Abstract

The empower action model addresses childhood adversity as a root cause of disease by building resilience across multiple levels of influence to promote health, equity, and well-being. The model builds on the current evidence around adverse childhood experiences and merges important frameworks within key areas of public health—the socio-ecological model, protective factors, race equity and inclusion, and the life course perspective. The socio-ecological model is used as the foundation for this model to highlight the multilevel approach needed for improvement in public health. Five key principles that build on the protective factors literature are developed to be applied at each of the levels of the socio-ecological model: understanding, support, inclusion, connection, and growth. These principles are developed with actions that can be implemented across the life span. Finally, actions suggested with each principle are grounded in the tenets of race equity and inclusion, framing all actionable steps with an equity lens. This article discusses the process by which the model was developed and provides steps for states and communities to implement this tool. It also introduces efforts in a state to use this model within county coalitions through an innovative use of federal and foundation funding.

Keywords: environmental and systems change, health disparities, health promotion, partnerships/coalitions, social determinants of health, strategic planning, behavior change theory, theory, community organization, child/adolescent health

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events such as child abuse, neglect, and household dysfunctions (divorce/separation, intimate partner violence, substance misuse in the home, etc.; Felitti et. al, 1998). First studied nationally by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente, ACEs and health outcomes were found to have a dose–response relationship; the more ACEs a child experiences, the higher their risk for health and social problems in adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998). There is strong evidence to support the impact of ACEs across the life course as studies have found that ACEs are linked to risky health behaviors such as tobacco use, alcohol and substance misuse, and unprotected sex, which in turn increase risk for depression, heart disease, cancer, substance use disorders, and ultimately, premature mortality (Bethell et al., 2017; Felitti, 2009; Felitti et al., 1998). ACEs can also affect life potential such as academic achievement, employment, and wealth, all of which are also linked to health outcomes (Larkin, Shields, & Anda, 2012). The consequences of ACEs have lasting impacts on our already overburdened health care system (Srivastav, Fairbrother, & Simpson, 2017). Taken together, ACEs demonstrate the importance of taking a social determinants of health perspective—understanding that adult health and social outcomes are the product of the complex interplay of experiences in early childhood and inequities (Braveman & Barclay, 2009; Larkin et al., 2012). They also provide an important lens for advancing health promotion, by emphasizing the importance of addressing the root causes of risk behaviors before they occur.

Research on ACEs has led to an increased desire to learn about the pathway by which ACEs affect adult health. Toxic stress (i.e., severe, chronic stress resulting from prolonged exposure to ACEs and lack of buffering support from an adult) is considered the major mechanism by which ACEs affect health (Shonkoff et al., 2012). This level of stress can disrupt early childhood development, continuing to affect psychological, social, and emotional behavior across the life span (Franke, 2014; Zannas & West, 2014). Evidence on toxic stress has demonstrated that the long-term impacts of ACEs can be prevented (Ginsburg & Jablow, 2005). The brain can adapt quickly from traumatic experiences when protective factors or positive socio-environmental buffers are put into place (Afifi & Macmillan, 2011; Moore & Ramirez, 2016). These factors help children in building resilience by providing them a nurturing environment that can mitigate the effects of trauma on their life. Through increased resilience, a child’s health and well-being is likely to improve physically, emotionally, and psychologically (Ginsburg & Jablow, 2005).

The implementation of protective factors is widely recognized as an avenue to build resilience in children who are experiencing adversity, and those who may be at risk for adversity (Afifi & Macmillan, 2011; Crouch, Radcliff, Strompolis, & Srivastav, 2019). In public health, these frameworks have been endorsed as prevention strategies in the areas of mental health, violence prevention, and substance use and misuse (Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, 2014). While some qualities of resilience are innate (Ginsburg & Jablow, 2005), growing evidence in public health suggests that the building of resilience, particularly for those who have experienced childhood adversity, requires a multilevel approach that alters the child’s socio-environmental context to promote healthy development (Ellis & Dietz, 2017; Larkin et al., 2012). This notion is also consistent with the tenets of social determinants of health: To improve health trajectories, we must improve the conditions in which people are born, live, work, play, and age (CDC, 2018).

