Abstract

Interleukin (IL) 11 activates multiple intracellular signaling pathways by forming a complex with its cell surface α-receptor, IL-11Rα, and the β-subunit receptor, gp130. Dysregulated IL-11 signaling has been implicated in several diseases, including some cancers and fibrosis. Mutations in IL-11Rα that reduce signaling are also associated with hereditary cranial malformations. Here we present the first crystal structure of the extracellular domains of human IL-11Rα and a structure of human IL-11 that reveals previously unresolved detail. Disease-associated mutations in IL-11Rα are generally distal to putative ligand-binding sites. Molecular dynamics simulations showed that specific mutations destabilize IL-11Rα and may have indirect effects on the cytokine-binding region. We show that IL-11 and IL-11Rα form a 1:1 complex with nanomolar affinity and present a model of the complex. Our results suggest that the thermodynamic and structural mechanisms of complex formation between IL-11 and IL-11Rα differ substantially from those previously reported for similar cytokines. This work reveals key determinants of the engagement of IL-11 by IL-11Rα that may be exploited in the development of strategies to modulate formation of the IL-11–IL-11Rα complex.

Keywords: cytokine, receptor structure-function, interleukin, signaling, structural biology, inflammation, cancer, fibrosis, gp130, IL6 family cytokine

Introduction

Interleukin 11 (IL-11) is a member of the IL-6 family of cytokines, which includes IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor, oncostatin M, ciliary neutrophilic factor, IL-27, IL-31, cardiotrophin-1, cardiotrophin-like cytokine, and neuropoietin (1). Activation of downstream signaling pathways by these cytokines is generally initiated via the formation of oligomeric receptor complexes that include the β-subunit signaling receptor, gp130, and one or more cytokine-specific co-receptors (2, 3). The majority of our structural and mechanistic understanding of this cytokine family is based on structural information available for IL-6, leukemia inhibitory factor, and their receptors (4–6).

Characterization of the in vivo source of IL-11 has only recently begun, as a result of emerging links to multiple pathologies. IL-11 has classically been associated with hematopoiesis (7); however, it has more recently been identified as the major cytokine involved in gastrointestinal tumorigenesis and is a promising therapeutic target (8). IL-11 also has emerging roles in cardiovascular and liver fibrosis (9, 10). Mutations in the IL-11–specific α-receptor, IL-11Rα, have gained increased interest as a result of their causative role in hereditary diseases that are typified by craniosynostosis and delayed tooth eruption (11–14). Several of these mutations have been shown to impair IL-11 signaling in vitro (11).

Following secretion, IL-11 is believed to interact with IL-11Rα, which is expressed in tissue-specific cell populations (15). This binary complex is thought to subsequently engage gp130 (6, 16). Previous mutagenesis and structural studies indicate that IL-11 interacts with its receptors through three independent sites on its surface (17). Site I is responsible for IL-11Rα binding; site II binds a gp130 molecule and contributes to the formation of a trimeric complex; and site III engages with a second gp130 molecule, resulting in the cooperative formation of a hexameric signaling complex containing two copies of each component (16).

Upon formation of the signaling complex, Janus kinases (JAKs) associated with the cytoplasmic regions of gp130 are activated, although the exact mechanisms of activation remain unclear (18). Because IL-11Rα does not bind JAKs at its cytoplasmic domain, signaling is thought to result from transactivation of JAK molecules bound to the cytoplasmic domains of the two gp130 molecules of the hexameric signaling complex. JAK activation then leads primarily to phosphorylation and activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3. Activation of other signaling pathways, including the extracellular signal–regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway, is less well-understood.

The structural basis of IL-6 signaling has been well-studied, and the structure of the hexameric IL-6 signaling complex has been solved (6). Low-resolution EM studies of the IL-11 signaling complex suggest that the overall arrangement is likely similar to that of IL-6 (19). We previously reported the first crystal structure of human IL-11 (17) and showed that although the topology is similar to IL-6, IL-11 is significantly elongated, suggesting different geometry of the signaling complex. Despite the growing biological importance of IL-11 signaling, molecular understanding of the structure and assembly of the IL-11 signaling complex remains in its infancy.

Here, we present the first crystal structure of human IL-11Rα and a new, more complete structure of IL-11 that reveals structural details of functionally important regions. Disease-associated mutations in IL-11Rα are generally located distal to putative binding surfaces of the receptor. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal the mechanisms by which several of these mutations disrupt the structure of IL-11Rα and thereby prevent signaling. We present a model of the IL-11–IL-11Rα complex and in combination with biophysical and mutagenic characterization of the cytokine–receptor interaction show that IL-11Rα and IL-6Rα engage their cognate cytokines with similar affinities but use surprisingly different thermodynamic and structural mechanisms. Our work provides structural and mechanistic detail of the first step of formation of the IL-11 signaling complex that may be exploited in the development of molecules that can modulate complex formation.

Results and discussion

The structure of the extracellular domains of the interleukin 11 α-receptor

The complete extracellular region of IL-11Rα (IL-11RαEC; residues 1–341 of the mature protein after signal peptide cleavage) was expressed in the insect cell line Sf21 and purified from the cell culture supernatant. To reduce formation of disulfide-linked dimers, the C226S mutation (20) was present in all IL-11Rα constructs described in this work. Crystals of IL-11RαEC were in space group P6522. Initial phase estimates were obtained by molecular replacement using domains from unpublished Fab-bound structures of IL-11Rα, and the structure was refined at a resolution of 3.43 Å (PDB code 6O4P). Data and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1, and representative electron density is shown in Fig. S1 (A and B).

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and structure refinement statistics for IL-1Rα and IL-11Δ10

The values for the highest resolution shell are given in parentheses.

| IL-11Rα | IL-11Δ10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P6522 | P21212 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9537 | 0.9537 |

| Number of images | 60 | 3600 |

| Oscillation range per image (°) | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| Detector | ADSC Quantum 315r | Eiger 16M |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 171.46, 171.46, 107.94 | 39.02, 133.76, 27.18 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 45.67–3.43 (3.70–3.43) | 37.46–1.62 (1.68–1.62) |

| Rsyma | 0.575 (1.770) | 0.0774 (1.031) |

| Rmeasb | 0.611 (1.901) | 0.0808 (1.071) |

| Rpimc | 0.307 (0.952) | 0.0227 (0.286) |

| CC½d | 0.904 (0.436) | 0.999 (0.764) |

| I/σ(I) | 3.9 (1.1) | 17.79 (2.08) |

| Total observations | 92,918 | 244,140 |

| Unique reflections | 12,990 | 18,927 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (98.5) | 99.95 (99.89) |

| Multiplicity | 7.2 (7.3) | 12.9 (13.6) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 65.0 | 24.0 |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 45.67–3.43 (3.55–3.43) | 37.5–1.62 (1.72–1.62) |

| Reflections used in refinement | 12,962 (1243) | 18,925 (1845) |

| Rfree reflections | 612 (57) | 908 (84) |

| Rwork | 0.244 (0.318) | 0.1739 (0.2515) |

| Rfree | 0.298 (0.342) | 0.1926 (0.2742) |

| Protein molecules in asymmetric unit | 2 | 1 |

| Total non-hydrogen atoms | 4580 | 1470 |

| Protein | 4433 | 1319 |

| Ligand/ion | 147 | 6 |

| Solvent | 0 | 145 |

| Mean B-factor (Å2) | 65.9 | 36.02 |

| Protein | 64.9 | 35.33 |

| Ligand/ion | 97.4 | 47.58 |

| RMSD | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.58 | 1.36 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored (%) | 95.10 | 98.80 |

| Allowed (%) | 4.55 | 1.20 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.35 | 0.00 |

aRsym = ∑hkl∑i|Ii(hkl) − <I(hkl)>|/∑hkl∑iIi(hkl).

b Rmeas = ∑hkl[N/(N − 1)]½ ∑i|Ii(hkl) − <I(hkl)>|/∑hkl∑iIi(hkl).

c Rpim = ∑hkl[1/(N − 1)]½ ∑i|Ii(hkl) − <I(hkl)> |/∑hkl∑iIi(hkl).

d CC½ = Pearson correlation coefficient between independently merged half data sets.

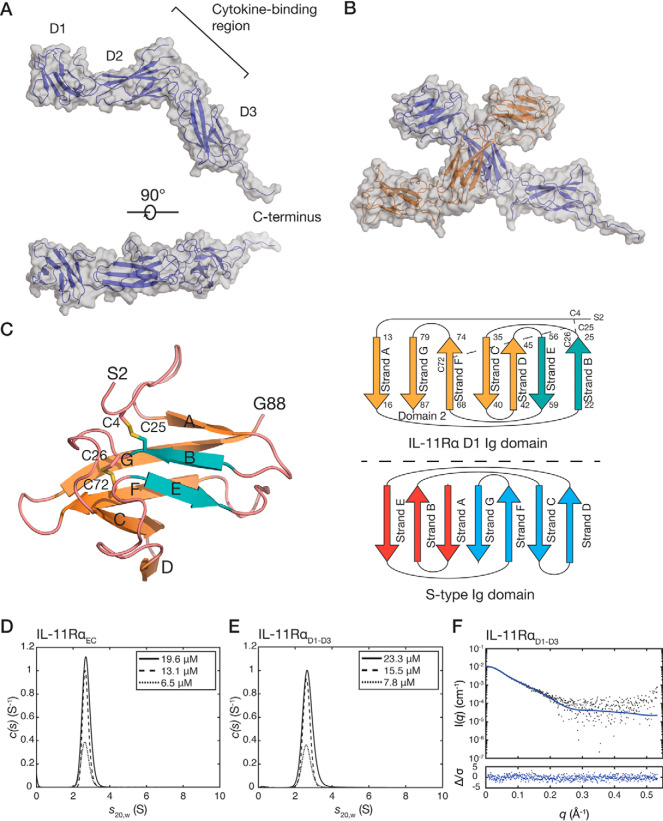

The structure of IL-11RαEC consists of an N-terminal Ig-like domain (D1) and two fibronectin type III (FnIII) domains (D2, D3) that form the cytokine-binding homology region (CHR) (Fig. 1A). By homology to other cytokine receptors, IL-11 likely binds to the loops present at the D2/D3 junction (Fig. 1A). The receptor is L-shaped, with D2 and D3 forming the CHR. The arrangement of the three domains is similar to other IL-6 family cytokine receptors (Fig. S1C). The α-carbon RMSD between IL-11Rα and IL-6Rα (PDB code 1N26) is 5.5 Å, and that between IL-11Rα and D1–D3 of gp130 (PDB code 1I1R) is 5.8 Å, indicating moderate structural similarity. The primary deviations between the three structures are in the position of D1. The putative cytokine-binding region in IL-11Rα shows less surface charge than that of IL-6Rα (Fig. S1D).

