Abstract

The domestic silkworm Bombyx mori expresses two sucrose-hydrolyzing enzymes, BmSUH and BmSUC1, belonging to glycoside hydrolase family 13 subfamily 17 (GH13_17) and GH32, respectively. BmSUH has little activity on maltooligosaccharides, whereas other insect GH13_17 α-glucosidases are active on sucrose and maltooligosaccharides. Little is currently known about the structural mechanisms and substrate specificity of GH13_17 enzymes. In this study, we examined the crystal structures of BmSUH without ligands; in complexes with substrates, products, and inhibitors; and complexed with its covalent intermediate at 1.60–1.85 Å resolutions. These structures revealed that the conformations of amino acid residues around subsite −1 are notably different at each step of the hydrolytic reaction. Such changes have not been previously reported among GH13 enzymes, including exo- and endo-acting hydrolases, such as α-glucosidases and α-amylases. Amino acid residues at subsite +1 are not conserved in BmSUH and other GH13_17 α-glucosidases, but subsite −1 residues are absolutely conserved. Substitutions in three subsite +1 residues, Gln191, Tyr251, and Glu440, decreased sucrose hydrolysis and increased maltase activity of BmSUH, indicating that these residues are key for determining its substrate specificity. These results provide detailed insights into structure–function relationships in GH13 enzymes and into the molecular evolution of insect GH13_17 α-glucosidases.

Keywords: glycoside hydrolase, crystal structure, enzyme kinetics, sucrose, carbohydrate metabolism, phylogenetic, glycoside hydrolase family 13 subfamily 17 (GH13_17), BmSUH, BmSUC1, Bombyx mori, conformational change, enzyme mechanism, inhibitor, substrate specificity, phylogenetics

Sucrose, α-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-d-fructofuranoside, is ubiquitously distributed in plants and is utilized as a carbon source by many organisms. In general, sucrose is hydrolyzed by glycoside hydrolases (GHs) to produce glucose and fructose, which are primary substrates for glycolysis (1, 2). Sucrose-hydrolyzing enzymes are largely divided into two types. β-Fructofuranosidase (invertase) recognizes a β-fructofuranosyl residue and hydrolyzes substrates via a covalent fructosyl-enzyme intermediate (3). Sucrose α-glucosidase (sucrase) recognizes an α-glucopyranosyl residue and hydrolyzes the α-glucosidic linkages of sucrose and maltose (4). According to the CAZy database (RRID:SCR_012909) (5), β-fructofuranosidases belong to GH family 32 and GH68 that form the clan GH-J and share five-bladed β-propeller folded catalytic domains (3). Sucrose α-glucosidases that show relaxed substrate specificity (e.g. sucrase-isomaltase in mammals) are categorized in GH31 (4), and sucrose-specific α-glucosidases are identified as GH13 from Xanthomonas bacteria and lepidopterans (6–9) and as GH100 from bacteria and plants (10, 11). GH13 and GH31 enzymes employ a retaining mechanism (12, 13), whereas GH100 enzymes are proposed to hydrolyze sucrose by an inverting mechanism analogous to other inverting α-glucosidases (11, 14–17). Sucrose is also a substrate for GH13 amylosucrase (18, 19) and GH70 glucansucrase (20, 21) that produce α-glucose polymers and for GH13 sucrose phosphorylase, which catalyzes the phosphorolysis of sucrose instead of hydrolysis (22, 23).

GH13 is a large GH family, with more than 90,000 protein sequences in the CAZy database, and comprises various glycosidases and transglycosylases active on α-glucosidic bonds, such as α-amylase, pullulanase, α-glucosidase, and cyclodextrin glucanotransferase. More than 100 GH13 enzyme structures have been determined, and they share a domain architecture comprised of three domains: A, B, and C. Domain A is the catalytic domain that displays a (β/α)8-barrel fold (24). To date, this family is further divided into 42 subfamilies (GH13_1 to GH13_42) (25). GH13_17 is mainly composed of α-glucosidases active on maltooligosaccharides and their homologous proteins in insects only (26–30). Several hymenopteran and dipteran GH13_17 α-glucosidases have been cloned and enzymatically characterized, and some enzymes have activity for maltooligosaccharides and sucrose (31–35). Wang et al. (8) identified sucrose-specific hydrolases (SUHs) from lepidopterans Bombyx mori, Trilocha varians, and Samia cynthia ricini, which are homologous to GH13_17 α-glucosidases and hydrolyze sucrose but not other α-glucosides, such as maltose, isomaltose, and trehalose. SUHs are membrane-associated enzymes and are expressed in the midguts of these lepidopterans, where GH32 β-fructofuranosidase is also expressed, to digest sucrose (8, 36). There were very few studies on structure–function relationships of insect GH13 enzymes; the structures of GH13_15 α-amylase from yellow meal worm and most recently of the GH13_17 α-glucosidase (Cqm1) from a mosquito have been determined (37, 38). However, in the latter case, only an apo form of the enzyme is available; thus, the relationships between the structure and substrate specificity of GH13_17 enzymes are still unclear.

In this study, we examined the crystal structures of B. mori SUH (BmSUH) in an apo form and in complexes with ligands, including substrates and inhibitors. The structure of the covalent intermediate was also determined using a synthetic substrate, revealing conformational changes of the enzyme and the complete conformational itinerary of substrates during hydrolysis. Combined with mutational analysis, amino acid residues important for substrate specificity were identified. This study provides novel molecular insights into the catalytic mechanisms and substrate specificity of GH13 enzymes.

Results and discussion

Expression and characterization of recombinant BmSUH

The N-terminally His-tagged BmSUH without its transmembrane region (residues 1–29) was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3). Initially, the recombinant enzyme was induced in the host cultured in a Luria–Bertani (LB) medium without additive, and it showed low activity with a low yield (∼0.6 mg protein/liter). When host cells were cultured and induced in LB supplemented with 10 mm CaCl2, the final yield of recombinant BmSUH reached ∼3 mg from 1 liter of the culture, suggesting that BmSUH may require calcium ion for proper folding. The optimum pH and temperature of the purified enzyme were 8.0 and 30 °C, respectively, when using sucrose as a substrate (Fig. S1). The enzyme was stable (>80% residual activity) up to 30 °C after a 30-min incubation and in a pH range of 6.0–11. BmSUH had rather strict substrate specificity toward sucrose and was slightly active on isomaltulose, 1-kestose, nystose, and maltooligosaccharides (from maltose to maltohexaose). Among synthetic substrates, α-glucosyl fluoride (GlcF) was hydrolyzed by BmSUH, whereas p-nitrophenyl α-glucopyranoside was not (Table 1). Km, kcat, and kcat/Km values for sucrose were 0.92 mm, 41.2 s−1, and 44.7 s−1 mm−1, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Substrate specificity of recombinant BmSUH

| Substrate | Relative activitya |

|---|---|

| % | |

| Sucrose [Glc-α(1↔2)β-Fru] | 100 ± 2a |

| Turanose [Glc-α(1→3)-Fru] | NDb |

| Isomaltulose [Glc-α(1→6)-Fru] | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 1-Kestose [Glc-α(1↔2)β-Fru-(1←2)β-Fru] | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| Nystose [Glc-α(1↔2)β-Fru-(1←2)β-Fru-(1←2)β-Fru] | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Trehalose [Glc-α(1↔1)α-Glc] | ND |

| Kojibiose [Glc-α(1→2)-Glc] | ND |

| Nigerose [Glc-α(1→3)-Glc] | ND |

| Maltose [Glc-α(1→4)-Glc] | 0.05 ± 0.03 |

| Maltotriose | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Maltotetraose | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| Maltopentaose | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| Maltohexaose | 0.04 ± 0.03 |

| Isomaltose [Glc-α(1→6)-Glc] | ND |

| Raffinose [Gal-α(1→6)-Glc-α(1↔2)β-Fru] | ND |

| α-Glucosyl fluoride | 69 ± 4 |

| p-Nitrophenyl α-glucopyranoside | ND |

a Hydrolytic activity toward sucrose was taken to be 100% (24.1 ± 0.5 μmol min−1 mg−1).

b ND, not detected.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of recombinant BmSUH and its mutants for sucrose and maltotriose compared with GH13_17 α-glucosidases

| Enzyme | Sucrose |

Maltotriose |

Reference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat | Km | kcat/Km | Relative kcat/Kma | kcat | Km | kcat/Km | Relative kcat/Km | ||

| s−1 | mm | s−1 mm−1 | -fold | s−1 | mm | s−1 mm−1 | -fold | ||

| BmSUH | This study | ||||||||

| WT | 41.2 ± 0.6 | 0.92 ± 0.06 | 44.7 | 1 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 6.73 ± 0.66 | 0.043 | 1 | |

| Q191V | 26.0 ± 0.7 | 1.36 ± 0.14 | 19.1 | 0.43 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 3.09 ± 0.21 | 0.165 | 3.8 | |

| D247N (nucleophile) | NDb | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| Y251H | 40.4 ± 0.9 | 1.95 ± 0.17 | 20.7 | 0.46 | 2.09 ± 0.06 | 1.63 ± 0.39 | 1.28 | 30 | |

| E322Q (acid/base) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| E440A | 14.9 ± 0.5 | 0.89 ± 0.14 | 16.7 | 0.37 | 1.30 ± 0.02 | 1.56 ± 0.16 | 0.833 | 19 | |

| HBG-II | 87.6 | 30.6 | 2.91 | 87.2 | 3.82 | 22.8 | 33 | ||

| HBG-III | 222 | 42.3 | 5.27 | 133 | 8.56 | 15.6 | 33 | ||

| Cqm1 | 329 | 7.74 | 44.6 | 320 | 2.18 | 147 | 34 | ||

a Normalized to the kcat/Km value of WT BmSUH toward each substrate.

b ND, not detected.

