Abstract

Objective

To assess where the delays occur in the referral chain of most maternal health outcomes in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, based on the three-delay model.

Design

The study was a facility-based, cross-sectional study.

Setting

Two public and tertiary hospitals in Addis Ababa.

Participants

All pregnant women who were referred only for labour and delivery services after 28 weeks of gestation between December 2018 and February 2019 in Zewditu and Gandhi Memorial Hospitals.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome was the type of delays, from the three-delay model, which met operationally defined time. The secondary outcome was maternal health outcomes based on the three-delay model.

Results

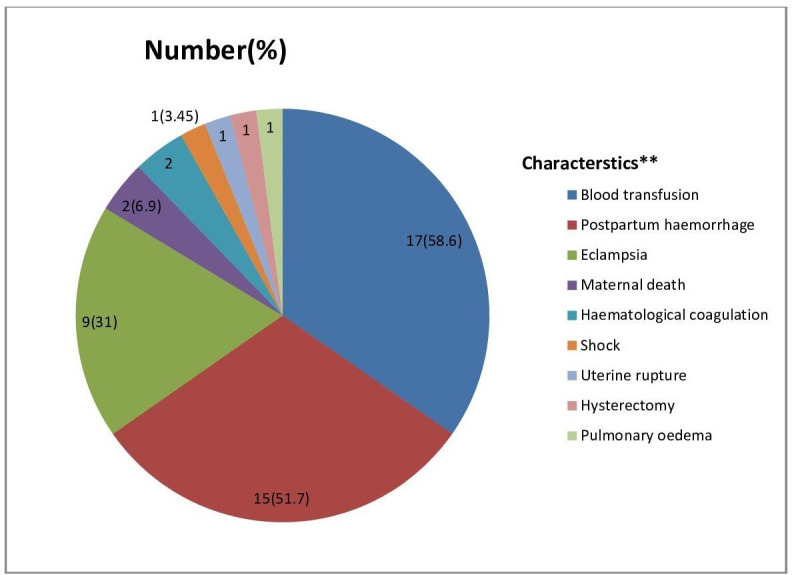

A total of 403 pregnant women referred for delivery to the study hospitals were included in the study. Three-fourths (301, 74.7%) of the referred pregnant women experienced the third delay (delay in receiving appropriate care); 211 (52.4%) experienced the first delay (delay in making a decision to seek care). Overall 366 (90.8%) pregnant women had experienced at least one of the three delays and 71 (17.6%) experienced all three delays. Twenty-nine (7.2%) referred women had severe maternal outcomes. The leading causes/diagnoses of severe maternal outcomes were blood transfusion (17, 58.6%), followed by postpartum haemorrhage (15, 52%) and eclampsia (9, 31%). In addition, women who experienced severe maternal outcomes were 2.9 times more likely to have experienced at least one of the three delays.

Conclusion and recommendation

This study highlights the persistence of delays at all levels, and especially the third delay and its contribution to severe maternal outcomes. We recommend strengthening the health referral systems and addressing specific health system bottlenecks during labour and birth in order to ensure no mother is endangered. We also recommend conducting a qualitative method of study (focus group discussion and indepth interview) and observing tertiary hospitals’ set-up and readiness to manage obstetric emergencies.

Keywords: human resource management, health policy, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides data on the extent of delays and severe maternal outcomes experienced by women who were referred for labour and delivery.

This study focused on women with severe maternal outcomes rather than the less severe forms of obstetric complications since their conditions put them at the highest risk for maternal deaths.

The study might have missed women who have transferred to health centres and other hospitals after delivery for different reasons.

The results might not be representative of other institutions and communities because the study was conducted in two referral hospitals which often receive and treat complicated cases.

Introduction

According to the WHO’s report on maternal mortality trends, about 295 000 women died during and following pregnancy and childbirth in 2017.1 Similarly, the 2019 WHO maternal mortality fact sheet reported that approximately 810 women die every day from pregnancy-related complications. The vast majority of these deaths (94%) occurred in low-resource settings and most could have been prevented.2 Sub-Saharan Africa alone accounted for roughly two-thirds (196 000) of maternal deaths, and Ethiopia is among these countries.1 2

Globally, it is recognised that significant inroads in maternal mortality cannot be made without dramatically increasing access to emergency obstetrical care. The WHO estimates that at least 88%–98% of maternal deaths can be averted with timely access to existing, emergency obstetric interventions.3 This produces a triple return on investment, saving women and newborns and preventing stillbirths.4

A number of factors can influence a woman’s ability to access effective interventions for treating complications in the event of an obstetric emergency. Thaddeus and Maine5 group these into three broad categories using a classic, pathways-based framework known as the ‘three delays model’. The ‘three delays model’ attempts to explain delays in women accessing emergency obstetric care as a result of (1) decision-making, (2) accessing services and (3) receipt of appropriate care once a health facility is reached.

