Abstract

Introduction

Frailty is highly prevalent in adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is associated with adverse health outcomes including falls, poorer health-related quality of life (HRQOL), hospitalisation and mortality. Low physical activity and muscle wasting are important contributors to physical frailty in adults with CKD. Exercise training may improve physical function and frailty status leading to associated improvements in health outcomes, including HRQOL. The EX-FRAIL CKD trial aims to inform the design of a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT) that investigates the effectiveness of a progressive, multicomponent home-based exercise programme in prefrail and frail older adults with CKD.

Methods and analysis

The EX-FRAIL CKD trial is a two-arm parallel group pilot RCT. Participants categorised as prefrail or frail, following Frailty Phenotype (FP) assessment, will be randomised to receive exercise or usual care. Participants randomised to the intervention arm will receive a tailored 12-week exercise programme, which includes weekly telephone calls to advise on exercise progression. Primary feasibility outcome measures include rate of recruitment, intervention adherence, outcome measure completion and participant attrition. Semistructured interviews with a purposively selected group of participants will inform the feasibility of the randomisation procedures, outcome measures and intervention. Secondary outcome measures include physical function (walking speed and Short Physical Performance Battery), frailty status (FP), fall concern (Falls Efficacy Scale-International tool), activities of daily living (Barthel Index), symptom burden (Palliative care Outcome Scale-Symptoms RENAL) and HRQOL (Short Form-12v2).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval was granted by a National Health Service (NHS) Regional Ethics Committee and the NHS Health Research Authority. The study team aims to publish findings in a peer-reviewed journal and presents the results at relevant national and international conferences. A summary of findings will be provided to participants, a local kidney patient charity and the funding body.

Trial registration number

Keywords: adult nephrology, chronic renal failure, end stage renal failure, geriatric medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A validated frailty assessment will be used to determine suitability for randomisation ensuring that only prefrail and frail participants receive the intervention.

The exercise programme is delivered in a graded and progressive manner with the use of weekly participant telephone calls to review progress.

A nested qualitative study will explore the acceptability of the randomisation procedures, outcome measures and intervention to participants.

Semistructured interviews will be completed by a researcher involved in delivery of the study intervention.

Patients who decline study enrolment will not be offered the opportunity to participate in the qualitative study.

Introduction

Frailty is the consequence of a cumulative decline in multiple physiological systems associated with ageing.1 This results in a state of increased vulnerability to disproportionate changes in health status when exposed to seemingly minor insults, such as an infection or fall.1 Frailty, and its precursor prefrailty, is associated with an increased risk of falls, hospitalisation, worsening disability and death.2 The pathophysiological process inherent to chronic kidney disease (CKD), including, though not limited to, uraemia, anabolic hormone dysregulation, increased inflammatory burden, metabolic acidosis and cellular senescence, appears to hasten the decline from fitness to frailty.3 This is to such an extent that the prevalence of frailty in CKD, particularly by the time of dialysis initiation, is considerably greater than in the community-dwelling older adult population.4 5 Importantly, as in the general older population, patients with CKD and frailty have worse outcomes than their non-frail counterparts. Frailty is independently linked with adverse clinical outcomes in all stages of CKD, including an increased risk of worse health-related quality of life (HRQOL),6 7 falls,8 hospitalisation and mortality.9–11

Low physical activity and associated muscle wasting are important contributors to physical frailty.3 Physical activity is low in patients with advanced CKD12, and muscle wasting is pronounced prior to the commencement of dialysis.13 Increased physical activity levels in those with CKD and prefrailty/frailty may mitigate this muscle wasting. Exercise training has been shown to improve physical fitness and HRQOL in CKD populations.14 15 However, patients living with frailty are typically poorly represented in interventional studies, often due to concerns that drop-out rates, adverse events or intervention tolerability may be affected.16 17 Studies that have explored the use of exercise training in frail older adults have demonstrated benefits in terms of ‘falls, mobility, balance, functional ability, muscle strength and body composition’.18 However, the optimum exercise programme has not been established.18 Regardless, exercise programmes that are effective for frail older adults may not meet the needs of patients living with frailty and CKD, who are more likely to be frail at a younger age,10 report considerable symptom burden19 and have high healthcare utilisation.20

Many exercise programmes used in studies involving participants with CKD have been performed under supervision within hospital or other facilities,14 15 circumstances that can be challenging to implement in clinical practice considering financial and staffing constraints. Furthermore, travel for exercise sessions may be onerous for frail individuals with CKD who often report higher levels of fatigue.6 Home-based exercise programmes may be less burdensome and more convenient, allowing patients to incorporate physical activity into their daily lives leading to longer term adoption and maintenance of increased physical activity.21 There is evidence in the gerontology literature that home-based exercise interventions may improve disability in older people with frailty.22 However, research is needed to evaluate the benefits of a pragmatic, progressive home-based exercise programme tailored to the needs of people living with frailty and CKD.

