Abstract

Background

Motor impairments are pervasive in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD); however, children with ASD rarely receive a dual diagnosis of Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD). The Simons Foundation SPARK study engaged families affected by ASD through an online study.

Objectives

The DCD parent questionnaire (DCDQ) was used to assess the prevalence of a risk for motor impairment or DCD in children with ASD between 5 and 15 years of age.

Design

This study utilizes parent reports from a large database of children with ASD.

Methods

A total of 16,705 parents of children with ASD completed the DCDQ. We obtained our final SPARK dataset (n = 11,814) after filtering out invalid data, using stronger cut-offs to confirm ASD traits, and excluding children with general neuromotor impairments/intellectual delays. We compared DCDQ total and subscale scores from the SPARK dataset with published norms for each age between 5 and 15 years.

Results

The proportion of children with ASD at risk for a motor impairment was very high at 86.9%. Children with ASD did not outgrow their motor impairments and continued to present with a risk for DCD even into adolescence. Yet, only 31.6% of children were receiving physical therapy services.

Limitations

Our analysis of a large database of parent-reported outcomes using the DCDQ did not involve follow-up clinical assessments.

Conclusions

Using a large sample of children with ASD, this study shows that a risk for motor impairment or DCD was present in most children with ASD and persists into adolescence; however, only a small proportion of children with ASD were receiving physical therapist interventions. A diagnosis of ASD must trigger motor screening, evaluations, and appropriate interventions by physical and occupational therapists to address the functional impairments of children with ASD while also positively impacting their social communication, cognition, and behavior. Using valid motor measures, future research must determine if motor impairment is a fundamental feature of ASD.

Keywords: Autism, DCD, Children, Motor, Diagnosis, Treatment

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is an increasingly prevalent neurodevelopmental disorder, with a US national survey reporting 1 in 40 children having an ASD diagnosis.1 Lifetime costs of supporting an individual with ASD range between $1.4 and $2.4 million, and annual societal costs are currently at $268 billion.2,3 Given the significant economic and emotional burdens associated with ASD, there is an urgent need to screen early for a diverse array of developmental problems and to develop effective interventions to improve future outcomes for the increasing number of children with ASD. ASD is characterized by impairments in social communication such as poor social reciprocity and a lack of/delayed verbal and nonverbal communication, as well as the presence of repetitive behaviors and restricted interests.4 Individuals with ASD also present with significant impairments in the motor domain, including impairments in limb and body coordination, balance, and gait.5,6 The prevalence of motor impairments in ASD is reported to be in the range of 50% to 85%7–10 and is a significant barrier to a child’s further social communication development as well as adaptive functioning.5,11,12

It is critical to study the prevalence of motor impairments in children with ASD for several reasons. First, social communication skills are in fact motoric in nature (eg, new-found walking abilities are used to share objects with caregivers),13,14 strong posture and balance provide the foundation from which to move and explore one’s surroundings,15 head motions are important to look towards people,16,17 and gestures such as pointing and showing are coordinated arm movements used to communicate with others;18 and these motor skills are clearly affected/atypical in children with ASD from a very young age.14,17–22 Second, motor delays are one of the earliest markers of ASD, and this gap in motor development continues to increase with age.23,24 Third, engaging in complex motor skills during play with peers and caregivers is vital to develop friendships and social connections.5 Fourth, lack of skilled movement in individuals with ASD contributes to inactivity, low physical fitness, and social isolation.25 Taken together, motor impairments are widely reported in children with ASD and will greatly impact their future social communication development, adaptive functioning, and quality of life.26,27 However, we still do not know what proportion of the ASD population in the United States has clinically significant motor impairments severe enough to be “at risk” for Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD).

Motor impairment is considered a comorbid symptom of ASD; however, it is rarely recognized by assigning a co-occurring diagnosis of DCD.28 DCD is characterized by impairments in gross- and fine-motor coordination (unrelated to specific medical or neurological condition) that significantly affect a child’s academic achievement and daily functioning.4 One in 16 children are diagnosed with DCD in the general school-age population,28 and it profoundly impacts a child’s ability to learn and perform everyday motor skills and engage in play with peers and eventually affects his/her physical fitness/health29–30 as well as social-emotional well-being.31 Recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) criteria specifically allow children to hold a dual diagnosis of ASD and DCD.4 However, given the complex, multisystem presentation of ASD, it is difficult for clinicians (ie, pediatricians, clinical psychologists, and developmental neurologists who diagnose ASD or pediatric physical or occupational therapists who treat motor problems) to differentiate whether the motor comorbidities impact daily functioning above and beyond the core impairments associated with ASD.32 Additionally, if motor impairments are already pervasive in the ASD population, it is difficult to determine the level of motor impairment that warrants a dual diagnosis of DCD. Ultimately, the under-recognized nature of motor impairments in ASD makes it difficult for children and families to access occupational therapy (OT)/physical therapy services. This study addresses the question of how prevalent a professional DCD diagnosis is in children with ASD and how many more children with ASD in fact are at risk for DCD using the DCDQ screening questionnaire33 despite not having a formal diagnosis of DCD. Lastly, we also report the types of services children with ASD are receiving to address their motor impairments.

There is overwhelming evidence supporting the pervasive nature of motor impairments or DCD in children and adolescents with ASD. Systematic reviews of the literature, as well as large sample studies, confirm the presence of impairments in fine/gross motor coordination, balance, and gait in school-age children with ASD based on performance on standardized assessments.5–8,34–37 Children with ASD have significant impairments in gross-motor skills such as bilateral coordination,7,34,36,37 visuo-motor coordination (eg, ball catching),35–39 and balance7,34–37 as well as impairments in fine motor skills (eg, handwriting,37–39 drawing/copying skills,37–39 and manual dexterity/motor speed)23,34,37,39 compared with typically developing (TD) children as well as those with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Specific Language Impairments. A thorough meta-analysis of the motor literature in ASD confirmed that motor impairments are a cardinal feature of ASD and are seen across individuals with differing levels of impairment and at all ages.6 Using the Movement Assessment Battery for Children 2nd ed., 79% of children with ASD had a definite movement impairment and another 10% had borderline movement problems.7 Additionally, the DCD questionnaire33 performed moderately well as a screening tool for movement problems in ASD after it was validated against the Movement Assessment Battery for Children 2nd ed.7 Specifically, a positive predictive value of 91% to 92.5% was reported, suggesting that a positive screen on the DCDQ is probably accurate in 91% to 92.5% of screened individuals.7 In the current SPARK database analysis, DCDQ is the primary measure used to report a risk for motor impairment.

