Abstract

Human body is inhabited by vast number of microorganisms which form a complex ecological community and influence the human physiology, in the aspect of both health and diseases. These microbes show a relationship with the human immune system based on coevolution and, therefore, have a tremendous potential to contribute to the metabolic function, protection against the pathogen and in providing nutrients and energy. However, of these microbes, many carry out some functions that play a crucial role in the host physiology and may even cause diseases. The introduction of new molecular technologies such as transcriptomics, metagenomics and metabolomics has contributed to the upliftment on the findings of the microbiome linked to the humans in the recent past. These rapidly developing technologies are boosting our capacity to understand about the human body-associated microbiome and its association with the human health. The highlights of this review are inclusion of how to derive microbiome data and the interaction between human and associated microbiome to provide an insight on the role played by the microbiome in biological processes of the human body as well as the development of major human diseases.

Keywords: Human microbiome, Microbiota, Metagenomics, Metabolomics

Introduction

The human microbiome is a complex aggregate of the microbes residing at various sites in the human body (Shreiner et al. 2015) and consisting of communities of a variety of microorganisms including Eukaryotes, Archaea, Bacteria, and the virus that reside in the different body habitat including the skin, the oral cavity, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, reproductive tract etc. (Sender et al. 2016; Shreiner et al. 2015). A microbiota is described as a community of microorganisms that resides in a distinct environment and the collection of entire genomic elements of a distinct microbiota is the microbiome. Earlier the microbiome was estimated to encode approximately 100-fold more gene than the entire human genome but later it was studied to account for tenfolds (Sender et al. 2016). The Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg used the term microbiome to define the complex ecological communities of the symbiotic, commensal and pathogenic microorganisms residing the human body (Kilian et al. 2016). The development of various new technologies namely meta-transcriptomics, metagenomics, metabolomics and some other bioinformatics tools have aided in the understanding of contribution of the different human microbiome and their importance in human health and diseases (Aguiar-pulido et al. 2016). The Human-Microbiome Project (HMP) and the Metagenomics of the Human Intestinal Tract (MetaHIT) project, financed by the National Institutes of Health, USA and the European Commission respectively, have initiated immense programs aimed at surveying the reserve of microbial genes and genomes collectively termed as the microbiome (Eloe-Fadrosh and Rasko 2013; Peterson et al. 2009). The human microbiota, along with the gastrointestinal tract, consists of more than 100 trillion microbial cells harbored in every individual (Ursell et al. 2012). Of the total human cell, approximately 90% are in association with the microbiota with only the remaining 10% that are free from microbiome (Pflughoeft and Versalovic 2012). Henceforth it demonstrates the concept that each organ has its specified flora (Palmer et al. 2007).

Each individual houses diverse microbial community in different body sites which differs greatly in terms of their composition and functions. Microbial diversity varies based on the anatomic site, the complexity and aggregate functions of the microbial communities and correlates with an individual’s health status, genotype, diet and hygiene. The genetic diversity and the number of different microbial cells present in a microbiome is regulated, partly by the local environment and also by the biology of that body site (Redinbo 2014). Human first acquires significant amounts of microbiota from their mother during birth. This microbial composition is highly dynamic and ever changing during the early first three years of life and after that it becomes relatively stable but numerous small changes occur constantly throughout childhood, adolescence, middle age and old age (Bhatt et al. 2017; Palmer et al. 2007). The microbial communities present in a microbiome makes a unique biological relationship termed symbiosis where they perform some indispensable functions that define and contribute to the physiology of the host (Leung and Poulin 2008). To understand the roles of these symbionts and their impact on human health, Microbiome projects have been launched worldwide (Ursell et al. 2012). The literature of the human microbiome defines symbiosis in a wide range that spans from a commensalistic relationship in which the interaction proves beneficial for any one of the symbiotic partners, while other species involved neither gains benefit nor is harmed, to a mutualistic relationship with favorable outcomes for all the organisms involved. Although a vast majority of these microbes carry out some functions that are critical for host physiology, they may also cause diseases (Wang et al. 2017a).

The objective of this review article is to focus on the microbial composition at various body sites, with specific interest on the host-microbiota systems and how its composition may be manipulated for human benefits and how perturbations of these interactions lead to dysbiosis. This review tries to understand the importance of the various microbial communities present in the normal human microbiome and the consequences of its dysbiosis along with its role in various functions such as inflammatory, immune, and also infectious diseases of a human.

Tools for microbial analysis

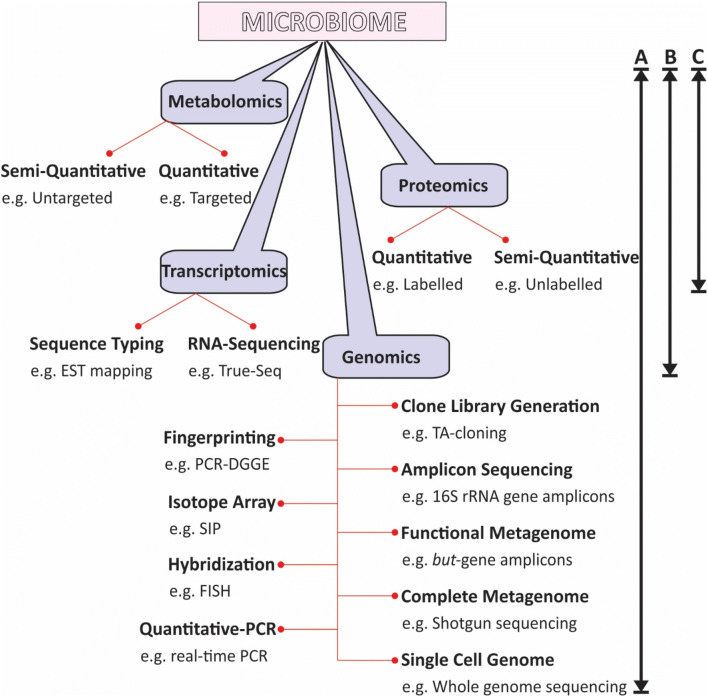

The importance of metagenomics, meta-transcriptomics and metabolomics approaches as the tool for the study of microbes have also been considered (Fig. 1). The identification of about 70% of human microbiota, which was not possible by the existing conventional microbiological methods, has been made possible by the development of the advanced techniques of metagenomic, metatranscriptomic, metabolomic (Kinross et al. 2008). Metagenomic is a biotechnological perspective of studying the genomic structure of the DNA directly extracted from their natural source (Lim et al. 2013). These novel methods have been used by scientist to provide evidence for existence of genes of above one thousand microbial species residing in our body. The metagenomic approach has the potential to discover genes, gene families, and their encoded proteins which are entirely new and which might be of great importance in the field of biotechnological and pharmaceutical science. It allows us to explore the composition of a microbial community (Moran 2009).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of different available methods to answer the questions related to the human associated microbiome analyses. Arrow indicating the different questions and, other side their equivalent methods to get respective answers mentioned. The questions such as a who are there in? b What they are doing in? c How they are performing to the ecosystem?

Currently, massive amount of data related to metagenomic studies have been generated constantly by several international organizations like the HMP project and various other independently functioning projects and their microbiome data collection is being managed by the Genomes Online Database (Table 1). The data management system developed for classification and constant monitoring of worldwide sequencing projects contains data taken from more than 4000 metagenome sequencing projects, with more than 1500 targeted at the characterization of host-associated metagenomes. The HMP database first released the data of the microbiome of female body parts i.e. the skin, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, the nasal passages and vagina. The analysis report of human microbiomes of over 690 have shown that a large number of bacteria of the gut microbiome were mainly from four major phyla: Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Proteobacteria (Grice and Segre 2012); (Belizário and Napolitano 2015). It is interesting to note that though a few microbial taxa are the majority dominating the relative abundance of human microbial community, a large number of the microbial taxa which are present in relatively low abundance are the ones contributing to the diversity of the microbiome (Sogin et al. 2006) and are responsible for the long tail of rank abundance curve (Bhute et al. 2017). The technique of random sequencing of the mRNA of the microbial community for studying the function and activities of a complete set of the transcript is involved in meta-transcriptomics. It provides an outline about the genes expressed under specific conditions at particular moment of a given sample by capturing the entire mRNA (Moran 2009). A comprehensive analysis of the metabolites (small molecules involved in microbial metabolism and released into the immediate surrounding) produced by the microbes is done for their identification and quantification in metabolomics.

