Abstract

Humans exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) have variable susceptibility to tuberculosis (TB) and its outcomes. Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 are members of the sialic-acid binding lectin family that regulate immune responses to pathogens through inhibitory (Siglec-5) and activating (Siglec-14) domains. The SIGLEC14 coding sequence is deleted in a high proportion of individuals, placing a SIGLEC5-like gene under the expression of the SIGLEC14 promoter (the SIGLEC14 null allele) and causing expression of a Siglec-5 like protein in monocytes and macrophages. We hypothesized that the SIGLEC14 null allele was associated with Mtb replication in monocytes, T-cell responses to the BCG vaccine, and clinical susceptibility to TB. The SIGLEC14 null allele was associated with protection from TB meningitis in Vietnamese adults but not with pediatric TB in South Africa. The null allele was associated with increased IL-2 and IL-17 production following ex-vivo BCG stimulation of blood from 10 week-old South African infants vaccinated with BCG at birth. Mtb replication was increased in THP-1 cells overexpressing either Siglec-5 or Siglec-14 relative to controls. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between SIGLEC expression and clinical TB, Mtb replication, or BCG-specific T-cell cytokines.

Keywords: SIGLEC, Tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis

1. Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is a leading infectious cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2014 there were an estimated 9.4 million incident cases of tuberculosis (TB) disease and 1.5 million deaths [1]. There are substantial differences in individual susceptibility to tuberculosis [2–4]. Evidence from twins, Mendelian studies in children, genome wide linkage studies, candidate gene association studies, and genome-wide association studies suggest that human genetic factors mediate susceptibility to TB disease [5–10]. The human innate immune system is critical in the early response to Mtb and the effector mechanisms that kill the bacillus [2, 5, 11]. Macrophages are a major reservoir of Mtb and the success of the bacterium depends in part on its ability to circumvent macrophage killing mechanisms [12, 13]. The host genetic factors that influence the macrophage response to Mtb are not well understood.

Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs) are a family of cell-surface transmembrane receptors that contain an amino-terminal sialic acid-binding site and are expressed on many immune cells including macrophages [14, 15]. All host cells express sialic acids on their surface and recognition of these “Self Associated Molecular Patterns” by Siglecs allows host immune cells to distinguish between self and non-self [16–18]. Consistent with their role in the inhibition of an inappropriate autoimmune inflammatory response, most Siglecs have cytoplasmic domains that contain immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) and induce immunosuppressive signaling events through interaction with tyrosine phosphatases such as SHP1 and SHP2. A smaller number of Siglecs associate with an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) via DAP12 and induce an activation signal through interaction with spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) [17, 19]. Some pathogenic organisms are able to bind host Siglecs. Siglecs mediate capture of HIV by dendritic cells [20] and entry of varicella zoster virus into oligodendroglial cells [21] while certain bacteria are able to induce Siglec signaling in a sialic acid-dependent [22–24] or sialic acid-independent manner [25]. The cell envelope of Mtb contains a variety of glycoconjugates [26], though it is not known whether Mtb is able to bind to Siglec molecules or induce Siglec signaling.

SIGLEC5 and SIGLEC14 encode two human Siglec molecules that are expressed on host innate immune cells including granulocytes and macrophages; Siglec-5 is also expressed on B-cells at lower levels [27]. The two genes share more than 99% sequence homology in the exons encoding their ligand-binding domains [28] but have opposing intracellular signaling effects due to the presence of an ITIM in the cytoplasmic domain of Siglec-5 and an ITAM in the cytoplasmic domain of the Siglec-14/DAP12 complex [27, 29]. The two molecules have been postulated to represent a paired receptor system, in which the inhibitory effect of Siglec-5 is counterbalanced by the activating effect of Siglec-14 [28–30]. Some individuals lack expression of Siglec-14 due to a SIGLEC14 deletion polymorphism between the two genes on chromosome 19. The deletion, termed the SIGLEC14 null allele, eliminates Siglec-14 protein expression but simultaneously places a SIGLEC5-like gene fusion product under the control of the SIGLEC14 promoter [27–29]. Macrophages of null allele homozygotes express only the inhibitory Siglec-5-like molecule while macrophages of wild-type homozygotes express only the activating Siglec-14. Macrophages of heterozygotes express both Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 [27, 31].

Given the central role of macrophages in controlling Mtb infection and the impact of the SIGLEC14 genotype on myeloid cell function, we hypothesized that the SIGLEC14 null allele influences TB susceptibility in humans. We examined a South African pediatric cohort with TB disease and two Vietnamese adult cohorts, one with pulmonary TB (PTB) and the other with TB meningitis (TBM). We also evaluated SIGLEC14-dependent ex-vivo T-cell cytokine responses to Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccination to determine if the molecule plays a role in the development of the adaptive immune response. Lastly, we compared Mtb replication in a monocyte cell line overexpressing either the inhibitory Siglec-5 or the activating Siglec-14. We hypothesized that the SIGLEC14 null allele is associated with Mtb replication in monocytes, T-cell responses to BCG, and clinical susceptibility to TB in children and adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human subjects recruitment

Vietnamese adult cohort

HIV-uninfected adults (age > 15 years) with PTB were recruited in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, from a network of district tuberculosis clinics or from the Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital for Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases. Subjects had positive sputum smears for acid-fast bacilli and also met the following criteria: no history of previous tuberculosis treatment, no evidence of extrapulmonary or miliary tuberculosis, and negative HIV testing.

