Abstract

We used data from the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials to investigate the natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases (ILDs).

Subjects in the two INPULSIS trials had a clinical diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) while subjects in the INBUILD trial had a progressive fibrosing ILD other than IPF and met protocol-defined criteria for ILD progression despite management. Using data from the placebo groups, we compared the rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) (mL·year−1) and mortality over 52 weeks in the INBUILD trial with pooled data from the INPULSIS trials.

The adjusted mean annual rate of decline in FVC in the INBUILD trial (n=331) was similar to that observed in the INPULSIS trials (n=423) (−192.9 mL·year−1 and −221.0 mL·year−1, respectively; nominal p-value=0.19). The proportion of subjects who had a relative decline in FVC >10% predicted at Week 52 was 48.9% in the INBUILD trial and 48.7% in the INPULSIS trials, and the proportion who died over 52 weeks was 5.1% in the INBUILD trial and 7.8% in the INPULSIS trials. A relative decline in FVC >10% predicted was associated with an increased risk of death in the INBUILD trial (hazard ratio 3.64) and the INPULSIS trials (hazard ratio 3.95).

These findings indicate that patients with fibrosing ILDs other than IPF, who are progressing despite management, have a subsequent clinical course similar to patients with untreated IPF, with a high risk of further ILD progression and early mortality.

Short abstract

Analyses of data from the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials suggest that progressive fibrosing ILDs other than IPF have a clinical course similar to IPF, irrespective of underlying ILD diagnosis or the fibrotic pattern on HRCT http://bit.ly/3apG0Q5

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is, by definition, a progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease (ILD) [1]. In addition to IPF, there are a number of other ILDs that may develop a progressive fibrosing phenotype characterised by declining lung function, an increasing extent of fibrosis on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), worsening symptoms and quality of life, and early mortality [2–5]. Along with these clinical similarities, progressive fibrosing ILDs appear to share pathobiological mechanisms that may represent a common fibrotic response to tissue injury [6–10].

The ILDs that can be complicated by progressive fibrosis include idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (iNSIP) [11], unclassifiable idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) [12], hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) [13], autoimmune ILDs such as rheumatoid arthritis-associated ILD (RA-ILD) [14] and systemic sclerosis-associated ILD (SSc-ILD) [15], sarcoidosis [16] and occupation-associated lung disease [17]. Similar to IPF, a decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) is predictive of mortality in patients with these other fibrosing ILDs [18–22]. Given their clinical and pathophysiological similarities, and the rarity of the individual diseases, it has been proposed that fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype be “lumped” together for the purposes of investigating certain potential therapies [3, 23, 24].

Nintedanib is an intracellular inhibitor of tyrosine kinases [10, 25]. In the two INPULSIS trials in patients with IPF, nintedanib reduced the rate of decline in FVC (mL·year−1) over 52 weeks by about 50% compared to placebo [26]. Recently, the efficacy and safety of nintedanib in subjects with a variety of ILD diagnoses other than IPF, grouped based on the progressive clinical behaviour of their fibrosing ILD despite management deemed appropriate in clinical practice, were investigated in the INBUILD trial. The results showed that, as in the INPULSIS trials, nintedanib reduced the rate of decline in FVC (mL·year−1) over 52 weeks by about 50% compared to placebo [27]. We used data from subjects who received placebo in the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials to investigate the natural history of progressive fibrosing ILDs. Specifically, we wanted to compare the clinical course of IPF and other progressive fibrosing ILDs, explore whether specific ILD diagnoses were associated with different rates of progression and investigate whether a relative decline in FVC was associated with mortality in patients with IPF and other progressive fibrosing ILDs.

Materials and methods

Trial design

The two INPULSIS trials and the INBUILD trial were randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with a 52-week treatment period. The trial designs have been described and the trial protocols are publicly available [26, 27]. The trials were carried out in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Harmonised Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice of the International Conference on Harmonisation, and were approved by the local authorities. Subjects provided written informed consent before trial entry. In all these trials, the primary endpoint was the annual rate of decline in FVC (mL·year−1), assessed over 52 weeks.

INPULSIS trials

Briefly, subjects in the INPULSIS trials were aged ≥40 years and had a clinical diagnosis of IPF. To be eligible for inclusion based on an HRCT scan (taken within the previous ≤12 months), patients had to have a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)-like fibrotic pattern defined as meeting criteria A, B and C, A and C, or B and C defined as follows: A: definite honeycomb lung destruction with basal and peripheral predominance; B: presence of reticular abnormality and traction bronchiectasis consistent with fibrosis with basal and peripheral predominance; C: atypical features are absent, specifically nodules and consolidation. Ground glass opacity, if present, was to be less extensive than reticular opacity pattern. Subjects had an FVC ≥50% predicted and a diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) ≥30% predicted and <80% predicted. There were no inclusion criteria regarding longitudinal disease behaviour. Subjects were randomised 3:2 to receive nintedanib or placebo.

