Abstract

Infection and inflammation serve an important role in tumor development. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is a pivotal component of the innate and adaptive immune response during infection and inflammation. Programmed-death ligand 1 (PD-L1) is hypothesized as an important factor for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) immune escape. In the present study, the relationship between TLR4 and PD-L1, in addition to the associated molecular mechanism, were investigated. TLR4 and PD-L1 expression in lung cancer tissues were detected using immunohistochemistry, whilst overall patient survival was measured using the Kaplan-Meier method. The A549 cell line stimulated using lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was applied as the in vitro inflammatory NSCLC model. Associated factors were investigated using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and western blotting. Lung cancer tissues exhibited increased PD-L1 and TLR4 levels compared with those of adjacent para-cancerous tissues, where there was a positive correlation between TLR4 and PD-L1 expression. In addition, increased expression of these two proteins was found to be linked with poorer prognoses. Following the stimulation of A549 cells with LPS, TLR4 and PD-L1 expression levels were revealed to be upregulated in a dose-dependent manner, where the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways were found to be activated. Interestingly, in the presence of inhibitors of these two pathways aforementioned, upregulation of PD-L1 expression was only inhibited by the MEK inhibitor PD98059, which can inhibit ERK activity. These data suggested that the ERK signaling pathway is necessary for the TLR4/PD-L1 axis. In conclusion, data from the present study suggest that TLR4 and PD-L1 expression can serve as important prognostic factors for NSCLC, where TLR4 activation may induce PD-L1 expression through the ERK signaling pathway.

Keywords: toll-like receptor 4, programmed death-ligand 1, non-small cell lung cancer, inflammation, initiation

Introduction

According to data from the global cancer statistics in 2018, the most common and malignant form of cancer is that of lung cancer, which accounts for 11.6% of all cancers and 18.4% of all cancer-associated mortality globally (1). In China, lung cancer is the most prominent cause of mortality associate with cancer in both males and females, with mortality rates of 52.47 and 26.29 per 100,000, respectively (2). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases make up ~85% of all lung cancer cases, with ≤40% of cases not being identified until advanced stages (III-IV), where treatment options and the probability of survival become limited (3).

In total, ~15% cancer cases have recently been suggested to be associated with an infectious origin, accounting for 1.2 million cases annually (4). Previous clinical and experimental findings suggest that chronic infection and inflammation are closely linked with lung cancer (5-7). Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are key receptors that can detect and then respond to infections through the innate immune and inflammatory response mechanisms. TLR4 was the first identified human toll homolog family of proteins that can be activated by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and induces the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines among others to combat pathogenic infections (8). Although recent studies found TLR4 to be expressed in lung cancer cells and tissues (9,10), the role of TLR4 in lung cancer remain controversial. The programmed-death 1 receptor/PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway has been reported to be a key inhibitory mechanism in lung cancer cells, the activation of which leads to effector T cell exhaustion and immune escape (11,12). Previous studies have demonstrated that PD-L1 expression could be induced by TLR4 in macrophages and colonic stromal cells (13,14), though the functional relationship between PD-L1 and TLR4 in lung cancer remains elusive.

In the present study, PD-L1 and TLR4 expression were measured in lung cancer tissues, where TLR4 and PD-L1 expression were found to be upregulated in lung cancer tissues, with a positive correlation being observed between the expression levels of these two proteins. In addition, the mechanism in which TLR4 influenced the expression of PD-L1 and associated signaling pathways in the A549 lung cancer cell line was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Patients

The Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University approved the present study (Nanchang, China). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. All patients were pathologically diagnosed as NSCLC and had not undergone any radio- or chemotherapy and should have a complete set of clinicopathological and follow-up data. Patients with other malignant tumors and diseases that may affect survival, including diabetes and heart failure were excluded. In total, 60 patients that underwent pulmonary resection from thoracic surgery department of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University were enrolled between January and December 2010. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis to mortality or the final follow-up. Table I highlights the clinicopathological parameters from all enrolled patients.

Table I.

Association between PD-L1 and TLR-4 expression levels and the clinicopathological parameters of patients with non-small cell lung cancer.

| Parameters | Cases | PD-L1

|

% | P-valuea | TLR-4

|

% | P-valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | − | ||||||

| Gender | 0.791 | 0.071 | |||||||

| Male | 48 | 30 | 18 | 62.5 | 22 | 26 | 45.8 | ||

| Female | 12 | 7 | 5 | 58.3 | 9 | 3 | 75 | ||

| Age (years) | 0.559 | 0.123 | |||||||

| >60 | 21 | 14 | 7 | 66.7 | 8 | 13 | 38.1 | ||

| ≤60 | 39 | 23 | 16 | 59 | 23 | 16 | 59.0 | ||

| Histology type | 0.729 | 0.010 | |||||||

| SCC | 27 | 16 | 11 | 59.3 | 9 | 18 | 33.3 | ||

| ADC | 33 | 21 | 12 | 63.6 | 22 | 10 | 69.7 | ||

| Grade | 0.602 | 0.866 | |||||||

| High-middle | 42 | 25 | 17 | 35.7 | 22 | 20 | 52.4 | ||

| Low | 18 | 12 | 6 | 66.7 | 9 | 9 | 50.0 | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.791 | 0.796 | |||||||

| Negative | 30 | 18 | 12 | 60.0 | 15 | 15 | 50 | ||

| Positive | 30 | 19 | 11 | 63.3 | 16 | 14 | 53.3 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.453 | 0.715 | |||||||

| ≤3 | 20 | 11 | 9 | 55.0 | 11 | 9 | 55.0 | ||

| >3 | 40 | 26 | 14 | 65.0 | 20 | 20 | 50.0 | ||

| TNM stage | 0.090 | 0.025 | |||||||

| I + II | 39 | 21 | 18 | 53.8 | 16 | 23 | 41 | ||

| III | 21 | 16 | 5 | 76.2 | 15 | 6 | 71.4 | ||

PD-L1+ vs. PD-L1−;

