Key Points

Question

Does severe obesity confer a risk of fracture that could be modified with bariatric surgery?

Findings

In this cohort study of 49 113 bariatric surgery–eligible patients covered by Medicare, patients who were eligible for bariatric surgery but did not undergo surgery had an equal risk of fracture compared with patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass but had a greater risk of all site-specific fractures and fractures overall compared with those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy. Among 32 742 patients undergoing bariatric surgery, patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy were found to be at a significantly reduced risk of developing a humeral fracture or fracture in general compared with those undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Meaning

Bariatric surgery may be associated with lower odds of fracture in patients with severe obesity, and sleeve gastrectomy might be the best option for bariatric surgery in patients in which fractures could be a concern.

This cohort study compares the rates of fractures associated with obesity among bariatric surgery–eligible patients who did not undergo surgery, patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and patients who underwent sleeve gastrectomy.

Abstract

Importance

Given the complex relationship between body mass index, body composition, and bone density and the correlative nature of the studies that have established the prevailing notion that higher body mass indices may be protective against osteopenia and osteoporosis and, therefore, fracture, the absolute risk of fracture in patients with severe obesity who undergo either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or sleeve gastrectomy (SG) compared with those who do not undergo bariatric surgery is unknown.

Objective

To assess the rates of fractures associated with obesity and compare rates between those who do not undergo bariatric surgery, those who undergo RYGB, and those who undergo SG.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this retrospective multicenter cohort study of Medicare Standard Analytic Files derived from Medicare parts A and B records from January 2004 to December 2014, patients classified as eligible for bariatric surgery using the US Centers of Medicare & Medicaid criteria who either did not undergo bariatric surgery or underwent RYGB or SG were exactly matched in a 1:1 fashion based on their age, sex, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, hypertension, smoking status, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and obstructive sleep apnea status. Data were analyzed from November to December 2019.

Exposures

RYGB or SG.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome measured in this study was the odds of fracture overall based on exposure to bariatric surgery. Secondary outcomes included the odds of type of fracture (humerus, radius or ulna, pelvis, hip, vertebrae, and total fractures) based on exposure to bariatric surgery.

Results

A total of 49 113 patients were included and were equally made up of 16 371 bariatric surgery–eligible patients who did not undergo weight loss surgery, 16 371 patients who had undergone RYGB, and 16 371 patients who had undergone SG. Each group consisted of an equal number of 4109 men (25.1%) and 12 262 women (74.9%) and had an equal distribution of ages, with 11 780 patients (72.0%) 64 years or younger, 4230 (25.8%) aged 65 to 69 years, 346 (2.1%) aged 70 to 74 years, and 15 (0.1%) aged 75 to 79 years. Patients undergoing RYGB were found to have no significant difference in odds of fractures compared with bariatric surgery–eligible patients who did not undergo surgery. Patients undergoing undergone SG were found to have decreased odds of fractures of the humerus (odds ratio [OR], 0.57; 95% CI, 0.45-0.73), radius or ulna (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.25-0.58), hip (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.33-0.74), pelvis (OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18-0.64), vertebrae (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.48-0.74), or fractures in general (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.46-0.62). Compared with patients undergoing SG, patients undergoing RYGB had a significantly greater risk of total fractures (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.55-2.06) and humeral fractures (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.24-2.07).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, bariatric surgery was associated with a reduced risk of fracture in bariatric surgery–eligible patients. Sleeve gastrectomy might be the best option for weight loss in patients in which fractures could be a concern, as RYGB may be associated with an increased fracture risk compared with SG.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery has increasingly become common as obesity has become a widespread concern in much of the high-income world.1,2,3,4,5 These interventions have been shown to be associated with lasting and substantial weight loss, correction and protection from obesity-related conditions, and substantial benefits in quality of life and longevity.2,3,6,7,8,9,10,11 Among obesity-related conditions, bariatric surgery has been demonstrated to reduce the burden of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, migraines, and obesity-related risk of some cancers.8,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 There is a large body of literature reporting an observational association between higher body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) and higher bone mineral density (BMD) that has implied that high BMI has protective effects on the skeleton and has led to the inference that loss of excessive body weight may result in decreases in BMD.11,19,20,21,22 To this end, bariatric surgery might therefore result in a decreased BMD and serve as a contributor to potentially higher rates and risks of fracture. Furthermore, surgical weight loss approaches that alter the fundamental patterns of alimentary absorption, like Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), may serve to hasten this risk and have been associated with the development of metabolic bone disease, resulting in higher bone turnover and long-term declines, disruptions, and deterioration in bone density and bone microarchitecture.22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30

