Abstract

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability. Protein homeostasis is essential for normal brain function, but little is known about its role in DS pathophysiology. In this study, we found that the integrated stress response (ISR)–a signaling network that maintains proteostasis–was activated in the brains of DS mice and individuals with DS, reprogramming translation. Genetic and pharmacological suppression of the ISR, by inhibiting the ISR-inducing double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase or boosting the function of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF2-eIF2B complex, reversed the changes in translation and inhibitory synaptic transmission and rescued the synaptic plasticity and long-term memory deficits in DS mice. Thus, the ISR plays a crucial role in DS, which suggests that tuning of the ISR may provide a promising therapeutic intervention.

Intellectual disability (ID) affects ~2 to 3% of the human population (1). Recent array-based comparative genomic studies have identified a large number of chromosomal aberrations in individuals with ID (2, 3). Down syndrome (DS) is a chromosomal condition and the most common genetic cause of ID. DS is a substantial biomedical and socioeconomic problem (4), for which there is no effective treatment. Thus, the identification of neuronal targets for the development of pharmacotherapies to treat the memory decline associated with DS is an important goal.

DS results from the presence of an extra copy of human chromosome 21 (CH21; also known as Homo sapiens autosome 21, HSA21) leading to genetic imbalance. Gene expression studies have shown that the overall genome-wide differences between individuals with DS and euploid controls map not only to CH21 but also to other chromosomes (5,6). Thus, the DS phenotype could be caused by widespread pleiotropic dysregulation of gene expression (7). Consequently, most of the focus in the field has been to understand how alterations in the expression of specific genes in CH21 trisomic cells lead to neurodevelopmental dysfunction (8). However, the degree to which defects in protein homeostasis (proteostasis) might contribute to the cognitive deficits associated with DS has remained largely unexplored.

The brain must adapt to stress conditions that occur as a result of numerous environmental and/or genetic factors. The integrated stress response (ISR) is one of the circuits that responds to stress conditions and serves to restore proteostasis by regulating protein synthesis rates (9). The central regulatory hub of the ISR is the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF2, the target of four kinases that are activated in response to different stresses. In its guanosine triphosphatase (GTP)–bound state, eIF2 assembles into the eIF2–GTP–Met-tRNAi ternary complex (TC) that delivers the methionyl initiator tRNA (Met-tRNAi) to the small ribosomal subunit (40S), priming translation initiation (10). After recognition of an AUG codon, GTP is hydrolyzed and the resulting eIF2-GDP leaves the ribosome (GDP, guanosine diphosphate). eIF2-GDP is recycled to the GTP-bound state by eIF2B, which serves as eIF2’s dedicated guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF).

Translational control by the ISR is exerted by phosphorylation of the α subunit of eIF2 (eIF2-P) on a single serine (serine 51), which converts eIF2 from a substrate into an inhibitor of eIF2B: eIF2-P binds more tightly to eIF2B and blocks its GEF activity. Thus, reducing TC formation inhibits general translation (10).

Activation of the ISR in the brains of Ts65Dn mice and individuals with DS

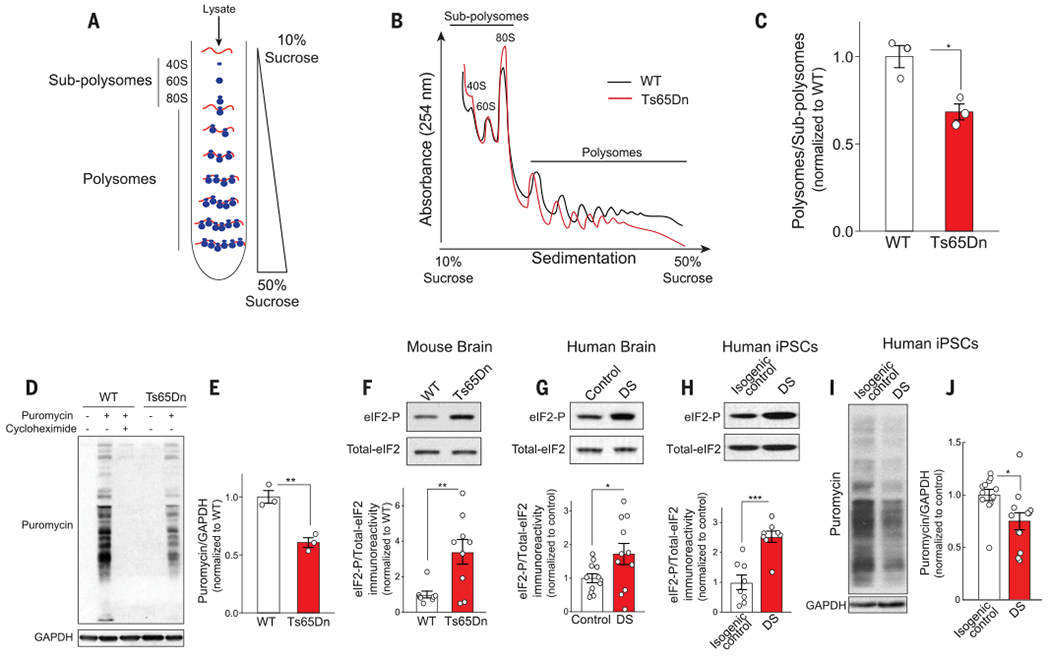

To determine whether protein homeostasis is altered in DS, we first measured protein synthesis rates in the brain of a mouse model of DS (Ts65Dn) that recapitulates the learning and memory deficits of the human syndrome (11,12). Ts65Dn mice are trisomic for approximately two-thirds of the genes orthologous to human CH21. We measured translation in the hippocampus of wild-type (WT) euploid mice and Ts65Dn mice by comparing polysome sedimentation in sucrose gradients and then assessing ribosome and mRNA engagement. In this assay, the position of a given mRNA in the sucrose gradient is determined by the number of associated ribosomes. mRNAs that are poorly translated or not translated at all accumulate near the top, whereas translationally active mRNAs are associated with multiple ribosomes (polysomes) and sediment to the bottom of the gradient (Fig. 1A). Compared with WT mice, mRNA translation in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice was reduced, as indicated by a 32 ± 8% decrease in the polysome/subpolysome ratio (Fig. 1, B and C). An independent translation assay measuring puromycin incorporation into nascent polypeptide chains confirmed that protein synthesis was markedly reduced (39 ± 7%) in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 1, D and E).

