Abstract

Mnx - ZnO(1-x) nanopowders were successfully synthesised through a simple sol-gel method. The samples were annealed at 300 °C to enhance their crystallinity. The lattice structure, morphology and optical properties of the prepared powdered samples were extensively studied using different characterization techniques, confirming the formation of Mnx - ZnO(1-x). The inclusion of Mn did not cause any change to the wurtzite structure of ZnO; however slight peak shifting and increase in lattice parameters were indicated. The normal absorption spectra pointed to a cut-off edge extending beyond the UV region and a Burstein- Moss type band gap broadening induced by the Mn doping. ZnO showed excellent photodegradation activity against methylene blue (MB) upon UV irradiation. Intensifying the dopant concentration resulted in further diminution of photoactivity against MB. This reduction of photocatalytic activity of ZnO upon doping can be drawn to be due to the presence of Mn in the ZnO lattice, which acted as recombination sites for the photogenerated charge carriers. The results demonstrated that doping ZnO with Mn can be used to suppress the oxidative stress induced by reduced oxygen species (ROS) through generation of recombination centres. The suppression of toxic ROS generation implies possible application in fabrics and ointments for UV shielding applications.

Keywords: Materials science, Nanotechnology, Photocatalysis, Semiconductor metal oxides, Recombination centres, Electron/hole pair

Materials science; Nanotechnology; Photocatalysis; Semiconductor metal oxides; Recombination centres; Electron/hole pair

1. Introduction

Efforts towards developing UV radiation shielding agents are currently recognized. Photocatalysts can be used to retard the effect of UV radiation exposure through UV absorption and transforming the absorbed UV photons to less harmful forms of energy. Different semiconductor metal oxides (SMOs) have been investigated for possible application in UV radiation shielding [1, 2, 3, 4]. However; they are known to possess very high photocatalytic activities, which can be an impediment for these SMOs to be used in their bare form. Elevated photon absorption and utilization of the photogenerated electron/hole pairs during SMO irradiation predicts a high rate of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation which can possibly degrade the matrix, (fabrics, surfaces) as well as pose toxic health effects associated with human exposure. Excessive ROS are known to cause oxidative stress, leading to disruption of a variety of cellular components and biomolecules. If not well regulated, disproportionate ROS can induce DNA defacement or oxidative degradation of lipids, proteins as well as enzymes [5, 6]. It is imperative to add a ROS depressant to suppress the photocatalytic activity, without implicating the UV absorbance property, for superior UV shielding capability and to reduce the undesired skin and cell dysfunction and disruptions.

Zinc oxide (ZnO) has been explored for different applications ranging from optoelectronic devices, piezoelectric devices, gas sensing, energy harnessing and storage as well as environmental remediation. With a direct band gap of 3.3 eV and a high exciton binding energy of 60 MeV, ZnO has a good photoresponse for UV A, UV B and UV C absorbance, a plausible property for use in photon-trapping applications, [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. Besides, ZnO is a less toxic and also cost-efficient material due to its abundance, making it advantageous over other metal oxides. ZnO, as one of the inorganic UV-absorbers has been used to formulate UV shielding materials such as sunscreens. Surface modifications such as silica coating [13], impurity doping [14, 15], polymer stabilization [16, 17], capping agents [18] and metal oxides hetero-composites [1, 4, 19] have been implemented to tune the photo response properties of ZnO for possible application in reducing the effects of UV absorption.

Transitional metals (TMs) impurity dopants introduces some crystallographic defects which can serve as electron sinks to trap the generated electron charges thus resulting in enhanced photocatalytic activity [20, 21, 22, 23]. In contrast, some TMs have the aptitude to reduce the photocatalytic activity by persuading the recombination of the photoinduced e−/h+ pair [2, 15]. According to Tsuzuki [24], contradictory results may be attributed to location of dopants as well influence from the fabrication method. Recently, Mn has been incorporated on ZnO to tailor its physiochemical properties including thermal [25], magnetic [26, 27], optical [28, 29] and piezoelectric properties [30]. However, limited progress has been made on deliberate addition of Mn ions to ZnO to suppress its photocatalytic activity for safe UV shielding applications.

The main purpose of this paper is to investigate the effect of Mn doping on the physiochemical (structural, morphological and optical) properties of ZnO. Absorption profiles and optical band gap values were calculated in order to confirm the cutoff energy with the purpose of evaluating the UV shielding capability of Mn–ZnO. The production and utilization of the possibly hazardous ROS was assessed through evaluation of photocatalytic activity against methylene blue.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Zinc acetate dihydrate [Zn(CH3COO)2.2H2O], Manganese acetate [Mn(CH3COO)2], sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and distilled water were used for this work. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma Aldrich and were of high analytical grade. No further purification was done before use.

2.2. Preparation of Mnx- ZnO (1-x)

Manganese doped ZnO, [Mnx- ZnO(1-x), x = 0, 2, 6 at.%] nanopowders were prepared using a simple sol-gel method. 0.1 M Zn(CH3COO)2.2H2O and respective Mn(CH3COO)2 solutions were prepared and mixed together. The mixture was heated at 90 °C for 2 h followed by cooling at room temperature. 0.2 M NaOH solution was prepared and added drop wisely to the aqueous Zn(CH3COO)2– Mn(CH3COO)2 while maintaining constant stirring at room temperature. A white precipitate was formed during the addition of NaOH. The mixture was thoroughly stirred magnetically at 65 °C for 2 h after which the precipitate was filtered, dried overnight at 120 °C and finally annealed at 300 °C for several hours.

