Abstract

We report a photoredox catalyzed α-amino C–H arylation reaction of highly substituted piperidine derivatives with electron deficient cyano(hetero)arenes. The scope and limitations of the reaction were explored, with piperidines bearing multiple substitution patterns providing the arylated products in good yields and with high diastereoselectivity. In order to probe the mechanism of the overall transformation, optical and fluorescent spectroscopic methods were used to investigate the reaction. By employing flash-quench transient absorption spectroscopy, we were able to observe electron transfer processes associated with radical formation beyond the initial excited state Ir(ppy)3 oxidation. Following the rapid and unselective C–H arylation reaction, a slower epimerization occurs to provide the high diastereomer ratio observed for a majority of the products. Several stereoisomerically pure products were re-subjected to the reaction conditions, each of which converged to the experimentally observed diastereomer ratios. The observed distribution of diastereomers corresponds to a thermodynamic ratio of isomers based upon their calculated relative energies using density functional theory (DFT).

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Piperidines are by far the most prevalent of all heterocycles found in drugs.1 For example, the piperidine substructure is present in the blockbuster antidepressant paroxetine, morphine along with its congeners, many of the anti-histamine class of drugs, and tofacitinib used in the treatment of arthritis and ulcerative colitis.1 Substitution about the piperidine scaffold is extremely common,1a and for this reason, efficient new methods for the diastereoselective elaboration of the piperidine framework have the potential to greatly facilitate the discovery of new pharmaceutical agents.

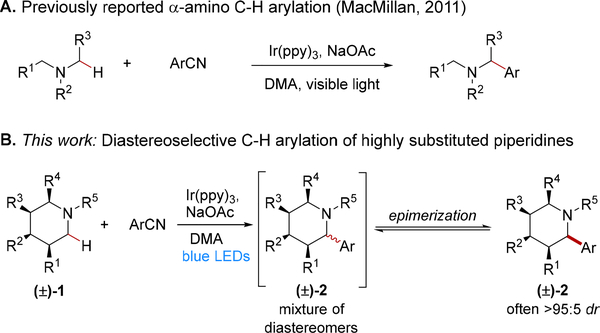

Photoredox catalysis utilizing transition metalpolypyridyl complexes has provided a powerful strategy to access novel reactivity manifolds.2 Although the utility of α-amino radicals has long been appreciated,3 the MacMillan group provided a seminal study using a transition metal photoredox catalyst for the synthesis of α-branched amines via α-amino radical coupling with electron deficient cyano(hetero)arene derivatives (Scheme 1A).4,5 Following this report, many groups have developed transformations using α-amino radicals as the reactive intermediate for additions to alkenes and other unsaturated π-bonds,6 cross-coupling with (hetero)arenes,7 and other coupling partners.8

Scheme 1.

Photoredox catalyzed α-amino C–H arylation

Achieving stereoselective transformations is one of the major challenges for photoredox catalysis because radicals serve as key reactive intermediates.9 In this regard, significant advances have been realized for the asymmetric synthesis of α-branched amines via α-amino radical intermediates using photoredox catalysts often in combination with other modes of catalysis.10 Approaches for the diastereoselective synthesis of α-branched amines to produce compounds that incorporate two or more stereogenic centers via α-amino radical intermediates have also been developed.10c,11 However, the elaboration of complex molecules incorporating stereogenic center(s) requires that diastereoselectivity be achieved relative to the pre-existing stereogenic center(s). This type of stereoselective transformation has rarely been explored for photoredox catalyzed α-amino radical reactions.11b,12,13

Although the reactivity of α-amino radicals can introduce challenges for achieving stereoselective transformations, the low inversion barrier for these radicals also provides new opportunities for stereoselective synthesis by epimerization. Pioneering studies by Bertrand and coworkers demonstrated that a thiyl radical could mediate the racemization of benzylic amines through reversible hydrogen abstraction.14 Very recently, Knowles and Miller have achieved an impressive photo-driven deracemization of cyclic ureas based on the use of excited-state redox events.10a Moreover, in a photoredox catalyzed reverse polarity Povarov annulation to give disubstituted tetrahydroquinolines, an increase in diastereoselectivity to 18:1 was observed when the initial 10:1 ratio of product diastereomers was re-submitted to the reaction conditions.11e,15,16

Herein, we report the development of a highly diastereoselective Ir(III) photoredox catalyzed reaction cascade that proceeds by α-amino C–H arylation of densely functionalized piperidines 1 followed by epimerization at the α-position to give the most stable stereoisomer 2 (Scheme 1B). Notably, differentially substituted piperidine derivatives with up to four stereogenic centers were effective substrates, providing the products with generally high diastereoselectivity relative to the pre-existing stereogenic centers. We propose mechanisms for both the C–H arylation reaction and epimerization steps based on an array of spectroscopic studies and time courses for product formation. Our results are consistent with an unselective photoredox C–H arylation followed by product epimerization leading to the observed diastereoselectivity. The diastereomers underwent oxidation with comparable rate constants, and therefore, product oxidation kinetics were not responsible for the epimerization diastereoselectivity. We subjected the separate diastereomers to the photoredox-catalyzed reaction conditions, and each yielded the experimentally observed distribution of diastereomers suggesting that the reaction is under thermodynamic control. The calculated relative energies of the diastereomers using density functional theory (DFT) correlate with the observed diastereomer ratios.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Efficient Preparation of Piperidine Starting Materials

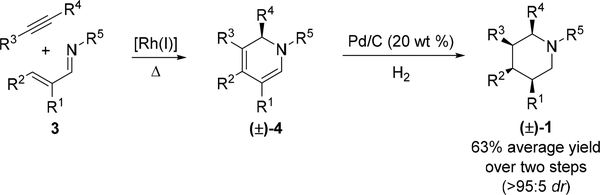

1. We first developed a facile two-step route to diastereomerically pure, densely substituted piperidines 1 from readily available precursors (Scheme 2). Previously, we reported a Rh(I)-catalyzed C–H activation/electrocyclization cascade to furnish highly substituted 1,2-dihydropyridines 4 from imines 3 and internal alkynes.17 Catalytic hydrogenation of dihydropyridines 4 with Pd/C then provides piperidines 1 (see Supporting Information for optimization Table S1 and experimental details).18 In all cases, only the all-cis stereoisomer was detected and was isolated in 63% average overall yield for the two step process.