The SPARK study’s online database in its version 3 release includes the DCDQ33 and the Social Communication Questionnaire–Lifetime (SCQ)40 dataset for thousands of participants with ASD. Additionally, there is a rich dataset of basic demographic information such as sex, age, family role/type, medical history screening (eg, birth history, diagnostic information, professional diagnosis of DCD/motor delay as well as detailed individual history including developmental milestones and level of impairments and special education/intervention services received). This rich information allowed for the examination of the prevalence of motor impairments across various subgroups separated by sex and family role/type and across ages in a large group of children with ASD. We also hypothesized that DCD will be more prevalent in male versus female children with ASD.41 Motor impairments would be similar across probands and siblings with ASD given that concordant siblings with ASD show similar levels of motor impairment.42 Although we expected DCD symptoms to decrease with time, the symptoms were not expected to fully ameliorate with development given reports of persistent/increasing gaps in motor performance in children and adolescents with ASD.23–24 This study also predicted that few children with ASD would have a professional diagnosis of DCD, with many children remaining undiagnosed, and that a large proportion of children with ASD were not receiving any physical therapist services they may need.

Methods

SPARK Data Collection Procedures

The SPARK study recruited families throughout the United States who have 1 or more children with ASD by collaborating with 21 clinical sites across the United States and through a multi-pronged social media strategy.43 Families were asked to voluntarily sign up for the study on the SPARK website to complete online questionnaires (https://sparkforautism.org/registration/account_information/). Families also received information on studies in their nearby community to volunteer for local research studies. At the same time, researchers throughout the United States, such as this research group, signed up to be a SPARK research partner to utilize the SPARK study recruitment resources. In this process, we gained access to the SPARK database that allowed for analyses such as the ones reported in this paper.

SPARK Participant Data

Data Access Procedures

Deidentified SPARK data files were made available after University of Delaware signed an authorization agreement with the Simons Foundation to gain access to their study database. We also utilize SPARK as a recruitment resource for research studies approved by the University of Delaware’s Human Subjects Review Board and the SPARK Institutional Review Board, which also allows for secure data sharing. The SPARK Version 3 dataset (release date: February 2019), comprised of multiple parent questionnaires, was downloaded from SFARI base (https://base.sfari.org). Of those, this study analyzed the following: (1) the basic medical screening form, which listed demographic information, birth history, professional diagnosis of ASD and other disorders, and other general medical conditions; (2) the individual data form, which listed details on when the ASD diagnosis was made, who made it, whether the child has a known cognitive, language, or functioning impairment compared with same-age peers, whether there was an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for the child, and whether the child receives ASD services; and (3) the background history form, which listed the various intervention services received by each participant. In terms of diagnoses, we are reporting whether a professional diagnosis of DCD/motor delay, Communication Disorder, ADHD, or Learning Disability was also assigned to each participating child with ASD. Apart from these participant details, data from 2 questionnaires, were analyzed as discussed below.

DCD Questionnaire

DCDQ33 is a 15-item parent questionnaire to assess a child’s gross- and fine-motor coordination during everyday functional/play skills within the child’s natural environment. It includes an array of ball skills (eg, hitting or catching a ball), complex whole-body coordination skills (eg, jumping, running, etc), fine motor skills (eg, writing, cutting, etc) as well as general motor control abilities (eg, quickness, clumsiness, fatigability, etc). These skills are divided across 3 subscales of “control during movement,” “fine motor coordination,” and “general coordination.” Each subscale has a total raw score, and a summation of the 3 subscales provides a total “final score.” For children between 5 years and 7 years 11 months, a score below 47 indicates a definite motor impairment or suspect DCD (<10th percentile). For children between 8 years and 9 years 11 months, a score below 56 indicates a definite motor impairment or suspect DCD (<10th percentile). For children between 10 and 15 years, a score below 58 indicates a definite motor impairment or suspect DCD (<10th percentile). Itemized scores, subscale scores, total scores, and an assignment of at risk for DCD based on criteria listed above (yes = 1, no = 0) were provided for each participant. A diagnosis of DCD is typically confirmed with a follow-up, standardized motor assessment, and clinical judgment of a trained movement clinician.

Social Communication Questionnaire

Lifetime (SCQ)40 is a 40-item parent questionnaire to screen for autistic traits in children older than 4 years of age. It is based on a well-validated diagnostic interview, the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised. A total score ≥12 is typically considered a research-recommended, more sensitive cut-off and was used in this analysis.44–47

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Broader Dataset

Within the shared SPARK data, there are data available from 150,064 individuals, including children with ASD and their family members. However, we were interested in assessing motor impairments in children with ASD; and used a base sample comprised of 16,705 children with ASD whose parents completed the DCDQ form. Parents of 364 children skipped certain items on the questionnaire; hence, per publisher guidelines, final DCDQ scores were not assigned to them. Three children who were younger than the valid age range of <5 years for DCDQ administration were also excluded. After these exclusions, there were 16,338 individuals with a valid DCDQ administration (mean age: 9.5 ± 3.2; M = 12,991, F = 3347). Given that this was an epidemiological survey, confirmation that the participants were truly affected by ASD was necessary. To confirm an ASD diagnosis, children were identified with robust criteria for ASD diagnosis (ie, diagnosis age ≥18 months or an IEP for ASD), which reduced the sample to 16,287 (Tab. 1, ASD diagnosis is said to be stable after 18 months or an IEP for ASD indicates the diagnosis remained stable).47 Next, participants were identified who had completed a valid SCQ-Lifetime (ie, <3 items missing), which reduced the sample to 15,888 (Tab. 1). Only Individuals who met SCQ cut-offs of ≥12 participated, which reduced the sample to 14,745 (Tab. 1). Note that a cut-off score of ≥12 is considered more sensitive for ASD screening.44–47 Of all children with ASD, 92.8% of children met the recommended cut-off, whereas 7.2% did not meet criteria for ASD risk on the SCQ screen and were not included (ie, 14,745 participants remained after this step). Lastly, it was confirmed that the children with ASD did not have global developmental delays or neuromotor injuries unrelated to ASD by excluding children with medical conditions/birth injuries (ie, brain and spinal cord malformations, prenatal alcohol/drug exposure, intraventricular hemorrhage) and diagnoses of global developmental delay or borderline intellectual functioning/cognitive impairment. After applying these exclusion criteria, 11,814 participants were left who had completed a valid administration of DCDQ and SCQ, met criteria for risk for motor- and autism-specific delays on the DCDQ and SCQ, respectively, and met relevant inclusion/exclusion criteria (Tab. 1). All data filtering was conducted in Microsoft Excel. JMP Pro 14 was used for statistical analyses and graphing (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Table 1.