Figure 1.

The crystal structure of IL-11RαEC. A, two views of the structure of IL-11RαEC. Each of the domains and the section of the C-terminus that is defined in the electron density are indicated. The transmembrane domain is at the C-terminal region of the receptor. B, the asymmetric unit of the IL-11Rα crystal structure, formed by two IL-11Rα molecules, with an extensive contact between D2 of the two molecules. C, the structure (left panel) and topology (top right panel) of D1 from chain B of IL-11RαEC with disulfide bonds indicated. Loops are colored pink, the two strands contributing to the smaller, anti-parallel β-sheet are blue, and the five strands contributing to the larger, mixed parallel/anti-parallel β-sheet are orange. A topology diagram of the typical s-type Ig domain is also shown (bottom right panel). D, continuous sedimentation coefficient (c(s)) distributions for IL-11RαEC at three concentrations, showing that IL-11RαEC is primarily monomeric in solution under the conditions tested. Slight concentration dependence in the sedimentation coefficient suggests the formation of a transient oligomer. E, c(s) distributions for IL-11RαD1–D3 at several concentrations. F, small-angle X-ray scattering data for IL-11RαD1–D3, overlaid with the theoretical scattering profile calculated from molecule A of the crystal structure of IL-11RαEC (χ2 = 1.05).

Two protein molecules are present in the asymmetric unit (α-carbon RMSD of 2.0 Å), forming a crystallographic dimer in a “head-to-head” configuration through an interaction between D2 of each receptor molecule (Fig. 1B). The C terminus of the receptor is more complete in chain A, forming a crystal contact with a protein molecule in a neighboring asymmetric unit. The absence of density for the complete C terminus may be a result of disorder or caused by the presence of endoproteinase Glu-C during the crystallization experiment. N-Linked glycans are observed at Asn105 and Asn172.

D1 of IL-11Rα forms an Ig-like domain with an unusual s-type topology (22) (Fig. 1C). Strand A in the β sandwich forms a non-canonical mixed parallel/anti-parallel β sheet with strands G, F, C, and D. This is a similar overall topology to D1 of IL-6Rα; in both cases the Ig-fold is distorted (21). Two disulfide bonds are present in D1: one between Cys26 in the strand B/strand C linker and Cys72 in strand F. A disulfide bond in a similar position is present in the D1 of IL-6Rα (21). A second disulfide bond is present between Cys4 and Cys25 in strand B, which was not predicted from sequence analysis or homology to other receptors. The disulfide bond is well-supported in the electron density and confirmed in a simulated-annealing omit map (Fig. S1A). The unusual fold of D1 may be a consequence of these disulfides, with the Cys4–Cys25 disulfide serving to sterically constrain strand A, preventing the formation of a typical anti-parallel β-sheet with strands B and E.

D2 of IL-11Rα contains the two disulfide bonds expected for this domain (between Cys98 and Cys108 and between Cys148 and Cys158). D3 of IL-11Rα contains the conserved tryptophan–arginine ladder (comprising tryptophan residues 246, 282, and 285 and arginine residues 235, 239, 270, and 274), which includes the strongly conserved WSXWS sequence motif. Like other cytokine receptors, the sequence containing the WSXWS motif forms a short polyproline type II helix that is stabilized by side chain–main chain interactions and the tryptophan–arginine ladder.

The interface formed between the two IL-11Rα monomers in the asymmetric unit of the crystal structure has a buried surface area of 1088 Å2 (Fig. 1B) (23). To establish whether IL-11RαEC self-associates in solution, we used sedimentation velocity–analytical ultracentrifugation (SV-AUC) at protein concentrations of 6.5–19.5 μm (0.25–0.75 mg/ml) (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1E, panel i). These experiments show that IL-11RαEC is predominantly monomeric in solution with a standardized sedimentation coefficient (s20,w) of 2.70 at 13.0 μm. This represents a molecular mass of 41.3 kDa, with a frictional ratio (f/f0) of 1.57 calculated from the fit to the SV data (Fig. S1E, panel i), in good agreement with the expected molecular mass from the sequence (38.2 kDa). The theoretical sedimentation coefficient, calculated from the crystal structure coordinates of chain A using HYDROPRO (24) was 2.92, consistent with the experimental value. A small, concentration-dependent increase in weight-average sedimentation coefficient was observed, from 2.67 S at 6.5 μm to 2.72 S at 19.5 μm, likely indicating the formation of a weak-affinity dimer. It is possible that any weak-affinity dimerization is increased at the cell membrane, where the receptor may be concentrated in lipid rafts, analogous to other cytokine receptors (25, 26), and can diffuse in only two dimensions, increasing its effective concentration.

To study the solution properties of IL-11Rα without the C-terminal extension, we generated a construct comprising only domains D1–D3 (IL-11RαD1–D3; residues 1–297 of the mature protein). The standardized sedimentation coefficient of IL-11RαD1–D3 measured at a protein concentration of 15.5 μΜ (0.5 mg/ml) was 2.62 S (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1E, panel ii), corresponding to a molecular mass of 34.9 kDa, with a f/f0 value of 1.47, in good agreement with the sequence molecular mass (32.1 kDa). Similar to IL-11RαEC, a small concentration-dependent increase in weight average sedimentation coefficient was observed from 2.62 S at 7.8 μm to 2.69 S at 23.3 μm, suggesting that possible weak dimerization is mediated by the structured, extracellular domains of IL-11Rα and is not a consequence of the disordered C terminus. The small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) profile of IL-11RαD1–D3 agrees well with the monomer of the crystal structure coordinates (χ2 = 1.05) (Fig. 1F, Table S1, and Fig. S1F), confirming that the crystal structure accurately represents the solution conformation of the structured, extracellular domains of IL-11Rα.

Pathogenetic mutations disrupt the structure of IL-11Rα

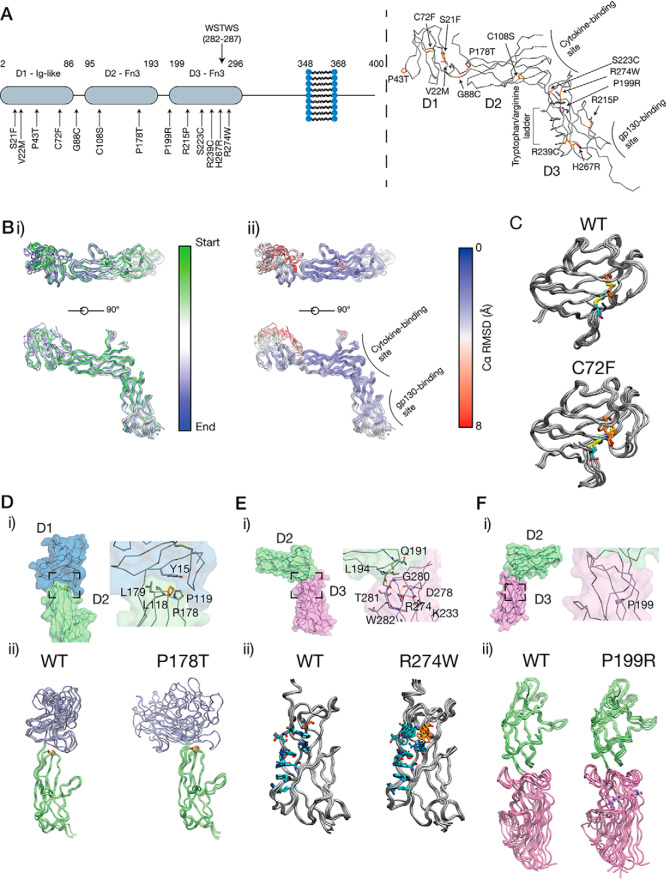

A number of pathogenic mutations have been identified in the gene for IL-11Rα, IL11RA, resulting in point-substitution mutations in IL-11Rα that cause a genetic disease featuring craniosynostosis and delayed tooth eruption (11–14). Mapping the disease-associated mutations onto our structure of IL-11Rα indicates that very few of the mutations are in the putative IL-11 or gp130 binding sites (Fig. 2A). The P178T, P199R, and R274W mutations have previously been studied in vitro (11); however, the lack of structural information on IL-11Rα has hindered understanding of the molecular impact of the mutations.

Figure 2.

Craniofacial disease-associated mutations in IL-11Rα. A, disease-associated mutations that have been identified in IL-11Rα. These mutations are shown mapped onto the structure and primarily occur in D1, interdomain turns, and D3. B, structural dynamics from a 50-ns MD simulation of IL-11Rα. Panel i, superposition of frames from the simulation. Five frames are shown, colored by simulation time. Coordinates were aligned to D2 in IL-11Rα. Panel ii, frames are shown colored by Cα RMSD. C, frames from a 50-ns MD simulation of the C72F mutant. Frames are shown overlaid through the simulation. The WT IL-11Rα simulation is shown for direct comparison. D, the structural impact of the P178T mutation, showing the location of Pro178 at the D1/D2 interface (panel i) and showing frames from the MD simulation (panel ii), showing that the P178T mutation destabilizes the native position of the D1. E, the structural impact of the R274W mutation, showing the position of Arg274, at the extreme end of the tryptophan–arginine ladder in D3 (panel i). Arg274 also forms a hydrogen-bond network, stabilizing the D2/D3 interface, frames from an MD simulation (panel ii), showing that the R274W mutation disrupts the tryptophan–arginine ladder and the D2/D3 interface. F, frames from a 50-ns MD simulation of the P199R mutant. Frames are shown overlaid through the simulation, with the WT IL-11Rα simulation shown for direct comparison.

To investigate the effects of the mutations on the structure of IL-11Rα, we ran a series of short (50 ns) all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on IL-11Rα (Fig. 2B) and several of the disease mutants. In IL-11Rα, the Cα RMSD and backbone amide bond order parameters (S2) calculated from the MD trajectory indicate a low level of local disorder and overall local rigidity within each of the three domains (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2A). However, the three domains were dynamic with respect to each other throughout the simulation (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2B). The loops comprising the putative IL-11 binding site were relatively rigid and do not undergo large motions on the time scale of the simulation.

