Abstract

Several studies have shown that over 70 different microRNAs are aberrantly expressed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), affecting proliferation, apoptosis, metabolism, EMT and metastasis. The most important genetic alterations driving PDAC are a constitutive active mutation of the oncogene Kras and loss of function of the tumour suppressor Tp53 gene. Since the MicroRNA 34a (Mir34a) is a direct target of Tp53 it may critically contribute to the suppression of PDAC. Mir34a is epigenetically silenced in numerous cancers, including PDAC, where Mir34a down-regulation has been associated with poor patient prognosis. To determine whether Mir34a represents a suppressor of PDAC formation we generated an in vivo PDAC-mouse model harbouring pancreas-specific loss of Mir34a (KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ). Histological analysis of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice revealed an accelerated formation of pre-neoplastic lesions and a faster PDAC development, compared to KrasG12D controls. Here we show that the accelerated phenotype is driven by an early up-regulation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFA and IL6 in normal acinar cells and accompanied by the recruitment of immune cells. Our results imply that Mir34a restrains PDAC development by modulating the immune microenvironment of PDAC, thus defining Mir34a restauration as a potential therapeutic strategy for inhibition of PDAC development.

Subject terms: Cancer, Gastroenterology

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the third-leading cause of cancer-related death in the world, with a 5-year survival rate which, despite the great scientific efforts and new therapeutic technology, has only improved from 5% to 8% in the last years1. This low survival rate is the result of a combination of factors, including lack of early symptoms, lack of non-invasive detection methods and/or biomarkers, strong resistance of the tumour to chemotherapy, and a rapid metastatic spread. Surgery is the only curative option, but only a small percentage of patients qualify for resection at the time of diagnosis2.

A constitutively active form of the KRAS oncogene is the main driver mutation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) occurring in 90% of the cases3; out of these, the substitution of G12D occurs in 41% of the cases, followed by G12V occurring in 34% of the cases and G12R in 16% of the cases4. KrasG12D expression in epithelial cells leads to activation of inflammatory pathways and results in paracrine signalling with the surrounding stroma. This promotes formation and maintenance of a desmoplastic, fibro-inflammatory microenvironment, which favours the step-wise progression of normal exocrine pancreas into pre-invasive precursor acinar to ductal metaplasia (ADM) and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) lesions and PDAC development5. Additionally, loss of function of tumour suppressor genes, such as p53, p16 and SMAD4, also drives progression of the disease6.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs of 20 to 25 nucleotides in length that regulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level by binding the 3′-untranslated region of target mRNAs suppressing their translation and promoting their degradation7,8. Increasing evidence has shown that the expression of miRNAs is deregulated in human cancers affecting hallmark processes, such as proliferation, apoptosis, metabolism, EMT and metastasis9–11. Several microRNA encoding genes are induced by p53, among them the miR-34 gene family12. The Mir34 family is composed of Mir34a, Mir34b and Mir34c. In humans, MIR34b and c are located in chromosome 11q23.1 and transcribed from the same poly-cistronic transcript (they are located in the same exon), whereas MIR34a is encoded by a separate transcript located on chromosome 1p36.22. While MIR34b/c are mainly expressed in lung tissue13, MIR34a is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues14–16; suggesting tissue-specific functions for the different members of the Mir34 family (this is also the case in mice14). Members of the Mir34 family are directly activated by p5314,17–19, among them, Mir34a is a well-known key tumour suppressor15,20,21. In cancer cells, there are two main mechanisms to inactivate tumour suppressor genes: transcriptional silencing by methylation of CpG islands and genomic loss. Evidence of both mechanisms have been reported for miR-34: previous studies showed how the CpG islands in the Mir34a promoter are methylated (correlating with Mir34a silencing) in different solid tumours, including pancreatic cancer16,22; and, genomic loss of the chromosomal region (1p36) of Mir34a has been reported in neuroblastoma20,23.

Several studies confirmed that Mir34a is downregulated in PDAC and many other cancers (reviewed in10,24,25) and that it blocks tumour growth by inhibiting genes involved in various oncogenic signalling pathways. In vitro studies revealed that MIR34a is downregulated in human pancreatic cancer cells26, where it modulates Notch1 signalling, Bcl2, and EMT27–31.

In human PDAC patients, loss of MIR34a expression is associated with poor patient prognosis, and MIR34a levels in serum have been proposed as diagnostic biomarker for PDAC30,32–34. Additionally, Mir34a has a great therapeutic potential35, and it has already been tested in pre-clinical studies, where Mir34a mimics (in combination with PLK1 siRNA) was delivered using an amphiphilic nano-carrier and led to improved therapeutic response in mice36.

Based on the above data, a tumour suppressive function of Mir34a is assumed, however, this has not been functionally tested in vivo. Here, we present an in vivo study of the tumour suppressive role of Mir34a in PDAC using genetically engineered mouse models. Mir34a is conditionally inactivated in pancreatic tissue in a KrasG12D-driven PDAC model, leading to the fast development of pre-neoplastic lesions and PDAC. This acceleration of the phenotype is driven by a cell-autonomous mechanism whereby the acinar cells generated an autocrine inflammatory response leading to recruitment of immune cells.

