Abstract

Aim and objectives

To review the literature on Nordic women's lived experiences and quality of life (QoL) after gynaecological cancer treatment.

Background

While incidence and survival are increasing in all groups of gynaecological cancers in the Nordic countries, inpatient hospitalisation has become shorter in relation to treatment. This has increased the need for follow‐up and rehabilitation.

Design

Integrative literature review using the Equator PRISMA guidelines.

Methods

The review was selected, allowing inclusion of both experimental and nonexperimental research. The search included peer‐reviewed articles published 1995–2017. To frame the search strategy, we applied the concept of rehabilitation, which holds a holistic perspective on health.

Results

Fifty‐five articles were included and were contextualised within three themes. Physical well-being in a changed body encompasses bodily changes comprising menopausal symptoms, a changed sexual life, complications in bowels, urinary tract, lymphoedema and pain, bodily‐based preparedness and fear of recurrence. Mental well-being as a woman deals with questioned womanliness, the experience of revitalised values in life, and challenges of how to come to terms with oneself after cancer treatment. Psychosocial well-being and interaction deals with the importance of having a partner or close person in the process of coming to terms with oneself after cancer. Furthermore, the women needed conversations with health professionals around the process of coping with changes and late effects, including intimate and sensitive issues.

Conclusion

Years after gynaecological cancer, women have to deal with fundamental changes and challenges concerning their physical, mental and psychosocial well‐being. Future research should focus on how follow‐up programmes can be organised to target the multidimensional aspects of women's QoL. Research collaboration across Nordic countries on rehabilitation needs and intervention is timely and welcomed.

Relevance to clinical practice

To ensure that all aspects of cancer rehabilitation are being addressed, we suggest that the individual woman is offered an active role in her follow‐up.

Keywords: follow‐up, gynaecological cancer, integrative review, lived experiences, person‐centred, quality of life, rehabilitation, survivors

What this paper contributes to the wider global clinical community

This review offers a comprehensive overview of Nordic women’s lived experiences and QoL after gynaecological cancer.

The findings show that women’s lived experiences and QoL after gynaecological cancer involve aspects of physical, psychological and psycho‐social well‐being.

Rehabilitation and follow‐up should focus on a person‐centered approach where multidimensional aspects of women’s QoL are addressed.

1. INTRODUCTION

There are 25 million inhabitants in the Nordic countries, 130 000 cancer incidents are reported yearly, and almost a million people live as cancer survivors (Engholm et al., 2014). Gynaecological cancer accounts for more than 12% of all female cancers in the Nordic countries, the main types being corpus, ovarian and cervical cancer. Corpus cancer is the most common of gynaecological cancers and the fourth most common of female cancers (Klint et al., 2010). Both incidence and survival are increasing in all groups of gynaecological cancers in the Nordic countries, although the prognosis is still poor for women diagnosed with ovarian cancer (Klint et al., 2010). Increased survival is primarily due to better diagnostic tools and treatment modalities. Simultaneously, shorter inpatient hospitalisation has increased the importance of rehabilitation. An editorial by Dalton, Bidstrup, and Johansen (2011) points to a need for research in smaller patient groups concerning late effects and rehabilitation needs.

Several studies report that the follow‐up period holds significant challenges for the patients including physical, psychosocial and sexual problems and fear of recurrence (Chase, Monk, Wenzel, & Tewari, 2008; Sekse, Raaheim, Blaaka, & Gjengedal, 2010; Steele & Fitch, 2008). A study including 3,439 cancer patients showed that 60% had an unmet need in at least one area during their follow‐up, frequently concerning physical and emotional problems. These unmet needs were associated with a decrease in QoL (Hansen et al., 2013). Consequently, many cancer survivors do not regain their previous level of health and functioning, even though they are in regular contact with health care (Burkett & Cleeland, 2007; Harrington, Hansen, Moskowitz, & Todd, 2010; Hewitt & Ganz, 2006). This also applies to gynaecological cancer survivors who struggle with a challenging life phase where they must learn to live with the experiences and possible side effects from the gynaecological cancer disease and treatment (Burkett & Cleeland, 2007; Feuerstein, 2007; Harrington et al., 2010).

Women in the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden) are geographically, historically, culturally and politically related (http://www.ancr.nu). They share similar living conditions as the Nordic economic and social welfare model ensures certain goods, for example, free access to education, health care and cancer prevention. Despite variation in the follow‐up programmes after gynaecological cancer, both within and across the Nordic countries, routine follow‐up programmes have mainly consisted of 5 years of clinical consultations. The primary aim has been to detect recurrence as early as possible, thus increasing the likelihood of survival. However, studies (Kew & Cruickshank, 2006; Kew, Roberts, & Cruickshank, 2005; Lajer et al., 2010; Leeson et al., 2017; Vistad, Moy, Salvesen, & Liavaag, 2011) reveal little evidence supporting this assumption. Lajer et al. (2010) and Vistad, Moy et al. (2011) did not find any positive effect on survival of such follow‐up. Instead, alternative models of follow‐up were suggested, where late effects, QoL and satisfaction with care were integrated. Consequently, a change of focus from recurrence to QoL has been requested in several of the Nordic countries (Lajer et al., 2010; Vistad, Moy et al., 2011).

Taken together, for all female genital cancers, incidence and survival rates are increasing in the Nordic countries. Inpatient hospitalisation has become shorter, but the follow‐ups, with their focus on recurrence, do not meet the patients’ needs and are being criticised across the countries. All these factors point to a need for investigating follow‐up and rehabilitation in a larger group of gynaecological cancer survivors sharing the same living conditions. Thus, our aim was to review Nordic women's lived experiences and QoL after gynaecological cancer treatment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Problem identification

It was assumed that integration of empirical evidence, derived from both quantitative and qualitative empirical studies, could capture the complexity of knowledge and information regarding women's lived experiences and QoL after gynaecological cancer treatment. We therefore used the systematic method of reviewing and integrating literature described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) and guided by Equator PRISMA framework (see Supporting Information). Whittemore and Knafl (2005) propose a five‐stage review approach based on the framework of Cooper & Cooper, (1998): problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation. As Kirkevold (1997) advocates that integrative reviews should have an explicit theoretical perspective, we elaborated on the concept of cancer rehabilitation to contextualise the findings.

2.2. Rehabilitation as overall framework

Cancer and cancer treatment affects a patient's life on many levels and dimensions, and several of the models designed to capture survivorship issues illustrate the major areas in life that cancer may impact. In a caring science perspective, gynaecological cancer follow‐up should address patient needs in a comprehensive holistic approach, grounded in well‐thought‐out descriptions promoting quality of life and health in all its dimensions. In the integrative review, it is mandatory to have an explicit theoretical starting point to illuminate the phenomenon under study. As the theoretical perspective of rehabilitation encompasses a comprehensive approach to physical, mental and psychosocial health, this was chosen to frame the literature search. According to the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO, 2001), rehabilitation is defined as a goal‐oriented, cooperative process involving an individual, her relatives and professionals over a specific time period. The concept provides a theoretical framework for understanding health in a broad sense, where the individual woman is seen as physical body, individual person and participant.

2.3. Literature search

The search strategy was developed in close collaboration with MØ, a research librarian. It was first performed in 2015 and repeated in 2017. Inclusion criteria: peer‐reviewed articles from the Nordic countries concerning rehabilitation in all types and treatments of gynaecological cancer, written in Nordic or English language and available in full text. Participants should be minimum 18 years old. Exclusion criteria: studies older than 20 years including patients in active treatment or with known recurrence; and studies solely concerned with patients treated for borderline tumours, or relatives’ views and experiences.

As illustrated in Table 1, the block search strategy used “population,” “exposure” and “outcome” as facets. “Population” was designed to capture all kinds of gynaecological cancer. “Exposure” consisted of a range of different terms that described life after cancer treatment. The concepts in these two facets were searched as both free‐text and index terms. “Exposure” comprised different concepts of rehabilitation, nursing, care and patient education after gynaecological cancer treatment. As the concepts in this facet are general, they were searched only as index terms.

Table 1.

