Abstract

Objective

To estimate the average medical care cost of fatal and non-fatal injuries in the USA comprehensively by injury type.

Methods

The attributable cost of injuries was estimated by mechanism (eg, fall), intent (eg, unintentional), body region (eg, head and neck) and nature of injury (eg, fracture) among patients injured from 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2015. The cost of fatal injuries was the multivariable regression-adjusted average among patients who died in hospital emergency departments (EDs) or inpatient settings as reported in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Emergency Department Sample and National Inpatient Sample, controlling for demographic (eg, age), clinical (eg, comorbidities) and health insurance (eg, Medicaid) factors. The 1-year attributable cost of non-fatal injuries was assessed among patients with ED-treated injuries using MarketScan medical claims data. Multivariable regression models compared total medical payments (inpatient, outpatient, drugs) among non-fatal injury patients versus matched controls during the year following injury patients’ ED visit, controlling for demographic, clinical and insurance factors. All costs are 2015 US dollars.

Results

The average medical cost of all fatal injuries was approximately $6880 and $41 570 per ED-based and hospital-based patient, respectively (range by injury type: $4764–$10 289 and $31 912–$95 295). The average attributable 1-year cost of all non-fatal injuries per person initially treated in an ED was approximately $6620 (range by injury type: $1698–$80 172).

Conclusions and relevance

Injuries are costly and preventable. Accurate estimates of attributable medical care costs are important to monitor the economic burden of injuries and help to prioritise cost-effective public health prevention activities.

INTRODUCTION

Injuries are a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the USA. In clinical and public health terms, injuries comprise a range of unintentional and violence-related outcomes, for example, MVCs, drug poisoning, falls, suicide and assaults. Unintentional injuries are the third leading cause of death, and along with suicide contributed to decreases in overall life expectancy during 2016 and 2017.1 There are 30 million emergency department (ED) visits for non-fatal injuries each year,2 and US medical expenditures for injury and poisoning exceed $133 billion annually.3

Medical care cost estimates are important to monitor the economic burden of injuries and help to prioritise cost-effective public health prevention activities. Existing comprehensive estimates of medical care cost for injuries by injury type—mechanism (eg, fall), intention (eg, unintentional), body region (eg, head and neck) and nature of injury (eg, fracture)—were calculated using primarily hospital-based data from 2010,4 and have been applied in numerous assessments of the economic and public health impact of violence and unintentional injuries.5-10 The aim of this study was to estimate the average medical care cost of fatal and non-fatal injuries in the USA comprehensively by injury type.