Table 1.

Online Genome Database for the human microbiome

| Database | Project name | Funding | Link | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAHMI |

MetaHIT |

European Commission | https://mahmi.org/ | Blanco-Míguez et al. (2017) |

| OMBC | National Key R&D Program of China | Frontier Research of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province and the National Natural Science Foundation of China | https://www.sklod.org/ombc | Xian et al. (2018) |

| HOMD | A Foundation for the Oral Microbiome and Metagenome | National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 | https://www.homd.org/ | Chen et al. (2010) |

| Disbiome | Disbiome | Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO)’ and ‘Institute for the Promotion of Innovation through Science and Technology, Flanders | https://disbiome.ugent.be/ | Janssens et al. (2018) |

| HMP Data Coordination Center (DCC) | NIH Human-Microbiome Project | NIH Common Fund | https://hmpdacc.org/ | Proctor et al. (2019) |

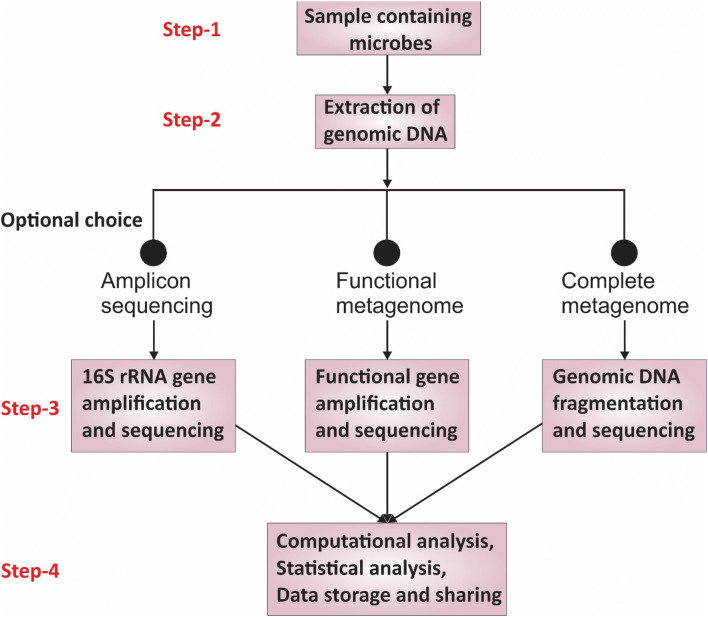

It aims at improving our concept about the role of the microbiome in the modification of nutrients and pollutants along with other abiotic factors that may have an effect on the homeostasis of the host environment (Han et al. 2010). But for the study of the microbiomes, the use of metagenomics approach is far more extensive than that of meta-transcriptomics and metabolomics. Various next-generation sequencing method are widely used for metagenomic study including the16S rRNA sequencing and shotgun sequencing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pictorial representation of major recent developments in studying the link between the gut microbiome and its impact over the host-associated health and disease attributes

16S rRNA gene sequencing

The 16S rRNA sequencing methods serve as a quick and cost-effective method for bacterial identification. However, the limitation of this method is that it is applicable only in case of the bacteria as viruses and parasites do not have the presence of the 16S rRNA genes in their genome (Cénit et al. 2014). The 16S rRNA has a peculiar structure characterized by hypervariable region which makes it ideal for identification of bacteria up to species level. In this method, there is no need to culture the microbes and DNA is extracted directly from a sample followed by the amplification of the 16S rRNA gene using the technique of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) after which the fragments are aligned and the sequence is compared with the database for identification (Hayashi et al. 2002). Moreover, appropriate selection of the hypervariable regions can also lead to probable discovery of the rare taxa present in these microbiomes (Bhute et al. 2017).

The 16S rRNA sequencing gives limited or no information regarding their functional properties (Maruvada et al. 2017). Moreover, the accuracy depends totally on the reference database with reduced resolution at the species level due to the threshold value holding inapplicable in reading interspecies value which is highly variable (Rosselló-Mora et al. 2001). The phylum proteobacteria which represents the less abundant phylum in the human microbiome are thus more difficult to identify (Bradley et al. 2017). To add to this, many of the information on the reference database that predates the modern technology cannot distinguish among the strains with multiple genomvar, a feature of some species of this phylum, which directly influences the accuracy of the microbial identifications using the 16S rRNA sequencing (Janda and Abbott 2007).

Presence of multiple allele of the 16S rRNA gene with inter copy variation in a given species (Liefting et al. 1996) and consideration of only fraction of the 16S rRNA gene for the analysis generates variable results in different studies. Emerging knowledge based on new studies suggest that considering the entire length of the 16S rRNA gene instead of certain specific regions provide a better resolution while accurately resolving the intra-genomic substitutions (Johnson et al. 2019). The petite read length and the primer choice are the other limitations of this technique (Shankar et al. 2015).

Current well-established technologies for sequencing have a shorter length (max 500 bp) and generated with amplification methods would have imposed some limitations. Misleads the taxonomic identification due to shorter length in amplicon regions than complete the 16S rRNA gene sequencing and, higher scaffolds generation or draft genome than complete genome sequence attendance in single organism sequencing (Toma et al. 2014).

Newer technologies with long-read sequencing from a Single-Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing technology and, ‘amplification through ionic current passing technology by ‘PacBio’ and ‘Oxford Nanopore’ devices respectively have been developed to attend the longer reads (Bharti and Grimm 2019). Longer reads were convenient to access the repeated sequence region and hard to sequence through amplification regions in genomes (Johnson et al. 2019; Shin et al. 2016). Advantageous in a very small amount of template DNA from extreme environments and reading efficiencies demonstrate the complete genome of pathogens from epidemic areas as well (Bickhart et al. 2019). Long-read has been successfully utilized and performance calibrated for metagenomic to RNA meta-transcriptomes in the microbiome (Franzosa et al. 2014), and for bacterial single-cell sequencing (Gawad et al. 2016). So, these recent technology-based literature suggests the trends for the new era of sequencing platforms at least for microbiome would be generalized.

Shotgun sequencing

Shotgun sequencing is the method that can analyze the entire microbial community. The genomic DNA is directly extracted from the sample then the DNA is amplified using random primers and it is sequenced to prepare NGS library for downstream high-throughput sequencing. After sequencing, the fragments obtained can be analyzed to identify the species (D’Argenio and Salvatore 2015). The main advantage of this technique is that it skips the steps of culture cultivation and PCR and can identify the bacteria up to species level. It can also be used for identifying the viruses (Hyde et al. 2017).

Limitations of human-microbiome study

The first main challenge in better understanding of the human microbiome is the high budget of such ambitious projects. The presently available techniques give resolution till the species level but are unable to identify the various strains with ‘snap-shot’ approaches not giving a clearer view of how the various external factors influence the microbial composition over a period of time. Another obstruction comes in the form of available data showing interpersonal diversity even among the healthy individuals thus complicating the understanding of the role of the microbial constituents in diseased state (Lloyd-Price et al. 2016). Tools to reason out this variability for the development of various immune boosting and strategies for the treatment of illness is the need of the hour (Maruvada et al. 2017). While an important criterion for proposing a strain as a prospective new species involves its phenotypic characterization (Fournier et al. 2014), the study of the human microbiota using the conventional practices has its constraints. The offered culture condition is partial to the fast-growing microbes with simple nutrient requirements while disregarding the ones with complex growth prerequisites with differentiation of discrete colonies based on morphology alone possessing a challenge (Finegold et al. 1983). Thus, the modern molecular approaches have been developed that provides an alternative for studying the human microbiome. These culture independent techniques, however, themselves are not completely flawless. The absence of reference genome representatives for homology-based methodology in the shotgun approaches is a major limiting factor in taxonomic identification of a DNA sequence. The composition-based method though overcome this limitation but are highly inaccurate (Luo et al. 2014). Another important limitation of molecular method is that they neglect the microbial population present in low abundance thus not giving accurate picture of the microbiome diversity. The presence of exiguous or scores of closely related species creates a hurdle by reducing the chances of occurrence of close match for assigning a function or a taxonomic position to the reads generated (Albertsen et al. 2013). The downstream processing also faces the concerns of read length, error rate coverage along with presence of chimeric contigs (Kim et al. 2013). For accurate bacterial identification, study of sample diversity and proper knowledge of abundance, whole genome recovery are the limitations of short read length (Kuleshov et al. 2016). The knowledge of the viability of the organism in response to the host defense or any antibiotic treatment is lacking (Weinstock et al. 2012). Moreover, the molecular method alone is not accurate for the identification of the previously unidentified microbes. Lately, new complementary approach named “culturomics” is emerging where mass spectroscopy is coupled with diverse culture conditions for unearthing of previously unknown species (Sankar et al. 2015). Thus, new technologies that includes novel culturing techniques for growth promotion of presently unculturable microbes for enhanced knowledge of host-microbiome interaction are needed (Ma et al. 2014).