Overview of the block search in PubMed in 2015 and 2017. The search terms of each facet were combined with a Boolean OR and subsequently a Boolean AND. Search terms ending with an s in brackets indicate that these given terms are searched in the singular as well as in the plural

| Population | AND | Exposure | AND | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | OR | OR | ||||

| Free‐text terms | MeSH terms | MeSH | Free‐text terms | MeSH | ||

|

Gynecological cancer(s) Gynaecological cancer(s) |

Genital neoplasms, female | Rehabilitation nursing | Late effect(s) | |||

|

Vulva cancer Vulvar cancer Vulval cancer |

Vulvar neoplasms | Perioperative nursing | Symptoms | |||

| Ovarian cancer | Ovarian neoplasms | Self care | Side effect(s) | |||

| Uterine cancer |

Uterine Neoplasms |

Rehabilitation | Adverse effect(s) | |||

| Endometrial cancer | Endometrial neoplasms | Postoperative care |

Lymph oedema(s) Lymphoedema(s) Lymphedema(s) (lymph AND edema) |

Lymphedema OR (lymph AND edema) | ||

|

Cervical cancer Cervix cancer |

Uterine cervical neoplasms | Patient education as topic | Pain | Pain | ||

| Corpus cancer | — | Patient care team | Fatigue | Fatigue | ||

| Nursing care | Sexuality | Sexuality | ||||

| Health education | Needs | |||||

| Patient care |

Well‐being Well‐being |

|||||

| Comprehensive health care | Psychosocial need(s) | |||||

| Unmet need(s) | ||||||

| Distress | ||||||

| Depression(s) |

Depression Depressive disorder |

|||||

| Relations | Interpersonal relations | |||||

| Fear of recurrence | ||||||

| Experience | ||||||

| Quality of life (QoL) | Quality of life | |||||

| Anxiety |

Anxiety Anxiety disorders |

|||||

| Hope | Hope | |||||

| Existential | Existentialism | |||||

| Spiritual | Spirituality | |||||

|

Post traumatic growth Posttraumatic growth |

||||||

| Return to work | Return to work | |||||

| Health promotion | Health promotion | |||||

|

Daily life functioning Activities of daily living Activities of daily life |

Activities of daily living | |||||

|

Socio economic Socioeconomic |

Socioeconomic factors | |||||

| Work related issues | ||||||

Search string for PubMed: (((((((((((((((((gynecological cancer[All Fields] OR gynecological cancerology[All Fields] OR gynecological cancers[All Fields]) OR (gynaecological cancer[All Fields] OR gynaecological cancers[All Fields])) OR (“vulva cancer”[All Fields] OR “vulvar cancer”[All Fields] OR “vulval cancer”[All Fields])) OR “Vulvar Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR “ovarian cancer”[All Fields]) OR “Ovarian Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR “uterine cancer”[All Fields]) OR “Uterine Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR “endometrial cancer”[All Fields]) OR “Endometrial Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR (“Cervical cancer”[All Fields] OR “cervix cancer”[All Fields])) OR “Uterine Cervical Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR “Corpus cancer”[All Fields]) OR “Genital Neoplasms, Female”[Mesh]) AND ((((((((((“Rehabilitation Nursing”[Mesh] OR “Perioperative Nursing”[Mesh]) OR “Self Care”[Mesh]) OR “Rehabilitation”[Mesh]) OR “Postoperative Care”[Mesh]) OR “Patient Education as Topic”[Mesh]) OR “Patient Care Team”[Mesh]) OR “Nursing Care”[Mesh]) OR “Health Education”[Mesh]) OR “Patient Care”[Mesh]) OR “Comprehensive Health Care”[Mesh])) AND ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((“late effect”[All Fields] OR “late effects”[All Fields]) OR “symptoms”[All Fields]) OR (“side effects”[All Fields] OR “side effect”[All Fields])) OR (“lymph oedema”[All Fields] OR ((“lymph”[MeSH Terms] OR “lymph”[All Fields]) AND (“edema”[MeSH Terms] OR “edema”[All Fields] OR “oedemas”[All Fields])) OR “lymphoedema”[All Fields] OR “lymphoedemas”[All Fields] OR “lymphedema”[All Fields] OR “lymphedemas”[All Fields])) OR “Lymphedema”[Mesh]) OR “pain”[All Fields]) OR “Pain”[Mesh]) OR “fatigue”[All Fields]) OR “Fatigue”[Mesh]) OR “sexuality”[All Fields]) OR “Sexuality”[Mesh]) OR (“well‐being”[All Fields] OR “well‐being”[All Fields])) OR (“psychosocial needs”[All Fields] OR “psychosocial need”[All Fields])) OR (“unmet needs”[All Fields] OR “unmet need”[All Fields])) OR “distress”[All Fields]) OR (“depression”[All Fields] OR “depressions”[All Fields])) OR (“Depression”[Mesh] OR “Depressive Disorder”[Mesh])) OR “relations”[All Fields]) OR “Interprofessional Relations”[Mesh]) OR “fear of recurrence”[All Fields]) OR “experience”[All Fields]) OR (“quality of life”[All Fields] OR “qol”[All Fields])) OR “Quality of Life”[Mesh]) OR “anxiety”[All Fields]) OR (“Anxiety”[Mesh] OR “Anxiety Disorders”[Mesh])) OR “hope”[All Fields]) OR “Hope”[Mesh]) OR “existential”[All Fields]) OR “Existentialism”[Mesh]) OR “spiritual”[All Fields]) OR “Spirituality”[Mesh]) OR (“post traumatic growth”[All Fields] OR “posttraumatic growth”[All Fields])) OR “return to work”[All Fields]) OR “Return to Work”[Mesh]) OR “health promotion”[All Fields]) OR “Health Promotion”[Mesh]) OR (“daily life functioning”[All Fields] OR “activities of daily living”[All Fields] OR “activities of daily life”[All Fields])) OR “daily life functioning”[All Fields]) OR “Activities of Daily Living”[Mesh]) OR (“socio economic”[All Fields] OR “socioeconomic”[All Fields])) OR “socio economic”[All Fields]) OR “Socioeconomic Factors”[Mesh]) OR “work related issues”[All Fields]) OR (((“adverse effect”[All Fields]) OR “adverse effects”[All Fields]))) AND ((“1995/01/01”[PDAT] : “2015/12/31”[PDAT]) AND (English[lang] OR Norwegian[lang] OR Swedish[lang] OR Danish[lang])))) NOT (((((((“Oceania”[Mesh]) OR “Australia”[Mesh]) OR “Americas”[Mesh]) OR “Africa”[Mesh]) OR “Asia”[Mesh])) OR “Europe, Eastern”[Mesh]).

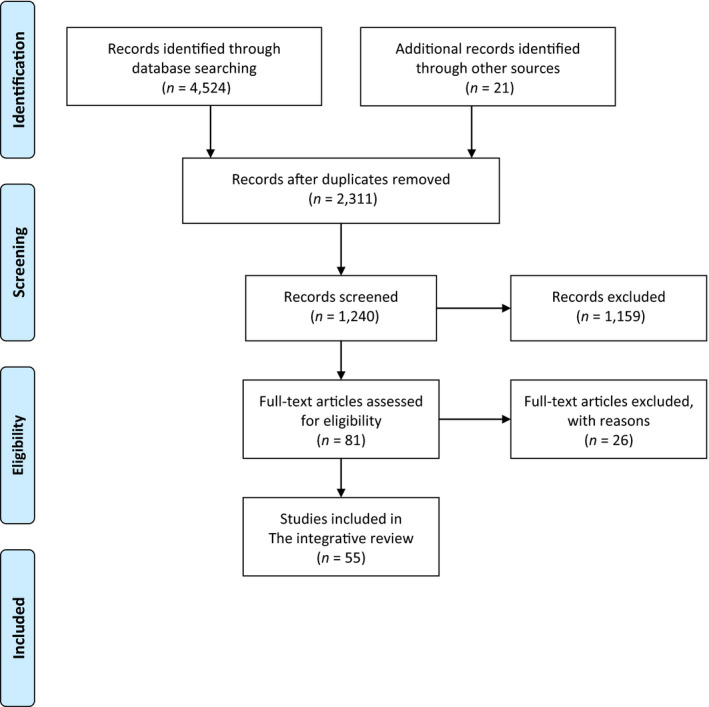

Initially, the search strategy was developed for PubMed and then adapted to fit the syntax and indexing of CINAHL, PsycINFO and Embase. First, the researchers found search terms for PubMed. Second, the search terms were tested by the librarian. Third, the set of search terms and the search strategy as a whole were revised (Table 1). Identifying all concepts for the facets “exposure” and “outcome” constituted a challenge. To minimise the biases this might lead to, researchers within the field were invited to suggest references, and a hand search was also performed. The outcome of the literature search and selection of articles was performed according to the PRISMA statement checklist and concurrently displayed in a flow diagram (Figure 1; Liberati et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of peer‐reviewed articles [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.4. Data evaluation stage

Various tools were used to determine the validity of the studies, depending on whether the approach was quantitative, qualitative or interventional.

