Abstract

Purpose

CEST has become a preeminent technology for the rapid detection and grading of tumors, securing its widespread use in both laboratory and clinical research. However, many existing CEST MRI agents exhibit a sensitivity limitation due to small chemical shifts between their exchangeable protons and water. We propose a new group of CEST MRI agents, free-base porphyrins and chlorin, with large exchangeable proton chemical shifts from water for enhanced detection.

Methods

To test these newly identified CEST agents, we acquired a series of Z-spectra at multiple pH values and saturation field strengths to determine their CEST properties. The data were analyzed using the quantifying exchange using saturation power method to quantify exchange rates. After identifying several promising candidates, a porphyrin solution was injected into tumor-bearing mice, and MR images were acquired to assess detection feasibility in vivo.

Results

Based on the Z-spectra, the inner nitrogen protons in free-base porphyrins and chlorin resonate from −8 to −13.5 ppm from water, far shifted from the majority of endogenous metabolites (0–4 ppm) and Nuclear Overhauser enhancements (−1 to −3.5 ppm) and far removed from the salicylates, imidazoles, and anthranillates (5–12 ppm). The exchange rates are sufficiently slow to intermediate (500–9000 s−1) to allow robust detection and were sensitive to substituents on the porphyrin ring.

Conclusion

These results highlight the capabilities of free-base porphyrins and chlorin as highly upfield CEST MRI agents and provide a new scaffold that can be integrated into a variety of diagnostic or theranostic agents for biomedical applications.

Keywords: CEST imaging, contrast agents, free-base porphyrin, upfield-shifted protons, molecular imaging

1 |. INTRODUCTION

MRI is a uniquely valuable tool for visualizing soft tissue with high spatial and temporal resolution. In the clinic, MRI contrast agents are in routine use for detecting lesions based on highlighting tissue through altering the T1 or T2 MR relaxation times of water.1,2 CEST contrast agents represent an attractive alternative because these agents do not require inclusion of heavy metals and can instead provide contrast using exchangeable protons on metabolites or other organic diamagnetic molecules.3–6 Molecules that produce CEST contrast include a number of natural biomolecules, which suggest that biochemical pathways should be detectable using this contrast mechanism. Indeed, a number of biomolecules have been reported over the past few years. Elegant examples of diamagnetic CEST (diaCEST) agents include glucose,7,8 myo-inositol,9,10 glutamate,11,12 Cr,13 L-arginine,14,15 glycosaminoglycans,16 protamine,17 glycogen,18 and glycoproteins.19 Critical to the success of CEST imaging is selective irradiation of the labile protons while avoiding perturbation of bulk water signal and protons found in tissue. However, exchangeable protons of the aforementioned metabolites fall within 4 ppm from bulk water, which limit the use of selective saturation pulses and increase background signal. Further shifted protons for enhanced CEST contrast on lower field scanners can be found on molecules such as barbituric acid,20 iopamidol,21–23 and several thymidine analogues.24,25 More recently, significant progress was made by employing the intramolecular bond–shifted hydrogens principle.26–30 A number of anthranilates, imidazole-4,5 dicarboxyamides, and salicylates show strong CEST contrast properties, with labile protons resonating up to 12 ppm from water. Despite these promising advances, the development of diaCEST agents with the highly upfield shifted protons, which presents sensitivity advantages that also are well tolerated after administration, remains elusive.

Herein, we show that several properly substituted free-base porphyrins and a chlorin possess two protons that resonate at a remarkable −9 to −13.5 ppm from water. These CEST peaks are shifted well outside of the range of other known labile protons, and exchange rates are sufficiently slow to intermediate on the NMR timescale, making these agents well suited for CEST imaging. As far as we are aware, no other diamagnetic CEST agent has been reported at such low frequencies. Based on this finding, we evaluate the feasibility of visualizing a water-soluble porphyrin in mice bearing A549 cell-derived xenografts.

2 |. METHODS

Phantom preparation

δ-aminolevulinic acid, porphobilinogen, uroporphyrin I, coproporphyrin I, and protoporphyrin IX were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tetraphenylporphine sulfonate (TPPS4); 5, 10, 15, 20-tetrakis (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP); and chlorin e6 were purchased from J&K Scientific Ltd (Beijing, China). Hematoporphyrin were purchased from Binhai Hanhong Biochemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Metal salts were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). 5, 10, 15, 20-tetrakis(4-β-g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin was synthesized according to a previous report.31 All samples were dissolved in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline at the desired concentrations and then titrated using high concentration HCl/NaOH to the desired pH values. The solutions were placed into 1 mm glass capillaries and assembled in a holder for CEST MR imaging. The samples were kept in 37 °C during imaging. Phantom CEST experiments were taken on a Bruker 9.4 Tesla vertical MR scanner (Bruker Avance 400, Ettlingen, Germany), using a 25 mm birdcage transmit/receive coil. CEST images were acquired using a rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement factor = 8) sequence with continuous wave saturation pulse length of 3 seconds and saturation field strength (ω1) from 1.2 μT to 14.4 μT. The CEST Z-spectra were acquired by incrementing saturation frequency every 0.25 ppm from −16 to 16 ppm for phantoms; TR = 8 s, effective TE = 5.1 ms, matrix size = 128 * 96, and slice thickness = 3 mm. Water saturation shift referencing images were also acquired using 0.5 s continuous wave saturation pulse with field strength of 0.5 μT and saturation frequency from −1.6 ppm to 1.6 ppm with 23 scans.