Human-microbiome composition

The human body is colonized by different microbial population from early neonatal state, during childhood and further changes throughout the lifespan depending upon the life style and diseased condition (Johnson and Versalovic 2012). The community composition and density of a microbiome varies enormously at different sites within an organ system (Dethlefsen et al. 2007). For example, the upper regions of the respiratory tract are more densely populated than the lower regions of the respiratory tract (Wilson 2005). In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the stomach, duodenum, and ileum have low population densities, whereas the jejunum, caecum, and colon are densely populated (Belizário and Napolitano 2015). According to dominance, the predominant bacterial phyla comprising hundreds of bacterial genera and species in the human body are the Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and the Proteobacteria (Table 2). The population of these different bacterial species vary significantly among individuals, and the bacterial community composition appears to primarily depend on different body habitat. The microbiome composition in the human skin differs dramatically on the basis of the relative humidity of skin at different location on the human body with predominant presence of the members of the bacterial phyla of Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, or Proteobacteria. Bacteroidetes also constitute a minor composition of skin microbiome depending upon the skin sites (Wang et al. 2017a). In gastrointestinal (GI) tract the predominant bacterial phyla are mainly the Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria while Firmicutes comprise the major phylum in the vagina (Palmer et al. 2007). The composition of bacteria associated with gut varied drastically in case of infants depending upon the timing of acquisition and colonization by individual bacterial species.

Table 2.

The predominant bacterial phyla of the human body

| Bacterial phylum | Class | Example | Body location | Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | Acidimicrobiia, Actinobacteria, Coriobacteriia, Rubrobacteria, Thermoleophilia, Nitriliruptoria | Corynebacterium, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Bifidobacterium, Streptomyces | Intestine, oral cavity, skin | Gram-positive, filamentous, physiologically aerobic, they can be heterotrophic or chemoautotrophic, but most are chemoheterotrophic and able to use a wide variety of nutritional sources | Donova (2007), Barka et al. (2016) |

| Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidia, Flavobacteria, Sphingobacteria | Bacteroides, Prevotella | Intestine, oral cavity | Aerobic and anaerobic, non-spore-forming, Gram-negative rods | Wexler (2007), Gupta (2004) |

| Firmicutes | Bacilli, Clostridia, Erysipaelotrichia, Thermolithobacteria, Negativicutes | Clostridium, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus spp | Intestine, skin, stomach | Gram-positive, rod, coccoid, spiral in shape, anaerobic, aerobic, include commensal and beneficial bacteria | Zhuang et al. (2019), Reichmann and Gründling (2011) |

| Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria, Epsilonproteobacteria | Escherichia, Salmonella, Vibrio, Helicobacter, Yersinia, Legionellales | Large intestine, skin | Gram-negative bacteria | Kersters et al. (2006) |

Initially, the GI tract is colonized by Facultative bacteria e.g. Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp., Streptococci, and Staphylococcus spp. (Rodríguez et al. 2015), after which an anaerobic condition is created in the gut of infants due to the consumption of oxygen by these facultative bacteria. This anaerobic environment when coupled with the Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs) present in breast milk leads to a shift of the microbiome towards an anaerobic environment with predominant presence of various anaerobic bacteria as for example the Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Clostridium spp. (Palmer et al. 2007). GI also has presence of some rare taxa which are phylogenetically diverse and may have a role in crucial physiological function as well as pathophysiology of various human gut related disease (Bhute et al. 2017).

The core human microbiome has been developed by the age of one year but it is continuously changing or may be evolving from adolescent children to adults, governed by various determinants (Johnson and Versalovic 2012). It is interesting to note that the various organisms residing in different parts of the human body are well adapted to the hostile conditions in those locations. Example Candia species found in the low pH environment of vagina is naturally occurring acidophiles. Therefore, it can be predicted that these organisms have similar mechanism for adaptation in the human microbiome as in their natural environment (Dhakar and Pandey 2016). Various organisms found at particular pH in the natural environment are found to be present at locations with similar pH range in the human body (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tolerant pH range for the various organisms found in the natural environment and their location in the human body

| Scientific name | pH | Body location | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus epidermis | 5–14 | Skin | Pandey et al. (2015) |

| Cladosporium spp. | 3.5–6.7 | Oral cavity | Gross and Robbins (2000) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 6.5 | Respiratory tract | Savic and McShan (2012) |

| Helicobacter pylori | 2.7–7.4 | Stomach | Sidebotham et al. (2003) |

| Lactobacillus bulgaricus | 5.8–6 | Intestine, oral cavity | Rault et al. (2009) |

| Lactococcus lactis subspp. cremoris | 6.3–6.9 | Intestine, oral cavity | Rault et al. (2009) |

| Peptoniphilus stercorisuis spp. | 6–9 (7.75) | Urinary system | Johnson et al. (2014) |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | 6.5–7 | Vagina | Takahashi and Schachtele (1990) |

| Bacteroide intermedius | 5–7 | Vagina, intestine | Takahashi and Schachtele (1990) |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 7 | Respiratory tract | Mishra et al. (2008) |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 6.75 | Vagina | Brookes and Sikyta (1967) |

| Bifidobacterium | 4.5–8.5 | Oral cavity, intestine | Biavatiet al. (2000) |

| Streptococcus mutans | 6.5–7 | Oral cavity | Handelman and Kreinces (1973) |

| Clostridium spp. | 7–11 | Intestine | Li et al. (1993) |

| Candida albicans | 2–10 | Respiratory tract, urinary system | Sherrington et al. (2017) |

Human-microbiome interaction

Innumerable microbial species and various complex microbial ecosystems are the residents of human body and these microbiomes affect host physiology in considerable amount (Cho and Blaser 2012). Interactions between the human and its associated microbiota are numerous and complex and these microbiomes play various roles in different sites of the human body, from symbiotic to pathogenic with enormous capacity to impact our physiology in terms of health and disease (Shreiner et al. 2015).

Skin microbiome

The largest organ of the human body, skin is colonized by a discrete group of microorganisms of which majority is harmless or even beneficial to the human and some are harmful (Belizário and Napolitano 2015). The skin is an ecosystem composed of 1.8 m2 of wide range of habitats with an enormous folds and invaginations along with specialized niches which supports a broad range of microorganisms (Grice and Segre 2011). The four principal phyla: Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria (Pflughoeft and Versalovic 2012), characterize the microbiota of the skin with prominent populations of Actinobacteria (e.g. Corynebacterineae, Propionbacterineae) in the portion of the body that are richly supplied with sebaceous glands whereas the dry areas such as volar forearm are enriched with Proteobacteria. Different microorganisms are present on the skin of variable portions of the body (Table 4). Microorganisms those belonging to the genera Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Propionibacterium, Micrococcus, Malassezia, Brevibacterium, Dermobacter, and Actinobacter (Roth and James 1988) are the most common occupant of the skin surface. Staphylococcus spp. and Corynebacterium spp. are the most common organisms colonizing moist areas such as the antecubital fossa (inner elbow), the gluteal crease (uppermost part of the fold in between the buttocks), the axillary vault, the sole of foot, the popliteal fossa (behind the knee), umbilicus (navel) and inguinal crease (side of the groin) as revealed by the metagenomic analysis (Grice et al. 2009, 2008).

Table 4.

