Abstract

Objectives

The National Early Warning Score (NEWS) was originally developed to assess hospitalised patients in the UK. We examined whether the NEWS could be applied to patients transported by ambulance in Japan.

Design

This retrospective study assessed patients and calculated the NEWS from paramedic records. Emergency department (ED) disposition data were categorised into the following groups: discharged from the ED, admitted to the ward, admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) or died in the ED. The predictive performance of NEWS for patient disposition was assessed using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Patient dispositions were compared among NEWS-based categories after adjusting for age, sex and presence of traumatic injury.

Setting

A tertiary hospital in Japan.

Participants

Overall, 2847 patients transported by ambulance between April 2017 and March 2018 were included.

Results

The mean (±SD) NEWS differed significantly among patients discharged from the ED (n=1330, 3.7±2.9), admitted to the ward (n=1263, 6.3±3.8), admitted to the ICU (n=232, 9.4±4.0) and died in the ED (n=22, 11.7±2.9) (p<0.001). The prehospital NEWS C-statistics (95% CI) for admission to the ward, admission to the ICU or death in the ED; admission to the ICU or death in the ED; and death in the ED were 0.73 (0.72–0.75), 0.81 (0.78–0.83) and 0.90 (0.87–0.93), respectively. After adjusting for age, sex and trauma, the OR (95% CI) of admission to the ICU or death in the ED for the high-risk (NEWS ≥7) and medium-risk (NEWS 5–6) categories was 13.8 (8.9–21.6) and 4.2 (2.5–7.1), respectively.

Conclusion

The findings from this Japanese tertiary hospital setting showed that prehospital NEWS could be used to identify patients at a risk of adverse outcomes. NEWS stratification was strongly correlated with patient disposition.

Keywords: early warning scores, ambulance, prehospital

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first retrospective study to evaluate the efficacy of prehospital National Early Warning Score (NEWS) calculated based on vital signs described by paramedics in Japan.

The sample number in this study was larger than that in a previous study; therefore, it functions as an external validation of prehospital NEWS for predicting outpatient disposition at an emergency department.

This study was conducted in an ageing society in Japan, and the results will likely be generalisable to other ageing societies.

This study also examined how adjustment for age, sex and trauma changed the association between the NEWS and outcomes.

Because the study was conducted in a single centre, the findings may not be generalisable to all Japanese populations.

Introduction

The early warning score (EWS) was developed as a guide for the quick assessment and early diagnosis of acute illness in patients admitted to hospitals.1 It was intended to serve as a track and trigger tool for consistent assessment of illness severity and to provide useful baseline data to evaluate a patient’s clinical progress.2

In 2012, the Royal College of Physicians developed the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) to improve the early detection rates of clinical deterioration. The NEWS was initially used to predict illness severity and deterioration in a hospital setting.3 Since 2015, it has been implemented across counties in the West of England to compute the NEWS for all patients before referral to acute care facilities.4 Furthermore, a previous study performed in-depth qualitative interviews of healthcare professionals to identify barriers and facilitators of NEWS implementation in prehospital, primary care and community settings.5 In this study, participants indicated that the NEWS could support clinical decision-making for the escalation of care and provide a clear means of communicating clinical acuity among clinicians and different healthcare organisations.

A recent review showed that very low and high EWS could distinguish among patients who were unlikely and likely to deteriorate in the prehospital setting, respectively.6 Some studies have also begun to extensively apply the NEWS in prehospital settings and emergency departments (ED), and most of these studies have used mortality as a primary outcome for evaluating prehospital NEWS.7–13 In contrast, in 2017, Shaw et al used subsequent discharge disposition as the primary outcome.7

It is not clear how factors such as healthcare systems, geographical conditions and race affect the EWS. Three Asian countries—Iran, Hong Kong and China—have published reports on the use of EWS in prehospital settings11–13; however, its use has not yet been reported in Japan.