Thirty‐five quantitative studies were reviewed, all cohort studies published between 1997–2017. Time to follow‐up ranged from immediately postsurgery to 19 years following treatment. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (Wells et al., 2009) was used to evaluate the quantitative studies (Table 3). The scale measures the quality of cohort studies according to eight assessment criteria organised into three categories: selection, comparability and outcome. The highest possible quality score resulting from this scale is nine stars. The majority of the 35 studies received a high score of eight stars. Most studies received stars in the “selection” category for having demonstrated that the outcome of interest was not present at the beginning of the study, shown representative of the exposed cohort and reported ascertainment of exposure. In the “comparability” category, most studies received only one of two possible stars. The number of stars awarded in the “outcome” category was limited due to a high frequency of self‐reported outcome data. Nonetheless, follow‐up periods were typically stated and long enough to observe the occurrence of the outcome.

Table 3.

Overview of quantitative studies

| References | Type of study | Aim | Type of tumour | Treatment | Time since treatment | No. of patients | Controls | Outcomes | Instrument | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carlsson and Strang (1996) | Cross‐sectional | To evaluate potential interest in an educational and supportive group as well as to rank the most important issues. Another aim was to rank the most important issues | Gyn ca survivors |

Group I newly diagnosed Group II 2–5 post‐treatment |

62 33 |

Self‐reported demographic potential interest in an educational and supportive group | Study‐specific |

Answering rate: 80% Younger individuals, couples and people with high education were the most interested Highest ranked issues were cancer and treatment, side effects, pain and psychological reactions. Interest in sexual issues was highest in group II Interest in supportive care was significantly higher than in comparable studies |

||

| Aass et al. (1997) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate the prevalence of anxiety and depression in cancer survivors | Gyn ca survivors | Various | 0.7 years | 163 | — | Prevalence of anxiety and depression | HADS, EORTC QLQ‐33, study‐specific |

Answering rate: 83% 19% reported anxiety, 12% depression |

| Bergmark et al. (1999) | Cross‐sectional | Prevalence of vaginal changes among women treated for cervical cancer | Cervix | Surgery, Radiotherapy | 4 years | 256 | Yes |

Self‐reported Sexual function |

Study‐specific |

Answering rate: 77% cases 72% controls Vaginal changes have negative sexual effect, insufficient lubrication for intercourse and short vagina |

| Bergmark et al. (2002) | Cross‐sectional | To what extent a specific symptom distresses them and the proportion of women who are distressed | Cervix | Surgery Radiotherapy | 4 years | 93/256 | Yes |

Self‐reported Distressful symptoms |

Study‐specific |

Answering rate: 77% cases 72% controls Dyspareunia and defecation urgency most distressful symptoms |

| Nesvold and Fosså (2002) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate whether survivors of cervical and vulvar cancer remember being counselled about lymphoedema postsurgery and the investigate the prevalence of lymphoedema among cervical cancer survivors | Cervix, vulvar | Surgery, radiotherapy | 1 year post‐treatment | 83 | — | Information concerning lymphoedema postsurgery, satisfaction concerning information | Study‐specific questionnaire |

Answering rate: 90% 30% had not received written nor oral information. 30% satisfied with info given. 20% had signs of lymphoedema of the lower limbs |

| Ahlberg et al. (2004) | Descriptive | To describe how patients diagnosed with uterine cancer describe fatigue, psychological distress, coping resources and QoL before treatment with RT | Uterine | Surgery | Postsurgery | 60 | — | Uterine ca patients describe fatigue, psychological distress, coping resources and QoL | MFI‐20, HADS, SOC QLQ C 30 |

Answering rate: 73% Low grade of fatigue and psychological distress. Global QoL high. Positive correlation general fatigue and anxiety and depression. Negative correlation fatigue and coping resources and global QoL |

| Bergmark et al. (2005) | Cross‐sectional | Long‐term effects of sexual abuse on well‐being, psychological symptoms and sexual dysfunction | Cervix | Surgery | 4 years | 256 | Yes |

Self‐reported Sexual abuse |

Study‐specific |

Answering rate: 77% cases 72% controls Answering rate: 77% cases 72% controls Sexual abuse, sexual dysfunction more common among cervical cancer survivors |

| Nord et al. (2005) | Cross‐sectional | General health status in long‐term cancer survivors, if they use healthcare services more often than controls | Cervix, ovarian | Various | 19 years | 153 | Yes | General health status, physical activity, lifestyle | HUNT 2 | Reported poorer health, more frequent contact with healthcare services, more often diarrhoea, and cerebrovascular episodes. Physically more inactive, more smokers |

| Bergmark et al. (2006) | Cross‐sectional | To document the prevalence of symptoms and decline in function after Wertheim‐Meigs procedure, the distress caused by these symptoms | Cervix | Surgery | 4 years | 93/256 | Yes | Self‐reported symptoms | Study‐specific |

Sexual abuse, sexual dysfunction more common among cervical cancer survivors 19% swollen legs/abdomen always, vaginal changes, bladder‐emptying difficulties and bowel dysfunction |

| Seibaek & Petersen, 2007 | Retrospective | To identify the frequency and extent of self‐reported problems concerning their perception of their body and of being cured | Cervix | Surgery | 299 and 91 | — | Self‐reported perception of body and subjective feeling of being cured and evaluate self‐reported health problems | Study‐specific (first round) SF‐36, SOC (second round) |

19% swollen legs/abdomen always, vaginal changes, bladder‐emptying difficulties and bowel dysfunction Answering rate: 75% 72% did not feel directly when answering the questionnaire 28% perceived feelings of illness.(first round) The women who consider themselves as cancer patients reported a general deterioration of their life situation, low score for general health, mental wellness, physical functioning (second round) |

|

| Vistad et al. (2007) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate the prevalence of chronic fatigue in cervical cancer survivors and to explore the difference between cervical cancer survivors with and without chronic fatigue concerning physical complaints, sexual dysfunction, anxiety and depression and QoL | Cervix | Radiotherapy, brachy | 7,9 years | 91 | Yes | Self‐reported prevalence of chronic fatigue | Fatigue questionnaire FQ, HADS, MOS, SF‐36, SAQ, LENT‐SOMA |

Answering rate: 62% 30% reported chronic fatigue compared to 13% among general population. Cervical cancer survivors had significantly lower QoL, higher levels of anxiety and depression and more physical impairments than those without chronic fatigue |

| Liavaag et al. (2007) | Cross‐sectional | To explore fatigue, QoL and somatic and mental morbidity in ovarian cancer survivors | Ovarian |

Surgery Surgery and chemo |

5,4 years | 184 | Yes | Fatigue, QoL, somatic, mental morbidity | FQ, HADS, QLQ‐C30, NORM |

Answering rate: 66% Survivors reported more somatic and mental morbidity, fatigue and lower QoL than controls |

| Liavaag et al. (2007) | Cross‐sectional | To explore sexual activity and functioning in ovarian cancer survivors | Ovarian | Surgery/surgery and chemo | 5, 4 years | 189 | Yes | Sexual activity and functioning, blood tests for sex hormones | SAQ, BIS, IBM, HADS, QLQ‐C30 |

Survivors reported more somatic and mental morbidity, fatigue and lower QoL than controls Answering rate: 66% Half of the survivors were sexually active, reported lack of interest in sex compared to NORM. Sexual inactivity and poorer sexual functioning |

| Rannestad and Skjeldestad (2007) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate the prevalence of pain in long‐term gynaecological cancer survivors. | Gyn ca survivors | Various | 12 years | 160 | Yes | Prevalence of pain among | Study‐specific, QLI |

Answering rate: 55% 26% reported pain. Predictors were high age, low education, low income, high BMI and oedema |

| Vistad et al. (2008) | Cross‐sectional | To describe and compare physician‐assessed morbidity with patient‐rated symptoms more than 5 years after pelvic RT in cervical cancer survivors and to compare the prevalence of symptoms from bladder, intestine and from gynaecological tract with control women | Cervix | Radiotherapy, brachy | 7, 9 years | 91 | Self‐reported late morbidity compared to physician‐assessed | LENT‐SOMA, SAQ, NORM |

Answering rate: 62% Patient‐rated morbidity higher than physician‐rated. Bladder morbidity grade 3–4 was rated 2% by physician compared to 23% among survivors, intestinal 5% and 45% respectively. A risk of physicians underestimating symptoms |

|

| Rannestad et al. (2008) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate the long‐term QoL in gynaecological cancer survivors | Gyn ca survivors | Various | 12 years | 160 | Yes | Global QoL among recurrence‐free gyn ca survivors | QLI |

Answering rate: 55% No differences between cases and controls regarding global QoL life |

| Vistad et al. (2009) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate the effect of pelvic RT on cobalamin status and the associations between pelvic RT and markers of intestinal absorption in cervical cancer survivors | Cervix | Radiotherapy, brachy | 7,9 years | 55 | Yes |