Results

Mir34a knockout mice rapidly develop pancreatic lesions at an early stage

To study the role of Mir34a in pancreatic carcinogenesis, the effect of conditionally knocking out Mir34a during pancreatic exocrine development was examined by crossing Mir34afl/fl mice37, with Ptf1a+/Cre mice (hereafter called: Mir34aΔ/Δ) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Since Mir34a is not expressed in normal pancreas, impairment of pancreatic exocrine development was not expected. As predicted, Mir34aΔ/Δ mice developed normally and showed no obvious phenotype. Body weight and pancreas body weight ratio were comparable between the two groups (Supplementary Fig. 1B,C), and neither macroscopic nor histological differences were observed (Supplementary Fig. 1D,E). Furthermore, expression of pri-Mir34a in Mir34aΔ/Δ mice was undetectable like on the WT controls (Supplementary Fig. 1F). Additionally, no compensatory effect arising from the expression of the other members of the Mir34 family (namely, Mir34b and Mir34c), was found (Supplementary Fig. 1G). Therefore, Mir34a is not required for pancreatic development, and its absence does not result in compensatory upregulation of Mir34b or Mir34c.

To study the role of Mir34a in pancreatic cancer development we crossed the Mir34afl/fl mice with the well described Kras mouse model for PDAC38 to generate Ptf1a+/Cre; Kras+/LSL-G12D; Mir34afl/fl mice (hereafter called: KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ), which were analysed at specific time points.

At 1 month of age, the body weight and pancreas to body weight ratio were not significantly different in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 2A,B). Macroscopically, no difference between the pancreas from the two groups was observed (Fig. 1A). However, histological analysis revealed that KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice already presented lesions (Fig. 1A). The area of remodelled tissue (containing ADM and PanIN lesions) was quantified, and as seen by HE analysis, KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice presented a significantly higher percentage of remodelled tissue (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, this early remodelled phenotype was conserved at 3 months of age (Fig. 1C,D) and KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice presented macroscopically a more fibrotic pancreas (Fig. 1C). These findings were confirmed by CK19 and MUC5AC staining as markers for ADM and PanIN lesions, respectively (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Fig. 2C). The ADM and PanIN lesions from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice were not more proliferative (Supplementary Fig. 2D,E) nor apoptotic (Supplementary Fig. 2D,F) compared to those from the KrasG12 control mice. Overall, these results show that KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice present an acceleration in the development of ADM and PanIN pancreatic lesions, compared to KrasG12D mice.

Figure 1.

Mir34a knockout accelerates the development of ADM and PanIN lesions from a young age. (A) Macroscopic view of the pancreas of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls and haematoxylin eosin (HE) staining on whole slide and a 20 × zoomed in area, at 1 month of age. Scale bar 50 µm. (B) Quantification of the amount of pancreatic tissue remodelled (with ADM and PanIN lesions), expressed as percentage, in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls at 1 month of age (N ≥ 3 per group). (C) Macroscopic picture and HE staining of the pancreas from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls at 3 months of age. Scale bar 50 µm. (D) Quantification of the area of pancreatic tissue remodelled shown in percentage, in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls at 3 months of age (N ≥ 7 per group). (E) Quantification of the amount of ADM and PanIN lesions per high power field (HPF) in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls (N ≥ 7 per group).

Preneoplastic lesions of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice progress to invasive carcinomas at 6 months of age

To gain more information about the acceleration phenotype, mice at 6 months of age were analysed. Macroscopically, the pancreas of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice often presented areas with a hard mass, in comparison to that of KrasG12D mice which did not show macroscopic tumours (Fig. 2A). These differences were also observed histologically, the pancreas of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice was very fibrotic and almost lacked normal exocrine areas (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the pancreas of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice presented significantly larger remodelled areas (Fig. 2B) with slightly more CK19 positive ADMs and significantly more MUC5A positive PanIN lesions (Fig. 2C,D). Of note, KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice already presented significantly more invasive carcinoma (including areas with microscopic carcinomas) in comparison to KrasG12D controls (Fig. 2E,F). Therefore, these results show that the preneoplastic lesions observed in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice at an early age are aggressive and can quickly develop into invasive carcinomas already at 6 months of age.

Figure 2.

Mir34a knockout mice present invasive carcinomas at 6 months of age. (A) Macroscopic view of the pancreas of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls, HE staining of whole slide and a 20x zoomed in area at 6 months of age. (B) Quantification of the area, shown in percentage, of pancreatic tissue remodelled in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. (N ≥ 8 per group). (C) Immunohistochemistry staining of the ductal marker CK19 and the PanIN marker MUC5A in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. (D) Quantification of ADM and PanIN lesions at 6 months of age in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. (N ≥ 8 per group). (E) HE staining showing an area of ADM and PanIN lesions in KrasG12D mice compared to an area of PanIN lesions, stroma (S) and tumour (T) in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice. (F) Quantification of presence of invasive carcinomas, shown in percentage, in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. Fisher’s test (N = 22). (A,C,E). Scale bar 50 µm.

At terminal stage the majority of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice presented a fully remodelled pancreas (Fig. 3A) but did not developed significantly more carcinomas than KrasG12D mice (Fig. 3B). The lack of difference of invasive carcinoma was in agreement with the lack of increased metastasis to the lung and liver in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ (Supplementary Fig. 3A). In line with these results, the tumours of the two genotypes were macroscopically and histologically indistinguishable (Fig. 3C). Survival analysis between both groups presented a trend towards lower survival in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice (Supplementary Fig. 3B) supporting the acceleration phenotype hypothesis; however, the difference was not significant. Overall, these results show that the acceleration in lesion formation in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice results in higher tumour penetrance already at 6 months of age, and in a trend towards lower survival without affecting the metastatic potential.