Filters Used to Remove Samples Based on DCDQ, SCQ, and Birth Injury Criteriaa

| Criterion for Removing Samples | No. of Samples Removed | No. of Samples Retained |

|---|---|---|

| Original dataset | 16,705 b | |

| DCDQ final score was not assigned due to missing items | 364 | 16,341 |

| Age at DCDQ evaluation was <60 mo | 3 | 16,338 |

| No professional diagnosis of ASD | 0 | 16,338 |

| Diagnosis age <18 no and no IEP | 51 | 16,287 |

| Inclusion criteria | ||

| Assigned as invalid using SCQ validity column | 4 | 16,283 |

| SCQ test was not completed | 171 | 16,112 |

| SCQ final score was not assigned due to missing items | 224 | 15,888 |

| SCQ final score <12 | 1143 | 14,745 |

| Exclusion criteria | ||

| CNS malformations (brain, spinal cord) | 75 | 14,670 |

| Prenatal alcohol or drug exposure | 118 | 14,552 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 120 | 14,432 |

| Delays or impairment due to brain injury, stroke, lead poisoning, FAS, HIV, radiation, hydrocephalus, brain tumor, drug effects, etc. | 545 | 13,887 |

| Diagnosed with cognitive impairment/intellectual disability | 2073 | 11,814 |

| Final dataset | 11,814 | |

The final dataset includes samples for which valid DCDQ and SCQ scores are available. ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; CNS = Central Nervous System; FAS = Fetal Alcohol Syndrome; HIV = Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IEP = Individualized Education Plan; DCDQ = Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire; SCQ = Social Communication Questionnaire.

This corresponds to the number of completed DCDQ questionnaires.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square testing was done to test the significance of risk for DCD versus no DCD by comparing them with data published by Rivard et al on DCD prevalence in the general population.41 To assess differences based on sex, age, and family role/type, the proportions for DCD/no DCD between boys and girls were compared between 2 age bands (5–7 vs 8–15 years) or probands and siblings with ASD. Independent t tests were conducted to assess group differences in motor performance for all scores (total and subscale) across ages for both male and female children with ASD from the select SPARK dataset and TD children from the Nakai et al dataset.48 One-way ANOVAs with age as a factor (10 age bands) were conducted to assess age-related differences in motor performance for all scores within each group. The summary statistics provided by Nakai et al in their TD sample included mean, SD, and number of samples obtained at each age between 5 and 15 years.48 Statistical significance was modified based on P value thresholds set after Bonferroni corrections.

Role of the Funding Source

The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Results

Proportion Data on Co-occurring Diagnoses and Services Received

Only 15.1% of children with ASD held a dual diagnosis of DCD, whereas 58% of children with ASD had a communication disorder (ie, articulation problems, pragmatic communication disorder, language delay/disorder, or mutism), 40.8% had ADHD, and 17.9% had a learning disability (Tab. 2). Parents also reported that, compared with same-age peers, 45.9% of the children with ASD had below-age cognition, 55.5% of the children with ASD had below-age language abilities, and 72.9% of the children with ASD had below-age functioning (Tab. 2). In terms of services received, 86.5% of the children with ASD were receiving ASD services, 83.1% of the children with ASD had a formal IEP in relation to the ASD diagnosis, 63.2% were receiving behavioral/developmental interventions, 47.1% received social skill interventions, 82% received speech therapy, and 79.8% received occupational therapy, whereas only 31.6% received physical therapies and 13% received recreational therapies (ie, play, aquatic, and hippo-therapy, etc.) (Tab. 2). Taken together, a small proportion of the children with ASD held a dual diagnosis of DCD, whereas many more children with ASD held other co-occurring diagnoses (communication disorders, ADHD, or learning disability). A large proportion of the SPARK sample is performing below-age in their level of functioning (72.9%). In terms of services received, the majority of the children with ASD received behavioral/developmental, speech, and occupational therapy services, whereas only 31.6% received physical therapist services and 13% received recreational therapies.

Table 2.

Proportion of Diagnosis and Services Provideda

| Diagnoses and Services | Percentage of Total (n = 11,814) |

|---|---|

| Professional Co-Diagnoses | |

| DCD | 15.1% |

| ADHD | 40.8% |

| Learning disability | 17.9% |

| Parent reports of levelsb | |

| Below-age cognition | 45.9% |

| Below-age language | 55.5% |

| Below-age functioning | 72.9% |

| ASD services received | 86.5% |

| IEP with ASD diagnosis | 83.1% |

| Services received portion | |

| Behavioral/developmental interventions | 65.2% |

| Speech and language therapy | 82% |

| Social skills | 47.1% |

| Therapies with motor emphasis | |

| Occupational therapy | 79.8% |

| Physical therapy | 31.6% |

| Recreational therapy | 13% |

aPercentages of professional diagnoses, levels of cognition, language, and functioning compared with same-age peers, and those who receive Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) services, hold an IEP with ASD, and other services. ADHD = Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; DCD = Developmental Coordination Disorder; IEP = Individualized Education Plan.

bParent reports of number of children “slightly or significantly below age” compared with same-age peers.