However, the notion that obesity protects from fracture has been challenged.31 Recent studies have reported heightened rates of fracture among those with greater levels of central obesity and in postmenopausal women with obesity.32,33 Those studies challenge the value of BMD as a surrogate measure to assess bone fragility in individuals with obesity and furthermore raise questions on the general notion that bariatric surgery is detrimental to the skeleton because it lowers BMD while pointing out the need of long-term studies to assess actual bone fragility after metabolic and weight management surgery. Fracture risk after bariatric surgery has been scarcely studied, and data are contradictory, reporting either no increased risk or limited increased risk. Those inconsistencies are likely due to the wide difference in matching parameters for controls, limited follow-up after surgery, a limited number of participants, and differences in surgical procedures.23,24,25,26,27,34 Given the complex relationship between body composition, bone density, and bone fragility as well as the correlative nature of the studies that have established the prevailing notion that higher BMIs may be protective against osteopenia, osteoporosis, and, therefore, fracture, here we explored the absolute risk of fracture in patients with severe obesity who did not undergo bariatric surgery, those who underwent surgical interventions with both restrictive and malabsorptive features (RYGB), and those who underwent surgical interventions with less malabsorptive features (sleeve gastrectomy [SG]).

Methods

Data Source

This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. Longitudinal Medicare Standard Analytic Files containing 100% of inpatient and outpatient facility records billed to Medicare derived from Medicare parts A and B from January 2004 to December 2014 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were defined as eligible for bariatric surgery based on the US Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) criteria for the use of bariatric surgery in adults: BMI of 40 or greater, more than 100 pounds overweight, or BMI of 35 or greater and at least 1 or more obesity-related comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and other respiratory disorders, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), osteoarthritis, lipid abnormalities, gastrointestinal disorders, or heart disease using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes. These criteria, preoperative management, surgical management and procedure, and postoperative management recommendations have remained relatively unchanged throughout the study period and to date.28 Patients with a billed interaction at any time during their available Medicare insurance history pertaining to cancer, transplant, end-stage kidney disease, previous gastric operations, gastric banding procedures, or fractures prior to undergoing bariatric surgery were excluded. Patients within this population who underwent RYGB or SG were identified based on ICD-9 procedure codes and Current Procedural Terminology codes (eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement). Patients within this population who did not undergo bariatric surgery were defined as eligible for bariatric surgery. The study was approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board with a waiver of patient informed consent, as the nature of this analysis posed minimal risk to participating individuals and the data were presented in aggregate to minimize any risks of loss of confidentiality of medical data.

Comorbidities

Demographic data for aggregate records included sex and age. ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes were used to identify comorbidities (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Comorbidities were noted as follows: hypertension, smoking status, NAFLD, hyperlipidemia, T2D, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, postmenopausal status, and OSA. Comorbidities were accessed as a given patient having a billable health care interaction during the CMS bariatric surgery assessment period of 1 year prior to surgery. Age was reported as the age of the patient at the time of surgery. The strategy to use claims-based algorithms to identify patient BMIs has been explored previously and has been demonstrated to be most efficacious in patients who are obese; furthermore, since the institution of Meaningful Use requirements instituted by CMS, BMI reporting has since further improved.29,30

Outcome Definition

The primary outcome measured in this study was the odds of fracture overall based on exposure to bariatric surgery over a 3-year period. Secondary outcomes included the odds of site-specific fractures (humerus, radius or ulna, pelvis, hip, vertebrae, and total fractures) based on exposure to bariatric surgery. Fractures were defined using ICD-9 codes to identify humeral, radial and ulnar, pelvic, hip, and vertebral fractures (eTable 2 in the Supplement). This strategy to use claims-based algorithms to identify fractures has been demonstrated to have a high positive predictive value for these kinds of fractures and have been previously used in this manner to study fracture risk.32,33,35

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for age, sex, comorbidities, and postoperative complications to compare the characteristics of bariatric surgery–eligible patients not undergoing bariatric surgery, those who underwent RYGB, and those who underwent SG. Patient populations were exactly matched in a 1:1 fashion based on age, sex, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, hypertension, smoking status, NAFLD, hyperlipidemia, T2D, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and OSA. χ2 Tests were then calculated to compare categorical variables, including age ranges, sex, and comorbidity status (hypertension, smoking status, NAFLD, hyperlipidemia, T2D, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and OSA). Analysis of variance was used for quantitative variables (Elixhauser Comorbidity Index). Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to compare fracture events based on bariatric surgery eligibility and whether the patient underwent RYGB or SG. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of fractures following either RYGB or SG were plotted within 3 years following surgery. Log-rank testing was performed to compare fracture risk between patients undergoing RYGB and SG. Significance levels were adjusted using Bonferroni corrections, and significance was set at a 2-tailed P value less than .008. Data were analyzed using R statistical software version 3.42 (The R Foundation).