MD simulations of IL-11Rα with the disease-associated mutations suggest that several of them destabilize key structural elements in the receptor or destabilize interdomain interfaces. One mutation, C72F, removes a disulfide bond in D1, which likely has a role in stabilizing the unusual Ig fold of D1. Introducing this mutation to D1 resulted in the loop joining strands F and G adopting a markedly different conformation, which may alter the stability of the domain (Fig. 2C, Fig. S2C, and Movie S1).

A second mutation, P178T, is located in a loop in D2 that faces D1. This mutation resulted in a shift in the relative pose of D1 and D2, likely because of removal of the interaction of Pro178 with a pocket on D1 that stabilizes the D1/D2 interface. However, in each replicate simulation, the final relative orientation of D1 and D2 differed. (Fig. 2D, Fig. S2, D and E, and Movie S2).

The R274W mutation is situated within the tryptophan–arginine ladder in D3 of the receptor. This mutation destabilized the tryptophan–arginine ladder and resulted in the destabilization of the membrane-distal region of D3. Arg274 also contributes to a hydrogen-bonding network at the D2/D3 interdomain interface in the WT receptor (Fig. 2E, Fig. S2F, and Movie S3). The mutation thus destabilizes the D2/D3 linker and results in an increase in flexibility at the D2/D3 interface, potentially disrupting the IL-11–binding interface and reducing cytokine affinity.

The P199R mutation is located in the D2–D3 interdomain linker. The mutation causes a slight increase in the D2–D3 interdomain distance but does not otherwise greatly alter the interdomain pose or dynamics of IL-11Rα (Fig. 2F, Fig. S2G, and Movie S4).

Several other pathogenic mutations have little appreciable impact on the structural dynamics within the time scale of the simulation. For example, P43T does not greatly alter the flexibility of the affected loop in D1, C108S does not appear to significantly alter D2 through the simulation, nor does R239C destabilize D3 or the tryptophan–arginine ladder in which it is situated (Fig. S2, H–J). One mutation (H276R) is close to the putative gp130-binding region of D3 and thus may act by directly altering signaling complex formation at this interface.

Together our simulations show that the effect of a subset of the craniosynostosis mutations in IL-11Rα is to destabilize the structure of IL-11Rα. The P178T, R274W, and P199R mutations have previously been shown to result in incomplete glycosylation, leading to retention in the endoplasmic reticulum and poor cell surface expression, contributing to reduced IL-11–mediated STAT3 activation (11). Our results suggest that destabilization of the structure caused by the P178T and R274W mutations is sufficient to stall correct trafficking of the receptor. D1 of IL-6Rα has previously been shown to be involved in intracellular trafficking of the receptor (27). Thus, destabilization of D1 or the D1/D2 interface in IL-11Rα by the P178T mutation may result in a lack of correct processing of the receptor. In the case of the R274W and P199R mutations, destabilization of the cytokine-binding surface at the junction between D2 and D3 may also reduce the IL-11–binding capacity of mutant IL-11Rα that is correctly expressed at the cell surface, further reducing the potential for formation of the active signaling complex. The apparently minor structural effects of some mutations, such as P199R, that are positioned distal to the putative cytokine- and gp130-binding regions of the receptor, suggest alternative mechanisms that impair IL-11 signaling, for example, disruption of protein expression or global receptor folding.

The high-resolution structure of IL-11

In our previous structure of human IL-11, parts of the long loops between helices A and B and between helices C and D were poorly defined (17). Mutagenesis suggests that the AB loop is involved in binding IL-11Rα (28), and in the structure of the IL-6 signaling complex, the AB loop forms contacts to both IL-11Rα and gp130 (6). To gain insight into these loops, we solved a higher-resolution structure of IL-11.

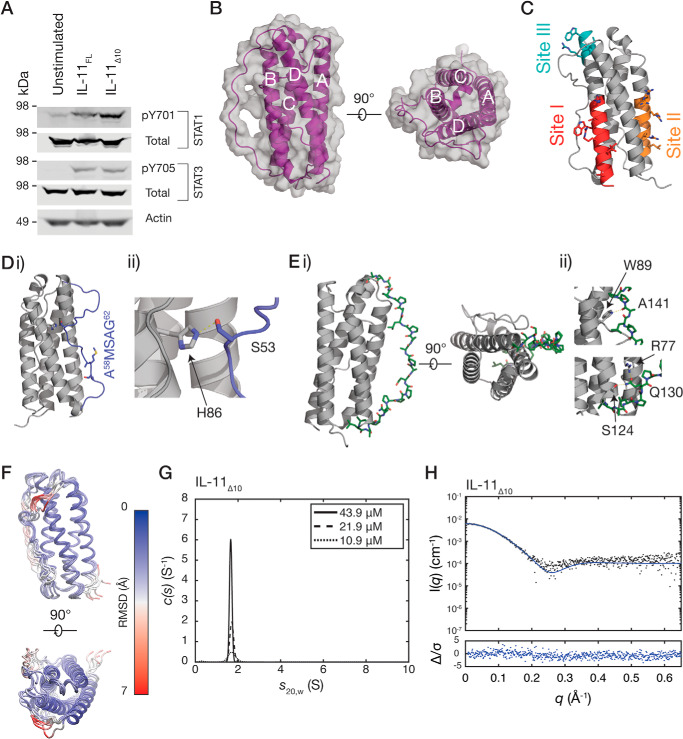

To facilitate growth of crystals that diffracted to high resolution, we truncated IL-11 by 10 residues at the N terminus. We named this new construct IL-11Δ10 (residues 11–178 of the mature protein) and the full-length protein IL-11FL. Both IL-11FL and IL-11Δ10 have similar high thermal stability, as measured by differential scanning fluorimetry (Fig. S3A) (29). Stimulation of human colon cancer cell line, DLD1 with either IL-11Δ10 or IL-11FL results in similar levels of activation of STAT1 and STAT3 (Fig. 3A), indicating that they have similar biological activity. We note that N-terminally truncated IL-11 constructs have been used previously with no reported alteration in biological activity (30, 31).

Figure 3.

Biological activity and crystal structure of IL-11Δ10. A, Western blotting, showing activation of STAT1 and STAT3 by IL-11FL and IL-11Δ10 in the colon cancer cell line, DLD1. B, two views of the structure of IL-11Δ10. The four helices in the structure are labeled. C, regions previously implicated in binding the IL-11 receptors. Site I is involved in binding IL-11Rα, and site II and III subsequently interact with the shared receptor gp130. D, panel i, the loop between the A and B helices (AB loop; blue). The residues mutated in the IL-11 antagonist are indicated. Panel ii, the interaction between the loop and core 4-helix bundle structure, with His105 and Ser75 forming a hydrogen bond. E, the CD loop (green), part of which forms a polyproline helix. Two views of the helix are shown in panel i. The interactions stabilizing the N- and C-terminal parts of the polyproline helix are shown in panel ii. F, 100-ns MD simulation of IL-11 Δ10. Frames are overlaid at 20-ns intervals, colored by α carbon (Cα) RMSD. The α-helical core is stable through the simulation, whereas the loops undergo dynamic motions. G, continuous sedimentation coefficient (c(s)) distributions for IL-11Δ10, at three concentrations, showing that it is monomeric in solution. H, small-angle X-ray scattering data for IL-11Δ10, overlaid with the theoretical scattering profile calculated from the crystal structure coordinates (χ2 = 1.43).

Crystals of IL-11Δ10 were rod-like plates in space group P21212. Initial phase estimates were obtained by molecular replacement using our previous structure of IL-11 (PDB code 4MHL), and the new structure was refined at a resolution of 1.62 Å (PDB code 6O4O; see summary statistics in Table 1 and representative electron density in Fig. S3B). Overall, the structure of IL-11Δ10 is similar to our previously solved structure of IL-11 (RMSD 1.5 Å, Fig. S3C), forming a typical cytokine four-α-helical bundle (Fig. 3B). The three receptor-binding sites of the cytokine are not significantly altered in the structure (Fig. 3C) (17). A cis proline (Pro103) is observed at the C-terminal end of the 310 helical section of helix C. The equivalent proline in our previous structure of IL-11 is in the trans configuration (Fig. S3D). Both proline isomers are strongly supported by electron density in their respective structures, suggesting that Pro103 can adopt either the cis or trans isomer and that the 310 helix is dynamic in solution.

Our high-resolution structure of IL-11Δ10 allows the extended loops joining helices A and B and helices C and D to be included in the model. The AB loop is formed by 26 residues between Phe43 and Leu69 (Fig. 3D). The position of the loop is stabilized by a hydrogen bond between Ser53 and His86 in helix B, and this region of the loop is thus well-defined in the election density. Mutagenesis has previously implicated the C-terminal end of the loop in receptor binding (28). This portion of the loop is adjacent to site I and poorly defined in the electron density.

The CD loop of IL-11 forms an unusually long polyproline type II (PP2) helix (Fig. 3E), comprising 14 residues. The CD loop is stabilized by several contacts between the loop and the core of the cytokine (Fig. 3E). To our knowledge, an equivalently long polyproline helix has not been observed in the structure of any other cytokine. The role of the PP2 helix is likely structural, to efficiently join the C-terminal end of helix C and the N-terminal end of helix D, which are 44 Å apart, with a relatively short sequence of 21 residues.

To further study the dynamic nature of the loops of IL-11, we ran a series of short (100 ns) molecular dynamics simulations on IL-11 (Fig. 3F). In the time scale of the simulation, the four-α-helical bundle was stable and did not undergo large movements (Fig. 3F and Fig. S3E). In agreement with NMR studies of other IL-6 family cytokines, the α-helices showed “helical fraying” and were more dynamic at the ends of the helices, compared with the core (Fig. 3F) (32, 33). The PP2 helix structure of the CD loop was preserved throughout the simulation, although the loop underwent lateral movements. The AB loop was generally highly dynamic on the time scale of the simulation, although the central portion of the loop was stabilized by interactions with the α-helical core. The C-terminal end of the loop, which is implicated in IL-11Rα binding, was highly dynamic on the time scale of the simulation.

