Abstract

In multiple neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a prominent pathological feature is the aberrant aggregation and inclusion formation of the microtubule associated protein tau. Because of the pathological association, these disorders are often referred to as tauopathies. Mutations in the MAPT gene that encodes tau can cause frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17), providing the clearest evidence that the tauopathy plays a causal role in neurodegeneration. However, large gaps in our knowledge remain regarding how various FTDP-17 linked tau mutations promote tau aggregation and neurodegeneration, and more generally how the tauopathy is linked to neurodegeneration. Herein, we review what is known about how FTDP-17-linked pathogenic MAPT mutations cause disease with a major focus on the prion-like properties of wild-type and mutant tau proteins. The hypothesized mechanisms by which mutations in the MAPT gene promote tauopathy are quite varied, and may not provide definitive insights into how tauopathy arises in the absence of mutation. Further, differences in the ability of tau and mutant tau proteins to support prion-like propagation in various model systems raises questions about the generalizability of this mechanism in various tauopathies. Notably, understanding the mechanisms of tauopathy induction and spread and tau-induced neurodegeneration have important implications for tau-targeting therapeutics.

Introduction

The microtubule (MT) associated protein tau (MAPT) is an intrinsically disordered protein expressed at its highest levels in neurons throughout the central nervous system. Higher molecular mass isoforms generated through alternative splicing, often termed “big tau,” are expressed primarily in the peripheral nervous system, but are sometimes also observed in spinal cord and skeletal muscle, when exon 4a and exon 6 are translated, respectively(1–3). One of tau’s primary functions is to bind to and promote the assembly and stability of MTs; this binding activity that can be negatively regulated by phosphorylation at select sites(1,4).

Tauopathies refer to a wide range of phenotypically diverse diseases characterized by the aberrant aggregation of tau in neurons and/or glia, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), Pick’s disease (PiD), chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17)(5). First discovered as a MT-associated protein in 1975(6), tau was later found to be the principal component of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), which are hyperphosphorylated proteinaceous inclusions found in AD and other tauopathies(7).

In 1998, autosomal dominant mutations in the MAPT gene that encodes tau were found to cause some forms of FTDP-17(8–10), now referred to as FTDP-17t, proving that tau dysfunction is sufficient for widespread central nervous system neurodegeneration. Disease pathology for individuals with FTDP-17t are characterized by the presence of filamentous tau inclusions throughout the frontal and temporal lobes in neurons and sometimes in glia, accompanied by atrophy in these regions, as well as ventricular dilation(11). These MAPT mutations can cause variable cognitive, behavioral and motor deficits, with an average age of onset of 49 years and duration of disease of 8.5 years(12).

As of 2018, over 50 different pathogenic MAPT missense, silent and intronic mutations have been reported (Figs. 1 and 2, Table 1)(11). Because many of these mutations present neuropathologically in a manner consistent with different sporadic tauopathies such as PSP, CBD, PiD(13–15), there have recently been calls to characterize tauopathy caused by certain mutations as familial versions of these specific diseases(16). Additionally, some of these mutations have been found to be risk modifiers in certain tauopathies, for instance, A152T in AD(17). In addition to phenotypic and neuropathological variability between these mutations, there are also a number of mechanisms by which these mutations are thought to cause disease. Loss of function, including MT binding and assembly, changes in alternative splicing, shifts in protein aggregation kinetics, and more recently, prion-like “seeding,” have all been implicated. Thus, this review focuses on the potential biochemical and cellular mechanisms in which different tau mutants might cause disease- with an emphasis on their ability to aggregate with seeding- and the implications this might have on the study of sporadic tauopathy.

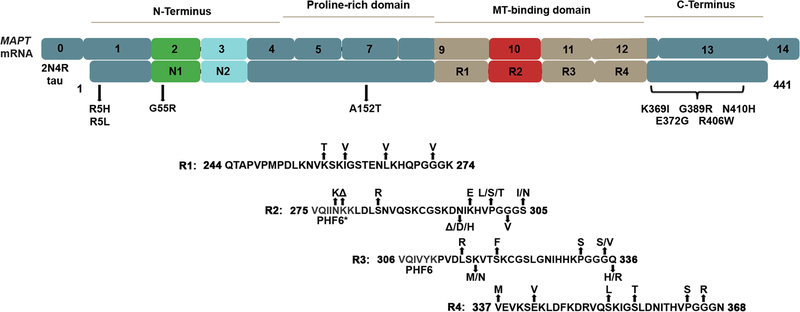

Figure 1. The longest tau isoform found in the human brain, with its corresponding mRNA and known pathogenic missense and deletion mutations.

The MAPT mRNA resulting in 2N4R tau is shown with an embedded number corresponding to the originating exon. Exon 1 contains both untranslated 5’ region and the start of the protein. Exons 2 and 3 are present in this isoform as N1 and N2 inserts; however, in the 1N and 0N isoforms of tau, exon 2 or neither exon 2 or 3 are translated, respectively. MT-binding repeat 2, or R2, is present in this isoform; however, in 3R tau, exon 10 is alternatively spliced and this region is not present in the protein. The different colors serve to highlight regions of the protein that are alternatively spliced as well as the MT-binding domain. The N-terminus, proline-rich, MT-binding and C-terminal regions are indicated above. Below the protein, known pathogenic missense mutations are indicated. Many of these mutations reside in the MT-binding region, and as such the specific amino acid sequence of this area is shown. The PHF6* and PHF6 motifs that are important for tau aggregation are also indicated.

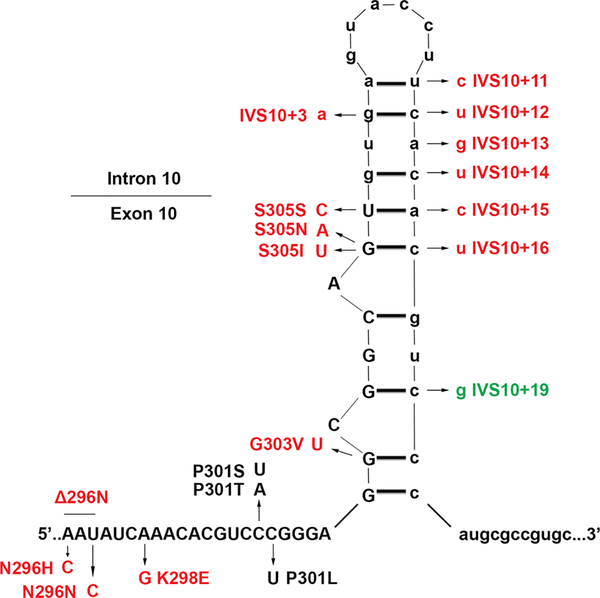

Figure 2. Schematic of the RNA stem loop present at the end of exon 10 and the beginning of intron 10.

Known pathogenic exonic (both missense and silent) and intronic mutations with their corresponding amino acid changes or deletions, when applicable, are shown. The boundary between exon 10 and intron 10 is indicated by the partition at the top left, and also by the use of lower case letters for intron 10. Mutations in this region that have been shown to increase exon 10 inclusion are indicated in red, while those that have been shown to decrease exon 10 inclusion are indicated in green. Mutations that have not been shown to affect splicing are represented in black.

Table 1.

Summary of the reported effects of mutations within the MAPT coding regions on in vitro tau amyloid aggregation, tau’s ability to promote MT assembly, tau MT binding, altered exon 10 splicing and the major tau isoforms present as aggregates in human brains.

| Mutation | Genomic region | Tau aggregation | MT assembly | MT binding | Exon 10 inclusion | Major aggregated tau isoforms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R5H | Exon 1 | ↑ | ↓ | ND | ↔ | 1N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/4R | (126) |

| R5L | Exon 1 | ↑ | ↓* | ND | ND | 1N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/4R (cortical region); 0N/4R, 1N/4R (subcortical region) | (13,112,127) |

| G55R | Exon 2 | ND | ↑ (4R only) | ND | ND | ND | (128) |

| A152T | Exon 7 | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ | ↔ | Variable | (17,129,130) |

| K257T | Exon 9 | ↑ (3R)* | ↓ | ND | ND | All six isoforms or increased 3R | (15,131,132) |

| I260V | Exon 9 | ↑ (4R) | ↓(4R) | ND | ↔ | 0N/4R, 1N/4R, 2N/4R | (131) |

| L266V | Exon 9 | ↑ (3R) | ↓ | ND | ↔ | 0N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/4R, 2N/4R | (133,134) |

| G272V | Exon 9 | ↑ | ↓* | ↔ | ND | 0N/3R, 1N/3R, 2N/3R | (112,135,136) |

| N279K | Exon 10 | ↑ | ↔ | ↔* | ↑ | 0N/4R, 1N/4R | (135,137–140) |

| Δ280K | Exon 10 | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | 0N/3R, 1N/3R | (79,135,138,141–143) |