TLR4+ vs. TLR4−. Pearson's χ2 test was used to analyze the data above. PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; ADC, adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

A total of 60 NSCLC samples and 20 matched adjacent para-cancerous tissues (>2 cm from the edge of tumor tissue) were collected in this study. Once resected, tissues were fixed in 10% formalin overnight at room temperature (RT), embedded in paraffin and cut into 4-µm thick tissue sections. Polyclonal rabbit anti-TLR4 (1:100, cat. no. ab13556; Abcam), and polyclonal rabbit anti-PD-L1 (1:100, cat. no. 13684; Cell signaling Technologies, Inc.) primary antibodies were used in the present study for IHC. Matched adjacent para-carcinoma tissues served as controls. Briefly, the samples were first heated at 70°C for 20 min prior to de-paraffinization in xylene, followed by rehydration with a descending ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed at 100°C and in citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) for 2 min and permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 at RT for 20 min, following which 0.3% hydrogen peroxide was added to block the activity endogenous peroxidase for 10 min at RT. The sections were then blocked with 5% BSA (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at RT before the tissue sections were incubated with the primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Samples were then washed with PBS before the addition of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200; cat. no. G1213; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C for 30 min. After washing, the tissues were then treated with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (MXB Biotechnologies) for chromogenic development. Nuclei were next stained using hematoxylin (30 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 1 min at RT before the sections were then added to cover-slips and assessed by light microscopy (magnification, ×100; Olympus Corporation), with all sections assessed by two pathologists independently in a blinded manner. Sections were deemed to be PD-L1 or TLR4 positive based on the presence of cell membrane or cytoplasmic staining, with a semi-quantitative system applied for IHC scoring. Five random areas with typical staining were identified, with 100 cells were assessed per area to determine the strength and frequency of staining. Staining strength was determined based on the following color scale: i) Negative, 0; ii) light brown, 1; iii) brown, 2; and iv) dark brown, 3. The frequency of cells staining positive for the indicated antigen was determined based on the following scale: i) ≤5%, 0; ii) 6-25%, 1; iii) 26-50%, 2; iv) 51-75%, 3; and v) 76-100%, 4. These two scores were then multiplied together to yield a final staining score, with scores ≤1 being deemed negative (−), whereas those ≥1 were considered positive (+).

Cell culture

The A549 cell line was a gift from Dr. Jianbin Wang, Translation Medical Department of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China). RPMI-1640 (Biological Industries) supplemented with 10% newborn bovine serum (Biological Industries) and penicillin/streptomycin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to culture cells at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Confluent cells were collected using trypsin/EDTA for 3 min, after which cells (3×105 cells/ml) were plated into six-well plates (1 ml/well) for LPS treatment. LPS (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was used to treat the cells (0.5, 1 and 2 µg/ml) for a range of time points (15 and 30 min, or 1, 2, 4 or 24 h) at 37°C. PD98059 (cat. no. M1822; Abmole Bioscience Inc.) and LY294002 (cat. no. 9901; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) were utilized as inhibitors for MEK and AKT, respectively. A549 cells were pretreated with PD98059 or LY294002 at different concentrations for 1 h at 37°C, following which LPS (1 µg/ml) was added into the medium.

Western blotting

RIPA buffer (Applygen Technologies, Inc.) was used to lyse the A549 cells for protein extraction, following which a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.) was used to quantify protein concentration. A total of 25 µg protein of each sample was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes, which were then blocked for 1 h with 5% BSA (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at RT before being probed overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-TLR4 (1:500; cat. no. ab13556; Abcam), anti-PD-L1 (cat. no. 13684; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-phosphorylated (p)-p44/42MAPK (1:1,000; cat. no. 9101; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-p44/42MAPK (1:1,000; cat. no. 4695; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-Akt (1:1,000; cat. no. 4691; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-p-Akt (Ser473; 1:2,000; cat. no. 4060; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and anti-β-tubulin (1:2,000; cat. no. TA506805; OriGene Technologies, Inc.). The membranes were then washed three times and probed again with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000: cat. no. SE131; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. SE134; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at RT for 1 h. Electro-chemiluminescence Plus supersensitive luminescent solution (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was used for protein detection, following which the Image J software (v1.43j; National Institutes of Health) was used to perform densitometric analysis using β-tubulin as a loading control for normalization.