Self‐reported physical and psychological symptoms Association RT and intestinal absorption. Explore association cobalamin status, diarrhoea, depression |

LENT‐SOMA, HADS |

Answering rate: 62% 20% reported cobalamin deficiency with decreased S‐vitamin B12 and increased S‐MMA levels compared to reference values. No associations between cobalamin deficiency and anaemia, diarrhoea or depression |

| Liavaag et al. (2009) | Cross‐sectional | To explore somatic, mental and lifestyle variables | Ovarian |

Surgery Surgery and chemo |

5, 4 years | 189 | Yes | Somatic and mental morbidity | QLQ‐C30, HADS, FQ, BIS, M‐QOL, SAQ IBM, NORM |

Answering rate: 66% Somatic complaints, mental distress, fatigue, body image and menopause‐related QoL were significantly more common among survivors |

| Dunberger et al. (2010) | Cross‐sectional | To make a comprehensive, detailed inventory of gastrointestinal symptoms reported by gynaecological cancer survivors | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years | 616 | Yes | Study‐specific | Answering rate: 78%. Cancer survivors had a higher occurrence of long‐lasting gastrointestinal symptoms | |

| Dunberger et al. (2010) | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported symptom emptying of all stools without forewarning impacts self‐assessed QoL | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 616 | Yes |

Self‐reported Bowel and social function after RT |

Study‐specific | Answering rate: 78%. Faecal incontinence lower QoL and affect social life |

| Vistad, Cvancarova et al. (2011) | Cross‐sectional | To describe chronic pelvic pain and associated variables in cervical cancer survivors | Cervix | Radiotherapy, brachy | 7,9 years | 91 | Yes | Self‐reported chronic pelvic pain | HADS, MOS, SF‐36, LENT‐SOMA |

Answering rate: 62% Prevalence of self‐reported daily lower back and hip pain was significantly higher among survivors and survivors with pain had significantly lower QoL, higher levels of anxiety and depression and more bladder and intestinal problems |

| Lind et al. (2011) | Cross‐sectional | Self‐reported symptoms from irradiated tissues | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 616 | Yes | Self‐reported physical symptoms after RT | Study‐specific |

Answering rate: 78% Gyn ca survivors treated with RT have a higher occurrence of symptoms from urinary, gastrointestinal tract as well as lymphoedema |

| Dunberger et al. (2011) | Cross‐sectional | Occurrence of loose stools and its relation to certain other factors including faecal incontinence | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 616 | Yes | Self‐reported bowel function after RT | Study‐specific | Answering rate: 78%. Association between loose stools, defecation urgency with faecal incontinence. To avoid loose stools cancer survivors skipped meals |

| Waldenström et al. (2012) | Cross‐sectional | To explore the occurrence of pain in the sacrum and hips caused by RT | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 650 | Yes | Self‐reported hip and sacral pain after RT | Study‐specific | Answering rate: 78%. One in three reported having hip pain after RT. Daily pain when walking more common |

| Rannestad et al. (2012) | Cross‐sectional | To explore the relationship between comorbidity and number of pain sites in long‐term gynaecological cancer survivors | Gyn ca survivors | Various | 12 years | 160 | Yes | Comorbidity and number of pain sites | Study‐specific, SCI |

Answering rate: 55% No differences in comorbidity and number of pain sites NPS between gynaecological cancer survivors and controls |

| Dunberger et al. (2013) | Cross‐sectional | To describe the impact of lower‐limb lymphoedema on overall QoL, sleep and daily life activities | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 616 | Yes | Self‐reported lymphoedema after RT | Study‐specific |

Answering rate: 78% 36% reported lower‐limb lymphoedema. Survivors with lymphoedema; lower QoL, less satisfied with sleep, affect social activities |

| Sekse et al. (2014) | Cross‐sectional | To examine the prevalence of cancer‐related fatigue in women treated for gyn cancer in relation to distress HQoL, demography and treatment characteristics | Gyn cancer survivors | Various | 16 months past treatment | 120 | — | Cancer‐related fatigue relation to anxiety and depression HQoL | HADS, FQ, SF‐36 | 53% reported cancer‐related fatigue with a higher proportion of women with cervical cancer. Women with fatigue reported higher levels of anxiety and depression |

| Stinesen Kollberg et al. (2015) | Cross‐sectional | To examine whether or not vaginal elasticity or lack of lubrication is associated with dyspareunia | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 616 | Yes | Self‐reported. factors associated with dyspareunia after RT | Study‐specific | Answering rate: 78%. 243 women were sexually active. Among them 55% reported superficial dyspareunia, 40% deep dyspareunia, affected 67% |

| Alevronta et al. (2016) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate the dose–response relation between the dose to the vagina and the patient‐reported symptom “absence of vaginal elasticity” and how time to follow‐up influences this relation | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 78 out of 616 | Yes | Self‐reported | Study‐specific | 24 cancer survivors experienced absence of vaginal elasticity. Dose to the vagina and the symptom “absence of vaginal elasticity” increases with time to follow‐up |

| Lind et al. (2016) | Cross‐sectional | To analyse the relationship between mean radiation dose to the bowels and the anal‐sphincter and occurrence of “defecation into clothing without forewarning” | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 519 out of 616 | Yes | Self‐reported. Bowel symptoms | Study‐specific | Mean doses to the bowels and anal‐sphincter region are related to the risk of defecation into clothing without forewarning in long‐term gynaecological cancer survivors treated with pelvic radiotherapy |

| Sekse et al. (2016) | Descriptive/cross‐sectional | To describe and compare sexual activity and function in relation to gynaecological cancer diagnose, treatment modalities, age, psychological distress and health‐related QoL | Gyn ca survivors | Various | 16 months after treatment | 129 | No |

Self‐reported Sexual activity, depression, fatigue, health‐related QoL |

SAQ‐F, FQ, HADS, SF‐36 | Close to two‐thirds of the women were sexually active. 54% of these reported no or little satisfaction with sexual activity. About half reported dryness in vagina; 41% reported pain and discomfort during penetration. There were no significant differences concerning pleasure or discomfort related to treatment modality, diagnoses or FIGO stage |

| Steineck et al. (2017a) | Cross‐sectional | To investigate how smoking, age and time to follow‐up affect the intensity of five different survivorship diseases decreasing bowel health | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 623 | Yes | Self‐reported. Bowel symptoms | Study‐specific | A strong association between smoking and radiation‐induced urgency syndrome. Excessive gas discharge was also related to smoking. Younger age at treatment resulted in a higher intensity, except for the leakage syndrome. For the urgency syndrome, intensity decreased with time since treatment |

| Steineck et al. 2017b | Cross‐sectional | To investigate syndromes that may be related to distinct radiation‐induced survivorship diseases. To investigate which long‐term symptoms to be included in which syndrome | Gyn ca survivors | Radiotherapy | 3–15 years after treatment | 623 | Yes | Self‐reported. Bowel symptoms | Study‐specific | Five factors was identified as radiation‐induced syndromes that may reflect distinct survivorship diseases, that is, urgency syndrome (30 per cent), leakage syndrome (26 per cent), excessive gas discharge (15 per cent), excessive mucus discharge (16 per cent) and blood discharge (10 per cent) |

| Mikkelsen et al. (2017) | Cross‐sectional | To describe late adverse effects, health‐related quality of life and self‐efficacy in order to describe rehabilitation needs | Cervical ca survivors |

Surgery Radiotherapy Chemotherapy |

1–4 years after diagnosis | 85 | No |

Self‐reported health‐related quality of life Self‐efficacy Single questions regarding sexual, body image, bowel and urinary problems |

EORTC QLQ C30 and CX24 |

Answering rate: 79% Several late effects regarding menopausal and sexual and problems with body image Younger women reported more sexual, menopausal, and body image problems. Elderly more problems with diarrhoea Two thirds of the women had one or more severe problems with sexual issues, incontinence, or body image. Obese women reported lower body image, more menopausal and lymphoedema problems, and worse outcomes on several quality‐of‐life subscales. Menopausal symptoms appeared to decrease over time, and the other problems were equally common after 1–4 years In total, 56 (66%) of the survivors had one or more severe problems Young and obese survivors with locally advanced cervical cancer and survivors who received chemotherapy may have a serious risk of developing late effects; thus, rehabilitation should target these needs |

| Steen et al., 2017 | Cross‐sectional | To determine the prevalence of chronic fatigue and its associations to type of treatment, severity of the disease, and physical, psychological and socio‐demographic factors | Long‐term survivors of cervical cancer |

Surgery Radiotherapy Chemotherapy |

11 years (range 7–15) after diagnosis | 461 of 822 (56%) completed the questionnaire, and 382 were analysed | No | Chronic fatigue and its association with treatment‐related factors |

