Abstract

Amyloid beta peptide (Aβ42) aggregation in the brain is thought to be responsible for the onset of Alzheimer's disease, an insidious condition without an effective treatment or cure. Hence, a strategy to prevent aggregation and subsequent toxicity is crucial. Bio-inspired peptide-based molecules are ideal candidates for the inhibition of Aβ42 aggregation, and are currently deemed to be a promising option for drug design. In this study, a hexapeptide containing a self-recognition component unique to Aβ42 was designed to mimic the β-strand hydrophobic core region of the Aβ peptide. The peptide is comprised exclusively of D-amino acids to enhance specificity towards Aβ42, in conjunction with a C-terminal disruption element to block the recruitment of Aβ42 monomers on to fibrils. The peptide was rationally designed to exploit the synergy between the recognition and disruption components, and incorporates features such as hydrophobicity, β-sheet propensity, and charge, that all play a critical role in the aggregation process. Fluorescence assays, native ion-mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) and cell viability assays were used to demonstrate that the peptide interacts with Aβ42 monomers and oligomers with high specificity, leading to almost complete inhibition of fibril formation, with essentially no cytotoxic effects. These data define the peptide-based inhibitor as a potentially potent anti-amyloid drug candidate for this hitherto incurable disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid fibrils, D-amino acids, peptide-based inhibitor, protein aggregation

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of neurodegenerative disorder amongst the elderly, [1] leading to neuronal cell death and loss of cognitive function. It is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disease without a known cure, [2,3] with current drugs providing only marginal symptomatic relief. [4,5] While the exact cause of AD remains unclear, the major pathological hallmarks are neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques in the brain. [6] Extracellular amyloid plaques are dense, insoluble aggregates containing the Aβ peptide, which in the brain are produced primarily by neurons. [7] Aβ is a short peptide, with the most common alloforms being either 40 or 42 residues in length, [8] and is formed via proteolysis of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases. [9,10] While Aβ40 is the more abundant amyloid peptide in vivo, Aβ42 is more neurotoxic and is responsible for peptide aggregation and fibrilization. [11] The aggregation of Aβ42 peptide monomers to potentially neurotoxic oligomers and fibrils is believed to be a cause of AD, [12,13] however the precise relationship between size, structure and toxicity of Aβ42 oligomers remains elusive. [14,15] The soluble monomeric form of Aβ42 has recently been found to have possible additional physiological functions, [16] so the pursuit of drugs such as secretase inhibitors may not be prudent at this point in time. Hence, the inhibition of Aβ aggregation seems a more appropriate strategy.[17] The design of small molecular inhibitors to interfere with such protein-protein interactions is somewhat challenging, with the majority of those compounds currently undergoing clinical trials being non-selective and binding to Aβ42 with low affinity. [12] Peptide-based molecules are ideal candidates for the inhibition of Aβ aggregation, insofar as they can be specifically modified to increase affinity and specificity, [12] with bio-inspired peptides currently considered to be the most promising option for drug design. [18–20] A rational approach for the design of peptide-based inhibitors expressly for Aβ42 aggregation is to target the site where fibrilization is thought to occur, focusing on high specificity and affinity. [12] One of the sites known to be responsible for Aβ fibril formation is the hydrophobic core region of Aβ42, the self-recognition ‘nucleation site’, KLVFF (16–20 residue region). [21,22] A synthetic peptide fragment comprising this amino acid sequence is believed to bind to the corresponding region of the native peptide via hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding, providing minor inhibition of Aβ42 aggregation. [23]

Studies have shown that Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils contain a β-sheet structure, with the KLVFF region crucial in this regard. [24–28] It has been suggested that a conformational change to a β-sheet geometry is the first step in the aggregation process. [29] Recently, cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) have revealed a detailed characterization of Aβ42 monomers within the fibrils with near-atomic resolution. [30–32] These particular studies reveal that each amyloid polymorph results from the dimerization of two individual Aβ42 molecules, with the stacking of identical monomer pairs above and below via hydrogen bonding to form oligomers. [33] In each of these defined polymorphs, a β-strand (16–20) region is evident in both monomers, with residues exposed on the exterior surface, forming the main turn between three major β-strands. These intramolecular β-strands, together with other critical interactions, such as a salt bridge between K28 and A42, help constrain the monomer into a compact S (or LS)-shaped amyloid fold, [30,34] as depicted in Figure 1A. A slight protrusion is evident in the structure towards the end of this particular β-strand, in the vicinity of hydrophilic residues E22 and D23, where several mutations are associated with the onset of Alzheimer's disease, [35] which may provide some insights into the origins of Aβ42 toxicity. Hence, these three-dimensional structures provide an excellent foundation for the rational design of inhibitors that can bind to a specific, accessible location on the monomer/fibril surface to prevent Aβ42 aggregation.

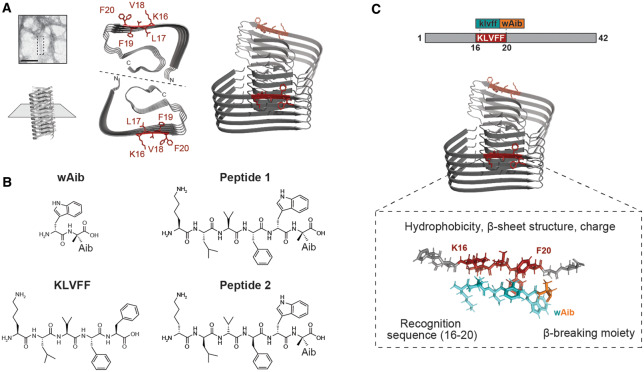

Figure 1. High-resolution cryo-EM reconstruction of Aβ42 fibrils, and synthesized peptides used in this study.

(A) Cryo-EM reconstruction of full-length Aβ42 fibrils (pdb entry: 5oqv) [32] shows that residues 16–20 (red) are central to a parallel β-sheet region, identified on the exterior surface of the fibrils in several Aβ42 polymorphs. Residue F20 has been shown to occupy two distinct orientations on the fibril surface (fibril axis indicated by dashed line). (B) Structures of control peptides wAib and KLVFF. The rationally designed β-strand peptides 1 (L-isoform) and 2 (D-isoform) were assessed to determine their ability to prevent Aβ42 fibril formation. (C) Design strategy of peptide inhibitors (peptide 2 in this instance) consisting of the recognition sequence (blue) which targets residues 16–20 (red) of Aβ42, and the wAib β-breaker moiety (orange) to prevent fibril formation.

Numerous derivatives of KLVFF have been developed to improve inhibitory effects, [36–42] with only pentapeptides or longer showing significant binding to the amyloid peptide. [43] A previous study based on the KLVFF motif, found that peptides containing D-amino acids were more active inhibitors of Aβ than their L-counterparts. [44] The D-amino acid peptide fragment, klvff, has a modest inhibitory effect on Aβ42 aggregation, albeit superior to that of the L-enantiomer, KLVFF. [45] The use of D-amino acids offers advantages of increased metabolic stability and resistance to proteases, [46] decreased immunogenicity, [47] as well as an enhanced ability to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB). [48,49] Murphy and Kiessling were among the first to report incorporation of a ‘disruption element’ into peptides containing the KLVFF recognition element, which was shown to alter Aβ aggregation pathways. [50] Specifically, the recognition element facilitates the binding of the peptide-based inhibitor to the growing Aβ fibril or its precursor, while the disruption element is designed to hinder further propagation and reduce toxicity. [51,52] Peptides containing various ‘β-strand breakers’ acting as a disruption element have been shown to inhibit Aβ aggregation. [11,12] Proline residues were first used in this context, and exhibited a moderate inhibitory effect against Aβ42 when located in the centre of the peptide sequence in order to prevent the formation of a β-sheet structure. [53] The achiral, geminally disubstituted aminobutyric acid (Aib) residue has also found moderate success when used in this manner, [2,54,55] and possesses a much stronger β-strand breaking potential than proline. [56] The placement of a β-strand breaker residue in the centre of short peptide inhibitors based on the KLVFF recognition element is known to distort the β-strand conformation, [57] and is thus not structurally homologous to the Aβ oligomer/fibril binding site. [52] The Gazit group designed a novel oligomerization inhibitor comprising a dipeptide, with D-tryptophan (D-Trp) coupled to a C-terminal Aib β-breakage moiety. [56] They found that tryptophan demonstrated the highest amyloidogenic propensity of any amino acid, [2] with the indole moiety thought to interact with the aromatic rings of the phenylalanine residues located in the central hydrophobic core region of the amyloid peptide via π–π stacking, thus competing with Aβ monomers for interaction with the growing fibrils. [56] While the peptide exhibited good binding affinity for Aβ monomers, [58] it was designed to be non-specific in sequence, and has the capacity to inhibit the toxic aggregation of other amyloid peptides, including IAPP, α-synuclein, and calcitonin. [59] Studies have shown that peptides with a high affinity for Aβ are better inhibitors of Aβ fibrilization, [60] but peptide-based inhibitors designed expressly for Aβ42 aggregation also require high specificity. Hence, retention of the β-strand geometry of the peptide-based inhibitor for binding specificity is crucial, as is judicious placement of the disruption domain. Although a KLVFF fragment has been shown to inhibit Aβ42 aggregation to a small degree, [23] it has a tendency to self-aggregate, which is not a desirable property for an effective inhibitor [61].

With the aforementioned in mind, we present a specific Aβ42 inhibitor (see peptide 2 in Figure 1) based on the KLVFF recognition site of Aβ42 (residues 16–20), that does not self-aggregate. The peptide comprises all D-amino acids, coupled to a C-terminal Aib ‘β-breakage’ moiety, to exploit the synergy between the recognition and disruption components. The peptide was rationally designed to incorporate features such as hydrophobicity, β-sheet propensity, and charge, in order to increase affinity and specificity, and provide a robust interconnection with Aβ42, as all three elements play a critical role in the aggregation process. [46,62] Herein, we present structural studies of the peptide-based inhibitor and describe its effect on Aβ42 aggregation and toxicity.