2.3. Characterization

The surface morphology, crystallographic structure and optical characterization of Mnx- ZnO(1-x), were studied. Continuous PSD fast X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns in coupled two theta angles of 20–80⁰ were recorded using a Bruker Advance D8 diffractometer equipped with a monochromatic CuKα radiation of wavelength (λ) 1.5418 Å. 40kV and 40mA of accelerating voltage and current, respectively were used at a scanning rate of 1.5⁰/min. The morphology of the pristine and Mn–ZnO was observed using a JEOL 1400 transmission electron microscope (TEM). Raman measurements were acquired using a Horiba Labram HR revolution Raman spectrophotometer using a charge coupled detector (CCD). The absorbance measurements of the powdered samples were measured by dispersing 5 mg of the powder in distilled water followed by ultrasonic stirring, then taking the absorbance using a Perkin Elmer Lambda 750 UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer.

2.4. Photocatalytic assessments

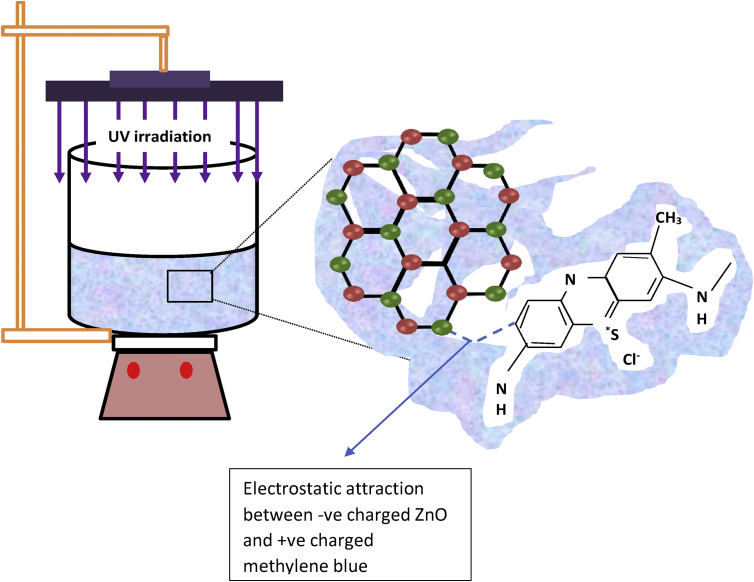

The photocatalytic performance of the samples was investigated with UV light irradiation as depicted by Figure 1. Raytech ultraviolet spectral lamps of LW-365 nm were used as the UV light source. 0.004 g/L of a cationic dye, methylene blue (MB) was used and its degradation was monitored at its maximum absorption peak at a wavelength of ~665 nm. 80 mL of MB solution was irradiated in presence of the 0.075 mg nanopowders. The distance between the UV lamps and the surface of the MB solution was 15 cm. First, the mixture was magnetically stirred in the dark for 60 min to establish the adsorption-desorption equilibrium. Upon irradiation, 2 mL of the MB solution was drawn, filtered through a polyether sulfone syringe nanofilter and its absorbance measured after every 30 min intervals. The total time of irradiation was 210 min. All samples were irradiated under same conditions.

Figure 1.

Schematic photocatalytic experiment setup. The enlarged shows the electrostatic interaction of the negatively charged ZnO and positively charged MB.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structural properties

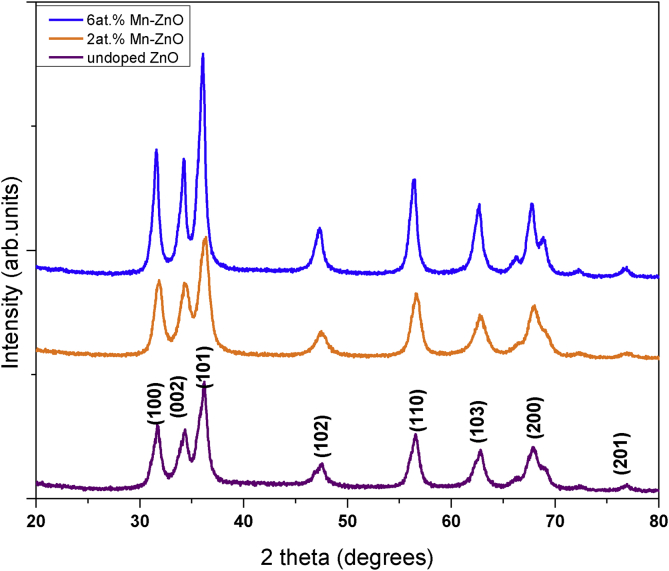

The XRD analysis technique was used to investigate the effect of Mn2+ doping on the crystallite phase, lattice and grain orientation of ZnO. Figure 2 shows the XRD patterns of Mnx ZnO(1-x) samples at different Mn content (x = 0, 2 and 6 at. %), which were post-annealed at 300 °C. The purpose of annealing was to enhance crystallinity of the samples [31]. The visible peaks of (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112) and (201) crystallographic planes were indexed to hexagonal wurtzite ZnO structure across all samples, and found to match that of COD 2013 database ID COD 9004180. No secondary phases from Mn phase segregation or signature impurities peaks were observed, indicating successful substitution of Mn2+ ions into Zn sites without altering the hexagonal wurtzite ZnO structure. Upon introduction of Mn, there was slight peak shift to lower diffraction angles which was attributed to strain in the samples due to doping. An increase of the Mn dopant influenced the broadening of the diffraction peaks thus a reduction in the crystallite size which was confirmed from calculations.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of the Mnx- ZnO (1-x) (x = 0, 2 and 6 at. %) samples.