As recommended by the Medical Research Council guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions,23 pilot studies should be used to address key uncertainties prior to the definitive evaluation of complex interventions. Given the previously described uncertainties, a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a home-based exercise programme for prefrail and frail older adults with CKD is necessary. This will inform the design of a large-scale RCT that investigates the effect of a home-based exercise intervention on physical function, frailty status, fall concern, activities of daily living, symptom burden and HRQOL in prefrail and frail older adults with CKD. The 2013 Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials guidelines24 25 will be used as the framework for reporting the EX-FRAIL CKD trial protocol.

Objectives

A pilot RCT will be performed that aims to:

Evaluate rate of participant recruitment, intervention adherence, outcome measure completion and attrition.

Qualitatively explore the acceptability of the randomisation procedure, outcome measures and, in the intervention arm, a progressive home-based exercise programme and identify areas requiring adaptation for a definitive RCT.

Estimate the SD of walking speed in prefrail and frail patients with CKD to allow sample size estimation for a definitive RCT.

Methods and analysis

Design

The EX-FRAIL CKD trial is a two-arm parallel group pilot RCT. Outcome assessments will be performed at baseline and 12 weeks’ post randomisation. A nested qualitative study will be performed following completion of 12-week follow-up visits to explore participant perceptions of the study and, where applicable, the study intervention.

Study setting

Participants will be recruited from outpatient clinics at Lancashire Teaching Hospitals National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust (LTHTR), East Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The regional nephrology service operates a ‘hub-and-spoke’ model, accordingly participants attending clinics at sites other than LTHTR are still under the care of the LTHTR nephrology service.

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged ≥65 years old with CKD G3b-5 (not receiving dialysis or received a kidney transplant) identified as at least ‘vulnerable’ using the Clinical Frailty Scale (score ≥4) are eligible for participation.26 The Clinical Frailty Scale is a 9-point scale that provides definitions for levels of frailty and has good diagnostic accuracy for identifying patients with advanced CKD at risk of frailty.26 27 It has been adopted as a frailty screening measure within usual care at LTHTR and is used by clinicians and clinical nurse specialists in outpatient clinics. Using a Clinical Frailty Scale score ≥4 within the inclusion criteria will maximise the likelihood of prefrail and frail patients being approached for study involvement. Patients must also be able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

In accordance with the American College of Sport’s Medicine28 :

Unstable Angina or recent (within the last 3 months) myocardial infarction.

Uncontrolled arrhythmias.

Persistent uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure >180 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure >110 mm Hg).

Recent (within the last 3 months) stroke or transient ischaemic attack.

Registered blind.

Unable to mobilise independently.

Receiving palliative care for advanced terminal cancer.

Recently (within the last 12 months) enrolled in a structured exercise programme (eg, cardiac rehabilitation) prescribed by a health professional.

Anticipated to commence dialysis or receive a renal transplant within the next 3 months.

Insufficient understanding of the English language to complete study questionnaires or follow advice within the exercise programme guidebook.

Clinical and/or research team consider participation in the exercise programme unsafe.