| S285R | Exon 10 | ND | ND | ND | ↑ | ND | (80) |

| Δ296N | Exon 10 | ↔ | ↓* | ND | ↑* | ND | (112,144,145) |

| N296H | Exon 10 | ↔ | ↓ | ND | ↑ | 4R isoforms | (144,145) |

| K298E | Exon 10 | ND | ↓ | ND | ↑ | ND | (146) |

| P301L | Exon 10 | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↔ | 4R isoforms | (8,112,135,138,140,147–149) |

| P301S | Exon 10 | ↑ | ↓ | ↔ | ND | 4R isoforms | (141,146,150–152) |

| P301T | Exon 10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | (153) |

| G303V | Exon 10 | ↑ | ↓ | ND | ↑ | 4R isoforms | (112,154) |

| S305I | Exon 10 | ND | ND | ND | ↑ | 0N/4R, 1N/4R | (155) |

| S305N | Exon 10 | ND | ↔ | ↔ | ↑ | ND | (137,156) |

| L315R | Exon 11 | ↔* | ↓* | ND | ND | 1N/3R, 2N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/4R, 2R/4R | (112,157) |

| K317M | Exon 11 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | (158) |

| K317N | Exon 11 | ↓(3R) ↑(4R) | ↓ | ND | ND | 4R tau isoforms | (159) |

| S320F | Exon 11 | ↑ | ↓ | ND | ND | 1N/3R, 2N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/4R | (112,116) |

| P332S | Exon 11 | ND | ND | ↔ | ND | All six isoforms | (150,160) |

| G335S | Exon 11 | ↔ | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | (161) |

| G335V | Exon 11 | ↑ | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | (161,162) |

| Q336H | Exon 11 | ↑(3R greater) | ↑ | ND | ND | 1N/3R, 2N/3R | (83) |

| Q336R | Exon 11 | ↑(3R greater) | ↑ | ND | ND | ND | (82,83) |

| V337M | Exon 12 | ↑* | ↓* | ↓ | ND | All six isoforms | (112,147,149,163,164) |

| E342V | Exon 12 | ↔ | ↑ | ND | ↑ | 0N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/4R, 2N/4R | (112,151,165) |

| S352L | Exon 12 | ↑ | ↓ | ↔ | ND | ND | (112,166) |

| S356T | Exon 12 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | (167) |

| P364S | Exon 12 | ↑ | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | (168,169) |

| G366R | Exon 12 | ↔ | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | (168) |

| K369I | Exon 12 | ↓ | ↓* | ND | ND | All six isoforms | (112,170) |

| E372G | Exon 13 | ↑ | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | (171) |

| G389R (G--> A) | Exon 13 | ↑ | ↓* | ND | ↔ | 0N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/3R, 1N/4R | (112,132,172) |

| G389R (G--> C) | Exon 13 | ↑ | ↓* | ND | ND | 0N/3R, 0N/4R, 1N/3R, 1N/4R | (112,172,173) |

| R406W | Exon 13 | ↔* | ↓ | ↓ | ND | All six isoforms | (127,140,148,149) |

| N410H | Exon 13 | ↑ | ↓ | ND | ↑ | ND | (14) |

↑ and ↓ arrows indicate an increase or decrease compared to WT tau, while ↔ means no difference. ND indicates no data. An * indicates that studies have shown differing results; thus, a “↑*” indicates an overall trend towards an increase compared to WT based on available data.

Tau Expression and Splicing

The MAPT gene, located on chromosome 17, is comprised of 16 exons, numbered 0 to 14(5). Exon 1 contains both 5’ untranslated region as well as the start codon of the protein, while exon 14 contains untranslated 3’ region. Splicing variants that include exon 4a are primarily present in the peripheral nervous system, while variants that include exon 6 can be found specifically in the spinal cord and skeletal muscle, resulting in a higher molecular mass protein referred to as “big tau”(1–3,5). In the human brain, six distinct isoforms of tau exist based on alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10(18). Alternative splicing of exons 2 and 3 yield isoforms with 0, 1 or 2 N-terminal repeats (0N, 1N, 2N), while alternative splicing of exon 10 results in tau with three or four MT-binding repeats in the MT-binding domain (3R or 4R)(Fig. 1). While 0N3R tau is the predominant isoform in the fetal brain(19), the overall ratio of 3R and 4R tau isoforms is roughly equal in the adult brain(1,18,20), although this ratio can differ in given regions(21). 0N and 1N tau isoforms comprise 37% and 54% of total human brain tau, respectively, while 2N tau makes up only 9% of total tau isoforms(22). 4R tau isoforms show both increased affinity for MTs as well as greater levels of MT assembly in vitro compared to 3R tau isoforms(23,24). Although the role of N-terminal inserts is less clear, they have been implicated in regulating MT stabilization and plasma membrane interactions(25,26). Additionally, co-immunoprecipitation studies in mice have shown that 0, 1 and 2N isoforms interact with different proteins preferentially(27), and that there are regional differences in expression of these isoforms in the brain(28).

Alternative RNA splicing of tau is regulated by several cis-elements and trans-acting factors(29). Exon 10 in particular is flanked by an abnormally large intron 9 and has a weak 5’ and 3’ splice site, which can be acted upon by these cis-elements and trans-acting factors(30). Additionally, the 3’ end of exon 10 and the 5’ end of intron 10 form a highly self-complementary stem-loop (Fig. 2), which inhibits binding of the U1 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecule, part of the small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle (snRNP) that functions to bind to the pre-mRNA and catalyze the removal of introns(29). Disruption of this loop leads to increased binding by the snRNP and higher levels of exon 10 inclusion(30). This destabilization can also be seen in rodents, where the presence of a guanine instead of an adenine at position IVS10+13 and leads to the predominance of 4R tau in these animals(29). Thus, mutations within specific cis-elements can promote or suppress inclusion of this exon, while mutations specifically within the stem loop tend to promote exon 10 inclusion (Fig. 2).

Two major haplotypes of tau, H1 and H2, are formed primarily by the 900kb inversion in the q21 region of chromosome 17 and a 238bp deletion in intron 9 in H2(3). Furthermore, a number of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the H1 haplotype produce several sub-variants, some of which are associated with increased risk of certain tauopathies, such as CBD and PSP(31–33). Mechanistically, it is thought that distinct haplotypes, particularly H1c, can promote tauopathy through increased expression of 4R tau, as is seen in some FTDP-17t mutant tauopathies(34).

Tau Structure and Aggregation

Four general domains of tau include the N-terminal acidic projection domain, the proline-rich domain, the MT-binding domain, and the C-terminal tail (Fig. 1). Although tau is intrinsically disordered and natively unfolded(35,36), it can adopt a “paperclip” like structure, in which the MT-binding domain and the N-terminus approach and interact with the C-terminus(37). Preclusion of this structure, either through interaction with other molecules, post-translational modifications, truncations or mutations, could potentiate abnormal aggregation. The MT-binding repeats also comprise the “paired-helical filament core,” or PHF core, which serves as the primary structure of aggregated tau filaments(38). Within this structure are two hexapeptide motifs, termed PHF6* and PHF6, which are important for aggregation, and the latter which is necessary and sufficient for beta-sheet aggregation in tau(39–41). Recent cryo-electron microscopy studies of the PHF core from both AD and PiD tau filaments further confirm key areas of β-sheet forming residues in this core(42,43). Overall, missense MAPT mutations that disrupt the proposed “paperclip” structure of tau, or promote and stabilize the PHF core of tau, are likely to promote aggregation and inclusion formation.

The process by which tau polymerizes to form amyloid in vivo is not completely understood. Nevertheless, “nucleation-elongation” is a potential mechanism that can contribute to this process in which tau initially forms an oligomeric nucleus or “seed” before elongating into tau filaments(44,45). As such the formation of this oligomeric nucleus is the rate-limiting step, after which tau can elongate rapidly by attaching to the growing ends of the fibril(45–47). It has recently been proposed that tau can undergo liquid-liquid separation to form condensed liquid droplets within cellular physiological conditions, which could serve as a precursor for this initial tau β-sheet formation and aggregation(48). Experimentally, this rate-limiting step can be potentially overcome by introducing pre-formed “nuclei” of tau that can act as a template for soluble tau to quickly bind to and polymerize onto, in a process known as seeding(49). This mechanism is akin to the misfolding of prion protein, in which exogenous or intrinsic pathogenic prion conformers act as a templates that induce conformational change in the native protein, inducing misfolding, further aggregation, and neurodegeneration(50). In a similar manner, it is thought that certain neurodegenerative proteinopathies can spread to anatomically connected regions through template-assisted conformational changes, in which soluble protein is induced to become pathological. This concept is further supported based on AD autopsy series studies, as Braak stages I-VI(51), in which tau pathology in AD can be defined in a regionally specific and somewhat predictable manner. Evidence that tau aggregation can be induced by exogenous tau aggregates and subsequently spread in this manner- through some combinatorial process of synaptic or exosomal secretion followed by endocytotic or exosomal uptake, for example(49,52)- has been shown in vivo in various types of cell culture systems and in animal studies (Tables 2–4). Of note, many of these studies heavily utilize specific mutants that may serve to enhance or act as a primer for this process (Tables 2–4).