While life expectancy in Japan is high, the country also faces the problem of an ageing society.14 The proportions of people aged 65 years and higher in Iran, China, Hong Kong, the UK and Japan are 5.6%, 9.6%, 15.1%, 17.8% and 26.3%, respectively.15 Given the rapidly ageing society in Japan, the number of ambulance deliveries for patients with multiple comorbidities is only expected to increase. However, studies evaluating the NEWS in prehospital settings in ageing countries are limited. Thus, this study examined the use of NEWS in the ageing society of Japan and its application during emergency transportation.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the study design.

Setting and population

This observational cohort study was conducted at St Marianna University School of Medicine, a 1200-bed tertiary teaching hospital in Kawasaki city, Kanagawa Prefecture. Kawasaki city covers a geographical area of 144 km2 and has a population of 1.5 million. The estimated number of emergency ambulance transportations in this city is 72 000 incidents per year.16 There are 25 emergency hospitals in the city, of which St Marianna Medical University Hospital is the largest.17 Between April 2016 and March 2017, 5640 of patients were transported by ambulance, while 16 922 patients were walk-in.

In principle, paramedics decide which hospital they should transport the patient to, based on the severity of the patient’s condition and the distance to the hospital.18

Participants

This study enrolled patients transported to our hospital by ambulance between April 2016 and March 2017. The requirement for obtaining patients’ informed consent was waived because the data were anonymised. The following patients were excluded: (1) those aged <16 years; (2) pregnant patients; (3) patients transported from another hospital because it was not a prehospital setting (this rule was the same for a previous study10); and (4) cardiopulmonary arrest cases.

Data sources

Prehospital and hospital data were collected separately and integrated. Prehospital data were recorded on paper by paramedics at the scene and data on chief complaints and vital signs, including heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, arterial oxygen saturation, temperature and consciousness, were collected.

Chief complaints were categorised based on the Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System categories as previously described.8 However, in Japan, these codes have not been used in practice. The appropriate code was added using the chief complaint item recorded on the paper by the paramedics after transportation.

The patients were categorised into the following four groups based on their disposition as described previously7: discharge from the ED, admission to the ward, admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) or death in the ED.

National Early Warning Score

The NEWS ranges from 0 to 20, with each vital sign scored from 0 to 3. When a patient is administered supplementary oxygen, two points are added to the total score (online supplementary table 1).3 We calculated the total post hoc NEWS based on the vital signs.

bmjopen-2019-034602supp001.pdf (192.5KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows V.25.0 was used for statistical analysis. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Patients’ age, sex and presence of traumatic injury were summarised by four categories based on their ED disposition and chief complaints made during the ambulance call. The distributions of the NEWS were compared between the ED disposition groups using Kruskal-Wallis tests.

We assessed the discriminatory ability of the continuous-scale NEWS to predict patient ED dispositions using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under the curves (C-statistics). For the ordered nature of ED disposition outcomes (discharge from the ED, ward or ICU admission, or death in the ED), we combined the outcomes as follows: (1) ward or ICU admission or death in the ED; (2) admission to the ICU or death in the ED; and (3) death in the ED. These classifications were considered to provide more interpretable results than the analysis of each disposition outcome alone.

To obtain candidate cut-off values for hospital disposition, we started with Youden’s Index (sensitivity+specificity−1). Among these ranges, we carefully chose high/middle-risk and middle/low-risk cut-off points that appropriately reflected clinical requirements (online supplementary table 2).

Finally, two combined outcomes (ICU admission or death in the ED and death in the ED) were compared among the NEWS-based categories without and after adjusting for age, sex and the presence of traumatic injury.