Timeline

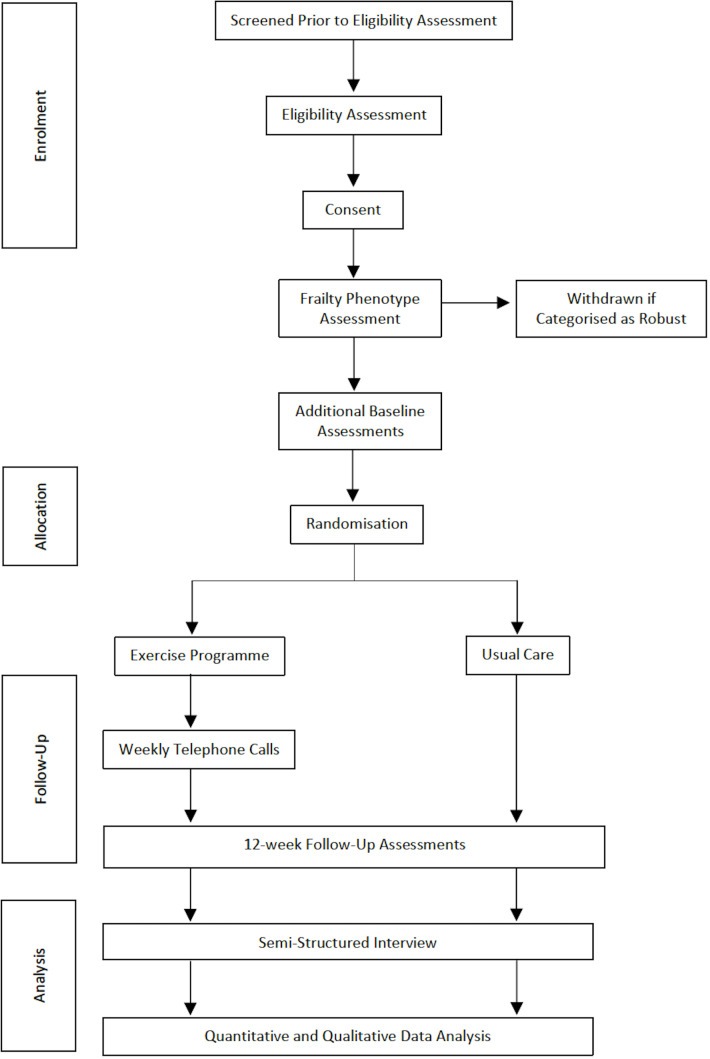

Figure 1 illustrates the participant flow through the study. Patients will be screened by members of the clinical team (based on age, CKD stage and Clinical Frailty Scale score). Patients aged ≥65 years with CKD G3b-5 and a Clinical Frailty Scale score ≥4 will be given a participant information sheet. Patients will then be telephoned to establish if they are interested in participating and to ensure eligibility. Patients will be offered an appointment with the Chief Investigator, at least 24 hours following the telephone call, to obtain written informed consent to participate in the study.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Our previous study demonstrated that a Clinical Frailty Scale score ≥4 had a sensitivity and specificity for identifying frailty of 1.00 and 0.55, respectively.27 Given the risk of false positives, we considered it prudent to perform a more objective frailty assessment to ensure that only patients with prefrailty or frailty underwent randomisation. The Frailty Phenotype (FP) is a well-studied method to diagnose physical frailty in CKD populations.2 5 The FP includes five components, as detailed in table 12. Frailty is diagnosed if an individual is assessed as having three components and prefrailty if an individual has one or two components.2 The FP is not routinely performed in clinical practice and, therefore, can only be performed following study consent. Participants will have an FP assessment prerandomisation and will be withdrawn from the study if they are categorised as robust (ie, not prefrail or frail). This eventuality will be explained to patients prior to study consent. Participants categorised as prefrail or frail will complete all outcome assessments as detailed in table 2, and then be randomised to exercise or usual care groups. Follow-up outcome assessments will be performed 12 weeks post randomisation. A group of participants will be invited to participate in semistructured interviews following 12-week follow-up assessments (or following a participant’s decision to stop the exercise programme).

Table 1.

The Frailty Phenotype

| Frailty Phenotype component | Measure |

| Unintentional weight loss | ≥10 pounds or ≥ 5% body weight over the preceding 12 months. |

| Weakness | Hand grip strength will be assessed in the seated position with the elbow positioned at 90°, supported by the arm of a chair, and with a hand grip dynamometer (Takei 5101 GRIP-A dynamometer, Takei Scientific Inst. Co. Ltd. Niigata, Japan) supported by the assessor. Both arms will be examined with the highest score from three efforts from each side used for analysis. The body mass index and gender stratified hand grip strength cut-offs proposed by Fried et al are used to define weakness.2 |

| Slowness | Walking speed (15 feet) will be assessed as outlined in the section titled ‘Physical Function’. The height and gender stratified walking speed cut-offs proposed by Fried et al are used to define slowness.2 |

| Low physical activity | A modified version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Questionnaire55 will be used to assess physical activity. Low physical activity is defined as <383 kcal/week for men and <270 kcals/wk for women.2 |

| Self-perceived exhaustion | The CES-D Scale will be used to assess self-perceived exhaustion.56 Participants will be read the following statements: (1) I felt that everything I did was an effort. (2) I could not get going. Participants will then be asked, ‘How often in the last week did you feel this way?’ and provided the following scale: 0=rarely or none of the time, 1=some of the time, 2=moderate amount of the time, 3=most of the time. Self-perceived exhaustion is defined as an answer ≥2 for either statement2. |

| Frailty is diagnosed if three or more frailty components are present. | |

| Prefrailty is diagnosed if one or two frailty components are present. | |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression.

Table 2.

Schedule of assessments

| Assessment | Time | ||

| Screening | Baseline | Follow-up | |

| Clinical Frailty Scale | X | ||

| Clinical characteristics | X | X | |

| Weight, height, HR, BP | X | X | |

| Laboratory variables | X | X | |

| Frailty Phenotype | X | X | |

| SPPB | X | X | |

| Barthel Index | X | X | |

| SF-12 | X | X | |

| FES-I | X | X | |

| POS-S RENAL | X | X | |

| Semistructured Interview | X | ||

BP, blood pressure; FES-I, Falls Efficacy Scale-International; HR, heart rate; POS-S RENAL, Palliative care Outcome Scale-Symptoms RENAL; SF-12, Short Form-12v2; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Sample size

We aim to recruit 40 participants to allow for a dropout rate (that includes participants categorised as robust using the FP) of up to 50% and still provide sufficient data to assess study feasibility and estimate the SD of walking speed to inform the sample size calculation for a definitive RCT.18 22 29 30 Semistructured interviews will be conducted with a purposively selected group of participants, from both study arms, considering age, gender and frailty status. A pragmatic sample size of 12–14 participants will be recruited to this nested qualitative study.

Allocation and blinding

Participants will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention or usual care. A central, concealed web-based randomisation process (www.sealedenvelope.com) will be performed in blocks of 4. Stratification will be limited to one factor, FP status, leaving two strata, that is, prefrailty and frailty.31 This will ensure that both groups contain similar proportions of prefrail and frail participants. Participants cannot be blinded to the outcome of randomisation due to the nature of the intervention. Furthermore, outcome assessors will not be blinded to the outcome of randomisation as this pilot study does not aim to evaluate intervention effectiveness. Blinding of outcome assessors will be performed if a definitive RCT is considered feasible.

