Abstract

Progress in genomic analysis has resulted in the proposal that the intestinal microbiota is a crucial environmental factor in the development of multifactorial diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel diseases represented by Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Dysregulated gut microbiome contributes to the pathogenesis of such disorders; however, there are few effective treatments for controlling only disease-mediating bacteria. Here, we review current knowledge about the intestinal microbiome in health and disease, and discuss a regulatory strategy using a parenteral vaccine with emulsified curdlan and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides, which we have recently developed. Unlike other conventional injectable immunizations, our vaccine contributes to the induction of antigen-specific systemic and mucosal immunity. This vaccine strategy can prevent infectious diseases such as Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, and control metabolic symptoms mediated by intestinal bacteria (e.g. Clostridium ramosum) by induction of high titers of antigen-specific IgA at target mucosal sites. In the future, our vaccination approach could be an effective therapy for common infectious diseases and dysbiosis-related disorders that have been difficult to control so far.

Keywords: Dysbiosis, IgA, Microbiome, Mucosal immunity, Pathobiont, Vaccine

Core tip: How to control intestinal pathogenic bacteria that mediate multifactorial diseases is a major concern worldwide. There are few methods for controlling only intestinal pathogenic bacteria; therefore, we have developed a prime–boost type, next-generation mucosal vaccine, and have used it for control of bacterial intestinal diseases. This vaccine can contribute to prevention of Clostridium ramosum-mediated obesity. Thus, this approach might be useful for protecting against microbe-associated disorders of the intestine.

INTRODUCTION

With the rapid progress of next-generation sequencing and genome analysis technology, human genome analysis has ended, and the focus has shifted to research on commensal microbiomes[1-8]. Body sites that are exposed to a wide variety of external antigens through mucosal sites, such as the respiratory organs and gastrointestinal tract, are constantly colonized with microorganisms, resulting in a symbiotic relationship. If this relationship is broken, the host immune response to microorganisms is distorted, sometimes causing disease. Dysbiosis, which is defined as an imbalance in the repertoire of the intestinal microbiota, is associated with many disorders in humans[9-11]. Therefore, novel strategies to control dysbiosis-associated diseases by attenuating the function of related microorganisms are necessary.

Antibiotics, which were first deployed in 1910, have drastically changed our lives[12]. In particular, penicillin discovered in 1928 contributed to the discovery of naturally occurring antibiotics. Antibiotics have extended our lifespans by > 20 years. However, a rapid increase in multidrug-resistant bacteria has arisen because of overuse and inappropriate consumption and application of antibiotics, which reveals that antibiotics are not a panacea for infectious diseases[13,14]. In addition, antibiotics sometimes cause dysbiosis and can lead to diseases such as Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infection[15]. Thus, although antibiotics are available for killing disease-specific commensal bacteria, they are not suitable for eliminating only pathogens.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), an effective therapy for dysbiosis-related diseases such as C. difficile infection, has been shown to improve aberrant intestinal microbiota[16,17]. Feces from healthy individuals, which are considered relatively safe, are usually used for FMT. However, it was recently reported that antibiotic-resistant bacteria from donor feces were transferred to recipients and induced bacteremia[18]. This is an emergency issue and FMT is not now a recommended regimen. In fact, elimination of only pathobionts through the intestinal mucosa is difficult; therefore, development of novel methods to control dysbiosis-related diseases by attenuating the function of pathobionts is strongly desired.

In this review, we present current knowledge about the intestinal microbiome in health and disease, and discuss a prime–boost type, next-generation mucosal vaccine that we have recently developed and reported for control of disease mediated by intestinal bacteria.

INTESTINAL MICROBIOME IN HEALTH AND DISEASE

Intestinal commensal microbes have primarily been analyzed through single bacterial species isolation. Since most enteric bacteria do not like aerobic conditions, it has been difficult to culture them. However, advances in culture-independent technologies such as next-generation sequencing have shown the dynamics of the human intestinal microbiota[9,19]. For example, trillions of intestinal microbes reside in the gastrointestinal tract and dysbiosis is correlated with diseases such as obesity[20-22], diabetes[23-25], rheumatoid arthritis (RA)[26-31], and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis[32]. Therefore, in addition to the current best treatment, it is suggested that controlling dysbiosis may improve these diseases.

It is widely accepted that metabolic diseases, such as obesity and diabetes, are intimately correlated with diet and dysbiosis[22,33]. Germ-free (GF) mice do not develop western-diet-induced obesity[34-36]. It was also shown in 2006 that colonization of GF mice with intestinal microbiota from obese mice led to a significantly greater increase in total body fat than colonization with microbiota from lean mice[21]. This suggests a strong association between the intestinal microbiota and host metabolism. The intestinal microbiome from obese mice and humans has a significantly higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (F/B ratio) than that from their lean counterparts[21,37-40]. In addition, the bacterial diversity is lower in the microbiota from obese than lean individuals[39,41]. However, other studies have shown no difference in the F/B ratio between obese and lean individuals[42-46]. Therefore, although the diversity in obese individuals is low compared with that in lean individuals, the correlation between obesity and the F/B ratio is unclear.

