Summary

Background

The infection caused by the recently identified SARS‐CoV‐2, called coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19), has rapidly spread throughout the world. With the exponential increase of patients worldwide, the clinical spectrum of COVID‐19 is being better defined and new symptoms are emerging. Numerous reports are documenting the occurrence of different cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID‐19.

Objectives

To provide a brief overview of cutaneous lesions associated with COVID‐19.

Methods

A literature search was performed in the PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases up to 30 April 2020. This narrative review summarizes the available data regarding the clinical and histological features of COVID‐19‐associated skin manifestations.

Results

The literature reports showed a great heterogeneity in COVID‐19‐associated cutaneous manifestations, as well as in their latency periods and associated extracutaneous symptoms. Pathogenic mechanisms are unknown, although the roles of a hyperactive immune response, complement activation and microvascular injury have been hypothesized. Based on our experience and the literature data, we subdivided the reported cutaneous lesions into six main clinical patterns: (i) urticarial rash; (ii) confluent erythematous–maculopapular–morbilliform rash; (iii) papulovesicular exanthem; (iv) chilblain‐like acral pattern; (v) livedo reticularis–livedo racemosa‐like pattern; and (vi) purpuric ‘vasculitic’ pattern. These six patterns can be merged into two main groups: the first – inflammatory and exanthematous – includes the first three groups listed above, and the second includes the vasculopathic and vasculitic lesions of the last three groups.

Conclusions

The possible presence of cutaneous findings leading to suspect COVID‐19 puts dermatologists in a relevant position. Further studies are needed to delineate the diagnostic and prognostic values of such cutaneous manifestations.

A novel zoonotic enveloped RNA virus of the family Coronaviridae, which has been named ‘severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2’ (SARS‐CoV‐2), was identified in hospitalized patients with pneumonia in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The infection caused by the virus, called coronavirus disease‐19 (COVID‐19), has rapidly spread throughout the world, becoming pandemic in early March 2020.1

The clinical spectrum of COVID‐19 is rather heterogeneous, ranging from unapparent or mild symptoms to critical fatal forms with respiratory failure, septic shock or multiorgan dysfunction. The clinical features at onset of illness vary, but, over the disease course, patients present mainly with fever and respiratory symptoms. However, various signs and symptoms can occur, and among the most common are fever, cough, fatigue, anorexia, shortness of breath, sputum production, myalgia, dyspnoea, rhinorrhoea, ageusia, anosmia, pharyngodynia, headache and chills.1 With the exponential increase of infected patients worldwide, the clinical characteristics of COVID‐19 are being better defined and new symptoms are emerging.

In most of the early reports from China, cutaneous lesions were not generally included in the COVID‐19 clinical spectrum, apart from a few exceptions. For instance, Guan et al. described skin rash in 0·2% of 1099 hospitalized patients, without specifying clinical patterns or further details.2 Hoehl et al. observed a faint rash and minimal pharyngitis in one traveller returning from Wuhan to Germany in February 2020 who tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 by real‐time reverse‐transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) of her throat swab.3 Subsequently, a case of COVID‐19 presenting with purpuric lesions mimicking dengue has been reported.4 In Iran, the clinical findings of COVID‐19 found in a 15‐day‐old neonate were fever, lethargy, respiratory distress without cough and cutaneous mottling.5

Another report, which analysed a series of 88 patients with COVID‐19 to describe the rate and type of skin lesions, drew the attention of the scientific community to COVID‐19‐associated cutaneous manifestations.6 In all of these patients, history of intake of any new drug in the previous 15 days was excluded. Cutaneous manifestations developed in 18 patients (20%) either at the onset of the disease (n = 8) or after admission (n = 10), and consisted of erythematous rash (n = 14), widespread urticaria (n = 3) and chickenpox‐like vesicles (n = 1). The trunk was the most frequently affected area, and itch was mild or absent. Skin lesions usually disappeared in a few days and did not show any apparent correlation with COVID‐19 severity.

Subsequently, various reports of skin manifestations in patients with COVID‐19 have been published. It should be kept in mind that, at the beginning of this vast outbreak, the rapidly increasing rate of infected patients and the parallel multitude of severe and critical patients could have hampered systematic skin assessments. Therefore, cutaneous lesions are likely to have been underestimated for obvious reasons, including the paucity of dermatology consultations in this group of patients.7 Moreover, cutaneous lesions may have been neglected as their duration can be very short and local symptoms can be minimal or absent. The difficulty in determining the actual prevalence of COVID‐19‐associated skin manifestations has also been linked to the fact that in some countries only patients with respiratory illness or requiring hospitalization are screened.8

The aim of our article is to provide a brief overview of the cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID‐19, accepting the preliminary nature of such data.

Methods

A literature search in the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science was conducted up to 30 April 2020, using the term ‘COVID‐19’ in combination with ‘skin’, ‘cutaneous manifestations’, ‘eruption’, ‘rash’, ‘exanthem’, ‘urticarial’, ‘chilblain’, ‘livedo’ and ‘purpura’ in order to collect reports of skin manifestations described in patients with COVID‐19. Given the limited number of papers, we included all of the available clinical reports dealing with this very recent topic, most of which concerned individual cases or small case series. Articles were selected based on title and abstract. Full texts were then carefully read to evaluate the article content. Articles from the references cited in the retrieved papers were also manually searched as appropriate.

