Abstract

Radiogenomics or imaging genomics is a novel omics strategy of associating imaging data with genetic information, which has the potential to advance personalized medicine. Imaging features extracted from PET or PET/CT enable assessment of in vivo functional and physiological activity and provide comprehensive tumor information non-invasively. However, PET features are considered secondary to features on conventional imaging, and there has not yet been a review of the radiogenomic approach using PET features. This review article summarizes the current state of PET-based radiogenomic research for cancer, which discusses some of its limitations and directions for future study.

Keywords: Radiogenomics, Positron emission tomography (PET), Oncology

Introduction

Radiogenomics, also called imaging genomics, is a rapidly evolving field of imaging science that seeks to uncover associations between image phenotypes and genomic information [1–4]. Image phenotypes or signatures are obtained by a radiomic approach, which is the extraction of qualitative or quantitative image features with or without computer algorithms [5]. Genomic information is much easier to use in clinical practice than 10 years ago, because of development about the advancements in high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies [6].

Radiogenomics is the cross-disciplinary research bridging imaging and genomics. The term radiogenomics has been used in different fields of research to refer to investigations of the underlying genetic causes of individual differences on radiation response, also called radiation genomics [7, 8]. We excluded radiation genomic studies and studies that examined the associations between imaging features and patient response to radiation therapy in this review.

In the era of personalized medicine that has focused on molecular characterization of cancer in individual patients, merging radiomic data and genomic data has great potential [9, 10]. Some genetic tests have been integrated in clinical practice of oncology since information about genetic alterations can enable physicians to select appropriate management strategies [11]. Tumor diagnosis is changing from the traditional histology-based approaches to gene-based stratification. However, routine application of genomic-based cancer characterization for personalized treatment is limited. Incorporating genomics into routine clinical practice is still a challenge because of the need for tissue samples collected via invasive procedures, high cost, relatively long turnaround time, and technical complexity [2, 12]. Even more importantly, the genetic information obtained from samples collected through biopsy or surgery may not accurately represent the whole genomic characteristics of lesions. Tumors have genetic diversity and heterogeneity not only among different masses but also within a single mass [11–14]. Intra- and inter-tumoral genetic heterogeneity eventually drives treatment failure and disease progression [14–16]. In addition, it is not feasible to perform multiple and sequential biopsies to identify genetic alterations within a single tumor lesion throughout the disease course.

Although histological classification of biopsied or surgically resected samples is the gold standard for oncologic diagnosis, in vivo tumor characterization by imaging is advantageous over invasive methods. Imaging techniques are non-invasive and can afford a more overall view of the entire tumor than that of biopsy samples alone. Furthermore, it can be performed repeatedly to evaluate treatment response and to monitor tumor progression in routine clinical practice [2]. The association between imaging features and gene expression enables valuable insight into which imaging features can be used to predict gene expression in tumors [2]. Associated features could be incorporated into multiparametric models for predicting mutations in particular genes or genetic pathways [17]. The radiogenomic approach primarily aims to identify imaging biomarkers for non-invasive genotyping. Bridging imaging and genomics may be useful in unraveling unknown molecular mechanisms underlying cancer progression.

Medical scans such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) (or PET/CT) can be converted into quantitative data and incorporated into radiogenomic research. To date, radiogenomic approaches have focused on CT or MRI scans. However, PET or PET/CT has the advantage of allowing assessment of in vivo functional and physiological activity with higher accuracy than anatomical imaging modalities. Associations between image features extracted from 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT and genetic alterations have been investigated [18–22]. PET-based radiomic features have potential in predicting genetic alterations and could complement the radiogenomic approach using anatomical imaging modalities and improve the capability of multiparametric prediction models [9]. Although there have been many reviews of radiogenomic articles, PET-based radiogenomic research has only been briefly addressed as ancillary to CT- or MRI-based studies.

In this review, we discuss radiogenomic research based on PET imaging from the perspective of nuclear medicine. The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive view of the current state and further directions of PET-based radiogenomics. We assessed oncology-wide radiogenomic associations in previous studies, reviewed limitations of the radiogenomic approach, and searched for feasible solutions to these limitations.

Current State of PET-Based Radiogenomic Research

Study Search

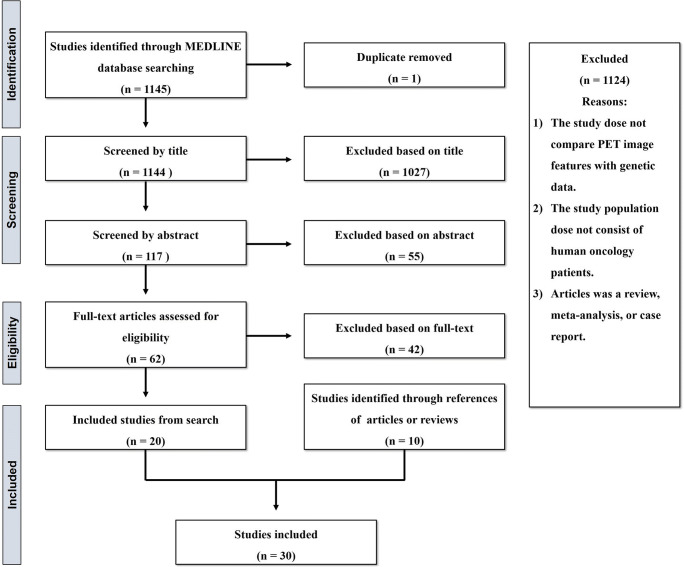

We searched the electronic databases for original research published between 2000 and October 2019 that investigated the associations between PET imaging features and genomic data by entering a specific combination of search terms and conditions in MEDLINE. Details of the search strategy and process are provided in Fig. 1. Briefly, search terms included variations of different nuclear medicine imaging modalities such as “PET” and “tomography,” oncologic terms such as “tumor,” “cancer,” “carcinoma,” and radiogenomic terms such as “genetics,” “genomics,” “feature,” “index,” “radiogeno,” “radiomi,” and “imaging genomics.” We only included original studies with human subjects that were written in English. In addition, we identified reviews that contained the word radiogenomic or imaging genomics separately and reviewed all references to identify PET-based radiogenomic studies that were not included in our initial search. We excluded studies that correlated imaging features with biomarkers measured by immunohistochemistry or fluorescent in situ hybridization. For example, we did not include studies that correlated image features with molecular subtypes in patients with breast cancer.

