Abstract

Plasmid DNA (pDNA) vaccines are effective at eliciting immune responses in a wide variety of animal model systems, however, pDNA vaccines have generally been incapable of inducing robust immune responses in clinical trials. Therefore, to identify means to improve pDNA vaccine performance, we compared various post-transcriptional and post-translational genetic modifications for their ability to improve antigen-specific CMI responses. Mice vaccinated using a sub-optimal 100 mcg dose of a pDNA encoding an unmodified primary isolate HIV-16101 env gp160 failed to demonstrate measurable env-specific CMI responses. In contrast, significant env-specific CMI responses were seen in mice immunized with pDNA expression vectors encoding env genes modified by RNA optimization or codon optimization. Further modification of the RNA optimized env gp160 gene by the addition of (i) a simian retrovirus type 1 constitutive RNA transport element; (ii) a murine intracisternal A-particle derived RNA transport element; (iii) a tissue plasminogen activator protein signal leader sequences; (iv) a beta-catenin derived ubiquitination target sequence; or (v) a monocyte chemotactic protein-3 derived signal sequence failed to further improve the induction of env-specific CMI responses. Therefore, modification of the env gp160 gene by RNA or codon optimization alone is necessary for high-level rev-independent expression and results in robust env-specific CMI responses in immunized mice. Importantly, further modification(s) of the env gene to alter cellular localization or increase proteolytic processing failed to result in increased env-specific immune responses. These results have important implications for the design and development of an efficacious vaccine for the prevention of HIV-1 infection.

Keywords: Plasmid DNA vaccine, Cell-mediated immunity, HIV-1, Mice

1. Introduction

According to the latest figures published in the UNAIDS/WHO 2006 AIDS Epidemic Update, an estimated 39.5 million people are living with HIV. There were 4.3 million new infections in 2006 with 2.8 million of these occurring in sub-Saharan Africa. Of particular concern are the increases in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where there are some indications that infection rates have risen by more than 50% since 2004 [1]. In 2006 alone, 2.9 million people died of AIDS-related illnesses. In many developed countries, the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV-1 infection has declined substantially due to the widespread availability and use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). However, the rate of new HIV infections has not declined substantially despite prevention programs and HAART availability. In developing countries, where HAART is largely unavailable, social programs intended to reduce the spread of HIV have generally proven insufficient and the epidemic continues. A safe and effective vaccine for the prevention of HIV infection is urgently needed to slow the epidemic, particularly in developing countries without widespread access to HAART.

In 1990, it was first demonstrated that the direct injection of naked plasmid DNA (pDNA) encoding a foreign antigen into mouse myocytes resulted in uptake of the pDNA by host cells and subsequent expression of the foreign antigen [2]. Shortly thereafter, animal studies clearly demonstrated that pDNA vaccines were capable of eliciting humoral [3] and cellular immune responses [4,5] against the encoded vaccine antigen. Following these pioneering studies, pDNA vaccines have proven to be effective at eliciting HIV antigen-specific immune responses in a wide variety of animal model systems [6–8] and have been evaluated in a number of Phase I clinical trials [9–34] where they have been found to be well tolerated.

However, despite promising results in pre-clinical immunogenicity studies, pDNA vaccines have generally been incapable of inducing robust antigen-specific immune responses in clinical trials. One possible explanation for this may be reduced stimulatory effect of CpG sequences in the plasmid backbone due to the low expression levels of TLR9 in humans [35]. Another possible explanation for the poor performance of pDNA vaccines in humans is that the level of protein expression may be insufficient to elicit strong immune responses. Indeed, even in mice, it has been suggested that the amount of protein expressed following pDNA vaccination limits the immune response.

In the case of HIV infection, it is clear that the HIV-specific cell-mediated immune (CMI) response plays a key role in the early control of HIV replication during primary infection [36,37]. In addition, there exists a clear correlation between pre-challenge vaccine-elicited CMI responses and post-challenge outcome in simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV)/rhesus macaque challenge experiments [38,39]. Collectively, these observations suggest that means to improve pDNA vaccine performance are urgently needed to speed the development of an effective vaccine for the prevention of HIV infection.

A number of methods have therefore been developed to improve the in vivo performance of candidate pDNA vaccines which include co-delivery of plasmid-based cytokines and chemokines (reviewed in [40,41]), improved pDNA delivery technologies (e.g. gene gun, in vivo electroporation, etc.), and the use of pDNA vaccines in heterologous prime-boost vaccination regimens [39,42–44].

Efforts to improve the performance of the pDNA vectors themselves has been focused in a number of areas. For example, in vivo pDNA vaccine performance could potentially be improved by a wide range of techniques including RNA optimization [45–47], codon optimization [48,49], by improving mRNA stability and transport [50–52] and through the use of improved promoter/enhancer/regulator elements [53]; all of which seek to boost expression levels of the encoded vaccine antigen and the resulting vaccine antigen-specific immune response in vivo.

Another potential means of improving in vivo pDNA performance is the manipulation or alteration of the intracellular localization of the encoded vaccine antigen. It has been hypothesized that targeting a vaccine antigen for extracellular secretion or membrane localization may enhance cross-priming [54,55]. Others have sought to target vaccine antigens to the endosome/lysosome pathway to facilitate loading of immunogenic peptide epitopes onto the cell surface in association with class II MHC [56–61], while others have sought to target the encoded vaccine antigen directly into the MHC class I antigen processing pathway in an effort to enhance the loading of immunogenic peptide epitopes onto the cell surface in association with MHC class I and improve the induction of CTL responses [62–68]. Finally, various means of increasing the local infiltration and activation of professional antigen presenting cells to the site of pDNA inoculation including the use of cytokines and chemokines (reviewed in [40,41]), have been evaluated for their ability to improve vaccine performance in a wide range of animal models.

In the current study, we sought to determine the extent to which RNA or codon optimization alone, or in the context of additional post-transcriptional and post-translational genetic modifications could improve pDNA gene expression in vitro and enhance the induction of pDNA vaccine-specific cell-mediated and humoral immune responses in vivo. We find that genetic alteration of the HIV-16101 env gp160 gene by RNA or codon optimization alone was necessary for high-level rev-independent expression in vitro and resulted in the induction of robust env-specific serum antibody and CMI responses in immunized mice. However, additional post-transcriptional and/or post-translational genetic modification(s) of the env gene failed to improve the magnitude, breadth, or protective capacity of the env-specific immune response.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plasmid DNAs

Clade B primary isolate HIV-16101 env gp160 genes (from David Montefiori, gene bank accession no. bankit625244) which were unmodified, RNA optimized, or codon optimized using less preferred codons were used for study. Codon optimization refers to the process by which all wild-type codons are replaced by codons used in highly expressed human genes [48,49] whereas codon optimization using “less preferred” codons refers to the process by which only select wild-type codons are replaced with codons of medium preference [69]. RNA optimization involved the introduction of multiple silent point mutations within the coding region inactivating endogenous inhibitory sequences thus allowing for high-level rev-independent expression as previously described [45–47].

The secreted variant of HIV-16101 env gp160 was generated by fusion with the signal peptide (amino acids [aa] 1–36) from the tissue type plasminogen activator (spTPA) protein at the N terminus of env replacing the endogenous signal peptide. The intracellularly degraded variant of HIV-16101 env gp160 was generated by fusion with beta-catenin (CATE)-derived peptide (aa 18–47) [70] at the N terminus of env replacing the signal peptide [71]. The IP10 MCP3 env fusion construct contains a 20 aa signal peptide sequence from the IP10 gene (interferon inducible protein) followed by a 77 aa mature peptide of MCP3 gene at the N terminus of env replacing its endogenous sequence [72]. The IP10 signal peptide and the MCP3 mature peptide are separated by a 4 aa linker sequence. To enhance the cytoplasmic transport of env mRNA, a 173 nucleotide sequence specific to Simian retrovirus type-1 cytoplasmic transport element (SRV-1 CTE [51,52,73,74]) and a 226 nucleotide sequence specific to a mammalian RNA transport element (RTE [52]) were placed at the 3′ prime end of the env gene after the stop codon and before the polyadenylation signal.

Various plasmid DNA-based expression vectors (Table 1) were combined with a plasmid encoding murine IL-12 and used as the experimental vaccine. Expression cassettes encoding HIV-16101 derived env gp160 genes were constructed using one of the following four transcriptional unit designs: (i) human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) immediate early promoter and bovine growth hormone (BGH) polyadenylation (polyA) signal; (ii) simian cytomegalovirus (SCMV) promoter and BGH polyA signal; (iii) murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) promoter and BGH polyA; (iv) Herpes simplex virus Lapl (HSV Lapl) promoter, SV40 splice donor/acceptor and BGH polyA signal. In addition, expression vectors included a chimeric kanamycin resistance (kmr) gene, adenylyl-4′-nucleotidyl transferase type 1 a [75,76] and a ColE1 bacterial origin of replication required for selection and propagation of bacteria, respectively.

Table 1.