Figure 3.

Mir34a knockout mice present more invasive carcinomas than KrasG12D mice at terminal stage. (A) Percentage of pancreatic tissue remodelling from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls at terminal stage (N ≥ 9 per group). (B) Quantification of presence of invasive carcinomas in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls, shown in percentage. Fisher’s test (N = 33) OR4 (0.81,16.87). (C) Macroscopic picture of the invasive carcinoma from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to that of KrasG12D controls and HE staining of the invasive carcinoma area. Scale bar 50 µm.

Mir34a ablation leads to a cell-autonomous activation of inflammatory pathways

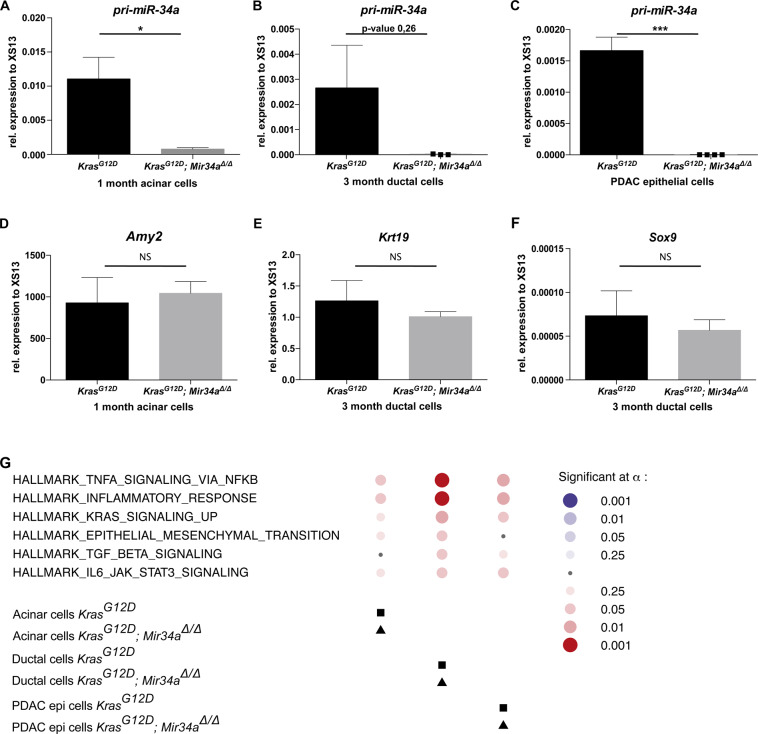

In order to gain insights into the mechanism of accelerated tumour formation and to avoid heterogeneous results due to the significant differences between the areas of normal exocrine tissue and those with pancreatic remodelling, specific cell types of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ and KrasG12 mice at each time point were isolated. Acinar cells were isolated from pancreata of 1 month old mice (since KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ still present areas of normal exocrine tissue), ductal cells from remodelled pancreata of 6-month-old mice, and epithelial tumour cells were isolated from the invasive carcinomas of terminal mice. The purity of the isolated cells was assessed by gene expression analysis. All cells derived from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice did not express Mir34a (as shown by absence of pri-Mir34a mRNA expression) compared to KrasG12D controls (Fig. 4A–C). Acinar cells from both KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ and KrasG12 mice, expressed comparable mRNA levels of Amylase (Fig. 4D) and did not express mRNA from the ductal marker CK19 (data not shown). In contrast, the ductal cells from both KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ and KrasG12 mice expressed comparable mRNA levels of the ductal markers CK19 (Fig. 4E) and SOX9 (Fig. 4F) and they did not express mRNA from the acinar marker Amylase (data not shown). Therefore, the same subtype of cells was isolated in both genotypes.

Figure 4.

Upregulation of key signalling pathways in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. (A) RNA expression of pri-Mir-34a in acinar explants at day 0 after isolation from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice and KrasG12D controls at 1 month of age. Welch’s t-test (N = 4 per group). (B) RNA expression of pri-Mir-34a in ductal cells isolated from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls at 3 months of age. Welch’s t-test (N = 3 per group). (C) Expression of pri-miR34a in cell lines isolated from tumour tissue of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls at terminal stage. Welch’s t-test (N ≥ 4 per group). (D) RNA expression of the acinar marker Amylase in acinar explants at day 0 after isolation from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice and KrasG12D controls at 1 month of age. Welch’s t-test (N = 4 per group). Differences are not statistically significant. (E,F) RNA expression of the ductal marker CK19 (E) and SOX9 (F) in ductal cells isolated from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls at 3 months of age. Welch’s t-test (N = 3 per group). Differences are not significant. (G) Bubble plot showing the top 6 pathways enriched in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls after performing gene set enrichment analysis in RNA extracted from acinar cell explants at 1 month of age, ductal cells at 3 months of age, and at tumour cells at terminal stage. Red circles show upregulated pathways and blue downregulated. The size of the circle represents the p-value. Squares represent the reference group (KrasG12D mice), and triangles the treatment group (KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice).

