Abstract

Background:

Postoperative pain caused by trauma to nerves and tissue around the surgical site is a major problem. Perioperative steps to reduce postoperative pain include local anesthetics and opioids, the latter of which are addictive and have contributed to the opioid epidemic. Cryoneurolysis is a non-opioid and long-lasting treatment for reducing postoperative pain. However, current methods of cryoneurolysis are invasive, technically demanding, and are not tissue-selective. This project aims to determine if ice slurry can be used as a novel, injectable, drug-free and tissue-selective method of cryoneurolysis and resulting analgesia.

Methods:

We developed an injectable and selective method of cryoneurolysis using biocompatible ice slurry. We used rat sciatic nerve to investigate the effect of slurry injection on the structure and function of the nerve. Sixty-two naïve, male Sprague-Dawley rats were used in this study. Advanced Coherent anti-Stokes Raman Scattering microscopy, light and fluorescent microscopy imaging were used at baseline and at various time-points post-treatment for evaluation and quantification of myelin sheath and axon structural integrity. Validated motor and sensory testing were used for evaluating the sciatic nerve function in response to ice slurry treatment.

Results:

Ice slurry injection can selectively target the rat sciatic nerve. Being injectable, it can infiltrate around the nerve. We demonstrate that a single injection is safe and selective for reversibly disrupting the myelin sheaths and axon density, with complete structural recovery by day 112. This leads to decreased nocifensive function for up to 60 days, with complete recovery by day 112. There was up to median [interquartile range]: 68 [60 to 94] % reduction in mechanical pain response post-treatment.

Conclusion:

Ice slurry injection selectively targets the rat sciatic nerve, causing no damage to surrounding tissue. Injection of ice slurry around the rat sciatic nerve induced decreased nociceptive response from the baseline through neural selective cryoneurolysis.

Introduction

Prolonged postoperative pain is a major problem following common surgical procedures such as total knee arthroplasty, thoracotomy, and herniorrhaphy.1–3 Most prolonged postoperative pain includes a neuropathic component caused by damage to peripheral nerves in the surgical field.4,5 Current treatments include local anesthetics which are short acting, and opioids, which have side effects including addiction.6 As opioid addiction has become an epidemic, developing nonaddictive pain management has become a top medical priority.7 Here we describe a novel method for prolonged nerve block that could be used preemptively to reduce acute postoperative pain and potentially prevent the development of chronic postoperative pain.

Cryoneurolysis describes a process that uses direct cooling to reversibly inhibit peripheral nerve function for weeks to months. Cryoneurolysis has emerged as an addition to multimodal analgesic regimen for postoperative pain control.8–11 The technique typically uses a needle or cryoprobe for contact cooling of the target peripheral nerve, at temperatures of –60°C or below.9 This extremely cold temperature is destructive to any tissue, making the treatment non-selective.9,12,13 This method is invasive, operator-dependent, and time-consuming, thus limiting the use as a pain treatment modality.9,12 However, given the potential of cryoneurolysis, a better approach is needed to increase its use for pain.

We developed an injectable ice slurry for the selective cryoneurolysis of peripheral nerves that overcomes some of the limitations of the currently available methods. Ice slurry injection was developed following our observation that controlled topical skin cooling causes a prolonged, reversible reduction of sensation to painful mechanical stimuli.14 We created a novel method of local tissue cooling, using the phase change properties of ice particles in an ice slurry suspension, and showed that it can safely, selectively and effectively target lipid-rich tissue in a porcine model.15 Ice slurries can absorb high quantities of heat, due to ice’s large heat of fusion (334J/g). In the current study, a biocompatible ice slurry at moderately cold temperatures (around −5°C) and consisting of sterile ice particles suspended in normal saline and glycerol, was used to selectively cool a peripheral nerve. We had previously shown that such moderately cold temperatures can affect sensory function when delivered topically in humans,14 and can selectively target lipid-rich tissue in swine when injected as an ice slurry.15

In this study we aimed to determine if ice slurry can be used as a novel, injectable, drug-free and tissue-selective method of cryoneurolysis that can reduce pain. We hypothesized that injection of ice slurry around the rat sciatic nerve will change the nociceptive response from the baseline through neural selective cryoneurolysis. The primary outcome of this study was the magnitude of the nociceptive response. We quantitatively evaluated the effect of ice slurry treatment on myelin sheath and axon structural integrity, and on neurological functions mediated by the sciatic nerve. Finally, we sought associations between structural changes and functional losses at different times after injection.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250g, 7–8 weeks old) were purchased from the Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were housed under pathogen-free conditions in an animal facility at the Massachusetts General Hospital in accordance with animal care regulations. Sixty-two animals were used in total in this study. Massachusetts General Hospital IACUC approved the animal studies. All Experiments in animals in test and control groups were performed at similar times of the day (10 Am to 4 pm).