Referral is often associated with the second delay of the three-delay model, associated with reaching appropriate level of care. However, in fact, a referral system can reduce all three delays. If a population knows that a system is reliable and affordable, families may make the decision to seek care more quickly (the first delay).6

The major obstacles that affect the referral system reported by both health workers and women were (1) financial barriers (for transportation and service payments to health facilities), (2) lack of means of transportation, (3) distance, and (4) lack of awareness of services and the importance of services.7

Factors associated with health-seeking behaviour are multidimensional. Sociocultural and economic problems, lack of awareness, quality of health service, and infrastructure such as transport services all affect whether and where a woman will seek care, how long it will take to reach care and whether she receives the appropriate care in a timely fashion.8

Studies showed referrals in pregnancy and childbirth can be (1) institutional or self-referral, depending on the involvement of first-line services; (2) antenatal, delivery or postnatal referral; and (3) elective or emergency referral. Pregnant women may be referred due to demographic risks, obstetric historical risks, prenatal complications, and delivery and immediate postnatal complications.9 On the other hand, studies show that high-risk prediction may not necessarily mean that the woman will have a complication, and many women identified as being at risk go on to have normal deliveries.10

Defining a framework and process for obstetric referrals may lead to a reduction in maternal mortality and morbidity. Referral should be broadly defined to include not only transport, but also a timely referral to minimise or prevent delay in transportation (called the second delay) and ensure prehospital care while transporting the patient to the referral facility.11 12

It is widely accepted that substantial reductions in maternal mortality and maternal near-miss are impossible to achieve without early decision-making to seek care, an effective referral system for complicated cases and receiving timely and appropriate care.7 13 Near-miss cases represent most of the characteristics of maternal deaths, but occur more often.14 The near-miss approach assesses the gap between the actual use and the optimal use of high-priority effective interventions in the prevention and management of severe maternal complications related to pregnancy and childbirth.15

The objective of this study was to determine the types of delay and maternal health outcomes based on the three-delay model among women referred for labour and delivery. The results from this study may help hospitals, health bureaus, policy-makers and other stakeholders to act on bottlenecks of emergency obstetric services by identifying the most common types of delay.

Methods

We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology cross-sectional reporting guidelines.16

Study design

A facility-based, cross-sectional study was conducted between 10 December 2018 and 28 February 2019 at two government hospitals: Zewditu Memorial Hospital and Gandhi Memorial Hospital.

Study setting

This study was conducted in tertiary hospitals located in the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. Both hospitals are under Addis Ababa Health Bureau and affiliated with Addis Ababa University-College of Health Sciences. Gandhi Memorial Hospital is a referral maternity hospital and Zewditu Memorial Hospital is also a comprehensive referral hospital. Both hospitals are catchment hospitals for 40 health centres and other health facilities. Both hospitals provide comprehensive emergency obstetric care (CEmOC) and attend to more than 17 000 deliveries per year.

The referral system for an obstetric emergency in Addis Ababa is organised to include basic emergency obstetric care (BEmOC) and CEmOC facilities. The referral system is developed to work both ways. Referral between health facilities is facilitated by the liaison office or the Maternal Health Task Force. An ambulance system is organised to transport women accompanied by midwives. The midwife provides care during transportation and hand over the mother to the receiving hospital care provider with a referral paper. In Addis Ababa, all maternity services including labour/delivery and the ambulance services are provided free of charge in all government health facilities. All hospitals (including primary, secondary and tertiary) and maternity and child hospitals are expected to provide CEmOC. On the other hand, all components of BEmOC are expected to be provided at the health centres, medium clinics and specialty clinics.

Eligibility criteria

The study included all pregnant women who were referred only for labour and delivery services after 28 weeks of gestation or have a baby with a birth weight ≥1 kg and delivered in the selected hospitals, and those who gave consent.

Data collection tools

After giving birth, women were identified and interviewed by data collectors, using pretested and structured questionnaires, in the emergency outpatient department, labour ward and inpatient wards every day before they were discharged from the hospital.