Scheme 2.

Highly diastereoselective two-step synthesis of densely substituted piperidines

Optimization and Scope of C–H Arylation

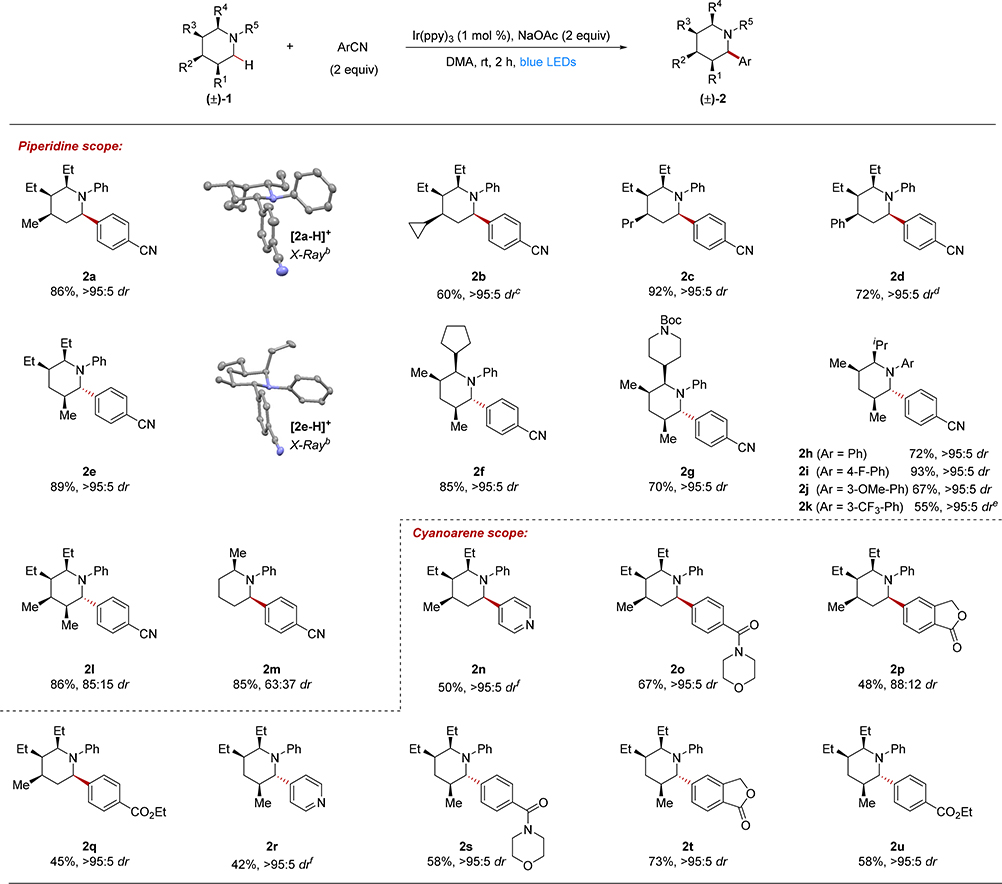

To optimize the yield and diastereoselectivity of the C–H arylation reaction, we explored a variety of conditions for arylating trisubstituted piperidine 1a (R1 = H, R2 = Me, R3 = R4 = Et) with 1,4-dicyanobenzene (DCB) to give 2a (Tables S2 and S3 in the Supporting Information). Ir(ppy)3 (ppy = 2-phenylpyridine) was determined to be the optimal photocatalyst for the α-arylation, in agreement with MacMillan’s earlier report.4,19 Of particular note, we were able to employ the piperidine as the limiting reagent to give 2a in high yield and with high diastereoselectivity (Table 1). For this transformation, arylation unambiguously provided the syn isomer as determined by X-ray crystallography.

Table 1.

Substrate scopea

|

Isolated yields on 0.2 mmol scale; dr was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the purified product and was within a single percentage point relative to the crude dr.

X-ray structure shown with anisotropic displacement ellipsoids at the 50% probability level. The picryl sulfonate counterion and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

87:13 dr prior to isolation determined by crude 1H NMR analysis.

16 h reaction time.

2 mol % Ir(ppy)3, 72 h reaction time.

[Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 instead of Ir(ppy)3.

The optimized conditions were next applied to a number of piperidine derivatives using DCB as the coupling partner (Table 1). Piperidines with the strained cyclopropyl ring (2b) and the linear propyl chain (2c) at R2 were effective substrates in the reaction. A phenyl substituent could also be incorporated at the R2 position to provide product 2d in good yield and with high diastereoselectivity, although a longer reaction time of 16 h was required.

Trisubstituted piperidines with a different substitution pattern also provided the arylated products in high yield and diastereoselectivity as exemplified for 2e-2k. However, for this substitution pattern, the anti-stereoisomer was obtained, as unambiguously determined by X-ray crystallography for 2e. Piperidines with cyclopentyl (2f), Boc protected piperidine (2g), and isopropyl (2h) at R4 were all effective substrates in the reaction. Notably, arylation of the N-Boc piperidine in 2g does not occur under our reaction conditions, due to the thermodynamically unfavorable oxidation of electron-deficient carbamates.20 Different N-aryl substituents were also evaluated, with products 2h-2k each obtained in good to high yields and with excellent diastereoselectivities. However, for alkyl, acyl and toluenesulfonyl substituents on the piperidine nitrogen, no coupling was observed (for a full list of unsuccessful reactants, see Table S4 in the Supporting Information).