Materials and methods

Peptide synthesis

Peptides 1 and 2 were synthesized using Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS). Fmoc-based SPPS and commercially available reagents were used for the synthesis of both peptides. 2-Chlorotrityl resin preloaded with Fmoc-Aib-OH (0.80 mmol g−1, 1.0 g, 1 equiv) was used for both peptides. The unreacted active sites on the resin were capped with DCM/MeOH/DIPEA (17:2:1, 2 × 25 ml) for 30 min and the resin washed with DCM (x3), DMF (x3) and DCM (x3). N-Fmoc deprotection was conducted by treating the resin with 25% piperidine/DMF (25 ml) for 30 min before washing with DCM (x3), DMF (x3) and DCM (x3). Each sequential amino acid was coupled using the following molar ratios of reagents: Fmoc-amino acids were each dissolved in DMF (20 ml), 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate (HATU)/DMF (0.5 M, 2 equiv) and DIPEA (4 equiv). The resin was then washed with DCM (x3) and DMF (x3) followed by DCM (x3), and the coupling procedures repeated. The coupling time was a minimum of 2 h in all cases. Fmoc-(D)-Trp-OH was next added to each peptide. Thereafter, Fmoc-(L)-Phe-OH, Fmoc-(L)-Val-OH, Fmoc-(L)-Leu-OH, and Fmoc-(L)-Lys(Boc)-OH were sequentially added to peptide 1, whereas all D-amino acids, Fmoc-(D)-Phe-OH, Fmoc-(D)-Val-OH, Fmoc-(D)-Leu-OH, and Fmoc-(D)-Lys(Boc)-OH were used to synthesize peptide 2. Following coupling with the final residue for each peptide, treatment with 1.5% TFA/DCM (15 ml) for 10 min resulted in cleavage from the resin. Peptides 1 and 2 were each dissolved in TFA/DCM (50% v/v) for 30 min to remove the Boc protecting group. Each peptide was placed under vacuum before being purified using reverse phase HPLC. KLVFF and wAib-OH (controls) were also synthesized using SPPS, and purified using reverse phase HPLC. Notably, a number of techniques including 1H NMR, were used to confirm that peptides 1 and 2 have been stable for more than two years.

1H NMR data for peptides

Peptide 1 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.79 (s, 1H, OH), 8.47 (d, 1H, NH Leu, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.30 (d, 1H, NH Trp, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.13–8.10 (m, 3H, NH Aib, NH2 terminal Lys), 7.93 (d, 1H, NH Val, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.87 (d, 1H, NH Phe, J = 7.7 Hz), 7.75 (br s, 1H, NH indole), 7.66 (d, 1H, ArH, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.30 (d, 1H, ArH, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.12 (d, 1H, ArH, J = 2.1 Hz), 7.10–7.04 (m, 4H, ArH), 6.98 (t, 1H, ArH, J = 7.5 Hz), 6.94 (d, 2H, ArH, J = 7.1 Hz), 4.54–4.49 (m, 2H, CαH Phe, CαH Trp), 4.40 (m, 1H, CαH Leu), 4.08 (m, 1H, CαH Val), 3.76 (m, 1H, CαH Lys), 3.12 (m, 1H, CαH (Trp) CHH), 2.84 (m, 1H, CαH (Trp) CHH), 2.70 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 2.65 (m, 1H, CαH (Phe) CHH), 2.51 (m, 1H, CαH (Phe) CHH), 1.88 (m, 1H, CαH (Val) CH), 1.68–1.62 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.58 (m, 1H, CαH (Leu) CH2CH), 1.51–1.46 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.40–1.34 (m, 2H, CαH (Leu) CH2CH), 1.37 (s, 3H, Aib CH3), 1.32 (s, 3H, Aib CH3), 1.30–1.27 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 0.87–0.82 (m, 6H, (Leu) 2 × CH3), 0.75–0.73 (m, 6H, (Val) 2 × CH3).

HRMS [M + H]+ calc'd = 777.4663, [M + H]+ found = 777.4674 (Supplementary Figure S11).

Peptide 2 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.80 (s, 1H, OH), 8.47 (d, 1H, NH Leu, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.07 (s, 1H, NH Aib), 8.05 (d, 1H, NH Trp, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.99 (d, 1H, NH Val, J = 9.1 Hz), 7.95 (d, 1H, NH Phe, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.73 (br s, 1H, NH indole), 7.57 (d, 1H, ArH, J = 7.9 Hz), 7.31 (d, 1H, ArH, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.21–7.12 (m, 6H, ArH), 7.05 (t, 1H, ArH, J = 7.1 Hz), 6.96 (d, 1H, ArH, J = 7.0 Hz), 4.57–4.52 (m, 2H, CαH Phe, CαH Trp), 4.40 (m, 1H, CαH Leu), 4.11 (m, 1H, CαH Val), 3.76 (t, 1H, CαH Lys, J = 6.2 Hz), 3.07 (m, 1H, CαH (Trp) CHH), 2.98–2.92 (m, 2H, CαH (Trp) CHH, CαH (Phe) CHH), 2.75 (m, 1H, CαH (Phe) CHH), 2.70 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.88 (m, 1H, CαH (Val) CH), 1.69–1.63 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.59 (m, 1H, CαH (Leu) CH2CH), 1.52–1.46 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.42 (m, 1H, CαH (Leu) CHHCH), 1.35 (m, 1H, CαH (Leu) CHHCH), 1.32 (s, 3H, Aib CH3), 1.31–1.23 (m, 2H, CαH (Lys) CH2CH2CH2CH2), 1.27 (s, 3H, Aib CH3), 0.88–0.83 (m, 6H, (Leu) 2 × CH3), 0.74–0.72 (m, 6H, (Val) 2 × CH3).

HRMS [M + H]+ calc'd = 777.4663, [M + H]+ found = 777.4706 (Supplementary Figure S12).

IR spectroscopy

Infrared spectra of peptides 1 and 2 (dried samples) were collected on a PerkinElmer Spectrum 100 FT-IR spectrometer, with attenuated total reflectance (ATR) imaging capabilities, fitted with a ZnSe crystal, with an average reading taken from four scans at 4 cm−1 resolution.

High-performance liquid chromatography

The synthetic peptides were analyzed and purified by reverse phase HPLC, using a Gilson GX-271 preparative system equipped with Trilution LC 2.1 software, with a Supelco C18 column (250 × 10 mm) at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1. ACN/TFA (100/0.0008 by v/v) and water/TFA (100/0.001 by v/v) solutions were used as organic and aqueous buffers, respectively.

High resolution mass spectroscopy

High resolution mass spectral data were analyzed using an Ultimate 3000 RSL HPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA) and an LTQ Orbitrap XL ETD using a flow injection method, with a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The HPLC flow is interfaced with the mass spectrometer using the Electrospray source (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA). Mass spectra were obtained over a range of 100 < m/z < 1000. Data was analyzed using XCalibur software (Version 2.0.7, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Molecular modelling

The lowest-energy conformers for the peptides were determined in the gas phase by the NWChem 6.6 package [63] with tight convergence criteria using a hybrid B3LYP functional with 6–31G** basis set for all atoms. Conformational analysis, including dihedral angles, overall molecular lengths and intramolecular hydrogen bond lengths, were conducted using the Chimera 1.11software. [64]

Aβ42 aggregation assays

Monomerization of Aβ42 (Adelab Scientific) was prepared by NaOH treatment as described previously [65] whereas mature Aβ42 fibrils were prepared at 37°C for 24 h with shaking (50 rpm). The ability of various inhibitors to prevent Aβ42 fibril formation was assessed using an in situ thioflavin-T (ThT) (20 µM) assay. Non-monomerized Aβ42 (100 µM) was examined across a range of molar ratios (1 : 1, 1 : 2, 1 : 10 and 1 : 20) (Aβ42:inhibitor) in the absence and presence of inhibitors. Assays were performed in PBS (pH 7.4) and 1% DMSO at 35°C in quiescence. The ability of the inhibitors to prevent Aβ42 fibrilization was determined by comparing the ThT fluorescence at the conclusion of each assay. [66] The inhibition of primary-nucleation mediated Aβ42 aggregation was also monitored using an in situ ThT assay where monomerized Aβ42 (10 µM) was incubated in the absence and presence of inhibitors under conditions stated above at 25°C. All assays were performed using a FLUOstar Optima plate reader (BMG Lab Technologies) with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 440 nm and 490 nm, respectively. All assays were performed at least three times and data are reported as mean ± SEM of three independent assays.

Seeded α-synuclein (αS) aggregation assays

Plasmid (pT7–7, Addgene) encoding for wild-type (WT) human αS (SNCA, UniProt accession number: P37840) were kindly donated by Prof. Heath Ecroyd (University of Wollongong, Australia). Expression and purification of monomeric αS WT was performed as described previously. [67] Following purification, monomeric αS (50 µM in PBS) was heated and stirred at 45°C for 24 h prior to sonication. The ability of peptides 1 and 2 to prevent αS fibril formation was assessed using an αS elongation assay. [67] This assay measures the ability of the designed inhibitors to inhibit the elongation of αS fibrils using short pre-formed αS seed fibrils. Elongation of αS fibrils was monitored using an in situ ThT (20 µM) assay. Inhibitors were added at 1 : 1, 2 : 1 and 1 : 2 molar ratios (αS:inhibitor) to monomeric αS (50 µM) in PBS (pH 7.4) with 5% (w/w) αS seed fibrils. All assays were performed at least three times and data are reported as mean ± SEM of these independent assays.