Table 2.

Summary of tau seeding studies in cultured cells.

| Tau protein expressed | Seed Used | Cell type | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (2N4R) Tau-YFP or WT (RD) Tau-YFP | RD tau fibrils | HEK293 and C17.2 neural cells | RD-YFP tau formed inclusions when expressed without seeding; induced aggregation of 2N4R WT tau-YFP when cells treated with RD fibrils | (88) |

| WT (1N4R or 1N3R) Tau | 1N4R or 1N3R tau fibrils | SHSY5Y | Some induced aggregation of 4R tau by 4R tau seeds; limited 3R tau seeding; no tau isoform cross-seeding | (89) |

| P301L, Δ280K, R406W, and WT (2N4R) Tau | WT (myc-K18) or P301L (myc-K18) tau fibrils | QBI293 | Robust seed-induced tau aggregation only of P301L tau; induced seeding for WT and other tau mutants was minimal | (96) |

| P301L and WT (2N4R) Tau | α-synuclein fibrils | QBI293 | Robust seeding induced tau aggregation only for P301L tau | (95) |

| WT (2N4R) Tau-GFP | AD PHFs | SHSY5Y and HEK293T | Sarkosyl-insoluble tau detected in both cell types after treatment with PHFs | (174) |

| P301S (1N4R) and WT mouse Tau | P301S (myc-2N4R),WT (myc-2N4R), P301L (myc-K18) or WT (myc-K18) fibrils | PNCs from PS19 transgenic mice and naive mice | Induced P301S tau aggregation after seeding with K18/P301L fibrils; apparent seeding barrier between WT and P301 mutant tau | (93) |

| P301S (1N4R) Tau | Myc α-synuclien fibrils or WT α-synuclien fibrils | PNCs from PS19 and naive mice | Seed-induced aggregation of P301S tau after α-synuclein seeds passaged in vitro, and limited seeding of endogenous tau from naive PNCs after multiple in vitro passages | (175) |

| P301S (RD) Tau | RD tau fibrils, AD brain lysates, PS19 brain lysates | HEK293T | RD tau fibrils, AD and PS19 brain lysates all induced seeding of P301S tau, with the seeding activity of PS19 mouse lysate increasing with age | (91) |

| WT, Δ280K, ΔK280/I277P/I308P, or P301 L/V337M (RD) Tau-YFP; P301S or WT (1N4R) Tau; P301S or WT (1N4R) Tau-YFP | RD tau fibrils or α-synuclien fibrils; cell lysate containing stably expressed RD P301L/V337M tau aggregates | HEK293; PNCs from naïve mice | RD tau fibrils seeded all mutant tau RD variants except for ΔK280/I277P/I308P (anti-aggregation) tau; α-synuclien fibrils did not cross-seed P301S (1N4R) or RD tau; cell lysate from cells expressing P301L/V337M (RD) tau aggregates seeded PNC expressing P301S tau but not WT tau | (92) |

| P301S (1N4R) or WT Tau | P301S (0N4R) fibrils or Sarkosyl-insoluble lysate from hTau P301S (0N4R) | HEK293T | P301S tau seeded more robustly compared to WT tau; sarkosyl-insoluble brain lysate is a more potent seed than untreated brain lysate or recombinant fibrils | (94) |

| P301S (1N4R) Tau | TgP301S lysate (sucrose gradient fractionated) | HEK293T | Most efficient seeding was achieved with high molecular weight tau fractions comprised of short fibrils | (100) |

| P301L (RD) Tau | RD fibrils or AD-derived tau | HEK293T | Both recombinant and AD-derived tau need to be at least a trimer for uptake and seeding to occur in these cells | (176) |

| P301L or WT (0N4R) Tau | P301L (K18) fibrils | Neural progenitor cells (iPSCs) | Aggregation of P301L tau but not WT tau was seed-induced | (113) |

| WT (2N3R) Tau-GFP | Sarkosyl-insoluble AD brain lysate | CHO cells | PHFs were internalized into cultured cells without the use of a transfection agent; resulted in limited seeding of tau | (177) |

| P301S (1N4R) Tau | P301L (K18) or WT (K18) fibrils | PNCs from TgP301S mice or HEK293 cells | Aggregation of P301S tau in both cells types after seeding with K18 P301L or WT fibrils | (105) |

| P301S (RD) Tau or P301S (1N4R) Tau-YFP | Lysate from cells containing stably aggregated P301L/V337M (RD) tau | Mouse PNC | Multiple “strains” from cell lysate seeded both RD tau and P301S 1N4R tau, with variations in the timing of induction of aggregation | (101) |

| P301L (2N4R) Tau-GFP | P301L (myc-K18) fibrils; Aβ42 fibrils | QBI293 | Pre-aggregated Aβ42 fibrils induced limited aggregation of P301L tau compared to K18 fibrils; Aβ42 fibrils increased seeding of P301L tau when used in conjunction with K18 tau fibrils | (106) |

| P301L/V337M (4RD) or L266V/V337M (3RD) Tau-YFP | AD, AGD, CBD, CTE, PSP brain homogenate | HEK293T | Cross-seeding barriers in 4R or 3R tau seeding; AD and CTE brain homogenate seeded co-expressed 3R and 4R tau or overexpressed 4R tau | (111) |

| P301S (RD) Tau | Brain lysate from AD patients at Braak stages I-II, III-IV, or V-VI | HEK293T | Overall seeding activity increased with Braak staging of lysate | (178) |

| P301S (RD) Tau | Homogenized formaldehyde-fixed tissue from PS19 mice | HEK293T | Extended water bath sonication rescued seeding from fixed tissue; tau seeding activity correlated with increased levels of mouse pathology | (179) |

| WT, R5H/L, K257T, L266V, G272V, N279K, Δ280K, K298E, P301L/S/T, G303V, G304S, S305N, S320F, P332S, V337M, E342V, P364S (0N4R) Tau; WT and P301L (2N4R) Tau | WT (K18) and mutant (K18) fibrils | HEK293T | P301L, P301S, P301T and S320F tau showed robust aggregation with seeding compared to WT tau and other mutants; seeding capacity between recombinant WT K18 fibrils and homotypic mutant fibrils was the same; no difference in aggregation with seeding for 2N4R versus 0N4R tau | (109) |

| P301S (RD) tau | Brain homogenate from AD patients at various Braak stages | HEK293 | Lysate from regions showing tau pathology and regions subsequent in the Braak staging pathway seeded P301S tau | (180) |

The form of tau expressed is shown in the left column, with emphasis on the isoform and specific mutation. The “seeds” used, the cell type, and the major findings of the experiments are specified in the next columns, respectively. PNC = primary neuronal cultures; YFP = yellow fluorescent protein; RD = repeat domain; 4RD = 4 repeat domain; 3RD = 3 repeat domain; WT = wild type; Tg = transgenic; nTg = non-transgenic

Table 4.

Summary of in vivo tau seeding experiments utilizing PS19 mice.

| Seed | Injection Site (age) | Results/Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myc α-synuclien fibrils or WT α-synuclien fibrils | Stereotactic hippocampal (2–3 months) | Tau inclusions at 3 months post-injection near the site of injection as well as contralaterally when these mice were injected with α-synuclein fibrils that were passaged multiple times in vitro | (175) |

| P301S (myc-2N4R) and P301L (myc-K18) tau fibrils, α-synuclein fibrils | Stereotactic hippocampal (2–3 months) | Tau pathology induced at 1 month post-injection which spread and increased at 3 months; no tau pathology seen with α-synuclein fibrils at 3 months post-injection | (102) |

| WT (RD) fibrils, cell lysate with aggregated P301L/V337M (RD) tau, immunoprecipitated P301S (1N4R) tau from seeded PS19 brains | Stereotactic hippocampal (3 months) | Mutant RD aggregates formed in cell culture induced tau pathology in PS19 mice but not nTg mice; lysate from these seeded PS19 mice but not nTg mice can be passaged in vivo or cultured cells | (92) |

| Enriched brain extracts from CBD and AD brains | Stereotactic hippocampal and overlying cerebral cortex (2–5 months) | Induce tau aggregation with CBD and AD extract but not control; tau pathology spread distally | (98) |

| P301S (myc-0N4R) fibrils | Stereotactic in the locus coeruleus (2–3 months) | Tau pathology induced along afferent and efferent connections of locus coeruleus | (184) |

| P301L (K18) fibrils | Stereotactic hippocampal CA1 region, frontal cortex, entorhinal cortex or substantia nigra (3 months) | Gallyas positive pathology and detergent insoluble tau in synaptically connected regions | (105) |

| Lysates from cells containing stably aggregated P301L/V337M (RD) tau that was seeded with various recombinant tau or brain lysate | Stereotactic hippocampal (2–3 months) | Varied tau pathology induced between “strains” of injected cell lysate | (101) |

| Aβ42 seeded P301L (myc-K18) fibrils or homotypically seeded P301L (myc-K18) fibrils | Stereotactic hippocampal and frontal cortex (4 months) | Induced Gallyas pathology at 3 months post-injection; PS19 mice seeded with the Aβ42-seeded K18 fibrils presented with increased AT8 staining compared to homotypically-seeded tau | (106) |

