INTRODUCTION

The health care industry is the largest employer in the USA. The health care workforce encompasses a range of occupations that vary widely by income, including home health aides, food service workers, clerical workers, nurses, physicians, and executives.1 These income differences may have important implications for health and longevity.2 However, to our knowledge, the relationship between income and mortality among health care workers (HCWs) has not been well-examined. Understanding this relationship is important given the growing role of the health care industry and the essential nature of health care work. To address this gap in the literature, we estimated the income-based mortality gradient among health care workers interviewed in a nationally representative survey over the period 2007–2014.

METHODS

We used public-use data from the National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS).3 We restricted our sample to participants interviewed between 2007 and 2014, the most recent NHIS waves in which participant mortality was tracked in the National Death Index (through December 31, 2015) and in which income categories remained consistent.3 We further restricted the sample to participants 30–64 years old (accounting for post-graduate training and typical retirement ages). Following Standard Industrial Classification codes, we defined health care workers as any individual working in hospitals or health services.

The main outcome was death from all-causes by December 31, 2015 (endline). The main exposure was self-reported annual family income, which is available in the NHIS as a categorical variable (denoting incomes under $34,999, $35,000–49,999, $50,000–74,999, $75,000–99,999, and $100,000 and above). We fitted logistic regression models to estimate the odds of mortality by income, adjusting for age (with polynomial terms to account for nonlinearity in mortality risk), sex, race/ethnicity, and interview year. We estimated models for non-HCWs as a point of comparison. Following prior work,2 we did not adjust for educational attainment; however, we did so in a sensitivity analysis. We used NHIS weights in analyses to account for complex survey design. All analyses were conducted using Stata v.15.1. Following University of Pennsylvania policy, Institutional Review Board protocol review was not required given the use of publicly available, deidentified data. This study was not supported by an external funding source.

RESULTS

Our sample consisted of 15,068 HCWs and 288,776 non-HCWs. While mean age at interview was similar across both groups of workers (46.6 vs. 46.0 years), HCWs were more likely to be female (80.9% vs. 50.4%), Black (18.1% vs. 12.1%), and to have completed some college education or higher (74.9% vs. 59.8%; Table 1). The average participant was followed for 4.1 years; 315 HCWs and 7429 non-HCWs died by endline.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Health care workers (N = 15,068) | Non-health care workers (N = 288,776) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 46.6 (10.1) | 46.0 (9.77) |

| Sex (N, weighted %) | ||

| Female | 12,286 (80.9) | 147,703 (50.4) |

| Male | 2782 (19.1) | 142,404 (49.6) |

| Race (N, weighted %) | ||

| White | 10,522 (76.1) | 221,509 (81.2) |

| Black | 3389 (18.1) | 42,476 (12.1) |

| Asian | 929 (6.2) | 20,862 (5.3) |

| Other | 228 (1.2) | 5140 (1.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 1907 (8.8) | 62,145 (14.9) |

| Non-Hispanic | 13,161 (91.2) | 226,631 (85.2) |

| Education (N, weighted %)a | ||

| Less than H.S. | 1002 (5.4) | 39,906 (11.1) |

| High school | 3121 (19.8) | 83,915 (29.1) |

| Some college | 7979 (54.6) | 110,219 (39.9) |

| College and above | 2938 (20.3) | 53,052 (19.9) |

| Income group, $ (N, weighted %) | ||

| 0–34,999 | 5008 (30.2) | 83,913 (26.0) |

| 35,000–49,999 | 2017 (13.5) | 40,178 (13.4) |

| 50,000–74,999 | 2659 (18.2) | 53,775 (18.9) |

| 75,000–99,999 | 1829 (12.7) | 39,123 (14.3) |

| 100,000+ | 3555 (25.4) | 71,786 (27.4) |

Descriptive statistics for 30–64-year-old health care and non-health care workers participating in the 2007–2014 National Health Interview Surveys. 1.7

aEducational attainment was available for 15,040 of the 15,068 health care workers in the sample and 285,763 of 288,776 non-health care workers