METHODS

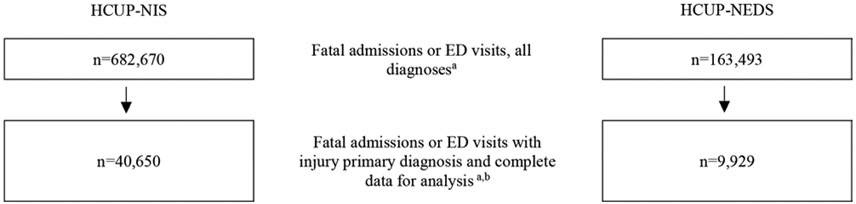

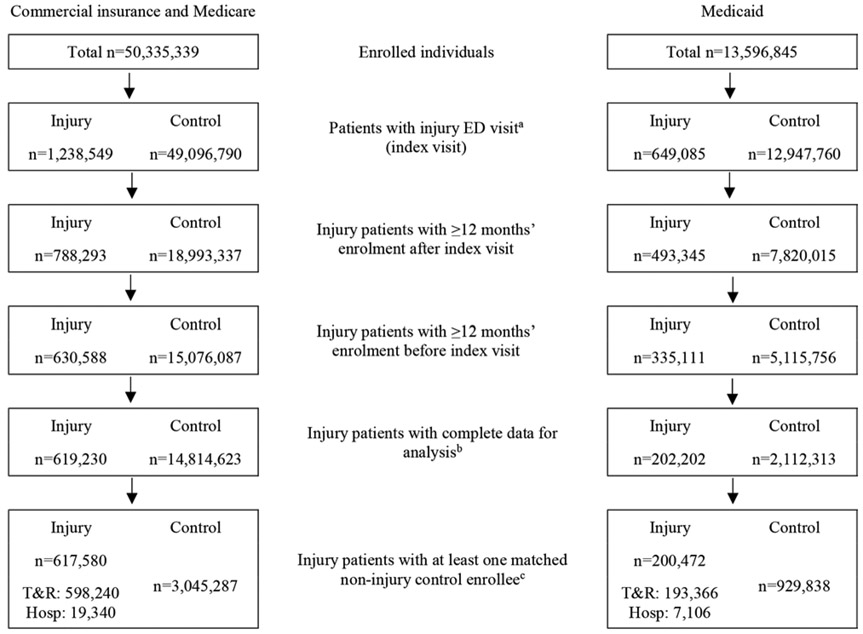

Medical cost estimates from the perspective of the healthcare payer for fatal and non-fatal injuries treated from 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2015 were derived from two publicly available data sources—Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) (www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov) hospital discharge databases (figure 1) and MarketScan (www.ibm.com) medical claims databases (figure 2). The time horizon for fatal costs was the ED visit or hospitalisation which ended in death, and the time horizon for non-fatal costs was 1 year. Medical costs were estimated by injury mechanism and intent11 (table 1 for fatal and table 2 for non-fatal) and body region and nature of injury12 (table 3 for fatal and table 4 for non-fatal) using established classifications based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes11 and External Cause of Injury codes (E-codes). Both types of injury classification—mechanism/intent and body region/nature of injury—are important in different contexts, and costs per injury type are not comparable across classifications. For example, patients with different injury types by body region (eg, torso vs head) can have the same injury type by mechanism (eg, motor vehicle traffic) or vice versa. Transition to ICD-10-CM coding for medical payments occurred outside the study period, on 1 October 2015.12 ICD-10-CM injury classification frameworks are proposed and will be finalised in the future (www.cdc.gov/nchs/injury). Costs are presented in 2015 US dollars (not inflated from 2014 to 2015 data source values).

Figure 1.

Sample selection of emergency department visits and admissions for fatal injuries in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample and Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, from 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2015. aSurvey-weighted number of admissions or ED visits. bInjury diagnosis for the emergency department visit (HCUP-NEDS) or inpatient admission (HCUP-NIS) defined by an injury code (ICD-9-CM) in the primary diagnosis field. Complete data for analysis included admission or ED visit charges, sex (male, female), age, race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, other, unknown; HCUP-NIS records only, not reported in HCUP-NEDS), and primary payer for admission or ED visit (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, other (e.g., worker’s compensation, other government programmes), no charge, unknown). Data sets were reweighted following exclusion of records with missing data (eg, charges) to maintain data set representativeness. HCUP-NEDS, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Emergency Department Sample; HCUP-NIS, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Figure 2.

Sample selection of patients with non-fatal ED-treated injuries in MarketScan, from 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2015. aDefined as ICD-9-CM injury diagnosis in the primary diagnosis field from 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2015 during ED visit (variable: SVCSCAT=xxx20) plus facility payment (variable: FACPROF) attributed to the injury diagnosis as identified in MarketScan Outpatient Services (ie, primarily treat-and-release patients) and Inpatient Services (ie, patients with hospitalisation following ED visits) databases (https://www.ibm.com/us-en/marketplace/marketscanresearch-databases). bComplete data for analysis included medical cost in the 12 months following ED injury visit (including index injury date) >$0 (patients with injury only), sex (male, female), age (years), race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, other, unknown; Medicaid enrollees only), region of residence (based on metropolitan statistical area; records with ‘unknown’ but not missing value included; commercial insurance and Medicare supplemental enrollees only), type of health plan (eg, health management organisation) and basis for Medicaid eligibility (eg, foster care; Medicaid enrollees only). cTo ensure controls had the appropriate observation timeline—24 months surrounding injury patients’ index visit month—all potential control enrollees (non-injury) in the 2015 MarketScan Enrolment Detail table were first randomly assigned an index month (ie, values 1–12) and excluded if lacking 24 months of insurance enrolment surrounding that index month. Next, 1:5 injury patient to control enrollee match (SAS V.9.4 gmatch) was requested based on index month (ie, month of index injury ED visit for patients with injury and randomly assigned monthly for control enrollees), insurance type (commercial, Medicare or Medicaid), enrollee age (as reported in the data source for commercial insurance and Medicare supplemental patients, and for Medicaid enrollees based on reported year of birth), sex (male/female), race/ethnicity (reported in the data source for Medicaid enrollees only), region of residence (reported in the data source for commercial insurance and Medicare supplemental enrollees only), type of health plan, mental health and substance abuse treatment coverage (commercial insurance enrollees only), drug coverage, Medicare dual eligibility (Medicaid enrollees only), comorbidity count (0, 1, 2+ diagnosed in the 12 months prior to the index injury date (based on Elixhauser Comorbidity Software V.3.7) in any clinical location reported in MarketScan), and basis for Medicaid eligibility (Medicaid enrollees only). ED, emergency department; Hosp, hospitalised (inpatient); ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; T&R, treated and released.

Table 1.

Adjusted mean cost of ED visits and admissions for fatal injuries by mechanism and intent (total n=40 650 survey-weighted)

| Mechanism | Fatality location | Unintentional | Self-inflicted | Assault | undetermined | Other | Unknown | All intents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut/pierce | ED | $6782 | $7115 | |||||

| Hospital | $44 244 | $51 946 | $52 110 | |||||

| Drowning/submersion | ED | $6351 | $6462 | |||||

| Hospital | $55 968 | $59 294 | ||||||

| Fall | ED | $7207 | $7317 | |||||

| Hospital | $36 568 | $36 440 | ||||||

| Fire/burn | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $41 682 | $41 985 | ||||||

| Fire/flame | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $42 203 | $42 452 | ||||||

| Hot object/substance | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $38 399 | $38 735 | ||||||