Fig. 1.

Details of the search strategy and process

Finally, we included a total of 30 studies for this review (Fig. 1). Among them, there were studies that associated image features with a few specific genes. Given that omics are aimed primarily at the collective characterization and quantification of biological molecules [23], an association of one or several genes with image features was insufficient to accept as “real radiogenomics.” Therefore, similar to a previous review [2], we grouped them under the category “semi-radiogenomic studies.” As a result, 7 studies were categorized as radiogenomic (Table 1) and 23 studies as semi-radiogenomic (Table 2) studies.

Table 1.

Published PET-based radiogenomic studies (n = 7)

| Authors | Year | Cancer | Study design | Data source | Number of subjects | Number of PET features | Feature type | Genome | Genomic analysis | Individual gene vs gene cluster | Pathway analysis | Validation dataset | Imaging modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osborne et al. [43] | 2010 | Breast | Pro | Single | 20 | 1 | I | RNA | Microarray | Both | Yes | No | PET/CT |

| Palaskas et al. [44] | 2011 | Breast | N/A | Single | 18 | 1 | I | RNA | Microarray | Cluster | Yes | Yes | PET/CT |

| Gevaert et al. [20] | 2012 | Lung (NSCLC) | Retro | Single | 26 | 1 | I | RNA | Microarray | Cluster | Yes | Yes | PET/CT, CT |

| Nair et al. [19] | 2012 | Lung (NSCLC) | Retro | Multi | 25 | 14 | I, H, V | RNA | Microarray | Both | Yes | No | PET/CT |

| Yamamoto et al. [22] | 2016 | Lung (NSCLC) | Retro | Public* | 26 | 1 | I | RNA | PCR | Individual | No | Yes† | PET/CT |

| Vlachavas et al. [24] | 2019 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 30 | 8 | I, K | RNA | Microarray | Individual | No | No | PET |

| Crespo-Jara et al. [21] | 2018 | Metastatic | Retro | Single | 84 | 7 | I, V | RNA | Microarray | Both | Yes | Yes | PET/CT |

*NSCLC Radiogenomics dataset that contained 18F-FDG PET and RNA expression profile dataset: Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE28827) & https://wiki.cancerimagingarchive.net/display/DOI/NSCLC+Radiogenomics%3A+Initial+Stanford+Study+of+26+Cases

†Internal validation

Table 2.

Published PET-based semi-radiogenomic studies (n = 23)

| Authors | Year | Cancer | Study design | Data source | Number of subjects | Number of PET features | Feature type | Genome | Genomic analysis | Individual gene vs gene cluster | Pathway analysis | Validation dataset | Imaging modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al. [33] | 2010 | Lung (NSCLC) | Pro | Single | 154 | 1 | I | DNA | SNP assay | Individual | Yes | No | PET/CT |

| Yoon et al. [32] | 2015 | Lung (ADC) | Retro | Single | 539 | 1 | I | DNA, RNA | Microarray | Individual | No | Yes* | CT, PET/CT |

| Guan et al. [29] | 2016 | Lung (NSCLC) | Retro | Single | 85 | 1 | I | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Cho et al. [30] | 2016 | Lung (NSCLC) | Retro | Single | 58 | 2 | I, V | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Yip et al. [28] | 2017 | Lung (NSCLC) | Retro | Multi | 348 | 68 | I, V, H, T | DNA | PCR, PROFILE Oncomap | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Moon et al. [18] | 2019 | Lung | Retro | Single | 176 | 106 | I, V, H, T | DNA | NGS | N/A | No | No | PET/CT |

| Jiang et al. [27] | 2019 | Lung (NSCLC) | Retro | Single | 80 | 256 | I, V, H, T | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Kawada et al. [36] | 2012 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 51 | 2 | I, R | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET |

| Izuishi et al. [42] | 2012 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 37 | 1 | I | RNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET |

| Miles et al. [38] | 2014 | Colorectal | Pros | Single | 33 | 3 | I | DNA | Pyrosequencing | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Chen et al. [41] | 2015 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 103 | 4 | I, V | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Lee et al. [37] | 2016 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 179 | 4 | I, V | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Lovinfosse et al. [35] | 2016 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 151 | 20 | I, H, T | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Oner et al. [40] | 2017 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 55 | 4 | I, V | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Chen et al. [39] | 2019 | Colorectal | Retro | Single | 74 | 65 | I, H, V, T | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Choi et al. [48] | 2017 | Thyroid (PTC) | Retro | Single | 106 | 1 | I | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Chang et al. [49] | 2018 | Thyroid (PTC) | Retro | Single | 108 | 1 | I | DNA | Pyrosequencing | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Nagarajah et al. [47] | 2015 | Thyroid (PTC) | Retro | Single | 82 | 1 | I | NA | NGS/ Sequenom | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Metellus et al. [53] | 2011 | Brain (Glioma) | Retro | Single | 33 | 1 | R | DNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Lanic et al. [54] | 2012 | DLBCL | Retro | Single | 45 | 1 | I | RNA | PCR | Cluster | No | No | PET |

| Kesch et al. [55] | 2018 | Prostate | Pro | Single | 5 | 1 | I | GWMA | CNA | No | No | MRI, PSMA PET/CT | |

| Magometschnigg et al. [45] | 2019 | Breast | Retro | Single | 67 | 1 | I | DNA | Pyrosequencing | Individual | No | No | PET/CT |

| Liu et al. [51] | 2016 | Neuroblastoma | Retro | Single | 42 | 2 | I | RNA | PCR | Individual | No | No | FDG, FDOPA PET/CT |

*Internal validation

I, intensity feature; R, uptake ratio; H, SUV histogram feature; V, volumetric feature; K, kinetic feature; NGS, next-generation sequencing; GWMA, genome-wide methylation analysis; CNA, chromosomal copy number alterations

Study Designs and Characteristics

Five of the seven radiogenomic studies (71.4%) were retrospective. One study used multi-institutional data, another study used public data, and the other five studies were conducted at a single institution. The number of patients ranged from 18 to 84, with a median of 26 patients. Five (5/7, 71.4%) studies adopted a validation dataset for verifying the association between image features and genetic alteration identified in the initial dataset. Among them, one study used an internal validation dataset. Different types of cancers were studied, i.e., lung cancer (3/7, 42.8%), breast cancer (2/7, 28.5%), colorectal cancer (CRC) (1/7, 14.3%), and metastatic tumors (18 different types) (1/7, 14.3%). The studies used different types of imaging modalities including FDG PET/CT (5/7, 71.4%), FDG PET (1/7, 14.3%), and FDG PET/CT and CT (1/7, 14.3%).