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

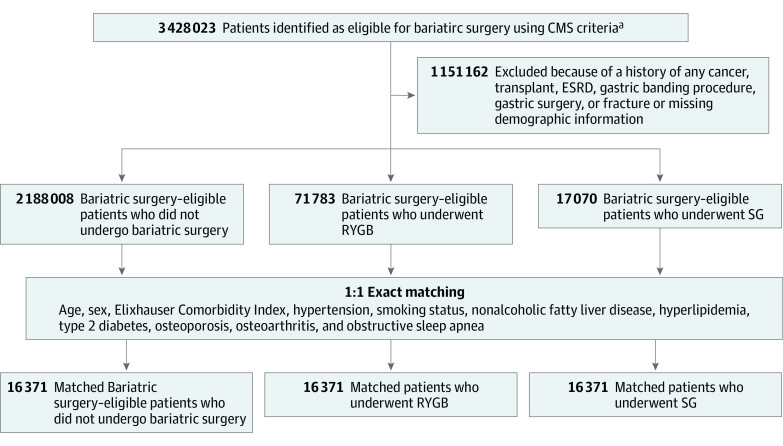

A total of 3 428 023 patients were identified as eligible for bariatric surgery based on the criteria outlined by CMS between January 2004 and December 2014. Following exclusion of patients with missing demographic information or a history of cancer, transplant, end-stage kidney disease, gastric operations, or gastric banding procedures, 2 188 008 patients were identified as eligible for bariatric surgery but did not undergo either RYGB or SG, while 71 783 bariatric surgery–eligible patients were found to have undergone RYGB and 17 070 were found to have undergone SG as a weight loss intervention (Figure 1). The descriptive characteristics of the total population are summarized in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Patient Selection Procedure.

CMS indicates US Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

aEligibility for bariatric surgery was defined as a body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) of 40 or greater, more than 100 pounds overweight, or body mass index of 35 or greater and at least 1 or more obesity-related comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea and other respiratory disorders, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, osteoarthritis, lipid abnormalities, gastrointestinal disorders, or heart disease.

The matched population analyzed in this study contained 49 113 patients, which were equally represented by 16 371 bariatric surgery–eligible patients who did not undergo weight loss surgery, 16 371 patients who underwent RYGB, and 16 371 patients who underwent SG. The demographic distribution and comorbidity status of these patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Characteristics of Bariatric Surgery–Eligible Patients and Patients Who Underwent RYGB or SG.

| Parameters | No. (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 49 113) | Bariatric surgery–eligible patients (N = 16 371) | RYGB (n = 16 371) | SG (n = 16 371) | ||

| Age, y | |||||

| ≤64 | 35 340 (72.0) | 11 780 (72.0) | 11 780 (72.0) | 11 780 (72.0) | >.99 |

| 65-69 | 12 690 (25.8) | 4230 (25.8) | 4230 (25.8) | 4230 (25.8) | |

| 70-74 | 1038 (2.1) | 346 (2.1) | 346 (2.1) | 346 (2.1) | |

| 75-79 | 45 (0.1) | 15 (0.1) | 15 (0.1) | 15 (0.1) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 12 327 (25.1) | 4109 (25.1) | 4109 (25.1) | 4109 (25.1) | >.99 |

| Female | 36 786 (74.9) | 12 262 (74.9) | 12 262 (74.9) | 12 262 (74.9) | |

| Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 6.2 (2.9) | 6.2 (2.9) | 6.2 (2.9) | 6.2 (2.9) | >.99 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 35 241 (71.8) | 11 747 (71.8) | 11 747 (71.8) | 11 747 (71.8) | >.99 |

| Smoking | 15 123 (30.8) | 5041 (30.8) | 5041 (30.8) | 5041 (30.8) | >.99 |

| NAFLD | 336 (0.7) | 112 (0.7) | 112 (0.7) | 112 (0.7) | >.99 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 27 918 (56.8) | 9306 (56.8) | 9306 (56.8) | 9306 (56.8) | >.99 |

| Osteoporosis | 1869 (3.8) | 623 (3.8) | 623 (3.8) | 623 (3.8) | >.99 |

| Osteoarthritis | 12 870 (26.2) | 4290 (26.2) | 4290 (26.2) | 4290 (26.2) | >.99 |

| OSA | 22 200 (45.2) | 7400 (45.2) | 7400 (45.2) | 7400 (45.2) | >.99 |

| T2D | 23 361 (47.6) | 7787 (47.6) | 7787 (47.6) | 7787 (47.6) | >.99 |

Abbreviations: NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Each group consisted of 4109 men (25.1%) and 12 262 women (74.9%) and had an equal distribution of ages, with 11 780 patients (72.0%) aged 64 years or younger, 4230 (25.8%) aged 65 to 69 years, 346 (2.1%) aged 70 to 74 years, and 15 (0.1%) aged 75 to 79 years. Bariatric surgery–eligible patients, patients who underwent RYGB, and patients who underwent SG had mean (SD) Elixhauser Comorbidity Indices of 6.2 (2.9; P > .99). Rates of hypertension (71.8%), smoking status (30.8%), hyperlipidemia (56.8%), OSA (45.2%), T2D (47.6%), NAFLD (0.7%), osteoporosis (3.8%), and osteoarthritis (26.2%) were exactly matched and so were the same among bariatric surgery–eligible patients and patients undergoing either RYGB or SG (Table 1).