As shown in Table 1, there are five widely recognized protective factor frameworks. These include the Center for the Study of Social Policy’s (CSSP; n.d.-a, n.d.-b) Strengthening Families and Youth Thrive frameworks; Administration on Children, Youth and Families’ Protective Factors Framework (Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, 2017); Center on the Developing Child’s Factors That Predispose Children to Positive Outcomes Framework (Center on the Developing Child, n.d.); and the CDC’s Essentials for Childhood Framework (CDC, 2019). All five frameworks attempt to model the ways in which the long-term impact of ACEs and related experiences can be prevented. They promote factors that fall within three broad categories: (1) positive relationships; (2) safe, protective, and equitable environments; and (3) healthy development of social and emotional competencies (Crouch et al., 2019). These approaches have been integrated into statewide efforts such as program strategies and evaluation of outcomes (Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, 2014).

Table 1.

Protective Factors Frameworks

| Key Components | Children’s Bureau, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families’ Protective Factors Framework | Center for the Developing Child Harvard University’s Factors That Predispose Children to Positive Outcomes Framework | Center for the Study of Social Policy’s Strengthening Families: A Protective Factors Framework | Center for the Study of Social Policy’s Youth Thrive | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Essentials for Childhood Framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protective factors identified | • Self-regulation skills • Relational skills • Problem-solving skills • Involvement in positive activities • Parenting competencies • Positive peers • Caring adults • Positive community environment • Economic opportunities |

• Supportive adult–child

relationships • Sense of self-efficacy and perceived control • Opportunities to strengthen adaptive skills and self-regulatory capacities • Sources of faith, hope, and cultural traditions present |

• Parental resilience • Social connections • Knowledge of parenting • Child development • Concrete support in times of need • Social–emotional competence of children |

• Youth resilience • Social connections • Knowledge of adolescent development • Concrete supports in times of need • Cognitive and social–emotional competence |

• Safety • Stability • Nurturing • Strengthen economic supports to families • Change social norms to support parents and positive parenting • Provide quality care and education early in life • Enhance parenting skills to promote healthy child development • Intervene to lessen harms and prevent future risk |

| Across socioecological levels? | Yes | No | No | No | Some |

| Action steps? | No | No | No | No | Yes, but limited |

| Resources for implementation? | No | No | No | Technical package | Technical package |

These frameworks, however, have several key limitations (see Table 1). First, and perhaps most important, many of these frameworks do not provide specific strategies to implement the protective factors identified. For example, in CSSP’s tools and training resources, activities are centered on reinforcing the concepts associated with their protective factors framework and do not describe the actions by which these concepts can be implemented or if these concepts have been successfully implemented. Second, these frameworks focus on specific levels, such as individual and family (parental) or community and policy (societal) levels; none of the existing frameworks address protective factors across all levels of influence on health and well-being (i.e., the CDC framework focuses on community and society level, while the others focus on individual and interpersonal levels; Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, 2014). Third, these frameworks are focused on increasing well-being of specific populations, such as parents or adolescents, tailoring their frameworks toward child and family–serving professionals only. Finally, the models do not address the role of health equity in promoting child health and well-being, which is an important consideration, given the known racial disparities in access to and availability of supports (Bear, Documèt, Marshal, Voorhees, & Ricci, 2014). Thus, we propose a model that promotes resilience throughout the life span by building protective factors at multiple levels and promoting equity to meet the needs of diverse populations and communities. The model seeks to prevent poor health outcomes by addressing a root cause—ACEs—through upstream approaches that are likely to influence individual behaviors and contexts. We discuss the key theories that comprise the model; the methodology, including example strategies from community partners that assisted in the development of the model; and early lessons learned from using the model with coalitions.