Results

Participants’ baseline characteristics

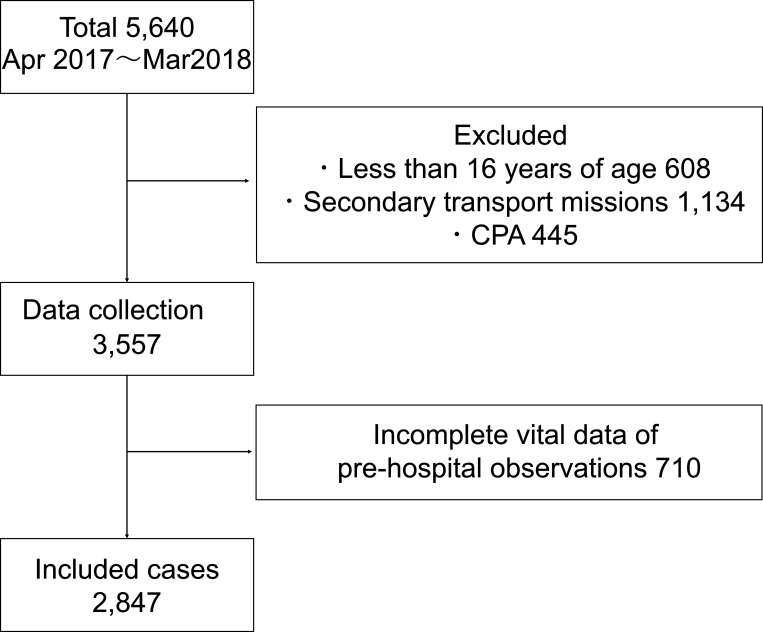

Overall, 5640 patients were transported to the hospital by emergency ambulances during the study period. After exclusion, 2847 cases were selected for analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the included cases. CPA, cardiopulmonary arrest.

In the current study, there were 20% incomplete data for which no vital signs were obtained. The vital signs of patients transported from Kawasaki city were written on paper by paramedics and given to hospital staff. However, the vital signs of patients transported from other areas (Tokyo, Yokohama next to Kawasaki) were not written on the report after transportation. These data could not be accessed owing to privacy regulations. We excluded 20% of the data for which no vital signs were obtained; however, the only difference was the area from which the patients were transported; thus, we assumed that there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between these patients and the other 80% of patients.

Of 2847 cases, 1330 (46.7%) were discharged from the ED, 1263 (44.4%) were admitted to the ward, 232 (8.1%) were admitted to the ICU and 22 (0.8%) died in the ED. The mean (±SD) age of the participants was 66.5±19.6 years, and the median age was 73 years (lower to upper quartile: 53–82), with bimodal (modes around 44 and 82) and asymmetric distributions rather than unimodal and symmetric distributions. Male patients comprised 53.5% of the participants. The mean ages of the patients discharged from the ED, admitted to the ward, admitted to the ICU and died in the ED were 63.9±20.3, 68.8±18.8, 68.5±18.7 and 72.6±20.2 years, respectively (p<0.001) (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics by patient disposition outcomes

| All (n=2847) |

Patient disposition | |||||||||

| Discharged from the ED (n=1330) |

Admitted to the ward (n=1263) |

Admitted to the ICU (n=232) |

Died in the ED (n=22) |

|||||||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 66.5±19.6 | 63.9±20.3 | 68.8±18.8 | 68.5±18.7 | 72.6±20.2 | |||||

| Male (%) | 53.5 | 49.2 | 56.1 | 64.2 | 50 | |||||

| Non-trauma (%) | 88.3 | 85.9 | 90.4 | 89.2 | 100 | |||||

| Chief complaint* | % | Cases | % | Cases | % | Cases | % | Cases | % | Cases |

| Sick person | 19.8 | 564 | 24 | 319 | 17.4 | 220 | 8.6 | 20 | 22.7 | 5 |

| Subject unconscious | 13.8 | 392 | 8.6 | 114 | 16 | 202 | 28 | 65 | 50 | 11 |

| Breathing difficulty | 13.3 | 379 | 8.6 | 114 | 17.5 | 221 | 18.1 | 42 | 9.1 | 2 |

| Traumatic injuries | 8.3 | 236 | 11.1 | 148 | 6.4 | 81 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Chest pain | 5.9 | 167 | 6.3 | 84 | 4.8 | 60 | 8.6 | 20 | 13.6 | 3 |

*A list of chief complaints containing the top three in each category.