INBUILD trial

Subjects in the INBUILD trial were aged ≥18 years and had a fibrosing ILD other than IPF diagnosed by the investigator according to their usual clinical practice. Patients with IPF were actively excluded. For every subject, the investigator documented an ILD diagnosis on the case report form based on the following nine options: iNSIP, unclassifiable IIP, HP, RA-ILD, mixed connective tissue disease-associated ILD (MCTD-ILD), SSc-ILD, exposure-related ILD, sarcoidosis and other fibrosing ILD. Subjects had features of fibrosing lung disease (reticular abnormality with traction bronchiectasis with or without honeycombing) with an extent of >10% on an HRCT scan (taken within the previous ≤12 months), confirmed by central review, FVC ≥45% predicted and DLCO ≥30% predicted and <80% predicted.

Subjects had to meet one of the following criteria for disease progression in the 24 months before screening, as determined by the investigator, despite management as deemed appropriate in clinical practice for the individual ILD: 1) a relative decline in FVC ≥10% predicted; 2) a relative decline in FVC ≥5% predicted but <10% predicted and worsened respiratory symptoms; 3) a relative decline in FVC ≥5% predicted but <10% predicted and increased extent of fibrosis on HRCT; 4) worsened respiratory symptoms and increased extent of fibrosis on HRCT.

Subjects were randomised 1:1 to receive nintedanib or placebo. Randomisation was stratified according to the fibrotic pattern on HRCT (UIP-like fibrotic pattern or other fibrotic patterns). The criteria used to identify a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT in the INBUILD trial were the same as the criteria used in the INPULSIS trials. For each subject, the trial consisted of two parts: Part A, which comprised 52 weeks of treatment; and Part B, a variable treatment period beyond Week 52 during which subjects continued to receive blinded treatment until all subjects had completed Part A. Subjects who discontinued treatment were asked to attend all visits as originally planned, including an end-of-treatment visit and a follow-up visit 4 weeks later. The second database lock took place after all patients had completed the follow-up visit or had entered the open-label extension study. The protocol did not allow for use of azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, or oral corticosteroids >20 mg·day−1 at randomisation, but initiation of these medications was allowed after 6 months of study treatment in cases of clinically significant deterioration of ILD or connective tissue disease, at the discretion of the investigator.

Analyses

The course of ILD was assessed in subjects who received placebo in the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials. The following were used as measures of longitudinal disease behaviour: annual rate of decline in FVC (mL·year−1), observed absolute change from baseline in FVC (mL) over time, the proportions of subjects with relative declines in FVC of >5% predicted and >10% predicted at Week 52, and all-cause mortality.

To address the question of similarity between IPF and other fibrosing ILDs with a progressive phenotype, data from the placebo group in the overall population in the INBUILD trial were compared with pooled data from the placebo groups of the INPULSIS trials. In addition, the subgroups of subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT and with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT in the INBUILD trial were compared with patients with IPF in the INPULSIS trials.

To assess whether specific ILD diagnoses were associated with different rates of progression, the course of ILD in the placebo group of the INBUILD trial was assessed in the following five diagnostic groups: iNSIP, unclassifiable IIP, HP, autoimmune ILDs (RA-ILD, SSc-ILD, MCTD-ILD, plus subjects with an autoimmune disease noted in the “Other fibrosing ILDs” category of the case report form) and other ILDs (sarcoidosis, exposure-related ILDs and selected diagnoses from “Other fibrosing ILDs”). Nominal p-values for subgroup-by-time interaction were obtained from tests of heterogeneity across all the diagnostic groups, with no adjustment for multiplicity.

The annual rate of decline in FVC (mL·year−1) was analysed using a similar random coefficient regression model (with random slopes and intercepts) as was used in the primary analysis of the INBUILD trial, including baseline FVC (mL) and patient population (IPF versus non-IPF) as covariates. The analysis was based on all measurements obtained over the first 52 weeks, including those from subjects who had prematurely discontinued placebo. The model allowed for missing data assuming that they were missing at random. In this paper, we present results that are representative of an “average subject” within the depicted comparison. To evaluate time to death, a log-rank test was utilised and included patient population (IPF versus non-IPF) as a covariate. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to derive the hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) between the patient populations (IPF versus non-IPF). Categorical relative declines in % predicted FVC were evaluated using a logistic regression model adjusting for the continuous covariate baseline % predicted FVC and for the patient population (IPF versus non-IPF). Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were used to quantify the effects within each patient population. Subjects with missing data at Week 52 were counted as having relative declines in FVC of >5% predicted or >10% predicted, representing a “worst case” analysis.