HIV-negative adults with TBM were recruited from 1997 through 2008 from two hospitals in Ho Chi Minh City: the Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital for Tuberculosis and the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. Subjects were diagnosed with TBM using the following two sets of criteria: “Definite TBM” was defined as clinical meningitis (nuchal rigidity, abnormal CSF parameters) and positive Ziehl-Neelsen stain or positive Mtb culture from the cerebrospinal fluid. “Probable TBM” was defined as clinical meningitis plus one or more of the following: chest radiograph consistent with active tuberculosis, acid-fast bacilli found in any specimen other than CSF, or clinical evidence of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Severity of TBM was assessed at presentation using the British Medical Research Council TBM grade, the Glasgow Coma Scale, and the presence of a focal neurologic deficit (defined as the presence of cranial nerve palsy, monoplegia, hemiplegia, paraplegia, or quadriplegia) [32]. A subset of patients with TBM had cytokine and chemokine levels measured from the CSF as previously described [33]. All patients with TBM were followed up until the end of anti-tuberculosis treatment.

Controls consisted of umbilical cord blood from newborns at Hung Vuong Hospital, Ho Chi Minh City. All subjects were unrelated and >99% were of the Vietnamese Kinh ethnicity. Written, informed consent was obtained from patients or their relatives for the cord blood samples and if the patient was unable to provide consent. All protocols were approved by human subject review committees at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Pham Ngoc Thach Hospital, Health Services of Ho Chi Minh City, Hung Vuong Hospital, Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee, and the University of Washington. Subjects from this cohort have been used in other candidate gene association studies as previously described [34–41].

South African pediatric cohort

Study participants were enrolled by the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative (SATVI) at field sites in Worcester, South Africa [42–45]. This region has one of the highest incidences of pediatric TB disease in the world [46]. The cohort used in the current study is part of a larger BCG vaccination correlates of risk project with 11,680 infants [43, 46]. Enrolled infants were vaccinated with BCG at birth, as is standard practice in South Africa. A nested genetics case-control study was performed to identify cases and controls during a 2-year prospective observation period. The cases and controls included those from Cape Mixed Ancestry (CMA) and Black African descent. The CMA ethnicity represents the genetic admixture of Khoesan, Black African, European and both east and south Asian populations that has existed for over 350 years [47, 48]. Several terms have been used to describe CMA including South African Mixed Ancestry and “Coloured”, a collective term for people of mixed ancestry in southern Africa, which is an officially recognized census term in South Africa and routinely used for self-classification.

The criteria for the case definition of TB disease has been described previously [46]. Community-wide passive surveillance systems identified patients with TB disease and children with symptoms concerning for TB disease. Briefly, all children with symptoms consistent with TB disease or who had contact with an adult with TB disease were admitted to a dedicated research ward for examination, chest imaging, tuberculin skin testing, two early-morning gastric aspirates, and two induced sputa for Mtb smear and culture. Subjects were described as “definite TB” if they had a positive Mtb culture, smear, or PCR from one of their samples. Subjects were described as “probable TB” if they had a chest radiograph consistent with or suggestive of TB in addition to one or more laboratory or clinic features (smear negative, cough >2 weeks, PPD skin test ≥ 15mm, failure to thrive, and recent weight loss). Subjects diagnosed with TB by the treating physician and with 2 or more clinical features suggestive of TB but without consistent chest radiography were described as “possible TB”. All others were described as “not TB”.

Two groups of controls were included in our analysis, household contact controls and community controls. Household contact controls (HHCs) were study participants who lived in the same household as an adult with active TB disease but who themselves did not develop TB disease over the study period. Community controls had no history of TB disease and were not enrolled until they were at least 2 years old. Both HHCs and community controls were unrelated to cases.

Exclusion criteria included HIV positive infant or mother, BCG vaccine not administered within 24 hours of birth, significant perinatal complications in the infant, any pre-existing acute or chronic disease in the infant, or clinically apparent anemia. For community controls, household contact with any person with TB disease or person who was coughing was an additional exclusion criteria. Parents or legal guardians of study participants were informed of the risks and benefits of study participation and signed informed consent prior to enrollment. The protocol was approved by the University of Cape Town Research Ethics Committee and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

2.2. SIGLEC14 genotyping

Genomic DNA was prepared from peripheral blood or buccal cells using the QIAmp DNA Blood or Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Genotyping for the SIGLEC14 null allele was performed using the TaqMan Copy Number Assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Assay Hs03319513_cn) on an Applied Biosystems Step One Plus Real Time PCR machine. For quality control, we confirmed approximately 15% of TaqMan Assay results by PCR with primers designed to amplify the SIGLEC14 wild type or null allele as previously described [27]. We found >98% agreement between the TaqMan Copy Number Assay and standard PCR. Samples for which the assays gave discrepant genotype results were not included in the analysis.