TEM

The presence and morphology of Aβ42 fibrils were imaged by TEM where 2 μl aliquots from the end-point of ThT aggregation assays were adsorbed on to carbon-coated electron microscopy grids (SPI Supplies) and negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate. [68] Images were viewed using a Philips CM100 transmission electron microscope at 45 000× magnification.

Nile red assays

Nile red fluorescence was used to determine the relative amount of exposed hydrophobicity of Aβ42 fibrils and measured using a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian). Fibrils (10 µM in PBS, pH 7.4) in the presence and absence of inhibitors were labelled with Nile red (10 µM). Labelled samples were incubated for 5 min at room temperature prior to fluorescence measurement. The excitation wavelength was set at 595 nm and emission wavelength was recorded from 500–800 nm. The slit widths for excitation and emission spectra were both set at 5 nm.

Cell culture and cell viability assays

Mouse neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells were kindly donated by Dr. David Bersten (University of Adelaide, Australia) and grown in DMEM/F12 media containing 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. Cells were seeded at 3 × 104 cells/well in aforementioned media and equilibrated for 24 h prior to addition of pre-formed Aβ42 fibrils (50 µM) in the absence and presence of each inhibitor at a 1 : 2 (Aβ42 : inhibitor) molar ratio. Cells were then incubated for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere prior to cell viability measurement. The ability of the inhibitors to prevent cytotoxicity induced by the addition of exogenous Aβ42 fibrils was assessed using a thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Media was removed post-incubation and replaced with serum-free media containing MTT (0.25 mg/ml) and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. Media containing MTT was removed and cells were lysed with DMSO prior to absorbance measurement at 570 nm using a FLUOstar Optima plate reader (BMG Lab Technologies). Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8.0 (GraphPad).

Native ion mobility—mass spectrometry (IM-MS)

IM-MS was performed as described previously [68] on a Synapt G1 HDMS (Waters) with a nanoelectrospray source. Aβ42 (10 µM) was incubated in the absence and presence of peptide 1/2 at a 1 : 10 molar ratio (Aβ42 : peptide 1/2) in 200 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.8) and loaded onto platinum-coated borosilicate glass capillaries prepared in-house (Harvard Apparatus). To minimize gas-phase structural rearrangement the following instrument parameters were applied: capillary voltage, 1.65 kV; sample cone voltage, 20 V; source temperature, 25°C; trap collision energy, 10–20 V (5 V increments); transfer collision energy, 10 V; trap gas: 4.5 l/h; backing pressure, 4.0 mbar. IM cell instrument parameters: wave velocity: 300 m/s; transfer t-wave height: 6 V; transfer wave velocity: 250 m/s. Mass spectra and ATD data were analyzed using MassLynx (v4.1) and Driftscope (v2.7) respectively (Waters).

Results and discussion

Peptide design

Peptide 2 and its natural analogue 1 (Figure 1B) were designed specifically to inhibit the aggregation of Aβ42. The peptide sequence is based on the hydrophobic core, KLVFF recognition region of Aβ42, with the terminal phenylalanine residue of each replaced with D-Trp which is known to enhance amyloidogenicity, and with an appended C-terminal achiral Aib residue to act as a β-strand breaker. The peptides were designed to adopt a β-strand geometry and bind specifically to the KLVFF region of Aβ42 by virtue of their sequence homology, with the Aib residue proposed to interfere with the aggregation process.

As previously demonstrated, [27] a peptide-based inhibitor containing a preorganized β-strand conformation, facilitates binding to early β-structured oligomers to a greater extent than unstructured monomers bind oligomers. With respect to oligomeric amyloid structures, it has been proposed that a parallel β-sheet forms between neighboring Aβ42 monomers at the central 15–21 residue region. [40] An antiparallel β-sheet has also been suggested for the interaction between short inhibitory peptides containing D-amino acids and the all L-Aβ42, generating energetically favourable hydrogen bonding. [52] The C-terminal Aib residue is intended to sterically block hydrogen bonding between the β-sheets in either orientation, while also increasing the overall hydrophobicity of the peptide. An Aib moiety is known to promote helicity which then disrupts β-sheet formation, leading to inhibition of amyloid formation. [55] The mass of the peptide was restricted to 776 Da, without compromising functionality, since compounds with a mass in excess of 1000 Da are largely excluded from passing through the BBB. [69] Peptide fragments, KLVFF and D-Trp-Aib-OH (hereafter referred to as wAib, Figure 1B) were used as controls for the aggregation studies, as peptides 1 and 2 were both derived from the KLVFF region of Aβ42, and each contain an Aib residue coupled to a D-Trp at their C-termini.

Conformational analysis of peptides

The backbones of peptides 1 and 2 were shown to adopt a β-strand geometry by 1H NMR, IR and molecular modelling. Specifically, CαH (i) to NH (i + 1) and CβH2 (i) to NH (i + 1) ROESY interactions for residues 1–5 were observed (excluding Aib, see Supplementary Figures S1, S2). Four 3JNHCαH coupling constants between 7.7 Hz and 9.0 Hz were observed for peptide 1, while 3JNHCαH coupling constants between 8.0 Hz and 9.1 Hz were observed for residues 2–5 in peptide 2 (excluding Aib), in accordance with a β-strand conformation. [70] The IR spectrum of peptide 1 shows a strong Amide I band at 1637 cm−1, characteristic of a β-strand conformation, together with an Amide II band at 1550 cm−1 (N-H bending vibrations, parallel β-sheet), [71] and Amide A band at 3275 cm−1 (N-H stretching, Supplementary Figure S3). The IR spectrum for peptide 2 is also characteristic of a β-strand conformation, with a strong Amide I band at 1631 cm−1, and an Amide II band at 1525 cm−1, indicative of an antiparallel β-sheet (Supplementary Figure S4). [71] The lowest energy conformer for the D-peptide 2 was determined by density functional theory (DFT) calculations to further define the backbone geometry (see Materials and Methods section for details). The backbone dihedral angles for 2 indicate a β-strand geometry throughout the peptide, from D-Lys (1) to D-Trp (5), with the exception of the Aib residue (Supplementary Table S1). This result supports the IR and 1H NMR spectroscopic data, which also confirms an extended β-strand conformation, with the exception of the C-terminal Aib ‘β-breaker’ moiety. Furthermore, critical distances calculated for CαH (i) to NH (i + 1) and CβH2 (i) to NH (i + 1) are in accordance with a β-strand conformation (Supplementary Figures S5–S7 and Supplementary Table S2). [72]

