Abstract

Neutrophils are produced in the bone marrow and then patrol blood vessels from which they can be rapidly recruited to a site of infection. Neutrophils bind, engulf, and efficiently kill invading microbes via a suite of defense mechanisms. Diverse extracellular and intracellular microbes induce neutrophils to extrude neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) through the process of NETosis. Here, we review the signaling mechanisms and cell biology underpinning the key NETosis pathways during infection and the antimicrobial functions of NETs in host defense.

In 1880, Paul Ehrlich described cells with granules and a lobulated nucleus, and called these cells polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes were then further classified into eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils. Neutrophils are now recognized as essential effector cells of innate immunity and key regulators of both innate and adaptive immune responses. Neutrophils are produced in the bone marrow and then patrol blood vessels, from which they can be rapidly recruited to a site of infection. Neutrophil activation by pathogen products or the local inflammatory milieu prolongs neutrophil life span and arms these cells with antimicrobial effector functions (Dale et al. 2008; Nauseef and Borregaard 2014).

Neutrophils combat microbes using a suite of defense mechanisms. Neutrophils internalize microbes through the process of phagocytosis after which the antimicrobial arsenal of the neutrophil granules is delivered to the phagosome to mediate microbial killing. Neutrophils can also externalize their granule content to neutralize extracellular microbes in a process called degranulation. The key granule proteins involved in microbial killing are α-defensins, lysozymes, and the three neutrophil serine proteases, neutrophil elastase (NE), cathepsin G (CatG), and proteinase-3 (PR-3). Phagocytosis and degranulation also induce the assembly of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase complex. NAPDH oxidase converts oxygen into superoxide, which can be further catalyzed to H2O2, hydroxyl anion, or peroxynitrite anion, to produce an array of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Faurschou and Borregaard 2003; Borregaard 2014).

Although neutrophils have evolved multiple strategies to inactivate and eliminate invading microbes, pathogens have also developed strategies to escape the neutrophil immune defense machinery described above. Neutrophils can, thus, exert an additional antimicrobial defense program when they encounter microbes that are either too large for phagocytosis, or have evaded phagosomal destruction by escaping into the cytosol. Here, neutrophils extrude a physical barrier to pathogen dissemination, called a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) (Amulic et al. 2012; Papayannopoulos 2018). This review summarizes the major pathways that lead to the extrusion of NETs during infection and their functions in host defense.

NEUTROPHIL EXTRACELLULAR TRAPS

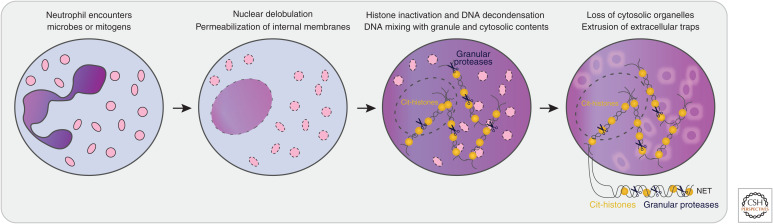

NETs are webs of neutrophil DNA coated with histones and antimicrobial proteins that entrap microbes. Neutrophils cast their NETs in a multistep process called NETosis (Brinkmann et al. 2004; Fuchs et al. 2007; Papayannopoulos et al. 2010). NETosis is a distinct cellular program from apoptosis or necroptosis, and true NET structures are not usually cast during these latter forms of cell death. NETosis involves several distinct and sequential morphological changes in the neutrophil (Fig. 1; Fuchs et al. 2007; Yipp and Kubes 2013): (1) The characteristic lobulated architecture of the nucleus is lost, (2) the nuclear and granular membranes become permeable, (3) histone inactivation leads to chromatin expansion into the cytosol, (4) chromatin mixes with granule content, (5) the loss of internal membranes leads to the disappearance of cytosolic organelles, and (6) the plasma membrane becomes permeable and the NETs are released into the extracellular space.

Figure 1.

NETosis is a distinct cellular program in neutrophils. Neutrophil NETosis involves sequential morphological changes: (1) The characteristic lobulated architecture of the nucleus (purple) is lost, (2) the membranes of the nucleus and granules (pink) become permeable, (3) histone inactivation by clipping and/or citrullination (Cit-histones) leads to chromatin expansion into the cytosol, (4) chromatin mixes with granule content, (5) the loss of internal membranes leads to the disappearance of cytosolic organelles, and (6) the plasma membrane breaks and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are released into the extracellular space.

Within NETs, the DNA is decorated with a conserved set of nuclear, granular, and cytoplasmic proteins. The key antimicrobial effector proteins of NETs are histones (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) and granule proteases (such as NE, CatG, and PR-3), as well as myeloperoxidase (MPO) and lactotransferrin. The proteases remain enzymatically active even when the NET is exposed to endogenous protease inhibitors. Other granule proteins, such as azurocidin, lysozyme C, and α-defensins, are also reported within NETs (Dwyer et al. 2014). NETs also contain cytoplasmic and cytoskeleton proteins such as S100 calcium-binding proteins, actin, myosin, and cytokeratin (Urban et al. 2009; O'Donoghue et al. 2013; Dwyer et al. 2014). Proteomics studies identified 24 proteins within PMA-induced NETs (Urban et al. 2009; O'Donoghue et al. 2013), and 80 proteins within NETs induced by nonmucoid and mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Dwyer et al. 2014). It is, thus, possible that the composition of the NET is influenced by its eliciting stimulus.

THE NEUTROPHIL'S DECISION TO CAST A NET IS INFORMED BY MICROBE SIZE AND LOCATION

When encountering a microbe, the neutrophil needs to determine which antimicrobial defense function to deploy. A microbe size-sensing mechanism allows neutrophils to decide whether or not to launch a NET in response to extracellular pathogens (Branzk et al. 2014). Small microbes that are readily taken up by phagocytosis are poor NET stimulants because the phagosome fuses with neutrophil azurophil granules, and neutrophil granule proteases are, thus, unavailable for initiating NETosis (Branzk et al. 2014). Phagosome formation, hence, serves as a checkpoint to prevent NETosis. Some microbes are too large to be engulfed by phagocytosis, for example, the fungus Candida albicans that forms large filamentous hyphae, or aggregates of Mycobacterium bovis. If a neutrophil encounters these large microbes, the azurophil granule protein NE is released into the cytoplasm to initiate NET formation. Neutrophils deficient in dectin-1, a receptor that mediates phagocytosis of fungi, are hindered in their ability to determine which antimicrobial defense mechanism to apply, resulting in uncontrolled NET release (Branzk et al. 2014). Microbe size and location also affect other neutrophil antimicrobial functions. Neutrophil interaction with large microbes, such as C. albicans hyphae, leads to the extracellular deployment of ROS and strong interleukin (IL)-1β secretion with resultant neutrophil clustering wherein about eight neutrophils engage with one 100-µm hyphal filament. In contrast, small phagocytosed microbes trigger the intracellular deployment of ROS, suppressing cytokine release and neutrophil clustering, and thereby preventing neutrophil accumulation and tissue damage during microbial clearance (Warnatsch et al. 2017).

Microbe size may not be the only factor that determines the antimicrobial response of neutrophils. Some microbes can manipulate the neutrophil response by evading phagocytosis, and may thereby induce NET formation (Sumby et al. 2005; Döhrmann et al. 2014; Eby et al. 2014; Storisteanu et al. 2017; Eisenbeis et al. 2018). For example, Gram-negative bacteria that escape the phagosome to translocate to the cytosol induce NETs in a newly described pathway that involves the noncanonical inflammasome machinery (Chen et al. 2018).