Animal cooling procedure and experimental design.

Ice slurry composed of normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) plus 10% glycerol by volume was made as described previously.15 Briefly, sterile normal saline with 10% glycerol solution was added into a sterile slush maker (Vollrath Frozen Beverage Dispenser; Vollrath Co, LLC, Sheboygan, WI) to produce the slush. This was then blended in a sterile blender (HGB150, Waring Commercial, Torrington, CT) to create an injectable slurry. Ice particle size was controlled by blending to produce slurry that was consistently injectable through the needle. Slurry temperature was measured with a thermocouple (Omega, Stamford, CT). Rats were injected with ice slurry (treatment group) or room temperature solution (control group) around the sciatic nerve. The room temperature control solution was made of the same composition (0.9% sodium chloride with 10% glycerol) as the liquid phase of the slurry only without ice particles. We used a 15-gauge hypodermic needle for the injections. Under brief anesthesia with inhalational isoflurane (1–3% with 1–1.5 liter/minute oxygen), using standard method of injection,16 the needle was introduced into the sciatic notch posteromedial to the greater trochanter of the femur pointed in an anteromedial direction. Once bone was contacted, the needle was withdrawn approximately 1mm, and 15mL of ice slurry at around −3.5°C to −5°C was injected around the sciatic nerve in animals in the Treatment group. This volume of injection was chosen based on preliminary studies of the temperature and duration of cooling needed for biologic effect. Age and weight matched control rats were injected with the same method and volume of room temperature control solution. Histological and functional changes were monitored at baseline and at various time points post-injection. For histologic and imaging data, nerve samples were collected from 3–4 rats per group on days 7, 14, 28, 56 and 112 post-injection. Total of 28 rats were used for imaging and histologic studies. Functional studies were done every 1–3 days post-injection. All functional studies were repeated in two independent experiments and for each experiment the control group contained n=8–10 rats and the treatment/test group contained n=8 rats. Total of 34 rats were used for functional studies.

Toe spread test.

Physiological toe spread reflex was assessed using a modified toe spread test to identify changes in muscle function after treatment with slurry.17 Each rat was lifted by the base of the tail with the legs hanging freely. The toe spread reflex was scored with the following rating system: normal toe spread reflex with all of the toes spreading out was given a score of 0; weak reflex with partial spreading of some toes got a score of 1; and lack of toe spread reflex received a score of 2.

Walking test.

Motor function was also assessed by walking behavior.18 In this scoring system normal walking function was scored as 0; normal dorsiflexion ability while walking with curled toes received a 1; moderate dorsiflexion ability with curled toes during walking was scored as a 2; and no dorsiflexion ability with curled toes during walking was scored as a 3.

Mechanical nocifensive test (Von Frey assay).

Rats were habituated by handling in the experiment room and were tested for 6–7 days before the start of experiment to avoid stress (training period). Rats were placed on an elevated plastic mesh floor and allowed to habituate for 30–40 minutes before testing was initiated. Paw Withdrawal Frequency (PWF), as a measure of sensitivity to punctate mechanical stimulation, was determined using calibrated von Frey hairs (VFH). Von Frey hairs were applied perpendicular to the lateral third plantar surface of the hind paw through the mesh. Each VFH (4g, 8g, 10g, and 15g) was applied 10 times, for 3s or until paw withdrawal, separated by a 3s interval. Testing started with the 4g force and continued with increasing forces. The number of paw withdrawals (range 0–10) in response to 10 trials was marked as PWF for each force, as previously described.19 For comparison between treatment and control groups, PWF values at each time point were normalized by dividing the value by that in the same animal at baseline, and results were shown as a percentage of the baseline value.

Thermal test.

The sensitivity of the plantar paw to noxious radiant heat was determined using Hargreaves Apparatus (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy).20 Animals were habituated and tested in the enclosure on the glass platform for about a week before the start of experiment to avoid stress. Animals were placed in the enclosure and allowed to habituate for 20–30 minutes before testing was initiated. Paw withdrawal latency (PWL) in response to heat stimulation was defined by the time between the beginning of the radiant heat and the withdrawal movement of the paw. A cut-off time of 20 seconds was set to avoid test-induced sensitization. A series of 3–4 withdrawal latencies were measured alternately on left and right hind paws. Tests on the same hind paw were separated by 3–4-minute intervals.

Light Microscopy.

Sciatic nerve samples were harvested from rats and fixed in 10% formalin. Subsequently, tissue was processed and embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5μm, deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Coherent anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS) Microscopy.