We also used SV-AUC to show that IL-11Δ10 is monomeric, with no concentration-dependent increase in sedimentation coefficient. The sedimentation coefficient was measured as 1.7 S (Fig. 3G and Fig. S3F), representing a molecular mass of 17.2 kDa (f/f0 1.28), in agreement with the sequence molecular mass (18.2 kDa). The theoretical sedimentation coefficient calculated from the crystal structure was 1.8 S, in good agreement with the experimental value. SAXS data for IL-11Δ10 also agrees well with the theoretical scattering profile calculated for the crystal structure coordinates (χ2 = 1.43) (Fig. 3H, Table S1, and Fig. S3G). These experiments confirm that IL-11Δ10 is monomeric in solution. Similar experiments show that IL-11FL is monomeric in solution (Fig. S4, A–D).

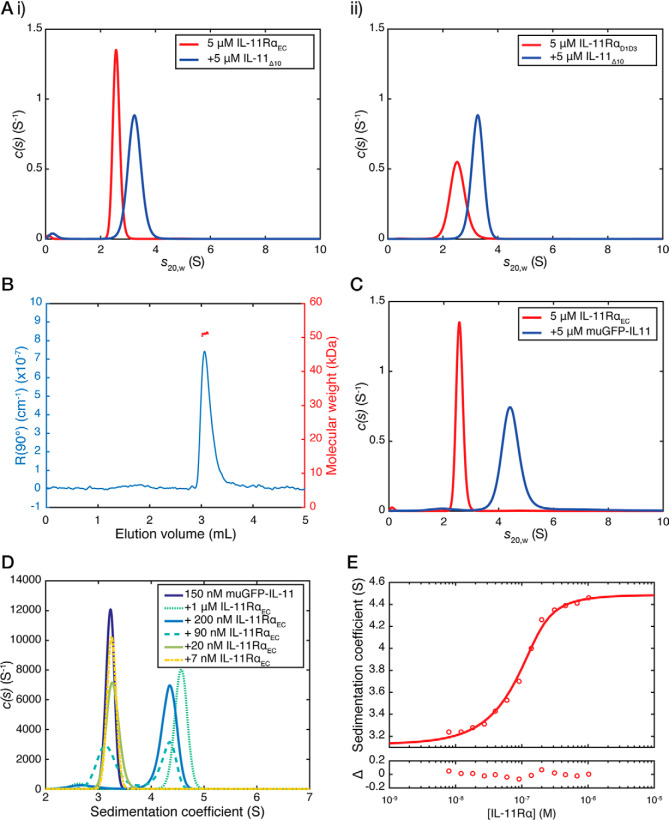

IL-11 and IL-11Rα interact with nanomolar affinity

We used SV-AUC to investigate the interaction between IL-11 and IL-11Rα. For these experiments, the complex was formed by mixing 5 μm IL-11Δ10 and 5 μm IL-11RαEC immediately prior to the experiment, with no further purification. The appearance of a peak in the c(s20,w) distribution with a sedimentation coefficient of 3.2 S, larger than either IL-11Δ10 and IL-11RαEC alone, indicated formation of a complex between IL-11RαEC and IL-11Δ10 (Fig. 4A, panel i). The estimated molecular mass of this species was 60.8 kDa, with f/f0 of 1.71, consistent with a complex forming with 1:1 stoichiometry (Fig. S5A). A similar complex was formed between IL-11Δ10 and IL-11RαD1–D3 (Fig. 4A, panel ii: sedimentation coefficient, 3.3; molecular mass, 55.8 kDa; f/f0, 1.61), between IL-11FL and IL-11RαEC (sedimentation coefficient, 3.2; molecular mass, 60.5 kDa; f/f0, 1.71), and between IL-11FL and IL-11RαD1–D3 (Figs. S6A and S7D; sedimentation coefficient, 3.3; molecular mass, 55.9 kDa; f/f0, 1.61).

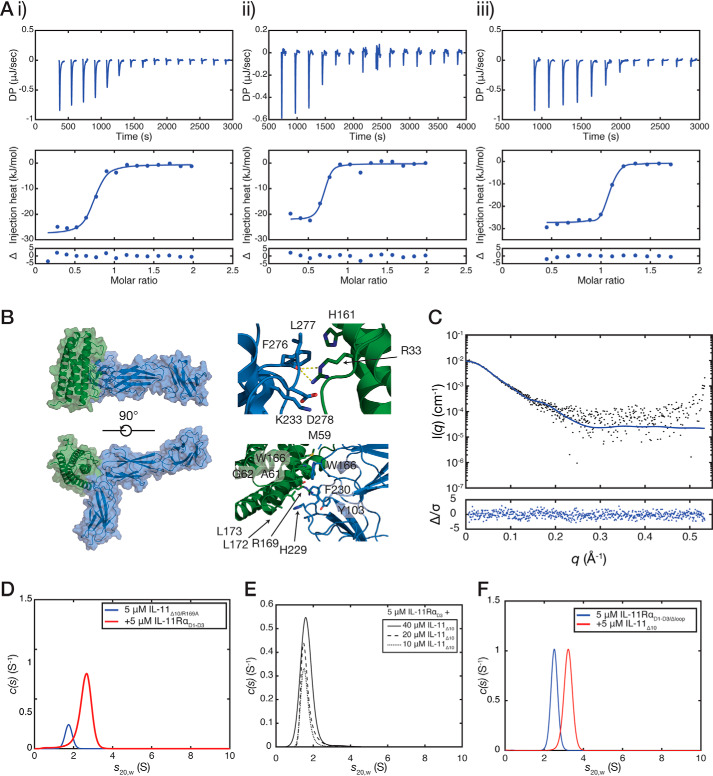

Figure 4.

SV-AUC analysis of the IL-11–IL-11Rα complex. A, continuous sedimentation coefficient (c(s)) distributions for the complex between IL-11RαEC and IL-11Δ10 (panel i) and IL-11RαD1–D3 and IL-11Δ10 (panel ii). The complex was formed by mixing 5 μm IL-11 and 5 μm IL-11Rα prior to the experiment, with no further purification. The c(s) distribution for 5 μm IL-11RαEC or IL-11RαD1–D3 is shown in all panels. B, SEC-MALS chromatograms (showing light scattering at 90° against elution volume) for the IL-11Δ10–IL-11RαD1–D3 complex (absolute molecular mass, 51.1 kDa). C, the c(s) distribution for muGFP–IL-11, and muGFP–IL-11 in complex with IL-11Rα. The complex was formed by mixing 5 μm muGFP–IL-11 and IL-11Rα prior to the experiment, with no further purification. The c(s) distribution for 5 μm IL-11RαEC is also shown. D, fluorescent-detected c(s) distributions for the muGFP–IL-11–IL-11Rα complex at concentrations close to the KD of the interaction. IL-11Rα concentrations are indicated in the figure, and muGFP–IL-11 was at a constant concentration of 150 nm. E, sedimentation coefficient isotherm for muGFP–IL-11 binding to IL-11Rα. The concentration of muGFP–IL-11 was 150 nm, titrated with increasing concentrations of IL-11Rα. The best fit to the data yielded a KD of 22 nm (68% CI 14–35 nm).

We used multi-angle light scattering coupled with size-exclusion chromatography (SEC-MALS) to provide additional evidence for the formation of a 1:1 complex between IL-11 and IL-11Rα. We measured the absolute molecular mass of IL-11Δ10 as 21.0 kDa, that of IL-11RαD1–D3 as 36.3 kDa (Fig. S6B), and that of the IL-11Δ10–IL-11RαD1–D3 complex as 51.1 kDa (Fig. 4B), consistent with a 1:1 complex.

To determine the dissociation constant for the IL-11–IL-11Rα interaction, we used fluorescence-detected SV-AUC (FD-AUC), which can accurately measure proteins present at nanomolar and picomolar concentrations (34). We expressed IL-11FL N-terminally fused to a monomeric, ultrastable GFP (muGFP) (35). SV-AUC showed that muGFP–IL-11 is monomeric across a wide concentration range (Figs. S6C and S8E) and forms a complex with IL-11RαEC in a 1:1 stoichiometry at concentrations of 5 μm of each component (Fig. 4C and Fig. S5B). Complex formation was apparent at concentrations of IL-11RαEC in the nanomolar range, with two peaks observed in c(s20,w) distributions corresponding to free muGFP–IL-11 and muGFP–IL-11 in complex with IL-11RαEC (Fig. 4D and Fig. S5C). We generated a sedimentation coefficient isotherm for the titration of IL-11RαEC against muGFP–IL-11, which, when fit to a 1:1 binding model, gave a KD of 22 nm (68% confidence interval, 14–35 nm) (Fig. 4E and Fig. S5C). This is consistent with the dissociation constant for similar site I cytokine–α receptor interactions. For example, IL-6 and IL-6Rα interact with a KD of 9 nm (6), IL-2 and IL-2Rβ interact with a KD of 144 nm (36), and IL-7 interacts with IL-7Rα with a KD of ∼50 nm (37). In each of these cases, the complete signaling complex is formed by further high-affinity interactions between the cytokine–α receptor complex and other receptors. These experiments show that the IL-11–IL-11RαEC interaction also fits into this paradigm; an initial low-nanomolar affinity step to form the complex between IL-11 and IL-11Rα occurs first, allowing subsequent engagement by gp130.

The tendency of GFP to form weakly associating dimers with a KD of ∼100 μm has previously limited the use of GFP in quantitative biophysical experiments (38). The monomeric, ultrastable GFP used here does not detectably dimerize (35), allowing it to be used as a genetically encoded fluorescent tag for biophysical experiments. Previous efforts to use FD-AUC to measure high-affinity protein–protein interactions have generally relied on covalent modification of one of the interacting partners with a fluorescent dye, with previous studies noting that the use of covalent dyes as fluorescent labels alters the binding properties of the proteins under investigation (39). The use of a genetically encoded, monomeric fluorescent fusion tag overcomes this limitation, allowing the accurate measurement of nanomolar-affinity dissociation constants in the analytical ultracentrifuge, without requiring the covalent modification of one of the proteins involved in the interaction.