2.3 M. tuberculosis genotyping

For a subset of Vietnamese patients with PTB or TBM, Mtb was isolated and genotyped as previously described [49]. Briefly, bacterial DNA was extracted from cultures on Lowenstein-Jensen media. Isolates were genotyped by four established methods: IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP), spacer oligonucleotide typing (spoligotyping), 12 allele mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit (MIRU) typing, and large sequence polymorphisms (LSP) defined by deligotyping. Phylogenetic trees were created using Bionumerics software [49].

2.4. T-cell cytokine assays

As a part of the larger SATVI project described above, whole blood was collected from participants at 10 weeks of age. Samples were then analyzed ex-vivo for secreted cytokine responses to BCG stimulation [42, 43]. We stimulated whole blood with BCG for 7 hours and subsequently measured IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-13, and IL-17 production using ELISAs.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used STATA 11.2 (StataCorp) to conduct Pearson’s χ2 testing as well as logistic regression on the case-control cohorts and Cox linear regression to evaluate mortality. To control for potential genetic heterogeneity in the CMA ethnicity, we included a set of 96 Ancestry Informative Markers (AIMs) for the complex five-way admixed South African Coloured population as previously described [50]. In CMA individuals, there were no significant differences in genotype frequencies of the AIMs between cases and controls. The AIMs were used to calculate a coefficient incorporating the first five principal components of the AIMS data, which accounted for over 60% of the variation in the dataset. We then used this data to create a regression coefficient for adjusting the primary case-control data for ethnicity by converting it into an ethnicity principal component coefficient using the “pca” command in STATA 11. This provided an alternative means of regressing for ethnicity within the CMA population. Results of South African peripheral blood cytokine assays were analyzed for association with SIGLEC14 genotype using a general linearized model in STATA 11. Vietnamese cerebrospinal fluid cytokine levels were compared to SIGLEC14 genotype using the Mann-Whitney U test.

2.6. Mtb replication in Siglec-5/14 overexpressing THP-1 cells

THP-1 macrophage-like cells stably overexpressing Siglec-5, Siglec-14, or transfected with empty plasmid have been described previously [27, 29, 51]. Overexpression of Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 mRNA relative to empty vector controls was confirmed by RT-PCR (data not shown). Transfected THP-1 cell lines were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 100,000 cells/well. PMA was added at a final concentration of 50ng/ml and cells were incubated at 37°C overnight. Media containing PMA was subsequently removed and replaced with fresh media. Cells were then infected with Mtb, strain Erdman, that was transfected with a plasmid containing the LUX operon under the control of a Mycobacterial optimized promoter (gift of Dr. Jeffrey Cox) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 or 10. With this system, luciferase expression, as measured by relative light units, serves as a proxy for colony count with a linear relationship over the levels of expression observed (data not shown).

Infections were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours, after which cells were washed x 1 with media and then replaced with fresh media. For each cell line, infections were performed in sextuplet. As a background control, luciferase-expressing Mtb was also added to wells containing media alone (no mammalian cells). The background control wells were otherwise treated in the same manner as those wells containing mammalian cells. Luminescence readings were taken at day 0 and then daily from day 3 until day 7. Means of daily luminescence values, standard deviations, and two-tailed Student’s t tests were performed and graphed using GraphPad Prism Version 6.0.

3. Results

3.1. Association of the SIGLEC14 null allele with protection from tuberculosis disease in Vietnam

Using a case-population study design in Vietnamese adults, we genotyped the SIGLEC14 null allele in 378 cord blood controls and 773 cases of TB disease (Table 1). The TB disease cohort was comprised of 380 cases of PTB without extrapulmonary involvement and 393 cases of TBM (together, labeled ‘AllTb’). The allele was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in the control population (χ2 p=0.60). The SIGLEC14 null allele was more common than the wild-type allele in the Vietnamese population, with a null allele frequency of 61%. We found a trend towards association between SIGLEC14 genotype and AllTb (p=0.063, Pearson’s χ2 test with genotypic model). The association best fit a dominant genetic model with a lower frequency of individuals with the SIGLEC14 null allele in cases compared to controls (p=0.028, OR=0.69 for unadjusted dominant model; p=0.032 with OR=0.65 when adjusted for gender).

Table 1.

The SIGLEC14 null allele in a Vietnamese adult cohort

| SIGLEC14 Genotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | WT/WT N (%) |

WT/Null N (%) |

Null/Null N (%) |

Geno (p) | Dom (p) | OR | 95% C.I. |

| Control | 378 | 55 (15) | 172 (46) | 151 (40) | ||||

| AllTB | 773 | 153 (20) | 311 (40) | 309 (40) | 0.063 | 0.028 | 0.69 | 0.49–0.97 |

| PTB | 380 | 72 (19) | 153 (40) | 155 (41) | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.5–1.1 |

| TBM | 393 | 81 (21) | 158 (40) | 154 (39) | 0.071 | 0.027 | 0.66 | 0.45–0.96 |

The SIGLEC14 null allele in Vietnamese adults with pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) or tuberculous meningitis (TBM) compared to cord-blood controls from the same population. ‘WT’ indicates the wild-type allele, which contains the SIGLEC14 gene. ‘Null’ indicates the null allele, in which SIGLEC14 is deleted. Results of the Pearson’s χ2 test are shown as well as results of the dominant (Dom) model. The PTB and TBM cohorts were combined (AllTB) for the same analysis.