The Empower Action Model

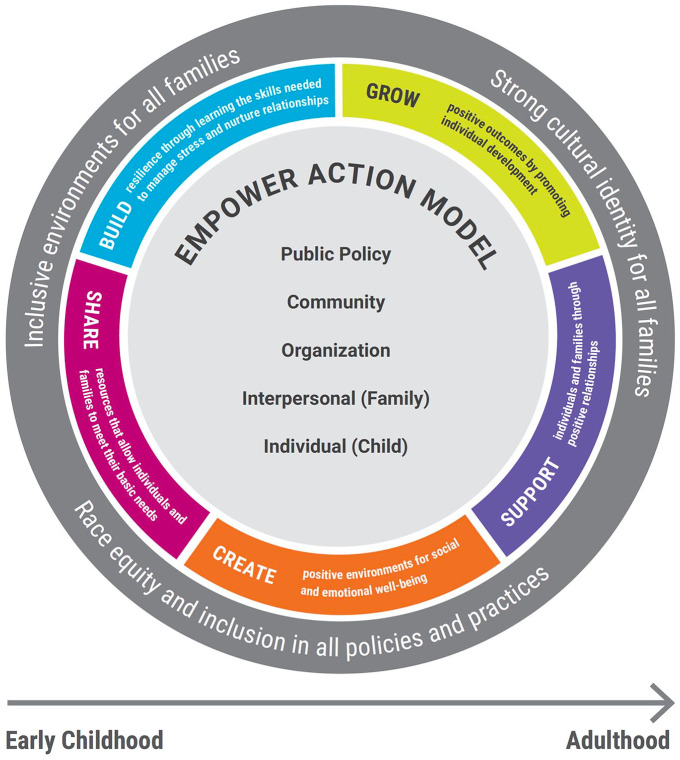

The empower action model seeks to provide tangible steps to prevent childhood adversity by implementing protective factors to build resilience and health equity across multiple levels and the life span. The model can assist families, those who serve families, communities or coalitions, and policy advocates in developing a plan for action in each of their respective areas of influence. The following sections describe the merging of key public health frameworks and concepts to develop this model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Empower Action Model

Socio-Ecological Model

The socio-ecological model recognizes the relationship among multiple levels of influence on health, which include the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy (CDC, 2015; Ungar, 2011). This model emphasizes the idea that health behaviors are influenced by social determinants, suggesting that public health prevention efforts are most effective when all these levels are addressed (CDC, 2015).

In the empower action model, the center of the model depicts the different levels of the socio-ecological model (see Figure 1). The socio-ecological model is represented by circles to emphasize the bidirectional influences that these levels have on an individual’s health and well-being and to highlight multilevel influence on behaviors and conditions. Within this model, the individual level is framed around how parents and caregivers can implement protective factors for their children, focusing on conditions that would indicate that a child has built resilience. The organizational level is situated within the context of policies and practices that can be implemented to encourage employee resilience. This level considers the growing evidence that shows how a workplace that considers the role of ACEs (“trauma-informed”) across the life span can help promote family well-being, “break the cycle” of adversity and in turn, increase work productivity and satisfaction (Wolf, Green, Nochajski, Mendel, & Kusmaul, 2014). The community level focuses on the environments in which children and families spend time; this can include neighborhoods, schools, faith-based settings, social services, and health care systems. These communities can alter conditions and practices to promote healthy outcomes. Finally, the policy level considers the political and advocacy priorities to build programs and initiatives that support child health and well-being.

Protective Factors

Five cross-cutting factors, which are developed from existing protective factor frameworks, are applied around the socio-ecological model, illustrating the overarching actions across levels that consider the social determinants of health and their role in buffering the effects of childhood adversity (see Figure 1). These were developed by looking at commonalities across the existing frameworks through a cross-systems approach. The five protective factors in this model include the following:

Build resilience through learning skills needed to manage stress and nurture children

Create positive environments for social and emotional well-being

Grow positive outcomes by promoting individual development

Share resources that allow individuals and families to meet their basic needs

Support individuals and families through positive relationships

Each factor is framed in action-oriented language to be reflective of the multilevel efforts needed to prevent ACEs. The factors are also reflective of the varying actions and conditions that may be needed to implement each factor.