The Fatigue Questionnaire (FQ) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9) EORTC QLQ C30 EORTC QLQ CX24 The Scale for Chemotherapy‐Induced Long‐Term Neurotoxicity (SCIN) |

The prevalence of survivors with chronic fatigue treated by any modality was 23%. Among those only surgical treated, 19% had chronic fatigue, while the prevalence was 28% in those treated with radiation and concomitant chemotherapy The chronic fatigue group reported significantly more cardiovascular disease, obesity, less physical activity, more treatment‐related symptom experience, more menopausal symptoms, higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms and poorer quality of life than the nonfatigued group |

For the nine qualitative studies, the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ; Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007) was used (Table 5). This 32‐item checklist is grouped into three domains: (a) research team and reflexivity, (b) study design; and (c) data analysis and reporting (Tong et al., 2007). All articles were peer‐reviewed. The quality of most qualitative articles was good, although some weaknesses were found in the descriptions of reflexivity (domain 1 of the checklist). Three out of nine articles recognised and clarified the researchers’ background and experience (Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008; Sekse, Råheim, Blåka, & Gjengedal, 2012; Sekse et al., 2010), and four articles described and reflected on their interactions with participants (Olesen et al., 2015; Sekse, Gjengedal, & Råheim, 2013; Sekse et al., 2010, 2012). Concerning the design of the studies, five out of nine articles described an explicit phenomenological hermeneutic methodology (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse, Hufthammer, & Vika, 2015; Sekse, Råheim, & Gjengedal, 2015; 2010, 2012, 2013). All articles reported their sample size and the context in which data were collected; most of them reported how participants were recruited. While three articles used a semi‐structured interview guide (Ekwall, Ternestedt, & Sorbe, 2003; Lindgren, Dunberger, & Enblom, 2017; Olesen et al., 2015), the rest applied an open approach. Questions used in the interviews were provided by all. One out of nine articles included no limitations (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006). Three studies used content analysis (Ekwall et al., 2003; Lindgren et al., 2017; Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008), one used thematic analyses (Olesen et al., 2015), one used Ricoeurian text analysis (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006), and four articles used meaning condensation and narrative structuring (Sekse et al., 2010, 2012, 2013; Sekse, Råheim et al., 2015). One of nine articles had no description of the coding process or analysis except the methodological steps (Ekwall et al., 2003). The others described the process more in depth. Seven out of nine studies described the analysis as carried out in collaboration with the other authors.

Table 5.

Overview of intervention studies

| References | Aim | Design | Type of intervention | Procedure | Sample | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meltomaa et al. (2004) | To evaluate morbidity and subjective outcome after hysterectomy | Quasi‐experimental | Surgery |

Patients underwent hysterectomy with or without lymphadenectomy The intervention was evaluated by self‐assessed questionnaires 6 weeks and 1 year after the intervention |

Total number: 99 Intervention: 38 patients had hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy Controls: 61 patients had simple hysterectomy for ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer |

Overall incidence of complications and subjective outcomes unaffected by type of operation Subjective complaints increased during the study period, however satisfaction with the operation remained high |

| Seibæk and Petersen (2008) | To evaluate the effect of a rehabilitation programme | Pilot Quasi‐experimental | Rehabilitation programme |

Patients followed a nurse‐led multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme consisting of four sessions The intervention was evaluated by self‐assessed health and coping questionnaires after three, six and 12 months |

Total number: 20 Intervention: 10 women attended the rehabilitation programme and regular follow‐up Controls: 10 women underwent regular follow‐up |

After 12 months the intervention group had significant improvement in coping, vitality, and physical functioning |

| Rud et al. (2009) | To investigate any pain‐reducing effect of hyperbaric oxygen treatment (HBOT) | Follow‐up | Hyperbaric oxygen treatment |

Patients with symptoms related to late radiation tissue injury (LRTI) were given HBOT in a hyperbaric chamber over 21 consecutive days The intervention was evaluated after 6 months with questionnaires, global patient scores and magnetic resonance imaging |

16 patients with LRTI after radiation for a gynaecological malignancy | Although HBOT did not have a significant effect on pain and daily function, 50% reported some or good effect of the treatment |

| Mouritsen et al. ( 2013) | To investigate the effect of Kinesiotape on lower limp lymphoedema (LLL) Stage 1 | Clinically controlled | Kinesiotape |

Patients used Kinesiotape 6 days a week during a period of 5 weeks The intervention was evaluated during a period of 6 weeks with circumference, VAS scores, photos, and subjective endpoints |

Total number: 31 Intervention: 24 used Kinesiotape Controls: 7 participated in the evaluation |

Measured by VAS the intervention group experienced improvements in restlessness, heaviness, swelling, and pain Kinesiotape provided relief of subjective discomfort in Stage 1 LLL |

| Ledderer et al. (2014) | To assess the outcome of supportive talks | Randomised controlled | Supportive talks |

Lung or gynaecological cancer patients and a relative as a pair had three supportive talks from the date of admission until 2 months later The intervention was delivered by specially trained hospital nurses, based on a guide Qualitative evaluation with semi‐structured interviews |

Total number: 20 Intervention: 12 pairs received supportive talks Controls: 8 pairs received usual care |

The majority valued the focus on relationship and interpersonal communication The hospital setting provided valuable resources, but existing clinical routines challenged the evaluation |

| Sekse et al. (2014) | To provide insight into the lived experiences of participating in an education and counselling group | Follow‐up | Education and counselling group |

Patients had one meeting per week during 7 weeks Topics were bodily changes, coping, fatigue, nutrition, social rights, getting back to work, sexuality and life beyond cancer Qualitative evaluation with focus group interviews |

17 patients from a total of six education and counselling groups |

The group was described as a special community of mutual understanding and belonging Education and sharing knowledge provided a clearer vocabulary and understanding of lived experiences Presence of dedicated and professional care workers was essential for a positive outcome |

| Olesen et al. (2015) | To develop intervention targeting psychosocial needs during follow‐up | Pilot | Guided Self‐Determination adjusted to gyn cancer (GSD‐GYN‐C) | Development of intervention and pilot test in two phases | Six women aged 30–65 with different living conditions and types of gyn cancer | The women needed individual and holistic follow‐up |

| Olesen et al. (2016) | To test the effect of a person‐centred intervention on gyn cancer survivors | RCT | Guided Self‐Determination adjusted to gyn cancer (GSD‐GYN‐C) |

Women were randomised in a stratified procedure according to diagnosis and time in follow‐up The intervention was delivered by especially trained nurses Outcome measures were QOL‐CS, IOCv2, the Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale, DT, HADS, HCCQ and self‐reported ability to monitor symptoms |

Intervention: 80 Controls: 85 |

In the intervention group significantly higher physical well‐being was observed after 9 months |

| Holt et al. (2015) | To identify and describe rehabilitation goals and the association between health‐related QoL and goals for rehabilitation | Longitudinal observation of health‐related QoL | Hospital‐based rehabilitation programme |

Women were included consecutively The intervention was delivered by especially trained nurse and focused on goal setting in two face‐to‐face sessions and two telephone calls Outcome measures were EORTC supplemented with disease‐specific modules ‐C30, ‐EN24, ‐OV28 and ‐CX24 |

Total number: 151 |

All women defined goals at first session Physical goals decreased over time, but were most frequent in both sessions, whereas social and emotional goals were the second and third most frequent Sexual aspects were most dominant in women treated for cervical cancer QoL and goal setting was significantly associated within social and emotional domains |

| Holt et al. (2016) | To assess changes in attachment dimensions, PTSD and depression after treatment for gyn cancer | Longitudinal observation of adult attachment, depression, PTSD and health‐related QoL | Hospital‐based rehabilitation programme |

Women were included consecutively from one university hospital department The intervention was delivered by especially trained nurse and focused on goal setting in two face‐to‐face sessions and two telephone calls Outcome measures were RAAS, MDI, HTQ and EORTC |

Total number: 151 |

Depression and PTSD were prevalent among women with ovarian and cervical cancer Adjustment of rehabilitation according to attachment anxiety may relieve symptoms |

| Seibæk and Petersen (2016) | To evaluate the effect of a rehabilitation programme | Quasi‐experimental | Rehabilitation programme |

Patients and relatives followed a nurse‐led multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme consisting of four sessions The intervention was evaluated by SF‐36 and SOC after 3, 6 and 12 months |

Total number: 371 217 patients and 154 relatives |

The participants increased physical and mental health during the study period |

In the evaluation of the 11 intervention studies (Table Table 5), we intended to use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework (Guyatt et al., 2008). However, the use of both quantitative and qualitative evaluation methodologies hindered evaluation of the validity strictly in line with the original GRADE framework, as this does not comprise qualitative studies and evaluations. A descriptive approach was therefore applied. The interventions investigated various aspects of rehabilitation, using different kinds of methods: two randomised controlled trials (Ledderer, la Cour, & Hansen, 2014; Olesen et al., 2016), three quasi‐experimental studies (Meltomaa et al., 2004; Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Seibæk & Petersen, 2016), one clinically controlled trial (Mouritsen, Kjærgaard, Petersen, & Seibæk, 2013), two follow‐up studies (Rud, Bjørgo, Kristensen, & Kongsgaard, 2009; Sekse et al., 2014), one pilot study (Olesen et al., 2015) and two longitudinal studies (Holt, Jensen, Hansen, Elklit, & Mogensen, 2016; Holt, Mogensen, Jensen, & Hansen, 2015; Table 5). In nine studies, the evaluation was performed quantitatively via questionnaires, global ratings, imaging and VAS scores, whereas two of the interventions applied a qualitative evaluation methodology.