| Firearm | ED | $6660 | $6966 | $6682 | $6726 | $6644 | ||

| Hospital | $51 197 | $42 179 | $50 636 | $44 845 | $44 887 | |||

| Machinery | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | ||||||||

| Motor vehicle traffic | ED | $6989 | $7160 | |||||

| Hospital | $46 063 | $48 157 | ||||||

| Occupant | ED | $7138 | $7316 | |||||

| Hospital | $45 841 | $47 934 | ||||||

| Motorcyclist | ED | $6793 | $6957 | |||||

| Hospital | $47 249 | $49 549 | ||||||

| Pedal cyclist | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $49 305 | $51 420 | ||||||

| Pedestrian | ED | $6947 | $7117 | |||||

| Hospital | $45 195 | $46 901 | ||||||

| Unspecified motor vehicle | ED | $6650 | $6824 | |||||

| Hospital | $47 129 | $49 861 | ||||||

| Other pedal cyclist | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $46 237 | $47 073 | ||||||

| Other pedestrian | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $40 626 | $41 629 | ||||||

| Other transport | ED | $7007 | $7224 | |||||

| Hospital | $45 024 | $46 663 | ||||||

| Natural/environmental | ED | $6903 | $6987 | |||||

| Hospital | $47 517 | $48 894 | ||||||

| Bites and stings | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | ||||||||

| Overexertion | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | ||||||||

| Poisoning | ED | $7163 | $7113 | $7199 | $6507 | |||

| Hospital | $50 853 | $48 210 | $51 490 | $40 646 | ||||

| Struck by/against | ED | $7220 | ||||||

| Hospital | $42 392 | $52 043 | $50 987 | |||||

| Suffocation | ED | $6662 | $6590 | $6155 | ||||

| Hospital | $40 550 | $56 838 | $40 043 | |||||

| Other specified, classifiable | ED | $6897 | $6609 | $6537 | ||||

| Hospital | $43 067 | $39 961 | $63 521 | $48 203 | ||||

| Other specified, NEC | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $40 694 | $51 297 | $48 954 | |||||

| Unspecified | ED | $6997 | $7176 | |||||

| Hospital | $44 179 | $56 071 | $50 569 | |||||

| Adverse effects | ED | |||||||

| Hospital | $39 254 | $65 409 | ||||||

| E-code missing | ED | $6776 | $7017 | |||||

| Hospital | $41 812 | $43 541 | ||||||

| All mechanisms | ED | $7150 | $5890 | $6921 | $6106 | $7961 | $7004 | $6884 |

| Hospital | $41 082 | $34 958 | $52 787 | $32 255 | $65 525 | $43 215 | $41 605 |

Number of records, survey-weighted number, and simple mean, SE and 95% CI for all cost estimates reported in online supplementary tables S1 and S3.

Blank cells indicate average cost not calculated due to low number of observations (zero visits or admissions or relative SE >30% or SE=0) in the data source. ‘All mechanisms’ model controlled for mechanism. ‘All intents’ model controlled for intent. ‘All’/’All’ model controlled for both.

Source data: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample and Nationwide Emergency Department Sample. Injury classification in this table based on the ICD-9-CM E-code matrix (www.cdc.gov/nchs/injury/injury_tools.htm).

E-code, External Cause of Injury code; ED, emergency department; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; NEC, not elsewhere classifiable; SE, Standard error.

Table 2.

Adjusted mean cost of ED visits and admissions for fatal injuries by body region and nature of injury (total n=40 650 survey-weighted)

| Body region | Fatality location | Fracture | Internal | Open wound | Blood vessels | Contusion or superficial |

Crush | Burns | unspecified | System-wide and late effects |

All nature of injury | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | Traumatic brain injury | ED | $7001 | $6986 | $9141 | |||||||

| Hospital | $44 739 | $40 273 | $42 545 | |||||||||

| Other head, face, neck | ED | $6735 | $7044 | $5608 | ||||||||

| Hospital | $43 473 | $44 642 | $50 111 | $43 217 | $32 886 | $73 042 | ||||||

| Total | ED | $5843 | $5954 | $5597 | $5937 | $6373 | ||||||

| Hospital | $42 274 | $38 586 | $41 984 | $47 074 | $40 455 | $31 912 | $41 345 | |||||

| Spine and back | Spinal cord | ED | ||||||||||

| Hospital | $42 284 | $44 007 | $44 731 | |||||||||

| Vertebral column | ED | $6341 | ||||||||||

| Hospital | $36 799 | $39 685 | ||||||||||

| Total | ED | $6353 | ||||||||||

| Hospital | $36 846 | $42 494 | $40 710 | |||||||||

| Torso | Torso | ED | $7400 | $6937 | $6644 | $7362 | $6821 | $8374 | ||||

| Hospital | $35 514 | $44 941 | $45 456 | $36 863 | $44 722 | $47 001 | ||||||

| Extremities | Upper extremities | ED | $6577 | $5671 | ||||||||

| Hospital | $36 332 | $45 049 | $52 325 | |||||||||

| Lower extremities | ED | $7125 | $6818 | |||||||||

| Hospital | $35 123 | $33 378 | $45 280 | $38 832 | ||||||||

| Total | ED | $6334 | $5583 | $5965 | ||||||||

| Hospital | $34 151 | $38 660 | $46 554 | $33 368 | $42 562 | $39 682 | ||||||

| Unclassifiable by site | Other or multiple | ED | $6540 | $6818 | $5643 | |||||||

| Hospital | $42 684 | $95 295 | ||||||||||

| System-wide | ED | $6861 | $4764 | |||||||||

| Hospital | $50 300 | $32 934 | ||||||||||

| Total | ED | $5343 | $5749 | $5659 | $4915 | |||||||

| Hospital | $40 850 | $46 534 | $34 123 | |||||||||

| All | All body regions | ED | $7656 | $8695 | $6759 | $10 289 | $6419 | $6693 | $5872 | $4782 | $6885 | |

| Hospital | $41 517 | $43 047 | $52 886 | $63 067 | $41 660 | $68 670 | $61 036 | $55 398 | $33 081 | $41 541 |