Race Equity and Inclusion

Race equity and inclusion work is a growing area of interest for public health and continued social justice emphasis for community-based organizations (Griffith, Childs, Eng, & Jeffries, 2007; Griffith, Mason, et al., 2007). Race equity and inclusion efforts are underpinned by the idea that institutional racism must be dismantled by intentional policies and practices across all systems that not only promote diversity but also break down barriers to allow all individuals opportunities to meet their potential (The Annie E. Casey Foundation [AECF], 2015; Griffith, Childs, et al., 2007; Griffith, Mason, et al., 2007). Race equity and inclusion efforts require deliberate changes to individuals’ environments and systems in which they interact (Griffith, Mason, et al., 2007). This can range from addressing implicit discrimination to unequitable workplace hiring practices and differential delivery of state-level services.

Three guiding tenets of race equity and inclusion are developed and interwoven within each of the five protective factors in the empower action model. These tenets were developed based on the AECF’s community-based work on racial equity, which focuses on providing organizations with tools to assess race equity within their environment (AECF, 2015). These tenets include recognizing the need to create an inclusive environment for all families, encouraging a strong cultural identity for all families through the adoption of practices that honor their culture, and recognizing that disparities exist by demonstrating a commitment to equity and inclusion in all policies and practices (AECF, 2015). Each of the protective factors in this model and the actions associated with each factor are written with a frame of building equitable opportunities that help all individuals, including children, succeed, and of recognizing the role that race and ethnicity continue to play in accessibility of services or opportunities. For each factor, the empower action model considers the need for targeted efforts to promote equity while considering racial and cultural influences on public health practices and outcomes.

The Life Course Perspective

The life course perspective recognizes that health outcomes are the complex interplay of social determinants of health (i.e., socio-environmental context), with certain points in life serving as critical periods, or periods in which biological development is particularly influenced by life experiences and environmental influences (Braveman & Barclay, 2009). The concept of ACEs is underpinned by the idea that early childhood is a critical period for health across the life span, considering the significant growth of the brain and socio-emotional competencies (Jimenez, Wade, Lin, Morrow, & Reichman, 2016). The life course perspective also supports the importance of prevention and mitigation of existing risks to improve long-term health outcomes. The perspective in this model (demonstrated by the line going across the width of the model in Figure 1) highlights the importance of implementing the factors not only across all levels but also across the life span to create sustainable improvements in health and well-being. The life course perspective intentionally expands strategies to implement protective factors across all stages of life.

Application of the Model

The empower action model can help any individual, organization, or coalition interested in improving equity, health, and well-being in developing a plan for action in each of their respective areas of influence. Traditional players such as parents/caregivers, professionals who serve families, coalitions, and policy advocates or nontraditional players such as local businesses, human resources professionals, or law enforcement could use the model. Using the social determinants of health as its larger frame, the model recognizes that each of these actions, over time, improves outcomes for all, including children. The model also promotes cross-disciplinary collaboration by identifying strengths and weaknesses within each system or sector and emphasizing the importance of partnering with existing resources and stakeholders within the community of impact.

To assess whether each of the five protective factors have been applied effectively, the model depicts ideal conditions at each level that would exist (see Table 2). For example, if the first action of the model, create positive environments for social-emotional well-being has been applied effectively at the individual level, we might see that a child is able to manage their emotions and have positive relationships with others, while at the family level a parent or caregiver might be able to adequately foster social-emotional development. At the organizational level, the workplace would have an environment that places importance on social-emotional well-being. The community level might have child and family–serving systems with processes and resources in place that promote positive environments, which could lead to higher retention and productivity. Finally, at a policy level, child health policies would reflect the importance of safe, stable, and nurturing environments for all children. Through this multilevel approach, it is expected that the overall prevalence of childhood adversity would decrease.

Table 2.