The CARS microscope was built over a customized confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000, Center Valley, PA). The illumination source consisted of a dual output femtosecond pulsed laser system (Spectra-Physics Insight DeepSee, Santa Clara, CA), where one output can be tuned from 680 to 1300nm, while the second is fixed at 1040nm. For all CARS experiments, tunable output was set to 803nm in order to probe the 2845cm−1 symmetric stretching vibrational mode of CH2, thereby generating an anti-Stokes signal at 654nm, detected by a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu H7422PA-50, Hamamatsu City, Japan). A 60× 1.20 NA water immersion objective (Olympus UPLSAPO 60XW, Center Valley, PA) was used as the objective lens for all CARS experiments. Images were 512 × 512 pixels in size, collected with a dwell time of 4μs per pixel using approximately 25mW of pump power and 25mW of Stokes power at the focus. Depth stacks were acquired from the surface of the nerve to 20μm within the tissue at 1-μm intervals, resulting in 21-frame image stacks. The volumetric image sets were projected to 2D images (as shown in fig. 2A), where the color corresponds to the depth within the stack: cyan features are most superficial, while red features are deeper within the tissue. A series of three images were acquired from each sample. The corrected correlation parameter (CCP) was used to assess myelin structure following the methodology described by Bégin et al.21 Briefly, each CARS image was subdivided into 16 adjacent domains (i.e. a 4×4 grid). Each domain is transformed by a 2D Fourier transform to assess the fiber orientation and integrity within each domain. These values, together with their mutual correlation across all 16 image domains, are combined to quantitatively describe the average fiber orientation and collinearity across the entire imaging field of view, characterized by the CCP metric.

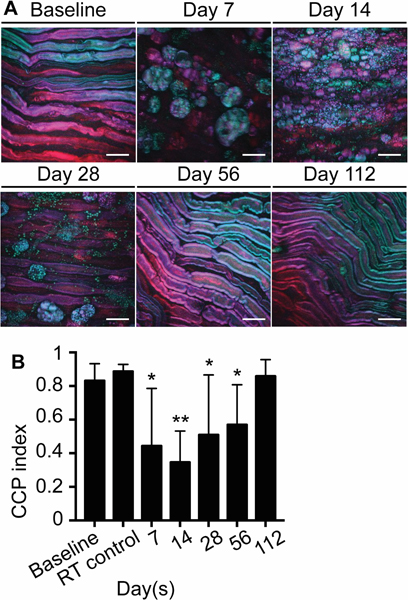

Fig. 2.

Ice slurry induces reversible disruption of myelin sheaths. (A) CARS microscope imaging shows loss of myelinated nerve fibers and presence of lipid droplets in macrophages, which recovers by day 112 post-treatment. (B) Graph shows corrected correlation parameter (CCP) index at day 7, 14, 28, 56, and 112 after injection of slurry and at day 7 after injection of control room temperature solution (RT control). Data are presented as mean with SD. n=9 images from 3 animals per group for days 7, 14, 28, and for RT control group. n=12 images from 4 animals per group for baseline, and for days 56 and 112; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001 compared to baseline by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; scale bars: 20 μm; RT, room temperature.

Immunofluorescence.

Sciatic nerve samples processed and embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 5μm, were deparaffinized in CitriSolv (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), rehydrated through graded alcohol washes, incubated in Cytomation Target Retrieval solution (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) at 98°C for 30 minutes for antigen retrieval, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline for 15 minutes, blocked with a solution of 10% goat serum, 3% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Tween-20 in Tris-buffered saline for 30 minutes, and treated overnight at 4°C with primary anti-rat antibodies (See Supplementary Digital Content 1 that describes antibodies). Sections were washed in 0.01M PBS and fluorescent secondary antibodies were applied for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were washed in 0.01M PO4- PBS, and VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was applied. An Olympus Fluoview FV1000 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) laser scanning confocal microscope with IX81 inverted microscope base was used, with 40X 0.80NA (UPLSAPO) objective lens for imaging. In order to determine the axon density, the number of NF200 positive axons was quantified in 10 random areas of 1000μm2 in each sample using ImageJ software. Research Randomizer software was used for randomization.22

Histomorphometry.

Sciatic nerve samples were fixed in a mixture of 2% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde solution at 4°C for 24 hours. Specimens were washed in sodium cacodylate buffer and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 hours. Samples were dehydrated in ethanol, washed with propylene oxide and embedded in epoxy resin. Semi-thin sections (0.5 μm thickness) of nerves were cut using a diamond blade microtome (Donsanto, Natick, Mass). Samples were stained with toluidine blue in preparation for light microscopy and scanned using a Hamamatsu NanoZoomer slide scanner (Meyer Instruments, Houston, Texas). Using ImageJ software, the number of myelinated nerve fibers were counted in 10 random areas of 1000μm2 in each sample. Research Randomizer software was used for randomization.22 For each of these fibers, fiber diameter and axon diameter were measured, and myelin thickness was derived from the difference between fiber diameter and axon diameter.