We next looked for an association between SIGLEC14 genotype and the subgroups of PTB and TBM. We found a trend towards a significant association with TBM (p=0.071, Pearson’s χ2 test with genotypic model) that best fit a dominant model (p=0.027, OR=0.66). The association remained significant when adjusting for gender (p=0.031, OR=0.62). We did not observe an association between SIGLEC14 genotype and PTB (p=0.18, Pearson’s χ2 test with genotypic model).

3.2 SIGLEC14 null allele, TB meningitis outcomes, and Mtb genotypes in Vietnam

We next studied the relationship between the SIGLEC14 genotype and clinical characteristics of the TBM subgroup. We looked for an association between genotype and the clinical manifestations of TBM including disease severity, grade, Glasgow coma scale, and focal neurologic deficit at the time of clinical presentation. SIGLEC14 genotype was not associated with any of the recorded neurological assessments (data not shown). We also compared SIGLEC14 genotype with cerebrospinal fluid findings in patients with TBM but did not find an association between genotype and any CSF markers including WBC count, neutrophil and lymphocyte differential, or CSF concentrations of TNF, IFN-γ, IL-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, or IL-13 (sample size of approximately 100 individuals, data not shown). Lastly, the null allele was not associated with 9-month mortality (data not shown).

To determine if the SIGLEC14 null allele influenced the infecting strain of Mtb, we compared the Mtb lineage of isolates both from patients with PTB and TBM and compared for association with SIGLEC14 genotype (Table 2). We did not find an association with genotype and Mtb strain with either non-Beijing or Beijing lineage.

Table 2.

The SIGLEC14 null allele and Mtb lineage in Vietnam

| TB Lineage | N | WT/WT N (%) |

WT/Null N (%) |

Null/Null N (%) |

χ2 (p) | Dom (p) | OR | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AllTB | ||||||||

| non-Beijing | 161 | 31 (19) | 73 (45) | 57 (35) | ||||

| Beijing | 169 | 37 (22) | 65 (38) | 67 (40) | 0.45 | 0.55 | 1.2 | 0.7–2.0 |

| PTB | ||||||||

| non-Beijing | 80 | 13 (16) | 40 (50) | 27 (34) | ||||

| Beijing | 100 | 20 (20) | 37 (37) | 43 (43) | 0.21 | 0.52 | 1.3 | 0.6–2.8 |

| TBM | ||||||||

| non-Beijing | 81 | 18 (22) | 33 (41) | 30 (37) | ||||

| Beijing | 69 | 17 (25) | 28 (41) | 24 (35) | 0.93 | 0.73 | 1.14 | 0.54–2.4 |

The SIGLEC14 null allele frequency in Vietnam based on Mtb lineage for PTB, TBM, and AllTB groups. Results of Pearson’s χ2 test are shown as well as results of the dominant (Dom) model.

3.3. SIGLEC14 null allele and BCG-induced cytokine responses in South Africa

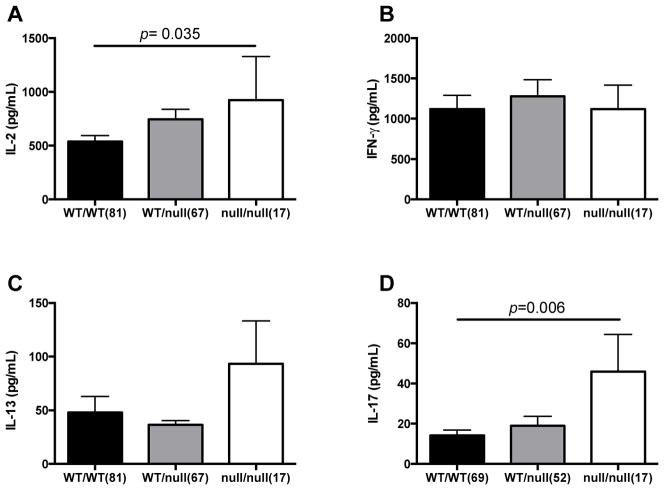

To examine how SIGLEC14 modulates susceptibility to TB disease, we considered adaptive and innate immune mechanisms in a South African pediatric cohort. We first examined whether SIGLEC14 influences BCG-induced cytokine responses. Following vaccination with BCG at birth, infants had blood drawn at 10 weeks of age to examine BCG-specific cytokine response by re-stimulating whole blood ex-vivo with BCG and measuring secretion of IL-2, IL-13, IFN-γ, and IL-17 (Figure 1). Both IL-2 and IL-17 secretion were significantly higher with the null allele under a general linearized model (p=0.035 and 0.006, respectively), though the IL-2 association does not remain significant when corrected for multiple comparisons (4 cytokines evaluated). In contrast, the SIGLEC14 null allele frequency was not associated with IFN-γ or IL-13 levels. These data suggest that the SIGLEC14 null allele is associated with higher BCG-specific IL-2 responses and support a possible mechanism of protection from TB disease.

Figure 1. BCG-induced T-cell cytokines and the SIGLEC14 null allele.