In the 15 years since their discovery, NETs have been an area of intense research, which has provided important insights into this novel antimicrobial mechanism, and revealed several distinct pathways for trap release. In this review, we describe three key mechanisms by which neutrophils extrude NETs in host defense through the process of suicidal NETosis, noncanonical NETosis, and vital NETosis. Whereas all of these NETosis pathways ultimately lead to neutrophil death, NET extrusion occurs during cell rupture in suicidal and noncanonical NETosis while NETs are expelled from neutrophils that can continue to perform cell functions (e.g., migration) in vital NETosis.

SUICIDAL NETosis

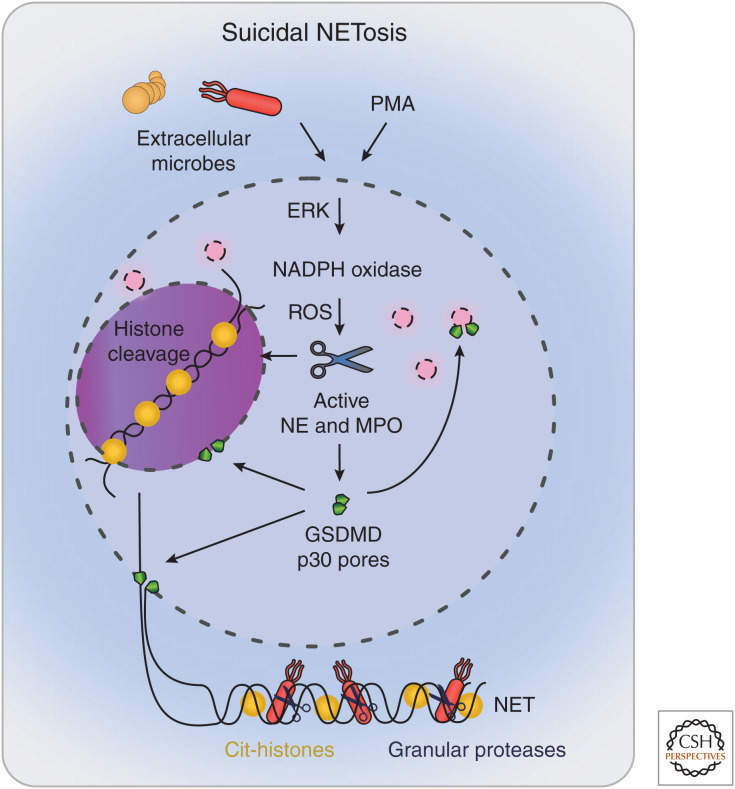

The first NETosis pathway was described in 2004, in which NET extrusion and cell death (suicidal NETosis) was observed in response to high doses of phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) (Brinkmann et al. 2004). The strong and robust NET responses induced by PMA have led to the adoption of PMA as a key in vitro stimulant for the study of NETosis. PMA is a potent activator of several signaling pathways within neutrophils such as protein kinase C (PKC) (Steinberg 2008). PMA mediates suicidal NETosis by inducing the assembly of NADPH oxidase, which triggers ROS production, MPO activation, and the cytoplasmic release of NE, and leads to chromatin decondensation in the nucleus (Fig. 2). Following this, the nuclear membrane breaks down, resulting in the release of the decondensed chromatin into the cytosol. Chromatin is then expelled into the extracellular space via GSDMD pores or GSDMD-driven membrane tears, and results in neutrophil death (Brinkmann et al. 2004; Fuchs et al. 2007; Sollberger et al. 2018). Below, we will focus on this well-characterized pathway of NE-, MPO-, and ROS-driven NETosis as an exemplar for suicidal NETosis. However, ionophores (e.g., A23187, nigericin) also trigger suicidal NETosis through a poorly characterized mechanism that is independent of NE, MPO, and ROS (Neeli and Radic 2013; Kenny et al. 2017), highlighting the complexity of NETosis pathways.

Figure 2.

Suicidal NETosis. Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) or extracellular microbes induce suicidal NETosis by inducing the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-dependent assembly of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the cytoplasmic release of granule proteins, and leads to chromatin decondensation in the nucleus. Chromatin is then expelled into the extracellular space via gasdermin D (GSDMD) pores or GSDMD-driven membrane tears, resulting in neutrophil death. (NE) neutrophil elastase, (MPO) myeloperoxidase, (NET) neutrophil extracellular trap.

NADPH Oxidase

On activation by PMA, neutrophils up-regulate glycolysis (Rodríguez-Espinosa et al. 2015), and this is required for NET expulsion (Rodríguez-Espinosa et al. 2015; Siler et al. 2017). Glucose uptake induces signaling by extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (Rodríguez-Espinosa et al. 2015), leading to the phosphorylation of one of the three cytoplasmic regulatory subunits of the NADPH oxidase, p47phox (El Benna et al. 1996; Hakkim et al. 2011). On phosphorylation, p47phox is recruited to the granule and plasma membranes, in which it interacts with other subunits to assemble the NADPH oxidase complex and generate superoxide (Dang et al. 1999; Lopes et al. 1999; Kleniewska et al. 2012; Nunes et al. 2013; Dinauer 2016). Inhibitors of the ERK pathway, thus, block NADPH oxidase function and PMA-induced NET release (Hakkim et al. 2011). PMA- and microbe-induced NET release is also suppressed in neutrophils deficient in Rac2, a small GTPase required for NADPH oxidase function (Lim et al. 2011; Gavillet et al. 2018), and in neutrophils from chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) patients that are deficient in NADPH oxidase function (Bianchi et al. 2009; Röhm et al. 2014). Gene therapy restored NADPH oxidase function in a CGD patient, and consequently reinstated the capacity of their neutrophils to produce NETs, which were able to inhibit Aspergillus nidulans growth (Bianchi et al. 2009). As invasive aspergillosis is a leading cause of death in CGD patients, this suggests that ROS-dependent NETs may be critical for host defense against Aspergilli species.

Granule Proteases

Under resting conditions, the neutrophil's antimicrobial arsenal is stored in granules. ROS generation by NAPDH oxidase triggers the release of these proteins into the cytosol. The protease NE is particularly critical for suicidal NETosis, as murine NE deficiency prevents NET formation during in vivo challenge with Klebsiella pneumoniae (Papayannopoulos et al. 2010).

The exact mechanism by which NE is released into the cytosol to initiate NETosis is unclear, but it is proposed to occur without granule rupture (Metzler et al. 2014) and involve cooperation between granule proteins (O'Donoghue et al. 2013). In resting neutrophils, NE clusters together with MPO, azurocidin, CatG, defensin-1, lysozyme, and lactoferrin to form a complex called an “azurosome” in the azurophil granule (Brinkmann et al. 2004; Fuchs et al. 2007; Papayannopoulos et al. 2010; Metzler et al. 2011). On neutrophil NADPH oxidase activation, ROS triggers MPO activation and the dissociation of MPO and NE from the azurosome (Metzler et al. 2011, 2014). This induces the release of NE into the cytosol through an unclear mechanism that requires MPO activity within the cell (Metzler et al. 2014). Human mutations in the MPO locus can decrease or ablate MPO function (Nauseef et al. 1996; Dinauer 2014). Whereas neutrophils from patients with a partial MPO deficiency can still form NETs on exposure to C. albicans, those from MPO-deficient patients cannot (Metzler et al. 2011).