Intervention development

The EX-FRAIL CKD exercise programme is a 12-week progressive, multicomponent home-based exercise programme. It was developed through review of international guidance and systematic reviews that evaluated exercise interventions in CKD and older adult populations. A 2014 systematic review demonstrated that exercise training is associated with improved health outcomes in adults with CKD.15 However, most studies evaluated interventions in adults with dialysis-dependent CKD and mostly aerobic exercise interventions.15 The authors recommended further evaluation in non-dialysis populations and further analysis of resistance training and multicomponent interventions.15 Several systematic reviews have demonstrated that frail older adults benefit from exercise programmes and reported multicomponent exercise programmes (involving combinations of strength, aerobic and balance training) were often effective.18 32 33 A 2012 Cochrane review determined that both multicomponent group exercise and home-based exercise reduce the rate of falls in older adults.34 Furthermore, a systematic review of home-based exercise programmes suggested that there is preliminary evidence that home-based exercise interventions may improve disability in older adults with moderate frailty.22 The American College of Sports Medicine and American Heart Association Guidelines highlight the importance of physical activity being increased gradually in older adults, particularly those who are very deconditioned.35 Additionally, the guidelines recommend that older adults who reduce their sedentary behaviour, even if not to the level recommended, still attain health benefits.35

Intervention description

Participants randomised to the intervention will receive an individual exercise education session delivered by a physiotherapist experienced in exercise prescription. Participants will be provided information about the potential benefits of physical activity for their general health and well-being. They will subsequently receive instruction on how to complete the exercises within the exercise programme safely and effectively. The exercises will be demonstrated to participants by a physiotherapist. The participants will then be asked to practice the exercises under supervision to ensure appropriate technique. If a participant is unable to perform a specific exercise, for example due to a functional limitation, an alternative will be provided that focuses on the same muscle groups. Furthermore, if a participant is unable to complete the proposed number of repetitions, the participant will be advised to perform a lower number of repetitions initially. This approach reflects exercise prescription in clinical practice and should increase the feasibility and safety of the exercise programme.

Table 3 demonstrates the six exercises within the programme and details the progressions for each exercise. Participants categorised as frail will initially be advised to perform each exercise at level 1, whereas participants categorised as prefrail will be advised to perform each exercise at level 2, unless the physiotherapist determines that it would be unsafe for an individual participant to perform a specific exercise at this level. Participants will receive education on how to use the Borg rating of perceived exertion36 and will be advised to perform exercise 1 at a light intensity (Borg score <12) and exercises 2–6 at a moderate intensity (Borg score 12–16). Participants will be asked to gradually increase physical activity levels so that they ultimately perform three exercise sessions at home per week, with each session lasting approximately 30–45 min. Participants will be provided an exercise guidebook comprising written guidance on each exercise with accompanying photographs of models demonstrating the exercises.

Table 3.

The EX-FRAIL CKD exercise programme

| Exercise | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 |

| 1. Walking | Walk for 1 min | Walk for 2 min | Walk for 10 min | Walk for 15 min |

| 2. Lower leg extension | Seated leg extension* | Seated leg raise* | Seated weighted (0.5 kg) leg raise* | Seated weighted (1 kg) leg raise* |

| 3. Bilateral calf raises | Seated calf raises* | Standing calf raises placing hands on secure surface* | Standing calf raises placing finger tips on secure surface* | Standing calf raises* |

| 4. Sit to stand | Sit to stand using arms to assist* | Sit to stand without using arms to assist* | Sit to stand holding 0.5 kg weights* | Sit to stand holding 1 kg weights* |

| 5. Wall/table push up | Wall push up† | Wall push up* | Table push up† | Table push up* |

| 6. Marching | Marching while seated* | Marching while standing with hands on secure surface* | Marching while standing* | Stair step* |

*3 sets of 10 repetitions.

†3 sets of 5 repetitions.