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

The main chief complaints of the patients at the time of calling an ambulance were a sick person (19.8%), unconsciousness (13.8%) and breathing difficulty (13.3%) (table 1). The other chief complaints included traumatic injury (8.3%), stroke (7.4%), abdominal pain (6.6%), haemorrhage (5.9%), chest pain (5.9%), headache (4.1%), back pain (3.3%) and drug overdose (3.1%). The chief complaints of each patient disposition group are presented in table 1 and in online supplementary table 3.

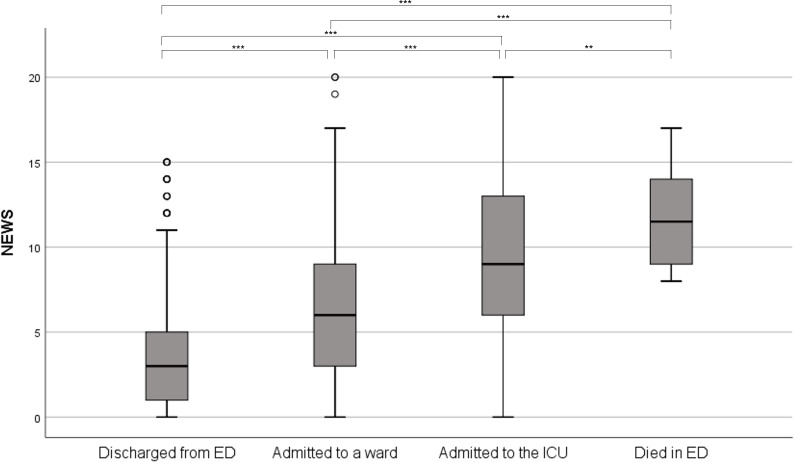

NEWS for each patient disposition group

The box plots in figure 2 illustrate the distributions of prehospital NEWS for each disposition group. As shown in online supplementary table 4, the median and mean (±SD) NEWS increased for groups discharged from the ED (3 and 3.7±3.9), admitted to the ward (6 and 6.3±3.8), admitted to the ICU (9 and 9.4±4.0) and died in the ED (11.5 and 11.7±2.9). The distributions differed significantly among the patient disposition groups according to the Kruskal-Wallis test (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Boxplots of NEWS by patient disposition outcomes, and results of pairwise Wilcoxon tests. **P<0.01, ***p<0.001. ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

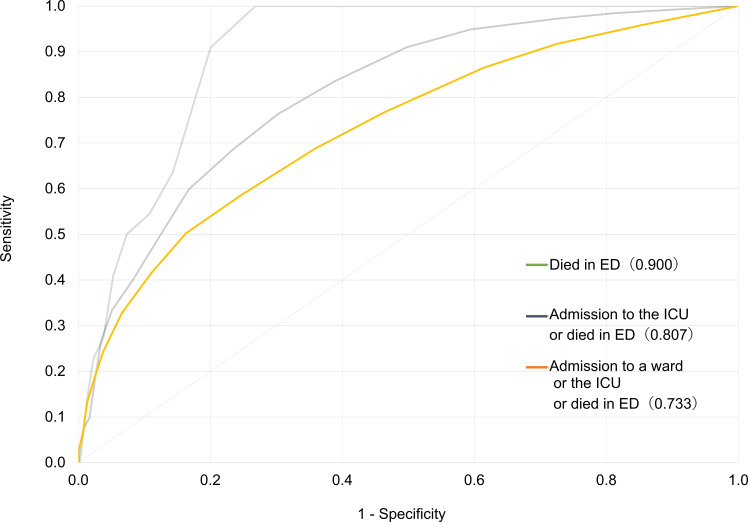

Discriminative performance of the NEWS in the prehospital setting

Figure 3 shows the ROC curves for patient disposition combined outcomes using a continuous-scale NEWS. The areas under the ROCs (95% CI) for prehospital NEWS for ward/ICU admission or death in the ED, ICU admission or death in the ED, and death in the ED were 0.73 (0.72–0.75), 0.81 (0.78–0.83) and 0.90 (0.87–0.93), respectively.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the prediction of NEWS for combined patient disposition. ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