Fig. 1. The ISR is activated in the brains of DS mice (Ts65Dn) and individuals with DS.

(A) Schematic of polysome profiling sedimentation. After ultracentrifugation, subpolysomes (40S, 60S, and 80S) and polysomes were separated on the basis of size. (B and C) Representative polysome profile traces (B) and quantification (C) of polysome/subpolysome ratio in the hippocampus of WT and Ts65Dn mice (n = 3 per group, t4 = 4.05, two-tailed Student’s t-test). (D and E) Incorporation of puromycin into nascent peptides was detected using an anti-puromycin antibody. A representative immunoblot (D) and quantification (E) in hippocampal extract from WT and Ts65Dn mice (n = 3 per group, t4 = 5.69). Treatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide was included as control. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase. (F to H) Representative immunoblot and quantification of eIF2-P levels in (F) hippocampal extracts from WT and Ts65Dn mice (n = 8 or 9 per group, t15 = 3.14), (G) postmortem human brain extracts from controls and individuals with DS (n = 11 per group, t20 = 2.10), and (H) human iPSC extracts from an individual with DS (CH21-trisomic, n = 8 per group, t14 = 4.95) compared with its isogenic control. (I and J) Incorporation of puromycin into nascent peptides in iPSCs was detected using an anti-puromycin antibody. A representative immunoblot (I) and quantification (J) in the DS CH21-trisomic iPSCs compared with the isogenic control line (n = 12 per group, t22 = 2.51). “Isogenic control” indicates iPSCs that are diploid for CH21, whereas “DS” indicates iPSCs that are CH21-trisomic. Both lines were derived from the same individual with DS, and the experiment was replicated in 8 to 12 wells per genotype. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To determine the mechanism(s) underlying the reduced translation in Ts65Dn mice, we first asked whether the ISR, a major pathway that regulates translation initiation (9), is activated in the brains of Ts65Dn mice. Consistent with the decrease in overall protein synthesis (Fig. 1, B to E), the ISR was activated in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice, as determined by the increased eIF2-P levels (Fig. 1F). To assess whether these changes were also observed in the human condition, we measured eIF2-P levels in postmortem brain samples from human individuals with DS. We found increased eIF2-P levels in brain samples from human individuals with DS compared with non-DS euploid controls (Fig. 1G and table S1). Moreover, when we reprogrammed a fibroblast line derived from an individual with DS (CCL-54™ from ATCC) into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), we identified one clone that was CH21-trisomic (DS) and another clone from the same individual that was fortuitously euploid (control) (fig. S1). Microsatellite and karyotyping analysis demonstrated that the euploid iPSC clone was isogenic (fig. S1 and see supplementary materials and methods), likely because the individual had mosaic DS, or the extra chromosome was lost during cell line propagation. Although extensive serial passaging (>70 passages) of trisomic-21 iPSCs may have caused cells to become euploid (13), we find this unlikely because karyotyping was performed on passage 9 (fig. S1). Regardless of its etiology, the euploid isogenic line offered the rare opportunity of an ideal isogenic control for our studies. Notably, the ISR was activated in the CH21-trisomic iPSCs but not in the isogenic euploid iPSCs, as indicated by increased eIF2-P levels (Fig. 1H). Similarly, the ISR was also activated in a previously reported CH21-trisomic iPSC line (DS1) (14) compared with its respective isogenic control (DS2U) (fig. S2). As expected from the increased eIF2-P levels (Fig. 1H), protein synthesis was reduced in the DS iPSC line compared with the euploid isogenic control (Fig. 1, I and J). Thus, activation of the ISR in the brains of Ts65Dn mice and human individuals with DS provides a common molecular signature of the condition.

We next examined whether changes in the activity of mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1), which regulates translation initiation rates by a pathway that is distinct and independent from the ISR (15), could also contribute to the decreased translation in the brain of Ts65Dn mice. mTORC1 regulates translation rates by phosphorylating its downstream targets, the ribosomal protein S6, and the translational repressor cap-binding protein eIF4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) (fig. S3A). In the hippocampus of WT and Ts65Dn mice, the phosphorylation states of these mTORC1 targets, as well as that of the cap-binding protein eIF4E [a key translation initiation factor (10)], were indistinguishable (fig. S3, B to G), underscoring the idea that the translation repression in DS mice was likely exerted by ISR activation.

The PKR branch of the ISR is activated in the brain of Ts65Dn mice

In the brain, eIF2 is phosphorylated by three kinases: PKR (double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase), GCN2 (general control non-derepressible 2), and PERK (PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase) (fig. S4A). The fourth ISR kinase, HRI (heme-regulated inhibitor), has been extensively studied in erythroid cells, but little is known about its function in the brain. To examine which eIF2 kinase was responsible for the increase in eIF2-P in Ts65Dn mice, we measured their degree of autophosphorylation, indicative of their activation (16). Phosphorylation of PKR, but not of GCN2 or PERK, was increased in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice (fig. S4, B to G). The unfolded protein response (UPR), which, in addition to PERK, includes the ER stress sensors IRE1 (inositol requiring enzyme 1) and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6), has recently been implicated in DS (17,18). We did not observe changes in the activity of IRE1 and ATF6 in the brains of Ts65Dn mice (fig. S5). Taken together with the fact that PERK was not activated in Ts65Dn mice, our data indicate that the ISR (but not the UPR) is selectively activated in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice.