The IL-11–IL-11Rα interaction is entropically driven

We used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to complement our FD-AUC binding experiments above and to examine the thermodynamic basis of cytokine–receptor engagement (Table 2). ITC showed that IL-11Δ10 interacts with IL-11RαEC and IL-11RαD1–D3 with similar affinities, with KD values of 40 ± 20 and 23 ± 3 nm, respectively (n = 3, standard error; Fig. 5A, panels i and ii). These values are consistent with our SV-AUC experiments and show that the C-terminal extension of IL-11Rα does not affect IL-11 binding. We also measured the affinity for the interaction between IL-11FL and IL-11RαEC, KD of 55 ± 14 nm (n = 3, standard error; Fig. S6D), showing that deletion of the N terminus of IL-11 does not significantly alter affinity for IL-11Rα (p = 0.58). The thermodynamics of the IL-11Δ10–IL-11RαD1–D3 interaction are strongly driven by entropy (ΔH = −25 ± 2 kJ/mol, ΔS = 66 ± 7 J/(mol·K)). We also measured the IL-11Δ10–IL-11RαD1–D3 interaction using ITC at two additional temperatures (283 and 298 K) to determine the heat capacity of the reaction, ΔCp (Fig. S6E, panels i–iii, and Table 2). The heat capacity was measured as −3.3 ± 0.07 kJ/(mol·K) (means ± S.E.). An empirical relationship exists between heat capacity and total buried surface area, a large negative ΔCp being consistent with a large buried surface area (40–42). This suggests that the IL-11–IL-11Rα interaction is hydrophobic in nature, resulting in the burying of a large hydrophobic surface.

Table 2.

Isothermal titration calorimetry data

The values shown are means ± S.E., n = 3 for all.

| KD | ΔH | ΔS | ΔG | Incompetent receptor fractiona | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nm | kJ/mol | J/mol·K | kJ/mol | K | ||

| IL-11Δ10 | ||||||

| IL-11RαEC | 40 ± 20 | −24 ± 0.6 | 65 ± 7 | −44 ± 2 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 303 |

| IL-11RαD1-D3 | 23 ± 3 | −25 ± 2 | 66 ± 7 | −45 ± 0.3 | 0.28 ± 0.06 | 303 |

| IL-11RαD1-D3 | 25 ± 2 | −10 ± 0.4 | 120 ± 10 | −46 ± 2.6 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 298 |

| IL-11RαD1-D3 | 130 ± 20 | 41 ± 1 | 280 ± 5 | −38 ± 0.4 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 283 |

| IL-11RαD1-D3/Δloop | 8 ± 4 | −26 ± 0.9 | 70 ± 6 | −47 ± 1 | 0.06 ± 0.05 | 303 |

| IL-11FL | ||||||

| IL-11RαEC | 55 ± 14 | −25 ± 1 | 59 ± 6 | −44 ± 0.7 | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 303 |

a Similar to N, see Ref. 60.

Figure 5.

Thermodynamics and molecular model of the interaction between IL-11 and IL-11Rα. A, isothermal titration calorimetry isotherms for the interaction between IL-11Δ10 and IL-11RαEC (KD = 40 ± 20 nm) (panel i), between IL-11Δ10 and IL-11RαD1–D3 (KD = 23 ± 3 nm) (panel ii), and between IL-11Δ10 and IL-11RαD1–D3/Δloop (KD = 8 ± 4 nm) (panel iii). A representative titration of three replicates is shown for each. All experiments were conducted at 30 °C (303 K) with ∼10 μm IL-11Rα in the cell and a 10-fold molar excess of IL-11Δ10 in the syringe. B, model of the IL-11RαEC–IL-11Δ10 complex. Panel i, two views of the complex. Panel ii, details of the interface with residues previously implicated in receptor binding highlighted. C, the experimental SAXS profile for the IL-11Rα–IL-11Δ10 complex overlaid with the theoretical scattering profile calculated from the model coordinates (χ2 = 1.03). An ab initio model is presented in Fig. S9D. D, continuous sedimentation coefficient (c(s)) distributions for the complex between IL-11RαD1–D3 and IL-11Δ10/R169A. The broad peak in the c(s) distribution suggests that the complex formed is lower affinity compared with IL-11Δ10. E, c(s) distributions showing that IL-11RαD3 does not interact with IL-11Δ10 at high affinity. No significant complex formation was observed with increasing concentrations of IL-11Δ10 in the presence of 5 μm IL-11RαD3. F, c(s) distributions for the complex between IL-11RαD1–D3/Δloop and IL-11Δ10. The complex was formed by mixing 5 μm IL-11RαD1–D3/Δloop with 5 μm IL-11Δ10 and centrifuged without further purification.

The cytokine-binding site of IL-11RαEC lacks large charged or hydrophilic regions, consistent with a hydrophobic interaction that is primarily driven by a positive change in entropy. This contrasts strongly with the IL-6–IL-6Rα interaction, which is strongly exothermic, with a corresponding unfavorable entropy change (ΔH −100 kJ/mol, ΔS −192 J/(mol·K) at 10 °C), a consequence of the structural differences between the two cytokines and receptors (6). Thus, despite apparent structural similarity, IL-6Rα and IL-11Rα employ different thermodynamic mechanisms to engage their cognate cytokines.

A model of the IL-11–IL-11Rα binary complex provides detail of the structural mechanism of engagement

Cytokines generally bind to the CHR surface at the junction between FnIII domains D2 and D3, with D3 also involved in interacting with other receptors comprising the complete signaling complex (1). This region of IL-11Rα is made up of four loops, formed by residues 98–106 (between strands A and B), residues 129–145 (between strands C and D) and 160–169 (between strands D and E) in D2, and residues 220–232 (between strands B and C) in D3. Part of the loop between strands C and D of D2 (residues 132–139 of chain A and 132–141 of chain B) was not defined in the electron density. To our knowledge, a similar large and disordered loop in the CHR has not yet been described for any other cytokine receptor. The membrane-proximal region of D3 serves to engage gp130, to complement the site II interaction on the cytokine. This region is similar in topology and surface charge in both IL-6Rα and IL-11Rα, suggesting that the mechanism of α-receptor engagement with gp130 is similar between the two receptors.

The configuration of the CHR differs between IL-11Rα and IL-6Rα (Fig. S1C, panel i). In IL-11Rα, the relative positioning of D2 and D3, which is more similar to that of gp130 (Fig. S1C, panel ii), creates a smaller cytokine-binding surface than IL-6Rα. The electrostatic surface potential in the cytokine-binding sites also differ between the two proteins (Fig. S1D). The IL-6–binding site in IL-6Rα is noticeably more charged than that of IL-11Rα, with a negatively charged patch formed by several acidic residues in the loop formed between strands F and G in D3, which mediate a number of electrostatic contacts to IL-6 in the IL-6 signaling complex (Fig. S1D) (6, 21). These structural differences suggest that IL-11Rα employs different structural mechanisms from IL-6Rα to engage its cognate cytokine at Site-I.

To investigate the structural mechanism of IL-11 binding by IL-11Rα, we constructed a model of the IL-11–IL-11Rα complex. Using the structure of the IL-6 signaling complex (PDB code 1P9M (6)), we aligned IL-11 and IL-11Rα to their homologous chains in the IL-6 complex and refined this model using RosettaDock of the Rosie server (43, 44). Models were scored using RosettaDock, and the top-scoring model was taken as the representative model (Fig. 5B). An overlay of the initial model and the final model is shown in Fig. S9A, the top 10 scoring models are shown in Fig. S9B. Relative to the initial model, the docked model shows a significant rotation of the pose of cytokine with respect to the binding site on the receptor. The model shows that the missing CD loop in D2 of IL-11Rα, which we did not include in the model, is in close proximity to the binding site.

Our model has a buried surface area of 567 Å2 at the interface between IL-11 and IL-11Rα, similar to that of the IL-6–IL-6Rα interface in the IL-6 signaling complex (706 Å2). This is consistent with the initial cytokine–receptor interaction forming a transiently stable complex. The pose of D2 with respect to D3 of IL-11Rα is different from that of IL-6Rα, resulting in a differently shaped cytokine-binding surface (Fig. S9C), which may account for the small difference in buried surface area. The binding mode of the cytokine is overall similar, consistent with previous mutagenesis on IL-11 and our structure of IL-11 (17, 45–47).

SAXS analysis of the IL-11–IL-11Rα complex supports the docked model. The complex was formed by mixing IL-11RαD1–D3 and IL-11Δ10 at an equimolar ratio, prior to SAXS measurement. The molecular mass was measured as 50.1 kDa, consistent with a 1:1 complex, and in agreement with the mass and stoichiometry determined by SV-AUC and SEC-MALS (Table S1). Theoretical scattering for the docked model fits the experimental SAXS data well (χ2 = 1.03) (Fig. 5C, Table S1, and Fig. S7A), showing that the model accurately represents the overall shape of the binary IL-11Rα–IL-11 complex. Similarly, the model agrees well with an ab initio model of the complex, generated using DAMMIN (Fig. S9, D and E). Likewise, the theoretical sedimentation coefficient (3.3 S) matches the experimentally determined sedimentation coefficient of the IL-11RαD1–D3–IL-11Δ10 complex (3.3 S) (Fig. 4A, panel ii), further supporting the 1:1 stoichiometry of the complex.

We used the PISA server to analyze the interactions formed between the two proteins in the docked model. The major interacting residues of IL-11 are Arg33, Met59, Ala61, Gly62, and several residues in the C terminus of the cytokine, particularly Arg169 (Fig. 5B). Arg33, in the N-terminal helix of the cytokine, and His161 helix D both form hydrophobic interactions with Phe276, Leu277, and Asp278 in the FG loop in D3 of the receptor. Similar contacts are formed in the five top scoring models. An extensive contact is formed between the C-terminal region of the cytokine and the receptor in the model. IL-11 residues Asp165, Trp166, Arg169, Leu172 and Leu173 form an extensive hydrophobic interaction with His229 and Phe230 in the BC loop of D3 of the receptor, with a small contribution from Tyr103 in the AB loop of D2. A contact is also formed by Met59, Ala61, and Gly62 in the AB loop of IL-11 with Tyr166 in the EF loop of D2 of the receptor.

Because Arg169 of IL-11 makes a key intermolecular contact in our model, we constructed and purified the IL-11Δ10/R169A mutant. SV-AUC analysis of 5 μm IL-11RαD1–D3 in the presence of 5 μm IL-11Δ10/R169A results in a peak in the sedimentation coefficient distribution of ∼2.7 S (Fig. 5D and Fig. S8A), less than that for the IL-11Δ10–IL-11RαD1–D3 complex (3.3 S), showing that the R169A mutation substantially decreases affinity for IL-11Rα. Stimulation of DLD1 cells with IL-11Δ10/R169A showed greatly reduced potency in activation of STAT3 than the WT cytokine (Fig. S7B), consistent with the reduction in IL-11Rα binding leading to impaired formation of the active signaling complex. Residues important for biological activity of IL-11 have previously been identified by site-directed mutagenesis of human and mouse IL-11 (45–47), and these mutagenesis experiments further support our model (Fig. S9F). Substitution of Arg33, Asp165, Trp166, Arg169, Leu172, and Leu173 all reduce the biological activity of IL-11 (45–47). The N-terminal region of the AB loop of IL-11, containing the interacting residues Met59, Ala61, and Gly62 has previously been targeted by phage display and mutagenesis to alter the binding of IL-11 to IL-11Rα; thus, this region has also been shown to be key for the interaction.