Plasmid DNA expression vectors used

| Vector ID | Promoter | Form of the HIV-16101 env protein expressed | mRNA modifications |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNA optimization | Additional RNA modifications | |||

| WLV-001 | N/A | None | N/A | N/A |

| WLV-119 | HCMV IEa | gp160 | None | None |

| WLV-211 | HSV-2 Lap1b | gp160 | Yes | None |

| WLV-210 | MCMV | gp160 | Yes | None |

| WLV-196 | SCMV | gp160 | Yes | None |

| WLV-106 | HCMV IE | gp160 | Yes | None |

| WLV-118 | HCMV IE | gp160 | No, alt app.c | None |

| WLV-107 | HCMV IE | gp160 | Yes | SRV-1 CTEd |

| WLV-108 | HCMV IE | gp160 | Yes | RTEe |

| WLV-109 | HCMV IE | spTPAf–gp160 fusion | Yes | None |

| WLV-110 | HCMV IE | β-CATg–gp160 fusion | Yes | None |

| WLV-111 | HCMV IE | MCP3h–gp160 fusion | Yes | None |

| WLV-112 | HCMV IE | spTPA–gp160 fusion | Yes | SRV-1 CTE |

| WLV-113 | HCMV IE | β-CAT–gp160 fusion | Yes | SRV-1 CTE |

| WLV-114 | HCMV IE | MCP3–gp160 fusion | Yes | SRV-1 CTE |

| WLV-115 | HCMV IE | spTPA–gp160 fusion | Yes | RTE |

| WLV-116 | HCMV IE | β-CAT–gp160 fusion | Yes | RTE |

| WLV-117 | HCMV IE | MCP3–gp160 fusion | Yes | RTE |

HCMV IE; human cytomegalovirus virus immediate early promoter.

HSV Lap1; herpes simplex virus type-2 latency associated promoter.

Codon optimized by an alternative approach.

SRV-1 CTE; simian retrovirus type-1 constitutive transport element.

RTE; RNA transport element.

Signal-leader sequence derived from tissue-type plasminogen activator protein.

Beta-catenin.

Monocyte chemotactic protein-3.

The dual-promoter IL-12 expression vector used as a vaccine adjuvant encodes the murine IL-12 p35 and p40 genes. The IL-12 p35 subunit is expressed under control of the HCMV immediate early promoter and SV40 polyA signal, while the IL-12 p40 subunit is expressed under control of the SCMV and BGH polyA signal. Production of murine IL-12 was confirmed after transient transfection of RD cells and screening the cell supernatants for cytokine expression using an anti-mouse IL-12 p70 capture ELISA (data not shown; Endogen, Woburn, MA). Bioactivity of the plasmid-expressed murine IL-12 was confirmed by assaying supernatants from transiently transfected RD cells for the capacity to induce IFN-γ secretion in resting rhesus peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs; data not shown).

Expression plasmids for inoculation of mice were produced by Puresyn, Inc. (Malvern, PA). Plasmids were propagated in E. coli, isolated from cells by alkaline lysis, purified by column chromatography and formulated individually at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL in isotonic citrate buffer (29.3 mM sodium citrate, 0.67 mM citric acid, 150 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM EDTA, pH 6.4–6.7) containing 0.25% bupivacaine to allow for the formation of DNA:bupivacaine complexes [77]. Final plasmid preparations were shown to consist of >90% supercoiled plasmid DNA and residual endotoxin was shown to be <30 EU/mg DNA (data not shown).

2.2. In vitro HIV gene expression by Western blot

For each plasmid DNA expression vector, in vitro expression of the encoded HIV-16101 env gp160 gene was confirmed by Western blot after transient transfection of 293 T cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Briefly, 293 T cells were plated 24 h prior to transfection at a density of 2 × 105 cells per 35 mm diameter well in 2 mL Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). Prior to transfection, 100 mcL of serum free DMEM was combined with 6 mcL of Fugene 6 transfection agent (Roche). This mix was slowly added to an eppendorf tube containing 1 mcg ofSEAP DNA (control DNA) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. This mixture was then added to an eppendorf tube containing 2 mcg of test or control DNA and allowed to stand at room temperature for another 15 min. The whole mixture was then directly added to the well containing 293 T cells. Forty-eight hours later, transfected cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) and lysed in 200 mcL of Triton-X lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor (Complete-1 tablet/10 mL of lysis buffer, Roche). After cell lysis, cell-associated proteins were collected in an eppendorf tube and kept on ice for 20 min. Proteins were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min to remove cell debris and the supernatant was transferred to a clean eppendorf tube. Cell lysates were stored at −70 °C until tested.

Western blot analysis of env expression was performed as follows: first, total protein in cell lysates was determined by the BCA method (Pierce; Rockford, IL). A total of 20 mcg of reduced and denatured total protein was loaded onto 4–12% Bis/Tris, SOS PAGE gradient gels as per manufacturer’s instructions (lnvitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). SDS PAGE gels were run at 90 V for 2 h after which protein was transferred to PVDF membranes (lnvitrogen). Prestained markers and recombinant HIV-1 env gp160 protein (Immunodiagnostics; Woburn, MA) were used as size standards and positive controls, respectively. For detection of env expression by immunostaining, membranes were incubated with a polyclonal rabbit anti-HIV-env (Cat# 13–204-000, Advanced Biotechnologies Inc.). Antibodies were used at a concentration of 0.5 mcg/mL in a total volume of 10 mL per blot. Secondary antibodies conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (lnvitrogen) were used and detection was performed by using the Western Breeze chromogenic detection kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (lnvitrogen).

2.3. In vitro HIV gene expression by ELISA

HIV-16101 env gp160 protein expression was quantified by ELISA using the HIV-1 gp120 Antigen Capture Assay kit (Cat# 5429 Advanced Bioscience Labs) as per the manufacture’s instructions.

2.4. DNA immunization of mice

For these studies, 4–6 week old female Balb/c mice were used. Mice were maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, National Academic Press, Washington, DC, 1996). In addition, procedures for the use and care of the mice were approved by Wyeth Research’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Immediately prior to inoculation, the indicated HIV plasmid expression vectors were mixed, combined with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12 and administered by intramuscular injection into both quadriceps muscles (0.1 mL total injection volume, 0.05 mL per site) using an 18 gauge needle and 0.3 mL syringe.

2.5. IFN-γ ELISpot assay

Ten days after the final DNA inoculation, mice were sacrificed and spleen cells were harvested. For the determination of vaccine-elicited lFN-γ ELISpot responses a mouse lFN-γ ELISpot kit (material number 551083, BD Biosciences, San Diego CA) was used. Ninety-six-well flat-bottom ELISpot plates (ImmunoSpot, Cellular Technology Limited, Cleveland OH) were coated overnight with a purified anti-mouse γ-interferon (mIFN-γ) monoclonal antibody (Material No. 51–2525KC, BD-Biosciences, San Diego CA) at a concentration of 10 mcg/mL, after which the plates were washed three times with sterile1 × phosphate buffered saline (1 × PBS) and then blocked for 2 h with R10 complete culture medium (RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mcg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mM HEPES, 100 mcM non-essential amino acids). Mouse spleens were homogenized by grinding the spleens between the frosted ends of two sterile microscope slides. The resulting homogenate was suspended in 10 mL of complete ROS culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 mcg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mM HEPES, 100 mcM non-essential amino acids) and splenocytes were subsequently isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation and resuspended in complete R10 culture medium containing either 2 mcg/mL Con-A (Sigma), peptide pools (15 mers overlapping by 11 amino acids; 2.5 mcM each final peptide concentration) spanning HIV-16101 env gp160 or medium alone. Input cell numbers were 4 × 105 splenocytes/well (4 × 106 splenocytes/mL) and assayed in duplicate wells. Splenocytes were incubated for 22–24 h at 37 °C and then removed from the ELISpot plate by first washing three times with deionized water and incubating on ice for 10–20 min. Then plates were washed six times with 1 × PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20. Thereafter, plates were treated with an anti-mouse IFN-γ biotinylated detection antibody (5.0 mcg/mL, Material No. 51–1818KZ, BD-Biosciences, San Diego CA) diluted with R10 and incubated overnight at 4 °C ELISpot plates were then washed 10 times with 1 × PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and treated with 100 mcL/well of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Catalog No. 51–9000209, BD-Biosciences, San Diego, CA) diluted 1 :100 with R10 and incubated an additional 1 h at room temperature. Unbound conjugate was removed by rinsing the plate six times with 1 × PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 3 times with 1 × PBS. Finally, diluted (20 mcL/mL) AEC Chromogen in AEC substrate solution (Catalog No. 551951, BD-Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was then added (100 mcL/well) for 3–5 min before being rinsed away with water, after which the plates were air-dried, and the resulting spots counted using an Immunospot Reader (CTL Inc., Cleveland, OH). Peptide-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses were considered positive if the response (minus media background) was ≥3-fold above the media response and ≥50 SFC/106 splenocytes.

