Abstract

Aims

Employers in the United States incur substantial costs associated with substance use disorders. Our goal was to examine the effectiveness of employer‐led interventions to reduce the adverse effects of drug misuse in the workplace.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of studies that evaluated the effectiveness of recommended workplace interventions for opioids and related drugs: employee education, drug testing, employee assistance programs, supervisor training, written workplace drug‐free policy, and restructuring employee health benefit plans. We searched PubMed MEDLINE, EMBASE (embase.com), PsycINFO (Ebsco), ABI Inform Global, Business Source Premier, EconLit, CENTRAL, Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), Scopus (Elsevier), Proquest Dissertations, and Epistemonikos from inception through May 8, 2019, with no date or language restrictions. We included randomized controlled trials, quasi‐experimental studies, and cross‐sectional studies with no language or date restrictions. The Downs and Black questionnaire was used to assess the quality of included studies. The results were reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

In all, 27 studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. Results were mixed, with each intervention shown to be effective in at least one study, but none showing effectiveness in over 50% of studies. Studies examining the impact of interventions on workplace injuries or accidents were more commonly reported to be effective. Although four studies were randomized controlled trials, the quality of all included studies was “fair” or “poor.”

Conclusions

Despite the opioid epidemic, high‐quality studies evaluating the effectiveness of employer‐led interventions to prevent or reduce the adverse effects of substance use are lacking. Higher quality and mixed methods studies are needed to determine whether any of the interventions are generalizable and whether contextual adaptations are needed. In the meantime, there is a reason to believe that commonly recommended, employer‐led interventions may be effective in some environments.

Keywords: illicit drugs, intervention, opioids misuse, systematic review, workplace

1. INTRODUCTION

The United States (US) is facing its worst opioid crisis in history. 1 , 2 Despite efforts to mitigate the epidemic, drug overdoses were responsible for approximately 70 237 deaths in 2017 (47 600; 67.8% from opioids), representing a 9.6% increase from 2016. 1 , 2 , 3 Substance use disorder, which includes the misuse of opioids, has a significant impact on the workforce. A recent analysis of the 2012‐2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicated that 20.2 million adults had a self‐reported substance use disorder, and more than 60% were employed. 4 Given the large number of employees reporting a substance use disorder, employers are incurring a significant portion of the estimated $400 billion annual cost of substance abuse, 4 including costs associated with absenteeism, occupational injuries, 5 turnover, and health care. 4 The need for effective interventions to reduce the burden of substance use, including misuse of opioids, in the workplace is urgent and could potentially target a large proportion of users.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services recommends five types of employer‐initiated interventions. 6 These interventions include the following: establishment of a clear written workplace policy on substance use; employee education to improve knowledge about opioids and other potentially addictive medication; training of supervisors to keep them updated with the most recent workplace drug policies and identification of signs of impairment among other things; employee assistance programs to support confidential treatment of affected workers adoption of drug‐testing policies; and redesigning health benefits to improve access to health services. In some instances, interventions are extended to immediate family members of employees because of the known negative impact of ill health among employees’ family members on workplace productivity.

Despite the increase in the number of organizations adopting interventions to deter employees from the misuse of prescription medication and illegal drugs, 7 , 8 critical evaluation of the effectiveness of these interventions is sparse. Reviews are either dated 9 , 10 , 11 or focused on a particular occupational group, 12 drug, 12 intervention, 12 , 13 , 14 or outcome. 12 , 14 Prior reviews have concluded that there is weak evidence to support the effectiveness of recommended interventions to deter employees from illicit drug use. However, the opioid epidemic has generated renewed interest in this field as employers seek the best ways to insulate the workplace from the adverse effects of drugs. Given the limitations of previous reviews, our goal was to systematically review the evidence of the effectiveness of recommended employer‐initiated interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of major drugs of abuse in the workplace.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) 15 guideline for reporting this systematic review and registered the review protocol in the International prospective register of systematic reviews, PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42019132681).

2.1. Search strategy

We searched PubMed MEDLINE, EMBASE (embase.com), PsycINFO (Ebsco), ABI Inform Global, Business Source Premier, EconLit, CENTRAL, Web of Science (Thomson Reuters), Scopus (Elsevier), Proquest Dissertations, and Epistemonikos from inception through May 8, 2019, with no date or language restrictions. Terms used in the search included workplace, employer, employee, substance‐related disorders, substance abuse, substance misuse, and interventions. A full list of the search strategies is outlined in Appendix A.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐experimental studies, cohort studies, cross‐sectional studies, and pre‐post studies that investigated the effectiveness of an employer‐initiated intervention to reduce the adverse effects of opioids and other drugs of addiction. We focused on the six categories of employer‐initiated interventions recommended by SAMHSA and other related organizations 6 , 16 , 17 : employee education, drug testing (random, post‐accident and reasonable suspicion), employee assistance programs (EAP), supervisor training, written workplace drug‐free policy, and restructuring of employee health benefit plans. 6 We excluded studies that exclusively investigated pre‐employment drug screening, as our focus was on interventions targeted to employees. We included articles focused on the eight groups of drugs identified during the 2015‐2017 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health as the major drugs of abuse in the United States 18 (Appendix B). We included articles that reported outcomes related to drug use or their direct effects, including accidents and injuries, absenteeism, healthcare utilization, cost, and other measures of productivity. Interventions were considered to be effective if they reduced drug use or the adverse effects of drug use. We excluded case reports, case series, editorials, commentaries, and publications that investigated workplace interventions only for alcohol abuse or tobacco use.

2.3. Data collection and processing

Search results were saved into EndNote files by the librarian (LCO) and transferred into Covidence 19 for subsequent processing. Two reviewers (MOA and CBI) independently performed the title and abstract screening, and the full‐text screening. Conflicts were resolved through consensus. Extraction of data from included studies was carried out independently by three reviewers (MOA, ASR, and CBI; two reviewers per article) using a data extraction template designed by the investigators and embedded into Covidence. Information extracted included: year of publication, the country where the intervention took place, study design, study sample, number of participants, intervention type, outcome measures, and effectiveness of the intervention. For study outcomes, we selected results from fully adjusted models, when available. For studies that reported outcomes for several illicit drugs, we selected outcomes of opioids. We selected the most rigorous assessment of the reported outcomes.

2.4. Methodical quality assessment

We assessed the methodical rigor of the included studies using the modified Downs and Black checklist for randomized and non‐randomized studies for healthcare. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 The checklist has 27 items, with a total possible score of 28. Papers were rated excellent if they scored above 25, good if they scored between 20 and 25, fair if they scored between 15 and 19, and poor if they scored <15. 24 Each study was assessed by two independent investigators, and discrepancies in scoring were resolved through consensus.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study selection