To explore the question of whether a relative decline in FVC >10% predicted was associated with mortality, we analysed the relationship between a relative decline in FVC of >10% predicted and time to death over 52 weeks in the INBUILD trial and in the INPULSIS trials, and using data up to the second database lock in the INBUILD trial. Evaluations regarding the association of FVC decline with mortality were based on a Cox proportional hazards model, where time to FVC decline >10% predicted was included as a time-dependent variable using the programming statements method [28]. The assessment in the overall population in the INBUILD trial also included the stratification variable (UIP-like fibrotic pattern versus other fibrotic patterns on HRCT). No other variables were included in these evaluations.

Results

Subjects

The baseline characteristics of subjects in the placebo groups of the INBUILD trial (n=331) and INPULSIS trials (n=423) are summarised in table 1. At baseline, mean % predicted FVC was lower in the INBUILD trial than in the INPULSIS trials (69% versus 79%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects in the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials

| Characteristic | INBUILD trial (overall population) | INPULSIS trials (pooled) | ||

| Nintedanib (n=332) | Placebo (n=331) | Nintedanib (n=638) | Placebo (n=423) | |

| Male sex | 179 (53.9) | 177 (53.5) | 507 (79.5) | 334 (79.0) |

| Age years | 65.2±9.7 | 66.3±9.8 | 66.6±8.1 | 67.0±7.9 |

| Former or current smoker | 169 (50.9) | 169 (51.1) | 464 (72.7) | 301 (71.2) |

| FVC mL | 2340±740 | 2321±728 | 2714±757 | 2728±810 |

| FVC % predicted | 68.7±16.0 | 69.3±15.2 | 79.7±17.6 | 79.3±18.2 |

| DLCO# % predicted | 44.4±11.9 | 47.9±15.0 | 47.4±13.5 | 47.0±13.4 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean±sd. DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FVC: forced vital capacity. #: corrected for haemoglobin level.

Annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity

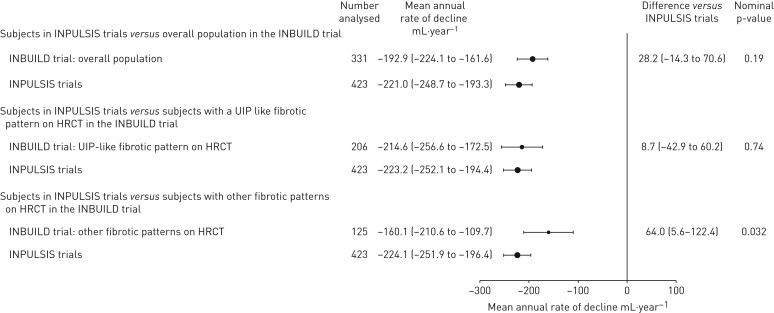

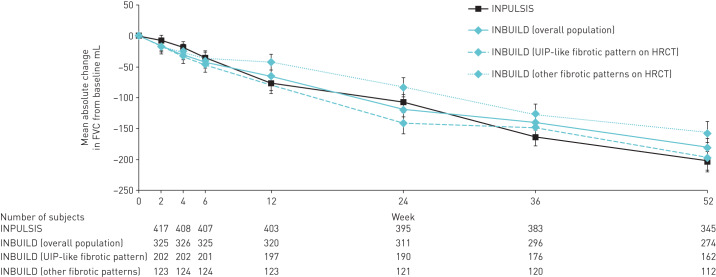

The adjusted mean annual rate of decline in FVC over 52 weeks in the placebo group of the overall population in the INBUILD trial was similar to that observed in the placebo group of the INPULSIS trials (−192.9 mL·year−1 and −221.0 mL·year−1, respectively; nominal p-value=0.19) (figure 1). Subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT in the INBUILD trial also had an adjusted annual rate of decline similar to that observed in the INPULSIS trials (−214.6 mL·year−1 and −223.2 mL·year−1, respectively; nominal p-value=0.74) (figure 1). The adjusted annual rate of decline in FVC in subjects with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT in the INBUILD trial was lower than that observed in the INPULSIS trials (−160.1 mL·year−1 versus −224.1 mL·year−1; nominal p-value=0.032) (figure 1). The curves of observed change from baseline in FVC (mL) over 52 weeks in the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials had similar trajectories (figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) over 52 weeks in the placebo groups of the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials. The adjusted mean rate of decline in FVC depicted here is representative of an “average subject” within the depicted comparison. The baseline FVC value was computed as the mean baseline FVC of all the subjects from the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials that were used in the respective comparison. Data are presented as n or mean (95% CI). CI: confidence interval; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 2.

