SUMMARY

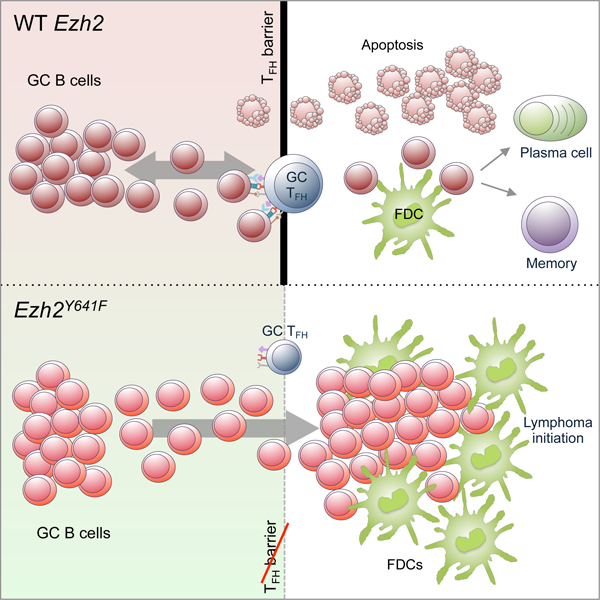

Follicular lymphomas (FL) are slow-growing, indolent tumors containing extensive follicular dendritic cell (FDC) networks and recurrent EZH2 gain-of-function mutations. Paradoxically, FLs originate from highly proliferative germinal center (GC) B cells with proliferation strictly dependent on interactions with T follicular helper cells. Herein, we show that EZH2 mutations initiate FL by attenuating GC B cell requirement for T cell help and driving slow expansion of GC centrocytes that become enmeshed with and dependent on FDCs. By impairing T cell help, mutant EZH2 prevents induction of proliferative MYC programs. Thus, EZH2 mutation fosters malignant transformation by epigenetically reprograming B cells to form an aberrant immunological niche that reflects characteristic features of human FLs, explaining how indolent tumors arise from GC B cells.

Keywords: Follicular lymphoma, EZH2, germinal center, immune microenvironment, epigenetic dysregulation

Graphical Abstract

IN BRIEF

Béguelin et al. show that mutant EZH2 epigenetically reprograms germinal center B cells to alter their interactions with T follicular helper cells and follicular dendritic cells, facilitating malignant transformation and establishing characteristic features of the follicular lymphoma immunological niche.

INTRODUCTION

Follicular lymphomas (FLs) are the second most common form of B cell lymphoma and generally present as indolent and relatively slow growing tumors (Scott and Gascoyne, 2014). In spite of this, most FLs are incurable and eventually transform into aggressive and refractory high-grade lymphomas (Lossos and Gascoyne, 2011). FLs originate from germinal center (GC) B cells, which are among the most rapidly dividing cell types. GCs are transient structures within which B cells undergo massive proliferation and somatic hypermutation of their immunoglobulin loci. The densely packed region of proliferating B cells (named centroblasts) is called the GC dark zone (DZ) (Mlynarczyk et al., 2019; Victora and Nussenzweig, 2012). After several rounds of division, GC B cells stop proliferating to become centrocytes that form the GC “light zone” (LZ) together with T follicular helper (Tfh) and follicular dendritic cells (FDCs). Within the LZ, GC B cells compete to interact with limiting numbers of Tfh cells, based on the affinity of their B cell receptor (i.e., immunoglobulin genes) for antigen (Mesin et al., 2016). Most GC B cells fail to receive T cell help and undergo apoptosis. The few that receive T cell help either return to the DZ for additional rounds of proliferation and mutagenesis (a MYC-dependent process called GC recycling), or exit the GC reaction to form antibody-secreting plasma cells (Mesin et al., 2016).

The typical histological appearance of low-grade FL is that of enlarged lymphoid follicles containing aberrant centrocytes, highly enmeshed within a network of FDC processes and variable numbers of T cells (Lossos and Gascoyne, 2011). It is not known how these aberrant lymphoid follicles evolve from normal GCs. One especially puzzling aspect of FL pathogenesis is the apparent paradox of how highly proliferative GC B cells could transform into indolent and slowly proliferative tumors. It is also notable that even though centrocytes are highly T cell dependent, FLs are generally resistant to T cell augmentation therapies such as checkpoint inhibitors (Kline et al., 2019). One source of clues that could help to address such questions are the genetic lesions that occur in FL. For example, gain-of-function mutations of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase occur in 25–30% of FL patients, as well as in GCB-like diffuse large B cell lymphomas (Bodor et al., 2013; Chapuy et al., 2018; Morin et al., 2010; Okosun et al., 2014; Reddy et al., 2017; Schmitz et al., 2018). The vast majority of these alleles encode a single amino acid substitution affecting the Y641 residue within the EZH2 catalytic domain. EZH2Y641 mutants are far more efficient than WT enzyme in converting H3K27me2 to H3K27me3 (Sneeringer et al., 2010; Yap et al., 2011). Hence, EZH2Y641 mutant cell lines or GC B cells manifest increased abundance of the H3K27me3 repressive histone mark (Beguelin et al., 2013; Beguelin et al., 2016; Souroullas et al., 2016).

Under normal conditions, EZH2 is upregulated in GC B cells and required for GC formation (Beguelin et al., 2013; Caganova et al., 2013; Velichutina et al., 2010). Critical functions of WT EZH2 in GC B cells include repression of cell cycle checkpoint and differentiation genes to support centroblast proliferation and prevent premature plasma cell differentiation (Beguelin et al., 2017). These repressive effects of EZH2 resolve as B cells exit the GC reaction. Exposure of EZH2 mutant or WT diffuse large B cell lymphomas to EZH2 inhibitors leads to proliferation arrest and plasma cell differentiation (Beguelin et al., 2013; Brach et al., 2017; Knutson et al., 2012; McCabe et al., 2012b), which raises the question of whether EZH2 mutation has any additional qualitatively distinct function in lymphomagenesis beyond simply being a more potent version of the WT enzyme. In fact, the effect of EZH2 mutation on malignant transformation of GC B cells has not yet been fully explored. Herein, we sought to address some of these fundamental FL pathogenesis questions through in-depth study of the humoral immune response in mice with Ezh2 mutant GC B cells.

RESULTS

Mutant Ezh2 provides a fitness advantage to GC B cells

Although Ezh2Y641F induces formation of larger than normal GCs, it is not known whether it confers a selective advantage over WT GC B cells under physiologic conditions in the same microenvironment, which is likely critical for initiating lymphomagenesis. For this we performed mixed chimera bone marrow transplantation experiments using the Cγ1-cre strain (Casola et al., 2006) to drive GC specific expression of Ezh2Y641F from the endogenous Ezh2 locus (Beguelin et al., 2016) (Figure S1A–S1D). As WT bone marrow donor, we used Cγ1-cre strain carrying Ptprca (CD45.1), whereas the Ezh2(Y641F)fl/WT;Cγ1-cre strain (Ezh2Y641F from hereon) expresses the Ptprcb allele (CD45.2). Cγ1-cre (WT Ezh2) bone marrow was mixed with Ezh2Y641F at different ratios and engrafted into Rag1 KO host mice. Upon engraftment, mice were immunized with the T cell dependent antigen sheep red blood cells (SRBC) to induce GCs, and euthanized at 8 days, when the GC reaction is at its peak (Figure 1A).

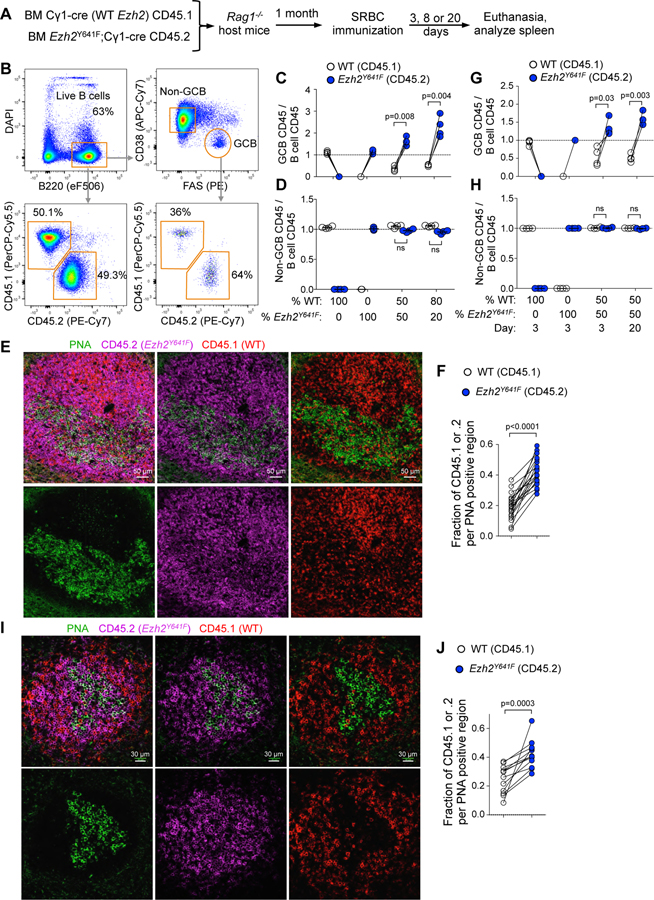

Figure 1. Mutant Ezh2 provides an advantage to activated B cells in expanding the GC reaction.

A. WT bone marrow (BM) (CD45.1) mixed with Ezh2Y641F BM (CD45.2) was injected into Rag1-/- mice, SRBC-immunized and euthanized 3, 8 or 20 days later.

B. Gating strategy of splenocytes of one representative sample.

C. Flow cytometry data of mice immunized for 8 days was analyzed by normalizing the percentage of CD45.1+ GC B cells (CD38-FAS+) to their parental CD45.1+ B cells (B220+DAPI-), and equivalent normalization with CD45.2+ populations. Each pair of connected dots represents a mouse (n=4); paired t tests.

D. Analysis of non-GC B cells (CD38+FAS-) at day 8 was done as in C.

E. IF confocal microscopy images of chimeric splenic GCs at day 8 post-SRBC.

F. Quantification of PNA fluorescence was overlapped with CD45.1 and CD45.2 shown in E (and non-shown images), each pair of connected dots representing a single GC; paired t tests.

G-H. Analysis of GC B cells (G) and non-GC B cells (H) at days 3 and 20 post-SRBC were done as in C (n=4 per group).

I. IF confocal microscopy images of chimeric splenic GCs at day 3 post-SRBC.

J. Quantification of GCs shown in I (and non-shown images) was done as in F.

Results at day 8 are representative of 3 independent experiments.

See also Figure S1.

Normalizing the percentage of CD45.1+ or CD45.2+ GC B cells to their respective total B cell populations by flow cytometry (Figure 1B) indicated that mutant Ezh2 provides a competitive advantage in the GC reaction (Figure 1C), that was even greater when the initial ratio of transplanted cells was skewed towards the WT (Figure 1C). In control experiments, both WT and Ezh2Y641F form GCs (Figure 1C) without altering non-GC B cell ratios (Figure 1D). Confocal microscopy confirmed significantly higher overlap of the GC marker PNA with CD45.2 (Ezh2Y641F) than CD45.1 (WT Ezh2; Figure 1E and 1F). We also examined early GCs (day 3), and resolving GCs (20 days), and observed similar Ezh2Y641F dominance at both time points (Figure 1G–1J). Hence, mutant Ezh2 provides a selective advantage to GC B cells throughout the duration of the GC reaction.