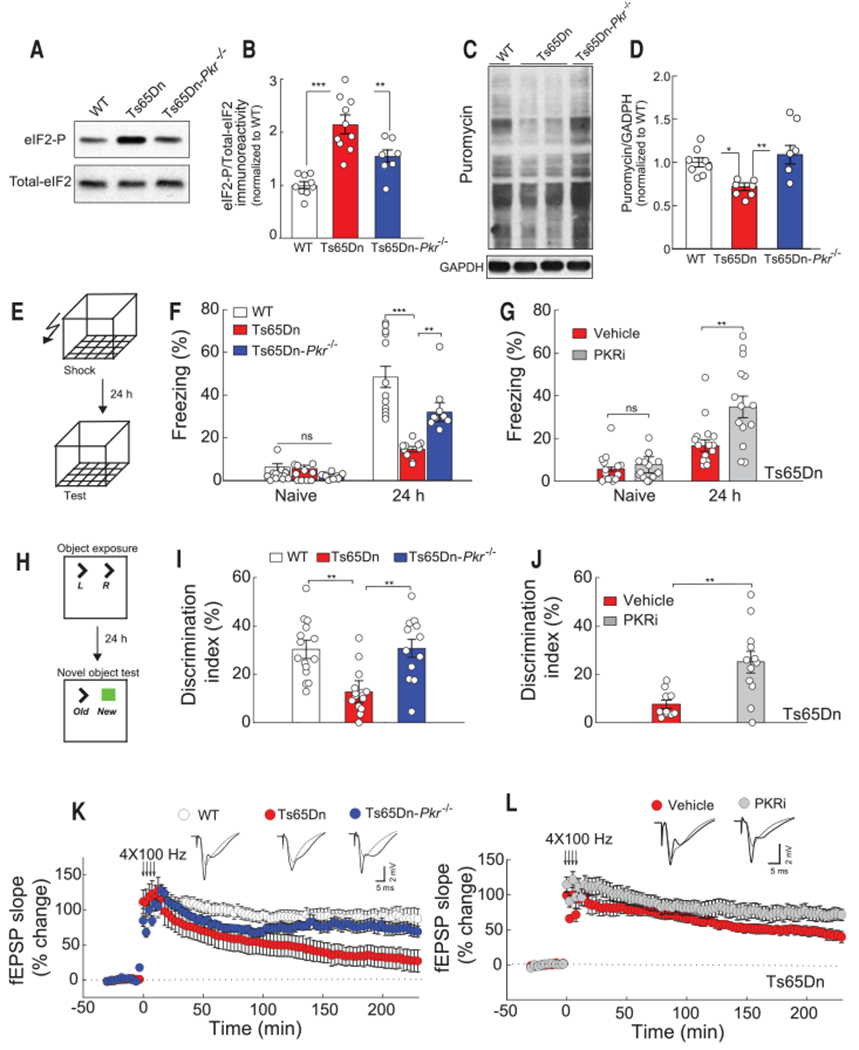

It is notable that in the hippocampus (Fig. 2, A and B) and cortex (fig. S6) of Ts65Dn mice lacking PKR (Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice), eIF2-P levels were reduced compared with Ts65Dn mice. Moreover, genetic inhibition of PKR in Ts65Dn mice (Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice) was sufficient to derepress translation in the brains of Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 2, C and D). Thus, the increased levels of eIF2-P and the resulting sustained translational repression in the brain ofTs65Dn mice are mediated, at least in part, by activation of the PKR branch of the ISR.

Fig. 2. Inhibition of PKR rescues the deficits in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity in Ts65Dn mice.

(A and B) Representative immunoblot (A) and quantification (B) of eIF2-P levels in hippocampal extracts from WT (n = 9), Ts65Dn (n = 10), and Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice [n = 7, F2,23 = 4.12, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)]. (C and D) Incorporation of puromycin into nascent peptides was detected using an anti-puromycin antibody. A representative immunoblot (C) and quantification (D) in hippocampal extracts from WT (n = 8), Ts65Dn (n = 7), and Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (n = 6, F18,2 = 25.16). (E) Schematic of the fear conditioning paradigm. (F) Genetic inhibition of PKR: freezing behavior before (naïve) and 24 hours after training in WT (n = 12), Ts65Dn (n = 10), and Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (n = 9, H = 22.74, one-way ANOVA on ranks). (G) Pharmacological inhibition of PKR: freezing behavior before (naïve) and 24 hours after training in vehicle-treated (n =15) and PKRi-treated Ts65Dn mice (n = 14, t27 = 3.21). (H) Schematic of the object recognition task. (I) Genetic inhibition of PKR: novel object discrimination index 24 hours after training in WT (n = 15), Ts65Dn (n = 15), and Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (n = 12, F2,39 = 11.56). (J) Pharmacological inhibition of PKR: novel object discrimination index 24 hours after training in vehicle-treated (n = 10) and PKRi-treated Ts65Dn mice (n = 12, t20 = 3.48). (K) Genetic inhibition of PKR: L-LTP induced by four trains of high frequency stimulation (HFS, 4 × 100) in WT (n = 10), Ts65Dn (n = 14), and Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (n = 14, H = 15.72, P < 0.05). fEPSP, field excitatory postsynaptic potential. (L) Pharmacological inhibition of PKR: L-LTP induced by 4 × 100 Hz of HFS in vehicle-treated (n = 7) and PKRi-treated Ts65Dn mice (n = 13, U = 41.00, P < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Inhibition of the PKR branch of the ISR rescues the deficits in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity in Ts65Dn mice