For Scherrer (Eq. (1)), the most well pronounced peak in all samples, the (101) was used for crystallite size (D) calculations [32]:

| (1) |

The D values were denoted as DD-S and were recorded in Table 1. For comparison, the crystallite size was also calculated using the William-Hall (W-H) method. According to this model the crystallite size (D) and the micro-strain (ε) are related to the Bragg's parameters through;

| (2) |

Table 1.

Calculated crystallite sizes using Debye Scherrer and Williamson-Hall model.

| Mn dopant at.% | DD-S (nm) | DW-H (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12.3 | 11.3 |

| 2 | 11.2 | 10.9 |

| 6 | 10.6 | 9.3 |

For both Eqs. (1) and (2): λ is the X-ray wavelength (1.5418 Å for Cu Kα radiation), β is the observed angular width at half maximum intensity of the peak (FWHM) and θ is the Bragg diffraction angle in radians.

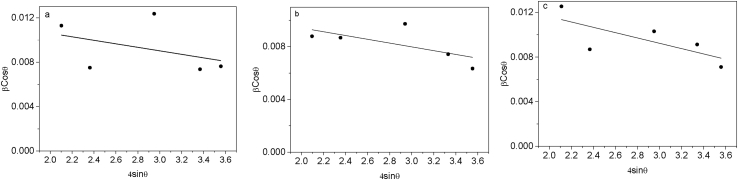

A plot of against (Figure 3) was used to calculate D from the vertical intercept and ε from the slope. Eq. (2) is usually referred to as the uniform deformation model owing to the assumption that the microstrain is equal in all crystallographic directions [33] and it differs from the lattice strain (ϵzz).

Figure 3.

Williamson-Hall plots for undoped ZnO (a), 2 at.% Mn doped ZnO (b) and 6 at.% Mn doped ZnO (c).

The values of D from this method were denoted as DW-H and the obtained values (Table 1) were found to correlate well with those calculated from Scherer method (DD-S). The reduction in crystallite size upon Mn2+ doping has been reported in literature and attributed to the generation of a retarding force on the grain boundaries that exceeds the driving force for grain growth of Zn, thus impeding the movement of the grain boundary and resulting in moderate reduction of the crystallite size as the dopant concentration is increased [25, 30].

In addition, the evolution of respective structural parameters with Mn2+ dopant effect was determined. The lattice parameters (a=b and c), the lattice constant (c/a), the dislocation density (δ), the lattice strain (ϵzz) as well as the Zn–O bond length (L) were calculated based on respective models [34]. The obtained results are presented in Table 2 and compared to values of the bulk (JCPDS 36–1451). For a hexagonal structure the lattice parameters relate to the miller indices, (hkl) and the interplanar spacing d though Eq. (3),

| (3) |

Table 2.

Calculated important lattice parameters and constants from XRD data analysis.

| Mn dopant (at.%) | Lattice Parameter (Å) |

Lattice constant c/a | Dislocation density (1/D2)∗1020 m−2 | Bond length (L, (Å) | Strain εzz (%) × 10−2 | Microstrain ε x 10−3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a = b | c | ||||||

| 0 | 3.24938 | 5.20380 | 1.60147 | 0.1632 | 1.9773 | -5.34 | 1.6 |

| 2 | 3.24943 | 5.20540 | 1.60194 | 0.1644 | 1.9775 | -2.30 | 1.4 |

| 6 | 3.24948 | 5.20700 | 1.60242 | 0.1619 | 1.9777 | 7.68 | 2.4 |

| Bulk ZnO | 3.2498 | 5.2066 | 1.6021 | - | 1.9778 | 0 | |

A constant trend was established between the lattice parameters and the increasing Mn dopant concentration. This is due to a slightly higher Mn2+ ionic radius of 0.80 Å compared to 0.74 Å for Zn2+, thus introducing Mn2+ to substitute Zn2+ results to stretching or expansion of the ZnO lattice in order to accommodate the Mn2+ ions thus inducing some strain on the unit cell, which was calculated using Eq. (4) [35] as;

| (4) |

The bond length was calculated from Eq. (5) [35].

| (5) |

where u = (a2/3c2 + ¼)

Similar correlation of lattice parameters with Mn content doping has been reported in literature [36, 37, 38].