Data collection procedures

The referral papers were reviewed and the date, time and diagnosis of referral were recorded for each mother. The triage paper and patient chart are also reviewed, including the mode of transportation, date and time of arrival, sources of referral, obstetric performance, time taken to admit/access the service after arrival, diagnosis at receiving hospital, gestational age, place and mode of delivery, newborn outcomes, and severe maternal complication type and management. Women were also interviewed with regard to sociodemographic characteristics, time interval to seek medical advice and the reason for the delay in seeking care (if there was).

The completed questionnaires were reviewed by the principal investigator and supervisors. Incomplete questionnaires were filled in if the women have not been discharged; otherwise incomplete questionnaires were discarded.

Main outcomes and measures of the study

The three delays’ time frame was operationally defined through a consultative process involving six obstetricians and gynaecologists (three from each hospital) who had a working experience of 7–20 years in the selected hospitals. Accordingly, the first delay, defined as the time elapsed between the recognition of complication(s) and the decision to transport and reach a health facility, was considered if it took more than 60 min. The second delay was defined if the mother did not reach the referral hospital within 60 min of referral. The third delay was if the mother did not receive care or was not admitted within 30 min. Severe maternal outcomes (SMO) were any maternal complications including blood transfusion (any type and ≥2 units), postpartum haemorrhage, shock, eclampsia, uterine rupture, pulmonary oedema, laparotomy, laboratory evidence of organ damage and/or maternal death during the process of delivery and/or before discharge from the hospital. Potentially life-threatening maternal conditions were considered when the mother had at least one of the following: haemorrhagic complications, hypertensive disorders and complications, end-organ injury, blood product transfusion, intensive care unit admission, uterine rupture, and hysterectomy/laparotomy.

Sample size

Single proportion formula was used to calculate sample size, assuming 50% of the referred women experienced delay, with a 5% degree of precision and CI of 95% (Z=1.96), and assuming a 5% non-response rate; this resulted in a final sample size of 403.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in Epi Info V.7.2.2.6 and transported to SPSS V.21 statistics software for clean-up and analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to present women by their sociodemographic characteristics, referral diagnosis, diagnosis at receiving hospitals, obstetric characteristics, mode of delivery, newborn outcomes, the three delays and SMO. SMO was analysed for the three delays. The relationship between the three delays and SMO was examined using multivariate logistic regression. The goodness of fit of the model was tested using the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Selected variables were included in the model to account for differences in maternal characteristics other than delays in seeking and receiving care.

Ethical issues

Support letters were written to both study hospitals by Addis Ababa Health Bureau-Institution Review Board to gain access to data. Women were asked some questions after voluntarily providing informed consent. All responses were given by the participants, and the results obtained were kept anonymous and confidential.

Patient and public involvement

There was no public involvement in the design, conduct and interpretation of the study. Patients were not asked to advise on interpretation or in writing the results. There was no patient involvement in the design of this study. We have presented a summary of findings at medical and public health schools and among health providers in Addis Ababa and plan to continue presenting the results at professional society’s conferences. Results were shared with the administration of both selected hospitals and the Addis Ababa Health Bureau to facilitate improved obstetric services. There are no plans to disseminate the results of this research to study participants.

Results

Table 1 shows a descriptive information on the sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of the referred pregnant women. The mean age of the 403 pregnant women referred for labour and delivery services was 26.47±4.5 years and ranged from 18 to 43. Majority were married (380, 94.3%) and have completed at least secondary school education (54.3%). Majority of women were primigravida (56.1%), and the mean gravidity was 1.77±1.1 and ranged between 1 and 7. Most pregnant women (58.8%) were at term pregnancy (37 weeks to 41w6d) (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics of respondents, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019 (N=403)