The Empower Action Model Protective Factors and Actions

| Protective Factor | Individual Child | Interpersonal Family | Organizations | Community | Public Policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Build resilience through learning skills needed to manage stress and nurture children | Possess inner strength to positively meet challenges and overcome adversity | Manage stress and buffer its’ effects on family during tough times | Establish a system that values individual contributions, perspectives, differences, and strengths | Demonstrate that individuals are valued, honored, and supported by the community | Advocate for policies that build resilience including policies that create positive environments and provide services for health and well-being |

| Create positive environments for social and emotional well-being | Manage emotions, and relate positively to others | Foster children’s social-emotional development | Create an environment that values the importance of positive environments for social-emotional well-being | Understand the importance of positive environments for children and their social-emotional well-being | Adopt policies that promote safe, stable, and nurturing environments |

| Grow positive outcomes by promoting individual development | Understand personal growth and development | Engage in developmentally appropriate interactions with children | Assess individual contexts, development, and needs when setting expectations and career planning or training | Demonstrate importance of community involvement in individual health and well-being through the development of programs focused on prevention | Promote the notion that we are all responsible for the health and well-being of children through policies and programs that promote healthy development |

| Share resources that allow individuals and families to meet their basic needs | Identify, find, and receive support to meet basic needs | Have skills and tools to identify needs and connect to supports that strengthen your family | Create an atmosphere where employees can access resources in times of need and for self-care | Provide information and connection to services in the community to promote resilience | Promote policies that create access to resources for all |

| Support individuals and families through positive relationships | Engage with trusting, caring relationships with competent adults | Build mutual trust and support with children | Foster positive relationships within the organization and promote engagement with family and community | Promote opportunities that build healthy relationships and support for parents while empowering parents to be leaders and decision makers | Fund and endorse policies and programs that provide individuals and families with connection and support within their communities |

| Race equity and inclusion tenets | Individuals have positive cultural identity by honoring family history, race, and ethnicity | Organizational policies and practices are racially and culturally inclusive and recognize the importance of diversity in workforce and leadership | Community efforts eliminate messages that reinforce “otherness” of health outcomes while creating programs that are culturally competent and promote equity | Policy efforts work to dismantle systemic racial inequity | |

Under each level of the socio-ecological model, race equity and inclusion tenets have general conditions that should be met once all five of the factors have been implemented through actions. For example, if each of the conditions have been met for each of the five protective factors at the organizational level, all organizational policies and practices would be racially and culturally inclusive, while recognizing the importance of diversity in workforce and leadership.

The actions by which these conditions are met and how the protective factors are applied in a setting will vary. To illustrate this, and to aid in the development of the model, community partners provided example strategies for application for all the protective factors at each level of the socio-ecological model. First, using the organizational level of the model as an example, creating an environment that promotes social-emotional well-being in the workplace can be achieved in many ways, ranging from work policies (e.g., telework, flexible hours, and paid maternity/paternity leave) to providing a work environment for mindfulness and well-being (e.g., access to counseling services, wellness room, and fitness program). Similarly, on a community level, conditions that meet the definition of a positive environment look very different for a school community versus a health system. In a school system, a positive environment may be defined as a trauma-informed classroom, whereas in a health system, it may point to dual-generation practices during a well-child visit. The empower action model recognizes that there is not a one-size-fits-all approach and provides an opportunity for various actions to be considered that promote a contextualized plan for each respective group or community applying the model. This is in turn can also help inform appropriate interventions or supports needed (e.g., evidence-based parenting programs, school-based mental health programs, employee assistance program, cross-sector referral system, child care tax credit).

Method

The empower action model was developed using a three-pronged approach. First, we used 3 years of ACE training evaluation data (n = 909) to identify needs for ACE prevention tools and resources. Authors reviewed the open-ended items within these surveys that asked training participants to provide feedback on what they would like to see in the future. The major theme that emerged was conceptualized by the authors as “so what?” The evaluations demonstrated that training participants are very comfortable with the science supporting ACEs but are unsure what to do about it.

