Abstract

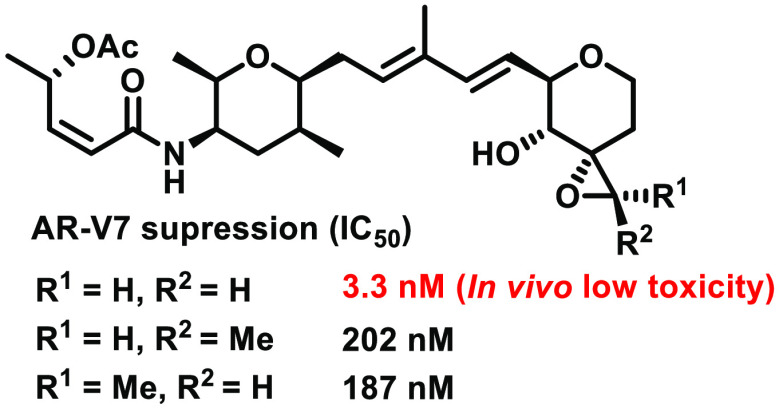

We designed and synthesized a novel 1,2-deoxy-pyranose and terminal epoxide methyl substituted derivatives of spliceostatin A using Julia–Kocienski olefination as a key step. With respect to the biological activity, the 1,2-deoxy-pyranose analogue of spliceostatin A suppressed AR-V7 expression at the nano level (IC50 = 3.3 nM). In addition, the in vivo toxicity test showed that the 1,2-deoxy-pyranose analogue was able to avoid severe toxicity compared to spliceostatin A.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, splicing, splicing variant, spliceostatin A, toxicity

In men, one of most common cancers is prostate cancer, which is treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, after ADT, most of them develop castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). These CRPC patients are then treated with hormonal therapies using androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathway inhibitors such as enzalutamide or abiraterone, but many CRPC patients become resistant to these medicines after a few years.1−3 One of the reasons for the resistance is the expression of the splicing variant of AR, specifically AR-V7, which gets activated constitutively without hormone ligands and promotes prostate cancer growth.4,5 Therefore, the development of inhibitors targeting AR-V7 expression is important for drug resistant CRPC therapy, and, to this end, some inhibitors have been developed (SF3b complex inhibitor and ROR-γ antagonist).6−10

Previously, it was discovered that the target protein of the splicing modulators spliceostatin A (1) (Figure 1), pladienolide B, and GEX1A (herboxidiene) (Scheme S1), which showed strong antitumor activity toward solid tumors in mice and several cancer cells, was an SF3b complex in U2SnRNP (main factor of pre-mRNA splicing).11−19 Until now, several synthetic studies (including analog synthesis) and mRNA splicing inhibition activity studies of 1, pladienolide B, and GEX1A have been conducted by several research groups,20−37 but there are only a few reports of splicing modulators which can inhibit the expression of AR-V7.

Figure 1.

Structure of spliceostatin A and its derivatives (1–5).

Recently, our group and the Hsieh group discovered that 1 and its relative pladienolide B and thailanstatins (Scheme S1) can inhibit the expression of AR-V7.6−8 Specifically pladienolide B significantly reduced the tumor volume of CRPC model mice overexpressing AR-V7.7 However, pladienolide B analogue E7107 entered phase I clinical trials, and as a result some patients suffered from vision loss.38,39 Consequently, we focused our research on 1 and its derivatives.40 Very recently, we designed and synthesized 2 which was more easily synthesized and acid stable than 1 but had weak AR-V7 suppression inhibitory activity (IC50 = 132 nM).8 To discover easily synthesizable derivatives of 1 with potent AR-V7 suppression inhibitory activity, we designed and synthesized new derivatives 3–5 based on much more detailed theoretical considerations.41

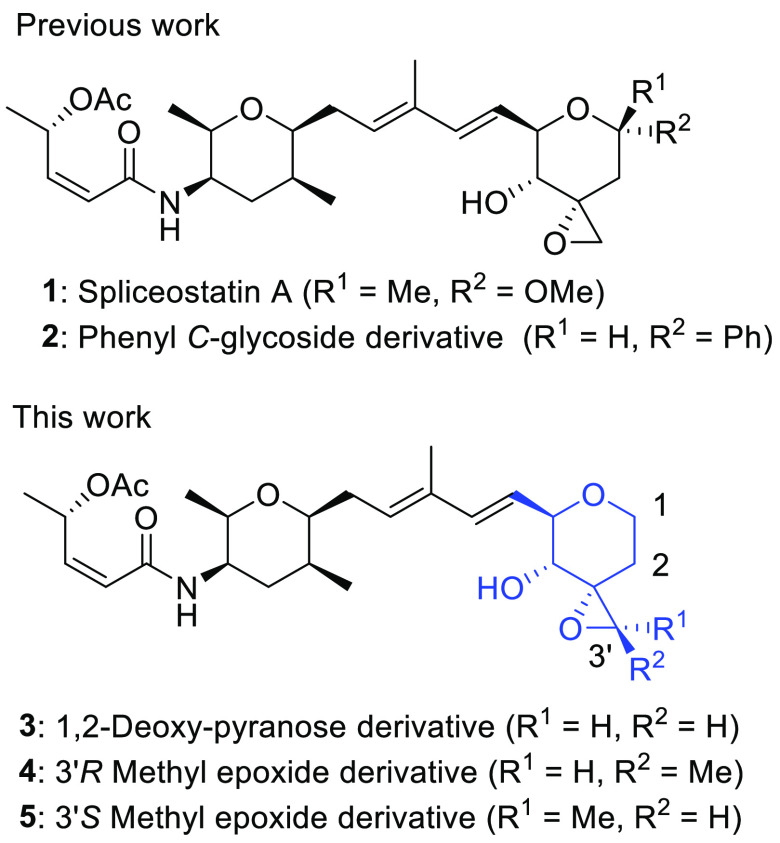

Our considerations in designing derivatives 3–5 are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Design strategy for derivatives 3–5.