| Characteristics, N=403 | n (%) |

| Study hospital | |

| Gandhi Memorial Hospital | 173 (42.9) |

| Zewditu Memorial Hospital | 230 (57.1) |

| Age (years), median: 26 years (range 18–43) | |

| <20 | 32 (7.9) |

| 20–25 | 158 (39.2) |

| 26–30 | 151 (37.5) |

| 31–35 | 46 (11.4) |

| ≥36 | 16 (4.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 380 (94.3) |

| Others (unmarried, divorced) | 23 (5.7) |

| Educational level | |

| No formal education | 49 (12.2) |

| Primary school | 135 (33.5) |

| Secondary school | 117 (29.0) |

| Preparatory | 35 (8.7) |

| Vocational and above | 67 (16.6) |

| Gravidity, n=403 | |

| 1 | 226 (56.1) |

| 2–4 | 165 (40.9) |

| ≥5 | 12 (3.0) |

| Parity, n=146 | |

| 1 | 90 (61.6) |

| ≥2 | 56 (38.4) |

| Abortion, n=60 | |

| 1 | 48 (80) |

| ≥2 | 12 (20) |

| Gestational age | |

| 28 weeks–33 weeks and 6 days | 9 (2.2) |

| 34 weeks–36 weeks and 6 days | 22 (5.5) |

| 37 weeks–41 weeks and 6 days | 237 (58.8) |

| ≥42 weeks | 42 (10.4) |

| Unknown | 93 (23.1) |

Majority of the pregnant women were referred from health centres (387, 96%) and transported by the ambulance (72%) (table 2).

Table 2.

Source of referral, transportation, mode and place of delivery, and perinatal outcome among the referred pregnant women for delivery, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Source of referral, n=403 | |

| Health centre | 387 (96.0) |

| Others | 16 (4.0) |

| Transportation | |

| Ambulance | 290 (72) |

| Others (taxi, personal car) | 113 (28) |

| Receiving hospital contacted before women were referred | |

| Yes | 157 (39.0) |

| No | 246 (61.0) |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Vaginal delivery | 229 (56.8) |

| Assisted breech delivery | 4 (1.0) |

| Caesarean section | 148 (36.7) |

| Instrumental delivery | 21 (5.2) |

| Vacuum | 16 (4.0) |

| Forceps | 5 (1.2) |

| Laparotomy | 1 (0.2) |

| Caesarean section indication, n=148 | |

| Non-reassuring fetal heart rate | 40 (27.0) |

| Meconium in LFSOL | 33 (22.3) |

| Cephalopelvic disproportion | 21 (14.2) |

| Malpresentation/malposition | 15 (10.1) |

| Previous caesarean scar with labour/labour abnormality | 10 (6.8) |

| Cord prolapse/presentation | 7 (4.7) |

| Non-reassuring biophysical profile | 5 (3.4) |

| Ante partum Haemorrhage (APH) | 4 (2.7) |

| Others | 13 (8.8) |

| Place of delivery, n=403 | |

| Labour ward/operation room | 386 (95.8) |

| Emergency outpatient department | 17 (4.2) |

| Outcome, n=403 | |

| Alive | 389 (96.5) |

| Newborn referred to NICU | |

| Yes | 137 (34) |

| No | 252 (62.5) |

| Stillbirth | 14 (3.5) |

| Fetal heart beat positive on arrival | 8 (2.0) |

| Fetal heart beat negative on arrival | 6 (1.5) |

LFSOL, Latent First stage of Labour; NICU, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

Majority of the women delivered through vaginal route (254, 63.3%), followed by caesarean section (148, 36.7%). The most common indication for caesarean section was non-reassuring fetal heart rate pattern (27%), followed by cephalopelvic disproportion/malpresentation/malposition (24.3%) and meconium staining in the latent first stage of labour (22.3%). The majority of the babies were born alive (389, 96.5%). There were eight (2%) intrapartum fetal losses (table 2).

Among the 403 referred women for childbirth, 71 (17.6%) experienced all the three delays. Almost three-fourths of the referred women (74.7%) experienced the third delay, followed by the first delay (52.4%). Majority (366, 90.8%) had experienced at least one of the delays (table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of the three delays among the referred women, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2019

| Characteristics, N=403 | n (%) | |

| Yes | No | |

| First delay | 211 (52.4) | 192 (47.6) |

| Second delay | 163 (40.4) | 240 (59.6) |

| Third delay | 301 (74.7) | 102 (25.3) |

| At least one delay | 366 (90.8) | 37 (9.2) |

| All three delays | 71 (17.6) | 332 (82.4) |

Twenty-nine (7.2%) women had SMO. The most common SMOs were blood transfusion (58.6%), followed by postpartum haemorrhage (51.7%) and eclampsia (31%). Nearly three-fourths of women with SMO (78.5%) had more than one complication (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Types of severe maternal outcomes among the referred pregnant women, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019. **multiple answer possible.