Then, we conducted a comprehensive literature review of existing frameworks to identify gaps and limitations in ACEs prevention, as well as to determine the key theories that provide the foundation for ACEs as a public health issue. Using PubMed, SAGE Reference Online, and a general Web search, the authors searched for articles that answered three major questions: (1) How do you prevent ACEs? (2) How are protective factors conceptualized? (3) What tools/models promote action to build resilience and well-being? The following keywords were used: ACEs, prevention, community resilience, protective factors, childhood trauma, prevention model/framework, and health equity. Studies, reports, and tools that resulted from this search were included in the literature review based on their abstract or executive summary.

Last, we used focus groups of internal and external stakeholders to ask for feedback on various iterations of the model. These stakeholders (n = 37) included senior program and communications staff within the agency, child-serving professionals, and child health researchers and advocates. A total of five focus groups were conducted over a year’s time as the model was developed and vetted. All participants were given an overview of the demonstrated need for an action-oriented prevention framework for ACEs using the literature review. At the beginning of the development process, focus group participants were asked about their definitions of ACEs, resilience, well-being, race equity, and protective factors. As the model was developed, they were asked to provide feedback on the five actionable protective factors and the key theories that encompass the model. They were also asked for their perspectives on the optimal conditions that would exist at each level of the socio-ecological model if resilience and well-being were present: Some of these conditions are presented above. In the final model vetting process, participants were asked about the potential application of the model in their own work, including ease of use, clarity of concepts, and model visualization.

Discussion

Advocates, leaders, and professionals in the child health and well-being space have identified a need for concrete steps for building resilience to prevent ACEs. Current frameworks focused on ACEs fall short of including a multilevel approach, considering the role of health equity in well-being, and providing concrete, tangible steps for implementation across the life span. The empower action model is among the first to provide actionable steps to promote well-being by building resilience in all individuals including children and families by bringing together key frameworks and theories in public health that promote upstream approaches to health. This model can be especially useful for states, communities, and organizations seeking to build protective factors and promote resilience among their respective populations as a way to address the root cause of many different poor health outcomes. This can range from employees within an organization to larger systems such as health care or social services. The model can also serve as a foundation for community-based impact, encouraging cross-sector collaboration and a shift in social norms.

The empower action model was developed as a part of the South Carolina ACE Initiative, which is led by the Children’s Trust of South Carolina. A component of the initiative is focused on community-based efforts to prevent and mitigate the effects of ACEs. Children’s Trust of South Carolina is using Community-Based Child Abuse Prevention funding from the federal government and a statewide foundation to support three existing county coalitions’ use of the empower action model. These coalitions are working at various socio-ecological levels, ranging from parents working to improve their own home conditions to public health professionals advocating for policy change. All the identified coalitions are using the model to help assess their capacity and capability, while serving as a guide for their action plans. Future work with the model will focus on evaluating the process of applying the model and associated outcomes within different settings and contexts.

Although application of the empower action model is currently under way, it was important for us to share this framework with other public health professionals as they navigate translating current ACEs research into action. There are some early lessons learned from working with coalitions that are important to consider for those interested in using the model. It should be noted, however, that a coalition-based approach is not the only way to apply the empower action model but can be a way to encourage multilevel impact on health and well-being (Janosky et al., 2013). First, we found that a community coach, or facilitator, is key to implementing the model. The coach can help guide the collective impact or other identified selection process, ensuring that all components of the model are being applied effectively, and help maximize the use of a coalition-based approach. Thus, we are currently working on developing facilitation tools for organizations and for communities outside of South Carolina to use the empower action model. Next, to promote authentic community voice, we believe there should be an intentional process of selecting the stakeholders at the table to lead the use of the empower action model. This ensures that the emphasis on racial equity and multi-level, context-specific approaches is not lost. We have found the collective impact approach (Bradley, Chibber, Cozier, Meulen, & Ayres-Griffin, 2017) to be beneficial for the process of selection within the three coalitions that are currently using the model. Additionally, we have learned that it is important to engage in a formal readiness process prior to the development of an action plan. Using the collective impact approach, all three coalitions have engaged in data-driven decision making, looking at trends and patterns in state- and county-level data (e.g., ACEs, child and family well-being, child maltreatment, school performance). This has assisted in understanding current strengths and opportunities for prevention, while helping highlight key priorities within the action plan developed through the model. Using community-focused, data-driven decision-making methods (e.g., data walks, community conversations, formal facilitated discussions) can be beneficial for setting the foundation for a common vision and goal around the prevention of ACEs.