Results

The present review was based on the available literature to date, which consists predominantly of case reports and small case series, all graded as having low‐quality evidence. Tables 1 and 2 contain a partial list of case reports,4,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 corresponding only to the descriptions of single cases with detailed information. Such reports refer to patients with laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19. In only one case,13 although multiple nucleic acid tests were negative, the infection was diagnosed on the basis of both chest computerized tomography (CT) scan findings and close contact with people with COVID‐19. Case series with more than three patients are not contained in these tables and are described in depth throughout the text. The only report with higher‐quality evidence is that by Galván Casas et al. on a large cohort of patients,32 which allowed the authors to stratify COVID‐19‐related skin manifestations into five categories. Overall, the case reports suggest that skin lesions developed more often after the onset of COVID‐19 symptoms, with a variable latency period. A simultaneous onset was sometimes noted, especially for fever. More rarely, skin lesions occurred in the prodromal phase, shortly before the appearance of typical COVID‐19 symptoms.9 27 Reports concerning asymptomatic patients also exist. Different clinical patterns were described.

Table 1.

Case reports of exanthems and inflammatory eruptions in patients with COVID‐19

| Study | Sex, age (years) Relevant history (if present) | Clinical features of skin lesions | Respiratory and other relevant symptoms or signs in relation to the onset of skin lesions | Treatments for COVID‐19 | Outcome of skin lesions |

| Henry9 | Female (27) | Pruritic urticarial rash | Prodromal odynophagia; concomitant arthralgia; chills, chest pain and fever (up to 39·2 °C) 48 h after the onset of skin lesions | Paracetamol | Slow improvement (n.s.) |

| Fernandez‐Nieto10 | Female (32) | Urticarial rash | COVID‐19 symptoms (n.s.) started 6 days before | Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin | Improvement after 5 days |

| Quintana‐Castanedo11 | Male (61) | Mildly itchy urticarial exanthem | Concomitant body temperature of 37·3 °C. No symptoms (RT‐PCR performed due to epidemiological link) | None | Disappearance after 7 days |

| van Damme12 | Male (71) Obesity, DM, AH, OSAHS, RF on dialysis, previous stroke, hypercholesterolaemia | Urticarial rash | Concomitant fever and general weakness. Progressive deterioration up to respiratory failure and death | n.s. | Improvement |

| Female (39) | Pruritic generalized urticarial rash | Concomitant fever (38·3 °C) with chills, myalgia and headache, then rhinorrhoea, mild dry cough, dyspnoea; later anosmia and ageusia | n.s. | Gradual improvement | |

| Lu13 | One case (n.s.) | Urticarial rash | Mild dry cough started a few days before | Ribavirin and interferon | n.s. |

| Morey‐Olivé14 | Male (6) | Erythematous, nonpruritic maculopapular exanthem | Low‐grade fever 2 days before | None | Disappearance after 5 days |

| Female (2 months) | Urticaria‐like exanthem | Concomitant low‐grade fever | None | Disappearance after 5 days | |

| Rivera‐Oyola15 | Male (60) Mitral valve replacement, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, depression | Asymptomatic erythematous maculopapular rash on the back, flanks, groin and upper thighs becoming purpuric 1 week later | Low‐grade fever (38 °C), myalgias, fatigue, mild cough 3 days before | None | n.s. |

| Female (60) | Generalized, pruritic urticarial rash | Low‐grade fever (38·2 °C), myalgias, fatigue, mild cough, gastrointestinal symptoms started 9 days before | None | Disappearance after a few days | |

| Amatore16 | Male (39) | Nonpruritic erythematous, oedematous, annular and circinate fixed plaques on upper limbs, chest, neck, abdomen and palms | Concomitant fever (39 °C). Pulmonary findings suggestive of COVID‐19 on CT scan without respiratory symptoms | Hydroxychloroquine | Disappearance after 8 days |

| Najarian17 | Male (58) | Pruritic diffuse morbilliform rash | Cough, pain in legs and hands shortly before; no fever | Azithromycin and benzonatate | Disappearance after a few days |

| Hunt18 | Male (20) | Nonpruritic diffuse, morbilliform rash, sparing the face | Concomitant fever; initial signs suggestive of an upper respiratory infection, with pneumonia diagnosed 6 days later | n.s. | n.s. |

| Avellana Moreno19 | Female (32) | Generalized, pruritic morbilliform rash (petechial and erythematous maculopapular lesions and a scaly reaction on the 4th day) | Fever, myalgia, asthenia 6 days before; later cough, diarrhoea | Paracetamol | Disappearance after the 4th day (n.s.) |

| Genovese20 | Female (8) | Asymptomatic papulovesicular (varicella‐like) rash on the trunk | Mild cough started 3 days before. Mild transient thrombocytopenia. Mild fever 2 days after the onset of skin lesions | None | Disappearance after 7 days |

| Mahé21 | Female (64) DM | Erythematous symmetrical flexural rash (antecubital folds, then trunk and axillary folds) | Prodromal fever (up to 40 °C) and asthenia (4 days before); concomitant cough with confirmation of interstitial pneumonia and persistent fever | Paracetamol from fever onset until day 16 | Disappearance after 5 days (day 9 of the disease) |

| Ahouach22 | Female (57) | Diffuse erythematous blanching maculopapular lesions, with symptoms (burning sensation) only on the palms | Fever (39 °C) 2 days before. Concomitant dry cough. Typical thorax CT scan findings | Paracetamol | Disappearance within 9 days |

| Estébanez23 | Female (28) | Pruritic erythematous‐yellowish papules on both heels (13 days after being tested), becoming plaques 3 days later | Initially dry cough, nasal congestion, fatigue, myalgias and arthralgias without fever, then diarrhoea, ageusia and anosmia | Paracetamol for a few days | n.s. |