In a second step, RNA sequencing and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the aforementioned cell types were performed. RNA from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice showed an enrichment in the following pathways: TNFA via NFKB, inflammatory response, Kras signalling up, EMT, TGFB, IL6-JAK-STAT3, across cell types compared to that of KrasG12 controls (Fig. 4G and Supplementary Table 1). This result suggests that acinar cells generate an autocrine inflammatory response. Furthermore, this result supports the lesion acceleration hypothesis by showing an enrichment in Kras signalling already in ductal cells at 3 months of age.

To confirm our hypothesis of a faster lesion development in the KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice, acinar cell explants from 1-month old mice were isolated, cultured and their transdifferentiation into ductal cells was followed for 3 days (Fig. 5A). Acinar cells from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice showed accelerated ADM transdifferentiation rates in vitro (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. 4B). Therefore, acini from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice transdifferentiate into ductal structures, faster than KrasG12 controls, in a cell-autonomous manner.

Figure 5.

Mir34a knock out results in an inflammatory phenotype. (A) Average of the transdifferentiation rate of acinar cell explants from pancreata of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ and KrasG12D mice into acini, duct-like and duct structures (N ≥ 3 per group). Unpaired Student’s t-test with combined SD. (B) RNA expression of members of the NFKB signalling pathway: Tnfa, Nfkb, Il6, and Nfkbia, in acinar cell explants directly after isolation (day 0) from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. Welch’s t-test (N = 4 per group). (C) Immunohistochemistry staining for CD45 in tissue from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. Scale bar 50 µm. (D) Quantification of CD45 positive cells per high power field in areas of normal tissue from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls (N ≥ 3 per group). (E) Immunohistochemistry staining for NFKB in tissue from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. Scale bar 50 µm. (F) Quantification of NFKB positive nuclei from acinar cells in areas of normal tissue per high power field from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls (N ≥ 3 per group). (G) Immunohistochemistry staining for P-STAT3 in tissue from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls. Scale bar 50 µm. (H) Quantification of P-STAT3 positive nuclei from acinar cells in areas of normal tissue per high power field from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12D controls (N ≥ 3 per group).

Next, the mRNA expression levels of members of the signalling pathways enriched by GSEA were analysed in acinar cell explants. RNAs of freshly isolated acinar cell explants were analysed; expression of Tnfa, Nfkb, Il6 and Nfkbia was significantly upregulated in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ acinar cell explants (Fig. 5B). This result validates the GSEA results observed after sequencing. In summary, our results suggest that acinar cells of KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice develop to ADM in a cell-autonomous manner and they secrete factors which attract inflammatory cells, possibly accounting for the acceleration of invasive carcinoma development.

To confirm this hypothesis, the presence of inflammatory cells in the non-remodelled pancreas at 1 month of age was analysed (Fig. 5C). There were significantly more CD45 positive cells in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice compared to KrasG12 controls (Fig. 5D). In addition, we validated an active TNFA and IL6 signalling in acinar cells by immunohistochemical staining of NFKB and P-STAT3 (Fig. 5E,G, respectively). The acinar cells from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice had a slightly increased NFKB expression and significantly more P-STAT3 expression compared to KrasG12 controls (Fig. 5E–H). These results demonstrate that in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice TNFA and IL6 expression is increased in the acinar compartment already at the age of 1 month leading to an inflammatory response and recruitment of inflammatory cells to the tissue.

Discussion

Many studies showed that plenty of microRNAs (miRNAs) are deregulated in PDAC, among them Mir34a is often downregulated and is a promising biomarker with prognostic value that correlates with diagnosis39–41. However, the exact mechanism by which Mir34a exerts its tumour suppressor role in PDAC is not clear yet.

Here we present an in vivo study where we investigated the role of Mir34a in PDAC carcinogenesis using genetically engineered mouse models. Conditional deletion of Mir34a in the pancreas of mice led to a significant acceleration in the formation of pancreatic pre-neoplastic ADM and PanINs lesions already at the age of 1 month. Furthermore, this also accelerated the formation of pancreatic invasive carcinomas, which were present already at 6 months of age. These results resemble the data from human PDAC patients in which patients with low Mir34a expression present a lower survival rate30,32–34. Furthermore, in agreement with our histological observations, acinar explants isolated from the pancreas of 1-month-old mice transdifferentiated faster into ductal structures in culture, suggesting a cell-autonomous mechanism. We hypothesized that the reason is that Mir34a ablation in acini from KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice results in an alteration of signalling pathways promoting acinar differentiation. As shown by RNA sequencing and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), EMT, TGFB, IL6-JAK-STAT3, TNFA via NFKB, Kras signalling up, and inflammation pathways are enriched in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice. Additionally, the expression of Tnfa, Nfkb and Il6 is significantly increased, there are significantly more CD45 positive immune cells in areas of normal exocrine tissue, and significantly more NFKB and P-STAT3 accumulates in the nucleus of normal acinar cells. Based on all of these results, and since persistent inflammation in a KrasG12D setting results in PDAC42, it is plausible that depletion of Mir34a expression drives an upregulation of the inflammatory cytokines, specifically in acinar cells. This leads to NFKB and P-STAT3 activation (favouring pre-neoplastic lesion development and carcinogenesis) and to the recruitment of inflammatory cells which eventually accelerate PDAC development. In line with these findings, Mir34a was shown to negatively regulate the IL6R/STAT3 pathway in sporadic and colitis-associated colorectal cancer and thereby contribute to invasion and metastasis37,43.