Individuals with DS exhibit learning and memory deficits, specifically in hippocampus-dependent tasks (4,19). To investigate whether activation of the ISR contributes to long-term memory deficits in DS mice, we first examined hippocampus-dependent contextual fear memory. In this task, we paired a context (conditioned stimulus, CS) with a foot shock (unconditioned stimulus, US).Twenty-four hours after training, we exposed mice to the CS and measured their fear responses (in this case, freezing behavior) as an index of the strength of their long-term memory (Fig. 2E). Although freezing prior to training was similar in Ts65Dn mice and naïve WT mice, Ts65Dn mice exhibited a significant reduction in freezing behavior 24 hours after a normal training paradigm (two foot shocks at 0.7 mA for 2 s), indicating that their long-term contextual fear memory was impaired (Fig. 2F), as expected (20,21). Genetic ablation of PKR in Ts65Dn mice (Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice) significantly improved their long-term memory (Fig. 2F). A weak training protocol (one foot shock at 0.35 mA for 1 s) is known to induce a better long-term fear memory in Pkr−/− mice compared with their WT littermates (22). However, in response to a normal and more conventional training protocol (two foot shocks at 0.7 mA for 2 s), the one we used to reveal that Ts65Dn mice exhibited impaired memory, Pkr−/− mice and WT littermates showed normal long-term memory (fig. S7A). Thus, genetic deletion of PKR selectively improves long-term memory in Ts65Dn mice. Consistent with these results, treatment with an inhibitor of PKR, PKRi (22), reversed the long-term memory deficits in Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 2G) but had no effect on WT mice (fig. S7B).

To corroborate these findings, we assessed long-term object recognition memory, which is also dependent on the hippocampus (23). In this task, animals need to differentiate between a familiar and a novel object. During acquisition, two identical objects are placed in a box, and mice are allowed to explore them (Fig. 2H). Ts65Dn and WT mice spent, on average, an equal amount of time investigating the identical objects (fig. S8, A and B). When one object was replaced by a novel one 24 hours later, WT mice, relying on their memory for the old object, preferentially explored the novel object.

In contrast, Ts65Dn mice showed markedly reduced object discrimination, indicating that their long-term object recognition memory was impaired (Fig. 2I), as expected (19, 24). Again, these deficits in long-term memory were ameliorated by genetic (Fig. 2I) or pharmacological inhibition of PKR in Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 2J and fig. S8). Both genetic and pharmacological inhibition of the PKR restored behavioral flexibility in Ts65Dn mice in a spontaneous alternation T-maze task (fig. S9).

We next investigated whether the inhibition of PKR could improve the long-term deficits in synaptic plasticity in Ts65Dn mice. To this end, we recorded protein synthesis–dependent late long-term potentiation (L-LTP), which is thought to underlie long-term memory (25), in hippocampal slices. As expected, L-LTP was impaired in slices from Ts65Dn mice, and genetic ablation of PKR rescued the impaired L-LTP in Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 2K). Consistent with these data, treatment with PKRi improved L-LTP in slices from Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 2L). Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of PKR does not further enhance L-LTP induced by four tetanic trains in WT slices (22); hence, the effects of these manipulations were specific to Ts65Dn mice. Thus, in Ts65Dn mice, the cognitive impairment at both the behavioral and synaptic levels is caused, at least in part, by activation of the PKR branch of the ISR.

Inhibition of the ISR rescues the dysregulated translational program in Ts65Dn mice