Mutant Ezh2 skews GC polarity to yield expansion of the centrocyte population

Given that EZH2 normally represses cell cycle checkpoint genes to enable DZ proliferation (Beguelin et al., 2013; Beguelin et al., 2017), we predicted that Ezh2Y641F competitive advantage likely reflects expansion of the DZ by exaggerating this effect. Yet surprisingly, analysis of splenic GCs showed an increased proportion of centrocytes, shifting the typical DZ:LZ ratio from ~60:30 (Victora et al., 2010) to ~50:40 (Figure 2A–2D). This was further confirmed by confocal microscopy using IgD (B cell follicles), PNA (GC B cells) and CD35 to mark FDCs (a landmark for the LZ niche), revealing clear LZ expansion with increased abundance of GC B cells interdigitated among FDCs (Figures 2E–2G and S2A). We observed a similar effect by crossing Ezh2Y641F and Cγ1-cre (WT Ezh2) mice with the R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP reporter strain to induce YFP expression in GC B cells (Figures 2H–2J and S2B–S2D). Similar results were observed in lymph nodes of NP-OVA immunized mice (data not shown).

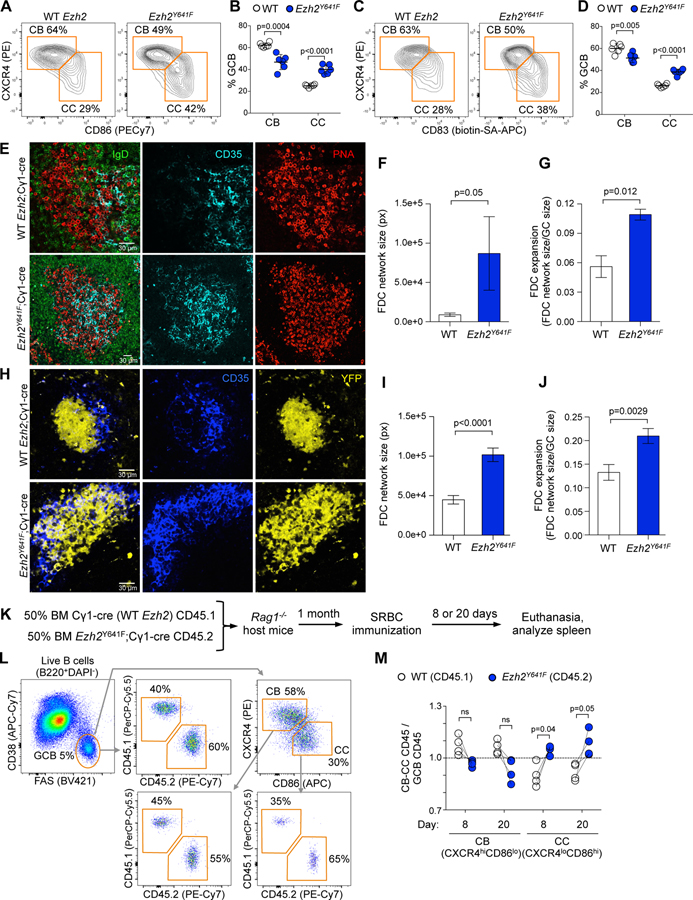

Figure 2. Mutant Ezh2 induces LZ expansion.

A. Ezh2Y641F and WT mice were SRBC-immunized for 8 days and spleens analyzed by flow cytometry. Centroblasts (CB) and centrocytes (CC) were gated from GC B cells.

B. Percentage of CBs and CCs shown in A. Each dot represents a mouse (n=6), mean ± SEM; unpaired t tests.

C. Flow cytometry data of splenocytes shown in A, using a different CC marker.

D. Percentage of CBs and CCs shown in C. Data shown as in B.

E. IF confocal microscopy images of splenic GCs at day 8 post-SRBC.

F-G. Quantification of FDC network size (F) and expansion (G) from IF images from 3 WT and 3 Ezh2Y641F; mean ± SEM; unpaired t tests.

H. IF confocal microscopy images of YFP splenic GCs at day 8 post-SRBC. Mice were injected with anti CD35-BV421 to mark FDCs.

I-J. Quantification of FDC network size (I) and expansion (J) from IF images from 5 YFP;Ezh2Y641F and 5 YFP;Cγ1-cre mice; mean ± SEM; unpaired t tests.

K. WT BM (CD45.1) mixed with Ezh2Y641F BM (CD45.2) was injected into Rag1-/- mice, SRBC-immunized and euthanized 8 or 20 days later.

L. Gating strategy of splenocytes of one representative sample.

M. Flow cytometry data was analyzed by normalizing the percentage of CD45.1+ CBs (CXCR4hiCD86lo) and CCs (CXCR4loCD86hi) to their parental CD45.1+ GC B cells (CD38-FAS+), and equivalent normalization with CD45.2+ populations. Each pair of connected dots represents a mouse (n=4); paired t tests.

Results representative of 3 to 4 experiments.

See also Figure S2.

To determine whether Ezh2Y641F still disrupts GC polarity when competing with WT Ezh2 GC B cells in the same microenvironment, we explored DZ/LZ distribution in mixed chimeras (Figure 2K and 2L). This system confirmed significant increase of centrocytes 8 and 20 days after immunization in Ezh2Y641F, with proportionately fewer centroblasts (Figure 2M). Altogether, these results show that Ezh2 gain-of-function mutations expand GCs by increasing their centrocyte subpopulation.

LZ expansion is not due to differentiation blockade

Given that EZH2 inhibitors primarily cause induction of plasma cell differentiation and proliferation arrest in lymphoma cells (Beguelin et al., 2013; Knutson et al., 2012; McCabe et al., 2012b), we reasoned that LZ expansion might reflect impaired GC exit and differentiation. This was tested by immunizing Ezh2Y641F or WT mice with NP-OVA (Figure S2E), and measuring secretion of high and low affinity NP-specific immunoglobulins by antibody secreting cells emerging from the GC reaction. Contrary to expectations, Ezh2Y641F B cells generated similar frequency of NP+ specific IgG1 and IgM splenocytes as compared to WT GC B cells (Figure S2F). NP+ specific plasma cells or memory B cell were also generated at similar abundance in Ezh2Y641F vs. WT mice (Figure S2G–S2J). Ezh2Y641F GC B cells yielded increased, rather than decreased, output of splenic memory B cells (Figure S2K and S2L) as compared to WT controls in the mixed chimera setting. However, the abundance of memory cells was actually proportional to GC B cells (Figure S2M), suggesting that there was no net perturbation in GC exit or terminal differentiation.

We then investigated whether there was any perturbation of fully differentiated, long-lived plasma cells in Ezh2Y641F or WT mice (Figure S2N). There was no impairment of IgG1 or IgM secretion from long-lived, high affinity (post-GC) plasma cells (Figure S2O), nor any loss of high-affinity, post-GC plasma cells and long lived plasma cells (Figure S2P and S2Q). There was no reduction in titers or ratios of antigen specific low or high affinity immunoglobulins (Figure S2R and S2S). These results were further confirmed in R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP;Ezh2Y641F mice, which manifested a slight increase in post-GC memory B cells and no significant change in plasma cells or plasmablasts in Ezh2Y641F mice (Figure S2T–S2W). Taken together, these results show that Ezh2Y641F induced expansion of the GC LZ is not explained by differentiation blockade.

Ezh2 mutation causes aberrant proliferation of LZ centrocytes

Since LZ expansion by Ezh2 mutation is not due to differentiation blockade, we next explored if this effect is due to aberrant proliferation. Analysis of splenocytes of mixed chimera mice after immunization with SRBC revealed significant increase in the fraction of Ki67+ Ezh2Y641F centrocytes (Figure S3A and S3B), with a much smaller effect in centroblasts (Figure S3B).

To more precisely characterize this effect we crossed Ezh2Y641F mice with R26-Fucci2aR strain (Mort et al., 2014), encoding reporters that fluoresce red during G1 (mCherry-hCdt1) and green during S/G2/M phases (mVenus-hGem). Flow cytometry revealed that many GC B cells were in S/G2/M phases (mCherry-) while naive B cells were in G1/G0 (mCherry+mVenus-, Figure S3C and S3D). We validated these results by evaluating DNA content in fixed R26-Fucci2aR splenocytes (Figure S3E). We then immunized R26-Fucci2aR;Ezh2Y641F and R26-Fucci2aR;Cγ1-cre control mice with SRBC and examined the cell cycle state of GC B cells in spleens 8 days later. We observed a significantly increased S/G2/M and decreased G1 phase GC B cells in R26-Fucci2aR;Ezh2Y641F, but no cell cycle changes in non-GC B cells (Figure S3F). In normal GC B cells most centrocytes were in G1 (Figure 3A) and centroblasts in S/G2/M phases, as expected (Figure S3G). However, Ezh2Y641F mice manifested significant increase in G2/M and reduction in G1 phase centrocytes (Figure 3B and 3C). In contrast there were no differences in the most abundant fractions of centroblasts, (G1 and late M phase, Figure S3G–S3I). Finally, visualization of splenic GCs revealed abundant mVenus+ centrocytes enmeshed within the network of FDCs (Figures 3D, 3E and S3J). In contrast Ezh2 WT GCs, contained much fewer dividing LZ centrocytes and instead the mVenus+ signal was mainly present in the DZ.

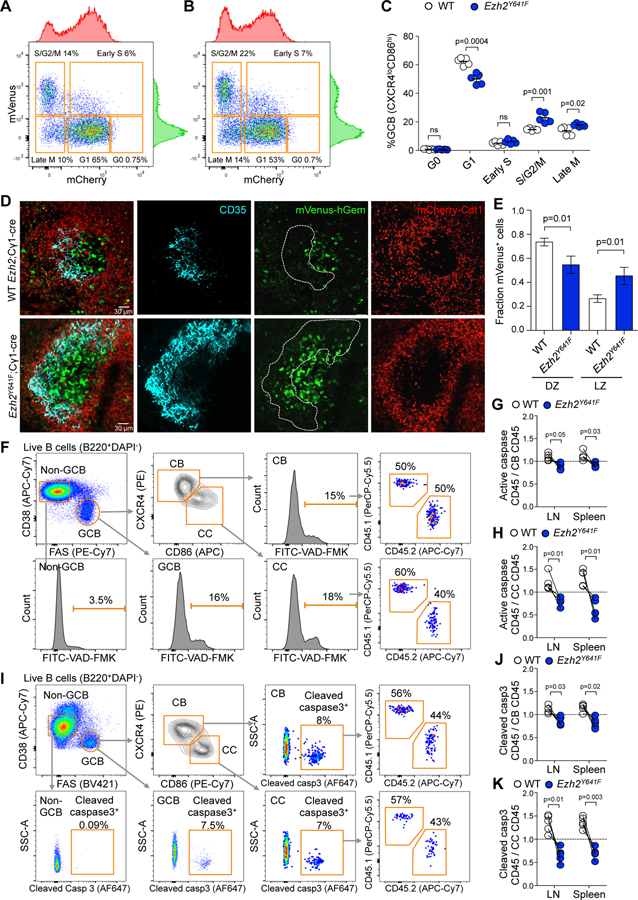

Figure 3. Ezh2 mutation causes aberrant proliferation and less apoptosis in the LZ.