Cell culture and cancer model

A549s, non-small-cell lung cancer cells, were purchased from the cell bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The tumor cells were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Boster, Wuhan, China), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Boster, Wuhan, China), 100 U/mL penicillin (Boster, Wuhan, China), and 100 U/mL streptomycin (Boster, Wuhan, China) in a humidified air with 5% CO2 at 37oC. BALB/c male nude mice (aged 5–6 weeks, approximately 20 g) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The mice were inoculated subcutaneously with A549 cells (1 * 106 cells of each) on the legs and used for MRI after 3 weeks breeding.

Animal imaging

Animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines provided and approved by the institutional review board of the Wuhan Institute of Physics and Mathematics (Wuhan, People’s Republic of China), Chinese Academy of Sciences. For MRI, BALB/c mice bearing A549-derived xenografts were anesthetized by using 0.5% to 2% isoflurane and placed in a 25 mm transmit/receive mouse coil. Breath rate was monitored throughout in vivo MRI experiments using a respiratory probe. A 50 μL volume of a 0.1 M TPPS4 solution (deionized water, pH 7) was slowly injected via a catheter into the tumor. In vivo images were acquired on a Bruker 9.4 Tesla vertical MR scanner (Bruker Avance 400), with 1 axial slice (2 mm thick) acquired near the center of the tumor. CEST images were collected both pre- and postinjection. Image parameters were similar to those for the phantom, except for TR/TE = 5 s/6.4 ms, with optimized ω1 = 5.4 μT. Water saturation shift referencing images were also acquired using 0.5 s continuous wave saturation pulse with field strength of 0.5 μT and saturation frequency from −1.6 ppm to 1.6 ppm. A 105-offset Z-spectrum (15 ppm to −15 ppm) was acquired using a saturation field strength of 3.6 μT. For the dynamic CEST contrast measurements, a series of whole Z-spectra and water saturation shift referencing experiments were acquired after injection.

Postprocessing

All postprocessing was performed using in-house written MatLab (Matlab R2014a, MathWorks, Natick, MA) scripts. CEST contrast was quantified in the images using:

| (1) |

S(−Δω) and S(+Δω) refer to the water signal intensity with a saturation pulse applied at the frequencies −Δω and +Δω, respectively. This definition is the reverse of that conventionally used by diaCEST studies due to the location of the protons of the porphyrin and chlorin agents on the opposite side of the water line from other diaCEST protons, as described previously. A voxel-by-voxel B0 map was generated, as described previously, using water saturation shift referencing images for phantoms and live animals.

To perform the multicontrast kinetic analysis, a region of interest was drawn over the CEST enhancing region and the data averaged over the 4 mice at each time point. The temporal evolution of the MTRasym (asymmetric magnetic transfer ratio) at −9.75 ppm was then fitted, as described previously,32 using the Levenburg Marquardt routine in MatLab (Matlab R2014a, MathWorks, Natick, MA) to the expression:

where

3 |. RESULTS

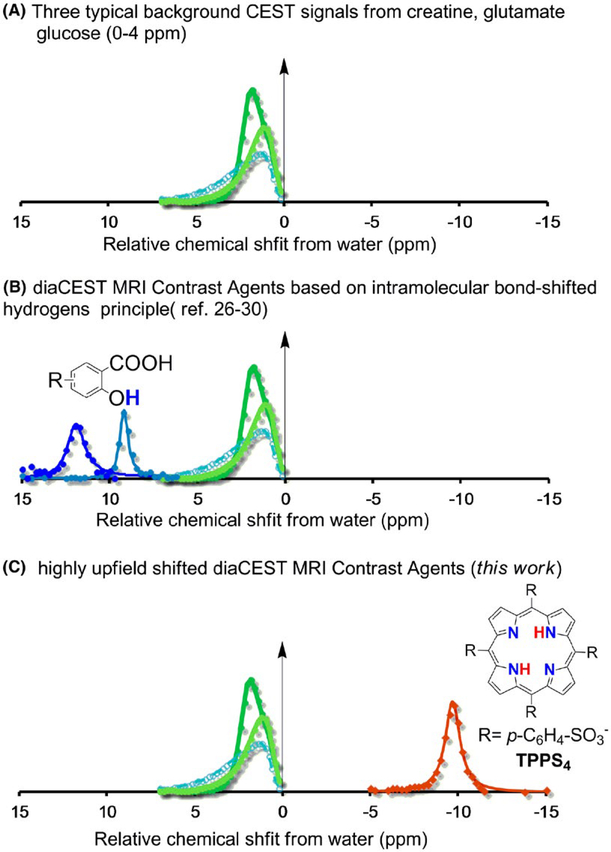

CEST-MRI contrast is generated by applying a selective RF pulse (saturation pulse) on labile protons to annihilate their magnetization. Due to dynamic proton exchange of the “saturated” labile protons with water transferring the saturation, there is a progressive loss in water signal with continuous replacement of the saturated protons by unsaturated protons followed by renewed annihilation of their signal. As a result, the low concentration labile protons display an amplified influence on water signal, the source of MRI signal. As shown in Figure 1A, Cr, glutamine, and glucose display strongly overlapped CEST contrast between 1 to 4 ppm at a saturation field strength (ω1) = 3.6 μT.33 As described previously, on 3 Tesla scanners saturation transfer contrast is improved for compounds with chemical shifts more than 5 ppm away from water.27 Suitable labile protons are found in aromatic compounds with intramolecular hydrogen bonds with two representative contrast curves from the intramolecular bond shifted hydrogens scaffold shown in Figure 1B. In our search for high chemical shift labile protons, we became interested in investigating free-base porphyrins, which are aromatic macrocycles that possess a very large magnetic anisotropy.34,35 As shown in Figure 1C, the MTRasym spectra of free-base TPPS4, a known 2nd generation photosensitizer,36 is well suited for detection via CEST imaging due to the central nitrogen (NH) protons on this compound. In fact, these fall within a region of the chemical shift spectrum far removed from all other diaCEST agents to date. Unlike the labile protons on other compounds, which fit these criteria, the NHs in TPPS4 possess a large upfield chemical shift from water (Δω = −9.75 ppm).