Statistics.

No statistical power calculation was conducted before the study. Our sample sizes selection was based on our previous unpublished experience with similar experimental protocols with this rat model and tests. There were no missing data. Rats were randomly assigned to test or control groups. The observer for the behavioral testing was not present for the administration of treatments. Motor weakness in slurry treated animals prevented full blinding of the behavioral observer. Investigators performing the CARS imaging were blinded to the treatment groups until image acquisition was completed. The initial assessment of the histologic data was performed by board-certified neuropathologist, blinded to the treatment groups. Statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Data were tested for normality using the D’Agostino & Pearson normality test. CCP outcome measures followed normal distribution, all other outcome measures did not show normal distribution. Degree of organization/disorganization in the myelin structure was quantified with CCP index in images associated with each animal as the unit of analysis. Ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used as the test of significance between groups for interval CCP index values, comparing each follow-up time point for each group to the baseline. Axon density was calculated in hpfs (high power fields) within an image as the unit of analysis. Myelin thickness was calculated for each nerve fiber as the unit of analysis. Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used for continuous data of immunofluorescence axon density and histomorphometry axon density, and for myelin thickness, to compare each follow-up time point for each group to the baseline. Toe spread score, walking score, and PWF were examined in each animal as the unit of analysis. Friedman’s test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to determine whether ordinal data of toe spread score and walking score, and integer PWF values were significantly different compared to baseline after ice slurry injection. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test was also performed to compare PWFs between treatment and control groups at each time point. All collected data were included in the study and none were excluded. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range.

Results

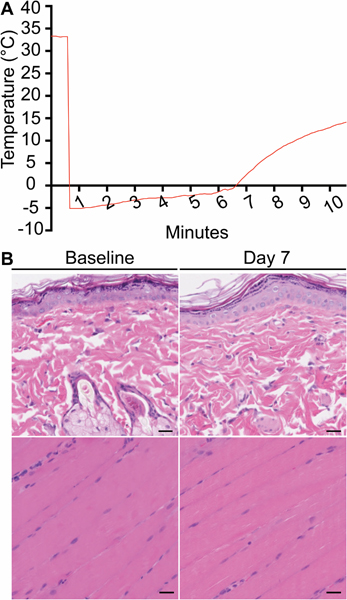

Ice slurry safely and selectively targets the sciatic nerve.

We monitored the temperature using a thermocouple in the same needle used to inject ice slurry into the compartment where containing the sciatic nerve. Injection of slurry induced a rapid decrease from the initial tissue temperature, near 33°C, to about −5°C; the sub-zero temperature lasted for a period of at least 6.5 minutes, during which the ice was melting (fig. 1A). Animals were checked immediately post-procedure and daily thereafter for skin necrosis or ulceration, neither of which were observed at any time. Injection of the ice slurry did not cause gross or microscopic damage to muscle and skin tissue (fig. 1B). In addition, on histologic analysis no fibrosis or evidence of scarring was observed in the skin, muscle or nerve tissue taken 7 days after injection of ice slurry.

Fig. 1.

Ice slurry is safe and selective for targeting the sciatic nerve. (A) Temperature recording shows rapid decrease in the compartment around the sciatic nerve followed by gradual warming. (B) Representative images of skin (upper panels), and muscle tissue (lower panels) at the injection site stained with H&E at 7 days post ice slurry injection; scale bar: 25 μm. There is no evidence of injury to skin or muscle.

Ice slurry induces reversible disruption of myelin sheaths.

The effect of ice slurry injection on myelin morphology and nerve architecture was examined using Coherent anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS) microscopy. CARS microscopy uses the endogenous contrast provided by vibrational modes of lipids.23,24 This technique can easily visualize the myelin sheath around axons, and also quantify the local tissue architecture. Using a two-dimensional Fourier transform (2D-FT) method to analyze CARS images, the average fiber orientation and directional anisotropy within the image can be extracted and used to calculate the correlation between orientation of neighboring nerve fibers. This metric, defined as the corrected correlation parameter (CCP) index, can be used to quantify the degree of organization/disorganization in the myelin structure.21 Injection of the ice slurry induced disruption of the myelin sheaths of sciatic nerve fibers, seen as swelling and disorganization on day 7 post-treatment (fig. 2). From the images acquired on days 7, 14, and 28 post-treatment, cells morphologically identified as macrophages appear to engulf the lipid droplets from disrupted myelin. Remyelination and reorganization of the nerve structure are apparent between days 14 and 28, and by day 112 post-treatment there was complete recovery of the nerve organization and myelination (fig. 2A). None of these changes were observed when room temperature solution was injected in control rats (fig 2B and See Supplemental Digital Content 2, panel A, that shows myelin structure at baseline and 7 days post-injection of room temperature control solution), indicating that cooling per se was responsible for the changes. The CCP index was used to quantify the degree of organization in the myelin structure as previously reported by Bégin et al., where a CCP value of 0 indicates complete disorganization, while a value of 1 indicates complete organization of the myelin.21 The CCP index decreased significantly from 0.83 ± 0.10 at baseline to the lowest level of 0.34 ± 0.19 (a 60% reduction P = 0.0001) at day 14, and gradually returned to normal level of 0.86 ± 0.10 at day 112 post-treatment (fig. 2B).