A-B. Flow cytometry plots of splenic CCs (CXCR4loCD86hi) of R26-Fucci2aR;Cγ1-cre (A) and R26-Fucci2aR;Ezh2Y641F (B) mice immunized with SRBC for 8 days.

C. Percentage of CCs shown in A and B at different cell cycle phases. Each dot represents a mouse (n=5), mean ± SEM; unpaired t tests.

D. IF confocal microscopy images of R26-Fucci2aR splenic GCs at day 8 post-SRBC. Mice were injected with anti CD35-BV421 to mark FDCs.

E. Quantification of proliferating mVenus+ cells in images taken from 4 R26-Fucci2aR;Cγ1-cre and 4 R26-Fucci2aR;Ezh2Y641F mice; mean ± SEM; unpaired t tests.

F. Gating strategy of lymph node cells of mixed chimera mice generated as in Figure 2K and immunized with NP-OVA for 8 days. Apoptosis was assessed using VAD-FMK pan-caspase inhibitor.

G-H. The percentage of CD45.1+ VAD-FMK+ splenocytes and lymph node (LN) cells was normalized to their parental CD45.1+ CBs (G) and CCs (H), and equivalent normalization with CD45.2+ populations, gated as shown in F. Each pair of connected dots represents a mouse (n=4); paired t tests.

I. Gating strategy of splenocytes of mixed chimera mice immunized with NP-OVA for 8 days. Apoptosis was assessed using an anti-cleaved caspase 3 antibody.

J-K. The percentages of CD45+ cleaved caspase 3+ cells shown in I were normalized to parental CBs (J) and CCs (K), and quantified as in G-H; n=4, paired t tests.

Results representative of 3 experiments.

See also Figure S3.

Ezh2 mutant centrocytes might also accumulate in the LZ if they did not undergo apoptosis at the same rate as WT cells. To investigate this possibility, we immunized Ezh2Y641F/WT mixed chimera mice with SRBC and extracted spleens and inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes. We observed significant reduction in the abundance of apoptotic splenic GC B cells in Ezh2Y641F mice (Figure S3K and S3L). There was particularly robust reduction of apoptosis in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes, and smaller but still significant reduction in Ezh2Y641F centroblasts (Figure 3F–3K). Collectively, these data show that Ezh2 mutation drives GC hyperplasia through enhanced proliferation and survival of centrocytes.

Ezh2Y641F centrocytes fail to re-enter the DZ

The preceding data indicate that Ezh2Y641F induces LZ hyperplasia, with proportional increase in plasma and memory cells, but not DZ cells. This was perplexing, since centrocytes typically re-enter the DZ after T cell selection to undergo additional rounds of proliferation and somatic hypermutation (Oprea and Perelson, 1997; Victora et al., 2010) and theoretically should drive proportional increase in centroblasts. Considering that GC B cells are a complex mixture of subpopulations undergoing several transitional phases (Mesin et al., 2016), we performed droplet-based single cell RNA-seq to define how mutant Ezh2 affects these states. We used the YFP Cre reporter system to avoid sorting based on specific surface markers of pre-defined populations, and isolated YFP+IgD-splenocytes (GC B cells and post-GC B cells) from immunized R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP;Ezh2Y641F and R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP;Cγ1-cre control mice. Using UMAP we identified two main clusters of cells (Figure S4A and S4B) corresponding to GC B cells and plasma cells (Figure S4C), based on projection of plasma cell signatures and expression of specific genes (Figure S4D). After normalization for total number of analyzed cells, the abundance of plasma cells was slightly increased in Ezh2Y641F mice (Figure S4E).

Focusing on the GC B cell population, we next used graph-based clustering and K nearest neighbor analysis to assign cells to clusters with distinct expression profiles, yielding eight discrete clusters of cells (Figure 4A). By projecting GC-associated signatures on to these clusters, we were able to determine that clusters 1 and 2 correspond to centroblasts, clusters 3 and 4 correspond to cells transitioning from DZ to LZ, cluster 5 corresponds to centrocytes, cluster 6 represents putative mature centrocytes transitioning to memory B cells, whereas clusters 7 and 8 manifested the canonical signature of centrocytes that are recycling back to form DZ centroblasts, which typically manifest transient upregulation of Myc (Figure 4B). True to their recycling nature, the Myc positive cluster created a branch between centroblasts and centrocytes, reflecting the transition of these cells from the LZ to DZ. Projection of genes characteristic of these various subpopulations were accordingly enriched for expression in these respective clusters including Mki67, Ccnb1 and Ccnb2 for DZ, Cd83 for LZ, Myc for recycling cells, and Ccr6, Cd38 and S1pr1 for pre-memory and memory cells (Figure 4C).

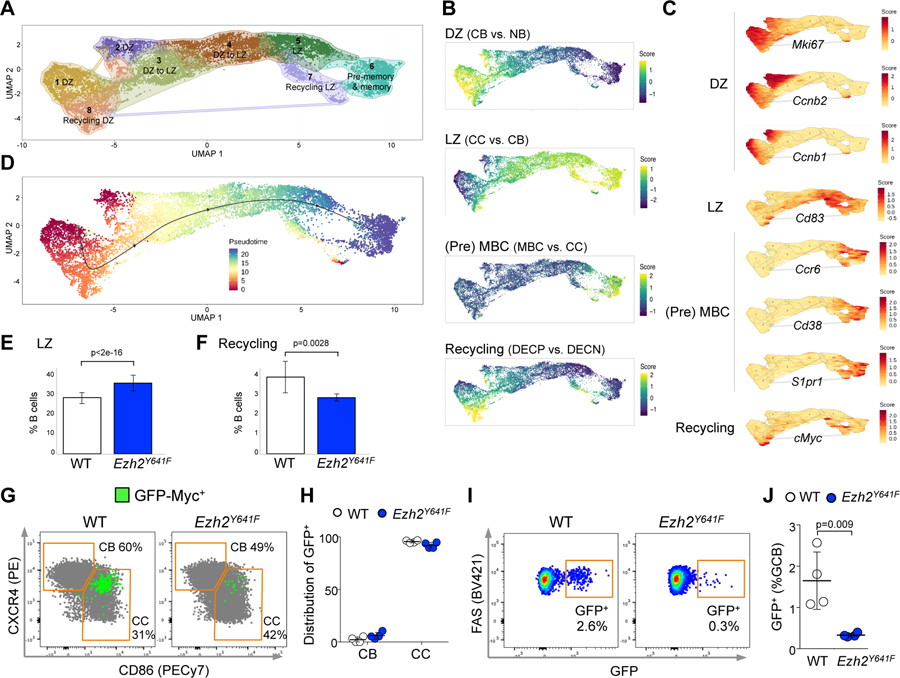

Figure 4. Mutant Ezh2 centrocytes fail to re-enter the DZ.

A. YFP+IgD- splenocytes sorted from 3 YFP;Ezh2Y641F and 3 YFP;Cγ1-cre mice immunized with SRBC for 8 days were subjected to single cell RNA-seq. Dimensionality reduction with UMAP was performed on normalized gene expression values, using graph based clustering and K nearest neighbor analysis to assign cells to clusters with distinct expression profiles.

B. Mature B cell signatures were projected on clusters defined in A. MBC: memory B cell. DECP are positively selected GC B cells (Ersching et al., 2017).

C. Specific gene expressions were projected on clusters from A. D. Gene expression profiles were organized into a pseudotime vector by Slingshot.

E-F. After normalization for total number of analyzed cells, the abundance of Ezh2Y641F and WT was calculated for CC (LZ) (E) and recycling cells (F), based on the projected signature score from (B); data are mean ± SE (n=3 mice), p values generalized linear model.

G. GFP-Myc mice were SRBC-immunized for 8 days and spleens analyzed by flow cytometry. CBs and CCs were gated from GC B cells.

H. Total GFP+ GC B cells were assigned to CBs and CCs, gated as shown in G. Each dot represents a mouse (n=4), mean ± SEM.

I. Flow cytometry plots showing the percentage of GFP+ cells among GC B splenocytes from GFP-Myc mice.

J. Quantification of GFP+ cells among GC B splenocytes from 4 GFP-Myc;Ezh2Y641F and 4 GFP-Myc;Cγ1-cre mice; mean ± SEM; unpaired t test.

Results representative of 2 experiments.

See also Figure S4.

We then organized the single cell gene expression profiles into a pseudotime vector using the Slingshot algorithm, allowing us to visualize the putative temporal relationships of these various GC B cell subpopulations going from centroblasts to transitional state to centrocyte and branching to either mature centrocyte/pre-memory cells or MYC-activated recycling cells (Figure 4D). After normalizing for cell numbers, this analysis confirmed the relative expansion of centrocytes (36% in Ezh2Y641F vs. 28% in WT, Figure 4E). Unexpectedly, we also observed a significant reduction in centrocytes manifesting the MYC-associated recycling signature (3.9% in WT vs. 2.9% in Ezh2Y641F, Figure 4F), suggesting that Ezh2Y641F was impairing recycling to the DZ.

To confirm the reduction in GC recycling cells, we crossed our Ezh2Y641F mice with animals bearing GFP-MYC fusion protein expressed from the Myc locus (Huang et al., 2008), which allows recycling cells to be identified by flow cytometry (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012). Concordant with previous reports (Ersching et al., 2017), GFP+ GC B cells were almost exclusively centrocytes (Figure 4G and 4H) and exhibited increased cell size (Figure S4F), consistent with these cells undergoing anabolic growth. GFP-Myc;Ezh2Y641F mice exhibited a severe reduction of GFP+ GC B cells as compared to GFP-Myc;Cγ1-cre control mice (Figure 4I and 4J), indicating impaired engagement of the MYC program that is required for GC B cells to re-enter the DZ among Ezh2 mutant centrocytes.

Ezh2 mutant GC B cells feature transcriptional repression with both gain and spreading of the H3K27me3

The effect of Ezh2 mutation on the histone landscape has not been evaluated in vivo and/or in primary cells. For this we performed liquid chromatography separation and top-down mass spectrometry of histone tryptic peptides extracted from purified GC B cells and naive B cells, to quantify histone modifications in an unbiased manner. We observed a massive increase of H3.1K27me3 in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells, mostly at the expense of reciprocal reduction in H3K27me2 (Figure 5A). Whereas 8% of histone 3.1 was trimethylated in control GC B cells, there was 29.8% trimethylation in Ezh2 mutant GC B cells. We also observed a smaller but significant reduction in H3K27me1. Surprisingly, the abundance of unmethylated H3K27 was significantly higher in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells (from 31% to 40% of H3.1). This effect although unexpected, is consistent with biochemistry studies showing that Ezh2Y641F exhibits impaired H3K27 monomethylation activity (McCabe et al., 2012a; Ott et al., 2014; Sneeringer et al., 2010; Yap et al., 2011). The minor H3 isoform H3.3 (~15% of H3), which is more dynamic and associated with actively transcribed genes, also showed significant changes although to a lesser degree than H3.1 (Figure S5A). As expected, there were no differences in histone modification profiles between WT and Ezh2Y641F naive B cells (Figure S5B) and virtually no effect on any other histone modification in GC B cells (data not shown).

Figure 5. Ezh2 mutation produces transcriptional repression and spreading of H3K27me3 surrounding TSS sites.

A. Relative abundance of H3.1K27 by liquid chromatography separation and mass spectrometry of histones from SRBC-immunized mice (n=5). Mean ± SEM; unpaired t test.