Observed change in forced vital capacity (FVC) from baseline (mean (se)) over 52 weeks in the placebo groups of the INPULSIS and INBUILD trials. HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia.

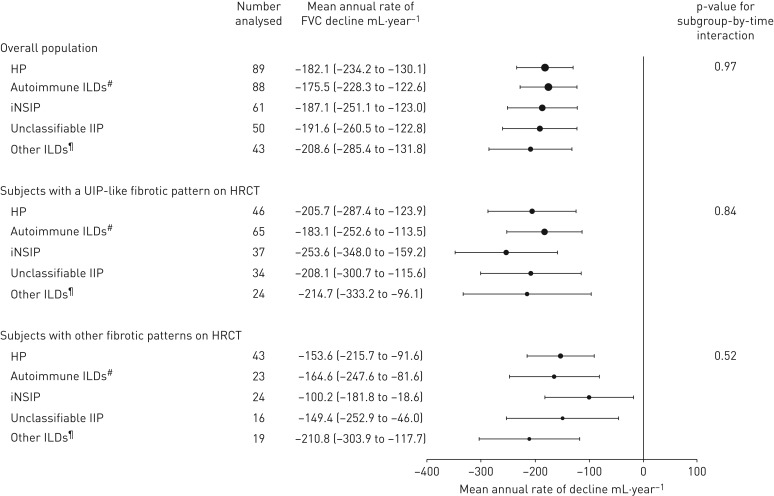

In the INBUILD trial, the annual rate of decline in FVC was similar across the five pre-specified groups by ILD diagnosis; in all the subgroups, subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT had a numerically greater annual rate of decline in FVC than those with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT (figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) over 52 weeks in the placebo groups of the INBUILD trial by interstitial lung disease (ILD) diagnosis. Data are presented as n or mean (95% CI). HP: hypersensitivity pneumonitis; iNSIP: idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia; IIP: idiopathic interstitial pneumonia; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; CI: confidence interval. #: rheumatoid arthritis-associated ILD, systemic sclerosis-associated ILD, mixed connective tissue disease-associated ILD, plus autoimmune ILDs in the “Other fibrosing ILDs” category of the case report form; ¶: sarcoidosis, exposure-related ILDs and other terms in the “Other fibrosing ILDs” category of the case report form.

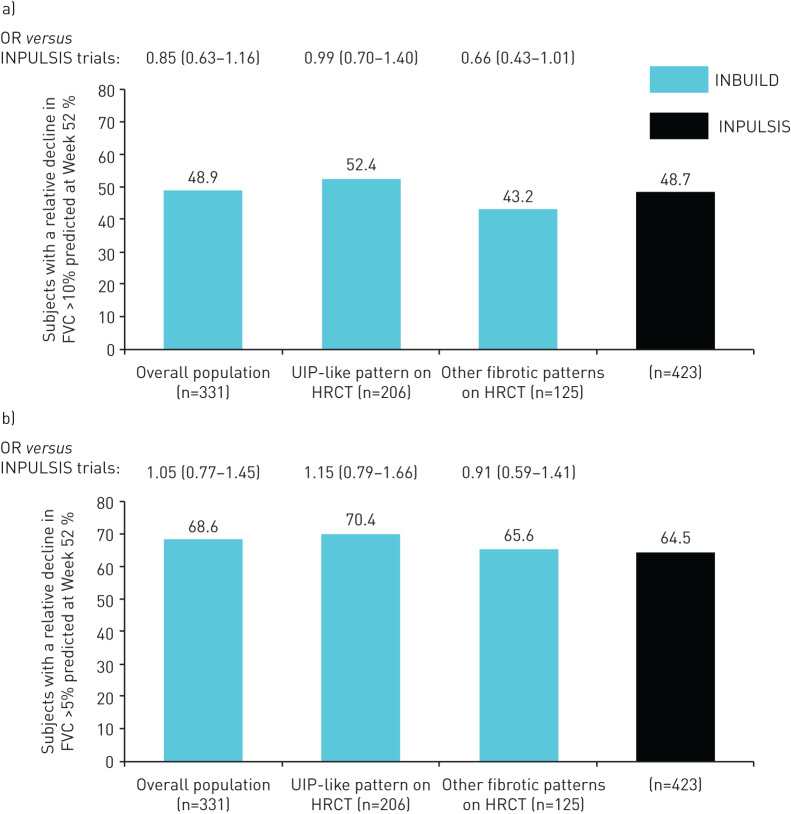

Proportions of subjects who had categorical relative declines in % predicted forced vital capacity