For 3, the AR-V7 expression inhibitory activity of phenyl-C-glycoside derivative 2 was weaker than that of 1. We hypothesized that the weaker biological activity could be due to the presence of the bulky phenyl group, and therefore, we designed 1,2-deoxy-pyranose derivative 3 which had no functional group at the anomeric site and could have higher acid stability than 1. In addition, it was considered that the C1 unsubstituted pyran fragment of 3 could be synthesized more easily than the C1 methyl ketal pyran fragment of 1. (Figure 1a).

For 4 and 5, we hypothesized that the presence of the terminal epoxide of 1 and/or 2 was required for biological activity expression. However, the epoxide is typically associated with instability or toxicity derived from off-target effects (forming covalent bonding with amino acid residues of other proteins).42 Thus, we designed derivatives 4 (3′R) and 5 (3′S) to a methyl group on the epoxide of derivative 3 (Figure 2b), which could improve the stability of the epoxide.

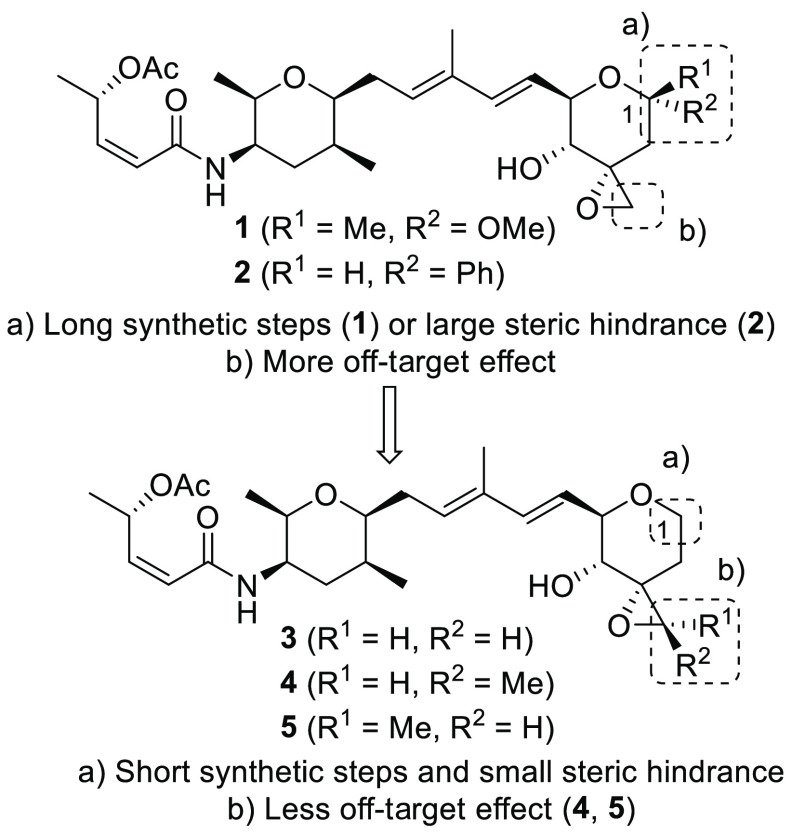

Scheme 1 illustrates our retrosynthetic analysis for 3–5. An internal double bond on C7 and C8, was constructed by Julia–Kocienski olefination between an appropriate aldehyde 9, 10, or 12(8)) and a sulfone (1121 or 6–8). The structures 6–10 were prepared from the corresponding olefins 13–15 by diastereoselective direct epoxidation, and the olefins 13–15 could be prepared by a Wittig reaction of the corresponding ketone, which was derived from d-glucal.

Scheme 1. Retrosynthetic Analysis for 3–5.