B. H3K27me3 bound promoters by ChIP-seq (n=3 mice).

C. H3K27me3 normalized read density heat maps at Ezh2Y641F-specific H3K27me3 promoters (top), and scaled H3K27me3 mean density plots of region between Ezh2Y641F-specific H3K27me3 TSS and nearest TSS (bottom).

D. RNA-seq (n=4 mice); transcripts in red, fold-change>1.5, q<0.01.

E. H3K27me3 normalized read density heat maps at promoters of differentially expressed genes in CC (top), and mean H3K27me3 profile across loci interval (bottom).

F. Pathway analysis in CC.

G-H. Fuzzy c-means clustering of RNA-seq data: line plot (G) and heatmap (H) of standardized log2 fold-change relative to normal naive B (NB) cells. Black lines in (G) are cluster centroid; each gene is colored by the degree of cluster membership. Heatmap in (H) are z-scores of log2 fold-change values for each gene relative to NB.

I. RNA-seq and H3K27me3 profiles of Ezh2Y641F vs. WT CC per module. H3K27me3 enrichment, Wilcoxon test.

J. GSEA of murine CC Ezh2Y641F gene modules against gene expression of EZH2 mutant FL cases vs. human CC.

K. RT-qPCR in NB, CB and CC (n=4). Each dot represents a mouse, mean fold change mRNA levels normalized to Hprt1 (Abi2), Gapdh (Lgr5) or Rpl13 (Tnfrsf13c,Tnfrsf14 and Ltb) ± SEM; unpaired t test, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

L. H3K27me3 ChIP-seq tracks and qChIP validation in CC. Each dot represents a mouse (n=3), mean ± SEM; unpaired t test, **p<0.01.

See also Figure S5.

Given the histone mass spectrometry data, we next examined H3K27me3 genomic distribution in purified centroblasts and centrocytes from three Ezh2Y641F and three WT control mice, using ChIP-Rx (Orlando et al., 2014). Unsupervised analysis revealed profound differences in the H3K27me3 profiles between WT and Ezh2Y641F centroblasts and centrocytes (Figure S5C). Examination of gene promoters revealed that whereas a majority of promoter H3K27me3 peaks (n≈8500) were shared between mutant and WT centroblasts or centrocytes, there was also gain of ~2800 de novo promoter peaks in the respective mutant cells, most of which (75%) were present in both centroblasts and centrocytes (Figure 5B). De novo H3K27me3 promoters in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells tended to be close to promoters that were marked by H3K27me3 in WT cells (empirical p=0.0012 for centroblasts and p=0.0013 for centrocytes). Notably, we observed spreading of H3K27me3 between WT and de novo H3K27me3 peaks in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells (Wilcoxon p<1x10-300, Figures 5C and S5D). Hence, de novo marked promoters might have become susceptible to gaining H3K27me3 through spreading of the mark from nearby promoters that normally manifest this histone modification.

To link the above ChIP-Rx results to gene transcription we performed RNA-seq in purified centroblasts and centrocytes of Ezh2Y641F and WT control mice. Unsupervised analysis showed a clear segregation of the four GC B cell subsets (Figure S5E). Using a supervised analysis we identified 648 down- and 272 upregulated genes in Ezh2Y641F centroblasts, and 941 down- and 508 upregulated genes in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes (Figure 5D). Centrocyte-repressed genes displayed marked spreading of H3K27me3 both upstream and downstream of well-defined TSS H3K27me3 peaks. Upregulated genes, in contrast, did not contain defined H3K27me3 peaks and had a more modest increase in H3K27me3 surrounding TSSs (Figure 5E). Similar patterns were found in centroblasts (Figure S5F). Moreover, genes linked to both de novo (Ezh2Y641F-specific) and shared H3K27me3 marked promoters, were more repressed in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells (FDR<0.005, NES<-1.3 Figure S5G). Hence the EZH2 mutant transcriptional signature is derived from two sources: further repression of genes already regulated by EZH2 in WT GCs, and de novo repression of genes that gain H3K27me3 ectopically in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells.

Focusing on centrocytes (the cells most phenotypically perturbed in Ezh2Y641 mice) and using both hypergeometric and GSEA analyses, we observed that Ezh2Y641F downregulated genes were enriched for those that are normally repressed by EZH2 in GC B cells (Beguelin et al., 2013) (Figures 5F and S5H). This is in line with the notion that most gain of H3K27me3 occurs at genes already normally targeted by EZH2 in GC B cells. Consistent with the reduction in MYC-driven GC recycling cells, we observed enrichment for MYC downregulated genes among genes induced in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes, and reciprocally, enrichment for MYC upregulated genes being repressed. The GC recycling phase is dependent in part on CD40 signaling, and we observed that genes normally downregulated by CD40 were instead induced in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes, suggesting lack of CD40 response. Finally, genes that were significantly repressed in EZH2 mutant FL patients were also enriched for repression in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes (Figures 5F and S5H). Reciprocally, genes that are repressed in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes were also repressed in patients with EZH2 mutant FL (Figure S5I). Low grade FL is mainly composed of malignant centrocyte-like cells, and these data are consistent with these Ezh2Y641F centrocytes giving rise to FL.

Mutant Ezh2 disrupts dynamic gene expression changes in centrocytes, linked to aberrant H3K27 trimethylation

Phenotypic transitions during the GC reaction are driven by waves of differential gene expression linked to signals received from the microenvironment (Mesin et al., 2016). Many B cell signal responsive genes are repressed in centroblasts but are then induced in centrocytes (Victora et al., 2010). To determine how transcriptional programming is affected in the presence of mutant Ezh2, RNA-seq data were used to calculate the trajectory of gene regulation from naive B cells to centroblasts and then centrocytes in Ezh2Y641F vs. WT cells. To group genes based on their pattern of perturbation by mutant Ezh2, we used K means clustering, which identified eight distinct gene expression modules based on trajectory of the constituent genes across these cell types (Figure 5G and 5H).

Module 1 and 2 genes were aberrantly upregulated in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes, albeit with distinct trajectories. These include canonical centrocyte genes; anti-apoptotic factors, and genes involved in antigen presentation (Figure 5G and 5H). Of particular note were genes involved in interaction with FDCs, such as Tnfrsf13c (BAFF receptor) (Figure S5J). Module 8 contains genes that are normally downregulated in GC B cells, but are aberrantly upregulated in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells. Many of these are normally upregulated when B cells exit the GC reaction and commit to memory B cell differentiation such as Gpr183, Ccr6 and MHC class II antigen presentation genes (Figure S5J). Of note, Ltb, which is also involved in interaction with FDCs, was significantly upregulated in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes.

Modules 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 contain genes that are aberrantly repressed in Ezh2Y641F GC B cells, albeit with distinct trajectories (Figure 5G and 5H). Module 3 contains pro-apoptotic BH3 domain genes, and several DZ hallmark genes (Victora et al., 2010). Module 4 contains genes involved in the recycling program of centrocytes re-entering the DZ (Ersching et al., 2017). Of particular interest, modules 5, 6 and 7 contain genes that are normally expressed in the LZ and are linked to Tfh immune synapse signaling but fail to be induced or maintained at their normal levels in the presence of mutant EZH2. This includes genes such as Cd69 (linked to stable Tfh-GC B cell contacts), Basp1 (induced by B cell activation with anti-IgM and anti-CD40), Icosl and Icam1 (Ise et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2015; Papa and Vinuesa, 2018; Yu et al., 2008; Zaretsky et al., 2017) (Figure S5J).

To determine if the trajectory perturbation of genes was linked to changes in H3K27me3 deposition, we examined their ChIP-seq profiles and observed that all repressed modules exhibited significant gain of H3K27me3, with the exception of module 7, which contains a small fraction of upregulated genes (Figure 5I). In contrast, there was no significant change in H3K27me3 in the upregulated modules (Figure 5I). We performed independent qChIP and qPCR experiments in purified Ezh2Y641F and WT B cell subsets to validate these gene expression and H3K27me3 changes for a subset of genes (Figures 5K, 5L, S5K and S5L). In spite of the species difference, genetic heterogeneity and more advanced stage of fully established human FLs, we still observed significant enrichment for repression of cluster 3, 4 and 5 genes, and upregulation of cluster 1 and 8 genes in primary human FLs (Ortega-Molina et al., 2015), with discordance only noted for cluster 7 (Figure 5J). Altogether these results suggest that the primary effect of mutant Ezh2 is aberrant repression of genes, many of which are normally dynamically regulated during the GC reaction. The fact that many genes linked to Tfh signaling to centrocytes were aberrantly repressed (including the centrocyte recycling program), points to this aspect as a potential driver of early EZH2 mutant FL pathogenesis.

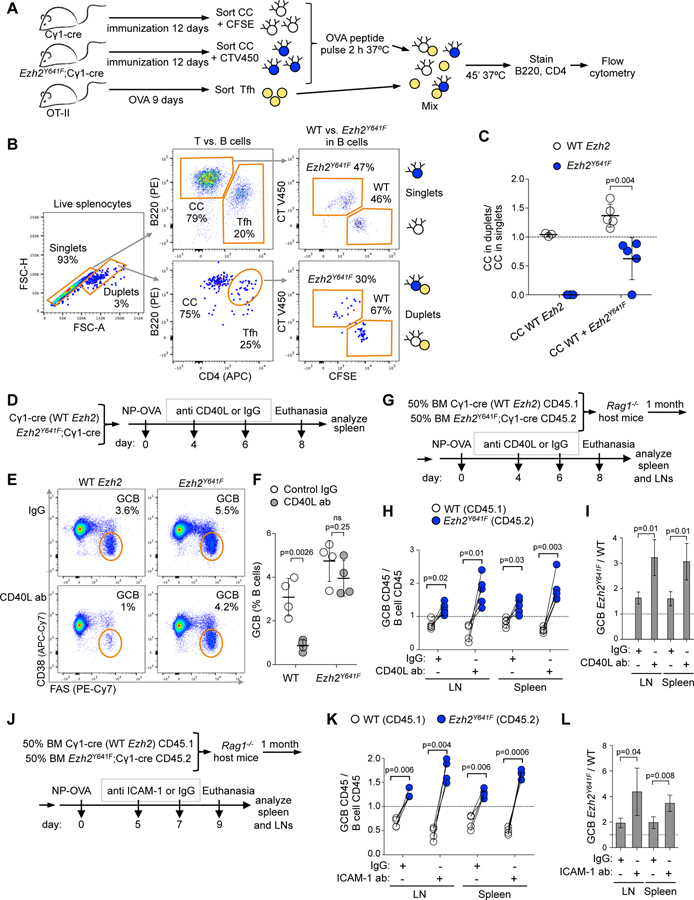

Ezh2Y641F GC B cells manifest decreased interaction and dependency on Tfh cells

In the GC LZ, B cells require strong interaction with T cells to survive and be selected for their ultimate fate. This normally depends on B cell specificity for antigen (Mesin et al., 2016; Meyer-Hermann et al., 2006; Victora et al., 2010). Yet our data suggest that this process might be impaired in centrocytes bearing the Ezh2Y641 mutation. To evaluate this possibility, we first assessed the protein levels of adhesion and activation molecules in GC B cells that are involved in the interaction with Tfh cells. SLAM, ICAM-1, ICAM-2 and Ly108 protein expression was significantly downregulated in Ezh2Y641F centrocytes (Figure S6A). Next, we assessed whether FACS-sorted Ezh2 mutant or WT centrocytes (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4loCD86hi) loaded with OVA antigen could preferentially interact with OVA-primed OT-II Tfh cells (CD4+B220-PD1hiCXCR5hi) ex vivo (Figure 6A) (Ise et al., 2018) by performing flow cytometry to assess formation of B cell–T cell conjugates by gating on cell duplets, normalizing to cell singlets for quantification (Figure 6B). Ezh2Y641F centrocytes formed ~40% less conjugates with Tfh than WT centrocytes (Figure 6C), suggesting that Ezh2 mutation impairs formation of stable centrocyte-Tfh interactions.