Overall structure of BmSUH

The crystal structure of BmSUH was determined at a resolution of 1.85 Å using the molecular replacement method with Bacillus licheniformis GH13_29 trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase (32% sequence identity, PDB entry 5BRQ) (39) as a search model because no GH13_17 structure was initially available during this study.

In addition, we determined eight structures complexed with ligands at 1.60–1.90 Å resolution, including WT enzyme complexed with glucose (BmSUH-Glc) and three inhibitors (BmSUH-DNJ, -DAB, and -ACR); catalytically inactive mutants D247N and E322Q complexed with sucrose (D247N-Suc and E322Q-Suc); E322Q covalent intermediate generated using GlcF (E322Q-GlcF); and its complex form with fructose (E322Q-GlcF-Fru) (Table 3). The details of mutants and ligand complexes are described below. All crystals belong to the space group P212121 and contain two molecules in an asymmetric unit. The monomer of BmSUH contained four domains: a catalytic domain A (residues 30–146, 220–419, and 500–520); domain B (residues 147–219); domain B′ (residues 420–499); and domain C (residues 521–606) (Fig. 1A). The domains A, B, and C are generally conserved in GH13 enzymes: domain A adopts a (β/α)8-barrel fold; domain B is inserted into each catalytic domain A and consists of five β-strands and one α-helix; and domain C adopts a β-sandwich fold. A structural homology search using the Dali server (40) reveals high structural similarity to Culex quinquefasciatus GH13_17 maltase (Cqm1; PDB entry 6K5P) (38), GH13_31 sucrose isomerases (41–44), GH13_31 α-1,6-glucosidases (45–49), GH13_31 α-1,4-glucosidases (50, 51), GH13_23 α-glucosidases (52), GH13_16 trehalose synthases (53–56), GH13_29 trehalose 6-phosphate hydrolase (39), and GH13_40 oligo-α-1,6-glucosidase (57) (Table S1). All of these enzymes are exo-glycosidases active on α-glucosides and have domain B′, which is inserted in each catalytic domain A (Fig. S2).

Table 3.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| BmSUH Apo | BmSUH-Glc | BmSUH-DNJ | BmSUH-DAB | BmSUH-ACR | D247N-Suc | E322Q-Suc | E322Q-GlcF | E322Q-GlcF-Fru | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||||||

| Beamline | PF BL5A | PF BL5A | PF AR-NW12A | PF BL5A | PF AR-NW12A | PF BL5A | PF BL5A | PF AR-NW12A | PF AR-NW12A |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 65.9, 145.7, 153.8 | 64.7, 128.5, 154.0 | 65.6, 146.8, 154.0 | 65.1, 146.4, 153.3 | 65.3, 145.8, 152.9 | 64.9, 128.3, 154.8 | 64.7, 127.9, 154.3 | 64.4, 128.3, 154.4 | 65.4, 147.1, 153.5 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–1.85 (1.92–1.85) | 50–1.70 (1.73–1.70) | 50–1.90 (2.00–1.90) | 50–1.75 (1.84–1.75) | 50–1.75 (1.84–1.75) | 50–1.85 (1.95–1.85) | 50–1.84 (1.94–1.84) | 50–1.70 (1.79–1.70) | 50–1.60 (1.69–1.60) |

| Measured reflections | 751,624 | 855,106 | 1,546,590 | 973,471 | 1,815,578 | 479,722 | 727,454 | 662,288 | 1,241,043 |

| Unique reflections | 127,062 | 141,639 | 117,900 | 148,023 | 147,455 | 105,020 | 111,648 | 140,237 | 194,405 |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100)a | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 100 (100) | 95.1 (92.9) | 99.9 (100) | 99.5 (99.1) | 99.7 (100) |

| Redundancy | 5.9 (5.4) | 6.0 (6.0) | 13.1 (12.8) | 6.6 (6.7) | 12.3 (11.9) | 4.6 (3.9) | 6.5 (6.7) | 4.7 (4.3) | 6.4 (6.6) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 19.5 (2.5) | 13.5 (2.1) | 18.4 (3.0) | 15.4 (2.2) | 18.7 (2.8) | 6.5 (2.2) | 12.4 (2.4) | 7.9 (2.0) | 16.9 (2.6) |

| Rmerge | 0.083 (0.620) | 0.094 (0.769) | 0.099 (0.933) | 0.074 (0.889) | 0.080 (0.805) | 0.120 (0.491) | 0.097 (0.775) | 0.127 (0.683) | 0.061 (0.650) |

| CC1/2 | 0.992 (0.786) | 0.998 (0.674) | 0.999 (0.850) | 0.999 (0.755) | 0.999 (0.846) | 0.985 (0.778) | 0.998 (0.769) | 0.989 (0.672) | 0.999 (0.833) |

| Refinement statistics | |||||||||

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.157/0.186 | 0.155/0.182 | 0.173/0.197 | 0.162/0.184 | 0.199/0.228 | 0.192/0.216 | 0.180/0.211 | 0.183/0.211 | 0.178/0.207 |

| RMSDb | |||||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (degrees) | 1.392 | 1.458 | 1.516 | 1.301 | 1.695 | 1.600 | 1.600 | 1.345 | 1.780 |

| No. of atoms | |||||||||

| Protein | 9,327 | 9,297 | 9,308 | 9,312 | 9,304 | 9,258 | 9,277 | 9,266 | 9,406 |

| Ligand/Ion | 45 | 43 | 51 | 64 | 94 | 52 | 52 | 26 | 85 |

| Water | 1,223 | 1,066 | 872 | 1,021 | 610 | 566 | 740 | 822 | 983 |

| Average B (Å2) | |||||||||

| Protein | 23.6 | 17.7 | 31.6 | 30.4 | 32.1 | 24.7 | 27.9 | 26.6 | 31.2 |

| Ligands | 40.5 | 20.3 | 38.9 | 40.1 | 30.9 | 21.2 | 23.5 | 24.4 | 31.1 |

| Water | 31.6 | 27.2 | 35.7 | 37.2 | 33.6 | 25.1 | 31.1 | 31.5 | 38.0 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||||||||

| Favored (%) | 98.2 | 97.8 | 97.6 | 97.1 | 97.2 | 97.9 | 97.5 | 98.1 | 97.6 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| PDB codes | 6LGA | 6LGB | 6LGC | 6LGD | 6LGE | 6LGF | 6LGG | 6LGH | 6LGI |

a The values for the highest resolution shells are given in parentheses.

b Root mean square deviation.

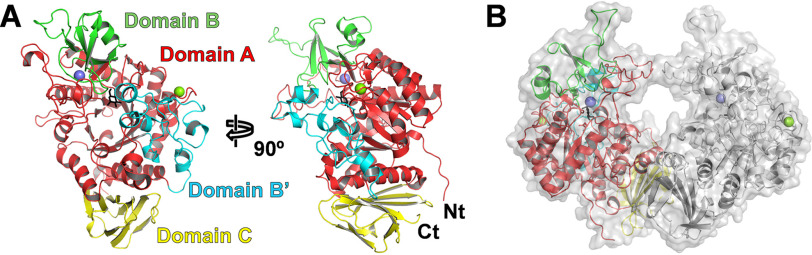

Figure 1.

Overall structure of BmSUH. A, ribbon model of the BmSUH monomer. The catalytic (β/α)8 barrel A-domain is shown in red, domain B is green, domain B′ is cyan, and domain C is yellow. Calcium and magnesium ions are indicated as slate blue and light green spheres, respectively, and glucose at subsite −1 is shown as a black stick model. The N and C termini are indicated as Nt and Ct, respectively. B, molecular surface and ribbon models of BmSUH dimer. One protomer is shown in the same colors in A, and the other is shown in gray.

Electron density maps for two metal ions were found in domain A. One (site I) is in a solvent-accessible loop of domain A and is hexacoordinated with Asp63, Asp65, Asp67, Asp71, Leu69, and one water molecule (Fig. S3). The other site (site II) is located at the interface between domain A and domain B and is heptacoordinated with Asn144, Asp217, Tyr251, Leu252, Glu254, and two water molecules. Considering the experimental conditions and the electron density maps after refinement, the former metal was assigned as magnesium and the latter as calcium. Among the subfamilies structurally homologous to GH13_17, site I is conserved in subfamilies GH13_16, 23, 29, 31, and 40, whereas site II is conserved only in GH13_16 (Fig. S2).