Highlighted are the mouse models, the type of “seeds” used, the method and timing of seed injection, and the outcome of the experiments. Tg = transgenic; nTg = non-transgenic

Tau Function and Post-translational Modifications

Tau resides mostly in the axons of developed neurons, where it has a higher affinity for MTs than in the dendrites(53,54). Additionally, different isoforms of tau can have distinct localization patterns, and missorting of tau into dendrites is an early sign of neurodegeneration in AD(53,55,56). Thus, altered splicing patterns may contribute to tau mislocalization and altered MT stability. Normal tau has roles in regulating axonal transport(57) and promoting neurite outgrowth(58). Knockout mice have further demonstrated important roles for tau in neurogenesis and neuroplasticity, with significant impairments to both in the absence of tau(59,60). Tau also binds to and interacts with a number of other molecules. In particular, the N-terminal domain, which has a negative charge and projects away from the MTs when tau is bound(61), can act as a link to membrane components, particularly annexin 2(62). This region also binds to the p150 subunit of the dynactin complex, which regulates the MT motor protein dynein(63).

Given that tau functions to enhance MT assembly and regulate its stability, which play important roles in neurite outgrowth, cell stabilization and intracellular transport, normal tau activity contributes to maintaining axonal health. Tau binds to the interface between α- and β-tubulin heterodimers specifically with residues interspersed throughout and around the MT-binding repeats(64). Thus, tau mutations within these repeats have the ability to disrupt this interaction, resulting in destabilization of the MTs as well as a potential increase in unbound, free-floating tau, which may also promote tau aggregation (Table 1).

Normally, the process by which tau interacts with MTs is negatively regulated by phosphorylation(4). There are over 80 potential phosphorylation sites (i.e. serine, threonine and tyrosine residues) on the longest isoform of tau, a number of which are abnormally hyperphosphorylated in AD and other tauopathies(53). This hyperphosphorylation may induce the missorting of tau(65), as well as potentially promote aggregation, as shown in vitro(66). Individual missense mutations in tau can not only alter potential phosphorylation sites, but also have been shown to promote phosphorylation compared to WT tau in vitro(67). Lysine acetylation has also been shown to be of importance in regards to tau pathology. Depending on the residue, acetylation can inhibit tau’s degradation and correlate with tauopathy, or promote its degradation and suppress aggregation(68,69). Other post-translational modifications include glycosylation, isomerization, methylation, ubiquitination and truncation(70). N-glycosylation, isomerization and truncation are implicated in promotion and stabilization of PHFs(71–73), while methylation has been shown in vitro to suppress aggregation(74).

Altered Tau mRNA Splicing In Disease

Normally, the ratio of 3R to 4R tau in the adult human brain is approximately equal(1,18,20). In AD, this ratio remains normal(75); however, many tauopathies exhibit altered ratios of tau isoforms, especially within the pathologic inclusions. For instance, PSP and CBD are considered 4R tauopathies, while PiD is considered a 3R tauopathy(1). Interestingly, specific MAPT mutations can cause either 4R or 3R predominant tauopathies as well as tauopathies with equal isoform ratios(76). Intronic pathogenic mutations largely reside in intron 10 and serve to disrupt the mRNA stem-loop, usually causing an increase in 4R tau (Fig. 2). For instance, the most common intronic mutation, IVS10+16 (C to U), serves to increase 4R tau expression by disrupting this stem loop(11), as do a number of other intronic mutations in this area (Fig. 2). Additionally, IVS10+11 (U to C), IVS10+12 (C to U), IVS10+13 (A to G), IVS10+14 (C to U) and IVS10+16 (C to U) reside on an intronic splicing silencer, and all increase exon 10 inclusion, while IVS10+19 (C to G) resides on an adjacent intronic splicing modulator, and increases exon 10 splicing(77). Interestingly, the IVS10+13 (A to G) mutation is naturally occurring in rodents, resulting in a preponderance of 4R tau in these animals(29). Deletion studies have shown that these two regions have opposing effects on splicing(29,30). Two missense mutations that affect splicing in opposing ways are N279K and Δ280K, which are both found around a polypurine enhancer, which interacts with a number of different regulatory splicing sequences(77). While the Δ280K mutation weakens this enhancer, the N279K mutation strengthens it, producing dramatically opposing effects on exon 10 inclusion. The majority of missense mutations that are found in exon 10 are shown to increase the levels of 4R tau expression as revealed by mRNA analysis or and/or protein biochemical profile of patients’ tau isoforms (Table 1). These mutations likely cause disease either through direct disruption of the mRNA stem loop (Fig. 2) or through disruption of splicing enhancers and silencers(18,77). Furthermore, of the silent mutations found in tau, only those residing in exon 10 (L284L, N296N or S305S) or exon 11 (L315L) have shown to be pathogenic, and could also affect splicing by disruption of the stem-loop (S305S) or disrupting or enhancing splicing cis-elements (Fig. 2)(77).

Alterations in the normal ratio of tau isoforms can lead to a number of adverse results, including impaired axonal transport(78). Additionally, for all of the mutations that affect splicing, insoluble tau levels from affected patients’ brains are predominantly but not exclusively comprised of the isoform that is over represented (Table 1)(79,80). Furthermore, because it is proposed that different tau isoforms harbor distinct MT binding affinities and potentially bind unique sites, an overproduction of one isoform over another might lead to an overabundance of free-floating, unbound tau, which is primed for aggregation(23,24,81).

Altered MT Assembly and Binding Due to Tau Mutations

Tau missense mutations can affect MT assembly and binding, thus reducing MT stability, as well as potentially leading to increased levels of unbound, free-floating tau in the cytosol of neurons. In fact, one of most common features among missense mutations is their diminished ability, at least in vitro, to promote MT assembly from tubulin compared to WT tau (Table 1). Conversely, a few mutations such as Q336H and Q336R have a greater ability to promote MT assembly (Table 1)(82,83). Additionally, some missense mutations such as S305N that predominantly affect splicing demonstrate little effect on MT polymerization (Table 1) (84). The impact of tau missense mutations on its interactions with MTs has also been studied in vitro by comparing binding affinity for taxol-stabilized MTs (Table 1). Although this interaction has been not been as extensively studied as MT assembly, typically these data demonstrate a reduced MT binding affinity that is consistent with a reduced ability to induce MT polymerization (Table 1).

Impacts of Tau Mutations on Aggregation and Seeding

Mutations that alter splicing dynamics or that induce loss of function with regard to MT interaction both have the potential to increase the amount of free, unbound forms of tau in the cytosol that can ultimately potentiate aggregation and inclusion formation. In vitro, recombinant tau needs a polyanionic inducer, such as heparin or arachidonic acid, in order to form tau filaments(85). In the cytosol, similar cofactors could promote this aggregation, including RNA(86,87). In addition to specific cofactors, mutations in tau may help to induce aggregation, making tau more susceptible to template-assisted growth. In vitro, a number of tau mutants have been shown to increase the rate at which tau fibrillizes (Table 1).

Some tau mutations can also have marked effects on seed-induced tau aggregation in vivo. Growing evidence in cell culture supports prion-like seeding as a possible mechanism that contributes to pathogenesis (Table 2). Original studies conducted have shown that the addition of exogenous pre-formed tau fibrils can induce tau aggregation in cells expressing WT human tau protein(88,89). Other studies have focused on seeding and aggregation of repeat domain (RD) tau, or tau only containing the MT-binding repeats, as these constructs contain the region responsible for tau fibrillization and are more prone to aggregate when seeded or even simply expressed in culture(44,90–92). The majority of cell culture studies, however, have utilized tau mutants, namely the P301L or P301S mutants, which robustly aggregate with seeding compared to WT tau(91–96). Even when comparing WT RD tau with RD tau containing a P301L or P301S mutation, these differences in aggregation remain(90,92).