Figure 6. Decreased interaction and dependency on Tfh cells by Ezh2Y641F GC B cells.

A. Five Cγ1-cre and 5 Ezh2Y641F mice were immunized with NP-CGG for 12 days and CCs (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4loCD86hi) were collected. WT CCs were stained with CFSE and Ezh2Y641F with CellTrace V450. Tfh (CD4+B220-PD1hiCXCR5hi) were sorted from OVA-immunized OT-II mice. CCs were pulsed ex vivo with OVA323–339 and then mixed with Tfh.

B. Tfh-CC interaction was assessed by flow cytometry-based ex vivo assay. Tfh-CC conjugates were identified by gating on cell duplets.

C. Tfh-CC duplets were normalized to CC singlets for quantification. WT CCs only, and WT CCs mixed with Ezh2Y641F CCs were incubated with Tfh. Each dot represents CCs from one mouse (n=5), mean ± SEM; unpaired t test. Results representative of 2 experiments.

D. WT and Ezh2Y641F immunized mice (n=4) were treated with two doses of 100 µg anti CD40L or control IgG antibody.

E. Representative flow cytometry plots of %GC B cells gated on live B cells of mice groups shown in D.

F. Average percentage of GC B cells gated as shown in E. Each dot represents GC B cells from one mouse (n=4), mean ± SEM; unpaired t test.

G. Mixed chimera mice (n=4) immunized with NP-OVA were treated with anti CD40L antibody as in D.

H. Splenocytes and LN cells collected as shown in G were analyzed by flow cytometry, normalizing the percentage of CD45.1+ GC B cells (CD38-FAS+) to their parental CD45.1+ B cells (B220+DAPI-), and equivalent normalization with CD45.2+ populations. Each pair of connected dots represents a mouse; paired t tests.

I. Ratio of Ezh2Y641F to WT GC B cells from H; mean ± SEM; unpaired t test.

J. Mixed chimera mice (n=4) immunized with NP-OVA were treated with two doses of 150 µg anti ICAM-1 or control IgG antibody.

K. Splenocytes and LN cells collected as shown in J were analyzed by flow cytometry as in H.

L. Ratio of Ezh2Y641F to WT GC B cells from K; mean ± SEM; unpaired t test.

Results in (D-L) representative of 2 to 4 experiments.

See also Figure S6.

Since T cell help is required for the survival of GC B cells, we hypothesized that Ezh2 mutant centrocytes must be aberrantly able to survive even without this critical signal. T cell help in the LZ is critically dependent on CD40-CD40L binding between centrocytes and Tfh cells. Blockade of this interaction causes collapse of the GC reaction (Elgueta et al., 2009). To determine if Ezh2 mutant centrocytes had become less dependent of T cell help, we next immunized Ezh2Y641F and WT mice and then administered two sequential doses of CD40L binding antibody after GCs were already established (Figure 6D). Treatment of WT Cγ1-cre mice with anti CD40L antibody significantly impaired the GC reaction as expected. In striking contrast, there was no significant impairment of GCs in Ezh2Y641F mice (Figure 6E and 6F). To validate these results in a setting where WT and Ezh2Y641F GC B cells must compete within the same microenvironment, we performed mixed chimera experiments (Figure 6G). Examination of spleens and lymph nodes confirmed that there were equal proportions of Ezh2Y641F vs. WT naive B cells (Figure S6B and S6C). As shown earlier, mice immunized with control antibodies display an increased proportion of Ezh2Y641F relative to WT GC B cells. However, upon exposure to CD40L blocking antibodies, this fraction increased even further due to more dramatic loss of WT GC B cells in comparison with Ezh2Y641F GC B cells (Figures 6H, 6I and S6B). We observed similar results with longer duration anti-CD40L treatment (Figure S6D–S6H). As a second approach for interfering with T cell help we performed similar experiments using anti-ICAM-1 blocking antibodies (Figure 6J), which resulted in a further competitive survival advantage of Ezh2Y641F GC B cells (Figures 6K, 6L and S6I–S6K) without changes in naive B cell proportions (Figure S6L).

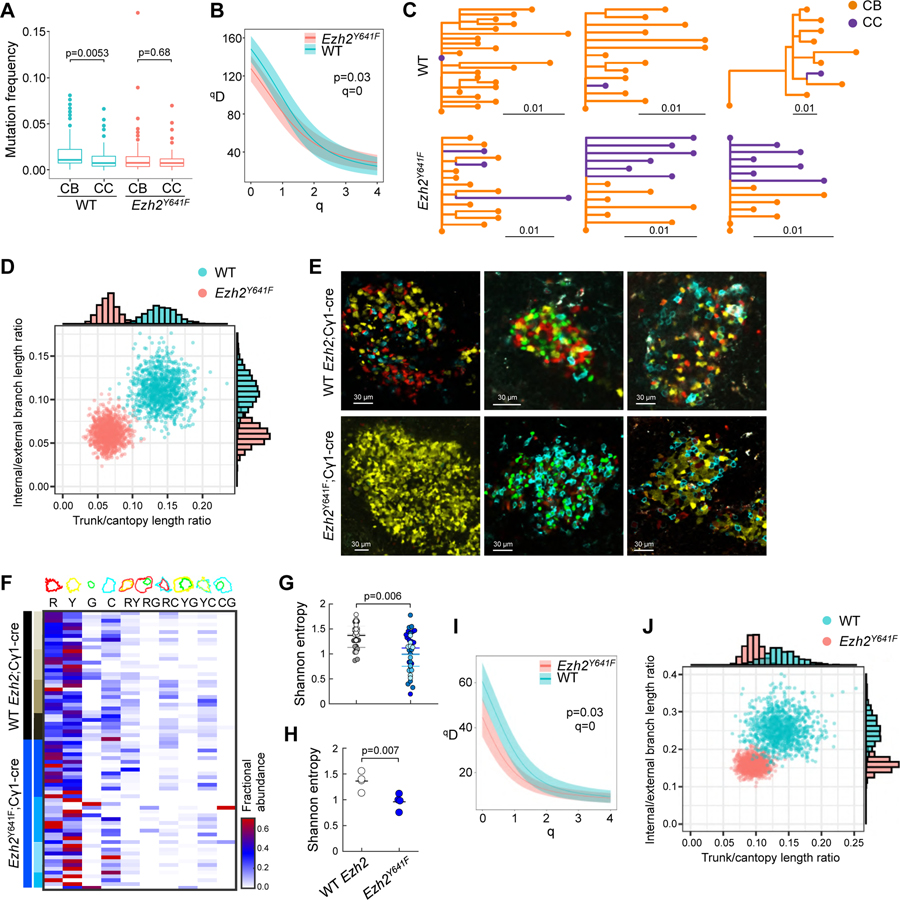

Ezh2Y641F GC B cells evade Tfh directed clonal selection and affinity maturation to dominate the GC reaction

T cell help is required for centrocytes to recycle back to the DZ for additional mutagenesis and hence directs clonal evolution of the immunoglobulin loci (Mesin et al., 2016). Although our above data suggest that the dominant effect of mutant Ezh2 is to disrupt this process, definitive genetic proof requires in-depth analysis of clonal diversification during the GC reaction. Using immunized R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP;Ezh2Y641F and R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP;Cγ1-cre control mice we excised individual YFP+ GCs by microdissection, and performed single cell genomic clonality assays by sequencing IgM and IgG1 variable regions (Figure S7A). Individual variable regions sequences from Ezh2Y641F GCs were significantly more likely to be classified as centrocytes (40% of sequences) compared to those from WT GCs (23%; chi-squared p<0.001), as expected given the expansion of LZ phenotype in Ezh2Y641F GCs. The mean mutation frequency of WT GC B cells was significantly higher than that of Ezh2Y641F GC B cells (Wilcoxon rank-sum test p<1x10-5; means=0.016/bp, 0.011/bp, respectively). Further, the mutation frequency of WT centroblasts was significantly higher than WT centrocytes (p=0.005, Figure 7A), consistent with centroblasts representing the progeny of centrocytes that recycle back to the DZ. In contrast, centroblasts did not exhibit any increase in mutation frequency as compared to centrocytes in Ezh2Y641F mutant mice (Figure 7A), supporting that after their initial transit through the DZ, Ezh2Y641F centrocytes are less likely to recycle back to the DZ for additional mutagenesis.

Figure 7. Ezh2 mutation induces reduction in clonality.

A. Mutation frequency of V segments (n=3 mice), measured in proportion of mismatched nucleotide sites between each V segment of each sequence and its predicted germline V segment; p values Wilcoxon rank sum test.

B. Diversity curves of YFP;Cγ1-cre (WT) and YFP;Ezh2Y641F mice generated through 1000 uniformly sampled bootstrap replicates.

C. Lineage trees of three largest WT and Ezh2Y641F YFP mice.

D. Distribution of 1000 bootstrap replicates showing total trunk/canopy (non-trunk) branch length ratio and internal/external branch length ratio of lineage trees obtained from WT and Ezh2Y641F YFP mice. Marginal histograms of each statistic are shown on the top and right sides.

E. IF confocal microscopy images of R26R-Confetti splenic GCs at day 10 post-SRBC immunization.

F. Heatmap representing quantification of clonal abundance from GCs derived from 4 R26R-Confetti;Cγ1-cre and 4 R26R-Confetti;Ezh2Y641F mice. Scale from white to red denotes the fractional abundance of each clone.

G-H. Shannon entropy was calculated per GC (represented by dots, with each color representing GC from a different mouse, n WT=34, Ezh2Y641F=39) (G) and for all GCs per mouse (H).

I. Diversity curves of R26R-Confetti mice generated as in B.

J. Distribution of lineage trees obtained from R26R-Confetti mice analyzed as in D.

See also Figure S7.

We found multiple pieces of evidence consistent with disrupted affinity maturation in Ezh2Y641F mice. We observed significantly reduced diversity of clones among Ezh2Y641F GC B cells as compared to WT GCs based on the distribution of clone sizes (Figure 7B). We also observed differences among B cell lineage trees taken from Ezh2Y641F and WT mice. During normal affinity maturation, a combination of selection and genetic drift produces shared mutations among sequences within a clone, forming the internal branches of its lineage tree. Mutations shared by all sequences form the “trunk” branch leading immediately from the germline to the sequences’ universal common ancestor. Lineage trees estimated from Ezh2Y641F mice had proportionally shorter trunks and internal branches compared to lineage trees estimated from WT mice (Figure 7C and 7D). Ezh2Y641F trees were more star-like, with external branches radiating out from a single common ancestor closely related to their germline sequences (e.g. Figure 7C). Ezh2Y641F mice showed evidence of reduced efficacy of affinity maturation. Immunization with NP-OVA is characterized by a tryptophan to leucine substitution at IMGT codon position 38 of the V gene V1–72*01 that strongly increases binding affinity to NP-OVA (Rajewsky et al., 1987). Of the 46 V1–72*01-derived sequences observed in WT GCs, five sequences from three clones in two mice contained leucine at this position. By contrast, none of the 66 V1–72*01-derived sequences from Ezh2Y641F mice contained this substitution.