Proportion Data on Risk for DCD

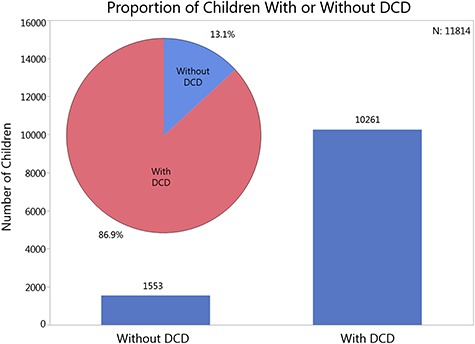

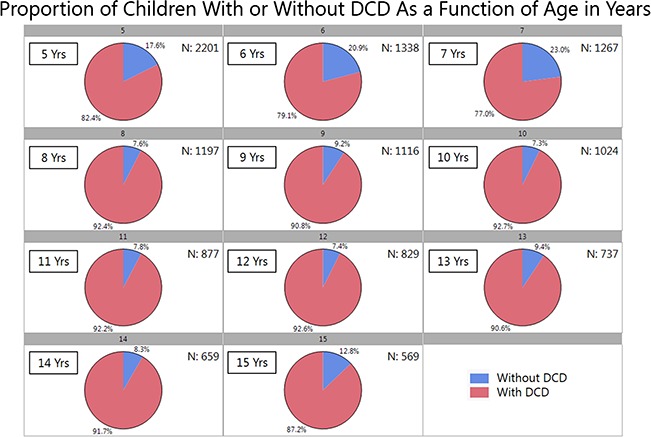

DCDQ data were fairly uniformly distributed across the scoring range and age range (Suppl. Fig. 1 available at https://academic.oup.com/ptj). First, 86.9% of the children with ASD fell in the range of having a definite motor impairment based on their final DCDQ scores and were identified as at-risk for DCD (γ2 = 104.9, df = 1, P < .0001, Fig. 1). However, it is noteworthy that chi-square testing revealed no significant differences in proportions for DCD risk between boys and girls or siblings and probands. Next, the change in DCDQ scores with age was explored. Between 5 and 7 years of age, there was a gradual decrease in the proportion of children with ASD identified as “at risk” for DCD (82.4% to 79.1% to 77%). At 8 years of age, there appears to be a 10% increase in DCD risk, which remains stable up to 15 years of age with 87.2% to 92.7% of the children with ASD identified as at risk for DCD (γ2 = 5.8, df = 2, P = .01, Fig. 2). Interestingly, this high proportion of DCD risk in children with ASD did not change with age after the 8-year mark. Taken together, across all categories of age, sex, and family role/type, after about 8 years of age approximately 86% or more children with ASD appear to be at risk for DCD.

Figure 1.

Proportion of children with or without risk for Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) in the SPARK dataset. Bars indicate number of samples, whereas the pie chart inset shows the sample proportions of children with or without a risk for DCD.

Figure 2.

Proportion of children with or without a risk for Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) as a function of age at evaluation in years.

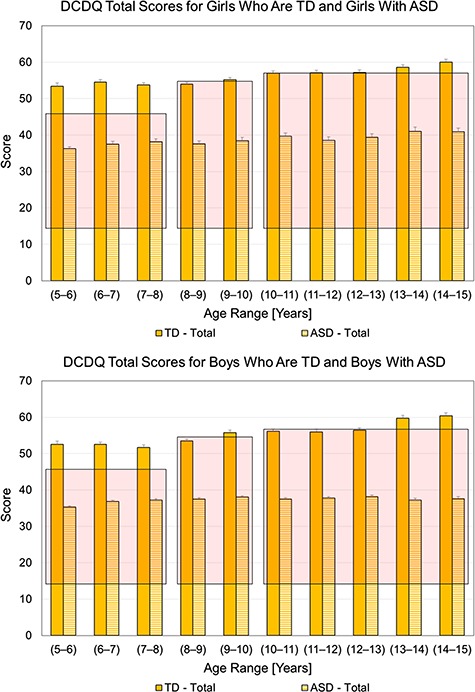

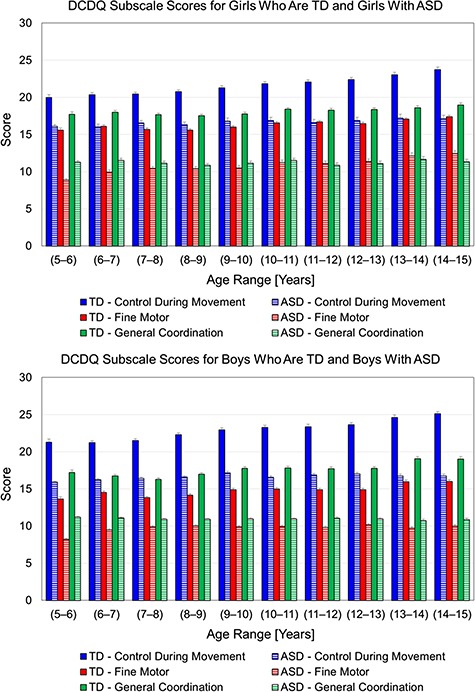

Comparing SPARK Data With Published Normative DCDQ Data

In terms of group differences, children with ASD had significantly lower scores than the TD group at all ages. To be clear, the ASD group always fell within the “at-risk” scoring range (shaded regions in Fig. 3), and the TD group consistently scored above the risk range, suggestive of no risk for motor impairment (Fig. 3). The calculated t values ranged from 8 to 24 and the maximum tabulated t value is approximately 3.3. All between-group Ps were <.0013 after Bonferroni corrections (see total scores in Fig. 3 and subscale scores in Fig. 4). Data corresponding to this analysis (for the ASD group) are also presented in Supplementary Table (available at https://academic.oup.com/ptj).

Figure 3.

Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ) total scores for girls who are Typically Developing (TD) and girls with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (top panel) and boys who are TD and boys with ASD (bottom panel) as a function of age at evaluation in years. Data corresponding to TD are adapted from Nakai et al. 48 Solid and dashed bars correspond to TD (Nakai et al) and ASD (SPARK data), respectively. Overlaid shaded boxes represent the score ranges corresponding to indication of Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), that is, at risk. All between-group P values were <.001 after Bonferroni corrections.

Figure 4.

Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ) subscale scores (control during movement, blue; fine motor, red; general coordination, green) for girls who are Typically Developing (TD) and girls with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (top panel) and boys who are TD and boys with ASD (bottom panel) as a function of age at evaluation in years. Data corresponding to TD are adapted from Nakai et al .48 Data corresponding to ASD are based on the SPARK dataset. Solid and dashed bars correspond to TD and ASD, respectively. All between-group P values were <.001 after Bonferroni corrections.

In the typical sample from Nakai et al, there was a significant effect of age (Ps < .0005 for total and subscale scores), with final scores improving across 3 age bands in boys (5–9, 9–13, and 13–15 years) and 2 age bands in girls (5–10 and 10–15 years). In the SPARK ASD sample, there was a significant effect of age (Ps < .0001) for total scores of both boys and girls as well as certain subscale scores such as control during movement in boys with ASD only (not girls) and fine motor subscales in both boys and girls with ASD. To be clear, both boys and girls with ASD did not show any improvements in the general coordination subscale between 5 and 15 years. In terms of final scores, boys with ASD showed small improvements between 5 and 6 years and then plateaued in terms of their motor performance from 6 to 15 years. In contrast, girls with ASD did not show improvements in final scores between 5 and 13 years and later had small improvements between 13 and 15 years of age. It should be noted that both boys and girls with ASD were always at risk for DCD between 5 and 15 years despite the small motor improvements.