FIGURE 1.

Depiction of the spectral range for diamagnetic CEST agents discovered to date. (A) Three typical background CEST signals from creatine, glutamate, glucose (0–4 ppm); (B) diaCEST MRI Contrast Agents based on intramolecular bond-shifted hydrogens; (C) highly upfield shifted diaCEST MRI Contrast Agents (this work)

3.1 |. Characterization of porphyrin CEST contrast

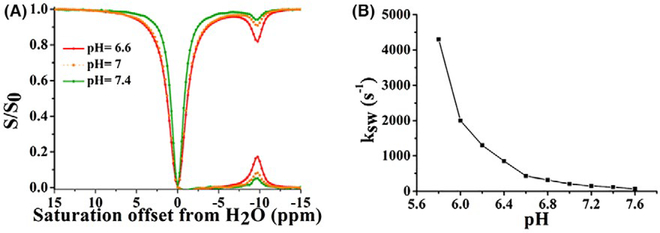

We first measured the CEST properties of TPPS4 in vitro. Figure 2A shows a Z-spectrum and MTRasym spectrum for the compound. The proton exchange rate (ksw) with water for TPPS4 was measured as a function of pH using the quantifying exchange using saturation power experiment.37 TPPS4 has a ksw = 0.21 ks−1 at 12.5 mM, pH = 7.0, with ksw strongly dependent on pH (Figure 2B). Above pH 6.0, ksw is below the chemical shift difference at 9.4 Tesla (Δω = 3900 Hz), placing the exchange rates in the slow-to-intermediate exchange NMR regime and making this agent well suited for CEST imaging (Supporting Information Figure S1) (Supporting Information Table S1). The concentration dependence of CEST contrast is linear, and 1.5% contrast was obtained at 2.5 mM using ω1 = 5.4 μT (Supporting Information Figure S2).

FIGURE 2.

CEST properties of TPPS4 at 37°C. A, Z-spectrum and MTRasym for 12.5 mM TPPS4 at pH 6.6, 7.0 and 7.4 using ω1 = 5.4 μT. B, pH dependence of ksw based on quantifying exchange using saturation power data of TPPS4. ω1, saturation field strength; TPPS4, tetraphenylporphine sulfonate