Additionally, the type of tau seeds that were used to treat these tau-expressing cells were largely divided into brain lysate from either transgenic mice expressing human tau with a P301L or P301S mutation, human brain lysate from patients with tauopathy, or recombinant tau protein fibrillized in vitro using a polyanionic inducer (Table 2). Comparative studies showed that tau from brain lysates are more potent at inducing aggregation than recombinant fibrils; however, recombinant tau that was “seeded” in cell culture by detergent-insoluble tau from brain lysate can acquire this potency(94).

Evidence for seeding in vivo has been shown in a number of mouse models (Tables 3 and 4), beginning with Clavaguera and colleagues in 2009, where pathology was found at the site of injection with insoluble P301S brain extract in human WT overexpressing mice 6 months post-injection, with limited spread to nearby regions thereafter(97). Subsequent studies have mostly utilized mice expressing human mutant P301L or P301S tau, which have shown significant seeding and synaptic spread of pathology with a variety of “seeds” utilized (Tables 3 and 4). These mice were treated, largely, through stereotactic hippocampal injection at 2–3 months, with brain homogenates from different tauopathies(98), lysate from aged P301L or P301S tau expressing mice(99,100), lysate from cells with stably expressing tau aggregates(92,101), or recombinant fibrils, usually the K18 tau fragment (residues 244–372)(102–106).

Table 3.

Summary of in vivo tau seeding experiments.

| Model/Seed target | Seed | Injection Site (age) | Results/Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alz17 (WT 2N4R tau) Tg and nTg mice | Insoluble brain extracts from 6 month old hTauP301S (0N4R P301S tau) Tg mice | Stereotactic hippocampal (3 months) | Hippocampal Gallyus silver staining at 6 months post-injection in Alz17 mice with limited spread thereafter; silver staining limited to the site of injection that did not increase in number or spread in nTg mice | (97) |

| Alz17 (WT 2N4R tau) Tg and nTg mice | Total brain homogenates from AD, TD, PiD, AGD, PSP and CBD; brain lysate from 24 month old APP23 (mutant APP) Tg mice | Stereotactic hippocampal and overlying cerebral cortex (3 months) | Hippocampal Gallyus-Braak silver staining at 6 months post injection near the site of injection in Alz17 mice, and limited pathology at the site of injection at 6 months post-injection for nTg mice; brain lysate from APP23 mice did not induce tau pathology in Alz17 mice 18 months post-injection | (107) |

| hTauP301S (P301S 0N4R tau) Tg mice | Brainstem extracts from ∼5 month old hTauP301S (0N4R P301S tau) mice | Stereotactic hippocampal and overlying cerebral cortex (2 months) | Gallyas silver staining showed pathology near the site of injection as well as in afferent and efferent connected regions | (99) |

| hTauP301S (P301S 0N4R tau) Tg mice | Insoluble brain extracts from 6 month old hTauP301S (0N4R P301S tau) Tg mice | Intraperitoneal injection (3 months) | Increased Gallyas silver staining at 9 months compared to control | (181) |

| tauP301L (P301L 2N4R tau) Tg mice | P301L (K18) fibrils | Stereotactic hippocampal or frontal cortex (3 months) | Injection resulted in phosphorylated and detergent-insoluble tau in the brain, including contralateral to the site of injection; tau aggregation was dose-dependent | (103) |

| JNPL3 (P301L 0N4R tau) Tg mice | WT (K18) fibrils | Stereotactic hippocampal (2 months) or gastrocneumius muscle (IM) or cisterna magna (ICM) | Limited positive tau pathology only in the site of brain injection and connected entorhinal cortex in female but not male mice | (104) |

| THY-Tau22 (G272V/P301S 1N4R tau) Tg and nTg mice | Sarkosyl-insoluble AD brain lysate | Stereotactic hippocampal (3 months) | Limited Gallyas-positive silver pathology staining at the site of injection in nTg and THY-Tau22 Tg mice; Pathology mostly consisted of murine tau | (177) |

| hTauP301S (P301S 0N4R tau) Tg mice | Sucrose gradient fractionated hTauP301S (0N4R P301S) lysate or brainstem extracts | Stereotactic hippocampal and overlying cerebral cortex (2 months) | Total brainstem lysate and some biochemical fractions from the whole brain induced tau pathology at the site of injection and synaptically connected regions at 10 weeks post-injection | (100) |

| T40PL-GFP (P301L 2N4R tau) Tg mice | P301L (2N4R) fibrils (AD-tau seeded) or tau purified from AD brains | Stereotactic hippocampal (2–3 months) | Induced tau pathology at 3 months post-injection | (182) |

| nTg mice | Sarkosyl-insoluble AD-tau, CBD-tau, PSP-tau | Stereotactic hippocampal and overlying cortex (2–3 months) | Induced tau pathology near injection site | (183) |

Highlighted are the mouse models, the type of “seeds” used, the method and timing of seed injection, and the outcome of the experiments. Tg = transgenic; nTg = non-transgenic

Brain lysates from human tauopathy cases or from aged mutant tau transgenic mice containing tau aggregates appear to generate the most potent seeds(94). Further, using sarkosyl-insoluble lysate or immuno-precipitating tau from these brains rather than total lysate appears to enhance their potency(94), while immuno-depleting tau greatly diminishes this potency(100). This, along with evidence that “strains” of tau aggregates can survive multiple passages through both cell culture and mice(101), points to the importance of conformational templating in this process. Isoform differences could also contribute to differential templating; because the P301 residue only exists in 4R tau, and because murine tau is almost exclusively 4R(19,53), most studies have only compared seeding of 4R expressed tau with 4R aggregates. This differs from the physiological conditions of AD and PiD, as well as many instances of FTDP-17t. In fact, when PiD brain lysates, which predominately contain 3R tau, were used to seed 4R tau in vivo, there was significantly less pathology(107). This apparent seeding barrier has also been seen in vitro and in cell culture(89,108–111), and corroborates the different proposed structures of tau filaments from AD and PiD elucidated by cryo-electron microscopy(42,43).

Differences in the entity of seeds being comprised of either WT or mutant tau appears to matter less than the methods used to generate the seeds (Tables 2–4). For the monomer to be seeded, however, the data in both cell culture and in vivo show the importance of whether WT tau or mutant tau is utilized. Specifically, studies have shown consistent differences in seeding and aggregation propensities between P301L, P301S and P301T mutant and WT tau in vitro, in cell culture and in mouse models(90,92,94–96,109,112,113).

A recent study from our laboratory investigated 19 different pathogenic tau missense mutations in the context of an established cellular seeding assay(109). It was found that the majority of mutants, including WT tau, failed to robustly aggregate with seeding, unlike tau with mutations at the P301 site. This pattern of aggregation with seeding was similar between the known FTDP-17t mutants P301L, P301S and P301T, and even a deletion at the P301 site; additionally, there was no difference in seeding between the 0N4R or 2N4R isoforms(109). Because prolines can serve as inhibitors of β-sheet formation(114), the impact of other proline residues throughout the MT-binding region were investigated; it was found again that the inhibitory effect of P301 on aggregation and seeding was unique, but that re-introducing a proline at residue 302 was sufficient to inhibit seeded-aggregation(109), demonstrating the importance of the local molecular environment.

Another unique mutant that affected tau aggregation was S320F, which was also able to aggregate with seeding in this assay, and even showed some ability to aggregate without seeding(109). Other studies have shown that this mutant is prone to aggregate in vitro and in vivo compared to WT and other tau mutants(112,115). More specifically, this mutation has conferred greater rates of tau nucleation leading to the production of short fibrils(112), which could explain this mutants ability to aggregate without the addition of pre-formed fibrils, since the lag time to create nucleated “seeds” is shorter than for other tau mutants. Mechanistically, this mutation could promote aggregation in a number of different ways. First, while cryo-electron microscopy findings of tau from AD PHFs have shown that, within the amyloidogenic fold, the S320 residue could reside within a hydrophobic pocket(42), the same group found that in PiD tau filaments, cryo-electron microscopy shows S320 most likely resides within a hydrophobic pocket(43); thus the S to F mutation could act by stabilizing this structure. Agreeing with the proposed structure of PiD tau filaments, S320F has been neuropathologically compared to PiD, with an abundance of Pick bodies found in a carrier’s brain(116). Additionally, despite being intrinsically disordered, tau can adopt a protective paperclip-like global conformation, in which the MT-binding repeat, C-terminal and N-terminal approach each other(37). The substitution of a large, aromatic side chain in the region where the C-terminal and MT-binding domain interact could potentially disrupt this fold, facilitating polymerization. This disruption of the paperclip-like structure of tau has been shown in vitro with pseudo-phosphorylation of tau at the AT8 and PHF1 epitopes, which are markers of tau pathology(117). Given these two mutants’ unique properties, it was also found that a double mutant combination of either P301L or P301S with S320F resulted in rapid and robust aggregation even without seeding(109).