2.6. Antigen-specific antibody titers by sandwich ELISA

For the determination of HIV-16101 env gp120-specific antibody titers, immulon II HB plates were coated for 18 h at 4 °C with polyclonal sheep anti-HIV gp120 (500 ng/mL, Cliniqa, Fallbrook, CA) diluted in 1 × PBS buffer. The plates were washed five times with 1 × PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (1 × PBST) and blocked for 1 h at room temperature (RT) with 1 × PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 3% BSA (3% BSA/PBST). The blocking buffer was removed and the plates were incubated with purified HIV-16101 env gp120 (20 ng/well) diluted in 1% BSA/PBST. The plates were then washed five times with 1 × PBST. Serum samples, diluted with 1% BSA/PBST were added to the ELISA plates at a starting dilution of 1 :50, and further diluted 3-fold down the plates. Plates were kept at 4 °C overnight after which time they were washed five times with 1 × PBST, a biotin conjugated primary antibody specific for mouse lgG (diluted 1:20,000 with 1%BSA/PBST,Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) was then added (100 mcL/well) for 1 h at RT. followed by 1 h at RT with 100 mcL/well of a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-biotin antibody (500 units/mL stock, diluted 1 :10,000 with 1% BSA/PBST, Roche Immunochemical, Indianapolis, IN). Finally, ELISA plates were developed by the addition of 100 mcL/well of TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethyl benzidine, Sigma). Antigen-specific antibody titers were defined as the reciprocal of the last serum dilution giving an O.D.450 greater than the average O.D. of serum from the control group + 3 standard deviations.

2. 7. Vaccinia virus titer in the ovaries of challenged mice

Ten days after the final DNA vaccination, the mice (n = 10/group) were challenged i.p. with 107 plaque forming units of a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HIV-16101 env gp120 (rVV-env, gift of Dr. L Liao, Duke University). Five days after the rVV-env challenge, the mice were sacrificed and their ovaries were removed, homogenized, sonicated, and assayed for rVV-env by plating serial 10-fold dilutions on BSC-1 indicator cells. After 2 days of culture, the medium was removed; the BSC-1 cell monolayer was stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Sigma) for 5 min, and then dried. The plaques per well were counted visually.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Comparisons of antigen-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses, env-specific serum lgG and rVV-env titers in the different vaccination groups were performed using negative binomial regression. The negative binomial regression analyses were performed using the SAS Procedure GENMOD in SAS version 8.2 (Cary, NC). In all cases, p-values less than 0.05 indicated that the tests were statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Codon or RNA optimization is critical for high-level protein expression in vitro and immunogenicity in vivo

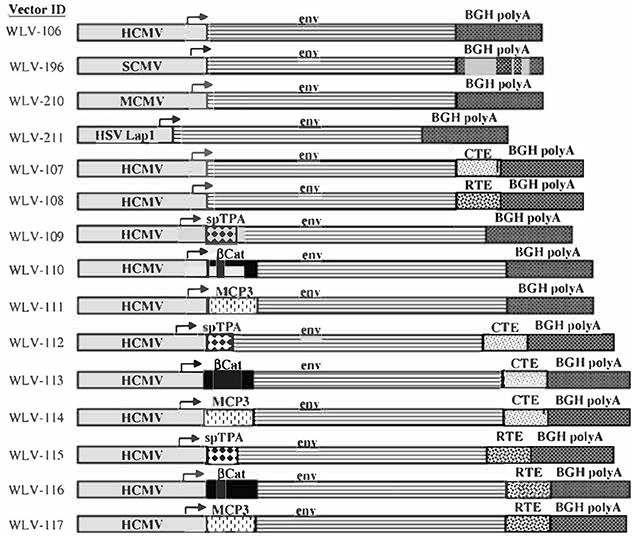

In this study, we sought to evaluate various coding and non-coding genetic modifications for their ability to improve plasmid DNA (pDNA) vaccine performance. Table 1 outlines the HIV-16101 env gp160 gene expression plasmids which were constructed for this analysis. The non-coding genetic modifications evaluated for their ability to improve pDNA vector performance included the use of codon optimization or RNA optimization alone or in combination with RNA transport elements derived from either simian retrovirus type-1 (SRV-1 CTE) or a murine intracisternal A-particles (RTE). In addition, coding modifications included expression of the env gp160 protein as a fusion with other biologically active protein sequences to alter protein localization, protein degradation, or to improve the recruitment of professional antigen presenting cells with the goal of improving env-specific cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses in vivo. To alter the subcellular localization of the expressed env gp160 protein and increase extracellular secretion of the expressed protein, the signal leader peptide derived from tissue type plasminogen activator protein (spTPA) was used. To increase intracellular degradation and potentially increase peptide loading on to MHC Class I, an env gp160 fusion protein with a ubiquination signal derived from beta-catenin (β-CAT) was generated [70,71]. To potentially improve antigen presentation through the increased recruitment of professional APCs, an env gp160 fusion was generated using the chemokine monocyte chemotactic protein-3 (MCP3) [72]. A schematic diagram showing the organization of the various HIV-16101 env gp160 expressing constructs is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the modified HIV-16101 env gp160 genes used in these studies. The following elements present in these constructs are not represented to scale. HCMV: human cytomegalovirus promoter/enhancer; SCMV: simian cytomegalovirus promoter/enhancer; MCMV: murine cytomegalovirus promoter/enhancer: HSV Lapl: herpes simplex virus type-2 latency associated promoter 1; env: HIV-1 envelope (gp160) gene from the clade B primary isolate 6101; BGH polyA: bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal; CTE: simian retrovirus type-1 cytoplasmic transport element; RTE: RNA transport element; spTPA: signal peptide derived from tissue type plasminogen activater protein; β-CAT: beta-catenin; MCP3: monocyte chemotactic protein.

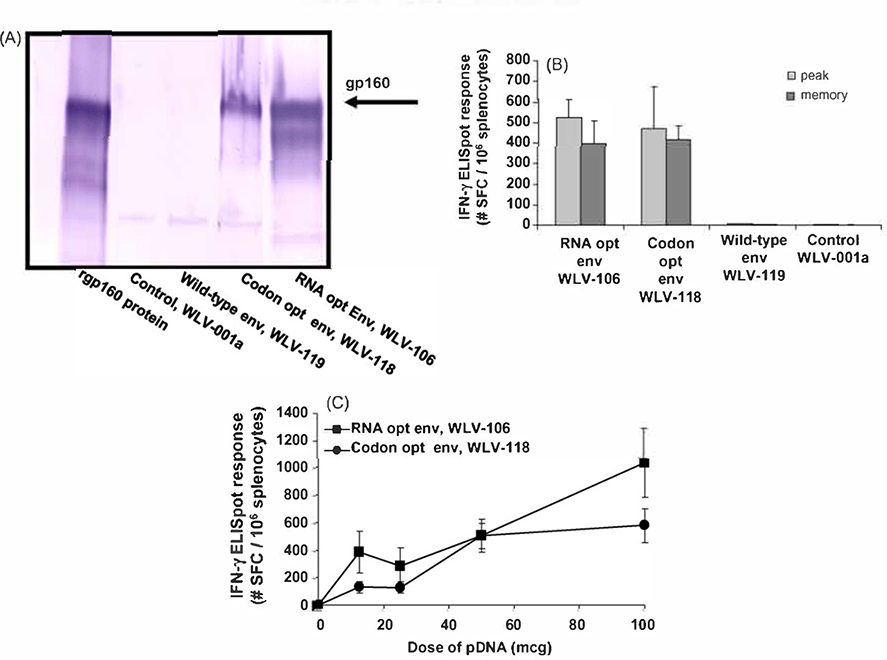

The plasmid expression vectors encoding the unmodified (WLV-119), RNA (WLV-106) and codon optimized (WLV-118) HIV-16101 env gp160 genes were first screened for their ability to express the encoded antigen by in vitro western blot analysis (Fig. 2). Transient transfection of 293 T cells in vitro with either the control expression vector WLV-001 a or the expression vector WLV-119 encoding the wild-type HIV-16101 env gp160 gene failed to result in detectable env expression in cell lysates by Western blot (Fig. 2A). In contrast, robust HIV-16101 env gp160 expression was seen in vitro after transfection with the pDNA vectors encoding the codon (WLV-118) or the RNA optimized (WLV-106) gene inserts.

Fig. 2.

Relative in vitro protein expression and in vivo immunogenicity of pDNA vectors encoding wild-type, RNA or codon optimized HIV-16101 env gp160. (A) HIV-16101 env protein expression by Western blot. 293 T cells were transfected with 2 mcg of the indicated plasmid DNA expression vector (see Table 1). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell supernatants were subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and proteins were visualized by Western blot using a polyclonal anti-HIV env gp160 antibody. (B and C) HIV-16101 env gp160-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses after pDNA immunization. Groups of mice (n = 6) were immunized i.m. with the indicated pDNA expression vectors (100 mcg total vaccine dose in (B) in combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12. Peak (10 days post-single immunization) and memory (6 weeks post-prime-boost on a schedule of O and 3 weeks) HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific cell-mediated immune responses were quantitated in splenocytes by lFN-γ ELISpot assay. Data are presented as the average response with the standard error of the mean indicated.

To monitor the ability of these pDNA expression vectors to elicit HIV-16101 env gp160-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses in vivo, groups of Balb/c mice (n = 6) were immunized i.m. with the indicated pDNA expression vectors (100 mcg total vaccine dose) in combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12. Peak (10 days post-single immunization) and memory (6 weeks post-prime-boost on a schedule of 0 and 3 weeks) HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific CMI responses were quantitated in splenocytes by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Consistent with the pattern of in vitro protein expression (Fig. 2A), mice immunized with the control expression vector WLV-001a or the expression vector WLV-119 encoding the wild-type HIV-16101 env gp160 gene failed to demonstrate measurable peak or memory env-specific CMI responses (Fig. 2B). In contrast, robust env-specific CMl responses were seen following immunization with the pDNA vectors encoding the codon (WLV-118) or the RNA optimized (WLV-106) gene inserts (Fig. 2B).