Discussion

Children With ASD Are Not Being Co-diagnosed With DCD and Are Not Receiving Adequate Physical Therapist Services Despite Being at Risk for DCD

Only 15.1% of the children with ASD between 5 and 15 years held a professional diagnosis of DCD/motor delay, and only 31.6% of the children with ASD were receiving physical therapist services. However, 86.9% (range = 77–92.7%) of parents of children with ASD reported that their child was at risk for DCD (<10th percentile for motor performance). This substantial discrepancy between the presence of a risk and a formal diagnosis of motor impairment or DCD highlights the under-recognized nature of motor impairments in children with ASD. Furthermore, with 73% of the children with ASD performing below-age in functioning and only 32% of the children with ASD receiving physical therapist services, this population is being under-treated in terms of receiving a full array of motor interventions. The under-recognition of motor impairments in ASD as well as a lack of a coexisting DCD diagnosis has also been reported in other studies.7,32

Age-Related Differences in DCDQ Performance

In terms of age-related effects, proportion data showed that the proportion of children at risk for DCD was lower between 5 and 7 years of age, increased by 10% at the 8-year mark, and remained unchanged until 15 years of age. We compared DCDQ subscale and total scores from the SPARK database with the scores of TD children using the Nakai et al data.48 To the best of our knowledge, Nakai et al is the only paper that has reported on typical DCDQ subscale and total scores in both sexes and each age between 4 and 15 years. For all subscales and total scores, children with ASD were significantly deficient in their motor performance compared with the TD controls matched by age and sex and met criteria for risk for DCD. Male and female TD children showed a systematic increase in DCDQ subscales and total scores between 5 and 15 years of age, as is reported in Nakai et al.48 However, male children with ASD showed small improvements between 5 and 7 years and plateaued in their motor performance up until 15 years. In contrast, female children with ASD did not show any improvements until 13 years and later somewhat improved between 13 and 15 years of age but remained at risk for DCD. These findings suggest that children who were typically developing steadily improved their motor skills; however, children with ASD showed substantial motor impairments with differing trajectories. It is notable that the male children with ASD showed small improvements until 7 years of age, plateaued in their development thereafter, and never seemed to catch up with age- and sex-matched TD peers. The 5- to 7-year period (and earlier preschool years as well) might be a critical period to offer motor skills training (ie, physical therapist and occupational therapist services) to help accelerate motor development in the children with ASD. In a different study involving children with ASD, DCD, and ADHD, when children were screened for a motor delay during preschool years and later followed-up after 2 years, all groups improved; however, only children with no initial diagnosis showed the greatest motor improvements, followed by children with ADHD, and lastly those with ASD.49 Hence, the initial improvement seen in the children with ASD from the SPARK dataset is somewhat consistent with what was reported earlier. Motor performance within the second year of life is associated with ASD outcomes later in life.50,51 Motor performance of newly diagnosed children with ASD was predictive of future outcomes at 8 years of age.50 This suggests that children with ASD will benefit from early motor interventions not only to address their motor impairments but also to shift their overall trajectories of development to facilitate social communication and behavior/cognitive skills and eventually reduce their autism severity.

Motor Impairment or DCD Needs More Recognition/Diagnosis in Children With ASD

This study joins the copious literature confirming the pervasive nature of motor impairments in children and adolescents with ASD.5–7 The SPARK data show that most of the parents are reporting that their children with ASD are at risk for DCD (without actually holding an additional diagnosis of DCD). Of this sample, 73% are also reporting that their child is functioning below their same-age TD peers. It is challenging to determine how much of the functioning impairments in children with ASD are associated with the ASD-specific impairments in social communication and repetitive behaviors versus motor impairments given the multisystem nature of the disorder. The majority of the children with ASD seem to qualify for a dual diagnosis of DCD; however, the current diagnostic practices rarely capture the motor impairments in ASD using a dual diagnosis of DCD despite such a provision in the DSM-V. Through these robust findings, we join many other studies in urging diagnostic clinicians (pediatricians, psychologists, psychiatrists, and developmental neurologists) to recognize the high comorbidity of motor impairments/DCD in children with ASD and to co-diagnose DCD in this population for families to gain access to appropriate motor interventions.52 In the long term, we must recognize that motor impairments are a defining feature of ASD and should be included within the diagnostic framework for ASD. One way to recognize motor impairments could be to add them as a specifier within DSM criteria, as suggested by Licari et al.53

Is Motor Impairment in ASD Distinct From DCD?

Although this study offers epidemiological evidence for a pervasive motor impairment in a large sample of children with ASD, we are far from understanding the underlying mechanisms for the co-occurrence of these 2 diagnoses. Recent literature has attempted to shed light on whether ASD and DCD are distinct disorders that simply co-occur in some children or whether motor impairment is truly a defining feature of ASD.32,54–56 Some have argued that DCD symptoms in a child with developmental issues may be suggestive of a general brain dysfunction; hence, it is not specific to ASD.57 A recent systematic review highlighted multiple behavioral similarities and differences between children with ASD and DCD and concluded that motor impairments tend to be similar across the 2 groups, with children with high-functioning ASD and those with DCD performing at similar levels.32 Furthermore, ASD is a more complex multisystem disorder wherein some children with ASD may have greater symptom severity that extends across motor, social communication, and cognitive/behavioral systems compared with children with DCD.32 A lone neuroimaging study comparing motor performance and functional connectivity between children with ASD + DCD, ASD only, DCD only, and typically developing (TD) controls revealed that although the level and nature of motor impairment were fairly similar between children with ASD + DCD compared with children with DCD only, there was little overlap in the connectivity abnormalities observed across the 2 groups.54 In fact, connectivity patterns of children with “DCD only” were least abnormal and closest to those of TD controls, whereas children with ASD or ASD + DCD showed ASD-specific excessive short-range connectivity, which was not seen in children with DCD. Moreover, children with a dual diagnosis of ASD + DCD showed more widespread abnormalities across multiple brain regions compared with those with ASD only or DCD only.54 Hence, both behavioral and neuroimaging evidence suggest that ASD has a much more distinct and complex neuropathology compared with DCD; motor impairments in ASD are related to its original neuropathology.54–56 These new findings support the inclusion of motor impairment as a part of the diagnostic criteria for ASD, also emphasized in the recent paper by Licari and colleagues.53 Until appropriate changes are made to the ASD criteria within the DSM, clinicians must continue to utilize the current DSM provision to offer children with ASD a dual diagnosis of DCD based on motor screening and a detailed motor evaluation.