Twenty of the twenty-three semi-radiogenomic studies (86.9%) were retrospective. One study used multi-institutional data, and the remaining 22 studies were conducted at a single institution. The number of patients ranged from 5 to 539, with a median of 80 patients. One (1/23, 4.3%) study used validation data. Eight types of cancers were studied, i.e., CRC (8/23, 34.8%), lung cancer (7/23, 30.4%), papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) (3/23, 13.0%), breast cancer (1/23, 4.3%), glioma (1/23, 4.3%), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (1/23, 4.3%), prostate cancer (1/23, 4.3%), and neuroblastoma (1/23, 4.3%). The imaging modalities used included FDG PET/CT (16/23, 69.5%), FDG PET (3/23, 13.0%), FDG PET/CT and CT (1/23, 4.3%), FDG PET/CT and 3,4-dihydroxy-6-(18)F-fluoro-l-phenylalanine (FDOPA) PET/CT (1/23, 4.3%), and MRI and gallium 68-labeled prostate-specific membrane antigen (Ga-PSMA) PET/CT (1/23, 4.3%).

Imaging Features

Seventeen of the thirty studies (56.6%) performed PET image acquisition with one scanner, and twelve (12/30, 40.0%) studies used two or more scanners. One study did not provide any information about the scanner. Sixteen (16/30, 53.3%) studies extracted PET image features from volume of interest (VOI), and 7 (7/30, 23.3%) studies used region of interest (ROI). Seven studies did not provide detailed information regarding target lesion segmentation. VOI or ROI were automatically or semi-automatically drawn in 14 studies (14/30, 46.6%), and they were manually drawn in 9 studies (9/30, 30.0%). The number of imaging features extracted ranged from 1 to 256 with a median of 2. Imaging features included intensity features such as SUVmax, volumetric features such as MTV and TLG, SUV histogram–based features, uptake ratio, texture features, and kinetic parameters extracted for compartment model (one study [24] performed dynamic PET study). SUVmax was the most common PET image feature extracted (29 studies (29/30, 96.6%)). Sixteen studies (16/30, 53.3%) used only intensity features, five studies (5/30, 16.7%) used intensity and volumetric features, and five studies (5/30, 16.7%) used intensity, volumetric, histogram, and texture features. The PET image features used in the remaining five studies were intensity and uptake ratio (n = 1, 3.3%); intensity and kinetic features (n = 1, 3.3%); uptake ratio (n = 1, 3.3%); intensity, SUV histogram, and volumetric features (n = 1, 3.3%).

Genomic Data

Seventeen (17/30, 56.6%) studies extracted data from DNA, 10 studies (10/30, 33.3%) extracted data from RNA, 1 study (1/30, 3.3%) used data from RNA and DNA, and 1 study (1/30, 3.3%) used genome-wide methylation analysis data. One study did not provide detailed information about the genomic data source. Eleven of the seventeen studies that used DNA used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis, three studies used pyrosequencing, one study used next-generation sequencing (NGS), one study used single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) assay, and one study used mass spectrometry genotyping and PCR. Among the ten studies that used RNA, six used microarray and four used PCR. The study with DNA and RNA used microarray analysis.

Three (3/30, 10.0%) studies classified individual gene expression into gene clusters to associate with image features; 22 (22/30, 73.3%) studies directly associated individual genes with imaging features; and 3 (3/30, 10.0%) studies used both approaches. One study used genetic heterogeneity and mutation burden index, and one study used chromosomal copy number alteration. Six (6/30, 20.0%) studies used pathway analysis in the initial gene clustering or in the final analysis for identifying significant genomic markers.

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the most actively studied in PET-based radiogenomic research. Ten of the thirty total studies included in this review focused on lung cancer. Three of these studies with microarray data were classified as “radiogenomic” research, and the remaining studies were classified as “semi-radiogenomic” research.

The three “radiogenomic” studies used a similar research approach. Gevaert et al. demonstrated a radiogenomic strategy to identify prognostic imaging biomarkers by leveraging public gene expression microarray data [20]. They extracted CT image features and SUVmax from CT and FDG PET/CT, and made a radiogenomic map by correlating the imaging features to metagenes, which are aggregated patterns of gene expression. By using the radiogenomic correlation map as an intermediate, they linked imaging features expressed in terms of metagenes to the public gene expression dataset where survival outcomes are available [20]. Their approach was able to leverage imperfect datasets, imaging, and a gene expression dataset without survival outcomes to draw new conclusions with imaging biomarkers for prognosis [20]. Nair et al. used a similar strategy linking a radiogenomic association map to public gene expression data with survival outcomes. They demonstrated that four genes (LY6E, RNF149, MCM6, FAP) associated with FDG uptake were also associated with survival. They performed SAM analysis to define genes significantly associated with FDG uptake metrics. The array data was filtered based on a significant detection call in at least 60% of the samples and log transformed using quantile normalization to account for array variation [19]. Notably, the prognostic metagene signatures associated with multivariate FDG uptake features were highly associated with survival outcome in the external and validation cohorts [19]. Yamamoto et al. demonstrated that non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with high normalized SUVmax may be associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which is implicated in metastasis and chemoresistance [22]. They used an integrative radiogenomic approach by linking to an external public dataset, similar to the strategy described above.