As further confirmation that Ezh2Y641F GCs have decreased clonal diversity, we generated Ezh2Y641F mice that were also homozygous for R26R-Confetti allele (Livet et al., 2007), which labels cells in up to 10 different color combinations when activated (Figure S7B). Confocal microscopic examination of GCs from immunized R26R-Confetti mice showed that Ezh2Y641F displayed reduced color diversification compared to those of Cγ1-cre mice (Figures 7E and S7C). To assess this from a quantitative standpoint we generated an optimal segmentation algorithm that classified cells within GCs according to color combination (Figure S7D and S7E). Quantifying the abundance of cells per clone within GCs revealed a significant reduction in the Shannon entropy (diversity) among individual Ezh2Y641F GCs, as well as when all the tested GCs were combined per mouse (Figure 7F–7H). To confirm this pattern at the sequence level, we performed single cell V region sequencing from individual GCs as above, and grouped sequences into clonal clusters based on their sequence similarity. Confirming our data from the YFP system, R26R-Confetti;Ezh2Y641F mice had reduced clonal diversity (Figure 7I), and their lineage trees had reduced proportional trunk and internal branch lengths (Figure 7J). To assess the reliability of clonal diversity measures obtained in our confocal microscopy analysis, we observed that while color combinations do not completely distinguish sequence-defined clonal clusters, sequences within clones were enriched for particular combinations of colors (Figure S7F). This pattern may be due to persistent recombination of the Cγ1-cre cassette.

Taken together, these results confirm that Ezh2 mutant GCs fail to engage T cells, and hence do not receive Tfh signals that would induce recycling to the DZ. In contrast to normal cells, which cannot survive without T cell help, Ezh2 mutant centrocytes can further proliferate in the LZ. Hence the dominant competitive advantage effect of the Ezh2 mutation during early stages of transformation is to uncouple GC B cells from the critical T cell help checkpoint, which allows waves of GC B cells entering the LZ to persist and expand regardless of their immunoglobulin status.

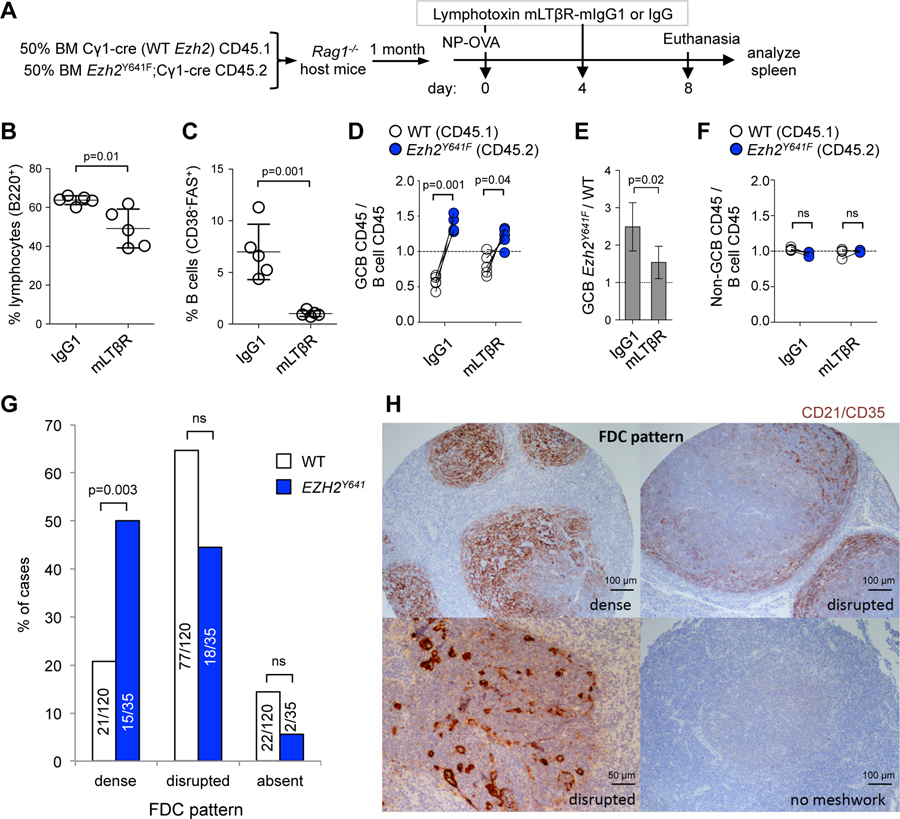

Ezh2Y641F GC B cells switch from T cell to FDC dependency

Given that Ezh2Y641F GC B cells were less dependent on T cell help, we postulated that they might be instead dependent on FDCs, especially given the expanded FDC networks and upregulation of genes linked to FDC signaling. Maintenance of FDC networks and GCs requires signaling through lymphotoxin b (Ngo et al., 1999), which is expressed on GC B cells and was further induced in Ezh2 mutant centrocytes (Figure 5K). To determine whether Ezh2 mutant GCs were dependent on these FDC interactions we administered soluble lymphotoxin β receptor (mLTβR) (Browning et al., 1995) to immunized mixed chimera mice to suppress FDC functions (Figure 8A). As expected, exposure to this inhibitor caused a modest overall reduction in splenic B cells, and a more severe reduction in the abundance of GC B cells (Figure 8B and 8C). However, in contrast to their marked advantage in the setting of Tfh interaction blockade, Ezh2Y641F GC B cells manifested loss of competitive fitness and appeared even more sensitive to FDC blockade than their WT counterparts when exposed to mLTβR (Figure 8D and 8E). As expected there was no selective effect of mLTβR against Ezh2Y641F or WT naive B cells (Figure 8F).

Figure 8. Ezh2Y641F GC B cells switch from T cell to FDC dependency.

A. Mixed chimera mice (n=5) immunized with NP-OVA were treated with two doses of 100 µg lymphotoxin mLTβR-mIgG1 or control IgG antibody.

B-C. Effect of mLTβR-mIgG1 was evaluated by flow cytometry in splenic B cells (B) and GC B cells (C); data are mean (n=5) ± SEM; unpaired t test.

D. GC B cells collected as shown in A were analyzed by flow cytometry, by normalizing the percentage of CD45.1+ GC B cells (CD38-FAS+) to their parental CD45.1+ B cells (B220+DAPI-), and equivalent normalization with CD45.2+ populations. Each pair of connected dots represents a mouse; paired t tests.

E. Ratio of Ezh2Y641F to WT GC B cells from D; mean ± SEM; unpaired t test.

F. Analysis of non-GC B cells (CD38+FAS-) was done as in D.

G. Analysis of FDC patterns in a tissue microarray with 155 grade 1 or 2 FL samples (120 WT + 35 EZH2Y641); p values Fisher’s exact test.

H. FDC patterns were clasified based on the expression of CD21/CD35 by IHC.

These data suggest that Ezh2 mutation reprograms the GC immune niche to generate an abnormal tissue featuring FDC dependent-expansion of aberrant centrocytes. To determine if this pattern is reflected in primary human FLs with EZH2 mutations we performed immunohistochemistry staining for CD21/CD35 on a tissue microarray with 209 genetically characterized FL patients, of which 17.2% carried EZH2Y641 point mutations (Kridel et al., 2016). There was no significant association between EZH2 mutation status and histological grade. Focusing on the grade 1 and 2 FLs, we found that EZH2Y641 FLs feature significantly greater association with intact and extensive FDC networks as compared to EZH2 WT lymphomas, regardless of grade (Figure 8G), and exemplified in Figure 8H. Staining for CD4 and CD8 T cells did not reveal significant differences in abundance of these cells among EZH2 mutant and WT FLs (data not shown). Collectively these data provide an explanation for how FLs arise from aberrant GC reactions directed by mutant EZH2 reprogramming of the immune microenvironment.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that Ezh2 mutation sets the stage for FL pathogenesis in GC B cells by remodeling dynamic interactions between B cells, Tfh cells and FDCs. This likely occurs primarily due to loss of plasticity of transcriptional programming in centrocytes, which normally respond rapidly to external signals that direct them to alternative cell fates (Shlomchik et al., 2019). One of our central findings is that Ezh2 mutant GC B cells manifest reduced dependency on LZ T cell help, suggesting that they no longer need to compete for access to T cell help, allowing the massive numbers of B cells arriving in the LZ to survive and persist as slowly proliferative centrocytes.

Lack of T cell help normally results in death of centrocytes (Mayer et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2018). The lower apoptosis rate in the Ezh2Y641F LZ vs. DZ may be explained by the observation that LZ GC B cells mainly die by default if they are not positively selected (Stewart et al., 2018). The survival and proliferation phenotype of Ezh2 mutant centrocytes is largely explained through their driving expansion of and dependency on FDCs. Given that centrocytes normally recycle to the proliferative DZ, it is hard to imagine how FLs could form, since LZ B cells should be quickly overwhelmed by rapidly proliferating centroblastic cells. We provide evidence for how this situation might arise: since mutant Ezh2 impairs interaction with Tfh cells, centrocytes would not receive signals that trigger the MYC-dependent GC recycling response. The relevance of these findings to FL is further suggested by strong association between EZH2 mutation with dense FDC networks, and persistence of the Ezh2 mutant centrocyte transcriptional program.

From the mechanistic perspective, in the normal GC reaction EZH2 mediates establishment of bivalent chromatin at promoters that are repressed in the DZ and re-activated in the LZ (Beguelin et al., 2013). Mutation of Ezh2 at Y641 disrupts this transcriptional plasticity. Indeed, a dominant effect of mutant Ezh2 was to prevent induction of genes that are normally upregulated in centrocytes, associated with spreading of H3K27me3 mark from gene promoters to neighboring chromatin. This is consistent with the fact that WT EZH2 has poor trimethylation activity (McCabe et al., 2012a; Sneeringer et al., 2010; Yap et al., 2011) and can therefore only generate H3K27me3 where its binding is most stable (e.g. around promoters (Laugesen et al., 2019)). In the case of the EZH2Y641 mutant, it is likely that its more transient presence at surrounding sites is sufficient to generate H3K27me3 from pre-existing H3K27me2. Interestingly, the H3K27me2 mark has been proposed to stabilize transcriptional programs by preventing ectopic firing of promoter and enhancers (Conway et al., 2015; Ferrari et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2015). However in the presence of mutant EZH2, H3K27me2 marked promoters may become more likely to acquire H3K27me3. More efficient spreading of PRC2 to these sites may be further favored through the EED subunit, which stabilizes PRC2 binding through its association with H3K27me3 (Hansen et al., 2008; Margueron et al., 2009; Oksuz et al., 2018). Another relevant consideration that might explain preferential spreading of H3K27me3 to nearby promoters, could be their shared localization within topologically associating domains (TAD) (Donaldson-Collier et al., 2019). Finally, in contrast to the profiles of B lineage splenocytes expressing Ezh2Y641F (Souroullas et al., 2016), we could not link transcriptional upregulation in centrocytes with loss of H3K27me3. Hence we favor the view that in the GC context, upregulated genes are associated with indirect effects of Ezh2Y641F, such as aberrant downregulation of transcriptional repressors or alteration of signaling pathways.