The proportions of subjects who had relative declines from baseline in FVC >10% predicted or >5% predicted at Week 52 were similar between the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials (figures 4a and 4b). A relative decline in FVC >10% predicted at Week 52 was observed in 48.9% of the overall population in the INBUILD trial and 48.7% of subjects in the INPULSIS trials. In the INBUILD trial, a relative decline in FVC >10% predicted at Week 52 was observed in a greater proportion of subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT than in those with other fibrotic patterns (52.4% versus 43.2%) (figure 4a). A relative decline in FVC >5% predicted at Week 52 was observed in 68.6% of the overall population in the INBUILD trial and 64.5% of subjects in the INPULSIS trials (figure 4b). In the INBUILD trial, the proportion of subjects with a relative decline in FVC >5% predicted at Week 52 was similar in subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT and in those with other fibrotic patterns (70.4% and 65.6%, respectively) (figure 4b).

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of subjects who had (a) a relative decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) >10% predicted at Week 52 and (b) a relative decline in FVC >5% predicted at Week 52 in the placebo groups of the INPULSIS and INBUILD trials. Data are expressed as % or OR (95% CI). OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography.

Mortality and its association with relative decline of >10% predicted in forced vital capacity

Over 52 weeks, deaths occurred in 34 subjects in the INBUILD trial (5.1%) and 33 subjects in the INPULSIS trials (7.8%). Compared with the INPULSIS trials, the proportion of subjects who died over 52 weeks in the INBUILD trial was similar in the overall population and in subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern, and lower in those with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT (hazard ratios versus INPULSIS 0.63, 0.97 and 0.10, respectively) (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Proportion of subjects who died over 52 weeks in the placebo groups of the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials

| INBUILD trial | INPULSIS trials (n=423) | |||

| Overall population (n=331) | UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT (n=206) | Other fibrotic patterns on HRCT (n=125) | ||

| Deaths over 52 weeks | 17 (5.1) | 16 (7.8) | 1 (0.8) | 33 (7.8) |

| Hazard ratio versus INPULSIS trials# | 0.63 (0.35–1.13) | 0.97 (0.53–1.76) | 0.10 (0.01–0.70) | |

| Nominal p-value¶ | 0.12 | 0.92 | 0.004 | |

Data are presented as n (%) or hazard ratio (95% CI), unless otherwise stated. UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; CI: confidence interval. #: based on a Cox regression model with terms for patient population (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) versus non-IPF); ¶: based on a log-rank test.

In the INBUILD trial, a relative decline in FVC of >10% predicted was associated with an increased risk of death over 52 weeks in the overall population and in subjects with a UIP-like pattern on HRCT (hazard ratios 3.64 and 3.35, respectively). A similar association was observed in the INPULSIS trials (hazard ratio 3.95) (table 3). As only one death occurred over 52 weeks in subjects with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT in the INBUILD trial, the hazard ratio could not be calculated. Using data up to the second database lock (median follow-up of approximately 19 months), a relative decline in FVC of >10% predicted was associated with an increased risk of death in the overall population (hazard ratio 3.48) and in subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT (hazard ratio 3.64). A similar trend was observed in subjects with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT (hazard ratio 2.88) (table 4).

TABLE 3.

Relationship between relative decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) >10% predicted and time to death over 52 weeks in the placebo groups of the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials

| INBUILD trial# | INPULSIS trials (n=423) | ||

| Overall population (n=331) | UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT (n=206) | ||

| Deaths over 52 weeks | 17 (5.1) | 16 (7.8) | 33 (7.8) |

| Relationship¶ | |||

| Hazard ratio+ | 3.64 (1.29–10.28) | 3.35 (1.16–9.64) | 3.95 (1.87–8.33) |

| p-value§ | 0.015 | 0.025 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or hazard ratio (95% CI), unless otherwise stated. UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; HRCT: high resolution computed tomography; CI: confidence interval. #: as the number of subjects with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT who died was one, the relationship between a relative decline in FVC >10% predicted and mortality could not be analysed; ¶: relationship between relative decline in FVC >10% predicted and time to death; +: based on a Cox regression model with relative decline in FVC >10% predicted as a time-dependent variable; §: based on a Wald test.