| Jimenez‐Cauhe24 | Female (84) AH, dyslipidaemia | Flexural erythematous‐purpuric macules, mildly pruriginous, mainly in the periaxillary area (on the 3rd hospital day) | Respiratory symptoms requiring hospitalization 11 days before | Hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir | n.s. |

| Joob4 | One case (n.s.) | Petechial rash, misdiagnosed as dengue | Presence of thrombocytopenia. Further presentation of respiratory problems requiring referral to a tertiary medical centre (other information not given) | n.s. | n.s. |

| Diaz‐Guimaraens25 | Male (48) AH | Mildly pruritic, maculopapular and petechial rash, with periflexural distribution | Fever (up to 39 °C) 3 days before, along with chest pain and shortness of breath. Hospitalization for pneumonia | Hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir/ritonavir and azithromycin | Disappearance after 5 days |

| Sanchez26 | n.s. (elderly) AH, DM, peripheral artery disease, RF | Digitate papulosquamous eruption on the trunk, upper limbs and thighs (on the 2nd hospital day) | Fever, fatigue, dyspnoea 1 week before hospitalization for acute respiratory distress. Death | n.s. | Disappearance within 7 days |

| Gianotti27 | Female (59) | Widespread erythematous macules on the arms, trunk and lower limbs (on the 3rd hospital day) | Bilateral interstitial pneumonia requiring hospitalization | Lopinavir/ritonavir, heparin and levofloxacin | Improvement within 5 days |

| Female (89) | Erythematous papular exanthem on the trunk and arms (on admission) | Fever and cough started 7 days before | Ceftriaxone and azithromycin | Improvement after 8 days | |

| Male (57) | Widespread pruritic eruption of erythematous macules and papules | Fever, headache, cough and arthralgia 2 days after the onset of the rash | Levofloxacin and hydroxychloroquine | Improvement after 10 days | |

AH, arterial hypertension; CT, computed tomography; DM, diabetes mellitus; n.s., not specified; OSAHS, obstructive sleep apnoea–hypopnoea syndrome; RF, renal failure; RT‐PCR, real‐time reverse‐transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Table 2.

Case reports of vasculopathic skin lesions in patients with COVID‐19

| Study | Sex, age (years) Relevant history (if present) | Clinical features of skin lesions | Respiratory symptoms and other relevant findings | Treatments for COVID‐19 |

| Manalo28 | Male (67) | Nonpruritic LR‐like livedoid patch on the right thigh. Disappearance after 19 h | Low‐grade fever, nasal congestion, postnasal drip, cough, shortness of breath 7 days before; concomitant weakness and transient haematuria | n.s. |

| Female (47) CD, HT, past portal vein thrombosis | Asymptomatic LR‐like rash on right leg immediately after sunlight exposure (10 days after testing positive). Disappearance after 20 min | Previous appearance of mild headache, sinus pressure, anosmia and fever (up to 37·9 °C) | n.s. | |

| Alramthan29 | Female (27) | Red–purple papules on the dorsal aspect of fingers bilaterally in both cases (also subungual erythema in the right thumb in the second case) | No symptoms | None |

| Female (35) | No symptoms | None | ||

| Kolivras30 | Male (23) Psoriasis (secukinumab stopped 1 month before) | Violaceous, infiltrated and painful plaques on the toes and lateral aspects of the feet | Low‐grade fever (37·7 °C) and dry cough 3 days before | None |

| Magro31 | Male (32) OASA, anabolic steroid use (current use of testosterone) | After 4 days on ventilator support, retiform purpura with surrounding inflammation on buttocks | Fever, cough, then dyspnoea up to acute respiratory failure (elevated D‐dimer and INR, normal PTT and platelet count) | Mechanical ventilation, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, remdesivir |

| Female (66) | On hospital day 11, dusky livedoid patches on palms and soles bilaterally | Fever, cough, diarrhoea, chest pain for 9 days. Hypoxaemia on admission. Comatose state after further 3 days (low platelet count, high D‐dimer, normal INR and PTT) | Hydroxychloroquine, enoxaparin, intubation, renal replacement | |

| Female (40) | Mildly purpuric reticulated eruptions on the chest, legs and arms (livedo racemosa) | Dry cough, fever, myalgias, diarrhoea for 2 weeks and progressive dyspnoea. Then severe reduction of left ventricular function, respiratory failure, shock (elevated D‐dimer and INR, normal platelet count and PTT) | Intubation |

CD, coeliac disease; HT, Hashimoto thyroiditis; INR, international normalized ratio; LR, livedo reticularis; n.s., not specified; OASA, obesity‐associated sleep apnoea; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

Classification of COVID‐19‐associated cutaneous manifestations

A classification of cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19 has been proposed based on the results of a prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain using a representative sample of 375 cases.32 Five clinical patterns were recognized: (i) acral areas of erythema with vesicles or pustules (pseudo‐chilblains) (19%); (ii) other vesicular eruptions (9%); (iii) urticarial lesions (19%); (iv) maculopapular eruptions (47%); and (v) livedo or necrosis (6%). Vesicular eruptions were found to appear early in the course of the disease (before other symptoms in 15% of cases), chilblain‐like lesions frequently appeared late over the disease course, and the remaining patterns tended to develop during the illness phase. Chilblain‐like lesions also tended to have a longer duration than the other forms. A gradient of severity of COVID‐19 could be observed ranging from less severe disease in acral lesions to most severe in the case of livedoid presentations.32 Nevertheless, transient livedoid eruptions have also been reported in the literature.28