MicroRNAs (mRNAs), including Mir34a, were reported to be key inflammation regulators (reviewed in44). The signalling pathways enriched by GSEA in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice, are inflammatory pathways strongly related between themselves and their upregulation was in line with the literature. One of the signalling pathways enriched at early time points was TGFB. A recent study with mouse models, revealed that activation of TGFB pathway during early pancreatic tumorigenesis induces ADM reprogramming, by activating apoptosis and cell differentiation and provides a favourable environment for the development of KrasG12D-driven preneoplastic lesions and carcinogenesis45. This was also confirmed in human pancreatic cells46,47. Furthermore, SMAD4, the main effector of the TGFB signalling pathway is also a direct target of Mir34a48–50. Additionally, IL6-JAK-STAT3, TNFA via NFKB and inflammation pathways are also enriched by GSEA and we show that ablation of Mir34a in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice led to an increase in TNFA and IL6 in pancreatic acini. Multiple studies using mouse models of pancreatic cancer demonstrate a strong relationship between Kras, NFKB, STAT3 and cytokine signalling which drives lesion formation and the development of PDAC51–57.

Our results are in agreement with previous studies showing that Mir34a downregulates TNFA and IL658. For instance, in vitro administration of Mir34a mimics to LPS treated macrophages decreases the expression of TNFA and IL6, and reduces NFKB activation. Here the mechanism shown is direct inhibition of Mir34a over either its target Notch1, which activates the inflammatory response in macrophages, or other genes that affect NFKB signalling; therefore, modulating LPS-induced macrophage inflammatory response58. Furthermore, in colorectal cancer Mir34a was shown to constrain carcinogenesis by directly inhibiting an IL-6R/STAT3/Mir34a feedback loop, and its ablation is required to induce IL6-mediated EMT and invasion37. Moreover, a couple of studies support that IL-6R is a direct target of Mir34a43,59,60. Therefore, many previous studies have reported similar results to ours in other organs and supports our observation that Mir34a ablation results in the upregulation of the inflammatory cytokines TNFA and IL6 in the pancreas. Interestingly, these two secreted pro-inflammatory cytokines are considered strong EMT inducers key for cancer progression61. However, in our study despite that an enrichment in EMT signature was found at early time points, it was not sufficient to result in significantly more metastasis in KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ mice, possibly due to the fact that at later stages of the disease KrasG12 mice also present a strong EMT signature or due to the faster tumour development.

In summary, this study shows that ablation of Mir34a results in a cell-autonomous inflammatory response marked by the increase in TNFA and IL6 expression in acinar cells, which is linked to an enhanced TGFB signalling in preneoplastic transformation that appears to accelerate KrasG12D-dependent pancreatic carcinogenesis. Overall, our results suggest that apart from its known tumor suppressor role, Mir34a also has an anti-inflammatory role in the pancreas by downregulating TNFA and IL6. This anti-inflammatory role may be important at the initiation stage of preneoplastic development, but further functional understanding of the underlying mechanisms is required in order to fully support this hypothesis. This capacity of Mir34a should also be taken into account when designing Mir34a targeted therapy for PDAC.

Methods

Mouse strains

Mir34afl/fl mice37 were generated by the Hermeking laboratory and we bred them to Ptf1a+/Cre 62 and Kras+/LSL-G12D 38 mice to generate Ptf1a+/Cre; Mir34afl/fl (called: Mir34aΔ/Δ) and Ptf1a+/Cre; Kras+/LSL-G12D; Mir34afl/fl (called: KrasG12D; Mir34aΔ/Δ). Co-housed wild type Mir34afl/fl and Ptf1a+/Cre; Kras+/LSL-G12D (called: KrasG12D) littermate mice were used as controls. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with German Federal Animal Protection Laws and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee from the Technical University of Munich (Germany), and from the Government of Bavaria AZ: (5.2-1-54-2532-46-2014).

Body and pancreatic weight analysis

Mice were sacrificed and immediately weighted in a scale. Subsequently, the whole pancreas was carefully excised without any adjacent tissue and directly weighed in a precision scale under sterile technique.

Primary cell isolation and culture

After sacrificing the mice, either acinar, ductal or tumour cells (from terminal mice) were directly isolated from the pancreas and cultured using the methods previously described63,64. For quantification of acinar explants transdifferentiation rate, acinar cell explants were counted in 6 to 33 high power fields per mouse using a 10X objective (approx. 3 areas per well of a 48 well plate). The phenotype was defined as acinar (cluster of acinar cells resembling a ball), duct-like (acinar cell clusters with a ductal structure emerging within the cluster) or ductal (ductal structure with a defined lumen), see Supplementary Fig. 4A.

Immunohistochemical staining

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described65. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Cleaved caspase 3 (1:200; Cell Signalling #9661), mouse anti-CD45 (1:20, BDPharmigen #550539), rabbit anti-CK19 (1:1000; Abcam #ab133496), goat anti-CPA1 (1:300, RD Systems #AF2765), mouse anti–Ki-67 (1:400; BDPharmigen #550609), mouse anti-MUC5AC (1:200; Cell Marque #292M-95), rabbit anti-p65 (C-20) (1:200, Santa Cruz #sc-372), rabbit anti-phospho-STAT3 (Y705) (1:100, Cell Signaling #9145).