Our model predicts that IL-11 forms interfaces of 225 and 369 Å2 with D2 and D3, respectively. Previously, the isolated D3 of IL-11Rα was reported to bind IL-11 with an affinity of 48 nm (20). We expressed, purified, and refolded D3 of IL-11Rα (IL-11RαD3; residues 192–315 of the mature protein) from Escherichia coli inclusion bodies. SV-AUC analysis of IL-11RαD3 showed a single, narrow peak in the c(s20,w) distribution with a sedimentation coefficient of 1.5 S (calculated from the fit to the data at 28 μm) and no concentration-dependent change (Figs. S7C and S8F), indicating a homogenous product that did not self-associate in the concentration range measured. CD spectra of the refolded protein showed a characteristic all-β spectrum, with a positive peak at 230 nm, likely because of π-stacking interactions in the WSXWS motif (48) (Fig. S7D). 15N-1H heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectra from the purified, refolded IL-11RαD3 were well-dispersed and showed seven resolved tryptophan indole NH resonances of different intensities and line widths, indicating that the protein is folded (Fig. S7E).

SV-AUC analysis of IL-11RαD3 (5 μm) with increasing concentrations of IL-11Δ10 showed no concentration-dependent increase in sedimentation coefficient, with weight average s20,w values of 1.67 S at 10 μm IL-11Δ10, 1.66 S at 20 μm, and 1.62 S at 40 μm (Fig. 5E and Fig. S8B). Because the theoretical sedimentation coefficient of the IL-11–IL-11RαD3 complex is 2.62 S, these data suggest that IL-11RαD3 does not bind IL-11 with high affinity.

An apparently unique feature of the IL-11–binding site in IL-11Rα is a dynamic loop between strands C and D in D2 of the receptor. Our model of the binary complex suggests that this loop may contact bound cytokine and therefore could have a role in binding IL-11, through the formation of polar contacts between the loop and cytokine or by providing additional buried surface area. To investigate this, we generated a construct, IL-11RαD1–D3/Δloop, in which residues 132–140 in the loop were removed and replaced by two glycine residues. SV-AUC showed that IL-11RαD1–D3/Δloop is monomeric in solution and formed a complex with IL-11Δ10 with the expected 1:1 stoichiometry (Fig. 5F and Fig. S8C). ITC showed that the KD of the interaction between IL-11Δ10 and IL-11RαD1–D3/Δloop is 8 ± 4 nm (n = 3; Fig. 5A, panel iii), not significantly different from that of IL-11Δ10 and IL-11RαD1–D3 (p = 0.21). Thus, removal of the loop does not significantly alter the affinity for the interaction between IL-11Rα and IL-11Δ10, suggesting that the loop does not participate directly in cytokine binding.

It is possible that the dynamic loop functions to partially shield the hydrophobic regions of the cytokine-binding surface in the absence of cytokine, thereby reducing the potential of this region to participate in deleterious, nonspecific interactions. This function would be consistent with our observation that other cytokine receptors that have more hydrophilic character at their cytokine-binding regions, such as IL-6Rα, do not possess this dynamic loop structure.

Conclusion

The increasing identification of roles for IL-11 in a broad range of diseases underscores the need to thoroughly understand the structure of IL-11, its receptors, and the overall molecular mechanism of IL-11 signaling complex formation. Here, we have solved the crystal structure of human IL-11Rα and a new structure of human IL-11 that reveals detail of functionally important loop regions. We show that several mutations in IL-11Rα that are associated with disease act to disrupt key structural elements in IL-11Rα, for example through disrupting interdomain interfaces or conserved structural motifs within the receptor. We present a model of the complex and support this model through biophysical and mutagenic analysis. We propose that a dynamic loop proximal to the cytokine-binding region of IL-11Rα functions to protect this region from nonspecific interactions. Our data elucidate the structural and thermodynamic mechanisms of IL-11 binding by IL-11Rα and show that this engagement is mediated by both D2 and D3 of the receptor. Together, this work reveals key structural determinants of cytokine engagement by IL-11Rα on the pathway to formation of the active signaling complex. This molecular detail can be exploited in future development of agents that can modulate this process.

Experimental procedures

Protein expression and purification

Human IL-11RαEC with N-terminal honeybee-melittin signal peptide and C-terminal His8 tag, was expressed in Sf21 insect cells. Recombinant protein was purified using nickel-affinity chromatography and gel-filtration chromatography. IL-11RαD1–D3 and IL-11RαD1–D3/Δloop with N-terminal honeybee-melittin signal peptide, His8 tag, and TEV cleavage site were expressed in Sf21 cells. Recombinant protein was purified from conditioned media using nickel-affinity chromatography and gel-filtration chromatography. Cleavable tags were removed using TEV protease. IL-11RαD3 was refolded and purified from bacterial inclusion bodies as previously described (20). All IL-11Rα constructs contained the C226S mutation to reduce formation of disulfide cross-linked dimers (20).

IL-11FL, IL-11Δ10, and IL-11Δ10/R169A with the N-terminal His6 tag, maltose-binding protein, and a TEV protease cleavage site (MBP-IL-11FL or MBP-IL-11Δ10) were expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells. All constructs were purified by nickel-affinity chromatography, followed by cation exchange chromatography and gel-filtration chromatography. Tag removal was achieved using TEV protease. muGFP–IL-11 was expressed and purified as above with no TEV cleavage.

Crystallization and X-ray diffraction data collection

IL-11RαEC was crystallized using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method. Initial crystals were obtained at 293 K in the precipitant 28% PEG 400, 0.2 m calcium chloride, and 0.1 m sodium HEPES, pH 7.5. Crystallization drops were produced by mixing 1.1 mg/ml IL-11RαEC in a ratio of 1:0.9:0.1 with the precipitant and the endoproteinase Glu-C. Spherulites appeared after 24 h and were used to prepare a microseed stock (49). Subsequent seeding gave needle clusters in the condition 20% PEG 3350, 0.2 m lithium citrate. Seeding using these needle crystals produced single crystals in the condition 0.1 m HEPES, pH 8, 20 mm sodium chloride, 1.6 m ammonium sulfate, 67 mm NDSB-195. Crystallization drops were produced by mixing 1.5 μl of IL-11RαEC (1 mg/ml), 0.65 μl of precipitant, 0.4 μl of NDSB-195, 0.15 μl of Glu-C, and 0.3 μl of seed. Spindle-like crystals appeared after 48 h and grew to the approximate dimensions 20 μm × 7 μm × 7 μm.

IL-11Δ10 was crystallized using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method. Crystals were obtained at 293 K in the precipitant 30% PEG 3350, 0.2 m ammonium sulfate, 0.1 m Tris, pH 8.5. Crystals appeared after 24 h as thick bundles of two-dimensional plates. These crystals were used for microseeding, providing single crystals in the precipitant 18% PEG 3350, 0.1 m Bis-Tris propane, pH 9, 0.2 m ammonium sulfate, 5 mm praseodymium chloride. Crystallization drops were produced by mixing 1.5 μl of IL-11Δ10 (5 mg/ml), 1.5 μl of precipitant, and 0.5 μl of seed. Plates appeared overnight and grew to the approximate dimensions 500 × 20 × 5 μm after equilibration against precipitant for 1 week. Crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen directly from crystallization drops, and X-ray diffraction data were collected at 100 K at the Australian Synchrotron MX2 Beamline (50).

X-ray diffraction data processing and structure refinement

Diffraction data were indexed, integrated and scaled using XDS (51), analyzed using POINTLESS (52) and merged using AIMLESS (53) from the CCP4 suite. Initial phase estimates for IL-11Rα were obtained by molecular replacement with Phaser (54), using individual domains of IL-11Rα from unpublished Fab-bound structures as the search models. Refinement was performed using phenix.refine with noncrystallographic symmetry torsion restraints (55), followed iteratively by manual building using Coot (56). Several cycles of simulated annealing were performed early in the refinement to reduce potential model bias. Translation/libration/screw (TLS) refinement was performed in the final rounds, with each domain defined as a separate TLS group. Simulated annealing composite omit maps were calculated using Phenix.

Initial phase estimates for IL-11Δ10 were obtained using molecular replacement with Phaser (54), using our previous structure of IL-11 (PDB code 4MHL) (17) as the search model. Auto-building with simulated annealing was performed in phenix.autobuild to reduce phase bias from the search model. Refinement was performed in phenix.refine (55) with iterative manual building using Coot (56). TLS refinement was performed using a single TLS group containing all protein atoms. Explicit riding hydrogens were used throughout refinement and included in the final model; the atomic position and B factors for hydrogens were not refined. Structures were visualized in PyMOL and aligned with the CE (57) algorithm in PyMOL. Buried surface area was determined using the PISA server (23)

Residues of both structures are numbered according to the mature protein sequence after cleavage of signal peptides.

Absorbance-detected sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation

Absorbance-detected SV-AUC experiments were conducted using a Beckman Coulter XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge, equipped with UV-visible scanning optics. Reference and sample solutions were loaded into double-sector 12-mm cells with quartz windows and centrifuged using an An-60 Ti or An-50 Ti rotor at 50,000 rpm (201,600 × g) and 20 °C. Radial absorbance data were collected at 280 nm, in continuous mode. All experiments were conducted in TBS (20 mm Tris, 150 mm sodium chloride), pH 8 or 8.5. IL-11Δ10 and muGFP–IL-11 was centrifuged at concentrations of 0.8, 0.4, and 0.2 mg/ml. IL-11Rα was centrifuged at concentrations of 0.75, 0.5, and 0.25 mg/ml. Complexes of IL-11 and IL-11Rα were prepared by mixing 5 μm each of IL-11 and IL-11Rα and centrifuged without further purification. Sedimentation data were fitted to a continuous sedimentation coefficient, c(s), model, and the frictional ratio (f/f0) was fit using SEDFIT (58). Buffer density, viscosity, and the partial specific volume of the protein samples were calculated using SEDNTERP (59). For the complexes between IL-11 and IL-11Rα and between muGFP–IL-11 and IL-11Rα, the partial specific volume used was 0.73 ml/g. The theoretical sedimentation coefficients of IL-11Δ10 and IL-11Rα were calculated using HYDROPRO, using standard conditions (water, 20 °C) (24).