The sensori-motor integration impairments in children with ASD can be easily explained by the neural connectivity theory.58–63 Studies in children and adults with ASD report excessive short-range neuronal connectivity within the frontal, parietal, temporal, and visual cortices along with reduced long-range connectivity between cortices (eg, reduced fronto-temporal or fronto-parietal connectivity).58–63 Additionally, disordered or poor long-range connectivity has been reported in cortico-subcortical networks such as cortical-cerebellar,60 cortico-striatal,61 and cortico-thalamic62 connections as well as inter-hemispheric, callosal connectivity.63 These widespread abnormalities encompass multiple brain structures important for sensori-motor, social communication, and cognitive functions and hence explain the multisystem impairments of children with ASD, including sensory processing difficulties and coordination/balance impairments. Therefore, consistent with past literature reviews, one could hypothesize that motor impairments are a fundamental feature and result from the original neuropathology leading to ASD.6,56 In fact, the SPARK dataset shows that the majority of the children with ASD are at risk for DCD; however, not all children with DCD will present with ASD symptoms.32,54–55 Given the lack of consensus in the current literature, large-scale clinical studies are still needed to compare subdomains of motor and social performance as well as neuroimaging findings between children with ASD + DCD, ASD only, and DCD only as well as other control groups with general motor/cognitive impairments to better understand the distinctions between ASD, DCD, and other disorders. Secondly, if motor symptoms are indeed defining features of ASD, it would be important to show direct relationships between motor symptoms and autism severity. Third, it would be important to compare motor abilities of children with differing levels of cognitive ability to control for cognitive impairments and reduce sample variability. Together, such studies would help resolve the debate on whether ASD and DCD simply co-occur in children due to shared etiologies/neuropathologies32,54,55 or if motor impairments are a defining feature of ASD.6,56

Motor Assessments and Interventions Are Critical for Children With ASD

Given the high prevalence of DCD in children with ASD throughout childhood, it is recommended that a diagnosis of ASD should trigger further motor screening and evaluations by physical therapists and occupational therapists. Both physical therapists and occupational therapists need to be motor advocates for children with ASD during team meetings involving various health professionals in hospitals, schools, and early intervention settings. Administering brief screening measures such as the DCDQ would help identify children at risk for DCD, and comprehensive motor evaluations would help diagnose motor impairments early and increase access to physical therapist and occupational therapist interventions to promote age-appropriate functional skills and motor development throughout childhood and adolescence. Data on services provided show that whereas a large proportion of children with ASD receive occupational therapy services focused on addressing fine motor functions and sensory processing difficulties, only 32% children with ASD receive physical therapist services. Given the high prevalence of motor impairment in children with ASD, there is a clear need to increase access to physical therapist services for children with ASD because pediatric physical therapists have the expertise to facilitate gross motor functions/skills. Finally, only 13% of children engaged in recreational therapies, which highlights the lack of opportunities for habitual physical activity in children with ASD. Our past systematic review has described the negative health consequences of low physical activity levels and offered specific recommendations for improving physical activity in individuals with ASD.25

Motor interventions offered by physical therapists and occupational therapists must address multiple domains of development, including enhancement of motor, social communication, and cognitive/behavioral skills.64,65 It would be important to address the interests and needs of the child and the family and to include families in the decision-making process to develop intervention programs that will be successful in the long term. For example, use of creative movement such as music and movement, dance, yoga, mindful play, adaptive sport/games, outdoor play, and general physical activity (promoting strength, endurance, and mobility) within small group settings can be highly beneficial for children with ASD and for developing positive relationships with peers and caregivers.65–70 It is important to incorporate principles of motor learning (repetition, part-whole practice, trial and error learning, simple feedback) as well as principles from standard ASD intervention approaches such as Applied Behavioral Analysis (repetitions, prompting, reinforcement), Teaching Education and Communication to Handicapped Children (small spaces, structured contexts, and consistency), Picture Exchange Communication Systems (picture schedules for structure and visual models), as well as developmental approaches for the intervention to be impactful for the children with ASD and their families.5,25,65–71,69 Lastly, the Cognitive Orientation to Occupational Performance has been effective in enhancing motor skill learning in children with DCD and should be further explored in children with ASD as well.72

Limitations

Despite analyzing a large population sample of children with ASD, this study on the SPARK dataset has some limitations. First, our analysis was based on a parent questionnaire, and we are unable to corroborate parent impressions of their child’s motor performance using a standardized assessment. Second, the SPARK dataset was compared with the data of Nakai et al, which used a Japanese version of the DCDQ.48 However, theirs is the only study to provide a comprehensive table of normative data for subscale/total DCDQ scores by age and sex. Additionally, DCDQ has been implemented worldwide in over 12 languages with high consistency and validity. Third, although this study attempted to reduce sample variability associated with general neuromotor/cognitive impairments, it is possible that not all were excluded. There are known shared etiologies between ASD diagnosis and other motor diagnoses, and it was difficult to eliminate children in the sample based on such etiologies (eg, premature birth). An opposing argument can be made that higher functioning children with ASD were included by excluding subgroups with neuromotor and cognitive impairments; however, the proportion results for the reported dataset (ie, a dual diagnosis of DCD and ASD, children with ASD at-risk for DCD, and percentages of services received) do not differ compared with the full SPARK dataset, and the exclusion criteria used only reaffirm that even relatively higher functioning children with ASD have a significantly greater risk for motor impairment. To be clear, these findings are generalizable to the entire SPARK dataset. Lastly, there was no diagnostic confirmation using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, the gold standard for confirming ASD diagnosis. However, rigorous filters were used to confirm that parents received a professional diagnosis of ASD for their child, were receiving ASD services as part of their school IEP, and met criteria for ASD symptoms on the SCQ. This approach to confirming ASD diagnosis is consistent with other publications reporting on data from other large databases such as the Interactive Autism Network.44–47