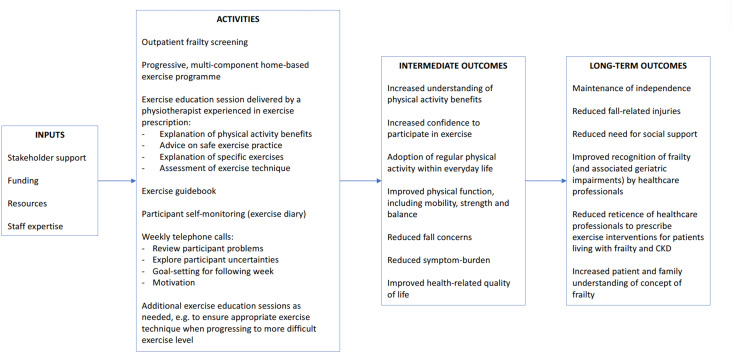

Participants will be encouraged to complete an exercise diary. The diary prompts participants to document each exercise session including when they exercised, if they completed all exercises, the duration to complete the full exercise session and their Borg rating of perceived exertion for each exercise completed. Participants randomised to the intervention will receive weekly telephone calls from the physiotherapist or a specialist trainee in renal medicine who has clinical and research experience with patients living with frailty and CKD. To enhance intervention fidelity, a telephone pro forma will be used that prompts a review of the participants exercise diary, exercise technique, any problems (including symptoms, falls and healthcare episodes), an exploration of any participant uncertainties about the exercise programme and goal-setting for the following week. The physiotherapist and specialist trainee will discuss the outcomes of telephone calls, as a further safeguard of intervention fidelity. The telephone calls will be used to provide ongoing encouragement and to advise on exercise progression. If participants can perform exercises 2–6 comfortably (Borg score <12), the physiotherapist or specialist trainee will discuss exercise progression with the participant. If required, participants will be offered additional educational sessions during the 12-week intervention period to ensure safe exercise technique when progressing to more difficult exercise levels. Figure 2 illustrates the Exercise Intervention Logic Model and table 4 summarises the intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication checklist.37

Figure 2.

Exercise Intervention Logic Model.

Table 4.

TIDier checklist

| Item | |

| 1. Brief name | The EX-FRAIL CKD exercise programme. |

| 2. Rationale | Described in ‘Introduction’ and section titled ‘Intervention development’. |

| 3. Materials | Exercise guidebook, exercise diary and wrist/ankle weights. |

| 4. Procedures | Described in section titled ‘Intervention description’ and ‘ Timeline’. |

| 5. Provider | Exercise programme education will be delivered by a physiotherapist experienced in exercise prescription. Weekly telephone calls will be performed by the physiotherapist or specialist trainee with relevant experience. |

| 6. Modes of delivery | Face-to-face exercise education session followed by weekly telephone calls. |

| 7. Location | Exercise education sessions will be delivered in a private room at NIHR Lancashire Clinical Research Facility. All exercise sessions will be completed in the participant’s own home. |

| 8. Frequency and duration | All participants will have an exercise education session lasting approximately 60 min. Participants will aim to perform three exercise sessions at home per week, lasting approximately 30–45 min each. |

| 9. Tailoring | Initial exercise level will be determined by frailty status, unless the physiotherapist determines otherwise due to safety concerns. An alternative exercise will be provided if a participant is unable to perform a specific exercise as originally intended. |

| 10. Modifications | Cannot be described until study completion. |

| 11. Adherence and fidelity: planned | Exercises will be delivered as described in the exercise guidebook. If modification is needed, the participant (and study team) will be provided additional documentation. Adherence will be assessed during telephone calls and review of the participant’s exercise diary. Outcomes of telephone calls will be discussed to maintain fidelity. |

| 12. Adherence and fidelity: actual | Cannot be described until study completion. |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; NIHR, National Institute of Health Research; TIDier, Template for Intervention Description and Replication.

Patient and public involvement

The study was presented to the LTHTR Research Development Group, which includes lay members. Feedback from this meeting led to the adoption of a study design that included a nested qualitative interview study. The proposed study was also presented to members of a local kidney patient charity, discussed in a patient focus group, supported by funding received from National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Design Service, and with the LTHTR Lay Research Group, which is a group of local lay representatives. The study team was encouraged by positive feedback received on proposed study visits, outcome assessments and the exercise programme, including the burden of the intervention.

Primary feasibility outcome measures

Primary feasibility outcome measures will be assessed as recommended by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) randomised pilot and feasibility trial guidelines.38 The proportion of patients attending nephrology clinics who are eligible for study consent and the proportion of eligible patients subsequently recruited will be recorded. Reasons for ineligibility and non-consent will be recorded. In the intervention arm, adherence will be assessed by telephoning participants weekly to review the preceding week’s exercise activity and by reviewing participant exercise diaries at the end of the study period. Reasons for non-adherence will be documented. The proportion of participants who complete all outcome measures and who are lost to follow-up will be assessed. Reasons for failure to complete outcome measures and for study withdrawal will be recorded.

Using a predetermined topic guide, the specialist trainee will conduct semistructured face-to-face interviews with participants. The interviews aim to explore the acceptability of the randomisation procedure, outcome measures and, in the intervention arm, a progressive home-based exercise programme. Perceived safety and barriers to participation will be explored. The interviews will be conducted in a private environment at the NIHR Lancashire Clinical Research Facility. Interviews will be audio recorded using a digital recorder with the participant’s consent and will last approximately 30–60 min. Interviews will be transcribed verbatim.

A ‘stop’, ‘change’ and ‘go’ approach to progression criteria will be used as described in the literature,39 with qualitative data used to identify areas for adaptation for a definitive RCT, if required. Table 5 details the study progression criteria.

Table 5.