3.2 |. Porphyrins, chlorin and precursor CEST properties

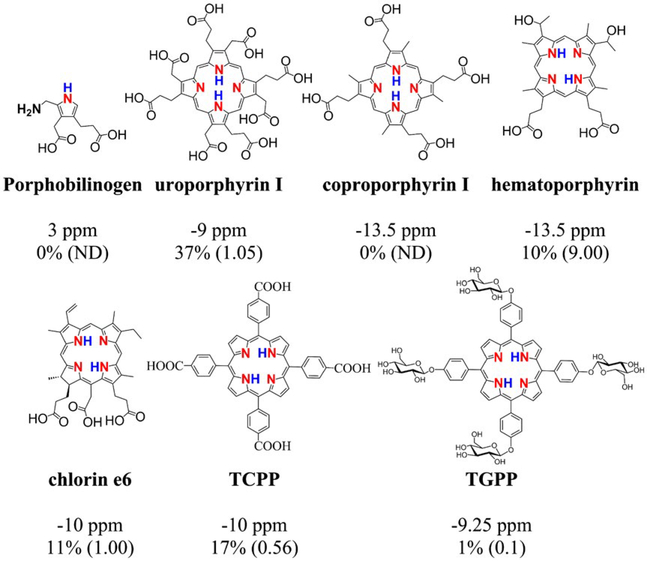

To get a better handle on what the range of CEST properties are for free-base porphyrins and chlorin, we tested the series shown in Figure 3 including the porphyrin precursor porphobilinogen in vitro. Isolated porphobilinogen possesses a pyrrole NH and displays modest contrast at Δω = 3 ppm (Supporting Information Figure S3). In contrast, uroporphyrin I, which has 8 carboxyl groups conjugated to the β positions on the porphyrin ring, has a pronounced CEST peak at Δω = −9 ppm, with ksw = 1.05 ks−1 at pH 7.4, placing the rates in the slow-to-intermediate NMR exchange regime and making this agent well suited for CEST imaging (Figure 3) (Supporting Information Figure S4) (Supporting Information Table S2). Coproporphyrin I is a downstream metabolite of uroporphyrin I, with methyl substitutions for 4 of the carboxyls (Figure 3) (Supporting Information Figure S5). These substitutions decrease the Δω further to −13.5 ppm from water; however, the ksw also increases such that the CEST peaks are poorly detected until pH 9.0 (Supporting Information Figure S5) (Supporting Information Table S3), making this porphyrin unsuitable as a CEST agent. Similarly, hematoporphyrin with its hydroxyl and methyl substitutions at the meso-positions on the ring provides minimal CEST contrast until pH 8.0 (Supporting Information Figure S6) (Supporting Information Table S4). Protoporphyrin IX, the final free-base porphyrin in heme biosynthesis, could not be tested because the water solubility was too low. We also tested chlorin e6, which is not aromatic through the entire circumference of the ring and has carboxyls at the meso- and β-positions. Chlorin e6 can provide suitable CEST contrast at neutral pH values with 2 different Δω = −10.25 and −8.75 ppm, with ksw = 0.85 and 0.20 ks−1, respectively (Supporting Information Figure S7) (Supporting Information Table S5). Because of these 2 frequencies, chlorin e6 has another interesting feature, a pH dependent contrast frequency, as can be seen in Supporting Information Figure S8. In addition to those natural porphyrins and TPPS4, we tested 2 additional synthetic water-soluble tetraphenylporphyrins, as shown in Figure 3: TCPP and 5, 10, 15, 20-tetrakis(4-β-g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin. The NH protons of TCPP show well-defined, sharp peaks at Δω = −10 ppm with sufficiently slow ksw values (TCPP, ksw = 0.56 ks−1, pH = 7.4) (Supporting Information Figure S9) (Supporting Information Table S6), placing these in the slow-to-intermediate exchange regime (i.e., ksw < Δω). NH protons of tetrakis(4-β-g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin resonate at a similar chemical shift (Δω = −9.25 ppm) but have a fairly slow exchange rate at neutral pH (ksw = 0.1 ks−1, pH = 7) (Supporting Information Figure S10) (Supporting Information Table S7). The magnitude of the CEST contrast increased when the pH dropped below 7 because of the particularly high exchange rates (TCPP, ksw = 3.3 ks−1, pH = 6.6). The results of all the ksw measurements are listed in Supporting Information Tables S1 through 7. Based on all these data, uroporphyrin I, TPPS4, and TCPP all display well-defined CEST peaks with excellent water solubilities. Unfortunately, the water solubility of TCPP is severely limited below pH 6.6, a problem for in vivo applications. Therefore, we settled on TPPS4 for further studies.

FIGURE 3.

CEST signals [ppm] and contrast [%] (exchange rate [ks−1]) of porphobilinogen, uroporphyrin I, coproporphyrin I, hematoporphyrin, chlorin e6, TCPP, TGPP. Experimental conditions: CEST agent concentration = 12.5 mM (25 mM for uroporphyrin I); pH = 7.4, using tsat = 3 s, ω1 = 5.4 μT. For Z-spectra and QUESP fitting at different pH, see the Supporting Information. Porphobilinogen is the fundamental biological pyrrole precursor to a rich spectrum of tetrapyrrole pigments (porphyrins, corrins, chlorins). TCPP, tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin; TGPP, tetrakis(4-β-g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin

As has been observed previously, porphyrins present several complications as contrast agents, including a tendency to ligate metals at the axial site, which would displace the labile protons used to create CEST contrast; a tendency to self-aggregate; and in general a limited water solubility.35 We tested this for TPPS4 by acquiring Z-spectra after simply mixing 1 eq. metal salts with TPPS4 in solution at 37 °C for 4 h under constant shaking and titrated to neutral pH using high-concentration HCl/NaOH. As shown in the Supporting Information Figure S11, this procedure did not result in the formation of metal complexes which eliminated the CEST signals. In addition, we have tested the influence of human serum on TPPS4. MR data was acquired on 10% normalized human serum titrated to pH 7.3 with and without 12.5 mM TPPS4. As seen in the Supporting Information Figure S12, at this concentration Human serum albumin does not interfere with the CEST signal of TPPS4.

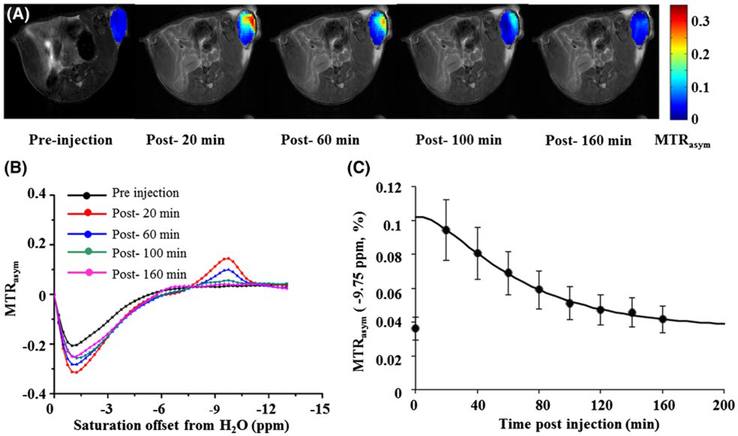

3.3 |. In vivo imaging of tumor xenografts

To test how well these upfield CEST agents could be detected, we performed an in vivo study in live BALB/c mice bearing A549 cells-derived xenografts. We administered 50 μL of a 0.1 M TPPS4 solution, a known photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy,38 through intratumoral injection. CEST images were acquired before and after administration, revealing the distribution of TPPS4 within the tumor. The peak CEST contrast was 9.5% contrast at −9.75 ppm after injection of TPPS4 and markedly decreased over 3 h (Figure 4C) (Supporting Information Figure S13) (Supporting Information Table S8–9). The advantage of the remarkable upfield signal is evident from Figure 4B, where the peak of TPPS4 is far removed from background saturation transfer signals detected as negative MTRasym values from 0 to −6 ppm. In addition, using ω1 = 3.6 μT, the water signal at −9.75 ppm is 20% larger compared to at −5 ppm, which improves the contrast-to-noise ratio of the CEST images as well. The dynamics are similar to those found for intratumoral injection of CEST stealth liposomes previously, with k1 = 7.83 × 10−1 hr−1 and k2 = 9.98 × 10−2 hr−1 (rate constants with k1 corresponding to the cellular uptake of the porphyrin from extracellular space though endocytosis; k2 corresponding to release of the porphyrin into the intracellular vesicle space). For the larger lipoCEST agent, these values were k1 = 1.73 × 10−2 hr−1 and k2 = 3.82 × 10−2 hr−1 using Castelli et al.’s multicontrast kinetic analysis model.32 Overall, these CEST imaging results are encouraging and should enable use of more advanced saturation methods at clinical field strengths in future studies.39–42

FIGURE 4.