Microorganisms present on the different region of the skin

| Region | Predominant organism | References |

|---|---|---|

| Scalp | Staphylococci (S. captis, S. epidermidis etc.), Propionibacterium acne, P. granulosum, P. avedum, Malassezia spp. | Grice and Segre (2011, 2012) |

| Toe interspace | Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, S. cohnii, S. hominis, S. warneri, Micrococcus spp., Malassezia spp. | Grice and Segre (2011, 2012) |

| Perineum | P. acne, P. granulosum, P. avedum, S. epidermidis, S. hominis, S. aureus, Coronybacterium minutissimum, C. xerosis, C. jeikeium, Malassezia spp., Strepyococci, E. coli | Grice and Segre (2011, 2012) |

| Axillae | P. acne, P. avidum, P. granulosum, S. aureus, S epidermidis, S. saprophyticus, C. xerosis, C. minutissimum, Gram-negative rods (E. coli, Klebsiella, Proteus, Enterobacter spp, Actinobacter spp) | |

| Sole of the foot | S. epidermidis, S. hominis, S. haemolyticus, S. cohnii, S. warneri, Malassezia spp, Micrococcus spp, aerobic coryneforms, Gram-negative organism | |

| Forearm and leg | Staphylococci (S. haemolyticus, S. epidermidis, S. aureus, S. hominis), coryneform and propionibacteria | |

| Hands | S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. hominis, C. xerosis, C. minutissimum, yeast and other fungi (Candida parapsilosis, Rhodotorula rubra), Gram-negative bacilli (Pseudomonas spp, Enterobacter spp) | |

| Outer ear | S. auricularis, S. epidermidis, S. captis, S. aureus, S. caprae, Brevibacterium spp, Turicella otitidis, Alloiococcus otitis |

Benefits of the skin microbiome

Commensal bacteria residing on the skin protects the human from other pathogenic bacteria by producing bacteriocin, some toxic metabolites, protein complex, antibiotics that have an antagonistic effect on pathogenic organisms (Chiller et al. 2001). For example, Staphylococcus aureus strain 502A releases a bacteriocin which plays a role in inhibiting other virulent strains of staphylococcal organisms (Peterson et al. 1976). The extracellular enzyme produced by many members of the cutaneous microbiota also plays a key role by hydrolyzing the host macromolecules to low molecular mass compounds that can be transported inside the cell to serve as nutrients. A resident bacterium also competes with another strain of a similar species for the resources available such as binding sites, nutrient, niches etc. and prevents their colonization. e. g. Staphylococcus epidermidis binds to the keratinocyte receptor and inhibit binding of Staphylococcus aureus (Bibel et al. 1983; Chiller et al. 2001).

Disease caused by skin microbiome

Skin disorder can be associated with a specific organism with three main cases:

A skin disorder correlated to its microbiota.

A skin disorder with a microbial component currently unidentified.

A skin commensal with the potential to cause infection and that can become invasive (Grice and Segre 2011). Erysipelas, impetigo, cellulitis, acne, wound infection, seborrhoeic dermatitis, erythrasma, pitted keratolysis etc. are major skin disease caused by different microorganisms (Table 5).

Table 5.

Skin diseases, its characteristics, and associated organisms

| Disease | Characteristics | Organisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erysipelas | Bacterial skin infection involving the upper dermis that extends into the superficial cutaneous lymphatics | Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus | Kilburn et al. (2010); Gunderson and Martinello (2012) |

| Impetigo | Highly contagious bacterial skin infection that causes red sores that can open, ooze fluid, and develop a yellow–brown crust | Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus | Pereira (2014); Romani et al. (2015) |

| Cellulitis | Common and potentially serious bacterial infection of skin and tissues beneath the skin | Streptococcus spp, Staphylococcus spp. | Chira and Miller (2010); Gunderson and Martinello (2012) |

| Acne | A skin infection that occurs when hair follicles are a plug with dead skin cells and oil from the skin | Propionibacterium | Beretta-piccoli et al. (2000) |

| Trichomycosis | Infection of the hair shaft in the skin that occurs mainly in the pubic region, armpits etc | Corynebacterium spp. | Zawar (2011) |

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis | A skin infection that causes scaly patches and red skin, mainly on the scalp | Malassezia spp | Grice and Segre (2011) |

| Erythrasma | A superficial skin infection that causes brown, scaly skin patches | Corynebacterium minutissimum | Wharton et al. (1998) |

Oral microbiome

One of the most versatile microbiomes is harbored by the oral cavity of humans including bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, etc. This association between the humans and their microflora of the oral region commence immediately after the birth and stays for a lifetime (Jenkinson and Lamont 2005). The oral cavity has presence of two categories of surfaces which can be colonized by the bacteria; the hard surfaces of teeth or solid surface (teeth or dentures) and the soft tissue of the oral mucosa or shedding (Zaura et al. 2009). Over 700 bacterial species reside and play a part in the health and anatomical conditions of the oral cavity (Zarco et al. 2012). The major bacterial genera of the human oral cavities include Streptococcus, Granulicatella, Gamella, Actinomyces, Corynebacterium, Rothia, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Capnocytophaga, Neisseria, Haemophilus, Treponema, Eikenella, Leptotrichia, Lactobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Staphylococcus, Eubacteria and Propionibacterium (Aas et al. 2005) with Candida, Cladosporium, Saccharomycetales, Fusarium, Aspergillus and Cryptococcus being the predominant genera of the fungus (Wade 2013). Some viruses which are mainly related to disease can also be found to be present in the mouth, such as the mumps and the rabies viruses that infects the salivary glands. The human papillomavirus which is responsible for various oral conditions which include condylomas, papillomas and the focal epithelial hyperplasia can also be found (Kumaraswamy and Vidhya 2011). Trichomonas tenax and Entamoeba gingivalis are the two protozoa mainly residing the oral cavity of human (Wantland et al. 1958).

Oral microbiome and human health

The composition of the oral bacterial community is highly complex with some of them providing important benefits to human e.g. by help in digestion, confer immunity, colonization resistance, synthesis of vitamin etc.

Role in digestion

Some oral microorganism helps in digestion of nutrients, particularly complex carbohydrates that cannot be degraded by the human digestive enzyme. These microbes can hydrolyze the non-digestible polysaccharide into small chain fatty acids which are then metabolized by a human (Dagli et al. 2016). Some resident gluten degrading microorganisms have also been found to be present in the oral cavity. Gluten, the dietary protein that is difficult to digest by the human proteolytic enzyme is degraded by the endo-protease produced by some oral microorganisms and thereby helping in its digestion (Helmerhorst et al. 2010).

Confer immunity

The oral microbiome plays a significant role in conferring immunity to the human health with some of them regulating the activities, development of an immune cell, provide immunological priming, down-regulation of pro-inflammatory response and provide immunity (Dagli et al. 2016). Nitrate metabolism is another important property of oral microbiome that reduces nitrate to nitrite. Nitrite regulates blood flow, blood pressure, gastric integrity. Nitrite is then converted to nitric oxide which has antimicrobial property and is essential for vascular health (Wade 2013).

Synthesis of vitamin

Synthesis of the vitamin is one of the important functions of some oral microorganisms. Certain strains of lactic acid bacteria that produce vitamin B12 are also found in the oral cavity (Dagli et al. 2016). Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are the most frequently occurring oral probiotic bacteria that produce vitamins (Dagli et al. 2016).

Colonization resistance

Some oral microorganisms contribute to host defenses by inhibiting the establishment of many other microorganisms. Their presence creates an unfavorable environment that inhibits colonization by the pathogen. Streptococcus salivarius strain K12 which produces a bacteriocin that prevents the growth of Gram-negative species associated with periodontitis disease is one prominent example of such organisms (Wescombe et al. 2009).

Disease caused by the oral microbiome

As the oral cavity is the principal entry point to the human body, the microorganism residing this area have the potential of spreading to different human body sites and cause disease. Oral problems such as periodontal disease, dental caries are among the most widespread diseases affecting nearly all ages worldwide. Oral cancer is another most prevalent disease (Marsh 2000). There are several key species residing the oral cavity which are involved in different disease of oral cavity that includes Porphyromonas gingivalis, Streptococcus mutans, Campylobacter rectus, Prevotella intermedia, Treponema denticola, Eikenella corrodens, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Prevotella intermedia etc. (Filoche et al. 2010). These diseases are a result of poor oral hygiene or other conditions that causes a shift in the configuration of the oral microbiome.

Dental carries

Dental caries, commonly called tooth decay is among some of the most prevalent chronic oral disease and is also the main cause of oral pain and tooth loss (Zarco et al. 2012). People are vulnerable to this disease their entire lifetime. Dental carries occur in the tooth above the gum line (supragingival) that attacks the tooth-supporting tissue. The disease infects both root (root caries) and the crown (coronal caries) portion of permanent teeth and the primary teeth and can affect outer coating of the crown, enamel, cementum and outer surface of the root (Selwitz et al. 2007).