Progression criteria

| Progression criteria | Stop/go thresholds |

| Eligibility | Stop: <5% of patients eligible Go: >10% of patients eligible |

| Recruitment | Stop: <10% of eligible patients recruited Go: >30% of eligible patients recruited |

| Exercise adherence (defined as ≥2 sessions/week) |

Stop: <30% adherence Go: >70% adherence |

| Outcome measure completion (not including lost to follow-up) |

Stop :<70% outcome measure completion Go: >80% outcome measure completion |

| Lost to follow-up (including withdrawn and lost) |

Stop: >50% lost to follow-up Go: <25% lost to follow-up |

Secondary outcome measures

Physical function

Walking speed is independently associated with all-cause mortality in adults with CKD.40 Walking speed will be assessed using infrared timing gates (Brower Timing System 2012, Brower Timing Systems, Draper, Utah, USA). Participants will be asked to walk 15 feet at their normal walking pace on two occasions, using their usual walking aid if applicable. The fastest of the two assessments will be used for analysis. A meaningful change in walking speed has been described as 0.05 m/s.41 42

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) comprises a group of measures of lower extremity function that together can be used to generate a composite score between 0 and 12.43 SPPB score is associated with mortality in adults with CKD.44 A minimally significant change in SPPB has been reported as 0.5 points.41 42 The measures included in the SPPB are:

Five chair stands: timed standing from a chair at a standardised height five times as quickly as able.

Balance testing: stand in three positions with increasing difficulty (standing with feet side by side, in a semitandem position and in a full tandem position) for 10 s in each position.

Walking speed: timed walking 8 feet at usual pace.

Frailty

As described earlier and detailed in table 1, the FP can be used to diagnose prefrailty and frailty,2 which are associated with adverse outcomes in CKD populations.6–11 Studies have not evaluated the change in frailty status following exercise interventions in CKD populations. However, McAdams-DeMarco et al demonstrated an improvement in FP score of 0.3 points following transplantation.45

Activities of daily living

The Barthel Index evaluates independence with 10 activities of daily living to generate a score between 0 and 100.46 Higher scores indicate greater independence.

Falls

The Falls Efficacy Scale-International tool will be used to assess fall concern.47 48 It is a self-report questionnaire that asks individuals to rate their fall concern for 16 situations on a 4-point scale. The answers are totalled to provide a cumulative score between 16 and 64. A score between 16 and 19 indicates low fall concern, between 20 and 27 moderate fall concern and between 28 and 64 high fall concern. The number of falls within the preceding 6 months will also be recorded.

Symptom burden

The Palliative care Outcome Scale-Symptoms RENAL (POS-S RENAL) will be used to assess symptom burden.49 The POS-S RENAL questionnaire asks individuals to report 17 symptoms that may have affected them over the preceding week and to indicate to what extent. Each symptom is scored and scores totalled to create a symptom burden score with higher scores representing greater symptom burden.

HRQOL

The Short Form-12v2 (SF-12) comprises 12 questions that are used to assess HRQOL.50 51 The answers are used to produce an 8-scale profile of health and well-being and to generate physical and mental health summary measures. Higher SF-12 scores represent better HRQOL. The proposed minimal important difference for SF-12 summary scales is 3 T-score points.52

Data management

All electronic study data will be recoded on a secure, password-protected database on the LTHTR server. The server will only be accessible using password-protected user profiles on LTHTR computers. Participant names and hospital identification numbers will not be recorded on this database; participants will be identified by a study-specific participant number. There will not be a formal data monitoring committee. However, data will be managed in accordance with the LTHTR Information Governance Policy.

Analysis plan

As recommended by the 2010 CONSORT guidelines,38 feasibility quantitative outcome measures will be reported descriptively with 95% CIs. This will include the proportion of eligible patients and recruited participants, participants who adhere to the intervention, participants who complete all outcome assessments and participants who are lost to follow-up. Secondary outcome measures will also be reported descriptively with 95% CIs. The SD of walking speed will be estimated for both trial arms to inform the sample size calculation for a definitive RCT. SPSS software (V.25, IBM Corp) will be used for statistical analysis.

Qualitative data will be analysed using thematic analysis whereby narrative segments will first be coded, and then translated into more abstract themes in an iterative manner.53 NVivo software (V.12.5.0, QSR International) will be used to support analysis. Two members of the researcher team will compare themes to ensure all codes are represented. Qualitative and quantitative findings will be linked using a triangulation approach as described by Farmer et al54 to provide a more comprehensive understanding of trial and intervention acceptability.

Adverse events

Serious adverse events are defined as any episode during the study period that requires inpatient hospitalisation, results in persistent/significant disability, is life-threatening or results in death. All adverse events will be discussed with the medically trained Chief Investigator who will assess seriousness and causality. All adverse events will be reported to the study sponsor and all suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions reported to the regional ethics committee. The trial will be stopped prematurely if three or more suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions occur.

Study steering committee

A study steering committee will provide scientific, ethical and financial oversight of research activity. The committee comprises clinicians, physiotherapists, academics, a study sponsor representative and a patient representative. Meetings will be held during before, during and on completion of the study. The patient representative will be remunerated as recommended by INVOLVE.