TABLE 4.

Relationship between relative decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) >10% predicted and time to death up to the second database lock# in the placebo group of the INBUILD trial

| Overall population (n=331) | Subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT (n=206) | Subjects with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT (n=125) | |

| Deaths up to second database lock# | 45 (13.6) | 36 (17.5) | 9 (7.2) |

| Relationship¶ | |||

| Hazard ratio+ | 3.48 (1.71–7.10) | 3.64 (1.65–8.06) | 2.88 (0.59–14.09) |

| p-value§ | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.192 |

Data are presented as n (%) or hazard ratio (95% CI), unless otherwise stated. UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; CI: confidence interval. #: the second database lock took place after all patients had completed the follow-up visit or had entered the open-label extension study. The median follow-up was approximately 19 months. Analysis over a similar time period in the INPULSIS trials was not possible as they were 52-week trials; ¶: relationship between relative decline in FVC >10% predicted and time to death; +: based on a Cox regression model with relative decline in FVC >10% predicted as a time-dependent variable. The assessment in the overall population also included the stratification variable (UIP-like fibrotic pattern versus other fibrotic patterns on HRCT); §: based on a Wald test.

Discussion

We used data from the placebo groups of the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials to investigate the natural history of progressive fibrosing ILDs. We found that subjects in the INBUILD trial who had diagnoses of a fibrosing ILD other than IPF and met criteria for ILD progression in the previous 24 months, based on decline in lung function or worsening of symptoms and fibrotic changes on HRCT despite management deemed appropriate in clinical practice, had a disease course similar to that of subjects with IPF. Rates of FVC decline and mortality over 52 weeks were comparable between the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials.

Previous studies have suggested that in patients with fibrosing ILDs the presence of a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT is associated with more rapid disease progression [29–33]. Consistent with these findings, the rates of FVC decline and mortality over 52 weeks in the INBUILD trial were greater in subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT than in subjects with other fibrotic patterns. That said, the rate of FVC decline in subjects with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT was dramatic (160 mL·year−1), with almost 50% of these subjects showing a relative decline in FVC >10% predicted over 52 weeks, similar to patients with IPF.

Although the INBUILD trial was not designed or powered to study the effects of nintedanib in patients with specific ILD diagnoses, our results suggest that in subjects with a >10% extent of fibrosis on HRCT and clinical signs of progression despite management, the rate of decline in FVC was similar across subgroups with different diagnoses. This suggests that although it is critical that patients receive an accurate diagnosis of ILD at the time of presentation in order to inform optimal management, observation of disease behaviour can identify a population of patients who develop a progressive fibrosing phenotype despite treatment and are therefore at high risk of further progression.

Declines in FVC of >10% predicted and >5% predicted have been associated with mortality in patients with IPF [34, 35] and other chronic fibrosing ILDs [19–22]. The subjects enrolled in the INBUILD trial met protocol-defined criteria for progression of ILD in the 2 years before screening. The subjects with IPF enrolled in the INPULSIS trials were not required to meet criteria for disease progression in order to enter the trial, as IPF is by definition a progressive disease [1]. In both the INBUILD and INPULSIS trials, approximately half the subjects in the placebo group had a relative decline in FVC of >10% predicted and two-thirds had a relative decline of >5% predicted over 52 weeks. In the INBUILD trial, a relative decline in FVC of >10% predicted was associated with a more than three-fold increase in the risk of death over 52 weeks, both in the overall population and in subjects with a UIP-like fibrotic pattern on HRCT, which was comparable to what was observed in the INPULSIS trials. Over a longer observation period, this association also became apparent in subjects with other fibrotic patterns on HRCT. These data suggest that, in a similar fashion to IPF, a decline in FVC is associated with an increased risk of early death in patients with non-IPF fibrosing ILDs that have progressed despite management.

Previous analyses of the INBUILD trial have shown that the effect of nintedanib versus placebo on the rate of FVC decline was consistent across subpopulations by HRCT pattern [27] and by ILD diagnosis [36]. Combined with our current results, these findings provide further support for a progressive fibrosing phenotype in ILD, characterised by progressive decline in lung function and early mortality, irrespective of the underlying ILD diagnosis and fibrotic pattern on HRCT. These findings also support the “lumping” together of patients with progressive fibrosing ILDs for the purposes of investigating certain therapies for these rare diseases, as has previously been proposed [3].

