DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES

RECOMMENDATIONS

| Recommended Care |

|---|

| Prediabetes can be diagnosed with any of the following criteria |

| • Impaired fasting glucose (IFG): FPG 100 mg/dL to 125 mg/dL or |

| • Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT): 2-h plasma glucose (2-h PG) during 75-g OGTT 140 mg/dL to 199 mg/dL or |

| • HbA1c ≥5.7%-6.4% |

| Diabetes can be diagnosed with any of the following criteria: |

| • FPG ≥126 mg/dL* or |

| • FPG ≥126 mg/dL and/or 2-h PG ≥200 mg/dL using 75-g OGTT |

| • HbA1c≥6.5% ** or |

| • Random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL in the presence of classical diabetes symptoms |

| Asymptomatic individuals with a single abnormal test should have the test repeated to confirm the diagnosis unless the result is unequivocally abnormal. |

| Limited Care |

|---|

| Diabetes can be diagnosed with any of the following criteria: |

| • FPG ≥126 mg/dL* or |

| • FPG ≥126 mg/dL and/or 2-h plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL using 75-g OGTT or |

| • Random plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL in the presence of classical diabetes symptoms |

| Asymptomatic individuals with a single abnormal test should have the test repeated to confirm the diagnosis unless the result is unequivocally abnormal |

NOTE

Estimation of HbA1c should be performed using NGSP standardized method.

Capillar y glucose estimation methods are not recommended for diagnosis

Venous plasma is used for estimation of glucose

Plasma must be separated soon after collection because the blood glucose levels drop by 5%–8% hourly if whole blood is stored at room temperature.

For more details on glucose estimation visit: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK248/

*FPG is defined as glucose estimated after no caloric intake for at least 8–12 hours.

**Using a method that is National Glycohaemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) certified. For more on HbA1c and NGSP, please visit http://www.ngsp.org/index.asp

BACKGROUND

The diagnostic criteria of diabetes have been constantly evolving. Both type 1 and type 2 Diabetes mellitus (DM) are diagnosed based on the plasma glucose criteria, either the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels or the 2-h plasma post-prandial glucose (2-h PPG) levels during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), or the newer glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) criteria which reflects the average plasma glucose concentration over the previous 8–12 weeks.[1,2] The International Expert Committee Report recommend a cut-point of ≥6.5% for HbA1c for diagnosing diabetes as an alternative to fasting plasma glucose (FPG ≥7.0 mmol/L).[3] HbA1c testing has some substantial advantages over FPG and OGTT, such as convenience, pre-analytical stability, and less day-to-day fluctuations due to stress and illness.[3] Additionally, HbA1c has been recognized as marker to assess secondary vascular complications due to metabolic derailments in susceptible individuals.[2,4,5] However, given ethnic differences in sensitivity and specificity of HbA1c population-specific cut-offs might be necessary.[6,7] Moreover, measuring HbA1c is expensive as compared to FPG assessments and standardization of measurement techniques and laboratories are poorly practiced across the country.[8] Also, in several countries including India, HbA1c demonstrated inadequate predictive accuracy in the diagnosis of diabetes, there is no consensus on a suitable cut-off point of HbA1c for diagnosis of diabetes in this high-risk population.[9] In lieu of this, the panel expressed concerns on using HbA1c as sole criteria for diagnosis of diabetes particularly in resource constraint settings. Therefore, a combination of HbA1cand FPG would improve the identification of individuals with diabetes mellitus and prediabetes in limited resource settings like India.

CONSIDERATIONS

The decision about setting diagnostic thresholds values was based on the cost-effective strategies for diagnosing diabetes that were reviewed in Indian context.

RATIONALE AND EVIDENCE

Glycosylated haemoglobin cut off for diagnosis of diabetes in Indian patients

-

The RSSDI expert panel suggests

- ▫HbA1c ≥6.5% as optimal level for diagnosis of diabetes in Indian patients

- ▫HbA1c cannot be used as 'sole’ measurement for diagnosis of diabetes in Indian settings.

These recommendations are based on the Indian evidences

A recent study conducted in Singapore residents of Chinese, Malay and Indian race to assess the performance of HbA1c as a screening test in Asian populations suggested that HbA1c is an appropriate alternative to FPG as a first-step screening test, and a combination of HbA1c with a cut-off of ≥6.1% and FPG level ≥100 mg/dL would improve detection in patients with diabetes.[6]

A study to assess the diagnostic accuracy and optimal HbA1c cutoffs for diabetes and prediabetes among high-risk south Indians suggested that HbA1c ≥6.5% can be defined as a cut-off for diabetes and HbA1c ≥5.9% is optimal for prediabetes diagnosis and value <5.6% excludes prediabetes/diabetes status.[8]

Data from a community based randomized cross sectional study in urban Chandigarh suggest that HbA1c cut point of 6.5% has optimal specificity of 88%, while cut off point of 7.0% has sensitivity of 92% for diagnosis of diabetes.[10]

The results of the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) demonstrated 88.0% sensitivity and 87.9% specificity for detection of diabetes when HbA1c cut off point is 6.1% (based on 2-h post load plasma glucose) and 93.3% sensitivity and 92.3% specificity when HbA1c cut off point is 6.4% (when diabetes was defined as FPG ≥7.0 mmol/l).[11]

However, panel emphasized that HbA1c can be used in settings where an appropriate standardized method is available.

IMPLEMENTATION

Individuals should be educated on the advantages of early diagnosis and should be encouraged to participate in community screening programs for diagnosis.

PREVENTION

RECOMMENDATIONS

| Recommended Care |

|---|

| Screening and early detection |

| • Each health care service provider should have a program to detect people with undiagnosed diabetes. |

| ▫ This decision should be based on the prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and available support from health care system/service capable of effectively treating newly detected cases of diabetes. |

| ▫ Opportunistic screening for undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes is recommended. It should include: |

| ‣ Individuals presenting to health care settings for unrelated illness |

| ‣ Family members of diabetes patients |

| ‣ Antenatal care |

| ‣ Dental care |

| ‣ Overweight children and adolescents at onset of puberty |

| ▫ Wherever feasible, community screening may be done |

| • Detection programs should be usually based on a two-step approach: |

| ▫ Step 1: Identify high-risk individuals using a risk assessment questionnaire |

| ▫ Step 2: Glycaemic measure in high-risk individuals |

| • Where a random non-FPG level ≥100 (or random capillary glucose >110mg/dL) to <200 mg/dL is detected, OGTT should be performed. |

| • Use of HbA1c as a sole diagnostic test for screening of diabetes/prediabetes is not recommended. |

| • Universal screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus must be done to identify women at very high risk of future diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (CVD). |

| • People with high blood glucose during screening need further diagnostic testing to confirm diabetes while those with screen-negative for diabetes should be retested as advised by the physicians. |

| • Paramedical personnel such as nurses or other trained workers should be included in any basic diabetes care team. |

| Prediabetes |

| • People who are screen-positive for prediabetes (FPG=100-125 mg/dL or 2-h PG in the 75-g OGTT=140-199 mg/dL or HbA1c=5.7%-6.4%) should be monitored for development of diabetes annually. |

| • Should be simultaneously screened and treated for modifiable risk factors for CVD such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, and alcohol consumption. |

| • Screening strategies should be linked to health care system with capacity to provide advice on lifestyle modifications: |

| ▫ May be aligned with ongoing support national programs available at community health centres |

| ▫ Patients with IGT, IFG should be referred to these support programs. |

| • People with prediabetes should modify their lifestyle including: |

| ▫ Attempts to lose 5%-10% of body weight if overweight or obese |

| ▫ Participate in physical activity (e. g., walking) for at least 1-h daily if overweight or obese. and at least half hour daily if normal weight |

| ▫ 6-8 h of sleep daily |

| • Healthy lifestyle measures including diet and physical activity are equally important for non-obese patients with prediabetes. |

| • People with prediabetes failing to achieve any benefit on lifestyle modifications after 6 months may be initiated on oral antidiabetic agents (OADs): |

| ▫ Metformin: In younger individuals with one or more additional risk factors for diabetes regardless of BMI, if overweight/obese and having IFG + IGT or IFG + HbA1c >5.7%, addition of metformin (500 mg, twice daily) after 6 months of follow-up is recommended. |

| ▫ Alternatively, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs) such as acarbose or voglibose may be initiated if metformin is not tolerated. |

| • Other pharmacological interventions with pioglitazones, orlistat, vitamin D, or bariatric surgery are not recommended. |

| • People with prediabetes should be educated on: |

| ▫ Weight management through optimal diet and physical activity |

| ▫ Stress management |

| ▫ Avoidance of alcohol and tobacco |

| Limited Care |

|---|

| • The principles for screening are as for recommended care. |

| • Diagnosis should be based on FPG or capillary plasma glucose if only point-of-care testing is available. |

| • Using FPG alone for diagnosis has limitations as it is less sensitive than 2-h OGTT in Indians. |

| Prediabetes |

| • The principles of detection and management of prediabetes are same as for recommended care. |

| • Linkages to healthcare system with capacity to provide advice on lifestyle modifications and alignment with on-going support national programs available at community health centres where patients detected with prediabetes can be referred are critical. |