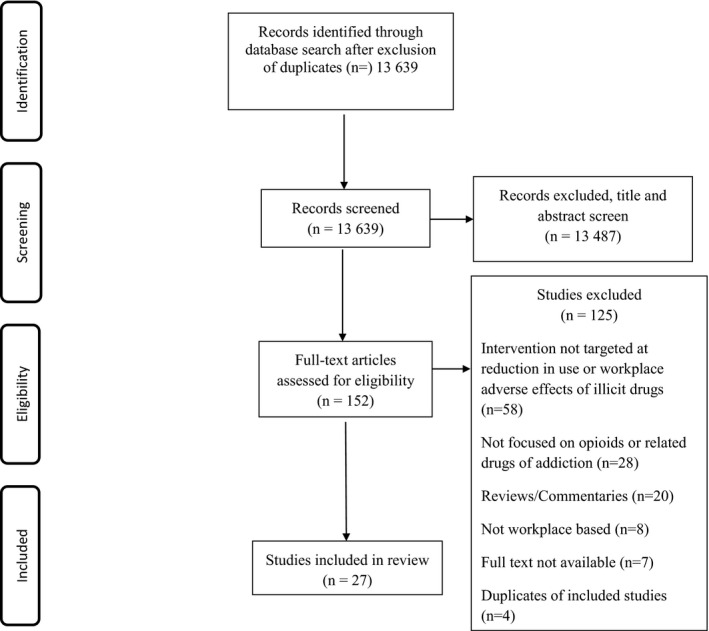

We identified 21 620 titles (PubMed MEDLINE 3014; EMBASE [embase.com] 4430; PsycINFO [Ebsco] 962; ABI Inform Global 1793; Business Source Premier 120; EconLit 45; CENTRAL 3273; Web of Science [Thomson Reuters] 1603; Scopus [Elsevier] 5551; Proquest Dissertations 327; and Epistemonikos 502). After the removal of duplicates, 13 639 title and abstracts were screened. Based on the review of titles and abstracts, 13 487 papers unrelated to the topic of interest were excluded. The full‐text review was conducted on 152 articles out of which 27 were ultimately included in the review. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 The list of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion are shown in Appendix C. The level of concordance of the reviewers during the initial full‐text review was 83%. Figure 1 shows the study flowchart.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Flow chart for literature search

3.2. Characteristics of studies

Four 25 , 28 , 29 , 43 of the 27 included studies were RCTs. Nine studies were quasi‐experimental studies, of which eight were interrupted time‐series analyses, 32 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 42 , 47 , 49 and one was historically controlled. 27 In all, 14 studies were observational studies, of which seven were cross‐sectional, 26 , 31 , 33 , 41 , 44 , 46 , 50 and seven were cohort studies. 30 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 45 , 48 , 51 The majority of the studies (23/27; 85%) were carried out among employees in the United States. Australia, Canada, Portugal, and Spain had one study each. The most common independent intervention was drug testing, which had 12 independent analyses from 11 studies. 26 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 42 , 45 , 50 Seven analyses from five studies evaluated the effectiveness of EAPs, 26 , 27 , 39 , 49 , 51 while six studies investigated the impact of employee education. 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 39 , 43 Less commonly evaluated single interventions were written workplace drug‐free policies with five effectiveness evaluations 26 , 33 , 39 , 44 , 50 and restructuring of employee benefits, with three evaluations from two studies. 34 , 48 Four studies evaluated multiple interventions independently, 26 , 33 , 39 , 48 and six studies evaluated multiple interventions collectively. 32 , 36 , 40 , 44 , 47 , 51 The most frequently assessed outcomes were the reduction in illicit drug use and reduction in workplace accidents. Other reported outcomes included direct costs (eg, cost of injuries, cost of mental health services, company claims), absenteeism, involuntary turnover, and healthcare utilization (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of studies evaluating workplace interventions for opioid use disorder and related conditions

| Study | Study design | Intervention(s) | Country | Industry | Number of participants | Number of companies/sites | Outcomes evaluated (measurement method) | Quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee education | ||||||||

| Brochu 1988 25 | Randomized controlled trial | Employee education | Canada | Not reported | 435 | 1 site | Illicit drug use (self‐report using randomized response technique) | Fair |

| Cook et al 2000 28 | Randomized controlled trial | Employee education | USA | Insurance | 424 | 1 site | Drug use (self‐report) | Poor |

| Cook 2004 29 | Randomized controlled trial | Employee education | USA | Construction | 201 | 5 sites | Drug and marijuana use (self‐report and urine and hair tests) | Fair |

| Patterson 2005 43 | Randomized controlled trial | Employee education | USA | Construction (37% of participants), small aircraft pilots and maintenance (4%), bus drivers (19%), materials moving (10%), hotels (6%), restaurants (including bars and cafeterias; 16%), and other services (home health care, car washes, concessions; 9%). | 539 | Survey of small business employees | Use of over‐the counter drugs for unwinding (self‐report) | Fair |

| Drug testing | ||||||||

| French 2004 31 | Cross‐sectional | Suspicion‐based and random drug testing | USA | National Survey | 15 400 | National survey | Drug use (self‐report) | Fair |

| Marques 2014 37 | Retrospective cohort study | Random drug testing | Portugal | Transportation (railway) | 3801 | 1 company | Workplace accidents (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Messer 1996 38 | Retrospective cohort study | Random drug testing | USA | Transportation | 16 739 | 1 agency | Rates of vehicular accidents and passenger injuries (routinely collected data), Substance use (biochemical tests) | Fair |

| Lockwood 2000 35 | Interrupted time series with no control | Random drug test | USA | Hotel | Not reported | 1 hotel | Workplace accidents (routinely collected data) | Poor |

| Ozminkowski 2003 42 | Interrupted time series with no control | Random drug testing | USA | Manufacturing | 1791 | 15 sites | Total medical expenditures, Expenditure for substance abuse or related treatment, Workplace injuries (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Shepard 1998 46 | Cross‐sectional | Random drug testing | USA | Computer and communications equipment | Not reported | 63 companies | Productivity per worker defined by sales (routinely collected data) | Poor |

| Schofield 2013 45 | Retrospective cohort study | Random drug testing | USA | Construction | 185 808 952 h of employee time at risk, representing approximately 92 882 full‐time equivalent employees (FTE) | 1360 companies | Injury rates, Injury severity, Medical claims (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Morantz 2008 41 | Controlled interrupted time series | Post‐accident drug testing | USA | Retail | Not reported | Workers/compensation claims, First aid reports (routinely collected data) | Fair | |

| Feinauer 1993 30 | Retrospective cohort study | Post‐accident and reasonable cause drug testing | USA | All (with a subcategory for manufacturing) | Not reported | 48 facilities | Change in OSHA injury rate (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Employee assistance program | ||||||||

| Castro 2000 27 | Historically controlled trial | EAP | USA | Electrical and gas installation | 52 | 1 company | Accidents, Sick leave hours Workers’ compensation claims (routinely collected data) | Poor |

| Sweeney 1995 49 | Controlled interrupted time series | EAP | USA | Manufacturing | 954 | 1 site | Mental health/chemical dependency claims/person/month, Cost of mental health/chemical dependency claims/person/month (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Waehrer 2016 50 | Cross‐sectional | EAP | USA | Various non‐agricultural | 1405 | National survey | Non‐fatal workplace injuries (survey) | Fair |

| Restructuring employee health benefit plans | ||||||||

| LoSasso 2004 34 | Retrospective cohort study | Restructuring of Employee Health Benefit Plans | USA | Not specified | 656 | 399 employers | Mental health and substance abuse treatment utilization (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Sturm 2000 48 | Retrospective cohort study | Restructuring of Employee Health Benefit Plans | USA | Not specified | 408 663 person‐years (1 142 273 member‐years including dependents) | 49 employers | Substance abuse treatment utilization and cost: inpatient and outpatient (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Multiple interventions assessed separately | ||||||||

