Abstract

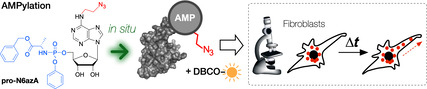

Conjugation of proteins to AMP (AMPylation) is a prevalent post‐translational modification (PTM) in human cells, involved in the regulation of unfolded protein response and neural development. Here we present a tailored pronucleotide probe suitable for in situ imaging and chemical proteomics profiling of AMPylated proteins. Using straightforward strain‐promoted azide–alkyne click chemistry, the probe provides stable fluorescence labelling in living cells.

Keywords: AMPylation, click chemistry, fluorescent probes, post-translational modifications, proteomics

Visualizing cytoplasmic dynamics: Protein AMPylation is a prevalent post‐translational modification in human cells, involved in the regulation of unfolded protein response and neural development. We present a tailored pronucleotide probe suitable for in situ imaging of AMPylated proteins. Using strain‐promoted azide–alkyne click cycloaddition, the probe enables stable fluorescence labelling in living cells.

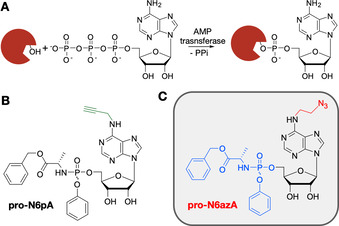

Protein AMPylation is a highly abundant post‐translational modification (PTM)1 regulating unfolded protein response (UPR),2, 3, 4 differentiation of neural progenitors and α‐synuclein modification.5, 6 AMPylation is catalyzed by AMP transferases (AMPylators), which transfer adenosine 5′‐O‐monophosphate from substrate ATP onto Ser, Thr or Tyr residues in target proteins (Scheme 1 A).1, 7 The only AMPylators in human cells identified so far are FICD and SELO.2, 3, 7 FICD contains an evolutionarily conserved catalytic Fic domain and an N‐terminal inhibition loop responsible for switches between the AMPylation and the deAMPylation activity of the enzyme.8, 9

Scheme 1.

Protein AMPylation and probes suitable for labelling in living cells. A) Schematic representation of protein AMPylation. B) Previously published probe pro‐N6pA. C) Structure of the probe pro‐N6azA introduced in this study.

Several methods have previously been employed for the investigation of protein AMPylation; they include the use of radiolabelled or isotope‐labelled ATP analogues10, 11 as well as approaches utilizing a N6pATP probe12 or anti‐AMP‐Thr/Tyr antibodies.13, 14 However, none of these methods is applicable to monitoring of AMPylation directly in living cells, due to a lack of cell permeability of ATP analogues.

Recently, our group developed a cell‐permeable pro‐N6pA probe15 containing a phosphoramidate moiety to improve cell permeability and to avoid the first intracellular phosphorylation step, which is considered to be critical (Scheme 1 B).16 Metabolic activation of this probe thus yielded a sufficient concentration of the active N6pATP necessary to compete with inherently present endogenous ATP. Furthermore, the propargyl group of pro‐N6pA enabled the enrichment of modified proteins through LC‐MS/MS. Nevertheless, pro‐N6pA is less suited for fluorescence labelling of AMPylated proteins in living cells because the CuI usually used for click chemistry is cytotoxic and the overall yield is rather low.17

One major unsolved challenge in protein AMPylation research is, therefore, to monitor the dynamics of this PTM directly in living cells, in particular during endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, activated UPR or neural development. The detection of differences in AMPylation levels and targets might help to elucidate the function of this PTM in these key cellular processes. To achieve these goals, there is a strong need to advance new adenosine analogues for imaging of AMPylated proteins in living cells.

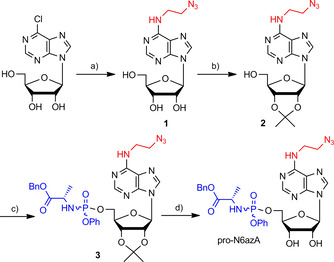

Herein, we introduce pro‐N6azA (Scheme 1 C), an N 6‐(2‐azidoethynyl)adenosine phosphoramidate, as a probe for AMPylation that allows the pronucleotide strategy16 to be combined with strain‐promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC)18 and Staudinger ligation19 with an affinity tag or fluorescence reporter in living cells. The synthesis of pro‐N6azA (Scheme 2 and Figure S1 in the Supporting Information) was carried out by use of a reported procedure for the preparation of N 6‐(2‐azidoethynyl)adenosine (1) starting with a nucleophilic aromatic substitution of 6‐chloropurine riboside with 2‐azidoethylamine. We have further developed the synthetic route to the corresponding pro‐N6azA phosphoramidate prodrug through the introduction of the acetonide protecting group onto the 2′‐ and 3′‐hydroxy groups to afford compound 2.20 Subsequent treatment of the accessible primary 5′‐hydroxy group with benzyl (chloro(phenoxy)phosphoryl)alaninate21, 22 in the presence of tBuMgCl yielded the 2′,3′‐dihydroxy‐protected N 6‐(2‐azidoethyl)adenosine phosphoramidate 3. Removal of the acetonide gave the desired pro‐N6azA probe.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of pro‐N6azA probe. a) 2‐Azidoethylamine, Et3N, EtOH, 60 °C, overnight, 90 %; b) Me2C(OMe)2, 10 % TsOH, acetone, RT, 2 h, 74 %; c) benzyl (chloro(phenoxy)phosphoryl)alaninate, tBuMgCl, THF, RT, overnight, 74 %; d) 90 % TFA, RT, 1 h, 89 %.