Reverse transcription-quantitative-PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNAsimple Total RNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) was used for RNA isolation according to manufacturer's protocols. Subsequently, reverse transcription was performed using FastQuant RT kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to manufacturer's protocols. The temperature protocol was 42°C for 15 min followed by 95°C for 3 min for cDNA synthesis. SuperReal PreMix Plus (SYBR Green; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) was then used for qPCR in an ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using the following thermocycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. Sequences of the primers were as follows: PD-L1 forward, 5′-GCC GAC TAC AAG CGA ATT AC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCT CAG TGT GCT GGT CAC AT-3′ and β-actin forward, 5′-CGG GAA ATC GTG CGT GAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TAG AAG CAT TTG CGG TGG-3′. The 2−ΔΔCq method was utilized when assessing relative expression (15).

Statistical analysis

SPSS statistical software (version 19.0; IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) were utilized when performing statistical assessments. All experiments were repeated 3 times and data were presented as the mean ± SD or SEM. Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used for correlation analyzes. χ2-test was used for comparisons between categorical variables and the Kaplan-Meier method was used when assessing overall survival based on the IHC scores with log-rank tests used for comparisons of significance. A Cox proportional hazard model was applied for multivariate analyses of the independent factors associated with survival. Statistical comparisons between >2 groups were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

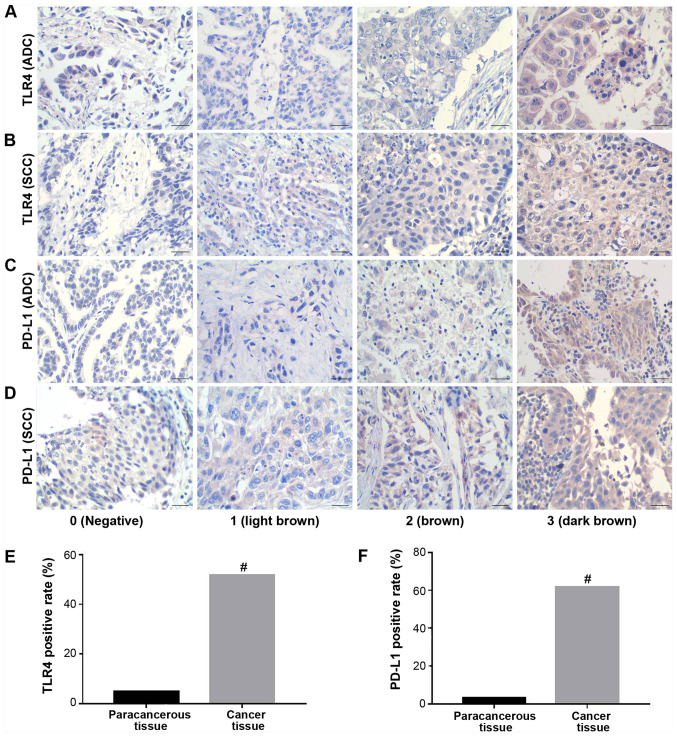

TLR4 and PD-L1 expression are both increased in NSCLC tissues, which exhibit positive association with each other

To assess TLR4 and PD-L1 expression in NSCLC tissues, IHC was performed in 60 cases of NSCLC tissues and 20 matched adjacent para-cancerous tissues. Positive TLR4 and PD-L1 staining was mainly observed at the membrane and cytoplasm of the cancerous tissues (Figs. 1 and S1). The rate of TLR4-positive expression was observed in 31/60 (51.7%) NSCLC tissues, compared with 1/20 (5%) observed in adjacent para-cancerous tissues, which was found to be significant (P<0.001; Table SI). The rate of PD-L1-positive expression was observed in 37/60 (61.7%) NSCLC tissues and 2/20 (10%) adjacent para-cancerous tissues, with the difference found to be significant (P<0.001; Table SI). Both TLR4 and PD-L1 positive rates were found to be significantly higher in NSCLC tissues compared with those in para-cancerous tissues (Fig. 1). A total of 24 tissues exhibited positive staining for both TLR4 and PD-L1, whilst 16 tissues were tested negative for both TLR4 and PD-L1 staining among the 60 lung cancer tissues (Table SII). χ2-test revealed a positive association between the incidence of positive TLR4 and that of positive PD-L1 expression based on the IHC scores (χ=6.733, P=0.0095).

Figure 1.

Positive TLR4 and PD-L1 expression are more readily observed in lung cancer tissues. (A-D) Representative images of (A) lung adenocarcinoma and (B) lung squamous cell carcinoma tissues exhibiting TLR4 staining. Representative images of (C) lung adenocarcinoma and (D) lung squamous cell carcinoma tissues exhibiting PD-L1 staining. The number of tissues staining positive for (E) TLR4 and (F) PD-L1 expression in cancer and para-cancerous tissues. Scale bar, 50 µm. #P<0.01 vs. para-cancerous tissue. TLR4, toll-like receptor; PD-L1, programmed-death ligand 1; ADC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

To assess the clinical relevance of TLR4 and PD-L1, the association between the clinicopathological characteristics, including age, gender, histological type, stages of pathological differentiation, lymphatic invasion, tumor size and TNM stage, and the expression of TLR4/PD-L1 was analyzed in Table I. TLR4 expression was found to associate with the histological type (P=0.01) and TNM stages (P=0.025) but PD-L1 expression did not associate with any of the clinicopathological parameters tested.