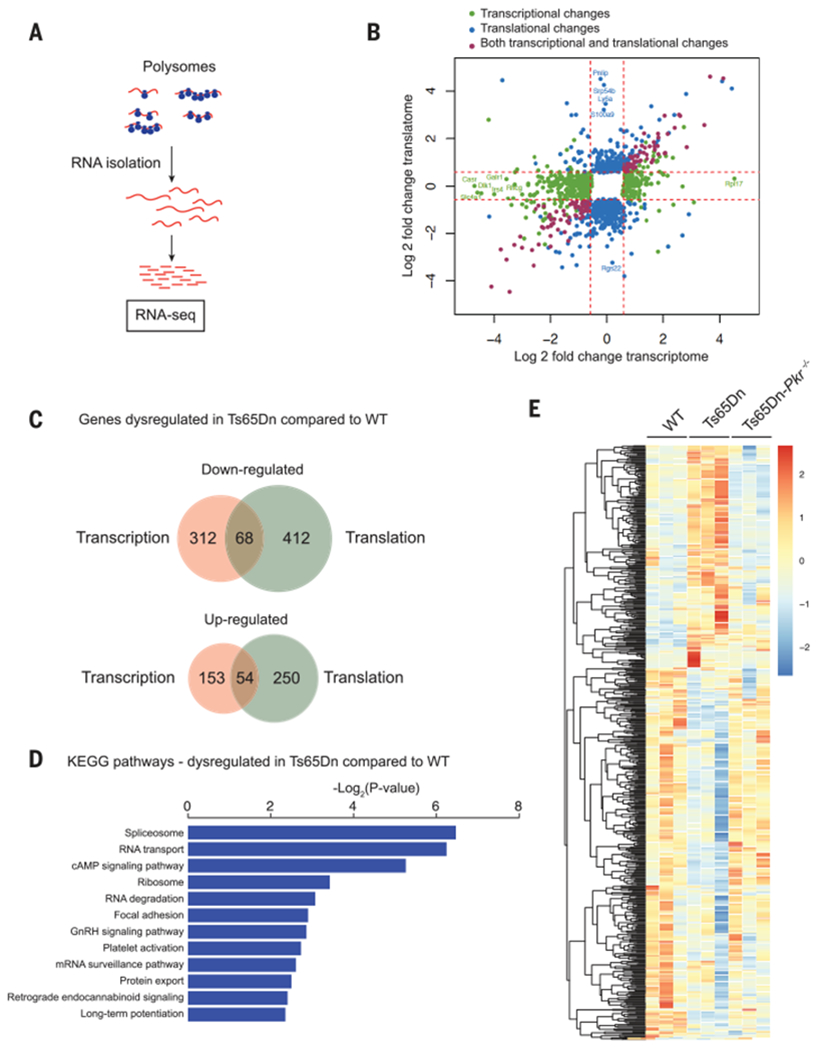

To decipher the translational landscape in the brain of Ts65Dn mice in an unbiased manner, we next compared genome-wide transcriptional changes by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) with translational changes, as determined by the sequencing of polysome-associated mRNA in the brain of WT and Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 3A). As expected, in Ts65Dn mice, numerous genes were transcriptionally and/or translationally dysregulated (Fig. 3, B and C). Gene ontology–term enrichment analysis revealed categories of genes involved in mRNA metabolism, and signaling pathways involved in LTP regulation and memory storage (Fig. 3D). To identify the mRNAs whose translation was altered in Ts65Dn mice, we focused on mRNAs that were not significantly altered at the transcriptional level but were translationally increased or decreased (>1.5-fold) in Ts65Dn mice. We found 662 differences in the brains of Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 3E and table S2). Of note, the expression of >80% of the mRNAs whose association with ribosomes was reduced in Ts65Dn mice was selectively corrected in Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (Fig. 3E, table S2, and fig. S10). Moreover, in an outcome that would be expected of ISR induction, a subset of mRNAs showed increased association with the polysome fraction in Ts65Dn mice but not in Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (Fig. 3E and table S2). Thus, inhibition of the PKR branch of the ISR partially corrects the dysregulated translational program in Ts65Dn mice.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of the ISR rescues the dysregulated translational program in the brain of Ts65Dn mice.

(A) Schematic of the polysome profiling followed by RNA-seq protocol. (B) Scatterplot showing the genes significantly up- or down-regulated (>1.5 fold) at the transcriptional and/or translational levels in the brain of Ts65Dn mice. mRNAs whose expression was not altered between genotypes were removed from the analysis (white square). (C) Venn diagram depicting transcriptionally and translationally up- or down-regulated genes in Ts65Dn mice. (D) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of the genes down-regulated in Ts65Dn mice compared with WT. cAMP, 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone. (E) Heat map showing genes that are significantly up- or down-regulated only at the translational level in Ts65Dn mice and rescued in Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (n = 3 per group).

Inhibition of the ISR rescues the deficits in protein synthesis, long-term memory, and synaptic plasticity in Ts65Dn mice

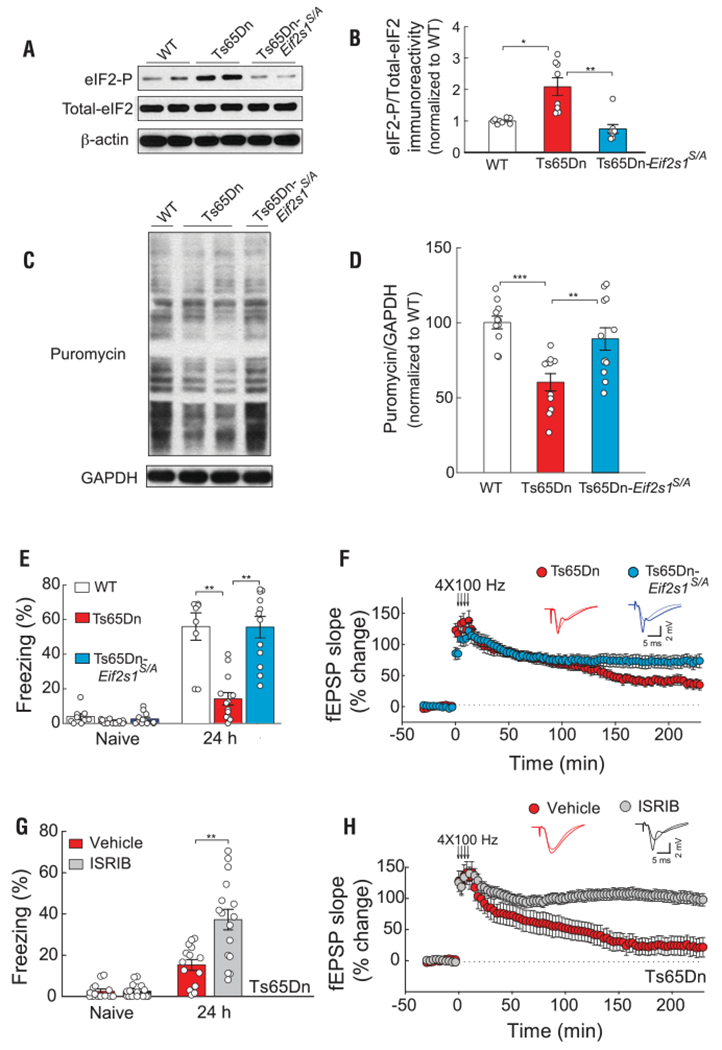

Because (i) eIF2 is the central hub of the ISR and its phosphorylation reduces general protein synthesis rates by inhibiting eIF2B (10), (ii) the ISR is activated in the brains of Ts65Dn mice, and (iii) protein synthesis is a primary node of proteostatic control, and its regulation is crucial for synaptic plasticity and long-term memory formation (26), we reasoned that either direct inhibition of the ISR by reducing eIF2-P levels or promoting the activity of eIF2B should similarly reverse the cognitive deficits in Ts65Dn mice. To test these predictions, we first crossed Ts65Dn mice with heterozygous Eif2s1s/A mice, in which in one of the alleles the phosphorylation site at serine 51 of eIF2a was replaced by nonphosphorylatable alanine. In the brains of Ts65Dn-Ef2s1S/A mice, eIF2-P levels were reduced compared with Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 4, A and B). As expected, direct reduction of eIF2-P levels in Ts65Dn mice (Ts65Dn-Ef2s1S/A mice) restored the aberrant translation (Fig. 4, C and D). More importantly, reduction of eIF2-P levels corrected the deficits in long-term memory (Fig. 4E and fig. S11) and L-LTP in Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 4F) but had no effect on WT mice (fig. S12). Thus, direct reduction of eIF2-P levels and correction of the aberrant translation in Ts65Dn mice rescues their deficits in L-LTP and long-term memory.