| Carpenter 2007 26 | Cross‐sectional study | Employee education, Random drug testing, Written workplace policy, EAP | USA | For‐profit firms across the USA | 57 397 | National survey | Marijuana use (self‐report/national survey) | Fair |

| Miller 2015 39 | Cross‐sectional | Employee education, Drug testing, Written workplace policy, EAP | USA | National survey | 24 230 | National survey | Drug use including any prescription drug, pain relievers, stimulants and sedatives (self‐report) | Poor |

| Lee 2011 33 | Cross‐sectional | Drug testing, Written workplace policy | USA | All | 2249 | National survey | Misuse of prescription pain relievers (self‐report) | Poor |

| Sturm 2000 48 | Retrospective cohort study | Restructuring of Employee Health Benefit Plans | USA | Not specified | 408 663 person‐years (1 142 273 member‐years including dependents) | 49 employers | Substance abuse treatment utilization and cost: inpatient and outpatient (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Combined Interventions | ||||||||

| Lockwood 1998 36 | Time‐series quasi‐experimental | EE + Drug testing + EAP + Supervisor training + written workplace drug‐free policy, EE + Drug testing + Supervisor training + written workplace drug‐free policy | USA | Hotel | >2340 | 5 hotels | Absenteeism, Injuries, Health insurance claims, Productivity, (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Gómez‐Recasens 2018 32 | Non‐randomized single arm study | Employee education + random/suspected use/post‐accident drug testing | Spain | Construction | 1103 | 12 work centers | Risky drug use (saliva drug test) | Fair |

| Miller 2007 40 | Controlled interrupted time series | Employee Education + EAP + Random drug testing) | USA | Transportation | Not reported | Injury rates, Cost of injuries | Fair | |

| Spicer 2005 47 | Controlled interrupted time series | Employee education + Random drug testing | USA | Transportation | Not reported | 5 companies | Injury rate (routinely collected reports) | Poor |

| Wickizer 2004 51 | Retrospective cohort study | Written workplace policy + Drug testing + EAP + Employee education | USA | Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing, Mining, Construction, Manufacturing, Transportation and Public Utilities, Wholesale and Retail Trade, Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate, Services | Not reported | 261 intervention companies and 20 215 control companies | Injury rate (routinely collected data) | Fair |

| Pidd 2016 44 | Cross‐sectional |

Written workplace policy + Drug testing, Assistance with drug use + Employee education, Written workplace policy + Drug testing + Assistance with drug use |

Australia | National population‐based survey | 13 590 | National survey | Illicit drug use (self‐report) | Poor |

Abbreviations: EAP, employee assistance program, OSHA, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, USA, United States of America.

3.3. Quality of studies

All of the included studies were rated either fair or poor, with scores ranging from 8/28 to 19/28 (Table 2). None of the studies met the threshold for “excellent” or “good” quality, based on the modified Downs and Black criteria. 20 The majority of the studies (18; 66.7%) had total scores within the range for “fair quality,” while the remaining nine fell within the “poor quality” range. Of the four RCTs, two had scores within the “poor quality” range, 25 , 28 and the remaining two had scores within the “fair quality” range. 29 , 43 In general, the weakness in quality scores reflects poor scores for internal validity (high risk of bias or unmeasured confounders) and power estimation.

TABLE 2.

Risk of Bias assessment of included studies based on the Downs and Black tool

| Study ID | Score | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporting | External validity | Internal validity‐bias | Internal validity‐Confounding | Power | Total | Quality | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Question number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | ||

| Brochu 1988 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | Fair |

| Carpenter 2007 26 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | Poor |

| Castro 2000 27 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | Poor |

| Cook 2000 28 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | Poor |

| Cook 2004 29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | Fair |

| Feinauer 1993 30 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 16 | Fair |

| French 2004 31 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Gómez‐Recasens 2018 32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | Fair |

| Lee 2011 33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | Poor |

| Lockwood 1998 36 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 18 | Fair |

| Lockwood 2000 35 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | Poor |

| LoSasso 2004 34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 16 | Fair |

| Marques 2014 37 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 | Fair |

| Messer 1996 38 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Miller 2007 40 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 16 | Fair |

| Miller 2015 39 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | Poor |

| Morantz 2008 41 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 17 | Fair |

| Ozminkowski 2003 42 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Patterson 2005 43 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | Fair |

| Pidd 2016 44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | Poor |

| Schofield 2013 45 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 | Fair |

| Shepard 1998 46 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | Poor |

| Spicer 2005 47 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 | Poor |

| Sturm 2000 48 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Sweeney 1995 49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 18 | Fair |

| Waehrer 2016 50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | Fair |

| Wickizer 2004 51 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 18 | Fair |

3.4. Effectiveness of Interventions

Because some studies evaluated multiple interventions or outcomes, we identified 49 independent analyses of the effectiveness of recommended workplace interventions. A summary of the effectiveness of the interventions is provided in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Effectiveness of Workplace interventions for misuse of opioids and related drugs

| Outcomes | Studies | Study design | Results | Comments |

Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Intervention: employee education | |||||

| Illicit drug use | Brochu 1988 25 | Randomized‐controlled trial | Self‐reported marijuana or hashish use in the last 12 mo: Intervention 32%, Control 23% (variance = 0.05 and 0.02, respectively), t = 0.24; P > .01 | Education did not result in the reduction of illicit drug use. | Fair |

| Carpenter 2007 26 | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported marijuana use in the last 30 d: aOR 0.791, SE 0.048, P < .01 | 21% lower odds of marijuana use. | Poor | |

| Cook 2000 28 | Randomized‐controlled trials |

Self‐reported illicit drug use: Pre‐Intervention:16 using illicit drugs Post‐test 1:5/16, McNemar test P = .02 Post‐test 2:2/9, McNemar test P = NS |

Data only presented for intervention group. Stress management education led to significant reduction in the use of illicit drugs in the short term (1 mo), but not long term (10 mo) | Poor | |

| Cook 2004 29 | Randomized‐controlled trial | Self‐reported illicit drug use in the past 30 d: Intervention 6%, Control 14% (χ 2 = 2.32, P = .128) | Education did not result in the reduction of illicit drug use | Fair | |

| Miller 2015 39 | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported non‐medical prescription drug use in the last 30 d: aOR 0.98; 95% CI 0.85‐1.14, P = .834 | No association between education and drug misuse | Fair | |

| Patterson 2005 43 | Randomized‐controlled trial |

Likelihood to use over the counter drug to relax (Likert scale: 1‐5): Mean comparison, pre‐, and post‐intervention: Intervention 1:Pre 2.20, post 2.29; Intervention 2: Pre 2.30, post 2.15; Control: Pre 2.37, Post 2.26 ANOVA, F = 1.92, P > .05 |

Education did not result in the reduction of illicit drug use | Fair | |

| B. Intervention: drug testing | |||||

| Illicit drug use | Carpenter 2007 26 | Cross‐sectional |

Self‐reported marijuana use in the last 30 d: (AOR 0.697, SE 0.050) P < .01) |

31% lower odds of marijuana use | Poor |

| French 2004 31 | Cross‐sectional |

Any drug use: 1. Any drug testing: β = −0.31, SE 0.06, P < .01 2. Suspicion‐based: β = −0.35 SE 0.08, P < .01 3. Random: β = −0.38, SE 0.10 P < .01 |