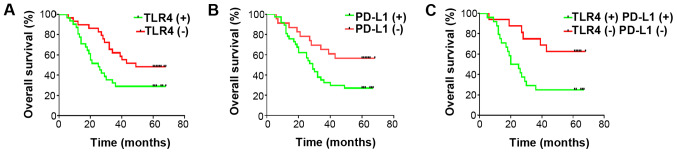

Elevated TLR4 and PD-L1 correspond to poorer prognoses in patients with NSCLC

The average follow-up time for the patients was 38.33±2.814 months (range, 5-68 months), where 37 died and 23 surviving to the final follow-up on 31st December, 2015. The 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rates for these individuals were found to be 88, 45 and 38.3%, respectively. Patients with positive TLR4 and/or PD-L1 staining were found to associate significantly with lower OS compared with those with negative staining at each time point (Fig. 2). Although it was found by univariate analysis that the OS rate was significantly associated with lymphatic invasion (P=0.01), tumor stage (P=0.01), TLR4 (P=0.02) and PD-L1 expression (P=0.01), subsequent multivariate analysis did not demonstrate these to be independent prognostic factors (Table II).

Figure 2.

OS rates of non-small cell lung cancer according to TLR4 and PD-L1 expression levels. (A) Positive TLR4 staining is associated with decreased OS (P=0.0143). (B) Positive PD-L1 staining is associated with decreased OS (P=0.0353). (C) Positive combined PD-L1 and TLR4 staining is associated poorer OS (P=0.0091). OS, overall survival; TLR4, toll-like receptor; PD-L1, programmed-death ligand 1.

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the clinicopathologic factors in patients with NSCLC with respect to overall survival.

| Parameters | Cases | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survive time | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Gender | 0.609 | ||||

| Male | 48 | 36.06±3.29 | |||

| Female | 12 | 35.42±5.16 | |||

| Age (years) | 0.845 | ||||

| >60 | 21 | 39.1±4.75 | |||

| ≤60 | 39 | 37.92±3.54 | |||

| Histology type | 0.293 | ||||

| SCC | 27 | 41.63±4.48 | |||

| ADC | 33 | 35.64±3.57 | |||

| Grade | 0.177 | ||||

| High-middle | 42 | 40.83±3.36 | |||

| Low | 18 | 32.5±5.03 | |||

| Lymphatic invasion | 0.013 | ||||

| Negative | 30 | 31.47±3.73 | 0.557 (0.246-1.258) | 0.159 | |

| Positive | 30 | 45.2±3.88 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.355 | ||||

| ≤3 | 20 | 42.05±4.79 | |||

| >3 | 40 | 36.48±3.48 | |||

| TNM stage | 0.009 | ||||

| I +II | 39 | 43.67±3.33 | 1.24 (0.538-2.86) | 0.614 | |

| III | 21 | 28.43±4.47 | |||

| PD-L1 | 0.023 | ||||

| Positive | 37 | 33.32±3.36 | 0.663 (0.31-1.422) | 0.291 | |

| Negative | 23 | 46.39±4.57 | |||

| TLR4 | 0.014 | ||||

| Positive | 31 | 31.71±3.85 | 0.591 (0.298-1.17) | 0.131 | |

| Negative | 29 | 45.41±3.75 | |||

Overall survival time was presented as mean ± SEM and was determined by the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test. Multivariable analysis of the independent factors was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; ADC, adenocarcinoma; HR, hazards ratio; CI, confidence interval.

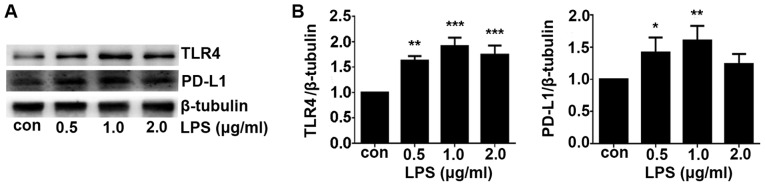

LPS induces TLR4 and PD-L1 expression in a dose-dependent manner

LPS is a potent agonist for TLR4 (9). In the present study, A549 cells were treated with different concentrations (0.5, 1 and 2 µg/ml) of LPS for 24 h. TLR4 expression was demonstrated to be significantly increased by LPS treatment in a dose-dependent manner compared with that in the control group, which peaked at 1.0 µg/ml (Fig. 3). PD-L1 expression was also increased after LPS treatment compared with that in control group with the optimal concentration found to be 1.0 µg/ml (Fig. 3). A higher concentration of LPS (2.0 µg/ml) was not able to upregulate the TLR4 and PD-L1 expression further. Therefore, 1.0 µg/ml was used as the concentration for subsequent LPS stimulation experiments.

Figure 3.

LPS treatment increases TLR-4 and PD-L1 expression in a dose-dependent manner. A549 cells were subjected to 0.5, 1, 2 µg/ml LPS for 24 h prior to western blotting. (A) Representative images of the TLR-4 and PD-L1 blots. (B) Quantification of the TLR4 and PD-L1 expression levels shown in (A). Data are shown as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. con. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; Con, control; TLR4, toll-like receptor; PD-L1, programmed-death ligand 1.