Finally, ACEs are a complex issue, and change through the application of the model will take time, often more time than may be allotted through traditional funding mechanisms. We have found that it is important to recognize the “small wins” and incremental changes occurring in community and organizational practices along the way, such as increased interagency collaboration, shifts in practitioner mind-sets while working with children and families, better use and understanding of data, and engagement of nontraditional stakeholders. We have also found that blending and braiding of funding mechanisms (e.g., federal and foundation funding) to support different aspects of coalition work can more readily adapt to the slower pace of coalition-based work and better promote meaningful changes and sustainability.

Conclusion

The empower action model translates existing ACEs research into action by drawing on key theories that have shaped the field of ACEs since the influential ACE Study in 1997. This model is especially timely given the momentum around childhood trauma and ACEs in public health. There is a growing emphasis on adversity as a root cause of many preventable diseases and outcomes and an increased focus on using a cross-system approach that addresses the intergenerational cycle of adversity (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011; Metzler, Merrick, Klevens, Ports, & Ford, 2017; Wickrama, Conger, & Abraham, 2005). This is demonstrated through the growing number of local, state, and national initiatives around “trauma-informed” communities, seeking to improve well-being through increased public awareness of ACEs and systems-level change (Ko et al., 2008; Leitch, 2017; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017). The work centered on trauma-informed communities varies, and the definition of being trauma-informed can have varying definitions given that each community has different needs and capacities. Thus, it is especially important to have a practice-based, action-oriented model, such as the empower action model, that can be applied in diverse settings and populations while balancing the need for clear, attainable steps and flexible approaches to resilience and well-being.

Public health efforts that address the social determinants of health have the greatest potential to develop a thriving society (Baker, Metzler, & Galea, 2005; Braveman, 2006). The research on ACEs provides another lens as to why these upstream approaches are so important to preventing poor health outcomes and to improving individual and community well-being (Baker et al., 2005; Braveman, 2006; Larkin et al., 2012). Programs and strategies should use a multilevel approach that promotes health equity across the life span by implementing factors that develop environments and contexts conducive to optimal health for all children and families.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Aditi Srivastav  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0816-8612

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0816-8612

References

- Afifi T. O., Macmillan H. L. (2011). Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 56, 266-272. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2015). Race equity and inclusion action guide. Retrieved from http://www.aecf.org/resources/race-equity-and-inclusion-action-guide/

- Baker E. A., Metzler M. M., Galea S. (2005). Addressing social determinants of health inequities: Learning from doing. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 553-555. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.061812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear T., Documèt P., Marshal M., Voorhees R., Ricci E. (2014, November). Childhood adversity: A social determinant of health and inequity over the lifespan and across generations. Paper presented at the 142nd annual meeting and exposition of the American Public Health Association, New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin L. J., Appleyard K., Dodge K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82, 162-176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell C. D., Solloway M. R., Guinosso S., Hassink S., Srivastav A., Ford D., Simpson L. A. (2017). Prioritizing possibilities for child and family health: An agenda to address adverse childhood experiences and foster the social and emotional roots of well-being in pediatrics. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7 Suppl.), S36-S50. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K., Chibber K. S., Cozier N., Meulen P. V., Ayres-Griffin C. (2017). Building healthy start grantees’ capacity to achieve collective impact: Lessons from the field. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(Suppl. 1), 32-39. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2373-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. (2006). Health disparities and health equity: Concepts and measurement. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 167-194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P., Barclay C. (2009). Health disparities beginning in childhood: A life-course perspective. Pediatrics, 124(Suppl. 3), S163-S175. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study of Social Policy. (n.d.-a). Strengthening families™: A protective factors framework. Retrieved from https://cssp.org/our-work/project/strengthening-families/

- Center for the Study of Social Policy. (n.d.-b). Youth thrive™. Retrieved from https://cssp.org/our-work/project/youth-thrive/

