD 0332991, a selective cyclin D kinase 4/6 inhibitor, preferentially inhibits proliferation of luminal estrogen receptor-positive human breast cancer cell lines in vitro. Breast Cancer Res, 2009. 11(5): p. R77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Malorni L, et al. , Palbociclib as single agent or in combination with the endocrine therapy received before disease progression for estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: TREnd trial. Ann Oncol, 2018. 29(8): p. 1748–1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.West JB, et al. , Multidrug Cancer Therapy in Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer: An Evolution-Based Strategy. Clin Cancer Res, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hilliard TS, The Impact of Mesothelin in the Ovarian Cancer Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel), 2018. 10(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Auslander N, et al. , Robust prediction of response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in metastatic melanoma. Nat Med, 2018. 24(10): p. 1545–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rajabi M and Mousa SA, The Role of Angiogenesis in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines, 2017. 5(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yadav L, et al. , Tumour Angiogenesis and Angiogenic Inhibitors: A Review. J Clin Diagn Res, 2015. 9(6): p. XE01–XE05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maj E, Papiernik D, and Wietrzyk J, Antiangiogenic cancer treatment: The great discovery and greater complexity (Review). Int J Oncol, 2016. 49(5): p. 1773–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen C and Kaelin WG Jr., The VHL/HIF axis in clear cell renal carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol, 2013. 23(1): p. 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hingorani SR, et al. , HALO 202: Randomized Phase II Study of PEGPH20 Plus Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine Versus Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine in Patients With Untreated, Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2018. 36(4): p. 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Belli C, et al. , Targeting the microenvironment in solid tumors. Cancer Treat Rev, 2018. 65: p. 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Axelrod R, Axelrod DE, and Pienta KJ, Evolution of cooperation among tumor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006. 103(36): p. 13474–13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Mazancourt C and Schwartz MW, A resource ratio theory of cooperation. Ecol Lett, 2010. 13(3): p. 349–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leigh EG Jr., The evolution of mutualism. J Evol Biol, 2010. 23(12): p. 2507–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tabassum DP and Polyak K, Tumorigenesis: it takes a village. Nat Rev Cancer, 2015. 15(8): p. 473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vazquez DP, et al. , A conceptual framework for studying the strength of plant-animal mutualistic interactions. Ecol Lett, 2015. 18(4): p. 385–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martinez AE and Gomez JP, Are mixed-species bird flocks stable through two decades? Am Nat, 2013. 181(3): p. E53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Atsatt PR and O’Dowd D J, Plant defense guilds. Science, 1976. 193(4247): p. 24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Labelle M and Hynes RO, The initial hours of metastasis: the importance of cooperative host-tumor cell interactions during hematogenous dissemination. Cancer Discov, 2012. 2(12): p. 1091–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.**Wu F, et al. , A unifying framework for interpreting and predicting mutualistic systems. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors examine the dynamics behaviour of a large number of community models of species interactions and deduce general rules that allow detection of mutualism.

- 72.Maia J, et al. , Exosome-Based Cell-Cell Communication in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2018. 6: p. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tkach M and Thery C, Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell, 2016. 164(6): p. 1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gatenby RA, et al. , Adaptive therapy. Cancer Res, 2009. 69(11): p. 4894–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park SE, Benjamin LR, and Watkinson AR, The theory and application of plant competition models: an agronomic perspective. Ann Bot, 2003. 92(6): p. 741–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sudo M, et al. , Optimal management strategy of insecticide resistance under various insect life histories: Heterogeneous timing of selection and interpatch dispersal. Evol Appl, 2018. 11(2): p. 271–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abdollahi A and Folkman J, Evading tumor evasion: current concepts and perspectives of anti-angiogenic cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat, 2010. 13(1–2): p. 16–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Folkman J, Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med, 1971285(21): p. 1182–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Folkman J, What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J Natl Cancer Inst, 1990. 82(1): p. 4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ireland LV and Mielgo A, Macrophages and Fibroblasts, Key Players in Cancer Chemoresistance. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2018. 6: p. 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen P, et al. , Symbiotic Macrophage-Glioma Cell Interactions Reveal Synthetic Lethality in PTEN-Null Glioma. Cancer Cell, 2019. 35(6): p. 868–884 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang A, et al. , Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote M2 polarization of macrophages in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med, 2017. 6(2): p. 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen X and Song E, Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2019. 18(2): p. 99–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.**Garris CS, et al. , Successful Anti-PD-1 Cancer Immunotherapy Requires T Cell-Dendritic Cell Crosstalk Involving the Cytokines IFN-gamma and IL-12. Immunity, 2018. 49(6): p. 1148–1161 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors reveal the within tumor signalling between immune cell types that produce responsiveness to immunotherapy.

- 85.Chung W, et al. , Single-cell RNA-seq enables comprehensive tumour and immune cell profiling in primary breast cancer. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Qomlaqi M, et al. , An extended mathematical model of tumor growth and its interaction with the immune system, to be used for developing an optimized immunotherapy treatment protocol. Math Biosci, 2017. 292: p. 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ozik J, et al. , High-throughput cancer hypothesis testing with an integrated PhysiCell-EMEWS workflow. BMC Bioinformatics, 2018. 19(Suppl 18): p. 483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Palsson S, et al. , The development of a fully-integrated immune response model (FIRM) simulator of the immune response through integration of multiple subset models. BMC Syst Biol, 2013. 7: p. 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carbo A, et al. , Systems modeling of molecular mechanisms controlling cytokine-driven CD4+ T cell differentiation and phenotype plasticity. PLoS Comput Biol, 2013. 9(4): p. e1003027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tulloch VJD, et al. , Future recovery of baleen whales is imperiled by climate change. Glob Chang Biol, 2019. 25(4): p. 1263–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sun Q, et al. , The impact of cancer-associated fibroblasts on major hallmarks of pancreatic cancer. Theranostics, 2018. 8(18): p. 5072–5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pavlides S, et al. , The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle, 2009. 8(23): p. 3984–4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Flavell RA, et al. , The polarization of immune cells in the tumour environment by TGFbeta. Nat Rev Immunol, 2010. 10(8): p. 554–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maishi N and Hida K, Tumor endothelial cells accelerate tumor metastasis. Cancer Sci, 2017. 108(10): p. 1921–1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de Souza DR, Martins ML, and Carmo FMS, A multiscale model for plant invasion through allelopathic suppression. Biological Invasions, 2010. 12(6): p. 1543–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Altorki NK, et al. , The lung microenvironment: an important regulator of tumour growth and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer, 2019. 19(1): p. 9–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Langley RR and Fidler IJ, The seed and soil hypothesis revisited--the role of tumor-stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. Int J Cancer, 2011. 128(11): p. 2527–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Budczies J, et al. , The landscape of metastatic progression patterns across major human cancers. Oncotarget, 2015. 6(1): p. 570–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sakamoto T , et al. , Combining microvolume isotope analysis and numerical simulation to reproduce fish migration history. MEE, 2019. 10(1): p. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Welch DR and Hurst DR, Defining the Hallmarks of Metastasis. Cancer Res, 2019. 79(12): p. 3011–3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]