Table 5 shows that the majority of the intervention studies used descriptive designs, and most had clear purposes or research questions. Outcomes either improved or remained stable during the study period, of which three studies detected statistically significant improvement. Some of the interventions applied self‐referral instead of randomisation. This procedure ensured motivated participants, considered very important in relation to rehabilitation, but impacted the study validity negatively. Consequently, the overall evidence level for the intervention studies ranged from good to low, despite a single high‐rated RCT (Olesen et al., 2016).

2.5. Data analysis

Data analysis in research reviews requires that data from primary sources are ordered, coded, categorised and summarised into a unified and integrated conclusion on the research problem (Cooper & Cooper, 1998; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The objective is an interpretation across the primary sources into a new synthesis. This also applies to the integrative review, and was done in close cooperation among the authors.

The first phase of data reduction divided the primary studies into logical subgroups to facilitate analysis. Each paper was classified according to design, as qualitative (Table 3), quantitative (Table 4) or invention studies (Table 5). In addition, a matrix of all studies and one for each subgroup were subsequently made to enhance clarity and focus.

Table 4.

Overview of qualitative studies

| References | Type of study | Aim | Type of tumour | Type of treatment | Time since treatment | Number of participants | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ekwall et al. (2003) | Semi‐structured interviews | To describe what women diagnosed with gyn cancer reported to be important during their interaction within healthcare system |

2 cervical cancer 4 ovarian cancer 8 uterine cancer |

Radiation or cytostatic therapy | 0 (the day before end of treatment)–3 months | 17 participants | Most urgent need was to remove tumour and be cured of cancer. Good communication and support of central importance to maintain a positive self‐image. 3 main categories: Optimal care, Good communication and Self‐Image and Sexuality |

| Seibæk and Hounsgaard (2006) | Interviews | Investigation of life experiences and health in women managing rehabilitation on their own | Cervical cancer | Surgery for cervical cancer | 3–13 years | 9 participants |

Data were thematised in three categories: To be a body, to be a person and to be a part of a community Common characteristics in women who consider themselves rehabilitated are self‐esteem and strength to be active in the rehabilitation process. They have personal resources to take care of their own body and feminity, they are in good spirits, and they are committed to life. A good network is an important external resource in women's rehabilitation |

| Rasmusson and Thomé (2008) | Interviews | To investigate women's wishes and need for knowledge concerning sexuality and relationships in connection with gynaecological cancer |

7 cervical cancer 2 corpus cancer 2 ovarian cancer |

Surgery and chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy | Consecutively in connection with the woman's last oncological treatment | 11 participants | Two main categories were identified: “The absence of knowledge about the body” and “Conversation with sexual relevance.” The women wished, with their partners present, to be given more in‐depth knowledge about their situation given by competent staff who are sensitive to what knowledge is required. It is important that nurses, who care for women with gynaecological cancer, to meet each woman's individual needs for knowledge about the effects on her sexuality due to her disease and treatment |

| Sekse et al. (2010) | In‐depth interviews | To gain a deeper understanding of lived experience of gyn long‐term cancer survivors and how women experience cancer care |

2 cervical cancer 11 uterine cancer 3 ovarian cancer |

11 surgery 2 surgery and radiation 3 surgery and chemotherapy |

5 and 6 years beyond treatment | 16 participants | The long‐term surviving women experienced profound changes in their lives and had to adapt to new ways of living. Three core themes were identified: living with tension between personal growth and fear of recurrence: the women spoke of a deep gratitude for being alive and of basic values that had become revitalised. They also lived with a preparedness for recurrence of cancer. Living in a changed female body: the removal of reproductive organs raised questions about sexual life and difficulties related to menopause. Feeling left alone—not receiving enough information and guidance after treatment: the process of sorting things out, handling anxiety, bodily changes and menopause were described as a lonesome journey, existentially and psychosocially |

| Sekse et al. (2012) | In‐depth interviews | To highlight how women experience living through gynaecological cancer |

2 cervical cancer 11 uterine cancer 3 ovarian cancer |

11 surgery 2 surgery and radiation 3 surgery and chemotherapy |

5 and 6 years beyond treatment | 16 participants | Three typologies, describing different ways in which the women negotiated encountering and living through cancer, were identified. These typologies are the emotion‐ and relationship‐oriented women, the activity‐oriented women and the self‐controlled women |

| Sekse et al. (2013) | In‐depth interviews | To elaborate how living in a changed female body after gyn cancer is experienced 5 and 6 years after treatment |

2 cervical cancer 11 uterine cancer 3 ovarian cancer |

11 surgery 2 surgery and radiation 3 surgery and chemotherapy |

5 and 6 years beyond treatment | 16 participants | Changes involved dealing with unfamiliarity related to experiences of bodily emptiness, temperature fluctuations, sex‐life consequences, vulnerability, and uncertainty |

| Olesen et al. (2015) | Semi‐structured interviews | To explore gyn ca survivors need for rehabilitation during follow‐up | Different types of gyn cancer | Surgery | 1–5 years | 6 participants | Four identified themes were as follows: (a) contradictory feelings about follow‐up, (b) unmet needs, (c) reactions to unmet needs and (d) barriers to needs being met, which described the women's experiences with the follow‐up visits |

| Sekse, Råheim et al. (2015) | In‐depth interviews | To explore shyness and openness related to sexuality and intimacy in long‐term female survivors of gyn cancer, and how these women experienced dialogue with health personnel on these issues |

2 cervical cancer 11 uterine cancer 3 ovarian cancer |

11 surgery 2 surgery and radiation 3 surgery and chemotherapy |

5 and 6 years beyond treatment | 16 participants | The findings revealed that gyn ca survivors and health personnel share common ground as human beings because shyness and openness are basic human phenomena. Health personnel's own movement between these phenomena may represent a resource, as it can help women to handle sexual and intimate challenges following gynaecological cancer |

| Lindgren et al., 2017 | Semi‐structured interviews | To describe how gyn cancer survivors experience incontinence in relation to perceived QoL, opportunities for physical activity and exercise and how they perceive and experience PFMT (pelvic floor muscle training) | No diagnosis stated |

5 surgery 2 radiotherapy 6 surgery and radiotherapy |

6 months‐21 years (median 3, 5 years) | 13 participants | Data analysed in three categories and 13 subcategories:

|

All authors read all the included articles, and three of the authors had the main responsibility for one of the subgroups. Via consensus, the articles in each subgroup were reduced by extraction of key findings into different manageable formats that fit each design (Whittemore and Knafl (2005). Moreover, the findings were considered in the light of the theoretical perspective of rehabilitation. The next step (data comparison) was an iterative process of examining data displays from primary sources. The method of Whittemore and Knafl (2005) guided the authors at this stage of analysis by underscoring creativity and critical analysis of data. During this process, there were continuous discussions between the authors, and themes were revised until consensus was reached.

2.6. Ethics

Since the study had no direct contact with patients, we neither applied for ethical approval nor contacted any data protection agency.

3. RESULTS

The initial search took place in 2015 and was subsequently repeated in late 2017. The initial search generated 3,692 titles, whereas the search in 2017 further generated 832, in total 4,524 (Figure 1). These were handled in the reference management program RefWorks together with 21 articles from other sources (Table 2). As displayed in the PRISMA diagram, a total of 55 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Outcome of the initial search in 2015

| PubMed | CINAHL | Embase | PsycINFO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search date | 30.6.2015 | 01.7.2015 | 03.7.2015 | 02.7.2015 |

| Number of references | 2,943 | 1,215 | 15,532 | 86 |

| Number of references with date limits (1995–2015) | 2,262 | 1,129 | 14,196 | 65 |

| Number of references with language limits | 2,031 | 1,069 | ||

| Number of references with geographic limits | 1,525 | 741 | 529 | Was not performed |

3.1. Overall characteristics of the studies

The 55 articles originated from Norway (23), Sweden (20), Denmark (11) and Finland (1), clustered according to their design in quantitative/descriptive (n = 35), qualitative/descriptive (n = 9) and interventions/experimental (n = 11 articles). Thirty‐one articles were published 2010–2017, another 16 articles 2005–2009 and eight articles 1995–2004.