Ethics and dissemination

Study ethical approval has been granted by the North West Greater Manchester East Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/NW/0211) and the NHS Health Research Authority (project reference 244772). The LTHTR Centre for Health Research and Innovation accepted the role and responsibilities of study sponsorship. The study is subject to the LTHTR Internal Research and NIHR audit programmes to ensure all research activities are performed in accordance with the international standards of Good Clinical Practice, United Kingdom clinical trials legislation and trust policies. Protocol amendments approved by the Research Ethics Committee/NHS Health Research Authority will be communicated with the study sponsor, study team and, where necessary, the trial registry.

The study data set will not be made publicly available as it may be possible to identify participants from interview transcripts and as this pilot study does not aim to use quantitative data to demonstrate intervention effectiveness. The study team aims to publish the findings in a peer-reviewed journal and presents the results at national and international conferences. A summary of findings will be provided to participants, a local kidney patient charity and the funding body.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the EX-FRAIL CKD trial is the first pilot RCT of a progressive home-based exercise intervention specifically designed for prefrail and frail older adults with CKD. Given the uncertainties around recruitment rates, intervention adherence and outcome measure acceptability, it is necessary to perform a pilot study prior to proceeding with a full-scale trial. These uncertainties have been considered during study design, though amendments may be required to maximise the success of a multicentre RCT.

This study’s strengths include the use of a validated frailty screening measure27 to assist participant recruitment and, during baseline assessment, the use of the reference standard for diagnosing physical frailty, that is, the FP,2 to determine suitability for randomisation. This methodology will minimise the number of robust individuals approached for study consent and ensure that only prefrail and frail participants receive the intervention, thereby strengthening any conclusions that can be made following study completion. Furthermore, the nested qualitative study will complement quantitative data analysis by exploring the acceptability of the randomisation procedures, outcome measures and intervention, thus identifying areas for adaptation in a definitive RCT. An acknowledged limitation is that semistructured interviews will be completed by a researcher involved in delivery of the study intervention, which may influence participant responses. However, the participants will be encouraged to give honest responses by reinforcing that the study objectives include to explore the acceptability of the study and identify areas requiring adaptation for a definitive RCT. For pragmatic reasons, patients who decline to participate in the study will not be invited to participate in an interview. However, participants who decide to stop exercising earlier than planned will be invited to participate in an interview to explore their experience of the study. Furthermore, participants’ rationale and motivation for enrolling in the study will be explored during interviews.

Home-based exercise programmes have been performed safely in frail older adults;22 however, perceived safety concerns (eg, fall concerns) may influence participant adherence to the exercise programme. Participants randomised to the intervention arm will receive exercise education from a physiotherapist experienced in exercise prescription. Moreover, the exercise programme will be delivered in a graded and progressive manner with the use of weekly telephone calls that ensure safe exercise practices, explore participant uncertainties and provide ongoing support. We hope that the above will minimise participant concerns; therefore maximising participant adherence to the exercise programme.

The EX-FRAIL CKD trial aims to inform the design of a definitive multicentre RCT that explores the benefits of a progressive, multicomponent home-based exercise programme. If a definitive RCT demonstrates improvements in the physical function of participants, associated improvements in mobility, fall concern, independence, symptom burden and HRQOL are anticipated, supporting the case for a home-based exercise programme within routine clinical care.

Trial status

The study opened in August 2018 and the first participant was recruited in November 2018. Data collection was completed in December 2019.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @DrAndyNixon, @drtheobampouras, @hmlyoungphysio