In conclusion, our findings show that the subjects with non-IPF progressive fibrosing ILDs who received placebo in the INBUILD trial had a clinical course similar to patients with untreated IPF, irrespective of the underlying ILD diagnosis or the fibrotic pattern on HRCT. Patients with fibrosing ILDs other than IPF who have shown progression of ILD in the past 24 months, despite management deemed appropriate in clinical practice, are at high risk of further ILD progression and early mortality.

Shareable PDF

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and investigators who participated in these trials. Writing assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided during the development of this manuscript by Elizabeth Ng and Wendy Morris of Fleishman Hillard Fishburn (London, UK). The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved at all stages of development and provided their approval on the final version.

Footnotes

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00894-2020

These studies are registered as clinical trials at ClinicalTrials.gov with identifier numbers NCT02999178, NCT01335464 and NCT01335477. Data are available upon on request. A request can be submitted via https://trials.boehringer-ingelheim.com/trial_results/clinical_submission_documents.html

Author contributions: K.K. Brown, A.U. Wells, S.L.F. Walsh, R. Schlenker-Herceg, E. Clerisme-Beaty, K. Tetzlaff and V. Cottin were involved in the design of the study. R-G. Goeldner was involved in the data analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data and in the writing and critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest: K.K. Brown reports grants from NHLBI; personal fees from Biogen, Blade Therapeutics, Galapagos, Galecto Biotech, Huitai Biomedicine, Lifemax, Lilly, MedImmune, monARC Bionetworks, Pliant Therapeutics, ProMetic, Third Pole Therapeutics, Theravance, Three Lakes Partners, and Veracyte; personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim; and other support from Genoa and the Open Source Imaging Consortium (OSIC).

Conflict of interest: F.J. Martinez reports grants, personal fees, non-financial support and other support from Boehringer Ingelheim; personal fees, nonfinancial support and other support from AstraZeneca; non-financial support and other support from ProterixBio; personal fees and non-financial support from the Canadian Respiratory Network, Chiesi, CME Outfitters, Dartmouth, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Inova Fairfax Health System, Miller Communications, the National Association for Continuing Education, Novartis, Pearl Pharmaceuticals, PeerView Communications, Physicians Education Resource, Potomac, Prime Communications, the Puerto Rican Respiratory Society, Sunovion, Teva, Theravance, the University of Alabama Birmingham, and Vindico; personal fees and other support from Patara/Respivant; grants from NIH; personal fees from the American Thoracic Society, Columbia University, France Foundation, MD Magazine, Methodist Hospital Brooklyn, New York University, Physicians Education Resource, Rare Disease Healthcare Communications, Rockpointe, UpToDate, and WebMD/Medscape; other support from Afferent/Merck, Bayer, Biogen, Bridge Biotherapeutics, Gala Pharmaceutical, Promedior, Wolters Kluwer, and Veracyte; and non-financial support from Gilead, Nitto, Prometic, and Zambon.

Conflict of interest: S.L.F. Walsh reports personal fees for consultancy from Sanofi-Aventis, Galapagos and OSIC, personal fees for advisory board work from Roche, grants and personal fees for steering committee work from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees for lectures from Bracco, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: V.J. Thannickal reports personal fees for consultancy from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Kadmon Corporation, Pliant, Glenmark, Covance, Blade, Versant Venture, Mistral and Translate Bio, grants from Genkyotex, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: A. Prasse reports that Hannover Medical School received a fee for patient randomisation into the INBUILD study from Boehringer Ingelheim; personal fees for consultancy and lectures and non-financial support (travel expenses) from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, personal fees for lectures and non-financial support (travel expenses) from Novartis, AstraZeneca and Chiesi, personal fees for consultancy and non-financial support (travel expenses) from Nitto Denko and Pliant, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: R. Schlenker-Herceg is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Conflict of interest: R-G. Goeldner is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co., KG.

Conflict of interest: E. Clerisme-Beaty is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Conflict of interest: K. Tetzlaff is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH.

Conflict of interest: V. Cottin reports personal fees for advisory board work and lectures, and non-financial support for meeting attendance from Actelion, grants, personal fees for advisory board work and lectures, and non-financial support for meeting attendance from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, personal fees for advisory board work and data monitoring committee work from Bayer/MSD, Promedior and Galapagos, personal fees for adjudication committee work from Gilead, personal fees for advisory board work and lectures from Novartis, personal fees for lectures from Sanofi, personal fees for data monitoring committee work from Celgene and Galecto, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: A.U. Wells reports personal fees for consultancy and lectures from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche, personal fees for consultancy from Blade, outside the submitted work.