BACKGROUND

Chronic hyperglycaemia is associated with significantly higher risk of developing diabetes related micro-and macrovascular complications. Early detection of diabetes/prediabetes through screening increases the likelihood of identifying asymptomatic individuals and provides adequate treatment to reduce the burden of diabetes and its complications. Through a computer simulated model on the data from the Anglo-Danish-Dutch study of intensive treatment in people with screen-detected diabetes in primary care (ADDITION-Europe), Herman et al. have demonstrated that the absolute risk reduction (ARR) and relative risk reduction (RRR) for cardiovascular (CV) outcomes are substantially higher at 5 years with early screening and diagnosis of diabetes when compared to 3 years (ARR: 3.3%; RRR: 29%) or 6 years of delay (ARR: 4.9%; RRR: 38%).[12] Adopting a targeted approach and utilizing low-cost tools with meticulous planning and judicious allocation of resources can make screening cost-effective even in resource-constrained settings like India.[13] Furthermore, in a systematic review and meta-analysis, screening for type 2 DM (T2DM) and prediabetes has been found to be cost-effective when initiated at around 45–50 years of age with repeated testing every 5 years.[14]

Prediabetes is defined as blood glucose concentration higher than normal, but lower than established thresholds for diagnosis of diabetes. People with prediabetes are defined by having IGT (2-h PG in the 75-g OGTT: 140-199 mg/dL) or IFG (FPG: 100-125 mg/dL). It is a state of intermediate hyperglycaemia with increased risk of developing diabetes and associated CV complications and therefore early detection and treatment of IGT and IFG is necessary to prevent the rising epidemic of diabetes and its associated morbidity and mortality. Although, IDF guideline does not deal with screening and management of prediabetes, the ADA recommends screening for prediabetes and T2DM through informal assessment of risk factors or with an assessment tool.[1] To prevent the progression of pre-diabetes to T2DM, ADA recommends an intensive behavioural lifestyle intervention (BLI) programme (eg, medical nutrition therapy (MNT) and physical activity) in susceptible individuals.[15]

Based on the Indian Council of Medical Research-INdiaDIABetes (ICMR-INDIAB) study conducted in 15 states, the overall prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes was 7.3% (95% CI: 7.0, 7.5) and 10.3% (10.0, 10.6), respectively.[16] Another study conducted among residents of urban areas of east Delhi-The Delhi Urban Diabetes Survey (DUDS) demonstrated a strikingly high prevalence of diabetes (18.3%: known, 10.8%; newly detected, 7.5%) and prediabetes (21% [WHO criteria], 39.5% [ADA criteria]).[17] Given the high prevalence rates of prediabetes in our country, the RSSDI panel holds the opinion that including screening and management aspects of prediabetes is logical and will provide an important opportunity for prevention of diabetes in India.

CONSIDERATIONS

The decision about conducting a screening program should be based on the following local factors that were reviewed in Indian context: limited resources, lack of quality assurance in labs, high-risk population for diabetes, large unrecognized burden of undiagnosed diabetes, high prevalence of prediabetes, fast conversion rates from population prediabetes to diabetes, large rural–urban divide, largely sedentary population in urban areas, onset of T2DM at least a decade earlier that in western countries, newer technologies for screening, cost of early detection to the individual, capacity for carrying out screening and capacity to treat/manage screen-positive individuals with diabetes and prediabetes.

RATIONALE AND EVIDENCE

Opportunistic screening

The panel suggests that screening should be opportunistic but not community-based as they are less effective outside health care setting and poorly targeted, i. e., it may fail to identify individuals who are at risk. In a cross-sectional study on 215 participants in a tertiary care hospital in Haryana, opportunistic screening showed that for every seven patients with known diabetes, there are four undiagnosed diabetes patients.[18] In the ICMR-INDIAB study, the ratio of known-to-unknown diabetes was at least 1:1, with rural areas being worse than urban.[16] Opportunistic screening is more cost-effective with better feasibility within the health care system while minimizing the danger of medicalization of a situation. Furthermore, patients diagnosed through this screening have good prognosis over those diagnosed by clinical onset of symptoms.[19]

Risk assessment questionnaire

There are two risks cores specific for Indians developed by Madras Diabetes Research Foundation (MDRF) and by Ramachandran et al.[20] [Annexures 1 and 2]. Both risk scores are validated and are being used widely in our country. The MDRF-Indian Diabetes Risk Score (IDRS) tool has been found to be useful for identifying undiagnosed patients with diabetes in India and could make screening programs more cost-effective.[21] It is also used in several national programs for prevention of not only diabetes but also cardiometabolic diseases such as stroke. Also its applicability in identifying prevalence of diabetes-related complications such as CAD, peripheral vascular disease (PVD), and neuropathy among T2DM patients has been found to be successful.[22] Risk scores by Ramachandran et al. is simple with few risk variables listed and can be applied at any worksite by a paramedical personnel and help identification of the high risk group by the presence of a minimum of 3 or more of the risk variables used in the risk score.[23]

Random plasma glucose level

The panel endorse the IDF recommendation on the need to measure FPG and perform OGTT based on random plasma glucose levels which are associated with the development of diabetes (2-h PG ≥200 mg/dL) or prediabetes (2-h PG ≥140 to <200 mg/dL).[24] According to IDF guidelines, FPG values ≤100 mg/dL are considered normal and FBG >100 mg/dL is considered to be at risk of developing diabetes. Further, individuals with FPG between 100-125 mg/dL have IFG, suggesting an increased risk of developing T2DM. Confirming the FPG levels ≥126 mg/dL by repeating tests on another day, confirm diabetes.[25] In a cross-sectional study on 13,792 non-fasting National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) in participants without diagnosed diabetes, random blood sugar level of ≥100 mg/dL was strongly associated with undiagnosed diabetes.[26] Prediction of diabetes carried out on the basis of this data showed that random blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL was 81.6% (95% CI: 74.9%, 88.4%) sensitive and 78% (95% CI: 76.6%, 79.5%) specific to detect undiagnosed diabetes, which is better than current screening guidelines.[27] Evidence from community-based opportunistic screening in India suggests that random capillary blood glucose level of ≥110 mg/dL can be used to identify those individuals who should undergo definitive testing for diabetes or prediabetes.[28] In patients with no history of diabetes or prediabetes, random blood glucose screening is effective in promoting additional screening among high-risk age groups and encourages patients to make lifestyle changes.[29]

The panel suggest that although the present criteria of IFG (100-125 mg/dL) may be sensitive and has lesser variability, measuring 2-h PG levels may give more accuracy and confidence in targeting this population for prevention strategies.

Glycosylated haemoglobin as criteria for screening

A meta-analysis of 49 studies involving patients aged ≥18 years reported that HbA1c as a screening test for prediabetes has lesser sensitivity (49%) and specificity (79%).[30] Moreover, the use of ADA recommended HbA1c threshold value of 6.5% for diagnosis of diabetes may result in significant under diagnosis.[31] The predictive value of HbA1c for T2DM depends on various factors such as ethnicity, age, and presence of iron deficiency anaemia (IDA).[32,33,34,35] In a cohort study on individuals from Swedish and Middle-East ancestry, HbA1 ≥48 mmol/mol had a predictive sensitivity of 31% and 25%, respectively, for T2DM.[34] Furthermore, HbA1c values ≥42 and ≥39 mmol/mol as predictors for prediabetes were associated with a sensitivity of 15% and 34% in individuals of Swedish and 17% and 36% in individuals of Middle-East ancestry. Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies including 49,238 individuals without T2DM reveal that HbA1c values are higher in Blacks (0.26% (2.8 mmol/mol), p <0.001), Asians (0.24% (2.6 mmol/mol), p <0.001), and Latinos (0.08% (0.9 mmol/mol); p <0.001) when compared to Whites.[33] Moreover, significantly high HbA1c levels are observed in patients with IDA when compared to healthy subjects (5.51±0.696 vs 4.85±0.461%, p <0.001) and HbA1c levels decline significantly after treatment with iron supplements in IDA subjects (5.51±0.696 before treatment vs 5.044±0.603 post-treatment; p <0.001).[35]

The panel recommends the use of HbA1c as sole criteria for screening of diabetes/prediabetes would be inappropriate in most settings in India, at this time. However, HbA1c may be utilized for screening if it is being done from a laboratory known to be well-equipped with external quality assurance.[36]

The panel expresses concerns of high prevalence of anaemia and high prevalence of haemoglobinpathies in certain regions/populations particularly from the North East as these can have significant impact when HbA1c is used as diagnostic test for screening.

Diagnosis of prediabetes

Table 1.

Glycaemic values for Indian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

| Glycaemic parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| FPG (mg/dL) | 100-125 |

| 2-h PPG during 75-g OGTT (mg/dL) | 140-199 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7-6.4 |

2-h PPG: 2-h postprandial glucose, FPG: Fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c: Glycosylated haemoglobin, OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test

Pregnancy as a critical target for diabetes prevention strategies

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a known risk factor for T2DM. Women with GDM have a 7-fold higher risk of developing T2DM and are at a higher risk of developing metabolic syndrome and CVD.[37,38] Also children of GDM mothers are at higher risk of development of T2DM later in life compared with non-GDM mothers.[39]

Given the high prevalence of GDM in Indian women, early detection and effective treatment can prevent all adverse outcomes of pregnancy and result in a normal and healthy postpartum course for both mother and baby.[40]

Children and adolescents: Screening strategies

Screening studies in obese adolescents have reported a prevalence of 0.4% up to 1% of type 2 diabetes mellitus in obese children ≥12 years.[41]

Overweight (BMI >90 percentile) or obese children (BMI >99.5 percentile) with familial history of T2DM, children from a predisposed race/ethnicity such as Asian, American Indian, etc., with associated risk factors such as IR, dyslipidemia, polycystic ovarian syndrome must be screened periodically.