Lower rate of illicit drug use among employees at worksites with any drug testing, random drug testing or suspicion‐based drug‐testing program | Fair | |

| Lee 2011 33 | Cross‐sectional |

Misuse of prescription pain relievers. Any drug testing: β = 0.2, SE 0.22 P = NS |

No association between drug testing and misuse of prescription pain relievers | Poor | |

| Messer 1996 38 | Retrospective cohort study |

Positive results on drug test: Non‐random drug test: Year 1 2.6%, Year 2:1.6%, Year 3 1.4%; 1.2% decline in year 3 compared to year 1. Random drug test: Year 1 2.3%, Year 2:2.1%, Year 3:1.5%, 0.8% decline in Year 3 compared to Year1 |

Introduction of random drug testing did not lead to a significant decline in positive drug tests compared to non‐random tests | Fair | |

| Miller 2015 39 | Cross‐sectional | Non‐medical prescription drug use in the last 30 d: aOR, 0.92, 95% CI 0.78‐1.07, P = .276 | No association between drug testing and drug misuse | Fair | |

| Work‐related Injuries | Feinauer 1993 30 | Retrospective cohort study |

OSHA reportable accidents over 5 y: Any Drug testing: β = −1.220, SE −0.068, t: −0.509, df: 43, P: NS) Post‐accident drug testing: β = −2.823, SE −0.225, t: −2.792, P < .01) Reasonable cause drug testing: β = −0.163, SE: −0.014, t: −0.115, P > .05 |

Post‐accident drug testing was effective in reducing workplace accidents Any drug test or reasonable cause drug testing did not reduce accident rates |

Fair |

| Lockwood 2000 35 | Interrupted time series (no control) |

OSHA reportable accidents: Pre‐employment drug test vs. pre‐employment + Random drug test. Pre‐intervention slope = 0.21 Post‐intervention slope = −0.04 Change in slope = t test = −2.70, P < .01 |

Introduction of random drug testing led to a reduction in OSHA reportable accidents | Poor | |

| Marques 2014 37 | Retrospective cohort study |

Workplace accidents: Untested employees: 47.0% Random drug test: 19.4% Adjusted P < .001 |

Employees randomly selected for drug testing were less likely to have workplace accidents following the test, compared to untested employees | Fair | |

| Messer 1996 38 | Retrospective cohort study |

Mean accidents rates/1 000 000 miles: Random drug test: 1.5%, Non‐random drug test: 1.9%, P = NS Passenger injury rates/100 000 miles: Random drug test: 3.9%, non‐random drug test: 5.2%, t (62) = 1.85, P = .045 |

A change from non‐random to random drug test led to a decline in passenger injuries, but not overall accidents | Fair | |

| Ozminkowski 2003 42 | Interrupted time series (No control) |

Regression odds of a workplace accident: aOR: −0.5856; P = .0532 |

Random drug testing led to lower accident rates, but the change was not statistically significant | Fair | |

| Schofield 2013 45 | Retrospective cohort study |

All workplace injuries: No program versus pre‐employment/post‐accident: RR = 0.85, CI = 0.72‐1.0, P = NS No program versus pre‐employment/post‐accident/random/suspicion: RR = 0.97 95% CI = 0.86‐1.10), P = NS |

Drug testing was not associated with a significant reduction in workplace injuries | Fair | |

| Waehrer 2016 50 | Cross‐sectional |

No work lost injuries: IRR 0.859, SE 0.062, P < .01 Injuries resulting in job loss: IRR 0.92, SE 0.054, P = NS |

Drug testing was associated with a reduction in injuries that did not result in loss of work, but not injuries that resulted in work loss | Fair | |

| Healthcare Cost | Morantz 2008 41 | Controlled interrupted time series |

Total worker compensation claims: aOR = −0.123, SE 029, P < .01 |

Introduction of drug testing led to a significant decline in total worker compensation claims | Fair |

| Ozminkowski 2003 42 | Interrupted time series (No control) |

Any substance abuse or related expenditure: aOR = −1.0356, P = .3504 |

Random drug testing did not lead to a reduction in substance abuse or related expenditure | Fair | |

| Productivity | Shepard 1998 46 | Cross‐sectional |

Productivity: Log sales/employee Any drug testing:regression coefficient: −0.192, SE 0.077, P < .01 Pre‐employment drug test: regression coefficient: −0.16, SE 0.082, P < .05 Random drug test: regression coefficient: −0.285, SE 127, P < .02 |

Any form of drug testing was associated with a 19% reduction in productivity. Pre‐employment and random drug testing was associated with a 16% and 29% reduction in productivity, respectively | Poor |

| C. Employee Assistant Programs | |||||

| Illicit drug use | Carpenter 2007 26 | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported marijuana use in the last 30 d: aOR 1.01, SE 0.064, P > .05 | No association between EAP and illicit drug use | Poor |

| Miller 2015 39 | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported non‐medical prescription drug use: aOR 0.85, 95% CI 0.72‐1.00, P = .047 | EAP was associated with 15% lower non‐medical prescription drug use | Fair | |

| Work‐related Accident | Castro 2000 27 | Historically controlled trial |

Number of Accidents: Mean number of accidents‐ Pre‐EAP: 2.22, SD 1.9 Post‐EAP: 1.0 (SD 1.32) Mean difference; −1.21 (SD 2.49), t‐value = −2.79; P = .009 |

Introduction of EAP led to a significant reduction in the number of workplace accidents | Poor |

| Waehrer 2016 50 | Cross‐sectional |

Injuries with no loss of work: IRR 0.867, SE 0.063, P < .01 Injuries with work loss: IRR 0.923, SE 0.056, P = NS |

EAP was associated with a reduction in injuries that resulted in no loss of work, but not injuries that resulted in work loss | Fair | |

| Healthcare Cost | Castro 2000 27 | Historically controlled trial |

Workers compensation claims in dollars: Pre‐EAP: 6041.17 (SD: 8705.50) Post‐EAP: 2523.59 (SD: 17 339.19), mean diff: −3517.59 (SD: 3525.04) P = .326 |

Introduction of EAP did not lead to a reduction in total worker compensation claims | Poor |

| Sweeney 1995 49 | Controlled interrupted time series |

Mental health/chemical dependency claim/costs: EAP user‐non‐user claims: n = 45 pairs, mean difference = −0.05, P = .7217 EAP user‐non‐user, cost (dollars), mean difference: n = 45 pairs, x = −26.55, P = .515 |

EAP did not result in a significant change in mental health/chemical dependency claims or costs | Fair | |

| Absenteeism | Castro 2000 27 | Historically controlled trial |

Sick leaves hours: pre‐EAP: 177.84, Post‐EAP: 64.62, diff: 113.22, SD: 417.757, P = .164 |

Introduction of EAP did not lead to a significant reduction in absenteeism due to sick leaves | Poor |

| D. Written workplace drug‐free policy | |||||

| Illicit drug use | Carpenter 2007 26 | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported marijuana use in the last 30 d: aOR 0.697, SE 0.050, P < .01) | Written policy associated with 31% lower self‐reported marijuana use | Poor |

| Lee 2011 33 | Cross‐sectional |

Misuse of prescription pain relievers. Any drug testing: β = 0.2 (0.22) P = NS |

No association between workplace policy and misuse of prescription pain relievers | Poor | |

| Miller 2015 39 | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported non‐medical prescription drug use: (AOR 0.85, 95% CI 0.73‐1.00, P = .045) | Written policy associated with 15% lower non‐medical prescription drug use | Fair | |

| Pidd 2016 44 | Cross‐sectional |

Use of illicit drugs in the last 12 mo. AOR, 1.0, 95% CI 0.81‐1.24, P = .98 |

No association between workplace policy and use of illicit drugs | Poor | |

| Work‐related injuries | Waehrer 2016 50 | Cross‐sectional |

No work lost injuries: IRR 1.066, SE 0.075, p = NS Injuries with work loss: IRR 1.043, SE 0.043, P = NS |