Arylation of a tetrasubstituted piperidine gave the fully substituted piperidine product 2l in high yield and with 85:15 diastereoselectivity for the anti isomer.21 A monosubstituted piperidine also arylated in high yield to give product 2m with modest diastereoselectivity and with a preference for the syn isomer.21

Using piperidine 1a, we explored the scope with respect to the cyano(hetero)arene coupling partner (2n-2q). Heterocycles, such as for 4-cyanopyridine, provided product 2n in moderate yield and with high selectivity. The desired products were also obtained in moderate to good yields for other electron deficient cyanoarenes, including a para substituted morpholine amide (2o), phthalide (2p) and ethyl ester (2q). Arylation with the electron-rich 4-methoxybenzonitrile and the electron-neutral cyanobenzene were not successful, consistent with the redox potentials of these derivatives22 and with MacMillan’s initial report on tertiary aniline arylation.23,4 MacMillan has successfully coupled heteroaryl chlorides with unhindered tertiary anilines;24 however, with our more hindered, substituted piperidines less than 10% coupling occurred with 2-chlorobenzothiazole (for a full list of unsuccessful reactants, see Table S4 in the Supporting Information). All of the cyano(hetereo)arene coupling partners were additionally explored with a trisubstituted piperidine with a different substitution pattern and provided products 2r-2u in moderate to good yields and with excellent diastereoselectivities in all cases.

The large majority of piperidines that we investigated for arylation were efficiently prepared by face selective hydrogenation of DHPs 4 to give the all-syn substituted diastereomer 1 (see Scheme 2). To demonstrate the potential generality of the approach to other stereoisomers, we also evaluated the arylation of diastereomer 5 (eq 1), which displayed the 3-ethyl group anti to the two other alkyl substituents (for the synthesis of 5, see the Supporting Information). Under the standard reaction conditions, product 2v was obtained in good yield and with 84:16 diastereoselectivity.

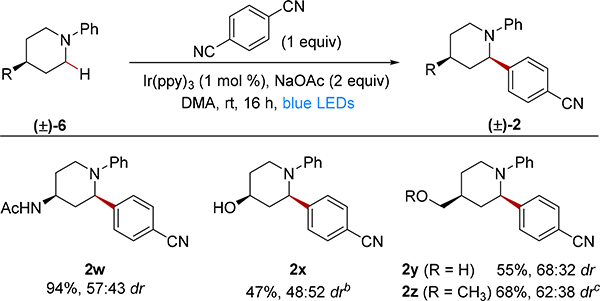

We further explored functional group compatibility of the reaction by evaluating readily accessible 4-substituted piperidines (Table 2). These unhindered piperidine substrates are capable of over-addition, which introduces an added challenge for obtaining high product yields. For photoredox mediated arylations of unhindered tertiary anilines, over-addition is typically minimized by using excess of the tertiary amine substrate.4 We instead chose to employ the DCB coupling partner in a 1:1 stoichiometry because the substituted piperidines are the more expensive of the two inputs. Even with this stoichiometry, the acetamide substituted piperidine provided the arylated product 2w in excellent yield though with modest diastereoselectivity. Products were also obtained in reasonable yields and modest diastereoselectivities for hydroxy (2x), hydroxymethyl (2y), and methoxymethyl (2z) substituents at the 4-position.

Table 2.

Examining scope with 4-substituted piperidinesa

|

Isolated yields on 0.2 mmol scale; dr was determined by 1H NMR analysis of the purified product and was within a single percentage point relative to the crude dr.

1:1 dr prior to isolation determined by crude 1H NMR analysis.

59:41 dr prior to isolation determined by crude 1H NMR analysis.

|

(1) |

Mechanistic Investigations

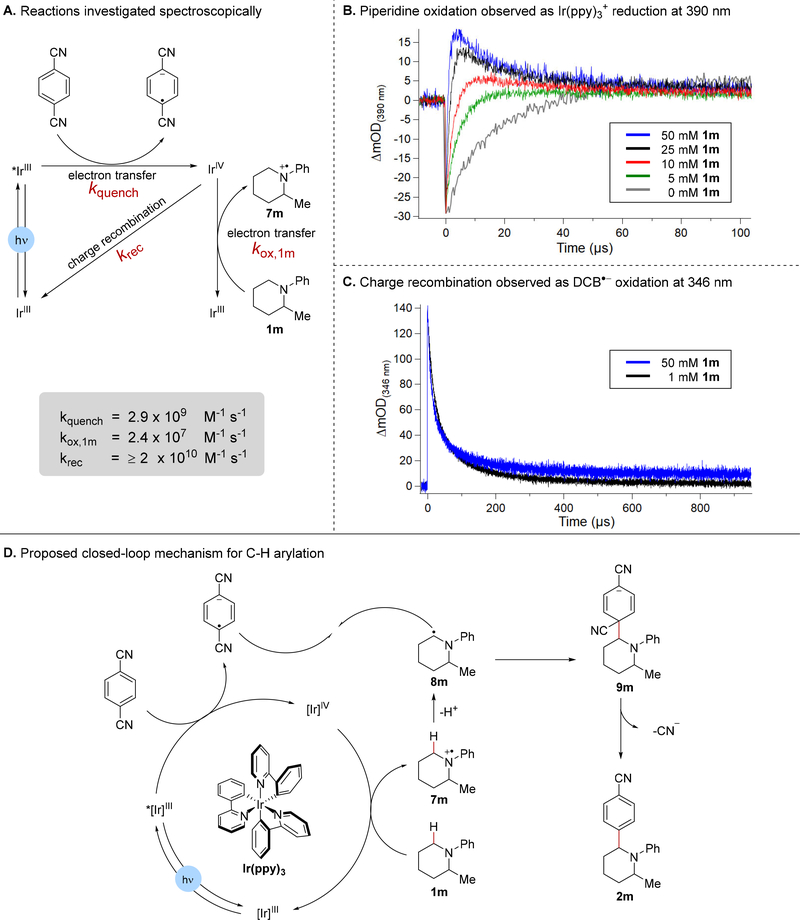

To better understand the mechanism of product formation, we investigated the reactivity of the Ir(ppy)3 photosensitizer and DCB intermediates using optical and fluorescent spectroscopies. Upon irradiation at 450 nm, the Ir complex undergoes a metal-to-ligand charge transfer followed by rapid intersystem crossing to give the long-lived triplet state that engages in single electron transfer.25 Based on the reduction potential of *Ir(ppy)3 (*E1/2(IrIV/*III) = −1.73 V vs. SCE in MeCN)26 and DCB (DCB/DCB·− Ep = −1.61 V vs. SCE in MeCN),27 we would expect an oxidative quenching mechanism to be operative, generating IrIV and the DCB·− in the first step as depicted in Figure 1A. Indeed, luminescence quenching studies revealed fast electron transfer (ET) between DCB and *Ir(ppy)3, occurring with a rate constant kquench = 2.9 × 109 M−1s−1 in N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA). In contrast, high concentrations of piperidine 1m caused minimal change in the *Ir(ppy)3 lifetime (see Figure S2 in the Supporting Information). These data, and the experimental excess of DCB, support an initial excited state ET producing Ir(ppy)3+ and DCB·− and are also in agreement with MacMillan’s previous observations.4

Figure 1.