Contributors: All authors contributed to the research idea and study design. ACN, TMB, HJG and HMLY were involved in the development of the EX-FRAIL CKD exercise programme. ACN and HMLY developed the study progression criteria. ACN, TMB and HMLY contributed to the quantitative analysis plan. HMLY and KWF contributed to the qualitative analysis plan. MEB, NP, APD and SM were involved in supervision/mentorship. ACN drafted the manuscript. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript revision and accepts responsibility for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The EX-FRAIL CKD Trial is supported by a grant from Kidney Research UK (IN_013_20180306), which has funded equipment costs and HJG’s study-related activity. ACN and HJG receive non-financial support from the NIHR Lancashire Clinical Research Facility. HMLY is supported by a grant from the NIHR (DRF-2016-09-015). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Competing interests: Unrelated to this body of work, APD has received lecture fees from speaking at the invitation of MSD and received travel support from Pharmacosmos.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–57. 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, et al. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: current evidence and continuing uncertainties. Clin Kidney J 2018;11:236–45. 10.1093/ckj/sfx134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, et al. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1487–92. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowdhury R, Peel NM, Krosch M, et al. Frailty and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2017;68:135–42. 10.1016/j.archger.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, et al. Frailty is independently associated with worse health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: a secondary analysis of the frailty assessment in chronic kidney disease study. Clin Kidney J 2020;13:85–94. 10.1093/ckj/sfz038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyasere OU, Brown EA, Johansson L, et al. Quality of life and physical function in older patients on dialysis: a comparison of assisted peritoneal dialysis with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:423–30. 10.2215/CJN.01050115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Suresh S, Law A, et al. Frailty and falls among adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2013;14:224. 10.1186/1471-2369-14-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Jin C, et al. Significance of frailty among dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007;18:2960–7. 10.1681/ASN.2007020221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roshanravan B, Khatri M, Robinson-Cohen C, et al. A prospective study of frailty in nephrology-referred patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;60:912–21. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:896–901. 10.1111/jgs.12266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansen KL, Chertow GM, Kutner NG, et al. Low level of self-reported physical activity in ambulatory patients new to dialysis. Kidney Int 2010;78:1164–70. 10.1038/ki.2010.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John SG, Sigrist MK, Taal MW, et al. Natural history of skeletal muscle mass changes in chronic kidney disease stage 4 and 5 patients: an observational study. PLoS One 2013;8:e65372. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training for adults with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD003236. 10.1002/14651858.CD003236.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heiwe S, Jacobson SH. Exercise training in adults with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:383–93. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:625–34. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMurdo MET, Roberts H, Parker S, et al. Improving recruitment of older people to research through good practice. Age Ageing 2011;40:659–65. 10.1093/ageing/afr115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Labra C, Guimaraes-Pinheiro C, Maseda A, et al. Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:154. 10.1186/s12877-015-0155-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown SA, Tyrer FC, Clarke AL, et al. Symptom burden in patients with chronic kidney disease not requiring renal replacement therapy. Clin Kidney J 2017;10:788–96. 10.1093/ckj/sfx057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan SS, Kazmi WH, Abichandani R, et al. Health care utilization among patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2002;62:229–36. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashworth NL, Chad KE, Harrison EL, et al. Home versus center based physical activity programs in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD004017. 10.1002/14651858.CD004017.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clegg AP, Barber SE, Young JB, et al. Do home-based exercise interventions improve outcomes for frail older people? findings from a systematic review. Rev Clin Gerontol 2012;22:68–78. 10.1017/S0959259811000165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;2013:200–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005;173:489–95. 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of frailty screening methods in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron 2019;141:147–55. 10.1159/000494223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.pp Pescatello L, Arena R, Riebe D, et al. Exercise prescription for patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease; American college of sports medicine’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription 2013:236–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat 2005;4:287–91. 10.1002/pst.185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitehead AL, Julious SA, Cooper CL, et al. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat Methods Med Res 2016;25:1057–73. 10.1177/0962280215588241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Makuch RW, et al. Stratified randomization for clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:19–26. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00138-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Theou O, Stathokostas L, Roland KP, et al. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of frailty: a systematic review. J Aging Res 2011;2011:569194 10.4061/2011/569194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Vries NM, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JSM, et al. Effects of physical exercise therapy on mobility, physical functioning, physical activity and quality of life in community-dwelling older adults with impaired mobility, physical disability and/or multi-morbidity: a meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2012;11:136–49. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD007146. 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American college of sports medicine and the American heart association. Circulation 2007;116:1094–105. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borg G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand J Rehabil Med 1970;2:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016;355:i5239. 10.1136/bmj.i5239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avery KNL, Williamson PR, Gamble C, et al. Informing efficient randomised controlled trials: exploration of challenges in developing progression criteria for internal pilot studies. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013537. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roshanravan B, Robinson-Cohen C, Patel KV, et al. Association between physical performance and all-cause mortality in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;24:822–30. 10.1681/ASN.2012070702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwon S, Perera S, Pahor M, et al. What is a meaningful change in physical performance? findings from a clinical trial in older adults (the LIFE-P study). J Nutr Health Aging 2009;13:538–44. 10.1007/s12603-009-0104-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, et al. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:743–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994;49:M85–94. 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacKinnon HJ, Wilkinson TJ, Clarke AL, et al. The association of physical function and physical activity with all-cause mortality and adverse clinical outcomes in nondialysis chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2018;9:209–26. 10.1177/2040622318785575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Isaacs K, Darko L, et al. Changes in frailty after kidney transplantation. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2152–7. 10.1111/jgs.13657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahoney FI, BARTHEL DW. Functional evaluation: the BARTHEL index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, et al. Development and initial validation of the falls efficacy scale-international (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005;34:614–9. 10.1093/ageing/afi196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delbaere K, Close JCT, Mikolaizak AS, et al. The falls efficacy scale international (FES-I). A comprehensive longitudinal validation study. Age Ageing 2010;39:210–6. 10.1093/ageing/afp225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy EL, Murtagh FEM, Carey I, et al. Understanding symptoms in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis: use of a short patient-completed assessment tool. Nephron Clin Pract 2009;111:c74–80. 10.1159/000183177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lacson E, Lin S-F, Lin S-F, et al. A comparison of SF-36 and SF-12 composite scores and subsequent hospitalization and mortality risks in long-term dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:252–60. 10.2215/CJN.07231009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maruish MEE. User’s manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey. Third edn Lincoln, RI: : QualityMetric Incorporated, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farmer T, Robinson K, Elliott SJ, et al. Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qual Health Res 2006;16:377–94. 10.1177/1049732305285708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Schucker B, et al. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 1978;31:741–55. 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. Factorial and discriminant validity of the center for epidemiological studies depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol 1986;42:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.