After vaccination at birth, infants had blood drawn at 10 weeks of age. The blood was stimulated ex-vivo with BCG for 7 hours before harvesting supernatants. An ELISA was used to measure secreted cytokines. A general linearized model was used to compare cytokine levels stratified by SIGLEC14 genotype for IL-2 (A), IFN-γ (B), IL-13 (C), and IL-17 (D). WT/WT = homozygous for SIGLEC14. WT/null = heterozygous for the SIGLEC14 null allele. Null/null = homozygous for the SIGLEC14 null allele.

3.4. The SIGLEC14 null allele was not associated with susceptibility to pediatric TB disease in South Africa

To examine whether the SIGLEC14 null allele was associated with susceptibility to pediatric TB disease, we used a case-control study design in a South African cohort. We genotyped 201 cases of children with TB disease and 575 controls (Table 3). The allele was in Hardy Weinberg equilibrium for the self-reported Cape Mixed Ancestry (CMA) control population but was close to the threshold for rejection (χ2 p=0.012, with a threshold for rejecting equilibrium of p<0.001), suggesting the possibility of population admixture. To mitigate this possibility we adjusted our data with a principal components analysis using ancestry informative markers as described below.

Table 3.

The SIGLEC14 null allele in a South African pediatric cohort

| SIGLEC14 Genotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | WT/WT N (%) |

WT/Null N (%) |

Null/Null N (%) |

Geno (p) | Dom (p) | OR | 95% C.I |

| Control | 575 | 295 (51) | 212 (37) | 68 (12) | ||||

| TB | 201 | 90 (45) | 84 (42) | 27 (13) | 0.28 | 0.11 | 1.3 | 0.94–1.8 |

The SIGLEC14 null allele frequency in a South African pediatric cohort. Results of Pearson’s χ2 test are shown as well as results of the dominant (Dom) model.

For our primary analysis, we did not find a significant association between SIGLEC14 genotype and TB disease (p=0.28, genotypic model, Pearson’s χ2 test). The association was not significant under a dominant model (p=0.11, OR=1.3, 95% C.I.= 0.94–1.8) nor was there an association when adjusting for gender (p=0.14, OR=0.79, 95% C.I.=0.57–1.08, dominant model). To distinguish ethnicity within South African populations we adjusted our data with a principal components analysis using 96 ancestry informational markers and again found no association (p=0.62, OR=1.14, 95% C.I.=0.75–1.74, dominant model). Together, these analyses suggested that the SIGLEC14 null allele is not associated with pediatric TB in South Africa.

3.5. Live Mtb replication assay

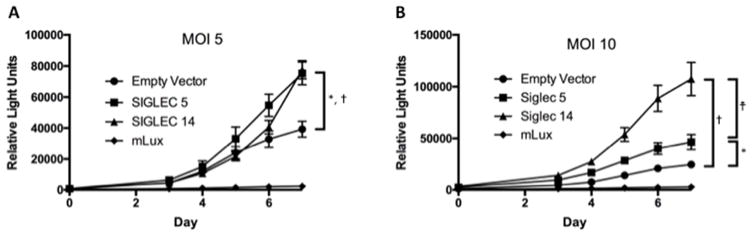

We next examined innate mechanisms of protection and whether Siglec-5 or Siglec-14 regulate Mtb replication in monocytes. We assessed Mtb replication in THP-1 cells stably transfected with either Siglec-5 or Siglec-14. The wild-type THP-1 cell line is heterozygous for the null allele based on our genotyping (data not shown). We observed more replication in both Siglec-5 and Siglec-14-overexpressing cell lines relative to the empty vector control (Figure 2, p<0.001 at day 7 comparing either Siglec-overexpressing cell line with the empty vector in each experiment using an unpaired Student’s t-test). A multiplicity of infection of 5 versus 10 yielded similar results. We did not observe a consistent difference between Mtb replication in THP-1 cells overexpressing Siglec-5 relative to Siglec-14. Together, these data demonstrate that overexpression of either Siglec-5 or Siglec-14 yields greater Mtb replication in-vitro than background expression in a THP-1 monocyte-like cell line.

Figure 2. Mtb Replication in Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 overexpressing monocyte cell lines.

THP1 cells stably transfected with plasmid inducing overexpression of Siglec-5, Siglec-14, or cassette only (Empty Vector) were infected with luciferase-expressing MTb (Erdman strain) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 (A) or 10 (B). Two hours after infection of PMA-differentiated THP1s, cells were washed to remove Mtb. Daily luminescence readings were obtained on day 0 and days 3–7. Background controls (mLUX) consist of wells without THP1 cells. Exposures were performed in sextuplet and the experiment was conducted four times with an MOI of 5 and once with an MOI of 10. Representative results are shown. Results of unpaired t-tests are shown comparing Empty Vector, Siglec-5, and Siglec-14 overexpressing lines for day 7 (*: p<0.0001, Siglec-5 vs Empty Vector; †: p<0.0001, Siglec-14 vs Empty Vector; †: p<0.0001, Siglec-5 vs Siglec-14).

4. Discussion

In Vietnamese adults, we found that the SIGLEC14 null allele was associated with protection from disease in the combined PTB and TBM cohort. The protection was strongest in the TBM subgroup. In South African children, the null allele showed a borderline association with increased BCG-specific IL-2 and IL-17 responses following BCG vaccination. Our in-vitro analysis showed that overexpression of either Siglec-5 or Siglec-14 led to increased Mtb replication in monocytes.