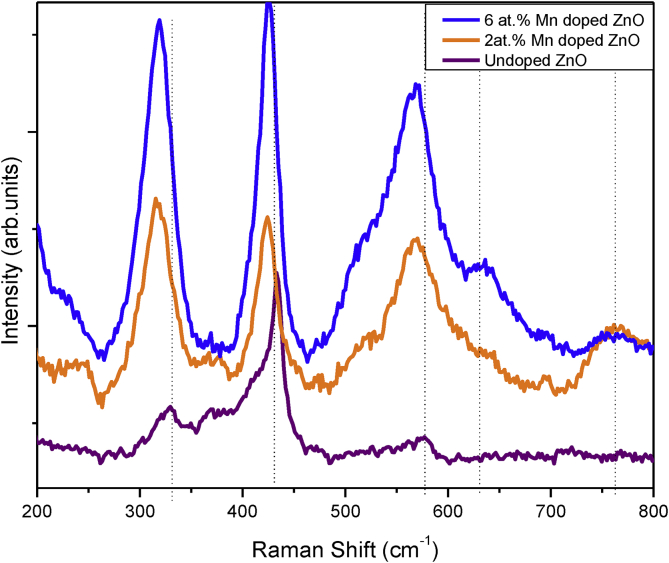

3.2. Raman analysis

Raman analysis at room temperature was employed to assist in detection of lattice defects induced by the presence of Mn dopant. The acquired spectra demonstrating pronounced spectroscopic peaks within the 200- 800 cm−1 range are presented in Figure 4. As an agreement to the XRD data, a wurtzite ZnO characteristic Raman peak was observed at 436 cm−1 for the pristine ZnO. This peak is ascribed as the E2H high phonon mode [25, 39]. An additional band, the 3E2L was observed at 330 cm−1 also for the pristine ZnO. Both the E2H and 3E2L peaks were slightly shifted towards lower frequencies for the Mn-doped ZnO. Vladut et al (2018) [25] and Das et al (2015) [40] also reported some peak shifting when doping ZnO with Mn ions, which they said was an indication of tensile stress induced in the crystal. Ahmed and co-authors [26], further highlighted that impregnating transition metals in the ZnO lattice leads to microscopic topological and structural disorders in the periodic Zn atomic sub lattice and breaks translational symmetry. A Raman peak at around 570 cm−1 was also recorded for the undoped ZnO, which appeared diminished. Similar to other mentioned peaks, its intensity increases upon increasing Mn dopant on Mn2+ doped ZnO. Additional modes (AMs) are depicted on Mn doped ZnO spectra around 630 and 760 cm-1. These peaks denote that Mn ions are present within the ZnO matrix.

Figure 4.

Room temperature Raman spectra of pristine and Mn-doped ZnO.

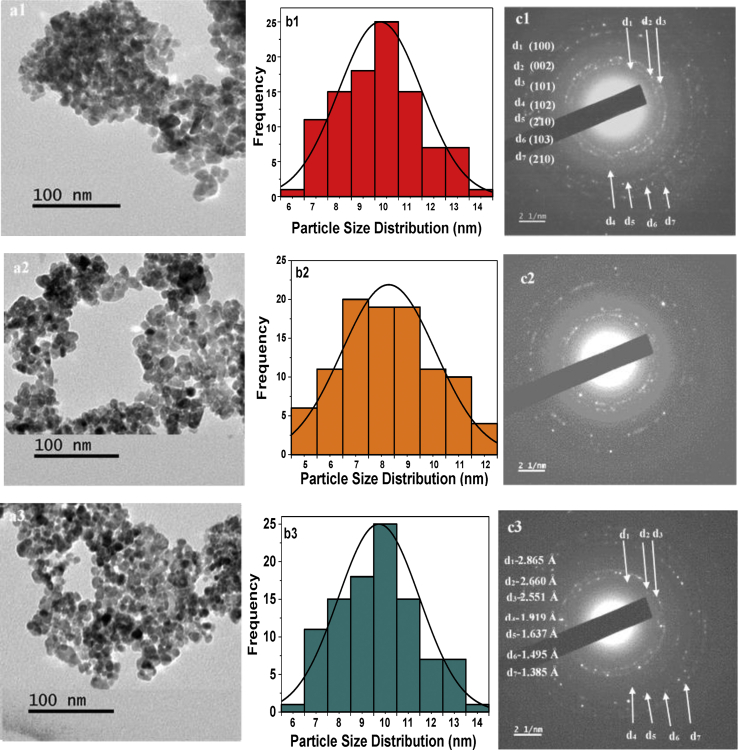

3.3. Surface morphology

The effect of Mn ions on the morphology of ZnO was evaluated through TEM imaging. The formation of spherical type of nano clustering was indicated. The grain sizes of Mnx- ZnO(1-x) samples were estimated from TEM measurements and presented as a histogram as depicted by Figure 5. The grain size decreased with Mn doping and the decreasing trend with increasing Mn content correlate well with crystallite sizes calculated from XRD analysis. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patters are given in Figure 5c. The polycrystalline nature of the samples was pointed out by the numerous concentric bright rings. The d-spacing values calculated from the SAED patterns were all matched to the peaks obtained from XRD confirming formation of pure phase of wurtzite ZnO.

Figure 5.

1st column:TEM images of undoped ZnO (a1), 2at.% Mn doped ZnO (a2) and 6 at.% Mn doped ZnO (a3); 2nd column: Histograms showing particle size distribution (PSD) measured from respective TEM data of undoped ZnO (b1), 2at.% Mn doped ZnO (b2) and 6 at.% Mn doped ZnO (b3); 3rd column: SAED patterns of undoped ZnO (c1), 2at.% Mn doped ZnO (c2) and 6 at.% Mn doped ZnO (c3).