The most common delays in women with SMO were the third delay (58.6%), followed by the first delay (51.7%). Almost three-fourths of women experienced at least one of the delays (79.3%) and a quarter (24.1%) experienced all the delays (table 4).

Table 4.

SMO and types of delays, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2019

| Characteristics | Severe maternal outcomes | |||

| Types of delay | No | Yes | P value | COR, 95% CI |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| First delay | ||||

| No | 178 (47.6) | 14 (48.3) | ||

| Yes | 196 (52.4) | 15 (51.7) | 0.944 | 1.028 (0.483 to 2.189) |

| Second delay | ||||

| No | 224 (59.9) | 16 (55.2) | ||

| Yes | 150 (40.1) | 13 (44.8) | 0.618 | 1.213 (0.567 to 2.596) |

| Third delay | ||||

| No | 90 (24.1) | 12 (41.4) | ||

| Yes | 284 (75.9) | 15 (58.6) | 0.043 | 2.227 (1.025 to 4.840) |

| All delays | ||||

| No | 310 (82.9) | 22 (75.9) | ||

| Yes | 64 (17.1) | 7 (24.1) | 0.342 | 1.541 (0.632 to 3.761) |

| At least one delay | ||||

| No | 31 (8.3) | 6 (20.7) | ||

| Yes | 343 (91.7) | 23 (79.3) | 0.032 | 2.889 (1.093 to 7.620) |

AOR not significant after adjusting for age, marital status, educational level, gestational age, gravidity and parity.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; SMO, severe maternal outcomes.

Statistically, a significant association was observed between SMO and the third delay. Referred women who experienced the third delay were 2.2 times (95% CI 1.025 to 4.840) more likely to be at risk for SMO. Women who experienced at least one of the delays were 2.9 times (95% CI 1.093 to 7.620) more likely to be at risk for SMO (table 4).

After adjusting for age, gravidity, parity, educational level, gestational age and marital status, none of the delays was significant. This may be due to the small sample of women with SMO.

Eighty (19.9%) of the referred women had at least one potential life-threatening condition (PLTC). The most common complications were hypertensive disorders (56, 70%), followed by blood transfusion (17, 21.3%) and postpartum haemorrhage (table 5).

Table 5.

Potentially life-threatening conditions among the referred women, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,2019

| Characteristics*, n=80 | n (%) |

| Haemorrhagic complications | |

| Antepartum haemorrhage | 13 (16.3) |

| Postpartum haemorrhage | 15 (18.8) |

| Ruptured uterus | 1 (1.25) |

| Coagulopathy | 2 (2.5) |

| Hypertensive disorders | |

| Severe hypertension/pre-eclampsia | 50 (62.5) |

| Eclampsia | 9 (11.3) |

| HELLP syndrome | 2 (2.5) |

| Others | |

| Pulmonary oedema | 1 (1.25) |

| Shock | 1 (1.25) |

| Thrombocytopaenia | 2 (2.5) |

| Management indication of severity | |

| Transfusion of blood derivatives | 17 (21.3) |

| Major surgical intervention (hysterectomy) | 1 (1.25) |

*Multiple responses possible.

HELLP, Haemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzyme, Low platlets.

Discussion

All three types of delays were common in the study hospitals, the most severe being delay within the receiving hospital. The third delay was significantly associated with SMO.

Studies have found that distance to facilities is a clear barrier to women accessing health facilities,17 18 but in Addis Ababa proximity to services does not appear to be a problem as the median distance to a facility that provides surgical services is 5 km, well below the national average of 45 km.19 Two-fifths of women experienced second delay. Compared with other studies, this may be low; however, this proportion of second delay is not expected because referring facilities/catchment health centres are near the receiving hospitals and are expected to refer by ambulance.20

This study showed that the rate of occurrence of SMO indicators was higher than the findings of an earlier study done in other parts of the country20–23 and in other countries.24–26 This high proportion of SMO might be due to the fact that our study selected facilities that are referral hospitals and that are serving complicated cases as well as cases referred from other health facilities that were beyond their capacity or that needed further interventions. This study showed that direct obstetric causes were the most common leading factors of SMO, and the most common diagnoses were postpartum haemorrhage (52%), followed by eclampsia (31%), with the most common intervention being blood transfusion (58.6%). Obstetric haemorrhage and hypertensive disorders (eclampsia, haematological coagulation and pulmonary oedema) were found to be the top underlying complications among cases of SMO; similarly, hypertensive disorders and obstetric haemorrhage were the most common underlying causes of PLTC. This is comparable with the findings from studies in other parts of the country23–25 and in other countries,25–29 including sub-Saharan countries.30 31