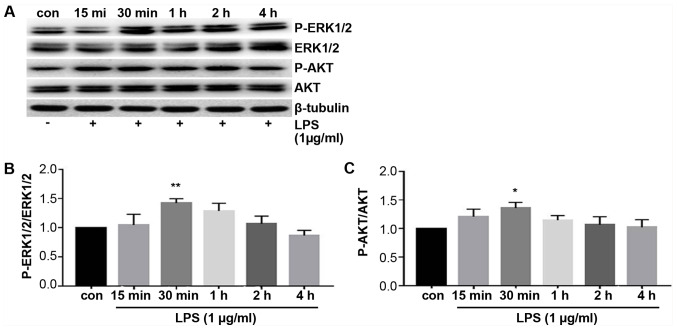

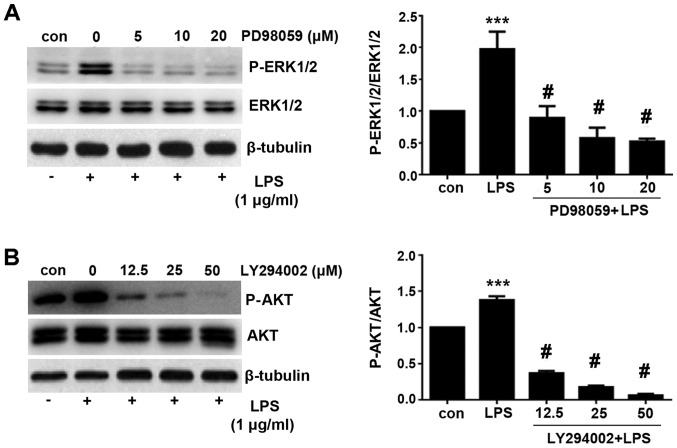

ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway are activated by LPS stimulation

To explore the mechanism underlying the TLR4 and PD-L1 upregulation by LPS treatment, expression of proteins associated with the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway were measured using western blotting. ERK and AKT phosphorylation were found to be significantly increased following treatment with LPS compared with those in control cells (Fig. 4). The levels of phosphorylation peaked at 30 min after LPS treatment, which then decreased thereafter (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway was activated by LPS stimulation.

Figure 4.

ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway are activated by LPS stimulation. A549 cells were treated with LPS (1 µg/ml) for 15 and 30 min or 1, 2 and 4 h prior to western blotting. (A) Representative images of the blots showing ERK1/2 and AKT phosphorylation. Semi-quantitative densitometric analysis measuring relative (B) p-ERK1/2 and (C) p-AKT levels following treatment with/without LPS. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. con. LPS, lipopolysaccharides; Con, control.

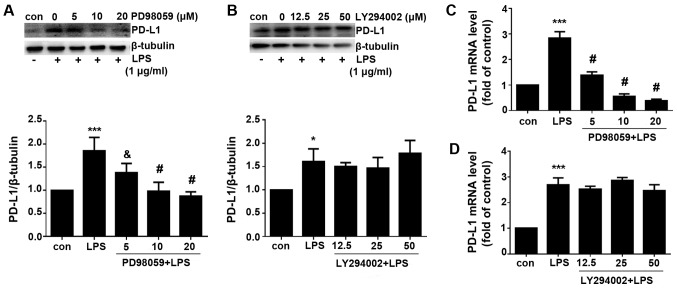

LPS-induced PD-L1 expression is mediated via ERK signaling but not the PI3K/AKT pathway

Since both ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway were activated by LPS treatment, pharmacological inhibitors of the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway applied in the present study to investigate which pathway is necessary for the induction of PD-L1 expression. PD98059 is a selective inhibitor of MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK), which binds to the inactive form of MEK to prevent the activation of MEK1 and MEK2 by upstream kinases (16). PD98059 was therefore used to inhibit ERK activity. By contrast, LY294002 is a broad-spectrum PI3K inhibitor that has been demonstrated to block PI3K-dependent AKT phosphorylation and kinase activity (17). As shown in Fig. 5, PD98059 significantly inhibited ERK phosphorylation, whilst LY294002 significantly inhibited AKT phosphorylation compared with cells treated with LPS alone.

Figure 5.

LPS-induced ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling activation can be blocked by their corresponding pharmacological inhibitors. A549 cells were first treated with 1 µg/ml LPS and the MEK inhibitor PD98059 or PI3K inhibitor LY294002 at the indicated concentrations prior to western blotting analysis. (A) Representative images of the blots showing ERK1/2 phosphorylation and corresponding semi-quantitative densitometric analysis showing relative p-ERK1/2 levels following respective treatments. (B) Representative images of the blots showing AKT phosphorylation and corresponding semi-quantitative densitometric analysis showing relative p-AKT levels following respective treatments. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. ***P<0.001 vs. con and #P<0.05 vs. LPS. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; con, control.

PD-L1 expression was subsequently measured. Western blotting and RT-qPCR analysis revealed that the LPS-induced PD-L1 upregulation was significantly reversed by the MEK inhibitor PD98059 but not by the PI3K inhibitor PD294002 on both protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 6). These data indicated that LPS induced PD-L1 upregulation via ERK signaling pathway.

Figure 6.