- Center on the Developing Child. (n.d.). Toxic stress derails healthy development. Retrieved from http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/toxic-stress-derails-healthy-development/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). The social-ecological model: A framework for prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Social determinants of health: Know what affects health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Essentials for childhood: Creating safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/essentials.html

- Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families. (2014). Protective factors approaches in child welfare (Issue brief). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/protective_factors.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families. (2017). Protective factors to promote well-being. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/promoting/protectfactors/

- Crouch E., Radcliff E., Strompolis M., Srivastav A. (2019). Safe, stable, and nurtured: Protective factors against poor physical and mental health outcomes following exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 12, 165-173. doi: 10.1007/s40653-018-0217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis W. R., Dietz W. H. (2017). A new framework for addressing adverse childhood and community experiences: The building community resilience model. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7 Suppl.), S86-S93. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V. J. (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Academic Pediatrics, 9, 131-132. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V. J., Anda R. F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D. F., Spitz A. M., Edwards V., . . . Marks J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke H. A. (2014). Toxic stress: Effects, prevention and treatment. Children, 1, 390-402. doi: 10.3390/children1030390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg K. R., Jablow M. M. (2005). Building resilience in children and teens (2nd ed.). Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Childs E. L., Eng E., Jeffries V. (2007). Racism in organizations: the case of a county public health department. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 287-302. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Mason M., Yonas M., Eng E., Jeffries V., Plihcik S., Parks B. (2007). Dismantling institutional racism: Theory and action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 381-392. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9117-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janosky J. E., Armoutliev E. M., Benipal A., Kingsbury D., Teller J. L., Snyder K. L., Riley P. (2013). Coalitions for impacting the health of a community: The Summit County, Ohio, experience. Population Health Management, 16, 246-254. doi: 10.1089/pop.2012.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez M. E., Wade R., Lin Y., Morrow L. M., Reichman N. E. (2016). Adverse experiences in early childhood and kindergarten outcomes. Pediatrics, 137(2), e20151839. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko S. D., Ford J., Kassam-Adams N., Berkowitz S., Wilson C., Wong M., . . . Layne C. (2008). Creating trauma-informed systems: child welfare, education, first responders, health care, juvenile justice. Professional Psychology, 39, 396-404. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.4.396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin H., Shields J. J., Anda R. F. (2012). The health and social consequences of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) across the lifespan: An introduction to prevention and intervention in the community. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 40, 263-270. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.707439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch L. (2017). Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model. Health & Justice, 5, 5. doi: 10.1186/s40352-017-0050-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler M., Merrick M. T., Klevens J., Ports K. A., Ford D. C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: Shifting the narrative. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 141-149. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. A., Ramirez A. N. (2016). Adverse childhood experience and adolescent well-being: Do protective factors matter? Child Indicators Research, 9, 299-316. doi: 10.1007/s12187-015-9324-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J. P., Garner A. S., Siegel B. S., Dobbins M. I., Earls M. F., Garner A. S., . . . Wood D. L. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232-e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastav A., Fairbrother G., Simpson L. A. (2017). Addressing adverse childhood experiences through the Affordable Care Act: Promising advances and missed opportunities. Academic Pediatrics, 17(7 Suppl.), S136-S143. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2017.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Spotlights on six trauma-informed resilient communities. Retrieved from https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma17-5014.pdf

- Ungar M. (2011). The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice. Berlin, Germany Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama K. A., Conger R. D., Abraham W. T. (2005). Early adversity and later health: The intergenerational transmission of adversity through mental disorder and physical illness. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(Special Issue 2), S125-S129. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.Special_Issue_2.S125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf M. R., Green S. A., Nochajski T. H., Mendel W. E., Kusmaul N. S. (2014). “We’re Civil Servants”: The status of trauma-informed care in the community. Journal of Social Service Research, 40, 111-120. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2013.845131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zannas A. S., West A. E. (2014). Epigenetics and the regulation of stress vulnerability and resilience. Neuroscience, 264, 157-170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]