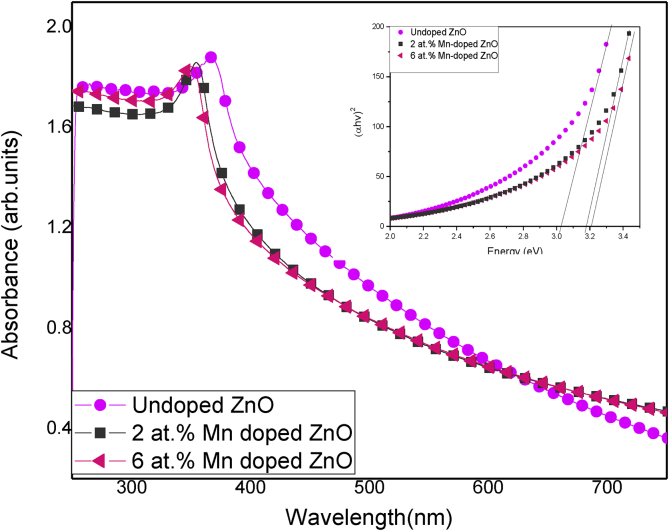

3.4. Assessment of UV blocking properties of ZnO

The recorded UV-Vis absorbance of the Mnx- ZnO(1-x) samples is given in Figure 6. It is clear that all the samples are highly absorbing in the UV region with transparencies tending into the visible region. An excitation peak was observed at around 370 nm for pristine ZnO and around 355 nm for the doped samples. A blue shift in the absorption edge was noted upon Mn doping. The observed blue shift ascribed to inclusion of Mn ions into the ZnO lattice has previously been reported [27, 29]. Quantum confinement effect is the cause of this shift. As the crystallite size decreases due to Mn doping, there is a further shift in the absorption band. Kumar et al (2012) [28], outlines that a blue shift indicates the orbital hybridization between the dopant and the host lattice. Several factors which include surface effects, increase in the carrier concentration, change in the crystallite size, oxygen vacancies and scattering at grain boundaries can result to blue shifting in the absorption band edge.

Figure 6.

Absorbance spectra and Tauc plot band gap extrapolations (insert) of the Mnx- ZnO(1-x) samples.

Eq. (6) was used to calculate the optical band gaps; hv is the calculated photon energy, Eg the optical band, α the calculated absorption coefficient, A-the energy dependent proportionality constant. was plotted against hv to determine the band gap energies.

| (6) |

This plot is known as the Tauc plot. The extrapolated Eg values from the Tauc plot were found to be 3.03, 3.18 and 3.21 eV for the undoped ZnO, 2 and 6 at%. Mn doped ZnO, respectively. A variation in the band gap is an indication of an adjustment of the ZnO electronic structure by Mn 2+ ions. According to Ali and co-authors [36] an upsurge in the calculated energy band gap of ZnO relative to dopant concentration can be ascribed to the spin exchange interaction between the Mn2+ ions and the band electrons i.e. the s-p electrons. Furthermore, the band gap widening can be correlated with the Burstein- Moss-effect as a result of the shifting in the position of Fermi level into the conduction band due to increased carrier concentration [41]. The position of the absorption edge and the band gap values are a clear indication that Mn doped ZnO provides an excellent broadband UV protection. It is worth to note that ZnO exhibited excellent absorption in the UV region especially the most harmful component of UV, the UVC radiation (λ < 280 nm). The absorption edge is slightly blue shift towards the UVB upon impregnation of Mn ions onto ZnO but it still lies way above the UVC region and therefore Mn doped ZnO can be effectively used for UV blocking.