Number of records, survey-weighted number, and simple mean, SE and 95% CI for all cost estimates reported in online supplementary tables S2 and S4.

Blank cells indicate average cost not calculated due to low number of observations (zero visits or admissions or relative SE >30% or SE=0) in the data source. Some nature of injury categories not shown in this table due to no data: dislocation, sprains and strains, amputations, nerves. ‘All body regions’ model controlled for body region. ‘All nature of injury’ model controlled for nature of injury. ‘All’/’All’ model controlled for both.

Source data: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project National Inpatient Sample and Nationwide Emergency Department Sample. Injury classification in this table based on the ICD-9-CM Barell matrix (www.cdc.gov/nchs/injury/injury_tools.htm). ED, emergency department; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; SE, Standard error.

Table 3.

Estimated 12-month attributable cost of medical care following emergency department treatment for all patients with non-fatal injuries by mechanism and intent (n=818 053 injury; n=3 975 125 control)

| Mechanism | Unintentional | Self-inflicted | Assault | Undetermined | Other | Unknown | All intents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut/pierce | $3119 | $17 320 | $17 709 | $3435 | $3322 | ||

| Drowning/submersion | $12 940 | $13 355 | |||||

| Fall | $9399 | $5406 | $9399 | ||||

| Fire/burn | $7260 | $14 002 | $7431 | ||||

| Fire/flame | $11 552 | $12 325 | |||||

| Hot object/substance | $6200 | $6224 | |||||

| Firearm | $22 805 | $37 435 | $21 030 | $24 859 | |||

| Machinery | $5340 | $5340 | |||||

| Motor vehicle traffic | $9403 | $9408 | |||||

| Occupant | $7396 | $7396 | |||||

| Motorcyclist | $20 415 | $20 415 | |||||

| Pedal cyclist | $14 193 | $14 193 | |||||

| Pedestrian | $19 440 | $19 440 | |||||

| Unspecified motor vehicle | $12 054 | $12 054 | |||||

| Other pedal cyclist | $6109 | $6109 | |||||

| Other pedestrian | $9484 | $9484 | |||||

| Other transport | $11 089 | $11 090 | |||||

| Natural/environmental | $5838 | $5833 | |||||

| Bites and stings | $3307 | $3307 | |||||

| Overexertion | $5251 | $5251 | |||||

| Poisoning | $9723 | $17 563 | $13 521 | $12 783 | |||

| Struck by/against | $3989 | $6828 | $10 293 | $4146 | |||

| Suffocation | $8331 | $19 579 | $8904 | ||||

| Other specified, classifiable | $4185 | $4670 | $1698 | $4207 | |||

| Other specified, NEC | $5295 | $11 121 | $6294 | $5508 | $5411 | ||

| Unspecified | $7032 | $26 868 | $9047 | $8746 | $7434 | ||

| Adverse effects | $15 428 | $15 428 | |||||

| E-code missing | $6508 | $6508 | |||||

| All mechanisms | $6712 | $18 331 | $7460 | $10 217 | $13 967 | $6508 | $6658 |

Number of records, survey-weighted number, and simple mean and 95% CI for all cost estimates demonstrated in online supplementary table 5 S5.

Blank cells indicate average cost not calculated due to low number of observations (<21 patients with injury) in the data source. ‘All mechanisms’ model controlled for mechanism. ‘All intents’ model controlled for intent. ‘All’/’All’ model controlled for both.

Source data: MarketScan (Inpatient Services, Inpatient Admissions, Outpatient Services, Outpatient Pharmaceutical Claims). Injury classification in this table based on the ICD-9-CM E-code matrix (www.cdc.gov/nchs/injury/injury_tools.htm).

E-code, External Cause of Injury code; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; NEC, not elsewhere classifiable.

Table 4.