Rates and Risk of Fracture

Bariatric Surgery–Eligible Patients vs Patients Undergoing RYGB or SG

A total of 1382 patients (2.8%) in the matched population were found to experience a fracture. Of the fractures experienced overall, the greatest number were vertebral fractures (522 [1.1%]). Patients with obesity eligible for bariatric surgery (562 [3.4%]) and patients undergoing RYGB (523 [3.2%]) were found to have similar rates of fractures, whereas patients undergoing SG (297 [1.8%]) experienced significantly lower rates of fracture overall at 3 years following surgery (P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Rates of Fracture in Patients Who Underwent Bariatric Surgery vs Bariatric Surgery–Eligible Patients Who Did Not at 3 Years Following Surgery.

| Fracture | No. (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 49 113) | Bariatric surgery–eligible patients (n = 16 371) | RYGB (n = 16 371) | SG (n = 16 371) | ||

| Humerus | 422 (0.9) | 170 (1.0) | 155 (0.9) | 97 (0.6) | <.001a |

| Radius or ulna | 176 (0.4) | 77 (0.5) | 70 (0.4) | 29 (0.2) | <.001a |

| Pelvic | 86 (0.2) | 38 (0.2) | 35 (0.2) | 13 (0.1) | <.001a |

| Hip | 176 (0.4) | 69 (0.4) | 73 (0.4) | 34 (0.2) | <.001a |

| Vertebral | 522 (1.1) | 208 (1.3) | 190 (1.2) | 124 (0.8) | <.001a |

| Total | 1382 (2.8) | 562 (3.4) | 523 (3.2) | 297 (1.8) | <.001a |

Abbreviations: RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

Significance was set at a Bonferroni-corrected P value less than .008.

There were no significant differences between bariatric surgery–eligible patients and those who underwent RYGB in the odds of experiencing a fracture overall (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.84-1.07), humeral fracture (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.73-1.13), radial or ulnar fracture (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.66-1.26), pelvic fracture (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.58-1.46), hip fracture (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.76-1.47), or vertebral fracture (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.75-1.11) (Table 3). Compared with bariatric surgery–eligible patients who did not undergo surgery, those who underwent SG had lower odds of fractures of the humerus (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.45-0.73), radius or ulna (OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.25-0.58), hip (OR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.33-0.74), pelvis (OR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.18-0.64),vertebrae (OR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.48-0.74), or in general (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.46-0.62) (Table 3).

Table 3. Odds of Fracture in Patients Who Underwent RYGB or SG vs Bariatric Surgery–Eligible Patients Who Did Not at 3 Years Following Surgery.

| Fracture | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| RYGB vs bariatric surgery–eligible patients | SG vs bariatric surgery–eligible patients | |

| Humerus | 0.91 (0.73-1.13) | 0.57 (0.45-0.73)a |

| Radius or ulna | 0.90 (0.66-1.26) | 0.38 (0.25-0.58)a |

| Pelvic | 0.92 (0.58-1.46) | 0.34 (0.18-0.64)a |

| Hip | 1.06 (0.76-1.47) | 0.49 (0.33-0.74)a |

| Vertebral | 0.91 (0.75-1.11) | 0.60 (0.48-0.74)a |

| Total | 0.95 (0.84-1.07) | 0.53 (0.46-0.62)a |

Abbreviations: RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SG, sleeve gastrectomy.

P < .008.

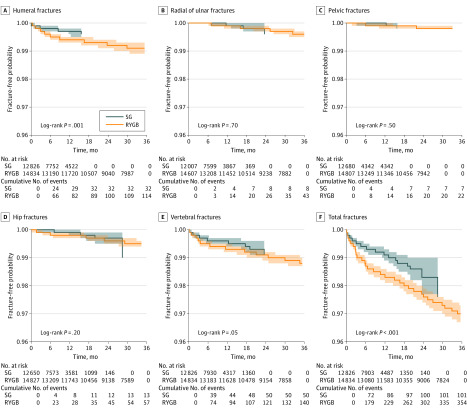

RYGB vs SG

When comparing the rates of developing fractures within 3 years following surgery, patients undergoing RYGB had a significantly greater risk of total fractures and fractures of the humerus compared with those undergoing SG (total: OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.55-2.06; humerus: OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.24-2.07). There were no significant differences in the risk associated with developing fractures of the radius or ulna, pelvis, hip, or vertebrae between patients who underwent RYGB and those who underwent SG (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Site-Specific and Total Fracture Risk at 3 Years Following Bariatric Surgery in Patients Undergoing Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) vs Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG).

Discussion

In this matched cohort analysis of 49 113 bariatric surgery–eligible patients, including 16 371 who did not undergo bariatric surgery, 16 371 who underwent RYGB, and 16 371 who underwent SG, it was found that patients who were eligible for bariatric surgery but did not undergo surgery had a similar odds of fracture as patients undergoing RYGB at 3 years following surgery. Furthermore, patients who underwent SG had significantly lower odds of all site-specific fractures and fractures overall compared with bariatric surgery–eligible patients. Among patients undergoing bariatric surgery, patients who underwent SG were found to be at a significantly reduced risk of developing a humeral fracture or fracture in general.