The research focus in the semi-radiogenomic studies was on identifying correlations between image features and clinically relevant mutations. The most researched genetic mutation in NSCLC was epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and most commonly used methods for detecting EGFR mutations was PCR. The correlation of imaging features with EGFR is of interest because the genetic mutation status of EGFR plays a crucial role in treatment selection for NSCLC [25]. Receptor blockers or tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are treatment options in patients with NSCLC with an activating EGFR mutation [26]. Previous studies demonstrated that PET features were significantly associated with EGFR mutation status [27–30]. A model using 35 selected features significantly predicted EGFR mutation status (area under the ROC curve = 0.953) [27]. Yip et al. demonstrated that PET-based radiomic features were significantly associated with EGFR mutation status, while none of the features was associated with KRAS mutation status [28]. Yoon et al. investigated the predictive value of PET features for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangements, which is one of the major therapeutic targets in a molecularly defined subset of NSCLC [31]. ALK fusion–positive tumors had significantly different SUVmax than c-ros oncogene 1 (ROS)/rearranged during transfection (RET) fusion–positive tumors [32]. The polymorphisms in the glucose transporter gene were associated with SUVmax in combination with hypoxia-related genes in patients with squamous cell carcinoma [33]. One study investigated the correlations between PET radiomics and genetic properties such as heterogeneity and tumor mutation burden [18], and revealed that surface SUVentropy is significantly correlated with genetic heterogeneity in small cell lung cancer.

Colorectal Cancer

Nine searched studies focused on CRC. One study was “radiogenomic” research and the remaining eight studies were “semi-radiogenomic” research. In the radiogenomic study that used microarray data and PET data feature sets, Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to select the most correlated genes, from the initial list of the 911 common genes, with any of the PET variables. A composite signature was derived using seven genes and five PET variables, and evaluated for its discrimination performance between primary CRC and adjacent normal mucosa [24]. This radiogenomic signature had superior classification accuracy [24].

As in lung cancer, semi-radiogenomic studies of CRC tested PET imaging features to predict clinically relevant gene mutations. Anti-EGFR therapy is an important treatment option for advanced CRC, and an activating Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutation is considered indicative of resistance to anti-EGFR therapy [34]. Therefore, the presence of KRAS mutation serves as a predictive biomarker in some CRC patients [34]. In the semi-radiogenomic studies, the most commonly used methods for detecting KRAS mutations was PCR. Although PET-based radiomic markers have been tested for predicting KRAS mutation, the results were inconsistent. SUV intensity features such as SUVmax [35–38], SUV histogram features [35], and volumetric features [39] were significantly associated with KRAS mutation in some studies. On the other hand, other studies reported that SUVmax is not indicative of KRAS mutational status [40, 41]. SUVmax was also tested in correlation analysis with expression of other genes [42], and was significantly correlated with hypoxia-inducible factor alpha (HIF1α) expression.

Breast Cancer

Among the three studies of breast cancer included in this review, two used genome-wide microarray data and one used individual gene mutation data. Molecular subtyping of breast cancer based on expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor markers (HER2) has direct prognostic and therapeutic implications in patient management [43]. As in lung cancer and CRC, studies in breast cancer focused on identifying the correlation between PET image features and status of clinically relevant mutations. Osborne et al. found an association between ER status and increased glucose uptake presented as SUV [43]. ER-negative tumors had significantly higher SUVmax than ER-positive tumors. However, there was no significant association between SUV and PR status or HER2 status. Furthermore, they established a preliminary radiogenomic gene set whose expression mostly correlated with ER status and SUV. They screened microarray data to find genes associated with increased SUV and compared these genes with those of a previously validated ER status molecular phenotype to identify significantly overlapping genes. Palaskas et al. identified genetic pathways associated with SUV in breast cancer, which were the coordinately upregulated multiple metabolic pathways [44]. They showed that these pathways could serve as an “FDG signature” which was closely linked to the “basal-like” intrinsic breast cancer subtype and activation of the MYC oncogene [44]. A recent study of individual mutational analysis investigated the association of PIK3CA mutational status, a novel therapeutic target, with SUVmax in invasive breast cancer [45]. No significant correlation between SUVmax and PIK3CA gene mutation was found in that study.

Other Malignancies

In PTC, the BRAF V600E gene mutation is an important prognostic factor for more rapid cancer growth and a higher death rate [46]. An association between SUVmax and BRAF V600E mutation has been demonstrated with consistent results [47–49]. MYCN amplification is a well-known genetic marker for poor prognosis in patients with neuroblastoma [50]. Liu et al. investigated the utility of FDG PET/CT and FDOPA PET/CT in determining the prognosis of neuroblastoma and reported that SUVmax of FDG and FDOPA PET had a significant association with MYCN amplification [51]. Gliomas with mutated IDH1 and IDH2 have better prognosis than those with wild-type IDH [52]. IDH mutation status has no significant association with FDG PET features in World Health Organization (WHO) II and III gliomas [53]. Lanic et al. assessed the relationship between molecular subclassification of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) by gene expression profile and PET features [54]. The expression of genes encoding glucose transporters from SLC2A1 to SLC2A5 was assessed and correlated with baseline SUVmax. Among these genes, SLC2A3 appeared to be the most highly expressed [54]. Kesch et al. assessed chromosomal copy number alterations (CNAs), a genetic marker of tumor aggressiveness, and MRI and 68Ga-PSMA-11-PET/CT features in prostate cancer [55]. Radiogenomic analysis was performed and CNAs were directly correlated to imaging features. There was a strong relationship between the radiologic and genomic index lesions, which suggests that imaging features can be used to identify the genomically most aggressive region within the prostate [55]. Crespo-Jara et al. built the universal genomic signature which could predict the increased FDG uptake in various metastatic tumors through a radiogenomic approach [21].