Dental carries are formed due to the complex interaction between fermentable carbohydrate present in the food and acid-producing bacteria residing the oral microbiome (Fejerskov 2004). When supragingival biofilm on teeth matures, acid-producing microbial colonies cumulate the dental plaque which lowers the pH of the oral cavity (Filoche et al. 2010). The low pH environment further facilitates the diffusion of calcium, phosphate, and carbonate out of the teeth resulting in demineralization of tooth tissue and finally, cavitation will eventually take place (Zarco et al. 2012). The most common bacteria which are responsible for dental caries are Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, and Lactobacillus acidophilus. In addition to this microbiome, some other species such as Veillonella, Bifidobacterium, Propionibacterium, Actinomyces, Atopobium, Scardovia species have been found to be associated with the dental carries (Loesche 2007; Parahitiyawa et al. 2010).

Periodontal disease

Periodontal diseases are chronic bacterial infections affecting the gingiva and cause damage to the supporting connective tissue and bone that fixes the teeth to the jaws (Williams et al. 2008). It occurs from plaque accumulation of subgingival that rearranges the microflora from a healthy state to a diseased state resulting in either gingivitis or periodontitis (Filoche et al. 2010).

Gingivitis

Gingivitis is the least severe form of the periodontal disease which is caused by dental plaque that cumulates on the teeth adjoining the gingiva (gums). It is an infection which is polymicrobial with no single associated bacterial agent. The microorganism present begins to produce pathogenic characteristics and cause gingivitis (Horz and Conrads 2007). Gingivitis is easily reversible by adequate oral hygiene.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is an acute and irreparable infection that strikes all the bone and the soft tissue that supports the periodontium and teeth structure (Williams et al. 2008). Some microbes’ secret various proteolytic enzymes that breaks the host tissue resulting in gingival inflammation leading to loss of gingival attachment, periodontal pocket formation, damage to alveolar bone and finally teeth destruction. Once the periodontal pocket is formed, periodontitis becomes irreversible and extremely exasperating to treat (Zarco et al. 2012). The predominant pathogens associated with this disease are Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, Streptococcus sanguis, Tannerella forsythia, Prevotella intermedia, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Fusobacterium nucleatum. In addition to these, Tannerella forsythia, Anaeroglobus geminatus, Filifactor alocis, Eubacterium saphenum, Porphyromonas endodontalis are also found to be linked with periodontitis (Fejerskov 2004; Loesche 2007).

Respiratory tract microbiome

The respiratory system of human consists of a series of tubes known as respiratory tract (conducting zone) and respiratory zone. The conducting portion comprises the nose along with pharynx, larynx, trachea and bronchi whereas the respiratory part consists of the bronchioles, alveolar duct, alveolar sacs and alveoli. The conducting segment of the respiratory apparatus is heavily colonized by microorganisms but the respiratory portion is free from microbes and is generally sterile (Wilson 2005). The respiratory tract may be categorized into upper respiratory tract (nose and pharynx) and the lower respiratory tract (larynx, trachea, bronchi, lungs). The most common bacterial species of respiratory tract include Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus viridians, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Corynebacterium diptheriae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenza, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bordetella pertussis, Klebsiella spp., Neisseria meningitides, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Moraxella spp. (Kelly et al. 2016). In addition to these, many viruses (Adenovirus, Rhinovirus, Influenza virus, Epstein Baar virus, Measles virus etc.) and fungi species (Aspergillus spp., Candida albicans, Candida immitis, Candida neoformans etc.) are also associated with human respiratory tract (Dickson et al. 2016).

Benefits of respiratory tract microbiome

The microbiota present in the respiratory tract acts as a doorkeeper to respiratory health. They provide resistance to colonization by the potential pathogens of the respiratory system. The respiratory microbiota is also associated with maturation and perpetuation of balance of respiratory physiology and its immunity (Man et al. 2017). The microbiome of the pharynx region plays a vital role in respiratory tract infection by protecting the airway lining against air transmitted pathogenic infection (Gao et al. 2014). Certain members of the microbiota which includes Dolosigranulum spp. and Corynebacterium spp. have large beneficial effects on ecosystem balance. They play a crucial role in respiratory health and the exclusion of pathogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumonia, Pseudomonas spp., Haemophilus spp., Klebsiella spp., and Legionella spp. (Biesbroek et al. 2014).

Diseases caused by respiratory tract microbiota

The microorganisms occupying the respiratory tract are the ones responsible for different infections of the upper and the lower portions of respiratory pathway in human. Pharyngitis, sinusitis, otitis media, common cold are the example of some common disease of the upper part of the respiratory tract. In the lower region respiratory airways, pneumonia and bronchitis are the most common disease caused by some bacterial species and virus.

Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis, popularly called the sore throat, is among the most commonly encountered infections of the pharynx. It causes the throat to become sore with problem in swallowing. Other symptoms associated are runny nose along with cough, headache, fever chills, malaise etc. which is usually last for 3–5 days (Wessels 2016). It is caused due to infection of the upper regions of the respiratory tract by some bacteria, virus or fungus. Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes) which is group A Beta-hemolytic microorgansim is a prevelant bacterial species that cause pharyngitis. Other bacterial species such as Corynebacterium diptheriae, Haemophilus influenza, Legionella pneumophilia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitides and fungus species Candida spp., Mycoplasma pneumonia, Coxiella burnettii, Chlamydia pneumonia are also associated with pharyngitis disease (Bosch et al. 2013).

The viruses include Rhinovirus, Adenovirus, Coronavirus, Epstein-Barr virus, Herpes simplex virus, Parainfluenza that are found to cause pharyngitis (Somro et al. 2011).

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the inflammation of the mucosa of the paranasal sinus which is caused by either bacterial or viral infection. It is of two types i.e. acute and chronic. Bacterial sinusitis of the acute type is a very common disease in infants and is the most frequent complication of common cold. In adults, acute sinusitis is most commonly caused by Haemophilus influenzae or Streptococcus pneumoniae (Jousimies-Somer et al. 1988). Some other bacterial species such as Streptococcus pyogenes, Branhamella catarrhalis, coagulase-negative Staphylococci are related to sinusitis (Redinbo 2014). Some anaerobic bacterial species of Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas, coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus are also found to cause chronic sinusitis (Loeb et al. 1999).

Pneumonia

Pneumonia that principally affects the alveoli is a condition of the lung that leads to inflammation. It is caused primarily by the infection of bacteria or virus with fungi and parasite being less common (Wilson 2005). Various types of pneumonia are recognized; Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP), aspiration pneumonia, labor pneumonia, bronchial pneumonia, Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) (Chisti et al. 2009).

Pneumonia can be triggered by a widely diverse group of microorganisms mainly Legionella pneumophila, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, Staphylococcus aureus, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Chlamydophila pneumoniae etc. (Musher and Thorner 2014). Bronchial pneumonia and CAP are caused mainly by Streptococcus pneumoniae but some other bacterial species are also related to this disease such as Haemophilus influenza, Staphylococcus aureus. HAP is primarily caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacteriaceae and Actinobacter spp. (Chisti et al. 2009; Rello and Pop-Vicas 2009). The different viruses can also cause pneumonia such as Rhinovirus, Coronaviruses, Influenza virus, Adenovirus (Castillo-Álvarez and Marzo-Sola 2017; Thursby and Juge 2017).