Mechanistic studies (A) Reactions studied by TA and luminescence spectroscopies. (B) TA data collected at 390 nm with 10 mM DCB, 40 μM Ir(ppy)3, and increasing concentrations of 1m. The laser flash leads to rapid oxidation of the Ir(ppy)3+, yielding a large negative absorbance change because the Ir(ppy)3+ species has a smaller ε390 than Ir(ppy)3 (Figure S3). 1m oxidation by Ir(ppy)3+ is observed as a return in the absorbance at 390 nm as Ir(ppy)3+ is reduced to Ir(ppy)3. Residual DCB·− absorbance was observed at higher concentrations of 1m. (C) TA spectroscopy at 346 nm to monitor DCB·− reactivity. (D) Proposed photoredox cycle.

In order to examine the reactivity of these photoproducts, we pursued the visible absorption spectra for each. We obtained authentic absorption spectra for Ir(ppy)3+ from spectroelectrochemical oxidation of Ir(ppy)3 in DMA (see Figure S3 in the Supporting Information), and found authentic spectra for the DCB·− in the pulse radiolysis literature.28 We fortuitously observed an isosbestic point for the Ir(ppy)3 to Ir(ppy)3+ conversion at 346 nm, very close the λmax of the DCB·− species. This allowed us to observe absorption changes at 346 nm that correspond only to the evolution of DCB·−.

The reactivity of the Ir(ppy)3+ and DCB·− species is not visible in luminescence quenching studies, and so we turned to flash-quench transient absorption spectroscopy (TA) to observe the ground state reactivity of these photogenerated species. In the absence of piperidine substrate, Ir(ppy)3+ and DCB·− recombine at or near the diffusion limit (Figure 1C), which we can follow at 346 nm for the DCB·− decay and at 390 nm for the Ir(ppy)3+ decay (Figure 1B, S4 and S5 in the Supporting Information). This recombination follows an equal concentration bimolecular kinetic model (see Supporting Information). With added piperidine 1m, Ir(ppy)3+ is reduced back to Ir(ppy)3 more rapidly, consistent with piperidine oxidation by Ir(ppy)3+ to form the aminium radical cation 7m and Ir(ppy)3 (Figure 1A, S5 in the Supporting Information). In agreement with this observation, increasing concentration of piperidine 1m leads to larger residual absorbance for the DCB·− at 346 nm because the Ir(ppy)3+ that is consumed by piperidine oxidation is unable to recombine with DCB·− (Figure 1C, S5 in the Supporting Information). Piperidine oxidation by Ir(ppy)3+ is consistent with the reduction potentials of the two species, (E1/2(IrIV/III) = 0.77 V vs. SCE in MeCN) for the Ir(ppy)3 catalyst,26 versus the aminium cation (Ep = +0.71 V vs. SCE in MeCN for N,N-dimethylaniline).29 From the piperidine concentration dependent reformation of Ir(ppy)3 observed at 390 nm, we estimate a rate constant for piperidine oxidation kox,1m = 2.4 × 107 M−1s−1 in DMA (see Figure S6 in the Supporting Information).

Under the conditions of our luminescence quenching and TA measurements, the photoinduced formation of DCB·− and the piperidine radical cation seems plausible. We did not observe further radical coupling reactions involving the persistent DCB·− by TA or by transient absorption IR experiments, specifically searching for new CN containing photoproducts. We therefore turned to quantum yield measurements to determine the plausibility of a closed-loop photoredox mechanism under the C–H arylation conditions. We used Scaiano’s method30 to determine the quantum yield of the reaction between 1a and DCB. The quantum yield was calculated to be Φ = 0.5 at early conversions, indicating that the photoredox catalyzed cycle is reasonable, although radical chain pathways cannot be ruled out.31

Taken together, these findings support the proposed mechanism shown in Figure 1D, which is consistent with MacMillan’s original hypothesis.4 IrIII is excited by blue light to produce the excited state *IrIII, which transfers an electron to DCB to generate the IrIV species and the DCB radical anion. ET from the piperidine 1m to the IrIV regenerates IrIII. The formed amine radical cation 7m undergoes deprotonation at the α position by either NaOAc or the piperidine starting material or product, to deliver the α-amino radical 8m, which can undergo a radical-radical coupling with the persistent DCB radical anion.32 Following coupling to form 9m, extrusion of cyanide furnishes the arylated piperidine 2m and closes the catalytic cycle.

Epimerization studies

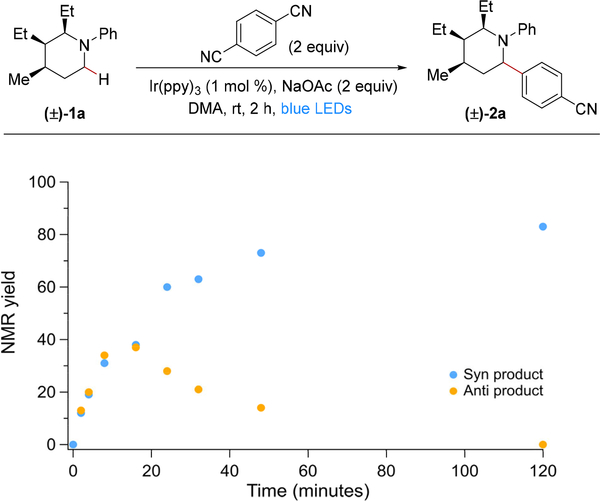

We sought to better understand the origins of the high diastereoselectivity observed under the reaction conditions, especially given that our postulated mechanism suggests that the C–C bond forming step is a radical-radical coupling.9b Surprisingly, when monitoring the progress of the reaction of piperidine 1a and DCB over time, we observed that the initial reaction is not stereoselective (Figure 2). In fact, at 16 min, the ratio of the syn to anti isomer is 50:50 with 75% of the product already formed. Over the course of the remaining 2 h, the anti product isomer 2a-anti epimerizes to the observed syn diastereomer 2a-syn, which is ultimately obtained in >95:5 dr.11e Additionally, if the reaction is irradiated for 16 min followed by stirring in the dark for the remaining 2 h, the dr is 56:36 slightly favoring 2a-anti, indicating that epimerization is a light driven process (see Table S5 in the Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Time course studies of the C–H arylation of 1a and follow-up epimerization of 2a.