Estimated 12-month attributable cost of medical care following emergency department treatment for all patients with non-fatal injuries by body region and nature of injury (n=818 053 injury; n=3 975 125 control)

| Body region | Body region | Fracture | dislocation | Sprains and strains |

Internal | Open wound |

Amputations | Blood vessels |

Contusion or superficial |

Crush | Burns | Nerves | Unspecified | System-wide and late effects |

All nature of injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck | Traumatic brain | $40 454 | $7832 | $9339 | |||||||||||

| injury | |||||||||||||||

| Other head, face, | $14 334 | $4697 | $8767 | $3790 | $14 693 | $4497 | $11 034 | $6379 | $6058 | $4948 | |||||

| neck | |||||||||||||||

| Total | $18 751 | $4697 | $8767 | $7832 | $3790 | $14 693 | $4497 | $11 034 | $4849 | $6058 | $5565 | ||||

| Spine and back | Spinal cord | $80 172 | $34 546 | $51 317 | |||||||||||

| Vertebral column | $30 584 | $22 263 | $5080 | $7311 | |||||||||||

| Total | $30 957 | $22 263 | $5080 | $34 546 | $7395 | ||||||||||

| Torso | Torso | $19 254 | $10 055 | $4711 | $35 223 | $6424 | $6306 | $11 219 | $6232 | $8906 | |||||

| Extremities | Upper extremities | $9936 | $6010 | $4214 | $3416 | $8531 | $11 505 | $4143 | $2775 | $4961 | $9259 | $4305 | $5853 | ||

| Lower extremities | $16 075 | $13 393 | $5035 | $4202 | $46 251 | $14 161 | $5397 | $5829 | $8894 | $6419 | $7218 | ||||

| Total | $12 128 | $7535 | $4760 | $3668 | $10 025 | $11 011 | $4767 | $3429 | $5912 | $9259 | $5336 | $6468 | |||

| Unclassifiable by site | Other or multiple | $11 590 | $12 502 | $4990 | $11 707 | $6721 | $4438 | $5918 | $3893 | $7620 | $6694 | ||||

| System-wide | $7630 | $7630 | |||||||||||||

| Total | $11 590 | $12 502 | $4990 | $11 707 | $6721 | $4438 | $5918 | $3893 | $7620 | $7630 | $7407 | ||||

| All body regions | All body regions | $13 856 | $7597 | $4878 | $9297 | $3856 | $9876 | $20 129 | $4892 | $3465 | $7395 | $7365 | $5869 | $7630 | $6587 |

Number of records (patients with injury and control enrollees), and simple mean and 95% CI for all cost estimates demonstrated in online supplementary table 6.

Blank cells indicate average cost not calculated due to low number of observations (<21 patients with injury) in the data source. ‘All nature of injury’ model controlled for nature of injury. ‘All body regions’ model controlled for body region of injury. ‘All/All’ model controlled for nature and body region of injury.

Source data: MarketScan (Inpatient Services, Inpatient Admissions, Outpatient Services, Outpatient Pharmaceutical Claims). Injury classification in this table based on the ICD-9-CM Barell matrix (www.cdc.gov/nchs/injury/injury_tools.htm). ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Fatal injuries

Data

The medical cost of fatal injuries was assessed among patients with a primary diagnosis of injury11 who died in a hospital ED or inpatient setting as reported in the HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (HCUP-NEDS) and National Inpatient Sample (HCUP-NIS) (figure 1). These data sources can produce nationally representative estimates of ED visits and inpatient admissions to community hospitals. HCUP-NEDS and HCUP-NIS demonstrate hospital facility charges per ED visit or admission, edited to exclude extreme dollar values.

Hospital charges are distinct from payments hospitals receive from individuals or health insurance companies and typically do not include physician (or professional) fees, ambulance fees, nor coroner/medical examiner (C/ME) fees—each separately estimated for this study. The estimated medical cost per fatal injury in an ED or inpatient hospital was calculated as the facility charge value from HCUP-NEDS or HCUP-NIS multiplied by an HCUP hospital-specific cost-to-charge ratio (CCR) and a diagnosis-specific professional fee ratio (PFR), plus estimated ambulance and C/ME costs—each element as detailed below.

Annual, all-payer, hospital-specific, inpatient CCRs are calculated by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and published for use with HCUP-NIS (www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov). When hospital-specific CCR was unavailable (approximately 2% of HCUP-NIS analysed injury records; data not shown), the authors used multiple imputation to estimate CCR based on selected hospital characteristics (regional and urban/rural location, teaching status and bed size).13 This yielded an average inpatient CCR of 0.337 (data not shown), suggesting hospitals’ facility cost was approximately 34% of the facility charge value among analysed records. HCUP does not publish CCR for NEDS data.14 The authors estimated CCR for HCUP-NEDS records by applying the average inpatient CCR among analysed HCUP-NIS records based on the aforementioned hospital characteristics; for example, an injury ED visit at an urban teaching hospital in the Midwest was assigned the average inpatient CCR for all hospitals in the HCUP-NIS analysis sample with those criteria.13 The average CCR applied to HCUP-NEDS records was 0.396 (data not shown). PFR was assigned to injury records by primary three-digit ICD-9-CM code and primary payer (Medicare and Medicaid were assigned Medicaid-specific PFR, and private insurance, self-pay, no charge, other and missing payers were assigned commercial insurance-specific PFR) separately for ED visits and admissions using published estimates (from 2012, the most recent available).15 If PFR was not available for a given ICD-9-CM code, the authors applied the all-diagnosis, payer-specific adjusted average PFR.15

Each fatal injury in an ED or inpatient setting was also assigned an estimated average cost of ambulance transport and C/ME (including autopsy) costs. An average ambulance cost of $70 was based on national survey data (2015 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, the most recent available) indicating 15.1% of ED visits (all diagnoses) have ambulance transport16 at a nationwide estimated cost of $463 per ambulance transport (inflated17 from the reported 2010 US dollar cost of $429).18 Majority of US states require death investigation for deaths due to injury/casualty, suicide or violence.19 An average C/ME cost estimate of $929 (inflated20 from the reported 2004 US dollar cost of $752) was based on a nationwide survey of C/ME offices indicating a combined annual budget of $718.5 million in 2004, when such offices were referred 956 000 deaths.21