Fluorescence-detected sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation

Fluorescence-detected SV experiments were conducted using a Beckman XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge, equipped with an Aviv Biomedical fluorescence detection system. Sample solutions were loaded into double-sector 12-mm cells with quartz windows and centrifuged using an An-50 Ti rotor. Experiments were conducted at 50,000 rpm (201,600 × g) and 20 °C. muGFP–IL-11 was centrifuged at a concentration of 150 nm (0.007 mg/ml).

To generate the sedimentation coefficient isotherm, the concentration of muGFP–IL-11 was 150 nm, and a 1.5-fold serial dilution series of IL-11Rα was prepared starting from a concentration of 1 μm in TBS, pH 8.0. To prevent nonspecific absorption of muGFP–IL-11 to cell components, 0.2 mg/ml κ-casein (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the samples (34). Sedimentation velocity data were processed in SEDFIT as above. c(s) distributions were integrated between 1.0 and 6.0 S. The isotherm was fitted to a 1:1 heteroassociation model in SEDPHAT, with KA and the sedimentation coefficients of muGFP–IL-11 and the complex floated in the analysis (60). The 68% confidence interval was estimated using SEDPHAT.

Small-angle X-ray scattering

SAXS experiments were conducted at the Australian Synchrotron SAXS/WAXS Beamline, using co-flow to limit radiation damage and allow higher X-ray flux onto the sample and an optimized chromatography system to limit sample dilution (61–63). The X-ray beam energy was 11,500 eV (λ = 1.078 Å). For IL-11Δ10 and IL-11FL, the sample-to-detector distance used was 2038 mm, providing a total q range of 0.007–0.664 Å−1, q = (4πsinθ)/λ. For IL-11RαD1–D3 and the IL-11RαD1–D3–IL-11Δ10 complex, the sample-to-detector distance used was 2539 mm, providing a total q range of 0.006–0.534 Å−1. The data were collected following fractionation with an in-line size-exclusion chromatography column (Superdex 200 5/150 Increase, GE Healthcare,) pre-equilibrated in TBS, pH 8.5, 0.2% sodium azide. The IL-11RαD1–D3–IL-11Δ10 complex was prepared by mixing IL-11RαD1–D3 and IL-11Δ10 in a 1:1.5 molar ratio. The data were collected from a 1.5-mm capillary under continuous flow, with frames collected every second. Data reduction was performed using the Scatterbrain software, SEC-SAXS analysis using CHROMIXS (64), and the ATSAS suite (64, 65). Theoretical scattering profiles from the crystal structure coordinates were calculated and fit to the experimental scattering data using CRYSOL (66). Ab initio models were calculated using DAMMIF (67) and DAMMIN (68, 69). Ten models were calculated using DAMMIF, the models were averaged using DAMAVER, and the averaged model was used as a starting model for DAMMIN. A summary of the SAXS data acquisition and processing is given in Table S1.

Molecular dynamics simulations

All MD simulations were performed using NAMD 2.1.3b1 (70) and the CHARMM22 force field (70, 71) at 310 K in a water box with periodic boundary conditions. Simulations were analyzed in VMD 1.9.3 (72). A model of IL-11Rα was created based on chain B of the crystal structure. The missing loop (residues 132–141) was rebuilt using the PHYRE2 server (73). The missing loop was excluded from all representations of the trajectories and the analysis. The disordered C terminus was not simulated in the model. The structures were solvated (box size, 88.8 × 126.6 × 53.9 Å), and ions were added to an approximate final concentration of 0.15 m NaCl. Simulations of IL-11Rα was carried out with 10-ps minimization, followed by 50-ns MD. Mutations were introduced to this equilibrated model, and a further simulation was carried out with 10-ps minimization and then 50-ns MD. An additional 50-ns MD was also performed for the unmutated IL-11Rα. The interdomain distance distributions were calculated using a script in VMD, which defined a centroid for each of the three domains and measured the change in distance through the MD simulation. A model of the complete IL-11Δ10 structure was created based on the crystal structure. For residues with multiple orientations, only one orientation was selected. The structure was solvated (box size, 53.6 × 53.1 × 74.9 Å), and ions were added to an approximate final concentration of 0.15 m NaCl. A MD simulation was performed using a 10-ps minimization time, followed by 100-ns MD.

Differential scanning fluorimetry

Protein samples were analyzed by differential scanning fluorimetry at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml in TBS, pH 8.5, with 2.5× SYPRO Orange dye (Sigma–Aldrich). 20 μl of the sample was loaded into a 96-well quantitative PCR plate (Applied Biosystems), and four technical replicates of each sample were analyzed. The plates were sealed, and the samples were heated in an Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus quantitative PCR instrument, from 4 to 95 °C, with a 1% gradient. The unfolding data were analyzed using a custom script in MATLAB r2016a. The temperature of hydrophobic exposure (Th) was defined as the minimum point of the first derivative curve and used to compare the thermal stability of different proteins (29).

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Protein samples were buffer exchanged into TBS, pH 8.5, using gel filtration before analysis by ITC. ITC data were collected at 303 K using a MicroCal iTC200 (GE Healthcare). Titrations were performed using 15 injections of 2.5 μl of IL-11, after an initial injection of 0.8 μl. IL-11Rα was present at a concentration of 10 μm, and the concentration of IL-11 was 10-fold greater than the concentration of IL-11Rα. Titration data were integrated using NITPIC (74, 75) and analyzed in SEDPHAT using a 1:1 interaction model (60). Each titration was conducted in triplicate. The values stated are the means ± S.E.

In vitro cell culture

DLD1 cells were grown in RPMI + 10% fetal calf serum, in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were grown to confluency in 6-well plates, the medium was removed, and the cells were treated with IL-11Δ10 or IL-11FL at a concentration of 50 ng/ml in RPMI or RPMI as a vehicle control and incubated for 1 h. The cells were then washed with cold PBS and lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay. Lysates were diluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer, resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, and wet-transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked, incubated with the indicated primary antibodies (for phospho-STAT3 CST catalog no. 9145; for phospho-STAT1 CST catalog no. 9167, for total STAT3 CST catalog no. 4904 for total STAT1 CST catalog no. 9172, and for actin Sigma catalog no. A1978), then detected using conjugated fluorescent secondary antibodies (Odyssey catalog no. 926-32211/926-68072), and visualized using the Odyssey IR imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). Original membranes are shown in Fig. S10.

Docking

In silico docking was performed using the Docking2.0 algorithm, part of the ROSIE server (43, 44, 76). An initial approximation of the complex orientation was generated by overlaying the IL-11Rα and IL-11 structures with IL-6Rα and IL-6 in the IL-6 signaling complex structure (6). This model was used as input to the docking_local_refine protocol of RosettaDock, which limits rotations/transitions of the complex components. The models were scored by RosettaDock. The top-scoring model was taken as the representative model. Buried surface area and interacting residues were determined using the PISA server (23).

CD spectroscopy

CD experiments were conducted using an Aviv CD spectrometer (410-SF). Spectra were collected for 12 μm IL-11RαD3 at 20 °C, in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, over a wavelength range of 260–190 nm in 1-nm steps with an averaging time of 4 s, using a 1-mm-path length quartz cuvette. Each measurement (sample and blank) was collected in triplicate. The buffer signal was subtracted, and the data were converted to mean residue ellipticity.

Multi-angle light scattering

SEC-MALS data were collected using a Shimadzu LC-20AD HPLC, coupled to a Shimadzu SPD-20A UV detector, Wyatt Dawn MALS detector and Wyatt Optilab refractive index detector. The data were collected following in-line fractionation with a Zenix-C SEC-300 4.6 × 300-mm SEC column (Sepax Technologies), pre-equilibrated in 20 mm Tris, 150 mm sodium chloride, pH 8.5, running at a flow rate of 0.35 ml/min. 10 μl of sample was applied to the column at a concentration of ∼2 mg/ml. The IL-11RαD1–D3–IL-11Δ10 complex was prepared by mixing equimolar concentrations of the components prior to the experiment. MALS data were analyzed using ASTRA, version 7.3.2.19 (Wyatt). The detector response was normalized using monomeric BSA (Pierce, catalog no. 23209). Protein concentration was determined using differential refractive index, using a dn/dc of 0.184.

NMR spectroscopy

15N-IL-11RαD3 was expressed using the method of Marley et al. (77), purified, and refolded as previously described (20), and successful incorporation of 15N was confirmed using electrospray ionization–TOF MS. 15N-1H heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectra were collected on an 18.8 T Bruker Avance II spectrometer (1H resonance frequency 800 MHz), at 283 K, on 130 μm 15N-IL-11RαD3, 20 mm Bis-Tris, 50 mm arginine, 10% 2H2O, pH 7. The spectra were processed using NMRPipe (78) and visualized using NMRFAM-SPARKY (79).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed, paired t test in Microsoft Excel, version 16.27 for Mac OSX.

Data availability

Coordinates and structure factors for IL-11RαEC and IL-11Δ10 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 6O4P and 6O4O, respectively. SAXS data and models for IL-11Δ10, IL-11FL, IL-11RαD1–D3, and the IL-11Δ10–IL-11RαD1–D3 complex have been deposited in the Small Angle Scattering Biological Data Bank with accession codes SASDGH2, SASDGJ2, SASDGG2, and SASDGK2, respectively. All other data are contained within the manuscript and the supporting information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Parts of this research were conducted at the SAXS/WAXS and MX2 Beamlines of the Australian Synchrotron, part of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation and made use of the Australian Cancer Research Foundation Detector at the MX2 Beamline. Initial crystallization screens were conducted at the CSIRO Collaborative Crystallisation Centre (Melbourne, Australia).

This article contains supporting information.

Author contributions—R. D. M., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. conceptualization; R. D. M., K. A., C. O. Z., C. J. M., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. formal analysis; R. D. M., K. A., C. J. M., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. validation; R. D. M., K. A., C. O. Z., P. M. N., C. J. M., D. S. S. L., R. C. J. D., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. investigation; R. D. M. visualization; R. D. M., K. A., C. J. M., D. S. S. L., H.-C. C., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. methodology; R. D. M., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. writing-original draft; R. D. M., K. A., C. O. Z., P. M. N., C. J. M., R. C. J. D., M. W. P., P. R. G., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. writing-review and editing; M. W. P., P. R. G., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. resources; M. W. P., P. R. G., T. L. P., and M. D. W. G. supervision; T. L. P. and M. D. W. G. funding acquisition; T. L. P. and M. D. W. G. project administration.