In an effort to elucidate the mechanism of epimerization, we isolated the anti diastereomer 2a-anti (>95:5 dr) and subjected it to the reaction conditions (Table 3). Notably, we obtained only the syn diastereomer 2a-syn (>95:5 dr) in 85% yield after 2 h (Table 3, entry 1). Epimerization was next evaluated upon removing different reaction components. Complete epimerization to the syn diastereomer 2a-syn was still obtained when NaOAc was removed (Table 3, entry 2), indicating that NaOAc does not play a significant role in the epimerization mechanism. When DCB was removed, only 21% of the product epimerized, with the unreacted anti isomer 2a-anti recovered in 67% yield (Table 3, entry 3). Similar results were obtained when both DCB and NaOAc were removed (Table 3, entry 4). These observations suggest that significant epimerization only occurs under conditions that were shown to produce Ir(ppy)3+ upon irradiation.

Table 3.

Evaluating epimerization conditions

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entrya | conditions | % recovered 2a-anti | % yield 2a-syn |

| 1 | Standard conditions | <5 | 85 |

| 2 | No NaOAc | <5 | 74 |

| 3 | No DCB | 67 | 21 |

| 4 | No NaOAc, no DCB | 62 | 15 |

| 5b | No NaOAc, no DCB, [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 | <5 | 72 |

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy with 2,6-dimethoxytoluene as the external standard.

16 h reaction time.

To further explore this hypothesis, we postulated that a more oxidizing photocatalyst could directly form the piperidine radical cation by excited state electron transfer, without the need for initial quenching by DCB. To this end, we employed [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 (dtbbpy = 4,4’-di-tert-butyl-2,2’-bipyridine, *E1/2(IrIII/II) = 0.66 V vs. SCE in MeCN), whose excited state reduction potential is significantly more positive than that of Ir(ppy)3.25,33 Indeed, subjecting the anti diastereomer 2a-anti to [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6 under blue light, and in the absence of DCB, delivers the major diastereomer 2a-syn as the only detectable product in 72% yield (Table 3, Entry 5). These results are consistent with an epimerization mechanism that proceeds through initial product piperidine oxidation (Table 3).

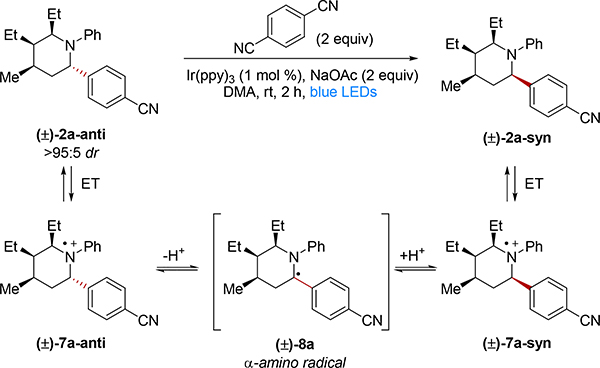

Based on these collective results, we propose the following mechanism for epimerization under the optimized reaction conditions with Ir(ppy)3 (see Table 3): Excited state quenching by DCB gives potent oxidant Ir(ppy)3+. ET from 2a-anti and perhaps also 2a-syn followed by deprotonation yields α-amino radical 8a. This intermediate then equilibrates to the 2a-syn isomer through subsequent reprotonation and ET.

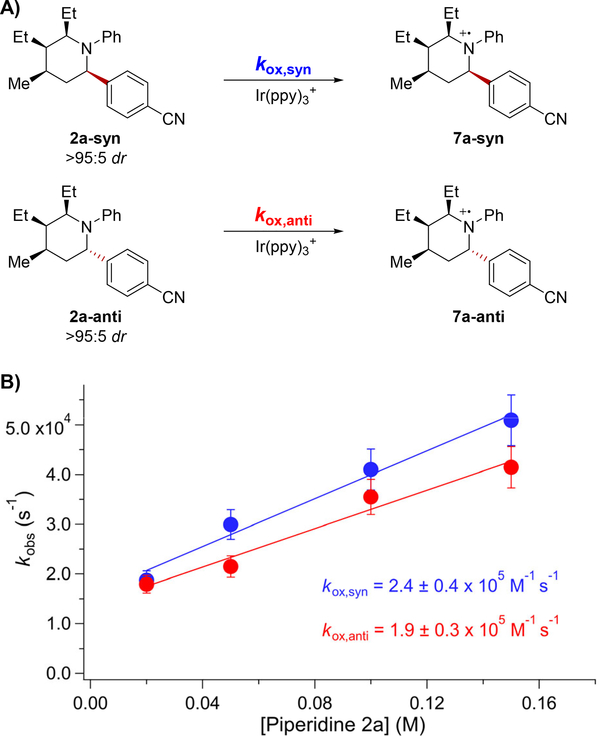

We next investigated whether or not the diastereoselectivity was a result of kinetic control as has been observed for other photoredox-catalyzed isomerization reactions.34,10a Specifically, one possibility for kinetic control would require that the piperidine diastereomers undergo initial ET oxidation at different rates leading to steady-state concentrations of the diastereomers (Figure 3). To evaluate this hypothesis, we measured the rate constants for oxidation of stereoisomerically pure 2a-syn and 2a-anti by Ir(ppy)3+ using TA spectroscopy. To account for the observed >19:1 2a-syn:2a-anti ratio, kinetically controlled selectivity would require that the rate constant for 2a-anti oxidation (kox,anti) is at least 19 times larger than the rate constant for 2a-syn (kox,syn), which would lead to depletion of 2a-anti and enrichment of 2a-syn under our reaction conditions. However, we determined that kox,anti and kox,syn were the same within error, indicating that the relative rate constants for piperidine oxidation were not responsible for the observed high selectivity. We can conclude that the epimerization is not kinetically controlled by initial oxidation to the aminium radical cations 7a.