Consistent with the recommendations for screening in adults, children at substantial risk for the development of T2DM should also be tested. The ADA recommends screening in high risk overweight children and adolescents at onset of puberty. The screening must be performed every 2 years from diagnosis using fasting glucose or OGTT.

Rescreening

The panel emphasize on striking balance between cost of screening and cost of treating complications.

On the basis of expert opinion of the panel, general population should be evaluated for the risk of diabetes by their health care provider on annual basis beginning at age 30.

Yearly or more frequent testing should be considered in individuals if the initial screen test results are in the prediabetes range or present with one or more risk factors that may predispose to development of diabetes.

The panel opine that screening programs should be linked with health care system and ongoing national prevention programs that will facilitate effective and easy identification of people at high-risk of developing diabetes and its complications.

Paramedical personnel

Paramedical personnel play a key role as facilitators in imparting basic self-management skills to patients with diabetes and those at risk. They can be actively involved in implementing diet and lifestyle changes, behavioural changes, weight management, pre-pregnancy counselling, and other preventive education.

-

Nurses or other trained workers in primary care and hospital outpatient settings can:

- ▫Help in identification of individuals at risk of diabetes

- ▫Help in recognition of symptoms of diabetes, hypoglycaemia, and ketosis

- ▫Help in timely referral of these cases.

-

Nurses or nurse educators in secondary and tertiary care settings can:

- ▫Perform all the above activities

- ▫Help in prevention and treatment of hypoglycaemia

- ▫Help in problems with insulin use.

EVIDENCE

It has been observed that Indians are more prone to diabetes at a younger age and at a lower BMI compared to their Western counterparts.[42,43] The reason for this difference has been attributed to the “Asian Indian phenotype” characterized by low BMI, higher body fat, visceral fat and WC; lower skeletal muscle mass and profoundly higher rates of IR.[44,45] The 10-year follow-up data of the CURES that assessed incident rates of dysglycaemia in Asian Indians are now available.[46] In a cross-sectional study on slum dwellers in Bangalore, prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes was identified as 12.33% and 11.57% in people aged ≥35 years.[47] Moreover, in case of female gender, increasing age, overweight and obesity, sedentary lifestyle, tobacco consumption, and diet habits were strongly associated with prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes. Similarly, in a cross-sectional study in Tamil Nadu, prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes was identified as 10.1% and 8.5% respectively.[48] Risk factors associated with prediabetes in this study were age of 40 years, male gender, BMI >23 kg/m2, WHR for men >1 and women >0.8, alcohol intake and systolic blood pressure (SBP) >140 mmHg. Likewise, in a household survey in Punjab, using World Health Organization STEP wise Surveillance (WHO STEPS) questionnaire, prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes were identified as 8.3% and 6.3% respectively.[49] Risk factors that were significantly associated with diabetes were age (45–69 years), marital status, hypertension, obesity and family history of diabetes. A study on 163 north Indian subjects proposed severity of IR and family history of diabetes as determinants of diminished beta-cell function leading to diabetes in MS.[50] Predictors of progression to impaired glycaemia were advancing age, family history of diabetes, 2-h PPG, HbA1c, low density lipoprotein (LDL) and HDL, and physical inactivity.

Despite the escalating burden, the current evidence on the prevention of T2DM and its complications in India is scarce. Though the general practitioners in India are well aware of symptoms and complications of T2DM, they are oblivious regarding the use of standard screening tests resulting in significant delay in diagnosis and treatment.[51]

-

Considering significant resource constraints together with awareness levels of patients and physicians, there is a need for prevention strategies that are culturally relevant and cost-effective.[52] Following section covers evidence from Indian studies on various strategies that are helpful in detecting and minimizing the risk of development of diabetes and its associated complications.

- ▫Simplified tools for detection of diabetes such as IDRS developed by MDRF and Diabetes Risk Score for Asian Indians devised by Prof. A. Ramachandran are found to be useful for identifying undiagnosed patients with diabetes in India. Use of these tools could make screening programs more cost-effective.[20,21] Studies from different regions of India including Jammu, Kashmir, Chennai, Haryana, Delhi, Jabalpur, and Kerala estimated the utility of MDRF-IDRS in identifying risk for DM and prediabetes in Indian adult population and found statistically significant association between IDRS and DM patients indicating MDRF-IDRS to be efficient tool to screen and diagnose the huge pool of undiagnosed diabetics in India.[53,54,55,56,57,58]

- ▫It is also found by that identifying the presence of multiple risk factors could be used as a simple measure of identifying people at high risk of diabetes.[59]

- ▫Several landmark studies have shown that lifestyle intervention could prevent the progression to T2DM by about 30–60%.[62] Evidence from literature suggests that initial lifestyle interventions are cost-effective[63] and can significantly reduce the incidence of diabetes in Asian Indians with IGT or with combined IGT+IFG.[64,65,66] The evidence from the randomized, controlled, D-CLIP program showed that adding metformin in a stepwise manner to lifestyle education is an effective method for preventing or delaying diabetes in adults with prediabetes, even in a resource-challenged setting. During the 3 years of follow-up, the RRR was 32% (95% CI: 7–50) in intervention participants compared with control. The RRR varied by prediabetes type (IFG+IGT, 36%; iIGT, 31%; iIFG, 12%; p = 0.77) and was stronger in patients aged ≥50 years, male, or obese.[66]

- ▫In patients in whom metformin is contraindicated, AGIs such as acarbose or voglibose may be used, as they confer lesser side effects compared to other OADs. Furthermore, lifestyle intervention with diet and exercise in those with IGT can significantly decrease the incidence of diabetes and its complications[67,68] while providing long-term beneficial effects for up to 20 years.[69]

- ▫Several observational studies have reported an association between low levels of vitamin D and increased risk for T2DM, and a few clinical studies that vitamin D could improve the function of beta cells, which produce insulin. However, in the recent D2D study, vitamin D supplementation for a median 2.5 years did not significantly affect prevent T2DM development in a high-risk population.[70]

- ▫A systematic review and meta-analysis of 50 trials identified that lifestyle intervention reduced risk of progression to diabetes by 36% over 6 months to 6 years which attenuated to 20% by the time of follow-up results of the trials were measured.[30] Another systematic review and meta-analysis showed that physical activity in prediabetes subjects improves oral glucose tolerance, FPG and HbA1c levels, and maximum oxygen uptake and body composition.[71] Results indicated that physical activity promotion and participation slow down the progression of disease and decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with T2DM. Optimal sleep (7–8 h/night) has been shown to maintain metabolic health, aid in weight loss, and increase insulin sensitivity, while short duration (<5–6 h) or longer duration (>8–9 h) of sleep was associated with increased risk of diabetes.[72,73] Similar results were observed in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 articles which determined that the pooled relative risks for T2DM were 1.09 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.15) for each 1-h shorter sleep duration among individuals who slept <7 h/day and 1.14 (1.03, 1.26) for each 1-h increment of sleep duration among individuals who slept longer, when compared to 7-h sleep/day.[74]

- ▫Interventions predominantly based on counselling and education are found to be effective in preventing/reducing the risk of developing diabetes and its complication and also helps in improving dietary patterns of individuals with prediabetes and diabetes.[52,75] Mobile phone messaging was found to be an inexpensive and most effective alternative way to deliver educational and motivational advice and support towards lifestyle modification in high-risk individuals.[23] Recent studies have proven the advantages of using mhealth strategies in promotion of prevention of NCDs. The WHO has recommended the use of such strategies for large scale programmes.[76,77]

- ▫Dietary interventions such as high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet,[78] fibre-rich,[79] and protein-rich diet[80,81] were found to have definite role in prevention of diabetes. Furthermore, components of whole grains, and fruit and green leafy vegetables such as cereal fibre and magnesium, are consistently associated with lower risk of developing T2DM.[80]

- ▫Evidence from the CURES and Prevention Awareness Counselling and Evaluation (PACE) diabetes project suggests that awareness and knowledge regarding diabetes is inadequate among patients in India and implementation of educational programs at massive level can greatly improve the awareness on diabetes and its associated CVD.[82,83] Moreover, mass awareness and screening programs through community empowerment were found to effectively prevent and control diabetes and its complications such as foot amputations.[84]

- ▫A prospective, randomized controlled study of Fenugreek conducted in nondiabetic people with prediabetes demonstrated a significant reduction in FPG, PPG and LDL and showed insulinotropic effect.[85]

- ▫Currently, the role of yoga and fenugreek in the prevention of diabetes is being evaluated in the Indian prevention of Diabetes Study by RSSDI.

IMPLEMENTATION

A clear and transparent decision should be made about whether or not to endorse a screening strategy. If the decision is in favour of screening, this should be supported by local protocols and guidelines, and public and health-care professional education campaigns.