In an effort to differentiate amongst the pDNA vectors encoding the codon (WLV-118) or the RNA optimized (WLV-106) gene inserts with regards to their ability to elicit in vivo env-specific CMI responses, Balb/c mice were immunized with a dose range (12.5, 25, 50 and 100 mcg) of the expression vectors in combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12. Ten days after a single pDNA inoculation, splenocytes from the immunized mice were harvested and screened for the induction of env-specific CMl responses by lFN-γ ELISpot assay (Fig. 2C). The results indicate that the pDNA vector encoding the RNA optimized (WLV-106) gene insert tended to elicit increased env-specific CMI responses in vivo relative to the expression vector encoding the codon optimized (WLV-118) gene insert, though these differences did not achieve statistical significance. Taken together, the in vitro protein expression data and the in vivo immunogenicity data suggest that some form of codon or RNA optimization is essential in increasing HIV-16101 env gp160 gene expression in vitro and immunogenicity in vivo.

3.2. Effect of promoter elements on in vitro protein expression and in vivo immunogenicity

In an effort to identify the ideal promoter sequences to utilize in candidate vaccine constructs to drive the expression of the optimized and/or modified HIV-1 env genes, we sought to compare the relative in vitro and in vivo performance of pDNA vaccines containing various promoter elements. To this end, plasmid DNA expression vectors were constructed utilizing the HCMV derived immediate-early promoter (WLV-106), a SCMV derived promoter (WLV-196), a MCMV derived promoter (WLV-210), or a Herpes simplex virus type 2 latency associated promoter (WLV-211). each driving the expression of an RNA optimized primary isolate HIV-16101 env gp160 gene terminated by a bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal.

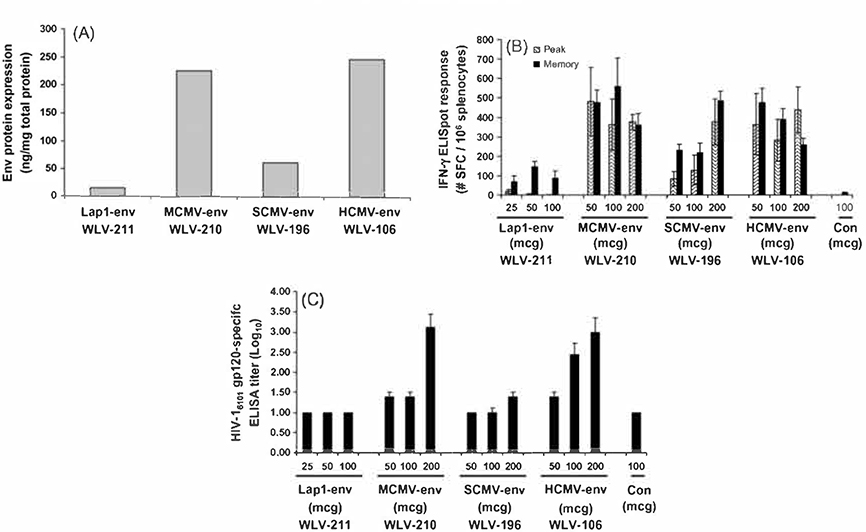

We first measured the relative in vitro expression of the HIV-16101 env gp160 protein from these various pDNA expression vectors using a quantitative ELISA assay following transient transfection of 293 T cells. Results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 3A. It was consistently found that the HCMV and MCMV derived promoters resulted in the highest in vitro expression levels, while noticeably lower levels of env protein expression were seen following transfection with the construct containing the SCMV derived promoter. Finally, virtually no env protein expression was seen following transient transfection of 293 T cells with the expression vector containing the HSV Lap 1 derived promoter element.

Fig. 3.

Relative in vitro expression levels and in vivo immunogenicity of pDNA vectors directing the expression of a RNA optimized HIV-16101 env gp160 gene under the control of various promoter elements. (A) HIV-16101 env protein expression by quantitative ELISA. 293 T cells were transfected with 2 mcg of the indicated plasmid DNA expression vector (see Table 1). Forty-eight hours after transfection, HIV-16101 env gp16O protein was quantitated in cell supernatants by quantitative ELISA using a polyclonal anti-HIV env gp16O antibody. (B) HIV-16101 env gp16O-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses after pDNA immunization. Groups of mice (n = 6) were immunized i.m. with increasing doses of the indicated pDNA expression vectors in combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12. Peak (10 days post-single immunization) and memory (6 weeks post-prime-boost on a schedule of 0 and 3 weeks) HIV-16101 env gp16O peptide pool-specific cell-mediated immune responses were quantitated in splenocytes by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Data are presented as the average response with the standard error of the mean indicated. (C) HIV-16101 env gp12O-specific serum antibody responses after pDNA immunization. Groups of mice (n = 6) were immunized i.m. with increasing doses of the indicated pDNA expression vectors In combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12 on a schedule of 0 and 3 weeks. Six weeks after the final immunization, the titer of serum antibody binding HIV-16101 gp12O was quantitated by ELISA. Data are presented as the mean log10 response with the standard error of the mean indicated.

Next we measured the relative immunogenicity of the various pDNA expression vectors encoding the various promoter elements by HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific IFN-γ ELISpot assay (Fig. 3B) and HIV-16101 env gp120 ELISA (Fig. 3C). For this experiment, Balb/c mice (n = 6 per group) were immunized with increasing amounts of the indicated expression vectors in combination with 25 mcg plasmid-based murine IL-12. Peak and memory HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses were then quantitated either 10 days after a single immunization or 6 weeks after a prime-boost vaccination regimen. Consistent with the in vitro expression data, the highest levels of in vivo immunogenicity in terms of induction of env-specific CMI responses and env binding serum antibody were seen when the encoded HIV-16101 env gene was under the control of the murine or human CMV promoter. Substantially lower levels of env-specific T-cell activity and lower serum antibody responses were seen after immunization with the vector expressing the env protein under control of the simian CMV promoter, while immunization with the plasmid encoding the HSV lap1 promoter failed to elicit a significant env-specific T cell response or env binding serum antibody.

3.3. Effect of additional coding sequence modifications on in vitro protein expression and in vivo immunogenicity

Having determined that RNA or codon optimization is essential for increasing env expression and having determined that the greatest level of in vitro expression and in vivo immunogenicity were achieved by using the HCMV derived immediate-early promoter, we sought to determine if additional coding and non-coding sequence modifications could be used in combination with RNA optimization to further improve in vitro protein expression and in vivo immunogenicity.

Starting with the prototype HIV-1 env pDNA vaccine vector encoding an RNA optimized env gp160 gene under control of the HCMV promoter (WLV-106), additional HIV env pDNA expression vectors encoding various post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications were prepared (Table 1). Post-transcriptional modifications included the use of SRV-1 CTE or RTE which have been shown previously to greatly improve mRNA transport of native unoptimized HIV transcripts from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [50–52,73,74]. Post-translational modifications included the generation of env fusion proteins. For example, the HiV-16101 env gp160 protein was fused to a TPA derived signal leader sequence in an effort to improve env protein secretion. In addition, a beta-catenin-env fusion was prepared that was expected to target the protein for rapid degradation. Finally, a MCP3-env fusion protein was prepared which we hypothesized would result in improved antigen presentation as a result of increased infiltration of professional APCs. Using these 5 different post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications, a panel of plasmid DNA expression vectors incorporating the RNA transport elements by themselves, incorporating the fusion proteins themselves, or combining the fusion constructs with the RNA transport elements were prepared (Table 1).