Figure 3.

A) Oxidation reactions investigated for stereoisomerically pure 2a diastereomers. B) Plot of observed oxidation rate constant versus 2a concentration, where the slope is kox for the respective diastereomers. kox,anti and kox,syn are within error of each other.

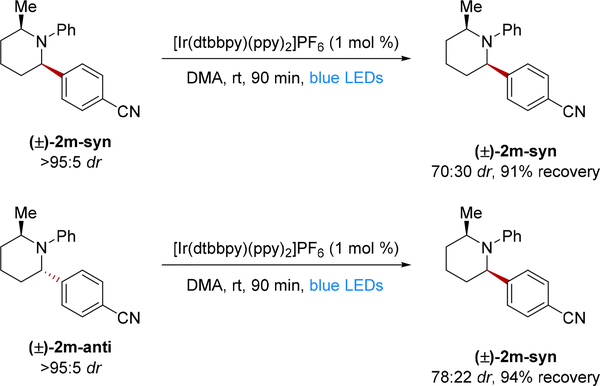

We therefore investigated whether or not the epimerization reaction could be under thermodynamic control. The proton transfer between 7a-syn and 7a-anti could generate an equilibrium mixture of diastereomers which controls the observed distribution of 2a diastereomers. Such an equilibrium should be achievable starting with either diastereomer. To probe this possibility, we examined piperidine 2m, which gave a quantifiable mixture of diastereomers under the reaction conditions (Scheme 3). We subjected both 2m-syn and 2m-anti separately to epimerization with the photocatalyst [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2]PF6. After 90 min of irradiation of the syn diastereomer 2m-syn, a 70:30 (syn:anti) mixture of stereoisomers was obtained in 91% yield. Furthermore, subjecting the anti diastereomer 2m-anti to the same conditions, gave a 78:22 (syn:anti) mixture of isomers and 94% recovery. Taken together, these results suggest that the observed diastereoselectivity can be approached from either diastereomer, which is consistent with a thermodynamically controlled process. However, this result does not rule out that the observed selectivity is due to a kinetically controlled steady state.10a

Scheme 3.

Equilibration of 2m-syn and 2m-anti diastereomersa

aYields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy with 2,6-dimethoxytoluene as the external standard.

Further evidence for a thermodynamically controlled epimerization was obtained using DFT calculations to determine the relative stability of various arylated piperidine diastereomers (Table 4). We reasoned that the relative stability of the 2-syn and 2-anti diastereomers and the 7-syn and 7-anti aminium radical cation diastereomers would be similarly affected by the piperidine substituents. The calculated relative free energies of 2-syn and 2-anti piperidine isomers correlate with the observed diastereomer ratios. For the less substituted piperidine 2m, the 2m-syn isomer was calculated to be 0.6 kcal/mol lower in energy than the 2m-anti isomer, consistent with the modest 63:37 syn:anti diastereoselectivity (Table 4, Entry 1). For piperidine 2a, the 2a-anti isomer is calculated to be 1.3 kcal/mol higher in energy than the experimentally obtained 2a-syn isomer (Table 4, Entry 2). This preference is likely due to the 2a-anti isomer having two axial alkyl substituents in the lowest-energy conformation (ethyl at R4 and methyl at R2), while the 2a-syn isomer only has one. For piperidine 2e, the difference in energy is more pronounced, with the 2e-syn isomer disfavored by 4.3 kcal/mol (Table 4, Entry 3). In this case, the aryl substituent and the ethyl group at R4 are calculated to be axial in the lowest energy conformation of 2e-syn. Typically, aryl substituents have much higher A values than secondary alkyl carbons,35 likely causing the 2e-anti isomer to be significantly more favored.

Table 4.

Calculated relative energies

| entrya | substrate | exptl. dr syn/anti | exptl. ΔGanti-ΔGsyn | calculated ΔGanti-ΔGsyn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2m | 63:37 | 0.3 – 0.7 | 0.6 |

| 2 | 2a | >95:<5 | >1.8 | 1.3 |

| 3 | 2e | <5:>95 | <−1.8 | −4.3 |

Level of theory: ωB97X-D/6-311++G(d,p), CPCM (DMA) // ωB97X-D/6-31G(d), CPCM (DMA).

Exptl. = experimental.

CONCLUSIONS

We have described the highly diastereoselective α-amino C–H arylation of densely substituted piperidine derivatives. This study represents a rare example of utilizing photoredox catalysis to promote diastereoselective transformations of complex molecules containing pre-existing stereogenic centers. Key to the generally high selectivity was an epimerization reaction that followed a rapid and non-selective C–H arylation. The observed selectivities for the overall transformation correlate to the calculated relative stabilities of the diastereomers. We anticipate that epimerization processes should be applicable to efficient, diastereoselective syntheses of many different classes of nitrogen heterocycles. Towards this end, efforts are underway in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NIH Grant R35GM122473 (to J. A. E.), NIH Grant R01GM050422 (to J. M. M.), and NSF Grant CHE-1764328 (to K. N. H.). B. K. thanks the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship for funding. We thank Dr. Brandon Q. Mercado (Yale) for solving the crystal structure of 2a, 2e, 5, 2v, and 2w and Dr. Fabian Menges (Yale) for assistance with mass spectrometry. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Eva Nichols (Yale) for assistance with spectroelectrochemistry and transient absorption IR, Dr. Maraia Ener-Goetz (Yale) for help with fluorescence quenching experiments and Amy Y. Chan (Yale) for the synthesis of starting materials. We also thank Dr. Kazimer Skubi (Yale) for helpful discussions and careful review of the manuscript. Calculations were performed on the Hoffman2 cluster at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant OCI-1053575).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Experimental procedures, characterization data, crystallographic data, optical and fluorescence quenching studies, and Cartesian coordinates of all computed structures.