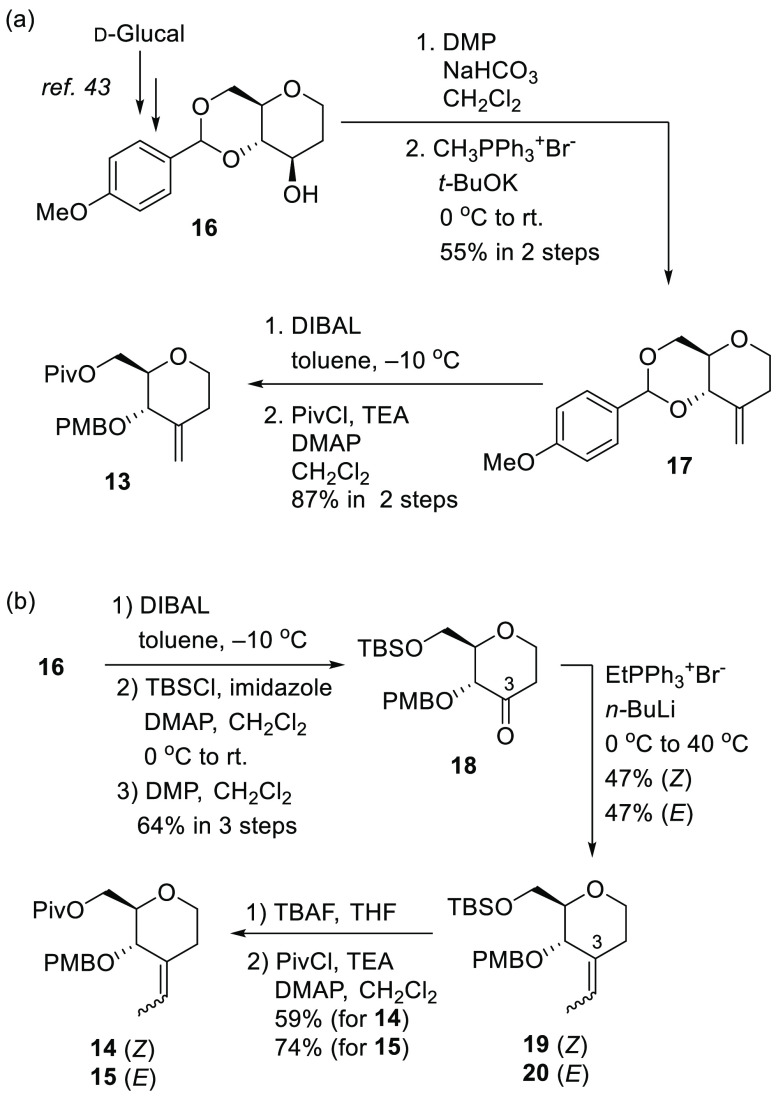

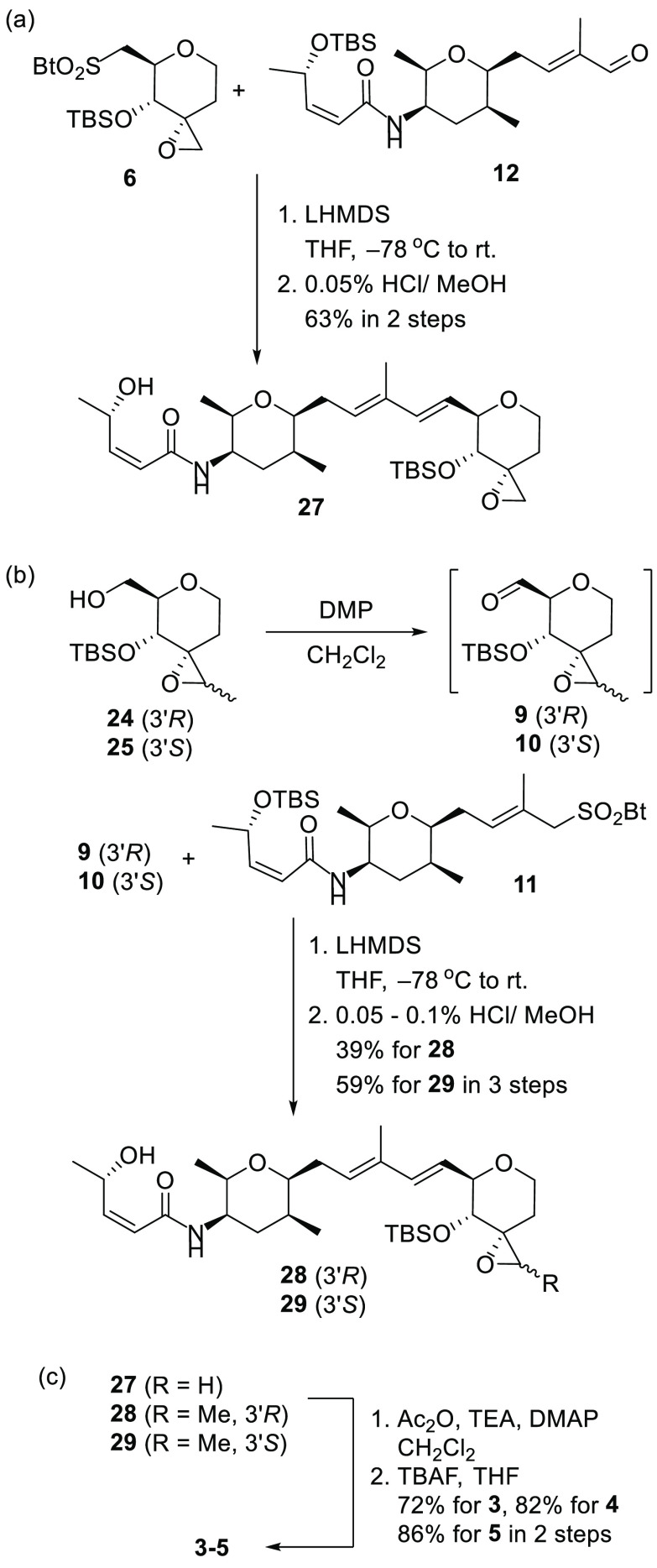

The synthesis of olefin key intermediates 13–15 is summarized in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. (a) Synthesis of Intermediate 13 and (b) Synthesis of Intermediates 14 and 15.