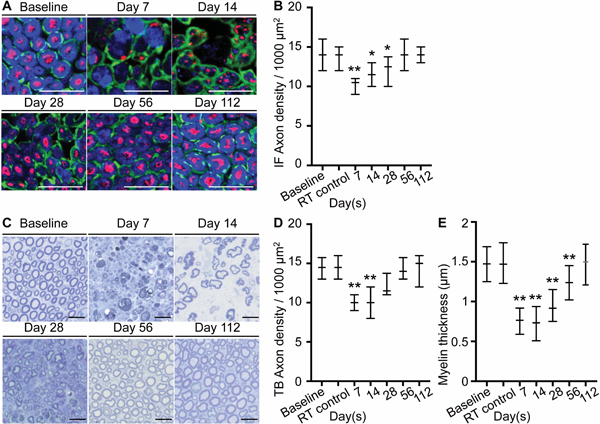

Ice slurry induces reversible decrease in axon density and myelin thickness.

To examine the effect of slurry on nerve structure, axon density, Schwann cells and myelin sheaths, we used immunofluorescence (IF) of nerve samples collected at baseline and at various time points post-slurry injection (days 7, 14, 28, 56 and 112), and stained with antibodies to specific proteins. Samples for immunofluorescence staining were collected from the same nerve tissues used for CARS imaging. Staining of the axons with NF200 antibody, Schwann cells with S100 antibody, and myelin sheaths with Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) antibody showed that there was, respectively, decreased axon density, disruption of normal nerve architecture and loss of the myelin sheath as early as day 7 post-treatment (fig. 3A). The axon density decreased from median [interquartile range]: 14 [12 to 16] axons/1000μm2 at baseline to 10.5 [9 to 11] axons/1000μm2 at day 7 (a 25% reduction P < 0.0001) and had fully recovered by day 112 (fig. 3B). Similar to CARS imaging, immunofluorescence of myelin sheaths showed reversible recovery by day 112 (fig. 3A). Histomorphometric analysis was performed on nerve thin sections stained with toluidine blue to quantify the changes in myelinated nerve fibers post-treatment. Degenerating axons were noted as early as day 7 post-treatment (fig. 3C). There was marked loss of myelin around the axons, and demyelinated naked large axons on day 14 post-treatment. Quantification of axon density in these sections showed that slurry injection led to decreased axon density from 14.5 [13 to 15.75] axons/1000μm2 at baseline to 10 [9 to 11] axons/1000μm2 at day 7 (a 31% loss P < 0.0001) with full recovery by day 112 (fig. 3D). Moreover, histomorphometic analysis for the fiber and axonal diameters, from which the myelin thickness was calculated, showed significant decrease in myelin thickness from a baseline value of 1.47 [1.25 to 1.69 ]μm to 0.76 [0.59 to 0.92 ]μm at day 7 (a 48% reduction) with gradual and full recovery to 1.50 [1.21 to 1.72]μm at day 112 (fig. 3E). Notably, the thinning of the myelin sheath was proportionally greater (48% vs 25%) and its restoration to pre-treatment value slower (achieved at 112 days vs 56 days) than that of the density of nerve axons. Control animals injected with room temperature slurry solution did not show any abnormalities on immunofluorescence imaging or with toluidine blue staining (fig 3B, D, E and See Supplemental Digital Content 2, panels B and C).

Fig. 3.

Ice slurry induces reversible decrease in axon density and myelin thickness. (A) Immunofluorescence staining shows preservation of S100 positive Schwann cells (green) and loss of MBP positive myelin (blue) and NF200 positive axons (red). (B) Graph shows quantification of axon density as shown in A, expressed as axons/1000μm2 at day 7, 14, 28,56, and 112 after injection of slurry and at day 7 after injection of control room temperature solution (RT control). n=20 hpf from 2 animals per group per time point. (C) Representative image of nerve sections stained with toluidine blue. (D) Graph shows quantification of axon density as shown in C, expressed as axons/1000μm2. n=20 hpf from 2 animals per group per time point. (E) Graph shows myelin thickness of axons stained with toluidine blue. n=292 nerve fibers in 20 hpf from 2 animals at baseline, n=285 nerve fibers in 20 hpf from 2 animals in RT control group, n=203 nerve fibers in 20 hpf from 2 animals at day 7, n=214 nerve fibers in 20 hpf from 2 animals at day 14, n=245 nerve fibers in 20 hpf from 2 animals at day 28, n=287 nerve fibers in 20 hpf from 2 animals at day 56, n=287 nerve fibers in 20 hpf from 2 animals at day 112; Data are presented as median with interquartile range. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.001 compared to baseline by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test; scale bars: 20 μm; RT, room temperature; IF, immunofluorescence.