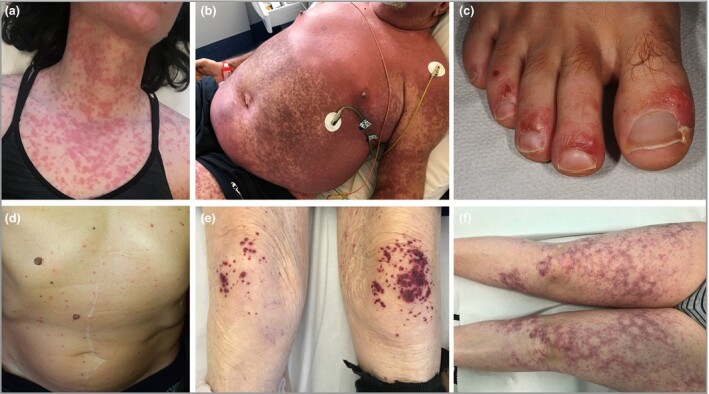

Based on our experience, our review of the literature and the classification by Galván Casas et al., who studied a cohort of 375 Spanish patients,32 we subdivided the reported cutaneous lesions into six main clinical patterns: (i) urticarial rash (Figure 1a),6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 (ii) confluent erythematous–maculopapular–morbilliform rash (Figure 1b),3,6,14,15,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 (iii) papulovesicular exanthem (Figure 1d),6,20,33,34,35 (iv) chilblain‐like acral pattern (Figure 1c),8,29,30,33,36,37,38,39,40,41 (v) livedo reticularis–livedo racemosa‐like pattern (Figure 1f)28 31 and (vi) purpuric ‘vasculitic’ pattern (Figure 1e).31 33 Although livedo reticularis/racemosa and purpura could be included in the same group, we decided to split them into two separate categories, keeping in mind the hypothesis that the former has a vasculopathic origin while the latter has a true vasculitic pathogenesis.

Figure 1.

COVID‐19‐associated cutaneous manifestations. (a) Urticarial rash. (b) Combination of confluent erythematous rash on the chest with petechial lesions on the abdomen and upper extremities. (c) Acral chilblain‐like lesions on the foot. (d) Vesicular exanthem. (e) Palpable purpura on the knees. (f) Livedo racemosa‐like lesions on the thighs. All of the photographs belong to the authors’ own collection.

For clarity of exposition, the six patterns were assigned to two broader categories: inflammatory or exanthematous eruptions, including urticarial rash, confluent erythematous–maculopapular–morbilliform rash and papulovesicular exanthem (Table 1); and vasculopathic or vasculitic lesions, including chilblain‐like acral pattern, livedo reticularis–livedo racemosa‐like pattern and purpuric ‘vasculitic’ pattern (Table 2).

Exanthems and other inflammatory eruptions

These encompass confluent erythematous, maculopapular, morbilliform and urticarial presentations, similar to nonspecific rashes in the course of common viral infections. In the large cohort of 375 patients reported by Galván Casas et al., exanthems were the most commonly reported skin manifestations. In particular, maculopapular eruptions, urticarial lesions and vesicular eruptions accounted for 47%, 19% and 9% of all cutaneous manifestations, respectively.32 The main differential diagnoses in such presentations are cutaneous drug reactions. Itch was of variable intensity and sometimes absent. Urticarial and maculopapular exanthems have been suggested to appear simultaneously with systemic symptoms, to last approximately 1 week and to be associated with severe COVID‐19.32 The possible presence of urticarial manifestations is unsurprising given that viral agents have been recognized as an important trigger of acute urticaria and urticaria‐like rash, especially in children.42 43 Erythematous flexural lesions were also noted,21 as well as localized plaques on the heels,23 and a papulosquamous eruption, clinically reminiscent of pityriasis rosea.26 Gisondi et al. gave a brief mention of a diffuse papular eruption seen in a woman with COVID‐19 febrile infection.44 Lesions resembling erythema multiforme have also been described.32

In some case reports (Table 1) the outcomes were not specified. When available, the data on the natural evolution generally indicated an overall short duration of skin involvement.

Hedou et al. analysed, in a prospective study, the incidence and types of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID‐19 in France.8 In total, 103 patients with confirmed infection (71 women) with a mean age of 47 years were evaluated. Among them, 76 were treated at home, while 23 were admitted to conventional hospital wards and four to intensive care units. Only five (5%) presented with skin manifestations: erythematous rash (n = 2) and urticaria (n = 2), mainly located on the face and upper body, and one case of oral herpes simplex virus reactivation in an intubated patient. Cutaneous signs appeared during the prodromal phase in a patient with urticaria and during the illness in the remaining patients. All eruptions were associated with itching and disappeared within 6 days (median 2 days).