Gut microbiome

The gut of the human is a natural habitat that harbors a large and dynamic population of microorganism. The term ‘gut microbiota’ is used to describe the large collection of various microorganisms consisting the human gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) that includes the bacteria, archaea, virus, and eukarya (Hollister et al. 2014). The gut microbiome comprises this diverse community of different microorganisms which differ from each other depending upon their location along the length of GI tract (esophagus, stomach, the small and the large intestine with colon at the end) (Aragón et al. 2018). The microbial cell are more than 10 times the eukaryotic cells present in a human body (Min and Rhee 2015; Wang et al. 2017b) with more than 100 trillion microbes present in the human gut alone. These organisms colonize different region of the human gut and influences many aspects of health (Kinross et al. 2008; Lozupone et al. 2012). The stomach, along with the small intestine has presence of very few species of bacteria in comparison to large intestine that contains a more complex and highly dynamic ecosystem of microbes (Brubaker and Wolfe 2017; Moore et al. 2002; Whiteside et al. 2015). The structure of the microbiota depends not only on location but also on a variety of factor such as age, diet, medication, sex, GI infection etc. Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria are four predominant major bacterial phyla found to be present in the human gut (Donaldson et al. 2016; Guarner and Malagelada 2003). The subdominant bacterial phyla that are found in the human gut are Fusobacteria and Verrucomicrobia (Hollister et al. 2014). The microbial genera belonging to Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Eubacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Clostridium, Peptococcus and Ruminococcus are the principal microbes in the human gut, whereas aerobes and the facultative anaerobes namely Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Escherichia, Proteus, etc. are some of the subdominant genera present in the gut of human (Donaldson et al. 2016). In the stomach and the small intestine, the most prevalent bacterial genera are Helicobacter, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Prevotella, Veilonella, Lactobacillus, Actinomyces, Rothia etc. (Dridi et al. 2012). In addition to these bacterial genera, the human gut contains some other pathogenic bacteria like Campylobacter jejuni, Vibrio cholera, Salmonella enteric (Kelesidis and Pothoulakis 2012). There is also presence of various rare microbial taxa which are largely overlooked but can have a great impact on the human physiological functions. Oxalobacter formigenes is an example of a rare microbial species present in the gut microbiota and plays a role in oxalate homeostasis (Sidhu et al. 1999). Methanosphaera stadtmanae and Methanobrevibacter smithii are the dominant archeal species in the gut microbiota along with presence of low-abundance taxa i.e. Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis (Greenblum et al. 2012) and members belonging to the genus Nitrososphaera. The human gut is also inhabited by various eukaryotes although the knowledge regarding this component of the gut is less. They may have a potential role in human health e.g. Saccharomyces boulardii plays a role as a probiotic (Greenblum et al. 2012), whereas giardiasis disease is associated with a rare eukaryote Giardia duodenalis present in the gut (Kinross et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2017b).

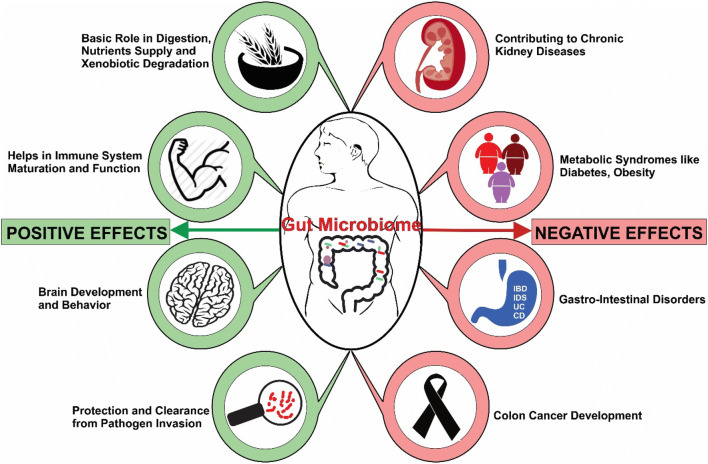

Role of gut microbiome in human health and disease

The gut microbiome affects the host physiology of human notably. Humans and their microbiota of the gut maintains a close relationship beginning right after birth and advances in a concerted and coordinated manner throughout the lifespan of man (Fig. 3). The microbiota of the gut plays a paramount role in both health and disease in a human which depends on the overall state of composition and distribution of different microbial community (Eckburg et al. 2005; Flint et al. 2012; Guarner and Malagelada 2003). Some of them have highly important role in many vital processes including biosynthesis of vitamin and amino acids. They also help in immune development, providing some other essential nutrients, regulating epithelial development, protection against pathogens that help in maintaining the gut health (Guarner and Malagelada 2003; Min and Rhee 2015). In addition, the gut microbiome might be an important factor in certain pathological disorder including colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), multisystem organ failure, cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes etc. (Guarner and Malagelada 2003; Min and Rhee 2015; Yang et al. 2012). Moreover, it has been seen that the trans-domain diversity of microbial gut plays a role in human health and disease with findings showing a direct relationship between kidney stone disease related to alteration on not only the species composition of the bacteria but also fungus, archea and eukayotes in the gut (Flores-Mireles et al. 2015).

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of major steps involved in most widely accepted genomics approach for human associated microbiome studies

Beneficial function of gut microbiota

Metabolic function, trophic function, and protective function are the main benefits of the human gut microbiota (Sheerin 2011).

Metabolic function: The gut microbiome in the humans, helps in the degradation of undigested carbohydrate that includes large polysaccharides such as cellulose, hemicelluloses, pectin; unabsorbed sugar and alcohol which are degraded into various short-chain fatty acids (SCFs) including butyrate, acetate, propionate (Stamm and Norrby 2001). Acetate (with two carbons), propionate (with three carbons) and butyrate (with four carbons) are SCFs used by the epithelial cells of the colon and acts as a major player in the continuation of gut homeostasis. SCFs induce the secretion of small peptides like the glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), which increase nutrient absorption from the intestinal lumen (Cummings et al. 1987). Firmicutes such as Clostridium spp. and Bifidobacterium spp. are the ones responsible for producing SCFs (Elson and Alexander 2015). The gut microbiome also helps in synthesis of vitamins (e.g. Escherichia coli produce Vitamin-K) and help in absorption of ions such as magnesium, iron and calcium (Blottiere et al. 2003).

Trophic function: The principle trophic functions carried out by human gut microflora includes control of proliferation and differentiation of the epithelial along with the development and maintenance of gut homeostasis (Siavoshian et al. 2000). SCFs produced by some gut microbiome can play an essential role in the trophic function of the human gut. The three main SCFs (butyrate, acetate, and propionate) stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of the epithelial cells (Chung and Kasper 2010). However, butyrate serves as a major source of energy for the intestinal epithelial cells that inhibits cell proliferation and stimulates epithelial cell differentiation (Pastorelli et al. 2013). In addition, the human gut microbiome is responsible for development and regulation of gut immune system and this microbiota-driven immune response can help to prevent the inappropriate inflammation development and thus maintain the gut homeostasis (Bernet et al. 1994).

Protective function: The human gut microbiome serves as the first line of defense along with the host defense mechanisms to counter invasion and subsequent infections by various pathogenic microorganisms (Lievin et al. 2000). Resident bacteria of the human gut contribute to the colonization resistance by inhibiting the attachment and entry of pathogenic bacteria for colonization. The attachment and further invasion of cell by pathogenic bacteria is inhibited by Lactobacillus acidophilus LA1 which is a part of the normal microflora of the human gut (D’Argenio and Salvatore 2015). They compete with other pathogenic bacteria for nutrient availability along with production of antimicrobial substances called bacteriocin to obstruct the growth of the competitor. Bifidobacterium strain can produce antimicrobial activity and exert a protective function against pathogenic bacteria (Hall et al. 2017).

Disease associated with gut microbiome

Dysbiosis of gut microbiome in man can cause several diseases in which inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer are the most regular chronic disease.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD): Inflammatory bowel diseases are one of the chronic diseases of the human gastrointestinal tract characterized by inappropriate inflammation in the gut resulting from the genetic risk factors and environmental factors which includes the gut microbiota (Cénit et al. 2014). It is a disease of human GI tract with Crohn’s diseases and ulcerative colitis being the two primary clinical manifestations (Dupont and Dupont 2011). Both are a serious medical disorder but the main difference between these diseases is that in Crohn’s disease the inflammation can occur in any part of the GI tract but in ulcerative colitis, inflammation is limited only to the colon (Cénit et al. 2014). Normal tolerance of the patient to the commensal intestinal microflora is lost and it develops inappropriate immune response that leads to the alteration of intestinal epithelial barrier (Kinross et al. 2008). Patients with IBD have a high concentration of intestinal mucosal secretion of IgG antibody against a broad spectrum of commensal bacteria (Cénit et al. 2014; Marchesi et al. 2016). IgG can activate the complement and the cascade of inflammatory mediator by damaging the intestinal mucosa which is much more than IgA (Wang et al. 2017a). Patients with IBD have diverged bacterial genera associated with gut epithelial surface than healthy human colons. Particularly Bacteroides were found to penetrate the gut epithelial surface but some other bacteria such as Bacteroides fragilis, Clostridium ramosum, Mycobacterium avium subspp paratuberculosis and a number of Proteobacteria including Enterohepatic, Helicobacter, Campylobacter jejuni were also found to be associated with an epithelial surface that causes IBD (Lazarova et al. 2004).