The present study provides valuable clinical information to the field of bariatrics by providing, for the first time to our knowledge, specific analysis of the risk of fracture among patients who undergo bariatric surgery compared with patients who are eligible for bariatric surgery but do not. Furthermore, this study establishes a timeline for this deferential risk in patients who undergo RYGB compared with patients who undergo SG. In addition, this study demonstrates challenging information to the long-supported idea in medicine that patients with higher BMI (and so patients who are obese) experience a protective benefit against osteoporosis and fractures by illustrating a potential protection against fracture in patients who undergo bariatric surgery. Furthermore, SG was found to be more protective against fracture compared with RYGB.

Fracture Risk in Bariatric Surgery and Obesity

Increasing BMI and obesity have been long associated with higher BMD and lower incidences of fracture.7,22,28,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43 Very recently, the Look AHEAD trial,37,38,39 a multicenter randomized clinical trial that was designed to determine whether intentional weight loss reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in overweight individuals with T2D, suggested that even relatively small percentages of weight loss (6% to 9%) are associated with significant reductions in BMD and with increased risk of hip, pelvis, and upper arm fracture. Given that most studies that report total body weight loss following RYGB and SG have reported a mean percentage of total weight loss of more than 25% and 18%, respectively, at 5 years, the notion that this kind of major weight loss itself results in an increase in the fracture risk profile of patients would reasonably follow.7,17,44,45,46,47,48 Emerging data have started to challenge the notion that obesity is protective against all fractures and has supported that patterns of fat deposition (body fat sites and ratios of visceral fat to subcutaneous fat) and body compositions (muscle mass) may have a greater influence on BMD and fracture risk profiles than BMI alone.49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57

The present study assessed the risk of fractures of the humerus, radius or ulna, pelvis, hip, and vertebrae in patients undergoing bariatric surgery and those who were eligible to undergo bariatric surgery but did not and found that obesity conferred a significantly greater risk of all fracture types and fractures overall compared with patients undergoing SG and similar risks for all fracture types and fractures overall compared with patients undergoing RYGB, providing evidence for a potential protective effect of weight loss against the risk of fractures. In the case of RYGB, a malabsorptive mechanism and complex bone metabolism changes may serve to further complicate this relationship. This does not mean that BMD does not change in these patients; in fact, several studies have described long-term changes in BMD following weight loss surgery as measured by BMD scans and markers of bone turnover, but this further underscores a more multifaceted and multifactorial risk profile for fractures in patients with severe obesity.58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70

Risk of Fracture in RYGB vs SG

Surgical weight loss approaches that alter the fundamental patterns of alimentary absorption, like RYGB, have been shown to hasten this risk and have even been associated with the development of metabolic bone disease, resulting in higher bone turnover and long-term declines, disruptions, and deterioration in bone density and bone microarchitecture. However, it is important to note that many of the clinical studies that have studied postoperative fracture risk and BMD changes following RYGB have a number of limitations; very few studies provide nonsurgical controls or detail age-related changes or measurement drifts, several studies lack preoperative measurements of BMD or provide baseline measures of bone turnover, and only a limited number of studies quantify rates of BMD loss or risk of fracture between different bariatric procedures.59,60,71,72,73 Despite these shortcomings in clinical studies and challenges in bone density imaging, most evidence in the literature to date suggests that surgical weight loss procedures may have long-term and persistent negative effects that might differ by surgical approach. Specifically, higher levels and rates of BMD loss and fracture risk in patients undergoing RYGB have been postulated to be caused in part by the malabsorptive implications and associated changes in alimentary-associated hormones ghrelin, glucagon-like peptide 1, and peptide YY, changes in estradiol, leptin, visfatin, resistin, and adiponectin, and changes in bile acid metabolism.74,75,76,77

Unfortunately, there is a paucity of evidence or information regarding both the independent risks of fracture imparted by SG or comparing bone loss with fracture risk in patients undergoing RYGB, with the very few studies available either providing conflicting information with regards to BMD loss or being underpowered.72,78,79,80 These limited clinical data, when interpreted in the context of the limited animal studies comparing bone loss seen following RYGB vs SG, seem to show that the rate of bone loss following SG is less than that observed in RYGB.81 The present study, to our knowledge, demonstrates for the first time a comparative increase in fracture risk, albeit demonstrated to be lower than their bariatric equivalents, in patients undergoing RYGB vs SG. Specifically, this increased risk was found to be significant in fractures overall and humerus fractures but was not significant when comparing the risk of fractures of the radius or ulna, pelvis, hip, or vertebrae. To this end, it appears that the risk of fracture in patients following SG is less than that observed with RYGB, although additional investigation is required to better elucidate this risk and, further, the expressed relationship between BMD loss and fracture following RYGB and SG.