There is an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in obesity; therefore, dysbiosis might also influence type 2 diabetes. Previous reports have shown that disorder of intestinal carbohydrate metabolism and low-grade gut inflammation cause insulin resistance[47-49]. A reduced abundance of short chain fatty acids such as butyrate is associated with type 2 diabetes[50]. Vrieze et al[51] showed that FMT improved insulin resistance in individuals with metabolic syndrome by altered levels of butyrate-producing intestinal bacteria, indicating that gut microorganisms might be developed as therapeutic tools in the future.

RA is a systemic inflammatory disorder including in polyarthritis that leads to joint destruction. Although both genetic and environmental factors are involved in the pathogenesis of RA, intestinal microbiota analysis has recently attracted much attention, along with single nucleotide polymorphism analysis. When mice are reared in GF conditions, arthritis does not develop, indicating that intestinal microbiota is related to onset of arthritis[28,52-54]. Abdollahi-Roodsaz et al[53] showed that interleukin-1 receptor antagonist knockout mice do not spontaneously develop T-cell-mediated arthritis under GF conditions. However, they do develop arthritis under specific-pathogen-free conditions, and monocolonization of the mice with Lactobacillus bifidus induces arthritis[53]. Matsumoto et al[55] also showed that K/BxN T-cell receptor transgenic mice develop arthritis under specific-pathogen-free conditions, but not GF conditions, and monocolonization of the mice with segmented filamentous bacteria induces arthritis. Previous studies have shown that composition of the microbiota is altered in early RA[26,28,56]. In the preclinical stages of RA, Prevotella species such as Prevotella copri (P. copri) are dominant in the intestine. Maeda et al[28] showed that microbiota isolated from RA patients whose fecal bacteria contained high levels of P. copri contributes to the development of Th17-dependent arthritis, and mono-colonization of SKG mice with P. copri is sufficient to induce arthritis. Thus, although more precise investigations are needed to determine which bacterium is a target for RA treatment, it is strongly suggested that there are intestinal pathogens that are related to the pathogenesis of human RA.

IBDs are increasing in incidence worldwide[57]. Also in Japan, the numbers of IBD patients have rapidly increased over the past 30 years, suggesting that in addition to genetic predisposition, environmental factors such as dysbiosis are more involved in the development of IBDs[58]. Various changes in the intestinal microbiota have been reported in IBD patients[59-61]. The advent of next-generation sequencing has revealed a range of altered microbiota in the intestine. However, a common problem is that it is unclear whether the dysbiosis observed in IBD patients is a cause or a consequence of intestinal inflammation. Given the complicated relationships between the intestinal immune system and gut microbiota, further studies are needed to elucidate the pathogenesis of IBDs and develop more effective treatments.

PRIME–BOOST TYPE MUCOSAL VACCINE

Conventional injectable vaccines, including subcutaneous vaccines, have the ability to induce antigen-specific IgG, maintain antigen-specific immune memory, and contribute to prevention of severe infection[62-64]. Pediatric vaccination is a key factor in protection against many life-threatening infections[64]. However, despite progress in vaccine technology, many infections remain incompletely controlled in both humans and animals worldwide.

Mucosal immune responses are thought to be effective for prevention of infection because foreign antigens, such as microorganisms and food antigens, enter the host through mucosal surfaces[65-69]. In the mucosal sites, secretory IgA (SIgA) plays an important role in regulating intestinal health and disease prevention[70-78]. The major functions of IgA are (1) prevention of adherence, colonization, and invasion of pathogenic microorganisms that invade the mucosal surface; (2) neutralizing effect on toxins and enzymes produced by pathogenic microorganisms; (3) capturing pathogenic microorganisms in the mucus layer; and (4) antimicrobial activity. Only limited numbers of mucosal vaccines are available to date; therefore, a new mucosal vaccine strategy is strongly desired for induction of beneficial systemic immune responses.

IgA is the most abundant antibody in mucosal secretory components. In the intestinal mucosa, there are two types of IgA production mechanisms, represented by T-cell-dependent and T-cell-independent immune responses[79-82]. In the gut, T-cell-dependent antibody responses are involved in activation of B cells by antigen in the organized lymphoid tissue of Peyer’s patches, mesenteric lymph nodes and isolated lymphoid follicles[82-84]. It has been shown that both CD40L and transforming growth factor-β1 are essential for the induction of T-cell-dependent IgA class switching[85]. In contrast, T-cell-independent IgA class switch recombination occurs in B1 cells of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), where IgA is constitutively induced by stimulation with commensal bacteria[82].