LPS-induced PD-L1 upregulation is inhibited by the MEK inhibitor but not PI3K inhibitor. A549 cells were treated with LPS and the MEK inhibitor PD98059 or the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 at their indicated concentration prior to western blotting. (A) Representative image of the blots of PD-L1 and corresponding semi-quantitative densitometric analysis following treatment with LPS and/or PD98059. (B) Representative image of the blots of PD-L1 and cor-responding semi-quantitative densitometric analysis following treatment with LPS and/or LY294002. (C) Measurement of PD-L1 mRNA expression following treatment with (C) LPS and/or PD98059. (D) Measurement of PD-L1 mRNA expression following treatment with LPS and/or LY294002. Data are presented as the means ± SD. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 vs. con. &P<0.05 and #P<0.0.001 vs. LPS. LPS, lipopolysaccharides; Con, control; PD-L1, programmed-death ligand 1.

Discussion

Lung cancer ranks number one in the number of mortalities associated with cancer in men and second in women, with 1.8 million newly diagnosed cases and 1.6 million deaths resulting from this disease globally each year (18). In total, ~80-85% lung cancer cases are of the NSCLC type. Since clinical manifestations and symptoms are nonspecific, the majority of patients with NSCLC are diagnosed after the occurrence of metastasis (19), greatly diminishing the efficacy of surgery. Although the introduction of targeted therapies such as immunotherapy have improved survival to a certain degree, the overall survival rate remains unsatisfactory (19-21). Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial in preventing tumor progression and reducing the mortality of patients.

There is accumulating evidence demonstrating that cancer is associated with infectious agents and inflammation (4,22-26). It is estimated that ≤20% of all cancers are preceded by inflammation as a result of pathogenic infection, with hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus-induced hepatitis, gastric cancer and H. pylori-induced gastritis, cervical cancer and human papillomavirus infection among the well documented examples (27-29). Denholm et al (30) previously found the incidence of lung cancer to be significantly associated with chronic bronchitis and emphysema, with the presence of both conditions associating more strongly with lung cancer compared with chronic bronchitis alone. Interestingly, a growing body of evidence are supporting an association between H. pylori infection with lung cancer (31). However, the mechanisms through which inflammation promotes cancer are not fully understood.

TLR4 is a key mediator of innate immunity, which specifically recognizes conserved motifs expressed by pathogens to mediate immune responses (32). Huang et al (33) previously demonstrated that TLR4 is expressed by many types of cancer cells, including colon, breast, prostate and lung cancer cells. Following TLR4 activation, tumor cells can synthesize a number of factors, including interleukin-6, interleukin-12 and PD-L1, which is a co-stimulator of T cell function. Interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1 expressed on cytolytic T cells leads to the negative co-stimulation of TCR signaling, resulting in effector T cell exhaustion (34). PD1/PD-L1-induced immune evasion by tumor cells is an important mechanism for NSCLC, the blockade of which has improved the survival of a small percentage of patients with NSCLC (35,36). However, the majority of patients showed little to no response or acquire resistance during treatment (37).

A number of studies have previously reported that TLR4 and PD-L1 were aberrantly expressed in cancer tissues or cell lines (13,14,38-40). PD-L1 expression can be induced by extracellular vesicles from melanoma cells via TLR4 signaling (41). Both TLR4 and PD-L1 were upregulated in ~50% of peripheral T-cell lymphomas, which were found to be associated with poor prognoses (42). Therefore, in the present study it was hypothesized that TLR4-induced PD-L1 expression could be the mechanism underlying lung cancer progression. TLR4 and PD-L1 expression levels were first measured in NSCLC tissues, which demonstrated that both TLR4 and PD-L1 were significantly more prominent in NSCLC tissues compared with those in para-cancerous tissues. In addition, a statistically significant positive correlation was observed between TLR4 and PD-L1 expression, whilst overall survival was also revealed to associate significantly with TLR4 and PD-L1 expression. However, none were demonstrated to be independent prognostic factors for NSCLC. Wang et al (40) reported different findings, who determined that higher expression of TLR4 in lung cancer tissues was significantly associated with poorer OS and disease-free survival, where TLR4 was found to be a independent prognostic factor for NSCLC through multivariate analysis. There are several studies that revealed contradictory results. Wei et al (43) assessed the relevance of serum levels of soluble TLR4 (sTLR4) in NSCLC, who found lower sTLR4 levels to be indicative of reduced survival among patients with early-stage NSCLC that had recently undergone tumor resection surgery. Another previous study by Bauer et al (10) also supported the notion that increasing TLR4 expression may improve outcomes, but no significance was found. A possible explanation for this inconsistency may be due to different sample sizes, whilst another explanation could be that the complex formed by sTLR4 and the adaptor protein myeloid differentiation factor-2 (MD-2) may attenuate TLR4-mediated signaling, since TLR4 requires MD-2 to respond efficiently to LPS (44,45).

Although the present study didn't uncover a prognostic value of TLR4 and PD-L1. It is believed that inflammation can lead to carcinogenesis (46,47). TLR4 is a component of the innate and adaptive immune response to infection and inflammation, whilst PD-L1 also has a pivotal role in immune escape by lung cancer. Therefore, the relationship between TLR4 and PD-L1 was explored further in vitro in the present study, using LPS as the inflammatory stimulator. TLR4 activation by LPS was found to induce PD-L1 expression in A549 cells. LPS stimulation can induce TLR4 pathway activation, in turn activating the NF-κB, MAPKs, p38, ERK and PI3K⁄AKT signaling pathways (48,49). Data from the present study confirmed that the ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways were activated by LPS treatment. By using the MEK inhibitor to inhibit ERK activity and PI3K inhibitor to inhibit AKT activity respectively, it was revealed that LPS-induced PD-L1 upregulation was dependent on the TLR4/ERK but not the TLR4/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. These results are consistent with those previously reported by Qian et al (38) and Wang et al (39) on bladder cancer tissues and cells.