Limitations

Administrative data allow access to more medical visits nationwide and longitudinal tracking of these patients through distinct identifiers based on a standardized coding system; however, important limitations in the use of these data must be considered. First, administrative data are intended for financial and administrative use rather than research purposes and therefore may vary in detail and accuracy. Second, administrative data also do not provide qualifiable details on the severity of disease states or patient-reported outcome scores or allow for standardization of treatment protocols or surgeon technique or expertise, which may mask certain confounding factors. Third, specifically for the purposes of this article, administrative data limit the assessment of the specific weight loss a patient may experience as a result of bariatric surgery and so we are unable to directly assess any potential associations between absolute weight loss and fracture risk.

Conclusions

The generally accepted notion that obesity is protective when considering the risks of fracture may not be as straightforward as previously thought. The relationship between BMI, body composition, and bone density may play an important role when evaluating the risk of fracture in patients with obesity. Severe obesity status alone might be associated with an increased risk of fracture, and there is a role for weight loss surgery in augmenting this risk. Specifically, SG might be the best option for weight loss in patients in whom fractures could be a concern, as RYGB may be associated with an increased fracture risk compared with SG. Additional studies are needed to not only further characterize the risk profile of obesity on rates of fracture but also to access fracture risk and benefits of different surgical weight loss options.

eTable 1. Coding Definitions

eTable 2. Coding Definitions For Fracture Categories

eTable 3. Descriptive Characteristics of Bariatric Surgery–Eligible Patients and Patients Who Underwent Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass or Sleeve Gastrectomy

References

- 1.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. . Bariatric surgery and endoluminal procedures: IFSO worldwide survey 2014. Obes Surg. 2017;27(9):2279-2289. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2666-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284-2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang S-H, Stoll CRT, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(3):275-287. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations World Statistics Pocketbook: 2018 edition. Accessed January 5, 2020. https://www.un-ilibrary.org/economic-and-social-development/world-statistics-pocketbook-2018_401071ce-en