For 13 in Scheme 2a, the hydroxy group of the protected 1,2-deoxy pyranose 16, which was prepared from commercially available d-glucal,43 was oxidized to the corresponding ketone with Dess–Martin periodinane (DMP) and the subsequent Wittig reaction produced the olefin 17 in 55% yield over two steps. The p-methoxy benzyl acetal 17 was reduced to the corresponding primary alcohol by i-Bu2AlH (DIBAL) at −10 °C, and the generated primary alcohol was protected with t-BuCOCl (PivCl) to generate 13 in 87% yield (two steps).

For 14 and 15 in Scheme 2b, the acetal 16 was reduced by DIBAL in the same manner as described above, the primary hydroxyl group was protected with a Si-t-BuMe2 (TBS) group and the generated secondary alcohol was oxidized with DMP to produce ketone 18. Subsequent Wittig reaction proceeded to furnish internal olefins 19 and 20. The reaction proceeded smoothly (EtPPh3+Br–, n-BuLi, THF, 0–40 °C) to create the geometric isomer 19 (Z) and 20 (E) in 47% yield, respectively. To construct trisubstituted olefins on the C3 position, other reaction conditions are actually applied (changing reaction temperature, base, substrate). The details of the reaction conditions are shown in Scheme S2. Finally, the TBS groups of 19 (Z) and 20 (E) were removed with Bu4NF (TBAF) to synthesize the corresponding primary alcohol. The alcohol was further protected with PivCl to produce ester 14 (Z) and 15 (E) in 59% and 74% yield over two steps, respectively.

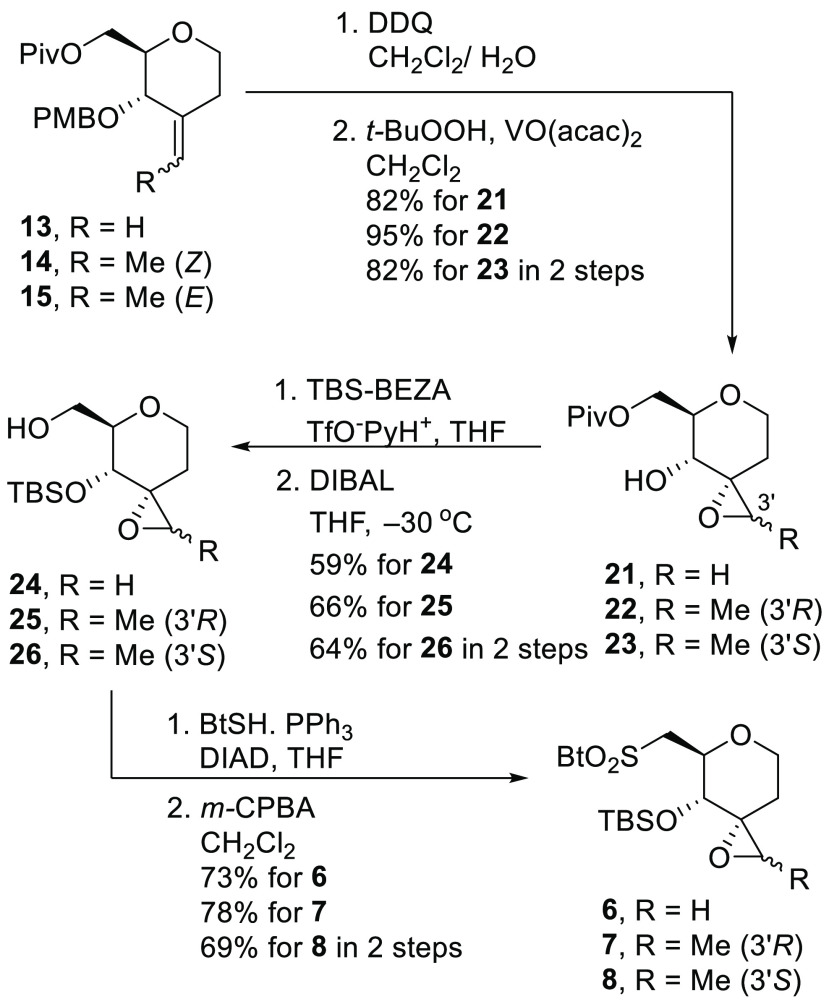

The synthesis of benzothiazoles 6–8 is summarized in Scheme 3. The p-methoxy benzyl groups of 13–15 were removed by 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-p-benzoquinone (DDQ) to produce the corresponding alcohol. Subsequent diastereoselective epoxidation of the double bond with catalytic vanadyl acetylacetonate (VO(acac)2) (10 mol %) and t-BuOOH afforded the corresponding epoxide 21–23 as a single diastereomer in 82%, 95%, and 82% yield over two steps, respectively. The relative configuration of 22 was determined by X-ray crystal structure analysis (See SI CIF file). Next, the secondary hydroxyl groups of 21–23 were protected as TBS-ether with O-(t-butyldimethylsilyl)benzanilide (TBS-BEZA) and TfO–PyH+. The pivalic ester was removed by DIBAL in THF at −30 °C to give the alcohols 24–26 in 59%, 66%, and 64% yield over two steps, respectively. Finally, the alcohols 24–26 were treated with 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (BtSH), PPh3, and diisopropyl azodicarboxylate (DIAD) to afford the benzothiazolyl sulfide, which was oxidized with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (m-CPBA) to generate the sulfones 6–8 in 73%, 78%, and 69% yield over two steps, respectively.

Scheme 3. Intermediates 6–8.