The molecular masses of BmSUH calculated by its amino acid sequence and calibrated by gel filtration chromatography were 68.7 and 151.3 kDa, respectively (data not shown), suggesting that the enzyme forms a dimer in the solution. The analysis using the Protein Interfaces, Surfaces, and Assemblies (PISA) server (58) revealed that BmSUH is dimeric via 16 hydrogen bonds and six salt bridges (Fig. 1B and Fig. S4). The buried interface area is 1,131 Å2 (5.0% of the monomer surface). Seventeen residues per monomer are involved in these interactions, with 11 residues located in domain A and the rest in domain C. The dimeric state is similar to that of Cqm1 (38), but BmSUH has another interaction interface between each loop (Glu254–Tyr287) inserted in the domain A (β/α)8-barrel (Fig. S4).

Complex structures with substrates and products

To identify residues involved in substrate recognition and the hydrolytic mechanism of BmSUH, the crystal structure of the enzyme complexed with Glc (BmSUH-Glc) was determined. An electron density map for an α-glucose molecule was found at subsite −1. Glucose interacted with Asp102, His145, Glu322, His388, Asp389, and Arg455 residues via hydrogen bonds and with Tyr105 by hydrophobic stacking (Fig. 2A). These residues are completely conserved in GH13_17 and related subfamilies GH13_16, 23, 29, 31, and 40 (Figs. S5 and S6). GH13 enzymes hydrolyze α-glucosidic linkages using a retaining mechanism. Similar to other similar enzymes, Asp247 and Glu322 were identified as nucleophilic and acid/base catalytic residues, respectively. In support, mutants D247N and E322Q lost hydrolytic activity toward sucrose (Table 2).

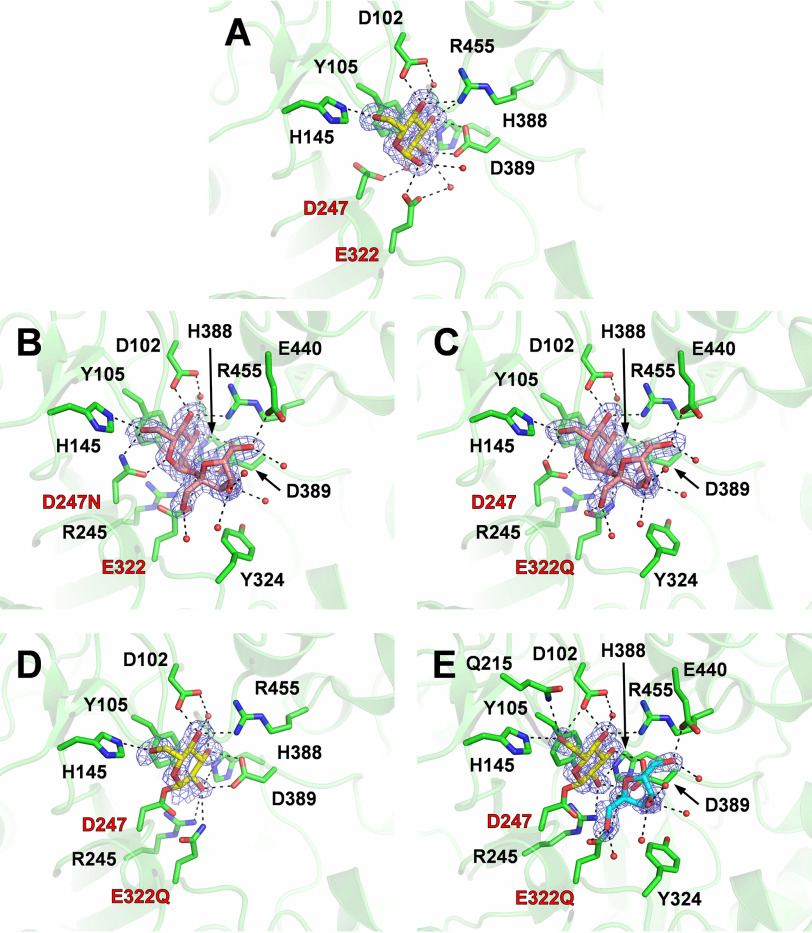

Figure 2.

Active sites of BmSUH complexes with substrates, intermediates, and products. Active-site structures of BmSUH-Glc (A), D247N-Suc (B), E322Q-Suc (C), E322Q-GlcF (D), and E322Q-GlcF-Fru (E). The side chains of the amino acid residues and ligands are indicated as stick models, and water molecules interacting with ligands are shown as red spheres. |Fo| − |Fc| omit maps (contoured at 2 σ) for ligands and hydrogen bonds are shown as blue mesh and a dashed line, respectively. Labels of catalytic residues are highlighted in red. Colors used are as follows: amino acid residues (green), glucose and its covalent intermediate (yellow), sucrose (pink), and fructose (cyan).

Subsequently, the structures of D247N complexed with sucrose (D247N-Suc) and E322Q complexed with sucrose (E322Q-Suc) were determined. Clear electron density maps for sucrose were found at subsite −1 to +1 in both structures, and conformations of sucrose and interacting residues are almost identical (Fig. 2, B and C). Thus, the results using E322Q-Suc are used in the following discussions.

The orientation and 4C1 conformation of the sugar ring of the glucose residue in E322Q-Suc are identical to those of the α-glucose in BmSUH-Glc. The fructose residue of sucrose forms hydrogen bonds with Gln322 (acid/base), Asp389, and Glu440 (i.e. fewer bonds than the glucose residue). Tyr324 is located between the O1 atom of the fructose residue and the entrance of the active site, suggesting that longer substrates with a β-2,1-fructoside linkage (e.g. 1-kestose and nystose) have difficulty binding to the active site. This possibility is consistent with enzyme assays that show less activity toward such oligosaccharides (Table 1).

Trapping the covalent intermediate and conformational changes in the catalytic cycle

To completely understand the structural mechanism of BmSUH hydrolysis, the crystal structures of covalently bound intermediates, where glucose residue binds the nucleophilic catalytic residue of the enzyme, were determined by X-ray crystallography. Crystallizing E322Q in the presence of the synthetic substrate GlcF succeeded in trapping a covalent intermediate (E322Q-GlcF) at the active site (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the E322Q crystal prepared in the presence of GlcF and fructose provided the structure of a covalent intermediate with fructose at subsite +1 (E322Q-GlcF-Fru) with the same orientation as the fructose residue in E322Q-Suc (Fig. 2E). In both structures, covalently bound glucose forms a 4C1 conformation and interacts with the same residues as glucose molecules in BmSUH-Glc and E322Q-Suc, except that Gln215 forms an additional hydrogen bond with the O6 atom of covalently bound glucose. Gln215 is highly conserved among GH13_17 and other GH13 enzymes (Figs. S5 and S6), suggesting that it may have an important role in stabilizing the covalent intermediate.

Compared with ligand complex structures, the conformations of amino acid residues around subsite −1, including the catalytic residues, were remarkably different (Fig. 3A). The conformations of residues in the Michaelis complex (E322Q-Suc, E·S) are almost identical to the conformation of the ligand-free structure. By contrast, the conformation of Phe141, Val142, and Leu246 changes in the E322Q-GlcF-Fru complex (covalent intermediate, E-I·P1 in Fig. 3A). In particular, the main chains of Phe141 and Val142 get closer to subsite −1—their Cα atoms move by 1.8 and 1.1 Å, respectively—and the orientation of the side chains changes accordingly. No remarkable difference was observed between covalent intermediates with (E-I·P1) and without fructose (E322Q-GlcF, E-I). In BmSUH-Glc (E·P2), the orientation of the catalytic acid/base Glu322 changes, and the catalytic nucleophile Asp247 points away from the C1 atom of glucose. Accordingly, the side chains of Asp140 and Arg245 move to avoid steric hindrance with Asp247. Thus, conformations in the catalytic cycle of BmSUH can be divided into three states: open, semi-closed, and fully closed (Fig. 3A). No such conformational changes in the catalytic site appear to have been reported for other GH13 enzymes, including exo- and endo-acting forms. The function of these conformational changes is not clear, but they may contribute to the stabilization of the covalent intermediate during hydrolysis.

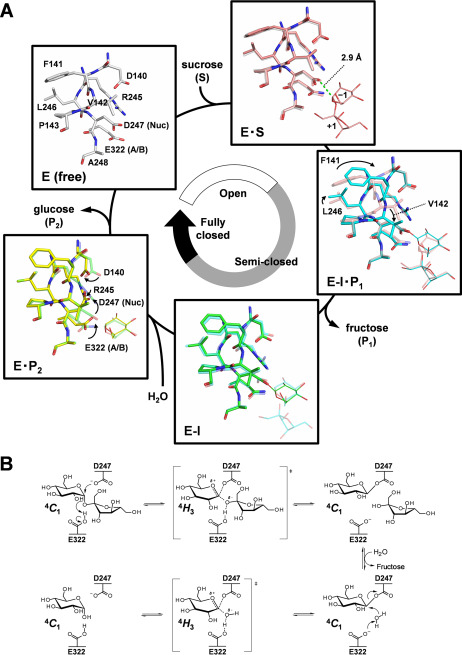

Figure 3.