A written drug‐free workplace policy was not associated with a reduction in workplace injuries | Fair |

| E. Restructuring employee health benefits | |||||

| Healthcare cost | Sturm 2000 48 | Retrospective cohort study |

Cost of substance abuse care: Fully managed Behavioral Health organization versus cost‐sharing with workplace: Cost of out‐patient care: regression coefficient = 0.428, P < .01 Cost of in‐patient care: regression coefficient = −0.101, P = NS |

The total cost of out‐patient, but not in‐patients care was lower in organizations that fully contracted out management of substance abuse treatment to Managed Behavioral Health Organizations | Fair |

| Healthcare utilization | Lo Sasso 2004 34 | Retrospective cohort study |

Out‐patient visit utilization: Regression coefficient: −0.069, SE 0.031 P < .05 Inpatient treatment days: Regression coefficient: −0.016, SE 0.012, P < .0 |

Increase in co‐payment level was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the number of outpatient and in‐patient treatment visits | Fair |

| Sturm 2000 48 | Retrospective cohort study |

Access to substance abuse care: Fully managed Behavioral Health organization vs cost sharing with workplace: Access to care: OR = 1.13, P = NS |

No difference in access to care for employees in organizations that fully contracted out management of substance abuse treatment to Managed Behavioral Health Organizations compared to those who did not | Fair | |

| F. Combined interventions | |||||

| Illicit drug use | Gómez‐Recasens 2018 32 | Non‐randomized single‐arm study (EE + Drug testing) |

Illicit drug use, saliva drug test (Drager drug test) Baseline: 75/1103 (6.8%) Year 1:65/990 (6.6%); baseline vs Year 1, P = .332 Year 2:47/700(6.7%); baseline vs Year 2, P = .143 Year 3:43/625 (6.9%) baseline vs Year 3, P = .108 Year 1 vs Year 2: P = .039 Year 2 vs Year 3:P = .754, |

There was a significant decline in illicit drug use in year 2 compared to year 1, but not at any other time interval | Fair |

| Pidd 2016 44 | Cross‐sectional (Written workplace drug‐free policy ± drug testing) |

Self‐reported use of illicit drugs in the last 12 mo: aOR, 0.99, 95% CI 0.72‐1.36, P = .95 |

No association between workplace policy ± drug testing and use of illicit drugs | Poor | |

| Pidd 2016 44 | Cross‐sectional (written workplace drug‐free policy + EE or EAP) |

Self‐reported use of illicit drugs in the last 12 mo: aOR, 0.90, 95% CI 0.69‐1.18, P = .46 |

No association between Written workplace policy + EE or (EAP and the use of illicit drugs | Poor | |

| Pidd 2016 44 | Cross‐sectional (EE + drug testing + Written workplace drug‐free policy ± EAP) |

Self‐reported use of illicit drugs in the last 12 mo. aOR, 0.72, 95% CI 0.53‐0.98, P = .04 |

A comprehensive policy was associated with 28% lowers odds of illicit drug use | Poor | |

| Work‐related injuries | Spicer 2005 47 | Controlled Interrupted time‐series analysis (EE + EAP) |

Workplace injuries rates: aRR, 0.9984; 95% CI, 0.9975‐0.9994 |

The combined intervention led to modest (1%) but significant reduction in workplace injuries | Poor |

| Miller 2007 40 | Controlled interrupted time series (EE + EAP + Drug testing) |

Injuries: Injuries avoided: 824‐849, P = .035‐.040 |

The combined intervention led to significant reduction in workplace injuries | Fair | |

| Wickizer 2004 51 | Retrospective cohort study (EE + Drug testing + EAP + Supervisor training + Written workplace drug‐free policy) |

Injury rates per 100 person‐years (Intervention‐comparison companies): Pre‐intervention = 12.13, 95% CI 11.59‐12.67) During Intervention = 8.80, 95% CI 8.36‐9.23, P < .05), Post‐Intervention = 7.36 95% CI 6.44‐8.29, P < .05 |

Organizations that adopted the combined policy experienced a greater decline in workplace injuries (3.3/100 person years) | Fair | |

| Lockwood 1998 36 | Interrupted time‐series analysis |

Workplace accidents: Slope Pre‐intervention = −0.01 Post‐intervention = −0.01 Change in slope: t(99) = 0.03, P = .976 |

The combined program did not lead to significant reduction in workplace accidents | Fair | |

| Healthcare Cost | Lockwood 1998 36 | Interrupted time‐series analysis (EE + Drug testing + EAP + Supervisor training + Written workplace drug‐free policy) |

Health insurance claims: Slope Pre‐intervention = 3.04 Post‐intervention = 1.57 Change in slope: t(50) = −0.55, P = .59 |

The introduction of the combined intervention did not lead to a reduction in health insurance claims | Fair |

|

Miller 2007 40 (EE + EAP + drug testing) |

Controlled interrupted time series |

Injury costs avoided in 1999 (millions of $): 32.7‐33.3, P < .01 |

The combined intervention led to a reduction in the cost of workplace injuries | Fair | |

| Absenteeism | Lockwood 1998 36 |

Interrupted time‐series analysis ( EE + Drug testing + EAP + Supervisor training + Written workplace drug‐free policy) |

Absenteeism: Slope Pre‐intervention = 1.05 Post‐intervention = −0.94 Change in slope: t(61) = −1.79, P = .08 |

The combined program did not lead to a significant reduction in absenteeism | Fair |

| Productivity | Lockwood 1998 36 | interrupted time‐series analysis (EE + Drug testing + EAP + Supervisor training + Written workplace drug‐free policy) |

Productivity: Slope Pre‐intervention = 3.67 Post‐intervention = −3.04 Change in slope: t(102) = −1.06, P = .29 |

The combined program did not lead to a significant change in productivity | Fair |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; aRR, adjusted relative risk; CI, confidence Interval; df, degrees of freedom; EAP, employee assistance program; EE, Employee education; IRR, incidence rate ratio; NS, not statistically significant; OSHA, Occupational Safety and Health Administration of the United; RR, relative risk; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

3.4.1. Employee education

All six evaluations of employee education investigated its effectiveness in reducing employee drug use. Two studies reported a significant reduction in illicit drugs among employees exposed to an educational intervention, 26 , 28 while four studies did not find this intervention to be effective. 25 , 28 , 29 , 43 Three 25 , 28 , 29 , 43 of four analyses of RCTs did not find a stand‐alone educational intervention to be effective. Although the fourth RCT 28 suggested that employee education may lead to a reduction in illicit drug use, the analysis for this outcome lacked methodological rigor. The two remaining studies were analyses of the National Household Surveys on Drug Abuse (NHSDA). 26 , 39 One of these studies reported that respondents who endorsed the presence of workplace drug prevention messages were less likely to self‐report marijuana use in 30 days preceding the survey, 26 while the other did not find an association between workplace education on drug use and self‐reported non‐prescription drug use. 39 Both studies that suggested that employee education alone was sufficient to reduce drug use 26 , 28 had low‐quality assessment scores.