In vivo contrast for the TPPS4. A, −9.75 ppm CEST contrast maps at pre- and post-20 min, post-60 min, post-100 min, and post-160 min injection of compound TPPS4. B, MTRasym for a ROI enclosing the entire tumor with preinjection data (black), 20 min postinjection (red), 60 min postinjection (blue), 100 min postinjection (green), 160 min postinjection (pink). C, Temporal evolution of the MTRasym (−9.75 ppm) for ROIs enclosing the whole tumor after intrathecal injection of TPPS4. ω1 = 3.6 μT (n = 4). ROI, region of interest

4 |. DISCUSSION

We have shown that selected porphyrins and chlorin display excellent CEST MRI properties, with hematoporphyrin-possessing labile protons that are the furthest shifted diaCEST agent identified to date, further than the previously identified 3-nitrosalicylic acid.27 Normally, the protons on heteroaromatic rings such as pyrrole, aniline, and imidazole resonate downfield from water due to the strong de-shielding effect from the aromatic ring. The de-shielding effect can be further enhanced using intramolecular hydrogen bonding, which is a powerful strategy to increase the sensitivity of CEST imaging. As we show in this work, the inner NH protons in the center of aromatic porphyrins and chlorin instead are highly upfield-shifted, with inner labile NH resonating as much as 17 ppm higher field than NH resonances in pyrroles or on lysine or arginine-rich peptides. These unusual shifts are largely attributed to the effect of “ring currents” formed by the precession of 18 π-electrons in the porphyrin ring, as previously described by Jusélius and Sundholm using density-functional theory.34,35,43–45 The ksws for a number of these molecules are suitable to allow robust detection, with the substitution of the ring playing an important role in determining both the labile proton shift and ksw, as shown by our data.

In a number of recent studies, the triiodobenzene analogues21,22 and thymidine analogues24,25 were extensively investigated and shown to have great potential for biomedical applications. These downfield shifted agents suffer a little still from overlap with background signals from endogenous exchangeable protons on clinical 3 Tesla scanners. There are less background signals occurring in upfield regions of the spectra, except for the relay nuclear Overhauser enhancements from −1 to −3.5 ppm,46 which may be a major advantage for specific detection. While Nd3+ and Pr3+, Tb3+ and Ho3+ paramagnetic CEST agents can also contain labile protons or water molecules with strong upfield shifts,47,48 the ksws for these complexes are generally much faster than the 400 to 2000 s−1, which are well detected by the moderate strength saturation pulses generated using body coils on clinical 3 Tesla scanners.

A number of free-base porphyrins are metabolites from heme biosynthesis. Because of this, using CEST imaging to detect these compounds could provide information on metabolic disorders such as porphyria. Furthermore, photomedicine, which includes optical image guidance of surgeries49 and photodynamic therapies,50 employs these or similar compounds. Our findings potentially allow inserting MRI into photomedicine for enhanced visualization. In addition, because a wide variety of free-base porphyrins possess favorable properties for detection using CEST imaging, conjugation of these probes to water-soluble polymers,51 liposomes,52,53 or incorporation into micelles54,55 should preserve the CEST properties, allowing their use for a wide variety of multimodal diagnostic and theranostic studies.

5 |. CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that porphyrins and chlorin are a promising new set of diaCEST probes with chemical shifts far upfield from conventional organic CEST agents. The temporal evolution of the contrast detected is similar to observed before for paraCEST agents using a multicontrast kinetic analysis.32 This type of highly upfield shifted probe could improve the sensitivity of existing CEST methods. More MRI studies on the pharmacokinetics and tumor uptake of porphyrins are now under investigation in our labs.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE S1 Influence of pH on the contrast of TPPS4 (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S2 Influence of concentration on the contrast of TPPS4. The concentration dependence of the contrast of TPPS4 at pH 7.0–7.2 was measured at a saturation field strength (ω1) = 5.4 μT. The Z‐spectra and MTRasym spectra at concentrations 0 mM,1.25 mM, 2.5 mM, 5 mM, 7.5 mM, 10 mM, 15mM and 20 mM were collected and are shown below. 1.5% contrast was obtained at 2.5 mM

FIGURE S3 Influence of pH on the contrast of porphobilinogen (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S4 pH effect on the contrast of uroporphyrin I (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S5 Influence of pH on the contrast of coproporphyrin I (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S6 Influence of pH on the contrast of hematoprophyrin (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S7 Influence of pH on the contrast of Chlorin e6 (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S8 Z‐spectra and MTRasym of Chlorin e6 using different saturation field strengths. The saturation power dependence of the contrast of Chlorin e6 at pH 7.0 was measured using different saturation field strength. The Z‐spectra and MTRasym spectra using ω1 = 1.2 μT, 2.4 μT, 3.6 μT, 5.4 μT, 7.2 μT, 10.8 μT and 14.4 μT were collected and are shown below. Two peaks were observed at −8.75 ppm and −10.25 ppm when weak saturation power (ω1 = 1.2 μT, 2.4 μT, 3.6 μT or 5.4 μT) was employed [dummy_incomplete para]