GALT, such as Peyer’s patches and isolated lymphoid follicles, is the primary site for IgA induction[86,87]. It has been reported that antigen-specific IgA-producing B cells develop in GALTs with the aid of GALT-dendritic cells (DCs). It is notable that retinoic acid synthesized by GALT-DCs can contribute to IgA synthesis[87-89]. GALT-DCs are also able to imprint gut-homing chemokine receptors such as α4β7 integrin and C-C chemokine receptor type 9 on B and T cells, which is an essential process for lymphocyte migration to the intestines[90].

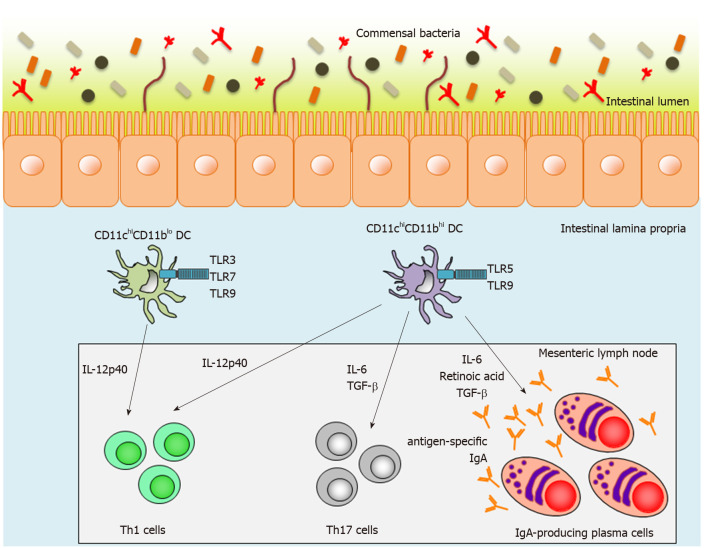

Intestinal lamina propria DCs (LPDCs) are also crucial inducers of SIgA-producing B cells in a T-cell-independent manner. We have previously reported two subsets of small-intestinal LPDCs based on their differential CD11c and CD11b expression patterns: CD11chiCD11blo LPDCs and CD11chiCD11bhi LPDCs[91-93] (Figure 1). CD11chiCD11bhi intestinal LPDCs express the gene encoding the retinoic-acid-converting enzyme, Raldh2, and are able to induce antigen-specific SIgA as well as systemic immunity mediated by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 5 or 9 stimulation[91] (Figure 1). In contrast to CD11chiCD11bhi LPDCs, CD11chiCD11blo LPDCs express TLR3, TLR7 and TLR9, which recognize dsRNA, ssRNA, and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs), respectively[93] (Figure 1). They do not express Raldh2 and are not involved in IgA synthesis in the small-intestinal lamina propria[93]. In addition, high titers of antigen-specific IgA were detected in fecal extracts from antigen-loaded CD11chiCD11bhi LPDC-immunized mice[93]. Accordingly, CD11chiCD11bhi LPDCs are considered to be an ideal target for a mucosal vaccine, but it has thus far been technically difficult to induce antigen-specific mucosal immunity using conventional injectable vaccines.

Figure 1.

Function of two distinct lamina propria dendritic cells in the small intestine. Mouse small-intestinal lamina propria dendritic cells (LPDCs) are divided into two subsets on the basis of CD11c and CD11b expression. CD11chiCD11blo LPDCs express Toll-like receptor (TLR) 3, TLR7 and TLR9, whereas CD11chiCD11bhi LPDCs express TLR5 and TLR9. After TLR stimulation, activated CD11chiCD11bhi LPDCs can produce interleukin (IL)-12p40, IL-6, transforming growth factor-β and retinoic acid, and subsequently induce antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 responses and antigen-specific-IgA-producing plasma cells. In contrast to CD11chiCD11bhi LPDCs, activated CD11chiCD11blo LPDCs can induce antigen-specific Th1 responses, but not antigen-specific Th17 responses and antigen-specific-IgA-producing plasma cells. TLR: Toll-like receptor; TGF: Transforming growth factor; IL: Interleukin; DC: Dendritic cell.