While the presence of the SIGLEC14 null allele was associated with a decreased risk of TB disease in the Vietnamese adult cohort it was not associated with susceptibility in South African children. This observation might be explained by markedly different disease phenotypes in children and adults. Following initial exposure to Mtb, children are more likely than adults to develop TB disease rather than latent infection and more frequently present with extrapulmonary manifestations including miliary tuberculosis [52–54]. TB disease in children often occurs shortly after primary exposure to the bacillus in the absence of a pre-existing Mtb-specific adaptive immune response. In contrast, adult TB disease often occurs after re-activation of latent Mtb infection in the presence of Mtb-specific T-cell responses.

The presence of the null allele in Vietnam conferred protection against TB disease that was strongest in the TBM subgroup. Though the mechanism by which Mtb enters the meninges is not completely understood, the classic two-step model describes hematogenous dissemination and seeding of the meninges early in infection, followed by rupture and bacterial release into the cerebrospinal fluid [55]. Our results from Vietnam suggest that Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 may mediate protection at a stage that is specific to this mechanism and that is not shared with the establishment of infection in the lungs. Alternatively, the subgroup analysis may not be sufficiently powered to identify an association with PTB. The association of the SIGLEC14 null allele with BCG-specific IL-2 and IL-17 responses suggests that adaptive immune responses may mediate Siglec-5/14-dependent protection in adults. In contrast, the absence of association with protection in children may be due to different pathogenic mechanisms of disease that occur in the absence of well developed Mtb-specific adaptive immune responses.

Since Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 are expressed primarily on granulocytes and monocyte/macrophage lineages and only minimally expressed on T-lymphocytes [27, 31], we hypothesized that Siglecs could regulate antigen presentation in dendritic cells and modulate T-cell responses to infection. The increase in BCG-induced secretion of the pro-inflammatory IL-2 in the presence of the null allele is partially consistent with an expected model of higher TH1-type adaptive immune responses leading to protection from TB disease [56]. Since null allele macrophages express less of the pro-inflammatory Siglec-14 relative to the anti-inflammatory Siglec-5, it may be counterintuitive that the null allele would be associated with higher levels of the TH1 and TH17-type T-cell cytokine since we would expect T-cells to be activated by pro-inflammatory macrophage and dendritic cell signals. However, we previously found that TLR1/6-deficient individuals (defined by single nucleotide polymorphisms that regulate signaling in monocytes) had increased BCG-specific TH1 T-cell polarization and IL-2 secretion in the same cohort [42]. The hyporesponsive TLR polymorphisms were associated with decreased IL-10 and a shift in the ratio of IL-10 to IL-12 which could lead to increased TH1 polarization. A similar mechanism might explain our findings with Siglec-5 and Siglec-14. Expression of these two Siglecs is less well characterized in dendritic cells than in macrophages. Siglec-5 expression has been observed in dendritic cells differentiated from circulating monocytes in-vitro and from plasmacytoid dendritic cells from peripheral blood [57], though this observation was made prior to the discovery of SIGLEC14 and the recognition that most antibodies against Siglec-5 are cross reactive with Siglec-14. An additional consideration is that DAP12, to which the Siglec-14 cytoplasmic domain is complexed, might have a suppressive function in DCs; prior evidence suggests the dual functionality of this adapter molecule in different cell types [58]. Whether Siglec-5/14 regulation of DC function modulates BCG-specific adaptive immune responses requires further investigation.

Regarding our in-vitro live Mtb replication assays, we initially hypothesized that overexpression of the inhibitory Siglec-5 would result in increased replication of Mtb relative to control lines and that overexpression of the activating Siglec-14 would reduce Mtb replication. This hypothesis would be consistent with recent data showing more Group-B Streptococcus (GBS) growth in the inhibitory relative to the activating Siglec cell line [29]. While overexpression of Siglec-5 allowed for greater Mtb replication, so did overexpression of Siglec-14. Our in-vitro results were not consistent with those seen for GBS, nor were they consistent with our finding of increased protection against TBM in Vietnam in the presence of the SIGLEC14 null allele. One explanation for the in-vitro finding is that Mtb may use the extracellular domains of either Siglec molecule to gain entry into the cell in a manner that does not induce Siglec signaling. Overall, the in-vitro data derived from a manipulated cell line likely does not sufficiently encompass the complexity of the in-vivo relationship between the SIGLEC14 null allele and TB disease.

A limitation to our genetic analyses is the potential for population admixture in either of our cohorts. The SIGLEC14 null allele genotype frequencies in the self-reported Cape Mixed Ancestry control population displayed borderline Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, which suggests either population admixture or genotyping error. The latter possibility is unlikely as we verified our genotyping data with two independent methods for a subset of samples. To control for population admixture in South Africa we used principal components of ancestry informative markers. Even with this adjustment, the data remained non-significant. The Vietnamese population is more homogeneous (>99% Kinh ancestry) with no evidence of significant population admixture [59]. A potential confounder with the Vietnamese cohort is the use of cord blood as a control, which could lead to misclassification of controls that eventually become cases. Although this is possible, the misclassification would be low and correction would likely strengthen our observed association. A further potential limitation in our analysis is the possibility of case-control misclassification, particularly in our pediatric TB cohort given the challenges associated with diagnosing pediatric TB. To avoid misclassification we performed a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded possible and probable TB cases and only compared definite TB cases to controls. This did not alter the outcome of the analysis (data not shown). Additionally, our South African cohort is to our knowledge the largest genetic cohort of pediatric TB worldwide and diagnoses are made by experienced clinicians in a region with one of the highest densities of TB in the world.