Cut-off NEWS for clinical risk categories

Based on the coordinate points of the ROC curve (online supplementary table 2), the high-risk cut-off was set between NEWS 6 and 7 (score 6.5: sensitivity of 0.76 and 1—specificity of 0.30 for admission to the ICU or death in the ED), and the low-risk cut-off was set between 4 and 5 (score 4.5: sensitivity of 0.69 and 1—specificity of 0.36 for the ward/ICU admission or death in the ED). The selection of these values is described in online supplementary table 2.

Accordingly, we adopted the categorisation scheme for low (NEWS ≤4), medium (5 or 6) and high (≥7) risks.

Risk category by patient disposition group

Table 2 shows that a higher NEWS was associated with deteriorating patient disposition. In the low-risk group (n=1327), the highest proportion of patients was discharged from the ED (n=853, 64.3%), followed by those admitted to the ward (n=451, 34.0%), admitted to the ICU (n=23, 1.7%) and died in the ED (n=0, 0%). Conversely, patients in the high-risk group (n=979) had a greater probability of being admitted to the ward (n=568, 58.0%), being admitted to the ICU (n=172, 17.6%) and dying in the ED (n=22, 2.2%). Among those who died in the ED, 100% (n=22) of the participants were categorised as high risk.

Table 2.

Distributions of patient disposition outcomes by risk categories based on NEWS

| NEWS clinical risk level |

Patient disposition | ||||

| Discharged from the ED | Admitted to the ward | Admitted to the ICU | Died in the ED | All | |

| Low risk (score 0–4) |

64.3% (n=853) |

34.0% (n=451) |

1.7% (n=23) |

0.0% (n=0) |

100% (n=1327) |

| Medium risk (score 5–6) |

48.1% (n=260) |

45.1% (n=244) |

6.8% (n=37) |

0.0 % (n=0) |

100% (n=541) |

| High risk (score ≥7) |

22.2% (n=217) |

58.0% (n=568) |

17.6% (n=172) |

2.2% (n=22) |

100 % (n=979) |

| Total | 46.7 % (n=1330) |

44.4% (n=1263) |

8.1% (n=232) |

0.8% (n=22) |

100% (n=2847) |

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

Relationship between NEWS risk level and outcome

Binary logistic regression models were used to further examine the relationship between the NEWS risk category and combined patient disposition outcomes (table 3; note that death in the ED occurred only in the high-risk group and we did not perform logistic analysis for death in the ED). ICU admission or death in the ED in the medium-risk group (OR 4.2; 95% CI 2.5 to 7.1, p<0.001) and the high-risk group (OR 13.8; 95% CI 8.9 to 21.6, p<0.001) increased significantly compared with that in the low-risk group even after adjusting for age, sex and trauma. Similarly, admission to the ward, ICU, or death in the ED in the medium-risk group (OR 1.9; 95% CI 1.6 to 2.4, p<0.001) and the high-risk group (OR 6.1; 95% CI 5.0 to 7.3, p<0.001) increased significantly compared with that in the low-risk group.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of the association between combined patient disposition outcomes and NEWS risk category

| Unadjusted | Age, sex and trauma adjusted | ||||||

| Event % | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Event 1. Admission to the ICU or death in the ED | |||||||

| NEWS risk | |||||||

| Low | 1.7 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref | ||

| Medium | 6.8 | 4.16 | 2.45 to 7.07 | <0.0001 | 4.18 | 2.46 to 7.11 | <0.0001 |

| High | 19.8 | 14.01 | 9.01 to 21.77 | <0.0001 | 13.83 | 8.88 to 21.6 | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1 | 1.00 to 1.01 | 0.44 | ||||