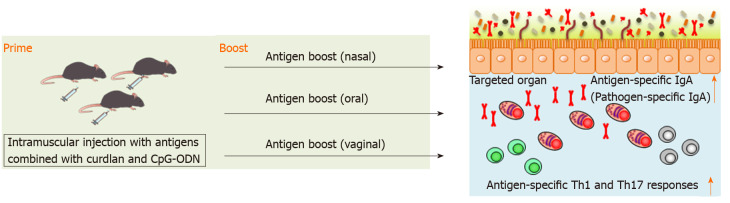

We have recently reported that splenic DCs stimulated with both curdlan, dectin-1 ligand, and CpG-ODN, TLR9 ligand, successfully induced antigen-specific fecal IgA as well as antigen-specific serum IgG and splenic Th1 and Th17 responses in mice[94]. This indicates that combination of curdlan and CpG-ODN is available as an adjuvant of parenteral vaccination to induce broad functional immunity against mucosal antigens. We found that intramuscular immunization with the combination of curdlan and CpG-ODN emulsified with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant induced antigen-specific fecal IgA as well as serum IgG and splenic Th1 and Th17 responses[94] (Figure 2). However, although antigen-specific IgG in serum was continuously detected after prime injection, antigen-specific IgA production in feces was only transiently detected by parenteral immunization with curdlan + CpG-ODN[94]. Therefore, additional immunization, for example, boosting, to induce more durable mucosal immunity at targeted mucosal sites is thought to be necessary. We have demonstrated that after oral, nasal or vaginal antigen administration, high titers of long-lasting antigen-specific intestinal, lung or vaginal IgA are inducible[94] (Figure 2). Also, this prime–boost vaccine is effective against cholera-toxin-induced diarrhea and Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) infection[94]. Thus, we established intramuscular antigen injection adjuvanted with curdlan + CpG-ODN and subsequent antigen administration on target mucosal sites (prime–boost vaccination) as a new vaccine strategy capable of inducing strong and durable systemic and mucosal immunity.

Figure 2.

Scheme of antigen-specific immune responses by prime–boost vaccination. Parenteral immunization with antigen emulsified in curdlan and CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides induces antigen-specific fecal IgA as well as serum IgG and splenic Th1 and Th17 responses. Once primed, high titers of long-lasting antigen-specific lung, intestinal, or vaginal IgA are induced after nasal, oral, or vaginal antigen administration, respectively. Also, antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 responses are induced at the targeted organs. CpG-ODN: CpG oligodeoxynucleotides.

FUTURE REGULATION OF DYSBIOSIS-ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Intestinal dysfunction has been correlated with multifactorial diseases[9], suggesting that the mucosal immune responses provide a solid causal link between pathological symptoms in the host and disease-associated dysbiosis. Several studies have identified some pathobionts, such as Clostridium ramosum (C. ramosum)[95], P. copri[26,28], Helicobacter pylori[96], adherent invasive Escherichia coli[97], Clostridium scindens[98], and Enterococcus gallinarum[99]. Therefore, regulating the function of disease-associated pathobionts can lead to prevention or treatment of dysbiosis-related disorders. However, antibiotics are not suitable for eliminating only pathogens because they have the possibility to induce dysbiosis or multidrug-resistant bacteria[100].

C. ramosum is an obligate anaerobic bacterium first identified in an appendicitis patient in 1898 and widely inhabits the human gastrointestinal tract. Increased levels of C. ramosum are associated with human obesity and diabetes[20,23]. C. ramosum is also associated with clinical symptoms of metabolic disorders in gnotobiotic mice colonized with C. ramosum alone and a simplified human intestinal microbiome containing C. ramosum. Furthermore, it has been shown that the numbers of C. ramosum are higher in mice fed a high-fat compared with normal-fat diet, and this results in increased expression of Slc2a2 in the small-intestinal mucosa[95]. Therefore, we recently applied our prime–boost vaccination to control C. ramosum-mediated diseases. Our vaccine for C. ramosum significantly inhibited body weight gain and the increased levels of C. ramosum in the intestinal mucosa under a high-fat diet[94]. It also resulted in decreased expression of Slc2a2 and subsequently ameliorated glucose intolerance[94]. It is notable that this immunization strategy did not induce dysbiosis[94]. Thus, it might be effective for preventing C. ramosum-associated obesity and diabetes.

Until now, there have been few methods that can induce high titers of antigen-specific IgA at target mucosal sites using an injection-type mucosal vaccine. It is noteworthy that we have developed a next-generation prime–boost mucosal vaccine using curdlan and CpG-ODN, and used it for control of diseases such as S. pneumoniae infection, and other diseases mediated by intestinal bacteria[94]. With the advent of gnotobiotic technology, function of the intestinal microbiome has been revealed. However, since there are few methods for specifically attenuating the function of intestinal bacteria, many diseases mediated by intestinal bacteria are still not fully elucidated. Our vaccination is the world’s first immunization strategy, and has the potential to be an excellent technique for functional analysis of intestinal bacteria.