The quantitative studies comprised almost 3,000 participants (Table 3). The researchers used either validated or study‐specific outcome measures. Time since treatment varied between 0.7–19 years. Cervical cancer survivors were most frequently studied, followed by endometrial and ovarian cancer survivors. The women were 20–84 years old at the time of the study. A majority lived with partners.

The qualitative studies totalled nine articles, with 69 women who had been through various forms of gynaecological cancer (Table 4). The women were 30‐82 years old, the majority living with partners. The interviews spanned over a time period from immediately after treatment up to 21 years later.

The intervention studies totalled 11 articles and involved 742 women aged 25–85 years. Three studies included a total of 174 relatives (Table Table 5). The interventions varied from 1–21 sessions during the study period, which took place from the beginning of treatment until 5 years later.

According to the theoretical perspective of rehabilitation, the findings will be presented across methods within the following subthemes: physical well‐being in a changed body, mental well‐being as a woman, and psychosocial well‐being and interaction.

3.2. Physical well‐being in a changed body

The women experienced substantial and permanent changes in their bodies. The diagnoses and treatments called upon bodily attention in new ways, and the women needed to regain confidence in, and control of their bodies (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse et al., 2010, 2013). A healthy body was no longer taken for granted (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse et al., 2010, 2013), and coming to terms and becoming familiar with the altered body became core issues.

Some studies described women entering an immediate and overwhelming menopause (Sekse et al., 2010, 2013). A study by Sekse et al. (2010) showed that even women who already had gone through menopause experienced a new, but different, menopause following treatment. In retrospect, long‐term surviving women described intensive heat spells gradually evolving into a permanent change in body temperature (Sekse et al., 2013). A common finding in all studies was an experience of feeling unprepared (Olesen et al., 2015; Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008; Sekse et al., 2010).

Symptoms from the pelvic region originated predominantly from the bowels, the urinary tract, the lymphatic system and the genitals (Alevronta et al., 2016; Bergmark, Åvall‐Lundqvist, Dickman, Henningsohn, & Steineck, 1999, 2006; Dunberger et al., 2013; Liavaag, Dørum, Fosså, Tropé, & Dahl, 2009; Lind et al., 2011, 2016; Lindgren et al., 2017; Mikkelsen, Sørensen, & Dieperink, 2017; Mouritsen et al., 2013; Nesvold & Fosså, 2002; Steineck et al., 2017a, 2017b; Vistad, Cvancarova, Fosså, & Kristensen, 2008). Bowel symptoms, such as diarrhoea, were experienced more often by gynaecological cancer survivors than by noncancer controls (Nord, Mykletun, Thorsen, Bjøro, & Fosså, 2005). Diarrhoea or loose stools was a common symptom post‐radiotherapy treatment (Dunberger et al., 2011; Lind et al., 2011) and documented more than five times a day by almost one‐third of cervical cancer survivors (Vistad, Kristensen, Fosså, Dahl, & Mørkrid, 2009). The women who reported having loose stools also had a higher risk of faecal incontinence (Dunberger et al., 2011). This contrasts with ovarian cancer survivors who significantly more frequently reported constipation (Liavaag, Dørum, Fosså, Tropé, & Dahl, 2007).

A rather high proportion (23%) of cervical cancer survivors reported severe bladder symptoms, such as urinary urgency and incontinence, straining to initiate voiding, bladder‐emptying problems, and night‐time micturition (Bergmark et al., 2006; Vistad et al., 2008). The qualitative study by Lindgren et al. (2017) described the women's reduced quality of life and limited possibilities for physical activity and exercise as a consequence of incontinence.

Lower‐limb lymphoedema (LLL) had a reported prevalence of 36% among survivors with various gynaecological cancer diagnoses (Lind et al., 2011) and was more prevalent among survivors with a high BMI (Mikkelsen et al., 2017; Mouritsen et al., 2013).The ailment was described as a distressful bodily symptom (Bergmark et al., 2006; Dunberger et al., 2013) with negative effect on sleep and overall QoL (Dunberger et al., 2013). Women with lymphoedema worried more about recurrence and interpreted bodily symptoms as potential signs of recurrence of cancer (Dunberger et al., 2013).

Pelvic pain was prevalent (Vistad Cvancarova, Kristensen, & Fosså, 2011; Waldenström et al., 2012), and Vistad, Cvancarova et al. (2011) found that pain was strongly linked to bladder and intestinal morbidity, influenced QoL negatively and led to a higher level of anxiety and depression. In another study of 176 gynaecological cancer survivors (Rannestad & Skjeldestad, 2007), 26% reported having pain, mostly musculoskeletal. A study by Rud et al. (2009), aiming to reduce pelvic pain after radiation, showed no detectable effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, even though some patients experienced relief in overall symptom burden. Finally, Nord et al. (2005) found that gynaecological cancer survivors had a higher prevalence of osteoporosis when comparing adverse health conditions with the noncancer population.

Gynaecological cancer treatment also led to changes in the women's sexual lives (Bergmark et al., 1999; Ekwall et al., 2003; Lindgren et al., 2017; Mikkelsen et al., 2017; Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008; Sekse, Hufthammer, & Vika, 2017; Stinesen Kollberg et al., 2015). Bergmark et al. (1999) described how vaginal changes such as lack of lubrication and a short, insufficiently elastic vagina compromised sexual activity and resulted in considerable distress. Impaired vaginal elasticity and dryness was associated with deep dyspareunia (Sekse et al., 2017; Stinesen Kollberg et al., 2015). In a study by Liavaag et al. (2008), ovarian cancer survivors reported lower levels of sexual pleasure and higher levels of discomfort than the general population. Among cervical cancer survivors treated with surgery, sexual‐related symptoms such as reduced orgasm frequency and intercourse dysfunction were experienced as very distressful (Bergmark, ÅVall‐Lundqvist, Dickman, Henningsohn, & Steineck, 2002). Equally important were reduced or nonexisting sexual feelings or desire (Ekwall et al., 2003; Olesen et al., 2015; Sekse et al., 2013). In a qualitative study by Sekse et al. (2013), women described their sex lives as a kind of vicious circle, with the sense of loss of sexuality.

Cancer‐related fatigue was also a major concern (Ahlberg, Ekman, & Gaston‐Johansson, 2005; Liavaag et al., 2007; Sekse, Hufthammer et al., 2015; Steen, Dahl, Hess, & Kiserud, 2017; Vistad, Fosså, Kristensen, & Dahl, 2007). Fatigue was associated with somatic and mental morbidity (Vistad et al., 2007) such as depression and anxiety. Moreover, chronic fatigue was reported by 23% of long‐term cervical cancer survivors who also reported more cardiovascular disease, obesity, less physical activity, more treatment‐related and menopausal symptoms, poorer QoL and higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Steen et al., 2017). One study (Sekse, Hufthammer et al., 2015) showed that younger women reported fatigue more frequently than older women. Ovarian cancer survivors with poor self‐rated health suffered from significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression, poorer body image, and fatigue (Liavaag et al., 2009). However, an intervention study, addressing the needs of solely surgically treated women, indicated that early, specialised rehabilitation could improve physical well‐being and vitality and reduce the experience of pain (Seibæk & Petersen, 2016).

3.3. Mental well‐being as a woman

Fear of recurrence was a major issue (Olesen et al., 2015; Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008; Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse et al., 2010). Compared to others, gynaecological cancer survivors recorded anxiety and depression more frequently (Aass, Fosså, Dahl, & Aloe, 1997; Steen et al., 2017). Ovarian cancer survivors with poor self‐rated health had significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression and poorer body image (Liavaag et al., 2007). Sekse et al. (2013) revealed a bodily‐based preparedness for cancer recurrence or new disease among the women, thought and spoken of as a permanent change (Olesen et al., 2015; Sekse et al., 2010). Fear of recurrence was furthermore activated before each appointment during the 5‐year follow‐up.

Many of the physical symptoms caused considerable mental distress. Faecal leakage was rated as one of the most distressful symptoms (Bergmark et al., 2002), causing feelings of being nonattractive and changed as persons (Dunberger et al., 2010). The women described how this symptom caused toilet dependency and hindered them from being more physically active, having a sexual life, travelling, etc. They also described how thoughts and practical arrangements around bowel movements preoccupied them several hours daily (Dunberger et al., 2010; Lindgren et al., 2017). The study by Lindgren et al. (2017) showed how lack of information about incontinence as a potential side effect had a negative impact on the women's way of dealing with the situation.