To test the utility of the probe for application in living cells, we measured its cytotoxicity by means of the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) proliferation assay. Only low cytotoxicity, with an IC50 of 239.2 μm, towards HeLa cells was observed (Figure S2). Next, we tested whether the pro‐N6azA probe would be accepted as a substrate by endogenous AMPylators in HeLa cells, through fluorescence labelling and in‐gel analysis. After treatment of HeLa cells with 100 μm of the pro‐N6azA probe for 16 h, the cells were lysed, and labelled proteins were tagged by SPAAC with DBCO‐PEG‐TAMRA and separated by SDS‐PAGE. Fluorescence scanning revealed numerous potential protein targets, whereas minimal unspecific coupling of the DBCO reagent was observed in the case of the DMSO control (Figure 1 A).

Figure 1.

Chemical proteomics approach. A) Fluorescence scan of PAGE‐separated proteins labelled with the pro‐N6azA probe in living cells and tagged with DBCO‐TAMRA. B) Schematic representation of chemical proteomic protocol. C) Volcano plot showing N6azA‐enriched proteins. Proteins previously identified with the pro‐N6pA probe are highlighted in green. Proteins additionally identified by the pro‐N6azA probe are highlighted in red.

To identify the protein targets of the pro‐N6azA probe we carried out a MS‐based chemical proteomics experiment (Figure 1 B).23, 24 Intact HeLa cells were treated with the pro‐N6azA probe at 100 μm final concentration.

Subsequently, modified proteins were linked to phosphine‐PEG‐biotin through Staudinger ligation under optimized conditions.25 Biotin‐labelled proteins were subsequently enriched on avidin‐coated agarose beads, digested and analyzed by LC‐MS/MS. Label‐free quantification (LFQ)26 of proteins enriched from pro‐N6azA‐treated samples, in comparison with DMSO‐treated controls, revealed several known AMPylated proteins, including PPME1, PFKP, SQSTM1, CTSB, CTSA and SCPEP1 as significant hits (Figure 1 C and Table S1). Moreover, a panel of previously unidentified targets, such as cysteine cathepsins CTSC and CTSZ, ABHD6, ACP2, PNPLA and TPP1, were identified solely with the new probe.

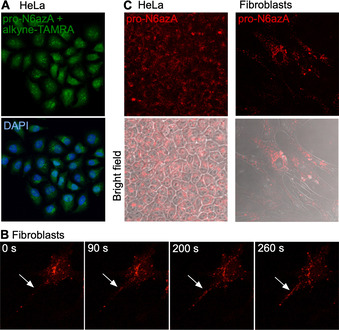

With the established chemical proteomic platform to hand, we next performed labelling of AMPylated proteins in living cells followed by fluorescence imaging. We started with control labelling in HeLa cells, which were treated with pro‐N6azA for 16 h, fixed and subsequently tagged with an alkyne‐TAMRA reagent by use of copper‐catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC; Figure 2 A). The distribution of the fluorescence signal revealed the majority of labelling occurring within the nucleus. There is also some degree of labelling in the cytoplasm, corroborating previous studies with the pro‐N6pA probe. Next, we performed pro‐N6azA labelling and fluorescence microscopy in living HeLa cells and fibroblasts. The probe was incubated with cells for 16 h, followed by staining with the DBCO‐TAMRA reagent. The cells were either directly imaged or incubated for an additional 24 h (Figure 2 B and C). Both sets of conditions resulted in intensive labelling for both cell lines. Indeed, comparison with HeLa cells not treated with the probe shows minimal background labelling with the DBCO‐TAMRA reagent (Figure S3). In particular, labelling in fibroblasts revealed a characteristic distribution of AMPylated proteins in the cytoplasm with a lack of fluorescence signal in the nucleus.15

Figure 2.

Fluorescence imaging. A) Imaging with pro‐N6azA and alkyne‐TAMRA in fixed HeLa cells. B) Directional transport of labelled proteins towards the processes of fibroblasts imaged in living fibroblast cells by using a time‐lapse camera. White arrows point to the process of the cell. C) Pro‐N6azA probe staining in living HeLa and fibroblast cells with DBCO‐TAMRA 1 d after SPAAC. Control containing HeLa cells not treated with the probe, but treated with DBCO‐TAMRA shows minimal background labelling (Figure S3).