CONCLUSION

As the link between various diseases and aberrant intestinal microbiota becomes apparent, there is an urgent need to develop and disseminate control strategies for dysbiosis in addition to existing effective treatments. Antibiotics are not specific to pathobionts and may induce dysbiosis that can lead to disease. Attempts have also been made to control diseases mediated by intestinal bacteria using FMT or probiotic treatments, but these are established and effective treatments. An important treatment for diseases mediated by intestinal bacteria is to improve the underlying disease without inducing new dysbiosis. Vaccination with curdlan + CpG-ODN and antigens and subsequent antigen administration can effectively induce antigen-specific systemic and mucosal immunity. This prime–boost vaccine method has been patented in Japan and prime–boost vaccines targeting various infectious diseases are being developed for future human prescription. There is no doubt that the vaccine technology discussed in this review will become a new treatment in the next generation of antimicrobial strategies. Further analysis of the gut microbiota is necessary, but we are eagerly looking forward to developing pathobiont-specific treatments for human diseases in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank K Ogawa, M Maeda, and K Suetsugu for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 27, 2019

First decision: February 14, 2020

Article in press: May 23, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abushady EAE S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Kosuke Fujimoto, Department of Immunology and Genomics, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka 545-8585, Japan; Division of Innate Immune Regulation, International Research and Development Center for Mucosal Vaccines, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan; Division of Metagenome Medicine, Human Genome Center, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan.