Conclusions

Using the SPARK study database, the largest ASD sample in the United States, this study found that at least 86.9% of the children with ASD are at risk for DCD throughout childhood and adolescence, whereas only 15.1% of this sample held a dual diagnosis of DCD/motor delay. Children with ASD never outgrew their motor difficulties. Motor impairments are clearly under-recognized, under-diagnosed, and under-treated in children with ASD. Preschool and elementary school years are a critical period for promoting motor skills. This is an urgent call to pediatricians, psychologists, psychiatrists, and neurologists to co-diagnose motor impairment or DCD in children with ASD, and in the long term, motor impairment should be included within the diagnostic framework for ASD as a criterion or a specifier. Whereas 86% of the children with ASD are at risk for DCD and 72% are functioning at below-age levels, only 32% of the children with ASD are receiving physical therapist services. These findings are an urgent call to increase access to physical therapist services for children with ASD. The presence of a motor delay in children with ASD must trigger follow-up screening and assessments by physical therapists and occupational therapists. Both physical therapists and occupational therapists need to be motor advocates within their clinical teams and must promote motor evaluations and multisystem interventions inclusive of the motor domain to address the problems of the whole child with ASD. Last but not the least, more well-planned studies are needed to resolve the debate on whether ASD and DCD are distinct disorders or if motor impairment is a fundamental feature of ASD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all families in SPARK, the SPARK clinical sites, and SPARK staff. The author appreciates obtaining access to the phenotypic data on SFARI Base.

Funding

A. Bhat’s research during the writing of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health through a CTR-ACCEL Pilot (Project PI), CTR-SHORE (Project PI), and CTR-Orbits (Co-I) award through Institutional Development Award (IdeA) funding (grant no. U54-GM104941, site principal investigator: Binder-Macleod), and the Dana Foundation’s clinical neuroscience grant.

Disclosure

The author completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

Approved researchers can obtain the SPARK population dataset described in this study at https://base.sfari.org/ordering/phenotype/sfari-phenotype by applying for the same at https://base.sfari.org.