TREATMENT 1: MEDICAL NUTRITION THERAPY (MNT) AND LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

| Recommended Care |

|---|

| MNT |

| • The nutrition chart and support should be made in conjunction with a trained nutritionist along with physician/diabetologist. |

| • Carbohydrates |

| ▫ Carbohydrate content should be limited to 50%-60% of total calorie intake. |

| ▫ Complex carbohydrates should be preferred over refined products. |

| ▫ Low glycaemic index (GI) and low glycaemic load (GL) foods should be preferred. |

| ▫ Quantity of rice (GI: 73) should be limited as it has high GI; Brown rice (GI: 68) should be preferred over white rice. |

| ▫ Fibre intake: 25-40 gm per day. |

| • Proteins |

| ▫ Protein intake should be maintained at about 15% of total calorie intake. |

| ▫ Quantity of protein intake depends on age, sarcopenia and renal dysfunction. |

| ▫ Non-vegetarian foods are sources of high quality protein, however intake of red meat should be avoided. |

| • Fats |

| ▫ Fat intake should be limited (<30% of total calorie intake). |

| ▫ Oils with high monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) should be used. |

| ▫ Use of 2 or more vegetable oils is recommended in rotation. |

| ▫ For non-vegetarians, consumption of 100-200 g of fish/week is advised as good source of PUFA and for vegetarians, vegetable oils (soybean/safflower/sunflower), walnuts and flaxseeds are recommended. |

| ▫ Avoid consumption of foods high in saturated fat (butter, coconut oil, margarine, ghee). |

| ▫ Saturated fatty acids (SFAs) intake should be less than 10% of total calories/day (<7% for individuals having high triglycerides). |

| ▫ Use of partially hydrogenated vegetable oils (Vanaspati) as the cooking medium should be avoided. |

| ▫ Reheating and refrying of cooking oils should be avoided. |

| • Food groups and patterns |

| ▫ Diet rich in fruits, leafy vegetates, nuts, fibre, whole grains and unsaturated fat is preferred. |

| ▫ Food plate should include pulses, legumes, unprocessed vegetables and low fat dairy. |

| ▫ Extreme diets including low-carbohydrate ketogenic must be planned and executed following consultation with physician and nutritionist, and for a short period. |

| ▫ Overall salt consumption should be <5 g/day (with sodium consumption <2300 mg/day). |

| ▫ Avoid or decrease alcohol intake. |

| ▫ Smoking cessation should be advised to all. Smoking cessation therapies may be provided under observation for patients who wish to quit in step-wise manner |

| ▫ Sugar sweetened beverages are best avoided. |

| ▫ Artificial sweeteners may be consumed in recommended amounts. |

| ▫ Meal plans with strategic meal replacements (partial or full meal replacements) may be an option under supervision when feasible. |

| • Lifestyle modifications |

| • Recommended care could be imparted by physician and diabetes educator. |

| • Careful instructions should be given for initiating exercise programme. Help of a physical instructor can be taken. |

| • Lifestyle advice should be given to all people with T2DM at diagnosis. It should be an effective option for control of diabetes and increasing CV fitness at all ages and stages of diabetes. |

| • Lifestyle intervention is a cost-effective approach in prevention of T2DM. |

| • Lifestyle interventions should be reviewed yearly or at the time of any treatment or at every visit. |

| • Advise people with T2DM that lifestyle modification, by changing patterns of eating and physical activity, can be effective in managing several adverse risk factors related to T2DM. |

| • Physical activity should be introduced gradually, based on the patient’s willingness and ability and the intensity of the activity should be individualized to the specific goals |

| • A minimum of 150 min/week of physical activity is recommended for healthy Indians in view of the high predisposition to develop T2DM and CAD |

| ▫ ≥30 min of moderate-intensity aerobic activity each day |

| ▫ 15-30 min of work-related activity |

| ▫ 15 min of muscle-strengthening exercises (at least 3 times/week) |

| • While effect of yogic practices is encouraging, it should not replace aerobic exercise. |

| • Use of monitoring tools like accelerometers, GPS units, pedometers, mobile based apps or devices to measure the intensity and duration of physical activity may be encouraged. |

| Behavioural lifestyle intervention (BLI) |

| • BLI involves patient counselling for strategies such as tailoring goals, self-monitoring and stimulus control. |

| • BLI approaches have shown to improve adherence to lifestyle changes and achieve more sustained effects. |

| • Diabetes self-management support is important and could be done with physician or educator with small groups or face-to-face discussions in chat rooms. |

| Limited Care |

|---|

| • Nutritional counselling may be provided by health care providers (HCPs) trained in nutrition therapy, not necessarily by an accredited dietician nutritionist |

| • Overall, reduced consumption of simple carbohydrates, sugar and fried foods and higher consumption of complex carbohydrates with high protein intake are recommended. |

| • Salt intake should be in moderation. |

| • Encourage increased duration and frequency of physical activity (where needed). |

| • Mass awareness campaign for healthy diet and lifestyle should be conducted. |

BACKGROUND

Unhealthy diet and sedentary lifestyle have been identified as fundamental modifiable risk factors in T2DM. Rapid urbanization and rampant availability of westernized, processed foods that contain high amounts of refined carbohydrates, saturated fats and added sugars have dramatically changed the local food environment in India.[86] Along with increasing physical inactivity, these adverse dietary changes have been associated with detrimental influences on the onset and progression of T2DM in India.[87,88,89] MNT is a systematic approach to optimize dietary intake in order to achieve metabolic control and maximize favourable treatment outcomes in T2DM. Conceptually, MNT involves counselling and recommendations from a registered dietician (RD) under the regular supervision of the consulting diabetologists.

Current global clinical practice guidelines for T2DM from the ADA, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and IDF advocate the importance of integrating MNT in the management of T2DM as a first-line therapy and provide consistent recommendations for day-to-day nutritional requirements.[90,91] MNT is a lifestyle transforming process that is beyond calorie restriction and portion control. Implementation of MNT in India is challenging owing to its cultural and culinary diversity. Consumption of high amounts of carbohydrates including ghee-laden sweets loaded with sugar or jaggery are inherent to the standard Indian diet and have religious significance, thus escalating the challenges of restricting carbohydrate intake. Therefore designing individualized diet plans as a part of MNT in India should consider regional, cultural, economic and agricultural factors as these have a marked influence on the acceptance of MNT by the patient.

Role of medical nutrition therapy in prevention and management

Dietary counselling and adherence of healthful, calorie-restricted diet and regular exercise have been associated with lower rates of incident diabetes in Indian men with impaired glucose tolerance. Community health programs and implementation of MNT-based model meals in rural and urban populations from South and North of India have shown favourable changes in dietary patterns and improvements in several parameter including BMI, waist circumference, fasting blood glucose and so on.[75,92,93] A stepwise Diabetes Prevention Program lowered the 3-year risk of diabetes by 32% (95% CI: 7, 50) in obese Asian Indian adults with any form of prediabetes.[66] These studies including few others involving Indians with risk factors for diabetes reported benefits of dietary approaches such as high consumption fibre-rich foods, high-protein meal replacements, or replacement of polished white rice with whole grain brown rice and increased intake of fruits and vegetables.[94,95]

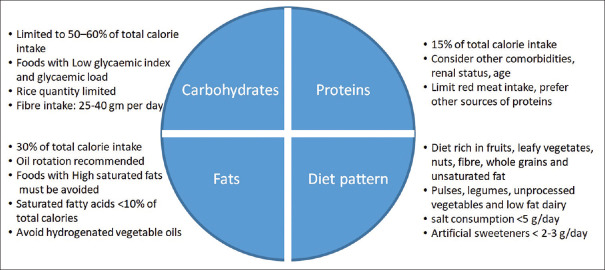

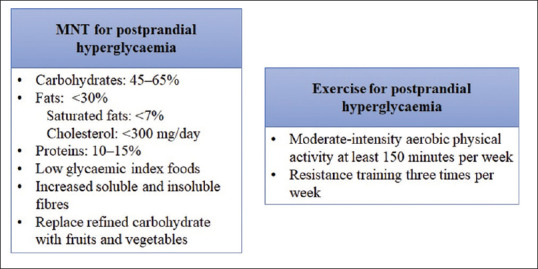

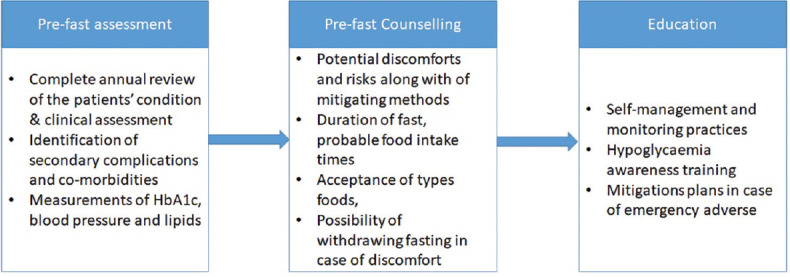

The landmark lifestyle intervention program, Look Ahead examined the effects of calorie-restricted diet and reduce intake of high-GI carbohydrates such as sugar, flavoured beverages and high calorie snacks on glycaemic control and prevention of CV complications. At 11 years, participants benefited from the regimented diet and had an average weight loss of 5% along with substantial improvements in HbA1c levels, blood pressure, lipid profile and overall fitness and well-being.[96] In a year-long prospective randomized study from India, individuals with T2DM, randomized to MNT, achieved significant lowering of HbA1c and all lipid parameters, especially triglyceride levels. This study involved 20 dieticians and reported the success of a guided, evidence-based, individualized MNT versus usual diabetes care.[97] Based on these clinically relevant observations in the Indian population, the RSSDI recommends the adoption of dietician-guided MNT as an integral component of diabetes management [Figure 1]. The MNT and lifestyle modifications should be individualized based on diseases profile, age, sociocultural factors, economic status, and presence of sarcopenia and organ dysfunction.