Complete structural mechanism of sucrose hydrolysis by BmSUH. A, conformational changes in the active site during sucrose hydrolysis. E, enzyme; S, substrate; I, covalent intermediate; P1, product fructose; P2, product glucose; A/B, acid/base catalyst; Nuc, nucleophilic catalyst. The amino acid residues of E (white), E·S (pink), E-I·P1 (cyan), E-I (green), and E·P2 (yellow) states are indicated as sticks and their ligands as thin sticks. The distance between an oxygen atom of Asp247 nucleophilic catalyst and C1 atom of the glucose residue of substrate in the Michaelis (E·S) complex is shown as a green dashed line. The stick models of amino acid residues in a preceding state are superposed for transparency, and arrows indicate conformational changes of the residues. B, conformational itinerary of glucose during BmSUH hydrolytic reaction.

Through all steps in the BmSUH hydrolysis, including the covalent intermediate, the pyranose ring of glucose adopts a 4C1 conformation. The oxocarbenium ion in transition states before and after the covalent intermediate state may adopt a 4H3 half-chair, supported by the QM/MM analysis of GH13 amylosucrase that hydrolyzes sucrose (59). The conformational itinerary of BmSUH hydrolysis is suggested to be as follows: 4C1 → [4H3] → 4C1 → [4H3] → 4C1 (Fig. 3B). To date, the covalent intermediates of 10 GH13 enzymes have been identified using their substrates, covalent inhibitors (2-deoxy-2-fluoro-α-glycosyl fluorides and 5-fluoro-α-glycosyl fluorides), and a combination of α-glycosyl fluoride and catalytic acid/base mutagenesis (12, 23, 52, 60–66). Their sugar ring conformations take a 4C1 conformation, except for the covalent intermediates of Bifidobacterium adolescentis GH13_18 sucrose phosphorylase and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii GH13_11 isoamylase 1, where the sugar ring was distorted toward 1S3 skew-boat and half-chair conformations, respectively (23, 65). These differences are perplexing, but the QM/MM analysis using GH13_4 amylosucrase that showed 4C1 and E3 conformations can be seen in the covalent intermediate (59). GH31 α-glucosidases are also retaining enzymes, and the sugar ring is distorted into a 1S3 skew-boat conformation in their glycosyl–enzyme intermediates (67, 68). Consequently, the difference in the conformational itinerary among GH13 subfamilies may depend on their active-site architectures and substrate structures.

Complexes with inhibitors

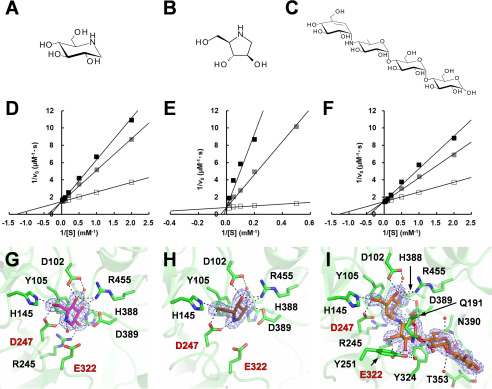

BmSUH and its lepidopteran orthologs are reportedly inhibited by 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) and 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-arabinitol (DAB) (Fig. 4, A and B), which are observed in the latex of mulberry (8, 69). BmSUH was reported to be less sensitive to these compounds than the other lepidopteran SUHs (8). However, inhibitory mechanisms had not been investigated. BmSUH activity was competitively inhibited by DNJ and DAB (Fig. 4, D and E), with a Ki value for DAB of 4.2 µm, considerably lower than the Ki for DNJ (290 µm). Interestingly, BmSUH was also competitively inhibited by acarbose (ACR) (Fig. 4, C and F), which is a maltotetraose mimic inhibitor, even though maltooligosaccharides were poor substrates for BmSUH (Table 1). ACR is a typical inhibitor toward α-amylases and α-glucosidases (34, 70–72) but not GH13_31 sucrose isomerase (41). The Ki of acarbose for BmSUH hydrolysis was 424 µm, which is higher than the Ki of GH13 α-amylases and α-glucosidases. These enzymes show a wide range of Ki values from nanomolar to micromolar levels (71, 73, 74).

Figure 4.

Inhibitors for sucrose hydrolysis by BmSUH. A–C, chemical structures of DNJ (A), DAB (B), and ACR (C). D–F, Lineweaver–Burk plots of BmSUH activity toward sucrose in the presence of DNJ (D), DAB (E), or ACR (F). Concentrations of inhibitors were as follows: 0 (open square), 0.5 (gray square), and 1.0 mm (black square) for DNJ and ACR; 0 (open square), 0.1 (gray square), and 0.5 mm (black square) for DAB. G–I, structures of the active sites in BmSUH-DNJ (G), BmSUH-DAB (H), and BmSUH-ACR (I) complexes. Colors are used in the same manner as in Fig. 2, and DNJ, DAB, and ACR are shown in magenta, brown, and orange, respectively.

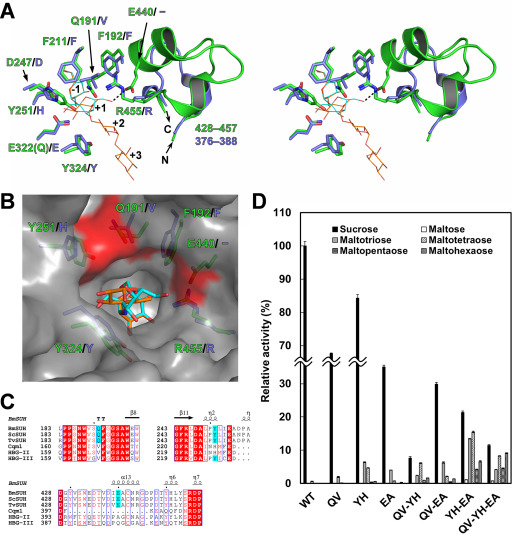

To obtain structural insights into the inhibitory mechanism, the crystal structures of BmSUH complexed with three inhibitors at 1.75–1.90 Å resolutions (Table 3) were examined. Clear electron density maps for DNJ and DAB were observed at subsite −1, and ACR occupied subsites −1 to +3 (Fig. 4, G–I). Compared with the acarviosine moiety of ACR that is recognized by several amino acids via hydrogen bonds, the reducing-end maltose residue forms fewer hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen of Thr353 and the side chain of Asn390 and is exposed to the solvent outside the active site (Fig. 4I). Although Cqm1 structure in the complex with substrates has not been determined, the superimposition of BmSUH-ACR and E322Q-Suc reveals that the orientation of sugar rings at subsite −1 is identical, and an imino linkage of ACR (corresponding to an α-1,4-glycosidic linkage of maltooligosaccharide) is located at the proper position to interact with catalytic residues (Fig. 5, A and B). However, the second sugar residue of ACR is in 6-deoxy form, and not enough space is available for an additional 6-hydroxy group of maltooligosaccharides. Thus, subsite +1 architecture may not be suitable for maltooligosaccharide substrate, because of the steric interference, resulting in a low hydrolytic activity (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Amino acid residues important for substrate specificity. A, structural comparison of the active sites of BmSUH (green) and Cqm1 (slate blue) in stereo. The side chains of the amino acid residues around subsite +1 are indicated as sticks, and residues 428–457 of BmSUH and the corresponding region (residues 376–388) of Cqm1 are displayed as ribbon models. Sucrose (cyan) and ACR (orange) derived from E322Q-Suc and BmSUH-ACR are superimposed and indicated as thin stick models. B, molecular surface of the catalytic site of BmSUH. The side chains of the subsite +1 residues (green for BmSUH and slate blue for Cqm1), sucrose (cyan), and an acarviosine moiety of ACR (orange) are indicated. Solvent-accessible areas of Gln191, Tyr251, and Glu440 are highlighted in red. C, sequence alignments of regions around Gln191, Tyr251, and Glu440 and their corresponding regions of GH13_17 sucrose hydrolases and maltases. The conserved residues are highlighted in red; Gln191, Tyr251, and Glu440 of BmSUH and conserved residues of the other GH13_17 enzymes are in cyan. D, hydrolytic activity of BmSUH and its mutants toward sucrose and maltooligosaccharides (from maltose to maltohexaose). Bar charts and error bars, means and S.D., respectively, from triplicate experiments. QV, Q191V; YH, Y251H; EA, E440A; QV-YH, Q191V/Y251H; QV-EA, Q191V/E440A; YH-EA, Y251H/E440A; QV-YH-EA, Q191V/Y251H/E440A.