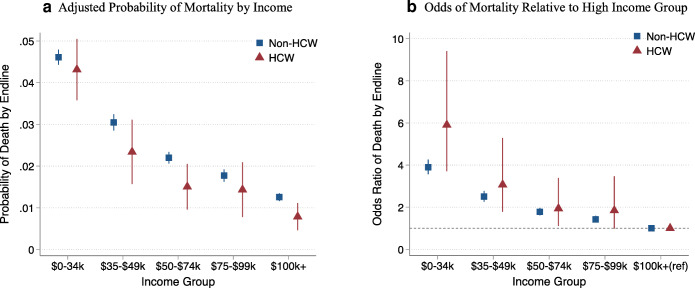

Adjusted mortality risk decreased with increasing income for both HCWs and non-HCWs (Fig. 1). The probability of death among HCWs in the lowest income group was 4.3% (95% CI, 3.6%, 5.1%) compared with 0.8% (95% CI, 0.5%, 1.1%) for the highest income group (panel a), reflecting a 5.9-fold higher odds of death (95% CI, 3.7, 9.4, p < 0.001; panel b). Income gradients in mortality were steeper for HCWs than non-HCWs (p = 0.061). Substantive findings remained unchanged after adjusting for education.

Figure 1.

Income-based gradients in mortality. Panel a presents estimates of the probability of death by endline (December 15, 2015) by NHIS income category, obtained from logistic regressions of a binary indicator for mortality against each income category (with income expressed in thousands of dollars), adjusting for a third-order polynomial of age, race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, other), sex (female, male), and interview year (binary indicators for each year over the period 2007–2014). Panel b presents odds ratios obtained from these models, using the highest income category ($100,000 or higher) as the reference group (the horizontal dashed line denotes equal odds, i.e., OR = 1). Models were estimated separately for health care workers (HCWs, red triangles) and non-health care workers (non-HCWs, blue squares). Vertical bars reflect 95% confidence intervals. All models used NHIS sample weights.

DISCUSSION

We found that mortality rates among HCWs decreased with income, and that the lowest-income HCWs had a nearly sixfold higher risk of death relative to the highest income HCWs. Jobs in the health care industry afford better benefits and opportunities for advancement,4 yet income-mortality gradients observed in this study were steeper than those for non-HCWs.

Our findings suggest that further growth in job opportunities for low-income HCWs is unlikely to mitigate widening income-based longevity gradients in the USA. This is particularly worrisome for underrepresented minorities and women, who comprise the bulk of low-income HCWs. These findings also have implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, given the intersecting risk factors of direct exposure, medical comorbidities, and poverty faced by low-income HCWs.5 More generally, given that healthy HCWs are critical for a well-functioning health system,6 reducing these disparities may improve health care delivery and quality.

Limitations of this study include the short follow-up period, the self-reported nature of the income data, and the lack of data to study mechanisms underlying the association between income and mortality. Nevertheless, the findings can inform efforts to promote the health and well-being of health care workers.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Himmelstein KEW, Venkataramani AS. Economic vulnerability among US female health care workers: potential impact of a $15-per-hour- minimum wage. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):198–205. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, Lin S, Scuderi B, Turner N, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blewett L, Rivera Drew J, King M, Williams K. IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 6.4. In: IPUMS, ed. Minneapolis, MN; 2019.

- 4.Dill J, Hodges MJ. Is healthcare the new manufacturing? Industry, gender, and “good jobs” for low-and middle-skill workers. Soc Sci Res. 2019;84:e102350. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Health insurance status and risk factors for poor outcomes with COVID-19 among U.S. health care workers: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2020 DOI: 10.7326/M20-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Davis K, Collins SR, Doty MM, Ho A, Holmgren AL. Health and productivity among US workers. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2005;856(856):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]