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Study Design, Sample Size, and Validation

There are few studies that used large-scale genome data. Seven of the thirty studies that we identified (7/30, 23.3%) were classified as real radiogenomic studies in the sense that they used genome-wide gene expression data. Most of the remaining studies tested the association between one or several clinically known genes and PET imaging markers, and we classified these as semi-radiogenomic studies. The semi-radiogenomic approach may be an efficient method to identify clinically relevant imaging-to-genomics relationships. However, it may undermine the unknown potential radiogenomic signatures. Given that the primary goal of radiogenomic analyses is to uncover the association between image phenotypes and genomic information, it would be advantageous to include as many indicators as possible. Nonetheless, radiogenomic research with whole genome data has the limitation of dimensionality [25], which arises when analyzing high-dimensional data, often with more than hundreds of dimensions, that does not occur in low-dimensional settings [56]. As the number of data variables grows, the amount of data needed to generalize accurately grows exponentially [25, 56, 57]. Since in reality it is almost impossible to collect this many samples, real radiogenomic research needs to reduce the dimensionality of genomic data. A common solution for the dimensionality problem is to group individual genes into clusters or metagenes before performing association analysis with imaging features [19, 20, 25]. The problem of dimensionality also occurs when analyzing imaging feature data. However, in general, the dimensionality of imaging data is lower than that of whole genome data. Previous radiogenomic studies with PET often used only a few imaging features, despite the many available features. The number of imaging features extracted ranged from 1 to 14 with a median of 1 in the radiogenomic studies (n = 7), which may further undermine the potential PET imaging-to-genomics association. On the other hand, extraction of fewer image features reduces dimensionality, which facilitates accurate data analysis.

Previous real radiogenomic studies are also limited by small sample size (range 18 to 84, median of 26 patients), which decreases the power of the study. Sample sizes that are too small increase the likelihood of a type II error skewing the results. Therefore, it is possible that some of the imaging-to-genomics relationship was not detected in previous studies. In addition, these studies also suffer from lack of a validation dataset verifying an identical statistical association. A validation dataset was used in four of the seven real radiogenomic studies (4/7, 57.1%) that we identified, and in only one of the twenty-three semi-radiogenomic studies (1/27, 3.7%). In fact, the difficulty in obtaining original cohorts of patients with both appropriate PET scans and adequate tissue samples for genomic analysis resulted in small sample sizes and lack of validation [2, 4]. Although large-scale imaging data are available, many of which have corresponding tumor tissue available for various molecular analyses [2], and genome-wide data are costly and technically complex [2, 12]. However, the cost of high-throughput molecular techniques including next-generation sequencing has been reduced to a fraction of what it was before [2, 58]. This technical advance has made it easier to obtain large amounts of genetic data. Genome imaging datasets can be collected retrospectively or prospectively in relatively large quantities. However, depending on the cancer type, PET/CT is not included in clinical practice at initial diagnosis where biopsies are routinely performed. Therefore, unlike CT, it is not practical to harvest large amounts of genome PET data to create a training set and validation set of sufficient size.

Use of publicly available resources is a feasible solution to overcome the scarcity of large datasets containing genomic data and PET images. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) is a rich dataset containing multidimensional genomic and clinical data for multiple types of adult cancers [59]. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) is another resource for image data accessible to the public and provides image files mainly in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format. TCIA is a large archive of medical images that includes cases corresponding to the patients in the TCGA [60]. This database can serve as powerful validation tool and facilitate the discovery of underlying relationships between cancer genomics and medical image features. However, a validation study with data from external resource requires addressing data availability issues, and the utility of TCIA for PET-based radiogenomic research is limited because of the small number of PET images comprising only a fraction of the total image data contained in the TCIA. More importantly, it is also limited by the fact that gene expression profiles cannot be matched to a specific location on imaging in some cases [2, 60].

In addition to TCIA, researchers can take advantage of independent datasets produced by other research groups. For example, Bakr et al. developed a unique radiogenomic dataset from a cohort of 211 patients with NSCLC that comprises CT and PET/CT images, semantic annotations of the tumors, and segmentation maps of tumors. They also matched the imaging data with results of genetic analysis and other clinical information [61].

Vulnerabilities of PET Radiomic Features

PET imaging features are significantly affected by several factors [18, 62–66]. One of the key factors influencing PET imaging feature extraction is the size of the target tumor lesion [63]. PET texture features that represent heterogeneity of the target lesion are particularly vulnerable to the size. Brooks et al. reported that, for texture analysis of FDG PET, it is appropriate to have a tumor volume of at least 45 cm3 [64]. They showed that the features are five times more sensitive to volume changes at small volumes below the proposed minimum than in those above it [64]. However, the larger study demonstrated that minimum metabolic tumor volume for analysis can be as small as 10 cm3 [67]. Image acquisition parameters and the reconstruction method are also important factors affecting the extraction of PET image features. Although there was a difference in degree, extracted FDG PET features vary depending on these conditions [18, 62, 65]. Galavis et al. demonstrated that 40 of 50 features (80.0%) had large variation above 30% in a study where PET scans were acquired in both 2D and 3D mode, and reconstructed using five different reconstruction methods [65]. The tumor segmentation method also affects PET image features [18, 66]. For example, a previous study reported that the coefficient of variance of 70 of 106 features obtained using nine different segmentation methods was above 0.1 [18]. Consequently, unless PET features are obtained under similar study conditions, these kinds of radiogenomic studies are difficult to compare with each other [13]. The repeatability of feature extraction is also influenced by imaging acquisition conditions [68, 69]. This means that even PET features obtained under the same conditions may differ. The vulnerability of PET radiomic features is the major obstacle to generalization of previously reported genome-image relationships.

To overcome the lack of reproducibility in high-throughput image analysis studies, researchers have been working towards standardization of imaging feature extraction [70–72]. Due to the high susceptibility to various factors, the use of PET quantitative features as clinical imaging biomarker requires a highly standardized imaging acquisition and preprocessing protocol. Various factors affecting image features were identified, and recommendations to take these factors into account were proposed in the literature [70]. Most previously published recommendations seem to be consistent [70]. Existing recommendations and guidelines are incorporated into the reference manual of the image biomarker standardization initiative (IBSI), which is an independent international collaboration for the standardization of radiomics. The IBSI provides benchmark datasets and benchmark values to verify image processing and image biomarker calculations, as well as consensus-based guidelines including imaging feature nomenclature, definitions, and reporting system, for high-throughput image analysis of CT, MRI, and PET [71, 72].