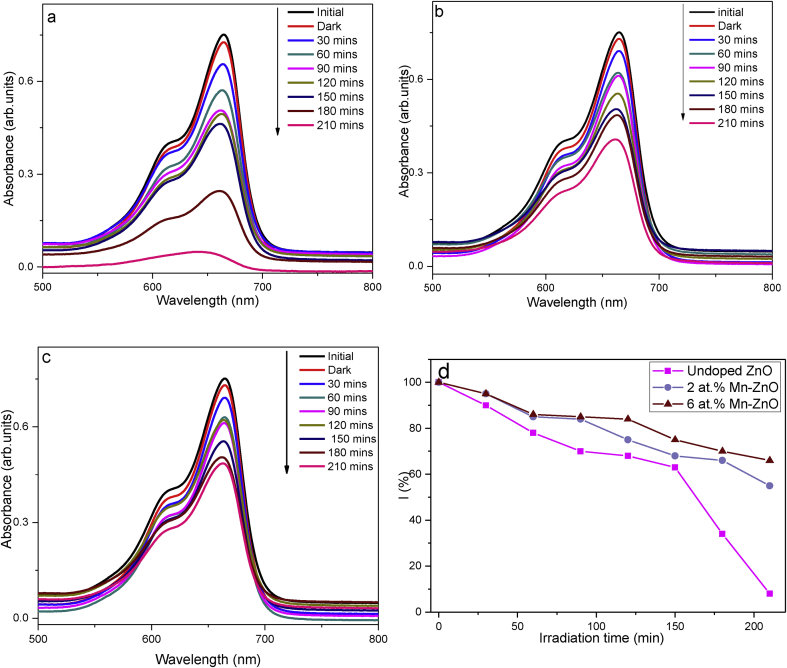

3.5. Evaluation of ROS utilization through photodegradation of MB

The rate of ROS generation and their utilization was examined through photocatalytic activity studies. These studies were done to assess the efficiency of Mn for the possibility of using Mn doped ZnO for UV protection applications. The time dependent profiles of the photocatalytic activities of Mnx- ZnO (1-x) nanopowders against methylene blue under UV irradiation are given in Figure 7. All spectra show a decrease on the intensity of the 665 nm MB peak as the time of UV irradiation increased, indicating that a reaction was taking place. Furthermore, it was observed, that pristine ZnO exhibited strong photocatalytic efficacy compared to all Mnx- ZnO (1-x) samples. An overall of 94 % of MB was degraded after 210 min of irradiation, using bare ZnO as the catalyst. Impregnation of Mn 2+ onto ZnO drastically reduced the photoactivity in the order: 6 at. % Mn–ZnO (36% activity) < 2 at.% Mn–ZnO (47% activity) < undoped ZnO (94% activity). Reduced dye-photoactivity by Mn2+ doped ZnO upon has previously been reported [42, 43, 44, 45, 46]. The UV shielding performance (I) of the samples was calculated using Eq. (7) as described by Ma et al. [47]:

| (7) |

Figure 7.

MB degradation spectral profiles of undoped ZnO (a), 2 at.% Mn doped ZnO (b) and 6 at.% Mn doped ZnO (c) photocatalysts. Bottom right (d) is a plot of UV shielding performance (I) in percentage as a function of time for the three photocatalysts.

A0 - initial absorbance of MB before irradiation; At - absorbance at time t (min). The obtained results as plotted clearly indicate the 6 at% Mn doped ZnO has a higher radiation shielding capability as compared to other samples.

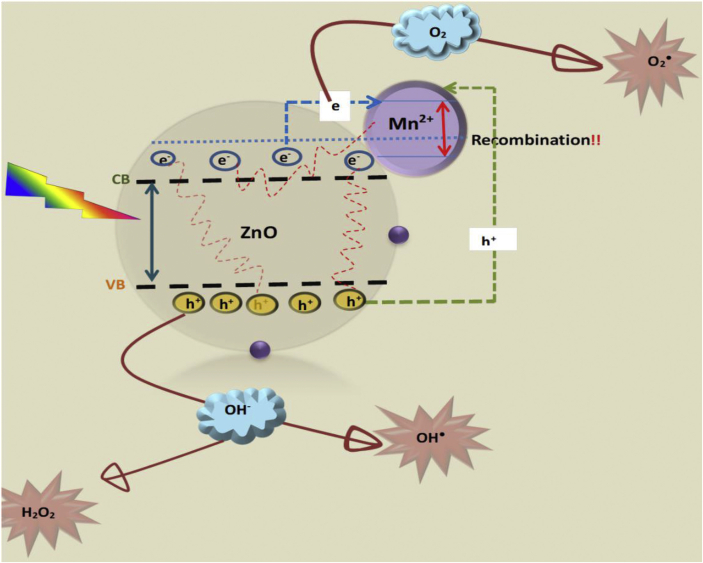

Mn2+ substitution on the hexagonal ZnO structure affects the electronic structure thus also affecting the photosensitivity of ZnO and formation of free radicals which are responsible for ROS generation. This may lead to a substantial reduction in generation of free electrons and energized holes. Crystal lattice defects are not the only source of recombination sites in a semiconductor [48]. Dopants can either act as electron traps or recombination centers. Mn2+ has been reported to create deep sub band energy levels which serve as recombination centers for photoinduced e−/h+ pair, leading to reduced activity [29, 49, 50]. Lesnik et al (2018) [2], highlighted that Mn ions trap the charges on the same sites which are then annihilated rapidly through intra-atomic relaxation. Therefore, increasing the Mn concentration leads to creation of more recombination sites, hence a gradual decrease in the photocatalytic activity with an increase in dopant concentration. The proposed photodegradation mechanism is as presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Proposed photocatalytic mechanism of Mn doped ZnO.

Irradiation leads to transfer of orbital electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). The presence of Mn on the surface of ZnO acts as a recombination center of the photogenerated e-/h+ pair, leading to less production of ROS such a H2O2 and OH∙

4. Conclusion

The crystallographic structure, morphology and optical properties of the sol gel processed Mnx-ZnO(1-x) (x = 0, 2, 6 at%) nanospheres were assessed. XRD, FTIR, SEM, TEM and Raman spectroscopy indicated that inclusion of Mn ions into the ZnO lattice did not alter its hexagonal wurtzite structure and no secondary phase was created. UV-Vis absorbance spectra showed that all the samples were highly absorbing in the UV region and may effectively be used as UV blockers. The photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue in the presence of Mnx- ZnO(1-x) decreased with increasing Mn2+ dopant concentration. The results demonstrated that doping ZnO with Mn can be used to suppress the oxidative stress induced by hazardous ROS through generation of recombination centres; thus the synthesised material can be used in UV shielding applications to protect skin and mammalian cells from possible UV induced damage. Mn doped ZnO can be used in fabrics and ointments for this specific application.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Kebadiretse Lefatshe: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Genene T. Mola: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Cosmas M. Muiva: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Office of Research, Development and Innovation, Botswana International University of Science and Technology (DVC/RDI/161/(R00017) and student grant S00095).