| Sex | 1.41 | 1.07 to 1.86 | 0.02 | ||||

| Trauma | 1.17 | 0.74 to 1.85 | 0.51 | ||||

| Event 2. Admission to the ward or ICU, or death in the ED | |||||||

| NEWS risk | |||||||

| Low | 35.7 | 1 | Ref | 1 | Ref | ||

| Medium | 51.9 | 1.95 | 1.59 to 2.38 | <0.0001 | 1.94 | 1.58 to 2.39 | <0.0001 |

| High | 77.8 | 6.32 | 5.24 to 7.63 | <0.0001 | 6.06 | 5.01 to 7.33 | <0.0001 |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.99 to 0.99 | 0 | ||||

| Sex | 0.75 | 0.64 to 0.88 | 0 | ||||

| Trauma | 1.17 | 0.91 to 1.50 | 0.22 | ||||

ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; NEWS, National Early Warning Score.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of NEWS in predicting patient disposition in prehospital settings. Our findings indicate that prehospital NEWS could identify critical patients and those at a risk of adverse outcomes. This study did not aim to clarify when to use NEWS to more accurately predict outcomes but rather to verify whether paramedics could determine the severity based on vital sign scores at the time of patient contact.

In recent years, several studies have been conducted on prehospital EWS, and four representative reports7–10 of NEWS have been published. A 2018 study conducted in Finland10 included the highest number of cases (n=12 426) in two hospitals but used short-term mortality rate as the primary outcome. Only a recent study of 287 patients conducted in the UK used patient disposition as the primary outcome.7 The present study examined 2847 cases, which is by far the largest among previous studies to have used patient disposition as the primary outcome.

We found that prehospital NEWS predicted patient disposition in an ED in Japan. Patients categorised as high or medium risk based on their NEWS had increased probabilities of ICU admission or death in the ED. We demonstrated the usefulness of prehospital NEWS in predicting illness severity among participants with different demographic characteristics. Our findings indicate the usefulness of NEWS even in an older population.

Prehospital NEWS has been confirmed to fully predict outpatient disposition, even in ageing societies such as those in Japan. Our results and those of previous studies predicting outpatient disposition in the UK and other countries suggest that prehospital NEWS might be available globally. These findings suggest that the NEWS could be used for ageing societies in other countries in the future.

Previous studies have used risk categories with ORs to calculate early death within 24 or 48 hours of hospitalisation.8 10 Our study is the first to assess outpatient clinical outcomes based on risk category with OR. A 2017 study7 showed that high-risk patients (NEWS ≥7) demonstrated a relatively higher risk for a 1-day mortality rate of 101.5 compared with the low-risk group (NEWS ≤4). Moreover, for medium-risk patients (NEWS 5, 6), we observed an increased risk of 1-day mortality of 4.4 compared with that for low-risk patients, without adjusting for age, sex and trauma.

In our study, the rate of ICU admission or death in the ED in the medium-risk (OR 4.2; 95% CI 2.5 to 7.1, p<0.001) and high-risk (OR 14.0; 95% CI 9.0 to 21.8, p<0.001) groups increased significantly compared with that in the low-risk group, without adjusting for age, sex and trauma (table 3).

This study also examined how adjustment for age, sex and trauma changed the association between NEWS risk and outcomes. The results of the analysis (table 3) suggest that the use of the NEWS was clinically useful regardless of age, sex and trauma.

In a 2016 study conducted in the UK, patients who died or were admitted to the ICU had a higher NEWS than that of patients admitted to the ward or discharged from the ED.7 However, we observed differences in the mean NEWS for all segments (figure 2 and online supplementary table 4). The higher average NEWS in all groups compared with those observed in a previous study could be explained by the fact that the data were collected at a tertiary medical institution. Thus, it is appropriate to use objective scoring systems such as NEWS to compare the attributes of patients transported by ambulance. Furthermore, the cut-off NEWS in the prehospital setting did not differ from that in the hospital setting.3 Several studies have reported the validity of the cut-off values for the NEWS in outpatient settings. Four previous studies7–10 categorised patients into low, medium and high-risk groups according to Royal College of Physicians guidelines.3 After examining the cut-off value in our data, we developed three risk categories. This classification based on our results is the same as that for conventional in-hospital NEWS categories.