Peptide 2 significantly inhibits Aβ42 fibril elongation

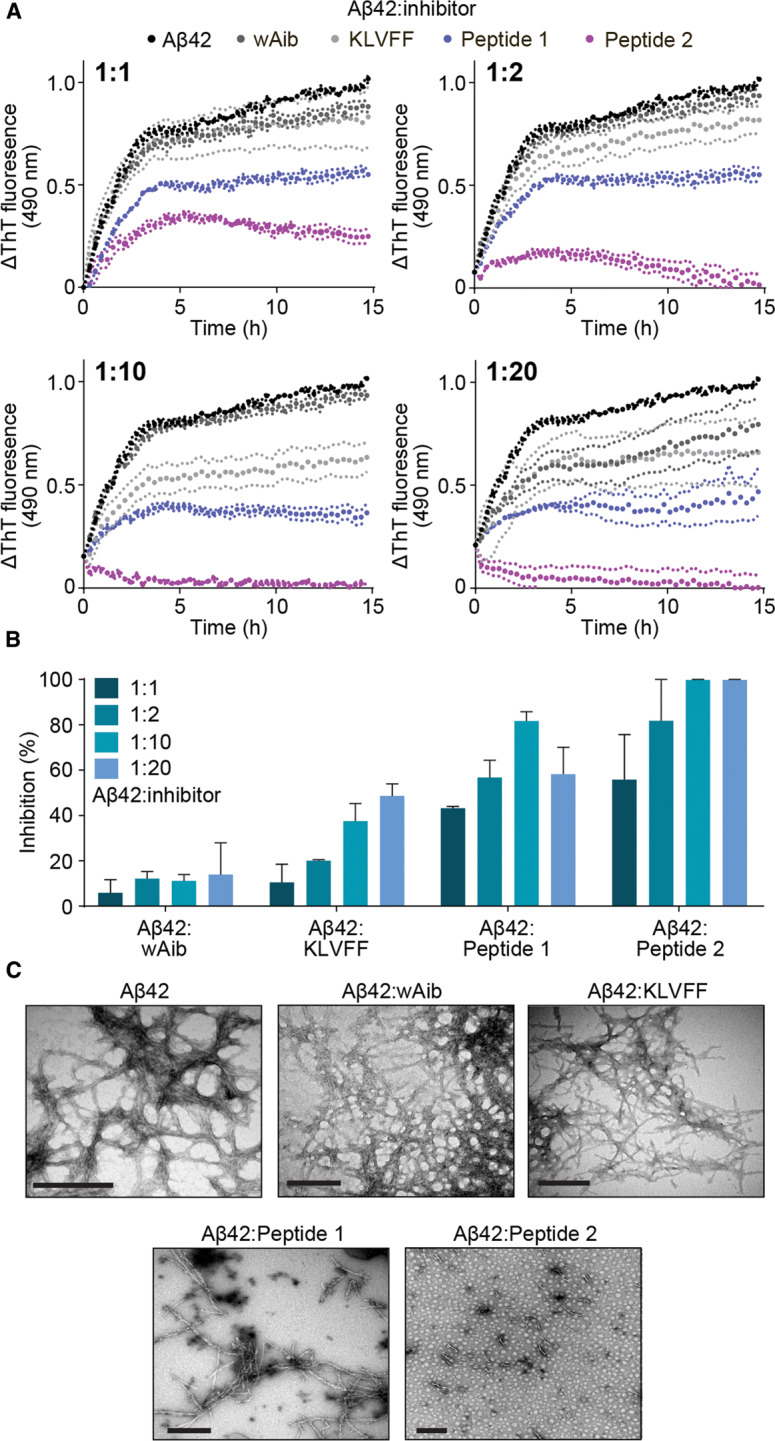

Peptides 1 and 2 were each tested for inhibition of Aβ42 elongation, with control peptides KLVFF and wAib used for comparison. The ability of the peptides to inhibit Aβ42 aggregation was assessed using an in vitro thioflavin-T (ThT) fluorescence assay (see Materials and Methods section for details), which exhibits increased fluorescence with the extent of cross β-sheet structure, characteristic of amyloid fibril formation. [38] In the absence of inhibitors, Aβ42 follows aggregation kinetics whereby fibril elongation begins immediately (i.e. seeding-like kinetics), reaching a plateau at ∼6 h (Figure 2A) likely due to the high concentration of Aβ42 (100 µM) as observed previously [73]. In the presence of wAib, no drastic change in ThT fluorescence was observed over time, until a 20-fold excess led to an observable decrease in fluorescence (Figure 2A; dark grey). In the presence of KLVFF, small decreases in fluorescence were observed at 2-fold and 10-fold excess compared with Aβ42 alone (Figure 2A; light grey). Conversely, in the presence of either peptides 1 or 2, a dramatic decrease in fluorescence was observed compared with Aβ42 alone (Figure 2A; dark and light blue, respectively). Essentially, peptide 2 achieved near complete inhibition at a 1 : 2 molar ratio (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2. Peptide 2 as a most effective inhibitor of Aβ42 fibril elongation.

(A) ThT fluorescence assay monitoring fibril elongation and formation of Aβ42 in the absence (100 µM, black) and presence of wAib (dark grey), KLVFF (light grey) and peptide inhibitors 1 (blue) and 2 (purple) at various molar ratios (ranging from 1 : 1 to 1 : 20 Aβ42 : inhibitor). (B) The degree of inhibition of Aβ42 fibril elongation (calculated at the conclusion of the assay) of wAib, KLVFF, 1 and 2 across the range of molar ratios. Data reported in A and B is presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3). (C) TEM images of mature Aβ42 fibrils in the absence and presence of inhibitors at a 1 : 2 molar ratio (Aβ42 : inhibitor). Scale bars represent 200 nm.

The specificity of each peptide to Aβ42 was also assessed by performing an α-synuclein (αS) fibril elongation assay and measuring the change in ThT fluorescence. An abnormal accumulation of α-synuclein protein in the brain is associated with the onset of Parkinson's disease. [74] In the presence of these inhibitors, only peptide 1 displayed a distinct decrease in fluorescence at a 1 : 2 molar ratio (αS:inhibitor) (Supplementary Figure S10). Notably, peptide 2 showed no effect on α-synuclein aggregation, demonstrating the significance of the specific D-amino acid sequence, and the secondary structure within this potent peptide-based inhibitor for specificity towards Aβ42.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was also used to examine the morphology of Aβ42 fibrils in the absence and presence of the inhibitory peptides at the conclusion of the aggregation assays. In the absence of inhibitors, Aβ42 incubated alone is observed to form a dense network typical of amyloid fibrils (Figure 2C). In the presence of either wAib or KLVFF, Aβ42 also exhibits a dense fibrillar structure at the molar ratio tested (1 : 2) (Aβ42:inhibitor) (Figure 2C). Previous studies, using a KLVFF-NH2 peptide as a control, observed similar dense fibrilization when incubated with Aβ42 at a similar stoichiometric ratio. [37,42] In the presence of peptide 1, the abundance of Aβ42 fibrils is reduced considerably when compared with the two controls (Figure 2C). However, in the presence of peptide 2, small fibril seeds are sparsely distributed, with no large fibrillar structures observed (Figure 2C), highlighting its capacity as a potent inhibitor. Overall, the data from the ThT assays are commensurate with the associated TEM images for both controls and peptide inhibitors.

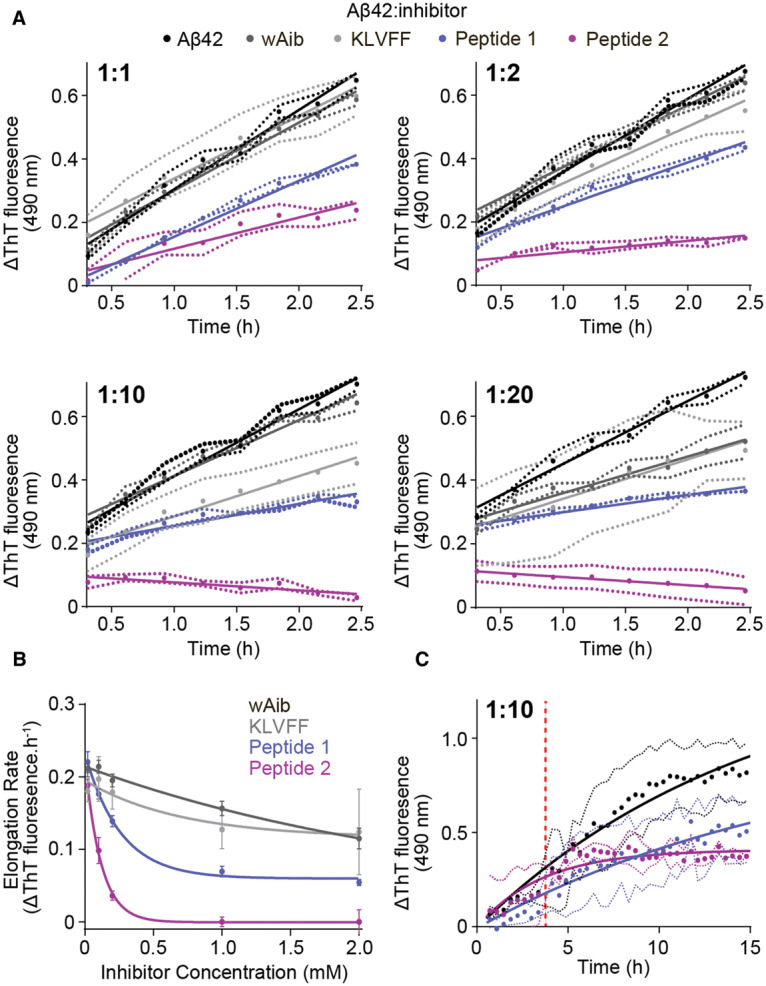

Due to the absence of an observable lag-phase where primary nucleation would occur, changes in ThT fluorescence during the elongation phase (Figure 1A, 0.5–2.5 h) were examined to determine the elongation rate from the range of molar ratios tested (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S3). Both wAib and KLVFF do not drastically affect the rate of Aβ42 fibril elongation (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S3). In contrast, peptides 1 and 2 significantly reduce the rate of fibril elongation such that a 10-fold excess of peptide 2 remarkably halts fibril elongation altogether (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S3). In addition, the relationship between inhibitor concentration and Aβ42 was determined to provide evidence as to whether peptides 1 and 2 interact with Aβ42 species to attenuate fibril formation (Figure 3B). As the concentration of wAib and KLVFF increases there is little effect on fibril elongation (i.e. less than a 50% decrease in the elongation rate at a 20-fold excess). However, as the concentration of peptides 1 and 2 increases there is a dramatic reduction in fibril elongation, suggesting that these peptides interact with fibrillar Aβ42 and prevent further monomer recruitment.

Figure 3. Peptide 2 drastically reduces the rate of Aβ42 fibril elongation.

(A) The change in ThT fluorescence during the elongation phase of Aβ42 (100 µM) fibril formation in the absence (black) and presence (grey, blue and purple) of inhibitors at a range of molar ratios (0–2.5 h from Figure 2A). (B) The rate of Aβ42 fibril elongation as a function of inhibitor concentration (mM) was fitted with a non-linear one-phase decay fit. (C) ThT fluorescence assay of Aβ42 (10 µM) spiked after 4.5 h (red dashed line) with peptides 1 and 2 (100 µM) during incubation where no decrease in fibrilization was observed. Data reported is presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

In addition, the mechanism(s) in which peptides 1 and 2 prevent Aβ42 fibrilization were probed by examining their ability to disassemble pre-formed fibrils (Figure 3C). Fibril elongation was allowed to proceed for 4.5 h, at which point a 10-fold molar excess of either peptide 1 or 2 was added (Figure 3C, red dashed line). In contrast with peptide 1, peptide 2 exhibits a plateau in ThT fluorescence for the duration of the assay (Figure 3C). Collectively, this indicates that the peptides, particularly 2, do not disassemble pre-formed fibrils but interact with the ends of fibrils to prevent subsequent elongation. Overall the data indicates that both peptides, in particular peptide 2, preferentially interact with Aβ42 fibrils to prevent further fibrilization. The fact that peptide 2 does not disassemble existing fibrils, thereby potentially avoiding the formation of toxic oligomers, reinforces the feasibility of the proposed binding mode (mechanism) where a robust interconnection is made between the two by virtue of their sequence homology, heterochiral nature, and complementary β-strand conformation.