FIGURE S9 Influence of pH on the contrast of TCPP (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S10 Influence of pH on the contrast of 5, 10, 15, 20‐tetraki (4‐β‐g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S11 CEST contrast of TPPS4 in the presence of various metal ions (1 eq.). The effect of metal ions on the contrast of TPPS4 were tested at a concentration of 12.5 mM, pH = 7, ω1 = 5.4 μT. After simply mixed metal ions with TPPS4 solution at 37°C for 4 h under constant shaking and titrated using high‐concentration HCl/NaOH to neutral pH, the Z‐spectra in presence of 1 eq. metal salts include ZnCl2, CaCl2, MgCl2, CdCl2 and AlCl3 were collected [dummy_incomplete para]

FIGURE S12 In vitro test of TPPS4 in the presence of 10% HSA (pH = 7.3, 37 °C, 5.4 μT, 3 s for saturation)

FIGURE S13 In vivo Z‐spectra and MTRasym spectra for the tumor of mouse 2 with data collected pre‐injection and post injection. a) Z‐spectra of tumor at different time points (pre, 20 min, 40 min, 60 min, 80 min, 100 min, 120 min, 140 min and 160 min); b) MTRasym of tumor at different time points. For these experiments, 50 μl of 0.1 M TPPS4 solution was injected into mouse through Intratumoral (IT) injections. Before injection, the B0 inhomogeneity was measured and corrected using the water saturation shift referencing approach. An 105‐offset Z‐spectrum (from 15 ppm to −15 ppm) was also acquired using saturation field strength of 3.6 μT. For the dynamic CEST contrast measurements, a series of whole Z‐spectra and water saturation shift referencing experiments were acquired after injection. The CEST contrast map was calculated by MTRasym = [S(+Δω)–S(−Δω)]/S(+Δω). The images at every three adjacent time points were averaged to increase the contrast‐noise‐ratio. The maximum CEST contrast at −9.75 ppm was up to 14.5% after injection of TPPS4 and markedly decreased over 3 hours. The contrast map before and after injection are showed in Supporting Information Table S8 and S9 [dummy_incomplete para]

TABLE S1 Measured proton exchange rates of TPPS4 at different pH values

TABLE S2 Measured proton exchange rates of uroporphyrin I at different pH

TABLE S3 Measured proton exchange rates of coproporphyrin I at different pH

TABLE S4 Measured proton exchange rates of hematoporphyrin at different pH

TABLE S5 Measured proton exchange rates of Chlorin e6 at different pH

TABLE S6 Measured proton exchange rates of TCPP at different pH

TABLE S7 Measured proton exchange rates of 5, 10, 15, 20‐tetraki (4‐β‐g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin at different pH

TABLE S8 T2w map and CEST contrast map of Mouse 1 and Mouse 2

TABLE S9 T2w map and CEST contrast map of Mouse 3 and Mouse 4

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81625011, 81227902), National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC1304700 and 2017YFA0505400), and Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDY-SSW-SLH018). X.Z. acknowledges the support by the National Program for Support of Eminent Professionals (National Program for Support of Top-notch Young Professionals). M.T.M. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (grant P41EB024495).

Funding information

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81625011, 81227902), National Key R&D Program of China (grants 2016YFC1304700 and 2017YFA0505400), and Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS (grant QYZDY-SSW-SLH018). x.z. acknowledges support from the National Program for Support of Eminent Professionals (National Program for Support of Top-notch Young Professionals). M.T.M. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (grant P41EB024495).