The presence of the SIGLEC14 null allele varies widely across different populations worldwide. Prior genotypic data suggests that the null allele frequency is greatest in Chinese and Southeast Asian populations, followed in order of decreasing frequency by Middle Eastern, Sub-Saharan African, and Northern European populations [27]. Our results provide SIGLEC14 genotyping data for the largest Vietnamese and South African populations published to date. Our allele frequencies were consistent with those seen in prior studies, with a null allele frequency of 30% in our South African control population and 63% in our Vietnamese control population. To date, the clinical significance of this genetic event with potentially dramatic phenotypic consequence has only been explored in a small number of studies. Recent work found that the SIGLEC14 null allele was associated with reduced risk of COPD exacerbation [31]. The authors showed that nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, a common cause of COPD exacerbation, can bind Siglec-14 and induce an inflammatory cascade that may be responsible for the increase in exacerbations in wild-type patients. On the other hand, Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 are expressed in fetal amniotic tissue as well as on leukocytes and the SIGLEC14 null allele was associated with the increased incidence of premature delivery in GBS-positive mothers [29]. Our genotyping data from Vietnam suggests that the differential expression of Siglec-5 or Siglec-14 plays a role in susceptibility to TB. Further mechanistic evaluation will be required to characterize the interaction between Mtb and Siglec molecules.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants in the study. We would also like to thank the immunology and clinical teams at the SATVI research site in Worchester and the Hospital for Tropical Diseases and Pham Ngoc Thac Hospital in Vietnam for obtaining informed consent and collecting and processing blood from the study participants. This research was supported by NIH 5T32HL007287 (ADG), NIH K24 AI089794 (TRH), NIH NO1-AI-70022 (Tuberculosis Research Unit) (TRH, WAH), the Burroughs Wellcome Foundation (TRH), and the Dana Foundation (TRH and WAH).