A further retrospective observational study recorded the occurrence of inflammatory lesions, usually a few days after the onset of COVID‐19 systemic symptoms, in seven patients, including exanthem (n = 4), varicella‐like vesicles (n = 2) and cold urticaria (n = 1).33 An eruption worthy of separate comment is that characterized by vesicular or papulovesicular lesions resembling varicella (Table 1).6,20,34,35 In the cohort studied by Galván Casas et al., vesicular lesions usually appeared in middle‐aged patients, before the onset of systemic symptoms in 15% of cases, and were associated with intermediate severity of COVID‐19.32

Eight Italian dermatology units collected clinical data on 22 patients with COVID‐19 (16 male, median age 60 years) and varicella‐like lesions.34 In that study, which two authors of the present article (A.V.M. and G.G.) contributed to, the skin lesions usually appeared 3 days after systemic symptoms and disappeared after 8 days, without scarring. Systemic symptoms were most commonly fever (98%), followed by cough (73%), headache (50%), weakness (50%), coryza (46%) and dyspnoea (41%), and less frequently hyposmia, hypogeusia, pharyngodynia, diarrhoea and myalgia. Death occurred in three patients. The authors reported that typical characteristics of the rash are frequent trunk involvement, scattered distribution and mild or absent pruritus, speculating that this kind of eruption can be an almost specific COVID‐19‐associated cutaneous manifestation.34 The case of a paediatric patient included in this series has been described in detail in another subsequently published report.20

Tammaro et al. presented data from their combined experience in Rome, Italy, and Barcelona, Spain, and focused on lesions similar to those found in infections caused by members of the family Herpesviridae.35 In particular, they described the case of a woman from Barcelona who developed numerous, isolated vesicular lesions on the back 8 days after the diagnosis of COVID‐19. In the same paper, they identified, among 130 patients with COVID‐19 hospitalized in Rome, two (1·5%) cases presenting with isolated erythematous–vesicular herpetiform lesions on their trunk accompanied by mild pruritus.

Some cutaneous rashes encountered in association with COVID‐19 were characterized by a petechial component,15,19,24,25 which may have been secondary to thrombocytopenia.4 These cases were not included in the purpuric ‘vasculitic’ pattern of our classification because, in our opinion, petechial lesions in such circumstances were only an accompanying finding of inflammatory nonvasculitic eruptions, which were predominantly characterized by macular or maculopapular lesions. Petechial lesions could also represent a secondary phenomenon during the natural evolution of the exanthem, as described in a case in which a maculopapular rash became purpuric 1 week later.15 Erythematous–purpuric, maculopapular and petechial lesions with a tendency towards a flexural or periflexural distribution have also been reported.24 25

Vasculopathic or vasculitic lesions

In a retrospective observational French study, seven patients presented with vascular lesions as follows: violaceous macules with ‘porcelain‐like’ appearance (n = 1), livedo (n = 1), non‐necrotic purpura (n = 1), necrotic purpura (n = 1), eruptive cherry angiomas (n = 1), chilblain‐like lesions alone (n = 1) and chilblain‐like lesions associated with Raynaud phenomenon (n = 1).33 Manifestations defined as petechiae, tiny bruises or livedoid eruptions have been linked to COVID‐19, as reported by an article in a news magazine published by the Society of Hospital Medicine.45 Furthermore, it was speculated that these manifestations might be a result of small‐blood‐vessel occlusion, whose pathogenic mechanisms (e.g. neurogenic, microthrombotic or immune complex mediated) are as yet unknown.

Intriguingly, Magro et al. documented the presence of thrombotic microvascular damage in the lung and/or skin of five patients with critical COVID‐19.31 In three of these patients, purpuric or livedoid skin lesions (Table 2) characterized by a pauci‐inflammatory microthrombotic vasculopathy were described (Table 3). Deposition of complement components within the skin and lung microvasculature was detected (Table 3), with colocalization of SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific spike glycoproteins. It was suggested that severe disease might induce a catastrophic generalized microvascular injury syndrome mediated by intense activation of the alternative and lectin complement pathways and an associated procoagulant state.31

Table 3.

Histopathological features of cutaneous manifestations found in patients with COVID‐19

| Study | Clinical form | Main histopathological features |

| Fernandez‐Nieto10 | Urticarial rash | Upper dermal oedema |

| Perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and some eosinophils | ||

| Amatore16 | Urticarial figurate lesions | Lichenoid and vacuolar interface dermatitis |

| Mild spongiosis and dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes | ||

| Papillary dermal oedema with superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and occasional neutrophils | ||

| Ahouach22 | Erythematous maculopapular rash | Slight spongiosis and basal cell vacuolation |

| Mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | ||

| Gianotti27 | Erythematous eruption | Superficial perivascular dermatitis with slight lymphocytic exocytosis |

| Presence of a small thrombus in a vessel in the mid dermis | ||

| Swollen thrombosed vessels with neutrophils, eosinophils and nuclear debris patchily distributed in the dermis | ||

| Erythematous papular exanthem | Superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis | |

| Cuffs of lymphocytes surrounding blood vessels in a vasculitic pattern | ||

| In the mid dermis extravasated red blood cells from damaged vessels | ||

| Erythematous papular eruption | Superficial perivascular vesicular dermatitis, with features reminiscent of Grover disease | |

| Focal acantholytic suprabasal clefts | ||

| Dyskeratotic and ballooning herpes‐like keratinocytes | ||

| Presence of a nest of Langerhans cells within the epidermis | ||

| Patchy bandlike infiltration with occasional necrotic keratinocytes and minimal lymphocytic satellitosis | ||

| In the dermis, swollen vessels, with dense lymphocyte infiltration, mixed with rare eosinophils | ||

| Sanchez26 | Papulosquamous eruption | Focal parakeratosis in the epidermis |

| Mild spongiosis, with a few spongiotic vesicles containing lymphocytes and Langerhans cells | ||

| Papillary dermal oedema with moderate superficial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate | ||

| Diaz‐Guimaraens25 | Maculopapular and petechial rash | Focal parakeratosis and isolated dyskeratotic cells |

| Focal papillary dermal oedema and superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | ||