Collectively, these data suggest that EZH2 mutation favors malignant transformation through reprogramming of the immune niche. EZH2 mutations tend to occur early during transformation (Chapuy et al., 2018; Green, 2018), suggesting that in contrast to solid tumors where loss of immune signaling tends to be a late occurrence, remodeling of the immune response might be critical for initiation of GC derived lymphomas. Along these lines, it is notable that GC B cells already normally manifest many of the hallmarks of tumor cells (e.g. tolerance of genomic instability, unrestrained proliferation, etc., (Mlynarczyk et al., 2019). Abnormal outgrowth of GC B cells is restricted by their need for T cell help. Hence there is logic to the notion that founder mutations in GC derived lymphomas would have the effect of overcoming this mechanism. EZH2 inhibitors are highly active against EZH2 mutant FLs. It is intriguing to speculate that this may be due at least in part to restoration of proper interactions between FL centrocytes with their immune microenvironment.

STAR METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Ari M. Melnick (amm2014@med.cornell.edu). This study did not generate new unique reagents.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mouse models

Animal care was in strict compliance with institutional guidelines established by the Weill Cornell Medical College, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences 1996), and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Conditional Ezh2(Y641F)fl knock-in model was generated in our lab (Beguelin et al., 2016). By crossing Ezh2(Y641F)fl with the transgenic Cγ1-cre strain (The Jackson Laboratory, stock 010611) we generated heterozygous mice. As control group, we used EZH2(Y641F)WT Cγ1-cre positive littermates. The following strains were obtained from Jackson Laboratory: C57Bl/6J (CD45.2, stock 000664), B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/Boy (CD45.1, stock 002014), Rag1 KO (stock 002216), R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP (stock 006148), OT-II (stock 004194), R26R-Confetti (stock 013731), GFP-Myc (stock 021935). R26-Fucci2aR was developed by J. Jackson group (Mort et al., 2014).

METHOD DETAILS

Germinal center assessment in mice

The Research Animal Resource Center of the Weill Cornell Medical College of Medicine approved all mouse procedures. All knockout, knock-in and transgenic mice were used for assessment of the GC formation. Age- and sex-matched mice were immunized intraperitoneally at 8 to 12 weeks of age with either 0.5 ml of a 2% sheep red blood cell (SRBC) suspension in PBS (Cocalico Biologicals), or 50 µg of the highly substituted hapten NP (NP16 to NP32) conjugated to the carrier protein ovalbumin (OVA, Biosearch Technologies), or CGG (Chicken Gamma Globulin, Biosearch Technologies), or KLH (Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin, Biosearch Technologies) absorbed to aluminum hydroxide (alum, ThermoFisher Scientific) at a 2:1 ratio. To induce GC reaction in popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes, mice were injected subcutaneously in footpads with 25 µg NP16-OVA. In the experiments where interactions with Tfh or FDC were blocked in vivo, mice received 100 µg anti CD40L antibody i.v. (clone MR-1, BioXCell BE0017), 150 µg anti ICAM-1 antibody i.p. (clone YN1/1.7.4, BioXCell BE0020), 100 µg recombinant mLTβR (a fusion protein of lymphotoxin β receptor and Fc region of mouse IgG, which acts as inhibitor of transmembrane LTβR) i.v. (R&D Systems 1008-LR), or control IgG antibodies (BioXCell BE0091 and BE0090).

Chimeric bone marrow transplantations

Bone marrow cells were harvested from 8–12 week old Cγ1-cre CD45.1 and Ezh2(Y641F)fl/WT;Cγ1-cre CD45.2 mice. WT and Ezh2Y641F bone marrow cells were mixed at the indicated ratios and one million cells were injected into the tail veins of sub-lethally irradiated (650 rads) Rag1-/- host females. One month after transplant to ensure engraftment, mice were immunized and treated as indicated in the figures.

Flow cytometry analysis and cell sorting

Single-cell suspensions from mouse spleens, lymph nodes and bone marrow were incubated with Fc block antibody (CD16/CD32, BD 553142) and subsequently stained using the following fluorescent-labeled anti-mouse antibodies: from eBioscience, ThermoFisher Scientific: eFluor506 anti-B220 (69–0452, dilution 1:750), APC anti-CD38 (17–0381, dilution 1:750), PE anti-CXCR4 (12–9991, dilution 1:400), APC anti-CD4 (17–0041, dilution 1:750), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-CD45.1 (45–0453, dilution 1:750), PE-Cy7 anti-CD45.2 (25–0454, dilution 1:750), FITC anti-PD-1 (11–9985, dilution 1:200), PE-Cy7 streptavidin (25–4317, dilution 1:1000); from BD Biosciences: APC and BV786 anti-B220 (553092 and 563894, dilution 1:750), PE, PE-Cy7 and BV421 anti-FAS (554258, 557653 and 562633, dilution 1:750), FITC and BV395 anti-CD38 (558813 and 740245, dilution 1:750), PE-Cy7 and BV421 anti-CD86 (560582 and 564198, dilution 1:500), biotin anti-CXCR4 (551968, dilution 1:400), biotin anti-CXCR5 (551960, dilution 1:400), PE and BV510 anti-IgD (558597 and 563110, dilution 1:750), APC and BV421 anti-IgG1 (560089 and 562580, dilution 1:500), BUV737 anti-CD138 (564430, dilution 1:500), AF647 anti-cleaved caspase-3 (560626, dilution 1:100), BV421 anti-Ki67 (562899, dilution 1:500), BUV395 anti-BAFF-R (742871, dilution 1:400), BV650 anti-ICAM-2 (740470, dilution 1:300), BV711 anti-Ly108 (740823, dilution 1:300), AF488 anti-EZH2 (562479, dilution 1:50); from BioLegend: APC-Cy7 and PE anti-B220 (103224 and 103208, dilution 1:750), APC-Cy7 anti-CD38 (102728, dilution 1:750), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-GL7 (144610, dilution 1:750), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-FAS (152610, dilution 1:500), APC anti-CD86 (105012, dilution 1:500), biotin anti-CD83 (121504, dilution 1:400), PE-Cy7 and BV421 anti-CD138 (142514 and 142508, dilution 1:500), APC-Cy7 anti-CD45.2 (109824, dilution 1:750), APC streptavidin (405207, dilution 1:1000), PerCP-Cy5.5 anti-ICAM-1 (116123, dilution 1:300); from Biosearch Technologies: PE NP (N-5070–1, dilution 1:500); from Cell Signaling: AF647 anti-H3K27me3 (12158, dilution 1:400). NIP-haptenated FITC was obtained from M. Shlomchik lab (Anderson et al., 2007). DAPI was used for the exclusion of dead cells. For internal markers, cells were fixed and permeabilized with BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD Biosciences) and further permeabilized with cold Phosflow Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences). APC conjugated Annexin V (BD Biosciences 550475, dilution 1:100) in Annexin V binding buffer (BD Biosciences) was used to identify apoptotic cells. FITC-VAD-FMK pan-caspase inhibitor (BioVision) was used as a marker for detection of activated caspase in apoptotic cells. Data were acquired on BD FACS Canto II and BD Fortessa flow cytometer analyzers, and analyzed using FlowJo software package (Becton Dickinson). When B cell populations were sorted, single-cell suspensions of splenocytes were pre-enriched in B cells using CD45R (B220) magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, 130–049-501). Cell sorting was performed using BD Aria II sorter with 5 lasers (355, 405, 488, 561, 640), and BD Influx sorter with 6 lasers (355, 405, 445, 488, 561, 640).

Tfh-centrocyte interaction ex vivo

Conjugate formation assays were performed as previously described (Ise et al., 2018). Sorted splenic centrocytes (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4loCD86hi) from NP-CGG immunized Cγ1-cre mice were incubated with Fc block and then stained with 1 µM cell tracer CFSE (Life Technologies) and Ezh2Y641F centrocytes with 1 µM cell tracer Violet (Life Technologies). After washing with PBS, centrocytes were incubated with 5 µM OVA323–339 (MBL International, TS-M703) for 2 hours at 37°C. Ten thousand centrocytes (10,000 WT or 5,000 WT + 5,000 Ezh2Y641F) were mixed with 5,000 splenic Tfh (CD4+B220-PD1hiCXCR5hi) sorted from OVA immunized OT-II mice, and cultured in 96-well U-bottom plates for 45 minutes at 37°C. Cells were next stained with anti-B220 (PE) and anti-CD4 (APC). Cells were vigorously pipetted to disrupt nonspecific conjugates and CD4 expression on B220+ cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence and imaging of tissues

Spleens and lymph nodes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and either embedded in 2% low melt agarose for vibrotome sectioning, or subjected to sucrose gradient of 10%, 20% and 30%, embedded in O.C.T. and frozen down for cryostat sectioning. Mouse models coding for fluorescent proteins (R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP, R26R-Confetti and R26-Fucci2aR) were injected with 2 µg BV421-conjugated anti-CD35 (BD Biosciences 740029) when indicated 16 hours before euthanizing, and tissues were sectioned using a vibratome (70 µm for imaging and 150 µm when single GCs were aisolated). For quantification of chimeras (Figure 1) and LZ staining (Figure 2E), frozen tissues in O.C.T. were sectioned using a cryostat (7 µm), incubated with biotinylated Peanut Agglutinin (PNA, Vector Laboratories B-1075, dilution 1:500) followed by streptavidin conjugated to AF488 (BioLegend, 405235, dilution 1:500) or AF555 (Invitrogen, S32355, dilution 1:500), and the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies: AF594 anti-CD45.1, AF647 anti-CD45.2, AF488 anti-IgD (BioLegend 110750, 109817, 405717, dilution 1:200). Tissue sections were imaged at 40x or 25x using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope with 7 laser excitations at 405, 458, 488, 514, 561, 594 and 633, and analyzed using Fiji (ImageJ) software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

Immunohistochemistry and FDC pattern in TMAs

For immunohistochemical staining of CD21/CD35 (antibody clone 2G9, Cell Marque), 4 µm slides of the tissue microarrays of 232 primary diagnosed FL cases, which were previously published (Kridel et al., 2016), were used and 209 cases were available for FDC evaluation. 155 cases were grade 1 or 2; 35 were grade 3, and there was not significant correlation of FL grade with the presence of EZH2 mutation (Fisher’s exact test, p=0.209). Staining was performed on a Benchmark XT platform (Ventana). FDC network pattern was classified by a board certified pathologists as (1) dense: almost all tumor follicles were packed by FDC, (2) disrupted: scattered or peripheral presence of FDC, (3) absence.

ELISPOT

Splenocytes were harvested 12 days after NP-OVA immunization, and bone marrow 76 days after NP-KLH immunization. Secreted NP-specific immunoglobulin IgG1 and IgM levels from one million cells per well of 96-well plate were tested for binding to NP4- and NP30-BSA (Biosearch Technologies, N-5050H and N-5050XL) coated plates by enzyme-linked immune absorbent spot (ELISPOT). HRP-conjugated antibodies anti-IgG1 and anti-IgM were obtained from SouthernBiotech (1070–05 and 1020–05).

ELISA

Murine serum samples were collected before immunization, 12 days after NP-OVA, and 22 and 76 days after NP-KLH immunization, and immunoglobulin levels were analyzed by ELISA. Sera were tested for the binding of NP-specific IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgA, IgM, Igκ and Igλ antibodies (SouthernBiotech, 5300–01, 1050–01 and 1060–01) to NP4-and NP30-BSA coated plates.