Morphometric quantification

After staining, slides were scanned at 20x using a Leica AT2 scanner (Leica) and analysed with Aperio Image Scope program (Leica). Whole pancreatic area and remodelled tissue (areas of ADM and/or low/high grade PanIN lesions) were quantified in a blinded way; representative images were taken. For quantification of CK19 positive ADM and MUC5AC-positive PanIN lesions, 10 high power fields (HPF) were counted per whole pancreatic tissue slide and the average number of lesions per HPF was calculated. For quantification of Ki-67 and cleaved caspase 3, 50 ADM and PanIN lesions were randomly selected across the whole slide (no more than 10 lesions in the same area), positive cells (visualized by brown precipitate) were counted and the percentage was calculated. The total number of cells counted per HPF excluded: fatty, edema, or inflammatory tissue. Presence of microscopic carcinomas (only a few cancer cells) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma was determined by an experienced pathologist (K.S.). For the quantification of CD45 positive immune cells, 10 HPF were randomly selected across the whole pancreatic tissue slide in areas of normal tissue. Only positive immune cells were counted. For the quantification of NFKB and P-STAT3 positive nuclei the nuclear counting algorithm V9 from Image Scope was used with the following settings: threshold for cytoplasmic correction 230, upper limit of weak (1+) 217, moderate (2+) 200 and strong (3+) 188. 10 HPF were randomly selected across the whole pancreatic tissue section in areas of normal tissue. Only nuclei from normal acini were counted.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

After sacrificing the mice, a small piece of the pancreas was excised, stored in RNAlater (Qiagen) overnight at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C the next morning. RNA was homogenized with RA1 lysis buffer (Macherey-Nagel) and β-mercaptoethanol. Subsequently, RNA was isolated using the Maxwell 16 LEV simplyRNA Purification Kit (Promega) following manufacturer’s instructions. SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) was used for cDNA synthesis, according to manufacturer’s protocol. RT-PCR was performed as previously described65 using the SYBR Green master mix (Roche) on a Lightcycler480 system (Roche). Primers used are described in Table 1. Melting curve analysis was performed to ensure product quality and specificity. Expression levels of each transcript were normalized to the housekeeping gene XS13 (a constitutively expressed ribosomal protein with same levels in normal, cancerous, and inflamed human pancreas)66, using the ΔΔCt method. All RT-PCR experiments were performed with at least N = 3 individual biological samples per group.

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Mir34a | Pri-miR-34a_F | 5′-CTGTGCCCTCTTGCAAAAGG-3′ |

| Pri-miR-34a_R | 5′-GGACATTCAGGTGAGGGTCTTG-3′ | |

| Mir34bc | Pri-miR-34bc_F | 5′-GGCAGGAAGGCTCCAGATG-3′ |

| Pri-miR-34bc_R | 5′-CCTCACTGTTCATATGCCCATTC-3′ | |

| Amylase | Amy2a_F | 5′-TGGTCAATGGTCAGCCTTTTTC-3′ |

| Amy2a_R | 5′-CACAGTATGTGCCAGCAGGAAG-3′ | |

| CK19 | Krt19_F | 5′-ACCCTCCCGAGATTACAACC-3′ |

| Krt19_R | 5′-CAAGGCGTGTTCTGTCTCAA-3′ | |

| SOX9 | SOX9_F | 5′-CCACGTGTGGATGTCGAAG-3′ |

| SOX9_R | 5′-CTCAGCTGCTCCGTCTTGAT-3′ | |

| Tnfa | Tnfa_F | 5′-TGCCTATGTCTCAGCCTCTTC-3′ |

| Tnfa_R | 5′-GAGGCCATTTGGGAACTTCT-3′ | |

| Nfkb | Nfkb_F | 5′-GGAGGCATGTTCGGTAGTGG-3′ |

| Nfkb_R | 5′-CCCTGCGTTGGATTTCGTG-3′ | |

| Il6 | Il6_F | 5′-GCTACCAAACTGGATATAATCAGGA-3′ |

| Il6_R | 5′-CCAGGTAGCTATGGTACTCCAGAA -3′ | |

| Nfkbia | Nfkbia_F | 5′-TGAAGGACGAGGAGTACGAGC-3′ |

| Nfkbia_R | 5′-TCTTCGTGGATGATTGCCAAG-3′ | |

| XS13 | XS13_F | 5′-TGGGCAAGAACACCATGATG-3′ |

| XS13_R | 5′-AGTTTCTCCAGAGCTGGGTTGT-3′ |

RNA-sequencing

Library preparation for bulk 3′-sequencing of poly(A)-RNA was done as described previously67. Briefly, barcoded cDNA of each sample was generated with a Maxima RT polymerase (Thermo Fisher) using oligo-dT primer containing barcodes, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and an adapter. 5′ ends of the cDNAs were extended by a template switch oligo (TSO) and after pooling of all samples full-length cDNA was amplified with primers binding to the TSO-site and the adapter. cDNA was tagmented with the Nextera XT kit (Illumina) and 3′-end-fragments finally amplified using primers with Illumina P5 and P7 overhangs. The library was sequenced on a NextSeq. 500 (Illumina) with 16 cycles for the barcodes and UMIs in read1 and 65 cycles for the cDNA in read2.