According to the definition of NEWS based on in-hospital patients, validation was necessary to confirm the risk classification for out-of-hospital patients. Thus, we evaluated the ROC curves and specified coordinate points. The cut-off NEWS for prehospital assessment were consistent with the definition for in-hospital NEWS prediction (online supplementary table 2). As medical interventions are not applied in the prehospital environment, the cut-off scores for the risk categories will differ from those in the in-hospital environment. Thus, future studies should use larger data sets to confirm this finding.

Some studies in Japan have confirmed the usefulness of EWS in hospital and triage settings.19–22 However, several countries require nationwide in-hospital EWS implementation, and in the UK, this has been widely used in prehospital settings, outpatients and emergency services.4 Paramedics in Japan should directly request the hospital for ambulance acceptance on the scene. However, it is often difficult to obtain hospital acceptance for transportation because the number of transportations has increased each year.17 Furthermore, the time from making the ambulance call until arrival at the hospital is also gradually increasing.23 24 This might delay crucial emergency treatments, which in turn might worsen patient outcomes. NEWS-based risk stratification helps paramedics to understand the severity of the patient’s condition and communicate it accurately to a healthcare professional at the hospital. Earlier identification of critical patients might facilitate earlier resuscitation and appropriate critical care.8

This study used outpatient disposition as the primary outcome. Most previous reports have considered short-term mortality as the primary outcome to assess the usefulness of prehospital NEWS.6 9 10 As it predicts outpatient outcomes in addition to short-term mortality, the NEWS is a very useful tool.

We are also currently analysing the relationship between prehospital NEWS and mortality rate with more extensive data and exploring the possibility of more accurately predicting death by integrating other factors (chief complaints, and so on). This study is the first step towards the implementation of prehospital NEWS as a prehospital triage tool. There is currently no triage tool in the prehospital setting in Japan. The Japan Triage and Acuity Scale is currently used in the outpatient setting, but it does not assume an emergency site. To use prehospital NEWS as a triage tool, additional analysis of ‘false-positive’ and ‘false-negative’ rates is required. It is necessary to clarify what kind of cases are ‘Go home despite high score’ and ‘ICU hospitalization despite low score’. These data should be assessed in a future study.

The strengths of this study are as follows. This study is the first in Japan to show that the NEWS can be used in a prehospital setting to predict patient disposition. Our data set was much larger than that used in a previous study,7 which suggests higher reliability. It is noteworthy that the results obtained by calculating the cut-off values for the out-hospital setting were the same as those obtained for the in-hospital setting.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. This was a retrospective study conducted in a single centre; thus, the findings may not be generalisable to all populations in Japan. Second, while the judgements for deciding the outpatient disposition of each emergency physician were standardised by referring to guidelines, they did not match exactly.

Conclusion

The results of our study suggest the usefulness of NEWS for categorising ED cases on patient arrival by ambulance. The study also showed that elevated NEWS among unselected prehospital patients could be used to predict patient disposition at the ED in Japan. The NEWS has a wide range of uses in prehospital settings. A prospective multicentre study is needed to validate the usefulness of the NEWS in the prehospital setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our department research assistant, Ms Akiko Hosoyama, and our department paramedic, Mr Daigo Ando, for their help in collecting the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: TE, KM, ShiF and YT conceived the research idea and designed the study. TE, ShuF and TN collected the data. TE, TM, JT, TN, NS and TS provided statistical advice on study design and analysed the data. TE and ShiF chaired the data oversight committee. TE, HCH and TY drafted the first version of the manuscript. TE, ShiF and YT take public responsibility for the contents of this paper.