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Hee M., Patil U., Kochuveedu S., Soo C., Kim D.H. The effect of SiO2 shell on the suppression of photocatalytic activity of TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles. Bull. Kor. Chem. Soc. 2012;33 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lesnik M., Verhovsek D., Veronovski N., Grancer M., Drazic G., Soderznik K., Drofenik M. Hydrothermal synthesis of Mn-doped TiO2 with a strongly suppressed photocatalytic activity. Mater. Technol. 2018;52:411–416. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim B., Nataraj S., Yang K., Woo H. Synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activity of TiO2/SiO2 nanoparticles loaded on carbon nanofiber web. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010;10:3331–3335. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2010.2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J., Hsieh P., Naresh H.T.G., Huang M.H. Photocatalytic activity suppression of CdS nanoparticle-decorated Cu2O octahedra and rhombic dodecahedra. J. Phys. Chem. C Vols. Phys. Chem. C. 2018;122:12944–12950. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewicka Z.A., Yu W.W., Oliva B.L., Contreras E.Q., Colvin V.L. Photochemical behavior of nanoscale TiO2 and ZnO sunscreen. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2013;263:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ndiaye M.A., Nihal M., Wood G.S., Ahmad N. Skin, reactive oxygen species, and circadian clocks. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2014;20:2982–2996. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefatshe K., Muiva C., Kebaabetswe L. Extraction of nanocellulose and in-situ casting of ZnO/cellulose nanocomposite with enhanced photocatalytic and antibacterial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;164:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasnidawani J.N., Azlina H.N., Norita H., Bonnia N.N., Ratim S., Ali E.S. Synthesis of ZnO nanostructures using sol-gel method. Proc. Chem. 2016;19:211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang Y.-C., Chen C.-M., Guo J.-Y. Fabrication of novel ZnO nanoporous films for efficient photocatalytic applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018;356:340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan T., Lai C., Hamid S. Tunable band gap energy of Mn-doped ZnO nanoparticles using the coprecipitation technique. J. Nanomater. 2014:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S.S., Venkateswarlu P., Rao V.R., Rao G.N. Synthesis, characterization and optical properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int. Nano Lett. 2013;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z. Zinc oxide nanostructures: growth, properties and applications. J. Phys.: Condesed Matter. 2004;16:R829–R858. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J., Tsuzuki T., Sun L., Wang X. Reducing the photocatalytic activity of zinc oxide quantum dots by surface modification. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009;92:2083–2088. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L.-C., Yi-Jian Tua Y.-S., Kan R.-S., Huang C.-M. Characterization and photoreactivity of N-, S-, and C-doped ZnO under UV and visible light illumination. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2008;199:170–178. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuzuki T., He R., Wan J., Sun L., Wang X. Reduction of the photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanoparticles for UV protection applications. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2012;9:1017–1029. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudha M., Rajarajan M. Deactivation of photocatalytically active ZnO nanoparticleby surface capping with poly vinylpyrrolidone. J. Appl. Chem. 2013;3:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morlando A., Sencadas V., Cardillo D., Konstantinov K. Suppression of the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles encapsulated by chitosan through a spray-drying method with potential for use in sunblocking applications. Powder Technol. 2018;329:252–259. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akhil K., Jayakumar J., Gayathri G., S Khan S. Effect of various capping agents on photocatalytic, antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of ZnO nanoparticles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016;160:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo J., Bui H.V., Valdesueiro D., Yuan S., Liang B., Ommen J.R.v. Suppressing the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanoparticles by extremely thin Al2O3 films grown by gas-phase deposition at ambient conditions. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:1–19. doi: 10.3390/nano8020061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaramillo-Páez C., Navío J., Hidalgo M. Silver-modified ZnO highly UV-photoactive. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018;356:112–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habba Y.G., Capochichi-Gnambodoe M., Leprince-Wang Y. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of iron-doped ZnO nanowires for water purification. Appl. Sci. 2017;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etacheri V., Roshan R., Kumar V. Mg-doped ZnO nanoparticles for efficient sunlight-driven photocatalysis. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2012;4:2717–2725. doi: 10.1021/am300359h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li W., Wang G., Chen C., Liao J., Li Z. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanowires doped with Mn2+ and Co2+ ions. Nanomaterials. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.3390/nano7010020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuzuki T., He R., Dodd A., Saunders M. Challenges in determining the location of dopants, to study the influence of metal doping on the photocatalytic activities of ZnO nanopowders. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:1–19. doi: 10.3390/nano9030481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vladut C., Mihaiu S., Mocioiu O., Atkinson I., Pandele-Cusu J., Anghel E.M., Calderon-Moreno J.M., Zaharescu M. Thermal studies of Mn2+-doped ZnO powders formation by sol–gel. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed F., Kumar S., Arshi N., Heo M., Koo B.H. Direct relationship between lattice volume, bandgap, morphology and magnetization of transition metals (Cr, Mn and Fe)-doped ZnO nanostructures. Acta Mater. August 2012;60:5190–5196. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hao Y.-M., Lou S.-Y., Zhou S.-M., Yuan R.-J., Zhu G.-Y., Li N. Structural, optical, and magnetic studies of manganese-doped zinc oxide hierarchical microspheres by self-assembly of nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012;7:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-7-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S., Chatterjee S., Chattopadhyay K., Ghosh A.K. Sol−Gel-Derived ZnO:Mn nanocrystals: study of structural, Raman,and optical properties. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012;116 16700−1670. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Othman A.A., Osman M.A., Ibrahim E., Ali M.A., Abdelrehim A.G. Mn-doped ZnO nanocrystals synthesized by sonochemical method: structural, photoluminescence, and magnetic properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 2017;219:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vladut C., Mihaiu S., Tenea E., Preda S., Calderon-Moreno J.M., Anastasescu M., Stroescu H., Atkinson I., Gartner M., Moldovan C., Zaharescu M. Optical and piezoelectric properties of Mn-doped ZnO films deposited by sol-gel and hydrothermal methods. J. Nanomater. 2019;3:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chin H., Chao L.S. The effect of thermal annealing processes on structural and photoluminescence of zinc oxide thin film. J. Nanomater. 2013:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zak A.K., Razali R., Majid W., Darroudi M. Synthesis and characterization of a narrow size distribution of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011;6:1399–1403. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S19693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Juma A.O., Arbab E.A., Muiva C.M., Lepodise L.M., Mola G.T. Synthesis and characterization of CuO-NiO-ZnO mixed metal oxide. J. Alloys Compd. 2017;723:866–872. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srivastava A., Kumar J. Effect of zinc addition and vacuum annealing time on the properties of spin-coated low-cost transparent conducting 1 at% Ga-ZnO thin films. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2013;14 doi: 10.1088/1468-6996/14/6/065002. 065002-65016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moditswe C., Muiva C., Juma A. Highly conductive and transparent Ga-doped ZnO thin films deposited by chemical spray pyrolysi. Optik. 2016;127:8317–8325. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ali A.G., Dejene F., Swart H. Effect of Mn doping on the structural and opticalproperties of sol-gel derived ZnO nanoparticles. Cent. Eur. J. Phys. 2012;10:478–484. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shatnawi M., Alsmadi A.M., Bsoul I., Salameh B., Mathai M., Alnawashi G., Alzoubi G.M., Al-Dweri F., Bawaaneh M.S. Influence of Mn doping on the magnetic and optical properties of ZnO nanocrystalline particles. Results Phys. 2016;6:1064–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonifácio M., Lira H., Neiva L., Kiminami R., Gama L. Nanoparticles of ZnO dopedwith Mn: structural and morphological characteristics. Mater. Res. 2017;20:1044–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Husain S., Alkhtaby L.A., Giorgetti E., Zoppi A., Miranda M.M. Effect of Mn doping on structural and optical properties of sol gel derived ZnO nanoparticles. J. Lumin. 2014;145:132–137. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Das J., Mishr D.K., Srinivasu V.V., Sahu D.R., Roul B.K. Photoluminescence and Raman studies for the confirmation of oxygen vacancies to induce ferromagnetism in Fe doped Mn:ZnO compound. J. Magn. Magn Mater. 2015;382:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menon A.S., Kalarikkal N., Thomas S. Studies on structural and optical properties of ZnO and Mn-doped ZnO nanopowders. Indian J. NanoSci. 2013;1:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao X., Zhou B., Yuan R. Doping a metal (Ag, Al, Mn, Ni and Zn) on TiO2 nanotubes and its effect on Rhodamine B photocatalytic oxidation. Environ. Eng. Res. 2015;20:329–335. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuzuki T., Smith Z., Parker A., He R., Wang X. Photocatalytic activity of manganese-doped ZnO nanocrystalline powders. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2009;45:58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Türkyılmaz Ş.Ş., Güy N., Özacar M. Photocatalytic efficiencies of Ni, Mn, Fe and Ag doped ZnO nanostructures synthesized by hydrothermal method: the synergistic/antagonistic effect between ZnO and metals. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2017;341:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaur J., Singhal S. Facile synthesis of ZnO and transition metal doped ZnO nanoparticles for the photocatalytic degradation of Methyl Orange. Ceram. Int. 2014;40(5):7417–7424. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rekha K., Nirmala M., Nair M.G., Anukaliani A. Structural, optical, photocatalytic and antibacterial activity of zinc oxide and manganese doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 2010;405(15):3180–3185. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma W., Ding Y., Zhang M., ShutingGao, Li Y. Nature-inspired chemistry toward hierarchical superhydrophobic, antibacterial and biocompatible nanofibrous membranes for effective UV-shielding, self-cleaning and oil-water separation. J. Hazard Mater. 2019:1–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtani B. Titania photocatalysis beyond recombination: a critical review. Catalysts. 2013;3:942–953. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bharti B., Kumar S., Lee H., Kumar R. Formation of oxygen vacancies and Ti3+ state in TiO2 thin film and enhanced optical properties by air plasma treatment. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep32355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dodd A., McKinley A., Tsuzuk T., Saunders M. Tailoring the Photocatalytic activity of nanoparticulate zinc oxide by transition metal oxide doping. Mater. Phys. Chem. 2009;114:382–386. [Google Scholar]