Abbreviations

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- TB

tuberculosis disease

- PTB

pulmonary tuberculosis

- TBM

tuberculous meningitis

- SIGLEC

sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Global Tuberculosis Report. World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berrington WR, Hawn TR. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, macrophages, and the innate immune response: does common variation matter? Immunol Rev. 2007;219:167–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boisson-Dupuis S, et al. Inherited and acquired immunodeficiencies underlying tuberculosis in childhood. Immunol Rev. 2015;264(1):103–20. doi: 10.1111/imr.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naranbhai V, et al. The association between the ratio of monocytes:lymphocytes at age 3 months and risk of tuberculosis (TB) in the first two years of life. BMC Med. 2014;12:120. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abel L, et al. Human genetics of tuberculosis: a long and winding road. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1645):20130428. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thye T, et al. Common variants at 11p13 are associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis. Nat Genet. 2012;44(3):257–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sester M, et al. Risk assessment of tuberculosis in immunocompromised patients. A TBNET study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(10):1168–76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0967OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis J, et al. Susceptibility to tuberculosis is associated with variants in the ASAP1 gene encoding a regulator of dendritic cell migration. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):523–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comstock GW. Tuberculosis in twins: a re-analysis of the Prophit survey. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;117(4):621–4. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1978.117.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sveinbjornsson G, et al. HLA class II sequence variants influence tuberculosis risk in populations of European ancestry. Nat Genet. 2016;48(3):318–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adami AJ, Cervantes JL. The microbiome at the pulmonary alveolar niche and its role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss G, Schaible UE. Macrophage defense mechanisms against intracellular bacteria. Immunol Rev. 2015;264(1):182–203. doi: 10.1111/imr.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst JD. The immunological life cycle of tuberculosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(8):581–91. doi: 10.1038/nri3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell LD, Varki A. I-type lectins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(24):14243–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crocker PR, et al. Siglecs: a family of sialic-acid binding lectins. Glycobiology. 1998;8(2):v. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.glycob.a018832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varki A. Since there are PAMPs and DAMPs, there must be SAMPs? Glycan “self-associated molecular patterns” dampen innate immunity, but pathogens can mimic them. Glycobiology. 2011;21(9):1121–1124. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macauley MS, Crocker PR, Paulson JC. Siglec-mediated regulation of immune cell function in disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(10):653–66. doi: 10.1038/nri3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bordon Y. Inflammation: Live long and prosper with Siglecs. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(5):266–7. doi: 10.1038/nri3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varki A. Glycan-based interactions involving vertebrate sialic-acid-recognizing proteins. Nature. 2007;446(7139):1023–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puryear WB, et al. Interferon-inducible mechanism of dendritic cell-mediated HIV-1 dissemination is dependent on Siglec-1/CD169. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(4):e1003291. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suenaga T, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein mediates membrane fusion and entry of neurotropic herpesviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(2):866–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913351107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varki A, Gagneux P. Multifarious roles of sialic acids in immunity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1253:16–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlin AF, et al. Molecular mimicry of host sialylated glycans allows a bacterial pathogen to engage neutrophil Siglec-9 and dampen the innate immune response. Blood. 2009;113(14):3333–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-187302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, et al. Specific inactivation of two immunomodulatory SIGLEC genes during human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(25):9935–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119459109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlin AF, et al. Group B Streptococcus suppression of phagocyte functions by proteinmediated engagement of human Siglec-5. J Exp Med. 2009;206(8):1691–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angala SK, et al. The cell envelope glycoconjugates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49(5):361–99. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.925420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamanaka M, et al. Deletion polymorphism of SIGLEC14 and its functional implications. Glycobiology. 2009;19(8):841–6. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angata T, et al. Discovery of Siglec-14, a novel sialic acid receptor undergoing concerted evolution with Siglec-5 in primates. FASEB J. 2006;20(12):1964–73. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5800com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali SR, et al. Siglec-5 and Siglec-14 are polymorphic paired receptors that modulate neutrophil and amnion signaling responses to group B Streptococcus. J Exp Med. 2014;211(6):1231–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pillai S, et al. Siglecs and immune regulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:357–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Angata T, et al. Loss of Siglec-14 reduces the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(17):3199–210. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1311-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green JA, et al. Dexamethasone, cerebrospinal fluid matrix metalloproteinase concentrations and clinical outcomes in tuberculous meningitis. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simmons CP, et al. The clinical benefit of adjunctive dexamethasone in tuberculous meningitis is not associated with measurable attenuation of peripheral or local immune responses. J Immunol. 2005;175(1):579–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graustein AD, et al. TLR9 gene region polymorphisms and susceptibility to tuberculosis in Vietnam. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2015;95(2):190–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thuong NT, et al. A polymorphism in human TLR2 is associated with increased susceptibility to tuberculous meningitis. Genes Immun. 2007;8(5):422–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horne DJ, et al. Common polymorphisms in the PKP3-SIGIRR-TMEM16J gene region are associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(4):586–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawn TR, et al. A polymorphism in Toll-interleukin 1 receptor domain containing adaptor protein is associated with susceptibility to meningeal tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(8):1127–34. doi: 10.1086/507907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah JA, et al. Human TOLLIP regulates TLR2 and TLR4 signaling and its polymorphisms are associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2012;189(4):1737–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campo M, et al. Common polymorphisms in the CD43 gene region are associated with tuberculosis disease and mortality. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;52(3):342–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0114OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seshadri C, et al. A polymorphism in human CD1A is associated with susceptibility to tuberculosis. Genes Immun. 2014;15(3):195–8. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobin DM, et al. The lta4h locus modulates susceptibility to mycobacterial infection in zebrafish and humans. Cell. 2010;140(5):717–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Randhawa AK, et al. Association of human TLR1 and TLR6 deficiency with altered immune responses to BCG vaccination in South African infants. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(8):e1002174. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kagina BM, et al. Specific T cell frequency and cytokine expression profile do not correlate with protection against tuberculosis after bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of newborns. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(8):1073–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0334OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scriba TJ, et al. Dose-finding study of the novel tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A, in healthy BCG-vaccinated infants. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(12):1832–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davids V, et al. The effect of bacille calmette-guerin vaccine strain and route of administration on induced immune responses in vaccinated infants. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(4):531–6. doi: 10.1086/499825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hawkridge A, et al. Efficacy of percutaneous versus intradermal BCG in the prevention of tuberculosis in South African infants: randomised trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a2052. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tishkoff SA, et al. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324(5930):1035–44. doi: 10.1126/science.1172257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Wit E, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the structure of the South African Coloured Population in the Western Cape. Hum Genet. 2010;128(2):145–53. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0836-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caws M, et al. The influence of host and bacterial genotype on the development of disseminated disease with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(3):e1000034. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daya M, et al. A panel of ancestry informative markers for the complex five-way admixed South African coloured population. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kume A, et al. Long-term tracking of murine hematopoietic cells transduced with a bicistronic retrovirus containing CD24 and EGFP genes. Gene Ther. 2000;7(14):1193–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seddon JA, Shingadia D. Epidemiology and disease burden of tuberculosis in children: a global perspective. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:153–65. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S45090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marais BJ, et al. The clinical epidemiology of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(3):278–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elkington PT, Friedland JS. Permutations of time and place in tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(11):1357–60. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thwaites GE, van Toorn R, Schoeman J. Tuberculous meningitis: more questions, still too few answers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):999–1010. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindenstrom T, et al. Tuberculosis subunit vaccination provides long-term protective immunity characterized by multifunctional CD4 memory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182(12):8047–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lock K, et al. Expression of CD33-related siglecs on human mononuclear phagocytes, monocyte-derived dendritic cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunobiology. 2004;209(1–2):199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takaki R, Watson SR, Lanier LL. DAP12: an adapter protein with dual functionality. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:118–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khor CC, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for dengue shock syndrome at MICB and PLCE1. Nat Genet. 2011;43(11):1139–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]