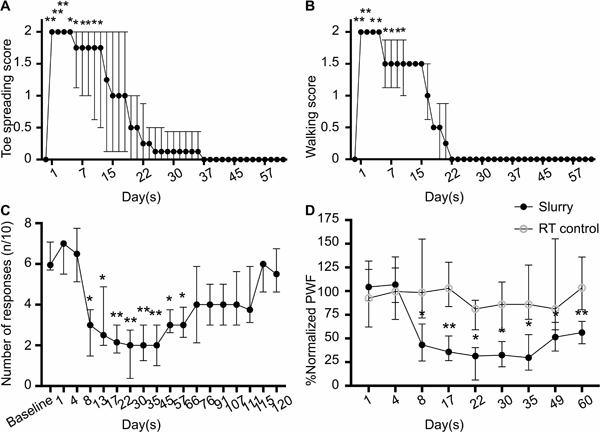

Ice slurry injection leads to long-lasting, reversible loss of nerve-mediated functions.

To evaluate the effect of ice slurry injection on motor function, toe spread and walking assays were conducted. After ice slurry injection, the toe spread reflex was lost by day 1, and later returned to nearly normal levels by day 27 (fig. 4A). Deficits of walking function also were maximum by day 1, with full recovery by day 22 (fig. 4B). Statistical significance of differences from baseline disappeared at about day 10–14 post-treatment. No changes in walking behavior were observed in rats injected with room temperature control solution (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Ice slurry injection leads to long lasting and reversible functional loss. (A) Toe spread and (B) walking scores of hind limbs injected with slurry. Data are presented as median with interquartile range. n=8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 compared to the baseline by Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (C) The graph shows Paw Withdrawal Frequency (PWF) in response to plantar stimulation with 15g VFH. n=8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 compared to the baseline by Friedman test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (D) Comparison of the effects of slurry and room temperature control solution on mechanical pain with 15g VFH in treated hind limbs. Paw withdrawal frequency values at each time point are normalized by dividing it by the value in the same animal at baseline and results are shown as percentage of the baseline value. n=8 per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 compared to the room temperature solution control group by two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test; RT, room temperature.

To evaluate the effects of ice slurry injection on sensory nociceptive function, von Frey hair (VFH) testing for mechanical pain and Hargreaves testing for thermal pain were performed. Eight days after injection of ice slurry there was a significant decrease in mechanical pain response to a 15g VFH applied to the lateral plantar aspect of the ipsilateral hind paw, measured by Paw Withdrawal Frequency (P = 0.001 compared to baseline). This ice slurry-induced mechanical hyposensitivity lasted through day 60 post-treatment with peak reduction at day 22 of 68 [60 to 94] %, compared to baseline (fig. 4C). Half-recovery occurred at 9–10 weeks. The same general pattern of reduction in mechano-sensitivity was observed for VFH testing with lower force (10g) (See Supplemental Digital Content 3, panel A). Rats in the control group receiving room temperature solution injection did not show any significant changes from baseline in mechanical pain sensation when tested with any VFH force (See Supplemental Digital Content 3, panel B). There was a significant difference in mechanical pain sensation between the treatment and control (RT) groups starting from day 8 and continuing up to day 60 (fig. 4D).

Thermosensitivity testing of the plantar hind paw to noxious radiant heat did not show significant changes, unlike those to mechanical stimulation. No thermosensitivity changes were present in hind limbs injected with room temperature control solution at all time points post-treatment (See Supplemental Digital Content 4). All functional studies were repeated in two independent groups of (n=8) rats.