Colorectal cancer: Colorectal cancer refers to cancer of the colon and rectum. In most cases, colorectal cancer begins as a small noncancerous cluster of cells and is named adenomatous polyps and finally this polyp can become colorectal cancer (Ronald 2002; Nielubowicz and Mobley 2010). Colorectal cancer is associated with high consumption of red meat especially processed meat and dietary fat consumption (Guarner and Malagelada 2003). The colonic microbiota synthesizes short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and some other metabolites leading to the development of colorectal cancer (Bingham 1999; Wang et al. 2017b).

The bacteria present in the intestine can play a part in the initiation of colorectal cancer by synthesizing carcinogens (Kostic et al. 2013). The bacterial species that includes Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides stercorisa are associated with high risk of colorectal cancer whereas bacterial species associated with low risk of colorectal cancer are Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus sp. S06 and Eubacterium aerofaciens (Foxman 2013; Mak and Kuo 2006). Fusobacterium nucleatum, a rare microbial species of the gut microbiome is linked with various types of colorectal cancer (Lee et al. 2014).

Urinary system and its microbiome

The urinary system includes a paired kidney and ureters, a bladder, and a urethra. As the anatomy of the urinary system in males and females differ significantly their microbial composition are also different (Foxman 2010). In case of female, the kidney, ureters and bladder are normally sterile but the urethra of the female is usually colonized by different microorganisms. The main microorganisms colonizing the female urethra are Lactobacillus spp., Corynebacterium spp., Fusobacterium spp., Veillonella spp., Escherichia coli, Enterobacteriaceae (Klebsiella, Proteus, Enterobacter), Burkholderia spp., coagulase-negative staphylococci, Bacteroides spp., Gram-positive anaerobic cocci including Peptococcus, Peptostreptococcus, Anaerococcus, Peptoniphilus, Micromonas, Ruminococcus, Coprococcus, Sarcina etc. (Sheerin 2011). In the male, the microbial composition of the urethra is less than the female urethra. The dominant microorganisms of the male urethra are coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Corynebacterium spp., Streptococcus viridans, Gram-positive anaerobic cocci, Mollicute (Judson 1981).

Role of urinary tract microbiome

Urinary tract microbiome can play a role in the maintenance of urinary tract homeostasis. Commensal bacteria present in the urinary tract produce some antimicrobial compound that kills the pathogens (Domingue and Hellstrom 1998) thereby creating a barrier and blocking the pathogen to gain an access to the uroepithelium and compete with pathogens for same resources. Certain bacteria are able to interact with many environmental toxins for instance heavy metals, pesticide, plastic monomer, organic compounds (Collins et al. 2000). In addition, the commensal bacteria of urinary tract might even produce neurotransmitters that can interact with the nervous system to help in proper development of urinary tract (Colgan et al. 2011).

Disease associated with urinary tract microbiome

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the infection affecting any portion along the urinary tract (kidney, ureters, bladder and urethra) (Flores et al. 2002). It is among the most recurrent bacterial infections with around 150 million cases of people getting affected each year worldwide. UTIs are caused by Gram-positive as well as Gram-negative bacteria and certain fungi but species belonging to Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumonia, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, Proteus mirabilis, Candida spp. being the most common agents (Martin 2012; Ravel et al. 2011). Due to their anatomical structure, women have higher chances of encounter to such infection in comparison to male. Cystitis, an infection of the bladder is one of the most common UTI but infection can occur in another part of the urinary tract causing urethritis, prostatitis, pyelonephritis etc. (Cribby et al. 2008).

Cystitis

Cystitis refers specifically to an inflammation of bladder wall and is one of the most common types of urinary infections. Cystitis usually takes place when the bladder, which is generally sterile or microbes free, become infected with bacteria. It affects people of both sexes and all age group (Dover et al. 2008; Fontaine and Taylor-Robinson 1990). The symptom of cystitis includes traces of blood in urine, cloudy and strong-smelling urine, burning sensation during urination, frequent urination. It is not normally a serious condition but may lead to complication if not treated (Anukam et al. 2005; Linhares et al. 2010). Although bacterial infection is the major cause, some noninfectious factors may also cause cystitis such as drug-induced cystitis, chemical cystitis and radiation cystitis.

Urethritis

Urethritis is the most commonly occurring urinary tract infection that causes the inflammation of the urethra. It is a disease transmitted sexually and mainly caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Grice and Segre 2012; Larsen and Monif 2001). Nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) is caused by a variety of bacteria including Chlamydia trichomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Escherichia coli, Gram-positive aerobic cocci Anaerococcus prevotii, Anaerococcus tetradius are also associated with NGU (Judson 1981).

Prostatitis

In men, prostatitis is one of the most common bacterial infections of the urinary tract. It may be an acute bacterial or a chronic bacterial prostatitis which is characterized by one or more symptoms such as pain during urination, impotency, blood in the urine, perineal or scrotal pain (Brotman et al. 2008; Hay et al. 1997). The common urinary tract bacteria that includes Escherichia coli, Proteus spp., and other Enterobacteriaceae are the main cause of the acute form of prostatitis. Chronic bacterial prostatitis is an unusual condition caused mainly by Enterobacteria that infects the prostate gland resulting in swelling and inflammation of the prostate gland. The exogenous pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are associated with chronic bacterial prostatitis (Donders 2010).

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis is a common bacterial infection of renal pelvis and kidney of adult women. Its symptom includes pain on passing of urine, high fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, blood in the urine (Bhute et al. 2017). Escherichia coli and Enterococcus faecalis are common bacterial organisms but Pseudomonas aeruginosa and various species belonging to Klebsiella are also associated with pyelonephritis. Particularly patients with diabetes develop emphysematous pyelonephritis which is a fatal infection (Young and Jewell 2001).

Vaginal microbiome

The normal vaginal microbiota has influential role in immunity, physiology and nutrition with a great majority of these bacteria existing in a mutualistic association with humans and few being opportunistic pathogens with a potential to cause diseases (Hetticarachchi et al. 2010). The main microbiome present in the vagina are Lactobacillus spp., Staphylococcus spp., Enterococcus spp., Bifidobacterium spp., Streptococcus spp., Corynebacterium spp., Propionibacterium spp., Bacteroides spp., Porphyromonas spp., Clostridium spp., Veillonella spp., Fusobacterium spp., Prevotella spp., Mycoplasma spp., and Gram-positive anaerobic cocci, Candida albicans (Dhakar and Pandey 2016).

Beneficial function of the vaginal microbiome

The microbiota associated with the vagina has a great impact on health and disease as they form a mutualistic relationship with the host. The microbial species that are associated with the vagina play a significant role in maintaining health (Suryavanshi et al. 2016) and prevention of infection by producing antimicrobial compounds e.g. bacteriocins, hydrogen peroxide, organic acid like lactic acid and acetic acid and effectively protecting the vagina against pathogens (Suryavanshi et al. 2016). The microbiota of vagina is predominantly the species of Lactobacillus which includes Lactobacillus crispatus, Lactobacillus jensenii, Lactobacillus iners, Lactobacillus gasseri followed by Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus brevis, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus vaginalis, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, Lactobacillus salivarius, Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus rhamnosus (Suryavanshi et al. 2016). The vaginal microbiome also helps in prevention of multiple diseases including yeast infection, sexually transmitted infection, bacterial vaginosis (BV), urinary tract infection (Suryavanshi et al. 2016).

Disease associated with vaginal microbiome

Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV), highly prevalent disorder of vagina in reproductively active women is one common cause of abnormal vaginal discharge (Suryavanshi et al. 2016). Menstrual blood, douching of vagina, new sexual partner, smoking and lack of use of condom are the common risk factor associated with vaginosis (Suryavanshi et al. 2016). BV is characterized by high vaginal pH due to the overgrowth of, predominantly, the anaerobic organisms like Prevotella spp., Peptostreptococci, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma spp. and Mobiluncus spp. leading to the replacement of lactobacilli (Suryavanshi et al. 2016). BV is a disorder caused by ecological imbalance of the microbiome of the vagina. It is linked with numerous health issues which includes premature birth and acquiring of sexually transmitted diseases, e.g. Chlamydia trachomatis, HIV, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and affecting millions of women worldwide annually (Suryavanshi et al. 2016).

Vaginal candidiasis

The fungus Candida causes vaginal candidiasis with Candida albicans being the most commonly associated organism (Suryavanshi et al. 2016). Lactobacillus spp. is a microbiota of the vagina that produces acid which prevents the fungal infection. But too much yeast in the vagina can reduce the balance of Lactobacillus spp. and causes vaginal infection. Itching and irritation of the vagina along with swelling and redness of the vulva, burning sensation during urination and watery vaginal discharge are the common symptoms of vaginal candidiasis. Candida parapsilosis and Candida glabrata are associated with non-albicans candidiasis. As these organisms are also found in natural acidic environment, they might use similar mechanism to get adapted to the acidic environment of the vagina and cause (Suryavanshi et al. 2016).