Figure 1.

Recommendation for MNT in patients with T2DM.

MNT: Medical nutrition therapy; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus

RATIONALE AND EVIDENCE

Carbohydrate monitoring

Meal planning approaches should include carbohydrate counting, exchanges or experience based estimation and measurement of GI and GL to monitor the amount of carbohydrate in food and understand its physiological effects of high-carbohydrate diets.[98,99]

High-carbohydrate, low-fat diets

Although there is a dichotomy in recommendations with regard to high-or low-carbohydrate diets, historic data from India suggest the metabolic benefits of high-carbohydrate, high-fibre, low-fat diets as opposed to a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet.[100,101] Recent studies support the implementation of a long-term high-carbohydrate high-fibre diet in promoting weight loss, improving glycaemic control, and lowering CV risk.[102,103,104,105] High carbohydrate diets should comprise large amounts of unrefined carbohydrate and fibre such as legumes, whole grains, unprocessed vegetables, and fruits.[87,106,107] High carbohydrate diet regimens in T2DM patients have been associated with favourable weight loss and reductions in plasma glucose, HbA1c and LDL levels with good adherence and sustainability, comparable with low carbohydrate diets. The concern of possible untoward effect of high carbohydrate diet on lipid profile (increase in triglycerides and reductions in HDL) and CV risk can be mitigated by lowering the glycaemic index of diets by incorporating fibre-rich foods.[99]

Cross-sectional data from the CURES suggests that Indians consume high amounts of refined grains (~47% of total calories), which is associated with significant increases in waist circumference (p<0.0001), systolic blood pressure (p<0.0001), diastolic blood pressure (p=0.03), fasting blood glucose (p=0.007), serum triglyceride (p<0.0001), lower HDL (p<0.0001), and insulin resistance (p<0.001). Further, Indians who consumed refined grains were more predisposed develop metabolic syndrome (odds ratio [OR]: 7.83; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 4.72, 12.99) and insulin resistance versus those consumed lower quantities.[108]

In an assessment of the quality and type of carbohydrates in a subset of patients from the CURES study, consumption of refined grain (OR: 5.31; 95% CI: 2.98, 9.45; p<0.001), total carbohydrate (OR: 4.98; 95% CI: 2.69, 9.19; p<0.001), GL (OR: 4.25; 95% CI: 2.33, 7.77; p<0.001), and GI (OR: 2.51; 95% CI: 1.42, 4.43; p=0.006) positively correlated with the risk of T2DM. In contrast, high intake of dietary fibre showed an inversely correlation with T2DM (OR: 0.31; 95 % CI: 0.15, 0.62; p<0·001).[107]

Additional analysis of the data from the CURES study population revealed the detrimental dietary habits among South Indian adults (daily energy intake: carbohydrates [64%], fat [24%], protein [12%]) that escalates the risk of T2DM. It was observed that refined cereals contributed to nearly 46% of total energy intake, followed by visible fats and oils (12.4%), pulses and legumes (7.8%), and intake of micronutrient-rich foods (fruits, vegetables, fish etc.) was inadequate and below the recommended standards of FAO/WHO.[109]

Given that carbohydrates are an inherent part of the staple Indian diet and Indians habitually tend to consume high amounts of carbohydrates, improving the quality of carbohydrates in the diet by replacing high-GI carbohydrates with fibre-rich, low GI counterparts.[110] It was observed that consumption of brown rice significantly reduced 24-h glycaemic response 24-h (p=0.02) and fasting insulin response (p=0.0001) in overweight Asian Indians.[111]

Replacement of white rice with brown rice was found to be feasible and culturally appropriate in Indian overweight adults and correlated with lower risk of T2DM.[112] Fortification of humble Indian dishes with fibre-rich alternatives, for example adding soluble fibre in the form of oats in upma or improving the glycaemic quality of Indian flatbreads (rotis or chapattis) by adding wheat flour with soluble viscous fibres and legume flour have shown favourable outcomes on the lipid profile and postprandial glucose and insulin responses in T2DM patients.[113,114,115,116]

Sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages increase the dietary GL. Overall, the consumption of total sugar (25.0 kg/capita) among Indians exceeds the average global annual per capita consumption (23.7 kg).

Consumption of sweets, sweetened beverages (e. g. lassi, aamras) or addition of sugars in curries, gravies etc. have customary and regional importance in India.[117] It is observed that in urban South India, the added sugars in hot beverages (tea or coffee) majorly contribute to sugar intake and account for around 3.6% of total GL.[107]

Low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet

Low-carbohydrate diets may be particularly beneficial in patients with impaired glucose tolerance, and obesity, however to balance the macronutrient content, these diets tend to be high in fats and proteins. Therefore, while adopting such diets, fat intake should occur mainly in the form of MUFA with a parallel decrease in saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and trans fatty acids (TFAs). As the metabolic pathways of carbohydrates and fats are interlinked, low carbohydrate diets that are high on fats and protein are associated with long-term effects such as ketosis, and adverse lipid, and renal effects.[118]

Evidence suggest that T2DM patients on low carbohydrate diet achieve favourable outcomes due to reduced energy intake and prolonged calorie restriction and not due to low carbohydrate intake. Obese T2DM patients should therefore consider switching to a low-carbohydrate diet designed based on calorie restriction as well as regulated intake of fats to reduce the incidence of T2DM and myocardial infarction.[119,120] These diets should be considered for a limited period only.

In a small study, overweight patients with T2DM were randomized to a very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet and lifestyle modifications such as physical activity, sleep etc. had significantly improved their glycaemic control (p=0.002) and lost more weight (p<0.001) than individuals on a conventional, low-fat diabetes diet program.[121]

In another similarly designed randomized controlled trial, overweight individuals with T2DM or elevated HbA1c levels on very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet for a period of 12 months had significant reductions in HbA1c levels (p=0.007) and body weight (p<0.01) than participants on moderate-carbohydrate, calorie-restricted, low-fat diet.[122]

In a 24-week interventional study, a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet in patients with T2DM favourably improved body weight, glycaemic and lipid profiles in patients with T2DM as compared with patients on a low calorie diet.[123]

Low glycaemic index of pulses and pulse-incorporated cereal foods

As compared with other Western or Asian diets, traditional Indian diets comprising dal, roti, rice, and curry provide a wholesome supply of balanced, mixed nutrients. The mix of various pulses and legumes in a standard Indian meal offer variations in the glycaemic and insulinaemic indices that are attributed to the nature of available and non-available (non-starchy polysaccharides) carbohydrates in the foods and alterations in rates of carbohydrate absorption.[124,125] Inclusion of grams and pulses in rice or wheat-based starchy high GI diets reduces the glycaemic index and brings satiety along with adequate supply of calories. Meals with mixed sources of cereals, pulses and legumes contribute to regulation of insulin and glycaemic responses.

Combining acarbose in regular daily diets was associated with significant decline in postprandial blood glucose in T2DM patients, including those who failed prior treatment with OADs.[126]

Similarly, consumption of adai dosa (a type of Indian pancake with 75% pulses and 25% cereals) versus normal diet (75% cereal and 25% pulses) was associated with reduction in body weight and significant (p<0.01) lowering of HbA1c.[127]

Inclusion of nuts (almond, walnuts, cashews, pistachios, hazelnuts) in diet corresponding to approximately 56 g (1/2 cup) of nuts was associated with significant reduction in HbA1c (mean difference: − 0.07% [95% CI: −0.10, −0.03%]; p=0.0003) and fasting glucose (mean difference: −0.15 mmol/L [95% CI: −0.27, −0.02 mmol/L]; p=0.03) in individuals with T2DM versus isocaloric diets without nuts. The improvement was mainly attributed to lowering of GI due to replacement by nuts.[128]

In an analysis of dietary patterns in India, diets rich in rice and pulses were associated with lower risk of diabetes versus diet models that had more sweets and snacks.[129]

Legumes such as chickpeas are also low glycaemic foods and when substituted for similar serving of egg, baked potato, bread, or rice lower the risk of T2DM and may be beneficial in elderly individuals with CV risk.[130]

Consumption of oils among Indian population

In the rural South Indian population from the CURES study, highest intake of fats directly correlated with risk of abdominal obesity (p<0.001), hypertension (p=0.04), and impaired fasting glucose (p=0.01). In particular, sunflower oil was found to be most detrimental when compared to traditional oils and palmolein.[131]

Supporting this finding, the risk of metabolic syndrome was higher among users of sunflower oil (30.7%) versus palmolein (23.2%) or traditional (groundnut or sesame) oil (17.1%, p<0.001) in Asian Indians. Higher percentage of linoleic acid PUFA in sunflower oil was correlated with the risk of metabolic syndrome.[132] The observations from these studies are preliminary and should be further investigated.