Discussion

In summary, this study demonstrated the feasibility of safely using injectable ice slurry for tissue-selective cryoneurolysis of a peripheral nerve in rats, to reduce mechanical nociception. A single injection of −5°C slurry around the sciatic nerve reversibly disrupted the myelin structure for at least 8 weeks, decreased the axon density for 2–4 weeks, and inhibited motor and punctate nociceptive (sharp pain) functions for 3–4 and 8 weeks, respectively. One limitation of our study is that blinding was not used for the functional studies (toe spread test, walking test, mechanical nocifensive test, and thermal test). Valid experimental blinding of the observer for the behavioral testing was not possible due to the immediate physical appearance of the treated hind paw, as the slurry treated animals were unable to stand or walk for several weeks using that hind paw. The control treated rats appeared physically unaffected and had normal stance and locomotor function. The association between structural changes and functional losses are noteworthy. Motor function deficits (both toe spreading and walking) were maximum at the first day of testing (day 1 post-injection) and had recovered by day 27, whereas a significant reduction in mechanical nociception was not detected until day 8 post-treatment and lasted up to day 56 (fig. 4C). The delayed reduction of nociceptive response will be taken into consideration when designing pilot human studies to test if this therapy is safe and effective. Depending on the outcome of the human studies, the timing of the treatment can be adjusted to optimize postsurgical pain reduction. As noted above, the loss of axon density was maximum at 7 days (25–31%) and lasted for at least 28 days, whereas loss of myelin structure and thickness was greater (50–60%) at 7 days and lasted for at least 56 days. The relatively rapid recovery time of motor functions more closely paralleled that of axon density, whilst the slower recovery of mechanical nociception followed that of remyelination. Thermal hyperalgesia, traditionally considered to be mediated by unmyelinated C-fibers, appears to be unaffected by ice slurry injection.25 Further studies, measuring structural changes during the first week after injection and examining unmyelinated nerve fibers, are necessary to refine these structure-function relationships.

The broad mechanisms of cryoneurolysis by ice slurry injection appear to be similar to those described in previous reports of cryoneurolysis, with histological changes consistent with Wallerian degeneration. However, an important novel observation from this study is that cryoneurolysis of the rat sciatic nerve can occur at the temperature of −5°C, making this a selective treatment that targets nerve without damage to surrounding tissue. A second novel observation is that selective cryoneurolysis can be achieved via an injectable biocompatible slurry in rats. Being a fluid suspension, the slurry can infiltrate by flowing around the target nerve, leading to uniform cooling and consequent structural changes in the nerve. Although there is selectivity of interaction between injected ice slurry and a target nerve, the use of electrical or ultrasound image guidance will be warranted to reduce the risk of neural trauma from the needle.

The use of cryoneurolysis to block peripheral nerves has been known for many years. More recently, a focused cold therapy (FCT) utilizing 27G needles capable of delivering −60°C for 1 minute was introduced as a transcutaneous cryoneurolysis method.12 The demyelination and axonal degeneration we report here after injection of ice slurry are similar to previous reports of cryoneurolysis treatments.26 Using the same sciatic nerve rat model in a preclinical study with the FCT device, cooling the nerve by direct contact with a probe at −55°C for 1 minute, it was shown that after a single treatment the motor function was inhibited for up to 30 days,26 similar to what we observed after injection of ice slurry. However, the use of such extremely low temperatures and the requirement for direct nerve contact, have limited the clinical use of such cryoneurolysis devices. These limitations are overcome using an injectable, biocompatible ice slurry. Melting of ice can extract large amounts of tissue heat, due to the large heat of fusion (334J/g), much more efficiently than a cold aqueous solution. Furthermore, by controlling ice particle size, the slurry may be injected through a small hypodermic needle or cannula.

In summary, the injectable ice slurry has multiple advantages over the currently used methods of cryoneurolysis for analgesia. These include: 1) the ability to inject the slurry using a hypodermic needle and syringe; 2) infiltration of the slurry into tissue increases the likelihood of cooling the target nerve; 3) ice slurry is nerve-selective because of its temperature, and while cold enough to cause cryoneurolysis, it is not destructive to other tissue with the exception of adipose tissue.15 For these reasons, the use of injectable ice slurry to target peripheral nerves has the potential to offer a long-lasting, non-addictive and drug-free treatment for blocking conduction and thus reducing postoperative pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This work was supported by a research contract from the United States Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Fund (FA9550–16-1–0479). This work was partially supported by a P41 grant from the NIBIB (award number 2P41EB015871–31) to the Laser Biomedical Research Center. ASR received support from Children Tumor Foundation (paid travel accommodation; paid MGH grant) and from American Association of Neuropathologists (paid travel accommodation).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

R.R.A and L.G. are inventors in patents related to this work, which are owned by the Massachusetts General Hospital. R.R.A, L.G., S.M.T, and Y.W. hold equity in a company recently founded to develop and commercialize this technology. The company had no involvement in this study, which was not supported by any commercial entity. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Prior presentation: Part of this work was presented as oral presentation at Military Health System Research Symposium on August 29, 2017 at Kissimmee Florida, and at Society of Investigative Dermatology conferences on April 27, 2017 in Portland Oregon