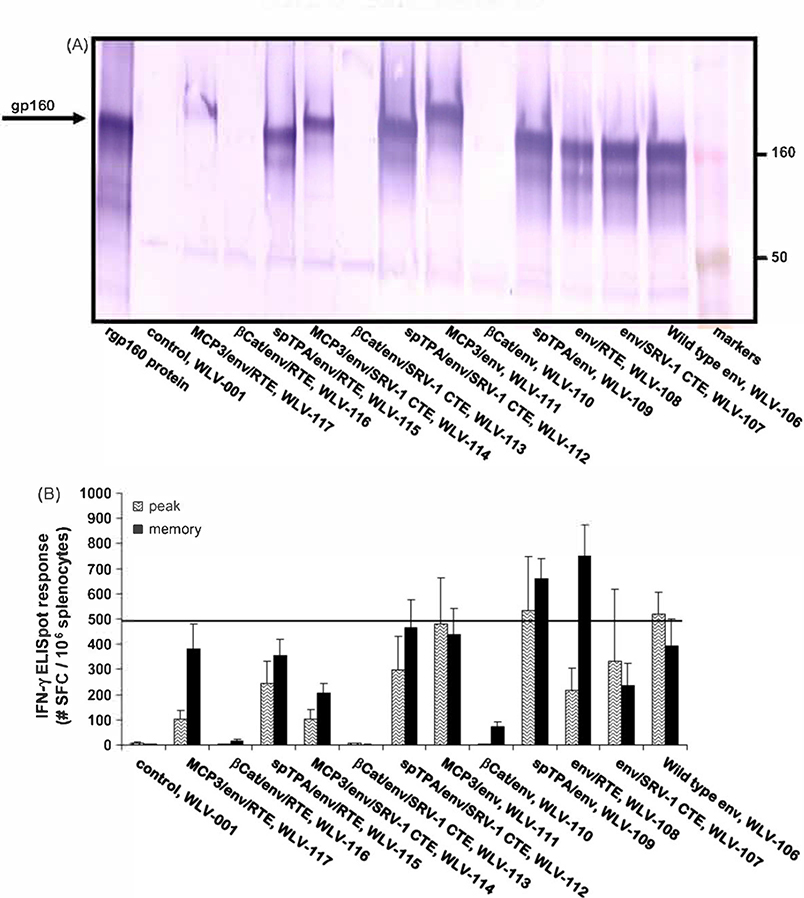

Following transient transfection of human 293 T cells, the relative in vitro expression of the HIV-16101 env gp160 protein from these various pDNA expression vectors was determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A). A number of vectors encoding an RNA optimized env gene in combination with additional modifications were identified that resulted in env gp160 expression levels that were equal to, but not significantly increased relative to the WLV-106 vector encoding the RNA optimized env gene alone. However, a number of vectors encoding RNA optimized env genes in combination with additional modifications demonstrated dramatically reduced env protein expression relative to the WLV-106 vector encoding the RNA optimized env gene alone. Most of the vectors with reduced protein expression profiles contained the beta-catenin derived element and this reduced protein expression by Western blot is consistent with the env protein being targeted for rapid degradation.

Fig. 4.

Relative in vitro protein expression and in vivo immunogenicity of pDNA vectors encoding RNA optimized HIV-16101 env gp160 genes further altered by the addition of various protein or mRNA elements. (A) HIV-16101 env protein expression by Western blot. 293 Tcells were transfected with 2 mcg of the indicated plasmid DNA expression vector (see Table 1). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell supernatants were subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and proteins were visualized by Western blot using a polyclonal anti-HIV env gp160 antibody. (B) HIV-16101 env gp160-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses after pDNA immunization. Groups of mice (n = 6) were immunized i.m. with the indicated pDNA expression vectors (100 mcg total vaccine dose) in combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12. Peak (10 days post-single immunization) and memory (6 weeks post-prime-boost on a schedule of0 and 3 weeks) HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific cell-mediated immune responses were quantitated in splenocytes by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Data are presented as the average response with the standard error of the mean indicated.

The relative immunogenicity of the various expression vectors was also determined by HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific IFN-γ ELISpot assay (Fig. 4B). For this experiment, Balb/c mice (n = 6 per group) were immunized with 100 mcg of the indicated expression vector in combination with 25 mcg plasmid-based murine IL-12. Peak and memory HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses were then quantitated either 10 days after a single immunization or 6 weeks after a prime-boost vaccination regimen. The data indicate that the vectors engineered to encode an RNA optimized env gp160 gene further modified to include a ubiquitination signal derived from beta-catenin, the same vectors which failed to demonstrate measurable in vitro protein expression when screened by Western blot, also uniformly failed to elicit measurable in vivo env-specific IFN-γ ELIspot responses. However, at least two expression vectors (WLV-108 and −109) engineered to express an RNA optimized env gp160 gene encoding further modifications appeared to elicit increased env-specific memory T cell responses relative to the WLV-106 vector encoding the RNA optimized env gene alone, though these differences did not achieve statistical significance.

3.4. Additional post-transcriptional and post-translational genetic modifications do not alter the breadth or the protective capacity of the resulting CMI response

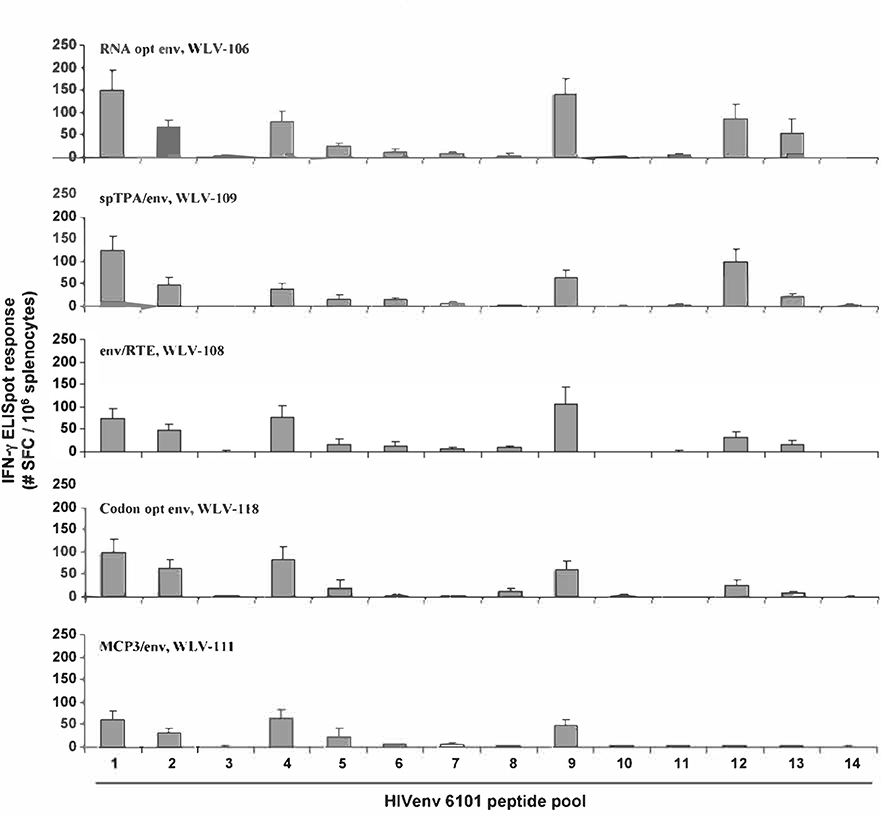

The top performing expression vectors encoding the further modified HIV-16101 env gp160 genes were further evaluated for differences in the breadth of the resulting CMI response. For these studies, Balb/c mice (n = 6 per group) were immunized with 100 mcg of the various env expression vectors and 10 days later spleens were harvested and screened for the induction of HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific lFN-γ secretion by ELISpot assay (Fig. 5). In this particular experiment, 15 mer peptides spanning the entire gp160 amino acid sequence were equally divided amongst 14 pools to give a rough sense of the number of potential epitopes being targeted.

Fig. 5.

Relative breadth of the resulting cell-mediated immune response after vaccination with various pDNA expression vectors encoding modified HIV-16101 env gp16O genes. Groups of mice (n = 6) were immunized i.m. with the indicated pDNA expression vectors (100 mcg total vaccine dose) in combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12. Peak (10 days post-single immunization) HIV-16101 env gp16O peptide pool-specific cell-mediated immune responses were quantitated in splenocytes by IFN-γ ELISpot assay using fourteen different peptide pools spanning HIV-16101 env gp16O. Data are presented as the average response with the standard error of the mean indicated.

It was found that following immunization with the plasmid expression vector WLV-106 encoding the RNA optimized env gene without further genetic modification, env peptide pool-specific IFN-γ secretion was seen to be directed against 6 of the 14 peptide pools tested. Immunization with vectors encoding the RNA optimized env genes in the context of additional genetic modifications did not result in a substantially different response pattern.

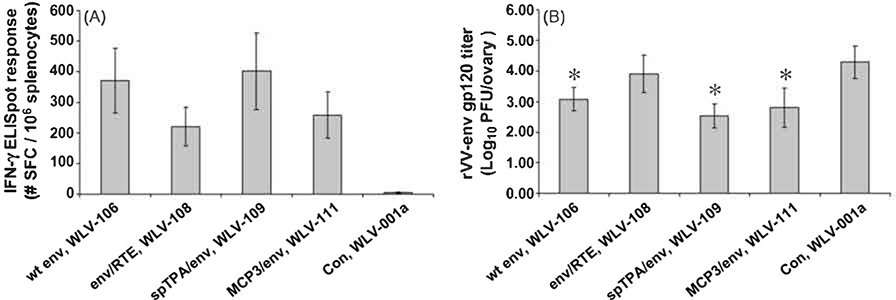

To further analyze the expression vectors encoding RNA optimized env genes in the context of additional genetic modifications, we monitored the relative protective efficacy of the modified and unmodified env genes in a vaccinia virus murine challenge model. For these experiments, mice (n = 20/group) were immunized with 100 mcg of the various env expression vectors in combination with plasmid IL-12. Ten days after the primary immunization, mice were divided into two groups (n = 10/group) and either screened for the induction of HIV-16101 env gp160 peptide pool-specific IFN-γ ELISpot responses (Fig. 6A) or challenged i.p. with 5 × 106 pfu of vaccinia virus expressing the homologous wild-type HIV-16101 gp120. Five days after vaccinia virus challenge, mice were sacrificed and ovaries harvested for the determination of vaccinia virus titers (Fig. 6B). Control vaccinated mice which were subsequently challenged with a vaccinia virus expressing HIV-16101 env gp120 had, on average, approximately 4-logs of virus in their ovaries 5 days after challenge. Mice immunized with the WLV-106 plasmid expression vector encoding the RNA optimized env gene without further genetic modification demonstrated, on average, a 1-log reduction in vaccinia virus titers post-challenge, a difference that was statistically significant relative to control immunized mice (p < 0.05). Consistent with the in vitro expression data and the in vivo immunogenicity data, mice immunized with the plasmid expression vectors encoding the RNA optimized env genes in the context of additional genetic modifications failed to demonstrate a significantly increased ability to clear the vaccinia virus challenge relative to mice immunized with the WLV-106 plasmid expression vector encoding the RNA optimized env gene without further genetic modifications.