REFERENCES

- 1.Harisinghani MG, Barentsz J, Hahn PF, et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2491–2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boros E, Gale EM, Caravan P. MR imaging probes: design and applications. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:4804–4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J Magn Reson. 2000;143:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PC. Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer Imaging-Advances and Application. Singapore: Pan Stanford Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S, Merritt M, Woessner DE, Lenkinski RE, Sherry AD. PARACEST agents: modulating MRI contrast via water proton exchange. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:783–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aime S, Castell DD, Crich AG, Gianolio E, Terreno E. Pushing the sensitivity envelope of lanthanide-based magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents for molecular imaging applications. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:822–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan KWY, McMahon MT, Kato Y, et al. Natural D-glucose as a biodegradable MRI contrast agent for detecting cancer. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68:1764–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker-Samuel S, Ramasawmy R, Torrealdea F, et al. In vivo imaging of glucose uptake and metabolism in tumors. Nat Med. 2013;19:1067–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haris M, Cai K, Singh A, Hariharan H, Reddy R. In vivo mapping of brain myo-inositol. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2079–2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haris M, Singh A, Cai K, et al. MICEST: A potential tool for noninvasive detection of molecular changes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Methods. 2013;212:87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai K, Haris M, Singh A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med. 2012;18:302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogan F, Singh A, Debrosse C, et al. Imaging of glutamate in the spinal cord using GluCEST. Neuroimage. 2012;77:262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haris M, Singh A, Cai K, et al. A technique for in vivo mapping of myocardial creatine kinase metabolism. Nat Med. 2014;20:209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan KWY, Liu G, Song X, et al. MRI-detectable pH nanosensors incorporated into hydrogels for in vivo sensing of transplanted-cell viability. Nat Mater. 2013;12:268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu G, Moake M, Har-el Y, et al. In vivo multicolor molecular MR imaging using diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer liposomes. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1106–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchangedependent saturation transfer (gagCEST). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2266–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-Shir A, Liu G, Chan KWY, et al. Human protamine-1 as an MRI reporter gene based on chemical exchange. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:134–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Zijl PC, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MRI detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4359–4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song X, Airan RD, Arifin DR, et al. Label-free in vivo molecular imaging of underglycosylated mucin-1 expression in tumor cells. Nat Comm. 2015;6:6719–6726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan KWY, Yu T, Qiao Y, et al. A diaCEST MRI approach for monitoring liposomal accumulation in tumors. J Control Release. 2014;180:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aime S, Calabi L, Biondi L, et al. Iopamidol: exploring the potential use of a well-established X-Ray contrast agent for MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longo DL, Dastrù W, Digilio G, et al. Iopamidol as a responsive MRI-chemical exchange saturation transfer contrast agent for pH mapping of kidneys: in vivo studies in mice at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longo DL, Sun PZ, Consolino L, Michelotti FC, Uggeri F, Aime S. A general MRI-CEST ratiometric approach for pH imaging: demonstration of in vivo pH mapping with iobitridol. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:14333–14336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bar-Shir A, Liu G, Liang Y, et al. Transforming thymidine into a magnetic resonance imaging probe for monitoring gene expression. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;138:1617–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bar-Shir A, Liu G, Greenberg MM, Bulte JWM, Gilad AA. Synthesis of a probe for monitoring HSV1-tk reporter gene expression using chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2380–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Song X, Li Y, et al. Salicylic acid and analogues as diaCEST MRI contrast agents with highly shifted exchangeable proton frequencies. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:8116–8119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X, Yadav NN, Song X, et al. Tuning phenols with intra-molecular bond shifted hydrogens (IM-SHY) as diaCEST MRI contrast agents. Chem Eur J. 2014;20:15824–15832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Feng X, Zhu W, et al. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) agents: quantum chemistry and MRI. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lesniak WG, Oskolkov N, Song X, et al. Salicylic acid conjugated dendrimers are a tunable, high performance CEST MRI nano platform. Nano Lett. 2016;16:2248–2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang X, Song X, Ray Banerjee S, et al. Developing imidazoles as CEST MRI pH sensors. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2016;11:304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oulmi D, Maillard P, Guerquin-Kern J, Huel C, Momenteau M. Glycoconjugated porphyrins. 3. synthesis of flat amphiphilic mixed meso- (glycosylated aryl) arylporphyrins and mixed meso- (glycosylated aryl) alkylporphyrins bearing some mono- and disaccharide groups. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1554–1564. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castelli DD, Dastrù W, Terreno E, et al. In vivo MRI multicontrast kinetic analysis of the uptake and intracellular trafficking of paramagnetically labeled liposomes. J Control Release. 2014;144:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan KWY, Jiang Lu, Cheng M, et al. CEST-MRI detects metabolite levels altered by breast cancer cell aggressiveness and chemotherapy response. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:806–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker ED, Bradley RB. Effects of “ring currents” on the NMR spectra of porphyrins. J Chem Phys. 1959;31:1413–1414. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker ED, Bradley RB, Watson CJ. Proton magnetic resonance studies of porphyrins. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:3743–3748. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abrahamse H, Hamblin MR. New photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Biochem J. 2016;473:347–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Zhou J, Sun PZ, Bulte JWM, van Zijl PC. Quantifying exchange rates in chemical exchange saturation transfer agents using the saturation time and saturation power dependencies of the magnetization transfer effect on the magnetic resonance imaging signal (QUEST and QUESP): pH calibration for poly-L-lysine and a starburst dendrimer. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kou J, Dou D, Yang L. Porphyrin photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy and its applications. Oncotarget. 2017;8:81591–815603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheidegger R, Vinogradov E, Alsop DC. Amide proton transfer imaging with improved robustness to magnetic field inhomogeneity and magnetization transfer asymmetry using saturation with frequency alternating RF irradiation. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:1275–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vinogradov E, He H, Lubag A, Balschi JA, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE. MRI detection of paramagnetic chemical exchange effects in mice kidneys in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman JI, McMahon MT, Stivers JT, Van Zijl PC. Indirect detection of labile solute proton spectra via the water signal using frequency-labeled exchange (FLEX) transfer. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1813–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zu Z, Janve VA, Xu J, Does MD, Gore JC, Gochberg DF. Imaging amide proton transfer and nuclear Overhauser enhancement using chemical exchange rotation transfer (CERT). Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:637–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheer H, Katz JJ. Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins In: Smith KM, ed. Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1976:399–514. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis J, Jackson AH, Kenner GW, Lee J. Porphyrin nuclear magnetic resonance spectra. Tetrahedron Lett. 1960;1:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jusélius J, Sundholm D. The aromatic pathways of porphins, chlorins and bacteriochlorins. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2000;2: 2145–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones CK, Huang A, Xu J, et al. Nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) imaging in the human brain at 7T. Neuroimage. 2013;77:114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aime S, Barge A, Delli Castelli D, et al. Paramagnetic lanthanide(III) complexes as pH-sensitive chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast agents for MRI applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:639–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang SR, Sherry AD. Physical characteristics of lanthanide complexes that act as magnetization transfer (MT) contrast agents. J Solid State Chem. 2003;17:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vahrmeijer AL, Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, van de Velde C, Frangioni JV. Image-guided cancer surgery using near-infrared fluorescence. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lucky SS, Soo KC, Zhang Y. Nanoparticles in photodynamic therapy. Chem Rev. 2015;115:1990–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Wei G, Zhang X, Xu F, Xiong X, Zhou S. A step-bystep multiple stimuli-responsive nanoplatform for enhancing combined chemo-photodynamic therapy. Adv Mater. 2017;28: 1605357–1605365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, et al. Porphysome nanovesicles generated by porphyrin bilayers for use as multimodal biophotonic contrast agents. Nat Mater. 2011;10:324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.En KK, Lovell JF, Zheng G. Lipoprotein-inspired nanoparticles for cancer theranostics. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:1105–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Jeon M, Rich LJ, et al. Non-invasive multimodal functional imaging of the intestine with frozen micellar naphthalocyanines. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9:631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Wang D, Goel S, et al. Surfactant-stripped frozen pheophytin micelles for multimodal gut imaging. Adv Mater. 2017;28:8524–8530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 Influence of pH on the contrast of TPPS4 (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S2 Influence of concentration on the contrast of TPPS4. The concentration dependence of the contrast of TPPS4 at pH 7.0–7.2 was measured at a saturation field strength (ω1) = 5.4 μT. The Z‐spectra and MTRasym spectra at concentrations 0 mM,1.25 mM, 2.5 mM, 5 mM, 7.5 mM, 10 mM, 15mM and 20 mM were collected and are shown below. 1.5% contrast was obtained at 2.5 mM