Another possible way to overcome the variability of PET image features is to use stable features. Although almost all PET features are affected by various factors, there are the features that are robust to the choice of imaging settings and are insensitive to variation [68–70, 73, 74]. Shape features, area under the curve of the cumulative histogram, and histogram-derived entropy were very reliable first-order features (with less than 5.0% of standard deviation) in a repeatability analysis of a prospective multicenter cohort study. Entropygray-level-cooccurrence-matrix features (GLCM), sum entropyGLCM, and difference entropyGLCM were the most repeatable second-order features. Small zone size emphasis and zone size percentage were reliable third-order features [75]. A small number of features were found to be repeatable (intraclass correlation coefficient = < 0.8) for size, FDG uptake, image reconstruction, noise, discretization method, and segmentation in a repeatability analysis with a phantom study. Intensity and entropy of second-order features were also repeatable [68]. In another study, the inverse difference moment GLCM was insensitive to variations in segmentation, discretization, and reconstruction methods [69]. Low gray level run emphasis (3rd-order feature), energy, maximal correlation coefficient (2nd-order feature), and entropy (1st-order feature) showed small variability (range ≤ 5%) according to different acquisition modes and reconstruction methods [65]. In addition, first-order features are less affected by tumor volume and provide reproducible values [73, 74]. PET imaging features with high reproducibility and low variability under different conditions are better candidates for radiogenomics. However, previous studies have some discrepancies about which features are robust, thus they must be carefully selected.

The other way for lowering the variability of PET radiomic features is to use a statistical method. PET images are affected by scanner, acquisition protocol, and reconstruction parameters, thus hindering multicenter studies. Orlhac et al. developed a post-reconstruction harmonization method based on Bayesian framework to adjust the multicenter effect for textural features and SUVs [76]. This method is likely to be efficient at removing the technical heterogeneity arising from different conditions of institutions where the research is conducted, which could facilitate the multicenter studies and external validation of PET radiomic models [76].

Implementation and maintenance of the effort to overcome the issues mentioned above will be increasingly important in this research field. It is likely that compliance with the methods will be assessed as a measure of research quality. For example, to evaluate the validity and completeness of radiomic studies, radiomics quality score (RQS) was proposed by Lambin et al. [77]. RQS consists of 16 key components such as robust segmentation, use of standardized imaging protocols, and use of validation dataset. Each component was assigned scores according to its importance [77].

Conclusion

Radiogenomics, linking of imaging phenotypes to distinct molecular phenotypes of cancer, can impact the treatment and prognosis of a wide range of human cancers and will help advance personalized medicine. In this review, we examined all the major radiogenomic studies using PET imaging and investigated the current status of this field of research. We discussed the limitations of PET-based radiogenomic studies and tried to address feasible solutions to these limitations. While PET imaging features have potential in radiogenomics, only a small number of radiogenomic studies have been published. The majority of studies were semi-radiogenomic, relating expression of specific genes to imaging features. Small study samples and lack of validation due to the scarcity of large datasets and vulnerabilities of PET radiomic features under different conditions are major challenges that still need to be addressed. However, with publicly available data sources, standardization of feature extraction, and careful selection of robust features, future studies could overcome many of the challenges impeding the advance of a PET-based radiogenomic approach.

Funding Information

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No.NRF-2016R1C1B2013411).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Yong-Jin Park, Mu Heon Shin, and Seung Hwan Moon declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Not applicable

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yong-Jin Park, Email: yjnm.park@samsung.com.

Mu Heon Shin, Email: muheon.shin@samsung.com.

Seung Hwan Moon, Email: seunghwan.moons.moon@samsung.com.