Active-site residues important for substrate specificity

To identify the structural determinants for substrate specificity, site-directed mutations were generated in the catalytic site of BmSUH. The sequence alignment of GH13_17 sucrose hydrolases and maltases demonstrated that amino acid residues around subsite +1 are not completely conserved (Fig. 5, B and C). In dipteran and hymenopteran α-glucosidases, the corresponding residues of Gln191 and Tyr251 of BmSUH are valine and histidine, respectively, except for Tyr227 of honeybee α-glucosidase III (HBG-III). Glu440 of BmSUH is completely conserved among lepidopteran SUHs but not in honeybee α-glucosidase II (HBG-II) and HBG-III. Furthermore, the region of residues 430–446 that includes Glu440 of BmSUH is lacking in Cqm1 (Fig. 5C). Q191V, Y251H, and E440A mutations were constructed, and their activities toward sucrose and maltotriose were analyzed. All mutations caused a decrease in sucrose hydrolysis activity and enhanced maltotriose-hydrolyzing activity (Table 2). The kcat values of Q191V and E440A toward sucrose decreased, whereas the kcat for Y251H was comparable with WT (Table 2). The Km value of E440A for sucrose was similar to WT, but the other mutations showed higher Km values, indicating that Glu440 and Tyr251 influence a catalytic turnover and affinity for sucrose, respectively, and that Gln191 is important for both. These mutations raised kcat and reduced Km for maltotriose. Y251H showed the highest catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km), 30-fold greater than WT. Ngiwsara et al. (33) reported that a corresponding mutation (Tyr227 → His) in HBG-III also resulted in a decrease of sucrose hydrolysis and in an increase maltooligosaccharide hydrolysis, indicating that Tyr251 is the most important residue for specificity toward sucrose.

Furthermore, double and triple mutations (combination of Q191V, Y251H, and E440A) were assessed for the activity toward sucrose, several maltooligosaccharides from maltose to maltohexaose. Double and triple mutants showed lower activity toward sucrose than the single mutants and higher activity toward maltooligosaccharides (Fig. 5D). Y251H/E440A mutant had 21- and 290-fold higher activity toward maltotriose and maltotetraose than WT, respectively. Interestingly, the triple mutant Q191V/Y251H/E440A had the highest activity toward longer substrates, namely, maltopentaose and maltohexaose, although the underlying reason is unclear. Unfortunately, no crystal structure of GH13_17 maltase complexed with substrates is available, but subsite +1 of BmSUH, which is composed of Gln191, Tyr251, and Glu440 residues (Q/V/E motif), may be narrower than that for GH13_17 maltases (Fig. 5B) and suitable for the fructose residue of sucrose.

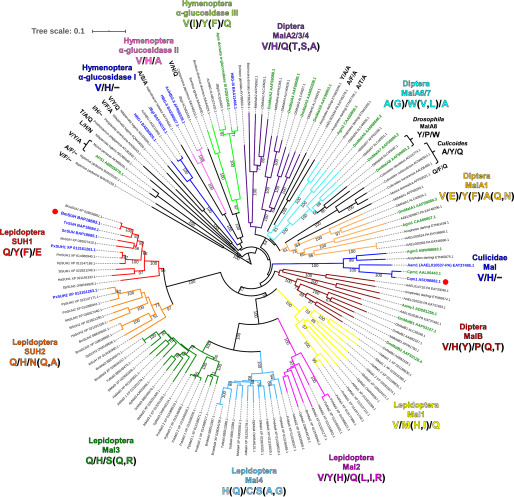

Distribution of sucrose hydrolases within GH13_17

The genomic analyses reveal that many insects, including lepidopteran species, possess several copies of GH13_17 (75). A phylogenetic analysis was completed using 142 sequences of GH13_17 proteins listed in the CAZy database or that were found in a PSI-BLAST search using BmSUH as a query sequence. The phylogenetic tree reveals that GH13_17 can be further divided into several clades (Fig. 6). The sucrose-specific motif (Q/Y/E) is highly conserved among the closest orthologs belonging to the same clades (Lepidoptera SUH1) as BmSUH, except for Danaus plexippus SUH1, where Tyr is substituted to Phe. Recent bioinformatics studies showed that some butterflies possess another paralog termed SUH2, and Dai et al. (9) reported that Papilio xuthus SUH2 has lower activity toward sucrose than P. xuthus SUH1. In the Lepidoptera SUH2 clade, the corresponding motif to the Q/Y/F of SUH1 is Q/H/N (Q, A), suggesting that enzymes belonging to SUH2 are not sucrose-specific and may have different substrate specificity. No protein that has the Q/Y/F motif was found in other clades that include dipteran and hymenopteran proteins. Moreover, lepidopterans have paralogs (Mal1, Mal2, Mal3, and Mal4) that have a different subsite +1 motif compared with SUH1 and SUH2. Taken altogether, lepidopterans may have evolved a unique digestion system for sugars, especially sucrose.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of GH13_17 proteins and amino acid residues related to substrate specificity. The 142 amino acid sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE program, and the phylogenetic tree constructed by the neighbor-joining method was visualized using the iTOL v5 server. Proteins used were enzymes listed in the CAZy database and their homologs (>40% identity) found using the PSI-BLAST search with BmSUH as a template. Bootstrap values based on 1,000 replicates are shown. Origins, abbreviations, and GenBankTM ID are labeled and summarized in Table S3. GH13_17 proteins are divided into several clades with different colors based on amino acid residues corresponding to subsite +1 (Gln191, Tyr251, and Glu440) in BmSUH. Proteins shown in green and blue are genetically identified and enzymatically characterized, respectively. BmSUH and Cqm1 are marked with red circles.

Conclusions

In this study, the crystal structure of GH13_17 sucrose hydrolase, BmSUH, is reported as the first such structure of an insect sucrose hydrolase. BmSUH adopts a domain architecture (domains A, B, B′, and C), such as enzymes belonging to GH13 exo-α-glucosidase subfamilies. BmSUH hydrolyzes sucrose with conformational changes in the active site never reported previously for GH13 enzymes. Subsite +1 residues Q/Y/E determine the strict specificity toward sucrose, and this motif is not found in insects other than lepidopterans. Further investigation, such as the enzymatic characterization, structural analysis, and physiological analysis of B. mori GH13_17 paralogs and other insect orthologs, will enable a complete understanding of carbohydrate digestion and the molecular evolution of related enzymes.

Experimental procedures

Materials and strains

Trehalose was obtained from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Nigerose, maltose, 1-kestose, nystose, and raffinose were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Co. (Osaka, Japan). Maltotriose, maltotetraose, maltopentaose, and maltohexaose were obtained from Hayashibara Co. (Okayama, Japan). Kojibiose, ACR, DNJ, and DAB were purchased from Carbosynth (Compton, Berkshire, UK). Turanose, isomaltulose, and isomaltose were from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co. (Tokyo, Japan). p-Nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside was obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). α-d-Glucopyranosyl fluoride was prepared by deacetylation of its tetraacetate derivative (Merck). All other chemicals were reagent grade and obtained from standard commercial sources. E. coli strains DH5α and BL21 (DE3) were used for DNA manipulation and protein expression, respectively.

Cloning, expression, purification, and mutagenesis

First-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription with total RNA from fifth-instar larvae (Ehime Sanshu, Ehime, Japan) as described previously (76). A transmembrane region of BmSUH (GenBankTM BAP18683.1) was predicted by the TMHMM server (RRID:SCR_014935). A DNA fragment coding BmSUH without the transmembrane region (Met1–Leu29) was amplified by PCR using cDNA as a template, KOD-Plus-Neo DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), and primers BmSUH_F and BmSUH_R (Table S2). The resultant DNA was digested with NdeI and XhoI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and ligated into a pET-28a vector (Merck), followed by DNA sequencing. The recombinant protein had an N-terminal His tag and a thrombin cleavage site (MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSHM-) prior to Ser30. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by inverse PCR with the desired primers (Table S2) using the recombinant BmSUH expression plasmid as a template.

E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring the desired plasmids was grown at 37 °C in 1 liter of LB medium containing 10 mm CaCl2 and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. When the culture reached an optical density of 0.6–0.8 measured at 600 nm, it was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at a final concentration of 0.1 mm and further incubated overnight at 20 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 30 ml of 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 20 mm imidazole and 300 mm NaCl before disruption by sonication. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min to remove insoluble debris. The supernatant was applied to a nickel (Ni2+) nitrilotriacetic acid–agarose (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) column equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed with buffer, and recombinant proteins were eluted with 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 250 mm imidazole and 300 mm NaCl. Enzymes were dialyzed against 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and applied to a Mono Q 5/50 GL column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a linear gradient of 300–600 mm NaCl. Fractions containing active enzymes were concentrated using an Amicon Ultra 30,000 molecular weight cut off (Merck) and further purified by gel filtration chromatography with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) and 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 300 mm NaCl. The latter two purification steps were performed using an ÄKTAexplorer system (GE Healthcare). Protein purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm based on theoretical molar absorption coefficients (127,660 m−1 cm−1) calculated using the ExPASy ProtParam server (RRID:SCR_018087).

Enzymatic assays

The hydrolytic activity toward sucrose and other oligosaccharides was measured in 50-µl reaction mixtures containing 2.0 µg/ml of purified enzyme, 10 mm substrate, and 50 mm HEPES–NaOH buffer (pH 8.0) at 30 °C. After incubation for 15 min, reactions were quenched by boiling for 3 min, and the amount of glucose liberated was measured using the glucose oxidase–peroxidase method with a Glucose C-II Test Kit (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan).