RNAseq analysis

Gencode gene annotations version M18 and the mouse reference genome major release GRCm38 were derived from the Gencode homepage (https://www.gencodegenes.org/). Dropseq tools v1.1268 was used for mapping the raw sequencing data to the reference genome. The resulting UMI filtered countmatrix was imported into R v3.4.4. Prior differential expression analysis with DESeq. 2 1.18.169, dispersion of the data was estimated with a parametric fit. The Wald test was used for determining differentially regulated genes between experimental conditions and shrunken log2 fold changes were calculated afterwards, with setting the type argument of the lfcShrink function to ‘normal’.

A gene was determined to be differentially regulated if the adjusted p-value was below 0.05. Gene set enrichment analysis was conducted with the preranked GSEA method70 within the MSigDB Hallmark database. Genes were ranked according to their respective log2 fold change. A pathway was considered to be significantly associated with an experimental condition at an alpha level of 0.05 (for NES and FDR values see Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism6 (GraphPad Software Inc). Unless otherwise stated, the Mann-Whitney Test for non-normal distributed unpaired data was used for inter-group comparison. For Fischer’s test OR (95% CI) was used. Kaplan–Meier curve was calculated using the survival time for each mouse from the littermate groups. The log-rank test was used to address significant differences between the groups. For RT-PCR data, Log2 values were used for conducting the t-test. Welch’s t-test was used when samples followed a Gaussian distribution but they had different standard deviations. For all statistical analysis, differences with a p-value lower than 0.05 were considered significant, and the following scale was applied: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data are presented as mean values ± SEM, unless otherwise stated.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Annett Dannemann, Mathilde Neuhofer, Lina Staufer, Olga Seelbach and Katharina Schulte for expert technical assistance. As well as, Jiang Longchang, Matjaz Rokavec and Gülfem Öner for scientific input. This project was supported by the Emmy Noether Program (FI 1719/2-1) to GVF and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project-ID 329628492 – SFB 1321 (S02) to KS. J.T.S. is supported by the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), the German Cancer Aid (grant no. 70112505; PIPAC consortium) and the DFG (KFO337/SI 1549/3-1).