Conclusion and Future perspective

The large and diverse groups of microorganisms that resides various parts of the human body have a highly coevolved relationship with the human health. Although a large number of these microbes perform functions that are pivotal for host physiology it appears that the variability of the microbiome far exceeds the genetic variation of human. In this review, we have presented the updates on human microbiota and its relationship with human health by exploring the six body sites including skin, oral cavity, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, and vagina. Among these sites, the microbiota of gastrointestinal tract is found to be continuously evolving during the life span of the host in contrast to other body sites. Recent developments in the field of microbiome sequencing projects have realized the high complexity of the different microbial communities present in various sites in human body. They have confirmed the importance of the human-microbiota ecosystems in promotion of health and various disease-causing processes. With continually advancing efforts in the sequencing techniques of the microbiota, we now have infinite opportunities to gain new knowledge about the microbiome and its relationship with human, especially in understanding as to how this interaction contributes to disease in the skin, respiratory tract, oral cavity, GI tract, urinary tract. Moreover, speculative role of gut microbes for the other metabolic disorders like type-2-diabetes and hyperoxaluria has been characterized in Indian populations (Suryavanshi et al. 2016). Fermicutes population dynamics would be the culprit for metabolic dysbiosis of gut ecology and the correction strategies were hypotheses further on spiking the exogenous flora to the system. Development and continuous updating of increasingly powerful tools to extract meaningful patterns from this wealth of data have further added to the present pool of knowledge.

Recent advances in microbiome sequencing process and omics technology such as metagenomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics will further provide fundamental information about the human-microbiota ecosystem in health-promoting or disease-causing process. These studies will provide further insight into the human-microbiome interaction that eventually leads to therapies to maintain human health and to treat a variety of diseases. In addition, the probiotics are one of the most important therapeutic strategy for various conditions including IBD, diabetes, and it may be important for future management of skin, oral, respiratory, GI and other diseases. Future advances will clarify the human-microbiome interactions and microbiome based strategies for diagnosis and treatment of diseases which can be used in the future for personalized medicine work.

Acknowledgement

This Review has been a part of Master degree dissertation work of ED. The authors would like to thank the Department of Microbiology, Sikkim University, for providing the computational infrastructure and central library facilities for procuring references and plagiarism analysis (URKUND: Plagiarism Detection Software).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Elakshi Dekaboruah and Mangesh Suryavanshi equally contributed to this work.

References

- Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(11):5721–5732. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar-Pulido V, Huang W, Suarez-Ulloa V, Cickovski T, Mathee K, Narasimhan G. Metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and metabolomics approaches for microbiome analysis: supplementary issue: bioinformatics methods and applications for big metagenomics data. Evol Bioinform. 2016;12:EBO-S36436. doi: 10.4137/EBO.S36436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertsen M, Hugenholtz P, Skarshewski A, Nielsen KL, Tyson GW, Nielsen PH. Genome sequences of rare, uncultured bacteria obtained by differential coverage binning of multiple metagenomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(6):533. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anukam KC, Osazuwa EO, Ahonkhai I, Reid G. 16S rRNA gene sequence and phylogenetic tree of Lactobacillus species from the vagina of healthy Nigerian women. Afr Jr Biotechnol. 2005;4(11):1222–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón IM, Herrera-Imbroda B, Queipo-Ortuño MI, Castillo E, Del Moral JSG, Gómez-Millán J, Yucel G, Lara MF. The urinary tract microbiome in health and disease. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4(1):128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barka EA, Vatsa P, Sanchez L, Gaveau-Vaillant N, Jacquard C, Klenk HP, van Wezel GP. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80(1):1–43. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00019-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belizário JE, Napolitano M. Human microbiomes and their roles in dysbiosis, common diseases, and novel therapeutic approaches. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1050. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta-Piccoli BC, Sauvain MJ, Gal I, Schibler A, Saurenmann T, Kressebuch H, Bianchetti MG. Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome in childhood: a report of ten cases and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159(8):594–601. doi: 10.1007/s004310000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernet MF, Brassart D, Neeser JR, Servin AL. Lactobacillus acidophilus LA 1 binds to cultured human intestinal cell lines and inhibits cell attachment and cell invasion by enterovirulent bacteria. Gut. 1994;35(4):483–489. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti R, Grimm DG. Current challenges and best-practice protocols for microbiome analysis. Brief Bioinform. 2019 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt AP, Redinbo MR, Bultman SJ. The role of the microbiome in cancer development and therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(4):326–344. doi: 10.3322/caac.21398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhute SS, Suryavanshi MV, Joshi SM, Yajnik CS, Shouche YS, Ghaskadbi SS. Gut microbial diversity assessment of Indian type-2-diabetics reveals alterations in eubacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:214. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biavati B, Vescovo M, Torriani S, Bottazzi V. Bifidobacteria: history, ecology, physiology and applications. Ann Microbiol. 2000;50(2):117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bibel DJ, Aly R, Bayles C, Strauss WG, Shinefield HR, Maibach HI. Competitive adherence as a mechanism of bacterial interference. Can J Microbiol. 1983;29(6):700–703. doi: 10.1139/m83-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickhart DM, Watson M, Koren S, Panke-Buisse K, Cersosimo LM, Press MO, et al. Assignment of virus and antimicrobial resistance genes to microbial hosts in a complex microbial community by combined long-read assembly and proximity ligation. Genome Biol. 2019;20:153. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1760-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesbroek G, Tsivtsivadze E, Sanders EA, Montijn R, Veenhoven RH, Keijser BJ, Bogaert D. Early respiratory microbiota composition determines bacterial succession patterns and respiratory health in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(11):1283–1292. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1240OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham SA. High-meat diets and cancer risk. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58(2):243–248. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Míguez A, Gutiérrez-Jácome A, Fdez-Riverola F, Lourenço A, Sánchez B (2017) MAHMI database: a comprehensive MetaHit-based resource for the study of the mechanism of action of the human microbiota. Database 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Blottiere HM, Buecher B, Galmiche JP, Cherbut C. Molecular analysis of the effect of short-chain fatty acids on intestinal cell proliferation. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62(1):101–106. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch AA, Biesbroek G, Trzcinski K, Sanders EA, Bogaert D. Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(1):e1003057. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley PH, Pollard KS. Proteobacteria explain significant functional variability in the human gut microbiome. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0244-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes R, Sikyta B. Influence of pH on the growth characteristics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in continuous culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1967;15(2):224–227. doi: 10.1128/am.15.2.224-227.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman RM, Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, Andrews WW, Schwebke JR, Zhang J, Yu KF, Zenilman JM, Scharfstein DO. A longitudinal study of vaginal douching and bacterial vaginosis—a marginal structural modeling analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(2):188–196. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker L, Wolfe AJ. The female urinary microbiota, urinary health and common urinary disorders. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5(2):34. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.11.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Álvarez F, Marzo-Sola ME. Role of intestinal microbiota in the development of multiple sclerosis. Neurología (English Edition) 2017;32(3):175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénit MC, Matzaraki V, Tigchelaar EF, Zhernakova A. Rapidly expanding knowledge on the role of the gut microbiome in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Basis Dis. 2014;1842(10):1981–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Yu WH, Izard J, Baranova OV, Lakshmanan A, Dewhirst FE (2010) The Human Oral Microbiome Database: a web accessible resource for investigating oral microbe taxonomic and genomic information. Database 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chiller K, Selkin BA, Murakawa GJ. Skin microflora and bacterial infections of the skin. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2001;6(3):170–174. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chira S, Miller LG. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common identified cause of cellulitis: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(3):313–317. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809990483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisti MJ, Tebruegge M, La Vincente S, Graham SM, Duke T. Pneumonia in severely malnourished children in developing countries–mortality risk, aetiology and validity of WHO clinical signs: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(10):1173–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I, Blaser MJ. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(4):260–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Kasper DL. Microbiota-stimulated immune mechanisms to maintain gut homeostasis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(4):455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan R, Williams M, Johnson JR. Diagnosis and treatment of acute pyelonephritis in women. Am Fam Phys. 2011;84(5):519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]