The effect of pH was measured at 30 °C using a 50 mm Britton–Robinson buffer (sodium borate–phosphate–citrate, pH 3.0–8.0) and 10 mm sucrose as the substrate. The effect of temperature was assayed at 25–60 °C using 100 mm HEPES–NaOH buffer (pH 8.0). To test the pH stability, enzymes (1 mg/ml) were incubated at 4 °C for 24 h in 20 mm Britton–Robinson buffer (pH 3.0–8.0). To test thermal stability, enzymes (1 mg/ml) were incubated at 20–65 °C in 20 mm HEPES–NaOH buffer (pH 8.0) for 30 min The remaining activity toward sucrose was examined under standard conditions described above.

Kinetic studies

The initial velocities of hydrolytic reactions for sucrose and maltotriose were determined using the 50 mm HEPES–NaOH buffer (pH 8.0) and at least five concentrations of substrate (0.5–40 mm). Enzyme concentrations were 2.0 µg/ml for sucrose and 20 µg/ml for maltotriose. All kinetic assays were performed at 30 °C. Kinetic parameters were calculated by the nonlinear regression analysis using KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA). For the inhibition kinetic assay for inhibitors, the same reaction mixtures supplemented with at least four concentrations of each inhibitor were used. Inhibition constants were calculated according to a competitive inhibition model.

Crystallization, data collection, structure determination, and refinement

Before the crystallization, purified proteins were concentrated to 7–10 mg/ml using Amicon Ultra 30K ultrafiltration devices (Millipore). Proteins were crystallized at 20 °C using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method, in which 1.0 µl of protein solution in 10 mm HEPES–NaOH buffer (pH 7.0) was mixed with an equal volume of a crystallization reservoir solution. Initial crystallization screening was performed using Crystal Screen, Crystal Screen 2, and PEG/Ion Screen kits (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA). Well-diffracted BmSUH crystals were obtained with a crystallization solution containing 12–18% (v/v) PEG 3,350 (Hampton Research) and 200 mm magnesium acetate. The crystals of WT or mutant enzymes in complex with ligands were obtained by co-crystallization under the same condition in the presence of 10 mm sucrose, α-glucopyranosyl fluoride, fructose or DAB, or 2 mm DNJ or ACR. All crystals were cryoprotected with the reservoir solution supplemented with glycerol at a final concentration of 22% (v/v) and then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Diffraction data were collected at PF BL5A and PF AR NW12A beamlines (Photon Factory, Tsukuba, Japan). All data were processed and scaled using either HKL2000 (77), Mosflm (78), or XDS (79). Initial structure solutions were obtained using the automated molecular replacement program MrBUMP (80). The best solution was obtained when B. licheniformis GH13_29 trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase (PDB entry 5BRQ) was used as a search model. Structures complexed with ligands were solved with the molecular replacement method using MOLREP (81), with the unliganded structure as a search model. Refinement was performed using REFMAC5 (82), and manual adjustment and rebuilding of the model were performed using Coot (83). Solvent molecules were introduced using ARP/wARP (84). Structure validation was performed using MolProbity (85). The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 3. Protein assembly was evaluated by the PISA server (RRID:SCR_015749) (58). Structural figures were prepared using PyMOL (Schrödinger LLC, New York). Coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank under the accession codes listed in Table 3.

Molecular weight determination

The molecular weights of recombinant BmSUH were determined by gel filtration chromatography in the condition as described above. Calibration was performed using Gel Filtration Calibration Kit HMW (GE Healthcare) containing blue dextran 2,000 (2,000 kDa), thyroglobulin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa), and ovalbumin (44 kDa).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetics

Protein sequences were obtained using the CAZy database and PSI-BLAST search with BmSUH as a template. The primary sequence alignment was performed using the MUSCLE program (86). Alignment figures were generated by ESPript 3.0 (87). The phylogenetic analysis of GH13_17 proteins was performed with the neighbor-joining method (88) using multiple alignments prepared as above. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the iTOL v5 server (RRID:SCR_018174) (89).

Data availability

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank under accession codes 6LGA, 6LGB, 6LGC, 6LGD, 6LGE, 6LGF, 6LGG, 6LGH, and 6LGI. All other data are contained within the article.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Shinya Fushinobu for providing the Cremer–Pople parameter calculator. We also thank the staff of the Photon Factory for the X-ray data collection. This research was approved by the Photon Factory Program Advisory Committee (proposals 2017G051 and 2019G097).

This article contains supporting information.

Author contributions—T. M. and E. Y. P. conceptualization; T. M. data curation; T. M. formal analysis; T. M. supervision; T. M. funding acquisition; T. M. and E. Y. P. validation; T. M. investigation; T. M. methodology; T. M. writing-original draft; T. M. project administration; T. M. and E. Y. P. writing-review and editing; E. Y. P. resources.

Funding and additional information—This work was supported in part by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant 19K15748 (to T. M.).

Conflict of interest—The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- GH

- glycoside hydrolase

- ACR

- acarbose

- BmSUH

- B. mori sucrose hydrolase

- CAZy

- carbohydrate-active enzyme

- Cqm1

- C. quinquefasciatus maltase 1

- DAB

- 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-arabinitol

- DNJ

- 1-deoxynojirimycin

- GlcF

- α-glucopyranosyl fluoride

- HBG

- honeybee α-glucosidase

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- QM/MM

- quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics

- LB

- Luria–Bertani.