FIGURE S3 Influence of pH on the contrast of porphobilinogen (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S4 pH effect on the contrast of uroporphyrin I (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S5 Influence of pH on the contrast of coproporphyrin I (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S6 Influence of pH on the contrast of hematoprophyrin (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S7 Influence of pH on the contrast of Chlorin e6 (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S8 Z‐spectra and MTRasym of Chlorin e6 using different saturation field strengths. The saturation power dependence of the contrast of Chlorin e6 at pH 7.0 was measured using different saturation field strength. The Z‐spectra and MTRasym spectra using ω1 = 1.2 μT, 2.4 μT, 3.6 μT, 5.4 μT, 7.2 μT, 10.8 μT and 14.4 μT were collected and are shown below. Two peaks were observed at −8.75 ppm and −10.25 ppm when weak saturation power (ω1 = 1.2 μT, 2.4 μT, 3.6 μT or 5.4 μT) was employed [dummy_incomplete para]

FIGURE S9 Influence of pH on the contrast of TCPP (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S10 Influence of pH on the contrast of 5, 10, 15, 20‐tetraki (4‐β‐g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin (ω1 = 5.4 μT, tsat = 3 s, 12.5 mM)

FIGURE S11 CEST contrast of TPPS4 in the presence of various metal ions (1 eq.). The effect of metal ions on the contrast of TPPS4 were tested at a concentration of 12.5 mM, pH = 7, ω1 = 5.4 μT. After simply mixed metal ions with TPPS4 solution at 37°C for 4 h under constant shaking and titrated using high‐concentration HCl/NaOH to neutral pH, the Z‐spectra in presence of 1 eq. metal salts include ZnCl2, CaCl2, MgCl2, CdCl2 and AlCl3 were collected [dummy_incomplete para]

FIGURE S12 In vitro test of TPPS4 in the presence of 10% HSA (pH = 7.3, 37 °C, 5.4 μT, 3 s for saturation)

FIGURE S13 In vivo Z‐spectra and MTRasym spectra for the tumor of mouse 2 with data collected pre‐injection and post injection. a) Z‐spectra of tumor at different time points (pre, 20 min, 40 min, 60 min, 80 min, 100 min, 120 min, 140 min and 160 min); b) MTRasym of tumor at different time points. For these experiments, 50 μl of 0.1 M TPPS4 solution was injected into mouse through Intratumoral (IT) injections. Before injection, the B0 inhomogeneity was measured and corrected using the water saturation shift referencing approach. An 105‐offset Z‐spectrum (from 15 ppm to −15 ppm) was also acquired using saturation field strength of 3.6 μT. For the dynamic CEST contrast measurements, a series of whole Z‐spectra and water saturation shift referencing experiments were acquired after injection. The CEST contrast map was calculated by MTRasym = [S(+Δω)–S(−Δω)]/S(+Δω). The images at every three adjacent time points were averaged to increase the contrast‐noise‐ratio. The maximum CEST contrast at −9.75 ppm was up to 14.5% after injection of TPPS4 and markedly decreased over 3 hours. The contrast map before and after injection are showed in Supporting Information Table S8 and S9 [dummy_incomplete para]

TABLE S1 Measured proton exchange rates of TPPS4 at different pH values

TABLE S2 Measured proton exchange rates of uroporphyrin I at different pH

TABLE S3 Measured proton exchange rates of coproporphyrin I at different pH

TABLE S4 Measured proton exchange rates of hematoporphyrin at different pH

TABLE S5 Measured proton exchange rates of Chlorin e6 at different pH

TABLE S6 Measured proton exchange rates of TCPP at different pH

TABLE S7 Measured proton exchange rates of 5, 10, 15, 20‐tetraki (4‐β‐g1ucosylphenyl) porphyrin at different pH

TABLE S8 T2w map and CEST contrast map of Mouse 1 and Mouse 2

TABLE S9 T2w map and CEST contrast map of Mouse 3 and Mouse 4