The presence of aggregated tau inclusions remains a constant between MAPT mutant cases, despite the potentially different mechanisms that led to those inclusions. The exact source of neurodegeneration, however, is unclear and could be due to a number of factors. In AD, the rate of cognitive decline correlates positively with the number of NFTs in the brain(118), which could cause neurodegeneration through disruption of cytoplasmic organelles or blocking axonal transport(119,120). However, evidence in human AD cases showed that, while correlative, the number of NFTs can far exceed neuronal loss, and in rodent models many neurons have been shown to die without ever forming NFTs(121–123). Soluble, oligomeric species of tau have also been implicated in cellular toxicity when added in culture as well as accelerated pathology when injected into the hippocampus of transgenic mice(124,125); however, the mechanisms of potential toxicity remain unclear. Finally, unbound, aggregate-prone or aggregated tau are unable to perform their normal functions, namely maintaining or assembling MTs; this in itself could lead to neurodegeneration through MT disassembly and impaired axonal transport.

Conclusions

Mutations in the MAPT gene can exert several different effects on the functions and properties of tau. These effects can overlap or be completely distinct between mutations, but all result in formation of aggregated tau inclusions with neuronal loss and atrophy. Mutations that affect tau mRNA splicing can alter the ratio of tau isoforms and lead to potential dysregulation of MT dynamics as well as an isoform specific overabundance of soluble, free-floating tau. Mutations that functionally affect tau’s ability to bind to, promote the assembly of, or stabilize MTs may also lead to neurodegeneration in a similar manner: through dysregulation of MT dynamics and/or tau mislocalization, leading to an increase in MT-unattached tau. In both of these instances, this increased amount of unbound tau could increase the usually-minute chance of nucleation events occurring, or these proteins could interact with polyanionic molecules in the cytosol, leading to an eventual cascade of elongation and seeding. For other mutations that increase aggregation propensity and/or seeding, perhaps they function under a similar mechanism, but with a higher susceptibility to β-sheet formation and aggregation, speeding up the pathological process. Importantly, impaired MT function and aberrant tau aggregation are not mutually exclusive pathogenic mechanisms. However, it is noteworthy that the observed differences in seeding propensities between different tau mutants does not correlate with an earlier age of onset or shorter duration of disease(12,116), suggesting that tau loss of function, such as impacts on MT activities or perhaps some still undiscovered function of tau, could be more important for pathogenesis than a relative increase in aberrant aggregation propensity.

Given the wide-ranging and unique differences between tau mutants, the choice of models used is an important one. The question remains, however, as to whether utilizing specific tau mutants- namely those at the P301 residue- in the context of aggregation and seeding studies constitutes a model mechanistically similar and applicable to other mutations in FTD and/or sporadic tauopathy; an important fact to consider when utilizing these models to demonstrate therapeutic efficacy.

Brain inclusions of the microtubule-associated protein tau are prominent pathological features in a spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases. MAPT gene mutations that encodes tau can directly cause neurodegeneration. Herein, the authors review what is known about MAPT mutations dysfunctions with a focus on the prion-like properties of tau protein.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS089022) and the Florida Department of Health (7AZ25).

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the content of this article.