REFERENCES

- 1. (a).Vitaku E; Smith DT; Njardarson JT Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Typing the name of these drug and drug candidates into PubChem (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) provides the compound structure, bioactivity, full list of published studies, and information regarding ongoing clinical trials, applications, and usage.

- 2. (a).Schultz DM; Yoon TP Solar Synthesis: Prospects in Visible Light Photocatalysis. Science 2014, 343, 1239176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Prier CK; Rankic DA; MacMillan DWC Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Narayanam JMR; Stephenson CRJ Visible light photoredox catalysis: applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. (a).Cho DW; Yoon UC; Mariano PS Studies Leading to the Development of a Single-Electron Transfer (SET) Photochemical Strategy for Syntheses of Macrocyclic Polyethers, Polythioethers, and Polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pandey G; Reddy GD; Kumaraswamy G Photoinduced Electron Transfer (PET) Promoted Cyclisations of 1-[N-alkyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)methyl] amines Tethered to Proximate Olefin: Mechanistic and Synthetic Perspectives. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 8185. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yoon UC; Mariano PS Mechanistic and Synthetic Aspects of Amine-Enone Single Electron Transfer Photochemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992, 25, 233. [Google Scholar]; (d) Pandey G; Kumaraswamy G; Bhalerao UT Photoinduced, S. E. T. Generation of α-amino radicals: A Practical Method for the Synthesis of Pyrrolidines and Piperidines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 6059. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNally A; Prier CK; MacMillan DWC Discovery of an α-Amino C–H Arylation Reaction Using the Strategy of Accelerated Serendipity. Science 2011, 334, 1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) For other methods of α-amino arylation, see: Jiang H-J; Zhong X-M; Yu J; Zhang Y; Zhang X; Wu Y-D; Gong L-Z Assembling a Hybrid Pd Catalyst from a Chiral Anionic CoIII Complex and Ligand for Asymmetric C(sp3)–H Functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Greβies S; Klauck FJR; Kim JH; Daniliuc CG; Glorius F Ligand-Enabled Enantioselective Csp3–H Activation of Tetrahydroquinolines and Saturated Aza-Heterocycles by Rh1. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 9950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jain P; Verma P; Xia G; Yu J-Q Enantioselective amine α-functionalization via palladium-catalysed C–H arylation of thioamides. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Spangler JE; Kobayashi Y; Verma P; Wang D-H; Yu J-Q α-Arylation of Saturated Azacycles and N-Methylamines via Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C(sp3)–H Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Peschiulli A; Smout V; Storr TE; Mitchell EA; Eliáš Z; Herrebout W; Berthelot D; Meerpoel L; Maes BUW Ruthenium-Catalyzed α-(Hetero)Arylation of Saturated Cyclic Amines: Reaction Scope and Mechanism. Chem. Eur. J. 2013,19, 10378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Campos KR; Klapars A; Waldman JH; Dormer PG; Chen C-Y Enantioselective, Palladium-Catalyzed α-Arylation of N-Boc-pyrrolidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Pastine SJ; Gribkov DV; Sames D sp3 C–H Bond Arylation Directed by Amidine Protecting Group: a-Arylation of Pyrrolidines and Piperidines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Li Z; Li C-J CuBr-Catalyzed Direct Indolation of Tetrahydroisoquinolines via Cross-Dehydrogenative Coupling between sp3 C–H and sp2 C–H Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. (a).Kohls P; Jadhav D; Pandey G; Reiser O Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis: Generation and Addition of N-Aryltetrahydroisoquinoline-Derived α-Amino Radicals to Michael Acceptors. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyake Y; Nakajima K; Nishibayashi Y Visible-Light-Mediated Utilization of α-Aminoalkyl Radicals: Addition to Electron-Deficient Alkenes Using Photoredox Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. (a).Gui Y-Y; Sun L; Lu Z-P; Yu D-G Photoredox sheds new light on nickel catalysis: from carbon–carbon to carbon–heteroatom bond formation. Org. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 522. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zuo Z; Ahneman DT; Chu L; Terrett JA; Doyle AG; MacMillan DWC Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: Coupling of α-carboxyl sp3-carbons with aryl halides. Science 2014, 345, 437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. (a).Nakajima K; Miyake Y; Nishibayashi Y Synthetic Utilization of α-Aminoalkyl Radicals and Related Species in Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mitchell EA; Peschiulli A; Lefevre N; Meerpoel L; Maes BUW Direct α-Functionalization of Saturated Cyclic Amines. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 10092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Campos KR Direct sp3 C–H bond activation adjacent to nitrogen in heterocycles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. (a).Meggers E Asymmetric catalysis activated by visible light. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Svoboda J; König B Templated Photochemistry: Toward Catalysts Enhancing the Efficiency and Selectivity of Photoreactions in Homogeneous Solutions. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 5413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) For the photoredox catalyzed enantioselective synthesis of α-branched amines via α-amino radicals, see: Shin NY; Ryss JM; Zhang X; Miller SJ; Knowles RR Light-Driven Deracemization Enabled by Excited-State Electron Transfer. Science 2019, 366, 364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Proctor RSJ; Davis HJ; Phipps RJ Catalytic enantioselective Minisci-type addition to heteroarenes. Science 2018, 360, 419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang C; Qin J; Shen X; Riedel R; Harms K; Meggers E Asymmetric Radical–Radical Cross-Coupling through Visible-Light-Activated Iridium Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zuo Z; Cong H; Li W; Choi J; Fu GC; MacMillan DWC Enantioselective Decarboxylative Arylation of α-Amino Acids via the Merger of Photoredox and Nickel Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Uraguchi D; Kinoshita N; Kizu T; Ooi T Synergistic Catalysis of Ionic Brønsted Acid and Photosensitizer for a Redox Neutral Asymmetric α-Coupling of N-Arylaminomethanes with Aldimines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Espelt LR; McPherson IS; Wiensch EM; Yoon TP Enantioselective Conjugate Additions of α-Amino Radicals via Cooperative Photoredox and Lewis Acid Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. (a).Leitch JA; Rogova T; Duarte F; Dixon DJ Dearomative Photocatalytic Construction of Bridged 1,3-Diazepanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McManus JB; Onuska NPR; Nicewicz DA Generation and Alkylation of α-Carbamyl Radicals via Organic Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rossolini T; Leitch JA; Grainger R; Dixon DJ Photocatalytic Three-Component Umpolung Synthesis of 1,3-Diamines. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Aycock RA; Pratt CJ; Jui NT Aminoalkyl Radicals as Powerful Intermediates for the Synthesis of Unnatural Amino Acids and Peptides. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9115. [Google Scholar]; (e) Leitch JA; Fuentes de Arriba AL; Tan J; Hoff O; Martínez CM; Dixon DJ Photocatalytic reverse polarity Povarov reaction. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Liu J; Xie J; Zhu C Photoredox organocatalytic α-amino C(sp3)–H functionalization for the synthesis of 5-membered heterocyclic γ-amino acid derivatives. Org. Chem. Front. 2017, 4, 2433. [Google Scholar]; (g) Xuan J; Cheng Y; An J; Lu L-Q; Zhang X-X; Xiao W-J Visible light-induced intramolecular cyclization reactions of diamines: a new strategy to construct tetrahydroimidazoles. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aminomethyl radical additions to the Karady–Beckwith chiral dehydroalanine gave 5-oxazolidinones with high diastereoselectivity; however, for aminoalkyl radical additions providing α-branched amines, little to no diastereoselectivity was observed at the branched site, see: Ref 11d.