3.4.2. Drug testing

In all, 15 studies evaluated the effectiveness of random, reasonable suspicion, or post‐accident drug testing in the workplace. The most frequent outcome was work‐place injuries. 30 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 42 , 45 , 50 Five studies investigated the relationship between drug testing and illicit drug use or misuse of prescription drugs, 26 , 31 , 33 , 38 , 39 while two investigated the association between drug testing with healthcare cost. 41 , 42 One study examined the association between drug testing and productivity. 46

Two of five studies reported that drug testing was associated with a reduction in drug misuse. Both were cross‐sectional studies, with poor 26 or fair 31 quality assessment. Study outcomes were self‐reported marijuana use 26 or any illicit drug use. 31 The three other studies did not find any relationship between drug testing and illicit drug use. Two of these were cross‐sectional studies 33 , 39 in which no association was found between drug testing and misuse of prescription pain relievers 33 or non‐medical prescription drug use. 39 A third study, which analyzed data of a retrospective cohort 38 did not detect a significant decline in positive urine tests for cocaine and marijuana in a company that switched from non‐random to random drug testing.

Seven studies investigated the association between drug testing and workplace accidents, and two of these studies 35 , 37 reported that drug testing was associated with a decline in workplace injuries. In the first of these two studies, the introduction of random drug testing in a company with pre‐employment drug testing led to a significant decline in workplace injuries, 35 while in the second study, workers randomly selected for drug testing had lower post‐test accident rates when compared to employees who had not had drug testing. 37 Three studies reported mixed results, indicating that only specific drug‐testing modalities were effective, 30 or that drug testing was effective for reducing some but not all types of work‐related accidents. 38 , 50 In one of these studies, post‐accident drug testing resulted in a decline in Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reportable accidents, but reasonable cause drug testing did not have the same effect. 30 In another study, a switch from non‐random to random drug testing led to a decline in passenger injuries, but not overall accidents among employees in the transport industry. 38 Lastly, in the study by Waehrer et al, 50 an association was found between drug testing and injuries resulting in no loss of work, but not injuries associated with loss of work.

In two studies, employee drug testing did not result in a significant reduction in workplace accidents. In one of these studies, there was no significant decline in workplace accidents following the introduction of random drug testing, 42 while in the other study a combination of pre‐employment and post‐accident and a combination of pre‐employment, post‐accident, random, and suspicion‐based drug testing did not lead to a significant decline in workplace injuries when compared to no drug‐testing program. 45 Both studies had fair quality assessment ratings.

Two studies investigated the effect of drug testing on healthcare costs. While Morantz and Mas 41 showed that the adoption of drug testing resulted in a 12% decline in total health claims, Ozminkowski et al 42 did not find a decline in substance abuse‐related expenditure. Both studies had similar study designs and quality assessment scores. In the only study that investigated the relationship between drug testing and productivity, 46 any drug testing or specifically random drug testing was associated with a reduction in productivity. The quality of this study was poor, so its findings should be interpreted with caution.

3.4.3. Employee assistance programs

Five studies provided seven evaluations of the effect of EAPs on illicit drug use, work‐related injuries, healthcare costs, or absenteeism. The study by Castro and Lawson, 27 reported three outcomes: work‐related accidents, healthcare cost, and absenteeism, but had a low‐quality assessment score. Two studies investigated the effect of EAPs on the use of illicit drugs, and one 39 reported an association between having an EAP and reduced marijuana use, while the other, 26 with a poor quality score, did not find an independent association between having an EAP program and drug misuse. Both studies were cross‐sectional studies of national surveys, with self‐reported outcomes of marijuana use 26 or non‐medicinal prescription drug use. 39

Two studies evaluated the effect of EAPs on workplace accidents. While the study by Castro and Lawson 27 showed that the introduction of an EAP program led to a significant decline in workplace injuries, the study by Waehrer et al 50 reported mixed results, and showed an association between EAPs and injuries that resulted in “no loss of work,” but not injuries with “work loss.” The study designs were different: Castro and Lawson 27 conducted a historically controlled trial, while Waehrer et al 50 carried out a cross‐sectional study.

None of the two studies that investigated the effectiveness of EAPs in reducing healthcare costs found it to be effective. Sweeney and colleagues 49 used a matched design to compare manufacturing companies with and without EAPs and did not find a significant difference in the number of claims or the dollar amount of claims between companies with EAPs and those without. Lastly, another analysis in the study by Castro and Lawson 27 did not show an association between an EAP and total worker compensation claims. There was only one analysis of the effect of an EAP program on absenteeism due to sick leave, and this was reported in the study by Castro and Lawson. 27 In the cross‐sectional analysis, no association was found between EAPs and absenteeism due to sick leave.

3.4.4. Written drug‐free workplace drug policy

Four 26 , 33 , 39 , 44 of five studies, all cross‐sectional, investigated the association between a written workplace drug‐free policy and misuse of drugs. Two of these studies reported lower drug misuse (marijuana 26 or prescription medications 39 ), while the other two found no association between written workplace drug‐free policies and misuse of prescription pain relievers 33 or any illicit drugs. 44 Three of the four studies were of poor quality, 26 , 33 , 44 while the fourth had fair quality.

One study, also cross‐sectional in design, investigated if there was an association between a written workplace drug‐free policy and work‐related injuries, 50 and found no association between written drug‐free policy and injuries resulting in loss of work or no‐work‐loss injuries.

3.4.5. Restructuring employee health benefits

Three independent analyses from two retrospective cohort studies, all of fair quality, evaluated the impact of restructuring health benefits on healthcare cost 48 or utilization. 34 , 48 Analyzing health insurance data, Sturm 48 compared different health insurance plans provided by the same managed health organization but differed in terms of coverage‐fully ensuring contracts versus not. Plans that provided full coverage risk did not have significantly different access rates for any care or any inpatient care. In terms of cost, plans that provided full health coverage were associated with lower out‐patient, but not in‐patient cost.

The second study by Lo Sasso and Lyons 34 evaluated the impact variation of co‐pay on health services related to employee drug use. The study reported that higher co‐payments were associated with reduced utilization of out‐patient and in‐patient services for patients with drug use problems, 34 thus having a negative effect on access to care.

3.4.6. Combined interventions

In all, 12 analyses evaluated the effectiveness of a combination of two or more recommended interventions on various work‐related outcomes. Four analyses from two studies had outcomes of drug misuse. 32 , 44 One showed that it may be effective, 44 one had mixed results, 32 while the remaining two indicated that it was not effective. 44 Pidd et al, 44 in a cross‐sectional survey, evaluated various combinations of interventions and reported that the combination of employee education, drug testing, written workplace drug‐free policy, with or without EAP, was associated with a 28% lower odds of self‐reported illicit drug use. In the same study, no association was found between the combination of written workplace drug‐free policy and employee education or EAP, or the combination of written workplace drug‐free policy with or without drug testing, and illicit drug use. The quality of this study was, however, poor.

In a single‐arm study, Gómez‐Recasens et al 32 examined changes in the yearly proportion of positive saliva drugs screen over 3 years following the introduction of employee education and drug testing. There was a significant decline in year two compared to year one, but not at any other time intervals.