Single cell RNA-seq and analysis

YFP+IgD- splenocytes were sorted from 3 R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP;Cγ1-cre and 3 R26-lox-stop-lox-YFP;Ezh2(Y641F)fl/WT;Cγ1-cre mice 8 days after SRBC immunization. Ten thousand sorted cells from each spleen were subjected to single cell RNA-seq using 10X Genomics Chromium platform. Library preparation for single cell 3’ RNA-seq v2, sequencing and post-processing of the raw data was performed at the Epigenomics Core at Weill Cornell Medicine. Libraries were prepared according to 10X Genomics specifications. Briefly, the six independent cellular suspensions were loaded onto the 10X Genomics Chromium platform to generate barcoded single-cell GEMs (Gel Bead-In Emulsions). After RT reaction, GEMs were broken and the single-strand cDNA was cleaned up with DynaBeads MyOne Silane Beads (ThermoFisher Scientific). cDNA was amplified for 12 cycles. Quality of the cDNA was assessed using an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer, obtaining a product of about 1588 bp. This cDNA was enzymatically fragmented, end repaired, A-tailed, subjected to a double-sided size selection with SPRIselect beads (Beckman Coulter) and ligated to adaptors provided in the kit. A unique sample index for each library was introduced through 14 cycles of PCR amplification. Indexed libraries were subjected to a second double-sided size selection, and libraries were then quantified using Qubit fluorometric quantification (ThermoFisher Scientific). The quality was assessed on an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer, obtaining an average library size of 437 bp. Libraries were diluted to 10 nM and clustered on a HiSeq4000 at 1 nM on a pair end read flow cell and sequenced for 26 cycles on R1 (10x barcode and the UMIs), followed by 8 cycles of I7 Index (sample Index), and 98 bases on R2 (transcript). Primary processing of sequencing images was done using Illumina’s Real Time Analysis software (RTA). 10x Genomics Cell Ranger Single Cell Software suite v3.0.2 (https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/what-is-cell-ranger) was used to perform sample de-multiplexing, alignment (mm10), filtering, UMI counting, single-cell 3’end gene counting and performing quality control using the manufacturer parameters.

Libraries were sequenced to an average of 250 million reads per sample with average of 2,853 cells per sample and an average depth of 100 thousand reads per cell (resulting in 77% average sequencing saturation). Sequencing captured 14,625 mean genes per library, 1,448 median genes per cell and 3,654 median unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) per cell (Figure S4A and Table S1). Seurat package was used to identify genes and cells suitable for inclusion in the analysis and to identify the most variable genes (Stuart et al., 2019). Only genes that were present in at least 10 cells, and cells that had at least 500 and at most 5000 unique genes expressed, and mitochondrial gene expression fraction less than 5%, were considered for the analysis (Figure S4A and Table S1). Most variable 3,000 genes were identified using variance stabilizing transform in Seurat. Cells were clustered using graph-based clustering on the first 30 principal components with a resolution of 0.5. Dimensionality reduction was performed using UMAP on the network using 15 nearest neighbors on normalized gene expression values (n=10,334 cells Ezh2Y641F and 6,782 WT cells). Principal pseudotime was calculated using Slingshot and dyno package (Saelens et al., 2019; Street et al., 2018). Scores for pathways related gene sets were projected onto cells by taking the z-score of each gene and summing them (Hanzelmann et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2008). In the case where both up- and downregulated genes were reported for a pathway both signatures were merged by summing the normalized upregulation score and the downregulation score together. For pathways gene signatures from MSigDB and as well as manually defined gene sets from literature were used (Liberzon et al., 2011). Using this procedure the clusters that correspond to plasmablasts were identified and removed for the secondary analysis. After removing plasmablasts the most variable genes were recalculated and the above protocol was repeated using only the GC B cells.

Bulk RNA-seq and analysis

Naive B cells (B220+CD38+Fas-IgD+), centroblasts (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4hiCD86lo) and centrocytes (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4loCD86hi) were sorted from spleens of 4 Cγ1-cre and 4 Ezh2(Y641F)fl/WT;Cγ1-cre mice 8 days after SRBC immunization. A minimum of fifty thousand and maximum of one hundred thousand cell type per spleen were collected into Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA was extracted following the manufacturer instructions and RNA quality was evaluated using Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer. Library preparation, sequencing and post-processing of the raw data was performed at the Epigenomics Core at Weill Cornell Medicine. Samples that passed the quality control (RNA Integrity Number ≥8) were subjected to library preparation using the Illumina TruSeq RNA sample kits, according to the manufacturer. Briefly, poly A+ RNA was purified from 100 ng of total RNA with oligo-dT beads. Purified mRNA was fragmented with divalent cations at elevated temperature, to ~200 bp. Following dscDNA synthesis, the double stranded products are end repaired, followed by addition of a single ‘A’ base and then ligation of the Illumina TruSeq adaptors. The resulting product was amplified with 15 cycles of PCR. Libraries were validated using the Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer and Quant-iT™ dsDNA H S Assay (Life Technologies). Each library was made with a unique Index sequence and libraries were pooled for sequencing. The pool was clustered at 6.5 pM on a single end read flow cell and sequenced for 50 cycles on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 to obtain ~80 million reads per sample. Primary processing of sequencing images was done using Illumina’s Real Time Analysis software (RTA) as suggested by Illumina. CASAVA 1.8.2 software was used to perform image capture, base calling, demultiplexing samples and generation of raw reads and respective quality scores. Adapter removal was performed using cutadapt and Trim Galore! (v0.4.1; www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/). Reads were aligned with STAR transcriptome aligner (v2.5.1b, (Dobin et al., 2013) using two-pass alignment to mm10 genome and Gencode M12 gene reference (Frankish et al., 2019). Reads quantification was performed using subread featureCounts (Liao et al., 2014). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 on gene counts (Love et al., 2014) comparing the mutant to WT in centroblasts and centrocytes. Genes with fold-change>1.5 and p<0.01 after adjusting for multiple testing using Benjamini-Hochberg correction were taken as differentially expressed (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). See Table S2 for differentially expressed genes. For normalized expression, gene counts were normalized using TMM (Robinson and Oshlack, 2010). A similar approach was taken to compare each of WT and mutant samples in centroblasts and centrocytes to WT naive B cells. Clustering to define modules was performed on standardized log2 fold-change values relative to naive B cells using fuzzy c-means clustering with 8 clusters and fuzzifier parameter as selected by Schwämmle-Jensen method (Schwammle and Jensen, 2010). See Table S2 for gene lists within each module. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using fgsea by ranking the genes on the resulting log2 fold-change statistic from DESeq2 and calculating enrichment on the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) entries (Liberzon et al., 2011; Subramanian et al., 2005). Pathway analysis was performed using PAGE algorithm (Goodarzi et al., 2009). See Table S3 for gene lists within each pathway.

ChIP-seq and analysis

Between 50,000 and 100,000 centroblasts (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4hiCD86lo) and centrocytes (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4loCD86hi) were sorted from spleens of 3 Cγ1-cre and 3 Ezh2(Y641F)fl/WT;Cγ1-cre mice 8 days after SRBC immunization. Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde and cell pellets were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. MicroChIP was performed using TrueMicroChip kit (Diagenode) according to manufacturer instructions with following modifications. For each replicate, ~20,000 cells were pooled together with 1 million Drosophila Kc167 cells in 1 ml total volume and processed using Covaris E220E sonicator at peak power 140, duty factor 5, 5 cycles/burst, 20 minutes per sample. The sonicated samples were then cleared by 10 minutes centrifugation and mixed with 20 µg antibody (anti-H3K27me3, Cell Signaling 9733), and incubated overnight with rotation at 4°C. Complexes were pulled down using Protein A Dynabeads (ThermoFisher Scientific), washed and de-crosslinked with kit buffers, and DNA was isolated using standard phenol-chloroform procedure. Libraries were prepared using MicroPlex Library preparation kit (Diagenode), with 8 cycles of amplification, and cleaned up using AMPureXP beads (Beckman Coulter). Libraries were validated using Agilent High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape and pooled for sequencing using Illumina NextSeq 500, 1x75 bp (Rockefeller University Genomics Resource Center). Resulting .fastq files were aligned to mouse mm10 and Drosophila dm6 genomes using bwa-mem function of the BWA suite. ChIPseq data was normalized to dm6 spike-in reads using CompChIPseq algorithm, an analysis approach developed by (Blanco et al., 2019), which performs local cyclic Loess regression of spike-in reads to accurately normalize ChIP-seq data in a genome-wide manner. Read density heat maps were generated using DeepTools suite (Ramirez et al., 2014). Log2 ratios were calculated using normalize read counts in promoter regions (TSS +/-5kb) and plotted using denstrip R package with gamma value=4 (Jackson, 2008). ChIPseq peaks were called using the SICER algorithm (Xu et al., 2014) on pooled BAM files from all respective replicates (fold-change>2, q<0.01). See Table S4 for ChIP-seq peaks location. To determine the distance between de novo H3K27me3 promoters and the rest of H3K27me3 marked promoters, for each Ezh2Y641F de novo H3K27me3-occupied TSS, the genomic distance to the nearest H3K27me3-occupied TSS was computed. The genomic distance between all RefSeq TSS was then computed. To test if the median distance between H3K27me3 TSS was shorter than expected given the distances between TSSs, we randomly sampled, without replacement, n=1000 sets of TSS with the same size as Ezh2Y641F de novo H3K27me3-occupied TSS and computed the median distance between TSS for each set. The proportion of these median distances that exceeded the median distance between H3K27me3-occupied TSS was used to determine the empirical p-value.

qChIP

Between 50,000 and 100,000 centrocytes (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4loCD86hi) were sorted from spleens of 3 Cγ1-cre and 3 Ezh2(Y641F)fl/WT;Cγ1-cre mice 8 days after SRBC immunization. Cells were subjected to H3K27me3 microChIP as described in “ChIP-seq”. ChIP DNA was amplified by real-time quantitative PCR using SyberGreen (Applied Biosystems) on QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and the primers in Table S5.

RT-qPCR

Between 50,000 and 100,000 naive B cells (B220+CD38+Fas-IgD+), centroblasts (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4hiCD86lo) and centrocytes (B220+CD38-Fas+CXCR4loCD86hi) were sorted from spleens of 4 Cγ1-cre and 4 Ezh2(Y641F)fl/WT;Cγ1-cre mice 8 days after SRBC immunization. RNA was prepared using Trizol extraction (Invitrogen). cDNA was prepared using cDNA synthesis kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and detected by fast SyberGreen (Applied Biosystems) on QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the primers in Table S5. We normalized gene expression to Hprt1, Rpl13 or Gapdh, according to the level of expression, and expressed values using the ∆CT method. Results were represented as fold expression with the standard deviation for 2 series of triplicates.

Histone mass spectometry

Histone extraction and preparation.

Histones were extracted by direct sorting of GC and naive B cells into H2SO4 and cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 4,000 x g for 5 minutes. Histones were precipitated from the supernatant by the addition of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at a final concentration of 20% (v/v) overnight at 4 °C. Following centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 5 minutes, histone pellets were washed once with 0.1% HCl in acetone then 100% acetone with centrifugation at 15,000 x g for 5 minutes. Histones were dried briefly in a fume hood and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Derivatization and digestion was modified from (Garcia et al., 2007). Dried histones were resuspended in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (10 µL). Sodium hydroxide (5 µL) was added immediately followed by the addition of propionic anhydride (20 µL, 1:3 dilution in isopropanol). The pH was adjusted to 8 with additional sodium hydroxide then incubated at 52°C for 1 hour before drying to completion in a SpeedVac concentrator. Histones were digested for 16 hours with 1 µg trypsin, dried in a Speedvac concentrator and subjected to a final propionylation as described above.

Targeted mass spectrometry.