Emergency obstetric care use by pregnant women is influenced by a complex interaction of factors leading to delay in decision-making, access to services and receipt of proper care once a health facility is reached.30 31 Receiving appropriate care once they have reached the health facility (third delay) was the most common (58.6%), followed by delay in seeking care (first delay) (51.7%), and then reaching the appropriate health facility (second delay) (44.8%); these were identified among the SMOs, and more than half (58.6%) of SMO cases had encountered at least one of the delays, similar to a study done elsewhere in the country21 32 33; however, the first and second delays were seen less frequently compared with the findings from other countries.25 30 31 34–37 This can be justified by the overloaded cases, limited hospital capacity, differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population and the proximity of health facilities.

In this study, failure to receive appropriate care after reaching the health facility (third delay) was found to have the strongest association with SMO, with a twofold increase in risk. This supports the WHO hypothesis relating a high case fatality in the hospital as an indicator for the presence of delay in receiving adequate and proper treatment,17 and it indicates poor performance of obstetric services.38 39 An incapacitated health facility and system with poor leadership (mismanagement of hospital resources, poor coordination and lack of understanding of obstetric emergencies) contributes to significant delay after women have reached a health facility. These factors have been reported in several studies as significant contributors to delay.21 32 34 35 In a study in Tigray, 88% of all maternal deaths were attributed to health system failure.33 In our study, health system-related factors were a possible reason for the third delay in 59% of SMO cases and maternal deaths.

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted at two referral hospitals which often receive complicated cases and referred women with complications, and the results might not be representative of other institutions and the community. In addition, cases might have been missed as some women may have transferred to health centres and other hospitals after delivery for different reasons.

However, we believe that this study provides data on the extent of delays as well as the SMO and its indicators experienced by women who were referred for an emergency delivery. In fact, if the delay is so severe in these well-established referral centres, one may expect it to be worse in some not well-staffed and well-equipped centres. We decided to focus on women with SMO rather than the less severe forms of obstetric complications since their conditions put them at the highest risk for maternal deaths.

Conclusion

The burden of SMO due to preventable and/or treatable direct obstetric causes is high. Majority of the women in this study had serious delays both in making decisions to seek care for birth and in actually receiving care once at the hospital. We recommend strengthening health referral systems and addressing specific health system bottlenecks during labour and delivery in order to ensure no woman is endangered. We also recommend conducting a qualitative method of study (including focus group discussion and indepth interview) and observing tertiary hospitals’ set-up and readiness to manage high-risk pregnancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the residents and interns of Addis Ababa University College of Health Sciences, without their support on data collection this research may not have reached this stage.

Footnotes

Contributors: EMA: design of the work, drafting of the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and write-up of the manuscript. YB: advised on the scope of the paper, drafting of the manuscript and revised it critically for important intellectual content. Both authors approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was received from both the Addis Continental Institute of Public Health and the Addis Ababa Health Bureau ethical review board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository. Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad Data Repository at http://datadryad.org/ (doi: 10.5061/dryad.x95x69pfh).