Managing dietary intervention by replacing refined cooking oils with those containing high percentage of MUFA (canola and olive oil) in Asian Indians with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease was associated with significant reduction in body weight and BMI (p<0.01, olive oil), improvements in fasting insulin level and homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance and β-cell function (p<0.001, olive oil), increase in high-density lipoprotein level (p=0.004, olive oil), and decrease in fasting blood glucose (p=0.03) and triglyceride (p=0.02) level (in canola group).[133]

Increasing use of saturated fat, low intake of n-3 PUFAs, and increase in TFAs was observed among India patients with T2DM and obesity and it is recommended that improving quality of fats in diet (more MUFAs and omega 3 PUFAs) would be beneficial in T2DM.[134,135]

Repeated heating/frying or reusing of oils at high temperature, which is a common practice in India should be avoided as it, induces chemical changes that increases the amounts of harmful TFAs, which greatly elevate the risk of CV complications in T2DM patients.[136,137]

Fibre and diabetes mellitus

Increasing the intake of dietary fibres is known to have a favourable effect on the overall metabolic health. Fibre-rich foods contain complex carbohydrates that are resistant to digestion and thereby reduce glucose absorption and insulin secretion.[79,138,139]

In overweight or obese patients with T2DM, a low glycaemic-index, high-fibre diet significantly (p<0.001) reduces glucose and insulin area under the curve compared with high-glycaemic index, high carbohydrate diets. The favourable effects on postprandial glucose and insulinemia were sustained through an entire day.[140]

Consumption of high-carbohydrate, low-GI diets that contain high proportions of dietary fibres also mitigate the risk of increase in serum triglyceride levels which is a common consequence of high-carbohydrate diet.[99]

Intake of both soluble and insoluble fibres have been associated with increased post-meal satiety and decrease in consequent hunger episodes.[141]

In randomized, cross-over study in 56 healthy Indian participants, consumption of flatbreads with addition of fibrous flour such as chickpea (15%) and guar gum (3% or 4%) to wheat flour significantly reduced postprandial glucose (p<0.01) and postprandial insulin (p<0.0001) when compared with flatbreads made from control flour (100% wheat flour).[113]

In a dietary assessment study in urban Asian Indians with T2DM, low consumption of dietary fibres (<29 g/day) was associated with higher prevalence of hypercholesterolemia (p=0.01) and higher LDL (p=0.001) than individuals with greater median intake of fibres.[142]

In a randomized study, daily consumption of 3 g of soluble fibre from 70 g of oats in form of porridge or upma for 28 days in mildly hypercholesterolaemic Asian Indians was associated with significant reduction in serum cholesterol (p<0.02) and LDL (p<0.04) versus control group (routine diet).[114]

From a meta-analysis of 17 prospective cohort studies, an inverse relation was observed between dietary intake and risk of T2DM based on which it was recommended that intake of 25 g/day total dietary fibre may T2DM.[143]

Physical activity

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Long Form and accelerometer can be used to measure and monitor the intensity of physical activity.[144]

Physical inactivity is regarded as a major risk factor for T2DM and evidence suggests that adequate physical activity may reduce the risk by up to 27%.[110,145]

Structured exercises have found to significantly reduce (p<0.001) post interventional HbA1c levels versus control group and this effect was independent of body weight.[146]

In the Indian Diabetes Prevention Program report, lifestyle modification that included a minimum of 30 min/day of physical labour, exercise, or brisk walking showed significant relative risk reductions for T2DM either alone (28.5%; p=0.018) or in combination with metformin (28.2%; p=0.022) versus the control group.[65]

In a cross-sectional comparative study, South Asians were found to need an additional 10-15 min/day of moderate-intensity physical activity more than the prescribed 150 min/week to achieve the same cardio-metabolic benefits as the European adults.[147]

Resistance training either alone or in combination with aerobic exercises or walking has also shown to significantly improve risk factors of T2DM such as waist circumference, abdominal adiposity, HDL levels etc.[148,149,150]

Based on all available evidence, the ADA and IDF recommend a total of at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per week that can be a combination of aerobic activities (such as walking or jogging) or resistance training.[151]

For Asian Indians who are predisposed to develop T2DM or CV risks, an additional 60 min of physical activity each day is recommended, although there is limited data to support this recommendation.[152]

Behavioural lifestyle intervention

BLI involves patient counselling for strategies such as tailoring goals, self-monitoring, stimulus control etc. that would help motivate patients to integrate the lifestyle management measures into their day-to-day life and identify and manage potential lapses.[153]

BLI approaches have shown to improve adherence to lifestyle changes and achieve more sustained effects.[154]

In patients with T2DM implementation of a six-month BLI program was reported to significantly reduce HbA1c levels from baseline at 3 months (–1.56 ± 1.81, p<0.05) and 6 months (−1.17±2.11, p<0.05). The BLI used cognitive behaviour therapy that mainly involved monitoring of carbohydrate intake (using diet charts) and setting targets for weight loss and physical activity across of 8 sessions (4 face-to-face and 4 telephone sessions) administered by clinical dietitians.[155]

BLI using smartphone or paper-based self-monitoring of patient behaviours on weight loss and glycaemic control (based on Look AHEAD study) in overweight or obese adults with T2DM showed significant improvements in HbA1c (p=0.01) at 6 months and meaningful weight loss that was not significant.[156]

A systematic review of randomized studies evaluating lifestyle-based interventions for T2DM found that robust behavioural strategies were essential for successful implementation of such prevention programs. This study reviewed the Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme that included individual patient counselling and goal setting for diet and exercise.[65,157]

TREATMENT 2: ORAL ANTIDIABETIC AGENTS

RECOMMENDATIONS

| Recommended Care |

|---|

| General Principles |

| • Metformin should be initiated in combination with lifestyle interventions at the time of diagnosis. |

| ▫ Maintain support for lifestyle measures throughout |

| ‣ Consider each initiation or dose increase of OADs as a trial, monitoring the response through glucose monitoring (FPG, PPG, self-monitoring of blood glucose [SMBG] or HbA1c) every 2-3 months. |

| ▫ Consider CV/heart failure risk, renal/hepatic (NASH) risk while deciding therapy |

| ▫ Patient-centric approach: consider cost and benefit risk ratio when choosing OADs |

| ▫ Customise therapy focusing on individualised target HbA1c for each patient based on: age, duration of diabetes, comorbidities, cost of therapy, hypoglycaemia risk, weight gain, durability |

| ▫ Consider initiating combination therapy if the HbA1c >1.5 above the targetInitial Therapy |

| ▫ Metformin should be initiated in combination with lifestyle interventions at the time of diagnosis unless contra-indicated or not tolerated. |

| ‣ If eGFRis between 45-30 mL/min/1.73m2: reduce dose of metformin by 50%; stop metformin if eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2. Closely monitor renal function every 3 months |

| ▫ Other options: sulfonylurea (or glinides), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors, or AGIs can be used initially for cases where metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated |

| ▫ In some cases, dual therapy may be indicated initially if it is considered unlikely that single agent therapy will achieve glucose targets |

| • Dualtherapy: Patient-centric approach |

| ▫ If glucose control targets are not achieved: Add sulfonylurea or thiazolidinediones (TZDs) or sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2) inhibitor, or DPP-4 inhibitor, or AGI |

| ▫ Individualise patient care based on comorbidities |

| • Tripletherapy: Patient-centric approach |

| ▫ If glucose targets are not achieved with two agents: start third oral agent-AGI, DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT2 inhibitor, or TZDs (depending on second-line agent used) or start insulin or glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists |

| • Intensification of therapy: Patients not achieving glycemic targets on 3 oral agents |

| ▫ Consider GLP-1 agonists or insulin if glucose targets are not achieved with OADs |

| ▫ Exceptionally, addition of fourth agent may be considered. |

| • In the presence of IR, addition of TZDs may be considered |

| • For patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), heart failure, diabetic kidney disease (DKD) or in need of weight reduction consider using SGLT2 inhibitors |

| • If postprandial hypoglycaemia is the issue AGI, glinides or SGLT2 inhibitors may be considered |

| • In elderly patients with increased risk of hypoglycaemia, use a DPP-4 inhibitor as an alternative to sulfonylurea |

| Limited Care |

|---|

| • The principles are same as for recommended care along with considerations for cost and availability of generic therapies. In resource constrained situations, sulfonylurea or metformin or TZDs may be used. |

| • Newer sulfonylureas have benefit of low cost and reduced hypoglycaemia (than older OADs); comparable CV safety with DPP4i may be considered. TZDs have established CV safety and may be considered as add on to metformin. |