Fig. 6.

Relative in vivo immunogenicity and in vivo efficacy of various pDNA vectors encoding modified HIV-16101 env gp160 genes. Groups of mice (n = 20) were immunized i.m. with the indicated pDNA expression vectors (100 mcg total vaccine dose) in combination with 25 mcg plasmid murine IL-12. Ten days after a single immunization. (A) groups of mice (n = 10) were sacrificed and HIV-16101 env gp16O peptide pool-specific cell-mediated immune responses were quantitated in splenocytes by IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Data are presented as the average response with the standard error of the mean indicated. (B) Groups of mice (n = 10) were challenged with 5 × 106 pfu of a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HIV-16101 env gp120 by the i.p. route. Five days after rW-env challenge, mice were sacrificed, ovaries harvested and rW-env titers were determined by plaque assay. Filled bars represent the mean response with the standard error of the mean indicated. Asterisk(*) represents a statistically significant (p < 0.05) reduction in rW-env titers relative to control immunized mice.

4. Discussion

The early resolution and control of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in humans and of simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) infection in non-human primates is thought to be mediated largely by the virus-specific cell-mediated immune response [36,37]. For this reason, vaccine approaches designed specifically to elicit potent, virus-specific, cellular immune responses are being developed as prophylactic vaccines for HIV. This approach has been validated by recent studies in non-human primates which have demonstrated containment of virus challenge in the absence of a pre-existing virus-specific neutralizing antibody response [78] and a correlation between pre-challenge vaccine-elicited CTL responses and post-challenge outcome [38,39].

Recently, we identified several candidate pDNA vaccine designs capable of eliciting robust and balanced CMI responses to multiple HIV-1 derived antigens in mice [79] and further tested these candidate pDNA vaccines for their ability to elicit HIV-1 antigen-specific CMI and humoral immune responses in rhesus macaques [80]. As a follow-on to these studies, we sought to determine if the incorporation of several post-transcriptional and post-translational genetic modifications could improve the ability of candidate pDNA vaccines to elicit antigen-specific humoral and cell-mediated immune (CMI) responses. For these studies, we focused on identifying means to improve humoral and CMI responses elicited by a prototype plasmid DNA expression vector encoding a clade B primary islolate HIV-16101 env gp160 gene [79,80]. Post-transcriptional modifications to be tested included (i) RNA optimization [45–47]; (ii) codon optimization [48.49,69], or (iii) the incorporation of a simian retrovirus type 1 (SRV-1) constitutive RNA transport element (CTE) [81] or a functionally similar but structurally unrelated post-transcriptional RNA Transport Element (RTE), which is present in a subgroup of murine intracisternal A particle retroelements [50,52]. Post-translational modifications included expressing the HIV-16101 env gp160 protein as a fusion with (i) a tissue plasminogen activator protein signal leader sequences; (ii) a beta-catenin derived ubiquitination target sequence [70,71], or (iii) a monocyte chemotactic protein-3 derived signal sequence [71,72]. Collectively, the studies outlined here indicate that genetic alteration of the HIV-16101 env gp160 gene by RNA or codon optimization alone was necessary and sufficient for high-level rev-independent expression in vitro. In addition, this increased expression resulted in the induction of robust env-specific serum antibody and CMI responses in immunized mice. Importantly, additional post-transcriptional and/or post-translational genetic modification(s) of the env gene failed to improve the magnitude, breadth, or protective capacity of the env-specific immune response.

In the current study, the ability of the various post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications to improve the resulting antigen-specific immune response was tested using a single prototype pDNA expression vector encoding a clade B primary isolate HIV-16101 env gp160 gene. In, addition, the ability of the various post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications to improve the resulting antigen-specific immune response was only tested in the context of RNA optimization using a limited number of immunological assays. Previously it has been shown that the addition of the CTE or RTE RNA export elements greatly increases in vitro expression of the unaltered HIV and SIV gag/pol and env mRNAs [50–52,73,74]. In the current study, the presence of CTE or RTE within an already optimized mRNA did not further increase antigen expression in tissue culture or improve vaccine-specific immune responses in vaccinated mice. This suggests that RNA or codon optimization removes all the post-transcriptional restrictions embedded within the native HIV env transcript, rendering these mRNAs fully competent for efficient export and translation. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that several of the post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications tested here may have resulted in improved protein expression in vitro and improved antigen-specific immune responses in vivo had they been tested outside the context of RNA optimization.

In the current study, we also failed to demonstrate that targeting the env protein for rapid proteosomal degradation would result in improved induction of env-specific CMI responses. These results are inconsistent with early published work showing that rapid proteosomal degradation can be used to enhance CTL responses to various model antigens [63,65]. However, others more recently have reported that targeting the hepatitis C virus core antigen [82] or the HIV-1 gag protein [67] for proteosomal degradation via the ubiquitin pathway does result in an antigen-specific CTL response. but this response did not exceed that seen with the unmodified antigen. In contrast. in the current study, targeting the env protein for rapid proteosomal degradation resulted in a highly unstable env protein that could not be detected by Western blot. leading to a complete abrogation of the antigen-specific immune response. The reason our rapidly degraded β-CAT-env fusion failed to elicit a measurable immune response is not completely understood, but could perhaps be explained as follows; (i) it is becoming increasingly clear that cross-presentation of plasmid DNA vaccine encoded antigens is a major mechanism of T cell induction [83–85] and this cross-presentation is dependant to a large extent on the transfer of intact antigens [55,86–88]; (ii) work by Delamarre et al., has shown that CD4 T-helper immune responses after protein immunization of mice were enhanced when the antigen was made more resistant to lysosomal proteolysis [89]; finally (iii) Bins et al., has recently shown that the induction of CD8 cytotoxic T cell responses following DNA vaccination in mice is correlated with antigen stability within the cytosol [68]. Collectively, these data suggest that in vaccination settings where the immunogen is presented primarily by cross-presentation, the vaccine antigens should be engineered for maximum stability [87].

Previously we have shown that a DNA vaccine strategy utilizing a combination of native and modified forms of SIV antigens resulted in increased CMI and antibody responses against the virus [71]. In this study, rhesus macaques were immunized with plasmid DNA vaccines encoding native SIV gag and SIV env in combination with plasmid DNA vectors encoding fusions of the gag and env proteins to the secreted chemokine MCP3, targeting the viral proteins to the secretory pathway and to a beta-catenin (CATE) peptide, targeting the viral proteins to the intracellular degradation pathway. The combination of DNA vectors expressing native and modified form of SIV gag and env led to the development of a more balanced immune response. including both humoral and cellular immune responses. than previously observed in DNA-vaccinated macaques. In addition, the DNA-immunized macaques were able to significantly reduce viremia for a long period (8 months) following pathogenic challenge with SIVmac251 [71]. Thus, for the SIV gag and env genes, modifications that included RNA optimization and alterations of antigen targeting led to beneficial outcome in this vaccination study. Collectively, these data suggest that while the RNA optimized HIV-1 env genes incorporating additional post-transcriptional or post-translational modifications may not be more immunogenic than the RNA optimized HIV-1 env gene alone, these further modified env genes may be, by virtue of their altered intracellular localization and altered antigen processing, able to elicit a qualitatively different immune response which may result in increased protection in vivo.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a HIV-1 Vaccine Design and Development Team contract NIH/NIAID HVDDT NOl-Al-05397 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- [1].WHO. AIDS epidemic update, December; 2006.