In the cytoplasm, NE binds to the actin cytoskeleton where it degrades F-actin, leading to actin disassembly and neutrophil immobilization (Metzler et al. 2014). In the nucleus, NE cleaves and inactivates histones such as H4 and H2B, leading to chromatin relaxation and DNA decondensation (Papayannopoulos et al. 2010). MPO functions synergistically with NE to mediate chromatin decondensation during NETosis (Papayannopoulos et al. 2010). The exact requirement for MPO in this process is unclear, but may simply involve NE liberation from granules as described above.

PAD4-Dependent Histone Citrullination

Suicidal NETosis is often accompanied by histone citrullination by peptidylarginine deiminase type 4 (PAD4), which can contribute to chromatin relaxation. PAD4 is activated by a cytosolic spike in calcium as is induced by ionophores (Neeli et al. 2008) but not by PMA (Neeli and Radic 2013; Damgaard et al. 2016). Whereas PAD4-dependent histone citrullination often accompanies suicidal NETosis, it is often dispensable for NET extrusion via this pathway (Claushuis et al. 2018; Guiducci et al. 2018), perhaps because histones are additionally inactivated by NE-dependent cleavage, providing redundancy. PAD4 is, however, crucial for chromatin decondensation during vital NETosis.

Gasdermin D: A NETosis Executioner

Gasdermin D (GSDMD) was recently identified as an executioner of suicidal and noncanonical NETosis (Chen et al. 2018; Sollberger et al. 2018). GSDMD usually resides in the cytosol of resting cells. On cleavage by specific proteases, a pore-forming fragment (GSDMD-p30) is generated. During PMA-induced suicidal NETosis, NE cleaves GSDMD to generate GSDMD-p30 pores in the plasma and granule membranes, leading to rupture of these membranes during NETosis (Sollberger et al. 2018). GSDMD pores permeabilize the nuclear membrane during noncanonical NETosis (Chen et al. 2018) and may similarly contribute to nuclear permeabilization during suicidal NETosis. A GSDMD inhibitor blocked PMA-induced NETosis without affecting the function of NADPH oxidase, NE or MPO, highlighting the requirement for membrane permeabilization in this pathway (Sollberger et al. 2018).

Model for Suicidal NETosis

The above studies together suggest the following model for suicidal NETosis (Fig. 2). On neutrophil activation, ROS triggers the activation of MPO and azurosome dissociation within azurophil granules, thereby facilitating the MPO-driven release of NE into the cytoplasm. This small amount of NE appears to be sufficient to cleave GSDMD to GSDMD-p30. This, in turn, induces the formation of GSDMD pores within the granule membrane, leading to granule rupture, further NE release into the cytoplasm, and further GSDMD cleavage in a feedforward loop. NE then translocates into the nucleus, where it cleaves and inactivates histones, leading to chromatin expansion and mixing with cytoplasmic and granule contents. GSDMD-p30 pores then induce plasma membrane rupture to enable NET release (Sollberger et al. 2018).

NONCANONICAL NETosis

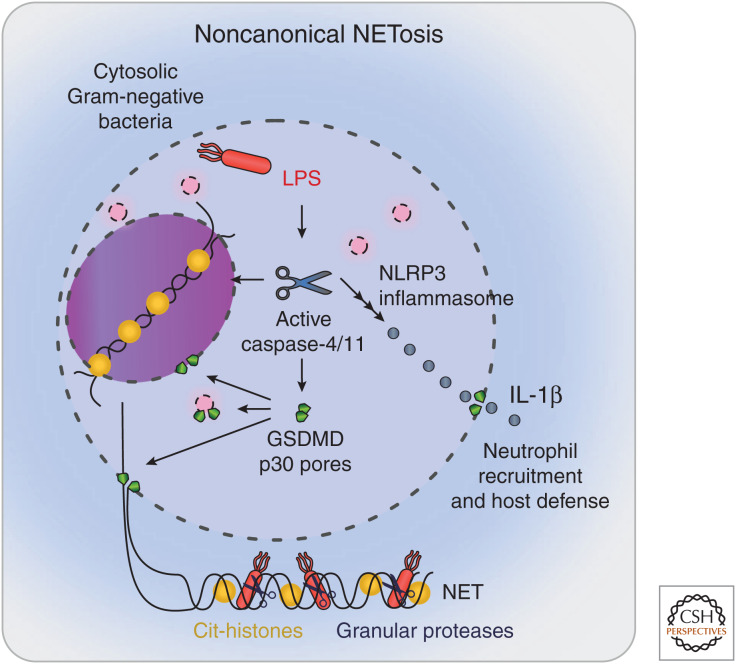

We recently described a new pathway of suicidal NETosis, which we here propose to term noncanonical NETosis, which is deployed when neutrophils detect Gram-negative bacteria in their cytosol. This pathway relies on bacterial sensing by the noncanonical inflammasome (Fig. 3), leading to caspase-4/11- and GSDMD-driven NET extrusion (Chen et al. 2018) through a signaling pathway that resembles cell lysis by pyroptosis but results in the morphological features of neutrophil death by NETosis.

Figure 3.

Noncanonical NETosis. The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of cytosolic Gram-negative bacteria triggers the assembly of the noncanonical inflammasome, leading to caspase-4/11 activation and gasdermin D (GSDMD) cleavage to p30. GSDMD-p30 pores rupture the nuclear and granule membranes and, eventually, the plasma membrane. Caspase-11 gains access to the nucleus, where it cleaves histones to mediate DNA decondensation. Chromatin is then expelled into the extracellular space during plasma membrane rupture, resulting in neutrophil death. During NETosis, GSDMD-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation triggers the release of interleukin (IL)-1β to induce neutrophil recruitment, activation, and killing of the neutrophil extracellular trap (NET)-entrapped bacterium.

Signaling by the Noncanonical Inflammasome

The prefix “noncanonical” in this NETosis pathway indicates the involvement of the noncanonical inflammasome. Inflammasomes can be broadly categorized into those that activate caspase-1 (“canonical inflammasomes”) and those that activate caspase-11 in mouse or caspase-4/5 in humans (“noncanonical inflammasomes”). The noncanonical inflammasomes are sensors for cytosolic Gram-negative bacteria. On detection of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), these inflammasomes assemble to activate caspase-4/5 in humans and caspase-11 in mice. Signaling by both canonical and noncanonical inflammasomes leads to caspase-1- or caspase-4/5/11-dependent cleavage of GSDMD to trigger GSDMD-p30 plasma membrane pores, the release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β and IL-18), and cell lysis by pyroptosis (Kayagaki et al. 2015; Shi et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2016). Pyroptosis has been intensely studied in macrophages but is less characterized in other cell types.

NET Extrusion via the Noncanonical Inflammasome

Compared to macrophages, neutrophils signal via specialized inflammasome pathways that induce distinct outcomes for cell death or viability. We, and others, previously showed that neutrophils do not undergo caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis during canonical inflammasome signaling (Chen et al. 2014, 2018; Karmakar et al. 2015; Monteleone et al. 2018). Neutrophils do, however, die on activation of the noncanonical inflammasome pathway (Chen et al. 2018). Human and murine neutrophils infected with Gram-negative bacteria that access the cytosol (ΔsifA Salmonella enterica, Citrobacter rodentium) died and extruded NETs through a cell death pathway displaying the hallmark features of NETosis, including nuclear delobulation, DNA extrusion, DNA-MPO colocalization, and histone citrullination (Chen et al. 2018). Neutrophil NET extrusion required the pyroptotic machinery, caspase-4/11, and GSDMD, but proceeded independently of NE or MPO. PAD4-dependent histone citrullination accompanied noncanonical NETosis but was not required for death or NET extrusion. Mechanistically, GSDMD-p30 pores target several neutrophil membranes to mediate permeabilization of the granule and nuclear membranes and, eventually, rupture of the plasma membrane (Chen et al. 2018; Sollberger et al. 2018). GSDMD-p30 nuclear pores appear to enable caspase-11 to access the chromatin, in which caspase-11 performs an analogous function to NE to degrade histones and thereby relax chromatin (Chen et al. 2018).