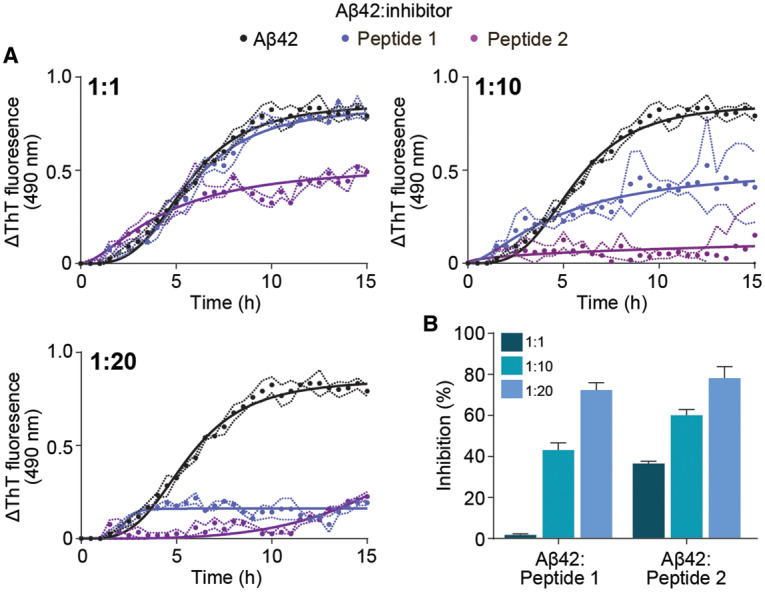

Peptide 2 also interacts with Aβ42 monomers by inhibiting primary nucleation mediated Aβ42 fibril formation

The ability of peptides 1 and 2 to prevent primary nucleation mediated Aβ42 fibril formation was also assessed by ThT fluorescence assays. Under conditions that induce primary nucleation fibril formation (typically 5–10 µM)[65,75] and in the absence of inhibitors, Aβ42 follows sigmoidal-like aggregation kinetics at the concentration examined (10 µM) whereby the lag-phase and subsequent fibril elongation begins at ∼1.5 h, reaching a plateau at ∼13 h (Figure 4A). In the presence of peptide 1, no distinct change in aggregation kinetics was observed at a 1 : 1 molar ratio (Aβ42 : inhibitor) compared with Aβ42 alone (Figure 4A, blue), conferring only 2% inhibition (Figure 4B). At 1 : 10 and 1 : 20 molar ratios, a significant decrease in total fibril formation was observed, with plateaus at 10 h and 4 h, respectively with no change in lag-phase (i.e. primary nucleation) or elongation rate (Figure 4A). Subsequently, peptide 1 conferred 3% (1 : 1), 41% (1 : 10) and 70% (1 : 20) inhibition, whilst peptide 2 afforded 36% (1 : 1) and 60% (1 : 10) inhibition (Figure 4A,B). At a 1 : 20 molar ratio, peptide 2 drastically changes the aggregation kinetics of Aβ42, extending the lag-phase to 7 h and slowing the rate of fibril elongation (Figure 4A, purple), resulting in 79% inhibition (Figure 4B). We propose that peptide 2 can interact with Aβ42 monomers in order to prevent fibril formation, however further studies are needed to substantiate this notion, and these will be discussed in the following section. When combined with our fibril elongation assay data, the mechanism(s) of inhibition utilized by 1 and 2 are distinct as both predominantly interact with Aβ42 fibrils, whilst peptide 2 also interacts with Aβ42 monomers by inhibiting primary nucleation and subsequent fibril elongation.

Figure 4. Peptide 2 as a most effective inhibitor of Aβ42 fibrilization.

(A) ThT fluorescence assay monitoring fibril formation of Aβ42 in the absence (10 µM, black) and presence of peptide inhibitors 1 (blue) and 2 (purple) at various molar ratios (ranging from 1 : 1 to 1 : 20, Aβ42 : inhibitor). (B) The degree of inhibition of Aβ42 fibril formation (calculated at the conclusion of the assay) induced by peptides 1 and 2 across the range of molar ratios examined. Data reported in A and B is presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

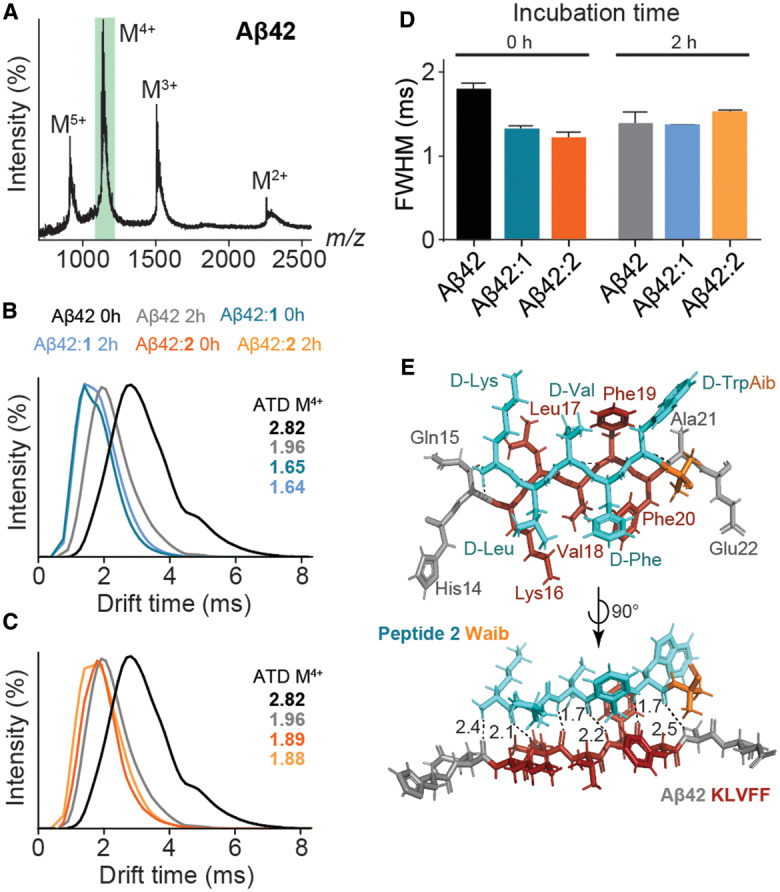

Peptide 2 induces conformational changes on aggregation-prone Aβ42 monomers

Native ion-mobility mass spectrometry (IM-MS) and molecular modelling were used to determine whether peptides 1 and 2 modulate the conformation of aggregation-prone Aβ42 monomers as an additional means of fibril inhibition (Figure 5). Native MS is a useful biophysical tool to probe the tertiary and quaternary structures, and dynamics of non-covalent protein-peptide assemblies (Figure 5A). When coupled to ion-mobility separation, the conformation of aggregation-prone assemblies can be visualized and assessed by observing the arrival time distribution (ATD) of individual protein species (e.g. monomers and dimers) during fibril formation (Figure 5B,C). In the absence of peptides 1 and 2, Aβ42 monomers undergo a disorder to order transition during incubation, as evidenced by the decrease in ATD (2.82 ms to 1.96 ms) after 2 h incubation, which is typical of fibril forming proteins [68] (Figure 5B,C). Upon addition of either peptides 1 or 2 prior to incubation, an ATD shift was observed. In the presence of peptide 1 (1.65 ms) and 2 (1.89 ms) this distribution (and hence monomer conformation) did not change further during aggregation (Figure 5B,C), which demonstrates that Aβ42 monomers adopt a compact (i.e. more ordered) conformation upon immediate addition of inhibitor. The degree of heterogeneity within the monomer can be reported by the full-width half maximum (FWHM) (Figure 5D), where high FWHM values indicate monomers adopting more conformations across a broader ATD, and lower FWHM values indicate monomers adopting a comparatively restricted ensemble of conformations. The conformational heterogeneity of Aβ42 monomers during incubation is reduced (1.88 to 1.34 ms) (Figure 5B,C). The immediate addition and incubation of 1 did not induce any change in conformational heterogeneity of Aβ42 monomers during incubation (1.26 to 1.30 ms) (Figure 5B, inset). However, upon immediate addition and subsequent incubation of Aβ42 with 2, we observed an increase in conformational heterogeneity (1.19 to 1.41 ms) (Figure 5D). This compaction and change in conformational heterogeneity of Aβ42 monomers induces similar structural changes that are normally required for fibrilization, yet are unable to anneal on fibrils (i.e. fibril elongation), as has been previously suggested. [30]

Figure 5. Probing the interaction between peptides 1 and 2, and Aβ42 monomers by native IM-MS and molecular modelling.

(A) Native IM-MS of Aβ42 (10 µM) in 200 mM ammonium acetate (pH 7.0) at 0 h with the monomer4+ (M4+; m/z 1128) being selected for ATD analysis (green box). (B and C) ATDs of Aβ42 M4+ during incubation with peptide 1 (B) and 2 (C) at a 1 : 10 molar ratio (Aβ42 : peptide 1/2) at low activation energies (10–20 V). Aβ42 monomers in the absence of peptide 1 or 2 exhibit a disorder to order transition (black to grey) after 2 h incubation (37°C). The addition of peptides 1 (dark blue, 0 h; light blue, 2 h) or 2 (dark orange, 0 h; light orange, 2 h) immediately induces a conformational change of Aβ42 monomers and persists during the initial stages of fibril formation (left panels). (D) FWHM time for Aβ42 M4+ ATDs in the absence and presence of 1 and 2 after 0 h and 2 h incubation (mean ± SD, n = 3). (E) Molecular modelling illustrates the interaction between a truncated segment of Aβ42 (residues 14–22) and peptide 2 (light blue), mediated by strong H-bonding between residues klvfw of 2, and KLVFF of Aβ42, by virtue of their sequence homology (H-bond distances in Å, dashed lines).