- 5.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Formisano G, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822-1832. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1657-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruschi Kelles SM, Machado CJ, Barreto SM. Before-and-after study: does bariatric surgery reduce healthcare utilization and related costs among operated patients? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2015;31(6):407-413. doi: 10.1017/S0266462315000653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petty N. Impact of commissioning weight-loss surgery for bariatric patients. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(15):776-780. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.15.776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livingston EH. Is bariatric surgery worth it? comment on “Impact of bariatric surgery on health care costs of obese persons.” JAMA Surg. 2013;148(6):562. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith VA, Arterburn DE, Berkowitz TSZ, et al. . Association between bariatric surgery and long-term health care expenditures among veterans with severe obesity. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(12):e193732. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arterburn DE, Courcoulas AP. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic conditions in adults. BMJ. 2014;349(9):g3961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGee DL; Diverse Populations Collaboration . Body mass index and mortality: a meta-analysis based on person-level data from twenty-six observational studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(2):87-97. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hachem A, Brennan L. Quality of life outcomes of bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2016;26(2):395-409. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1940-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bond DS, Vithiananthan S, Nash JM, Thomas JG, Wing RR. Improvement of migraine headaches in severely obese patients after bariatric surgery. Neurology. 2011;76(13):1135-1138. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318212ab1e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perathoner A, Zitt M, Lanthaler M, Pratschke J, Biebl M, Mittermair R. Long-term follow-up evaluation of revisional gastric bypass after failed adjustable gastric banding. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(11):4305-4312. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3047-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricci C, Gaeta M, Rausa E, Macchitella Y, Bonavina L. Early impact of bariatric surgery on type II diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression on 6,587 patients. Obes Surg. 2014;24(4):522-528. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1121-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, et al. . Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307(1):56-65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thereaux J, Lesuffleur T, Czernichow S, et al. . Association between bariatric surgery and rates of continuation, discontinuation, or initiation of antidiabetes treatment 6 years later. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(6):526-533. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.6163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arterburn DE, Olsen MK, Smith VA, et al. . Association between bariatric surgery and long-term survival. JAMA. 2015;313(1):62-70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schafer AL. Intestinal calcium absorption and skeletal health after bariatric surgery In: Weaver CM, Daly RM, Bischoff-Ferrari H, eds. Nutritional Influences on Bone Health: 9th International Symposium. Springer; 2016:271-278. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardlaw GM. Putting body weight and osteoporosis into perspective. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63(3)(suppl):433S-436S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.3.433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radak TL. Caloric restriction and calcium’s effect on bone metabolism and body composition in overweight and obese premenopausal women. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(12):468-481. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guney E, Kisakol G, Ozgen G, Yilmaz C, Yilmaz R, Kabalak T. Effect of weight loss on bone metabolism: comparison of vertical banded gastroplasty and medical intervention. Obes Surg. 2003;13(3):383-388. doi: 10.1381/096089203765887705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Axelsson KF, Werling M, Eliasson B, et al. . Fracture risk after gastric bypass surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(12):2122-2131. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. ; STAMPEDE Investigators . Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641-651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rousseau C, Jean S, Gamache P, et al. . Change in fracture risk and fracture pattern after bariatric surgery: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2016;354:i3794. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura KM, Haglind EGC, Clowes JA, et al. . Fracture risk following bariatric surgery: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25(1):151-158. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2463-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu EW, Lee MP, Landon JE, Lindeman KG, Kim SC. Fracture risk after bariatric surgery: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus adjustable gastric banding. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(6):1229-1236. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ablett AD, Boyle BR, Avenell A. Fractures in adults after weight loss from bariatric surgery and weight management programs for obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29(4):1327-1342. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-03685-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pendergrass SA, Crawford DC. Using electronic health records to generate phenotypes for research. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2019;100(1):e80. doi: 10.1002/cphg.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rea S, Bailey KR, Pathak J, Haug PJ. Bias in recording of body mass index data in the electronic health record. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2013;2013:214-218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Compston JE, Watts NB, Chapurlat R, et al. ; Glow Investigators . Obesity is not protective against fracture in postmenopausal women: GLOW. Am J Med. 2011;124(11):1043-1050. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hudson M, Avina-Zubieta A, Lacaille D, Bernatsky S, Lix L, Jean S. The validity of administrative data to identify hip fractures is high—a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(3):278-285. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML. Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(7):703-714. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90047-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, et al. . Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345(1):e5085. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu EW, Kim SC, Sturgeon DJ, Lindeman KG, Weissman JS. Fracture risk after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs adjustable gastric banding among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(8):746-753. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crandall CJ, Yildiz VO, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. . Postmenopausal weight change and incidence of fracture: post hoc findings from Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study and Clinical Trials. BMJ. 2015;350(6):h25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson KC, Bray GA, Cheskin LJ, et al. ; Look AHEAD Study Group . The effect of intentional weight loss on fracture risk in persons with diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD randomized clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(11):2278-2287. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipkin EW, Schwartz AV, Anderson AM, et al. ; Look AHEAD Research Group . The Look AHEAD trial: bone loss at 4-year follow-up in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(10):2822-2829. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz AV, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, et al. ; Look AHEAD Research Group . Effect of 1 year of an intentional weight loss intervention on bone mineral density in type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD randomized trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(3):619-627. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang BC, Villareal DT. Weight loss-induced reduction of bone mineral density in older adults with obesity. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2019;38(1):100-114. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2018.1564721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galvard H, Elmståhl S, Elmståhl B, Samuelsson S-M, Robertsson E. Differences in body composition between female geriatric hip fracture patients and healthy controls: body fat is more important as explanatory factor for the fracture than body weight and lean body mass. Aging (Milano). 1996;8(4):282-286. doi: 10.1007/BF03339580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. ; Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group . Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(12):767-773. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honkanen RJ, Honkanen K, Kröger H, Alhava E, Tuppurainen M, Saarikoski S. Risk factors for perimenopausal distal forearm fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(3):265-270. doi: 10.1007/s001980050291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arterburn D, Wellman R, Emiliano A, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Study Collaborative . Comparative effectiveness and safety of bariatric procedures for weight loss: a PCORnet cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(11):741-750. doi: 10.7326/M17-2786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. . Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(11):1046-1055. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young MT, Jafari MD, Gebhart A, Phelan MJ, Nguyen NT. A decade analysis of trends and outcomes of bariatric surgery in Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(3):480-488. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flum DR, Salem L, Elrod JAB, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L. Early mortality among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1903-1908. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharma P, McCarty TR, Yadav S, Ngu JN, Njei B. Impact of bariatric surgery on outcomes of patients with sickle cell disease: a Nationwide Inpatient Sample analysis, 2004-2014. Obes Surg. 2019;29(6):1789-1796. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-03780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer HE, Willett WC, Flint AJ, Feskanich D. Abdominal obesity and hip fracture: results from the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(6):2127-2136. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen A, Dempster DW, Recker RR, et al. . Abdominal fat is associated with lower bone formation and inferior bone quality in healthy premenopausal women: a transiliac bone biopsy study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):2562-2572. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sundh D, Rudäng R, Zoulakis M, Nilsson AG, Darelid A, Lorentzon M. A high amount of local adipose tissue is associated with high cortical porosity and low bone material strength in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(4):749-757. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russell M, Mendes N, Miller KK, et al. . Visceral fat is a negative predictor of bone density measures in obese adolescent girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1247-1255. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bredella MA, Torriani M, Ghomi RH, et al. . Determinants of bone mineral density in obese premenopausal women. Bone. 2011;48(4):748-754. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hind K, Pearce M, Birrell F. Total and visceral adiposity are associated with prevalent vertebral fracture in women but not men at age 62 years: the Newcastle Thousand Families study. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(5):1109-1115. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilsanz V, Chalfant J, Mo AO, Lee DC, Dorey FJ, Mittelman SD. Reciprocal relations of subcutaneous and visceral fat to bone structure and strength. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3387-3393. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paik JM, Rosen HN, Katz JN, et al. . BMI, waist circumference, and risk of incident vertebral fracture in women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(9):1513-1519. doi: 10.1002/oby.22555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao L-J, Liu Y-J, Liu P-Y, Hamilton J, Recker RR, Deng H-W. Relationship of obesity with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(5):1640-1646. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carlin AM, Rao DS, Yager KM, Parikh NJ, Kapke A. Treatment of vitamin D depletion after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized prospective clinical trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(4):444-449. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.von Mach M-A, Stoeckli R, Bilz S, Kraenzlin M, Langer I, Keller U. Changes in bone mineral content after surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Metabolism. 2004;53(7):918-921. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu EW, Bouxsein ML, Roy AE, et al. . Bone loss after bariatric surgery: discordant results between DXA and QCT bone density. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(3):542-550. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goode LR, Brolin RE, Chowdhury HA, Shapses SA. Bone and gastric bypass surgery: effects of dietary calcium and vitamin D. Obes Res. 2004;12(1):40-47. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pereira FA, de Castro JAS, dos Santos JE, Foss MC, Paula FJA. Impact of marked weight loss induced by bariatric surgery on bone mineral density and remodeling. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40(4):509-517. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2007000400009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein EM, Carrelli A, Young P, et al. . Bariatric surgery results in cortical bone loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(2):541-549. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Casagrande DS, Repetto G, Mottin CC, et al. . Changes in bone mineral density in women following 1-year gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22(8):1287-1292. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0687-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sinha N, Shieh A, Stein EM, et al. . Increased PTH and 1.25(OH)(2)D levels associated with increased markers of bone turnover following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19(12):2388-2393. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biagioni MFG, Mendes AL, Nogueira CR, Paiva SAR, Leite CV, Mazeto GMFS. Weight-reducing gastroplasty with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: impact on vitamin D status and bone remodeling markers. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2014;12(1):11-15. doi: 10.1089/met.2013.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DiGiorgi M, Daud A, Inabnet WB, et al. . Markers of bone and calcium metabolism following gastric bypass and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2008;18(9):1144-1148. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9408-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Kadre LJ, Rocha PRS, de Almeida Tinoco AC, Tinoco RC. Calcium metabolism in pre- and postmenopausal morbidly obese women at baseline and after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14(8):1062-1066. doi: 10.1381/0960892041975505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mahdy T, Atia S, Farid M, Adulatif A. Effect of Roux-en Y gastric bypass on bone metabolism in patients with morbid obesity: Mansoura experiences. Obes Surg. 2008;18(12):1526-1531. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9653-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riedl M, Vila G, Maier C, et al. . Plasma osteopontin increases after bariatric surgery and correlates with markers of bone turnover but not with insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(6):2307-2312. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olbers T, Björkman S, Lindroos A, et al. . Body composition, dietary intake, and energy expenditure after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic vertical banded gastroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2006;244(5):715-722. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000218085.25902.f8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nogués X, Goday A, Peña MJ, et al. . Bone mass loss after sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective comparative study with gastric bypass. Cirugía Española Engl Ed. 2010;88(2):103-109. Article in Spanish. doi: 10.1016/s2173-5077(10)70015-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dixon JB, Strauss BJG, Laurie C, O’Brien PE. Changes in body composition with weight loss: obese subjects randomized to surgical and medical programs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15(5):1187-1198. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Quercia I, Dutia R, Kotler DP, Belsley S, Laferrère B. Gastrointestinal changes after bariatric surgery. Diabetes Metab. 2014;40(2):87-94. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haider DG, Schindler K, Schaller G, Prager G, Wolzt M, Ludvik B. Increased plasma visfatin concentrations in morbidly obese subjects are reduced after gastric banding. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(4):1578-1581. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ballantyne GH, Gumbs A, Modlin IM. Changes in insulin resistance following bariatric surgery and the adipoinsular axis: role of the adipocytokines, leptin, adiponectin and resistin. Obes Surg. 2005;15(5):692-699. doi: 10.1381/0960892053923789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wucher H, Ciangura C, Poitou C, Czernichow S. Effects of weight loss on bone status after bariatric surgery: association between adipokines and bone markers. Obes Surg. 2008;18(1):58-65. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9258-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pluskiewicz W, Bužga M, Holéczy P, Bortlík L, Šmajstrla V, Adamczyk P. Bone mineral changes in spine and proximal femur in individual obese women after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a short-term study. Obes Surg. 2012;22(7):1068-1076. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0654-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ruiz-Tovar J, Oller I, Priego P, et al. . Short- and mid-term changes in bone mineral density after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2013;23(7):861-866. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0866-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vilarrasa N, de Gordejuela AGR, Gómez-Vaquero C, et al. . Effect of bariatric surgery on bone mineral density: comparison of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2013;23(12):2086-2091. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1016-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stemmer K, Bielohuby M, Grayson BE, et al. . Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery but not vertical sleeve gastrectomy decreases bone mass in male rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154(6):2015-2024. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Coding Definitions

eTable 2. Coding Definitions For Fracture Categories

eTable 3. Descriptive Characteristics of Bariatric Surgery–Eligible Patients and Patients Who Underwent Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass or Sleeve Gastrectomy