Noncanonical NETosis suppresses bacterial residence in the neutrophil cytosol and prevents in vivo microbial dissemination. During in vitro infection, the noncanonical NETosis pathway suppressed neutrophil cytosolic infection with ΔsifA Salmonella (Chen et al. 2018), presumably by inducing the death of the infected neutrophil. Murine deficiency in Casp11 or Gsdmd promoted microbial dissemination to a secondary infection site during murine in vivo challenge with ΔsifA Salmonella (Chen et al. 2018), confirming previous reports that the noncanonical inflammasome pathway mediates host defense (Aachoui et al. 2013; Storek and Monack 2015; Thurston et al. 2016). Interestingly, when NETs were dismantled at a primary infection site by applying DNase I, this promoted bacterial dissemination in wild-type (WT) but not Casp11–/– or Gsdmd–/– mice (Chen et al. 2018). The NETs themselves thus mediate host defense, likely via immobilizing bacteria to enable their destruction by newly recruited neutrophils.

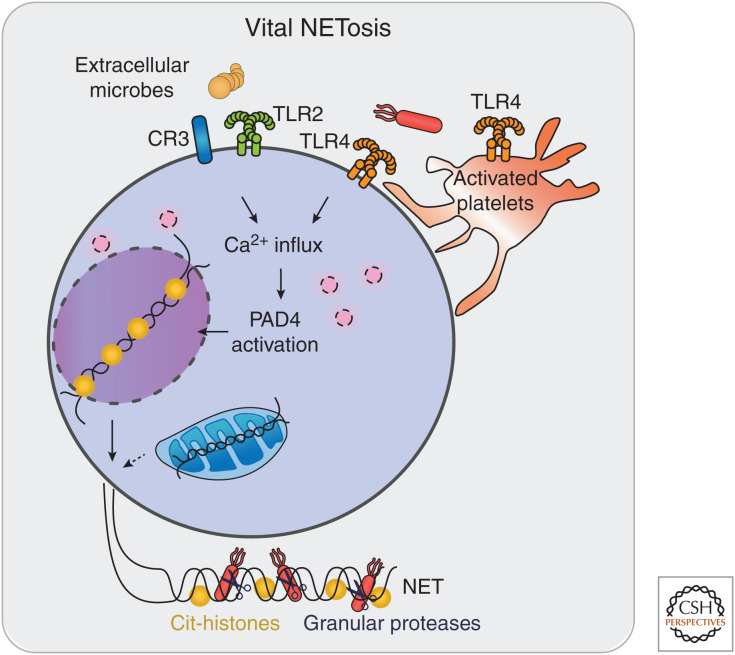

VITAL NETosis

In contrast to the above, relatively slow, pathway of suicidal NETosis, vital NETosis involves the rapid release of NETs on neutrophil stimulation with specific bacteria, bacterial products, Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4-activated platelets or complement proteins (Fig. 4). Vital NETosis, also called “leukotoxic hypercitrullination” (Konig and Andrade 2016), mimics features of suicidal NETosis but does not immediately induce neutrophil death. During vital NETosis, neutrophils are still capable of functions such as migration, phagocytosis, and killing of bacteria while releasing their NET (Clark et al. 2007; Pilsczek et al. 2010; Yipp et al. 2012). The key features of vital NETosis are rapid histone citrullination, nuclear blebbing, and the vesicular transport of nuclear blebs to the plasma membrane, in which chromatin is externalized without permeabilizing the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

Vital NETosis. Microbial products or activated platelets stimulate vital NETosis through cell-surface receptors (e.g., TLR2, TLR4, complement receptor-3 [CR3]). The resulting spike in cytosolic calcium activates neutrophil PAD4, triggering histone citrullination and DNA decondensation. Chromatin derived from nuclear blebs or the mitochondria is expelled to generate a neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) while the neutrophil is still able to perform cellular functions such as cell migration.

Vital NETosis is often observed during thrombosis and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and autoimmune vasculitis (Clark et al. 2007; Kessenbrock et al. 2009; Fuchs et al. 2010; Pilsczek et al. 2010; Yipp et al. 2012; Martinod et al. 2016). Here, we will focus on neutrophil vital NETosis during interaction with microbes, and summarize the key unique features of vital NETosis that are not observed in suicidal or noncanonical NETosis.

Receptor-Mediated Rapid Vital NETosis

Several surface receptors appear to be required for vital NETosis. TLR2 was required for vital NETosis during murine in vivo skin infection with Staphylococcus aureus (Yipp et al. 2012), and TLR2 or TLR4 receptor blockade suppressed NET formation induced by in vitro exposure to S. aureus (Wan et al. 2017). Neutrophil exposure to bacterial LPS in whole blood triggers vital NETosis. Here, NET extrusion requires TLR4 expression on platelets and platelet–neutrophil interaction via P-selectin (Pieterse et al. 2016). The complement system is also implicated in vital NETosis. When immobilized by the extracellular matrix component fibronectin, the β-glucan of C. albicans is recognized by complement receptor 3, inducing robust NET formation (Byrd et al. 2013). These findings highlight the complexity of host–pathogen interaction during a coordinated immune response.

PAD4 Functions in Vital NETosis

Calcium signaling, PAD4 activation, and histone citrullination appear to be common requirements for vital NETosis. Whereas most stimulators of suicidal NETosis require NADPH oxidase function and induce NE-dependent histone clipping, NADPH oxidase function is dispensable for vital NETosis (Pilsczek et al. 2010; Douda et al. 2015), which proceeds without apparent histone clipping (Pieterse et al. 2018). Ionophores, bacterial products, or an increase in extracellular pH trigger the generation of mitochondrial ROS, calcium influx, and calcium-activated PAD4 enzymatic function in neutrophils (Douda et al. 2015; Naffah de Souza et al. 2017). PAD4 can then citrullinate histones to mediate DNA decondensation. PAD4 deficiency in Shigella flexneri–infected neutrophils rendered these cells unable to citrullinate histones, undergo vital NETosis, or mediate bacterial killing (Li et al. 2010). In line with an essential function for PAD4 in this pathway, a selective PAD4 inhibitor abrogated vital NETosis induced by ionomycin or S. aureus (Lewis et al. 2015).

DNA Source during Vital NETosis

Whereas suicidal NETosis clearly involves the expulsion of nuclear DNA, the source of extruded DNA during vital NETosis is less clear. A number of studies report nuclear blebbing leading to the release of histone-rich nuclear DNA (Pilsczek et al. 2010; Yipp et al. 2012; Gupta et al. 2018). Other studies suggest that NETs contain mitochondrial DNA (Yousefi et al. 2009; Keshari et al. 2012; Itagaki et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2015; Lood et al. 2016). Several studies indicate that NETs containing mitochondrial DNA elicit proinflammatory cytokine production from immune cells (Keshari et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2015; Lood et al. 2016).