Three 40 , 47 , 51 of four studies reported that a combination of interventions reduced workplace injuries or accidents. The results of a controlled interrupted time‐series analysis 47 showed a modest but significant decline in workplace injuries after employee education and EAP were introduced to a transportation company. The quality of the study was however poor. In the two other studies, reduction in workplace injuries was reported by Miller et al 40 and Wickizer et al 51 in response to the combination of employee education, drug testing, and EAP, or the combination of employee education, drug testing, EAP, supervisor training, and written workplace drug‐free policy, respectively. However, the study by Lockwood et al 36 did not detect a reduction in workplace accidents after the introduction of a comprehensive policy of employee education, drug testing, EAP, supervisor training, and written workplace drug‐free policy.

Other reported outcomes of combined interventions were healthcare costs, 36 , 40 absenteeism, 36 and productivity. 36 Of these, only the study by Miller et al 40 reported a positive outcome, with the combination of employee education, drug testing, and EAP, resulting in a significant decline in the cost attributable to workplace injuries.

4. DISCUSSION

We have provided an updated, systematic assessment of the effectiveness of currently recommended interventions for employers to prevent or reduce the adverse effects of opioids and related drugs. Building on previous reviews, 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 we adopted a systematic approach and included all currently recommended interventions to insulate employees from drug use, and included all outcomes we considered will be important to both employers and employees. However, similar to what was observed in previous reviews, most of the studies were methodologically weak, providing a poor evidence base to access the efficacies of these interventions.

In light of the opioid epidemic and increasing legalization of marijuana, 52 the rising incidence of substance use disorders and its impact on the workforce is a serious concern. 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 Yet, of the 27 studies identified in this research, only seven were published in the past decade. Of these seven, four were cross‐sectional analyses of national survey data. Of the three remaining studies from the past decade, when the effects of the crisis were first being detected, only one study was based in the United States. 45 Coincidently, this study has the highest quality assessment score of all 27 publications. Unfortunately, this single piece of recent evidence is not particularly useful guidance for employers. The mixed results of this review may be disappointing to employers looking for clear guidance on interventions to adopt to address substance use. Overall, our findings suggest that the interventions may work in some contexts, but not others, which highlights the need for mixed methods evaluations of employer‐led interventions. Such studies would provide evidence about the contexts in which the interventions are more likely to succeed.

Despite these shortcomings, the results from the identified studies indicate that work‐related injuries or accidents may be more sensitive to the effects of the evaluated workplace interventions. Three 40 , 47 , 51 of four combined interventions with outcomes of work‐related injuries reported a significant decline in injuries. Five 30 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 50 of seven studies reported that drug testing might reduce workplace injuries, and both studies that evaluated the impact of EAP 27 , 50 reported lower accidents associated with EAP. Outcome data related to workplace injuries may also be more reliable than data on drug use as the former may be pulled from standard documentation required by OSHA, and the latter from self‐reports.

In response to the opioid epidemic, our goal was to provide a comprehensive review of the effectiveness of interventions that employers can deploy to mitigate the adverse workplace effects of opioids. Despite our efforts to achieve this goal, the limitations of our review need to be considered. Because of the variations in study designs, effect measures, and outcomes, we were unable to conduct a meta‐analysis. However, given the poor quality of identified studies, this may not have a significant effect on the overall conclusions. Also, our choice for the Downs and Black was based on its rigor in assessing the quality of both RCTs and non‐RCTs and its wide use. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Using a different tool may have produced different results related to study quality. Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive synthesis of the effectiveness of currently recommended interventions that can be instituted by employers for addressing substance misuse in the workforce.

We suspect that many employers have implemented the interventions described here, 6 but few employers may have evaluated and published the results. It is not surprising, given that these research activities are not central to the core business of most employers and that many employers might not be familiar with conducting and publishing rigorous research. There is an opportunity for employer‐researcher partnerships to help with evaluations of these employer‐led interventions. Researchers may help employers identify interventions, evaluate interventions, and bridge the gap between what is known and what is practiced. There is also the potential for greater partnerships between public health agencies and large employers in efforts to prevent and reduce substance use disorders. Large employers have a financial incentive to reduce substance abuse in their workers. They also have the opportunity to reach large numbers of people both by intervening directly with their employees and indirectly through the families and dependents of their employees. Future partnerships between large employers and researchers could strengthen the knowledge base about effective interventions and guide other employers to help their workforce.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our systematic review found no rigorous evaluations of employer‐led efforts to prevent or reduce the ill effects of substance abuse disorder. As a result, there are limited evidence‐based strategies for employers to consider for addressing substance use. More employer‐led experimentation, employer‐researcher and employer‐public health partnerships, and mixed methods evaluations may help to expand the evidence base. Based on the available evidence, recommended interventions may reduce workplace injuries, but require more rigorous confirmatory research.

DISCLOSURE

Approval of the research protocol: N/A. Informed consent: N/A. Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: The review protocol is registered in the International prospective register of systematic reviews, PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42019132681); Animal studies: N/A; Conflict of interest: All authors declare no competing interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MCM was responsible for conceptualization. All authors were involved in the study design. MOA, LCM, CBI, and ASR were responsible for data extraction, while all authors were involved in data analysis. MOA, LCM, and CBI were responsible for writing the initial draft of the manuscript, and all authors were involved in reviewing and editing.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Akanbi MO, Iroz CB, O'Dwyer LC, Rivera AS, McHugh MC. A systematic review of the effectiveness of employer‐led interventions for drug misuse. J Occup Health. 2020;62:e12133 10.1002/1348-9585.12133

REFERENCES

- 1. Jones MR, Viswanath O, Peck J, Kaye AD, Gill JS, Simopoulos TT. a brief history of the opioid epidemic and strategies for pain medicine. Pain Ther. 2018;7(1):13‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid‐involved overdose deaths ‐ United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50–51):1445‐1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid‐involved overdose deaths ‐ United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419‐1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goplerud E, Hodge S, Benham T. A substance use cost calculator for US employers with an emphasis on prescription pain medication misuse. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(11):1063‐1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kowalski‐McGraw M, Green‐McKenzie J, Pandalai SP, Schulte PA. Characterizing the interrelationships of prescription opioid and benzodiazepine drugs with worker health and workplace hazards. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(11):1114‐1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration US Department of Health and Human Services . Drug‐Free Workplace Toolkit. 2019; https://www.samhsa.gov/workplace/toolkit. Accessed 9/6/2019