To demonstrate the utility of the pro‐N6azA probe as a tool for visualization of protein AMPylation dynamics with accurate spatiotemporal resolution, we took advantage of the SPAAC labelling in living cells. Fibroblast cells were treated with the probe and imaged in a time‐lapse series under a confocal laser scanning microscope, snapshots being taken every 20 s for a period of 25 minutes. Transport of AMPylated proteins across processes expanding out from the ends of the cell bodies could be followed over time (Figure 2 B). This directional transport might support the polarization of the cell body. Interestingly, incubation of the cells for an additional 24 h after SPAAC revealed remaining bright labelling, thus showing that protein AMPylation is a stable protein PTM (Figure 2 C). This further supports the hypothesis that AMPylation is involved in the maintenance of fibroblast cell morphology (Movies S1–S3).

In summary, protein AMPylation represents a largely uncharacterized protein post‐translational modification. Building on previous chemical proteomic studies with N 6‐propargyl adenosine pronucleotide, we introduce here a cell‐permeable N 6‐(2‐azidoethyl)adenosine phosphoramidate probe for labelling of AMPylated proteins in living cells by SPAAC with the DBCO‐TAMRA reagent. The probe enables strong labelling in living cells and visualizes the dynamics of protein AMPylation for at least one day. Finally, time‐lapse imaging shows the transportation of labelled proteins along processes in fibroblast cells. The pro‐N6azA probe, therefore, is a powerful chemical biology tool for complex studies on protein AMPylation under various conditions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) through a consolidator grant (725085–CHEMMINE), SFB749 and by an Alexander von Humboldt fellowship to P.K.

P. Kielkowski, I. Y. Buchsbaum, T. Becker, K. Bach, S. Cappello, S. A. Sieber, ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1285.

References

- 1. Engel P., Goepfert A., Stanger F. V., Harms A., Schmidt A., Schirmer T., Dehio C., Nature 2012, 482, 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ham H., Woolery A. R., Tracy C., Stenesen D., Krämer H., Orth K., J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 36059–36069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sanyal A., Chen A. J., Nakayasu E. S., Lazar C. S., Zbornik E. A., Worby C. A., Koller A., Mattoo S., J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 8482–8499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Preissler S., Rato C., Chen R., Antrobus R., Ding S., Fearnley I. M., Ron D., eLife 2015, 4, e12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Casey A. K., Orth K., Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1199–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanyal A., Dutta S., Camara A., Chandran A., Koller A., Watson B. G., Sengupta R., Ysselstein D., Montenegro P., Cannon J. R., Rochet C., Mattoo S., J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 2266–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sreelatha A., Yee S. S., Lopez V. A., Park B. C., Kinch L. N., Pilch S., Servage K. A., Zhang J., Jiou J., Karasiewicz-Urbańska M., et al., Cell 2018, 175, 809–821.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Preissler S., Rato C., Perera L., Saudek V., Ron D., Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Casey A. K., Moehlman A. T., Zhang J., Servage K. A., Krämer H., Orth K., J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 21193–21204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Worby A. C., Mattoo S., Kruger R. P., Corbeil L. B., Koller A., Mendez J., Zekarias B., Lazar C., Dixon J., Mol. Cell 2009, 34, 93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pieles K., Glatter T., Harms A., Schmidt A., Dehio C., Proteomics 2014, 14, 1048–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Broncel M., Serwa R. A., Bunney T. D., Katan M., Tate E. W., Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2016, 15, 715–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hao Y.-H., Chuang T., Ball H. L., Luong P., Li Y., Flores-Saaib R. D., Orth K., J. Biotechnol. 2011, 151, 251–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Müller M. P., Albers M. F., Itzen A., Hedberg C., ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kielkowski P., Buchsbaum I. Y., Kirsch V. C., Bach N. C., Drukker M., Cappello S., Sieber S. A., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehellou Y., Balzarini J., McGuigan C., ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 1779–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li S., Wang L., Yu F., Zhu Z., Shobaki D., Chen H., Wang M., Wang J., Qin G., Erasquin U. J., et al., Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 2107–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agard N. J., Prescher J. A., Bertozzi C. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15046–15047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prescher J. A., Bertozzi C. R., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nainar S., Beasley S., Fazio M., Kubota M., Dai N., Corrêa I. R., Spitale R. C., ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 2149–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deduras M., Carta D., Brancale A., Vanpouille C., Lisco A., Margolis L., Balzarini J., McGuigan J. C., J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 5520–5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quintiliani M., Persoons L., Solaroli N., Karlsson A., Andrei G., Snoeck R., Balzarini J., McGuigan C., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 4338–4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wright M., Sieber S., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 681–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Storck E., Morales-Sanfrutos J., Serwa R. A., Panyain N., Lanyon-Hogg T., Tolmachova T., Ventimiglia L. N., Martin-Serrano J., Seabra M. C., Wojciak-Stothard B., et al., Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 552–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoegl A., Nodwell M. B., Kirsch V. C., Bach N. C., Pfanzelt M., Stahl M., Schneider S., Sieber S. A., Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 1234–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cox J., Hein M. Y., Luber C. A., Paron I., Nagaraj N., Mann M., Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 2513–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary

Supplementary