A number of limitations remain associated with the present study. The cancer tissue sample size obtained for IHC is relatively small, whilst the in vitro part of the present study is restricted to A549 cell line. Although the underlying mechanism between TLR4 and PD-L1 was mainly focused on ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in the present study, other signaling pathways downstream of TLR4 may also be involved in the process, such as the NF-κB and interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) pathway. The NF-κB pathway activation has been demonstrated to contribute to PD-L1 upregulation in LPS-treated gastric cancer cells (50), but whether the same phenomenon exists in lung cancer cells remain poorly understood and require further investigations.

Despite its limitations, the present study contributed to the understanding of the functional relationship between TLR4 and PD-L1 in NSCLC. TLR4 and PD-L1 expression are found to be significantly associated with OS, whilst TLR4 can induce PD-L1 expression through the ERK signaling pathway following stimulation by LPS. Taken together, during conditions of chronic inflammation, TLR4 induced PD-L1 expression may contribute to NSCLC initiation.

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of pathologists, Dr Shanshan Wang and Dr Luxia Tu, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China). The authors would also like to thank Dr Jianbin Wang, Translation Medical Department of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China), for the gift of the A549 cell line.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Jiangxi Provincial Education Department Key Project (grant no. GJJ17024), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Science and Technology Department (grant no. 20181BAB205058) and Project of Jiangxi Provincial Health Department (grant no. 20185144).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