The cancer diagnosis and treatment constituted an existential experience and a life‐changing process (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse et al., 2013). Some studies pointed to reorientation and revitalisations of values. Sekse et al. (2010) showed that personal growth and enriching experiences were strongly present in the women's stories. An increased sense of gratitude to life and a feeling of being “present” and in deeper contact with life were underscored.

There were variations in how the women experienced removal of reproductive organs as related to femininity. Bergmark et al. (1999) reported that a majority of cervical cancer survivors reported little or no distress due to the loss of the uterus, while Rasmusson and Thomé (2008) revealed that feelings of womanliness had been reduced. Sekse et al. (2010) and Seibæk and Hounsgaard (2006) found that most women who were beyond the age of childbearing did not see the removal as an important issue. Nevertheless, one‐fourth of survivors in a study by Bergmark et al. (1999) felt less attractive.

For women who prior to operation had been plagued with bleeding and pain, the removal of reproductive organs could be seen as a relief. However, for younger fertile women who had not finished childbearing, the removal was a dramatic challenge and a great loss (Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008; Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse et al., 2010, 2013).

The women processed their gynaecological cancer experiences and rehabilitation in various ways. Ekwall et al. (2003) showed that some women wanted to be active and participate in healthcare decisions. Seibæk and Hounsgaard (2006) found that women who felt rehabilitated had self‐esteem and strength to participate actively in the process of rehabilitation. These findings seem to be echoed in the study by Sekse et al. (2012), where the women had been active in the process of working through cancer. The reverse applied to the women who had not been rehabilitated (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse et al., 2012) as they had not worked through, nor integrated, the cancer experience in their lives.

Even though follow‐up focused predominantly on physical aspects, the women expressed unmet needs concerning physical and disease‐oriented issues (Holt et al., 2015; Olesen et al., 2015; Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008). Nesvold and Fosså (2002) investigated whether 83 cervical or vulvar cancer survivors had been informed about the risk of lymphoedema after cancer treatment. Twenty per cent had symptoms of LLL but only 30% of these were satisfied with the information given. Moreover, Olesen et al. (2015) found that the lack of knowledge about which symptoms to look for was associated with a feeling of lack of control. Seibæk and Hounsgaard (2006) found that women who considered themselves as cancer patients reported a general deterioration of their life situation and scored lower on general health and physical functioning many years after treatment. Lack of rehabilitation might therefore result in a lifelong view of oneself as cancer patient.

Olesen et al. (2015) and Holt et al. (2015, 2016) suggested new ways of addressing rehabilitation in an individualised and holistic manner. In a randomised trial, Olesen et al. (2016) found significantly higher physical well‐being in the intervention group compared to controls, after they had received a person‐centred empowerment‐based intervention. The intervention was provided as a stepped care approach bridging life and disease and consisting of one to four nurse‐led conversations using Guided Self‐Determination tailored to gynaecological cancer survivors (Olesen et al., 2015). Likewise, Holt et al. (2015) tested goal setting through patient involvement and motivation on rehabilitation and QoL after gynaecological cancer treatment. This study demonstrated a significant association between goal setting and rising QoL scores, especially within social and emotional domains.

3.4. Psychosocial well‐being and interaction

Disease and treatment impacted the women on a personal and participatory level, with feelings of depression, fatigue and sexual dysfunction (Meltomaa et al., 2004; Sekse et al., 2017), or even post‐traumatic distress disorders (Holt et al., 2016). Five intervention studies dealt primarily with the personal and social aspects of disease and treatment, by testing supportive talks addressing couples, two rehabilitation programmes, and group education and counselling (Holt et al., 2015, 2016; Mouritsen et al., 2013; Olesen et al., 2015; Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006). The majority valued the focus on relationship and interpersonal communication in the supportive talks (Mouritsen et al., 2013). Participation in a nurse‐led, multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme with other gynaecological patients and relatives seemed to improve physical well‐being, coping and energy level (Seibaek & Petersen, 2008). Furthermore, education and sharing knowledge in a group provided a clearer vocabulary and understanding of lived experiences.

Having a supportive relative or partner was significantly helpful in the process of coming to terms with oneself after gynaecological cancer treatment (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Seibæk & Petersen, 2016; Sekse et al., 2013). Rasmusson and Thomé (2008) showed that good communication with partners helped the women in handling their changed situation, also regarding sexuality. Sekse et al. (2013) showed that a more quiet, mutual understanding with one's partner, searching for common grounds concerning sexuality, was a fruitful approach. The need for protecting close relations against personal and existential thoughts connected to the cancer arose, particularly in the long run (Olesen et al., 2015; Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse et al., 2013). Moreover, many of the women found it difficult, and sometimes undesirable, to talk about intimate and taboo‐related issues with their close relations (Sekse et al., 2013; Sekse, Råheim et al.,2015).

Understanding and dealing with physical, psychological and existential changes, including intimate and sensitive issues, were described as a lonely process (Ekwall et al., 2003; Olesen et al., 2015; Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008), even in the long run (Sekse et al., 2013). Knowledge about the consequences of the disease and its treatment was important for the women to minimise the risk of negative consequences for the relationships (Rasmusson & Thomé, 2008). However, medical terminology and the healthcare hierarchy were obstacles to satisfactory communication.

There was a need for discussing psychosocial issues related to survivorship (Olesen et al., 2015; Seibæk & Petersen, 2016; Sekse, Råheim et al., 2015). Ekwall et al. (2003) showed that adequate time to talk with healthcare professionals (HCPs) was an important aspect of the experienced quality. Olesen et al. (2015) found that the women experienced neglect concerning psychosocial care in the attitude of some HCPs, as if it were not their domain. Across all studies, a strong need for dialogue between HCPs and the women regarding issues such as bodily‐based changes was evident. The fact that gynaecological cancer affected sexuality and intimate, potentially taboo‐related issues, seemed to make it even more important to have a dialogue with competent HCPs (Seibæk & Hounsgaard, 2006; Sekse, Råheim et al., 2015). For example, satisfaction with the follow‐up on sexuality was significantly lower than satisfaction with cancer care in general. Ekwall et al. (2003) found that the individual woman's unique experiences should be the basis for health care, or the hub around which care revolves. Trust, competence and the ability to listen were core values in relation to intimate and sensitive issues.

In a psychosocial rehabilitation intervention, Ledderer et al. (2014) addressed the patient and relative as a pair, and the results showed that some of the couples found that the intervention facilitated their communication and strengthened their relationship. Studies by Sekse et al. (2014) and Seibæk and Petersen (2016) showed that participating in education and counselling group interventions created valuable feelings of belonging and being understood, and facilitated not only the sharing of knowledge, but also self‐management.

4. DISCUSSION

The physical implications of the gynaecological cancer treatment are framed by a strong perception of having a changed female body. These changes occur in a time span from immediately after the treatment to decades hereafter and may be dealt with as either treatment‐induced short‐term consequences or late effects. Some of these could be measured quantitatively, while others had to be qualitatively described. They represented changes in the reproductive organs, menopause symptoms, various kinds of bowels and urinary tract complications, lymphoedema and pelvic pain. The women sought specific information and advice, but even though the 5‐year follow‐up primarily focused on the physical body, the existing aftercare appointments seemed inadequate to make the women feel confident in and familiar with their altered bodies. Consequently, many women experienced the follow‐up solely as check‐ups for physical recurrence of cancer in general.

Nord et al. (2005) found that long‐term cancer survivors report poorer health status than the noncancer population. Illness disturbs the absence of bodily in‐awareness that characterises living in a healthy body (Merleau‐Ponty & Smith, 1996). It catapults the body to the forefront and demands attention. Besides increased bodily awareness, the women's lack of knowledge and understanding of their altered bodies was associated with a personal feeling of loss of control (Olesen et al., 2015), and a need for information and supervision from an early stage (Lindgren et al., 2017; Sekse et al., 2013). In the case of breast cancer, several studies (Arman & Rehnsfeldt, 2003; Lindwall & Bergbom, 2009; Thomas‐MacLean, 2004) have shown that knowledge and understanding are fundamental in the process of becoming confident and familiar with the altered body. Lindwall and Bergbom (2009) found that women regarded their body as “a stranger” and that they had to process and regain familiarity with their altered bodies after breast cancer surgery. In cancer rehabilitation (WHO, 2001), one of the aims is to reduce the physical consequences of the malignant disease and treatment. Our findings suggest that HCPs need to be quite specific concerning bodily changes: describing and visualising the changes, using anatomic pictures or figures.