Analysis

The authors used SAS V.9.4 to derive patient samples and Stata V.14 for regression models. The adjusted average cost per fatal injury in an ED or inpatient setting was estimated using generalised linear models (GLM) (Stata V.14 svy glm family(gamma) link(log)) with postestimation calculation of the average of model-predicted values (in dollar units, using Stata V.14 margins) per injury type (ie, by mechanism, intent, body region and nature of injury). With total ED or admission (including any preceding ED) estimated medical cost as the dependent variable, the regression models controlled for patients’ sex (male, female), age (years), race/ethnicity (hospitalisations only; white, black, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native American, other, unknown), number of comorbidities (0, 1, 2+) diagnosed on the visit or admission record (based on Elixhauser Comorbidity Software V.3.7; www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov) and primary payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, other (e.g., worker’s compensation, other government programmes), no charge, unknown). Injury type elements were included as covariates as relevant (eg, the model of costs among all patients with fatal cut/pierce (mechanism) injuries controlled for injury intent—unintentional, self-inflicted, assault, undetermined, other or unknown). Based on standard US death certificate reporting on place of death, adjusted average costs per injury type are reported here in terms of whether a patient died in an ED or inpatient setting (table 1 for mechanism and intent and table 2 for body region and nature of injury). The number of analysed records, estimated simple mean cost and 95% CI for simple and regression-adjusted mean costs per injury type are reported in online supplementary tables S1-S4.

Non-fatal injuries

Data

The estimated attributable 1-year medical cost of non-fatal injuries was assessed among patients with ED-treated injuries as reported in the MarketScan Outpatient Services (primarily treat-and-release) and Inpatient Services (hospitalisation following ED treatment) databases. MarketScan includes hundreds of millions of covered lives based on data from large employers, health plans, and government and public organisations, including some state Medicaid payers, and is not nationally representative. Patients with commercial health insurance (including Medicare supplemental plans for enrollees >64 years old) and Medicaid were analysed based on their first chronological ED visit during the study period with a primary visit diagnosis of injury--or, index injury ED visit (figure 2). Because these databases can have more than one primary diagnosis listed per patient per ED visit, the primary visit diagnosis was defined as the primary diagnosis on the ED claim record to which facility charges for the visit were assigned. Patients admitted following the index injury ED visit were identified by an admission record (ie, MarketScan Inpatient Admissions database) on the date of or day following the index injury ED visit. The total 1-year medical payments were the sum of medical claims (reported in Market-Scan Outpatient Services, Inpatient Admissions—an aggregated version of Inpatient Services data—and Outpatient Pharmaceutical Claims databases) during the 365 days following (and including) each injury patient’s index injury ED visit date (ie, varying observation dates during 2014–2016 per patient with injury). Negative dollar value payments can exist in medical claims data (eg, adjustments). The authors excluded injury patients with ≤$0 total payments for the total 1-year observation period, as well as patients with capitated insurance payment plans (fee-for-service payments are presumed to reflect the cost of care associated with particular diagnoses in medical claims databases, while payments for patients with capitated plans likely do not).

To estimate the combined cost of acute and follow-up medical care attributable to non-fatal injuries, the total 1-year medical payments of patients with injury were compared with total 1-year payments among control enrollees with no injuries during the observation period. Patients with injury were matched to controls (SAS V.9.4 gmatch) 1:5 using MarketScan Enrollment Detail tables (match methods in figure 2 notes). Health insurance enrollees with $0 medical payments can exist in medical claims data—for example, no medical visits during a given observation period—and enrollees observed for a specific period can have negative total payment values (eg, adjustments for services prior to the observation period). The total 1-year medical payments for control enrollees were set to a minimum of $0. Among combined patients with injury and controls, the 99th percentile for the total 1-year medical payments was $117 414 and the highest value was $4.8 million; therefore, the top one percentile was top-coded to the 99th percentile value for analysis.22Top-coding is a common approach when medical payments—sometimes highly skewed due to a small number of patients with very high costs—are dependent variables in a regression model.22

Analysis

The 1-year attributable cost of non-fatal injuries was estimated using individual two-part models (Stata V.14 twopm firstpart(logit) secondpart (glm, family (gamma) link(log)) vce (robust)) per injury type (mechanism, intent, body region and nature of injury), with injury patients’ and matched controls’ total 1-year medical payments starting from the injury patient’s index injury ED visit date as the dependent variable. A two-part model accommodated control enrollees with $0 medical payments during the observation period—in the first part, a logistic regression model predicts the probability of >$0 medical payments, and in the second part a GLM model assesses costs among patients with >$0 payments. The regression models controlled for all matching factors (eg, patient age, sex and so on) as covariates in both the logistic and GLM parts. Because all patients with injury had >$0 total 1-year medical payments, the two-part model can accommodate an injury covariate (ie, identifying patients with injury) in the GLM, but not logistic, part of the modelling approach. The regression-adjusted marginal cost of non-fatal injuries by type was estimated as the marginal effect of the injury covariate (in dollar units, using postestimation Stata V.14 margins, dydx (injury)) among all observations (patients with injury and controls).