Fig. 4. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the ISR rescues the deficits in memory and synaptic plasticity in Ts65Dn mice.

(A and B) Representative immunoblot (A) and quantification (B) of eIF2-P levels in hippocampal extracts from WT (n = 8), Ts65Dn (n = 8), and Ts65Dn-Eif2s1S/A mice (n = 8, H = 15.92). (C and D) Incorporation of puromycin into nascent peptides was detected using an anti-puromycin antibody. A representative immunoblot (C) and quantification (D) in hippocampal extracts from WT (n = 11), Ts65Dn (n = 11), and Ts65Dn-Eif2s1S/A mice (n = 12, F31,2 = 11.23). (E) Genetic inhibition of the ISR: freezing behavior before (naïve) and 24 hours after training in WT (n = 9), Ts65Dn (n = 13), and Ts65Dn-Eif2s1S/A mice (n = 12, F2,31 = 20.25). (F) Genetic inhibition of the ISR: L-LTP induced by 4 × 100 Hz of HFS in Ts65Dn (n = 10) and Ts65Dn-Eif2s1S/A mice (n = 9, t17 = 3.1, P < 0.01). (G) Pharmacological inhibition of the ISR: freezing behavior before (naïve) and 24 hours after training in vehicle-treated (n = 14) and ISRIB-treated (n = 16) Ts65Dn mice (U = 43.50, Mann-Whitney U test). (H) Pharmacological inhibition of the ISR: L-LTP induced by 4 × 100 Hz of HFS in vehicle-treated (n = 8) and ISRIB-treated (n = 9) Ts65Dn mice (t15 = 4.84, P < 0.001). Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To further support these findings, we treated Ts65Dn mice with the small-molecule, druglike ISR inhibitor ISRIB. ISRIB is a potent eIF2B activator that enhances GEF activity by facilitating eIF2B assembly into its decameric holoenzyme, resulting in the reversal of eIF2-P-mediated translational events (27–29). Treatment with ISRIB paralleled the effects of reducing eIF2-P levels genetically: ISRIB rescued the impairment in long-term memory (Fig. 4G) and L-LTP (Fig. 4H) in Ts65Dn mice, although it did not further enhance L-LTP (fig. S13A) or long-term fear memory (fig. S13B) in WT mice. Thus, direct genetic or pharmacological manipulation of the efficacy of the central ISR effector eIF2-P rescues the core deficits in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity in Ts65Dn mice.

Inhibition of the ISR reverses the enhanced inhibitory synaptic transmission in Ts65Dn mice