Support statement: The INPULSIS and INBUILD trials were funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 198: e44–e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 188: 733–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells AU, Brown KK, Flaherty KR, et al. What's in a name? That which we call IPF, by any other name would act the same. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1800692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cottin V, Wollin L, Fischer A, et al. Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: knowns and unknowns. Eur Respir Rev 2019; 28: 180100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolb M, Vašáková M. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respir Res 2019; 20: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thannickal VJ, Toews GB, White ES, et al. Mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Annu Rev Med 2004; 55: 395–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prasse A, Pechkovsky DV, Toews GB, et al. CCL18 as an indicator of pulmonary fibrotic activity in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56: 1685–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagnato G, Harari S. Cellular interactions in the pathogenesis of interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev 2015; 24: 102–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luckhardt TR, Thannickal VJ. Systemic sclerosis-associated fibrosis: an accelerated aging phenotype? Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015; 27: 571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wollin L, Distler JHW, Redente EF, et al. Potential of nintedanib in treatment of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1900161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MY, Song JW, Do KH, et al. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: changes in high-resolution computed tomography on long-term follow-up. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2012; 36: 170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guler SA, Ellison K, Algamdi M, et al. Heterogeneity in unclassifiable interstitial lung disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 854–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Sadeleer LJ, Hermans F, de Dycker E, et al. Effects of corticosteroid treatment and antigen avoidance in a large hypersensitivity pneumonitis cohort: a single-centre cohort study. J Clin Med 2018; 8: E14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doyle TJ, Dellaripa PF. Lung manifestations in the rheumatic diseases. Chest 2017; 152: 1283–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guler SA, Winstone TA, Murphy D, et al. Does systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease burn out? Specific phenotypes of disease progression. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 1427–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh SL, Wells AU, Sverzellati N, et al. An integrated clinicoradiological staging system for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a case-cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khalil N, Churg A, Muller N, et al. Environmental, inhaled and ingested causes of pulmonary fibrosis. Toxicol Pathol 2007; 35: 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jegal Y, Kim DS, Shim TS, et al. Physiology is a stronger predictor of survival of pathology in fibrotic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171: 639–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon JJ, Chung JH, Cosgrove GP, et al. Predictors of mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 588–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gimenez A, Storrer K, Kuranishi L, et al. Change in FVC and survival in chronic fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Thorax 2018; 73: 391–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goh NS, Hoyles RK, Denton CP, et al. Short-term pulmonary function trends are predictive of mortality in interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69: 1670–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volkmann ER, Tashkin DP, Sim M, et al. Short-term progression of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis predicts long-term survival in two independent clinical trial cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78: 122–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flaherty KR, Brown KK, Wells AU, et al. Design of the PF-ILD trial: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial of nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. BMJ Open Respir Res 2017; 4: e000212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torrisi SE, Kahn N, Wälscher J, et al. Possible value of antifibrotic drugs in patients with progressive fibrosing non-IPF interstitial lung diseases. BMC Pulm Med 2019; 19: 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wollin L, Wex E, Pautsch A, et al. Mode of action of nintedanib in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1434–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2071–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flaherty KR, Wells AU, Cottin V, et al. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1718–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Institute Inc SAS/STAT® 15.1 User's Guide Cary, SAS Institute Inc, 2018. https://support.sas.com/documentation/onlinedoc/stat/151/spp.pdf Date last accessed: April 14, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh SL, Sverzellati N, Devaraj A, et al. Connective tissue disease related fibrotic lung disease: high resolution computed tomographic and pulmonary function indices as prognostic determinants. Thorax 2014; 69: 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zamora-Legoff JA, Krause ML, Crowson CS, et al. Progressive decline of lung function in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69: 542–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salisbury ML, Gu T, Murray S, et al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: radiologic phenotypes are associated with distinct survival time and pulmonary function trajectory. Chest 2019; 155: 699–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adegunsoye A, Oldham JM, Bellam SK, et al. Computed tomography honeycombing identifies a progressive fibrotic phenotype with increased mortality across diverse interstitial lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019; 16: 580–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim EJ, Elicker BM, Maldonado F, et al. Usual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2010; 35: 1322–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.du Bois RM, Weycker D, Albera C, et al. Forced vital capacity in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Test properties and minimal clinically important difference. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184: 1382–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richeldi L, Ryerson CJ, Lee JS, et al. Relative versus absolute change in forced vital capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 2012; 67: 407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells AU, Flaherty KR, Brown KK, et al. Nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: subgroup analyses by interstitial lung disease diagnosis in the randomised, placebo-controlled INBUILD trial. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-00085-2020.Shareable (327.3KB, pdf)