References

- 1.Arendt T, Stieler JT, Holzer M. Tau and tauopathies. Brain Res Bull 2016;126:238–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Couchie D, Mavilia C, Georgieff IS, Liem RK, Shelanski ML, Nunez J. Primary structure of high molecular weight tau present in the peripheral nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1992;89:4378–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caillet-Boudin M-L, Buée L, Sergeant N, Lefebvre B. Regulation of human MAPT gene expression. Mol Neurodegener 2015;10:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, Cobb MH, Kirschner MW. Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Mol Biol Cell 1992;3:1141–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo T, Noble W, Hanger DP. Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol 2017;133:665–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW. A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1975;72:1858–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986;83:4913–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, et al. Association of missense and 5’-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 1998;393:702–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, et al. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol 1998;43:815–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1998;95:7737–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghetti B, Oblak AL, Boeve BF, Johnson KA, Dickerson BC, Goedert M. Invited review: Frontotemporal dementia caused by microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) mutations: A chameleon for neuropathology and neuroimaging. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2015;41:24–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reed LA, Wszolek ZK, Hutton M. Phenotypic correlations in FTDP-17. Neurobiol Aging 2001;22:89–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poorkaj P, Muma NA, Zhukareva V, Cochran EJ, Shannon KM, Hurtig H, et al. An R5L τ mutation in a subject with a progressive supranuclear palsy phenotype. Ann Neurol 2002;52:511–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kouri N, Carlomagno Y, Baker M, Liesinger AM, Caselli RJ, Wszolek ZK, et al. Novel mutation in MAPT exon 13 (p.N410H) causes corticobasal degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:271–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizzini C, Goedert M, Hodges JR, Smith MJ, Jakes R, Hills R, et al. Tau gene mutation K257T causes a tauopathy similar to Pick’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2000;59:990–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrest SL, Kril JJ, Stevens CH, Kwok JB, Hallupp M, Kim WS, et al. Retiring the term FTDP-17 as MAPT mutations are genetic forms of sporadic frontotemporal tauopathies. Brain 2017;141:521–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coppola G, Chinnathambi S, Lee JJY, Dombroski BA, Baker MC, Soto-ortolaza AI, et al. Evidence for a role of the rare p.A152T variant in mapt in increasing the risk for FTD-spectrum and Alzheimer’s diseases. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:3500–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Gong C-X. Tau exon 10 alternative splicing and tauopathies. Mol Neurodegener 2008;3:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosik KS, Orecchio LD, Bakalis S, Neve RL. Developmentally regulated expression of specific tau sequences. Neuron 1989;2:1389–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 1989;3:519–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Majounie E, Cross W, Newsway V, Dillman A, Vandrovcova J, Morris CM, et al. Variation in tau isoform expression in different brain regions and disease states. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:1922.e7–1922.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goedert M, Jakes R. Expression of separate isoforms of human tau protein: correlation with the tau pattern in brain and effects on tubulin polymerization. EMBO J 1990;9:4225–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goode BL, Chau M, Denis PE, Feinstein SC. Structural and functional differences between 3-repeat and 4-repeat tau isoforms: Implications for normal tau function and the onset of neurodegenerative disease. J Biol Chem 2000;275:38182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu M, Kosik KS. Competition for microtubule-binding with dual expression of tau missense and splice isoforms. Mol Biol Cell 2001;12:171–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niblock M, Gallo J. Tau alternative splicing in familial and sporadic tauopathies. Biochem Soc Trans 2012;40:677–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derisbourg M, Leghay C, Chiappetta G, Fernandez-Gomez FJ, Laurent C, Demeyer D, et al. Role of the Tau N-terminal region in microtubule stabilization revealed by new endogenous truncated forms. Sci Rep 2015;5:9659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu C, Song X, Nisbet R, Götz J. Co-immunoprecipitation with Tau isoform-specific antibodies reveals distinct protein interactions and highlights a putative role for 2N Tau in disease. J Biol Chem 2016;291:8173–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trabzuni D, Wray S, Vandrovcova J, Ramasamy A, Walker R, Smith C, et al. MAPT expression and splicing is differentially regulated by brain region: Relation to genotype and implication for tauopathies. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21:4094–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian W, Liu F. Regulation of alternative splicing of tau exon 10. Neurosci. Bull. 2014;30;367–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Souza I, Schellenberg GD. Determinants of 4-repeat tau expression. Coordination between enhancing and inhibitory splicing sequences for exon 10 inclusion. J Biol Chem 2000;275:17700–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pittman AM, Myers AJ, Duckworth J, Bryden L, Hanson M, Abou-Sleiman P, et al. The structure of the tau haplotype in controls and in progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum Mol Genet 2004;13:1267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pittman AM, Fung HC, de Silva R. Untangling the tau gene association with neurodegenerative disorders. Hum Mol Genet 2006;15:188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kouri N, Ross OA, Dombroski B, Younkin CS, Serie DJ, Soto-Ortolaza A, et al. Genome-wide association study of corticobasal degeneration identifies risk variants shared with progressive supranuclear palsy. Nat Commun 2015;6:7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers AJ, Pittman AM, Zhao AS, Rohrer K, Kaleem M, Marlowe L, et al. The MAPT H1c risk haplotype is associated with increased expression of tau and especially of 4 repeat containing transcripts. Neurobiol Dis 2007;25:561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mukrasch MD, Bibow S, Korukottu J, Jeganathan S, Biernat J, Griesinger C, et al. Structural polymorphism of 441-residue Tau at single residue resolution. PLoS Biol 2009;7:0399–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avila J, Jiménez JS, Sayas CL, Bolós M, Zabala JC, Rivas G, et al. Tau Structures. Front Aging Neurosci 2016;8:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeganathan S, Von Bergen M, Brutlach H, Steinhoff HJ, Mandelkow E. Global hairpin folding of tau in solution. Biochemistry 2006;45:2283–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wischik CM, Novak M, Thøgersen HC, Edwards PC, Runswick MJ, Jakes R, et al. Isolation of a fragment of tau derived from the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988;85:4506–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ganguly P, Do TD, Larini L, Lapointe NE, Sercel AJ, Shade MF, et al. Tau assembly: The dominant role of PHF6 (VQIVYK) in microtubule binding region repeat R3. J Phys Chem B 2015;119:4582–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smit FX, Luiken JA, Bolhuis PG. Primary Fibril Nucleation of Aggregation Prone Tau Fragments PHF6 and PHF6. J Phys Chem B 2017;121:3250–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Bergen M, Friedhoff P, Biernat J, Heberle J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Assembly of tau protein into Alzheimer paired helical filaments depends on a local sequence motif ((306)VQIVYK(311)) forming beta structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97:5129–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, et al. Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2017;547:185–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Falcon B, Zhang W, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Vidal R, et al. Structures of filaments from Pick’s disease reveal a novel tau protein fold. Nature 2018;561:137–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Bergen M, Barghorn S, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Tau aggregation is driven by a transition from random coil to beta sheet structure. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis 2005;1739:158–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friedhoff P, von Bergen M, Mandelkow EM, Davies P, Mandelkow E. A nucleated assembly mechanism of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998;95:15712–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barghorn S, Mandelkow E. Toward a unified scheme for the aggregation of tau into Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Biochemistry 2002;41:14885–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shammas SL, Garcia GA, Kumar S, Kjaergaard M, Horrocks MH, Shivji N, et al. A mechanistic model of tau amyloid aggregation based on direct observation of oligomers. Nat Commun 2015;6:7025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wegmann S, Eftekharzadeh B, Tepper K, Zoltowska KM, Bennett RE, Dujardin S, et al. Tau protein liquid–liquid phase separation can initiate tau aggregation. EMBO J 2018;e98049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goedert M, Masuda-Suzukake M, Falcon B. Like prions: The propagation of aggregated tau and α-synuclein in neurodegeneration. Brain 2017;140:266–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prusiner S Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 1982;216:136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braak H, Braak E. Staging of alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging 1995;16:271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ayers JI, Giasson BI, Borchelt DR. Prion-like Spreading in Tauopathies. Biol Psychiatry 2018;83:337–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Mandelkow E. Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015;17:22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirokawa N, Funakoshi T, Sato-Harada R, Kanai Y. Selective stabilization of tau in axons and microtubule-associated protein 2C in cell bodies and dendrites contributes to polarized localization of cytoskeletal proteins in mature neurons. J Cell Biol 1996;132:667–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoover BR, Reed MN, Su J, Penrod RD, Kotilinek LA, Grant MK, et al. Tau Mislocalization to Dendritic Spines Mediates Synaptic Dysfunction Independently of Neurodegeneration. Neuron 2010;68:1067–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu C, Götz J. Profiling murine tau with 0N, 1N and 2N isoform-specific antibodies in brain and peripheral organs reveals distinct subcellular localization, with the 1N isoform being enriched in the nucleus. PLoS One 2013;8:e84849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stamer K, Vogel R, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Tau blocks traffic of organelles, neurofilaments, and APP vesicles in neurons and enhances oxidative stress. J Cell Biol 2002;156:1051–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caceres A, Kosik KS. Inhibition of neurite polarity by tau antisense oligonucleotides in primary cerebellar neurons. Nature 1990;343:461–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hong X-P, Peng C-X, Wei W, Tian Q, Liu Y-H, Yao X-Q, et al. Essential role of tau phosphorylation in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampus 2010;20:1339–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura T, Whitcomb DJ, Jo J, Regan P, Piers T, Heo S, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau is essential for long-term depression in the hippocampus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2014;369:20130144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hirokawa N, Shiomura Y, Okabe S. Tau proteins: the molecular structure and mode of binding on microtubules. J Cell Biol 1988;107:1449–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brandt R, Léger J, Lee G. Interaction of tau with the neural plasma membrane mediated by tau’s amino-terminal projection domain. J Cell Biol 1995;131:1327–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Magnani E, Fan J, Gasparini L, Golding M, Williams M, Schiavo G, et al. Interaction of tau protein with the dynactin complex. EMBO J 2007;26:4546–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kadavath H, Hofele RV, Biernat J, Kumar S, Tepper K, Urlaub H, et al. Tau stabilizes microtubules by binding at the interface between tubulin heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:7501–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thies E, Mandelkow E-M. Missorting of tau in neurons causes degeneration of synapses that can be rescued by the kinase MARK2/Par-1. J Neurosci 2007;27:2896–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Despres C, Byrne C, Qi H, Cantrelle F-X, Huvent I, Chambraud B, et al. Identification of the Tau phosphorylation pattern that drives its aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:9080–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alonso ADC, Mederlyova A, Novak M, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Promotion of hyperphosphorylation by frontotemporal dementia tau mutations. J Biol Chem 2004;279:34873–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Min SW, Chen X, Tracy TE, Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang C, et al. Critical role of acetylation in tau-mediated neurodegeneration and cognitive deficits. Nat Med 2015;21:1154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Irwin DJ, Cohen TJ, Grossman M, Arnold SE, McCarty-Wood E, Van Deerlin VM, et al. Acetylated tau neuropathology in sporadic and hereditary tauopathies. Am J Pathol 2013;183:344–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martin L, Latypova X, Terro F. Post-translational modifications of tau protein: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int 2011;58:458–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee S, Shea TB. Caspase-mediated truncation of Tau potentiates aggregation. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2012;2012:731063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kondo A, Shahpasand K, Mannix R, Qiu J, Moncaster J, Chen CH, et al. Antibody against early driver of neurodegeneration cis P-tau blocks brain injury and tauopathy. Nature 2015;523:431–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang JZ, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Glycosylation of microtubule-associated protein tau: An abnormal posttranslational modification in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 1996;2:871–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Funk KE, Thomas SN, Schafer KN, Cooper GL, Clark DJ, Yang AJ, et al. Lysine methylation is an endogenous post-translational modification of tau protein in human brain and a modulator of aggregation propensity. Biochem J 2015;462:77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Crowtherp RA, Vanmechelen E, Probst A, et al. Molecular dissection of the paired helical filament. Neurobiol Aging 1995;16:325–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dickson DW, Kouri N, Murray ME, Josephs KA. Neuropathology of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration-Tau (FTLD-Tau). J Mol Neurosci 2012;45:384–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.D’Souza I, Schellenberg GD. Regulation of tau isoform expression and dementia. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis 2005;1739:104–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stoothoff W, Jones PB, Spires-Jones TL, Joyner D, Chhabra E, Bercury K, et al. Differential effect of three-repeat and four-repeat tau on mitochondrial axonal transport. J Neurochem 2009;111:417–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Swieten JC, Bronner IF, Azmani A, Severijnen L-A, Kamphorst W, Ravid R, et al. The ΔK280 Mutation in MAP tau Favors Exon 10 Skipping In Vivo. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2007;66:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ogaki K, Li Y, Takanashi M, Ishikawa KI, Kobayashi T, Nonaka T, et al. Analyses of the MAPT, PGRN, and C9orf72 mutations in Japanese patients with FTLD, PSP, and CBS. Park Relat Disord 2013;19:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Panda D, Samuel JC, Massie M, Feinstein SC, Wilson L. Differential regulation of microtubule dynamics by three- and four-repeat tau: Implications for the onset of neurodegenerative disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:9548–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pickering-Brown SM, Baker M, Nonaka T, Ikeda K, Sharma S, Mackenzie J, et al. Frontotemporal dementia with Pick-type histology associated with Q336R mutation in the tau gene. Brain 2004;127:1415–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tacik P, DeTure M, Hinkle KM, Lin WL, Sanchez-Contreras M, Carlomagno Y, et al. A novel Tau Mutation in exon 12, P. Q336H, causes hereditary pick disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2015;74:1042–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.D’Souza I, Poorkaj P, Hong M, Nochlin D, Lee VM-Y, Bird TD, et al. Missense and silent tau gene mutations cause frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism-chromosome 17 type, by affecting multiple alternative RNA splicing regulatory elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:5598–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goedert M, Jakes R, Spillantini MG, Hasegawa M, Smith MJ, Crowther RA. Assembly of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like filaments induced by sulphated glycosaminoglycans. Nature 19996;383:550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dinkel PD, Holden MR, Matin N, Margittai M. RNA binds to tau fibrils and sustains template-assisted growth. Biochemistry 2015;54:4731–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kampers T, Friedhoff P, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. RNA stimulates aggregation of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments. FEBS Lett 1996;399:344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frost B, Jacks RL, Diamond MI. Propagation of tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. J Biol Chem 2009;284:12845–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nonaka T, Watanabe ST, Iwatsubo T, Hasegawa M. Seeded aggregation and toxicity of α-synuclein and tau: Cellular models of neurodegenerative diseases. J Biol Chem 2010;285:34885–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kfoury N, Holmes BB, Jiang H, Holtzman DM, Diamond MI. Trans-cellular propagation of Tau aggregation by fibrillar species. J Biol Chem 2012;287:19440–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holmes BB, Furman JL, Mahan TE, Yamasaki TR, Mirbaha H, Eades WC, et al. Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:E4376–4385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sanders DW, Kaufman SK, DeVos SL, Sharma AM, Mirbaha H, Li A, et al. Distinct tau prion strains propagate in cells and mice and define different tauopathies. Neuron 2014;82:1271–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guo JL, Lee VMY. Neurofibrillary tangle-like tau pathology induced by synthetic tau fibrils in primary neurons over-expressing mutant tau. FEBS Lett 2013;587:717–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Falcon B, Cavallini A, Angers R, Glover S, Murray TK, Barnham L, et al. Conformation determines the seeding potencies of native and recombinant Tau aggregates. J Biol Chem 2015;290:1049–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Waxman EA, Giasson BI. Induction of intracellular tau aggregation is promoted by α-synuclein seeds and provides novel insights into the hyperphosphorylation of tau. J Neurosci 2011;31:7604–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Guo JL, Lee VMY. Seeding of normal tau by pathological tau conformers drives pathogenesis of Alzheimer-like tangles. J Biol Chem 2011;286:15317–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, et al. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat Cell Biol 2009;11:909–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Boluda S, Iba M, Zhang B, Raible KM, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Differential induction and spread of tau pathology in young PS19 tau transgenic mice following intracerebral injections of pathological tau from Alzheimer’s disease or corticobasal degeneration brains. Acta Neuropathol 2015;129:221–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ahmed Z, Cooper J, Murray TK, Garn K, McNaughton E, Clarke H, et al. A novel in vivo model of tau propagation with rapid and progressive neurofibrillary tangle pathology: The pattern of spread is determined by connectivity, not proximity. Acta Neuropathol 2014;127:667–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jackson SJ, Kerridge C, Cooper J, Cavallini A, Falcon B, Cella C V, et al. Short fibrils constitute the major species of seed-competent tau in the brains of mice transgenic for human P301S tau. J Neurosci 2016;36:762–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kaufman SK, Sanders DW, Thomas TL, Ruchinskas AJ, Vaquer-Alicea J, Sharma AM, et al. Tau prion strains dictate patterns of cell pathology, progression rate, and regional vulnerability in vivo. Neuron 2016;92:796–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Iba M, Guo JL, McBride JD, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy. J Neurosci 2013;33:1024–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Peeraer E, Bottelbergs A, Van Kolen K, Stancu IC, Vasconcelos B, Mahieu M, et al. Intracerebral injection of preformed synthetic tau fibrils initiates widespread tauopathy and neuronal loss in the brains of tau transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis 2015;73:83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chakrabarty P, Hudson VJ, Sacino AN, Brooks M, D’Alton S, Lewis J, et al. Inefficient induction and spread of seeded tau pathology in P301L mouse model tauopathy suggest inherent physiological barriers to transmission. Acta Neuropathol 2015;130:303–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stancu IC, Vasconcelos B, Ris L, Wang P, Villers A, Peeraer E, et al. Templated misfolding of Tau by prion-like seeding along neuronal connections impairs neuronal network function and associated behavioral outcomes in Tau transgenic mice. Acta Neuropathol 2015;129:875–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vasconcelos B, Stancu IC, Buist A, Bird M, Wang P, Vanoosthuyse A, et al. Heterotypic seeding of Tau fibrillization by pre-aggregated Abeta provides potent seeds for prion-like seeding and propagation of Tau-pathology in vivo. Acta Neuropathol 2016;131:549–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Clavaguera F, Akatsu H, Fraser G, Crowther RA, Frank S, Hench J, et al. Brain homogenates from human tauopathies induce tau inclusions in mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:9535–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Adams SJ, de Ture MA, McBride M, Dickson DW, Petrucelli L. Three repeat isoforms of tau inhibit assembly of four repeat tau filaments. PLoS One 2010;5:e10810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Strang KH, Croft CL, Sorrentino ZA, Chakrabarty P, Golde TE, Giasson BI. Distinct differences in prion-like seeding and aggregation between tau protein variants provide mechanistic insights into tauopathies. J Biol Chem 2017;293:2408–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Siddiqua A, Luo Y, Meyer V, Swanson MA, Yu X, Wei G, et al. Conformational basis for asymmetric seeding barrier in filaments of three- and four-repeat tau. J Am Chem Soc 2012;134:10271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Woerman AL, Aoyagi A, Patel S, Kazmi SA, Lobach I, Grinberg LT, et al. Tau prions from Alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy patients propagate in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2016;113:E8187–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Combs B, Gamblin TC. FTDP-17 tau mutations induce distinct effects on aggregation and microtubule interactions. Biochemistry 2012;51:8597–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Verheyen A, Diels A, Dijkmans J, Oyelami T, Meneghello G, Mertens L, et al. Using human iPSC-derived neurons to model TAU aggregation. PLoS One 2015;10:e0146127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Monsellier E, Chiti F. Prevention of amyloid-like aggregation as a driving force of protein evolution. EMBO Rep 2007;8:737–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bardai FH, Wang L, Mutreja Y, Yenjerla M, Gamblin TC, Feany MB. A conserved cytoskeletal signaling cascade mediates neurotoxicity of FTDP-17 tau mutations in vivo. J Neurosci 2017;38:1550–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rosso SM, Van Herpen E, Deelen W, Kamphorst W, Severijnen LA, Willemsen R, et al. A novel tau mutation, S320F, causes a tauopathy with inclusions similar to those in Pick’s disease. Ann Neurol 2002;51:373–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jeganathan S, Hascher A, Chinnathambi S, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Proline-directed pseudo-phosphorylation at AT8 and PHF1 epitopes induces a compaction of the paperclip folding of tau and generates a pathological (MC-1) conformation. J Biol Chem 2008;283:32066–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1992;42:631–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lin WL, Lewis J, Yen SH, Hutton M, Dickson DW. Ultrastructural neuronal pathology in transgenic mice expressing mutant (P301L) human tau. J Neurocytol 2003;32:1091–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Millecamps S, Julien J-P, Pierre U. Axonal transport deficits and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:161–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gómez-Isla T, Hollister R, West H, Mui S, Growdon JH, Petersen RC, et al. Neuronal loss correlates with but exceeds neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 1997;41:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Andorfer C Cell-cycle reentry and cell death in transgenic mice expressing nonmutant human tau isoforms. J Neurosci 2005;25:5446–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Spires-Jones TL, de Calignon A, Matsui T, Zehr C, Pitstick R, Wu H-Y, et al. In vivo imaging reveals dissociation between caspase activation and acute neuronal death in tangle-bearing neurons. J Neurosci 2008;28:862–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gerson J, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Bodani R, Prough DS, DeWitt DS, et al. Tau oligomers derived from traumatic brain injury cause cognitive impairment and accelerate onset of pathology in Htau mice. J Neurotrauma 2016;33:2034–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Flach K, Hilbrich I, Schiffmann A, Gärtner U, Krüger M, Leonhardt M, et al. Tau oligomers impair artificial membrane integrity and cellular viability. J Biol Chem 2012;287:43223–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hayashi S, Toyoshima Y, Hasegawa M, Umeda Y, Wakabayashi K, Tokiguchi S, et al. Late-onset frontotemporal dementia with a novel exon 1 (Arg5His) tau gene mutation. Ann Neurol 2002;51:525–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chang E, Kim S, Yin H, Nagaraja HN, Kuret J. Pathogenic missense MAPT mutations differentially modulate tau aggregation propensity at nucleation and extension steps. J Neurochem 2008;107:1113–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Iyer A, LaPointe NE, Zielke K, Berdynski M, Guzman E, Barczak A, et al. A novel MAPT mutation, G55R, in a frontotemporal dementia patient leads to altered tau function. PLoS One 2013;8:e76409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Silva MC, Cheng C, Mair W, Almeida S, Fong H, Biswas MHU, et al. Human iPSC-derived neuronal model of Tau-A152T frontotemporal dementia reveals tau-mediated mechanisms of neuronal vulnerability. Stem Cell Reports 2016;7:325–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kara E, Ling H, Pittman AM, Shaw K, de Silva R, Simone R, et al. The MAPT p.A152T variant is a risk factor associated with tauopathies with atypical clinical and neuropathological features. Neurobiol Aging 2012;33:2231.e7–2231.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Grover A, England E, Baker M, Sahara N, Adamson J, Granger B, et al. A novel tau mutation in exon 9 (I260V) causes a four-repeat tauopathy. Exp Neurol 2003;184:131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]