In light of this ATD data, molecular modelling was employed to further probe the interaction between Aβ42 monomers and peptide 2. The modelling data demonstrates that peptide 2 is capable of forming six strong intermolecular H-bonds with a truncated segment of Aβ42 (residues 14–22; HQKLVFFAE) (Figure 5E). The data also indicates that, like KLVFF, peptide 1 is prone to self-association via intermolecular H-bonding (Supplementary Figure S8A). Thus, there is competition with KLVFF and peptide 1, between self-aggregation and interaction with Aβ42. In contrast, peptide 2 does not self-aggregate (Supplementary Figure S8B) and preferentially binds to Aβ42. We propose that peptide 2 induces conformational changes to Aβ42 monomers through transient interactions, which is analogous to various fibrilization inhibitors such as molecular chaperones [76] and flavones. [77] The data shows that peptide 2 is capable of forming a strong H-bond network specific to residues 16–20 of Aβ42. This ‘in-register’ parallel β-sheet architecture is found in the hydrophobic central core region of Aβ [78] and is common to most other pathological human amyloids. [79] This arrangement, with the all D-peptide forming intermolecular hydrogen bonds with the all L-Aβ42 peptide, positions the side chains of the adjacent peptides opposite to one another, which would help alleviate charge repulsion between lysine residues. Supplementary Figure S9 shows the model of peptide 2 from above, with residues 1–5 comprising a β-strand structure, with the exception of the Aib residue. Each backbone carbonyl and amide hydrogen of amino acids 1–5 are positioned as a β-strand, whereas those associated with the Aib residue adopt a different orientation, which is not conducive to intermolecular hydrogen bonding to Aβ42 from above or below. We have previously shown the geminally disubstituted Aib residue to reduce backbone flexibility within a peptide. [80] Collectively, our results demonstrate that peptide 2 interacts with both monomeric and fibrillar Aβ42 to inhibit fibril formation and elongation. This interaction is sequence-specific, with the C-terminal Aib β-breakage moiety of 2 preventing further intermolecular hydrogen bonding, thus impeding the self-assembly process.

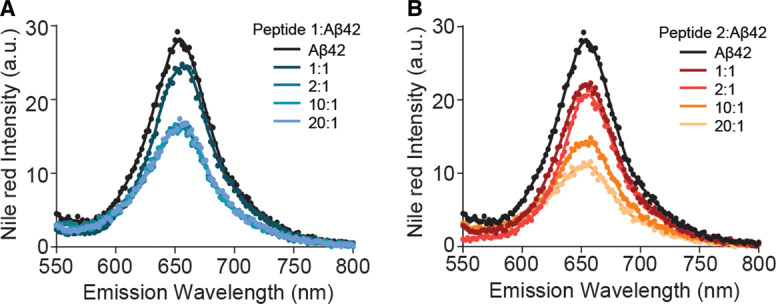

Peptide 2 significantly reduces hydrophobicity of Aβ42 fibrils

To further understand the mechanism(s) by which 1 and 2 interact with Aβ42, we investigated whether these peptides could reduce the exposed hydrophobicity of Aβ42 fibrils (Figure 6A,B). Fibrils were labelled with Nile red (10 µM) in the absence and presence of peptides 1 and 2 at the molar ratios tested in the ThT fluorescence assays (see Materials and Methods section for details). No shift in the emission wavelength was observed in the absence or presence of peptides 1 and 2 (Figure 6A,B). Upon treatment with either peptide, there was an observable concentration-dependent decrease in Nile red fluorescence, with peptide 2 inducing a considerably greater decrease in fluorescence intensity compared with peptide 1 at a 1 : 20 molar ratio (Aβ42 : inhibitor) (Figure 6A,B). This indicates that peptide 2 decreases the surface hydrophobicity of Aβ42 fibrils, potentially reducing their toxicity.

Figure 6. Peptide 2 significantly reduces hydrophobicity of Aβ42 fibrils.

(A and B) Nile red emission fluorescence of Aβ42 fibrils (10 µM) in the absence and presence of peptides 1 (A) and 2 (B) at various molar ratios (1 : 1 to 20 : 1, peptide : Aβ42).

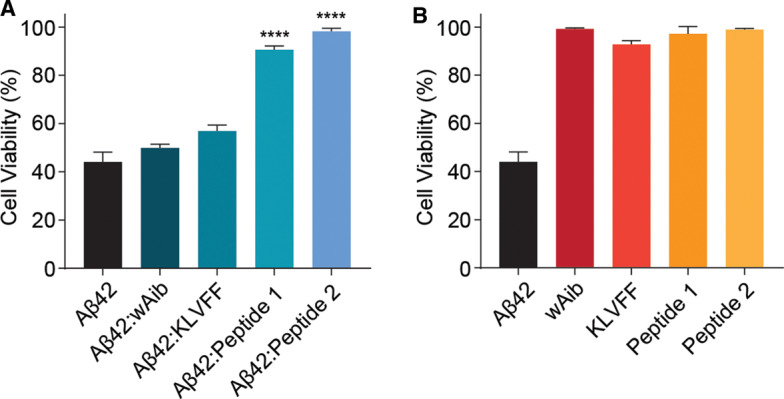

Peptide 2 significantly reduces cytotoxicity of Aβ42 fibrils

The cytotoxic effects of Aβ42 aggregation on various cell types are well known, [81] and here we investigate the ability of these peptide-based inhibitors to decrease cytotoxicity in the presence of Aβ42 fibrils using an MTT cell viability assay (see Materials and Methods section for details). Firstly, the presence of inhibitors to specifically exert cytotoxic effects on cells was examined (Figure 7). Cells treated with both Aβ42 and inhibitors were analyzed at a 1 : 2 molar ratio (Aβ42 : inhibitor). Across all compounds tested, there was no drastic change in cell viability in the absence of Aβ42, indicating that the inhibitors (and controls) alone do not affect cell viability. Upon addition of exogenous Aβ42 fibrils to murine neuroblastoma Neuro-2a cells, a substantial decrease in cell viability was observed (∼56% decrease, Figure 7A,B). The addition of either wAib or KLVFF in the presence of Aβ42 fibrils does not significantly increase cell viability compared with cells incubated with Aβ42 alone (Figure 7A). However, the addition of peptides 1 and 2 significantly increases cell viability to ∼90% and ∼99%, respectively, compared with Aβ42 alone (Figure 7A). Overall, the data indicates that peptides 1 and 2 are both biocompatible, and reduce Aβ42 fibril-induced toxicity at the cellular level. Most notably, peptide 2 incubated with Aβ42, drastically restores cell viability.

Figure 7. Peptide 2 significantly restores cell viability upon addition of Aβ42 fibrils.

(A and B) Neuro-2a cells were treated with various inhibitors in the presence (A) and absence (B) of pre-formed Aβ42 fibrils (50 µM). Cells treated with both Aβ42 and inhibitors were examined at a 1 : 2 molar ratio (Aβ42 : inhibitor). Cells were incubated for 24 h and cell viability was measured upon addition of MTT (0.5 mg/ml). Data reported is presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3) (** P < 0.01, **** P < 0.0001).

In summary, the aggregation of Aβ42 monomers to potentially neurotoxic oligomers and fibrils is believed to be responsible for the onset of AD, with the first step in this process being a conformational change to a β-sheet geometry. Inhibitors designed expressly for Aβ42 aggregation require high specificity, hence the design and synthesis of peptide 2 was based on the β-strand-containing KLVFF region of the amyloid peptide, together with an Aib β-sheet disruption element. This is the first study of its type to successfully exploit the synergy between a recognition and disruption component incorporated into a peptide comprising D-amino acids, for the specific inhibition of Aβ42 aggregation. NMR and IR data, together with molecular modelling, confirm the presence of a β-strand conformation throughout the inhibitor, with the exception of the Aib ‘β-breaker’ moiety. Experimental data show that peptide 2 prevents fibril formation, specifically towards Aβ42, and significantly reduces the rate of fibril elongation, such that a two-fold excess essentially halts fibril elongation altogether. This peptide-based inhibitor preferentially interacts with Aβ42 fibrils by slowing elongation, likely interacting with the ends of fibrils, to prevent further fibril formation. Aggregation assays, native IM-MS and molecular modelling were used to demonstrate that peptide 2 is also capable of interacting with Aβ42 monomers to prevent oligomerization and inhibit aggregation. These results shed light on the binding mechanism and further underline the significance of the β-strand structure, and particular D-amino acid sequence, for specificity towards Aβ42. Cell viability assays demonstrate that when incubated with Aβ42 in a 2:1 molar ratio, peptide 2 exhibits essentially no cytotoxic effect whatsoever. Moreover, an effective inhibitor should not self-aggregate and, unlike the KLVFF peptide fragment, 2 fulfils this requirement. Collectively, our results show peptide 2 to be a potent inhibitor of Aβ42 monomers, oligomers and fibrils, and thus offers considerable promise for further development as a drug candidate in the treatment of AD. We set out to exploit the synergy between the recognition and disruption components incorporated into the peptide-based inhibitor, and found that the sum is greater than its parts. The synergistic rationale employed in this study could potentially be applied to enhance therapeutic efficacy for fibril forming proteins that are associated with other neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) for providing the analytical facilities used in this work, and Flinders Analytical (Flinders University, Australia) for access and support to IM-MS instrumentation. We also thank Dr. Lisa O'Donovan and Adelaide Microscopy (both University of Adelaide) for TEM technical assistance, and Prof. John A. Carver (Australian National University) for his input. Computational aspects of this work were supported by an award under the National Computational Merit Allocation Scheme for JY on the National Computing Infrastructure (NCI) National Facility at the Australian National University.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ATD

arrival time distribution

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- FWHM

full-width half maximum

- IM-MS

ion-mobility mass spectrometry

- SPPS

solid phase peptide synthesis

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- WT

wild type

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project (DP180101581) and the Centre of Excellence for Nanoscale BioPhotonics (CNBP) for financial support. We also acknowledge funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project (DP170102033) and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (44113151).

Open Access

Open access for this article was enabled by the participation of University of Adelaide in an all-inclusive Read & Publish pilot with Portland Press and the Biochemical Society under a transformative agreement with CAUL.