Author contributions

Initiation and concept of study: J.S., H.H.; design experiments and conceived experiments: A.H.S. and G.F. performed experiments: A.H.S., C.L.M., S.Z., J.D. and R.Ö. analysed data: A.H.S., C.L.M., T.E. and K.S. wrote manuscript: A.H.S. edited manuscript: A.H.S., C.L.M, R.R., R.S., H. H., J.S. and G.F.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-66561-1.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu H, Li T, Du Y, Li M. Pancreatic cancer: challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. 2018;16:214. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1215-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almoguera C, et al. Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c-K-ras genes. Cell. 1988;53:549–554. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waters, A. M. & Der, C. J. KRAS: The Critical Driver and Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med8, 10.1101/cshperspect.a031435 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Collins MA, et al. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:639–653. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hruban RH, Goggins M, Parsons J, Kern SE. Progression model for pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2969–2972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhardwaj A, Arora S, Prajapati VK, Singh S, Singh AP. Cancer “stemness”- regulating microRNAs: role, mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14:1175–1184. doi: 10.2174/13894501113149990190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava SK, et al. MicroRNAs as potential clinical biomarkers: emerging approaches for their detection. Biotech Histochem. 2013;88:373–387. doi: 10.3109/10520295.2012.730153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivastava SK, et al. MicroRNAs in pancreatic malignancy: progress and promises. Cancer Lett. 2014;347:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misso G, et al. Mir-34: a new weapon against cancer? Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2014;3:e194. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rokavec M, Li H, Jiang L, Hermeking H. The p53/miR-34 axis in development and disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014;6:214–230. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mju003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermeking H. MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:613–626. doi: 10.1038/nrc3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang Y, Ridzon D, Wong L, Chen C. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal human tissues. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bommer GT, et al. p53-mediated activation of miRNA34 candidate tumor-suppressor genes. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1298–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:193–199. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lodygin D, et al. Inactivation of miR-34a by aberrant CpG methylation in multiple types of cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2591–2600. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He L, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007;447:1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raver-Shapira N, et al. Transcriptional activation of miR-34a contributes to p53-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarasov V, et al. Differential regulation of microRNAs by p53 revealed by massively parallel sequencing: miR-34a is a p53 target that induces apoptosis and G1-arrest. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1586–1593. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole KA, et al. A functional screen identifies miR-34a as a candidate neuroblastoma tumor suppressor gene. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:735–742. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagchi A, Mills AA. The quest for the 1p36 tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2551–2556. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogt M, et al. Frequent concomitant inactivation of miR-34a and miR-34b/c by CpG methylation in colorectal, pancreatic, mammary, ovarian, urothelial, and renal cell carcinomas and soft tissue sarcomas. Virchows Arch. 2011;458:313–322. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-1030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attiyeh EF, et al. Chromosome 1p and 11q deletions and outcome in neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2243–2253. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li XJ, Ren ZJ, Tang JH. MicroRNA-34a: a potential therapeutic target in human cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1327. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slabakova E, Culig Z, Remsik J, Soucek K. Alternative mechanisms of miR-34a regulation in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3100. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang TC, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia J, et al. Genistein inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis through up-regulation of miR-34a in pancreatic cancer cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:1750–1756. doi: 10.2174/138945012804545597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ji Q, et al. MicroRNA miR-34 inhibits human pancreatic cancer tumor-initiating cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Y, Tang Y, Cheng YS. miR-34a inhibits pancreatic cancer progression through Snail1-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the Notch signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:38232. doi: 10.1038/srep38232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long LM, et al. The Clinical Significance of miR-34a in Pancreatic Ductal Carcinoma and Associated Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Pathobiology. 2017;84:38–48. doi: 10.1159/000447302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikeda Y, Tanji E, Makino N, Kawata S, Furukawa T. MicroRNAs associated with mitogen-activated protein kinase in human pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:259–269. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alemar B, et al. miRNA-21 and miRNA-34a Are Potential Minimally Invasive Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2016;45:84–92. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamieson NB, et al. MicroRNA molecular profiles associated with diagnosis, clinicopathologic criteria, and overall survival in patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:534–545. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohuchida K, et al. MicroRNA expression as a predictive marker for gemcitabine response after surgical resection of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2381–2387. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1602-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bader AG. miR-34 - a microRNA replacement therapy is headed to the clinic. Front Genet. 2012;3:120. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibori H, et al. Amphiphilic nanocarrier-induced modulation of PLK1 and miR-34a leads to improved therapeutic response in pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9:16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rokavec M, et al. IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop promotes EMT-mediated colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1853–1867. doi: 10.1172/JCI73531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hingorani SR, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00309-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo S, Fesler A, Wang H, Ju J. microRNA based prognostic biomarkers in pancreatic Cancer. Biomark Res. 2018;6:18. doi: 10.1186/s40364-018-0131-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slotwinski R, Lech G, Slotwinska SM. MicroRNAs in pancreatic cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2018;43:314–324. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2018.80051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren L, Yu Y. The role of miRNAs in the diagnosis, chemoresistance, and prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:179–187. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S154226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kitajima S, Thummalapalli R, Barbie DA. Inflammation as a driver and vulnerability of KRAS mediated oncogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;58:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oner MG, et al. Combined Inactivation of TP53 and MIR34A Promotes Colorectal Cancer Development and Progression in Mice Via Increasing Levels of IL6R and PAI1. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1868–1882. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paladini L, et al. Targeting microRNAs as key modulators of tumor immune response. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:103. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0375-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chuvin N, et al. Acinar-to-Ductal Metaplasia Induced by Transforming Growth Factor Beta Facilitates KRAS(G12D)-driven Pancreatic Tumorigenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;4:263–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J, et al. TGF-beta1 promotes acinar to ductal metaplasia of human pancreatic acinar cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30904. doi: 10.1038/srep30904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akanuma N, et al. Paracrine Secretion of Transforming Growth Factor beta by Ductal Cells Promotes Acinar-to-Ductal Metaplasia in Cultured Human Exocrine Pancreas Tissues. Pancreas. 2017;46:1202–1207. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qiao P, et al. microRNA-34a inhibits epithelial mesenchymal transition in human cholangiocarcinoma by targeting Smad4 through transforming growth factor-beta/Smad pathway. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:469. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1359-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang G, et al. MiRNA-34a reversed TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition via suppression of SMAD4 in NPC cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Genovese G, et al. microRNA regulatory network inference identifies miR-34a as a novel regulator of TGF-beta signaling in glioblastoma. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:736–749. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liou GY, et al. Macrophage-secreted cytokines drive pancreatic acinar-to-ductal metaplasia through NF-kappaB and MMPs. J Cell Biol. 2013;202:563–577. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siveke JT, Crawford HC. KRAS above and beyond - EGFR in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1262–1263. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maier HJ, et al. Requirement of NEMO/IKKgamma for effective expansion of KRAS-induced precancerous lesions in the pancreas. Oncogene. 2013;32:2690–2695. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ling J, et al. KrasG12D-induced IKK2/beta/NF-kappaB activation by IL-1alpha and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lesina M, et al. Stat3/Socs3 activation by IL-6 transsignaling promotes progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fukuda A, et al. Stat3 and MMP7 contribute to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma initiation and progression. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:441–455. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corcoran RB, et al. STAT3 plays a critical role in KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5020–5029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang P, et al. MiR-34a inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response through targeting Notch1 in murine macrophages. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li H, Rokavec M, Hermeking H. Soluble IL6R represents a miR-34a target: potential implications for the recently identified IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feed-back loop. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14026–14032. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weng YS, et al. MCT-1/miR-34a/IL-6/IL-6R signaling axis promotes EMT progression, cancer stemness and M2 macrophage polarization in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0988-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gao F, Liang B, Reddy ST, Farias-Eisner R, Su X. Role of inflammation-associated microenvironment in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2014;14:30–45. doi: 10.2174/15680096113136660107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakhai H, et al. Ptf1a is essential for the differentiation of GABAergic and glycinergic amacrine cells and horizontal cells in the mouse retina. Development. 2007;134:1151–1160. doi: 10.1242/dev.02781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reichert M, Rhim AD, Rustgi AK. Culturing primary mouse pancreatic ductal cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2015;2015:558–561. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot078279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lubeseder-Martellato, C. Isolation, Culture and Differentiation of Primary Acinar Epithelial Explants from Adult Murine Pancreas. BioProtocol3 (2013).

- 65.Jochheim LS, et al. The neuropeptide receptor subunit RAMP1 constrains the innate immune response during acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreatology. 2019;19:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2019.05.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gress TM, et al. A pancreatic cancer-specific expression profile. Oncogene. 1996;13:1819–1830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knier B, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells control B cell accumulation in the central nervous system during autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:1341–1351. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0237-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Macosko EZ, et al. Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell. 2015;161:1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.