References

- 1. Kogan MD, Vladutiu CJ, Schieve LA, et al. The prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder among US children. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20174161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buescher A, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leigh JP, Du J. Brief report: forecasting the economic burden of autism in 2015 and 2025 in the United States. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:4135–4139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhat A, Landa R, Galloway JC. Current perspectives on motor functioning in infants, children, and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1116–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fournier KA, Hass CJ, Naik SK, Lodha N, Cauraugh JH. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:1227–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Green D, Charman T, Pickles A, et al. Impairment in movement skills of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miyahara M, Tsujii M, Hori M, Nakanishi K, Kageyama H, Sugiyama T. Brief report: motor incoordination in children with behavior syndrome and learning disabilities. J Autism Dev Disord. 1997;27:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manjiviona J, Prior M. Comparison of behavior syndrome and high-functioning autistic children on a test of motor impairment. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25:23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dewey S, Cantell M, Crawford SG. Motor and gestural performance in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental coordination disorder, and/ or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13:246–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Macdonald M, Lord C, Ulrich D. The relationship of motor skills and adaptive behavior skills in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7:1383–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bedford R, Pickles A, Lord C. Early gross motor skills predict the subsequent development of language in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2016;9:993–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karasik LB, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Adolph KE. Transition from crawling to walking and infants’ actions with objects and people. Child Dev. 2011;82:1199–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Srinivasan S, Bhat A. Differences in object sharing between infants at risk for autism and typically developing infants from 9 to 15 months of age. Infant Behav Dev. 2016;42:128–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iverson J. Developing language in a developing body: the relationship between motor development and language development. J Child Lang. 2010;37:229–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gernsbacher MA, Stevenson JL, Khandakar S, Goldsmith HH. Why does joint attention look atypical in autism? Child Dev Perspect. 2008;2:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhat A, Downing K, Galloway JC, Landa R. Overt head turning during contingency learning and gross motor performance of young infants at risk for autism. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Poster presentation at the International Meeting For Autism Research (IMFAR); May 20-22, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gernsbacher M. Infant and toddler oral- and manual-motor skills predict later speech fluency in autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2008;49:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. West K, Leezenbaum N, Northrup J, Iverson J. The relation between walking and language in infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Dev. 2019;90:e356–e372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. LeBarton E, Iverson JM. Fine motor skill predicts expressive language in infant siblings of children with autism. Dev Sci. 2013;16:815–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nickel LR, Thatcher AR, Keller F, Wozniak RH, Iverson JM. Posture development in infants at heightened vs. low risk for autism spectrum disorders. Infancy. 2013;18:639–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Flanagan J, Landa R, Bhat A, Bauman M. Head lag in infants at risk for autism: a preliminary study. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66:577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Biscaldi M, Rauh R, Irion L, et al. Deficits in motor abilities and developmental fractionation of imitation performance in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2014;23:599–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lloyd M, MacDonald M, Lord C. Motor skills of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2013;17:133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Srinivasan S, Pescatello L, Bhat A. Current perspectives on physical activity and exercise recommendations for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Phys Ther. 2014;94:875–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McDonald M, Lord C, Ulrich DA. The relationship of motor skills and social communicative skills in school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder. Adapt Phys Activ. Q. 2013;30:271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mcdonald M, Lord C, Ulrich D. The relationship of motor skills and adaptive behavior skills in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7:1383–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Blank R, Barnett AL, Cairney J, et al. International clinical practice recommendations on the definition, diagnosis, assessment, intervention, and psychosocial aspects of developmental coordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61:242–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cairney J, Hay JA, Faught BE, Flouris A, Klentrou P. Developmental coordination disorder and cardiorespiratory fitness in children. Pediatr Exer Sci. 2007;19:20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rivilis I, Hay J, Cairney J, Klentrou P, Liu J, Faught BE. Physical activity and fitness in children with developmental coordination disorder: a systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:894–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cummins A, Piek JP, Dyck MJ. Motor coordination, empathy, and social behavior in school-aged children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caçola P, Miller H, Williamson PO. Behavioral comparisons in autism spectrum disorder and developmental coordination disorder: a systematic literature review. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2017;38:6–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schoemaker MM, Flapper B, Verheij NP, Wilson BN, Reinders-Messelink HA, de Kloet A. Evaluation of Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire as a screening instrument. Dev Med & Child Neurol. 2006;48:668–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jansiewicz EM, Goldberg MC, Newschaffer CJ, Denckla MB, Landa R, Mostofsky SH. Motor signs distinguish children with high functioning autism and Asperger’s syndrome from controls. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ament K, Mejia A, Buhlman R, et al. Evidence for specificity of motor impairments in catching and balance in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:742–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McPhillips M, Finlay J, Bejerot S, Hanley M. Motor deficits in children with autism spectrum disorder: a cross-syndrome study. Autism Res. 2014;7:664–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaur M, Srinivasan S, Bhat A. Comparing motor performance, praxis, coordination, and interpersonal synchrony between children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Res Dev Disabil. 2017;72:79–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kushki A, Chau T, Anagnostou E. Handwriting difficulties in children with autism spectrum disorders: a scoping review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:1706–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fleury A, Kushki A, Tanel N, Anagnostou E, Chau T. Statistical persistence and timing characteristics of repetitive circle drawing in children with ASD. Dev Neurorehabil. 2013;16:245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berument SK, Rutter M, Lord C, Pickles A, Bailey A. Autism screening questionnaire: diagnostic validity. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rivard L, Missiuna C, McCauley D, Cairney J. Descriptive and factor analysis of the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire (DCDQ’07) in a population-based sample of children with and without Developmental Coordination Disorder. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;1:42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hilton CL, Zhang Y, Whilte MR, Klohr CL, Constantino J. Motor impairment in sibling pairs concordant and discordant for autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2012;16:430–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. The SPARK Consortium SPARK: a US cohort of 50,000 families to accelerate autism research. Neuron. 2018;97:488–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Daniels AM, Rosenberg RE, Anderson C, Law JK, Marvin AR, Law PA. Verification of parent-report of child autism spectrum disorder diagnosis to a web-based autism registry. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee H, Marvin AR, Watson T, et al. Accuracy of phenotyping of autistic children based on internet implemented parent report. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;0:1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marvin AR, Marvin D, Lipkin PH, Law K. Analysis of Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) screening for children less than age 4. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2017;4:137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Stone WL, et al. Identification of autism spectrum disorder: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatr. 2015;136:S10–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nakai A, Miyachi T, Okada R, et al. Evaluation of the Japanese version of the Developmental Coordination Disorder Questionnaire as a screening tool for clumsiness of Japanese children. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1615–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Van Waelvelde H, Oostra A, Dewitte G, Van Den Broek C, Jognsman M. Stability of motor problems in young children with or at risk of autism spectrum disorders, ADHD, and or developmental coordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:e174–e178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sutera S, Pandey J, Esser EL, et al. Predictors of optimal outcome in toddlers diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37:98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brian J, Bryson SE, Garon N, et al. Clinical assessment of autism in high-risk 18-month-olds. Autism. 2008;12:433–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Harris SR, Mickelson ECR, Zwicker JG. Diagnosis and management of developmental coordination disorder. CMAJ. 2015;187:659–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Licari M, Alvares G, Varcin K et al. Prevalence of motor difficulties in autism spectrum disorder: analysis of a population-based cohort. Autism Res. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Caeyenberghs K, Taymans T, Wilson PH, Vanderstraeten G, Hosseini H, van Waelvelde H. Neural signature of developmental coordination disorder in the structural connectome independent of comorbid autism. Dev Sci. 2016;19:599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kilroy E, Cermak SA, Aziz-Zadeh L. A review of functional and structural neurobiology of the action observation network in autism spectrum disorder and developmental coordination disorder. Brain Sci .2019;9 pii: E75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gepner B, Feron F. Autism: a world changing too fast for a mis-wired brain? Neurosci and Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:1227–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gillberg C. Deficits in attention, motor control, and perception: a brief review. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:904–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Courchesne E, Pierce K, Schumann C, et al. Mapping early brain development in autism. Neuron. 2007;56:399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Just M, Keller T, Malave V, Kana R, Varma S. Autism as a neural systems disorder: a theory of frontal-posterior underconnectivity. Neurosci and Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1292–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vasa R, Mostofsky S, Ewen J. The disrupted connectivity hypothesis of autism spectrum disorders: time for the next phase in research. Biol Psychiatr. 2016;1:245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Turner K., Frost L, Linsenbardt D, McIlroy J, Müller R. Atypically diffuse functional connectivity between caudate nuclei and cerebral cortex in autism. Behav Brain Funct. 2006;2:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nair A, Treiber J, Shukla D, Shih P, Müller R. Impaired thalamocortical connectivity in autism spectrum disorder: a study of functional and anatomical connectivity. Brain. 2013;136:1942–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Frazier T, Keshavan M, Minshew N, Hardan A. A two-year longitudinal MRI study of the corpus callosum in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:2312–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lobo MA, Harbourne RT, Dusing SC, McCoy SW. Grounding early intervention: physical therapy cannot just be about motor skills anymore. Phys Ther. 2013;93:94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Srinivasan S, Bhat A. A review of “music and movement” therapies for children with autism: embodied interventions for multisystem development. Front Integr Neurosci. 2013;7:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Srinivasan S, Eigsti I-M, Neelly L, Bhat A. The effects of embodied rhythm and robotic interventions on the spontaneous and responsive social attention patterns of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): a pilot randomized controlled trial. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;27:54–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Srinivasan S, Eigsti I-M, Gifford T, Bhat A. The effects of embodied rhythm and robotic interventions on the spontaneous and responsive verbal communication skills of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): a further outcome of a pilot randomized controlled trial. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;27:73–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Srinivasan S, Kaur M, Park I, Gifford T, Marsh K, Bhat A. The effects of rhythm and robotic interventions on the imitation/praxis, interpersonal synchrony, and motor performance of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): a pilot randomized controlled trial. Autism Res Treat. 2015;2015:736516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Srinivasan S, Park I, Neelly L, Bhat A. The effects of embodied rhythm and robotic interventions on the repetitive behaviors and affective states of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2015;18:51–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kaur M, Bhat A. Creative yoga intervention improves motor and imitation skills of children with autism spectrum disorder. Phys Ther. 2019;99:1520–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kasari C, Gulsrud AC, Wong C, Kwon S, Locke J. Randomized controlled caregiver mediated joint engagement intervention for toddlers with autism. J Autism Dev. Dis. 2010;40:1045–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Anderson L, Wilson J, Williams G. Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) as group therapy for children living with motor coordination difficulties: an integrated literature review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2017;64:170–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.