MICROBIAL TRIGGERS OF NETosis

A wide variety of microbes are reported to induce NETosis. NET-inducing bacteria include S. flexneri (Brinkmann et al. 2004), Escherichia coli (Grinberg et al. 2008), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Beiter et al. 2006), Streptococcus pyogenes (Sumby et al. 2005), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Ramos-Kichik et al. 2009). Fungi such as C. albicans (Urban et al. 2006, 2009) and Aspergillus fumigatus (Bruns et al. 2010) are well characterized to induce NETosis. Even parasites are reported to induce NETosis, including Leishmania spp. (Guimaraes-Costa et al. 2009), Plasmodium falciparum (Baker et al. 2008), and Toxoplasma gondii (Abi Abdallah and Denkers 2012; Abi Abdallah et al. 2012). NET extrusion thus appears to be a conserved immune defense strategy in response to many different microbes.

FUNCTIONS FOR NETS IN ANTIMICROBIAL DEFENSE

Most NET studies agree that these structures trap extracellular microbes such as C. albicans or T. gondii (Urban et al. 2006, 2009). Imaging techniques that use flow chamber systems or intravital microscopy elegantly showed E. coli capture by NETs in vitro and in vivo (Clark et al. 2007). For example, confocal intravital microscopy imaged NETs capturing circulating E. coli in the hepatic sinusoids (McDonald et al. 2012).

There is growing evidence that NETs can also directly kill some pathogens such as E. coli (Grinberg et al. 2008) or Leishamania spp. (Guimaraes-Costa et al. 2009). The direct antimicrobial properties of NETs remain a topic of debate, and it is possible that NETs exert variable efficiency for killing different microbial species. NETs contain a selection of proteins with known antimicrobial properties such as histones (Hirsch 1958), and granule-resident antimicrobial proteins such as NE and MPO. NE kills bacteria by cleaving proteins on the bacterial outer membrane and targeting virulence factors of colonic enterobacteria, such as Shigella or Yersinia (Belaaouaj et al. 1998, 2000; Weinrauch et al. 2002), and is crucial in host defense against Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli or K. pneumoniae (Belaaouaj et al. 1998). MPO remains active upon the extruded NET, where it generates ROS, such as hypochlorous acid from H2O2 derived from NAPDH oxidase or the bacterium itself, to mediate bacteria killing (Allen and Stephens 2011; Parker et al. 2012a,b).

GSDMD pores may be a key antimicrobial weapon generated during noncanonical and suicidal NETosis (Chen et al. 2018; Sollberger et al. 2018). Both forms of NETosis trigger the cleavage of GSDMD to its pore-forming p30 fragment, which is poorly soluble, and immediately associates with lipids such as cardiolipin, phosphatidylinositol phosphates, and phosphatidylserine (Ding et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2016; Sborgi et al. 2016). GSDMD-p30 is reported to target bacterial membranes to induce the killing of extracellular E. coli and S. aureus (Ding et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2016) and cytosolic L. monocytogenes (Liu et al. 2016). GSDMD-p30 pores in the host cell plasma membrane are also crucial for its antimicrobial functions. Here, GSDMD-p30 pores facilitate plasma membrane rupture to enable NET release, and also the secretion of IL-1β to recruit neutrophils to a site of infection (Monteleone et al. 2018). At an infection site, IL-1β and other factors activate neutrophils and extend their life span to ensure they are able to mediate host-defensive functions (Miller et al. 2007; Rider et al. 2011; Biondo et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2014). Thus, GSDMD may serve several functions in the host defense, in which GSDMD-driven NETs first immobilize the pathogen, GSDMD pores directly target the bacterial membrane, and GSDMD-dependent IL-1β serves as a call-to-arms to recruit circulating neutrophils to kill the entrapped microbe.

MICROBIAL EVASION OF NETs

The effectiveness of NETs in mediating host defense is highlighted by the observation that many microbes have developed NET-evasion mechanisms. Some microbes suppress NETs by blocking the upstream signaling pathways, whereas others encode DNases to degrade the NET or have developed resistance to antimicrobial proteins upon the NET (Sumby et al. 2005; Döhrmann et al. 2014; Eby et al. 2014; Storisteanu et al. 2017; Eisenbeis et al. 2018). For example, Bordetella pertussis encodes an adenylate cyclase toxin (ACT) to produce intracellular cAMP to suppress the neutrophil ERK-dependent oxidative burst and, hence, NETosis (Eby et al. 2014). Group A Streptococcus has developed several strategies to evade NET-dependent host defense, including the expression of nucleases to degrade NETs (Sumby et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2007), and suppressing MPO release via the M1T1 serotype streptococcal collagen-like protein 1 (Scl-1) (Döhrmann et al. 2014). The Staphylococcal protein A (SpA) is a virulence factor that is secreted into the extrabacterial space to suppress neutrophil phagocytosis of S. aureus, but in doing so, promotes NETosis (Hoppenbrouwers et al. 2018). Other S. aureus virulence factors, such as the DNA-binding protein extracellular adherence protein (Eap), suppress NET formation and function (Eisenbeis et al. 2018). Such microbial evasion strategies highlight the requirement for neutrophils to have a multitude of microbial killing mechanisms at their disposal for many and varied host defense strategies.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Diverse extracellular and intracellular microbes induce neutrophils to trigger NETs by suicidal, noncanonical, and vital NETosis. By entrapping microbes, NETs prevent microbial dissemination to a secondary infection site and, in some cases, NETs exert direct antimicrobial functions. In addition to these antimicrobial functions, emerging literature documents pathological roles for NETs in autoimmune diseases. It remains to be elucidated whether distinct NETosis pathways engender differences in immunomodulatory or antimicrobial properties of the resulting NET. The recent discovery that the suicidal and noncanonical NETosis pathways converge on a single cell death executioner protein, GSDMD, suggests that GSDMD inhibitors may have therapeutic potential in the treatment of NET-associated diseases such as thrombosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and autoimmune vasculitis. Further research to elucidate the molecular and cellular mechanisms by which neutrophils cast their NETs will be critical for understanding this important host defense program and the design of new autoimmune disease therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Madhavi Maddugoda for editorial suggestions. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Project Grant 1163924 and Fellowship 1141131 to K.S.). K.S. is a coinventor on patent applications for NLRP3 inhibitors that have been licensed to Inflazome, a company headquartered in Dublin, Ireland. Inflazome is developing drugs that target the NLRP3 inflammasome to address unmet clinical needs in inflammatory disease. K.S. served on the Scientific Advisory Board of Inflazome in 2016–2017. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Editors: Kim Newton, James M. Murphy, and Edward A. Miao