- 13.For photoredox catalyzed generation of an iminium intermediate followed by diastereoselective cyclization to an imidazolidines, see Ref 11g.

- 14.Escoubet S; Gastaldi S; Vanthuyne N; Gil G; Siri D; Bertrand MP Thiyl Radical Mediated Racemization of Benzylic Amines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.See Scheme 3 in Ref 11e.

- 16.(a) For diastereoselective synthesis by reversible C–C bond formation by photoredox catalysis, see: Stache EE; Rovis T; Doyle AG Dual Nickel- and Photo redox-Catalyzed Enantioselective Desymmetrization of Cyclic meso-Anhydrides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keylor MH; Matsuura BS; Griesser M; Chauvin J-PR; Harding RA; Kirillova MS; Zhu X; Fischer OJ; Pratt DA; Stephenson CRJ Synthesis of resveratrol tetramers via a stereoconvergent radical equilibrium. Science 2016, 354, 1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. (a).Duttwyler S; Chen S; Takase MK; Wiberg KB; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Proton Donor Acidity Controls Selectivity in Nonaromatic Nitrogen Heterocycle Synthesis. Science 2013, 339, 678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Duttwyler S; Lu C; Rheingold AL; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Highly Diastereoselective Synthesis of Tetrahydropyridines by a C–H Activation–Cyclization–Reduction Cascade. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Colby DA; Bergman RG; Ellman JA Synthesis of Dihydropyridines and Pyridines from Imines and Alkynes via C-H Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiesenfeldt MP; Nairoukh Z; Dalton T; Glorius F Selective Arene Hydrogenation for Direct Access to Saturated Carbo- and Heterocycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.In the absence of catalyst, 10% product is observed (see Table S2). Under our standard reaction conditions, the large majority of visible photons are absorbed by Ir(ppy)3. However, in the absence of Ir(ppy)3, an EDA complex between the DCB and piperidine could result in the small amount of product formed. For a similar result, see: Miao M; Liao L-L; Cao G-M; Zhou W-J; Yu D-G Visible-light-mediated external-reductant-free reductive cross coupling of benzylammonium salts with (hetero)aryl nitriles. Sci. China Chem. 2019, 62, 1519. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shono T; Hamaguchi H; Matsumura Y Electroorganic chemistry. XX. Anodic oxidation of carbamates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 4264. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The relative stereochemistry for the major and minor diastereomers were determined by NOE correlations (see Supporting Information).

- 22.Sakamoto M; Cai X; Kim SS; Fujitsuka M; Majima T Intermolecular Electron Transfer from Excited Benzophenone Ketyl Radical. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ide T; Barham JP; Fujita M; Kawato Y; Egami H; Hamashima Y Regio- and chemoselective Csp3–H arylation of benzylamines by single electron transfer/hydrogen atom transfer synergistic catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 8453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prier CK; MacMillan DWC Amine α-heteroarylation via photoredox catalysis: a homolytic aromatic substitution pathway. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry MS; Goldsmith JI; Slinker JD; Rohl R; Pascal RA; Malliaras GG; Bernhard S Single-Layer Electroluminescent Devices and Photoinduced Hydrogen Production from an Ionic Iridium(III) Complex. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 5712. [Google Scholar]

- 26. (a).Flamigni L; Barbieri A; Sabatini C; Ventura B; Barigelletti F Photochemistry and Photophysics of Coordination Compounds: Iridium. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007, 281, 143. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dixon IM; Collin J-P; Sauvage J-P; Flamigni L; Encinas S; Barigelletti F A family of luminescent coordination compounds: Iridium(III) polyimine complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2000, 29, 385. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mori Y; Sakaguchi Y; Hayashi H Magnetic Field Effects on Chemical Reactions of Biradical Radical Ion Pairs in Homogeneous Fluid Solvents. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 4896. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson EA; Schulte-Frohlinde D Pulse Radiolysis of 1,4-Dicyanobenzene in Aqueous Solutions in the Presence and Absence of Thallium(1) Ions. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 1 1973, 69, 707. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo ET; Nelson RF; Fritsch JM; Marcoux LS; Leedy DW; Adams RN Anodic Oxidation Pathways of Aromatic Amines. Electrochemical and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 3498. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pitre SP; McTiernan CD; Vine W; DiPucchio R; Grenier M; Scaiano JC Visible-Light Actinometry and Intermittent Illumination as Convenient Tools to Study Ru(bpy)3Cl2 Mediated Photoredox Transformations. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cismesia MA; Yoon TP Characterizing chain processes in visible light photoredox catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leifert D; Studer A The Persistent Radical Effect in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slinker JD; Gorodetsky AA; Lowry MS; Wang J; Parker S; Rohl R; Bernhard S; Malliaras GG Efficient Yellow Electroluminescence from a Single Layer of a Cyclometalated Iridium Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh K; Staig SJ; Weaver JD Facile Synthesis of Z-Alkenes via Uphill Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anslyn EV; Dougherty DA Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, 2006; p 1104. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.