References

- 1.Schillaci O, Urbano N. Personalized medicine: a new option for nuclear medicine and molecular imaging in the third millennium. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:563–566. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai HX, Lee AM, Yang L, Zhang P, Davatzikos C, Maris JM, et al. Imaging genomics in cancer research: limitations and promises. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20151030. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20151030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe CC. Imaging and genomics: is there a synergy? Radiology. 2012;264:329–331. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazurowski MA. Radiogenomics: what it is and why it is important. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:862–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen RW, van Amstel P, Martens RM, Kooi IE, Wesseling P, de Langen AJ, et al. Non-invasive tumor genotyping using radiogenomic biomarkers, a systematic review and oncology-wide pathway analysis. Oncotarget. 2018;9:20134–20155. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reuter JA, Spacek DV, Snyder MP. High-throughput sequencing technologies. Mol Cell. 2015;58:586–597. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peeken JC, Bernhofer M, Wiestler B, Goldberg T, Cremers D, Rost B, et al. Radiomics in radiooncology - challenging the medical physicist. Phys Med. 2018;48:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang J, Rancati T, Lee S, Oh JH, Kerns SL, Scott JG, et al. Machine learning and radiogenomics: lessons learned and future directions. Front Oncol. 2018;8:228. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip SSF, Parmar C, Kim J, Huynh E, Mak RH, Aerts H. Impact of experimental design on PET radiomics in predicting somatic mutation status. Eur J Radiol. 2017;97:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acharya UR, Hagiwara Y, Sudarshan VK, Chan WY, Ng KH. Towards precision medicine: from quantitative imaging to radiomics. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2018;19:6–24. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1700260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijay P, McIntyre AB, Mason CE, Greenfield JP, Li S. Clinical genomics: challenges and opportunities. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2016;26:97–113. doi: 10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2016015724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding L, Wendl MC, Koboldt DC, Mardis ER. Analysis of next-generation genomic data in cancer: accomplishments and challenges. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R188–R196. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sala E, Mema E, Himoto Y, Veeraraghavan H, Brenton JD, Snyder A, et al. Unravelling tumour heterogeneity using next-generation imaging: radiomics, radiogenomics, and habitat imaging. Clin Radiol. 2017;72:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prasetyanti PR, Medema JP. Intra-tumor heterogeneity from a cancer stem cell perspective. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:41. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0600-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burrell RA, McGranahan N, Bartek J, Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. 2013;501:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreassen CN, Schack LM, Laursen LV, Alsner J. Radiogenomics - current status, challenges and future directions. Cancer Lett. 2016;382:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon SH, Kim J, Joung JG, Cha H, Park WY, Ahn JS, et al. Correlations between metabolic texture features, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation burden in patients with lung cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:446–454. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair VS, Gevaert O, Davidzon G, Napel S, Graves EE, Hoang CD, et al. Prognostic PET 18F-FDG uptake imaging features are associated with major oncogenomic alterations in patients with resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3725–3734. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gevaert O, Xu J, Hoang CD, Leung AN, Xu Y, Quon A, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: identifying prognostic imaging biomarkers by leveraging public gene expression microarray data--methods and preliminary results. Radiology. 2012;264:387–396. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crespo-Jara A, Redal-Pena MC, Martinez-Navarro EM, Sureda M, Fernandez-Morejon FJ, Garcia-Cases FJ, et al. A novel genomic signature predicting FDG uptake in diverse metastatic tumors. EJNMMI Res. 2018;8:4. doi: 10.1186/s13550-017-0355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto S, Huang D, Du L, Korn RL, Jamshidi N, Burnette BL, et al. Radiogenomic analysis demonstrates associations between (18)F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose PET, prognosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer. Radiology. 2016;280:261–270. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westerhoff HV, Palsson BO. The evolution of molecular biology into systems biology. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1249–1252. doi: 10.1038/nbt1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlachavas EI, Pilalis E, Papadodima O, Koczan D, Willis S, Klippel S, et al. Radiogenomic analysis of F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and gene expression data elucidates the epidemiological complexity of colorectal cancer landscape. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019;17:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodalal Z, Trebeschi S, Nguyen-Kim TDL, Schats W, Beets-Tan R. Radiogenomics: bridging imaging and genomics. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:1960–1984. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02028-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan BA, Hughes BG. Targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: current standards and the promise of the future. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:36–54. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.05.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang M, Zhang Y, Xu J, Ji M, Guo Y, Guo Y, et al. Assessing EGFR gene mutation status in non-small cell lung cancer with imaging features from PET/CT. Nucl Med Commun. 2019;40:842–849. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yip SS, Kim J, Coroller TP, Parmar C, Velazquez ER, Huynh E, et al. Associations between somatic mutations and metabolic imaging phenotypes in non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:569–576. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.181826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guan J, Xiao NJ, Chen M, Zhou WL, Zhang YW, Wang S, et al. 18F-FDG uptake for prediction EGFR mutation status in non-small cell lung cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4421. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho A, Hur J, Moon YW, Hong SR, Suh YJ, Kim YJ, et al. Correlation between EGFR gene mutation, cytologic tumor markers, 18F-FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:224. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2251-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon B, Varella-Garcia M, Camidge DR. ALK gene rearrangements: a new therapeutic target in a molecularly defined subset of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1450–1454. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c4dedb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon HJ, Sohn I, Cho JH, Lee HY, Kim JH, Choi YL, et al. Decoding tumor phenotypes for ALK, ROS1, and RET fusions in lung adenocarcinoma using a radiomics approach. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1753. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SJ, Hwang SH, Kim IJ, Lee MK, Lee CH, Lee SY, et al. The association of 18F-deoxyglucose (FDG) uptake of PET with polymorphisms in the glucose transporter gene (SLC2A1) and hypoxia-related genes (HIF1A, VEGFA, APEX1) in non-small cell lung cancer. SLC2A1 polymorphisms and FDG-PET in NSCLC patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:69. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Porru M, Pompili L, Caruso C, Biroccio A, Leonetti C. Targeting KRAS in metastatic colorectal cancer: current strategies and emerging opportunities. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:57. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0719-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovinfosse P, Koopmansch B, Lambert F, Jodogne S, Kustermans G, Hatt M, et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT imaging in rectal cancer: relationship with the RAS mutational status. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20160212. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawada K, Nakamoto Y, Kawada M, Hida K, Matsumoto T, Murakami T, et al. Relationship between 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation and KRAS/BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1696–1703. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JH, Kang J, Baik SH, Lee KY, Lim BJ, Jeon TJ, et al. Relationship between 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake and V-Ki-Ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog mutation in colorectal cancer patients: variability depending on C-reactive protein level. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2236. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miles KA, Ganeshan B, Rodriguez-Justo M, Goh VJ, Ziauddin Z, Engledow A, et al. Multifunctional imaging signature for V-KI-RAS2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations in colorectal cancer. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:386–391. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.120485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen SW, Shen WC, Chen WT, Hsieh TC, Yen KY, Chang JG, et al. Metabolic imaging phenotype using radiomics of [(18)F]FDG PET/CT associated with genetic alterations of colorectal cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019;21:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s11307-018-1225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oner AO, Budak ES, Yildirim S, Aydin F, Sezer C. The value of (18)FDG PET/CT parameters, hematological parameters and tumor markers in predicting KRAS oncogene mutation in colorectal cancer. Hell J Nucl Med. 2017;20:160–165. doi: 10.1967/s002449910557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen SW, Lin CY, Ho CM, Chang YS, Yang SF, Kao CH, et al. Genetic alterations in colorectal cancer have different patterns on 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:621–626. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Izuishi K, Yamamoto Y, Sano T, Takebayashi R, Nishiyama Y, Mori H, et al. Molecular mechanism underlying the detection of colorectal cancer by 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:394–400. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1727-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osborne JR, Port E, Gonen M, Doane A, Yeung H, Gerald W, et al. 18F-FDG PET of locally invasive breast cancer and association of estrogen receptor status with standardized uptake value: microarray and immunohistochemical analysis. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:543–550. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palaskas N, Larson SM, Schultz N, Komisopoulou E, Wong J, Rohle D, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission tomography marks MYC-overexpressing human basal-like breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5164–5174. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magometschnigg H, Pinker K, Helbich T, Brandstetter A, Rudas M, Nakuz T, et al. PIK3CA mutational status is associated with high glycolytic activity in ER+/HER2- early invasive breast cancer: a molecular imaging study using [(18)F]FDG PET/CT. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019;21:991–1002. doi: 10.1007/s11307-018-01308-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elisei R, Ugolini C, Viola D, Lupi C, Biagini A, Giannini R, et al. BRAF(V600E) mutation and outcome of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a 15-year median follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3943–3949. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagarajah J, Ho AL, Tuttle RM, Weber WA, Grewal RK. Correlation of BRAFV600E mutation and glucose metabolism in thyroid cancer patients: an (1)(8)F-FDG PET study. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:662–667. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.150607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi EK, Chong A, Ha JM, Jung CK, O JH, Kim SH. Clinicopathological characteristics including BRAF V600E mutation status and PET/CT findings in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Clin Endocrinol 2017;87:73–79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Chang JW, Park KW, Heo JH, Jung SN, Liu L, Kim SM, et al. Relationship between (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation and the BRAF (V600E) mutation in papillary thyroid cancer. World J Surg. 2018;42:114–122. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4136-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang M, Weiss WA. Neuroblastoma and MYCN. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a014415. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu YL, Lu MY, Chang HH, Lu CC, Lin DT, Jou ST, et al. Diagnostic FDG and FDOPA positron emission tomography scans distinguish the genomic type and treatment outcome of neuroblastoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:18774–18786. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen AL, Holmen SL, Colman H. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:345. doi: 10.1007/s11910-013-0345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Metellus P, Colin C, Taieb D, Guedj E, Nanni-Metellus I, de Paula AM, et al. IDH mutation status impact on in vivo hypoxia biomarkers expression: new insights from a clinical, nuclear imaging and immunohistochemical study in 33 glioma patients. J Neuro-Oncol. 2011;105:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0625-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lanic H, Mareschal S, Mechken F, Picquenot JM, Cornic M, Maingonnat C, et al. Interim positron emission tomography scan associated with international prognostic index and germinal center B cell-like signature as prognostic index in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:34–42. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.600482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kesch C, Radtke JP, Wintsche A, Wiesenfarth M, Luttje M, Gasch C, et al. Correlation between genomic index lesions and mpMRI and (68)Ga-PSMA-PET/CT imaging features in primary prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16708. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erba V, Gherardi M, Rotondo P. Intrinsic dimension estimation for locally undersampled data. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17133. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53549-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang W, Xie G, Ren Z, Xie T, Li J. Gene selection for the discrimination of colorectal cancer. Curr. Mol Med 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Fahr P, Buchanan J, Wordsworth S. A review of the challenges of using biomedical big data for economic evaluations of precision medicine. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17:443–452. doi: 10.1007/s40258-019-00474-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deng M, Bragelmann J, Schultze JL, Perner S. Web-TCGA: an online platform for integrated analysis of molecular cancer data sets. BMC Bioinformatics. 2016;17:72. doi: 10.1186/s12859-016-0917-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark K, Vendt B, Smith K, Freymann J, Kirby J, Koppel P, et al. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA): maintaining and operating a public information repository. J Digit Imaging. 2013;26:1045–1057. doi: 10.1007/s10278-013-9622-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bakr S, Gevaert O, Echegaray S, Ayers K, Zhou M, Shafiq M, et al. A radiogenomic dataset of non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Data. 2018;5:180202. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2018.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hatt M, Tixier F, Pierce L, Kinahan PE, Le Rest CC, Visvikis D. Characterization of PET/CT images using texture analysis: the past, the present... any future? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017;44:151–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Hatt M, Cheze-le Rest C, van Baardwijk A, Lambin P, Pradier O, Visvikis D. Impact of tumor size and tracer uptake heterogeneity in (18)F-FDG PET and CT non-small cell lung cancer tumor delineation. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1690–1697. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brooks FJ, Grigsby PW. The effect of small tumor volumes on studies of intratumoral heterogeneity of tracer uptake. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:37–42. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.116715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galavis PE, Hollensen C, Jallow N, Paliwal B, Jeraj R. Variability of textural features in FDG PET images due to different acquisition modes and reconstruction parameters. Acta Oncol. 2010;49:1012–1016. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.498437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hatt M, Lee JA, Schmidtlein CR, Naqa IE, Caldwell C, De Bernardi E, et al. Classification and evaluation strategies of auto-segmentation approaches for PET: report of AAPM task group no. 211. Med Phys. 2017;44:e1–e42. doi: 10.1002/mp.12124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hatt M, Majdoub M, Vallieres M, Tixier F, Le Rest CC, Groheux D, et al. 18F-FDG PET uptake characterization through texture analysis: investigating the complementary nature of heterogeneity and functional tumor volume in a multi-cancer site patient cohort. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:38–44. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.144055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pfaehler E, Beukinga RJ, de Jong JR, Slart R, Slump CH, Dierckx R, et al. Repeatability of (18) F-FDG PET radiomic features: a phantom study to explore sensitivity to image reconstruction settings, noise, and delineation method. Med Phys. 2019;46:665–678. doi: 10.1002/mp.13322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Altazi BA, Zhang GG, Fernandez DC, Montejo ME, Hunt D, Werner J, et al. Reproducibility of F18-FDG PET radiomic features for different cervical tumor segmentation methods, gray-level discretization, and reconstruction algorithms. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2017;18:32–48. doi: 10.1002/acm2.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boellaard R. Standards for PET image acquisition and quantitative data analysis. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):11S–20S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pfaehler E, Zwanenburg A, de Jong JR, Boellaard R. RaCaT: an open source and easy to use radiomics calculator tool. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang L, Fried DV, Fave XJ, Hunter LA, Yang J, Court LE. IBEX: an open infrastructure software platform to facilitate collaborative work in radiomics. Med Phys. 2015;42:1341–1353. doi: 10.1118/1.4908210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Forgacs A, Pall Jonsson H, Dahlbom M, Daver F, M DD, Opposits G, et al. A study on the basic criteria for selecting heterogeneity parameters of F18-FDG PET images. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Cook GJ, O'Brien ME, Siddique M, Chicklore S, Loi HY, Sharma B, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer treated with erlotinib: heterogeneity of (18)F-FDG uptake at PET-association with treatment response and prognosis. Radiology. 2015;276:883–893. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015141309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Desseroit MC, Tixier F, Weber WA, Siegel BA, Cheze Le Rest C, Visvikis D, et al. Reliability of PET/CT shape and heterogeneity features in functional and morphologic components of non-small cell lung cancer tumors: a repeatability analysis in a prospective multicenter cohort. J Nucl Med 2017;58:406–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Orlhac F, Boughdad S, Philippe C, Stalla-Bourdillon H, Nioche C, Champion L, et al. A postreconstruction harmonization method for multicenter radiomic studies in PET. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1321–1328. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.199935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, Peerlings J, de Jong EEC, van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(12):749–762. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]