Additional Perspectives on Cell Survival and Cell Death available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Aachoui Y, Leaf IA, Hagar JA, Fontana MF, Campos CG, Zak DE, Tan MH, Cotter PA, Vance RE, Aderem A, et al. 2013. Caspase-11 protects against bacteria that escape the vacuole. Science 339: 975–978. 10.1126/science.1230751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abi Abdallah DS, Denkers EY. 2012. Neutrophils cast extracellular traps in response to protozoan parasites. Front Immunol 3: 382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abi Abdallah DS, Lin C, Ball CJ, King MR, Duhamel GE, Denkers EY. 2012. Toxoplasma gondii triggers release of human and mouse neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect Immun 80: 768–777. 10.1128/IAI.05730-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RC, Stephens JT Jr. 2011. Myeloperoxidase selectively binds and selectively kills microbes. Infect Immun 79: 474–485. 10.1128/IAI.00910-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes GL, Metzler KD, Zychlinsky A. 2012. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu Rev Immunol 30: 459–489. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker VS, Imade GE, Molta NB, Tawde P, Pam SD, Obadofin MO, Sagay SA, Egah DZ, Iya D, Afolabi BB, et al. 2008. Cytokine-associated neutrophil extracellular traps and antinuclear antibodies in Plasmodium falciparum infected children under six years of age. Malar J 7: 41 10.1186/1475-2875-7-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiter K, Wartha F, Albiger B, Normark S, Zychlinsky A, Henriques-Normark B. 2006. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol 16: 401–407. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaaouaj A, McCarthy R, Baumann M, Gao Z, Ley TJ, Abraham SN, Shapiro SD. 1998. Mice lacking neutrophil elastase reveal impaired host defense against gram negative bacterial sepsis. Nat Med 4: 615–618. 10.1038/nm0598-615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaaouaj A, Kim KS, Shapiro SD. 2000. Degradation of outer membrane protein A in Escherichia coli killing by neutrophil elastase. Science 289: 1185–1187. 10.1126/science.289.5482.1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi M, Hakkim A, Brinkmann V, Siler U, Seger RA, Zychlinsky A, Reichenbach J. 2009. Restoration of NET formation by gene therapy in CGD controls aspergillosis. Blood 114: 2619–2622. 10.1182/blood-2009-05-221606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondo C, Mancuso G, Midiri A, Signorino G, Domina M, Lanza Cariccio V, Mohammadi N, Venza M, Venza I, Teti G, et al. 2014. The interleukin-1β/CXCL1/2/neutrophil axis mediates host protection against group B streptococcal infection. Infect Immun 82: 4508–4517. 10.1128/IAI.02104-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borregaard N. 2014. What doesn't kill you makes you stronger: the anti-inflammatory effect of neutrophil respiratory burst. Immunity 40: 1–2. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzk N, Lubojemska A, Hardison SE, Wang Q, Gutierrez MG, Brown GD, Papayannopoulos V. 2014. Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nat Immunol 15: 1017–1025. 10.1038/ni.2987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, Zychlinsky A. 2004. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303: 1532–1535. 10.1126/science.1092385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns S, Kniemeyer O, Hasenberg M, Aimanianda V, Nietzsche S, Thywißen A, Jeron A, Latgé JP, Brakhage AA, Gunzer M. 2010. Production of extracellular traps against Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro and in infected lung tissue is dependent on invading neutrophils and influenced by hydrophobin RodA. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000873 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd AS, O'Brien XM, Johnson CM, Lavigne LM, Reichner JS. 2013. An extracellular matrix–based mechanism of rapid neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Candida albicans. J Immunol 190: 4136–4148. 10.4049/jimmunol.1202671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Groß CJ, Sotomayor FV, Stacey KJ, Tschopp J, Sweet MJ, Schroder K. 2014. The neutrophil NLRC4 inflammasome selectively promotes IL-1β maturation without pyroptosis during acute Salmonella challenge. Cell Rep 8: 570–582. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Monteleone M, Boucher D, Sollberger G, Ramnath D, Condon ND, von Pein JB, Broz P, Sweet MJ, Schroder K. 2018. Noncanonical inflammasome signaling elicits gasdermin D-dependent neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci Immunol 3: eaar6676 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar6676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, Patel KD, Chakrabarti S, McAvoy E, Sinclair GD, et al. 2007. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med 13: 463–469. 10.1038/nm1565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claushuis TAM, van der Donk LEH, Luitse AL, van Veen HA, van der Wel NN, van Vught LA, Roelofs J, de Boer OJ, Lankelma JM, Boon L, et al. 2018. Role of peptidylarginine deiminase 4 in neutrophil extracellular trap formation and host defense during Klebsiella pneumoniae–induced pneumonia-derived sepsis. J Immunol 201: 1241–1252. 10.4049/jimmunol.1800314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale DC, Boxer L, Liles WC. 2008. The phagocytes: neutrophils and monocytes. Blood 112: 935–945. 10.1182/blood-2007-12-077917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard D, Bjørn ME, Steffensen MA, Pruijn GJ, Nielsen CH. 2016. Reduced glutathione as a physiological co-activator in the activation of peptidylarginine deiminase. Arthritis Res Ther 18: 102 10.1186/s13075-016-1000-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang PM, Babior BM, Smith RM. 1999. NADPH dehydrogenase activity of p67PHOX, a cytosolic subunit of the leukocyte NADPH oxidase. Biochemistry 38: 5746–5753. 10.1021/bi982750f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinauer MC. 2014. Disorders of neutrophil function: an overview. Methods Mol Biol 1124: 501–515. 10.1007/978-1-62703-845-4_30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinauer MC. 2016. Primary immune deficiencies with defects in neutrophil function. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2016: 43–50. 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Wang K, Liu W, She Y, Sun Q, Shi J, Sun H, Wang DC, Shao F. 2016. Pore-forming activity and structural autoinhibition of the gasdermin family. Nature 535: 111–116. 10.1038/nature18590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döhrmann S, Anik S, Olson J, Anderson EL, Etesami N, No H, Snipper J, Nizet V, Okumura CY. 2014. Role for streptococcal collagen-like protein 1 in M1T1 group A Streptococcus resistance to neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect Immun 82: 4011–4020. 10.1128/IAI.01921-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douda DN, Khan MA, Grasemann H, Palaniyar N. 2015. SK3 channel and mitochondrial ROS mediate NADPH oxidase-independent NETosis induced by calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: 2817–2822. 10.1073/pnas.1414055112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer M, Shan Q, D'Ortona S, Maurer R, Mitchell R, Olesen H, Thiel S, Huebner J, Gadjeva M. 2014. Cystic fibrosis sputum DNA has NETosis characteristics and neutrophil extracellular trap release is regulated by macrophage migration-inhibitory factor. J Innate Immun 6: 765–779. 10.1159/000363242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby JC, Gray MC, Hewlett EL. 2014. Cyclic AMP-mediated suppression of neutrophil extracellular trap formation and apoptosis by the Bordetella pertussis adenylate cyclase toxin. Infect Immun 82: 5256–5269. 10.1128/IAI.02487-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbeis J, Saffarzadeh M, Peisker H, Jung P, Thewes N, Preissner KT, Herrmann M, Molle V, Geisbrecht BV, Jacobs K, et al. 2018. The Staphylococcus aureus extracellular adherence protein Eap is a DNA binding protein capable of blocking neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8: 235 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Benna J, Han J, Park JW, Schmid E, Ulevitch RJ, Babior BM. 1996. Activation of p38 in stimulated human neutrophils: phosphorylation of the oxidase component p47phox by p38 and ERK but not by JNK. Arch Biochem Biophys 334: 395–400. 10.1006/abbi.1996.0470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faurschou M, Borregaard N. 2003. Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect 5: 1317–1327. 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, Weinrauch Y, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. 2007. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 176: 231–241. 10.1083/jcb.200606027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, Schatzberg D, Monestier M, Myers DD Jr, Wrobleski SK, Wakefield TW, Hartwig JH, Wagner DD. 2010. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 15880–15885. 10.1073/pnas.1005743107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavillet M, Martinod K, Renella R, Wagner DD, Williams DA. 2018. A key role for Rac and Pak signaling in neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) formation defines a new potential therapeutic target. Am J Hematol 93: 269–276. 10.1002/ajh.24970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg N, Elazar S, Rosenshine I, Shpigel NY. 2008. β-Hydroxybutyrate abrogates formation of bovine neutrophil extracellular traps and bactericidal activity against mammary pathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 76: 2802–2807. 10.1128/IAI.00051-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiducci E, Lemberg C, Küng N, Schraner E, Theocharides APA, LeibundGut-Landmann S. 2018. Candida albicans–induced NETosis is independent of peptidylarginine deiminase 4. Front Immunol 9: 1573 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes-Costa AB, Nascimento MT, Froment GS, Soares RP, Morgado FN, Conceicao-Silva F, Saraiva EM. 2009. Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes induce and are killed by neutrophil extracellular traps. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 6748–6753. 10.1073/pnas.0900226106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Chan DW, Zaal KJ, Kaplan MJ. 2018. A high-throughput real-time imaging technique to quantify NETosis and distinguish mechanisms of cell death in human neutrophils. J Immunol 200: 869–879. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakkim A, Fuchs TA, Martinez NE, Hess S, Prinz H, Zychlinsky A, Waldmann H. 2011. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol 7: 75–77. 10.1038/nchembio.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JG. 1958. Bactericidal action of histone. J Exp Med 108: 925–944. 10.1084/jem.108.6.925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppenbrouwers T, Sultan AR, Abraham TE, Lemmens-den Toom NA, Hansenová Maňásková S, van Cappellen WA, Houtsmuller AB, van Wamel WJB, de Maat MPM, van Neck JW. 2018. Staphylococcal protein A is a key factor in neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Front Immunol 9: 165 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itagaki K, Kaczmarek E, Lee YT, Tang IT, Isal B, Adibnia Y, Sandler N, Grimm MJ, Segal BH, Otterbein LE, et al. 2015. Mitochondrial DNA released by trauma induces neutrophil extracellular traps. PLoS ONE 10: e0120549 10.1371/journal.pone.0120549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar M, Katsnelson M, Malak HA, Greene NG, Howell SJ, Hise AG, Camilli A, Kadioglu A, Dubyak GR, Pearlman E. 2015. Neutrophil IL-1β processing induced by pneumolysin is mediated by the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome and caspase-1 activation and is dependent on K+ efflux. J Immunol 194: 1763–1775. 10.4049/jimmunol.1401624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O'Rourke K, Anderson K, Warming S, Cuellar T, Haley B, Roose-Girma M, Phung QT, et al. 2015. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 526: 666–671. 10.1038/nature15541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny EF, Herzig A, Krüger R, Muth A, Mondal S, Thompson PR, Brinkmann V, Bernuth HV, Zychlinsky A. 2017. Diverse stimuli engage different neutrophil extracellular trap pathways. eLife 6: 24437 10.7554/eLife.24437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshari RS, Jyoti A, Kumar S, Dubey M, Verma A, Srinag BS, Krishnamurthy H, Barthwal MK, Dikshit M. 2012. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain mitochondrial as well as nuclear DNA and exhibit inflammatory potential. Cytometry A 81A: 238–247. 10.1002/cyto.a.21178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schönermarck U, Back W, Gross WL, Werb Z, Gröne HJ, Brinkmann V, Jenne DE. 2009. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med 15: 623–625. 10.1038/nm.1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleniewska P, Piechota A, Skibska B, Gorąca A. 2012. The NADPH oxidase family and its inhibitors. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 60: 277–294. 10.1007/s00005-012-0176-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig MF, Andrade F. 2016. A critical reappraisal of neutrophil extracellular traps and NETosis mimics based on differential requirements for protein citrullination. Front Immunol 7: 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HD, Liddle J, Coote JE, Atkinson SJ, Barker MD, Bax BD, Bicker KL, Bingham RP, Campbell M, Chen YH, et al. 2015. Inhibition of PAD4 activity is sufficient to disrupt mouse and human NET formation. Nat Chem Biol 11: 189–191. 10.1038/nchembio.1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. 2010. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med 207: 1853–1862. 10.1084/jem.20100239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MB, Kuiper JW, Katchky A, Goldberg H, Glogauer M. 2011. Rac2 is required for the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Leukoc Biol 90: 771–776. 10.1189/jlb.1010549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli VG, Wu H, Lieberman J. 2016. Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature 535: 153–158. 10.1038/nature18629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lood C, Blanco LP, Purmalek MM, Carmona-Rivera C, De Ravin SS, Smith CK, Malech HL, Ledbetter JA, Elkon KB, Kaplan MJ. 2016. Neutrophil extracellular traps enriched in oxidized mitochondrial DNA are interferogenic and contribute to lupus-like disease. Nat Med 22: 146–153. 10.1038/nm.4027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes LR, Hoyal CR, Knaus UG, Babior BM. 1999. Activation of the leukocyte NADPH oxidase by protein kinase C in a partially recombinant cell-free system. J Biol Chem 274: 15533–15537. 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinod K, Witsch T, Farley K, Gallant M, Remold-O'Donnell E, Wagner DD. 2016. Neutrophil elastase-deficient mice form neutrophil extracellular traps in an experimental model of deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 14: 551–558. 10.1111/jth.13239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B, Urrutia R, Yipp BG, Jenne CN, Kubes P. 2012. Intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps capture bacteria from the bloodstream during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe 12: 324–333. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler KD, Fuchs TA, Nauseef WM, Reumaux D, Roesler J, Schulze I, Wahn V, Papayannopoulos V, Zychlinsky A. 2011. Myeloperoxidase is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation: implications for innate immunity. Blood 117: 953–959. 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler KD, Goosmann C, Lubojemska A, Zychlinsky A, Papayannopoulos V. 2014. A myeloperoxidase-containing complex regulates neutrophil elastase release and actin dynamics during NETosis. Cell Rep 8: 883–896. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LS, Pietras EM, Uricchio LH, Hirano K, Rao S, Lin H, O'Connell RM, Iwakura Y, Cheung AL, Cheng G, et al. 2007. Inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1β is required for neutrophil recruitment against Staphylococcus aureus in vivo. J Immunol 179: 6933–6942. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone M, Stanley AC, Chen KW, Brown DL, Bezbradica JS, von Pein JB, Holley CL, Boucher D, Shakespear MR, Kapetanovic R, et al. 2018. Interleukin-1β maturation triggers its relocation to the plasma membrane for gasdermin-D-dependent and -independent secretion. Cell Rep 24: 1425–1433. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naffah de Souza C, Breda LCD, Khan MA, de Almeida SR, Câmara NOS, Sweezey N, Palaniyar N. 2018. Alkaline pH promotes NADPH oxidase-independent neutrophil extracellular trap formation: a matter of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and citrullination and cleavage of histone. Front Immunol 8: 1849 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauseef WM, Borregaard N. 2014. Neutrophils at work. Nat Immunol 15: 602–611. 10.1038/ni.2921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauseef WM, Cogley M, McCormick S. 1996. Effect of the R569W missense mutation on the biosynthesis of myeloperoxidase. J Biol Chem 271: 9546–9549. 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeli I, Radic M. 2013. Opposition between PKC isoforms regulates histone deimination and neutrophil extracellular chromatin release. Front Immunol 4: 38 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neeli I, Khan SN, Radic M. 2008. Histone deimination as a response to inflammatory stimuli in neutrophils. J Immunol 180: 1895–1902. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes P, Demaurex N, Dinauer MC. 2013. Regulation of the NADPH oxidase and associated ion fluxes during phagocytosis. Traffic 14: 1118–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donoghue AJ, Jin Y, Knudsen GM, Perera NC, Jenne DE, Murphy JE, Craik CS, Hermiston TW. 2013. Global substrate profiling of proteases in human neutrophil extracellular traps reveals consensus motif predominantly contributed by elastase. PLoS ONE 8: e75141 10.1371/journal.pone.0075141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papayannopoulos V. 2018. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 18: 134–147. 10.1038/nri.2017.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. 2010. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol 191: 677–691. 10.1083/jcb.201006052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker H, Albrett AM, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. 2012a. Myeloperoxidase associated with neutrophil extracellular traps is active and mediates bacterial killing in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. J Leukoc Biol 91: 369–376. 10.1189/jlb.0711387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker H, Dragunow M, Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. 2012b. Requirements for NADPH oxidase and myeloperoxidase in neutrophil extracellular trap formation differ depending on the stimulus. J Leukoc Biol 92: 841–849. 10.1189/jlb.1211601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse E, Rother N, Yanginlar C, Hilbrands LB, van der Vlag J. 2016. Neutrophils discriminate between lipopolysaccharides of different bacterial sources and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps. Front Immunol 7: 484 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse E, Rother N, Yanginlar C, Gerretsen J, Boeltz S, Munoz LE, Herrmann M, Pickkers P, Hilbrands LB, van der Vlag J. 2018. Cleaved N-terminal histone tails distinguish between NADPH oxidase (NOX)-dependent and NOX-independent pathways of neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Ann Rheum Dis 77: 1790–1798. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilsczek FH, Salina D, Poon KK, Fahey C, Yipp BG, Sibley CD, Robbins SM, Green FH, Surette MG, Sugai M, et al. 2010. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol 185: 7413–7425. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Kichik V, Mondragón-Flores R, Mondragón-Castelán M, Gonzalez-Pozos S, Muñiz-Hernandez S, Rojas-Espinosa O, Chacón-Salinas R, Estrada-Parra S, Estrada-García I. 2009. Neutrophil extracellular traps are induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 89: 29–37. 10.1016/j.tube.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rider P, Carmi Y, Guttman O, Braiman A, Cohen I, Voronov E, White MR, Dinarello CA, Apte RN. 2011. IL-1α and IL-1β recruit different myeloid cells and promote different stages of sterile inflammation. J Immunol 187: 4835–4843. 10.4049/jimmunol.1102048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Espinosa O, Rojas-Espinosa O, Moreno-Altamirano MM, López-Villegas EO, Sánchez-García FJ. 2015. Metabolic requirements for neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Immunology 145: 213–224. 10.1111/imm.12437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röhm M, Grimm MJ, D'Auria AC, Almyroudis NG, Segal BH, Urban CF. 2014. NADPH oxidase promotes neutrophil extracellular trap formation in pulmonary aspergillosis. Infect Immun 82: 1766–1777. 10.1128/IAI.00096-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sborgi L, Rühl S, Mulvihill E, Pipercevic J, Heilig R, Stahlberg H, Farady CJ, Müller DJ, Broz P, Hiller S. 2016. GSDMD membrane pore formation constitutes the mechanism of pyroptotic cell death. EMBO J 35: 1766–1778. 10.15252/embj.201694696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F. 2015. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526: 660–665. 10.1038/nature15514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siler U, Romao S, Tejera E, Pastukhov O, Kuzmenko E, Valencia RG, Meda Spaccamela V, Belohradsky BH, Speer O, Schmugge M, et al. 2017. Severe glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency leads to susceptibility to infection and absent NETosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 139: 212–219.e3. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollberger G, Choidas A, Burn GL, Habenberger P, Di Lucrezia R, Kordes S, Menninger S, Eickhoff J, Nussbaumer P, Klebl B, et al. 2018. Gasdermin D plays a vital role in the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci Immunol 3: eaar6689 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar6689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg SF. 2008. Structural basis of protein kinase C isoform function. Physiol Rev 88: 1341–1378. 10.1152/physrev.00034.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storek KM, Monack DM. 2015. Bacterial recognition pathways that lead to inflammasome activation. Immunol Rev 265: 112–129. 10.1111/imr.12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storisteanu DM, Pocock JM, Cowburn AS, Juss JK, Nadesalingam A, Nizet V, Chilvers ER. 2017. Evasion of neutrophil extracellular traps by respiratory pathogens. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 56: 423–431. 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0193PS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumby P, Barbian KD, Gardner DJ, Whitney AR, Welty DM, Long RD, Bailey JR, Parnell MJ, Hoe NP, Adams GG, et al. 2005. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease made by group A Streptococcus assists pathogenesis by enhancing evasion of the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 1679–1684. 10.1073/pnas.0406641102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston TL, Matthews SA, Jennings E, Alix E, Shao F, Shenoy AR, Birrell MA, Holden DW. 2016. Growth inhibition of cytosolic Salmonella by caspase-1 and caspase-11 precedes host cell death. Nat Commun 7: 13292 10.1038/ncomms13292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban CF, Reichard U, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. 2006. Neutrophil extracellular traps capture and kill Candida albicans yeast and hyphal forms. Cell Microbiol 8: 668–676. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00659.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban CF, Ermert D, Schmid M, Abu-Abed U, Goosmann C, Nacken W, Brinkmann V, Jungblut PR, Zychlinsky A. 2009. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000639 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MJ, Hollands A, Sanderson-Smith ML, Cole JN, Kirk JK, Henningham A, McArthur JD, Dinkla K, Aziz RK, Kansal RG, et al. 2007. DNase Sda1 provides selection pressure for a switch to invasive group A streptococcal infection. Nat Med 13: 981–985. 10.1038/nm1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan T, Zhao Y, Fan F, Hu R, Jin X. 2017. Dexamethasone inhibits S. aureus-induced neutrophil extracellular pathogen-killing mechanism, possibly through Toll-like receptor regulation. Front Immunol 8: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Li T, Chen S, Gu Y, Ye S. 2015. Neutrophil extracellular trap mitochondrial DNA and its autoantibody in systemic lupus erythematosus and a proof-of-concept trial of metformin. Arthritis Rheumatol 67: 3190–3200. 10.1002/art.39296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnatsch A, Tsourouktsoglou TD, Branzk N, Wang Q, Reincke S, Herbst S, Gutierrez M, Papayannopoulos V. 2017. Reactive oxygen species localization programs inflammation to clear microbes of different size. Immunity 46: 421–432. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrauch Y, Drujan D, Shapiro SD, Weiss J, Zychlinsky A. 2002. Neutrophil elastase targets virulence factors of enterobacteria. Nature 417: 91–94. 10.1038/417091a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yipp BG, Kubes P. 2013. NETosis: how vital is it? Blood 122: 2784–2794. 10.1182/blood-2013-04-457671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yipp BG, Petri B, Salina D, Jenne CN, Scott BN, Zbytnuik LD, Pittman K, Asaduzzaman M, Wu K, Meijndert HC, et al. 2012. Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nat Med 18: 1386–1393. 10.1038/nm.2847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi S, Mihalache C, Kozlowski E, Schmid I, Simon HU. 2009. Viable neutrophils release mitochondrial DNA to form neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Death Differ 16: 1438–1444. 10.1038/cdd.2009.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]