Author Contributions

J.R.H. designed the research, synthesized the peptides, and prepared the manuscript. B.J. designed the research, conducted assays and prepared the manuscript. K.L.W. conducted assays. J.Y. undertook computational studies. T.L.P. and A.D.A. contributed to the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.van Groen T., Schemmert S., Brener O., Gremer L., Ziehm T., Tusche M. et al. (2017) The Aβ oligomer eliminating D-enantiomeric peptide RD2 improves cognition without changing plaque pathology. Sci. Rep. 7, 16275 10.1038/s41598-017-16565-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frydman-Marom A., Convertino M., Pellarin R., Lampel A., Shaltiel-Karyo R., Segal D. et al. (2011) Structural basis for inhibiting β-amyloid oligomerization by a non-coded β-breaker-substituted endomorphin analogue. ACS Chem. Biol. 6, 1265–1276 10.1021/cb200103h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner C.J.A., Dutta S., Foley A.R. and Raskatov J.A. (2016) Introduction of d-glutamate at a critical residue of Aβ42 stabilizes a prefibrillary aggregate with enhanced toxicity. Chemistry 22, 11967–11970 10.1002/chem.201601763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacabelos R. (2018) Have there been improvements in Alzheimer's disease drug discovery over the past 5 years? Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 13, 523–538 10.1080/17460441.2018.1457645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nie Q., Du X.G. and Geng M.Y. (2011) Small molecule inhibitors of amyloid β peptide aggregation as a potential therapeutic strategy for Alzheimers disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 32, 545 10.1038/aps.2011.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasim J.K., Kavianinia I., Harris P.W.R. and Brimble M.A. (2019) Three decades of amyloid beta synthesis: challenges and advances. Front Chem 7, 472 10.3389/fchem.2019.00472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan R. and Vassar R. (2014) Targeting the β secretase BACE1 for Alzheimer's disease therapy. Lancet Neurol. 13, 319–329 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70276-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrera Guisasola E.E., Andujar S.A., Hubin E., Broersen K., Kraan I.M., Méndez L. et al. (2015) New mimetic peptides inhibitors of Αβ aggregation. Molecular guidance for rational drug design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 95, 136–152 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin Y.-S., Bowman G.R., Beauchamp K.A. and Pande V.S. (2012) Investigating how peptide length and a pathogenic mutation modify the structural ensemble of amyloid beta monomer. Biophys. J. 102, 315–324 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H.J., Korshavn K.J., Nam Y., Kang J., Paul T.J., Kerr R.A. et al. (2017) Structural and mechanistic insights into development of chemical tools to control individual and inter-related pathological features in Alzheimer's disease. Chemistry 23, 2706–2715 10.1002/chem.201605401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaffy J., Brinet D., Soulier J.-L., Correia I., Tonali N., Fera K.F. et al. (2016) Designed glycopeptidomimetics disrupt protein–Protein interactions mediating amyloid β-peptide aggregation and restore neuroblastoma cell viability. J. Med. Chem. 59, 2025–2040 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal D., Shuaib S., Mann S. and Goyal B. (2017) Rationally designed peptides and peptidomimetics as inhibitors of amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation: potential therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease. ACS Comb. Sci. 19, 55–80 10.1021/acscombsci.6b00116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coimbra J.R.M., Marques D.F.F., Baptista S.J., Pereira C.M.F., Moreira P.I., Dinis T.C.P. et al. (2018) Highlights in BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease treatment. Front. Chem. 6, 178 10.3389/fchem.2018.00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisceglia F., Natalello A., Serafini M.M., Colombo R., Verga L., Lanni C. et al. (2018) An integrated strategy to correlate aggregation state, structure and toxicity of Aß 1–42 oligomers. Talanta 188, 17–26 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.05.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveri V., Zimbone S., Giuffrida M.L., Bellia F., Tomasello M.F. and Vecchio G. (2018) Porphyrin cyclodextrin conjugates modulate amyloid beta peptide aggregation and cytotoxicity. Chemistry 24, 6349–6353 10.1002/chem.201800807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons C.G. and Rammes G. (2017) Preclinical to phase II amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide modulators under investigation for Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 26, 579–592 10.1080/13543784.2017.1313832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oren O., Banerjee V., Taube R. and Papo N. (2018) An Aβ42 variant that inhibits intra- and extracellular amyloid aggregation and enhances cell viability. Biochem. J. 475, 3087–3103 10.1042/BCJ20180247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardoso M.H., Cândido E.S., Oshiro K.G.N., Rezende S.B. and Franco O.L. (2018) Peptides containing d-amino acids and retro-inverso peptides: General applications and special focus on antimicrobial peptides In Peptide Applications in Biomedicine, Biotechnology and Bioengineering (Koutsopoulos S., ed.), pp. 131–155, Woodhead Publishing [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiqi M.K., Alam P., Iqbal T., Majid N., Malik S., Nusrat S. et al. (2018) Elucidating the inhibitory potential of designed peptides against amyloid fibrillation and amyloid associated cytotoxicity. Front. Chem. 6, 311 10.3389/fchem.2018.00311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeoh Y.Q., Yu J., Polyak S.W., Horsley J.R. and Abell A.D. (2018) Photopharmacological control of cyclic antimicrobial peptides. ChemBioChem 19, 2591–2597 10.1002/cbic.201800618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe T.L., Strzelec A., Kiessling L.L. and Murphy R.M. (2001) Structure−function relationships for inhibitors of β-amyloid toxicity containing the recognition sequence KLVFF. Biochemistry 40, 7882–7889 10.1021/bi002734u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tjernberg L.O., Näslund J., Lindqvist F., Johansson J., Karlström A.R., Thyberg J. et al. (1996) Arrest of beta-Amyloid fibril formation by a pentapeptide ligand. J. Biol Chem. 271, 8545–8548 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arai T., Sasaki D., Araya T., Sato T., Sohma Y. and Kanai M. (2014) A cyclic KLVFF-Derived peptide aggregation inhibitor induces the formation of less-toxic off-pathway amyloid-β oligomers. ChemBioChem 15, 2577–2583 10.1002/cbic.201402430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tran L. and Ha-Duong T. (2015) Exploring the Alzheimer amyloid-β peptide conformational ensemble: A review of molecular dynamics approaches. Peptides 69, 86–91 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breydo L., Kurouski D., Rasool S., Milton S., Wu J.W., Uversky V.N. et al. (2016) Structural differences between amyloid beta oligomers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 477, 700–705 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsubara T., Yasumori H., Ito K., Shimoaka T., Hasegawa T. and Sato T. (2018) Amyloid-β fibrils assembled on ganglioside-enriched membranes contain both parallel β-sheets and turns. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 14146–14154 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng P.-N., Liu C., Zhao M., Eisenberg D. and Nowick J.S. (2012) Amyloid β-sheet mimics that antagonize protein aggregation and reduce amyloid toxicity. Nat. Chem. 4, 927 10.1038/nchem.1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tjernberg L.O., Lilliehöök C., Callaway D.J.E., Näslund J., Hahne S., Thyberg J. et al. (1997) Controlling amyloid β-peptide fibril formation with protease-stable ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 12601–12605 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang-Haagen B., Biehl R., Nagel-Steger L., Radulescu A., Richter D. and Willbold D. (2016) Monomeric amyloid beta peptide in hexafluoroisopropanol detected by small angle neutron scattering. PLoS ONE. 11, e0150267 10.1371/journal.pone.0150267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colvin M.T., Silvers R., Ni Q.Z., Can T.V., Sergeyev I., Rosay M. et al. (2016) Atomic resolution structure of monomorphic Aβ42 amyloid fibrils. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 9663–9674 10.1021/jacs.6b05129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wälti M.A., Ravotti F., Arai H., Glabe C.G., Wall J.S., Böckmann A. et al. (2016) Atomic-resolution structure of a disease-relevant Aβ(1–42) amyloid fibril. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E4976–E4984 10.1073/pnas.1600749113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gremer L., Schölzel D., Schenk C., Reinartz E., Labahn J., Ravelli R.B.G. et al. (2017) Fibril structure of amyloid-β(1–42) by cryo–electron microscopy. Science 358, 116–119 10.1126/science.aao2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenberg D.S. and Sawaya M.R. (2017) Structural studies of amyloid proteins at the molecular level. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 86, 69–95 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao Y., Ma B., McElheny D., Parthasarathy S., Long F., Hoshi M. et al. (2015) Aβ(1–42) fibril structure illuminates self-recognition and replication of amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 499 10.1038/nsmb.2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eisenberg D.S. and Sawaya M.R. (2016) Implications for Alzheimer's disease of an atomic resolution structure of amyloid-β(1–42) fibrils. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 9398–9400 10.1073/pnas.1610806113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chafekar S.M., Malda H., Merkx M., Meijer E.W., Viertl D., Lashuel H.A. et al. (2007) Branched KLVFF tetramers strongly potentiate inhibition of β-amyloid aggregation. ChemBioChem 8, 1857–1864 10.1002/cbic.200700338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Austen B.M., Paleologou K.E., Ali S.A.E., Qureshi M.M., Allsop D. and El-Agnaf O.M.A. (2008) Designing peptide inhibitors for oligomerization and toxicity of Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptide. Biochemistry 47, 1984–1992 10.1021/bi701415b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kino R., Araya T., Arai T., Sohma Y. and Kanai M. (2015) Covalent modifier-type aggregation inhibitor of amyloid-β based on a cyclo-KLVFF motif. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 2972–2975 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon D.J., Sciarretta K.L. and Meredith S.C. (2001) Inhibition of β-amyloid(40) fibrillogenesis and disassembly of β-amyloid(40) fibrils by short β-amyloid congeners containing N-methyl amino acids at alternate residues. Biochemistry 40, 8237–8245 10.1021/bi002416v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matharu B., El-Agnaf O., Razvi A. and Austen B.M. (2010) Development of retro-inverso peptides as anti-aggregation drugs for β-amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Peptides 31, 1866–1872 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kokkoni N., Stott K., Amijee H., Mason J.M. and Doig A.J. (2006) N-Methylated peptide inhibitors of β-amyloid aggregation and toxicity. optimization of the inhibitor structure. Biochemistry 45, 9906–9918 10.1021/bi060837s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajasekhar K., Suresh S.N., Manjithaya R. and Govindaraju T. (2015) Rationally designed peptidomimetic modulators of Aβ toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Sci. Rep. 5, 8139 10.1038/srep08139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamley I.W. (2007) Peptide fibrillization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 46, 8128–8147 10.1002/anie.200700861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chalifour R.J., McLaughlin R.W., Lavoie L., Morissette C., Tremblay N., Boulé M. et al. (2003) Stereoselective interactions of peptide inhibitors with the β-amyloid peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34874–34881 10.1074/jbc.M212694200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arai T., Araya T., Sasaki D., Taniguchi A., Sato T., Sohma Y. et al. (2014) Rational design and identification of a non-peptidic aggregation inhibitor of amyloid-β based on a pharmacophore motif obtained from cyclo[-Lys-Leu-Val-Phe-Phe-]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 8236–8239 10.1002/anie.201405109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jagota S. and Rajadas J. (2013) Synthesis of d-amino acid peptides and their effect on beta-amyloid aggregation and toxicity in transgenic caenorhabditis elegans. Med. Chem. Res. 22, 3991–4000 10.1007/s00044-012-0386-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dammers C., Yolcu D., Kukuk L., Willbold D., Pickhardt M., Mandelkow E. et al. (2016) Selection and characterization of tau binding d-Enantiomeric peptides with potential for therapy of Alzheimer disease. PLoS ONE. 11, e0167432 10.1371/journal.pone.0167432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leithold L.H.E., Jiang N., Post J., Ziehm T., Schartmann E., Kutzsche J. et al. (2016) Pharmacokinetic properties of a novel d-peptide developed to be therapeutically active against toxic β-amyloid oligomers. Pharm. Res. 33, 328–336 10.1007/s11095-015-1791-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spanopoulou A., Heidrich L., Chen H.-R., Frost C., Hrle D., Malideli E. et al. (2018) Designed macrocyclic peptides as nanomolar amyloid inhibitors based on minimal recognition elements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 57, 14503–14508 10.1002/anie.201802979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghanta J., Shen C.-L., Kiessling L.L. and Murphy R.M. (1996) A strategy for designing inhibitors of β-amyloid toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 29525–29528 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Etienne M.A., Aucoin J.P., Fu Y., McCarley R.L. and Hammer R.P. (2006) Stoichiometric inhibition of amyloid β-protein aggregation with peptides containing alternating α,α-disubstituted amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3522–3523 10.1021/ja0600678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sciarretta K.L., Gordon D.J. and Meredith S.C. (2006) Peptide-based inhibitors of amyloid assembly. Methods Enzymol. 413, 273–312 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13015-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soto C., Kindy M.S., Baumann M. and Frangione B. (1996) Inhibition of Alzheimer's amyloidosis by peptides that prevent β-Sheet conformation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 226, 672–680 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Botz A., Gasparik V., Devillers E., Hoffmann A.R.F., Caillon L., Chelain E. et al. (2015) (R)-α-trifluoromethylalanine containing short peptide in the inhibition of amyloid peptide fibrillation. Peptide Sci. 104, 601–610 10.1002/bip.22670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilead S. and Gazit E. (2004) Inhibition of amyloid fibril formation by peptide analogues modified with α-aminoisobutyric acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 116, 4133–4136 10.1002/ange.200353565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frydman-Marom A., Rechter M., Shefler I., Bram Y., Shalev D.E. and Gazit E. (2009) Cognitive-Performance recovery of Alzheimer's disease model mice by modulation of early soluble amyloidal assemblies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 121, 2015–2020 10.1002/ange.200802123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Formaggio F., Bettio A., Moretto V., Crisma M., Toniolo C. and Broxterman Q.B. (2003) Disruption of the β-sheet structure of a protected pentapeptide, related to the β-amyloid sequence 17–21, induced by a single, helicogenic Cα-tetrasubstituted α-amino acid. J. Pept. Sci. 9, 461–466 10.1002/psc.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parsons C.G., Ruitenberg M., Freitag C.E., Sroka-Saidi K., Russ H. and Rammes G. (2015) MRZ-99030 – A novel modulator of Aβ aggregation: I – mechanism of action (MoA) underlying the potential neuroprotective treatment of Alzheimer's disease, glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Neuropharmacology 92, 158–169 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frydman-Marom A., Shaltiel-Karyo R., Moshe S. and Gazit E. (2011) The generic amyloid formation inhibition effect of a designed small aromatic β-breaking peptide. Amyloid 18, 119–127 10.3109/13506129.2011.582902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bett C.K., Serem W.K., Fontenot K.R., Hammer R.P. and Garno J.C. (2010) Effects of peptides derived from terminal modifications of the Aβ central hydrophobic core on Aβ fibrillization. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 1, 661–678 10.1021/cn900019r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang L., Yagnik G., Peng Y., Wang J., Xu H.H., Hao Y. et al. (2013) Kinetic studies of inhibition of the amyloid beta (1-42) aggregation using a ferrocene-tagged β-sheet breaker peptide. Anal. Biochem. 434, 292–299 10.1016/j.ab.2012.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barz B. and Strodel B. (2016) Understanding amyloid-β oligomerization at the molecular level: the role of the fibril surface. Chemistry 22, 8768–8772 10.1002/chem.201601701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valiev M., Bylaska E.J., Govind N., Kowalski K., Straatsma T.P., van Dam H.J.J. et al. (2010) NWChem: a comprehensive and scalable open-source solution for large scale molecular simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 181, 1477 10.1016/j.cpc.2010.04.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C. et al. (2004) UCSF chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ryan T.M., Caine J., Mertens H.D.T., Kirby N., Nigro J., Breheney K. et al. (2013) Ammonium hydroxide treatment of Aβ produces an aggregate free solution suitable for biophysical and cell culture characterization. PeerJ 1, e73–e73 10.7717/peerj.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ecroyd H. and Carver J.A. (2008) The effect of small molecules in modulating the chaperone activity of αB-crystallin against ordered and disordered protein aggregation. FEBS J. 275, 935–947 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buell A.K., Galvagnion C., Gaspar R., Sparr E., Vendruscolo M., Knowles T.P.J. et al. (2014) Solution conditions determine the relative importance of nucleation and growth processes in α-synuclein aggregation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 7671–7676 10.1073/pnas.1315346111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu Y., Jovcevski B. and Pukala T.L. (2019) C-Phycocyanin from spirulina inhibits α-synuclein and amyloid-β fibril formation but not amorphous aggregation. J. Nat. Prod. 82, 66–73 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiang N., Frenzel D., Schartmann E., van Groen T., Kadish I., Shah N.J. et al. (2016) Blood-brain barrier penetration of an Aβ-targeted, arginine-rich, d-enantiomeric peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858, 2717–2724 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fernando S.R.L., Kozlov G.V. and Ogawa M.Y. (1998) Distance dependence of electron transfer along artificial beta-strands at 298 and 77K. Inorg. Chem. 37, 1900–1905 10.1021/ic970369y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhuang W., Hayashi T. and Mukamel S. (2009) Coherent multidimensional vibrational spectroscopy of biomolecules: Concepts, simulations, and challenges. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.Engl. 48, 3750–3781 10.1002/anie.200802644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gillespie P., Cicariello J. and Olson G.L. (1997) Conformational analysis of dipeptide mimetics. Pept. Sci. 43, 191–217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hasegawa K., Yamaguchi I., Omata S., Gejyo F. and Naiki H. (1999) Interaction between Aβ(1−42) and Aβ(1−40) in Alzheimer's β-Amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Biochemistry 38, 15514–15521 10.1021/bi991161m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li B., Ge P., Murray K.A., Sheth P., Zhang M., Nair G. et al. (2018) Cryo-EM of full-length α-synuclein reveals fibril polymorphs with a common structural kernel. Nat. Commun. 9, 3609 10.1038/s41467-018-05971-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cater J.H., Kumita J.R., Zeineddine Abdallah R., Zhao G., Bernardo-Gancedo A., Henry A. et al. (2019) Human pregnancy zone protein stabilizes misfolded proteins including preeclampsia- and Alzheimer's-associated amyloid beta peptide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 6101 10.1073/pnas.1817298116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cox D., Selig E., Griffin M.D.W., Carver J.A. and Ecroyd H. (2016) Small heat-shock proteins prevent α-synuclein aggregation via transient interactions and their efficacy Is affected by the rate of aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 22618–22629 10.1074/jbc.M116.739250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Das S., Pukala T.L. and Smid S.D. (2018) Exploring the structural diversity in inhibitors of α-synuclein amyloidogenic folding, aggregation, and neurotoxicity. Front. Chem. 6, 181 10.3389/fchem.2018.00181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Benzinger T.L.S., Gregory D.M., Burkoth T.S., Miller-Auer H., Lynn D.G., Botto R.E. et al. (1998) Propagating structure of Alzheimer's β-amyloid (10–35) is parallel β-sheet with residues in exact register. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13407–13412 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gorkovskiy A., Thurber K.R., Tycko R. and Wickner R.B. (2014) Locating folds of the in-register parallel β-sheet of the Sup35p prion domain infectious amyloid. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E4615–E4622 10.1073/pnas.1417974111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yu J., Horsley J.R., Moore K.E., Shapter J.G. and Abell A.D. (2014) The effect of a macrocyclic constraint on electron transfer in helical peptides: A step towards tunable molecular wires. Chem. Commun. 50, 1652 10.1039/c3cc47885h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ziehm T., Brener O., van Groen T., Kadish I., Frenzel D., Tusche M. et al. (2016) Increase of positive Net charge and conformational rigidity enhances the efficacy of d-enantiomeric peptides designed to eliminate cytotoxic Aβ species. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 7, 1088–1096 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.