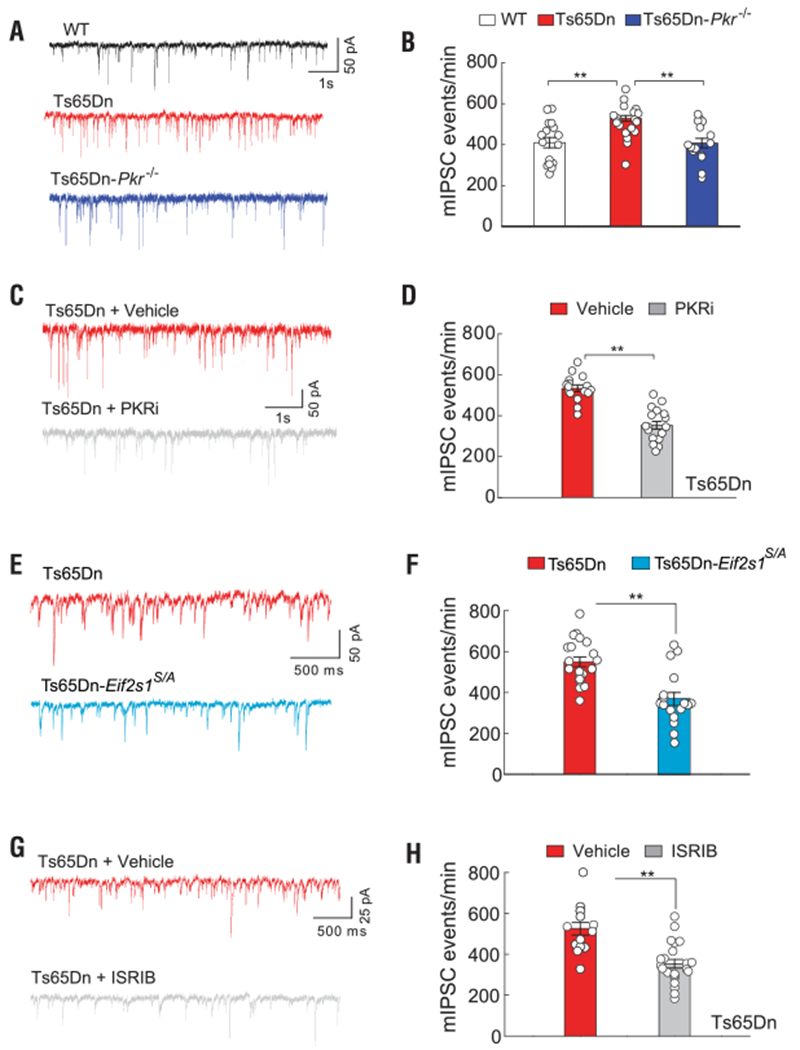

According to previous reports, the deficits in L-LTP and long-term memory in Ts65Dn mice can be attributed to enhanced inhibitory synaptic transmission (24, 30, 31). Thus, we first wondered whether reversal of the PKR-mediated increase in eIF2-P also corrects the abnormally high inhibitory synaptic transmission observed in Ts65Dn mice. As expected, whole-cell recordings showed that inhibitory synaptic transmission was enhanced in Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 5, A and B). Specifically, we observed significant enhancement of the frequency (but not the amplitude) of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) in hippocampal slices from Ts65Dn mice (Fig. 5, A and B, and fig. S14A). The enhanced synaptic inhibition was reduced in hippocampal slices from Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− mice (Fig. 5, A and B), as well as in slices from Ts65Dn mice treated with PKRi (Fig. 5, C and D, and fig. S14B). Excitatory synaptic transmission (determined by measuring miniature excitatory postsynaptic current frequency and amplitude) was not altered in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice (fig. S15). Accordingly, genetic reduction of eIF2-P levels (Fig. 5, E and F, and fig. S14C) or promoting the activity of eIF2B with ISRIB (Fig. 5, G and H, and fig. S14D) reduced the enhanced synaptic inhibition in Ts65Dn mice. Thus, inhibition of the ISR at the level of the initiating kinase PKR or at its central eIF2-eIF2B regulatory hub reverses the enhanced synaptic inhibitory tone in Ts65Dn mice.

Fig. 5. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of the ISR suppresses the increased inhibitory synaptic responses in Ts65Dn mice.

(A and B) Sample traces (A) and summary data (B) show frequency of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons from WT (n = 16), Ts65Dn (n = 20), and Ts65Dn-Pkr−/− (n = 16) mice (F2,49 = 7.76). (C and D) Sample traces (C) and summary data (D) show frequency of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons from vehicle-treated (n = 16) and PKRi-treated (n = 17) Ts65Dn mice (t31 = 7.09). (E and F) Sample traces (E) and summary data (F) show frequency of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons from Ts65Dn (n = 20) and Ts65Dn-Eif2s1S/A mice (n = 17, t35 = 4.58). (G and H) Sample traces (G) and summary data (H) show frequency of mIPSCs in CA1 neurons from vehicle-treated (n = 13) and ISRIB-treated Ts65Dn mice (n = 22, t33 = 6.18). Data are mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01.

The ISR: A molecular switch for long-term memory formation that is turned off in cognitive disorders

It is widely accepted that de novo protein synthesis is required for the formation of long-term memory (32, 33). Research in different species and animal models over the past decade has shown that the ISR is a central proteostasis network causally controlling long-term memory formation. This conclusion is supported by three types of observations. First, genetic or pharmacological suppression of the ISR, by inhibiting the eIF2 kinases or boosting the function of the eIF2-eIF2B complex, facilitates long-term memory formation (26,34). Second, activation of the ISR by inhibiting the eIF2 phosphatases or activating PKR in the hippocampus impairs long-term memory (26,34). Finally, mutations in key components that induce the ISR have been associated with ID (35–37), underscoring the importance of the ISR in mnemonic processes.

In this study, we found that activation of the ISR can account, at least in part, for the core behavioral and neurophysiological abnormalities in Ts65Dn mice, a model system of DS. The potential significance of our findings is highlighted by the observation that the activation of the ISR in the brains of Ts65Dn mice is recapitulated in the brains of individuals with DS, as well as in human CH21-trisomic iPSCs derived from individuals with DS. Thus, ISR-mediated maladapted regulation of protein synthesis may emerge as a central molecular mechanism underlying the cognitive decline associated with DS.

Given the heterogeneity of the genetic perturbations in DS, it seems unlikely that aberrant levels of a single protein are the sole cause of the long-term memory deficits associated with DS. Instead of repairing the expression of individual genes, we correct the overall translational program controlled by the ISR by restoring the function of eIF2-eIF2B, where the ISR exerts its central control. Briefly, we find that inhibition of the activated ISR either upstream at the level of the ISR-inducing kinase PKR, or downstream by manipulating the central ISR signaling hub (eIF2-eIF2B), rescues the cognitive deficits and neurophysiological abnormalities in Ts65Dn mice. By correcting the translational program controlled by the ISR, we overcame a central limitation of the field: It is simply not feasible to determine in vivo the causal role of all of the individually dysregulated proteins in long-term memory formation by overexpressing or knocking them down, which would require hundreds of experiments, and given the current technology, it is certainly not possible to test all combinatorial possibilities. Beyond these limitations, it may prove not to be useful to target specific genes if the ultimate cause of the disorder lies in global proteostasis defects that are sensed as a generic stress condition in the brain by the ISR.

Excessive synaptic inhibition is thought to cause the deficits in hippocampal L-LTP and long-term memory in Ts65Dn mice (24,30,31). We provide genetic and pharmacological evidence that inhibition of the ISR reverses the excessive synaptic inhibition and, in turn, the deficits in L-LTP and long-term memory that likely result from it. Thus, our findings present a model that links these two axes of dysfunction–increased synaptic inhibition, and impaired L-LTP and long-term memory formation–through a single proteostasis network, the ISR.

In addition to reducing enhanced synaptic inhibition, other manipulations and pathways [serotonin, sonic hedgehog (Shh), minocycline, lithium, exercise, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)] have been shown to improve the memory and/or L-LTP deficits in Ts65Dn mice. It is of interest that these manipulations modulate the ISR: minocycline, which has been reported to improve memory in Ts65Dn mice (38) , inhibits the ISR by reducing eIF2-P levels (39). Treatment with fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, improves long-term memory in Ts65Dn mice (40) and has been shown to inhibit the PKR branch of the ISR (41). The synthetic activator of the Shh pathway SAG 1.1 rescues memory in Ts65Dn mice (42). Although it is currently unknown whether SAG 1.1 inhibits the ISR, another pharmacological activator of the Shh blocks the PERK branch of the ISR, resulting in decreased eIF2-P levels (43). Lithium improves LTP and memory in Ts65Dn mice (44) and inhibits the ISR by promoting eIF2B activity (45). Exercise, which has been reported to improve cognitive function in Ts65Dn mice (46), has recently been shown to block the ISR in the hippocampus of an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mouse model (47). Finally, pharmacological induction of BDNF with the recently developed BDNF-mimetic drug 7,8-dihydroxyflavone (DHF) reverses the deficits in LTP and long-term memory in Ts65Dn mice (48), and BDNF inhibits the ISR in neurons by promoting eIF2B activity and reducing eIF2-P levels (49). These observations raise the intriguing possibility that the manipulations reported to reverse the memory deficits in Ts65Dn may do so, either directly or indirectly, by modulating the ISR, which might lie at the crossroad of the different pathways implicated in DS.