| Extravasated red cells | ||

| No signs of thrombotic vasculopathy | ||

| Rivera‐Oyola15 | Erythematous maculopapular rash with purpuric evolution | Mild perivascular infiltrate of predominantly mononuclear cells in the superficial dermis |

| Scattered foci of hydropic changes in the epidermis and slight spongiosis | ||

| Minimal acanthosis and focal parakeratosis | ||

| Marzano34 | Varicella‐like lesions (n = 7) | Features compatible with viral exanthem |

| Recalcati41 | Targetoid nonacral lesions (n = 2) | Mild superficial perivascular dermatitis |

| Perniosis‐like lesions on the fingers (n = 2) | Diffuse dense dermal–hypodermal lymphoid infiltrate with a prevalent perivascular pattern | |

| Signs of endothelial activation | ||

| Kolivras30 | Chilblain‐like lesions | Epidermal basal vacuolar alteration and scattered necrotic keratinocytes |

| Superficial and deep lichenoid, perivascular and perieccrine infiltrate of lymphocytes and occasional plasma cells | ||

| Presence of some nuclear debris without neutrophils | ||

| Plump endothelial cells in the venules surrounded by lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate | ||

| Absence of intraluminal thrombi or fibrin within venule walls | ||

| Magro31 | Retiform purpura | Thrombogenic vasculopathy |

| Extensive necrosis of the epidermis and adnexal structures | ||

| Interstitial and perivascular neutrophilia with prominent leucocytoclasia (IHC: extensive deposits of C5b‐9 within the microvasculature) | ||

| Palmoplantar livedoid patches | Superficial vascular ectasia and occlusive arterial thrombus within the deeper dermis | |

| Absence of inflammation (IHC: extensive vascular deposits of C5b‐9, C3d and C4d throughout the dermis, with marked deposition in an occluded artery) | ||

| Livedo racemosa | Modest perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial dermis along with deeper‐seated small thrombi within rare venules of the deep dermis, in the absence of a clear vasculitis (IHC: significant vascular deposits of C5b‐9 and C4d) |

IHC, immunohistochemical assessment.

It is worth mentioning that a group of Chinese authors reported the development of severe acro‐ischaemia in a few patients in intensive care units in Wuhan, manifesting as finger or toe cyanosis, skin blisters and dry gangrene, resulting from a hypercoagulable status or confirmed disseminated intravascular coagulation.46

Alramthan et al. hypothesized that acral ischaemia could be responsible for the acral red‐purple perniosis‐like papules noted in two asymptomatic young women.29 Very mild processes of intravascular coagulation and microthrombosis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of transient localized livedo reticularis‐like lesions.28 Biopsies were not taken in such cases because of the fleeting nature of the skin lesions. Therefore, livedoid skin lesions might be mediated by an occlusive thrombotic microvasculopathy of variable magnitude. In many cases, these lesions are likely to be mild and transient. Nevertheless, Manalo et al., describing cases of transitory livedo reticularis‐like patches (Table 2), declared that platelet count, coagulation studies, and assessment of fibrin degradation products in these patients would be enlightening.28 In patients with severe COVID‐19, vasculopathic lesions might be more pronounced and/or persistent, being the epiphenomenon of uncontrolled systemic microvascular damage or coagulopathy. Interestingly, livedoid and necrotic lesions have been suggested to occur in elderly patients with severe systemic symptoms, likely representing the cutaneous manifestations associated with the highest rate of COVID‐19‐associated mortality.32

In our classification, we distinguished a specific purpuric pattern that was defined as ‘vasculitic’ in order to differentiate it from the petechial component of some exanthematous eruptions, as well as from livedo related to occlusive or microthrombotic vasculopathy. This pattern is likely to be extremely rare.31 33 In our experience, we observed a case of palpable purpura on the knees (Figure 1e) and another patient with purpuric and necrotic lesions of the lower legs, clinically resembling cutaneous leucocytoclastic vasculitis (unpublished data). In such cases, a vasculitic aetiology might be implicated, although histopathological data were unavailable and further studies are required. Interestingly, among the three vasculopathic lesions in the setting of severe COVID‐19 documented by Magro et al., the retiform purpura also showed prominent leucocytoclasia, suggesting the coexistence of a vasculitic process (Table 3).31

A peculiar cutaneous manifestation that is raising particular interest among dermatologists is represented by acral lesions resembling chilblains.8,29,30,33,36,37,38,39,40,41 These atypical presentations occurred in young patients confined at home during springtime, in the absence of cold exposure, comorbidities or other potential triggers. The rapid outbreak of perniosis‐like lesions, in parallel with the COVID‐19 pandemic and reflected in the ever‐growing number of reports of similar cases from various countries, has led to the hypothesis of a relationship between the disease and these clinical observations, although more data are needed to draw definite conclusions. In many cases, laboratory confirmation of the infection was not performed or gave negative results, and/or complete information about testing was not available. Nevertheless, various reports have suggested that such acro‐ischaemic chilblain‐like lesions predominantly affect children and young people, with an occasional history of systemic symptoms preceding cutaneous lesions.37,39,41

The acral eruption was frequently characterized by erythematous–violaceous papules and macules, with possible bullous evolution, or digital swelling.41 Feet were more frequently affected than hands. Nonacral sites were rarely involved and sometimes showed lesions with a targetoid appearance.39 41 In some cases, this was likely to represent true virus‐induced erythema multiforme, theoretically triggered by SARS‐CoV‐2 (personal observation).