References

- 1.WHO Trends in maternal mortality: 2000 to 2017. Geneva: WHO, 2019. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal-mortality-2000-2017/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Maternal mortality; fact sheets, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Maternal mortality. fact sheet. Media Centre., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) True magnitude of stillbirths and maternal and neonatal deaths underreported. Media Center, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussein J, Kanguru L, Astin M, et al. . The effectiveness of emergency obstetric referral interventions in developing country settings: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001264. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knight HE, Self A, Kennedy SH. Why are women dying when they reach hospital on time? A systematic review of the 'third delay'. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63846. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.JSI Research and Training Institute The last 10 Kilometers (L10K). emergency referral for pregnant women and newborns: a rapid community and health system assessment. Addis Ababa: BETA Development Consulting Firm, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onwudiegwu U, Ezechi OC. Emergency obstetric admissions: late referrals, misdiagnoses and consequences. J Obstet Gynaecol 2001;21:570–5. 10.1080/01443610120085492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bossyns P, Abache R, Abdoulaye MS, et al. . Monitoring the referral system through benchmarking in rural niger: an evaluation of the functional relation between health centres and the district hospital. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:51. 10.1186/1472-6963-6-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giovine A, Ostrowski C. Technical report on improving transportation and referral for maternal health: knowledge gaps and recommendations. Wilson Center, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group . Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006;368:1189–200. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qureshi RN, Sikandar R, Hoodbhoy Z, et al. . Referral pattern of emergencies in obstetrics: implications for defining scope of services and policy. J Pak Med Assoc 2016;66:1606–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelissen E, Mduma E, Broerse J, et al. . Applicability of the WHO maternal near miss criteria in a low-resource setting. PLoS One 2013;8:e61248. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization Evaluating the quality of care for severe pregnancy complications: the WHO near-miss approach for maternal health. Geneva: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:344–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNamee P, Ternent L, Hussein J. Barriers in accessing maternal healthcare: evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2009;9:41–8. 10.1586/14737167.9.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrysch S, Campbell OMR, Oona MR. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:34. 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Federal Ministry of Health, Addis Ababa Regional Health Bureau Emergency obstetric and newborn care services: standard operation manual for activities of catchment teams in Addis Ababa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dile M, Abate T, Seyum T. Proportion of maternal near misses and associated factors in referral hospitals of Amhara regional state, Northwest Ethiopia: institution-based cross-sectional study. GynecolObstet 2015;5:308. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woldeyes WS, Asefa D, Muleta G. Incidence and determinants of severe maternal outcome in Jimma university teaching Hospital, south-west Ethiopia: a prospective cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:255. 10.1186/s12884-018-1879-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebrehiwot Y, Tewolde BT. Improving maternity care in Ethiopia through facility based review of maternal deaths and near misses. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;127:S29–34. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liyew EF, Yalew AW, Afework MF, et al. . Incidence and causes of maternal near-miss in selected hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179013. 10.1371/journal.pone.0179013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabir M, Abdul-Salam I, Suheil DM, et al. . Maternal near miss and quality of maternal health care in Baghdad, Iraq. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:11. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chavane LA, Bailey P, Loquiha O, et al. . Maternal death and delays in accessing emergency obstetric care in Mozambique. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:71. 10.1186/s12884-018-1699-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazhar SB, Batool A, Emanuel A, et al. . Severe maternal outcomes and their predictors among Pakistani women in the who multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;129:30–3. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tunçalp Özge, Hindin MJ, Adu-Bonsaffoh K, et al. . Assessment of maternal near-miss and quality of care in a hospital-based study in Accra, Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;123:58–63. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Say L, Souza JP, Pattinson RC, et al. . Maternal near miss--towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009;23:287–96. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelissen EJT, Mduma E, Ersdal HL, et al. . Maternal near miss and mortality in a rural referral hospital in northern Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:141. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oladapo OT, Adetoro OO, Ekele BA, et al. . When getting there is not enough: a nationwide cross-sectional study of 998 maternal deaths and 1451 near-misses in public tertiary hospitals in a low-income country. BJOG 2016;123:928–38. 10.1111/1471-0528.13450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaye DK, Kakaire O, Osinde MO. Systematic review of the magnitude and case fatality ratio for severe maternal morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa between 1995 and 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:65. 10.1186/1471-2393-11-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geleto A, Chojenta C. Barriers to access and utilization of emergency obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa—a systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hailu S, Enqueselassie F, Berhane Y. Health facility-based maternal death audit in Tigray, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 2009;23:115–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pacagnella RC, Cecatti JG, Osis MJ, et al. . The role of delays in severe maternal morbidity and mortality: expanding the conceptual framework. Reprod Health Matters 2012;20:155–63. 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39601-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pacagnella RC, Cecatti JG, Parpinelli MA, et al. . Delays in receiving obstetric care and poor maternal outcomes: results from a national multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:159. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Assarag B, Dujardin B, Delamou A, et al. . Determinants of maternal near-miss in Morocco: too late, too far, too sloppy? PLoS One 2015;10:e0116675. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodman DM, Srofenyoh EK, Olufolabi AJ, et al. . The third delay: understanding waiting time for obstetric referrals at a large regional hospital in Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:216. 10.1186/s12884-017-1407-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yunus S, Kauser S, Ali S. Three ‘delays’ as a framework for critical analysis of maternal near miss and maternal mortality. J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;5:57–9. 10.5005/jp-journals-10006-1224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Filippi V, Ronsmans C, Gohou V, et al. . Maternity wards or emergency obstetric rooms? incidence of near-miss events in African hospitals. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2005;84:11–16. 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.