- 7. Gerber JK, Yacoubian GS Jr. An assessment of drug testing within the construction industry. J Drug Educ. 2002;32(1):53‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zwerling C. Current practice and experience in drug and alcohol testing in the workplace. Bull Narc. 1993;45(2):155‐196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kraus JF. The effects of certain drug‐testing programs on injury reduction in the workplace: an evidence‐based review. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2001;7(2):103‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Drug Use in the Workplace , Normand J, Lempert RO, O'Brien CP, eds. Under the Influence?: Drugs and the American Work Force. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Macdonald S, The WS. Impact and Effectiveness of Drug Testing Programs in the Workplace In: Macdonald S, Roman P, eds. Drug Testing in the Workplace. Research Advances in Alcohol and Drug Problems. Vol 11. Boston, MA: Springer; 1994:121‐142. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cashman CM, Ruotsalainen JH, Greiner BA, Beirne PV, Verbeek JH. Alcohol and drug screening of occupational drivers for preventing injury. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2009(2):CD006566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frone MR. Alcohol and Illicit Drug Use in the Workforce and Workplace Quick JC. Tetrick LE. Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Society; 2013:277‐296. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pidd K, Roche AM. How effective is drug testing as a workplace safety strategy? A systematic review of the evidence. Accid Anal Prev. 2014;71:154‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vrabel M. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(5):552‐554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Substance Abuse Program Administrators Association. Drug‐Free Worlplace. 2019; https://www.sapaa.com/mpage/wp_dfwp. Accessed 6/6/2019 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grigsby TJ, Howard JT. Prescription opioid misuse and comorbid substance use: Past 30‐day prevalence, correlates and co‐occurring behavioral indicators in the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Addic. 2019;28(2):111‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Survey on Drug Use and Health . Trends in Prevalence of Various Drugs for Ages 12 or Older, Ages 12 to 17, Ages 18 to 25, and Ages 26 or Older; 2015–2017 National Survey of Drug Use and Health. 2019; https://www.drugabuse.gov/national‐survey‐drug‐use‐health. Accessed 04/05/2019 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Babineau J. Product Review: Covidence (Systematic Review Software). 2014;35(2):4 https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/jchla/article/view/22892/17064. Accessed: 22018‐22810‐22804. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/22872vOKXHeV). https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/jchla/article/view/22892/17064. Accessed 2014‐08‐01 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non‐randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377‐384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dehon E, Weiss N, Jones J, Faulconer W, Hinton E, Sterling S. A systematic review of the impact of physician implicit racial bias on clinical decision making. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(8):895‐904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huffer D, Hing W, Newton R, Clair M. Strength training for plantar fasciitis and the intrinsic foot musculature: a systematic review. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;24:44‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Masaracchio M, Hanney WJ, Liu X, Kolber M, Kirker K. Timing of rehabilitation on length of stay and cost in patients with hip or knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review with meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hooper P, Jutai JW, Strong G, Russell‐Minda E. Age‐related macular degeneration and low‐vision rehabilitation: a systematic review. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43(2):180‐187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brochu S, Souliere M. Long‐term evaluation of a life skills approach for alcohol and drug abuse prevention. J Drug Educ. 1988;18(4):311‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carpenter CS. Workplace drug testing and worker drug use. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):795‐810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Castro MA, Lawson G. The Effectiveness of Chemical Dependency Rehabilitation Treatment Provided by an Employee Assistance Program. Ann Arbor: Psychology and Graduate Studies, United States International University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cook RF, Back AS, Trudeau J, McPherson T. Integrating Substance Abuse Prevention into Health Promotion Programs in the Workplace: A Social Cognitive Intervention Targeting the Mainstream User Bennett JB. Lehman WEK. Preventing Workplace Substance Abuse: Beyond Drug Testing to Wellness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000:97–133. 10.1037/10476-003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cook RF, Hersch RK, Back AS, McPherson TL. The prevention of substance abuse among construction workers: a field test of a social‐cognitive program. J Prim Prev. 2004;25(3):337‐357. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Feinauer DM, Havlovic SJ. Drug testing as a strategy to reduce occupational accidents: a longitudinal analysis. J Safety Res. 1993;24(1):1‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 31. French MT, Roebuck C, Alexandre PK. To test or not to test: do workplace drug testing programs discourage employee drug use? Soc Sci Res. 2004;33(1):45‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gómez‐Recasens M, Alfaro‐Barrio S, Tarro L, Llauradó E, Solà R. A workplace intervention to reduce alcohol and drug consumption: a nonrandomized single‐group study 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee D, Ross MW. Management of human resources associated with misuse of prescription drugs: analysis of a national survey. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2011;34(2):182‐205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lo Sasso AT, Lyons JS. The sensitivity of substance abuse treatment intensity to co‐payment levels. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31(1):50‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lockwood FS, Klass BS, Logan JE, Sandberg WR. Drug‐testing programs and their impact on workplace accidents: a time‐series analysis. J Indiv Employ Rights. 2000;8(4):296‐306. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lockwood FS, Logan JE, Klaas BS. The effect of drug‐free workplace programs on employee behavior. 1998(9841743):296. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marques PH, Jesus V, Olea SA, Vairinhos V, Jacinto C. The effect of alcohol and drug testing at the workplace on individual's occupational accident risk. Saf Sci. 2014;68:108‐120. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Messer DC. An empirical evaluation of the legal assumptions underlying workplace‐based drug and alcohol testing: results from a comparison of random and non‐random testing programs at a large transportation agency. 1996(9630563):167.

- 39. Miller T, Novak SP, Galvin DM, Spicer RS, Cluff L, Kasat S. School and work status, drug‐free workplace protections, and prescription drug misuse among Americans ages 15–25. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(2):195‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller TR, Zaloshnja E, Spicer RS. Effectiveness and benefit‐cost of peer‐based workplace substance abuse prevention coupled with random testing. Accid Anal Prev. 2007;39(3):565‐573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Morantz AD, Mas A. Does post‐accident drug testing reduce injuries? Evidence from a large retail chain. Am L Econ Rev. 2008;10(2):246‐302. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ozminkowski RJ, Mark TL, Goetzel RZ, Blank D, Walsh JM, Cangianelli L. Relationships between urinalysis testing for substance use, medical expenditures, and the occurrence of injuries at a large manufacturing firm. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(1):151‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patterson CR, Bennett JB, Wiitala WL. Healthy and unhealthy stress unwinding: Promoting health in small businesses. J Bus Psychol. 2005;20(2):221‐247. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pidd K, Kostadinov V, Roche A. Do workplace policies work? An examination of the relationship between alcohol and other drug policies and workers' substance use. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;28:48‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schofield KE, Alexander BH, Gerberich SG, Ryan AD. Injury rates, severity, and drug testing programs in small construction companies. J Safety Res. 2013;44:97‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shepard E, Clifton T. Drug Testing: Does It Really Improve Labor Productivity? A new study casts doubt on company claims that testing of workers for illicit drug use results in enhanced productivity. Working USA. 1998;2(4):69. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spicer RS, Miller TR. Impact of a workplace peer‐focused substance abuse prevention and early intervention program. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(4):609‐611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sturm R. Managed care risk contracts and substance abuse treatment. Inquiry. 2000;37(2):219‐225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sweeney NL, Heaney C, Keller M. Enhancing employee well‐being: evaluation of an employee assistance program. 1995(9534076)158.

- 50. Waehrer GM, Miller TR, Hendrie D, Galvin DM. Employee assistance programs, drug testing, and workplace injury. J Safety Res. 2016;57:53‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wickizer TM, Kopjar B, Franklin G, Joesch J. Do drug‐free workplace programs prevent occupational injuries? Evidence from Washington State. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):91‐110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wilkinson ST, Yarnell S, Radhakrishnan R, Ball SA, D'Souza DC. Marijuana legalization: impact on physicians and public health. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:453‐466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, Hasin D. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1–3):22‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Phillips JA, Holland MG, Baldwin DD, et al. Marijuana in the workplace: guidance for occupational health professionals and employers: joint guidance statement of the american association of occupational health nurses and the american college of occupational and environmental medicine. Workplace Health Safety. 2015;63(4):139‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Konovsky MA, Cropanzano R. Perceived fairness of employee drug testing as a predictor of employee attitudes and job performance. J Appl Psychol. 1991;76(5):698‐707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material