Finally, DS is characterized by a high incidence of early onset AD, and activation of the ISR has been implicated in a variety of neuro-degenerative disorders, including AD (50), traumatic brain injury (51), prion disease (52), and myelination disorders (53,54). Thus, genetic or pharmacological modulation of the ISR may emerge as a promising avenue to alleviate a wide range of cognitive disorders resulting from a disruption in protein homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

science.sciencemag.org/content/366/6467/843/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S15

Tables S1 and S2

References (55–68)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Grasso and C. Genero for administrative support, H. Zhou for technical support, and A. Placzek and members of the Costa-Mattioli laboratory for comments on the manuscript. We also thank P. Zhang and A. LaGrone of the Human Stem Cell Core at Baylor College of Medicine for their technical support. Human tissue was obtained from the NIH Neurobiobank at University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the NIH (R01 NS076708) and the generous support from Sammons Enterprises to M.C.-M. and by funding from the NIH (R01HG007538, R01CA193466, and R01 CA228140) to W.L. P.W. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Competing interests: P.W. is an inventor on U.S. Patent 9708247 held by the Regents of the University of California that describes ISRIB and its analogs. Rights to the invention have been licensed by UCSF to Calico. W.L. is a consultant for the Chosen Med. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the supplementary materials, and the RNA-seq data have been deposited in public databases. Accession number of the RNA-seq data is NCBI GEO: GSE138371.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Gardiner K et al. , J. Neurosci 30, 14943–14945 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg C et al. , J. Med. Genet 43, 180–186 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Bokhoven H, Annu. Rev. Genet 45, 81–104 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dierssen M, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 13, 844–858 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Letourneau A et al. , Nature 508, 345–350 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olmos-Serrano JL et al. , Neuron 89, 1208–1222 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonarakis SE, Nat. Rev. Genet 18, 147–163 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haydar TF, Reeves RH, Trends Neurosci. 35, 81–91 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harding HP et al. , Mol. Cell 11, 619–633 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinnebusch AG, Ivanov IP, Sonenberg N, Science 352, 1413–1416 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeves RH et al. , Nat. Genet 11, 177–184 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das I, Reeves RH, Dis. Model. Mech 4, 596–606 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue M et al. , Lab. Invest 99, 885–897 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weick JP et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 110, 9962–9967 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG, Cell 136, 731–745 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavoie H, Li JJ, Thevakumaran N, Therrien M, Sicheri F, Trends Biochem. Sci 39, 475–486 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanzillotta C et al. , J. Alzheimers Dis 62, 347–359 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aivazidis S et al. , PLOS ONE 12, e0176307 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez F, Garner CC, Behav. Brain Res 188, 233–237 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa AC, Scott-McKean JJ, Stasko MR, Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 1624–1632 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deidda G et al. , Nat. Med 21, 318–326 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu PJ et al. , Cell 147, 1384–1396 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vann SD, Albasser MM, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 21, 440–445 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez F et al. , Nat. Neurosci 10, 411–413 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neves G, Cooke SF, Bliss TV, Nat. Rev. Neurosci 9, 65–75 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buffington SA, Huang W, Costa-Mattioli M, Annu. Rev. Neurosci 37, 17–38 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sidrauski C et al. , eLife 2, e00498 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sidrauski C et al. , eLife 4, e07314 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sekine Y et al. , Science 348, 1027–1030 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleschevnikov AM et al. , J. Neurosci 24, 8153–8160 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleschevnikov AM et al. , Neurobiol. Dis 45, 683–691 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kandel ER, Science 294, 1030–1038 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N, Neuron 61, 10–26 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sossin WS, Costa-Mattioli M, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdulkarim B et al. , Diabetes 64, 3951–3962 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borck G et al. , Mol. Cell 48, 641–646 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kernohan KD et al. , Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 6293–6300 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunter CL, Bachman D, Granholm AC, Ann. Neurol 56, 675–688 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi Y et al. , Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 2393–2404 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bianchi P et al. , J. Neurosci 30, 8769–8779 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du RH et al. , Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 19, pyw037 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Das I et al. , Sci. Transl. Med 5, 201ra120 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jimenez-Sanchez M et al. , Nat. Commun 3, 1200 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Contestabile A et al. , J. Clin. Invest 123, 348–361 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bertsch S, Lang CH, Vary TC, Shock 35, 266–274 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kida E, Rabe A, Walus M, Albertini G, Golabek AA, Exp. Neurol 240, 178–189 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia J et al. , Neurosci. Lett 703, 125–131 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parrini M et al. , Sci. Rep 7, 16825 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takei N, Kawamura M, Hara K, Yonezawa K, Nawa H, J. Biol. Chem 276, 42818–42825 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma T et al. , Nat. Neurosci 16, 1299–1305 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chou A et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 114, E6420–E6426 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreno JA et al. , Nature 485, 507–511 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim HJ et al. , Nat. Genet 46, 152–160 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Way SW, Popko B, Lancet Neurol. 15, 434–443 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

science.sciencemag.org/content/366/6467/843/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S15

Tables S1 and S2

References (55–68)