References

- 1.Trescot AM, Brown MN, Karl HW. Infrapatellar saphenous neuralgia - diagnosis and treatment. Pain Physician 2013;16(3):E315–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poobalan AS, Bruce J, Smith WC, King PM, Krukowski ZH, Chambers WA. A review of chronic pain after inguinal herniorrhaphy. Clin J Pain 2003;19(1):48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367(9522):1618–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benedetti F, Vighetti S, Ricco C, Amanzio M, Bergamasco L, Casadio C, Cianci R, Giobbe R, Oliaro A, Bergamasco B, Maggi G. Neurophysiologic assessment of nerve impairment in posterolateral and muscle-sparing thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;115(4):841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikkelsen T, Werner MU, Lassen B, Kehlet H. Pain and sensory dysfunction 6 to 12 months after inguinal herniotomy. Anesth Analg 2004;99(1):146–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, Buenaventura R, Adlaka R, Sehgal N, Glaser SE, Vallejo R. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbasi J As Opioid Epidemic Rages, Complementary Health Approaches to Pain Gain Traction. JAMA 2016;316(22):2343–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dasa V, Lensing G, Parsons M, Harris J, Volaufova J, Bliss R. Percutaneous freezing of sensory nerves prior to total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2016;23(3):523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trescot AM. Cryoanalgesia in interventional pain management. Pain Physician 2003;6(3):345–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore W, Kolnick D, Tan J, Yu HS. CT guided percutaneous cryoneurolysis for post thoracotomy pain syndrome: early experience and effectiveness. Acad Radiol 2010;17(5):603–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackmann T, Von During M, Teske W, Ackermann O, Muller P, Von Schulze Pellengahr C. Anatomy of the infrapatellar branch in relation to skin incisions and as the basis to treat neuropathic pain by cryodenervation. Pain Physician 2014;17(3):E339–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilfeld BM, Preciado J, Trescot AM. Novel cryoneurolysis device for the treatment of sensory and motor peripheral nerves. Expert Rev Med Devices 2016;13(8):713–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsland AR, Ramamurthy S, Barnes J. Cryogenic damage to peripheral nerves and blood vessels in the rat. Br J Anaesth 1983;55(6):555–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garibyan L, Cornelissen L, Sipprell W, Pruessner J, Elmariah S, Luo T, Lerner EA, Jung Y, Evans C, Zurakowski D, Berde CB, Anderson RR. Transient Alterations of Cutaneous Sensory Nerve Function by Noninvasive Cryolipolysis. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135(11):2623–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garibyan L, Moradi Tuchayi S, Javorsky E, Farinelli WA, Wang Y, Purschke M, Tam J, Ni P, Lian CG, Anderson RR. Subcutaneous Fat Reduction with Injected Ice Slurry. Plast Reconstr Surg. Accepted for publication 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santamaria CM, Zhan C, McAlvin JB, Zurakowski D, Kohane DS. Tetrodotoxin, Epinephrine, and Chemical Permeation Enhancer Combinations in Peripheral Nerve Blockade. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(6):1804–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varejão A, Melo-Pinto P, Meek M, Filipe V, Bulas-Cruz J. Methods for the experimental functional assessment of rat sciatic nerve regeneration. Neurol Res 2004; 26(2):186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brummett CM, Norat MA, Palmisano JM, Lydic R. Perineural administration of dexmedetomidine in combination with bupivacaine enhances sensory and motor blockade in sciatic nerve block without inducing neurotoxicity in rat. Anesthesiology 2008; 109(3):502–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khodorova A, Nicol GD, Strichartz G. The p75NTR signaling cascade mediates mechanical hyperalgesia induced by nerve growth factor injected into the rat hind paw. Neuroscience 2013;254:312–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain 1988; 32(1): 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bégin S, Bélanger E, Laffray S, Aubé B, Chamma E, Bélisle J, Lacroix S, De Koninck Y, Côté D. Local assessment of myelin health in a multiple sclerosis mouse model using a 2D Fourier transform approach. Biomed Opt Express 2013;4(10):2003–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urbaniak GC, Plous S. 2013. Research Randomizer (Version 4.0) [Computer software]. Retrieved on March 26, 2019, from http://www.randomizer.org/.

- 23.Evans CL, Xie XS. Coherent anti-stokes Raman scattering microscopy: chemical imaging for biology and medicine. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2008;1:883–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Belanger E, Begin S, Laffray S, De Koninck Y, Vallee R, Cote D. Quantitative myelin imaging with coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy: alleviating the excitation polarization dependence with circularly polarized laser beams. Opt Express 2009;17(21):18419–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaMotte RH, Thalhammer JG, Torebjörk HE, Robinson CJ. Peripheral neural mechanisms of cutaneous hyperalgesia following mild injury by heat. J Neurosci 1982;2(6):765–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu M, Stevenson FF. Wallerian degeneration and recovery of motor nerves after multiple focused cold therapies. Muscle Nerve 2015;51(2):268–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.