References

- 1. Ruan Y. L. (2014) Sucrose metabolism: gateway to diverse carbon use and sugar signaling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 33–67 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reid S. J., and Abratt V. R. (2005) Sucrose utilisation in bacteria: genetic organisation and regulation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67, 312–321 10.1007/s00253-004-1885-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lammens W., Le Roy K., Schroeven L., Van Laere A., Rabijns A., and Van den Ende W. (2009) Structural insights into glycoside hydrolase family 32 and 68 enzymes: functional implications. J. Exp. Bot. 60, 727–740 10.1093/jxb/ern333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sim L., Willemsma C., Mohan S., Naim H. Y., Pinto B. M., and Rose D. R. (2010) Structural basis for substrate selectivity in human maltase-glucoamylase and sucrase-isomaltase N-terminal domains. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17763–17770 10.1074/jbc.M109.078980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., and Henrissat B. (2014) The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 10.1093/nar/gkt1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim H. S., Park H. J., Heu S., and Jung J. (2004) Molecular and functional characterization of a unique sucrose hydrolase from Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines. J. Bacteriol. 186, 411–418 10.1128/JB.186.2.411-418.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Champion E., Remaud-Simeon M., Skov L. K., Kastrup J. S., Gajhede M., and Mirza O. (2009) The apo structure of sucrose hydrolase from Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris shows an open active-site groove. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1309–1314 10.1107/S0907444909040311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang H., Kiuchi T., Katsuma S., and Shimada T. (2015) A novel sucrose hydrolase from the bombycoid silkworms Bombyx mori, Trilocha varians, and Samia cynthia ricini with a substrate specificity for sucrose. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 61, 46–52 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dai X., Li R., Li X., Liang Y., Gao Y., Xu Y., Shi L., Zhou Y., and Wang H. (2019) Gene duplication and subsequent functional diversification of sucrose hydrolase in Papilio xuthus. Insect Mol. Biol. 28, 862–872 10.1111/imb.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ji X., Van den Ende W., Van Laere A., Cheng S., and Bennett J. (2005) Structure, evolution, and expression of the two invertase gene families of rice. J. Mol. Evol. 60, 615–634 10.1007/s00239-004-0242-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xie J., Cai K., Hu H. X., Jiang Y. L., Yang F., Hu P. F., Cao D. D., Li W. F., Chen Y., and Zhou C. Z. (2016) Structural analysis of the catalytic mechanism and substrate specificity of Anabaena alkaline invertase InvA reveals a novel glucosidase. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 25667–25677 10.1074/jbc.M116.759290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uitdehaag J. C., Mosi R., Kalk K. H., van der Veen B. A., Dijkhuizen L., Withers S. G., and Dijkstra B. W. (1999) X-ray structures along the reaction pathway of cyclodextrin glycosyltransferase elucidate catalysis in the α-amylase family. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 432–436 10.1038/8235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lovering A. L., Lee S. S., Kim Y. W., Withers S. G., and Strynadka N. C. (2005) Mechanistic and structural analysis of a family 31 α-glycosidase and its glycosyl-enzyme intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2105–2115 10.1074/jbc.M410468200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sierks M. R., Ford C., Reilly P. J., and Svensson B. (1990) Catalytic mechanism of fungal glucoamylase as defined by mutagenesis of Asp176, Glu179 and Glu180 in the enzyme from Aspergillus awamori. Protein Eng. 3, 193–198 10.1093/protein/3.3.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gibson R. P., Gloster T. M., Roberts S., Warren R. A. J., Storch de Gracia I., García A., Chiara J. L., and Davies G. J. (2007) Molecular basis for trehalase inhibition revealed by the structure of trehalase in complex with potent inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 46, 4115–4119 10.1002/anie.200604825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palcic M. M., Scaman C. H., Otter A., Szpacenko A., Romaniouk A., Li Y. X., and Vijay I. K. (1999) Processing α-glucosidase I is an inverting glycosidase. Glycoconj. J. 16, 351–355 10.1023/A:1007096011392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miyazaki T., Nishikawa A., and Tonozuka T. (2016) Crystal structure of the enzyme-product complex reveals sugar ring distortion during catalysis by family 63 inverting α-glycosidase. J. Struct. Biol. 196, 479–486 10.1016/j.jsb.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skov L. K., Mirza O., Henriksen A., De Montalk G. P., Remaud-Simeon M., Sarçabal P., Willemot R. M., Monsan P., and Gajhede M. (2001) Amylosucrase, a glucan-synthesizing enzyme from the α-amylase family. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25273–25278 10.1074/jbc.M010998200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guérin F., Barbe S., Pizzut-Serin S., Potocki-Véronèse G., Guieysse D., Guillet V., Monsan P., Mourey L., Remaud-Siméon M., André I., and Tranier S. (2012) Structural investigation of the thermostability and product specificity of amylosucrase from the bacterium Deinococcus geothermalis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 6642–6654 10.1074/jbc.M111.322917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vujicic-Zagar A., Pijning T., Kralj S., López C. A., Eeuwema W., Dijkhuizen L., and Dijkstra B. W. (2010) Crystal structure of a 117 kDa glucansucrase fragment provides insight into evolution and product specificity of GH70 enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 21406–21411 10.1073/pnas.1007531107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ito K., Ito S., Shimamura T., Weyand S., Kawarasaki Y., Misaka T., Abe K., Kobayashi T., Cameron A. D., and Iwata S. (2011) Crystal structure of glucansucrase from the dental caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans. J. Mol. Biol. 408, 177–186 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Silverstein R., Voet J., Reed D., and Abeles R. H. (1967) Purification and mechanism of action of sucrose phosphorylase. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 1338–1346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mirza O., Skov L. K., Sprogøe D., van den Broek L. A., Beldman G., Kastrup J. S., and Gajhede M. (2006) Structural rearrangements of sucrose phosphorylase from Bifidobacterium adolescentis during sucrose conversion. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 35576–35584 10.1074/jbc.M605611200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsuura Y., Kusunoki M., Harada W., and Kakudo M. (1984) Structure and possible catalytic residues of Taka-amylase A. J. Biochem. 95, 697–702 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stam M. R., Danchin E. G., Rancurel C., Coutinho P. M., and Henrissat B. (2006) Dividing the large glycoside hydrolase family 13 into subfamilies: towards improved functional annotations of α-amylase-related proteins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 19, 555–562 10.1093/protein/gzl044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. James A. A., Blackmer K., and Racioppi J. V. (1989) A salivary gland-specific, maltase-like gene of the vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Gene 75, 73–83 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90384-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zheng L., Whang L. H., Kumar V., and Kafatos F. C. (1995) Two genes encoding midgut-specific maltase-like polypeptides from Anopheles gambiae. Exp. Parasitol. 81, 272–283 10.1006/expr.1995.1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ohashi K., Sawata M., Takeuchi H., Natori S., and Kubo T. (1996) Molecular cloning of cDNA and analysis of expression of the gene for α-glucosidase from the hypopharyngeal gland of the honeybee Apis mellifera L. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 221, 380–385 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gabriško M., and Janeček S. (2011) Characterization of maltase clusters in the genus Drosophila. J. Mol. Evol. 72, 104–118 10.1007/s00239-010-9406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gabriško M. (2013) Evolutionary history of eukaryotic α-glucosidases from the α-amylase family. J. Mol. Evol. 76, 129–145 10.1007/s00239-013-9545-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wongchawalit J., Yamamoto T., Nakai H., Kim Y. M., Sato N., Nishimoto M., Okuyama M., Mori H., Saji O., Chanchao C., Wongsiri S., Surarit R., Svasti J., Chiba S., and Kimura A. (2006) Purification and characterization of α-glucosidase I from Japanese honeybee (Apis cerana japonica) and molecular cloning of its cDNA. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70, 2889–2898 10.1271/bbb.60302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nishimoto M., Mori H., Moteki T., Takamura Y., Iwai G., Miyaguchi Y., Okuyama M., Wongchawalit J., Surarit R., Svasti J., Kimura A., and Chiba S. (2007) Molecular cloning of cDNAs and genes for three α-glucosidases from European honeybees, Apis mellifera L., and heterologous production of recombinant enzymes in Pichia pastoris. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 1703–1716 10.1271/bbb.70125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ngiwsara L., Iwai G., Tagami T., Sato N., Nakai H., Okuyama M., Mori H., and Kimura A. (2012) Amino acids in conserved region II are crucial to substrate specificity, reaction velocity, and regioselectivity in the transglucosylation of honeybee GH-13 α-glucosidases. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 76, 1967–1974 10.1271/bbb.120473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suthangkornkul R., Sirichaiyakul P., Sungvornyothin S., Thepouyporn A., Svasti J., and Arthan D. (2015) Functional expression and molecular characterization of Culex quinquefasciatus salivary α-glucosidase (MalI.). Protein Expr. Purif. 110, 145–150 10.1016/j.pep.2015.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nascimento N. A. D., Ferreira L. M., Romão T. P., Correia D. M. D. C., Vasconcelos C. R. D. S., Rezende A. M., Costa S. G., Genta F. A., de-Melo-Neto O. P., and Silva-Filha M. H. N. L. (2017) N-Glycosylation influences the catalytic activity of mosquito α-glucosidases associated with susceptibility or refractoriness to Lysinibacillus sphaericus. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 81, 62–71 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Daimon T., Taguchi T., Meng Y., Katsuma S., Mita K., and Shimada T. (2008) β-Fructofuranosidase genes of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: insights into enzymatic adaptation of B. mori to toxic alkaloids in mulberry latex. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15271–15279 10.1074/jbc.M709350200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Strobl S., Maskos K., Betz M., Wiegand G., Huber R., Gomis-Rüth F. X., and Glockshuber R. (1998) Crystal structure of yellow meal worm α-amylase at 1.64 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 278, 617–628 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sharma M., and Kumar V. (2019) Crystal structure of BinAB toxin receptor (Cqm1) protein and molecular dynamics simulations reveal the role of unique Ca(II) ion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 140, 1315–1325 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lin M. G., Chi M. C., Naveen V., Li Y. C., Lin L. L., and Hsiao C. D. (2016) Bacillus licheniformis trehalose-6-phosphate hydrolase structures suggest keys to substrate specificity. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 72, 59–70 10.1107/S2059798315020756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Holm L. (2019) Benchmarking fold detection by DaliLite v.5. Bioinformatics 35, 5326–5327 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang D., Li N., Lok S. M., Zhang L. H., and Swaminathan K. (2003) Isomaltulose synthase (PalI) of Klebsiella sp. LX3: crystal structure and implication of mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35428–35434 10.1074/jbc.M302616200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ravaud S., Robert X., Watzlawick H., Haser R., Mattes R., and Aghajari N. (2007) Trehalulose synthase native and carbohydrate complexed structures provide insights into sucrose isomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28126–28136 10.1074/jbc.M704515200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ravaud S., Robert X., Watzlawick H., Haser R., Mattes R., and Aghajari N. (2009) Structural determinants of product specificity of sucrose isomerases. FEBS Lett. 583, 1964–1968 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xu Z., Li S., Li J., Li Y., Feng X., Wang R., Xu H., and Zhou J. (2013) The structural basis of Erwinia rhapontici isomaltulose synthase. PLoS ONE 8, e74788 10.1371/journal.pone.0074788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watanabe K., Hata Y., Kizaki H., Katsube Y., and Suzuki Y. (1997) The refined crystal structure of Bacillus cereus oligo-1,6-glucosidase at 2.0 Å resolution: structural characterization of proline-substitution sites for protein thermostabilization. J. Mol. Biol. 269, 142–153 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hondoh H., Saburi W., Mori H., Okuyama M., Nakada T., Matsuura Y., and Kimura A. (2008) Substrate recognition mechanism of α-1,6-glucosidic linkage hydrolyzing enzyme, dextran glucosidase from Streptococcus mutans. J. Mol. Biol. 378, 913–922 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Møller M. S., Fredslund F., Majumder A., Nakai H., Poulsen J. C., Lo Leggio L., Svensson B., and Abou Hachem M. (2012) Enzymology and structure of the GH13_31 glucan 1,6-α-glucosidase that confers isomaltooligosaccharide utilization in the probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. J. Bacteriol. 194, 4249–4259 10.1128/JB.00622-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hobbs J. K., Jiao W., Easter A. D., Parker E. J., Schipper L. A., and Arcus V. L. (2013) Change in heat capacity for enzyme catalysis determines temperature dependence of enzyme catalyzed rates. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2388–2393 10.1021/cb4005029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Light S. H., Cahoon L. A., Halavaty A. S., Freitag N. E., and Anderson W. F. (2016) Structure to function of an α-glucan metabolic pathway that promotes Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16202 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shirai T., Hung V. S., Morinaka K., Kobayashi T., and Ito S. (2008) Crystal structure of GH13 α-glucosidase GSJ from one of the deepest sea bacteria. Proteins 73, 126–133 10.1002/prot.22044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Auiewiriyanukul W., Saburi W., Kato K., Yao M., and Mori H. (2018) Function and structure of GH13_31 α-glucosidase with high α-(1→4)-glucosidic linkage specificity and transglucosylation activity. FEBS Lett. 592, 2268–2281 10.1002/1873-3468.13126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shen X., Saburi W., Gai Z., Kato K., Ojima-Kato T., Yu J., Komoda K., Kido Y., Matsui H., Mori H., and Yao M. (2015) Structural analysis of the α-glucosidase HaG provides new insights into substrate specificity and catalytic mechanism. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 71, 1382–1391 10.1107/S139900471500721X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Caner S., Nguyen N., Aguda A., Zhang R., Pan Y. T., Withers S. G., and Brayer G. D. (2013) The structure of the Mycobacterium smegmatis trehalose synthase reveals an unusual active site configuration and acarbose-binding mode. Glycobiology 23, 1075–1083 10.1093/glycob/cwt044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Roy R., Usha V., Kermani A., Scott D. J., Hyde E. I., Besra G. S., Alderwick L. J., and Fütterer K. (2013) Synthesis of α-glucan in mycobacteria involves a hetero-octameric complex of trehalose synthase TreS and maltokinase Pep2. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 2245–2255 10.1021/cb400508k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang Y. L., Chow S. Y., Lin Y. T., Hsieh Y. C., Lee G. C., and Liaw S. H. (2014) Structures of trehalose synthase from Deinococcus radiodurans reveal that a closed conformation is involved in catalysis of the intramolecular isomerization. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 70, 3144–3154 10.1107/S1399004714022500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang J., Ren X., Wang R., Su J., and Wang F. (2017) Structural characteristics and function of a new kind of thermostable trehalose synthase from Thermobaculum terrenum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 7726–7735 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yamamoto K., Miyake H., Kusunoki M., and Osaki S. (2010) Crystal structures of isomaltase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in complex with its competitive inhibitor maltose. FEBS J. 277, 4205–4214 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Krissinel E., and Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Alonso-Gil S., Coines J., André I., and Rovira C. (2018) Conformational itinerary of sucrose during hydrolysis by retaining amylosucrase. Front. Chem. 7, 269 10.3389/fchem.2019.00269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jensen M. H., Mirza O., Albenne C., Remaud-Simeon M., Monsan P., Gajhede M., and Skov L. K. (2004) Crystal structure of the covalent intermediate of amylosucrase from Neisseria polysaccharea. Biochemistry 43, 3104–3110 10.1021/bi0357762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Woo E. J., Lee S., Cha H., Park J. T., Yoon S. M., Song H. N., and Park K. H. (2008) Structural insight into the bifunctional mechanism of the glycogen-debranching enzyme TreX from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28641–28648 10.1074/jbc.M802560200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang R., Li C., Williams L. K., Rempel B. P., Brayer G. D., and Withers S. G. (2009) Directed “in situ” inhibitor elongation as a strategy to structurally characterize the covalent glycosyl-enzyme intermediate of human pancreatic α-amylase. Biochemistry 48, 10752–10764 10.1021/bi901400p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Koropatkin N. M., and Smith T. J. (2010) SusG: a unique cell-membrane-associated α-amylase from a prominent human gut symbiont targets complex starch molecules. Structure 18, 200–215 10.1016/j.str.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Syson K., Stevenson C. E. M., Rashid A. M., Saalbach G., Tang M., Tuukkanen A., Svergun D. I., Withers S. G., Lawson D. M., and Bornemann S. (2014) Structural insight into how Streptomyces coelicolor maltosyl transferase GlgE binds α-maltose 1-phosphate and forms a maltosyl-enzyme intermediate. Biochemistry 53, 2494–2504 10.1021/bi500183c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sim L., Beeren S. R., Findinier J., Dauvillée D., Ball S. G., Henriksen A., and Palcic M. M. (2014) Crystal structure of the Chlamydomonas starch debranching enzyme isoamylase ISA1 reveals insights into the mechanism of branch trimming and complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 22991–23003 10.1074/jbc.M114.565044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kobayashi M., Saburi W., Nakatsuka D., Hondoh H., Kato K., Okuyama M., Mori H., Kimura A., and Yao M. (2015) Structural insights into the catalytic reaction that is involved in the reorientation of Trp238 at the substrate-binding site in GH13 dextran glucosidase. FEBS Lett. 589, 484–489 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Larsbrink J., Izumi A., Hemsworth G. R., Davies G. J., and Brumer H. (2012) Structural enzymology of Cellvibrio japonicus Agd31B protein reveals α-transglucosylase activity in glycoside hydrolase family 31. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 43288–43299 10.1074/jbc.M112.416511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Caputo A. T., Alonzi D. S., Marti L., Reca I. B., Kiappes J. L., Struwe W. B., Cross A., Basu S., Lowe E. D., Darlot B., Santino A., Roversi P., and Zitzmann N. (2016) Structures of mammalian ER α-glucosidase II capture the binding modes of broad-spectrum iminosugar antivirals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, E4630–E4638 10.1073/pnas.1604463113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Konno K., Ono H., Nakamura M., Tateishi K., Hirayama C., Tamura Y., Hattori M., Koyama A., and Kohno K. (2006) Mulberry latex rich in antidiabetic sugar-mimic alkaloids forces dieting on caterpillars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 1337–1341 10.1073/pnas.0506944103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brzozowski A. M., and Davies G. J. (1997) Structure of the Aspergillus oryzae α-amylase complexed with the inhibitor acarbose at 2.0 Å resolution. Biochemistry 36, 10837–10845 10.1021/bi970539i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Li C., Begum A., Numao S., Park K. H., Withers S. G., and Brayer G. D. (2005) Acarbose rearrangement mechanism implied by the kinetic and structural analysis of human pancreatic α-amylase in complex with analogues and their elongated counterparts. Biochemistry 44, 3347–3357 10.1021/bi048334e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tagami T., Yamashita K., Okuyama M., Mori H., Yao M., and Kimura A. (2013) Molecular basis for the recognition of long-chain substrates by plant α-glucosidases. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 19296–19303 10.1074/jbc.M113.465211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kim M. J., Lee S. B., Lee H. S., Lee S. Y., Baek J. S., Kim D., Moon T. W., Robyt J. F., and Park K. H. (1999) Comparative study of the inhibition of α-glucosidase, α-amylase, and cyclomaltodextrin glucanosyltransferase by acarbose, isoacarbose, and acarviosine-glucose. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 371, 277–283 10.1006/abbi.1999.1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kimura A., Lee J. H., Lee I. S., Lee H. S., Park K. H., Chiba S., and Kim D. (2004) Two potent competitive inhibitors discriminating α-glucosidase family I from family II. Carbohydr. Res. 339, 1035–1040 10.1016/j.carres.2003.10.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Li X., Shi L., Zhou Y., Xie H., Dai X., Li R., Chen Y., and Wang H. (2017) Molecular evolutionary mechanisms driving functional diversification of α-glucosidase in Lepidoptera. Sci. Rep. 7, 45787 10.1038/srep45787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Miyazaki T., Miyashita R., Nakamura S., Ikegaya M., Kato T., and Park E. Y. (2019) Biochemical characterization and mutational analysis of silkworm Bombyx mori β-1,4-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase and insight into the substrate specificity of β-1,4-galactosyltransferase family enzymes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 115, 103254 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Otwinowski Z., and Minor W. (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Battye T. G., Kontogiannis L., Johnson O., Powell H. R., and Leslie A. G. (2011) iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 271–281 10.1107/S0907444910048675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 10.1107/S0907444909047337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Keegan R. M., and Winn M. D. (2007) Automated search-model discovery and preparation for structure solution by molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 63, 447–457 10.1107/S0907444907002661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Vagin A., and Teplyakov A. (1997) MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 1022–1025 10.1107/S0021889897006766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., and Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 10.1107/S0907444996012255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., and Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 10.1107/S0907444910007493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Perrakis A., Morris R., and Lamzin V. S. (1999) Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463 10.1038/8263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chen V. B., Arendall W. B. 3rd, Headd J. J., Keedy D. A., Immormino R. M., Kapral G. J., Murray L. W., Richardson J. S., and Richardson D. C. (2010) MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 10.1107/S0907444909042073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Edgar R. C. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Robert X., and Gouet P. (2014) Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324 10.1093/nar/gku316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Saitou N., and Nei M. (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Letunic I., and Bork P. (2019) Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W256–W259 10.1093/nar/gkz239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank under accession codes 6LGA, 6LGB, 6LGC, 6LGD, 6LGE, 6LGF, 6LGG, 6LGH, and 6LGI. All other data are contained within the article.