Funding: This work was jointly funded by the St Marianna University School of Medicine Research Grant 2018 and the Yuumi Memorial Foundation for Home Health Care Grant 2017.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The research protocol received approval from the ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of St Marianna University School of Medicine (No 4325).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.Centre for Clinical Practice at N National Institute for health and clinical excellence: guidance. acutely ill patients in hospital: recognition of and response to acute illness in adults in hospital. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK), 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones M. NEWSDIG: the National early warning score development and implementation group. Clin Med 2012;12:501–3. 10.7861/clinmedicine.12-6-501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Physicians TRCo National early warning score (news) standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott LJ, Redmond NM, Garrett J, et al. Distributions of the National early warning score (news) across a healthcare system following a large-scale roll-out. Emerg Med J 2019;36:287–92. 10.1136/emermed-2018-208140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brangan E, Banks J, Brant H, et al. Using the National early warning score (news) outside acute hospital settings: a qualitative study of staff experiences in the West of England. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022528. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel R, Nugawela MD, Edwards HB, et al. Can early warning scores identify deteriorating patients in pre-hospital settings? A systematic review. Resuscitation 2018;132:101–11. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw J, Fothergill RT, Clark S, et al. Can the prehospital national early warning score identify patients most at risk from subsequent deterioration? Emerg Med J 2017;34:533–7. 10.1136/emermed-2016-206115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silcock DJ, Corfield AR, Gowens PA, et al. Validation of the National early warning score in the prehospital setting. Resuscitation 2015;89:31–5. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbott TEF, Cron N, Vaid N, et al. Pre-Hospital national early warning score (news) is associated with in-hospital mortality and critical care unit admission: a cohort study. Ann Med Surg 2018;27:17–21. 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoikka M, Silfvast T, Ala-Kokko TI. Does the prehospital national early warning score predict the short-term mortality of unselected emergency patients? Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2018;26:48. 10.1186/s13049-018-0514-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung SC, Leung LP, Fan KL, et al. Can prehospital modified early warning score identify non-trauma patients requiring life-saving intervention in the emergency department? Emerg Med Australas 2016;28:84–9. 10.1111/1742-6723.12501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebrahimian A, Seyedin H, Jamshidi-Orak R, et al. Physiological-social scores in predicting outcomes of prehospital internal patients. Emerg Med Int 2014;2014:1–5. 10.1155/2014/312189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruan HZY, Tang Z, Li B. Modified early warning score in assessing disease conditions and prognosis of 10,517 pre-hospital emergency cases. Int J Clin Exp Med 2016;9:14554–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell JC How policies change: the Japanese government and the aging Society, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Bank Health nutrition and population statistics, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawasaki city Kawasaki City statistics book, 2017. http://www.city.kawasaki.jp/shisei/category/51-4-15-17-0-0-0-0-0-0.html [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare Emergency medical center rateing in Japan 2018, 2019. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10800000/000496304.pdf

- 18.International Fire Service Information Center Section 5 Ambulance ServiceSystem(1)Implementation of Emergency Medical Services.Section 6 First-aidTreatment Administered by Ambulance Crew Members 2017 In: Extract of the 2017 white paper on fire service, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishijima I, Oyadomari S, Maedomari S, et al. Use of a modified early warning score system to reduce the rate of in-hospital cardiac arrest. J Intensive Care 2016;4:s40560-016-0134-7. 10.1186/s40560-016-0134-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koike T, Nakagawa M, Shimozawa N, et al. The implementation of rapid response system in Japanese hospitals: its obstacles and possible (solutions. JJAAM 2017;28:219–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuriyama A, Ikegami T, Kaihara T, et al. Validity of the Japan acuity and triage scale in adults: a cohort study. Emerg Med J 2018;35:384–8. 10.1136/emermed-2017-207214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuriyama A, Urushidani S, Nakayama T. Five-Level emergency triage systems: variation in assessment of validity. Emerg Med J 2017;34:703–10. 10.1136/emermed-2016-206295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katayama Y, Kitamura T, Kiyohara K, et al. Factors associated with the difficulty in hospital acceptance at the scene by emergency medical service personnel: a population-based study in Osaka City, Japan. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013849. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ambulance Service Planning Office of Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan Effect of first aid for emergency patients, 2019. Available: https://www.fdma.go.jp/publication/rescue/post7.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-034602supp001.pdf (192.5KB, pdf)