The sulfone 6 and aldehyde 12 were treated with LiN(SiMe3)2 (LHMDS) at −78 °C in THF (Julia–Kocienski olefination) to give the diene compound, which was treated with HCl/MeOH (0.05%) to give alcohol 27 in 63% yield over two steps (Scheme 4a).44 Next, to synthesize the coupling compounds 28 and 29, we initially tried the Julia–Kocienski olefination with sulfones 7, 8 and aldehyde 12, but the reaction was unsuccessful. The details of the reaction conditions are shown in Scheme S3. As shown in Scheme 4b, we tried another coupling combination. The oxidation of the primary alcohols 24 and 25 with DMP afforded the corresponding aldehydes 9 and 10, and treatment of the sulfone 11(21) and aldehydes 9 and 10 with LHMDS produced the corresponding coupling product in acceptable yield, which was treated with HCl/MeOH (0.05–0.1%) to give alcohols 28 and 29 in 39% and 59% yields over three steps, respectively.45 Acetylation of the alcohols 27–29 with Ac2O, triethyl amine (TEA), and N,N-dimethyl-4-amino pyridine (DMAP) gave the corresponding acetate, and after removal of the TBS group with TBAF it generated 3–5 in 72%, 82%, and 86% yields over two steps, respectively (Scheme 4c).

Scheme 4. (a) Synthesis for 27, (b) Synthesis for 28 and 29, and (c) 1,2-Deoxy-pyranose Derivative 3 and Its Epoxide Substituent Derivative 4 and 5.