- [2].Wolff JA, Malone RW, Williams P, Chong W, Acsadi G, Jani A, et al. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science 1990;247(4949 Pt (1));1465–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tang DC, De Vit M,Johnston SA. Genetic immunization is a simple method for eliciting an immune response. Nature 1992;356(6365):152–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ulmer JB, Donnelly JJ, Parker SE, Rhodes GH, Feigner Pl, Dwarki VJ, et al. Heterologous protection against influenza by injection of DNA encoding a viral protein. Science 1993;259(5102):1745–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sedegah M, Hedstrom R, Hobart P, Hoffman SL. Protection against malaria by immunization with plasmid DNA encoding circumsporozoite protein. PNAS 1994;91(21):9866–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Donnelly JJ, Ulmer JB, Shiver JW, Liu MA. DNA vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol 1997;15:617–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den H, Babiuk SL. Immunization of animals: from DNA to the dinner plate. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1999;72(1–2):189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Egan MA, Charini WA. Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Racz P,Tenner-Racz K, et al. Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gag DNA-vaccinated rhesus monkeys develop secondary cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and control viral replication after pathogenic SIV infection. J Virol 2000;74(16):7485–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wang R, Doolan DL, Le TP, Hedstrom RC, Coonan KM, Charoenvit Y, et al. Induction of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in humans by a malaria DNA vaccine. Science 1998;282(5388):476–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Calarota S, Bratt G, Nordlund S, Hinkula J, Leandersson AC, Sandstrom E, et al. Cellular cytotoxic response induced by DNA vaccination in HIV-1-infected patients. Lancet 1998;351(9112):1320–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].MacGregor RR, Boyer JD, Ugen KE, Lacy KE, Gluckman SJ, Bagarazzi ML, et al. First human trial of a DNA-based vaccine for treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: safety and host response. J Infect Dis 1998;178(1):92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tacket CO, Roy MJ, Widera G, Swain WF, Broome S, Edelman R. Phase 1 safety and immune response studies of a DNA vaccine encoding hepatitis B surface antigen delivered by a gene delivery device. Vaccine 1999;17(22):2826–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Calarota SA, Leandersson AC, Bratt G, Hinkula J, Klinman DM, Weinhold KJ, et al. Immune responses in asymptomatic HIV-1-infected patients after HIV-DNA immunization followed by highly active antiretroviral treatment. J Immunol 1999;163(4);2330–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Boyer JD, Chattergoon MA, Ugen KE, Shah A, Bennett M, Cohen A, et al. Enhancement of cellular immune response in HIV-1 seropositive individuals: a DNA-based trial. Clin Immunol 1999;90(1):100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].MacGregor RR, Boyer JD, Ciccarelli RB, Ginsberg RS, Weiner DB. Safety and immune responses to a DNA-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type I env/rev vaccine in HIV-infected recipients: follow-up data. J Infect Dis 2000;181(1):406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Swain WE, Heydenburg Fuller D, Wu MS, Barr LJ, Fuller JT, Culp J, et al. Tolerability and immune responses in humans to a Powderject DNA vaccine for hepatitis B. Dev Biol 2000;104:115–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Le TP, Coonan KM, Hedstrom RC, Charoenvit Y, Sedegah M, Epstein JE, et al. Safety, tolerability and humoral immune responses after intramuscular administration of a malaria DNA vaccine to healthy adult volunteers. Vaccine 2000;18(18):1893–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Roy MJ, Wu MS, Barr LJ, Fuller JT, Tussey LG, Spellers, et al. Induction of antigen-specific CDS+ T cells, T helper cells, and protective levels of antibody in humans by particle-mediated administration of a hepatitis B virus DNA vaccine. Vaccine 2000:19(7–8):764–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Boyer JD, Cohen AD, Vogt S, Schumann K, Nath B, Ahn L, et al. Vaccination of seronegative volunteers with a human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 env/rev DNA vaccine induces antigen-specific proliferation and lymphocyte production of beta-chemokines. J Infect Dis 2000;181(2):476–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Weber R, Bossart W, Cone R, Luethy R, Moelling K, Phase. I clinical trial with HIV-1 gp160 plasmid vaccine in HIV-1-infected asymptomatic subjects. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2001;20(11):800–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang R, Epstein J, Baraceros FM, Gorak EJ, Charoenvit Y, Carucci DJ, et al. Induction of CD4(+) T cell-dependent CDS(+) type 1 responses in humans by a malaria DNA vaccine. PNAS 2001;98(19):10817–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Conry RM, Curiel DT, Strong TV, Moore SE, Allen KO, Barlow DL, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a DNA vaccine encoding carcinoembryonic antigen and hepatitis B surface antigen in colorectal carcinoma patients. Clin Can Res 2002;8(9):2782–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Timmerman JM, Singh G, Hermanson G, Hobart P, Czerwinski DK, Taidi B, et al. Immunogenicity of a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding chimeric idiotype in patients with B-cell lymphoma. Can Res 2002;62(20):5845–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tagawa ST, Lee P, Snively J, Boswell W, Ounpraseuth S, Lee S, et al. Phase I study of intranodal delivery of a plasmid DNA vaccine for patients with Stage IV melanoma. Cancer 2003;98(1):144–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Rottinghaus ST, Poland GA, Jacobson RM, Barr LJ, Roy MJ. Hepatitis B DNA vaccine induces protective antibody responses in human non-responders to conventional vaccination. Vaccine 2003;21(31):4604–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Epstein JE, Charoenvit Y, Kester KE, Wang R, Newcomer R, Fitzpatrick S, et al. Safety, tolerability, and antibody responses in humans after sequential immunization with a PfCSP DNA vaccine followed by the recombinant protein vaccine RTS,S/AS02A. Vaccine 2004;22(13–14):1592–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mancini-Bourgine M, Fontaine H, Scott-Algara D, Pol S, Brechot C, Michel ML. Induction or expansion of T-cell responses by a hepatitis B DNA vaccine administered to chronic HBV carriers. Hepatology 2004;40(4):874–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zlotocha S, Staab MJ, Horvath D, Straus J, Dobratz J, Oliver K, et al. A phase I study of a DNA vaccine targeting prostatic Acid phosphatase in patients with stage DO prostate cancer. Clin Genitourinary Cancer 2005;4(3):215–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Miller AM, Ozenci V, Kiessling R, Pisa P Immune monitoring in a phase 1 trial of a PSA DNA vaccine in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Immunother 2005;28(4):389–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Triozzi PL, Aldrich W, Allen KO, Carlisle RR, LoBuglio AF, Conry RM. Phase I study of a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding MART-1 in patients with resected melanoma at risk for relapse. J Immunother 2005;28(4);382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tavel JA, Martin JE, Kelly GG, Enama ME, Shen JM. Gomez PL, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a Gag-Pol candidate HIV-1 DNA vaccine administered by a needle-free device in HIV-1-seronegative subjects. J Acquir Immune Def Syndrom; JAIDS 2007;44(5):601–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Martin JE, Sullivan NJ, Enama ME, Gordon IJ, Roederer M, Koup RA, et al. A DNA vaccine for Ebola virus is safe and immunogenic in a phase I clinical trial. Clin Vacc lmmunol: CVI 2006;13(11):1267–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Graham BS, Koup RA, Roederer M. Bailer RT, Enama ME, Moodie Z, et al. Phase I safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a multiclade HIV-I DNA candidate vaccine [see comment]. J Infect Dis 2006;194(12):1650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Drape RJ, Macklin MD, Barr LJ, Jones S, Haynes JR, Dean HJ. Epidermal DNA vaccine for influenza is immunogenic in humans. Vaccine 2006;24(21):4475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Barouch DH. Rational design of gene-based vaccines. J Pathol 2006;208(2): 283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Koup R, Safrit J, Cao Y, Andrews C, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, et al. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J Virol 1994;68(7):4650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Santra S, Sasseville VG, Simon MA, Lifton MA, et al. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CDS+ lymphocytes. Science 1999;283(5403):857–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Barouch DH, Santra S, Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Fu TM, Wagner W, et al. Control of viremia and prevention of clinical AIDS in rhesus monkeys by cytokine-augmented DNA vaccination. Science 2000;290(5491);486–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Egan MA, Chong S-Y, Megati S, Montefiori DC, Rose NF, Sidhu M, et al. Priming with plasmid DNAs expressing IL-12 and SIV gag protein enhances the immunogenicity and efficacy of an experimental AIDS vaccine based on recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 2005;7:629–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Egan MA, Israel ZR. The use of cytokines and chemokines as genetic adjuvants for plasmid DNA vaccines. Clin Appl lmmunol Rev 2002;2:255–87. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Barouch DH, Letvin NL, Seder RA. The role of cytokine DNAs as vaccine adjuvants for optimizing cellular immune responses. lmmunol Rev 2004;202:266–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Amara RR, Smith JM, Staprans SI, Montefiori DC, Villinger F, Altman JD, et al. Critical role for Env as well as Gag-Pol in control of a simian-human immunodeficiency virus 89.6P challenge by a DNA prime/recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara vaccine. J Virol 2002;76(12):6138–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Amara RR, Villinger F, Altman JD, Lydy SL, O’Neil SP, Staprans SI, et al. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science 2001;292(5514):69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Santra S, Barouch DH, Korioth-Schmitz B. Lord Cl, Krivulka GR,Yu F,et al. Recombinant poxvirus boosting of DNA-primed rhesus monkeys augments peak but not memory T lymphocyte responses. PNAS 2004;101(30):11088–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Schneider R, Campbell M, Nasioulas G, Felber B, Pavlakis G. Inactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitory elements allows Rev-independent expression of Gag and Gag/protease and particle formation. J Virol 1997;71(7):4892–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Schwartz S, Campbell M, Nasioulas G, Harrison J, Felber BK, Pavlakis GN. Mutational inactivation of an inhibitory sequence in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 results in Rev-independent gag expression. J Virol 1992;66(12):7176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schwartz S, Felber BK, Pavlakis GN. Distinct RNA sequences in the gag region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 decrease RNA stability and inhibit expression in the absence of Rev protein. J Virol 1992;66(1):150–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Haas J, Park E-C, Seed B. Codon usage limitation in the expression of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Curr Biol 1996;6(3):315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Andre S, Seed B, Eberle J. Schraut W, Bultmann A, Haas J Increased immune response elicited by DNA vaccination with a synthetic gp120 sequence with optimized codon usage. J Virol 1998;72(2):1497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Nappi F, Schneider R, Zolotukhin A, Smulevitch S, Michalowski D, Bear J, et al. Identification of a novel posttranscriptional regulatory element by using a rev- and RRE-mutated human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 DNA proviral clone as a molecular trap. J Virol 2001;75(10):4558–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Smulevitch S, Bear J, Alicea C. Rosati M, Jalah R, Zolotukhin AS, et al. RTE and CTE mRNA export elements synergistically increase expression of unstable, Rev-dependent HIV and SIV mRNAs. Retrovirology 2006;3:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Smulevitch S, Michalowski D, Zolotukhin AS, Schneider R, Bear J, Roth P, et al. Structural and functional analysis of the RNA transport element, a member of an extensive family present in the mouse genome. J Virol 2005;79(4):2356–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Barouch DH, Yang Z-y, Kong W-p, Korioth-Schmitz B, Sumida SM, Truitt DM, et al. A human T-cell leukemia virus Type 1 regulatory element enhances the immunogenicity of human immunodeficiency virus Type 1 DNA vaccines in mice and nonhuman primates. J Virol 2005;79(14):8828–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Espino AM. Osuna A, Gil R. Hillyer GV. Fasciola hepatica: humoral and cytokine responses to a member of the saposin-like protein family following delivery as a DNA vaccine in mice. Exp Parasitol 2005;110(4):374–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Shen L, Rock KL. Cellular protein is the source of cross-priming antigen in vivo. PNAS 2004;101(9):3035–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Peng S, Trimble C, Ji H, He L, Tsai YC, Macaes B, et al. Characterization of HPV-16 E6 DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting and intercellular spreading strategies. J Biomed Sci 2005;12(5):689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Pokorna D, Cerovska N, Smahel M, Moravec T, Ludvikova V, Mackova J, et al. DNA vaccines based on chimeric potyvirus-like particles carrying HPV16 E7 peptide (aa 44–60). Oncol Rep 2005; 14(4):1045–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Kim TW, Lee JH, He L, Boyd DA, Hung CF, Wu TC. DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting strategies and a strategy to prolong dendritic cell life generate a higher number of CDS+ memory T cells and better long-term antitumor effects compared with a DNA prime-vaccinia boost regimen. Hum Gene Ther 2005:16(1):26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Anwar A, Chandrasekaran A, Ng ML, Marques E, August JT. West Nile premembrane-envelope genetic vaccine encoded as a chimera containing the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of a lysosome-associated membrane protein: increased cellular concentration of the transgene product, targeting to the MHC II compartment, and enhanced neutralizing antibody response. Virology 2005;332(1):66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kim JW, Hung CF, Juang J, He L, Kim TW, Armstrong DK, et al. Comparison of HPV DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting strategies. Gene Ther 2004; 11(12): 1011–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].de Arruda LB, Chikhlikar PR, August JT, Marques ET. DNA vaccine encoding human immunodeficiency virus-1 Gag, targeted to the major histocompatibility complex II compartment by lysosomal-associated membrane protein, elicits enhanced long-term memory response. Immunology 2004;112(1):126–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Bacik I, Cox J, Anderson R, Yewdell J, Bennink J. TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing)-independent presentation of endogenously synthesized peptides is enhanced by endoplasmic reticulum insertion sequences located at the amino- but not carboxyl-terminus of the peptide. J Immunol 1994;152(2):381–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rodriguez F, Zhang J, Whitton J DNA immunization: ubiquitination of a viral protein enhances cytotoxic T-lymphocyte induction and antiviral protection but abrogates antibody induction. J Virol 1997;71(11):8497–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Wu Y, Kipps T. Deoxyribonucleic acid vaccines encoding antigens with rapid proteasome-dependent degradation are highly efficient inducers of cytolytic T lymphocytes. J lmmunol 1997;159(12):6037–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Tobery TW, Siliciano RF. Targeting of HIV-1 antigens for rapid intracellular degradation enhances cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) recognition and the induction of de novo CTL responses in vivo after immunization. J Exp Med 1997:185(5):909–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Leachman SA, Shylankevich M, Slade MD, Levine DK, Sundaram R, Xiao W, et al. Ubiquitin-fused and/or multiple early genes from cottontail rabbit papillomavirus as DNA vaccines. J Virol 2002;76(15):7616–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wong SBJ, Buck CB, Shen X, Siliciano RF. An evaluation of enforced rapid proteasomal degradation as a means of enhancing vaccine-induced CTL responses. J lmmunol 2004;173(5):3073–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bins AD, Wolkers MC, van den Boom MD, Haanen JBAG, Schumacher TNM. In vivo antigen stability affects DNA vaccine immunogenicity. J lmmunol 2007;179(4):2126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Smith L, Shahabi V, Sidhu M, inventors; Enhancing Protein Expression; 2005; PCT International Publication Number W02005/118874.