Results are reported by injury type (table 3 for mechanism and intent and table 4 for body region and nature of injury). The number of analysed patients with injury and controls, simple mean and 95% CIs for total 1-year medical payments, and modelled injury cost are reported in online supplementary tables S5 and S6. The online supplementary file also demonstrates results for two mutually exclusive subgroups of patients with injury: patients treated and released (T&R) from the index injury ED visit and patients admitted after the index injury ED visit (patient counts in figure 2) (online supplementary tables S7-S10). Group characteristics of patients with injury versus matched controls (eg, average age) are also reported (online supplementary table S11).

RESULTS

The estimated average attributable medical cost of fatal injuries (all types combined) in ED and inpatient settings was approximately $6880 and $41 570, respectively—these are median values between the modestly different cost results observed among the same patients (n=9929 and n=40 650 survey-weighted) depending on whether costs per injury type were modelled by mechanism and intent (table 1; $6884 and $41 605) or body region and nature of injury (table 2; $6885 and $41 541). The cost per injury fatality in an ED ranged from $4764 (95% CI 3913 to 5615; system-wide injuries) to $10 289 (95% CI 8210 to 12 368; blood vessel injuries), and the range per injury fatality in inpatient settings was $31 912 (95% CI 29 123 to 34 702; unspecified head and neck injuries) to $95 295 (95% CI 74 733 to 115 857; other or multiple injuries) (tables 1 and 2 for point estimates; online supplementary tables S1-S4 for 95% CIs).

The estimated average 1-year attributable medical cost of non-fatal injuries (all types combined) initially treated in an ED was approximately $6620—again, this is the median for this measure among the same patients (n=818 053 injury, n=3 975 125 control) depending on whether costs per injury type were modelled by mechanism and intent (table 3; $6658) or body region and nature of injury (table 4; $6587). The cost per non-fatal injury type ranged from $1698 (95% CI 421 to 2974; other specified, classifiable injuries of undetermined intent) to $80 172 (95% CI 46 917 to 113 427; spinal cord fractures) (tables 3 and 4 for point estimates; online supplementary tables S5-S6 for 95% CIs). The comparable costs among ED T&R versus ED then admitted patients were approximately $5580 and $49 670, respectively (online supplementary tables S7-S10). Comparable ranges by injury type among ED T&R patients were $1484 (95% CI 281 to 2687; other specified, classifiable injuries of undetermined intent) to $40 373 (95% CI 24 874 to 55 873; lower extremity amputations) and from $15 607 (95% CI 7805 to 23 409; upper extremity dislocation) to $107 400 (95% CI 49 706 to 165 094; firearm assault) among admitted patients (online supplementary tables S7-S10).

DISCUSSION

This study generated updated medical care cost estimates for US fatal and non-fatal injuries comprehensively by injury type. Where sample size permitted, costs were estimated for each type in two common injury classifications—mechanism/intent and body region/nature of injury. This breadth and specificity of estimated costs were made possible through large, nationally representative (HCUP) or multistate (MarketScan) databases containing information on tens to hundreds of thousands (survey-weighted) of patients with injury, as well as computing power to facilitate hundreds of consecutive regression models using different patient samples to estimate attributable average costs. Where previous estimates of medical costs by injury type4 relied primarily on 1 year of hospital-based data, this study observed medical care payments for all clinical settings for 1 year among patients with non-fatal ED-treated injuries, and compared such payments with non-injury insurance enrollees to estimate the total 1-year attributable cost of injuries.

The range of injury types depicted in the two injury classification schemes and the range of outcomes (fatal and non-fatal) assessed here created a broad range of estimated average medical cost values by injury type—from approximately $1700 (non-fatal, ED-treated other specified, classifiable, injuries of undetermined intent; table 2) to approximately $95 300 (fatal, inpatient-treated other or multiple/unclassifiable by site injuries; table 3). For context, in 2016 the estimated simple average costs of an ED visit and hospital admission (all diagnoses, all dispositions) were $1917 and $20 929, respectively, reflecting the nationally representative cost among patients aged <65 years with employer-sponsored health insurance.23 The higher estimated costs in this study for some injury ED visits and admissions are likely due to injury severity among visits and admissions ending in death, the longer duration and scope of assessed services and costs for non-fatal injuries, this study’s inclusion of older (>64 years) patients, and presumably the higher prevalence of surgical services among patients with injury (the 2016 average cost of surgery admission from the aforementioned comparative source was more than double the cost of medical admission23).

In presenting estimated costs for the two injury classification schemes in their entirety (tables 1-4), this study’s results highlight that many injury types are uncommon, and therefore medical costs for such types may be best approximated through aggregated categories, for example, combined intent categories for a given mechanism. In such instances, this analysis has provided regression-adjusted estimates for aggregated injury categories (eg, cut/pierce, all intent; Tables 1 and 2), controlling for injury attributes (eg, intent) when sample sizes even in the large databases assessed for this analysis did not permit stratification by detailed injury type.