In the study by Galván Casas et al., chilblain‐like lesions more often affected younger patients, lasted for approximately 13 days, occurred later in the course of COVID‐19 and were associated with less severe disease.32

In their series of 14 patients with acral perniosis‐like lesions, Recalcati et al. found no abnormalities of laboratory parameters (complete blood count, C‐reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase and D‐dimer; serology for Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, coxsackie and parvovirus B19).41 RT‐PCR test for SARS‐CoV‐2 from a swab was performed in very few cases, with negative results.

Fernandez‐Nieto et al. retrospectively reviewed the data of 132 patients with acral lesions (mean age 19·9 years) between 5 March and 15 April 2020.37 Two main clinical patterns of acute acro‐ischaemic lesions were recognized, resembling chilblains and erythema multiforme, respectively. Of these patients, 41% had close contact with people with COVID‐19 and 14·4% were clinically diagnosed with COVID‐19 (16 patients had skin lesions after a mean period of 9·2 days from the onset of COVID‐19 symptoms, and three patients simultaneously). None of the patients had pneumonia or any other complication. In 11 patients, an RT‐PCR assay was performed from a nasopharyngeal swab, after the appearance of skin lesions, and yielded positive results in only two patients.

It has been speculated that chilblain‐like lesions could represent late manifestations of COVID‐19 in young healthy patients.37 41 Future studies with serological examinations are necessary to corroborate this assumption. The lesions might result from a delayed immunological reaction against viral particles in asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic forms of COVID‐19.33 41 An increased type I interferon reaction has also been implicated.30 33

Histopathological studies and other laboratory assessments of skin samples

Histopathological examination of lesional skin was performed in a limited number of cases (Table 3). Inflammatory lesions generally showed nonspecific features.10,15,16,22,25,26,27,34 The histopathological picture of exanthematous eruptions was usually compatible with viral exanthem. The clinicopathological features found by Gianotti et al. were reminiscent of Grover disease in one patient and consistent with viral exanthem in the other two.27 In the latter two cases peculiar findings were noted, with early dermal microthromboses in one and signs suggestive of lymphocytic vasculitis in the other. Targetoid erythema multiforme‐like lesions of the elbows, observed in patients with concomitant acral perniosis‐like lesions, were characterized only by a mild superficial perivascular dermatitis.41

Even fewer data are available on the histopathology of vasculopathic lesions.30,31,41

Chilblain‐like lesions were characterized by lymphoid–lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the dermis, possibly extending to the hypodermis, and by a prevalent perivascular pattern.30 41 Signs of endothelial activation or plump endothelial cells in the venules surrounded by infiltrate were detected.30 41

The purpuric–livedoid skin lesions observed by Magro et al. in three critical patients with COVID‐19 showed signs of thrombotic microvascular damage.31 In addition, histopathological examination of the livedoid lesions revealed no signs of inflammation in one case and mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in another. In contrast, the retiform purpura of a third patient showed neutrophilia with prominent leucocytoclasia along with necrotic changes in the epidermis and adnexa. Immunohistochemical assessment demonstrated significant deposition of complement components within the skin microvasculature (Table 3). In two cases, a biopsy taken from the normal‐appearing skin showed microvascular deposits of C5b‐9 throughout the dermis.

Direct immunofluorescence studies were performed only in a case of erythematous–oedematous figurate plaques16 and in a patient with chilblain‐like acral lesions,30 providing negative results in both cases.

RT‐PCR for SARS‐CoV‐2 was very rarely performed on lesional skin samples, and again negative results were obtained.22 26

Conclusions

Different cutaneous manifestations have been described in the setting of COVID‐19. Although their pathogenic mechanisms are still unclear, hyperactive immune response, complement activation and microvascular injury have been implicated. The possible relationship between skin manifestations and COVID‐19 is an important aspect that deserves great attention and efforts in order to improve our understanding of such phenomena. On the other hand, the contributing roles of other infectious agents, patient comorbidities, immune status, concurrent treatments and other still undefined factors remain speculative.

The presence of cutaneous findings that can lead to suspicion of COVID‐19 and identify potentially contagious cases with an indolent course puts dermatologists in a relevant position. Furthermore, the role of COVID‐19‐associated skin manifestations as prognostic markers needs to be further deepened.

However, literature reports indicated a great heterogeneity in cutaneous manifestations, and their latency periods and associated extracutaneous symptoms. Moreover, difficulties are increased by the possible occurrence of skin lesions in paucisymptomatic or asymptomatic patients. Wide use of reliable serological assays will be important. Moreover, in future studies it would be useful to assess the viral load at different timepoints,47 and to detect viral RNA or particles within lesional skin.

Supplementary Material

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.

Contributor Information

A.V. Marzano, Dermatology Unit Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milan Italy; Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation Università degli Studi di Milano Milan Italy.

N. Cassano, Dermatology and Venereology Private Practice Bari and Barletta Italy

G. Genovese, Dermatology Unit Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milan Italy Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation Università degli Studi di Milano Milan Italy.