BACKGROUND

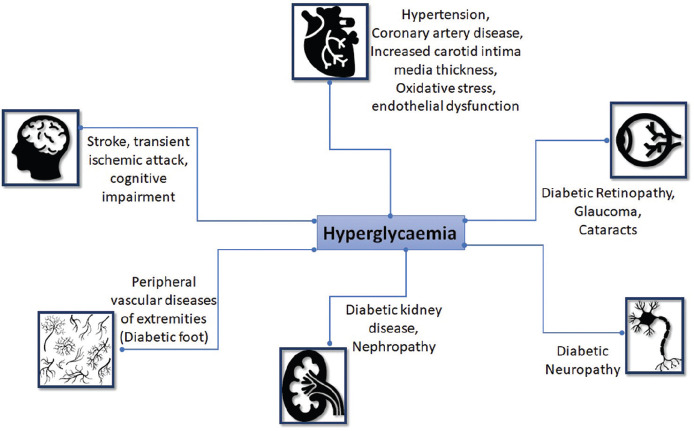

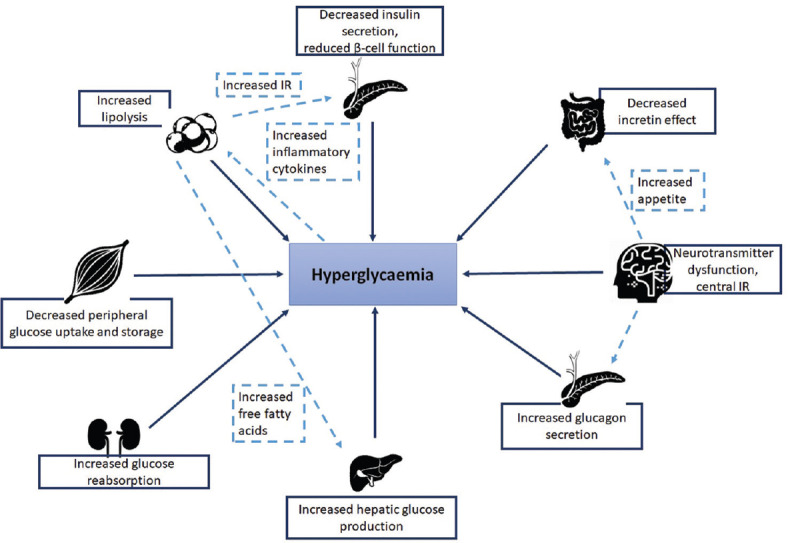

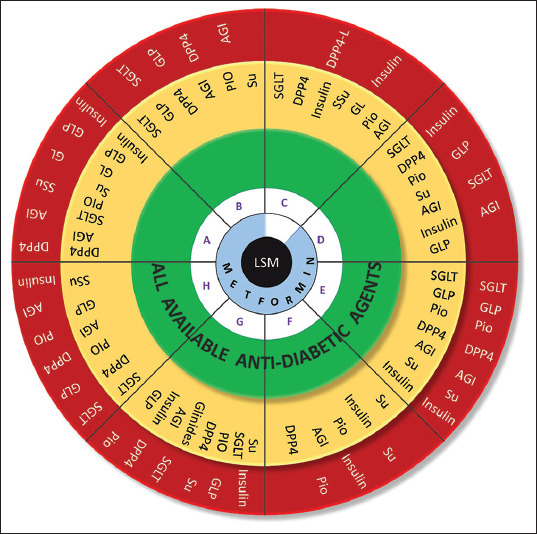

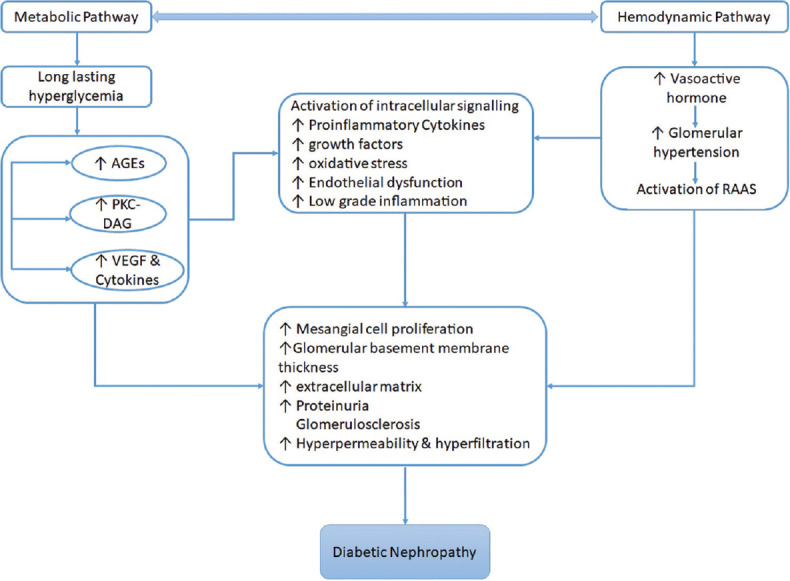

T2DM occurs due to a complex interaction between genetic inheritance and risk factors such as obesity and sedentary lifestyle.[158] Diminished insulin secretion, incretin deficiency/resistance, upregulated lipolysis, increased glucose reabsorption from kidney, along with downregulated glucose uptake, neurotransmitter dysfunction, increased hepatic glucose production, and glucagon secretion are the reported metabolic derailments that contribute to hyperglycaemia and T2DM [Figure 2].[159] Among Indians, high familial aggregation, central obesity, insulin resistance, and life style changes due to rapid urbanization are the primary causes of T2DM.[160] Greater degree of insulin resistance paired with higher central adiposity compared to Caucasians is a characteristic feature of T2DM in Asian Indians.[161,162]

Figure 2.

Metabolic derailments in T2DM.[159]

IR: Insulin resistance; T2DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Treatment options for T2DM have been developed in parallel to the increased understanding of underlying pathophysiological defects in T2DM. A patient-centric and evidence-based approach that may take into account all the metabolic derailments accompanying T2DM, is now gaining impetus. Therefore, treatments that target factors beyond glycaemic control, such cardiovascular risks, weight management, along with improvements in quality of life have been introduced.[163] Several guidelines/recommendations provide treatment algorithms on ways in which glucose-lowering agents can be used either alone or in combination. Ideally, treatment decisions should be directed based on glycaemic efficacy and safety profiles, along with impact on weight and hypoglycaemia risk, comorbidities, route of administration, patient preference, as well as treatment costs.[164] Here the guideline is based on clinical evidences and provides overview on available OADs. The treatment algorithms in this chapter attempt to provide practical recommendations for optimal management of T2DM in Asian Indians.

CONSIDERATIONS

The decision on choice of OAD therapy in T2DM patients is based on the cost, safety, and efficacy and comorbidities that were reviewed in Asian Indian context.

RATIONALE AND EVIDENCE

Oral antidiabetic agents Table 2

Table 2.

Profile of available oral antidiabetic agents

| Effect on weight | CV effects | Significant side effects | Summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Biguanides Metformin |

Weight loss/neutral | Beneficial CV effects, reduces LDL-C and increases HDL-C; however, reports of caution indicated particularly in older patients with CHF |

Lactic acidosis | First-line drug therapy of choice for T2DM Acceptable CV safety profile |

|

SU Gliclazide, glimepiride, glipizide, glyburide, glibenclamide |

Gain | Increased risk of CV mortality and all-cause mortality | Hypoglycaemia, weight gain | Second-line drug therapy |

|

TZDs Rosiglitazone, pioglitazone |

Gain | Increased risk of MI, CHF, Increased levels of LDL-C, triglycerides | Weight gain, CV outcomes | To be avoided in patients with or at risk for heart failure |

|

DPP-4 inhibitors Sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin, tenaligliptin |

Weight neutral | Neutral effect on CV outcomes | GI effects, pancreatitis | Caution to be exercised while prescribed in patients with heart failure |

|

AGIs Acarbose, miglitol, voglibose |

Weight neutral | Neutral effect on CV outcomes | Flatulence, diarrhoea | Low risk of hypoglycaemia. CV safety to be evaluated |

|

SGLT2i Dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, empagliflozin, remogliflozin |

Weight loss | Beneficial CV effects | Mycotic infections of the genital tract and osmotic diuresis | Favoured as the second-line agent of choice in T2DM patients with a history of CVD |

AGIs: Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, CHF: Congestive heart failure, CV: Cardiovascular, HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein-cholestrol, DPP-4: Dipeptidyl peptidase, GI: Gastrointestinal, MI: Myocardial infarction, LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein-cholestrol, SGLT2i: Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors, DM: Diabetes mellitus T2DM: Type 2 DM, TZDs: Thiazolidenediones, SU: Sulfonylureas, CVD: CV disease

Biguanides

Metformin remains the first choice in the management of patients with T2DM.[165] Metformin is efficacious in managing hyperglycaemia, increasing insulin sensitivity, along with beneficial effects in reducing cardiovascular and hypoglycaemia risk, improving macrovascular outcomes, and lowering mortality rates in T2DM.[166] Metformin is a complex drug that exerts its action via multiple sites and several molecular mechanisms. Metformin is known to down regulate the hepatic glucose production, act on the gut to increase glucose utilisation, enhance insulin, increase GLP-1 and alter the microbiome.[167] TheUK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group study in over weight T2DM patients suggested that intensive glucose control that metformin lowered the risk of diabetes-related endpoints, diabetes-related deaths, and all-cause mortality in overweight T2DM patients, compared to insulin and sulphonylureas.[168] A 10-year follow-up study of the UKPDS reported continued benefit following intensive glucose control with metformin in terms of reduced diabetes-related endpoints, diabetes-related deaths, and all-cause mortality.[169] Along with substantial improvements in hyperglycaemia, metformin improved endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, lipid profiles, and fat redistribution.[170] Owing to the concerns of lactic acidosis and gastrointestinal effects (nausea, vomiting diarrhoea and flatulence) metformin should be used cautiously in patients with renal insufficiency or elderly patients. In patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 metformin can be used, but should not be initiated in patients with an eGFR of 30 to 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 and must be contraindicated in patients with an eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2.[164]