Limitations

This study did not investigate factors associated with higher injury costs among patients with the same injury type and did not present estimates by geography within the USA. There is some evidence that inpatient CCR may underestimate ED CCR.14 Patients with non-fatal injury were classified by their first chronological injury during the observation period; subsequent injuries during were not classified. This analysis assessed fatal injury medical costs using hospital discharge data, which do not capture non-hospital medical costs among patients who die in nursing homes or non-hospital hospice settings following hospital treatment. Previous injury cost estimates assumed nursing home and hospice location injury deaths each incurred the cost of hospital admission plus an average cost of nursing home care; for example, the nursing home semiprivate room median cost per day ($220 in 2015 US dollars24) multiplied by the median duration of nursing home care before death (5 months25; all diagnoses, not separately available for injury diagnoses), or $33 458 per patient for nursing home location deaths and $11 50626,27 per hospice location death.4 Non-fatal injury costs were assessed over the subsequent 1 year following an index injury ED visit, which underestimates medical costs for injuries resulting in long-term physical disability—for example, traumatic brain injuries and spinal cord injuries—as well as injuries such as violent assault that result in long-term mental health consequences.9,10,28

CONCLUSION

Fatal and non-fatal injuries in the USA are preventable and incur substantial medical costs. Accurate information on the medical cost of injuries is important to monitor the economic burden of injuries and help to prioritise cost-effective public health prevention activities.

Supplementary Material

What is already known on the subject.

Injuries are formally classified into hundreds of types—by mechanism (eg, fall), intent (eg, unintentional), body region (eg, head and neck) and nature of injury (eg, fracture).

Accurate estimates of attributable medical care costs are important to monitor the economic burden of injuries and help to prioritise cost-effective public health prevention activities.

What this study adds.

This study estimated average medical care costs due to fatal and non-fatal injuries in the USA comprehensively by injury type.

Acknowledgments

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement Data sources are publicly available through third parties.

Competing interests None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2017. NCHS Data Brief 2018:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-Based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/nonfatal.html [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Health care satellite account: blended account, 2000–2016 Suidland, MD, 2018. Available: https://www.bea.gov/data/special-topics/health-care [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence B, Miller T. Medical and work loss cost estimation methods for the WISQARS cost of injury module. Calverton, MD: Pacific Institute for Research & Evaluation, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florence C, Haegerich T, Simon T, et al. Estimated Lifetime Medical and Work-Loss Costs of Emergency Department-Treated Nonfatal Injuries--United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1078–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Florence CS, Bergen G, Atherly A, et al. Medical costs of fatal and nonfatal falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:693–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, et al. The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care 2016;54:901–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monuteaux MC, Fleegler EW, Lee LK. A cross-sectional study of emergency care utilization and associated costs of violent-related (assault) injuries in the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;83:S240–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peterson C, DeGue S, Florence C, et al. Lifetime economic burden of rape among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med 2017;52:691–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson C, Kearns MC, McIntosh WL, et al. Lifetime economic burden of intimate partner violence among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:433–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. HCUP NEDS description of data elements: injury. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/vars/injury/nedsnote.jsp [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center for Health Statistics. International classification of diseases, tenth revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM). Altanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10.htm [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson C, Xu L, Florence C, et al. Annual cost of U.S. Hospital visits for pediatric abusive head trauma. Child Maltreat 2015;20:162–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The cost of “treat and release” visits to hospital emergency departments HCUP methods series report # 2007-05. Rockville, MD: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson C, Xu L, Florence C, et al. Professional fee ratios for us hospital discharge data. Med Care 2015;53:840–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rui P, Kang K. Table 5. mode of arrival at emergency department, by patient age: United States, 2015. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2015_ed_web_tables.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 2.5.4: price indexes for personal consumption expenditures by function: 37. health 2018, 2018. Available: http://www.bea.gov/itable/ [Accessed 31 Jul 2018].

- 18.US Government Accountability Office. Ambulance providers: costs and Medicare margins varied widely; transports of beneficiaries have increased (GAO-13-6). Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Law Program. Table 1: selected characteristics of death requiring investigation by state. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/coroner/investigations.html [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 1.1.4. Price indexes for gross domestic product: 1. gross domestic product, 2018. Available: http://www.bea.gov/itable/ [Accessed 28 Nov 2018].

- 21.Hickman M, Hughes K, Strom K, et al. Medical Examiners and Coroners’ Offices, 2004 (NCJ 216756). Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deb P, Norton EC. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Public Health 2018;39:489–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health Care Cost Institute. Health care cost and utilization report 2018. Washington, DC: Health Care Cost Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genworth Life Insurance Company. Genworth 2015 cost of care survey: home care providers, adult day health care facilities, assisted living facilities and nursing homes. Richmond, VA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly A, Conell-Price J, Covinsky K, et al. Length of stay for older adults residing in nursing homes at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1701–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hargraves J, Brennan N. Medicare Hospice Spending Hit $15.8 Billion In 2015, Varied By Locale, Diagnosis. Health Aff 2016;35:1902–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: hospice providers 2015. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Hospice.html [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson C, Florence C, Klevens J. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child Abuse Negl 2018;86:178–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.