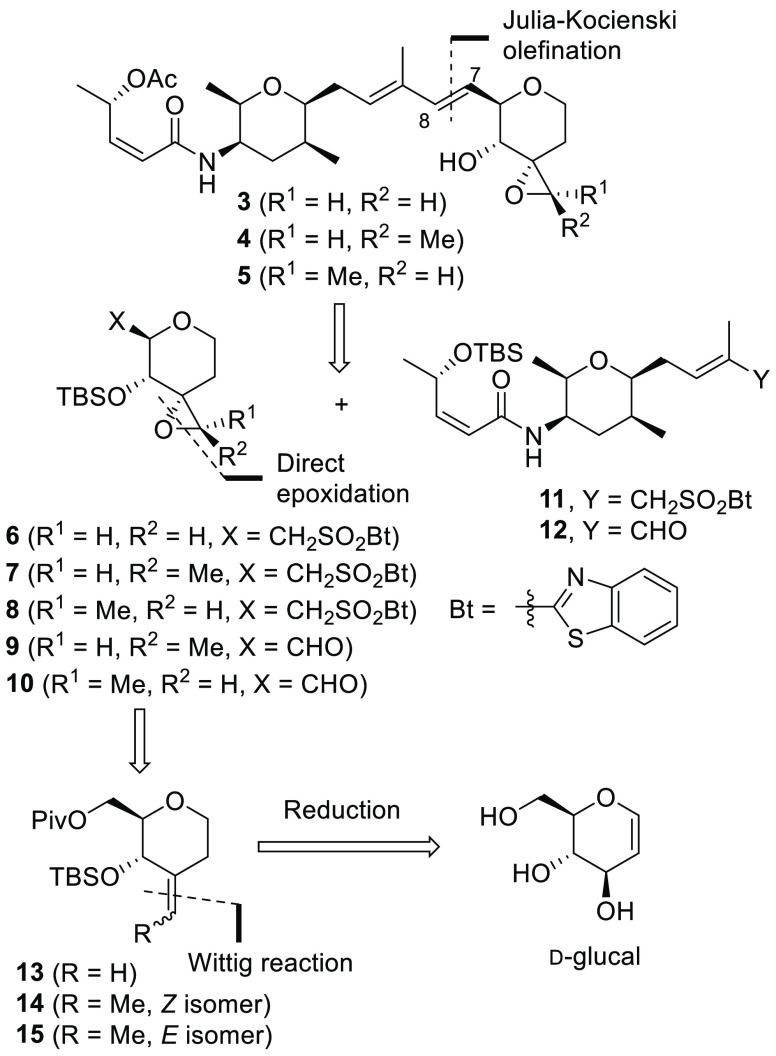

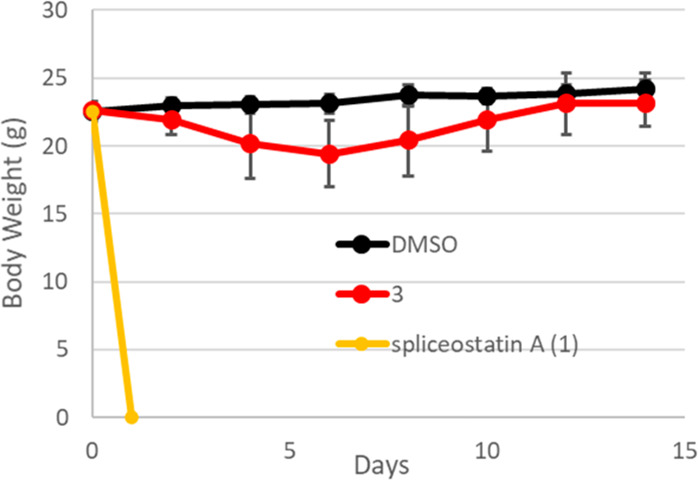

The biological activity study is presented in Table 1. Derivatives 3–5 suppressed AR-V7 splicing (IC50 = 3.3, 202, and 187 nM, respectively). The biological activity of 4 and 5 was almost identical to that of 2 (IC50 = 132 nM), but the activity of 3 was significantly improved over that of 2. The result of 3 suggested that the phenyl group at the C1 position could produce a steric hindrance within the SF3b complex and removing the phenyl group considerably improved the biological activity. The results of 4 and 5 suggested that the introduced methyl group on the epoxide might block the hydrogen bonding network around the epoxide and weaken the interaction with the SF3b complex. Since there were various amino acid residues that could interact with the epoxide of 4 or 5, the difference of stereochemistry (R and S) of the epoxy methyl did not affect the biological activity. With respect to the in vivo toxicity test, wild type mice administered 1 (280 nM/body, n = 6) showed severe toxicity (mice died within 24 h).

Table 1. AR-V7 Expression Inhibitory Activity Evaluation for 1 and 3–5.

| IC50 (nM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | spliceostatin A (1) | |

| AR-V7-GFP negative population | 3.3 | 202 | 187 | 0.6 |

However, none of the mice treated with 3 (280 nM/body, n = 7) died, and they did not show any significant weight loss compared to mice that were treated with DMSO alone (n = 8) (Figure 3).46−49

Figure 3.

In vivo toxicity evaluation of DMSO, 3 and spliceostatin A (1) for wild type mice (injected on day 0, 2, 4, 280 nmol/body, n = 6−8). Spliceostatin A killed all the treated mice (n = 6).

In conclusion, we designed, synthesized, and biologically evaluated the derivatives of spliceostatin A, 1,2-deoxy-pyranose derivative 3, and terminal epoxide methyl substituted derivatives (4, 5). The 1,2-deoxy-pyranose fragment and its terminal epoxide methyl substituted fragment were synthesized from commercially available d-glucal, and the synthetic steps for 24 were rather short.21 We also investigated Julia–Kocienski olefination for appropriate combinations. Furthermore, the IC50 values on suppression of AR-V7 for compounds 3–5 were weaker than that of 1; however, compound 3 exhibited potency (IC50) in the low nanomolar range. The in vivo toxicity test showed that wild type mice treated with 1 died within 24 h, but those mice treated with 3 did not die for 14 days and did not show weight loss. Therefore, we successfully created 3 with high AR-V7 expression inhibitory activity and low in vivo toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the JSPS KAKENHI for Precisely Designed Catalysts with Customized Scaffolding (Grant No. JP A16H010260 and 18H04260, and A262880510, T15K149760, and T15KT00630), by the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from the AMED under Grant Number JP19am0101084, by the Shorai Foundation for Science and Technology.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ADT

androgen deprivation therapy

- CRPC

castration-resistant prostate cancer

- AR

androgen receptor

- AR-V7

AR splicing variant 7

- DMP

Dess–Martin periodinane

- DIBAL

i-Bu2AlH

- PivCl

t-BuCOCl

- TBS

Si-t-BuMe2

- TBAF

Bu4NF

- VO(acac)2

vanadyl acetylacetonate

- TBS-BEZA

O-(t-butyldimethylsilyl)benzanilide

- BtSH

2-mercaptobenzothiazole

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- m-CPBA

m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid

- LHMDS

LiN(SiMe3)2

- TEA

triethyl amine

- DMAP

N,N-dimethyl-4-amino pyridine

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00153.