C. Moltrasio, Dermatology Unit Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milan Italy

G.A. Vena, Dermatology and Venereology Private Practice Bari and Barletta Italy

References

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:727–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehl S, Rabenau H, Berger A et al. Evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in returning travelers from Wuhan, China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1278–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joob B, Wiwanitkit V. COVID‐19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82:e177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamali Aghdam M, Jafari N, Eftekhari K. Novel coronavirus in a 15‐day‐old neonate with clinical signs of sepsis, a case report. Infect Dis (Lond) 2020; 52:427–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e212–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchonwanit P, Leerunyakul K, Kositkuljorn C. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: lessons learned from current evidence. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83:e57–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedou M, Carsuzaa F, Chary E et al. Comment on ‘Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective’ by Recalcati S. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16519] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, Ackerman M, Sancelme E et al. Urticarial eruption in COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e244–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Nieto D, Ortega‐Quijano D, Segurado‐Miravalles G et al. Comment on: Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a first perspective. Safety concerns of clinical images and skin biopsies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e252–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana‐Castanedo L, Feito‐Rodríguez M, Valero‐López I et al. Urticarial exanthem as early diagnostic clue for COVID‐19 infection. JAAD Case Rep 2020; 6:498–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Damme C, Berlingin E, Saussez S et al. Acute urticaria with pyrexia as the first manifestations of a COVID‐19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16523] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Lin J, Zhang Z et al. Alert for non‐respiratory symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients in epidemic period: a case report of familial cluster with three asymptomatic COVID‐19 patients. J Med Virol 2020; in press [ 10.1002/jmv.25776] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey‐Olivé M, Espiau M, Mercadal‐Hally M et al. Cutaneous manifestations in the current pandemic of coronavirus infection disease (COVID 2019). An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2020; in press [ 10.1016/j.anpede.2020.04.002] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera‐Oyola R, Koschitzky M, Printy R et al. Dermatologic findings in two patients with COVID‐19. JAAD Case Rep 2020; 6:537–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatore F, Macagno N, Mailhe M et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection presenting as a febrile rash. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16528] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najarian DJ. Morbilliform exanthem associated with COVID‐19. JAAD Case Rep 2020; 6:493–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt M, Koziatek C. A case of COVID‐19 pneumonia in a young male with full body rash as a presenting symptom. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 2020; 4:219–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avellana Moreno R, Villa E, Avellana Moreno V et al. Cutaneous manifestation of COVID‐19 in images: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16531] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese G, Colonna C, Marzano AV. Varicella‐like exanthem associated with COVID‐19 in an 8‐year‐old girl: a diagnostic clue? Pediatr Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/pde.14201] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahé A, Birckel E, Krieger S et al. A distinctive skin rash associated with coronavirus disease 2019? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e246–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahouach B, Harant S, Ullmer A et al. Cutaneous lesions in a patient with COVID‐19: are they related? Br J Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/bjd.19168] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estébanez A, Pérez‐Santiago L, Silva E et al. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: a new contribution. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e250–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez‐Cauhe J, Ortega‐Quijano D, Prieto‐Barrios M et al. Reply to ‘COVID‐19 can present with a rash and be mistaken for dengue’: petechial rash in a patient with COVID‐19 infection. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.016] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz‐Guimaraens B, Dominguez‐Santas M, Suarez‐Valle A et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1741] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Sohier P, Benghanem S et al. Digitate papulosquamous eruption associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1704] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianotti R, Veraldi S, Recalcati S et al. Cutaneous clinico‐pathological findings in three COVID‐19‐positive patients observed in the metropolitan area of Milan, Italy. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100:adv00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J et al. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID‐19: transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alramthan A, Aldaraji W. Two cases of COVID‐19 presenting in clinical picture resembling chilblains disease. First report from the Middle East. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/ced.14243] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolivras A, Dehavay F, Delplace D et al. Coronavirus (COVID‐19) infection‐induced chilblains: a case report with histopathologic findings. JAAD Case Rep 2020; 6:489–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID‐19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res 2020; in press [ 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/bjd.19163] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz JD, Duong T, Jachiet M et al. Vascular skin symptoms in COVID‐19: a French observational study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16544] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzano AV, Genovese G, Fabbrocini G et al. Varicella‐like exanthem as a specific COVID‐19‐associated skin manifestation: multicenter case series of 22 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83:280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammaro A, Adebanjo GAR, Parisella FR et al. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID‐19: the experiences of Barcelona and Rome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16530] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant‐Kels JM, Sloan B, Kantor J et al. Letter from the editors: big data and cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; in press [ 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.050] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez‐Nieto D, Jimenez‐Cauhe J, Suarez‐Valle A et al. Characterization of acute acral skin lesions in nonhospitalized patients: a case series of 132 patients during the COVID‐19 outbreak. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83:e61–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa N, Mendieta‐Eckert M, Fonda‐Pascual P, Aguirre T. Chilblain‐like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol 2020; 59:739–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo V, Neri I, Filippeschi C et al. Chilblain‐like lesions during COVID‐19 epidemic: a preliminary study on 63 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16526] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong TA, Velter C, Rybojad M et al. Did WhatsApp® reveal a new cutaneous COVID‐19 manifestation? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16534] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recalcati S, Barbagallo T, Frasin LA et al. Acral cutaneous lesions in the time of COVID‐19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; in press [ 10.1111/jdv.16533] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbalzano E, Casciaro M, Quartuccio S et al. Association between urticaria and virus infections: a systematic review. Allergy Asthma Proc 2016; 37:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrouche N, Grattan C. Childhood urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 12:485–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisondi P, Piaserico S, Conti A et al. Dermatologists and SARS‐CoV‐2: the impact of the pandemic on daily practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:1196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto MA. The Hospitalist. Skin manifestations are emerging in the coronavirus pandemic. Available at: https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/220183/coronavirus-updates/skin-manifestations-are-emerging-coronavirus-pandemic (last accessed 28 May 2020).

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M et al. [Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID‐2019 pneumonia and acro‐ischemia]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2020; 41:E006 (in Chinese). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su CJ, Lee CH. Viral exanthem in COVID‐19, a clinical enigma with biological significance. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e251–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.