Satoshi Uematsu, Department of Immunology and Genomics, Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka 545-8585, Japan; Division of Innate Immune Regulation, International Research and Development Center for Mucosal Vaccines, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan; Division of Metagenome Medicine, Human Genome Center, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan; Collaborative Research Institute for Innovative Microbiology, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan. uematsu.satoshi@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Cho I, Blaser MJ. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:260–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gajer P, Brotman RM, Bai G, Sakamoto J, Schütte UM, Zhong X, Koenig SS, Fu L, Ma ZS, Zhou X, Abdo Z, Forney LJ, Ravel J. Temporal dynamics of the human vaginal microbiota. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:132ra52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinross JM, Darzi AW, Nicholson JK. Gut microbiome-host interactions in health and disease. Genome Med. 2011;3:14. doi: 10.1186/gm228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2369–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1600266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma B, Forney LJ, Ravel J. Vaginal microbiome: rethinking health and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:371–389. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pflughoeft KJ, Versalovic J. Human microbiome in health and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:99–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wade WG. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shreiner AB, Kao JY, Young VB. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31:69–75. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilbert JA, Quinn RA, Debelius J, Xu ZZ, Morton J, Garg N, Jansson JK, Dorrestein PC, Knight R. Microbiome-wide association studies link dynamic microbial consortia to disease. Nature. 2016;535:94–103. doi: 10.1038/nature18850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirzaei MK, Maurice CF. Ménage à trois in the human gut: interactions between host, bacteria and phages. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:397–408. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:341–352. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchings MI, Truman AW, Wilkinson B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;51:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molton JS, Tambyah PA, Ang BS, Ling ML, Fisher DA. The global spread of healthcare-associated multidrug-resistant bacteria: a perspective from Asia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1310–1318. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antharam VC, Li EC, Ishmael A, Sharma A, Mai V, Rand KH, Wang GP. Intestinal dysbiosis and depletion of butyrogenic bacteria in Clostridium difficile infection and nosocomial diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2884–2892. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00845-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakken JS, Borody T, Brandt LJ, Brill JV, Demarco DC, Franzos MA, Kelly C, Khoruts A, Louie T, Martinelli LP, Moore TA, Russell G, Surawicz C Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Workgroup. Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:1044–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borody TJ, Khoruts A. Fecal microbiota transplantation and emerging applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:88–96. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeFilipp Z, Bloom PP, Torres Soto M, Mansour MK, Sater MRA, Huntley MH, Turbett S, Chung RT, Chen YB, Hohmann EL. Drug-Resistant E. coli Bacteremia Transmitted by Fecal Microbiota Transplant. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2043–2050. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thaiss CA, Zmora N, Levy M, Elinav E. The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature. 2016;535:65–74. doi: 10.1038/nature18847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, Prifti E, Hildebrand F, Falony G, Almeida M, Arumugam M, Batto JM, Kennedy S, Leonard P, Li J, Burgdorf K, Grarup N, Jørgensen T, Brandslund I, Nielsen HB, Juncker AS, Bertalan M, Levenez F, Pons N, Rasmussen S, Sunagawa S, Tap J, Tims S, Zoetendal EG, Brunak S, Clément K, Doré J, Kleerebezem M, Kristiansen K, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, de Vos WM, Zucker JD, Raes J, Hansen T MetaHIT consortium, Bork P, Wang J, Ehrlich SD, Pedersen O. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nature12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonnenburg JL, Bäckhed F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature. 2016;535:56–64. doi: 10.1038/nature18846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karlsson FH, Tremaroli V, Nookaew I, Bergström G, Behre CJ, Fagerberg B, Nielsen J, Bäckhed F. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, Vatanen T, Hyötyläinen T, Hämäläinen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Pöhö P, Mattila I, Lähdesmäki H, Franzosa EA, Vaarala O, de Goffau M, Harmsen H, Ilonen J, Virtanen SM, Clish CB, Orešič M, Huttenhower C, Knip M DIABIMMUNE Study Group, Xavier RJ. The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:260–273. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, Stranges PB, Avanesyan L, Stonebraker AC, Hu C, Wong FS, Szot GL, Bluestone JA, Gordon JI, Chervonsky AV. Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development of Type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2008;455:1109–1113. doi: 10.1038/nature07336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, Segata N, Ubeda C, Bielski C, Rostron T, Cerundolo V, Pamer EG, Abramson SB, Huttenhower C, Littman DR. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. Elife. 2013;2:e01202. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scher JU, Joshua V, Artacho A, Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Öckinger J, Kullberg S, Sköld M, Eklund A, Grunewald J, Clemente JC, Ubeda C, Segal LN, Catrina AI. The lung microbiota in early rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Microbiome. 2016;4:60. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0206-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maeda Y, Kurakawa T, Umemoto E, Motooka D, Ito Y, Gotoh K, Hirota K, Matsushita M, Furuta Y, Narazaki M, Sakaguchi N, Kayama H, Nakamura S, Iida T, Saeki Y, Kumanogoh A, Sakaguchi S, Takeda K. Dysbiosis Contributes to Arthritis Development via Activation of Autoreactive T Cells in the Intestine. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2646–2661. doi: 10.1002/art.39783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips R. Rheumatoid arthritis: Microbiome reflects status of RA and response to therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:502. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishikawa T, Maeda Y, Nii T, Motooka D, Matsumoto Y, Matsushita M, Matsuoka H, Yoshimura M, Kawada S, Teshigawara S, Oguro E, Okita Y, Kawamoto K, Higa S, Hirano T, Narazaki M, Ogata A, Saeki Y, Nakamura S, Inohara H, Kumanogoh A, Takeda K, Okada Y. Metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiome revealed novel aetiology of rheumatoid arthritis in the Japanese population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:103–111. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda Y, Takeda K. Host-microbiota interactions in rheumatoid arthritis. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51:1–6. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0283-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rigottier-Gois L. Dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel diseases: the oxygen hypothesis. ISME J. 2013;7:1256–1261. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L. The gut microbiota and obesity: from correlation to causality. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:639–647. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bäckhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding S, Chi MM, Scull BP, Rigby R, Schwerbrock NM, Magness S, Jobin C, Lund PK. High-fat diet: bacteria interactions promote intestinal inflammation which precedes and correlates with obesity and insulin resistance in mouse. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabot S, Membrez M, Bruneau A, Gérard P, Harach T, Moser M, Raymond F, Mansourian R, Chou CJ. Germ-free C57BL/6J mice are resistant to high-fat-diet-induced insulin resistance and have altered cholesterol metabolism. FASEB J. 2010;24:4948–4959. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ley RE, Bäckhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11070–11075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504978102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, Egholm M, Henrissat B, Heath AC, Knight R, Gordon JI. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, Yu Y, Parameswaran P, Crowell MD, Wing R, Rittmann BE, Krajmalnik-Brown R. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2365–2370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schäfer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, Donus C, Hardt PD. Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:190–195. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, Trinidad C, Bogardus C, Gordon JI, Krakoff J. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:58–65. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balamurugan R, George G, Kabeerdoss J, Hepsiba J, Chandragunasekaran AM, Ramakrishna BS. Quantitative differences in intestinal Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in obese Indian children. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:335–338. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang C, Zhang M, Pang X, Zhao Y, Wang L, Zhao L. Structural resilience of the gut microbiota in adult mice under high-fat dietary perturbations. ISME J. 2012;6:1848–1857. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang C, Zhang M, Wang S, Han R, Cao Y, Hua W, Mao Y, Zhang X, Pang X, Wei C, Zhao G, Chen Y, Zhao L. Interactions between gut microbiota, host genetics and diet relevant to development of metabolic syndromes in mice. ISME J. 2010;4:232–241. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Olden C, Groen AK, Nieuwdorp M. Role of Intestinal Microbiome in Lipid and Glucose Metabolism in Diabetes Mellitus. Clin Ther. 2015;37:1172–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devaraj S, Hemarajata P, Versalovic J. The human gut microbiome and body metabolism: implications for obesity and diabetes. Clin Chem. 2013;59:617–628. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.187617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perry RJ, Peng L, Barry NA, Cline GW, Zhang D, Cardone RL, Petersen KF, Kibbey RG, Goodman AL, Shulman GI. Acetate mediates a microbiome-brain-β-cell axis to promote metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2016;534:213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature18309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Komaroff AL. The Microbiome and Risk for Obesity and Diabetes. JAMA. 2017;317:355–356. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vrieze A, Van Nood E, Holleman F, Salojärvi J, Kootte RS, Bartelsman JF, Dallinga-Thie GM, Ackermans MT, Serlie MJ, Oozeer R, Derrien M, Druesne A, Van Hylckama Vlieg JE, Bloks VW, Groen AK, Heilig HG, Zoetendal EG, Stroes ES, de Vos WM, Hoekstra JB, Nieuwdorp M. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:913–6.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu HJ, Ivanov II, Darce J, Hattori K, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Littman DR, Benoist C, Mathis D. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2010;32:815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Joosten LA, Koenders MI, Devesa I, Roelofs MF, Radstake TR, Heuvelmans-Jacobs M, Akira S, Nicklin MJ, Ribeiro-Dias F, van den Berg WB. Stimulation of TLR2 and TLR4 differentially skews the balance of T cells in a mouse model of arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:205–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI32639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rehaume LM, Mondot S, Aguirre de Cárcer D, Velasco J, Benham H, Hasnain SZ, Bowman J, Ruutu M, Hansbro PM, McGuckin MA, Morrison M, Thomas R. ZAP-70 genotype disrupts the relationship between microbiota and host, leading to spondyloarthritis and ileitis in SKG mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2780–2792. doi: 10.1002/art.38773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsumoto I, Staub A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Arthritis provoked by linked T and B cell recognition of a glycolytic enzyme. Science. 1999;286:1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Lesker TR, Gronow A, Gilbert B, Raemy E, Lamacchia C, Gabay C, Finckh A, Strowig T. Prevotella copri in individuals at risk for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:590–593. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ni J, Wu GD, Albenberg L, Tomov VT. Gut microbiota and IBD: causation or correlation? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsuoka K, Kanai T. The gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Immunopathol. 2015;37:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00281-014-0454-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13780–13785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Manichanh C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, Gloux K, Pelletier E, Frangeul L, Nalin R, Jarrin C, Chardon P, Marteau P, Roca J, Dore J. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn's disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut. 2006;55:205–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.073817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Willing BP, Dicksved J, Halfvarson J, Andersson AF, Lucio M, Zheng Z, Järnerot G, Tysk C, Jansson JK, Engstrand L. A pyrosequencing study in twins shows that gastrointestinal microbial profiles vary with inflammatory bowel disease phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1844–1854.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nabel GJ. Designing tomorrow's vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:551–560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1204186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Omer SB, Salmon DA, Orenstein WA, deHart MP, Halsey N. Vaccine refusal, mandatory immunization, and the risks of vaccine-preventable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1981–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mascola JR, Fauci AS. Novel vaccine technologies for the 21st century. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:87–88. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710–720. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marchiando AM, Graham WV, Turner JR. Epithelial barriers in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Helander HF, Fändriks L. Surface area of the digestive tract - revisited. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:681–689. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.898326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goto Y, Uematsu S, Kiyono H. Epithelial glycosylation in gut homeostasis and inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1244–1251. doi: 10.1038/ni.3587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang N, Shen N, Vyse TJ, Anand V, Gunnarson I, Sturfelt G, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, Elvin K, Truedsson L, Andersson BA, Dahle C, Ortqvist E, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW, Hammarström L. Selective IgA deficiency in autoimmune diseases. Mol Med. 2011;17:1383–1396. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mirpuri J, Raetz M, Sturge CR, Wilhelm CL, Benson A, Savani RC, Hooper LV, Yarovinsky F. Proteobacteria-specific IgA regulates maturation of the intestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:28–39. doi: 10.4161/gmic.26489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jarchum I, Pamer EG. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by the commensal microbiota. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Palm NW, de Zoete MR, Flavell RA. Immune-microbiota interactions in health and disease. Clin Immunol. 2015;159:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kubinak JL, Petersen C, Stephens WZ, Soto R, Bake E, O'Connell RM, Round JL. MyD88 signaling in T cells directs IgA-mediated control of the microbiota to promote health. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spencer J, Klavinskis LS, Fraser LD. The human intestinal IgA response; burning questions. Front Immunol. 2012;3:108. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lycke NY, Bemark M. The regulation of gut mucosal IgA B-cell responses: recent developments. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:1361–1374. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pabst O, Slack E. IgA and the intestinal microbiota: the importance of being specific. Mucosal Immunol. 2020;13:12–21. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0227-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cerutti A. The regulation of IgA class switching. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:421–434. doi: 10.1038/nri2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fagarasan S, Honjo T. T-Independent immune response: new aspects of B cell biology. Science. 2000;290:89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fagarasan S, Kawamoto S, Kanagawa O, Suzuki K. Adaptive immune regulation in the gut: T cell-dependent and T cell-independent IgA synthesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:243–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Macpherson AJ, Gatto D, Sainsbury E, Harriman GR, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science. 2000;288:2222–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tezuka H, Abe Y, Asano J, Sato T, Liu J, Iwata M, Ohteki T. Prominent role for plasmacytoid dendritic cells in mucosal T cell-independent IgA induction. Immunity. 2011;34:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bunker JJ, Flynn TM, Koval JC, Shaw DG, Meisel M, McDonald BD, Ishizuka IE, Dent AL, Wilson PC, Jabri B, Antonopoulos DA, Bendelac A. Innate and Adaptive Humoral Responses Coat Distinct Commensal Bacteria with Immunoglobulin A. Immunity. 2015;43:541–553. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Macpherson AJ, McCoy KD, Johansen FE, Brandtzaeg P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:11–22. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chorny A, Puga I, Cerutti A. Innate signaling networks in mucosal IgA class switching. Adv Immunol. 2010;107:31–69. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381300-8.00002-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Suzuki K, Kawamoto S, Maruya M, Fagarasan S. GALT: organization and dynamics leading to IgA synthesis. Adv Immunol. 2010;107:153–185. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381300-8.00006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sutherland DB, Fagarasan S. IgA synthesis: a form of functional immune adaptation extending beyond gut. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pabst O. New concepts in the generation and functions of IgA. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:821–832. doi: 10.1038/nri3322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mora JR, Iwata M, Eksteen B, Song SY, Junt T, Senman B, Otipoby KL, Yokota A, Takeuchi H, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Rajewsky K, Adams DH, von Andrian UH. Generation of gut-homing IgA-secreting B cells by intestinal dendritic cells. Science. 2006;314:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1132742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Uematsu S, Fujimoto K, Jang MH, Yang BG, Jung YJ, Nishiyama M, Sato S, Tsujimura T, Yamamoto M, Yokota Y, Kiyono H, Miyasaka M, Ishii KJ, Akira S. Regulation of humoral and cellular gut immunity by lamina propria dendritic cells expressing Toll-like receptor 5. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:769–776. doi: 10.1038/ni.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Uematsu S, Fujimoto K. The innate immune system in the intestine. Microbiol Immunol. 2010;54:645–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fujimoto K, Karuppuchamy T, Takemura N, Shimohigoshi M, Machida T, Haseda Y, Aoshi T, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Uematsu S. A new subset of CD103+CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in the small intestine expresses TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 and induces Th1 response and CTL activity. J Immunol. 2011;186:6287–6295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fujimoto K, Kawaguchi Y, Shimohigoshi M, Gotoh Y, Nakano Y, Usui Y, Hayashi T, Kimura Y, Uematsu M, Yamamoto T, Akeda Y, Rhee JH, Yuki Y, Ishii KJ, Crowe SE, Ernst PB, Kiyono H, Uematsu S. Antigen-Specific Mucosal Immunity Regulates Development of Intestinal Bacteria-Mediated Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:1530–1543.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Woting A, Pfeiffer N, Loh G, Klaus S, Blaut M. Clostridium ramosum promotes high-fat diet-induced obesity in gnotobiotic mouse models. mBio. 2014;5:e01530–e01514. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01530-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moyat M, Velin D. Immune responses to Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5583–5593. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i19.5583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barrios-Villa E, Martínez de la Peña CF, Lozano-Zaraín P, Cevallos MA, Torres C, Torres AG, Rocha-Gracia RDC. Comparative genomics of a subset of Adherent/Invasive Escherichia coli strains isolated from individuals without inflammatory bowel disease. Genomics. 2020;112:1813–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Greathouse KL, Harris CC, Bultman SJ. Dysfunctional families: Clostridium scindens and secondary bile acids inhibit the growth of Clostridium difficile. Cell Metab. 2015;21:9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Manfredo Vieira S, Hiltensperger M, Kumar V, Zegarra-Ruiz D, Dehner C, Khan N, Costa FRC, Tiniakou E, Greiling T, Ruff W, Barbieri A, Kriegel C, Mehta SS, Knight JR, Jain D, Goodman AL, Kriegel MA. Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science. 2018;359:1156–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zaman SB, Hussain MA, Nye R, Mehta V, Mamun KT, Hossain N. A Review on Antibiotic Resistance: Alarm Bells are Ringing. Cureus. 2017;9:e1403. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]