Funding and additional information—This work was supported by National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia Grants APP1147621 and APP1080498), Australian Research Council Future Fellowship Project FT140100544 (to M. D. W. G), Victorian Cancer Agency Fellowship MCRF16009 (to T. L. P.), National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia Research Fellowship APP1117183 (to M. W. P.), and Contract UOC1506 from the Victorian Government Operational Infrastructure Support Scheme to St. Vincent's Institute and the New Zealand Royal Society Marsden Fund (to R. C. J. D.).

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- IL

- interleukin

- R

- receptor

- RMSD

- root-mean-square deviation

- JAK

- Janus kinase

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- CHR

- cytokine-binding homology region

- FnIII

- fibronectin type III

- SV-AUC

- sedimentation velocity–analytical ultracentrifugation

- SAXS

- small-angle X-ray scattering

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- PP2

- polyproline type II

- SEC-MALS

- multi-angle light scattering coupled with size-exclusion chromatography

- FD-AUC

- fluorescence-detected SV-AUC

- muGFP

- monomeric, ultrastable GFP

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- TLS

- translation/libration/screw.

References

- 1. Boulanger M. J., and Garcia K. C. (2004) Shared cytokine signaling receptors: structural insights from the GP130 system. Adv. Protein Chem. 68, 107–146 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)68004-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hibi M., Murakami M., Saito M., Hirano T., Taga T., and Kishimoto T. (1990) Molecular cloning and expression of an IL-6 signal transducer, gp130. Cell 63, 1149–1157 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90411-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taga T., and Kishimoto T. (1997) Gp130 and the interleukin-6 family of cytokines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 797–819 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Skiniotis G., Lupardus P. J., Martick M., Walz T., and Garcia K. C. (2008) Structural organization of a full-length gp130/LIF-R cytokine receptor transmembrane complex. Mol. Cell 31, 737–748 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boulanger M. J., Bankovich A. J., Kortemme T., Baker D., and Garcia K. C. (2003) Convergent mechanisms for recognition of divergent cytokines by the shared signaling receptor gp130. Mol. Cell 12, 577–589 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00365-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boulanger M. J., Chow D.-C., Brevnova E. E., Garcia K. C. (2003) Hexameric structure and assembly of the interleukin-6/IL-6 α-receptor/gp130 complex. Science 300, 2101–2104 10.1126/science.1083901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paul S. R., Bennett F., Calvetti J. A., Kelleher K., Wood C. R., O'Hara R. M. Jr., Leary A. C., Sibley B., Clark S. C., and Williams D.A. (1990) Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding interleukin 11, a stromal cell-derived lymphopoietic and hematopoietic cytokine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 7512–7516 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Putoczki T. L., Thiem S., Loving A., Busuttil R. A., Wilson N. J., Ziegler P.K., Nguyen P. M., Preaudet A., Farid R., Edwards K. M., Boglev Y., Luwor R. B., Jarnicki A., Horst D., Boussioutas A., et al. (2013) Interleukin-11 is the dominant Il-6 family cytokine during gastrointestinal tumorigenesis and can be targeted therapeutically. Cancer Cell 24, 257–271 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schafer S., Viswanathan S., Widjaja A. A., Lim W.-W., Moreno-Moral A., DeLaughter D. M., Ng B., Patone G., Chow K., Khin E., Tan J., Chothani S. P., Ye L., Rackham O. J. L., Ko N. S. J., et al. (2017) IL11 is a crucial determinant of cardiovascular fibrosis. Nature 552, 110–115 10.1038/nature24676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Widjaja A. A., Singh B. K., Adami E., Viswanathan S., Dong J., D'Agostino G. A., Ng B., Lim W. W., Tan J., Paleja B. S., Tripathi M., Lim S. Y., Shekeran S. G., Chothani S. P., Rabes A., et al. (2019) Inhibiting interleukin 11 signaling reduces hepatocyte death and liver fibrosis, inflammation, and steatosis in mouse models of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 157, 777–792.e14 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agthe M., Brügge J., Garbers Y., Wandel M., Kespohl B., Arnold P., Flynn C. M., Lokau J., Aparicio-Siegmund S., Bretscher C., Rose-John S., Waetzig G. H., Putoczki T., Grötzinger J., and Garbers C. (2018) Mutations in craniosynostosis patients cause defective interleukin-11 receptor maturation and drive craniosynostosis-like disease in mice. Cell Rep. 25, 10–18.e5 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nieminen P., Morgan N. V., Fenwick A. L., Parmanen S., Veistinen L., Mikkola M. L., van der Spek P. J., Giraud A., Judd L., Arte S., Brueton L. A., Wall S. A., Mathijssen I. M., Maher E. R., Wilkie A. O., et al. (2011) Inactivation of IL11 signaling causes craniosynostosis, delayed tooth eruption, and supernumerary teeth. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 67–81 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brischoux-Boucher E., Trimouille A., Baujat G., Goldenberg A., Schaefer E., Guichard B., Hannequin P., Paternoster G., Baer S., Cabrol C., Weber E., Godfrin G., Lenoir M., Lacombe D., Collet C., et al. (2018) IL11RA-related Crouzon-like autosomal recessive craniosynostosis in 10 new patients: resemblances and differences. Clin. Genet. 94, 373–380 10.1111/cge.13409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keupp K., Li Y., Vargel I., Hoischen A., Richardson R., Neveling K., Alanay Y., Uz E., Elcioğlu N., Rachwalski M., Kamaci S., Tunçbilek G., Akin B., Grötzinger J., Konas E., et al. (2013) Mutations in the interleukin receptor IL11RA cause autosomal recessive Crouzon-like craniosynostosis. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 1, 223–237 10.1002/mgg3.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fagerberg L., Hallström B. M., Oksvold P., Kampf C., Djureinovic D., Odeberg J., Habuka M., Tahmasebpoor S., Danielsson A., Edlund K., Asplund A., Sjöstedt E., Lundberg E., Szigyarto C. A., Skogs M., et al. (2014) Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 397–406 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barton V. A., Hall M. A., Hudson K. R., and Heath J. K. (2000) Interleukin-11 signals through the formation of a hexameric receptor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36197–36203 10.1074/jbc.M004648200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Putoczki T. L., Dobson R. C., and Griffin M. D. (2014) The structure of human interleukin-11 reveals receptor-binding site features and structural differences from interleukin-6. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 2277–2285 10.1107/S1399004714012267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morris R., Kershaw N. J., and Babon J. J. (2018) The molecular details of cytokine signaling via the JAK/STAT pathway. Protein Sci. 27, 1984–2009 10.1002/pro.3519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matadeen R., Hon W. C., Heath J. K., Jones E. Y., and Fuller S. (2007) The dynamics of signal triggering in a gp130–receptor complex. Structure 15, 441–448 10.1016/j.str.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schleinkofer K., Dingley A., Tacken I., Federwisch M., Müller-Newen G., Heinrich P. C., Vusio P., Jacques Y., and Grötzinger J. (2001) Identification of the domain in the human interleukin-11 receptor that mediates ligand binding. J. Mol. Biol. 306, 263–274 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Varghese J. N., Moritz R.L., Lou M. Z., Van Donkelaar A., Ji H., Ivancic N., Branson K.M., Hall N. E., and Simpson R. J. (2002) Structure of the extracellular domains of the human interleukin-6 receptor α-chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15959–15964 10.1073/pnas.232432399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bork P., Holm L., and Sander C. (1994) The immunoglobulin fold: structural classification, sequence patterns and common core. J. Mol. Biol. 242, 309–320 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krissinel E., and Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ortega A., Amorós D., and García de la Torre J. (2011) Prediction of hydrodynamic and other solution properties of rigid proteins from atomic- and residue-level models. Biophys. J. 101, 892–898 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brown R. J., Adams J. J., Pelekanos R. A., Wan Y., McKinstry W. J., Palethorpe K., Seeber R. M., Monks T. A., Eidne K. A., Parker M. W., and Waters M. J. (2005) Model for growth hormone receptor activation based on subunit rotation within a receptor dimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 814–821 10.1038/nsmb977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giese B., Roderburg C., Sommerauer M., Wortmann S. B., Metz S., Heinrich P. C., and Müller-Newen G. (2005) Dimerization of the cytokine receptors gp130 and LIFR analysed in single cells. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5129–5140 10.1242/jcs.02628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vollmer P., Oppmann B., Voltz N., Fischer M., and Rose-John S. (1999) A role for the immunoglobulin-like domain of the human IL-6 receptor: intracellular protein transport and shedding. Eur. J. Biochem. 263, 438–446 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee C. G., Hartl D., Matsuura H., Dunlop F. M., Scotney P. D., Fabri L. J., Nash A. D., Chen N. Y., Tang C. Y., Chen Q., Homer R. J., Baca M., and Elias J. A. (2008) Endogenous IL-11 signaling is essential in Th2- and IL-13-induced inflammation and mucus production. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 39, 739–746 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0053OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Seabrook S. A., and Newman J. (2013) High-throughput thermal scanning for protein stability: making a good technique more robust. ACS Comb. Sci. 15, 387–392 10.1021/co400013v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang X.-M., Wilkin J.-M., Boisteau O., Harmegnies D., Blanc C., Montero-Julian A. A., Jacques Y., Content J., and Vandenbussche P. (2002) Engineering and use of 32P-labeled human recombinant interleukin-11 for receptor binding studies. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 61–68 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2002.02622.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jung Y., Ahn H., Kim D. S., Hwang Y. R., Ho S. H., Kim J. M., Kim S., Ma S., and Kim S. (2011) Improvement of biological and pharmacokinetic features of human interleukin-11 by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 405, 399–404 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bobby R., Robustelli P., Kralicek A. V., Mobli M., King G. F., Grötzinger J., and Dingley A. J. (2014) Functional implications of large backbone amplitude motions of the glycoprotein 130-binding epitope of interleukin-6. FEBS J. 281, 2471–2483 10.1111/febs.12800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yao S., Smith D. K., Hinds M. G., Zhang J. G., Nicola N. A., and Norton R. S. (2000) Backbone dynamics measurements on leukemia inhibitory factor, a rigid four-helical bundle cytokine. Protein Sci. 9, 671–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]