Author Contributions

∥ Y.Y. and A.I. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Beer T. M.; Armstrong A. J.; Rathkopf D. E.; Loriot Y.; Sternberg C. N.; Higano C. S.; Iversen P.; Bhattacharya S.; Carles J.; Chowdhury S.; Davis I. D.; de Bono J. S.; Evans C. P.; Fizazi K.; Joshua A. M.; Kim C. S.; Kimura G.; Mainwaring P.; Mansbach H.; Miller K.; Noonberg S. B.; Perabo F.; Phung D.; Saad F.; Scher H. I.; Taplin M. E.; Venner P. M.; Tombal B. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 424–433. 10.1056/NEJMoa1405095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. J.; Smith M. R.; de Bono J. S.; Molina A.; Logothetis C. J.; de Souza P.; Fizazi K.; Mainwaring P.; Piulats J. M.; Ng S.; Carles J.; Mulders P. F.; Basch E.; Small E. J.; Saad F.; Schrijvers D.; Van Poppel H.; Mukherjee S. D.; Suttmann H.; Gerritsen W. R.; Flaig T. W.; George D. J.; Yu E. Y.; Efstathiou E.; Pantuck A.; Winquist E.; Higano C. S.; Taplin M. E.; Park Y.; Kheoh T.; Griffin T.; Scher H. I.; Rathkopf D. E. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 138–148. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher H. I.; Fizazi K.; Saad F.; Taplin M. E.; Sternberg C. N.; Miller K.; de Wit R.; Mulders P.; Chi K. N.; Shore N. D.; Armstrong A. J.; Flaig T. W.; Flechon A.; Mainwaring P.; Fleming M.; Hainsworth J. D.; Hirmand M.; Selby B.; Seely L.; de Bono J. S. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1187–1197. 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis E. S.; Armstrong A. J.; Dehm S. M.; Luo J. Androgen receptor variant-driven prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016, 19, 231–241. 10.1038/pcan.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changxue L.; Jun L. Decoding the androgen receptor splice variants. Androl. Urol. 2013, 2, 178–186. 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2013.09.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Lo U. G.; Wu K.; Kapur P.; Liu X.; Huang J.; Chen W.; Hernandez E.; Santoyo J.; Ma S. H.; Pong R. C.; He D.; Cheng Y. Q.; Hsieh J. T. Developing new targeting strategy for androgen receptor variants in castration resistant prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2121–2130. 10.1002/ijc.30893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura N.; Nimura K.; Saga K.; Ishibashi A.; Kitamura K.; Nagano H.; Yoshikawa Y.; Ishida K.; Nonomura N.; Arisawa M.; Luo J.; Kaneda Y. SF3B2-mediated RNA splicing drives human prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 5204–5217. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y.; Ishibashi A.; Murai K.; Kaneda Y.; Nimura K.; Arisawa M. Design and synthesis of a phenyl C-glycoside derivative of spliceostatin A and its biological evaluation toward prostate cancer treatment. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 151313. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2019.151313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Zou J. X.; Xue X.; Cai D.; Zhang Y.; Duan Z.; Xiang Q.; Yang J. C.; Louie M. C.; Borowsky A. D.; Gao A. C.; Evans C. P.; Lam K. S.; Xu J.; Kung H. J.; Evans R. M.; Xu Y.; Chen H. W. ROR-γ drives androgen receptor expression and represents a therapeutic target in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 488–496. 10.1038/nm.4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wu X.; Xue X.; Li C.; Wang J.; Wang R.; Zhang C.; Wang C.; Shi Y.; Zou L.; Li Q.; Huang Z.; Hao X.; Loomes K.; Wu D.; Chen H.-W.; Xu J.; Xu Y. Potent and orally bioavailable inverse agonists of RORγt resulting from structure-based design. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 4716–4730. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H.; Sato B.; Fujita T.; Takase S.; Terano H.; Okuhara M. New antitumor substances, FR901463, FR901464 and FR901465. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J. Antibiot. 1996, 49, 1196–1203. 10.7164/antibiotics.49.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida D.; Motoyoshi H.; Tashiro E.; Nojima T.; Hagiwara M.; Ishigami K.; Watanabe H.; Kitahara T.; Yoshida T.; Nakajima H.; Tani T.; Horinouchi S.; Yoshida M. Spliceostatin A targets SF3b and inhibits both splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 576–583. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T.; Sameshima T.; Matsufuji M.; Kawamura N.; Dobashi K.; Mizui Y. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 173–179. 10.7164/antibiotics.57.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T.; Asai N.; Okuda A.; Kawamura N.; Mizui Y. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 180–187. 10.7164/antibiotics.57.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizui Y.; Sakai T.; Iwata M.; Uenaka T.; Okamoto K.; Shimizu H.; Yamori T.; Yoshimatsu K.; Asada M. Pladienolides, new substances from culture of streptomyces platensis Mer-11107. J. Antibiot. 2004, 57, 188–196. 10.7164/antibiotics.57.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake Y.; Sagane K.; Owa T.; Mimori-Kiyosue Y.; Shimizu H.; Uesugi M.; Ishihama Y.; Iwata M.; Mizui Y. Splicing factor SF3b as a target of the antitumor natural product pladienolide. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 570–575. 10.1038/nchembio.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y.; Yoshida T.; Ochiai K.; Uosaki Y.; Saitoh Y.; Tanaka F.; Akiyama T.; Akinaga S.; Mizukami T. Identification of SAP155 as the Target of GEX1A (Herboxidiene), an Antitumor Natural Product. J. Antibiot. 2002, 55, 855–862. 10.7164/antibiotics.55.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M.; Miura T.; Kuzuya K.; Inoue A.; Ki S. W.; Horinouchi S.; Yoshida T.; Kunoh T.; Koseki K.; Mino K.; Sasaki R.; Yoshida M.; Mizukami T. GEX1 compounds, novel antitumor antibiotics related to herboxidiene, produced by Streptomyces sp. I. Taxonomy, production, isolation, physicochemical properties and biological activities. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011, 6, 229–233. 10.1021/cb100248e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spliceostatin A, pladienolide B, and GEX1A have a common pharmacore (epoxide, acetyl, and diene groups, respectively), and some analogue synthesis of 1 using its pharmacore has been reported.Bonnal S.; Vigevani L.; Valcárcel J. The Spliceosome as a Target of Novel Antitumour Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 847–859. 10.1038/nrd3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. F.; Jamison T. F.; Jacobsen E. N. FR901464: Total Synthesis, Proof of Structure, and Evaluation of Synthetic Analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 9974–9983. 10.1021/ja016615t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyoshi H.; Horigome M.; Watanabe H.; Kitahara T. Total synthesis of FR901464: second generation. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 1378–1389. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.11.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Chen Z.-H. Enantioselective syntheses of FR901464 and spliceostatin A: potent inhibitors of spliceosome. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5088–5091. 10.1021/ol4024634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Chen Z.-H.; Effenberger K. A.; Jurica M. S. Enantioselective total syntheses of FR901464 and spliceostatin A and evaluation of splicing activity of key derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 5697–5709. 10.1021/jo500800k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman S.; Albert B. J.; Wang Y.; Li M.; Czaicki N. L.; Koide K. Structural requirements for the antiproliferative activity of pre-mRNA splicing inhibitor FR901464. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17, 895–904. 10.1002/chem.201002402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C.; Rhoades D.; Kumar S. M. Total syntheses of thailanstatins A–C, spliceostatin D, and analogues thereof. Stereodivergent synthesis of tetrasubstituted dihydro- and tetrahydropyrans and design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and discovery of potent antitumor agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8303–8320. 10.1021/jacs.8b04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Reddy G. C.; Kovela S.; Relitti N.; Urabe V. K.; Prichard B. E.; Jurica M. S. Enantioselective synthesis of a cyclopropane derivative of spliceostatin A and evaluation of bioactivity. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7293–7297. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanada R. M.; Itoh D.; Nagai M.; Niijima J.; Asai N.; Mizui Y.; Abe S.; Kotake Y. Total Synthesis of the Potent Antitumor Macrolides Pladienolide B and D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4350–4355. 10.1002/anie.200604997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Anderson D. D. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Pladienolide B: A Potent Spliceosome Inhibitor. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4730–4733. 10.1021/ol301886g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel A. L.; Jones B. D.; La Clair J. J.; Burkart M. D. A synthetic entry to pladienolide B and FD-895. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 5159–5164. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.06.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller S.; Mayer T.; Sasse F.; Maier M. E. Synthesis of a Pladienolide B Analogue with the Fully Functionalized Core Structure. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 3940–3943. 10.1021/ol201464m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundluru M. K.; Pourpak A.; Cui X.; Morris S. W.; Webb T. R. Design, Synthesis and Initial Biological Evaluation of a Novel Pladienolide Analog Scaffold. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 904–908. 10.1039/c1md00040c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V. P.; Chandrasekhar S. Enantioselective Synthesis of Pladienolide B and Truncated Analogues as New Anticancer Agents. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3610–3613. 10.1021/ol401458d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore P. R.; Kocienski P. J.; Morley A.; Muir K. A synthesis of herboxidiene. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1999, 955–968. 10.1039/a900185i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray T. J.; Forsyth C. J. Total Synthesis of GEX1A. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 3429–3431. 10.1021/ol800902g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A. K.; Li J. A Stereoselective Synthesis of (+)-Herboxidiene/GEX1A. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 66–69. 10.1021/ol102549a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirupathi B.; Mohapatra D. K. Gold-Catalyzed Hosomi-Sakurai Type Reaction for the Total Synthesis of Herboxidiene. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 6212–6224. 10.1039/C6OB00321D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds A. J. F.; Arnold G.; Hagmann L.; Schaffner R.; Furlenmeier H. Synthesis of SimpliÆed Herboxidiene Aromatic Hybrids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000, 10, 1365–1368. 10.1016/S0960-894X(00)00230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskens F. A. L. M.; Ramos F. J.; Burger H.; O’Brien J. P.; Piera A.; de Jonge M. J. A.; Mizui Y.; Wiemer E. A. C.; Carreras M. J.; Baselga J.; Tabernero J. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the first-in-class spliceosome inhibitor E7107 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6296–6304. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong D. S.; Kurzrock R.; Naing A.; Wheler J. J.; Falchook G. S.; Schiffman J. S.; Faulkner N.; Pilat M. J.; O’Brien J.; LoRusso P. A phase I, open-label, single-arm, dose-escalation study of E7107, a precursor messenger ribonucleic acid (pre-mRNA) splicesome inhibitor administered intravenously on days 1 and 8 every 21 days to patients with solid tumors. Invest. New Drugs 2014, 32, 436–444. 10.1007/s10637-013-0046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Because AR-V7 expression inhibitory activity of GEX1A has not been reported, we did not focus on it.