GW contributed to the design of the study and editing of the manuscript. XK, PL, CZ processed the experiments. XK also responsible for manuscript writing. YZ was responsible for collecting and organizing the clinical data. HH was responsible for following up the patients and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China) approved the present study. All patients gave informed consents to participate.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, He J. Annual report on status of cancer in China, 2011. Chin J Cancer Res. 2015;27:2–12. doi: 10.1186/s40880-015-0001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bocanegra A, Fernandez-Hinojal G, Zuazo-Ibarra M, Arasanz H, Garcia-Granda MJ, Hernandez C, Ibañez M, Hernandez-Marin B, Martinez-Aguillo M, Lecumberri MJ, et al. PD-L1 expression in systemic immune cell populations as a potential predictive biomarker of responses to PD-L1/PD-1 blockade therapy in lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:E1631. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Muñoz N, Ferlay J. Cancer and infection: Estimates of the attributable fraction in 1990. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:387–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomes M, Teixeira AL, Coelho A, Araujo A, Medeiros R. The role of inflammation in lung cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;816:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houghton AM, Mouded M, Shapiro SD. Common origins of lung cancer and COPD. Nat Med. 2008;14:1023–1024. doi: 10.1038/nm1008-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin TY, Huang WY, Lin JC, Lin CL, Sung FC, Kao CH, Yeh JJ. Increased lung cancer risk among patients with pneumococcal pneumonia: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Lung. 2014;192:159–165. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9523-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Nardo D. Toll-like receptors: Activation, signalling and transcriptional modulation. Cytokine. 2015;74:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He W, Liu Q, Wang L, Chen W, Li N, Cao X. TLR4 signaling promotes immune escape of human lung cancer cells by inducing immunosuppressive cytokines and apoptosis resistance. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2850–2859. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer AK, Upham BL, Rondini EA, Tennis MA, Velmuragan K, Wiese D. Toll-like receptor expression in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: Potential prognostic indicators of disease. Oncotarget. 2017;8:91860–91875. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He J, Hu Y, Hu M, Li B. Development of PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in tumor immune microenvironment and treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13110. doi: 10.1038/srep13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DB, Rioth MJ, Horn L. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in NSCLC. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014;15:658–669. doi: 10.1007/s11864-014-0305-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loke P, Allison JP. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are differentially regulated by Th1 and Th2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5336–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931259100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beswick EJ, Johnson JR, Saada JI, Humen M, House J, Dann S, Qiu S, Brasier AR, Powell DW, Reyes VE, Pinchuk IV. TLR4 activation enhances the PD-L1-mediated tolerogenic capacity of colonic CD90+ stromal cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:2218–2229. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ, Saltiel AR. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)- 8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz AG, Cote ML. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;893:21–41. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24223-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu J, Luo J, Li Y, Jia M, Wang Y, Huang Y, Ke S. HMGB1 induces human non-small cell lung cancer cell motility by activating integrin αvβ3/FAK through TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;480:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong J, Li B, Lin D, Zhou Q, Huang D. Advances in targeted therapy and immunotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer based on accurate molecular typing. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:230. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boeri M, Milione M, Proto C, Signorelli D, Lo Russo G, Galeone C, Verri C, Mensah M, Centonze G, Martinetti A, et al. Circulating miRNAs and PD-L1 tumor expression are associated with survival in advanced NSCLC patients treated with immunotherapy: A prospective study. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2166–2173. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oikonomopoulou K, Brinc D, Kyriacou K, Diamandis EP. Infection and cancer: Revaluation of the hygiene hypothesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2834–2841. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacqueline C, Tasiemski A, Sorci G, Ujvari B, Maachi F, Missé D, Renaud F, Ewald P, Thomas F, Roche B. Infections and cancer: The 'fifty shades of immunity' hypothesis. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:257. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Islami F, Chen W, Yu XQ, Lortet-Tieulent J, Zheng R, Flanders WD, Xia C, Thun MJ, Gapstur SM, Ezzati M, Jemal A. Cancer deaths and cases attributable to lifestyle factors and infections in China, 2013. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2567–2574. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hattori N, Ushijima T. Epigenetic impact of infection on carcinogenesis: Mechanisms and applications. Genome Med. 2016;8:10. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ewald PW, Swain Ewald HA. Infection and cancer in multi-cellular organisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370:20140224. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francescone R, Hou V, Grivennikov SI. Microbiome, inflammation, and cancer. Cancer J. 2014;20:181–189. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wardak S. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. Med Dosw Mikrobiol. 2016;68:73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Denholm R, Schüz J, Straif K, Stücker I, Jöckel KH, Brenner DR, De Matteis S, Boffetta P, Guida F, Brüske I, et al. Is previous respiratory disease a risk factor for lung cancer? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:549–559. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0338OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.González I, Araya P, Rojas A. Helicobacter pylori infection and lung cancer: New insights and future challenges. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2018;21:658–662. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2018.09.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ve T, Vajjhala PR, Hedger A, Croll T, DiMaio F, Horsefield S, Yu X, Lavrencic P, Hassan Z, Morgan GP, et al. Structural basis of TIR-domain-assembly formation in MAL- and MyD88-dependent TLR4 signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24:743–751. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang B, Zhao J, Li H, He KL, Chen Y, Chen SH, Mayer L, Unkeless JC, Xiong H. Toll-like receptors on tumor cells facilitate evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5009–5014. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hui E, Cheung J, Zhu J, Su X, Taylor MJ, Wallweber HA, Sasmal DK, Huang J, Kim JM, Mellman I, Vale RD. T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1-mediated inhibition. Science. 2017;355:1428–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, Herter-Sprie GS, Buczkowski KA, Richards WG, Gandhi L, Redig AJ, Rodig SJ, Asahina H, et al. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10501. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Konen JM, Rodriguez BL, Fradette JJ, Gibson L, Davis D, Minelli R, Peoples MD, Kovacs J, Carugo A, Bristow C, et al. Ntrk1 promotes resistance to PD-1 checkpoint blockade in mesenchymal Kras/p53 mutant lung cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:E462. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian Y, Deng J, Geng L, Xie H, Jiang G, Zhou L, Wang Y, Yin S, Feng X, Liu J, et al. TLR4 signaling induces B7-H1 expression through MAPK pathways in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:816–821. doi: 10.1080/07357900801941852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang YH, Cao YW, Yang XC, Niu HT, Sun LJ, Wang XS, Liu J. Effect of TLR4 and B7-H1 on immune escape of urothelial bladder cancer and its clinical significance. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:1321–1326. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.3.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang K, Wang J, Wei F, Zhao N, Yang F, Ren X. Expression of TLR4 in non-small cell lung cancer is associated with PD-L1 and poor prognosis in patients receiving pulmonectomy. Front Immunol. 2017;8:456. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleming V, Hu X, Weller C, Weber R, Groth C, Riester Z, Hüser L, Sun Q, Nagibin V, Kirschning C, et al. Melanoma extracellular vesicles generate immunosuppressive myeloid cells by upregulating PD-L1 via TLR4 SIgnaling. Cancer Res. 2019;79:4715–4728. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao S, Sun M, Meng H, Ji H, Liu Y, Zhang M, Li H, Li P, Zhang Y, Zhang Q. TLR4 expression correlated with PD-L1 expression indicates a poor prognosis in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:4743–4756. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S203156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei F, Yang F, Li J, Zheng Y, Yu W, Yang L, Ren X. Soluble Toll-like receptor 4 is a potential serum biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:40106–40114. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hyakushima N, Mitsuzawa H, Nishitani C, Sano H, Kuronuma K, Konishi M, Himi T, Miyake K, Kuroki Y. Interaction of soluble form of recombinant extracellular TLR4 domain with MD-2 enables lipopolysaccharide binding and attenuates TLR4-mediated signaling. J Immunol. 2004;173:6949–6954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Fukudome K, Miyake K, Kimoto M. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1777–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuper H, Adami HO, Trichopoulos D. Infections as a major preventable cause of human cancer. J Intern Med. 2000;248:171–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen CY, Kao CL, Liu CM. The Cancer prevention, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidation of bioactive phytochemicals targeting the TLR4 signaling pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:E2729. doi: 10.3390/ijms19092729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen CW, Chen CC, Jian CY, Lin PH, Chou JC, Teng HS, Hu S, Lieu FK, Wang PS, Wang SW. Attenuation of exercise effect on inflammatory responses via novel role of TLR4/PI3K/Akt signaling in rat splenocytes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2016;121:870–877. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00393.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Xia JQ, Zhu FS, Xi ZH, Pan CY, Gu LM, Tian YZ. LPS promotes the expression of PD-L1 in gastric cancer cells through NF-κB activation. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:9997–10004. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.