Sulfonylureas

Sulfonylureas are second line agents used in patients with T2DM patients who are not obese. Sulfonylureas are insulin secretagogues that act on the ATP-sensitive K+ channels on the β cells and stimulate endogenous insulin secretion.[171] As a single therapy, sulfonylureas are efficacious in lowering fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c. However, concerns of modest weight gain and moderate to severe hypoglycaemia and cardiovascular risk limit their clinical benefits.[172] As a consequence of closure of cardiac KATP channel, the use of sulfonylureas have also been related to adverse CV effects due to impaired hypoxic coronary vasodilation during increased oxygen demands such as acute myocardial ischemia.[173] The use of glibenclamide was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with diabetes and acute myocardial infarction.[174] Adverse cardiovascular outcomes with sulfonylureas in some observational studies have raised concerns, although findings from recent meta-analysis that included several RCTs reported that sulfonylureas when added to metformin were not associated with all-cause mortality and CV mortality.[175] New generation sulfonylureas have demonstrated superior safety, mainly due to reducing hypoglycaemia, and improved cardiac profile. Sulfonylureas particularly gliclazide modified release (MR) and glimepiride have a lower risk of hypoglycaemia and are preferred in south Asian T2DM patients.[176] Caution must be exercised while prescribing sulfonylureas for patients at a high risk of hypoglycaemia, older patients and patients with CKD.[177] Shorter-acting secretagogues, the meglitinides (or glinides), also stimulate insulin release through similar mechanisms and may be associated with comparatively less hypoglycaemia but they require more frequent dosing. Moreover, modern sulfonylureas exhibit more reductions of HbA1c than glinides.[178]

Thiazolidinediones

Pioglitazone and rosiglitazone are peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ activators that improve insulin sensitivity by increasing insulin-mediated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, suppressing hepatic glucose output, and improving the secretory response of insulin in pancreatic β-cells.[179] The risk of hypoglycaemia is negligible and TZDs may be more durable in their effectiveness than sulfonylureas.[180] TZDs have been constantly under the authority scrutiny for their cardiovascular safety. A meta-analysis considering data from 42 trials and 27,847 patients indicated that treatment with rosiglitazone was associated with an increase in the odds of MI (odds ratio 1.43, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.98, p=0.03) and a nonsignificant increase in the odds of cardiovascular death (odds ratio 1.64, 95% CI 0.98: 2.74, p=0.06) compared with a control group (active comparator or placebo).[181] The RECORD study evaluated the effect of rosiglitazone (plus metformin or sulfonylurea) in lowering the combined end point of hospitalization or cardiovascular death versus metformin plus sulfonylurea. Although, rosiglitazone did not increase the risk of overall cardiovascular morbidity or mortality it increased the risks of heart failures causing admission to hospital or death when compared to the active controls (HR: 2.10, 95% CI, 1.35:3.27).[182] Conversely, pioglitazone is known to exert pleotropic effects on cardiovascular event; pioglitazone improves endothelial dysfunction, lowers hypertension, improves dyslipidaemia, and lowers circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines and prothrombotic factors.[183] In the PROactive study, pioglitazone lowered the composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, and stroke in T2DM patients with at risk of macrovascular events along with improvements in HbA1c, triglycerides, LDL, and HDL levels. However, rate of heart failure was increased.[184] TZDs have demonstrated beneficial effects in attenuating dyslipidaemia commonly observed in patients with chronic T2DM. Rosiglitazone treatment with metformin showed an HDL increase of 13.3%, LDL increase of 18.6% and a neutral effect on total cholesterol, following 26 weeks of treatment.[185] Furthermore, the IRIS trial was among the 1st studies to document the CV benefits of TZDs in non-diabetic individuals. Pioglitazone improved CV outcomes (recurrent stroke and MI) and prevented the development of T2DM in insulin-resistant, non-diabetic patients with cerebrovascular disease.[186] In a recent post hoc study of the IRIS trial, conducted in prediabetic population, pioglitazone effectively lowered the risk of stroke, MI, acute coronary syndrome, and hospitalization for heart failure.[187] Pioglitazone had been linked with a possible increased risk of bladder cancer, possibly in a dose-and time-dependent manner.[188,189] However data from a retrospective study in India involving 2222 (pioglitazone users, n = 1111; pioglitazone non-users, n = 1111) T2DM patients found no evidence of bladder cancer in any of the group, including patients with age >60 years, duration of diabetes >10 years, and uncontrolled diabetes.[190] Recognized side effects of TZDs include weight gain (3–5 kg), fluid retention leading to oedema, and/or heart failure in predisposed individuals and patients with increased risk of bone fractures.[180,184,190]

Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors

Vildagliptin, saxagliptin, gemigliptin, evogliptin sitagliptin, teneligliptin, and linagliptin are incretin enhancers; they enhance circulating concentrations of active GLP-1 and gastric intestinal polypeptide (GIP).[191] These incretins stimulates insulin secretion, suppresses glucagon synthesis, lower hepatic gluconeogenesis, and slow gastric emptying. Their major effect is the regulation of insulin and glucagon secretion; they are weight neutral.[192] DPP-4 inhibitors are efficient in improving glycaemia both as monotherapy and as add-on to metformin, sulfonylurea and TZDs in patients with inadequate glycaemic control. A reduction in HbA1c levels from baseline of 8.1% was observed with sitagliptin monotherapy (100 mg:-0.5%, 200 mg:-0.6%) in 521 patients treated for 18 weeks. Additionally, homeostasis model assessment of beta cell function index, fasting proinsulin-insulin ratio which are the markers of insulin secretion, and beta cell function were also improved significantly.[193] The overall incidence of adverse events with sitagliptin is comparable to other OADs when used as monotherapy or as add-on to existing OADs.[194] Adverse effects (AEs) such as constipation, nasopharyngitis, urinary tract infection, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, and dizziness are the commonly reported AEs with the use of these agents.[195] Cardiovascular outcomes trial (CVOT) studies with DPP-4 inhibitors have shown that these agents are safe in patients with established CVD and those at increased risk of CVD except for increased risk of heart failure risk.[196] Results of the SAVOR-TIMI study and EXAMINE Study have reported higher rates of hospitalization for heart failure with saxagliptin and alogliptin, respectively.[197,198] Owing to the increased risk of hospitalization due to heart failure in patients with cardiovascular disease, the US FDA issued a warning, suggesting the associated risk to be a “class-effect” of the DPP-4 inhibitors and issued a warning for their use.[199] However, some landmark studies have been conducted to evaluate relationship between these drugs and the adverse effects. In the CARMELINA study, linagliptin demonstrated a long-term CV safety profile in patients with T2D, including those with CV and/or kidney disease and no increased risk of hospitalisation for heart failure versus placebo was reported.[200] The CAROLINA study was designed to evaluate the long-term CV safety profile of linagliptin versus glimepiride in patients with early T2D at increased CV risk. Recently released top line results highlight a non-inferiority between linagliptin versus glimepiride in time to first occurrence of CV death, non-fatal MI, or non-fatal stroke (3P-MACE) with a median follow-up of more than 6 years.[201]

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors

They provide insulin-independent glucose-lowering by blocking glucose reabsorption in the proximal renal tubule. The capacity of tubular cells to reabsorb glucose is reduced by SGLT2 inhibitors leading to increased urinary glucose excretion and consequently, correction of the hyperglycaemia.[202] Dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and remogliflozin are the 4 Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) approved agents used in patients with T2DM.[203,204] The EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial evaluated the non-inferior cardiovascular safety of empagliflozin in high-CV-risk T2D patients with an estimated glomerular filtration ate (eGFR) of at least 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Empagliflozin reduced the rate of new onset or worsening nephropathy, which were defined as new-onset microalbuminuria, doubling of creatinine, and eGFR ≤45 mL/min/1.73 m2, initiation of renal replacement therapy, and death due to renal disease (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.53, 0.70; p<0.0001).[205] A secondary analysis of CANTA-SU study confirmed the renoprotective effects of canagliflozin. The eGFR decline was significantly slower in patients receiving canagliflozin than in those receiving glimepiride (0.5 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year with 100 mg daily [95% CI: 0.0, 1.0] and 0.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year with 300 mg daily [95% CI: 0.4, 1.4], compared with glimepiride (3.3 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year [95% CI: 2.8, 3.8]).[206] The CANVAS Program integrated data from two trials involving a total of 10,142 participants with type 2 diabetes and high cardiovascular risk. Treatment with canagliflozin showed a possible benefit with respect to the progression of albuminuria (HR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.67, 0.79) and the composite outcome of a sustained 40% reduction in the estimated glomerular filtration rate, the need for renal-replacement therapy, or death from renal causes (HR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.47, 0.77).[207] Canagliflozin in combination with metformin significantly improved glycaemic control in patients with T2DM and significant weight loss along with low incidence of hypoglycaemia have been reported.[208] A recent meta-analysis concluded that SGLT2 inhibitors, as a class, significantly reduce 24-h ambulatory blood pressure further substantiating their favourable cardiovascular profile.[209] The most common AEs involving this class are genital mycotic infections, which are believed to be mild and respond favourably to anti-fungal therapy.[210,211,212,213,214]

Alpha glucosidase inhibitors