- In this research, we did not know the target protein which related to AR-V7 expression inhibitory activity.

- By the introduction of an alkyl group on the epoxide, the chemical reactivity is reduced. Thus, the reactivity of 3 and 4 with biological substances related to the onset of toxicity (DNA, etc.) could decrease.Gonzalez-Perez M.; Gomez-Bombarelli R.; Arenas-Valganon J.; Perez-Prior M. T.; Garcia-Santos M. P.; Calle E.; Casado J. Connecting the chemical and biological reactivity of epoxides. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 2755–2762. 10.1021/tx300389z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catino A. J.; Sherlock A.; Shieh P.; Wzorek J. S.; Evans D. A. Approach to the tricyclic core of the tigliane–daphnane diterpenes. Concerning the utility of transannular aldol additions. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 3330–3333. 10.1021/ol401367h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methods for selective removal of the TBS group on allyl alcohol have been reported (ref (21)).

- Differences of chemical yields (39% for 28 and 59% for 29) stem from Julia–Kocienski olefination.

- One reason for the toxicity of 1 could be due to an unsaturated ketone or a furan ring formed by cleavage of a ketal at the C1 position of 1.

- Albert B. J.; Sivaramakrishnan A.; Naka T.; Czaicki N. L.; Koide K. Total Syntheses, Fragmentation Studies, and Antitumor/Antiproliferative Activities of FR901464 and Its Low Picomolar Analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2648–2659. 10.1021/ja067870m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleva Y. K.; Madden J. C.; Cronin M. T. D. Formation of Categories from Structure-Activity Relationships to Allow ReadAcross for Risk Assessment: Toxicity of α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 2300–2312. 10.1021/tx8002438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- As a result of dissection of the dead mouse, intestinal bleeding was observed in all mice.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.