- [70].Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. Beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J 1997;16(13):3797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Rosati M, von Gegerfelt A, Roth P, Alicea C, Valentin A, Robert-Guroff M, et al. DNA vaccines expressing different forms of simian immunodeficiency virus antigens decrease viremia upon SIVmac251 challenge. J Virol 2005;79(13):8480–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Biragyn A, Tani K, Grimm MC, Weeks S, Kwak LW. Genetic fusion of chemokines to a self tumor antigen induces protective, T-cell dependent antitumor immunity. Nat Biotechnol 1999:17(3), 253–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Zolotukhin AS, Valentin A, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK. Continuous propagation of RRE(−) and Rev(−)RRE(−) human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones containing a cis-acting element of simian retrovirus type 1 in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Virol 1994;68(12):7944–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Tabernero C, Zolotukhin AS, Valentin A, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK. The post-transcriptional control element of the simian retrovirus type 1 forms an extensive RNA secondary structure necessary for its function. J Virol 1996;70(9):5998–6011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Shaw KJ, Rather PN, Hare RS, Miller GH. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol Rev 1993;57(1):138–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sadaie Y, Burtis KC, Doi RH. Purification and characterization of a kanamycin nucleotidyltransferase from plasmid pUB110-carrying cells of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 1980;141(3):1178–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Pachuk CJ, Ciccarelli rB, Samuel M, Bayer ME, Troutman RD, Zurawski DV, et al. Characterization of a new class of DNA delivery complexes formed by the local anesthetic bupivacaine. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000;1468(1–2):20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Robinson HL, Montefiori DC. Johnson RP, Manson KH, Kalish ML, Lifson JD, et al. Neutralizing antibody-independent containment of immunodeficiency virus challenges by DNA priming and recombinant pox virus booster immunizations [see comments]. Nat Med 1999;5(5):526–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Egan MA, Megati S, Roopchand V, Garcia-Hand D, Luckay A, Chong S-Y, et al. Rational design of a plasmid DNA vaccine capable of eliciting cell-mediated immune responses to multiple HIV antigens in mice. Vaccine 2006;24(21):4510–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Luckay A, Sidhu MK, Kjeken R, Megati S, Chong S-Y, Roopchand V, et al. Effect of plasmid DNA vaccine design and in vivo electroporation on the resulting vaccine-specific immune responses in rhesus macaques. J Virol 2007;81(10):5257–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Indraccolo S, Feroli F, Minuzzo S, Mion M, Rosato A, Zamarchi R, et al. DNA immunization of mice against SIVmac239 Gag and Env using Rev-independent expression plasmids. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir 1998;14(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Vidalin O, Tanaka E, Spengler U, Trepo C. Inchauspe G. Targeting of hepatitis C virus core protein for MhC I or MHC II presentation does not enhance induction of immune responses to DNA vaccination. DNA Cell Biol 1999;18(8):611–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Cho JH, Youn JW, Sung YC. Cross-priming as a predominant mechanism for inducing CD8+ T Cell responses in gene gun DNA immunization. J lmmunol 2001;167(10):5549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Doe B, Selby M, Barnett S. Baenziger J. Walker CM. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by intramuscular immunization with plasmid DNA is facilitated by bone marrow-derived cells. PNAS 1996;93(16):8578–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Corr M, von Damm A, Lee DJ, Tighe H. In vivo priming by DNA injection occurs predominantly by antigen transfer. J lmmunol 1999;163(9):4721–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Basta S, Stoessel R, Basler M, van den Broek M, Groettrup M. Cross-presentation of the long-lived lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus nucleoprotein does not require neosynthesis and is enhanced via heat shock proteins. J lmmunol 2005;175(2):796–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Norbury CC, Basta S, Donohue KB, Tscharke DC, Princiotta MF, Berglund P, et al. CD8+ T cell cross-priming via transfer of proteasome substrates. Science 2004;304(5675):1318–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Wolkers MC, Brouwenstijn N, Bakker AH, Toebes M. Schumacher TNM. Antigen bias in T cell cross-priming. Science 2004;304(5675):1314–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Delamarre L, Couture R, Mellman I, Trombetta ES. Enhancing immunogenicity by limiting susceptibility to lysosomal proteolysis. J Exp Med 2006;203(9):2049–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]